SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2020

VOLUME EIGHT NUMBER ONE

HERBIE HANCOCK

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

MELBA LISTON

(November 30-December 6)

KENNY CLARKE

(December 7-13)

LEONTYNE PRICE

(December 14-20)

JIMMY LYONS

(December 21-27)

PATRICE RUSHEN

(December 28-January 3)

ELVIN JONES

(January 4-10)

GARY BARTZ

(January 11-17)

HALE SMITH

(January 18-24)

BENNY CARTER

(January 25-31)

BENNY GOLSON

(February 1-7)

BENNY BAILEY

(February 8-14)

SKIP JAMES

(February 15-21)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/hale-smith-mn0000659883

Hale Smith

(1925-2009)

Artist Biography by James Reel

Hale Smith was one of the first African American composers to abandon black folk music and, in the 1950s, become a mainstream modernist. As an accomplished jazz pianist and arranger, though, he insinuated elements of progressive jazz into his predominantly serial music in a fusion that always seemed entirely natural.

Smith's early exposure to music revolved around the classics, through children's concerts by the Cleveland Orchestra and study of piano scores. He wasn't seriously introduced to jazz until he was 13, but within weeks was playing jazz gigs in nightclubs. After military service, he studied piano with Dorothy Price and composition with Marcel Dick at the Cleveland Institute of Music, obtaining a master's degree in 1952. During this time, he was conductor and composer at a Cleveland community arts center called Karamu House, the source of the core cast of a 1952 production of Porgy and Bess. He became acquainted with poet Russell Atkins and fell under the spell of his Psychovisual Perspective for Musical Composition, a treatise theorizing that the transmission of thought can be represented by a composition's sonic relationships. Smith responded to Atkins' work by conceiving his music as a series of images, however abstract.

Smith began serious composition in the early to mid-'50s, a time when serialism was sweeping America, in the composer's atelier if not in the concert hall. He wholeheartedly fell in with the modernists, largely ignoring the interest of such predecessors as William Grant Still in African American folk music. Smith did, however, retain a deep interest in jazz and ragtime that influenced his rhythms (he referred to his own "delayed approach to the beat") and some of his chord structures; he was especially fond of planting sevenths and ninths in beds of quasi-atonality. Even so, he did not write "third stream" music; only in a few pieces, such as the 1965 piano suite Faces of Jazz, did jazz elements begin to outweigh his precisely notated, highly chromatic style. This is heard to best effect in his three major orchestral works of the 1960s and '70s, Contours for Orchestra, Innerflexions, and Ritual and Incantations, each recorded shortly after its premiere. He adopted a somewhat more lyrical approach in his writing for voice (notably the song cycle The Valley Wind) and solo strings.

He knew jazz inside and out, though; in 1958, he moved to New York City and began writing music for film and television and arranging for such jazzmen as Chico Hamilton, Dizzy Gillespie, Eric Dolphy, Ahmad Jamal, and Oliver Nelson. He also worked as an editor and consultant with several music publishers. Simultaneously, his classical output began to increase, peaking in the 1970s while teaching at the University of Connecticut. In 1984, he announced that he was retiring from teaching to devote full time to composing and arranging, but his concert hall composing fell off except for a spurt of music in 1990 - 1991, including Dialogues and Commentaries for Seven Players and the vocal trio Tra La La Lamia.

https://nmbx.newmusicusa.org/Hale-Smith-19252009/

Hale Smith (1925-2009)

by T. J. Anderson

November 30, 2009

New Music USA

On November 24, 2009, America lost Hale Smith, one of its most important composers. His works musically intertwined the dialectic between African American identity and European traditions. In his music, an obtuse meditational enlightenment with sounds focuses on the successful as well as the tragic confrontations human beings have with each other and the universe. His work was unique and particularly personal because of Hale’s philosophy and economy of means. Rooted in contemporary expression, Hale Smith set out to resolve the paradoxes of both improvisation and notated music. Influenced by jazz, closed and open forms, graphic and proportional notation, as well as aleatoric and serial thinking, each of his compositions embraced a different ambiance and reflected a fresh manifestation of his personality.

