SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2020

VOLUME NINE NUMBER TWO

B.B. KING

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BRANDEE YOUNGER

(October 31-November 6)

CHRIS DAVE

(November 7-13)

MATANA ROBERTS

(November 14-20)

NATE SMITH

(November 21-27)

T.J. ANDERSON, JR.

(November 28--December 4)

KEYON HARROLD

(December 5-11)

NICOLE MITCHELL

(December 12-18)

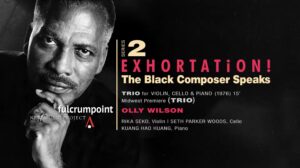

OLLY WILSON

(December 19-25)

KENDRICK LAMAR

(December 26-January 1)

JONATHAN BAILEY HOLLAND

(January 2-8)

WENDELL LOGAN

(January 9-15)

DONAL FOX

(January 16-22)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/olly-wilson-mn0002157522

Olly Wilson

(1937-2018)

Artist Biography by James Reel

The only description of Olly Wilson's works in one major reference source simply declares, "Wilson draws freely upon avant-garde styles and techniques in his music, showing a predilection for unorthodox formal procedures and instrumental combinations." What this doesn't point out is that Wilson's wide-ranging style and technique were the natural result of his diverse musical background: playing jazz and orchestra music professionally, working with electronic music during a stimulating early phase of that movement, and studying African music during a 1971 Guggenheim Fellowship to West Africa.

Born in St. Louis, Wilson played jazz piano in his home town, as well as bass in St. Louis orchestras. He obtained his Bachelor of Music from Washington University in St. Louis in 1959, his master's degree from the University of Illinois in 1960, and his Ph.D. from the University of Iowa in 1964. His composition teachers included Robert Wykes, Robert Kelley, and Phillip Bezanson. Wilson did postdoctoral study in electronic music in 1967 at the University of Illinois Studio for Experimental Music, and one year later his electronic composition Cetus garnered him a prize in the very first International Electronic Music Competition.

He went on to write not only electronic pieces, but works for chamber ensembles and orchestra as well. Commissions came from the Black Music Repertory Ensemble, New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, and Boston Musica Viva.

In the 1960s Wilson taught at Florida A&M University and the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, but in 1970 he settled for the rest of his academic career into the University of California at Berkeley. He received Guggenheim Fellowships to West Africa in 1971 and the American Academy in Rome in 1977; the year 1991 found him in Italy again, thanks to a residency at the Rockefeller Foundation Center in Bellagio.

Olly Wilson died in March 2018 in Oakland, California; he was 80 years old.

https://www.oberlin.edu/news/composer-olly-wilson-founding-father-electronic-music-oberlin-dies-80

Composer Olly Wilson, Founding Father of Electronic Music at Oberlin, Dies at 80

Wide-ranging influences included spirituals, jazz, serialism, and more.

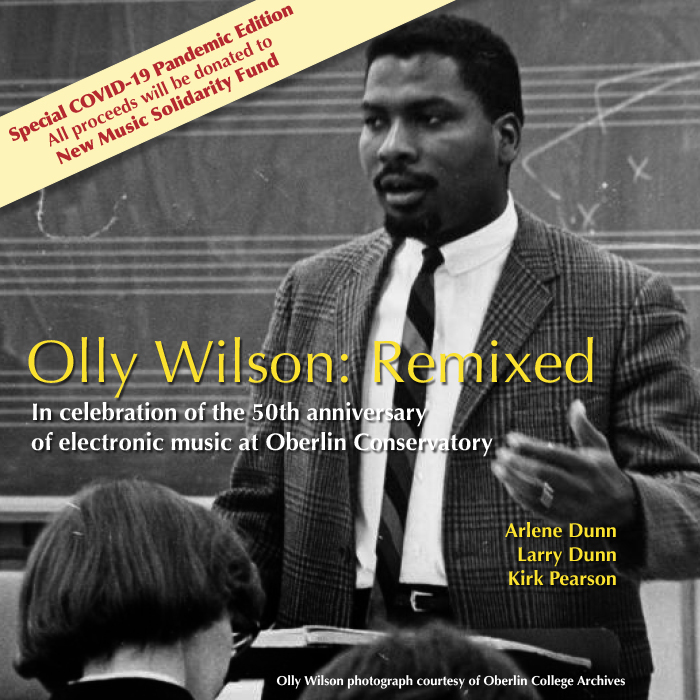

In 1973, Oberlin’s newly christened Technology in Music and Related Arts Department became the first undergraduate electronic music program in the United States. Five years earlier, the groundwork for TIMARA was laid by Olly Wilson, an associate professor of composition who had been raised on a world of diverse sounds and was intent on exploring new sonic worlds of his own.

A member of the Oberlin Conservatory faculty from 1965 to 1970, Wilson taught music theory and composition courses, as well as the first known course on African American music. He is widely credited for having observed in the late 1960s that the basement of Bibbins Hall would make a fine setting for an electronic music studio. TIMARA has called that basement home since its founding.

Wilson went on to a long and varied career as a professor and administrator at the University of California, Berkeley, and he remained an active and acclaimed composer for many years. Wilson died March 12, 2018, at age 80.

“Olly Wilson was a pioneer in many wonderful capacities, and the TIMARA Department is honored to consider him the inspirational origin of our program,” says Tom Lopez ’89, an associate professor in TIMARA and former student in the program. “His open-minded and experimental approach to working with electronic media, particularly in conjunction with acoustic instruments, continues to this day in the creativity I see in our students.”

Born and raised in St. Louis, Wilson took to playing music in his school and church, where his father was a highly regarded tenor in the choir. By his early teens, the younger Wilson played piano for the choir and became proficient on the clarinet and bass. An avid jazz performer in area clubs, he once played piano as part of a house band for a young Chuck Berry. “We played, but it really didn’t make any difference because you couldn’t hear us,” Wilson later shared as part of an oral history project at Berkeley. “He just wiped us out—bang, bang, bang—on his guitar.”

Initially inspired to pursue a career as a high school band director, Wilson saw his horizons expanded as an undergraduate at Washington University in St. Louis, where he was one of seven black students offered a scholarship—an early sign that segregation was beginning to erode. He played jazz piano and classical bass, earning spots in the university’s orchestra and chamber orchestra. By his sophomore year, he realized he wanted to be a composer.

An advocate of Bartók, Hindemith, and Stravinsky early in his musical career, Wilson eventually found himself gravitating toward the twelve-tone serialism of Arnold Schoenberg, which he fully indulged throughout his graduate studies in composition at the University of Illinois, where he earned a master’s degree. In 1964, he added a PhD from the University of Iowa.

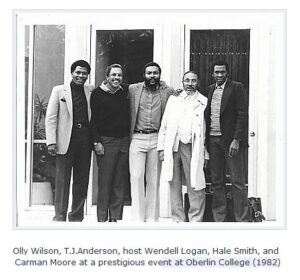

Oberlin College Archives

After teaching for several years at Florida A&M University, Wilson was appointed to the Oberlin faculty in the summer of 1965, the first full-time black faculty member in the conservatory’s history. He also served as advisor for the Black Student Union and brought prominent black musicians to his classes.

A prolific composer, Wilson contributed works to Oberlin’s long-standing Festival of Contemporary Music every year he was on the faculty. One such work was a choral piece called In Memoriam Martin Luther King Jr., which included fragments of speeches by King set to intermittent electronic music. It was performed by the Oberlin College Choir under Robert Fountain.

Wilson’s compositions tended to showcase wave after wave of influences, from the church music and spirituals of his childhood to the jazz, blues, and traditional African sounds he embraced throughout his adult life. Increasingly, he became enamored of pairing acoustic instruments with electronically produced sounds.

In 1967, Wilson and numerous other faculty composers who shared an interest in electronic music sought funding to purchase equipment and support research. They earned a grant from the National Science Foundation that by 1969 yielded a collection including computers, testing instruments, Moog and ARP synthesizers, a mixer, and a patch bay. The ARP continues to be used by Oberlin TIMARA students today.

