SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2021

VOLUME NINE NUMBER THREE

FARUQ Z. BEY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

William Parker

(January 23-29)

Jason Palmer

(January 30-February 5)

Living Colour

(February 6-12)

Charles Tolliver

(February 13-19)

Henry Grimes

(February 20-26)

Seth Parker Woods

(February 27-March 5)

Kendrick Scott

(March 6-March 12)

Marcus Strickland

(March 13-19)

Christian Sands

(March 20-26)

Ulysses Owens

(March 27-April 2)

Steve Nelson

(April 3-9)

Steve Wilson

(April 10-16)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/charles-tolliver-mn0000167787/biography

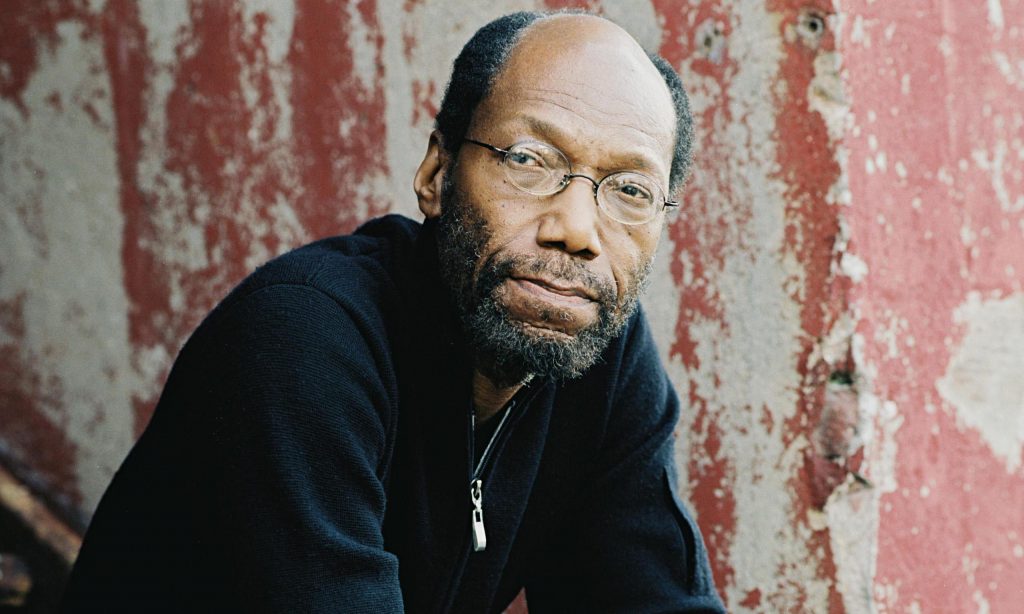

Charles Tolliver

(b. March 6, 1942)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

With his bold tone and adroit harmonic ideas, trumpeter Charles Tolliver has distinguished himself as a forward-thinking performer, often straddling the line between hard bop lyricism and avant-garde exploration. Following his initial emergence in the 1960s as a member of altoist Jackie McLean's group, Tolliver came into his own as a leader, on par with his trumpet contemporaries Woody Shaw and Freddie Hubbard. Collaborating regularly with pianist Stanley Cowell, he moved from small group dates like 1969's The Ringer to expansive big-band albums such as 1975's Impact, featuring his Music Inc. ensemble. Along the way, he and Cowell also founded Strata-East Records, releasing a string of boundary-pushing albums by Gil Scott-Heron, Pharoah Sanders, Billy Harper, and others. Following a period out of the spotlight and teaching, Tolliver re-emerged to regular activity with 2007's Grammy-nominated big-band album With Love. He has remained a vital presence, moving from big-band dates like 2009's Emperor March: Live at the Blue Note to hard-hitting small group sessions like 2020's Connect.

Born in 1942 in Jacksonville, Florida, Tolliver became interested in music at a young age while listening to his parents play Jazz at the Philharmonic albums on their Victrola. Around age eight, his grandmother bought him a cornet he had seen in a local pawnshop, and he began practicing diligently. It was around the same time that he moved with his family to New York City. There, living in Harlem, his uncle introduced him to albums by Miles Davis and Clifford Brown. Tolliver also gained further fluency playing trumpet in his high school concert, marching, and dance bands. While music was his passion, he first studied pharmacy at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he spent his off-hours practicing trumpet and developing his jazz skills. Returning to New York in 1963, he began sitting in at local clubs, playing with rising luminaries like Chick Corea, Jack DeJohnette, Larry Willis, and others.

Tolliver caught the attention of Jackie McLean and made his recorded on the altoist's 1964 album It's Time, alongside pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Cecil McBee, and drummer Roy Haynes. Along with continued work with McLean, Tolliver branched out, recording with Booker Ervin, Roy Ayers, Andrew Hill, Max Roach, and Horace Silver. In 1965, he contributed to the landmark concert album The New Wave in Jazz. Recorded live at the Village Gate, the record showcased leading cutting-edge players of the era, including John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, Grachan Moncur III, and Albert Ayler. Tolliver's group, which featured vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, tenor saxophonist James Spaulding, drummer Billy Higgins, and bassist McBee, played a cover of Thelonious Monk's "Brilliant Corners" and the trumpeter's original "Plight."