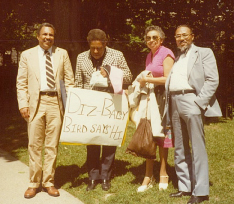

T.J. Anderson and Dizzy Gillespie with Juanita and Hale Smith at Tufts, 1980; photo by Lois Anderson

This accomplished composer’s list of friends in music was legendary and included Beryl Rubinstein, Benny Carter, William Dawson, William Grant Still, Langston Hughes, Eric Dolphy, Dizzy Gillespie, Muhal Richard Abrams, Randy Weston, Hall F. Overton, Olly Wilson, George Walker, Melba Liston, Ulysses Kay, Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., Raoul Abdul, Alvin Singleton, Kathleen Battle, Malcolm J. Breda, Coleridge Taylor Perkinson, Dominique René De Lerma, Regina Baiocchi, William Banfield, and Howard Swanson.

Hale Smith was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1925. His mother and his father, Hale Smith, Sr. (the owner of a printing shop), had a profound influence on his creative development. Educated in the public schools of Cleveland, he was drafted into the military and served from 1943 to 1945. Later, he studied composition with his principal teacher, Marcel Dick, at the Cleveland Institute of Music. This led to a B.Mus. in 1950 and a M.Mus. in 1952, and in 1998, he received an honorary doctorate. In 1959, he left for New York for positions as an editor, advisor, and copyright consultant for several publishing houses including C. F. Peters, E. B. Marks, Frank Music Corporation, and Sam Fox Music Publishing. In 1970, he became a professor at the University of Connecticut and retired from that position in 1984.

While performing as a jazz pianist and working as a jazz arranger occupied some of his attention, creating classical music became paramount. Solo pieces, duos, chamber ensembles, string orchestra works, large orchestra pieces, compositions for soloist and orchestra, band, jazz ensembles, choir and incidental music are all a part of his creative output. Compositions of particular note are his In Memoriam, Beryl Rubinstein (1953) for choir and orchestra and the Sonata for Cello and Piano (1955). In 1965, Faces of Jazz and the following year, Evocation, both for piano, attracted attention. Innerflexions was written in 1977 at the request of Dr. Leon Thompson, director of Educational Projects, the New York Philharmonic. Hale Smith’s choral composition, Toussaint L’Ouverture was presented two years later, and in 1979 Thompson commissioned Solemn Music for organ and brass instruments. Three Patterson Lyrics was completed in 1985, a work for soprano and piano. And he continued to show mastery of styles, genres, and African American musical traditions in Dialogues and Commentaries (1990-91), a chamber ensemble composition written for Richard Pittman and Boston Musica Viva.

The composer Wallingford Riegger called The Valley Wind (1952-55) for soprano and piano, “an important contribution to our quite limited good song literature.” That statement was the earliest recognition of Hale Smith’s contributions, but in later years his accolades were many. In 1973, he became the first African American to receive the Cleveland Art Prize in Music, which marked a decisive turning point in his life. In 1982, the Outstanding Achievement Award came from the National Association for the Study and Performance of African American Music. The American Academy of Arts and Letters presented him with the Composer’s Recording Award in 1988. [Ed. Note: In 2001, Hale Smith was awarded the American Music Center’s Letter of Distinction.]

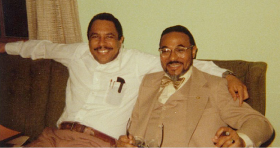

T. J. Anderson and Hale Smith in Winchester, MA 1977; photo by Lois Anderson

Hale Smith’s sense of humor and provocative gift of conversation were legendary. His desire to stay youthful was evident even to the point of asking his grandchildren to call him “Pete” and not “Grandpa.” But his passionate disdain for minimal and rap music was a constant in his later years. However, most important was bearing witness to his love for his wife of sixty one years, Juanita Hancock Smith, an American love story that forever framed his life. We will no longer see this articulate man, dressed in a suit or sport coat wearing a bow tie, several large Monte Blanc pens in his shirt pocket and large cigars in his coat pocket. His great capacity to love so many people and create beautiful music is one of our precious legacies.