In 1968, Wilson won first prize at the International Electronic Music Competition at Dartmouth College, the first competition ever devoted to electronic music.

Wilson himself was among the first composers to create in Bibbins’ basement studios, according to his own notes from the 1969 composition Piano Piece, written for prepared piano and stereo tape. “Piano Piece … is a musical essay in which I attempted to create a musical dialogue between an acoustic piano and electronic sound,” he wrote. “The electronic portion of this composition was realized at the then-new Electronic Music Studio at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and, to my knowledge, is the first piece completed in that studio."

Wilson’s signed and dated score to Piano Piece resides in the Oberlin Conservatory Library. Piano Piece appeared on the 2008 Centaur recording Music from the TIMARA Studios.

By 1970, Wilson left Oberlin for Berkeley, where he taught for 22 years while assuming administrative duties including department chair, faculty assistant for Affirmative Action, assistant chancellor for international affairs, and associate dean of the graduate division.

A Guggenheim Fellowship—one of two Wilson earned over the course of his career—afforded him the opportunity to study the roots of African American music in West Africa in 1971-72. This experience and others helped raise Wilson’s awareness of international affairs and ignited his advocacy of educational opportunities for students from Third World countries. He led initiatives to promote international exchanges with China and create opportunities for black South African students to study at Berkeley.

Wilson returned to Oberlin multiple times, including as composer in residence at the Teachers Performance Institute in July 1971, as part of a weeklong symposium on black American composers in 1981, and for the retirement of longtime TIMARA professor Gary Lee Nelson in 2007.

“The university is the 20th century patron of the arts for composers,” he told The Oakland Tribune in 1989. “This means, of course, that one is also a teacher. Some composers don’t like the university. They find it stultifying. On the other hand, people like me thrive on the university. I like ideas. I love teaching and being stimulated by intellectual ideas. For me, the university is a very exciting place.”

Wilson was honored in 1974 by the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He earned a Rome Prize in 2008.

In 1983, Wilson’s Voices was performed by the Cleveland Orchestra in a concert at Severance Hall in honor of Dr. King. Even in retirement, Wilson remained a well-received composer whose works were performed by orchestras throughout the world. Among his commissions were pieces for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic.

Upon hearing of Wilson’s death, faculty and students in the TIMARA Department created a memorial in his honor outside the studios’ main entrance: a computer set up to play music he had written.

Wilson is survived by his wife, Elouise Woods Wilson; a son and daughter; and six grandchildren.

Tags:

http://www.bruceduffie.com/ollywilson.html

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Born in 1937, the St. Louis, MO, native completed his undergraduate training at Washington University (St. Louis), continuing with his masters studies at University of Illinois (returning later to study electronic music in the Studio for Experimental Music), and received his Ph.D from the University of Iowa. His composition teachers included Robert Wykes, Robert Kelley, and Phillip Bezanson.

His work as a professional musician included playing jazz piano in local St. Louis groups, as well as playing double bass for the St. Louis Philharmonic, the St. Louis Summer Chamber Players, and the Cedar Rapids Symphony. He has taught on the faculties of Florida A&M University and Oberlin Conservatory of Music, as well as his current position of professor of music at University of California at Berkeley, where he has taught since 1970.

Wilson's works have been performed by major American orchestras such as the Atlanta, Baltimore, Saint Louis, Detroit, and Dallas Symphonies, along with such international ensembles as the Moscow Philharmonic, the Netherlands Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. He has received commissions from the Boston, Chicago, and Houston Symphonies, as well as the New York Philharmonic and the American Composers Orchestra. He has been awarded numerous honors including: the Dartmouth Arts Council Prize (the first international competition awarded for electronic music for his work Cetus); commissions from the NEA and Koussevitzky Foundation; an artist residency at the American Academy of Rome; several Guggenheim Fellowships; a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship; and the Elise Stoeger Prized awarded by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. In addition to being a published author (Wilson has written numerous articles on African and African-American music), Wilson often conducts concerts of contemporary music. In 1995, Wilson was elected in membership at the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Olly Wilson's music is published by Gunmar Music (G. Schirmer, Inc.).

In February of 1991, Olly Wilson was in Chicago for the premiere of his work Of Visions and Truth. It was commissioned by the Center for Black Music Research in 1989 with funding from the Borg-Warner Foundation for the Black Music Repertory Ensemble. While he was in the Windy City, I had the privilege of speaking with Wilson at his hotel. Here is what transpired that afternoon.

Bruce Duffie: You are both composer and teacher of music. How do you divide your time between those two very taxing occupations?

Olly Wilson: I discovered a long time ago that in this country the university is really the patron of the arts — at least patron of the composers. I happen to really enjoy the university, so it worked out very well for me. I’m fortunate enough to teach at a university that recognizes the necessity for creative time, and the teaching load is such that I’m able — and indeed expected — to do creative work. So because of that understanding, I’m able to focus on my creative work at the same time I’m teaching. Right now I’m on sabbatical leave, so I’ve got the entire year to focus on writing several commissions.

BD: At the university you’re teaching composition and theory?

OW: I’m teaching composition and theory, and I teach courses in the whole range of theory and analysis and composition. I also teach courses in African-American music, so that that’s another part of it. But I rotate my teaching schedule so that I’m able to still write music as well.

OW: That’s right.

BD: In the theory and composition courses, are these training more composers or are these training musicians who want to understand music more?

OW: It’s both. On the undergraduate level, it’s the general student. It’s the general music major, as well as, occasionally, a course for non-majors. Then on the graduate level, we have a Ph.D. program at Berkeley. These are really very, very sophisticated composers, people who have really committed themselves and are usually fairly sophisticated about the craft at that point. So there is a judicious balance between the somewhat esoteric technical side of things and the general thing for the general student, and a continuum in between.

BD: Do you think it would be a good idea for any performer — a fiddle player in an orchestra or just a general music teacher — to take a course in composition?

OW: I think it’s probably a good idea, depending upon what their expectations are, to study with a composer to see how the composer thinks, what parameters interest the composer in working on a piece, and to find out about the range of things that a composer deals with in creating something new. I think would be interesting for a performer or the general listener, as far as that’s concerned, assuming that both the composer who was teaching the course and the student understood the dimensions of the course, so the composer wouldn’t expect more creativity out of a person who simply doesn’t have that kind of creative bent, and the student didn’t expect a different kind of thing out of the composer.

BD: You could design a course that’s just the mechanics of composing.

OW: That’s right, or perhaps periodically have a person sit in on the composition seminar that a composer is giving to other composers, even just observing the energy exchange that goes on — the kind of things that a composer attempts to center in on. In the creative arts, you can’t really teach creativity. What you can do is to try to understand what a young composer’s attempting to do and try to help him or her do it better; to develop the technique, the technique being the ability to bring to fruition, to bring to reality what you imagine. The real task is to make the imagination real. Teaching compositional technique is teaching those kinds of skills, so that the person who imagines something is able to write it down, or is able to express to the performers in some kind of way what he or she wishes them to do.

BD: Where is this delicate balance between the inspiration and the technique?

OW: It’s hard to exactly pinpoint that. In some aspects of a composition the focus is on technique — such as if you wanted something to be effective, but you wrote something that was impossible for the performers to do, or you over-scored it or it was too thick. You expected it to be clear. If you wrote three or four lines and you wanted each of them to be heard, but they’re all in the same register — say in the lower register, especially the trombones — you’re not going to hear them. [Both laugh] So understanding that and knowing exactly what to do and how to re-orchestrate that, or how to redevelop that or how to change the texture, the timbre, in order to create the musical gesture that you intend, is really the secret. On the other hand, sometimes there’s inspiration to the basic idea. It’s possible to have technique and not have any imagination, and as a result you have something that might be interesting as an exercise, but doesn’t capture one’s imagination, or more importantly, it doesn’t communicate anything to the listener.

BD: Then that becomes not such a great piece of music?

OW: That’s right. It becomes very mediocre if you aren’t able to inspire.

BD: So each person has to have both of these talents?

OW: Exactly, exactly.

BD: Is this, perhaps, what contributes to the greatness of a piece — when both aspects have strength?