In 1966, Tolliver went on a West Coast tour with percussionist Willie Bobo. At the end of the tour, he stayed in Los Angeles, eventually joining Gerald Wilson's big band. He remained with Wilson for a year, recording an album with the group. Upon receiving an invitation to join Max Roach's band, he returned to New York, where he played with the drummer for two years, working alongside fellow avant-gardist Gary Bartz. Tolliver also made his official debut as leader with 1968's Paper Man, a hard-hitting session featuring pianist Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Joe Chambers. Around the same time, he recorded a session for Black Lion under Charles Tolliver & His Allstars before returning to the label for 1969's The Ringer, with pianist Stanley Cowell, bassist Steve Novosel, and drummer Jimmy Hopps.

In 1970, Tolliver and Cowell launched the Strata-East Records label, a loose outgrowth of Detroit pianist Kenny Cox's Strata Records. Along with their own albums, including 1971's Music Inc., the debut from his and Cowell's innovative ensemble, they released a string of highly regarded, avant-garde-leaning albums by Pharoah Sanders, M'Boom, Billy Harper, Gil Scott-Heron, and others. Tolliver continued to tour regularly, appearing often with Cowell and Music Inc., which eventually expanded into a large big band featuring players like James Spaulding, Charles McPherson, Clint Houston, and others. It was this group that appeared on their 1975 Strata-East album Impact.

During the '80s and '90s, Tolliver kept an increasingly low profile. That said, he kept performing, appearing with various incarnations of Music Inc. and touring Europe, where he was featured alongside many top jazz orchestras. He also taught, working at the New School and continued to manage the Strata-East catalog. In 2007, he burst back into the spotlight with the big-band album With Love. Nominated for a Grammy, the album garnered widespread critical acclaim and helped reintroduce Tolliver and his harmonically sophisticated brand of post-bop. He was also presented with the award for Best Large Ensemble of the Year by the Jazz Journalists Association.

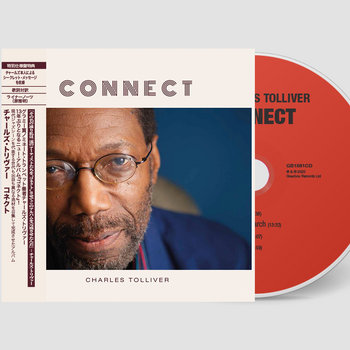

Tolliver returned two years later with another big-band date, Emperor March: Live at the Blue Note. More accolades followed, including receiving an Award of Recognition at the 2017 FONT Festival of New Trumpet. In 2020, he released Connect, his first small group album since the 1970s. Recorded by Tony Platt at London's RAK studios, it featured alto saxophonist Jesse Davis, tenor saxophonist Binker Golding, pianist Keith Brown, bassist Buster Williams, and drummer Lenny White.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/charles-tolliver-blowing-down-the-walls-of-trumps-jericho

Charles Tolliver: Blowing Down The Walls Of Trump’s Jericho

AllAboutJazz

Connect is Tolliver's first release in over a decade and it is a monster. It finds him fronting a US quintet which brings with it the grit and groove of a classic Blue Note hard-bop band while also sounding totally 2020. The lineup is augmented on two of the four tracks by tenor saxophonist Binker Golding, one of the young lions of the new London jazz.

Born into what he describes as "dirt poor" beginnings in Jacksonville, Florida, Tolliver moved to New York with his family at the end of the 1940s, still a young child. He was a high-achieving school student. After spending three years at Howard State University in Washington D.C., and diligently practicing his trumpet in the city's Rock Creek Park, Tolliver returned to New York in the mid-1960s. He burst on to the scene almost immediately, when Jackie McLean hired him for his band.

Tolliver's recording debut was McLean's It's Time! (Blue Note, 1965). In his sleeve note, the critic Nat Hentoff wrote that in Tolliver, McLean had found "a new trumpeter of solidity as well as daring," a description which nails Tolliver's qualities to perfection. Tolliver wrote half the material for It's Time!, showing himself equally adept at burners and ballads, and shared the writing credits again on McLean's Action (Blue Note, 1967).

A year with Gerald Wilson's band in Los Angeles followed, before Tolliver answered Max Roach's call to return to New York and join his band. During this time he was also featured on important albums recorded by Roach and by Roy Ayers, Horace Silver and Gary Bartz.

In 1971, Tolliver co-founded Strata-East with the pianist Stanley Cowell, whom he had met in Max Roach's band. Just as Impulse! had been the primary platform for progressive African American jazz in the 1960s, so Strata-East carried the torch in the 1970s. In 1974, the label enjoyed unexpected success with Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson's Winter In America. The album made Billboard's top ten jazz albums chart and one of its tracks, "The Bottle," released as a single, became a top twenty R&B hit.

By the end of the decade, Strata-East had released 58 albums of near-uniform artistic excellence, a remarkable achievement for an independent company run by two musicians with no previous business experience. Tolliver released several landmark albums on Strata-East, under his own name and with Cowell and other musicians.