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/smith-hale-1925-2009/

Hale Smith (1925–2009)

by Marianne Hanson

February 1, 2013

Black Past

Performer, composer, arranger and teacher, Hale Smith, Jr., encompassed the worlds of jazz and classical music. Beginning with his childhood in Cleveland, Ohio, he trained in jazz and classical composition, performance, and teaching. His collaborations and influence crossed multiple fields where he set out to resolve the paradoxes of both improvisation and notated music.

Hale Smith, Jr. was born June 29, 1925 in Cleveland, Ohio to parents Hale and Jimmie Smith. Beginning piano at age seven, he was introduced to composing and collecting musical scores. His father owned a printing business and his parents were highly supportive. By high school he was playing jazz piano and composing. One of his early compositions was encouraged by Duke Ellington.

After military service in World War II (1943-45) he received a B.A. degree (1950) and M.A. (1952) from the Cleveland Institute of Music. Smith’s first opera, Blood Wedding, premiered in Cleveland in 1953. Moving to New York in 1958, he became an editor, advisor, and copyright consultant for several publishing houses. In 1960 he received a commission from BMI (Broadcast Music, Inc.), one of the major music licensing and performing rights companies, for his work Contours for Orchestra. He also taught at C.W. Post College on Long Island, New York until 1970.

Smith performed as a jazz pianist and arranger in New York. He worked with prominent jazz artists, including Chico Hamilton, Dizzy Gillespie, Eric Dolphy, Randy Weston, Melba Liston, Ahmad Jamal, and Oliver Nelson among many others. His influence was also felt as his students and colleagues mingled in the blending of jazz and classical ventures.

In 1970 Smith became a professor of Music at the University of Connecticut, where he taught until he retired in 1984. During this period composing classical music became paramount with solo pieces, duos, chamber ensembles, choir, and incidental music. Among his compositions are In Memoriam, Beryl Rubinstein (1953), Faces of Jazz (1965), and Innerflexions (1977), all for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1979 he wrote Toussaint L’Ouverture followed in 1985 by Three Patterson Lyrics for soprano and piano and Dialogues and Commentaries (1990-91). His arrangements of spirituals were favorites of Kathleen Battle and Jessye Norman.

In 1973 Smith became the first African American to receive the Cleveland Art Prize in Music. Other awards included an honorary doctorate degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music, serving on the New York State Council on the Arts from 1993 to 1997 and service on the boards of several composers’ organizations. In 2001 Smith was awarded the American Music Center’s Letter of Distinction.

Hale Smith died on November 24, 2009 from complications related to a stroke. He was 84. Surviving were Juanita Smith, his wife of 61 years, four children, and three grandchildren.

http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2013/02/07/one_drop_rule_of_jazz_wayne_shorter_duke

Slate's Culture Blog

The “One Drop Rule” of Jazz

by Seth Colter Walls

February 7, 2013

Slate

Wayne ShorterPhoto

by SEBASTIEN NOGIER/AFP/Getty Images

As far as shameful cultural secrets go, the fact that African-American composers aren’t featured on our classical music stages as frequently as they should be is one few people bother keeping anymore. “That black composers are poorly represented in mainstream concerts is a germane topic of discussion but one beyond the scope of a single concert review” is how New York Times classical music critic Steve Smith accurately put it last week, when reviewing a Black History Month-timed showcase of oft-overlooked artists.