OW: I think absolutely — when they both are at a sublime level. When you have both the mastery of the technique and the imagination, then you’re able to really communicate something.

BD: Thinking a little bit about inspiration, when you’re sitting at your desk with the blank score and all the lines are waiting to be filled in, are you always in control of the pencil, or are there times when the pencil is controlling your hand across the page?

OW: There’s constantly this idea to get in contact with what someone has referred to as a ‘sonorous image’ — your inner ear, the ability to hear things, to imagine things in sound. What you do with the pencil is to simply write that down so that you have an abstract representation of what you have imagined.

BD: But you’re more than just a copyist, are you not?

OW: Oh, much more, much more than the copyist. The imagination is what you hear, but then you are doing it, creating it, writing it down. There are different kinds of composers. Apparently Mozart was the kind of composer that had such a brilliant sonorous image that much of his writing was almost like a medium. It was so clear that he could simply write it out as the first copy and things were perfect. But that was certainly the extraordinary exception. There are very few musicians like that. Beethoven, on the other hand, was the kind of composer who struggled. He wrote something and then he changed it; he wrote something and then he changed it again. He was attempting to reach that ideal state, but he reached that after many trials. I think most mortals are closer to Beethoven in terms of that relationship of trying to realize that ideal that you have imagined, as opposed to Mozart who apparently didn’t struggle that much at all but was just able to let it flow out. I certainly am a composer who works over and over, although I’m sure all composers have certain moments of inspiration when they hit that one idea. Frequently for me it’s the beginning kernel of the idea after I have tried to decide how I am going to start the piece. As you said, when you confront this blank piece of paper and you’re starting on a new piece, what do you do? Well, you pray for rain. [Both laugh] You seek to try to invoke some kind of inspiration, and you do that in a number of different ways. People have a number of different schemes they do. Sometimes they study other music. Sometimes they might sit at the piano and improvise. Sometimes I might just take a walk or I might try deep reflection. At any rate, you keep doing that until you are able to get something and you say, “Aha, this is the idea. This is what I want to do.” You get your concept. Then the process of composition is making that concept clearer and clearer. Part of that process is sometimes writing things down, and rejecting and accepting and rejecting and accepting and honing, much like an artist or a sculptor does. Then other times, once you have the clear idea of what it is, then you’re working it out... and that’s also an acceptance and rejection kind of process.

BD: Are you ever completely surprised by where an idea will lead you?

BD: As you’re working on the piece, or even when you start, are you conscious about how long it will take to perform the piece?

OW: In general I usually am at first. After you determine what the basic idea is going to be, then you have a general sense of the overall length. But then again that might vary because the idea may be made in further working out. Then you get involved and you say, “Oh this needs to go this way.” So you work that out, and as you work that out suddenly the piece becomes longer. Or it may be that you do a piece, and then after you’ve done parts of it you realize that your intentions would be better served by making certain overall changes. The piece that I’m doing that’s going to be premiered on Wednesday night is a case in point. This piece is a song cycle, and originally it consisted of four songs. But in the course of working out the songs, I discovered that I really needed some instrumental interludes. I had the four songs — the main part of the work — and then I realized for a number of different reasons — pacing, tempo, the character of each song — I shouldn’t have Song A following Song B. I needed to have something in between. So I then wrote several instrumental interludes and now it’s a larger cycle. There are interrelationships between the interludes and the main body of the work.

BD: So it all hangs together.

OW: Exactly, yes.

BD: When you’re working with a score and you’re tinkering with it, how do you know when to put the pencil down and launch the work?

OW: It’s sometimes difficult to let go, but when you decide, “That’s it, I’ve said all I can say; I’ve done all I can do in this particular composition so I’d better just let it have its own life,” then you turn it over to performers. Hopefully you’re fortunate to shepherd it through its first performance, to help the performers and the conductor understand the conception that you had initially.

BD: Do you want the performers to play it exactly right, or is there a little room for interpretation?

OW: I want the performers to follow my directions. I’m very conscious of what I’ve done, and I want them to do it exactly that way, but I also recognize that any performance is, to a certain degree, a collaboration. One hopes for a musical and sensitive conductor, such as Kay Robertson who’s doing this piece, and outstanding performers. Here I’ve got William Brown and Donnie Rae Albert and Bonita Hyman who are all outstanding performers. I recognize their musicianship and their interpretive skills, so within the framework there’s a certain amount of leeway for them — how long are you going to do this phrase, how do you turn this phrase, how phrase one is related to phrase two, slight increments of intensity. I might say mezzo piano in the first phrase and fortissimo in the second phrase, but what does mezzo piano really mean in absolute terms? So it becomes relative, and a sensitive performer is able to take those directions and shape them. If they really understand your conception, maybe they will even show you different ideas about the conception that you hadn’t thought of exactly in that same way. Each performance is also a revelation for the composer.

BD: Tell me the joys and sorrows of writing for the human voice.

OW: The joys are that it is the most marvelous instrument. It’s so intimate. It’s so close to oneself. It is able to express the most profound sentiments in the most significant ways. On the other hand, it is a human voice and is subject to the frailties of individuals. Because it’s so intimately connected with people, if they have a cold or if they aren’t feeling well that day, it’s not like an instrument that you can play and you control completely. Although instruments, really, in the broadest sense and in the best hands become an extension of the person’s sentiments, the human voice has some very dramatic and interesting possibilities. It has some limitations, and there are certain things that are very difficult to do — although in this century, I, along with many other composers, are certainly pushing the voice to its limit. You find fantastic performers that are able to achieve almost anything you ask them to do.

BD: How do you know when you’ve pushed the voice too far?

OW: Frequently, if it’s too far the vocalist will let you know. [Both laugh] If you don’t know already yourself, the vocalist will let you know. But adventuresome vocalists who are on the cutting edge will frequently encourage you toward pushing it to the cutting edge. William Brown, who is a tenor, is a person with whom I’ve collaborated for several years on several different pieces. One of my strongest pieces is called Sometimes for Tenor and Electronic Sound. It’s about a twenty-five minute piece and is a tour de force for the tenor and electronic sound. I ask the tenor to do a wide range of extremely virtuosic techniques. He’s all the way up to about a C and D and a falsetto E flat, and at the same time rhythmically he’s asked to do a lot of very, very interesting, complicated things.

BD: Did you write it with William Brown in mind?

OW: I wrote it with William Brown in mind, as a matter of fact, and on Pieces for Voice and Tape, some of the tape includes pre-recorded vocal parts that he actually performed. So it was really his piece. It has been performed by other people, though, because it’s been around since 1976. He’s performed it a number of times, and there are other performers who have also performed the piece.

* * * * *

BD: You’ve worked quite a bit with electronics and electronic tape, and you had a piece that actually won the first competition of electronic music.

OW: Right.

BD: I wonder... can there be a competition for the ‘best piece of music’ in any given framework?

OW: [Laughs] Of course not, but human nature being what it is, people decide periodically to have contests of various sorts. People enter them for various reasons, and this was in the early years. The piece won in 1967, and it was quite an experience. It was actually my first piece of electronic music I had written. But at the time, electronic music was relatively new, so I was very pleased with the piece. Of course, the technology now has moved light years away from the technology that we were employing at that time.

BD: Are there things you can do now that you couldn’t do then, or is it just simply easier and faster to do those effects?

OW: Both. It’s easier to do them, and of course with digital synthesis now, it’s a lot cleaner. You don’t have the ambient noise and the tape hiss that you had with the old equipment. The signal-to-noise ratio was much higher in those old tapes, and yet there were some interesting things about it. But the technology now allows you to do different things, and to do some of the older things faster. Yet if you go back and listen to some of that early electronic music — even going all the way back before tape manipulation to the musique concrète of the forties and fifties, and then moving up to the synthesizers in the sixties and so forth, there are certain qualities about that music that you can only do with that music, with that media; so it’s different. It’s certainly a lot more sophisticated now than it was then. I haven’t been writing that much electronic music for about the last ten years because I’ve been fortunate to be asked to do several orchestra pieces.