In this interview, Tolliver talks about his childhood, key events in his career, the founding of Strata-East, Black Lives Matter and the abomination that is President Trump.

All About Jazz: Did you come from a musical family?

Charles Tolliver: It was a jazz loving family. My parents were super hip. We had one of those old victrolas. I don't know where they got the money to get the thing, because we were dirt poor. But they had these 78rpm records and they were all Jazz At The Philharmonic. Those recordings became my mantra at the age of 4 or 5 years old. I remember Charlie Shavers particularly. Norman Granz did so much for jazz. I mean, not just for me, for the music in general.

It was my grandmother who got me my first horn. Kids in the south tended to be brought up by their grandmothers, because their mothers had to be out doing maid work or something. So it was the grandmother who raised the child. She was the matriarch of the family. Normally you would call your grandmother "momma." My dear mother, my brother and I called her by her first name, Ruby.

When I was about 5, walking back from kindergarten school, I saw a cornet hanging in this dingy little pawnshop. I would see it there for about the next three years and I would say, "Momma, I would so like to get that cornet." And she saved her pennies and God knows how, somehow she saved up enough that one day she got this thing for me.

AAJ: When did you move from Jacksonville to New York?

CT: In 1947, my father decided to move to New York. When they were demobbed, a lot of the Negro soldiers emigrated north to other places. Chicago, Detroit, New York and so on. Then later my mother decided she wanted to go there too, to be with my father. My grandmother would have none of it. She said the whole family had to be together. So everything we owned was packed up in one of those long-bodied automobiles that belonged to one of her relations, and off we all drove to New York.

We were able to be housed in the same apartment building as my grandmother's son, in Harlem. He had all these great records because he was super hip too. One was 'Round Midnight by Miles Davis, and there was Max Roach and Clifford Brown At Basin Street. Those two records changed me forever. Clifford Brown became the mantra for me in terms of what is achievable by a human being in playing this piece of metal. And of course Round Midnight is still with me today.

During my teenage years I always made sure I was in contact with like-minded teenagers and we would get together and do jam sessions and talk about music. At high school I was in all the bands—the concert band, the marching band for the football games, and the dance band for the weekend dances.

AAJ: So when you left high school, how come you went to Washington to study pharmacy?

CT: That happened because in my last year I had a part-time job delivering medicine for our local apothecary. It was the only black-owned pharmacy in Harlem at the time. I watched him mix the medicines—this is before medicines came pre-mixed—and I got fascinated. I said to myself, if he doesn't do that right, people die. So after high school I applied to Howard University in Washington D.C. to study pharmacy. Not necessarily to make a career of it, but because it fascinated me. Music was always there though. In fact most of my time at Howard I was in the Fine Arts building.

AAJ: Within a year or so of graduating you were working with Jackie Mclean. You must have done a lot of practicing in Washington.

CT: Well, yes. Every day I was in Rock Creek Park practicing my horn. And one day in 1963 I realised I'd finally caught up with what I'd heard with Clifford Brown. So I came back home to Harlem.

I began doing jam sessions at a place called The Blue Coronet in Brooklyn. There was Chick Corea, there was Jack DeJohnette, totally unknown, just starting. And one night I came off the bandstand and this gentleman said, Jackie McLean might be looking for a trumpet player. And I mean, as a teenager we woke, ate and slept Jackie McLean. He said, this is where he is, go and see him. And I did. He was drying out at the time, in one of those facilities. He said come and see me when I get out and bring your instrument. So I did. He was playing at Slugs. It was sawdust on the floor from the front door to the back. Larry Willis on piano, totally unknown, who I also grew up with in Harlem, and Billy Higgins on drums. And Jackie said, I'm going to put you on a record date. This was early 1964.

At the studio there was Alfred Lion with his stopwatch and Francis Wolff with his camera taking pictures. And then arrived Roy Haynes. And I was saying to myself, you got to be kidding me. And then arrived Herbie Hancock. And then arrived a new bassist that nobody ever heard of before, Cecil McBee. This record became known as It's Time!. And though Jackie didn't say it, he implied to me that he was going to go beyond bebop. And I ate and slept bebop. So the songs Jackie asked me to bring to the recording I had to rethink and revamp and reimagine in order to deal with where I knew he wanted to go. Until today that's really one of my favourite recordings.

AAJ: Around this time you contributed a track to a live album Impulse! recorded at the Village Gate [The New Wave In Jazz]. How did that come about?

CT: That was through Leroi Jones—this was before he changed his name to Amiri Baraka. He knew about me and he would come to Slugs. One day I got a call from him and he said, listen, I'm going to do a concert at the Village Gate and Impulse are going to record it, and I'd like you to be on it, and Bob Thiele wants to record it for Impulse because John Coltrane will be on the bill.

For me the original Village Gate in Greenwich Village was the best of any venue for jazz. It was in this incredible art deco building. I don't know how Art D'Lugoff could have sold it to become a pharmacy. It was so beautiful. The street level had this wonderful café, and then you walked up a little bit of stairs and you had an incredible restaurant and nightclub. But in the basement was where iconic things happened. Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Charles Mingus, Art Blakey, Sonny Rollins, the list goes on.