Outside the strictures of a concert review, though, we can ask the question more directly. And what better time than now, since a broad look at chamber music and orchestral programming in New York, for example, offers little in the way of sustained attention to works by composers like Duke Ellington (who wrote ballets and tone poems), Leroy Jenkins (who was commissioned by German composer Hans Werner Henze to write an opera), or Hale Smith, who composed while teaching inside classical music’s academy (i.e., the way most composers pay the bills), among other underappreciated worthies.

The widely admired conductor Marin Alsop has championed orchestral writing by early stride-piano master James P. Johnson—the composer of “The Charleston”—who also worked on symphonic pieces, sometimes with the help of African-American symphonist William Grant Still. (Alsop continued her campaign recently on the NPR website.) Alsop notes that her advocacy is a reclamation project that comes only decades after a good bit of Johnson’s notated music was lost due to inattention from the classical world. One of the pieces of Johnson’s that I’d most love to hear right now, but cannot, is his one-act opera about the nascent labor movement, De Organizer, which featured a libretto by Langston Hughes. (The piece has recently been partially restored by scholars, though it has yet to be recorded commercially.)

Each of these composers is better known as—or else can be mistaken for—a jazz musician. Ellington, though he strove to be “beyond category,” is obviously essential to any understanding of jazz—yet that shouldn’t prevent us from thinking of him in other contexts. Jenkins was a key member of the jazz avant-garde starting in the late ’60s, but by the 1980s it seems he was devoting as much or more time to formal, traditionally notated works for the stage. As shrewd observers have noted many times before, “The works of African American composers … are often mistakenly classified as jazz.”

The composer, scholar, and sometime jazz trombonist George Lewis calls this “the one-drop rule of jazz,” a metaphor he explained in a brilliant recent book, A Power Stronger Than Itself, as “that holdover from America’s high-eugenics era that decreed that a single blood drop of ‘Negro ancestry’ was enough to render anyone a Negro.” A white musician previously coded as a jazz artist who presents a new work for a classical ensemble is likely to be praised for bravely crossing boundaries. But when a black musician tries the same thing, the entire enterprise is often seen as a strained attempt to cast off or move beyond the jazz identity.

Enter Wayne Shorter, a saxophonist and composer for a couple of Miles Davis’ greatest bands and one-time member of Weather Report who has a new album out on Blue Note records this week. Titled Without A Net, most of its songs rely on the excellent younger musicians who have made up Shorter’s working quartet of the last decade: John Patitucci on bass, Danilo Perez on piano, and Brian Blade on the drums. They are one of the best bands in jazz today, as eight of the nine tracks on the new album demonstrate. Their patient approach to group improvisation and their willingness to take the long way around to a composed theme flirts with being “meandering,” in a pejorative sense—and yet their interplay feels mysteriously tight. It’s a high-wire act that sometimes fails during stretches of a live show. But since Without a Net was culled from several concert recordings made in 2011, the album moves from strength to strength; it’s a highlight reel of “they did what now?” successes.

But on one key track, the quartet behind Shorter’s late-career renaissance takes a backseat to—or more precisely, it shares a seat with—a classical quintet. “Pegasus” is a 23-minute tone poem that is led for extended stretches by the Imani Winds ensemble, which commissioned classical pieces from Shorter before this collaboration. Shorter’s long-serving pianist kicks things off, but soon the juiciest instrumental writing is for the wind quintet. At the next pivot point, Blade’s drums kick in, announcing that the jazz quartet has rejoined the proceedings. The Imani Winds do not retreat; neither the quartet nor the classical ensemble is struggling for pure dominance or the need to stay relevant. It’s not solely a “jazz” piece or a “classical” one, but it’s one of my favorite tracks in either genre this year.

