SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2020

VOLUME EIGHT NUMBER THREE

BRIAN BLADE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

GIGI GRYCE

(May 16-22)

CLARK TERRY

(May 23-29)

BRANFORD MARSALIS

(May 30-June 5)

ART FARMER

(June 6-12)

FATS NAVARRO

(June 13-19)

BILLY HIGGINS

(June 20-26)

HANK MOBLEY

(June 27-July 3)

RAPHAEL SAADIQ

(July 4-10)

INDIA.ARIE

(July 11-17)

JOHN CLAYTON

(July 18-24)

MARCUS MILLER

(July 25-31)

JAMES P. JOHNSON

(August 1-7)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/james-p-johnson-mn0000142860/biography

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/james-p-johnson-mn0000142860/biography

James P. Johnson

(1894-1955)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

One of the great jazz pianists of all time, James P. Johnson

was the king of stride pianists in the 1920s. He began working in New

York clubs as early as 1913 and was quickly recognized as the

pacesetter. In 1917, Johnson began making piano rolls. Duke Ellington learned from these (by slowing them down to half-speed), and a few years later, Johnson became Fats Waller's teacher and inspiration. During the '20s (starting in 1921), Johnson began to record, he was the nightly star at Harlem rent parties (accompanied by Waller and Willie "The Lion" Smith)

and he wrote some of his most famous compositions during this period.

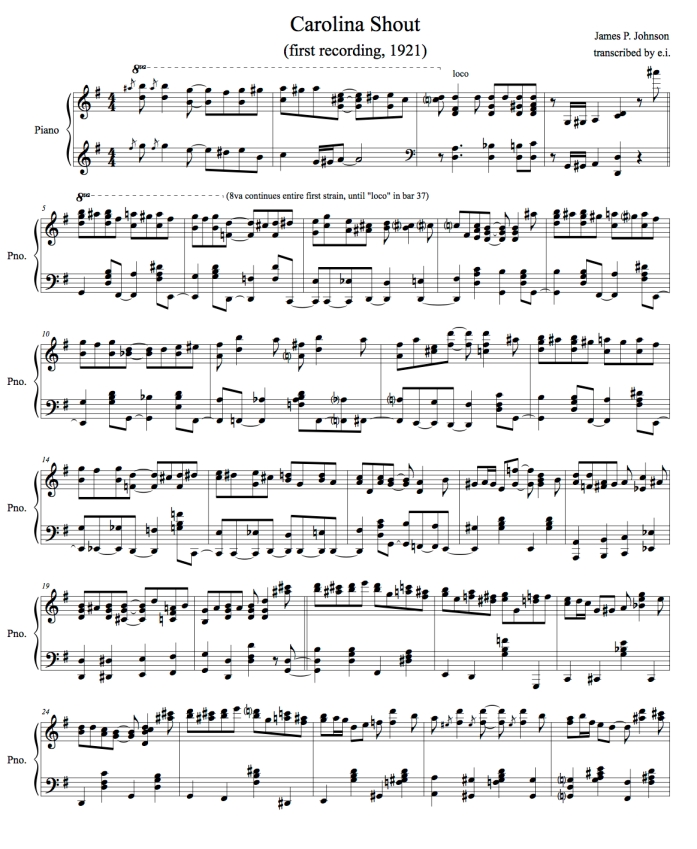

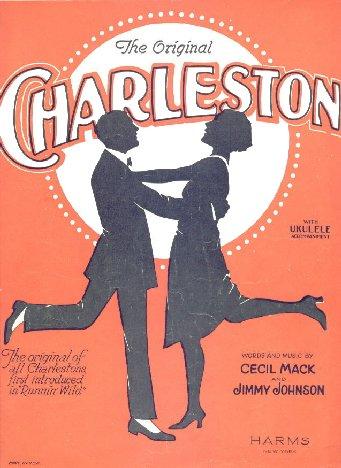

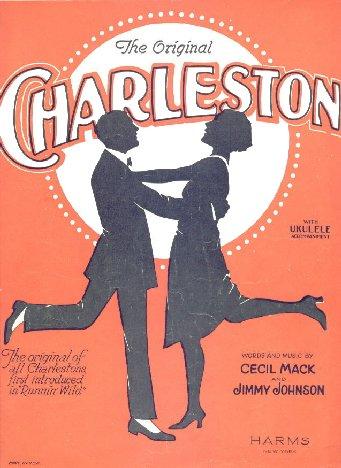

For the 1923 Broadway show Running Wild (one of his dozen scores), Johnson

composed "The Charleston" and "Old Fashioned Love," his earlier piano

feature "Carolina Shout" became the test piece for other pianists, and

some of his other songs included "If I Could Be with You One Hour

Tonight" and "A Porter's Love Song to a Chambermaid."

Ironically, Johnson, the most sophisticated pianist of the 1920s, was also an expert accompanist for blues singers and he starred on several memorable Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters recordings. In addition to his solo recordings, Johnson led some hot combos on records and guested with Perry Bradford and Clarence Williams; he also shared the spotlight with Fats Waller on a few occasions. Because he was very interested in writing longer works, Johnson (who had composed "Yamekraw" in 1927) spent much of the '30s working on such pieces as "Harlem Symphony," "Symphony in Brown," and a blues opera. Unfortunately much of this music has been lost through the years. Johnson, who was only semi-active as a pianist throughout much of the '30s, started recording again in 1939, often sat in with Eddie Condon, and was active in the '40s despite some minor strokes. A major stroke in 1955 finished off his career. Most of his recordings have been reissued on CD.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/jamespjohnson

James P., Lucky Roberts, Willie (The Lion) Smith, and the Beetle (Stephen Henderson), were familiar figures around “The Jungle” (on the fringe of San Juan Hill in the west 60s when this older Negro district was thriving before 1920.) They followed in the footsteps of Jack The Bear, Jess Pickett, The Shadow, Fats Harris, and Abba Labba.

Here and in the later uptown Harlem, the house rent parties flourished and the boys who could tinkle the ivories were fair haired. Willie The Lion recalled those days for Rudi Blesh as follows: “A hundred people would crowd into one seven-room flat until the walls bulged. Plenty of food with hot maws (pickled pig bladders) and chitt'lins with vinegar, beer, and gin, and when we played the shouts everybody danced.” Long nights of playing piano at such festivities gave James P. plenty of practice at the keyboard.

There were two younger jazz pianists who followed Jimmy Johnson around during these Harlem nights. One was young Duke Ellington, fresh from Washington, and the other was James P.'s most noted pupil, the late Fats Waller. The latter cherished the backroom sessions with James P., Beetle, and The Lion.

From about 1915 to the early '20s, James P. made many piano rolls for the Aeolian Company and then became the first Negro staff artist for the QRS piano roll firm in 1921. It was in this connection that he met and became friendly with the late George Gershwin, and ultimately helped him write the music for several shows. Around late 1922 Johnson left the piano roll field to make phonograph records. His first waxing was also probably the first jazz piano solo on records. This was the Victor pressing of “Bleeding Heart Blues.”

Most of Johnson's playing was solo, but through the years there were periods of considerable length when he served bands in the piano chair. He played for some time with the famed James Reese Europe's Hell Fighters at the Clef Club in Harlem.

Johnson's composing activities are as noteworthy as his piano style. In the '30s he wrote a long choral work, “Yamecraw,” which was made into a movie short starring Bessie Smith. Other serious works of his include “Symphonie Harlem”; “Symphony in Brown”; “African Drums” (symphonic poem); “Piano Concerto in A-Flat” (which he performed with the Brooklyn Symphony); “Mississippi Moon”; Symphonic Suite on St. Louis Blues; and the score to “De Union Organizer (with a Langston Hughes libretto).

One of Johnson's most famous and best known tunes was “If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight,” written in 1926, the year he was accepted for membership in ASCAP. Jazz fans will recall “Old Fashioned Love,” “Porter's Love Song (to a Chamber Maid),” “Charleston, Carolina Shout,” “Caprice Rag,” “Daintiness,” “The Mule Walk,” and “Ivy.”

J.P. at one time or another made records for every major label, with the exception of the two youngest-Capitol and Mercury-and many of his older sides have been reissued. Most of his sides are found under his own name, but there are miscellaneous dates where a jazz band called him in to handle the important piano chore. He recorded with McKinney's Cotton Pickers on Victor and was selected by Hughes Panassie on the Frenchman's sessions at Victor during a visit to the U.S. The Hot Record Society picked James P. for their Rhythmaker record date in 1939.

James P. Johnson was one of the great jazz pioneers and his contributions take an important place among the jazz classics.

James P. Johhnson died in New York on Nov. 17, 1955.

Source: James Nadal

https://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/program/runnin-wild-biography-james-p-johnson

Only a few pop tunes in the twentieth century have launched a dance

craze as wild as “The Charleston,” a tune that still evokes images of

Jazz Age flappers and Charlie Chaplin silent movies, bathtub gin and The Great Gatsby. The

gentle genius who wrote “The Charleston”—James P. Johnson—remains all

but invisible today and is rarely remembered by anyone except a handful

of musicians. “The Charleston” was Johnson’s big hit, but he wrote many

far more ambitious compositions.

Joining The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to pay tribute to this almost-forgotten legend are piano master Dick Hyman and William Warfield, a star of theater and film. Dick Hyman first met and performed with James P. in Greenwich Village in the 1950s; Hyman went on to study and perform Johnson’s work for decades. William Warfield recreates the atmosphere of 1920s New York in his portrayal of James P. Johnson, using Johnson’s own words, excerpted from an interview by Tom Davin titled, “This is Our Story of The Father of Harlem Stride Piano, and first published in Jazz Review magazine.”

James P. Johnson is the musical genius most often credited with originating the uniquely East Coast style of piano playing known as “Stride.” In his lifetime, Johnson composed and recorded jazz tunes, show music, movie scores and major symphonic works. Johnson was the first black artist to breakthrough the color barrier and cut his own piano rolls for a major label. The great singer Ethel Waters said of him, “All the licks you hear now originated with James P. Johnson—and I mean all the hot licks that ever came out of Fats Waller and the rest of the hot piano boys; they’re all faithful followers and protégées of that great man, Jimmy Johnson.”

Before World War I, in the first decade of the century, a piano could be found in almost every home in America. At the time, it was as common to own a piano, as it is to have a television set or Internet access, today. Most people couldn’t imagine living without one. Newspaper ads pitched pianos with the hard sell, “What is a home without a piano?” A good piano player was always popular; after all not everyone who owned a piano could play it well.

James Price Johnson was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey in 1894. He grew up to be an unassuming man with a gentle disposition. He had perfect pitch and a powerful left hand; he was a quick learner at the piano and he practiced hard. Johnson said he would spend hours playing piano in a dark room to become completely familiar with the keyboard. He would sometimes put a bed sheet over the keyboard and force himself to play difficult pieces through the covering in order to develop his sense of touch. Some of these tales may be apocryphal, but Johnson’s originality and virtuosity stand out over a century later.

James P. Johnson recalled his early life:

“When we lived in Jersey City I was impressed by my older brother’s friends. They were real ‘ticklers,’ cabaret and ‘sportin’ house’ players. They were my heroes. They led what I thought was a glamorous life; they were welcome everywhere because of their talent. If you could play piano, you went from one house to another. Everybody made a fuss about you. They fed you ice cream and cake, all sorts of food and drinks. In fact some of the biggest men in the profession were known as the biggest eaters. At an all-night party you started eating at 1:00 AM, had another meal at 4:00 AM, and sat down to eat again at 6:00 AM. Many of us suffered later because of the eating and drinking habits started in our younger socializing days. But that was the life for me when I was seventeen.

“When a real smart ‘tickler’ would enter a place, say in winter, he’d leave his overcoat on and keep his hat on, too. We used to wear military overcoats, or a coat like a coachman’s—blue double-breasted fitted to the waist and with long skirts. We’d wear a light pearl-grey Hamburg hat set at a rakish angle, then a white silk muffler and a white silk handkerchief. Some carried a gold-headed cane. Players would start off sitting down, waiting for the audience to quiet down, then they’d do a run up and down the piano of scales and arpeggios, or if they were real good they might play a set of modulations, very off-hand as if there was nothing to it. Some ‘ticklers’ would sit sideways at the piano, cross their legs and go on chatting with friends nearby. It took a lot of practice to play this way. Then without stopping the smart talk or turning back to the piano, he’d attack without warning, smashing right into the regular beat of the piece. That would knock them dead.”

“We moved from Jersey City to New York in 1908 when I was 14 and still going to school in short pants. We lived on 99th

Street in Manhattan, and I used to go to a cellar run by a fellow named

Souser. He was a real juice hound. They had a four or five-piece band

there, but after 2:00 AM they pulled the piano out to the middle of the

floor and Souser would play terrific rags. Times he’d let me play, and I

hit the piano until 4:00 AM. I kept my schoolbooks in the coal bin

there, and I went to school after a little sleep.

“In the same year, I was taken to Baron Wilkins’ place in Harlem. Another boy and I let the legs of our short pants down to look grown-up and we sneaked in. Who was playing there but Jelly Roll Morton! He had just arrived from the West and he was red-hot. The place was on fire. We heard him play ‘Jelly Roll Blues.’ I remember he wore a light brown Melton overcoat with a three-hole hat to match it. He had two girls with him.

“In Jersey City I heard good piano from all parts of the South and West, but I heard real ragtime when we came to New York. Most East Coast playing was based on Cotillion dance tunes, stomps, drags and ‘set-dances.’ They were all country dance tunes, like my ‘Carolina Shout.’”

“In New York, a friend taught me real ragtime. His name was Charley Cherry. We played Joplin, then I copied him, then he corrected me. When I went to Public School #69 I was allowed to play for the assembly and for the minstrel shows put on there. In New York, I got to hear a lot of good music for the first time. Victor Herbert and Rudolph Friml were popular, and I used to go to the old New York Symphony concerts. A friend of my brother who was a waiter used to get theater tickets from its conductor (Josef Stransky) who came to the restaurant where he worked. That was when I first heard Mozart, Wagner, Beethoven and Puccini. The full symphonic sounds made a big impression on me.

“The other sections of the country never developed the piano as far as the New York boys did. The people in New York were used to hearing good piano played in concerts and cafes. The ragtime player had to live up to that standard. They had to get orchestral effects, sound harmonies, and all the techniques of European concert pianists who were playing their music all over the city. New York ‘ticklers’ developed the orchestral piano—full, round, big, widespread chords in tenths, a heavy bass moving against the right hand. The other boys from the South and the West played in smaller dimensions like thirds played in unison. We wouldn’t dare do that, because in New York the public was used to better playing.”

By 1912 Johnson was making a living playing piano for rent parties

and cabarets in a tough neighborhood in Manhattan where Lincoln Center

is today. Johnson soon rose to prominence in the highly competitive

world of New York piano players, who were inventing a new form that came

to be known as “stride piano.” This solo piano style combined the

strong left hand of Boogie-Woogie with the lyrical right-hand arpeggios

of ragtime.

Johnson was well established in the relatively small world of Harlem Stride Piano by the 1920s, when he took a talented teenager by the name of Fats Waller under his wing, gave him piano lessons and a home away from home. Fats Waller’s bubbling show-biz personality captured the imagination of the nation, and he soon became swept up in the bright light of fame and fortune. A deep bond of affection remained between the two giants of stride piano until Waller’s death at an early age. Johnson’s influence can be readily heard in the Waller tune “Smashing Thirds,“ performed here by Dick Hyman and The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

In the 1920s Johnson accompanied top stars like Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters. He toured Europe with the Plantation Revue, and in 1923 composed the score for a hit Broadway show, Runnin’ Wild. Two hit tunes came out of this show: The title tune, “Runnin’ Wild,” is often widely played by jazz and string bands today, and “The Charleston.” Johnson recalled first seeing the Charleston danced at a dive called the Jungles Casino in New York in 1913. Johnson recalls:

“The Jungles was just a cellar without fixings. The people who came…were mostly from Charleston, South Carolina. Most of them worked…as longshoremen or on the ships. They danced hollering and screaming until they were cooked. They kept up all night or until their shoes wore off, most of them after a heavy day’s work on the docks. The Charleston was a regulation cotillion step without a name. While I was playing for these Southern dancers I composed a number of “Charlestons”—eight in all, all with that damn rhythm. One of these later became my famous “Charleston” on Broadway.

Willie “The Lion” Smith was one of the formidable stride piano players James P. Johnson faced in the hot competition of “cutting contests” at Harlem clubs and parlors in the 1920s. Johnson said “The Lion” earned his nickname fighting on European battlefields in World War I. But “The Lion” claimed it was James P. Johnson who gave him the moniker. To prove the point, “The Lion” took to calling James P., “The Brute.” In turn, Smith and Johnson joined forces to come up with a nickname for their young protégé Fats Waller; they called him “Filthy.” “Fingerbuster“ is an aptly named virtuoso piece by “The Lion,” which he undoubtedly used at “cutting contests” to establish his dominance. Here, Dick Hyman takes it at its intended prestissimo tempo.

In 1917 James P. Johnson cut the first in a series of historic piano rolls for the Aeolian and QRS Music Roll companies. Three years later in 1920, Johnson met George Gershwin while both artists were making piano rolls at a hundred dollars a session. These two great figures of American music came from vastly different backgrounds—separated by enormous racial barriers, but they shared a mutual ambition to write “serious” music on large American themes. Both continued to study classical music while playing and composing jazz and popular tunes. Gershwin was a great admirer of Johnson, and the rest of the Harlem piano men, and Gershwin frequently crossed the race barrier to hear them play. George Gershwin acknowledged his high esteem for Johnson and the enormous influence Johnson’s work had on his own by including the “Charleston” theme in his Concerto in F.

In 1928, four years after Gershwin presented his first serious work Rhapsody in Blue, Johnson debuted his first symphonic work in concert at Carnegie Hall with Fats Waller at the piano. Yamekraw, a Negro Rhapsody is dedicated to a black community near Savannah, Georgia called Yamekraw. You can hear strains of down-home blues, stomps, church meetings and spirituals in this ambitious work. Our show features a rare recording of the piece, performed by the composer himself, followed by the band’s original arrangement for The Jim Cullum Jazz band and Dick Hyman.

More about the music on this show:

“A-flat Dream“ dates from 1939, and is performed here as a Dick Hyman/John Sheridan duet. The tune starts off with a boogie-woogie bass line in the first section, and switches to a more typically Johnsonesque texture.

“Ain’tcha Got Music?” and “You’ve Got to Be Modernistic” are both examples of what Johnson refers to as a broad “orchestral” style of stride piano, heard here filled out in arrangements created by John Sheridan for Dick Hyman and The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. A further example of the “orchestral style is “Caprice Rag,“ performed as a two-piano Hyman/Sheridan duet here. Johnson’s “Snowy Morning Blues“ is given a meditative solo reading by Dick Hyman, evoking a feeling true to its title.

Photo credit for homepage image: James P. Johnson, public domain.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1997

https://www.songhall.org/profile/James_P_Johnson

Composer and pianist James Price Johnson, the father of stride piano, was born on February 1, 1891 in New Brunswick, New Jersey. He attended New York public schools and received private piano study. His professional debut as a pianist came in 1904. In the early 1910’s, Johnson worked as a pianist in summer resorts, theatres, films and nightclubs before forming his own band in 1920, called the Clef Club. The Clef Club toured throughout Europe with the vaudeville show Plantation Days.

Returning to the States, Johnson was the accompanist for such renowned singers as Bessie Smith, Trixie Smith, Mamie Smith, Laura Smith andn Ethel Waters. In the 1930’s, he took his stride style to the movie screen and composed scores for films including Yamacraw.

The stride style that influenced such legends as Duke Ellingon and Fats Domino, stresses a strong "swinging" bass while moving in a "stride fashion" with a single treble melody. Introduced in 1924 with "The Charleston", combined Ragtime syncopation and the smooth progression of jazz with livelier upbeat rhythms and a swinging bass that helped usher in the next decade's genre.

Johnson’s discography is equally distributed with serious works as well as hit jazz standards. His works include “Symphonic Harlem”, “Symphony in Brown”, “African Drums”, “Piano Concerto in A-flat”, “Mississippi Symphonic Suite on St. Louis Blues”, “Yamacraw”, “City of Steel”, “De Organizer”, “Dreamy Kid”, “Kitchen Opera”, “The Husband”, “Manhattan Street Scene” and “Sefronia’s Dream.”

His popular catalog includes the hit songs “Old Fashioned Love”, “Don’t Cry Baby”, “Charleston”, “If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight”, “Stop it Joe”, “Mama and Papa Blues”, “Hey, Hey”, “Runnin’ Wild”, “Porter’s Love Song to a Chambermaid”, “Snowy Morning Blues”, “Eccentricity Waltz”, “Carolina Shout” and “Keep Off the Grass”.