So anyway, Leroi Jones called me. And I thought, wow, why me? But he'd been listening to me and I guess he liked me. So I put a band together. Bobby Hutcherson and I were very close, and I was very close to Billy Higgins, I used to see him every day. And Cecil McBee, he and I were very close. And James Spaulding. So I brought that band into the Village Gate for the concert and we did "Brilliant Corners." And the bands on that night—there was my band, Grachan Moncur's, Archie Shepp's, Albert Ayler's, and the main attraction, John Coltrane—that became known as the New Thing.

AAJ: Did you know Coltrane well?

CT: Not really. See, we were in such awe of John Coltrane. Truly, if ever there was a God in jazz, like Beethoven in classical, Coltrane was and is it. Just his presence for me was awesome. A lot of guys, they'd go up and, you know, hey John, and want to shake his hand and everything. And he was very gracious about it. But for me, he was like God, so I didn't talk to him. Later, at the Half Note, I talked a little to him, just to say hello. I never said, I'm Charles Tolliver or anything like that. Maybe he knew who I was, I don't know. He was a very peaceful guy. He would always be reading a book and smoking his brown cigarillos.

AAJ: Then you moved to California. Why did you leave New York?

CT: Well, there was actually very little work in New York then. Every night we'd come out from Slugs and walk across the West Side to the Village Vanguard and if Sonny Rollins was playing there it was to five people, man, trust me. Not even the big names were earning anything. There was a dedicated audience, that has never gone away, and on the weekends there'd be a few more people, but on the weekdays they weren't there.

So in 1965 I used to practice with Bobby Brown, a musician no-one knows about because he was never written about. We met at jam sessions and we became friendly. And one day he said, look, Willie Bobo is looking for a trumpet player to make a tour out West. Bobby had just done a Willie Bobo album, Uno Dos Tres 1.2.3., and the trumpet player on the record, Melvin Lastie, had died or something. I wasn't interested in Willie Bobo because I didn't know how great he was yet—I was soon to learn that he could get off the timbales and play wonderful trap drums. But I said to Bobby, OK, I'll do it. Because I had never been to California and I wanted to see L.A.

AAJ: Which is where you joined Gerald Wilson's band.

CT: When the tour was over I stayed in L.A. because one night a wonderful trumpet player named Freddie Hill, who had been playing in Gerald Wilson's band for a number of years, said, hey man, you're from Jacksonville, that's where I'm from too. And Freddie said, are you going to stay in L.A.? I said yeah, but I don't have any money, I'm broke. He said, let me take you to Gerald Wilson, see if I can get you in the band.

So he took me to Gerald Wilson's house and Gerald said, OK, but before we get you in the band I got to send you to my tailor. I had these tattered clothes on and Gerald was quite a dresser. It was a really high-end men's clothing store and the man was a really big jazz fan and benefactor of Gerald's big band. I got two wonderful suits, man, free of charge. I kept those suits for years because I wanted to pass them on to any children I had in the future. But eventually the moths got them. I stayed in L.A. with Gerald's band for a year and in 1967 we recorded one of my songs, "Paper Man," on Live And Swinging.

AAJ: Then you went back to New York and joined Max Roach.

CT: See, I knew Max Roach before I went to Los Angeles. I used to go and see Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln and the band he had at that time with the great Freddie Hubbard and James Spaulding. They were working at the Five Spot, and they knew I was one of the new trumpeter players on the scene. And I said, Max, if you ever need a trumpet player, think about me. Then a year later, in L.A., I got a call from Max Roach and he said, OK, I'm starting a new band, get your ass back here.

AAJ: Given that he'd co-led a band with Clifford Brown, and you admired Brown so much, that must have been something for you.

CT: It was the end of the world. Man, you could have put me in a coffin and just laid me to rest. I mean, I'm good to go. So I found a way to get back home. In those days there'd be ads in the newspapers saying anyone who wants to drive a car to some place, come into our office and bring $50 deposit. You'd deliver the car and the person would give you the $50 back plus another $200. It was faster than using the Greyhound bus. That's how I got back to New York. That's when I met Stanley Cowell, who was on piano, who was to become my lifelong alter ego and partner in Strata-East.

AAJ: How did Strata-East come about?

CT: There were these guys in Detroit, they had a thing going. They had a corporation called Strata, and they brought us there to play at the Strata Concert Gallery. I made a great recording from there that I might bring out at some point. Anyway, they said, you've got this recording, why don't you become our Eastern Strata? Because they didn't want to put out records, they wanted to put on concerts, that was their thing. They were trying to sell stock to family and friends to raise funds to do that. And when we got back to New York, I said to Stanley, I'm not interested in selling stock to friends. But I incorporated the name Strata-East.

The musicians in New York loved the idea. We explained to them, you're not on any contract with Strata-East. You do your record and if we like it we'll put it out for you. The real impetus, the person who became our greatest ally, was Clifford Jordan. Because he had it in mind all the time, he was just quiet with it. He had already produced these recordings before we started the label, with Pharoah Sanders and all these other people, and he brought all of that to us.

AAJ: Strata-East was perceived as a politically orientated label. Was that intended?