“Pegasus” reappeared in a different version at a Carnegie Hall concert featuring Shorter’s quartet and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra last Friday, after a presentation of works by Beethoven and Charles Ives. The first collaboration between the bands on the bill, this version of “Pegasus” was much shorter and less successful; it sounded like a warm-up. But after it was over, something beautiful and exciting happened: The bands seemed to get comfortable. And once on the same page they stayed there for the rest of the night. Three other jazz-classical hybrid pieces by Shorter were played, one of them a premiere. For me, the final two recalled (in spirit if not tonal approach) Ornette Coleman’s “Skies of America,” with their beautifully arranged moments of meeting, which all concertos depend on—when a solo voice shoots over the top of an orchestra, or has its solitude interrupted by a phalanx of complementary voices.

Reviewing the concert in the New York Times, classical critic Corinna de Fonseca-Wollheim rightly described it as “frequently riveting” and praised the “moments of infectious energy” when describing those performances. Shorter’s harmonies, she said, “like those of Ives, defy expectation even as they maintain a sociable approachability.” I agree. But I dissent from her conclusion that the concert was less than the sum of its parts and that many of the best moments occurred “when the quartet played alone.”

Those comments reminded me of another Carnegie Hall review that ran in the New York Times nearly 70 years ago. Duke Ellington had just premiered his 50-minute work “Black, Brown and Beige” in the same space. At the concert itself—thankfully preserved on CD, albeit with slightly muddy fidelity—Ellington prepared the audience to hear something longer and more ambitious than the traditional jazz number of the time.

And now friends, our latest attempt—probably our most serious attempt—and definitely our longest composition. However, in mentioning the length of “Black, Brown and Beige,” we would like to say that this is a parallel to the history of the American Negro, and, of course, it tells a long story.

This symphony-length piece was also judged by the New York Times to have contained some inspired moments, which, alas, did not measure up to the more traditional tunes played on that evening. “It had many exciting passages,” the paper said of Ellington’s extended essay, “but it was in the shorter works … that the leader seemed most completely himself.”

Ellington took this criticism so hard that he never sought to record his initial version of the work in a studio setting. The editors of the Penguin Guide to Jazz note that Ellington seemed to have lost confidence in the piece, shortening it radically for a recording made over a decade later. But for the scratchy recording of the Carnegie Hall concert, Ellington’s first and most ambitious vision would have been as lost to us as was James P. Johnson’s one-act opera with Langston Hughes.

Yet even if we could still do with more presentations of operas by Johnson, Anthony Davis, or the one by Scott Joplin, at least some sort of measurable progress has been made in the 70 years between the Carnegie Hall premieres by Ellington and Shorter. On the Saturday after their concert, before any reviews had the chance to come out, the saxophonist’s quartet and the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra went into the studio to work on an upcoming album of these same pieces. I’m looking forward to it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Seth Colter Walls is a freelance reporter and critic whose writing has appeared in Newsweek, the Village Voice, the Washington Post and the Awl.

http://clevelandartsprize.org/awardees/hale_smith.html

Hale Smith, Composer, 1925–2009

1973 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR MUSIC

The list of eminent musicians who have performed Hale Smith’s music is as impressive as it is long, and extends to opposite poles of the musical world. It would be sufficient to name such jazz luminaries as John Coltrane, Joe Lovano, Ahmad Jamal, Chico Hamilton, Betty Carter and Eric Dolphy. But then you would have left out the likes of singers Jessye Norman, Kathleen Battle and Hilda Harris, as well as legendary concert pianist Natalie Hinderas, one of the first African Americans to have an important career in classical music, and the New York Philharmonic.

But they were all latecomers, in a matter of speaking, in spotting the musical gifts of this Cleveland-born prodigy. Duke Ellington, shown a composition by the 16-year-old Hale Smith in 1941, was sufficiently impressed to sit down with him and make suggestions as to some fine points. (A few years later, avant-garde composer Wallingford Riegger praised a song sequence young Hale had written as a student that became The Valley Wind.)

Smith, who had been playing classical piano since the age of seven, was already active as a jazz pianist and played mellophone (an instrument similar to the French horn) in the high school band. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that December, however, boded a different future for young Hale.