BD: You don’t feel that writing for orchestra is looking back, and writing for electronics is looking forward?

BD: I was asking you before about interpretation and leeway on the part of performers. When you write an electronic piece, it will be absolutely the same each time it is played. Is this a good thing or a bad thing, or just a thing?

OW: I think it is just a thing, and it depends on whether it’s a piece only for electronic tape, or for electronic tape and live performer — or whether it’s a piece for electronics to be performed live. It’s capable of doing that now. As a matter of fact, one of the things that’s happening in electronic or digital synthesis of sound now is the development of what’s referred to as interactive performance. This is the kind of technique where an electronic sound source can be programmed to respond to the nuances of the spacing, the tempo, and the dynamics of a live performer.

BD: So then you’re getting electronic interpretation?

OW: You’re getting electronic interpretation, according to certain rules, and that’s an interesting challenge. I’ve seen some examples. I have a colleague, Barry Vercoe, who works at MIT, who’s been working on this quite a bit there and at IRCAM in Paris. He’s developed this interactive system where you can play a Bach suite on the flute, and you have a Yamaha-like instrument — a harpsichord, for example — to accompany the flute that plays live. It’s programmed so it responds to it as a live accompanist would. It’s really fascinating, some of the technique that’s going on.

BD: Will it put a lot of keyboard players out of work?

OW: No, live keyboard players need not worry about that because it’s a different kind of thing. But it is interesting and it is interactive, and I think that’s more the wave of the future.

BD: So electronics are continually developing?

OW: Oh, of course. Technology always does, and technology always has its own rules and its positive things. But it’s not a panacea. Electronic music has been around for years. I first became involved in the early to middle sixties, and now, almost thirty years later, ninety per cent of the music and sound that you hear on television is produced electronically one way or another. But still, live instrumentalists are thriving and performing in all kinds of genres of music because it is something special. There’s something about the quality of the human spirit that also loves the acoustic sound. It’s not an either/or; I think it’s clearly a both/and.

BD: So you’re optimistic about the whole future of music?

OW: Oh, yes. I’m optimistic about the whole future of music. I tend to be an optimistic person. There are a lot of things that I’d like to see be better. As a composer I’d like to have more performances. I have been fortunate recently to have a number of performances, although the Chicago Symphony hasn’t performed my work yet. They’ve got to do that! They ought to do that.

* * * * *

BD: You’re perhaps inundated with commissions. How do you decide which ones you’ll accept and which ones you’ll either postpone or turn aside?

OW: I try to accept those commissions that I really would like to do. At this point in my life I am fortunate to have a number of different commissions, and of course the biggest problem is time. Even though I’m on sabbatical and even though at the university I do have this balance of teaching as well as creative work, still I have other responsibilities and it does take time. I’m not exactly the fastest composer in the world anyway, so I try to judiciously accept commissions that I really want to do.

BD: Then what is it you look for?

OW: A lot of times it has to do with the ensemble. The best commissions are the ones that are sort of carte blanche, “We want you to do a piece,” especially a piece either for orchestra or for chamber group. Right now I have a commission from the National Endowment for the Arts to do a viola concerto for Marcus Thompson. [See my Interview with Marcus Thompson.] That was something I wanted to do, and I applied directly to NEA. That’s something Marcus and I had been talking for about for a long time, and it worked out. So I’m beginning that now that I’ve finished this piece for the Black Music Repertory Ensemble.

Thompson presents world premiere of Viola Concerto by Wilson

Clarise Snyder

July 12, 2012

Stuart Low, reviewer for The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, wrote: …“Olly Wilson’s Viola Concerto, dazzlingly performed by Boston soloist Marcus Thompson, was a more serious affair. Skillfully and innovatively written for the instrument, it often calls for hammered or vigorously scrubbed bow strokes that help the viola’s dark tone project. The concerto’s atonal lines tend to unfold in tight, chromatic steps — a great help to a violist zipping around this large instrument in quick runs. Wilson, a highly acclaimed Berkeley, Calif., composer, also takes advantage of the viola’s lyrical side in the concerto’s elegiac middle section. Searing and haunted by turns, it was eloquently delivered by Thompson.”

Wilson’s Viola Concerto was commissioned by the National Endowment of the Arts and written for, and dedicated to, Marcus Thompson. Wilson is professor of music at University of California at Berkeley. He has received numerous honors and awards from the American Academy in Rome and the American Academy of Arts and Letters and Guggenheim and Rockefeller Foundation Fellowships. His works have been performed by major American orchestras and international ensembles.

Then I’ve got a commission from the New York Philharmonic. As part of their one hundred fiftieth celebration I’ll be doing a piece for them. And there are several other pieces that I’m commissioned to do within the next couple of years.

BD: So you say you haven’t done anything for the Chicago Symphony yet, but you have had the Boston Symphony and now you’ve got New York!

OW: Boston, New York, Cleveland, Saint Louis — almost all of the major symphonies have played some of my music, with the exception of Chicago!

BD: I hope it’ll happen, but the point I was making is that there are many composers — even those who have recordings — and they don’t get any of the big orchestras to play their music. So you’re very fortunate.

BD: What advice do you have for young composers coming along?

OW: I think young composers should follow their own muse and study as much as they can. By study I mean listen — my advice is to listen to as much music that interests you and to study as many scores as you possibly can. My musical background is steeped not only in the European classical tradition, but in the African-American tradition. I found listening to a great deal of music — in my case a great deal of jazz and so forth, and playing and getting involved, immersing oneself in the musical experience as much as possible — is the best way for inspiration. It sensitizes you a great deal to what’s going on around you, and it makes you critical. Any creative person has to be critical. You have to be critical of yourself, and in order to develop that kind of skill you have to know a lot. You have to listen to a lot. You have to have experienced a lot. This is done by playing music and making music — either as a performer or a conductor — listening a lot, reading a lot about music, and immersing yourself in all of the traditions as much as you can. I find inspiration comes from a wide range of sources, and you can’t always predict where it’s coming from.

BD: Does it come for you even from your students?

OW: Oh, sure! It comes from my students and from my colleagues at the university. You asked earlier about the university and how one juxtaposes or balances the responsibilities of a professor and at the same time fulfills the drives of a creative artist. Even though they recognize, as I did, that the university is the twentieth century patron of the arts, I have colleagues who say that they could never survive in the university because there are too many other things that are distractions. In my case, I don’t think of it that way. It’s not a distraction; I find that it’s intellectually stimulating. I find it also inspiring because of the fact that you can go and here somebody giving a lecture on the latest advances in physics, or somebody talking about philosophy or an entirely new approach to geopolitics. I find that all stimulating, and in funny ways I think it keeps you alert. It certainly becomes an inspiration for me to pursue my art.

BD: As an African American composer, whenever we listen to a piece of yours, are you helping to express African American ideas, or is it just simply part of the universal music that you are presenting?

OW: Music is experience consciously transformed, and because my experience has been an African-American experience, I think it expresses that. But that is a very, very complicated kind of thing which is inclusive. It includes a lot of different things including the full range of human experience at the end of the 20th century living in the United States. Having said that, if you listen to music on the other side, there may not be discernible aspects of that music that you say, “Aha, that’s clearly from African American tradition.” In some instances, in some of the music, you might be able to discern it and in other instances you aren’t able to discern it. I would hope that you would be able to discern something that made sense, something that communicated something of the human spirit. To that degree it’s universal, but the universal always comes from the particular. What really makes it universal is that somebody has looked very deeply at their specific human experience — which is very culturally bound and culturally based. But what comes out of that is something which has meaning to you, and that becomes universal because the human experience is so common in so many levels.

BD: Is the music that you write, or any concert music, for everyone?

OW: Of course. The idea of a creative person — certainly my idea — is to attempt to communicate. There are two drives a creative person has. One is to create, and the other is to communicate. You want to communicate to anybody who can hear it and anybody who can appreciate it, so you’re constantly dealing with that. The first drive, I think is primary because even if you weren’t successful — even if I had no commissions, even if I were not fortunate enough to have my work performed by outstanding ensembles like the excellent repertory ensemble that’s performing Wednesday night — even if that were not the case I would still create because I’ve got an inner drive to create. I also want to communicate, but I want to communicate on my terms. The difference would be though I want to communicate, I don’t start with the fact that I want to communicate, figure out what people like and then try to do that. I start out with my inner drive, my inner concept of what makes sense, and then hope that people will understand what I’m attempting to do.