CT: Our founding intention was more to give musicians a fair shake of the whip. You see, what is happening now with Black Lives Matter, it was already there, though that was not the term used. We'd all been talking about it since when I started to work with Max Roach in 1967. Max had already done We Insist! and he was always trying to have Abbey work out these lyrics when he had her performing with us. And from 1967 to 1969 I spent a lot of time at his house and I knew where his head was at. And, I mean, John Coltrane had already done "Alabama." The label itself was not political. But because of what was going on—the Voting Rights Act, the murder of Martin Luther King, and the riots—the musicians in our circle and the stuff they recorded, this gave it a political dimension.

AAJ: Like Gil Scott-Heron.

CT: One day a guy walked into our office. He said, my name is Gil Scott-Heron and I heard about what you guys are doing and I'd like to put out a record with you. I didn't know who he was, I didn't know he was an underground spoken-word person. But I said, OK, let's hear what you got. He'd already put albums out with Bob Thiele's Flying Dutchman, of course, but he was unsatisfied with it. He knew that with the sort of royalties all those companies were offering, you're never going to get any money, you'll only ever get the advance.

The recordings Scott-Heron brought to us were not in all that great shape. They were on cassette tapes. But I thought they were good. So I said to Stanley, it's not jazz, he's a poet, you know, and Stanley listened and said, OK, why not, what the hell, he wants to put it out with Strata, fine. And we were smart enough to know how to get them mastered decently. So we put it out. And one day I got a call from a guy I knew at a record store in the Village. He said, you guys just put out a record called Winter In America, right? There's a track there called "The Bottle" and that's going to go. I said, go? What do you mean? He said, it's gonna be a hit, man. I said, OK, we'll see. And the rest is history.

AAJ: Can we finish with Black Lives Matter and the situation for African Americans in the US in 2020?

CT: I'll say it this way. Black Lives Matter, what they call it today, actually began in 1619 when the first slaves were brought to America by the British. But they kept it all out of the history books for centuries. We have to be thankful for this exponential explosion of gadgetry like smart phones, which allows anyone to film anything the moment it happens. Without that, we'd still be back in 1619. So now, finally, after four hundred and one years, I think we're going to get there. This could never have happened without black people and white people across this globe saying, enough, absolutely enough. So now I think we're going to be OK.

We in America, we will do this. We will get rid of this despicable 45th President and all the sycophants around him who want to "make America great again." America was never fully great, not with the way black people were treated. But I think we'll get there now. Those of us who grew up in New York and are the same age as Trump, we saw him get all this money from his father who was an out and out racist, and Trump grew up with that and it never left him. And any other person who was so misogynous, who went around grabbing women like that, he would never even have been made a candidate for President. That element of our society has to be culled, just like animals are culled when you get a bad litter.

You have to run the table, just like in poker. And we will take back control, take back the center, control the law making. And the world will be healthy again. This will happen. It doesn't matter if it's Biden or some other Democrat nominee. There's no way in heaven we will not win the Presidency back from this despicable man.

All That Jazz: Charles Tolliver

What was left of post-bop in 1970? Caught between the Scylla of fusion and the Charybdis of the avant-garde, such incomparable modernists as Jackie McLean and Andrew Hill had gone, in just a few years, from the cutting edge to the shadows, and found themselves without a record label. On May 1 of that year, the twenty-eight-year-old trumpeter Charles Tolliver, a key sideman for both, brought his quartet, Music Inc., to Slug’s Saloon on East 3rd St., between Avenues B and C, and had the prescience to record the gig. He and the band’s pianist, Stanley Cowell, promptly founded their own record label, Strata-East, to release their own work as well as that of others from their fold. The group’s resulting recordings, now available from Mosaic Records, via Amazon, are fervent, intimate classics of live jazz; they convey the spirit of the cramped bandstand and the rapt crowd as keenly as Charles Mingus’s Debut recordings from the Cafe Bohemia, Eric Dolphy’s Five Spot dates, and John Coltrane’s sets from the Village Vanguard. Tolliver’s interplay with Cowell and the drummer Jimmy Hopps seems telepathic; he blends the vehemence of Coltrane, the modal intricacy of Miles Davis, the blues-based lyricism of Lee Morgan, and even the banshee fanfares of Albert Ayler. I wore out the grooves of their LPs, “Live at Slug’s,” volumes 1 and 2, and the followup, “Live in Tokyo.” All three are together in this box, along with an hour of outtakes.—Richard Brody

https://www.wbgo.org/post/self-determined-then-and-now-focus-charles-tolliver#stream/0

Self-Determined, Then and Now: A Focus on Charles Tolliver

Charles Tolliver has lived his share of jazz history. As a fiery young sideman with Jackie McLean and Max Roach in the 1960s, he joined a lineage of exalted post-bop trumpeters, more than holding his own. But Tolliver also set a model of self-determination in the ‘70s, with a DIY record label called Strata-East.

I first discovered Tolliver’s music in my teens, and earlier this year I realized that 2020 marks Strata-East’s 50th anniversary. So in February, not long after I arrived in the New York area, I arranged an interview with Tolliver. In this third episode of Jazz United, you’ll hear portions of that interview as well as a conversation with my cohost, Nate Chinen.