A member of the League of Composers and the NAACC, Johnson composed primarily by himself but did have a few collaborations with lyricists including Mike Riley, Nelson Cogane and Cecil Mack.

James P. Johnson died in New York City on November 17, 1955, however the stride musical style he introduced continues to reinvent music of every genre.

https://syncopatedtimes.com/james-p-johnson-forgotten-musical-genius/

Piano professionals required a specific set of ostentatious accessories in order to be taken seriously. A dramatic silk-lined overcoat was integral to the presentation of a modern major piano professor. Removed with a flourish, the garment was placed with great ceremony to display the plush silk lining: “We used to wear . . . a coat like a coachman’s — blue double-breasted fitted to the waist and with long skirts. We’d wear a light pearl-grey Homburg hat set at a rakish angle, then a white silk muffler and a white silk handkerchief.”

When the Student is more dramatically visible than the Teacher, even the most influential mentor and guide might become obscure. James Price Johnson, pianist, composer, arranger, and bandleader, has become less prominent to most people, even those who consider themselves well-versed in jazz piano. He was a mentor and teacher — directly and indirectly — of Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Art Tatum. “No James P., no them,” to paraphrase Dizzy Gillespie. But even with memorable compositions and thirty years of recording, he has been recognized less than he deserves.

Fats Waller eclipsed his teacher in the public eye because Waller was a dazzling multi-faceted entertainer and personality, visible in movies, audible on the radio. Fats had a recording contract with the most prominent record company, Victor, and the support of that label — he created hit records for them — in regular sessions from 1934 to 1943. Tatum, Basie, and Ellington — although they paid James P. homage in words and music — all appeared to come fully grown from their own private universes. Basie and Ellington were perceived not only as pianists but as orchestra leaders who created schools of jazz composition and performance; Tatum, in his last years, had remarkable support from Norman Granz — thus he left us a series of memorable recordings.

Many of the players I’ve noted above were extroverts (leaving aside the reticent Basie) and showmanship come naturally to them. Although the idea of James P., disappointed that his longer “serious” works did not receive recognition, retiring to his Queens home, has been proven wrong by Johnson scholar Scott Brown (whose revised study of James P. will be out in 2017) he did not get the same opportunities as did his colleagues. James P. did make records, he had club residencies at Cafe Society and the Pied Piper, was heard at an Eddie Condon Town Hall concert and was a regular feature on Rudi Blesh’s THIS IS JAZZ . . . but I can look at a discography of his recordings and think, “Why isn’t there more?” Physical illness accounts for some of the intermittent nature of his career: he had his first stroke in 1940 and was ill for the last years of his life.

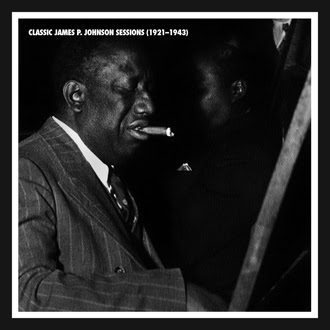

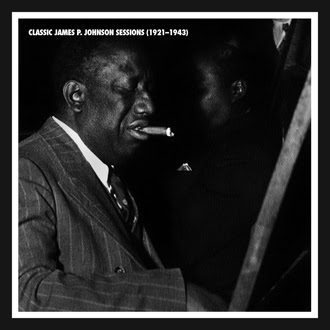

There will never be enough. But what we have is brilliant. And the reason for this post is the appearance in my mailbox of the six-disc Mosaic set which collects most of James P.’s impressive recordings between 1921 and 1943. (Mosaic has also issued James P.’s session with Eddie Condon on the recent Condon box, and older issues offered his irreplaceable work for Blue Note — solo and band — in 1943 / 44, and the 1938 HRS sides as well.)

Scott Brown, who wrote the wise yet terse notes for this set, starts off by pointing to the wide variety of recordings Johnson led or participated in this period.

And even without looking at the discography, I can call to mind sessions where Johnson leads a band (with, among others, Henry “Red” Allen, J. C. Higginbotham, Gene Sedric, Al Casey, Johnny Williams, Sidney Catlett — or another all-star group with Charlie Christian, Hot Lips Page, Lionel Hampton on drums, Artie Bernstein, Ed Hall, and Higginbotham); accompanies the finest blues singers, including Bessie Smith and Ida Cox, is part of jivey Clarence Williams dates — including two takes of the patriotic 1941 rouser UNCLE SAMMY, HERE I AM — works beautifully with Bessie Smith, is part of a 1929 group with Jabbo Smith, Garvin Bushell on bassoon, Fats Waller on piano); is a sideman alongside Mezz Mezzrow, Frank Newton, Pete Brown, John Kirby, swings out on double-entendre material with Teddy Bunn and Spencer Williams. There’s a 1931 band date that shows the powerful influence of Cab Calloway . . . and more. For the delightful roll call of musicians and sides (some never before heard) check the Mosaic site here.

(On that page, you can hear his delicate, haunting solo BLUEBERRY RHYME, his duet with Bessie Smith on her raucous HE’S GOT ME GOING, the imperishable IF DREAMS COME TRUE, his frolicsome RIFFS, and the wonderful band side WHO?)

I fell in love with James P.’s sound, his irresistible rhythms, his wonderful inventiveness when I first heard IF DREAMS COME TRUE on a Columbia lp circa 1967. And then I tried to get all of his recordings that I could — which in the pre-internet, pre-eBay era, was not easy: a Bessie Smith accompaniment here, a Decca session with Eddie Dougherty, the Blue Notes, the Stinson / Asch sides, and so on. This Mosaic set is a delightful compilation even for someone who, like me, knows some of this music by heart because of forty-plus years of listening to it. The analogy I think of is that of an art student who discovers a beloved artist (Rembrandt or Kahlo, Kandinsky or Monet) but can only view a few images on museum postcards or as images on an iPhone — then, the world opens up when the student is able to travel to THE museum where the idol’s works are visible, tangible, life-sized, arranged in chronology or thematically . . . it makes one’s head spin. And it’s not six compact discs of uptempo stride piano: the aural variety is delicious, James P.’s imagination always refreshing.

The riches here are immense. All six takes of Ida Cox’s ONE HOUR MAMA. From that same session, there is a pearl beyond price: forty-two seconds of Charlie Christian, then Hot Lips Page, backed by James P., working on a passage in the arrangement. (By the way, there are some Charlie Christian accompaniments in that 1939 session that I had never heard before, and I’d done my best to track down all of the Ida Cox takes. Guitar fanciers please note.) The transfers are as good as we are going to hear in this century, and the photographs (several new to me) are delights.

Hearing these recordings in context always brings new insights to the surface. My own epiphany of this first listening-immersion is a small one: the subject is HOW COULD I BE BLUE? (a record I fell in love with decades ago, and it still delights me). It’s a duo-performance for James P. and Clarence Williams, with scripted vaudeville dialogue that has James P. as the 1930 version of Shorty George, the fellow who makes love to your wife while you are at work, and the received wisdom has been that James P. is uncomfortable with the dialogue he’s asked to deliver, which has him both the accomplished adulterer and the man who pretends he is doing nothing at all. Hearing this track again today, and then James P. as the trickster in I FOUND A NEW BABY, which has a different kind of vaudeville routine, it struck me that James P. was doing his part splendidly on the first side, his hesitations and who-me? innocence part of his character. He had been involved with theatrical productions for much of the preceding decade, and I am sure he knew more than a little about acting. You’ll have to hear it for yourself.

This, of course, leaves aside the glory of his piano playing. I don’t think hierarchical comparisons are all that useful (X is better than Y, and let’s forget about Z) but James P.’s melodic improvising, whether glistening or restrained, never seems a series of learned motives. Nothing is predictable; his dancing rhythms (he is the master of rhythmic play between right and left hands) and his melodic inventiveness always result in the best syncopated dance music. His sensitivity is unparalleled. For one example of many, I would direct listeners to the 1931 sides by Rosa Henderson, especially DOGGONE BLUES: where he begins the side jauntily, frolicking as wonderfully as any solo pianist could — not racing the tempo or raising his volume — then moderates his volume and muffles his gleaming sound to provide the most wistful counter-voice to Henderson’s recital of her sorrows. Another jaunty interlude gives way to the most tender accompaniment. I would play this for any contemporary pianist and be certain of their admiration.

I am impressed with this set not simply for the riches it contains, but for the possibility it offers us to reconsider one of my beloved jazz heroes. Of course I would like people to flock to purchase it (in keeping with Mosaic policy, it is a limited edition, and once it’s gone, you might find a copy on eBay for double price) but more than that, I would like listeners to do some energetic reconstruction of the rather constricted canon of jazz piano history, which usually presents “stride piano” as a necessary yet brief stop in the forward motion of the genre or the idiom — as it moves from Joplin to Morton to Hines to Wilson to Tatum to “modernity.” Stride piano is almost always presented as a type of modernized ragtime, a brief virtuosic aberration with a finite duration and effect. I would like wise listeners to hear James P. Johnson as a pianistic master, his influence reaching far beyond what is usually assumed.

I was happy to see James P. on a postage stamp, but it wasn’t and isn’t enough, as the Mosaic set proves over and over again. I would like James P. Johnson to be recognized as “the dean of jazz pianists”:

Listen closely to this new Mosaic box set six compact discs worth of proof that the genius of James P. Johnson lives on vividly.

Today, February 2, is the birthday of James P. Johnson (1894-1955), who developed stride piano as an art form within an art form. In his time, piano cutting contests were proving grounds—most often in Harlem apartments—where competing pianists showed their stuff. If James P was playing, their stuff was likely not to be good enough. Johnson’s most famous composition was “Carolina Shout,” a test of a pianist’s swing, power and rhythm. He recorded it several times. Many pianists, critics and jazz historians consider this 1921 version his best:

Reprinted from old DTM; originally posted September 2009, slight updates 2010 and 2014, major edit 2015, latest version 2019.

PDF:

Carolina Shout

Listen:

Audio Player

himself only played it like this the once. One of the most important aspects of the real Harlem Stride tradition is to take the basic material and make it your own.

There were two long interviews with James P. Johnson, one with the

Library of Congress in 1938, and one with Tom Davin in the early 1950’s.

One would hope that they would be generally available someday. Part of

the Davin can be found in The Jazz Review.

In 1986 Scott E. Brown produced the only book-length study. James P. Johnson: A Case of Mistaken Identity still has the most detailed biographical information. (Reportedly a new edition with updated information is in the works.) Brown sought to place Johnson’s vast output in context of his era, hence his provocative title.

A Case of Mistaken Identity also contains a complete discography by Robert Hilbert.

Frank H. Trolle’s Father of the Stride Piano is two small pamphlets: a poorly-edited collection of minor biographical/musicological essays and a discography which was superseded by Hilbert’s.

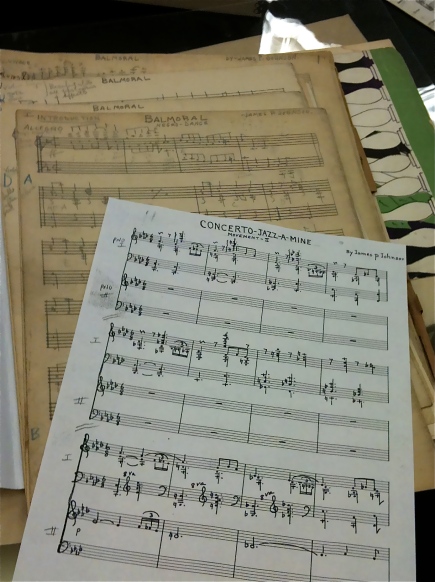

John Howland’s 2009 volume Ellington Uptown: Duke Ellington, James P. Johnson, and the Birth of Concert Jazz goes into fascinating detail about the gestation of Johnson’s best known concert work, Yamekraw: A Negro Rhapsody. There’s also a good deal on the Harlem Symphony and some other Johnson orchestral works. The default companion CD to this music is Victory Stride, which I cautiously recommend.

Yamekraw is like all that Franz Liszt orchestra music that nobody plays: unprofessional and repetitive. By all means, Johnson and Liszt scholars should know this music (and there needs to be more Johnson scholars!) but contemporary enthusiasm for Johnson’s work would be better directed into making every college piano major learn “Carolina Shout” than into asking our major orchestras to program Johnson’s symphonic work. (We don’t want the average concert-goer leaving the hall thinking, “Well, Gershwin really was better than James P., because Rhapsody in Blue is obviously better than Yamekraw.” This is a superficial and Eurocentric reading of the situation.)

Other good information on Johnson scattered about in different places:

Black Bottom Stomp: Eight Masters of Early Jazz and Spreadin’ Rhythm Around: Black Popular Songwriters, 1880-1930 are both by David A. Jasen and Gene Jones. If you are interested in ragtime or early jazz piano you’ve come across Jasen’s name.

Black Bottom Stomp is just terrific. Jasen and Jones seem to get it just right all the time. Their prose style is also wonderfully smooth and occasionally even humorous. Spreadin’ Rhythm Around is excellent as well: This is the best source on Johnson’s significant career as a songwriter for shows.

Henry Martin has a chapter in The Oxford Companion to Jazz called “Pianists of the 1920s and 1930s.” There’s just a couple of pages on Johnson but it’s a rare example of someone trying to make sense of how the printed page interfaces with the records.

The Time-Life Giants of Jazz LP box on James P. Johnson is excellent. The extensive notes on the music are by the vastly knowledgeable Dick Wellstood, who at this point has gotten over his early claims that Johnson didn’t play the blues. (He does manage to get in a dig at boogie-woogie, though, Wellstood’s least favorite piano style.) He collaborates with Willa Rouder, and the solid biographical section is by Frank Kappler. (The Giants of Jazz boxes often have valuable booklets.)

—

[CODA: two sections from 2009 that can’t be changed since they were written in advance of the original Smalls Rent Party and at this point are somewhat “historical”: Annie Kuebler and Ed Berger have died, Aaron Diehl is well-known, and so on.]

—

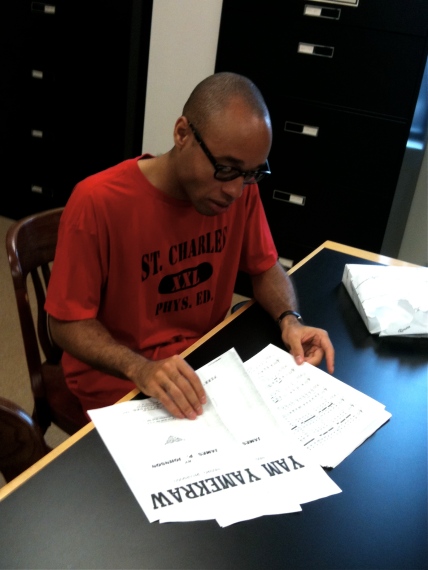

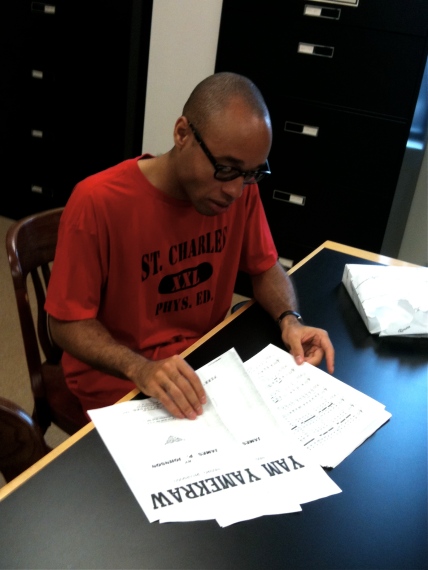

Last week Aaron Diehl (who’s also playing the Last Rent Party) and I

visited the Dana Library at Rutgers University which houses the

Institute of Jazz Studies. I met Dan Morgenstern briefly and Ed Berger

showed us a few of the treasures. Here is Berger’s photo of me holding

Ben Webster’s saxophone while Aaron holds Don Byas’s:

Barry Glover, the grandson in charge of James P. Johnson’s estate, has generously given all of Johnson’s own music collection to the Institute. Glover also has given permission for serious parties to look through and photocopy at will. Annie Kuebler was our helpful guide through boxes and boxes of well-organized Johnson music.

I know that both Aaron and I were overwhelmed with what was there; afterwards we both were grey and exhausted, just trying to deal with the intensity of the experience.

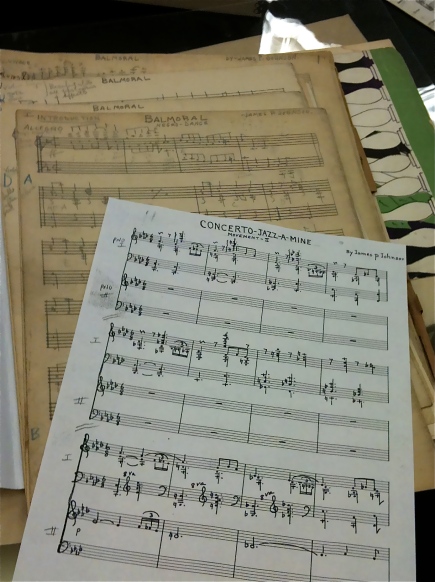

(Aaron sorts out one copy of the Yamekraw rhapsody for each of us.)

One of the things we were looking for was unusual solo piano music to play on Sunday. Aaron was already learning a movement from the Jazz-a-mine Concerto from the record, so he grabbed a holograph of that piece in Johnson’s own handwriting. (He wasn’t sure if he was going to be ready to play it in a week, but what a help to find the score!) (UPDATE: Aaron did play it, extremely well.)

I found a charming drawing-room piece called “Theme in Two Voices” published in 1944. It’s next door to somebody like Anton Rubinstein or Cécile Chaminade—certainly it’s just as good—and I bet Johnson would have gotten a kick out of me playing that surprise at the Last Rent Party.

I don’t know Aaron well, but he turned up in my masterclass one day playing James P. Johnson, and when I asked Loren Schoenberg who I should take a stride piano lesson with he suggested “Aaron Diehl.” Aaron hasn’t really recorded much yet, but you can hear his flawless rendition of another Harlem test piece, Luckey Roberts’s “Ripples of the Nile,” on his MySpace page.

There was a piano next door to the archive. Regrettably, Aaron not only turned out to be as good a sight-reader as me (this almost never happens) but also played a version of “Carolina Shout” that was way better than mine. I can’t really ask Aaron for a lesson—he’s 13 years younger than me, for chrissake—but he gave me one that afternoon anyway. Aaron’s “Carolina Shout” was fluid, improvised, and personal; in comparison, mine was a laborious recreation. (I also got to play it for Fred Hersch on Monday, who made the astute observation that I was playing at one dynamic only, just like the piano roll I was learning from. Obviously, human pianists must use dynamics. I’m trying to get it together but there’s no doubt I’m going to be on the slow side of the “Shout” at the Last Rent Party.)

We don’t know who will play what on Sunday—probably many people won’t play Johnson at all, which is perfectly fine—but that afternoon at IJS Aaron and I enjoyed the fantasy of how awesome it would be to hear everybody play “Carolina Shout.” Just think, if all jazz pianists had to sit in front of each other and play the “Shout”…that would change some things right quick!

I’m definitely going back to IJS once in a while, and I seriously encourage others to explore it as well. The Johnson archive is just a fraction of what they have. More info and contact information is available at the IJS website.

https://sites.temple.edu/performingartsnews/2020/01/27/stride-the-art-of-james-p-johnson/

As one of myriad styles falling under the rubric of jazz, stride is fundamentally an expression of the African American experience. James P. Johnson (1894-1955) pioneered the solo piano style while composing and performing in Harlem during the 1920s. What follows is a brief sketch of the conventions, innovations, and social contexts that produced it.

Stride derives primarily from ragtime in form and content. Tunes comprise three or four independent, sixteen-bar sections or strains. The initial strain features the theme in the tonic; subsequent strains variously treat the original material or present new ideas. Sections collectively called the “trio” modulate to closely related keys, typically the subdominant. Introductions and interludes of four or eight measures are common. Regarding content, left-hand stride patterns follow traditional dances in duple meter, notably the march and polka. Hence the bass often alternates between low notes and midrange chords; the former imitates the tuba while the latter mimics the higher brass and woodwind instruments of marching bands, creating the oom-pah sound associated with folk music.

However, stride represents an evolutionary step in the lineage of jazz, placing greater demands on the performer. The harmonic rhythm and tempo are faster than those of ragtime. Stride also exploits the full range of the instrument. Finally, the style employs an array of pianistic devices, e.g., rapid scale passages, trills, and turns, suggesting that knowledge of classical idioms would be beneficial if not requisite to stride proficiency.