Upon graduation, 18 months later, he donned a U.S. Army uniform; but once again, recognition of his exceptional gifts soon had him trading his rifle for a stack of music paper. Smith spent much of the next two years arranging music for Army shows that toured camps in Florida and Georgia. After his discharge, he supported himself by playing piano in nightclubs while he filled a notebook with themes for a future suite in the jazz idiom.

In January 1946 he was admitted to the Cleveland Institute of Music where he studied composition and theory with Ward Lewis and 1962 Cleveland Arts Prize winner Marcel Dick, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in 1950 and 1952. His alma mater would one day award him an honorary doctorate for his achievements in the field of music. His Four Songs of 1952 won BMI's first student composition award. His arrangements of spirituals would one day be performed (on many programs) by such eminent sopranos as Kathleen Battle and Jessye Norman.

Relocating in 1958 to New York City, where there were many more opportunities to exercise his craft, Smith became the model of a working artist to a younger generation of black (and white) composers. He served as arranger, mentor, teacher or consultant to such figures as Dizzy Gillespie, Quincy Jones, Horace Silver, Isaac Hayes, Oliver Nelson, Jessye Norman, Ahmad Jamal, Randy Weston and Abbey Lincoln—all while teaching at the C. W. Post campus of Long Island University until 1970, and until 1984 as Professor of Music at the University of Connecticut-Storrs.

The influence of jazz is often apparent in his own compositions for orchestra and chorus, which also sometimes employ serial techniques. These include Ritual and Incantations (recorded by the Detroit Symphony for Columbia and by the Chicago Sinfonietta for volume 2 of the African Heritage Symphonic Series), Innerflections for orchestra (recorded by the Slovenian Symphony Orchestra) and Contours for Orchestra (by the Louisville Symphony Orchestra).

His many and varied pieces for chamber orchestra—such as Introduction, Cadenzas and Interludes for Eight Players and A Ternion of Seasons (“Give Me the Splendid Silent Sun,” “Rhodora,” and “A Final Affection”), string orchestra (By Yearning and By Beautiful) and band (March and Fanfare for an Elegant Lady; Somersault: A Twelve Tone Adventure for Band) have been widely performed and published.

His prolific output includes everything from TV advertising jingles to incidental music for stage productions of Lysistrata and Lorca's Blood Wedding. His “Castle House Rag” was used in the documentary The Making of Citizen Kane. Smith has, nevertheless, always found time to lend his prodigious energies to such important undertakings as the Detroit Symphony’s annual Symposium on Black American Composers. He gladly served as an advisor to the Chicago-based Center for Black Music Research, but “bristled at the designation [Black composer],” The New York Times noted in its lengthy obituary. “He wanted his work, and that of his black peers, to appear on programs with that of Beethoven, Mozart and Copland” and to be judged simply as music.

In addition to being awarded the 1973 Cleveland Arts Prize, Hale Smith has been honored by the American Academy and Institute of Arts & Letters and by the Black Music Caucus of MENC for “outstanding achievement.” He was also appointed to the New York Council on the Arts by Governor Mario Cuomo.

Fittingly, this one-time CIM student who treasured the music of such forebears as R. Nathaniel Dett (Smith orchestrated Dett’s stirring “Chariot Jubilee” for the 1998 NPR broadcast of the Martin Luther King Memorial Concert at Morehouse College) has himself become the subject of scholarly articles and dissertations. A week-long series of interviews with Smith commissioned by the Smithsonian fills some 15 cassettes.

For more about the composer, including a full list of his compositions and sound samples of several recordings, visit marilynharris.com/halesmith.html

Cleveland Arts Prize

P.O. Box 21126 • Cleveland, OH 44121 • 440-523-9889 • info@clevelandartsprize.org

https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/music-notes-hale-smith-makes-poetry-sing/Content?oid=898696

Music Notes: Hale Smith makes poetry sing

by Ted Shen

March 18, 1999

Chicago Reader

"Langston Hughes was one never to forget an artistically inclined child," says jazz and classical composer Hale Smith. "He came to my high school in Cleveland in '42--which he'd attended briefly many years earlier--and I was in the crowd to greet him. I handed him a sheet of music that I'd written. He autographed it. Four years later, right out of the army, I was in Harlem for a visit. I ran into him at the post office on 125th Street. He saw me and said, 'Say, aren't you from Cleveland? Are you still writing music?' I was astonished that he could remember a kid from four years ago! He was that kind of a man."