BD: Do you have the audience in mind at all when you’re writing?

OW: I have the audience in mind in a general sense, but not in a specific sense. I’m so involved with the dynamics of trying to make sense out of this musical universe that I’m trying to create. I’m also the audience, and I’m also listening back and saying, “This works and this doesn’t work.” If you’re fortunate to reach that moment when you say, “Ah, this really works,” then I assume that’s going to work for the audience, too. But I’m not consciously thinking about the audience when I’m writing a piece. I’m consciously thinking about the piece and what makes sense within that piece.

OW: Yes I do, very much so. As an American composer, I feel very much a part of the tradition of American composers, and specifically African American composers — a tradition which is much older than many people are aware. It goes all the way back to the early part of the nineteenth century with composer-performers like Frank Johnson, who was an excellent band leader — one of the first band leaders and composers, writing music that was both quasi-popular and at the same time was also outside of the popular, for the salon as well. It goes all the way up to the end of the nineteenth century with Dvořák and Harry Burleigh, and through the twenties with William Grant Still and William Dawson, and later on with Howard Swanson and then people of my own generation like George Walker, Hale Smith and T.J. Anderson, and people who were my colleagues and contemporaries, and some former students like Wendell Logan. [See my Interview with George Walker, and my Interview with Hale Smith and T.J. Anderson.] All of this is in addition to being part of the general contemporary American music movement. Obviously there’s been an impact from Stravinsky and influence by a number of other composers who have been active. There has been the impact of Varèse on my work in various ways, and I’ve been influenced by the music of Berio. [See my Interview with Luciano Berio.] But I’ve also been influenced by the music of Charlie Parker and, to different degrees, John Coltrane and Miles Davis. So it’s all of those things that have been the sum total of my musical experience.

BD: Is composing fun?

OW: Composing is fulfilling. It’s fun and it’s also frustrating. It’s a challenge — in Michelangelo’s terms, ‘the agony and the ecstasy.’ It’s both of those. When you come to those creative solutions for problems that you have, it’s just absolutely ecstasy! It really is marvelous! On the other hand, when you are struggling to achieve that goal you’re your own best critic. When you know that this is not quite up to the standard, it is agony. So it is both exhilarating and also capable of casting you into utter despair at times. You can understand both sides of it, and you try to maintain an equilibrium and say, “Well, today I didn’t do so well, but maybe tomorrow I’ll do better,” and you keep at it.

BD: Do you go back and revise scores?

OW: I don’t do that very much. I try to move on to the next piece. Occasionally if there’s a real miscalculation in a performance — maybe the orchestration wasn’t right — I may make some minor changes here and there. But I have not been the kind of composer who does a lot of serious revisions. As you know, history is full of composers who’ve done that. I don’t do that very often. I think, “This piece reflects the way I was feeling at that time. Even with its imperfections, let’s move onto the next level. The next piece is a new opportunity.”

BD: So rather than fix an old piece, you’d rather write a new piece?

OW: Exactly. And in most instances, by the time I’ve finished with a piece I’m satisfied with basically what it’s done. There may be a little thing, something here or there that is minor, but for the most part I’m pretty satisfied with the output before I release it.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] There are no pieces lurking in the early part of your catalog that you want to disown?

OW: No, but there are pieces in the early part of my catalog that I say, “Yeah, but I was a student then.” [Both laugh] There are pieces that I wouldn’t do now that I did in 1959 and so forth, but there are some early pieces which I still consider inspired, so it’s good.

* * * * *

BD: You’re teaching at U.C. Berkeley?

OW: Right. I’ve been there twenty years, as a matter of fact, since 1970.

BD: Is there a real difference between the west coast school and the east coast school?

OW: I don’t think so. Given the nature of communications and the ability of people to travel back and forth, I don’t think there ever was a real strong difference. In the sixties and the seventies there was the presence of several strong figures in the west coast who approached music differently, and some strong figures in the east coast. If you recall, in the sixties in terms of contemporary American music, probably the leading intellectual leader was Milton Babbitt at Princeton with a certain kind of approach toward composition. The whole notion of the post-Webern total serialism, total determination and so forth — these ideas were prevalent certainly in the eastern academies. At the same time in the west, particularly around San Francisco and also, to a different degree, in LA where Schoenberg was living, you had a number of people who were supporters of John Cage who were also adherents of applying more indeterminacy. [See my Interview with John Cage.] As a result of that, people began to associate Cage and a prior California composer, Cowell, who was also iconoclastic, and also looked to the east and different ways of approaching these ideas instead of the extension of the Germanic tradition. At least philosophically, perhaps some ideas were redefined and reinterpreted because they weren’t precisely the way they were from Asia, but grew out of Zen Buddhism. [For more on the Asian influence, see my Interview with Lou Harrison.] At that time there was such a clear difference in philosophical approaches to composition, and ideas associated with the east coast and the west coast, people thought of it in terms of east and west. But at the same time that was going on, Roger Sessions, who represents another trend of very deterministic music, was also living and working in California, at Berkeley, as a matter of fact. So that’s never been absolute, and there’s always been a certain amount of exchange. Since then, there have been a number of different ideas that sort of co-exist on both coasts in different ways, so that at this point there is no single dominant school or idea that informs and determines contemporary music, even within the academy.

BD: We now have this instantaneous communication, as you were talking about, and something that is played in Berkeley can be heard even simultaneously in New York and all over the country, and indeed, all over the world.

OW: Exactly.

BD: Is this helping to coordinate music, or is it breaking down the individual styles and making it too homogeneous?

OW: On one hand, one might suspect that, because that’s what technology does often. If you look at folk cultures and look at popular cultures, it certainly does do that even on an international level. In the written music tradition, that’s not necessarily the case because we’re so historically self-conscious that people are so aware of being different. Instead of there being a single line, there are now multiple lines at the same time. Five or ten years ago, John Rockwell in The New York Times declared that minimalism was the way to go, and a number of composers such as Phil Glass and Steve Reich rose to ascendancy. [See my Interviews with Phillip Glass, and my Interviews with Steve Reich.] But even at the same time that was going on, Elliott Carter was still going strong, and there were still composers who were influenced by his way of writing one way or another. [See my Interview with Elliott Carter.] The fact of the matter is that there are many, many composers who are not swayed by any of those major movements, or highly touted movements, but simply follow their own muse. In fact, we’ve got a creative eclecticism, and I think that’s sort of the norm now. I serve on juries for various kinds of things for young composers, and I don’t see any one single line. I see composers feeling free to listen to the music of George Crumb or Copland or Babbitt or Schuller, or to the music of T.J. Anderson or Olly Wilson, and they come up with their own solutions. [See my Interview with George Crumb, my Interview with Milton Babbitt, and my Interviews with Gunther Schuller.] I think that’s healthier than the days when people were so conscious of style that they felt they had to adhere to either this style or the other style.

BD: So you encourage young composers — or any composers, really — to stick to their convictions?

OW: Sure, exactly, because I don’t think you can create unless you are convinced by your own conventions.

BD: When you serve on juries, what do you look for in a new musical work?

OW: You look for some individuality. In the first instance you look for competence in working for the media that you have chosen. Then you look for individuality, a creative spark that is unique and stimulating and that reflects a particular perspective.

BD: But you don’t want it to be different just to be different?

OW: No, not different just to be different. That path has already been gone down. That was one of the things that used to happen in Darmstadt in the late sixties and seventies. Every year somebody would come out with innovations for innovation’s sake, which became absurd after a while, and nobody came anymore because it became so far out. You look for a real creative spark, something that communicates musically and artistically in sound. That’s really the ultimate criteria. Now for a person who’s able to do that in an innovative way, that’s fine. Or a person who’s able to do it working within a more traditional or more conservative means is fine.