Johnson infused blue notes and call-and-response gestures into stride. Furthermore, the rhythmic feel of his style was more relaxed than ragtime, approximating swing. Heard in the paradigmatic stride piece “Carolina Shout,” these elements allowed Johnson to connect meaningfully with his auditors at clubs and dance halls, many of whom migrated from the Deep South:

“The dances they did at the Jungles Casino were wild and comical—the more pose and the more breaks the better. These Charleston people and the other southerners had just come to New York. They were country people and they felt homesick. When they got tired of two-steps and schottisches (which they danced with a lot of spieling), they’d yell: “Let’s go back home!” . . . or “Now put us in the alley!” I did my “Mule Walk” or “Gut Stomp” for these country dances. Breakdown music was the best for such sets, the more solid and groovy the better. They’d dance, hollering and screaming until they were cooked. The dances ran from fifteen to thirty minutes, but they kept up all night until their shoes wore out—most of them after a heavy’s day’s work on the docks.”

Johnson also cultivated the style while performing at rent parties in Harlem. Held in apartments, these informal gatherings enabled working-class tenants to raise additional money for rent by charging admission. Here we see the music of Johnson providing a modicum of relief in material as well as nonmaterial ways.

We invite you to join us on Wednesday, February 12, to hear stride performances by the studio of Charles Abramovic. In addition to works by Johnson, the program will feature those of his contemporaries, Thomas “Fats” Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, and Zez Confrey.

Consult the following sources for more information:

Barnhart, Bruce. “Carolina Shout: James P. Johnson and the Performance of Temporality.” Callaloo 33, no. 3 (Summer 2010): 841-856.

Berlin, Edward A. “Ragtime.” Grove Music Online. 16 Oct. 2013; Accessed 26 Jan. 2020. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.libproxy.temple.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002252241.

Martin, Henry. “Balancing Composition and Improvisation in James P. Johnson’s ‘Carolina Shout.’” Journal of Music Theory 49, no. 2 (Fall 2005): 277-299.

Robinson, J. Bradford. “Stride.” Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 20 Jan. 2020. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.libproxy.temple.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093

/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000026955.

Rouder, Willa. “Johnson, James P(rice).” Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 24 Jan. 2020. https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.libproxy.temple.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000014409.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Gary Sampsell is a second-year PhD student in the Music Studies program at Boyer College. His research interests include the musical culture of baroque-era Saxony and Austro-German reception of early music in the nineteenth century.

https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/videos/1108906257/

James P. Johnson: Harlem Symphony (1932)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License.