We were especially interested in considering Strata-East as a groundbreaking case study. With a mission to record and release music themselves — sidestepping the delays and other hassles of a traditional industry pipeline — Tolliver and his label cofounder, pianist Stanley Cowell, made a significant mark.

Likeminded artists, including Roach, saxophonist Clifford Jordan and percussionist and vocalist Mtume, brought their projects to Strata-East. The incisive soul poet Gil Scott-Heron released a landmark album on the label, Winter in America, that yielded a hit single called “The Bottle.” (It reached No. 15 on Billboard’s Top R&B Singles chart.)

And when Nate told me that Gearbox Records would be issuing an all-new Charles Tolliver album this summer, I was ecstatic. We’ll also discuss that album — Connect, which releases on July 31 — and hear a portion of its lead single, “Blue Soul.” And we’ll talk about how Tolliver’s early example of self-determination takes on even greater significance during the coronavirus pandemic, as artists are compelled to handle their own production and promotion.

Jazz United is produced by Sarah Kerson. Our senior producer is Simon Rentner.

Please subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Music in This Episode:

- “Drought,” by Charles Tolliver

- “The Awakening,” by Keyon Harrold

- “The Bottle,” by Gil Scott-Heron

- “Blue Soul,” by Charles Tolliver

There’s no title track on the new album from Charles Tolliver—his first in over a decade. But is name—Connect—isn’t some ethereal abstraction: it’s an invitation.

“I wanted the music to connect in these times,” explains the trumpeter-composer, a 50-plus-year music veteran and the co-founder of the legendary 1970’s jazz label Strata-East Records. “I’m asking the listener to get it: to get what I’m doing, where this or that song is going, and what’s meant here or there, and how the soloists handle it. Those are connections to be made within each song, and then they can also connect them to each other.”

Of course, that’s what any musician asks of their audience. Tolliver, however, has more up his sleeve than that. There are four songs on Connect, recorded in London last November with an all-star quintet (alto saxophonist Jesse Davis, pianist Keith Brown, bassist Buster Williams, and drummer Lenny White). Tolliver carefully selected them for a panorama that documents jazz’s evolution during the time he’s been a part of it.

“On some recordings, the feel is the same throughout,” he says. “The artists are dealing specifically with the time—right in that moment—in which they are recording it and putting it out. In my case, each one of them represents a different period in my involvement with this art form: a look at different avenues that have been explored. Especially in the rhythm, which is such a driving force with this music.”

In other words, the record takes a historical view—but its aim is not to evoke specific dates or even a linear chronology. It’s more like an exhibition of varying flavors that have developed under the aegis of jazz. “My thought was to have a package where each song had a different rhythm,” Tolliver says. “They have different harmonic and melodic scopes, too. But the rhythm, well, it’s everything. The drum is central to this music. You cannot call this music ‘jazz,’ that nomenclature, without the drum. Take it out, and it’s just not the same.”

Indeed, it’s the rhythms that define the songs’ disparate and distinct personalities. “Blue Soul” is a burning piece of soul jazz, and it’s the tune’s gospel-charged stomp that drives that home. The ambitious “Emperor March” (the title track of Tolliver’s last album, a big band date recorded in 2008) has three rhythmic sections: a dead earnest post-bop stride, a Latin clavé, and a jazz-funk groove. “Copasetic” takes the traditional swing route. “Suspicion” has both the album’s most and least complex rhythmic signature. At its core is a West African polyrhythm, with White playing at least two interlocking parts on his kit. Once that core is established, however, the musicians swerve into free territory.

As implied, each of these styles appear on Tolliver’s C.V. Within five years of his 1964 arrival in New York, he had recorded with hard bop stalwarts Horace Silver, Max Roach, and Booker Ervin; soul-jazz pioneer Roy Ayers; and avant-garde innovator Andrew Hill (whom Tolliver credits with the ideas behind “Suspicion”). At Strata-East, he either played on or shepherded the release of myriad styles, from straight-ahead and jazz-funk to experimentalism and pieces related to the Black Consciousness movement.

The band, too, had been put through their paces: the Connect recording session came in the middle of a European tour on which the quintet was working through these tunes nightly; if they hadn’t previously mastered the different approaches, they had them down by the time they entered the studio. If there was a wild card, it was the young London tenor saxophonist Binker Golding, whom Tolliver invited to play on two tracks (“Emperor March” and “Suspicion”) never having played with him before. But even he, the trumpeter says, was a sure thing.

“I knew that he would be able to deliver what he did on the recording,” says Tolliver. “I chose the two tracks that would fit him. He’s a drum man, in his music, as well. Those rhythms are right in his milieu.”

The recording was a whirlwind. They landed in London, checked in to their hotels, played a one-night stand at the Jazz Café on November 6th and headed into the famed RAK Studios the next day. Golding met them there, having received the music before the band left the States. Tolliver wanted to capture some spontaneous energy, so they charged through the material with no second takes. The whole session wrapped within three hours.

He also hoped to take the band on another tour in support of the release. “If the record had come out as normal, I think it would have caught enough reportage that we could have brought this band onstage in the fall, especially in the UK and the continent,” Tolliver says. He had even booked another stint at the Jazz Café in London. COVID-19, however, made short work of those hopes.