BD: Is there any chance that we’re getting too many young composers coming along?

OW: I don’t think so. I think society has a way of taking care of itself. A number of people come to the university to study composition, and the world can only support so many composers. So by the end — after graduation, or certainly after a master’s degree — they move to something else. Some people drop out of music altogether, but having had that discipline and that experience, they listen to music and frequently support music. That’s important, too.

BD: It’s obvious that the technical proficiency of performers is getting better, year after year. Is their musicianship getting better also?

OW: I don’t know. Since I’ve been so impressed at the difference between young performers now and the way it was, say, twenty or twenty-five years ago, it appears that the musicianship is getting better. But I think that has to do with attitude and technical proficiency. Twenty-five years ago, to find young performers right out of the conservatory or right out of the university who were willing and able to perform very, very difficult music and with the same kind of aplomb that they approach the traditional repertoire was few and far between. But now you can find them, so I’d like to believe that it’s probably a combination of those factors.

BD: Thank you for coming to Chicago. I’ve been wanting to meet you for quite a while, and I’m glad that you’re here.

OW: Thank you for having me

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in his hotel in Chicago on February 4, 1991. Portions were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1992 and 1997, on WNUR in 2005 and twice in 2012, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2005 and 2009. This transcription was made and posted on this website early in 2013.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio. You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.

https://www.american-music.org/page/Wilson

|

2015 Honorary Member

He taught at Florida A&M University from 1960 to 1965 and then joined Oberlin’s Conservatory of Music faculty. There he created a course in African American music and established an electronic music studio – the first ever program in electronic music at a music conservatory – in addition to teaching theory and composition. In 1970 he joined the faculty at University of California, Berkeley, where he taught until 2002 while also serving as a tireless advocate for diversity in the arts. While there he received a Guggenheim grant to study music in Ghana. This inspired an orchestral piece titled Shango Memory, in celebration of the Nigerian deity, and an influential article on the ways in which the cultural memory of African ideas were reflected in music by African Americans. Wilson was a member of the Academy of Arts and Letters and was the recipient of two Guggenheims as well as the Rome Prize. His many commissions and compositions included electronic, symphonic, and chamber works. |

Society for American Music

Post Office Box 75073

Seattle, WA 98175

(206) 601-4062

email: sam@american-music.org

https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/hold-on-a-celebration-of-the-life-of-olly-wilson/Hold On—A Celebration of the Life of Olly Wilson (1937-2018)“The role of any artist is to

reinterpret human existence by means of the conscious transformation of

his experience.” —Olly Wilson, “The Black American Composer” (1972) It is difficult to summarize Olly Wilson’s influence on my life as a composer, scholar, and human. (I had similar difficulty distilling my father’s influence on my life a few years back.) I do want to share some thoughts about Olly Wilson to celebrate his contributions to American music, especially African American music history, and to me personally. TJ Anderson introduced me to Olly Wilson in April 1989 at the premiere of Wilson’s A City Called Heaven, commissioned and performed by Boston Musica Viva. The concert was a mentor to mentor exchange triggered by my acceptance into UC Berkeley’s PhD program in music composition where I would study with Wilson. I sat next to Olly Wilson during the performance where I followed the music with his personal copy of the score. Wilson often discussed Duke Ellington’s largess as an important element of his life and music. I experienced the same largess from Olly Wilson the first day we met. I had heard Sometimes for tenor and tape before this meeting in a composition class with TJ Anderson. I was amazed by the new musical vistas in A City Called Heaven. This piece influenced a few of my first compositions in graduate school. After the concert, I received my first assignment in preparation for graduate school in the fall: Listen to more Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Ligeti, Lutoslawski, and Charlie Parker. There is a tendency to separate morality and music instruction. Music instruction usually focuses on the notes or the historical facts. Wilson’s lessons, by contrast, were holistic. After my first encounter with Olly Wilson, I realized that I had entered into an artist apprenticeship with a master artist. His teaching humanized the learning experience in numerous ways. He was very much aware that I moved to California at the young age of 22 without knowing anyone in the state but him. Something as simple as attending my first San Francisco Contemporary Music Players concert with him via BART from Berkeley was a quick study in Bay Area mass transit. (As someone who only knew the NYC MTA and the Boston T in the 1980s, BART was an alternate universe to me.) The entire trip was a lesson in critical thinking. Teaching critical thinking was not the purpose of the trip, the concert was the goal, but discussions of the performance, notational issues in the music, the music’s effect on the audience and a discussion on choosing a barber—culturally an important decision connected to settling into a new area—were all covered from Olly Wilson’s typical approachable intellectualism. Olly Wilson’s indirect teaching came from merely spending time with him. Months into my new home in California, I was invited to Thanksgiving dinner with Olly and Elouise Wilson, Mr. and Mrs. Bill Bell, and the children of both families. This may have been the first time I realized that thinking critically would not be limited to music or history in graduate school. If you read Olly Wilson’s writings on African and African American music, you will note that his arguments are supported by a combination of facts, observations, and experiences. Even the process of smoking the turkey for dinner received critical assessment. I made the mistake at dinner of saying that the NY Giants would beat his beloved San Francisco 49ers. He wryly asked, “Do you want to bet?” His critical assessment explained the obvious, the Giants were indeed doomed. Details ruled his discussions. Wilson’s knowledge and talent were intimidating, but he was affable. I will never forget the obvious kindness demonstrated by the invitation to Thanksgiving dinner. I cannot recall the number of times Bill Bell asked me if I had called my mother when I saw him on UC Berkeley’s campus after that dinner. Olly Wilson encouraged intellectual curiosity. Olly Wilson encouraged intellectual curiosity. I know that my use of analogies to explain concepts in class are the result of listening to Olly Wilson teach or discuss a variety of topics. All of us who studied with him modeled our teaching accordingly. Anthony Brown (a fantastic composer, performer and scholar whom I consider my older musical brother) and I realized a few years ago that we both prepared our talking points before we called Olly Wilson so that we had something interesting to say. Olly Wilson promoted the model of the composer scholar. Composers who were also musicologists become deeply interested in investigating music’s connections to larger concerns of cultural expression and historical placement. Music composition lessons with Olly Wilson were humanistic. By that, I mean he assessed my music by: 1) what I actually wrote; 2) what I perceived to be its musical intention; 3) how an audience will perceive it; and 4) and whether or not there was a disconnect between those three previous concerns. This may not seem so obviously humanistic, but connecting the human reaction to the music with the construction of the music and the musical concept was a unique approach to me. I use this method to teach composition now. Recently, I spoke with a group of younger composers and shared a representative comment on my music from an Olly Wilson composition lesson. The original opening to my dissertation for orchestra contained pages of music without the strings doing anything. At the time I thought this was radical. Olly Wilson pointed out, “You do realize there are 50 plus musicians in the string section not doing anything? The majority of players of the orchestra are in the strings. The tradition has always used the strings as glue for the orchestra.” His comment reminded me of an important reality. My music was not stylistically wrong but it was poorly conceived for human performers. My take away from that lesson: The human experience is wrapped up in the writing, performing, and witnessing of a musical composition. One is not disconnected from the other. I also learned over time that his concern for humans was not limited to musical issues. Olly Wilson’s largess touched many musicians. While living in 1995, Paris, I met Gérard Grisey for a composition lesson at the Conservatoire de Paris. Grisey’s demeanor visibly changed when I told him that I had studied with Olly Wilson. He was the first of many composers to ask me, “How is Olly?” While teaching in a small college in rural Indiana, I met William Bolcom who was invited as a special guest composer. After telling him my educational background, Bolcom asked, “How is Olly?” During an interview for a teaching position in at a school in the Southwest, I was asked, “How is Olly? Will he give a lecture at our school if you are hired to teach here?” It was obvious to me that Olly Wilson’s reputation was larger than his music. He made numerous personal connections with musicians everywhere. His concern for humans was not limited to musical issues. A particularly important connection for Olly Wilson was his friendship with the famous musician Earl “Fatha” Hines. Fate seemed to connect them together because Hines and Wilson’s father were born on the same day and died on the same day. After Hines’ death, Olly Wilson became the co-administrator of the Hines estate. One of the many special moments I remember working as an apprentice occurred when I had to search for specific charts in boxes of Earl Hines’s band arrangements. Preserving the Hines Estate is an example of a gift of stewardship by Wilson of important artifacts of American music. Likewise, establishing the first electronic music studio at an American conservatory, Technology in Music and Related Arts (TIMARA) at Oberlin Conservatory in 1967, is another important gift to the development of electronic music in America. Generations of musicians have benefited from Olly Wilson’s work in promoting and preserving American music. “The ideal I strive toward as a composer is to approach music as it is approached in traditional African cultures.”—Olly Wilson, The Black Composer Speaks (1978) Traditional West African cultures believe that music is a force and not a “thing,” a concept I learned in Olly Wilson’s African American Music History class. Music’s essence is its affect or functional use. Considering Olly Wilson’s vast musical output, one can easily hear that his music was composed as an intentional force to affect or motivate listeners. I often begin discussions of electronic music in my classes by listening to Sometimes. Even though some of the electronic sounds are unfamiliar to undergraduates, Wilson’s interweaving of live vocal performance and recorded vocal performances of the spiritual, “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” is haunting and arresting. Powerful musical statements in the piece are often rooted in the Black musical tradition in the context of Western art music. The music’s function is to communicate elements of the Black music’s vocal tradition explicitly or implicitly. In Sometimes and Of Visions of Truth, the use of folk songs is a starting point for presenting Black music in an abstract context. Sinfonia, A City Called Heaven, and Hold On use cells of blues riffs integrated in 20th century avant-garde vocabulary. In essence, Wilson’s compositions are demonstrations of the title of one of his important essays, “Black Music as an Art Form.” Music of perceptual interest, Olly Wilson’s works are a powerful voice of American music. Dvorák thought the direction of an American school of composition should be based on Native American and African American folk music, primarily, spirituals. Sometimes, A City Called Heaven, and the slow movement of Hold On fulfill Dvorák’s vision of American Music. At the same time, Wilson’s music ostensibly represents Béla Bartók’s vision of modern composers using a musical language totally integrated with the purity of folk music to create the new way. Great minds help us answer big questions. In Olly Wilson’s case, he explained through his research what makes Black music identifiable. Not defining the music by the performer but by its musical organization and characteristics that allows us to trace elements of Black music in many genres of American music. Wilson’s research and scholarship also addressed related areas of inquiry: What makes Black music an art form? What is the role of the Black composer? His scholarship laid the groundwork for future research in the nature and significant contributions of African Americans to the development of American music. I consider Olly Wilson’s six conceptual approaches to creating music to be the Rosetta stone of Black musical analysis. My first week in Wilson’s African American Music History class, spring 1990, was life changing. Anthony Brown was one of the teaching assistants for the course. Wilson’s lecture on African culture began with a discussion of Black Athena by Martin Bernal, a book, given to me by my father, outlining the African/Egyptian sources of Western European civilization. A thorough discussion of West African culture in the opening week of the course was followed by Olly Wilson explaining his six conceptual approaches to creating music that link sub-Saharan West African music to African American music:

I consider these concepts to be the Rosetta stone of Black musical analysis. It is the key to understanding the organization of music in the African diaspora. Wilson’s work embraces the complexity of the subject making his discussions and explanations more potent. After centuries of convenient or expedited explanations of the nature of African culture and its connection to African American music, Wilson’s work takes the important perspective that this tradition’s artistry demands a more substantive exploration into the complexity of the historical, geographical, and sociologic factors that resulted from the Atlantic slave trade. Wilson’s work illuminates the misunderstanding of what occurred historically so that everyone will understand Black music better. His last published writing appears in the Cambridge Companion to Duke Ellington, in Chapter 5, “Duke Ellington as a Cultural Icon.” After a career of intellectual discovery and exploration, Olly Wilson uses his discussion of Duke Ellington to illustrate how this American icon rose above America’s cultural expectations of his musical output. This chapter points to the essential concern of all of Wilson’s writing through a quote by Thomas Jefferson. In Jefferson’s “Notes on the State of Virginia,” Jefferson states, “Whether they [Blacks] will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved.” Olly Wilson’s life’s work demonstrates the “proof” Jefferson mentions and counters the common negative associations of Black artistic capability embodied in this quote. In a sense, Olly Wilson’s research addressed the artistic residues of America’s original sin evident in a founding father’s writing on the nature of Black musical creativity. “In that sense my music is directly

related to the struggle in that it aspires to inform, motivate, and

humanize my fellow men in their aspirations.”—Olly Wilson, The Black Composer Speaks (1978) Many of us are mourning the huge loss of a talented musician and intellectual. We also celebrate the many numerous gifts Olly Wilson left us. His work demonstrated to all that there was a traceable link to the music made by African Americans and the musical traditions found on the African continent they left during the Atlantic slave trade. African performance practices inform and are readily noticeable in any form of American music connected to the continuum of African American music. There has been a long tradition in this country of individuals identifying characteristics of African American music as weird/funny (minstrelsy) or interesting but non-essential, at best. Sometimes this music is deemed inappropriate in serious musical expression. For example, one of my compositions was criticized for asking a “classically” trained choir to stomp their feet and clap like a tradition African American vocal ensemble. Wilson discussed the importance use of physical body motion in the process of making Black music. The movement is integral to the music. Understanding this concept explains why the Temptations danced while they sang and many traditional Black churches stamp their feet and clap as they sing. The movement is the music. Olly Wilson has demonstrated the strength of African American musical traditions through his compositions. Black music is not limited to one form of musical expression. In the same way that the defining characteristics of a waltz can be heard in music by Johann Strauss, Chopin, Ravel, and the composers of the Second Viennese School, blues expression is heard in the music of Ellington, Louis Jordan, Elvis, the Rolling Stones, and A City Called Heaven. This is an important point. Some limit Black expression to its folk genres, others to American pop recordings. The strength of any culture is revealed in the diversity of its various forms of expression. Black musical expression “exists” if it is identifiable in various forms. When Olly Wilson wrote “The Significance of the Relationship Between Afro-American Music and West African Music” (1974) he provided for us the keys to analyzing and composing music in the African American tradition and in turn, insight into American musical culture. Olly Wilson’s compositions and research were his ultimate answers to every question he raised in his research. He never complained, but I do think that he felt an affinity to Duke Ellington’s dilemma: Famous and respected but not recognized in the same way, at that time. If you believe that Wilson’s work revealed important observations about Black music to have a better understanding of ourselves, then we might consider Wilson’s last essay on Ellington addressing the important issue of implicit bias with respect to assumptions about relevance of music created by African Americans or music created with the influence African American music. Inclusion in concert music is currently under more scrutiny. Olly Wilson was a pioneer. He started teaching at UC Berkeley in 1970 and I was the first composer of African descent, to my knowledge, to enter the graduate program in composition at Berkeley 19 years later in 1989. Olly Wilson paved the way for many people in composition and encouraged serious study of African and African American music in the Academy. Olly Wilson paved the way for many people in

composition and encouraged serious study of African and African American

music in the Academy. Finally, Olly Wilson did have a wry wit, a good sense of humor, and a kind heart. During a class discussion on Louis Jordan, he mentioned the dances that he and his friends did to “Choo Choo Ch’Boogie.” I chuckled a bit like a doubtful nephew which encouraged Olly Wilson to demonstrate by dancing across the stage in Hertz Hall while we listened to the recording. It was a mic drop moment before we started to use this term. He gleefully played for me the lullaby he wrote for his first granddaughter and quietly bragged that he was asked to be the best man at his son’s wedding. Although we mourn Olly Wilson’s death, we can say that he lived life to its fullest and left many gifts that have enriched our lives. In “Duke Ellington as a Cultural Icon,” Olly Wilson described Ellington with words appropriate for its author. This quote seems to speak to Olly Wilson’s wonderful contribution to American society. Thank you Olly Wilson for all that you shared with me and all who knew you. |