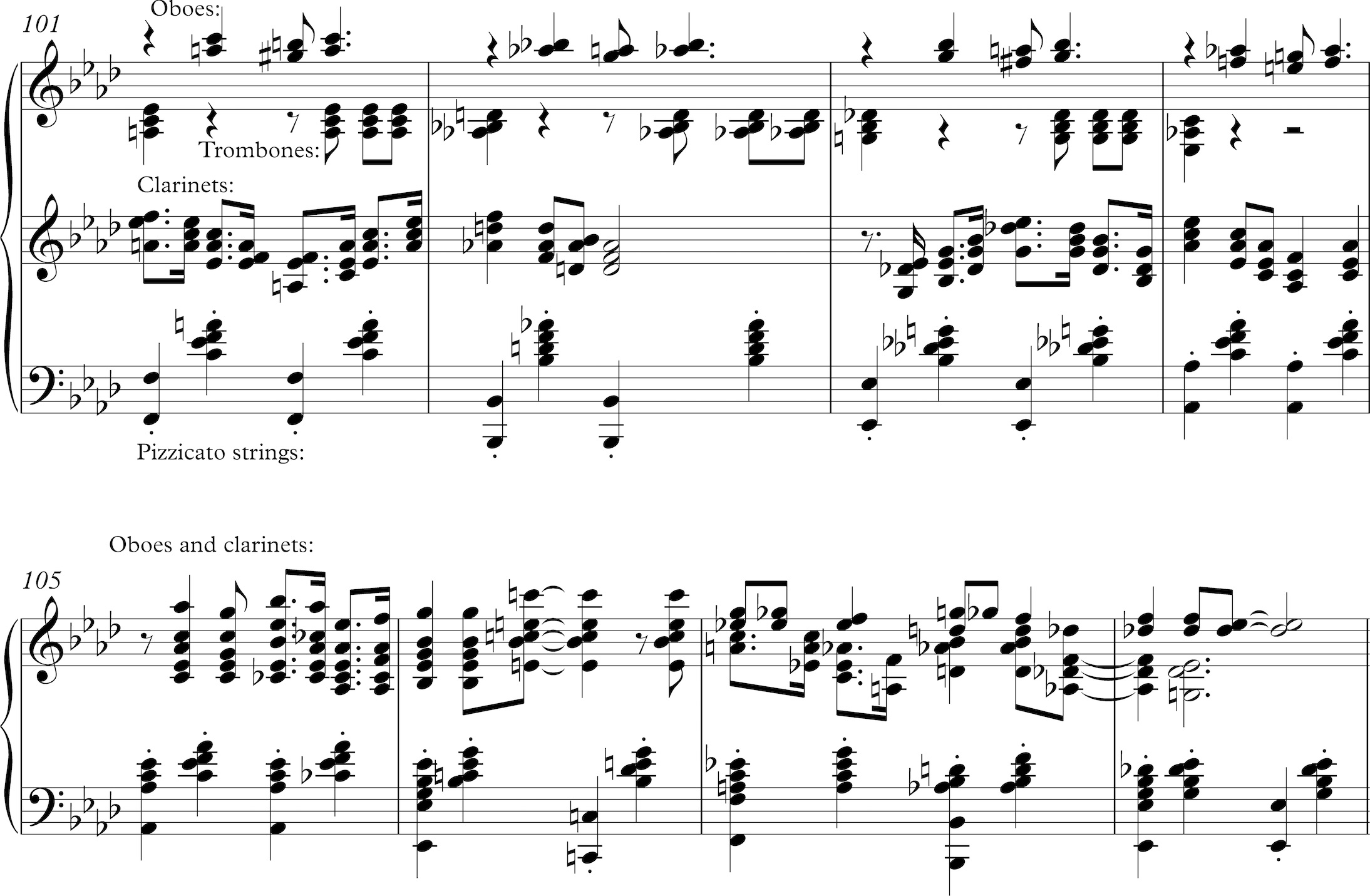

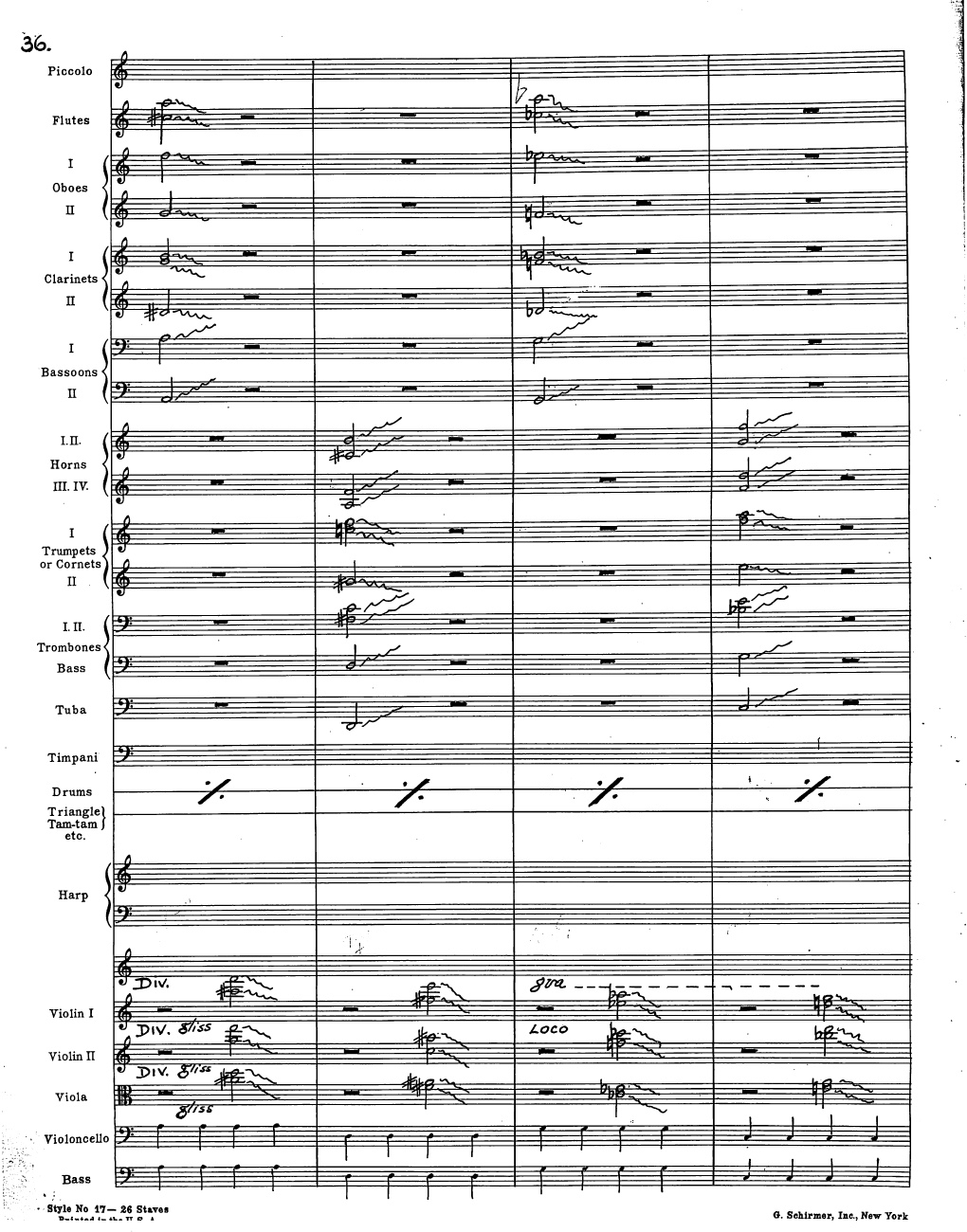

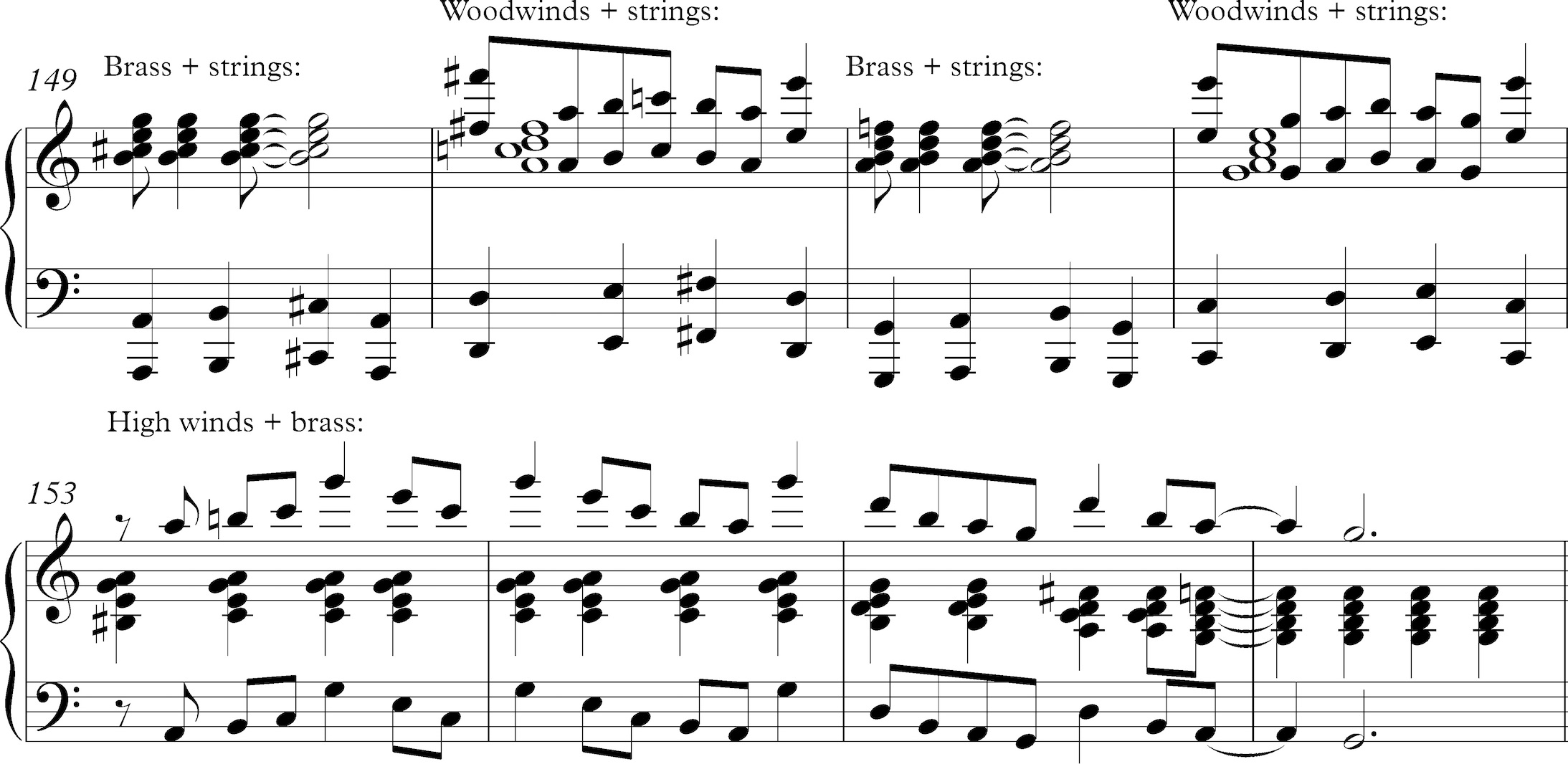

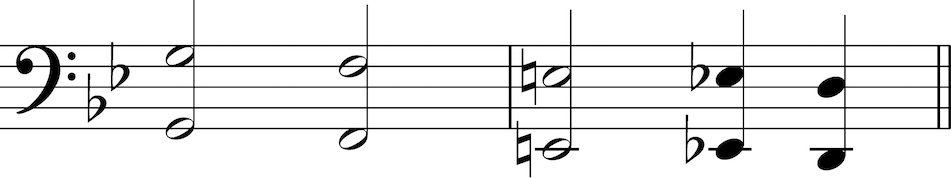

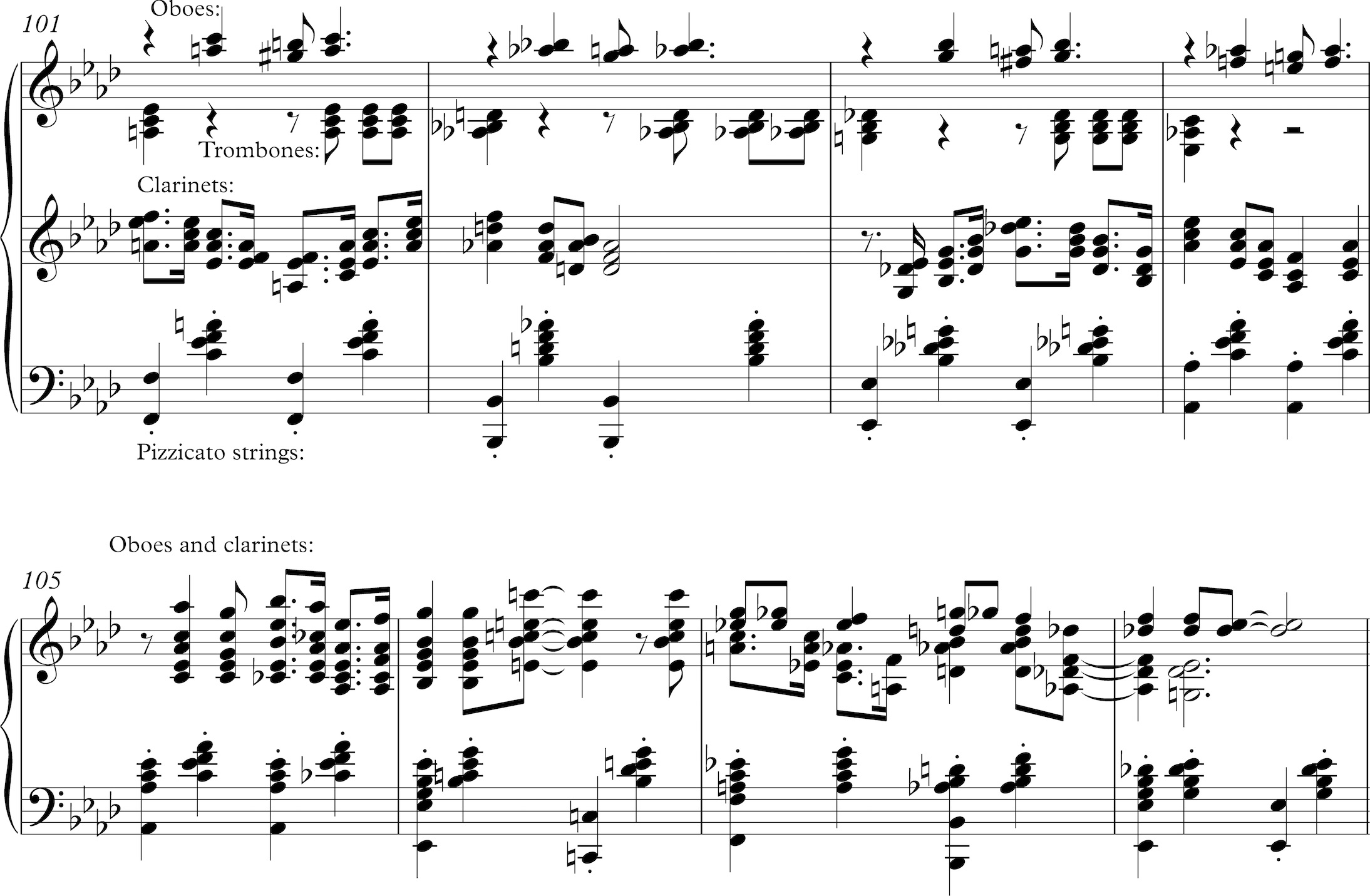

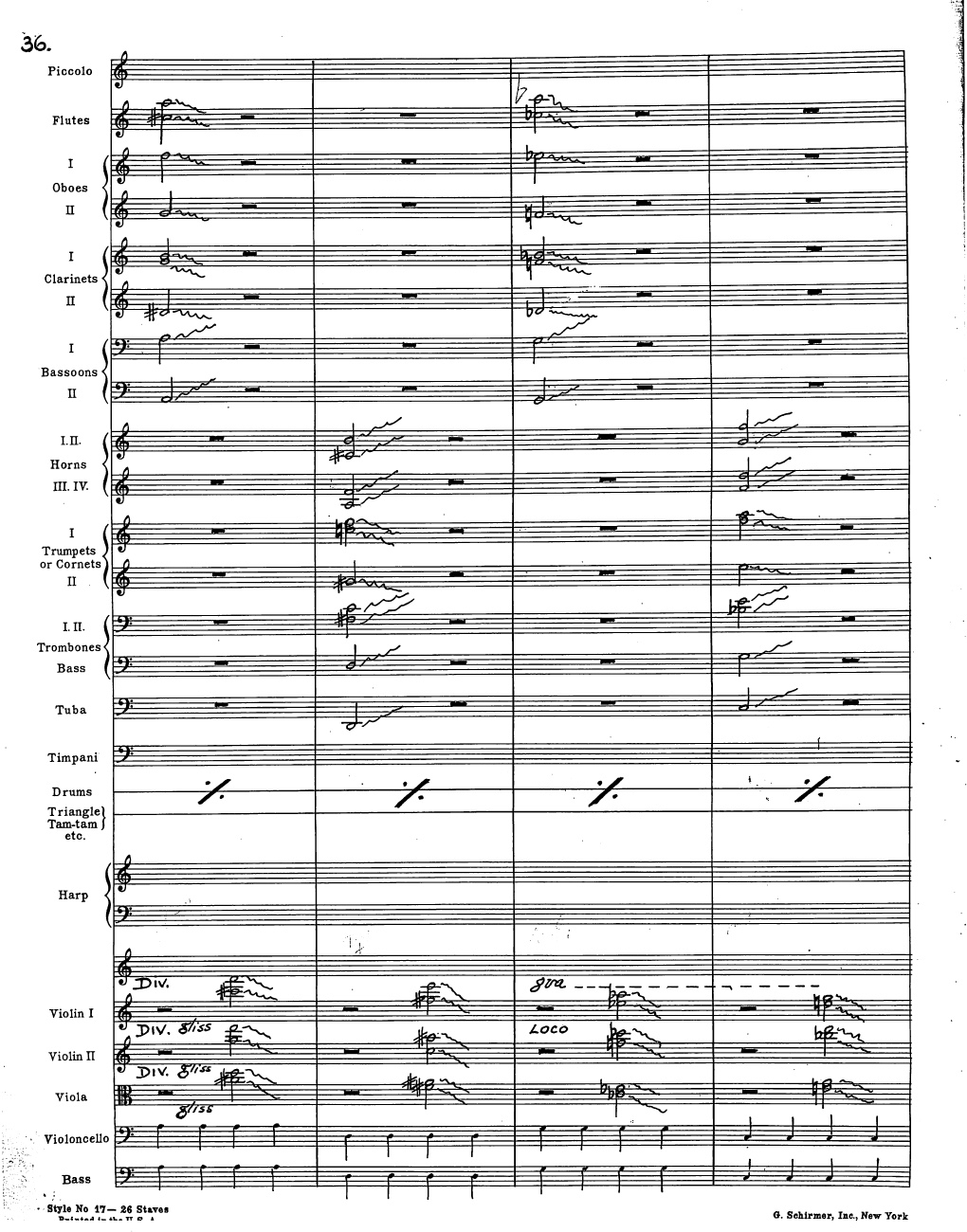

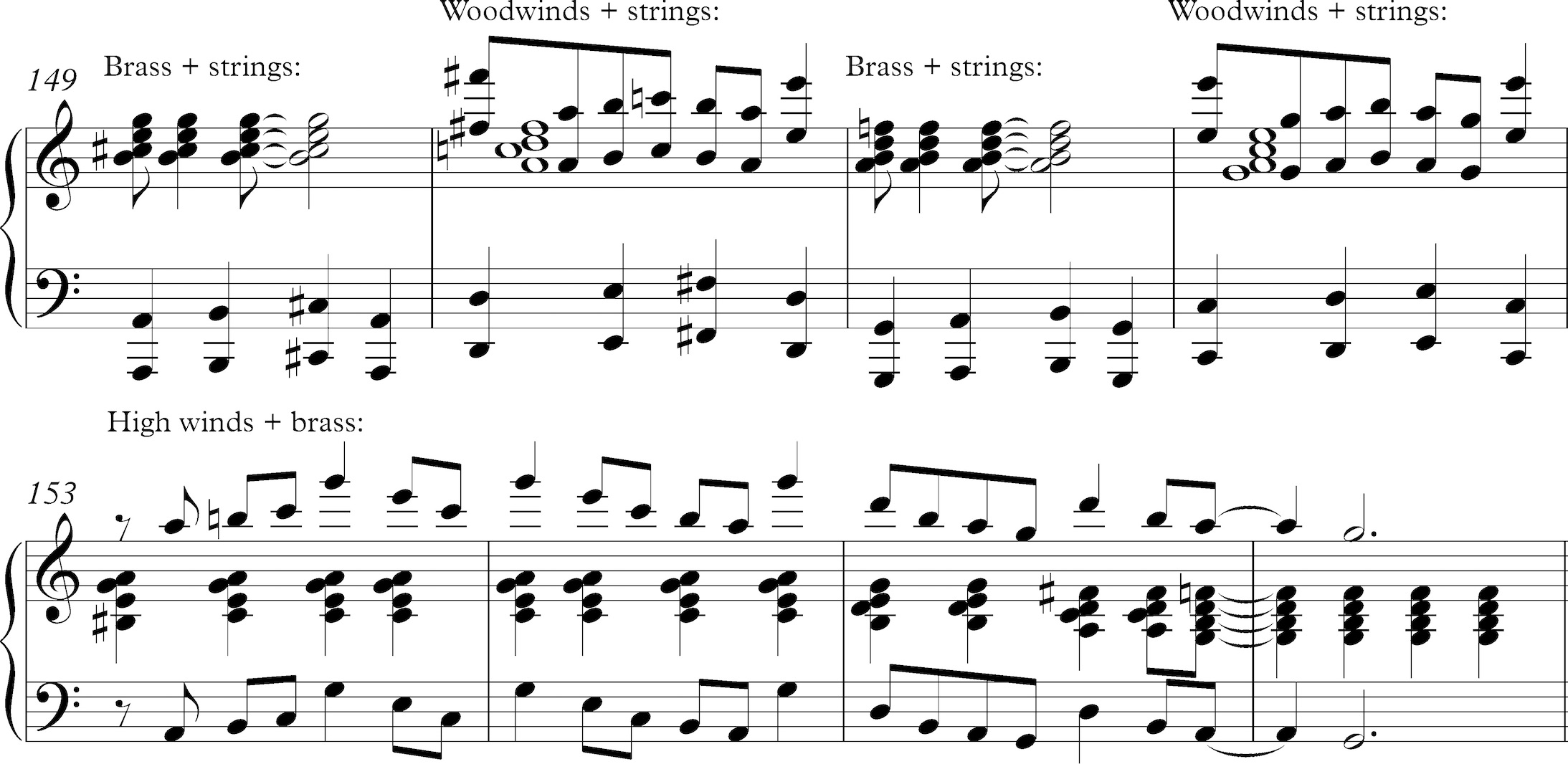

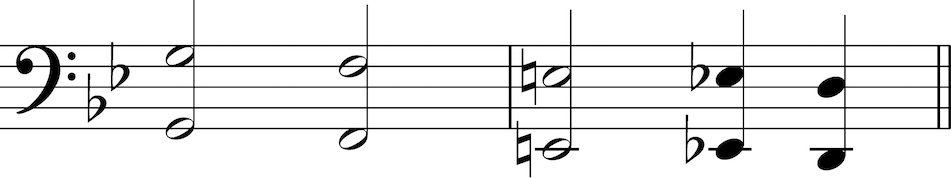

Keyboard reduction of the piece (PDF)

Recording

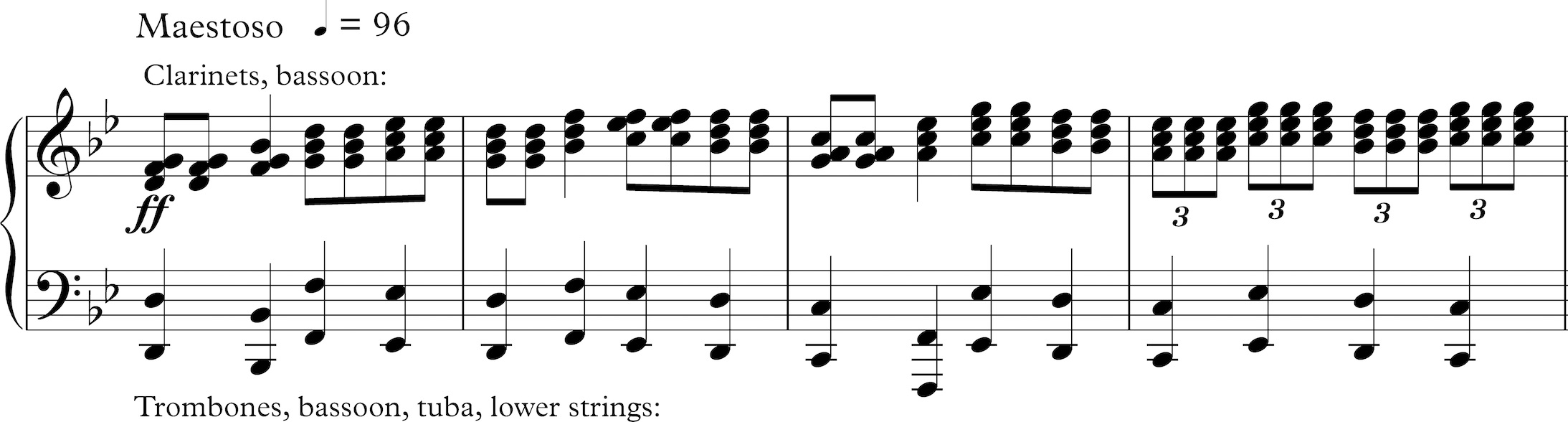

"Authenticity" is a word one bandies about at one's risk these days, since abundant doubt has been cast on who

is qualified to decide what is authentic in terms of whose music. Yet the Harlem Symphony of James P. Johnson

(1894-1955) has long fascinated me as a jazzman's contribution to the classical repertoire. Many, many composers,

both white (Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, Leonard Bernstein) and black (William Grant Still, Florence Price,

William Dawson) have written orchestral works which introduced jazz and blues idioms into European conventions.

But the Harlem Symphony stands out as a jazz and blues piece, by one of the outstanding stride pianists at the

peak of his career, that fits its materials into classical forms without much compromising their character.

Johnson was trained in classical music, of course, since in his youth classical music was virtually the only

kind in which tuition could be found. And he follows the classical formulas - but almost perfunctorily, simply

making the requisite key changes, never distorting the style he's most familiar with to put on classical airs.

The result is a piece that fills out a classical architecture, but sounds honest, fun, unpretentious - and not

divided in its allegiances.

My source for this analysis is the orchestral manuscript I found in the Jazz Institute Archive at Rutgers University. There are discrepancies between this score and the performance conducted by Marin Alsop on the Nimbus label, especially in the first movement. Arguably the score is improved by the changes made, but I don't know who is responsible for them.

Oddly, pages C and D (mm. 9-16) are omitted from the recording, and they do seem a little out of place.

They are labeled "Train," and are clearly meant to evoke the subway train beginning to take off, partly (mm. 13-14)

with a steady beat on a drum with wire brushes.

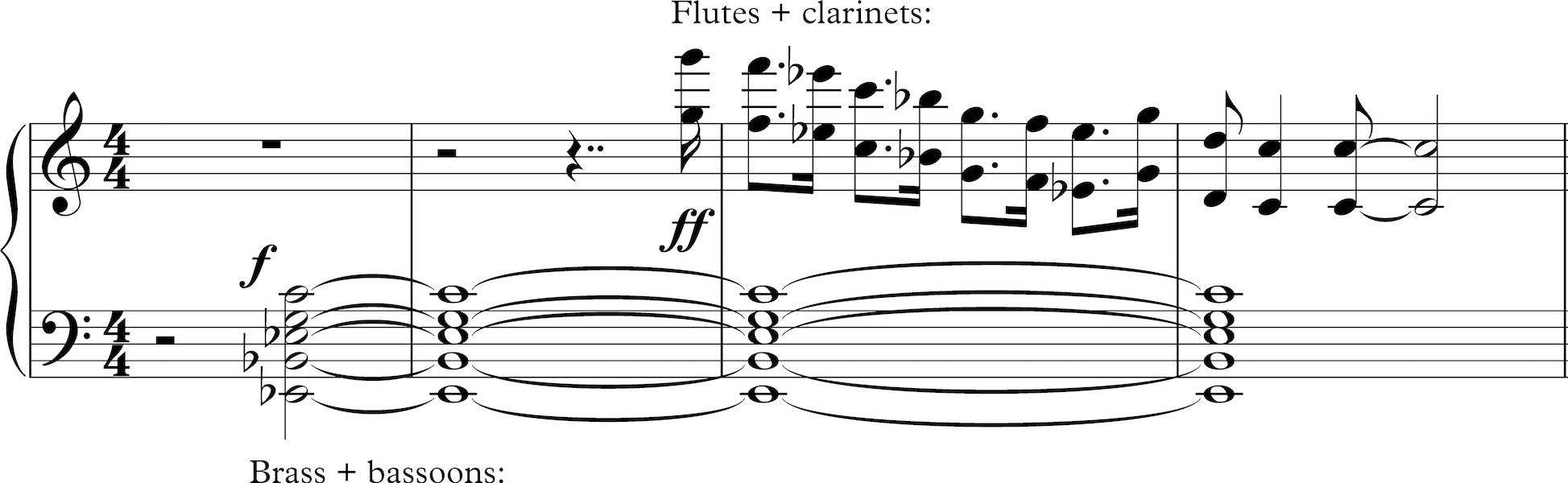

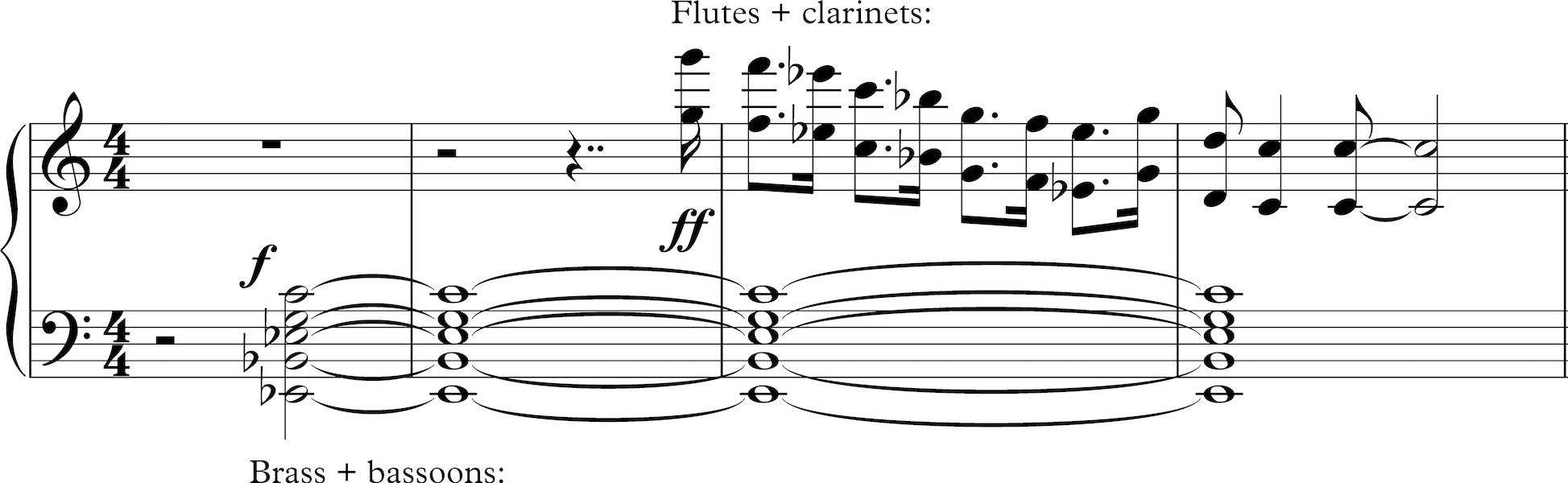

The first theme might be taken to be that played by just the strings in the following example, with their motive of thirds and fourths moving by half-steps - specifically, chromatic appoggiaturas moving to the chord tones of the harmony. However, the added wind notes above do contribute to the melody, and are difficult to separate out.

Remarkably, the first violins' melody employs ten of the twelve notes in the chromatic scale, despite the

economy of notes and the simplicity of the harmony. The B section part of this theme is a horn solo accompanied

by chords going around the circle of fifths, after which the first theme is repeated again, though this time

with the flutes echoing similar eighth-note gestures. Oddly, the recording repeats both A and B sections,

though the score does not call for it.

The transition from the first key area to the section is one of the briefest and most functional since the

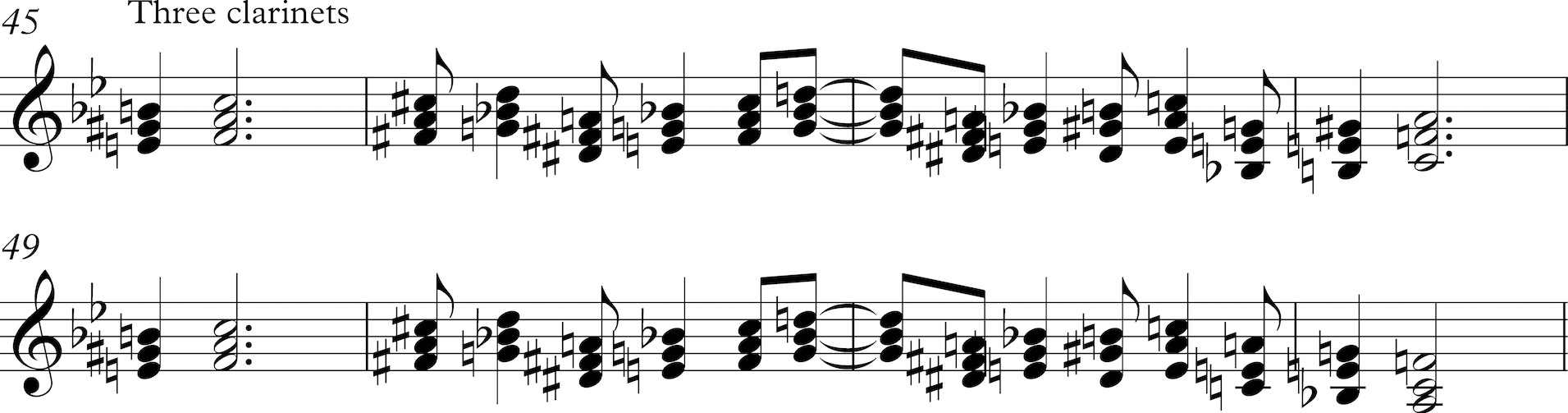

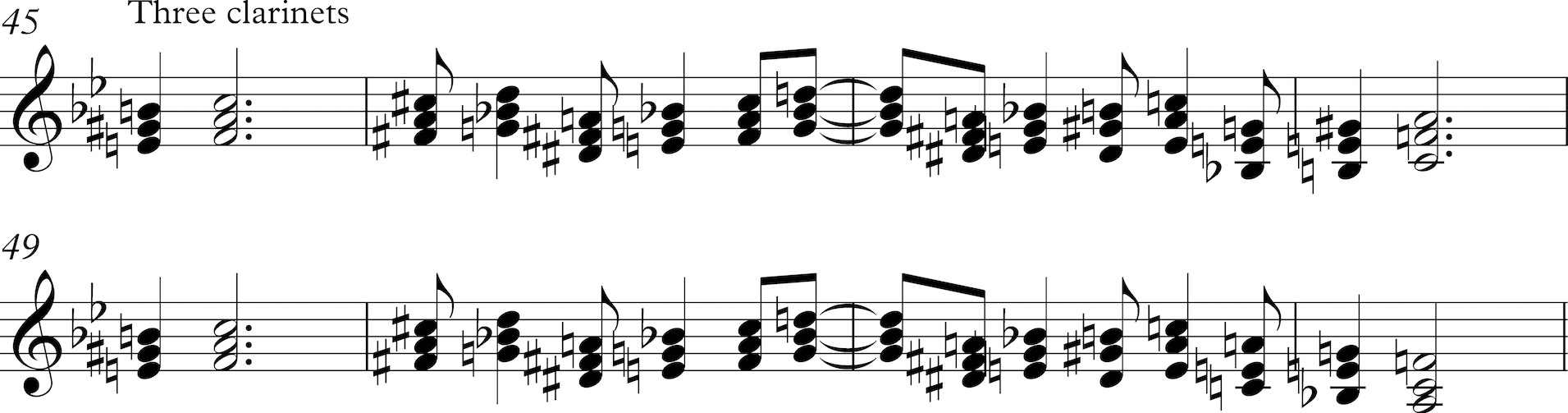

mid-eighteenth century. A clarinet plays two phrases (mm. 41-44), the first arpeggiating I-V-I in D, the second

V-V7-V/IV in C, and then we're in F major.

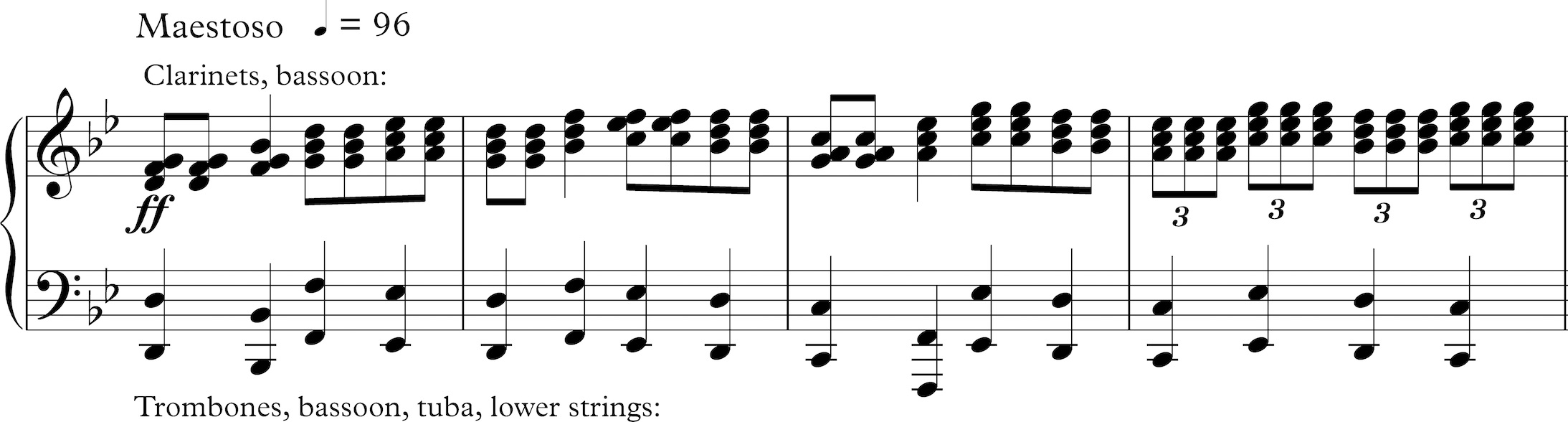

The derivation of the second theme from the first is impressively clever. Like the first theme, this one precedes almost every triad in the harmony with an appoggiatura chord a half-step lower, but the rhythm is sped up and irresistibly syncopated. The first theme's initial motive is an eighth-note moving to the tonic: here it becomes a quarter-note moving to the dominant scale degree. Also, the scoring for a chorus of clarinets is taken from jazz orchestration - one can hardly imagine a classical composer announcing a new theme in parallel chords by three of the same instrument.