Fortunately, Tolliver’s long break between recordings has allowed him to build up a stockpile. “I’ve been sitting on a lot of recordings, for a lot of years,” he says. “People still want to hear their favorite music, maybe now more than ever. This might very well be a good time for me to start issuing my material: the one thing that is not affected by this scourge is recorded music.” There is still connecting to be done.

https://www.wrti.org/post/wrtis-npr-live-sessions-video-week-trumpeter-charles-tolliver-plays-hit-spotWRTI's NPR Live Sessions Video of the Week: Trumpeter Charles Tolliver Plays "Hit The Spot"

Charles Tolliver is a model for autonomy and self-sufficiency in music. His work as a founder of Strata-East Records set a standard for black creative independence in the 1970s, and the label's extensive catalogue has enjoyed a renaissance as new generations discover those seminal recordings under the catch-all term of "spiritual" jazz.

Yet the trumpeter has also played well with others in a career spanning nearly 60 years. Tolliver's recording debut with saxophonist Jackie McLean on It's Time for Blue Note Records put him on the radar, and he followed with appearances on durable post-bop recordings from pianist Horace Silver, saxophonist Booker Ervin, and drummer Max Roach.

Tolliver's urgent and restive trumpet has always sounded best when set within his own harmonically advanced compositions, and he has written extensively. The catchment for that original work has been Music Inc., a group that can expand to big band format or pare to its more customary trumpet plus rhythm section.

Originally a quartet with pianist and Strata-East co-founder Stanley Cowell, Music Inc. is also recognition, by name and deed, that enterprise is an essential part of the artist's creative life. When it comes to making his music, Charles Tolliver is all business.

WRTI captured the New Charles Tolliver Music Inc. performance of "Hit The Spot" live from the Philadelphia Clef Club of Jazz & Performing Arts in October, 2019. Tolliver received the Living Legacy Jazz Award from the Mid-Atlantic Arts Foundation at the Kimmel Center a day before this engagement.

https://www.wrti.org/post/trumpeter-charles-tolliver-headlines-jazz-october-remember

Trumpeter Charles Tolliver Headlines a Jazz October to Remember

September presented jazz enthusiasts in Philadelphia with a full calendar, with so many events in planetary orbit around the sun that was John Coltrane's 93rd birthday celebration. But September’s got nothing on October.

Once again we’ve got several satellites revolving around a single musical lodestar, this time in the form of self-taught trumpet and compositional virtuoso Charles Tolliver.

In what will be the month’s most high-profile event, Tolliver will receive this year’s Living Legacy Jazz Award from the Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation (MAAF) on Friday evening October 11th.

This is a big deal.

It’s the 25th anniversary of an award with several notable Philadelphians among its past recipients, from Odean Pope and Kenny Barron, to Benny Golson, Jimmy Heath, Shirely Scott, and Reggie Workman. In other words, a veritable Mt. Rushmore of Philadelphia’s finest.

And it’s coming home.

This year marks the first time in the award’s quarter-century history that the Living Legacy will be presented in Philadelphia, as it ends a years-long relationship with the Kennedy Center in D.C. and begins one with our crown-jewel venue, the Kimmel Center.

This year’s Living Legacy Jazz Award ceremony is doubly special because it will serve as the kickoff event for the Kimmel Center’s 2019/2020 jazz season, with performances by acclaimed jazz-pianist Marcus Roberts and the Modern Jazz Generation Band, as well as a special guest-appearance by last year’s Living Legacy honoree, the legendary 89-year-old pianist, Toshiko Akiyoshi.

Tolliver who by his own admission “likes to rumble” and “take the most difficult routes for improvisation…by trying something [new] out right from the jump,” will have to cool his heels here and relish being the evening’s guest of honor.

He will, however, have the opportunity to play his heart out the next evening at the Clef Club, where his “4tet” featuring Lenny White (drums), Buster Williams (bass), and Victor Gould (piano) will not only play their rear ends off for two hours beginning at 7:30, but will also, simultaneously, function in several ceremonial capacities.

Tolliver’s 4tet will, on one hand, be celebrating the 50th anniversary of their leader’s landmark debut recording Paper Man, an album that featured legendary sidemen like Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Gary Bartz, and they’ll also be kicking off the second season of the Clef Club’s Jazz Cultural Voices series.

Like a college history course that’s cross-referenced as a political science course and an anthropology course, too, seeing Tolliver’s 4tet will also net you credit for catching the culminating event of Jazz Philadelphia’s Summit 2019.

And while you’re at the Clef Club that Saturday evening, be sure to take note of the memorial celebration that will be taking place two days later, on Monday October 14th, in honor of “Cousin” Mary Alexander, John Coltrane’s late cousin Mary who was his artistic muse and among the best ambassadors for jazz music that Philadelphia has known.

This event will be a musical celebration of Mary’s life, and several well-known musicians are expected to perform. The lineup has not been finalized, but among those you might reasonably expect to perform are poet and spoken word artist Pheralyn Dove, vocalist Barbara Walker, Philly saxophonists Bootsie Barnes and Carl Grubbs, and pianists Doug Carne and Aaron Graves. While those names are subject to change, there’s no doubt the feeling at the Clef Club, in celebration of such a giant, will be extraordinary.