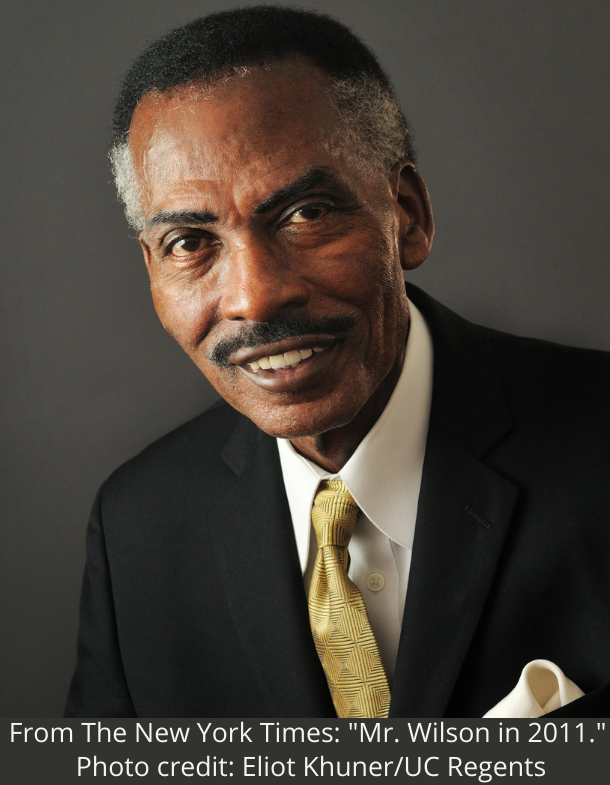

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/23/obituaries/olly-wilson-80-dies-composer-meshed-african-and-western-music.htmlOlly Wilson, 80, Dies; Composer Meshed African and Western Music |

Olly Wilson, an adventurous composer who integrated African, African-American and electronic rhythms, riffs and sounds into Western classical music conventions, died on March 12 in Oakland, Calif. He was 80.

His daughter, Dawn Wilson, said the cause was complications of dementia.

Mr. Wilson, a longtime professor at the University of California, Berkeley, grew up listening to jazz and spirituals. He studied African music in Ghana under one of his two Guggenheim Fellowships, opened an electronic music studio at the Conservatory of Music at Oberlin College in Ohio, where he had formerly taught, and wrote academic papers, including a major essay on the art of black music.

“I see him very much as a musician, composer and a scholar — these things are hard to separate with him,” Ryan Skinner, a musicology professor at Ohio State University, said in a telephone interview. “His music is, in many ways, the resounding of his scholarship.”

In his composition “Sometimes,” Mr. Wilson used the call-and-response tradition of African-American churchgoers to create a dialogue between a tenor singing “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” and a tape that included a distorted recording of that sorrowful spiritual.

In his review of the New York Philharmonic’s performance of “Sometimes” in 1977, Donal Henahan of The New York Times wrote that the tenor William Brown “handled its vocally excruciating demands to gripping effect,” and that the “sibilants, gurgles and moans” from the tape “produce an almost suffocating mood of isolation and sadness.”

Mr. Wilson, whose music was played by orchestras around the world, aligned himself with an African-American musical heritage that includes Frank Johnson, a 19th-century bugler, bandleader and composer; Harry Burleigh, a composer and baritone soloist; and the contemporary composer T. J. Anderson. His other influences, he said, ranged from Igor Stravinsky and Edgard Varèse to Charlie Parker and Miles Davis.

“Music is experience consciously transformed, and because my experience has been an African-American experience, I think it expresses that,” he told Bruce Duffie, a radio producer and interviewer in 1997, when asked if he were conveying African-American ideas in his pieces.

In the early 1990s, Mr. Wilson wrote a viola concerto for Marcus Thompson that had an improvisatory feel, with riffs associated with a jazz saxophone or trumpet and a bluesy middle section. Mr. Thompson said in a telephone interview that, compared with other viola concertos, Mr. Wilson’s was special “because he writes from a completely different medium; he’s a jazz player who’s written all sorts of chamber music.”

The work, titled “Viola Concerto,” had its long-delayed premiere in 2012 with the Rochester Philharmonic. Stuart Low, of The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, called the work “searing and haunting.”

Olly Woodrow Wilson Jr. was born in St. Louis on Sept. 7, 1937. His father was a butler and a cook; his mother, the former Alma Grace Peoples, was a domestic. Theirs was the second African-American family in their neighborhood.

The elder Mr. Wilson, a tenor who sang in choirs around St. Louis, “insisted that all of his children learn to play the piano,” Olly Wilson told an oral history project at Berkeley. “He thought understanding the piano was fundamental.”

Young Olly, who also played the clarinet and string bass, was in an acoustic band as a teenager that played local bars in St. Louis when Chuck Berry arrived one day; this was early in Mr. Berry’s rise to stardom, when he performed with house bands. The band — with Mr. Wilson on piano alongside a drummer, a bassist and a saxophonist — tried in vain to keep up with Mr. Berry, who brought an amplifier to augment his guitar.

“So we played, but it really didn’t make any difference because you couldn’t hear us,” Mr. Wilson said in the oral history. “He just wiped us out — bang, bang, bang — on his guitar.”

Recalling Mr. Berry’s famous duck walk, which made women in the bar swoon, Mr. Wilson said, “We considered that silly music because we were jazz aficionados.” He and his friends were more enamored of Mr. Parker and Mr. Davis.

Mr. Wilson graduated from Washington University in St. Louis with a bachelor’s degree in music, then earned a master’s in music composition from the University of Illinois and a Ph.D. in music composition from the University of Iowa, where his dissertation was a long piece called “Three Movements for Orchestra.”

After teaching at Florida A&M University from 1960 to 1965, Mr. Wilson joined the faculty of Oberlin’s Conservatory of Music. In addition to teaching music theory and composition, he established a course in African-American music as well as the school’s electronic music studio. After his departure, the studio turned into a program known as “Technology in Music and the Related Arts.”

“With electronic media,” he told a music department publication at Berkeley in 1997, “you can work with sound like a sculptor or painter.”

He joined Berkeley in 1970 — where he would teach until 2002 — and soon after received the Guggenheim grant to study music in Ghana. His year in West Africa was the inspiration for an orchestral piece, “Shango Memory,” a celebration of Shango, a Nigerian deity, and what he called the “cultural memory of African ideas reflected in music.”

At Berkeley, he was also an administrator dealing with affirmative action in the 1970s and ’80s and helped diversify the music curriculum.

Mr. Wilson received numerous commissions, including two from the conductor Seiji Ozawa — one when Mr. Ozawa was music director of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, the second when he was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Another commissioned work, for the Boston Musica Viva ensemble, was “A City Called Heaven,” which has elements of swing music, blues, spirituals and boogie-woogie. It was first performed in 1989.

“You can’t think of that piece without being overwhelmed by its imagination,” said Mr. Thompson, who is also a music professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “It’s all based on the spirituality that’s common in the black community. He had the courage and skill to do it, and that’s how black culture appears in the classical canon.”

In addition to his daughter, Mr. Wilson is survived by his wife, the former Elouise Woods; his son, Kent; his sisters Marion Palmer and Barbara Washington; and six grandchildren.

Mr. Wilson described in the oral history how his work as a scholar affected his work as a composer.

“Because I studied African music and the history of African-American music doesn’t necessarily mean that I consciously draw upon that when I do my work as a creative artist,” he said. “But I think the pleasure that that gives me and the understanding that gives me does reflect positively on what I do as a creative artist.”

https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/composer/2781/Olly-Wilson/

Olly Wilson

1937 - 2018

American

Works

Orchestra

Soloists and Orchestra

Large Ensemble (7+ players)

Soloists and Large Ensemble (7+ players)

Small Ensemble (2-6 players)

Chorus and Orchestra/Ensemble

Electronic Works

Complete Works

Listen >

Olly Wilson's richly varied musical background included not only the traditional composition and academic disciplines, but also his professional experience as a jazz and orchestral musician, work in electronic media, and studies of African music in West Africa itself.