Like the main theme, this subordinate one also has a middle verse after which it returns:

And I particularly admire that in the repeat of the second theme, Johnson changes one note to approach

the cadence from a different half-step.

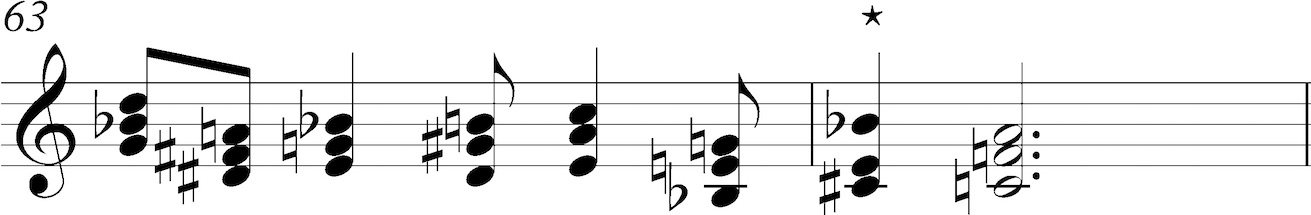

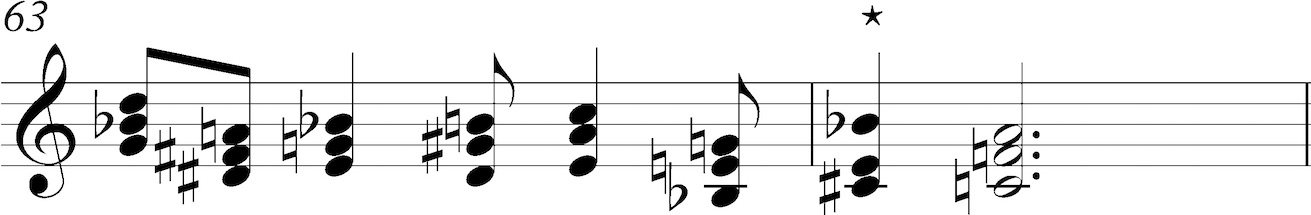

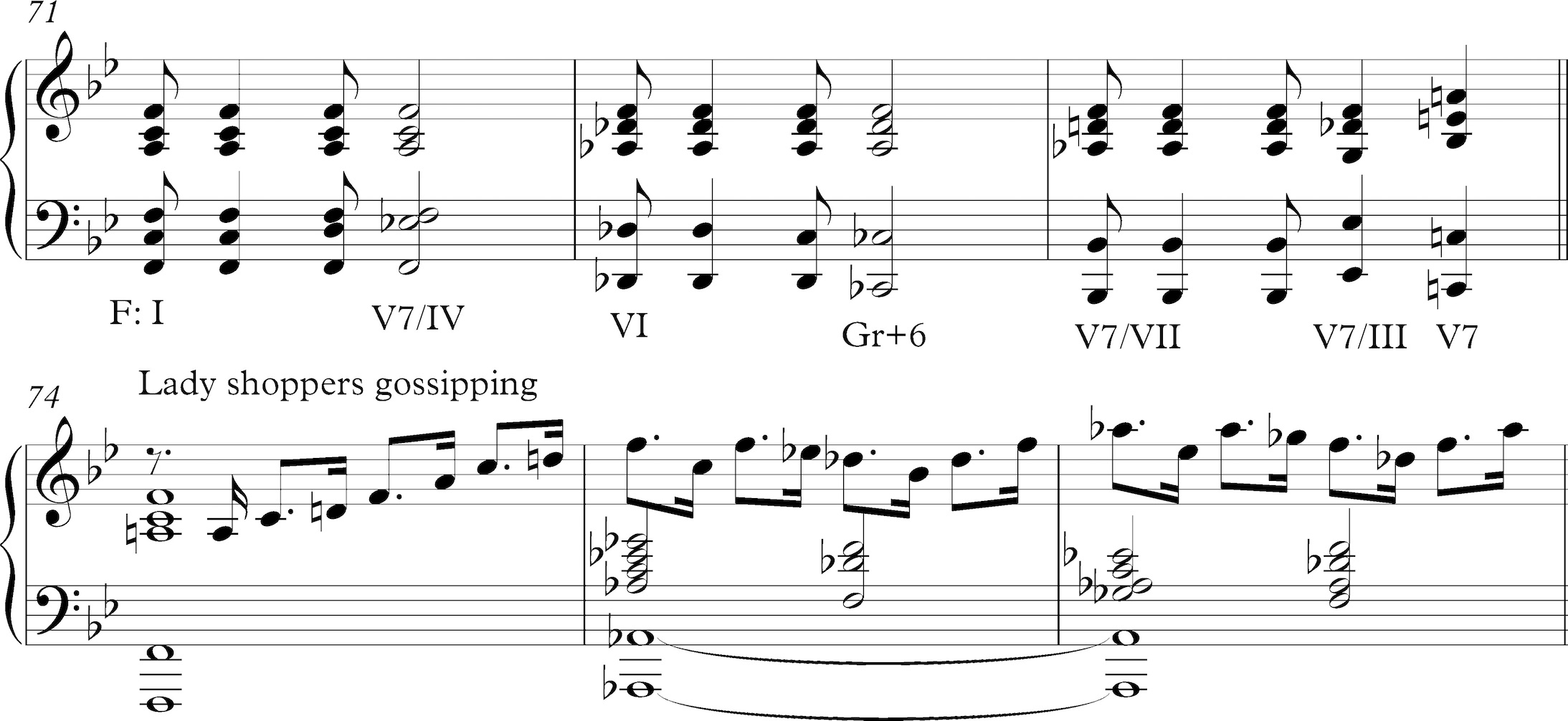

The repeat of the theme is immediately followed by a colorful chord progression bringing the exposition

to a close in F. Clarinets and strings in dotted rhythms open the development with an immediate move to Db,

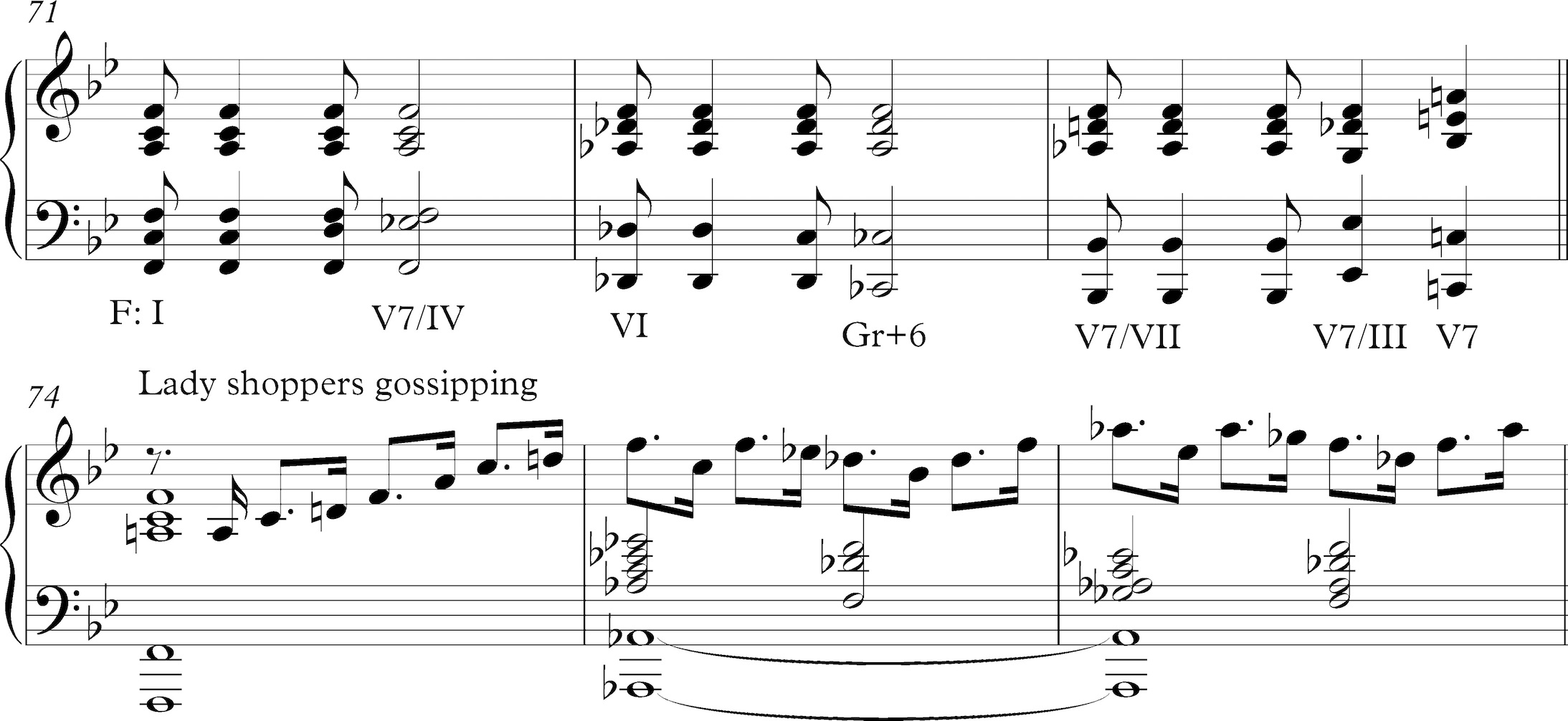

the rhythm intended to convey a pictorial effect that Johnson labels "Lady Shoppers - gossiping."

One imagines the humor was better appreciated in 1932.

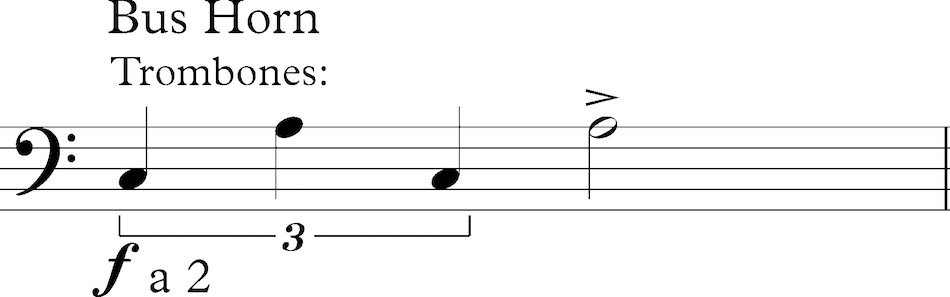

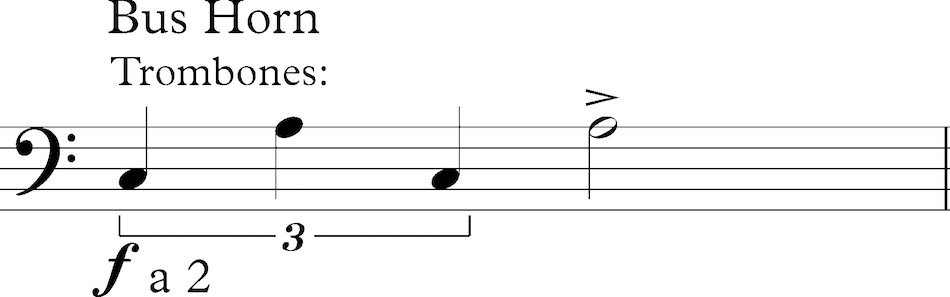

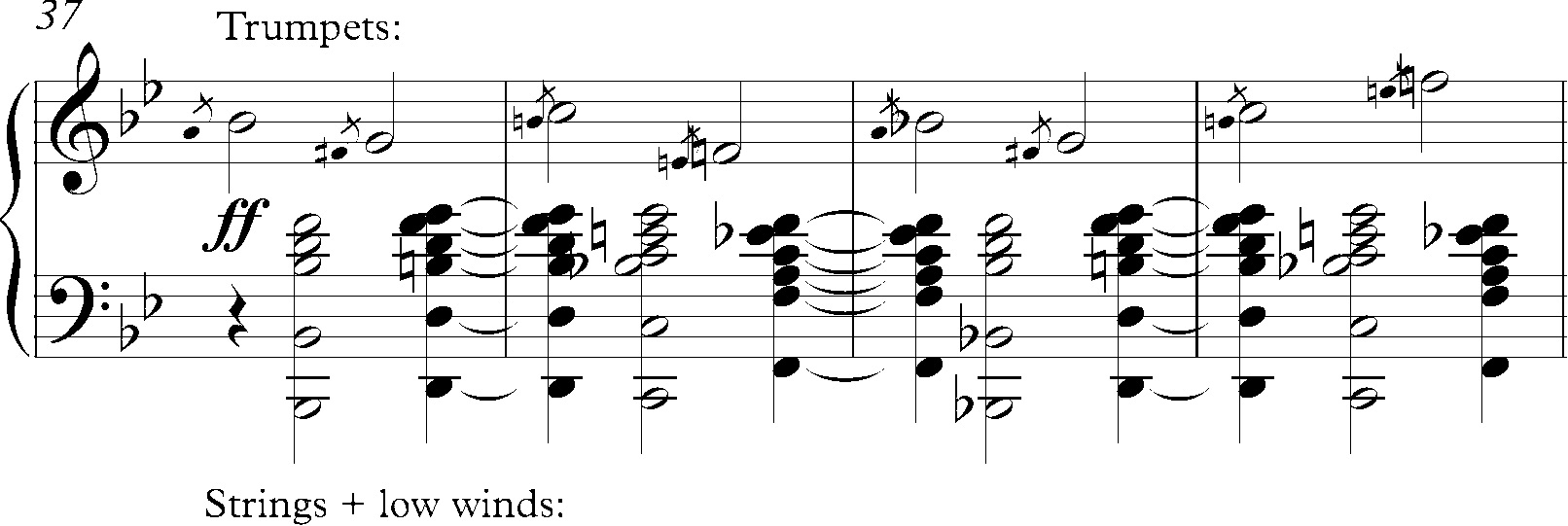

In mm. 75-85 a rhythmicized chord progression thick with tritones descending by half-step leads to a dominant pedal on A. The subordinate theme enters in the key of D now (mm. 86-93), poco piu mosso and with a countermelody soaring high above in the piccolo. Its final D chord becomes a dominant, and forthwith the first theme is stated in G (mm. 94-101), by the trumpets and trombones using cup mutes and the latter echoing the former. To end the development, the brass syncopate their way through a simple chord progression (Bb7-Eb, B7-E, C7-F, F7, mm. 102-111), pausing at the end for a wry figure in the trombones clearly labeled "Bus Horn."

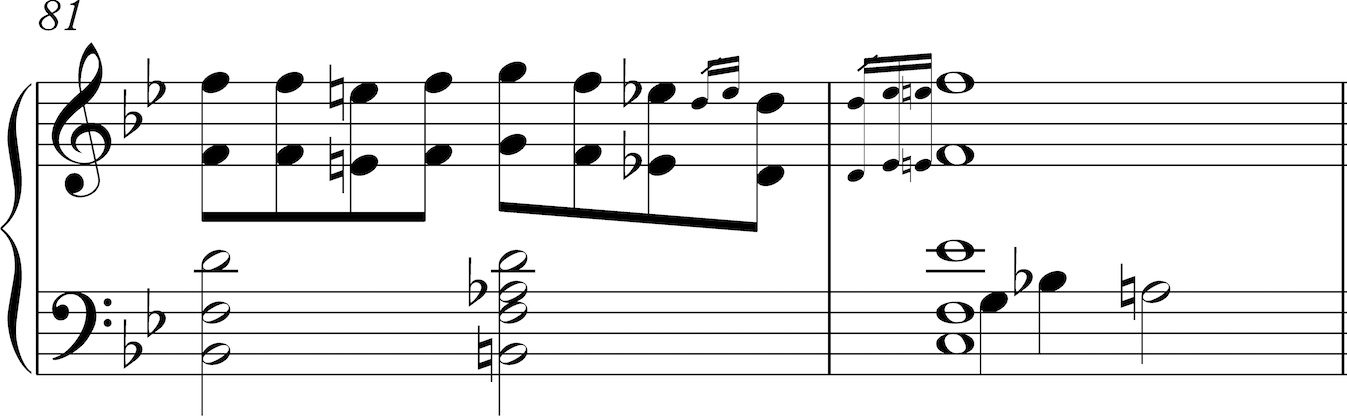

The opening of the recapitulation is labeled "7th Ave Promenade." The first theme is played in Bb by the

tutti orchestra (mm. 112-119). A tumultuous transition of syncopated dominant chords descending by half-steps,

and marked Presto, acts as transition to the subordinate theme, now played in Bb and also tutti, the tempo

marked "a tempo" and "slower" (mm. 130-140). A staccato piccolo line rings out above the orchestra. (Neither

theme includes its middle section nor is repeated in the recap.) An expectant series of augmented triads then

rises by half-step, and the opening introductory theme returns "grandioso" in the trombones to close the movement.

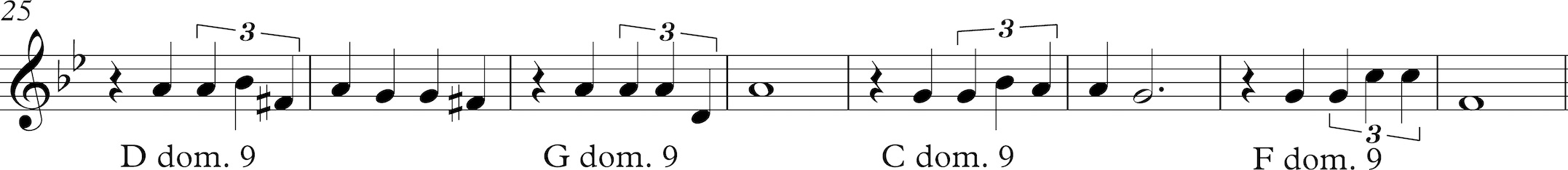

Second movement: Song of Harlem (April in Harlem)