Now you might be thinking: Hey! Let’s rewind a bit. What was that piece about Jazz Philadelphia’s Summit 2019? We know Tolliver’s performance at the Clef Club is serving as Summit 2019’s culmination, but what about those who want to hop on board the Summit 2019 train as it’s first pulling out of the station?

I’m glad you asked. This Thursday night at South Jazz Kitchen is the place to start; pianist Sumi Tonooka will be unofficially kicking off Summit 2019 by performing as part of bassist Gerald Veasley’s Unscripted Series. Veasley is the president of Jazz Philadelphia, so, you see, this really will be the official unofficial kickoff.

Got all that?

The next morning, at the Kimmel Center, Terell Stafford, every bit a Philadelphia jazz living legend in his own right, will be offically kicking off Jazz Philadelphia’s Summit 2019 with a keynote address on “The 21st Century Jazz Musician.”

The great Philadelphia saxophonist Odean Pope, MAAF’s 2017 Living Legacy honoree, will keep things going into Friday afternoon, leading a discussion on jazz’s history and facilitating educated speculation about its future, before giving way to the day’s closing event, a celebration of the late, great Philadelphia saxophonist, Grover Washington, Jr.

By that point Odean Pope’s weekend will just be getting started. The next evening—Saturday October 12th—Pope will premier an ambitious new project he’s calling Sounds of the Circle at La Rose Jazz Club in Germantown.

Pope, who grew up in Philadelphia and was influenced by everyone here from Coltrane and McCoy Tyner to Jimmy Smith, the Heath brothers, Benny Golson, and Lee Morgan (and almost too many more to name), aims to pay tribute to seemingly everyone who played a role in shaping his musicality and musicianship. Pope’s goal seems to be to somehow re-manifest not just the sound but the feeling of the North Philadelphia jazz scene in the middle of the 20th century.

It’s hard to talk about a project so wide in scope in anything but broad strokes, but, rest assured, it will be ambitious. And compelling. Odean might show up at La Rose with a time machine, prepared to bring all the folks mentioned above back from the past. All I know is that I can’t afford to miss it.

And then, as if the foregoing weren’t sufficiently mind-blowing and face-melting—here comes the revolution! The October Revolution, and not the very bloody one you may have learned about in school. In this version of the October Revolution, Princess Anastasia is safe and sound and grooving to the music of cosmic transcendence, free jazz.

The October Revolution is the Ars Nova Workshop’s marquee event and it best represents what artistic director Mark Christman and the Workshop stand for. The New York Times has called the event “a State of the Union for free improvisation and avant-garde composition.” In other words, if Odean Pope’s Sounds of the Circle doesn’t sufficiently transport you in space and time, perhaps, like Lenin, the October Revolution is what you’ve been building to all along.

This revolution will not be televised but it will go on throughout October, with 13 different performers and ensembles playing venues throughout Philadelphia. Fans of The Bad Plus might look forward to reuniting with Ethan Iverson, who manned with the piano for 17 years as one-third of the Minneapolis-based genre-bending super-group. Iverson will appear with trumpet great Tom Harrell, Ben Street (bass), and Eric McPherson on Thursday October 17th at the Caplan Recital Hall at UArts.

In the early ’70s, Charles Tolliver was one of the brightest young trumpeters in jazz. He studied at Howard University and then moved to New York in 1964, playing and recording with Jackie McLean. Tolliver was on quite a few excellent advanced hard bop records in the mid-’60s, played with Gerald Wilson’s Orchestra in Los Angeles (1966-1967), and was a member of Max Roach’s group at the same time (1967-1969) as the compatible Gary Bartz. In 1969, Tolliver formed a quartet called Music Inc. that often featured pianist Stanley Cowell and was on a few occasions expanded to a big band. Tolliver and Cowell founded the Strata East label in 1971, which released many fine records in the 1970s. Although it was an era when there was a serious shortage of talented young trumpeters (prior to the rise of Wynton Marsalis), Tolliver after the mid-’70s maintained a low profile. Charles Tolliver, whose fat tone was influenced by Freddie Hubbard while his ideas display bits of John Coltrane, has recorded as a leader for Impulse (two songs from a 1965 concert), Black Lion, Enja, and Strata East. ~ Scott Yanow

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/tag-charles-tolliver

Dizzy Gillespie, when asked in a Downbeat magazine

interview with Herb Nolan, “what trumpet players do you hear today whom

you like”, Dizzy’s reply, “Charles Tolliver – I like him”. Charles

Tolliver, entirely self-taught, is a remarkable talent who has gained an

outstanding reputation as a trumpetist, bandleader, composer, arranger,

and educator. Born in Jacksonville, Florida in 1942, his musical career

began at the age of 8 when his beloved grandmother, Lela, presented him

with his first instrument, a cornet, and the inspiration to learn.

After a few years of college majoring in pharmacy at Howard University,

and formulating his trumpet style, Charles began his professional career

with the saxophone giant Jackie McLean.