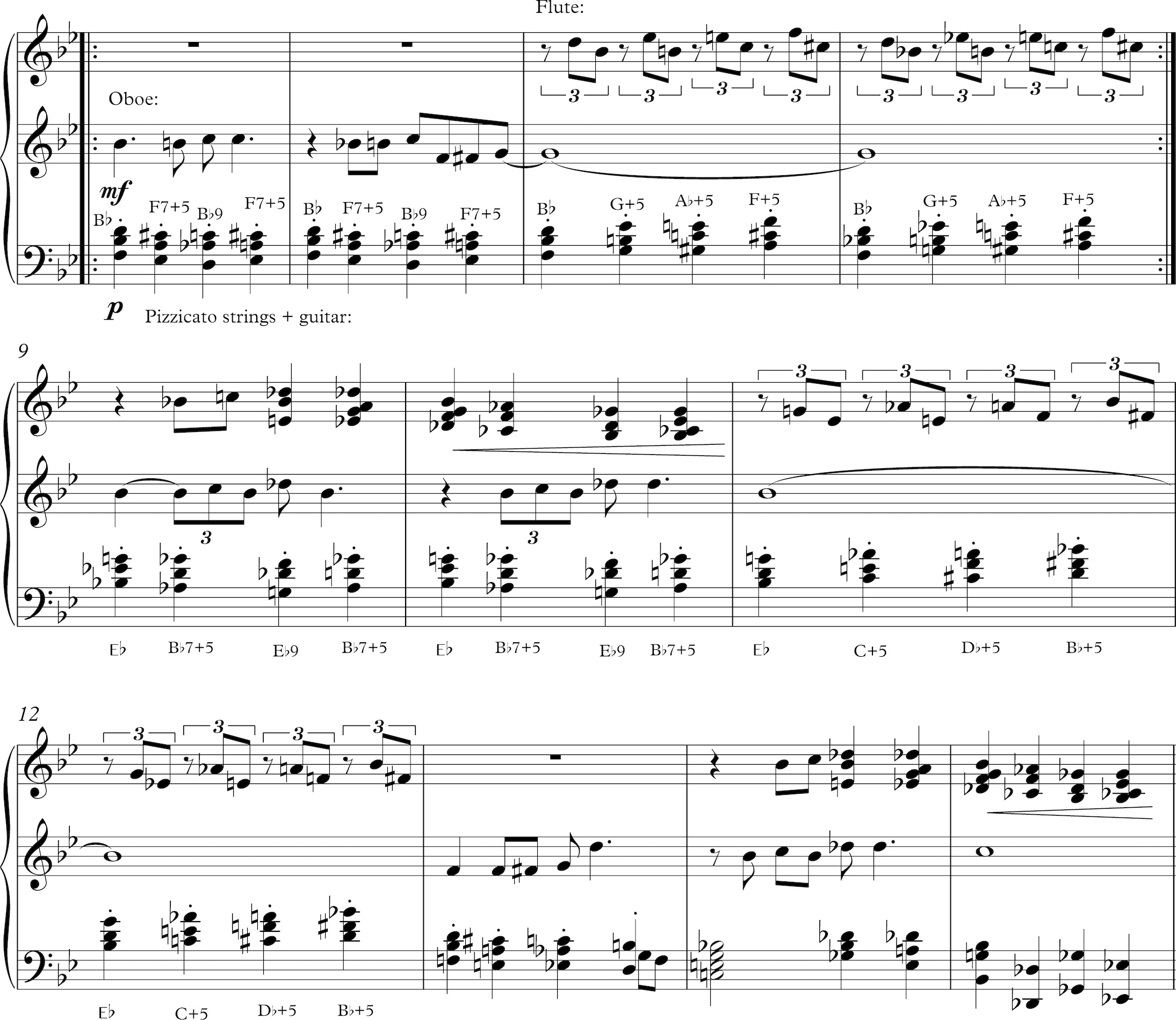

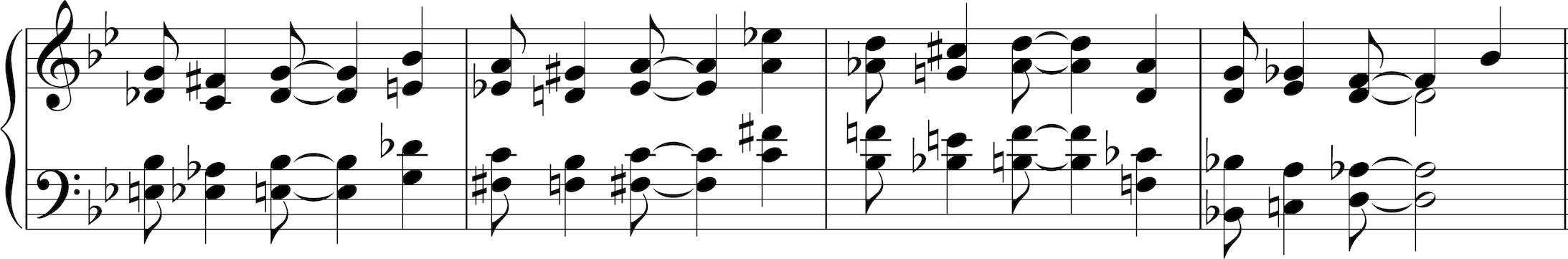

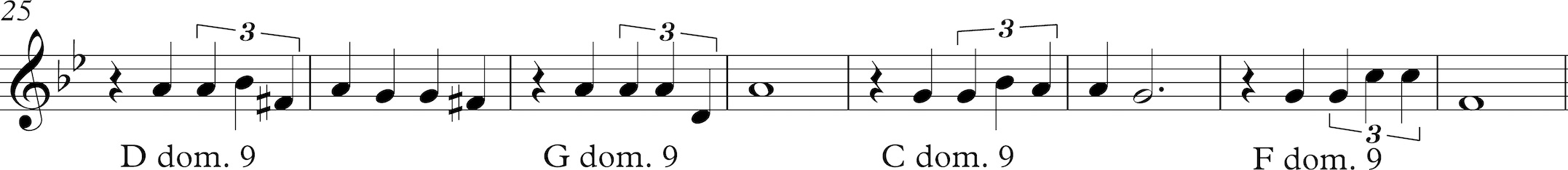

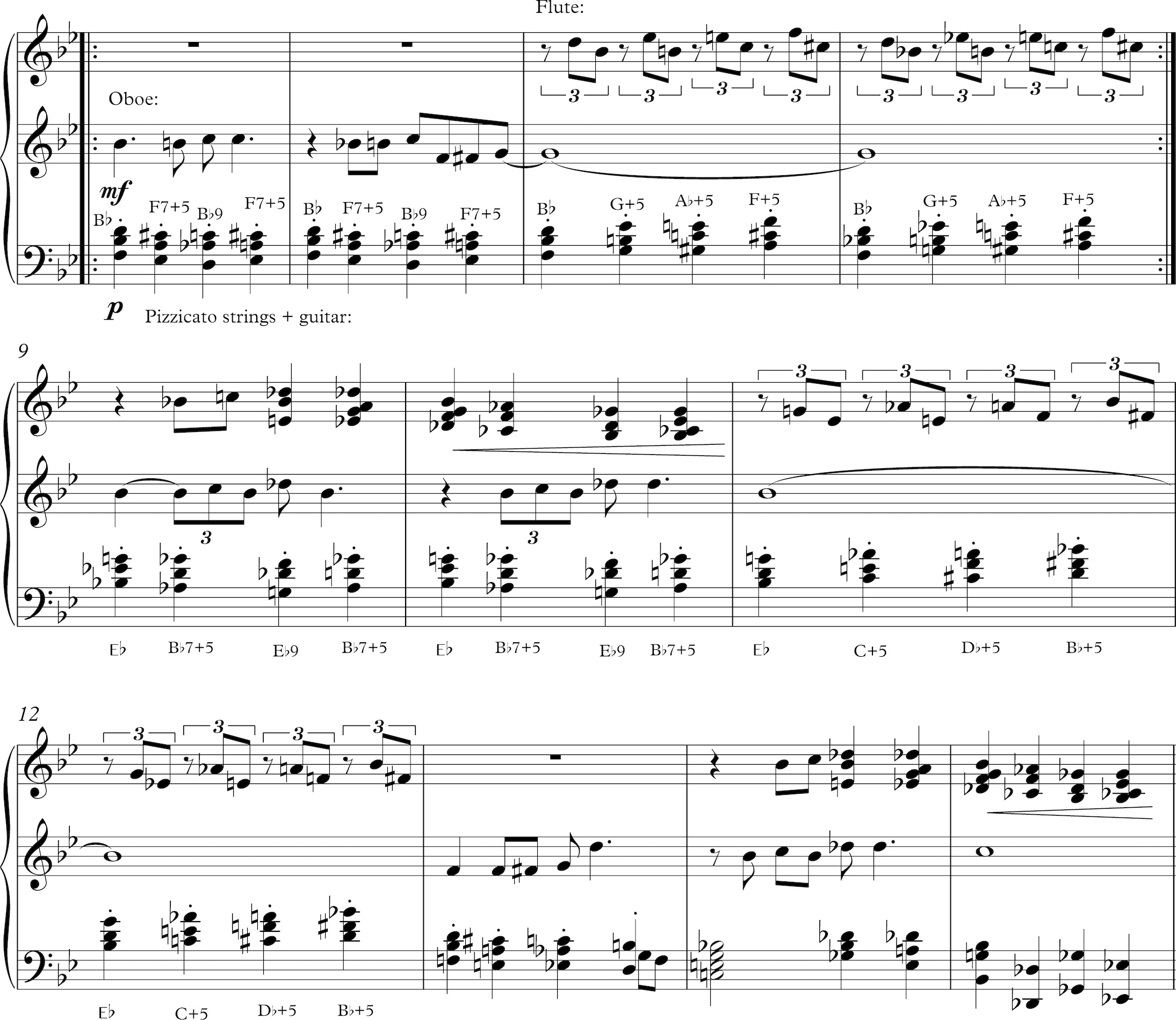

There are two themes, between which the transitions comprise mostly short, sequential motives over standard modulatory progressions. The first theme is stated in the oboe at the outset, and returns in the strings at m. 60, both times in Bb. I give here not only the melody, in the middle staff (and the repeat of the first four measures is written out, sans repeat signs), but also the pizzicato string chords that accompany the first statement, plus Johnson's chord symbols for the guitar part, which is not specifically notated (except for occasional melodic notes). One can see, then, along with the major and minor triads which tend to anchor the downbeats, Johnson's use of whole-tone type chords, either augmented triads or tritone-plus-major third. The chord symbols suggest more notes in the guitar than are present in the strings - for instance, F7+5 for Eb-A-C#, and Bb9 for D-Ab-C. On the top staff are given the parallel major thirds in the flute which fill in each cadence.

The appearance of the blues third Db in m. 10 creates an expectation, I think, that the melody will be a

twelve-bar blues, but Johnson adds a fourth phrase that repeats the blues third and ends a little more

ambiguously. The following transition is eight bars long, but Johnson elides the last measure of the

sixteen-bard theme with the first measure of the transition for an odd-number count: a rather Mozartean

touch.

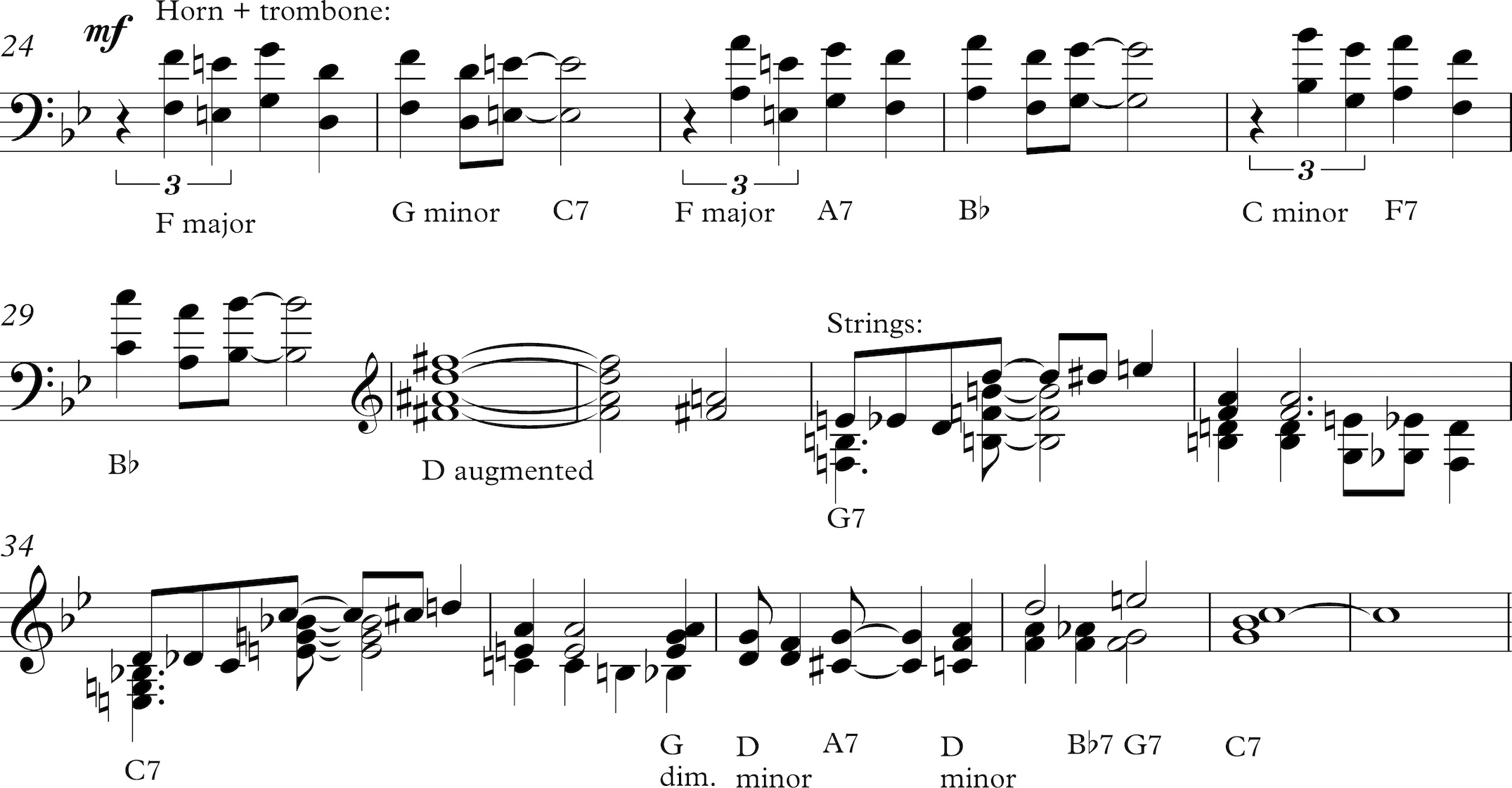

The second theme is labeled in the score "Harlem Love Song." It is an expansive thirty-two bars in length, alternating between winds and strings every eight bars. The style is grand Swing Era ballroom at its most cinematic, pausing on climaxes at sharped-fifth dominants and full of lush dominant major ninths. I provide here the guitar symbols notated by Johnson, but they don't account for the lushness of certain chords.

A perfunctory four-measure modulation returns us to the first theme, which, now in the strings, is a little

more emphatically accompanied by much the same elements. The following transition starts out similar in rhythm

to the analogous transition in the exposition, but two measures of chords stretch this passage out to nine

measures (another odd-numbered macro-rhythm, and I can't imagine Johnson wasn't conscious of his balanced

asymmetries). The last four measures of the transition seem poised to introduce a new tune, but instead merely

return to the Harlem Love Song, now in the Bb tonic and more lushly orchestrated.

A four-measure coda threatens to end quietly at first, but ascends to a lush, Swing Era cadence with a

sharped-fifth dominant and a trill figure dropping to the added sixth. One can imagine so many 1940s movies

coming to a dramatic close with this phrase.

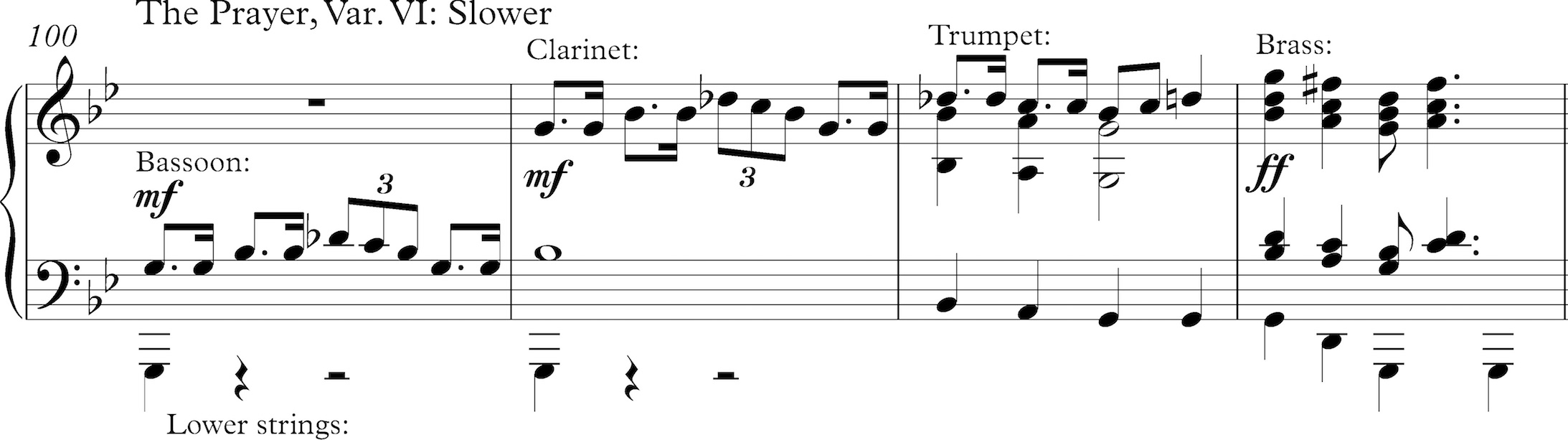

Third movement: The Night Club

The movement starts with a hesitant, atmosphere-setting twelve-bar introduction, moving from Eb major with

an added sixth to a Db dominant major ninth and back.

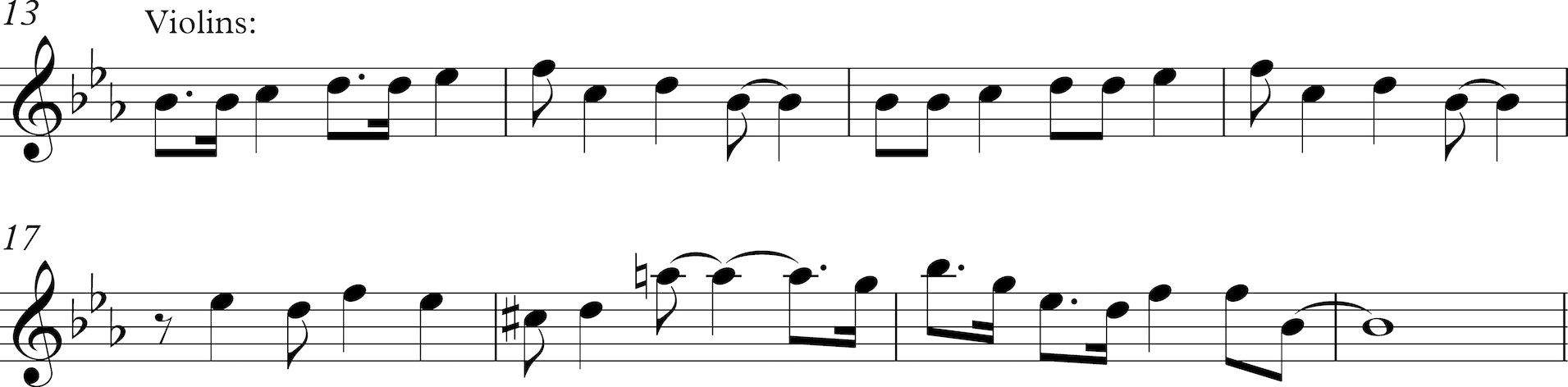

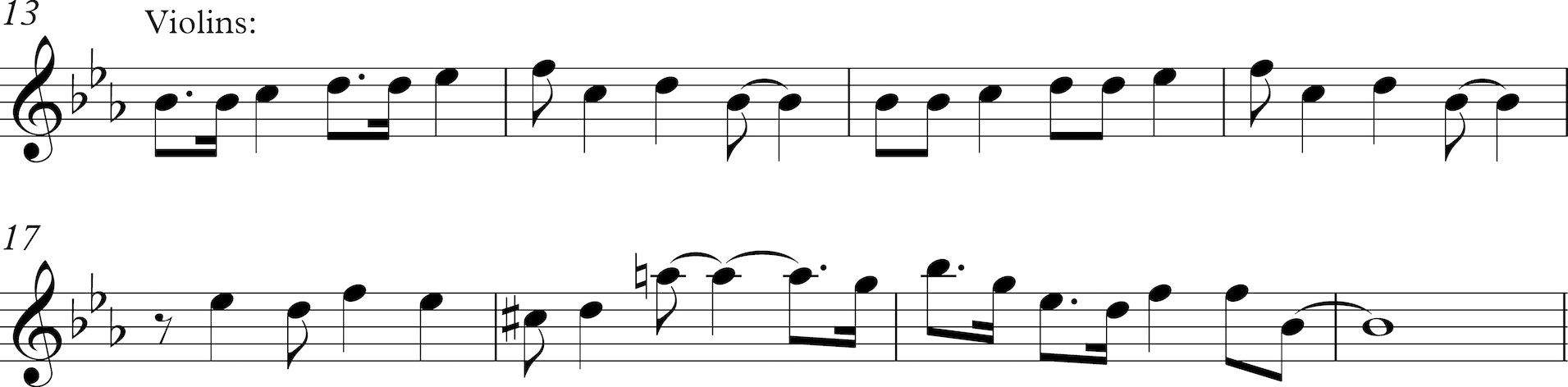

The first theme, in the violins, is sixteen bars, the last of which is diverted to a V7 of Bb, and the tune

is restated in Bb in the trumpet, and it is clear that the eighth-notes must be swung. Comparison of the two

consecutive versions how much freedom Johnson treats his melody with - as, in jazz, why would the trumpet play

it the same way the strings do?

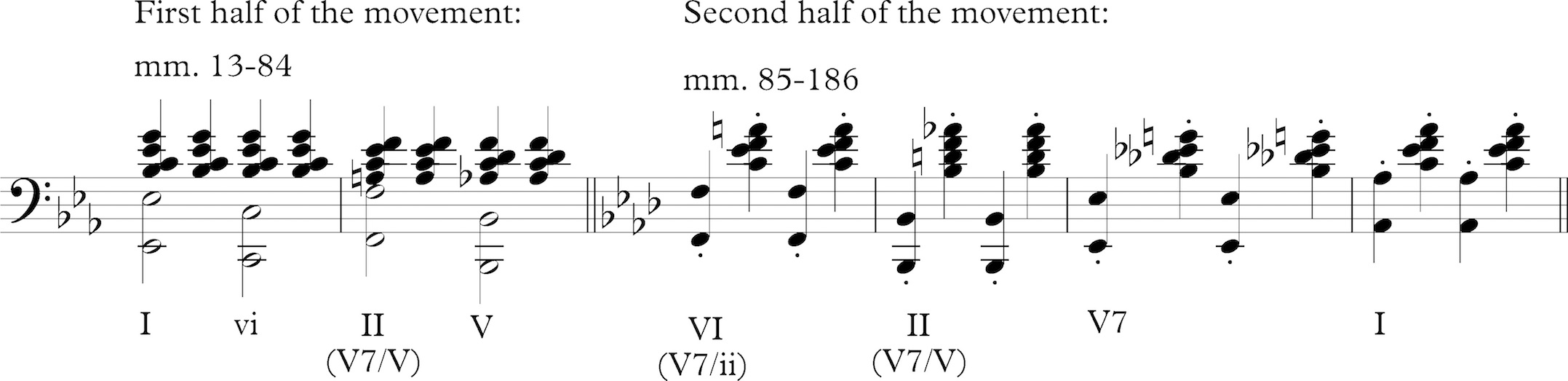

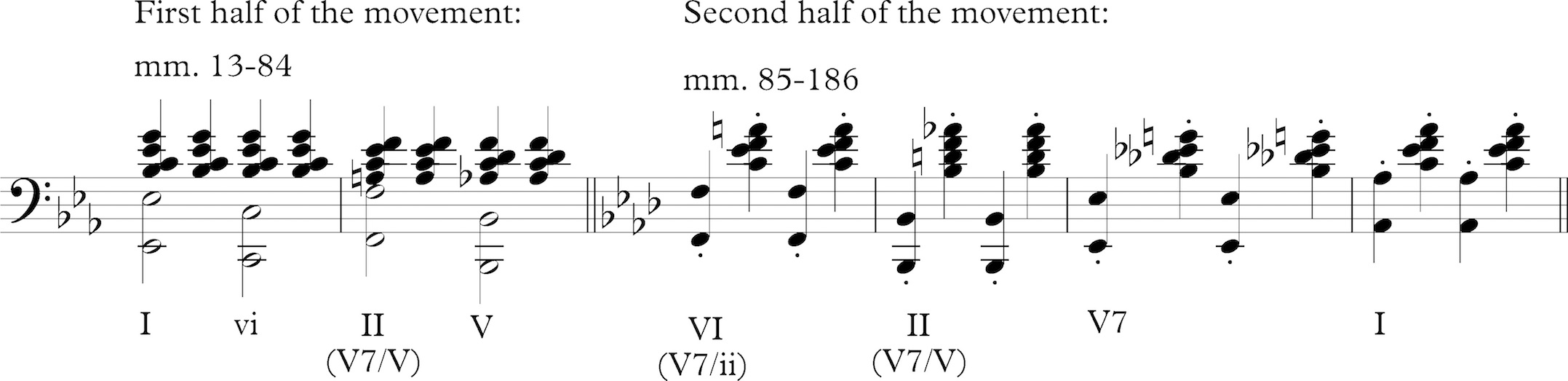

In fact, the trumpets replace the third phrase with a comedic reference to the I-VI-II-V that runs through

the harmony.

The sixteen-bar transition that begins at m. 45 begins each half with a faux-dramatic passage of diminished

seventh chords and dominants before relaxing each time into the dotted note texture prevalent earlier.

This leads to another statement of the first theme similar to the first, but in the upper winds. The bridge

to the trio is an eight-measure pedal on Eb using jazzy syncopated chords to prepare for the Ab-major of the trio.

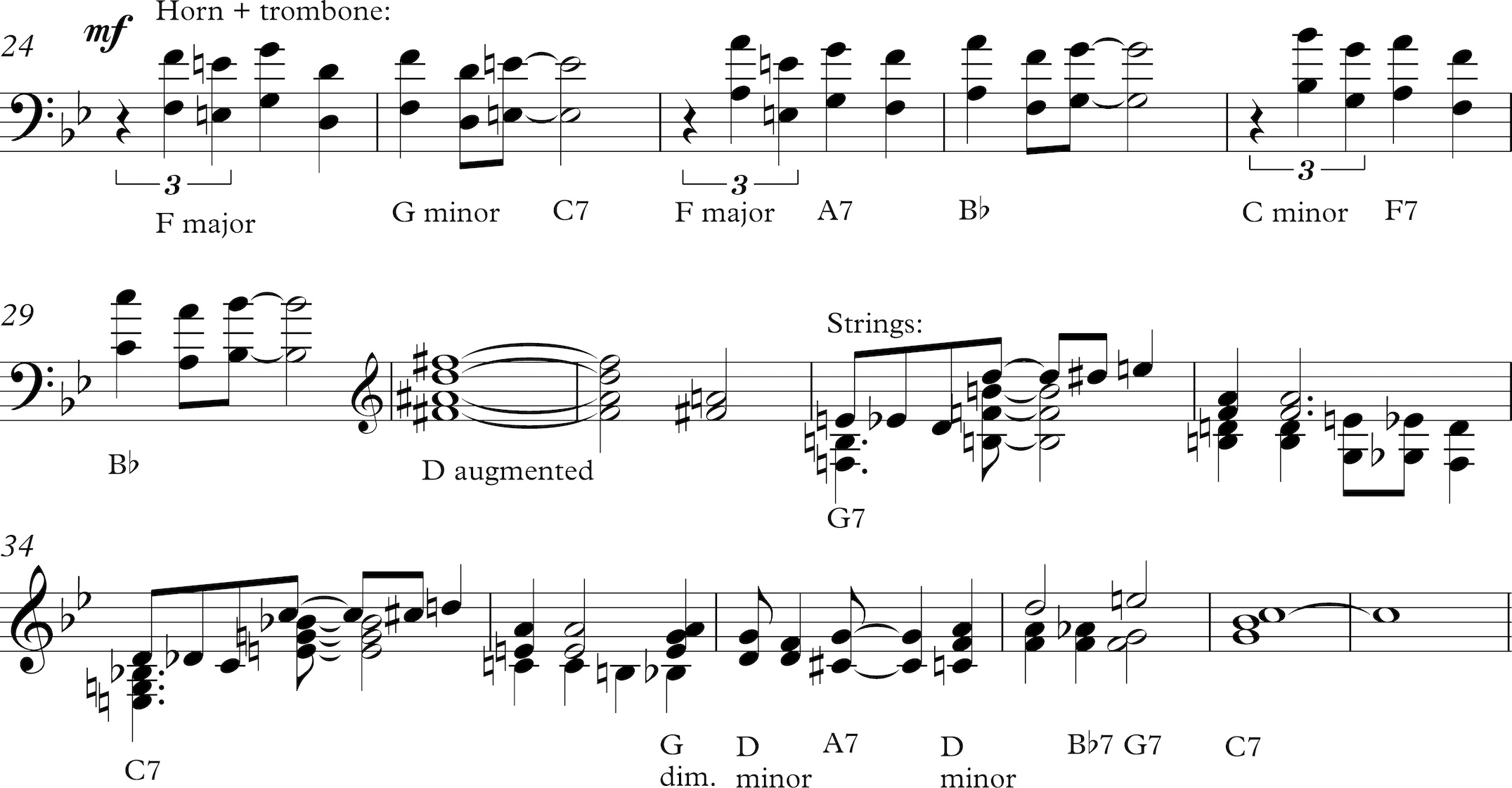

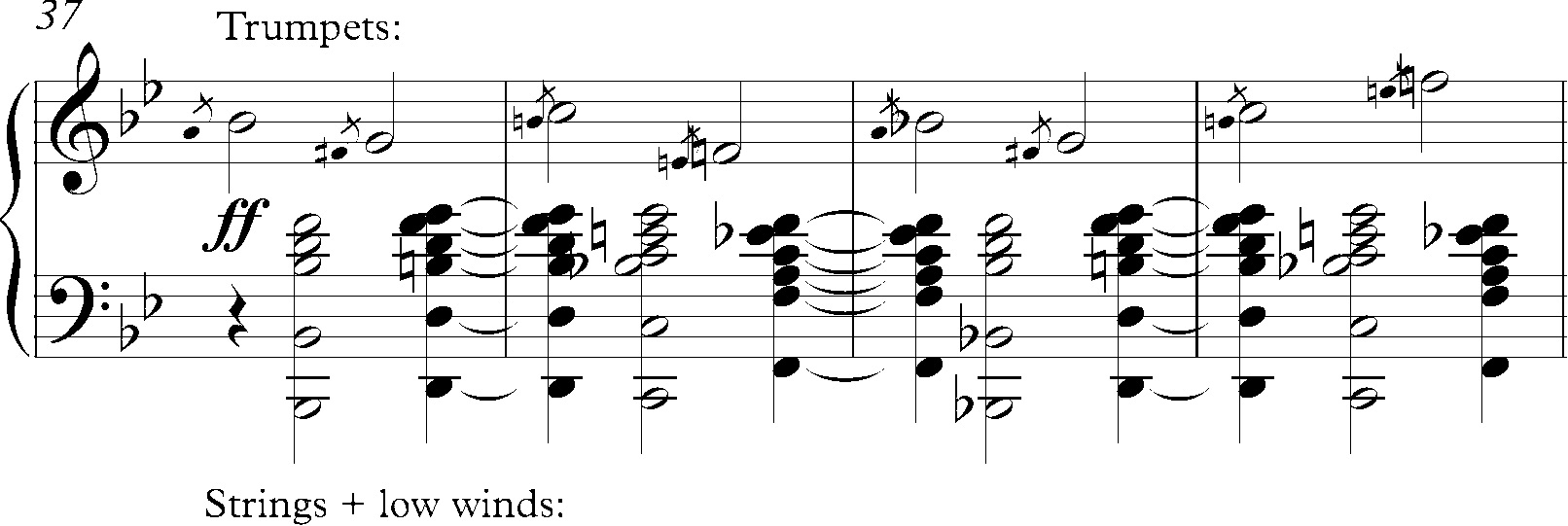

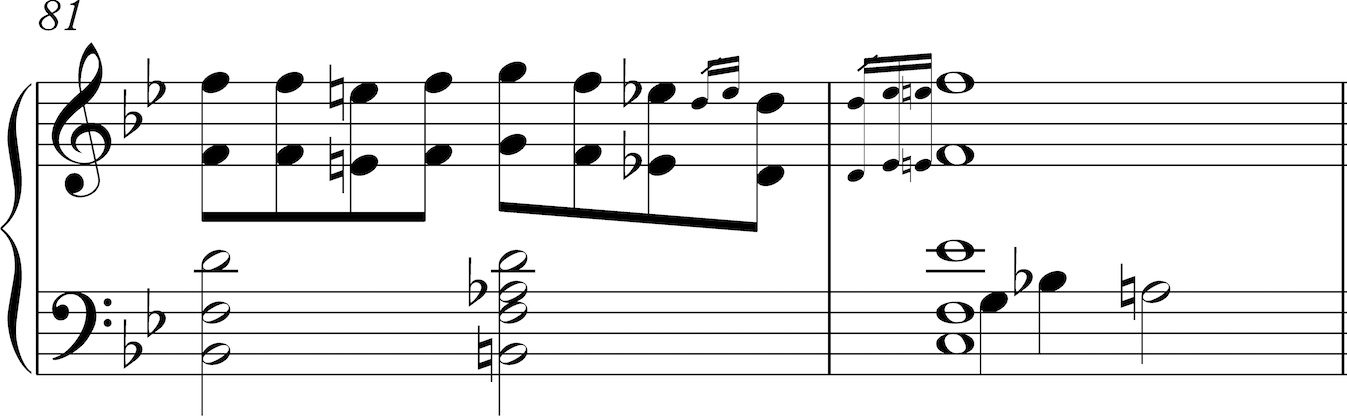

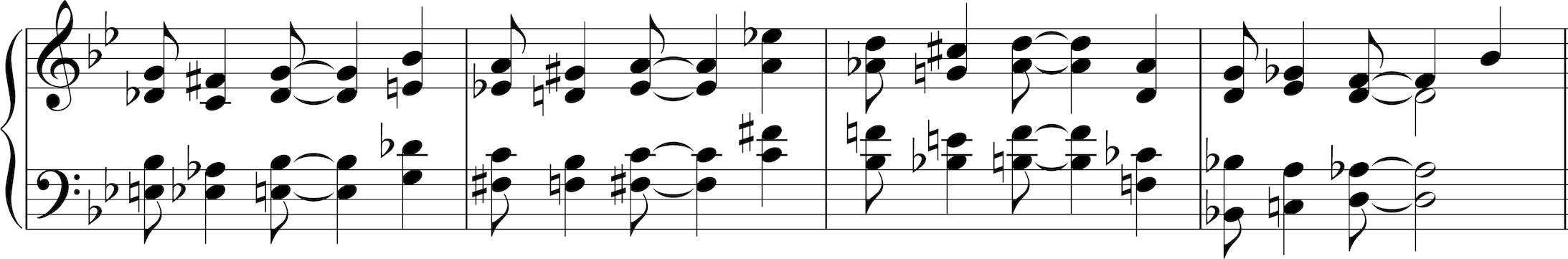

In mm. 85-132 the trio theme is repeated three times in varying orchestrations. Unlike the first theme, it begins more anxiously on the IV chord (V7/ii, actually) rather than on the tonic. This example from the second statement shows how thick Johnson's orchestration becomes, with the theme here once again in the trio of clarinets. Even more striking are the stride piano patterns in the strings, showing that at this point Johnson was simply orchestrating the piano style he spent his life playing.

The third appearance of the trio theme turns to V7 of C just at the end, and over a VI-II-V-I in the low

strings comes the most bracing section of the work: a back and forth of glissandos between the winds and strings,

sometimes in both directions at once. No transcription could give the passage its due as well as the manuscript can.

The glissando section leads into a pair of sixteen-bar melodies on the by-now-familiar harmonic pattern,

the first riotously orchestrated in a call-and-answer pattern.

The second is similar, but in tutti chords, and interrupted at the end, in time-honored Swing Era fashion,

by a couple of piccolo cadenzas, before a dramatic final cadence with an augmented dominant.

Fourth Movement: Baptist Mission

The theme is introduced at a languid largo tempo, with some of the lushest chromatic harmonization of the entire work.

From here on the tempo quickens considerably for most of the rest of the movement, introducing a bass

ostinato that will run through the first five variations.

Variation I (mm. 16-35) simply states the hymn in a solo horn with a simplified string accompaniment.

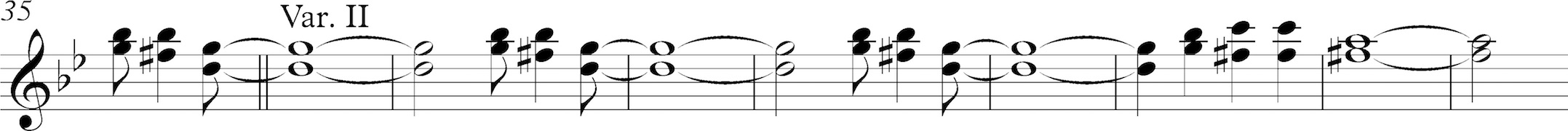

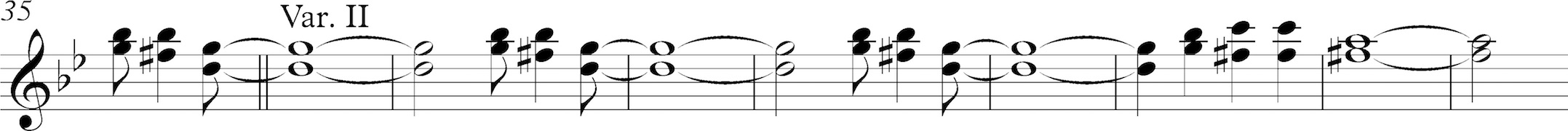

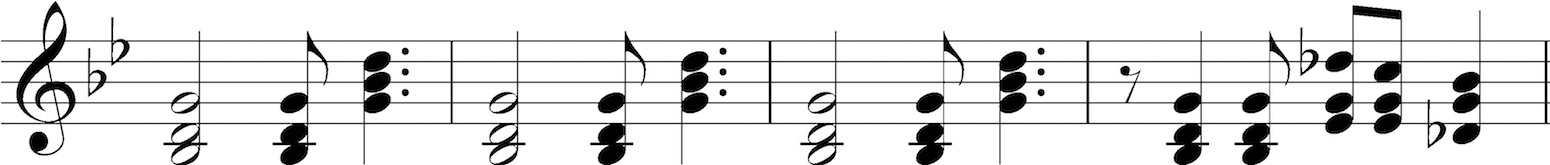

Variation II (mm. 36-51) puts the theme back in the strings, enlivened by periodic figures in the oboes.

Variation III (mm. 52-67) has the theme in the trumpet, while a clarinet plays a countermelody with a jazzy

flat fifth (Db). The ostinato is taken over, with similarly bluesy harmonies, by the entire string section.

Variation IV (mm. 68-83) returns the theme to the strings a bassoon and trombone, with rippling arpeggios in chords in the flutes and clarinets.

Variation V (mm. 84-99), upping the energy level, has the theme in the oboes, accompanied by the strings and lower brass in jazz chords. The three trumpets punctuate it with syncopated figures.

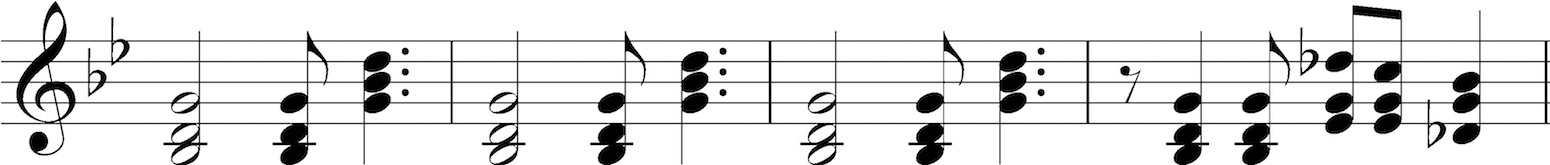

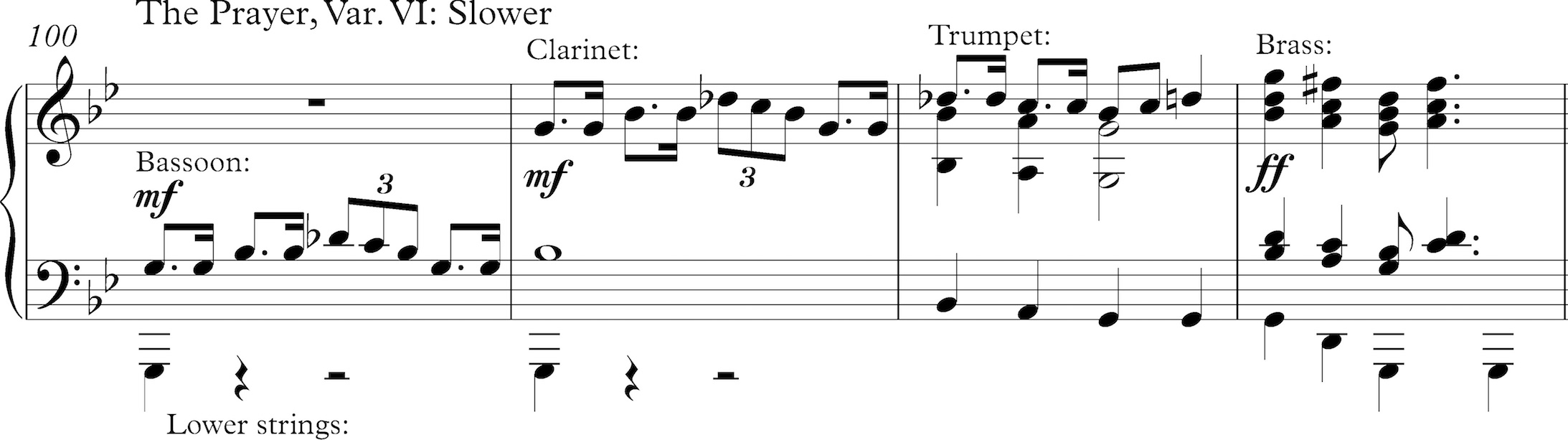

Variation IV (mm. 100-127) is labeled "The Prayer," and takes the tempo down considerably. A dotted bluesy

figure moves from the bassoon to the clarinet to the trumpet, as though different voices in the congregation

are calling out.

The theme and ostinato start up again in m. 113, played by the winds and brasses.

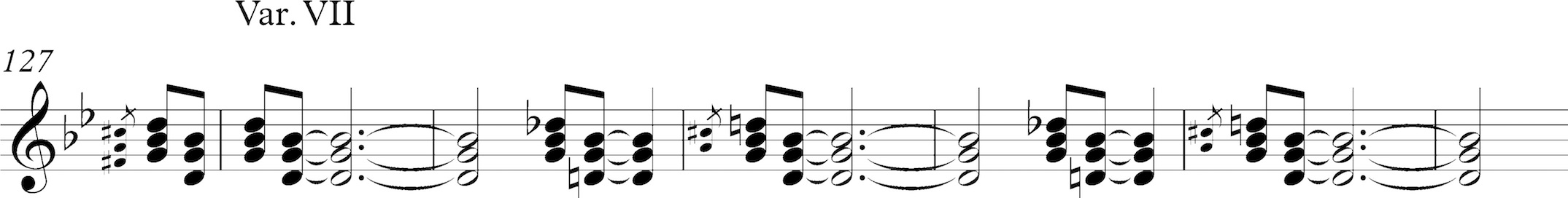

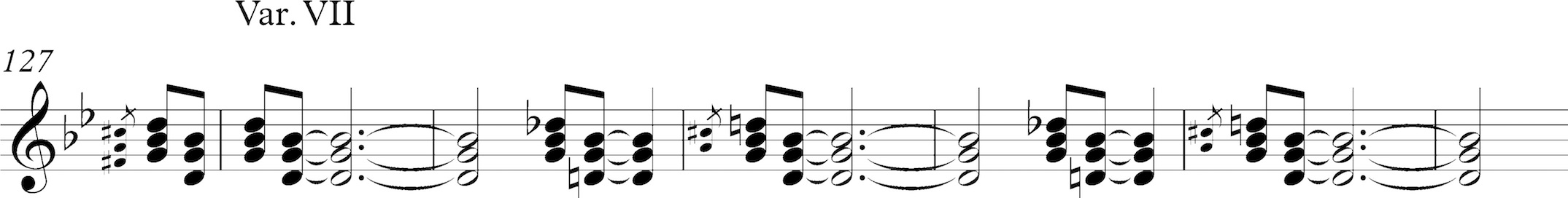

Variation VII (mm. 128-143) picks up the tempo to a quick two-step, and a note in the score indicates this brief variation is to be repeated, as though this were an afterthought. The trombone plays the theme as the strings sweep downward over and over through the ostinato. The focus, though, is a bluesy figure in the trumpets.

At m. 144 the Finale begins. A quick introduction goes through V/ii and V/VII chords to Bb, the second time

turning to a German sixth and landing on a dominant. The entire movement has been in G minor, but at m. 158 the

theme starts up and modulates, going into a Bb dominant and stating part of the theme in Eb minor. It makes its

way to Bb minor, and them moves chromatically to a D dominant at m. 170. The final seven measures precipitously

reinstate G minor over a chromatic bass line, and rise to a triumphant Picardy third.

Copyright 2019 Kyle Gann

Return to American Symphonies

Return to the home page

1894-1955 James P. Johnson was the finest popular pianist of his time, the seminal creator of the stride style bridging ragtime and jazz, the composer of “The Charleston,” and the creator of long-form classical works that incorporated African American motifs. His influence on every key jazz musician who followed is incalculable, as was his “soundtrack for the Roaring 20s.”

Johnson was soon a regular among the “piano professors” who performed at cabarets, bordellos, and rent parties in the San Juan Hill area of the west 60s near New York City’s famed Hell’s Kitchen. He first learned from, and then became the rising star among, such colorfully nicknamed piano “ticklers” as Abba Labba, Lucky Roberts, Willie The Lion, The Beetle, and Jack The Bear. As he became increasingly accomplished and prominent, a younger generation became protégés to him. These included a young Duke Ellington and Fats Waller who would go on to popularize the “stride” style that Johnson pioneered. This style was a bridge between its predecessor, ragtime, and its ultimate successor called jazz. It featured a two-count left hand with a great degree of improvisational freedom in the right hand, combined with polyrhythmic syncopation; and Johnson’s exceptional talent and technique lent itself to the form. In the words of black musical theater great James Weldon Johnson, “It was music of a kind I had never heard before….”

Beginning in approximately 1915 and continuing until the advent of the phonograph record in the early 1920s, Johnson became a prolific maker of hundreds of piano rolls for player pianos. Legend holds that Fats Waller learned all of Johnson’s improvisations by laying his fingers on the piano’s depressed keys as the roll operated the instrument. Johnson was the first African American staff performer for the Chicago-based QRS Company, publisher of piano rolls, in 1921, where he met and befriended George Gershwin. The two master composers would ultimately collaborate on several shows. That same year, Johnson wrote the first of some 200 songs he would compose over the course of his career. Early successes included the up-tempo “Carolina Shout” of 1921 and “The Harlem Strut,” as well as the more introspective “Blueberry Rhyme” and “Snowy Morning Blues.” In addition to his solo performing and recording career, Johnson was featured in several ensembles, and became the accompanist of choice for such blues divas as Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters. In 1922, he began making 78 rpm records, and is credited with the first recorded jazz piano solo in that format on “Bleeding Heart Blues.”

Rounding out his broad range of achievement, Johnson also composed for 16 musical shows including 1923’s Runnin’ Wild, and he continued writing popular tunes with great success. He was accepted for membership in the American Society for Composers and Authors in 1926, in which year he wrote one of his most famous and popular songs, “If I Could Be with You One Hour Tonight.” But it was “The Charleston” that remains his best-known composition. The song was probably written in 1913, and debuted with Runnin’ Wild 10 years later. The song launched the dance fad of the same name, went on to become the “soundtrack for the Roaring 20s,” and has endured as the iconographic music of that exuberant era. Johnson was also responsible for the black review Keep Shufflin’, co-written with his former student Fats Waller in 1928.

Despite ill health due to occasional strokes, Johnson continued performing in clubs with small swing groups and such collaborators as Eddie Condon through the 1940s, and recording for virtually every major label. A serious health-related episode forced him into retirement in 1951, and he died in New York on November 17, 1955. He was elected by a jazz critics poll into the Down Beat Hall of Fame in 1992, acknowledging his seminal contribution to the creation of modern music in all forms. In 1994, much of his symphonic music was found and recorded by the Concordia Orchestra and performed live in concert. His direct influence can be heard in the work of Waller, Ellington, Count Basie, Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, and more contemporary players such as Erroll Garner and Thelonious Monk; but in a real sense, everybody’s fingers have followed James P. Johnson’s.

Johnson grew up listening to the ragtime of Scott Joplin and always retained links to the ragtime era, playing and recording Joplin's "Maple Leaf Rag",[8] as well as the more modern (according to Johnson) and demanding "Euphonic Sounds", both several times in the 1940s. Johnson, who got his first job as a pianist in 1912, decided to pursue his musical career rather than return to school. From 1913 to 1916 Johnson spent time studying the European piano tradition with Bruto Giannini.[9] Over the next four to five years Johnson continued to progress his ragtime piano skills by studying other pianists and composing his own rags.[9]

In 1914, while performing in Newark, New Jersey with singer Lillie Mae Wright, who became his wife three years later, Johnson met Willie Smith. Smith and Johnson shared many of the same ideas regarding entertainers and their stage appearance. These beliefs and their complementary personalities led the two to become best friends. Starting in 1918, Johnson and Wright began touring together in the Smart Set Revue before settling back in New York in 1919.[9]

Before 1920 Johnson had gained a reputation as a pianist on the East coast on a par with Eubie Blake and Luckey Roberts and made dozens of player piano roll recordings initially documenting his own ragtime compositions before recording for Aeolian, Perfection (the label of the Standard Music Roll Co., Orange, NJ), Artempo (label of Bennett & White, Inc., Newark, NJ), Rythmodik, and QRS during the period from 1917 to 1927.[10] During this period he met George Gershwin, who was also a young piano-roll artist at Aeolian.[11]

Johnson was a pioneer in the stride playing of the jazz piano. "Stride piano has often been described as an orchestral style and indeed, in contrast to boogie-woogie blues piano playing, it requires a fabulous conceptual independence, the left hand differentiating bass and mid-range lines while the right supplies melodic issues." Johnson honed his craft, playing night after night, catering to the egos and idiosyncrasies of the many singers he encountered, which necessitated being able to play a song in any key. He developed into a sensitive and facile accompanist, the favorite accompanist of Ethel Waters and Bessie Smith. Ethel Waters wrote in her autobiography that working with musicians such as, and most especially, Johnson "...made you want to sing until your tonsils fell out".

As his piano style continued to evolve, his 1921 phonograph recordings of his own compositions, "Harlem Strut", "Keep Off the Grass", "Carolina Shout", and " Worried and Lonesome Blues " were, along with Jelly Roll Morton's Gennett recordings of 1923, among the first jazz piano solos to be put onto record. Johnson seemed to be at his finest when he attacked the piano as if it were a drum set. These technically challenging compositions would be learned by his contemporaries, and would serve as test pieces in solo competitions, in which the New York pianists would demonstrate their mastery of the keyboard, as well as the swing, harmonies, and improvisational skills which would further distinguish the great masters of the era.

The majority of his phonograph recordings of the 1920s and early 1930s were done for Black Swan (founded by Johnson's friend W.C. Handy, where William Grant Still served in an A&R capacity) and Columbia. In 1922, Johnson branched out and became the musical director for the revue Plantation Days. This revue took him to England for four months in 1923. During the summer of 1923 Johnson, along with the help of lyricist Cecil Mack, wrote the revue Runnin' Wild. This revue stayed on tour for more than five years as well as showing on Broadway.

In the Depression era, Johnson's career slowed down somewhat. As the

swing era began to gain popularity within the African-American

communities, Johnson had a hard time adapting, and his music would

ultimately become unpopular. The cushion of a modest but steady income

from his composer's royalties allowed him to devote significant time to

the furtherance of his education, as well as the realization of his

desire to compose "serious" orchestral music. Johnson began to write for

musical revues, and composed many now-forgotten orchestral music

pieces. Although by this time he was an established composer, with a

significant body of work, as well as a member of ASCAP,

he was nonetheless unable to secure the financial support that he

sought from either the Rosenwald Foundation or a Guggenheim Fellowship;

he had received endorsement for each from Columbia Records executive and

long-time admirer John Hammond.

The Johnson archives include the letterhead of an organization called

"Friends of James P. Johnson", ostensibly founded at the time

(presumably in the late 1930s) in order to promote his then-idling

career. Names on the letter-head include Paul Robeson, Fats Waller, Walter White (President of the NAACP), the actress Mercedes Gilbert and Bessye Bearden, the mother of artist Romare Bearden.

In the late 1930s Johnson slowly started to re-emerge with the revival

of interest in traditional jazz and began to record, with his own and

other groups, at first for the HRS label. Johnson's appearances at the Spirituals to Swing concerts at Carnegie Hall in 1938 and 1939 were organized by John Hammond, for whom he recorded a substantial series of solo and band sides in 1939.

Johnson suffered a stroke (likely a transient ischemic attack) in August 1940. When Johnson returned to action, in 1942, he began a heavy schedule of performing, composing, and recording, leading several small live and groups, now often with racially integrated bands led by musicians such as Eddie Condon, Yank Lawson, Sidney de Paris, Sidney Bechet, Rod Cless, and Edmond Hall. In 1944, Johnson and Willie Smith participated in stride piano contests in Greenwich Village from August to December. He recorded for jazz labels including Asch, Black and White, Blue Note, Commodore, Circle, and Decca. In 1945, Johnson performed with Louis Armstrong and heard his works at Carnegie Hall and Town Hall. He was a regular guest star and featured soloist on Rudi Blesh's This is Jazz broadcasts, as well as at Eddie Condon's Town Hall concerts and studied with Maury Deutsch, who could also count Django Reinhardt and Charlie Parker among his pupils.

In the late 1940s, Johnson had a variety of jobs, including jam sessions at Stuyvesant Casino and Central Plaza, as well as becoming a regular on Rudi Blesh's radio show. In 1949 as an 18-year-old, actor and band leader Conrad Janis put together a band of aging jazz greats, consisting of James P. Johnson (piano), Henry Goodwin (trumpet), Edmond Hall (clarinet), Pops Foster (bass) and Baby Dodds (drums), with Janis on trombone.[12] Johnson permanently retired from performing after suffering a severe, paralyzing stroke in 1951. Johnson survived financially on his songwriting royalties while he was paralyzed. He died four years later in Jamaica, New York and is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Maspeth, Queens. Perfunctory obituaries appeared in even The New York Times. The pithiest and most angry remembrance of Johnson was written by John Hammond and appeared in Down Beat under the title "Talents of James P. Johnson Went Unappreciated".

1928 saw the premier of Johnson's rhapsody Yamekraw, named after a black community in Savannah, Georgia. William Grant Still was orchestrator and Fats Waller the pianist as Johnson was contractually obliged to conduct his and Waller's hit Broadway show Keep Shufflin. Harlem Symphony, composed during the 1930s, was performed at Carnegie Hall in 1945 with Johnson at the piano and Joseph Cherniavsky as conductor. He collaborated with Langston Hughes on the one-act opera, De Organizer. A fuller list of Johnson's film scores appears below.

Harlem Stride is distinguished from ragtime by several essential characteristics: ragtime introduced sustained syncopation into piano music, but stride pianists built a more freely swinging rhythm into their performances, with a certain degree of anticipation of the left (bass) hand by the right (melody) hand, a form of tension and release in the patterns played by the right hand, interpolated within the beat generated by the left. Stride more frequently incorporates elements of the blues, as well as harmonies more complex than usually found in the works of classic ragtime composers. Lastly, while ragtime was for the most part a composed music, based on European light classics such as marches, pianists such as Waller and Johnson introduced their own rhythmic, harmonic and melodic figures into their performances and, occasionally, spontaneous improvisation. As the second generation stride pianist Dick Wellstood noted, in liner notes for the stride pianist Donald Lambert, most of the stride pianists of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s were not particularly good improvisers. Rather, they would play their own, very well worked out, and often rehearsed variations on popular songs of the day, with very little change from one performance to another. It was in this respect that Johnson distinguished himself from his colleagues, in that (in his own words), he "could think of a trick a minute". Comparison of many of Johnson's recordings of a given tune over the years demonstrates variation from one performance to another, characterised by respect for the melody, and reliance upon a worked out set of melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic devices, such as repeated chords, serial thirds (hence his admiration for Bach), and interpolated scales, on which the improvisations were based. This same set of variations might then appear in the performance of another tune.

On September 16, 1995 the U.S. Post Office issued a James P. Johnson 32-cent commemorative postage stamp.[14]

Unmarked since his death in 1955, his grave was re-consecrated with a

headstone paid for with funds raised by an event arranged by the James

P. Johnson Foundation, Spike Wilner and Dr. Scott Brown on October 4,

2009.[16]

Johnson's complete Blue Note recordings (solos, band sides in groups led by himself as well as Edmond Hall and Sidney DeParis) were issued in a collection by Mosaic Records. The largest anthology of Johnson's recordings was compiled in the Giants of Jazz series by Time-Life Music. This three-LP collection contains 40 sides recorded from 1921 to 1945, and is supplemented with extensive liner notes, including a biographical essay by Frank Kappler, and criticism of the musical selections by Dick Wellstood, and the musicologist, Willa Rouder. Many of Johnson's approximately 60 piano rolls, recorded between 1917 and 1927, have been issued on CD on the Biograph Label. A book of musical transcriptions of Johnson's piano roll performances of his own compositions has been prepared by Dr. Robert Pinsker, to be published through the auspices of the James P. Johnson Foundation.

Porter, Lewis. "Deep Dive: Putting Louis Armstrong in Context". Wbgo.org. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

"James P. Johnson | American composer and pianist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

Schiff, David (February 16, 1992). "POP MUSIC; A Pianist With Harlem on His Mind". Nytimes.com. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

"James P. Johnson | American composer and pianist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

Garraty, John Arthur; Carnes, Mark Christopher; Societies, American Council of Learned (January 1, 1999). American national biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195206357.

Jasen, David A.; Jones, Gene (October 11, 2013). Black Bottom Stomp: Eight Masters of Ragtime and Early Jazz. Routledge. ISBN 9781135349356.

Banfield, William C. (January 1, 2004). Black Notes: Essays of a Musician Writing in a Post-album Age. Scarecrow Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780810852877.

Berlin, Edward A. (January 11, 1996). King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780195356465.

"Oxford AASC: Johnson, James P." Webcache.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

"James P. Johnson". Redhotjazz.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

Peyser, Joan (2006). The Memory of All that: The Life of George Gershwin. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 59. ISBN 9781423410256.

Uhl, Jim (September 2002). "For Conrad Janis, Acting and Jazz Share the Spotlight". Maria and Conrad Janis.

Runnin' Wild at the Internet Broadway Database

Meddings, Mike. "James P. Johnson and Jelly Roll Morton First Day Cover". Monrovia Sound Studio. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

"ASCAP 2007 Jazz Wall of Fame". American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

JAMES P. JOHNSON

Ironically, Johnson, the most sophisticated pianist of the 1920s, was also an expert accompanist for blues singers and he starred on several memorable Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters recordings. In addition to his solo recordings, Johnson led some hot combos on records and guested with Perry Bradford and Clarence Williams; he also shared the spotlight with Fats Waller on a few occasions. Because he was very interested in writing longer works, Johnson (who had composed "Yamekraw" in 1927) spent much of the '30s working on such pieces as "Harlem Symphony," "Symphony in Brown," and a blues opera. Unfortunately much of this music has been lost through the years. Johnson, who was only semi-active as a pianist throughout much of the '30s, started recording again in 1939, often sat in with Eddie Condon, and was active in the '40s despite some minor strokes. A major stroke in 1955 finished off his career. Most of his recordings have been reissued on CD.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/jamespjohnson

James P. Johnson

James P. Johnson

Back during the heyday of ragtime piano (pre-1920), James P. had

become a part of the famed “Harlem music scene,” and was contributing to

the distinctive Harlem piano style that differed melodically and

harmonically from classic ragtime. Conventional ragtime had syncopation

but lacked polyrhythm. James P. developed a strong and solid walking

bass with his left hand and a rhythmic exciting treble with his right.

His music flowed at an even tempo with considerable syncopation between

the two hands. He superimposed conflicting rhythms in solos of

symmetrical beauty.

James Price Johnson was born in New Brunswick, N.J., in 1894. His mother taught him rags, blues, and stomps as soon as he was able to handles the keys on the parlor upright. When Jimmy reached 9 years of age, he started lessons with Bruto Giannini, a strict musician from the old country, who corrected his fingering but didn't interfere with his playing of rags and stomps.

The Johnson family moved into New York City when Jimmy was 12, and early in his teens he became the “piano kid” at Barron Wilkin's Cabaret in Harlem. It was at Barron's that he met Charles L. (Lucky) Roberts from whom he derived his brilliant right hand. Later his solid bass was inspired by the work of Abba Labba, a “professor” in a bordello. Through the years James P. kept up his studying, and in the 1930s he began the study of orchestral writing for concert groups.

James Price Johnson was born in New Brunswick, N.J., in 1894. His mother taught him rags, blues, and stomps as soon as he was able to handles the keys on the parlor upright. When Jimmy reached 9 years of age, he started lessons with Bruto Giannini, a strict musician from the old country, who corrected his fingering but didn't interfere with his playing of rags and stomps.

The Johnson family moved into New York City when Jimmy was 12, and early in his teens he became the “piano kid” at Barron Wilkin's Cabaret in Harlem. It was at Barron's that he met Charles L. (Lucky) Roberts from whom he derived his brilliant right hand. Later his solid bass was inspired by the work of Abba Labba, a “professor” in a bordello. Through the years James P. kept up his studying, and in the 1930s he began the study of orchestral writing for concert groups.

James P., Lucky Roberts, Willie (The Lion) Smith, and the Beetle (Stephen Henderson), were familiar figures around “The Jungle” (on the fringe of San Juan Hill in the west 60s when this older Negro district was thriving before 1920.) They followed in the footsteps of Jack The Bear, Jess Pickett, The Shadow, Fats Harris, and Abba Labba.

Here and in the later uptown Harlem, the house rent parties flourished and the boys who could tinkle the ivories were fair haired. Willie The Lion recalled those days for Rudi Blesh as follows: “A hundred people would crowd into one seven-room flat until the walls bulged. Plenty of food with hot maws (pickled pig bladders) and chitt'lins with vinegar, beer, and gin, and when we played the shouts everybody danced.” Long nights of playing piano at such festivities gave James P. plenty of practice at the keyboard.

There were two younger jazz pianists who followed Jimmy Johnson around during these Harlem nights. One was young Duke Ellington, fresh from Washington, and the other was James P.'s most noted pupil, the late Fats Waller. The latter cherished the backroom sessions with James P., Beetle, and The Lion.