The famous poet and the aspiring composer became pen pals, and the friendship deepened after Smith moved to New York in 1958 for a teaching job. "I became a part of the wide circle of artists that hung around him," says Smith. "He was interested in my music, and I was, of course, interested in his writings." They talked about collaborating but never got around to it. Smith did turn a number of Hughes's poems into songs, as did many other composers, including Kurt Weill, who appreciated the cadence and rich allusions in Hughes's verse. "Some of his poetry is plain doggerel--in fact, he wrote a couple of homages to dogs--but most of it is very lyrical, a composer's dream," Smith says.

Hughes, who had written some opera librettos, intended some of his poems to be read to music; he thought one series would be ideal for Muddy Waters. In 1961, six years before his death, he produced an opus that combined his love for the spoken word, jazz, and blues in one swoop. Ask Your Mama: Twelve Moods for Jazz, says Smith, is the granddaddy of rap. "The title refers to a verbal game that holds resonance for blacks to this day--an art of talking in verse about another person's ancestry, humorlessly and with malice. Something like 'Your grandmama wears no drawers because she has no drawers.' All this is a form of anecdotal storytelling as old as The Arabian Nights."

The poem's 12 sections are stream-of-consciousness meditations on the African-American experience. "Hughes wanted to address the racial configuration of the time, the late 50s, right before Martin Luther King," Smith says. "In the poem, he's angry, he's amused, he's ironic, he's moody. He pays respect to black pioneers, many of whom I myself knew. One [Zelma Watson George] is the soprano who sang in Menotti's The Medium when so few black singers had lead roles on Broadway. Another is Inez Cavanaugh, who ran the famous Chez Inez, across from the Sorbonne in Paris, where many Negro jazz musicians performed."

Four years ago singer Rawn Spearman asked Smith to arrange the music for a recitation of Ask Your Mama at a Hughes festival in New York. Smith jumped at the chance. "I thought I could at last honor Hughes," Smith says. In the margins of the manuscript the poet had written the titles of specific songs or indicated the type of music that would be appropriate. "I observed his notes scrupulously--it was like working with him right next to me." Smith incorporated all of the tunes and added some others, fashioning a score for a jazz band that he believes is a counterpart to--and at times counterpoints--the meaning of the text. "I included strains of 'Dixie' for satirical effect," he points out, "and added a syncopated rendition of a 20s catchphrase ['Shave and a haircut, two bits'] as a silly commentary. In a section on Leontyne Price, following Langston's instructions, I played with the fact that she's from Mississippi and sang Schubert's lieder."

The premiere was such a success that Smith, who teaches at Columbia College's Center for Black Music Research, and the Jazz Institute's Lauren Deutsch arranged to present Ask Your Mama with Smith's score as part of the Chicago Jazz and Heritage Program. Margaret Burroughs offered the DuSable Museum of African American History as the venue; she'd known Hughes since the late 30s. "Langston came to Chicago quite often," she recalls. "The University of Chicago or someone else would invite him to read. And each time he'd stop off at the South Side Community Art Center to meet with us. We thought we knew him intimately, maybe also because in the 40s and 50s he had a weekly column in the Defender. He liked people, and he was inspirational....Langston spoke a language that ordinary people could understand. He gave a flawless mirror image of the African-American experience."

Ask Your Mama will be performed at 7:30 Friday and Saturday at the DuSable Museum, 740 E. 56th Place. Singer Maggie Brown and poet Sterling Plumpp will narrate with the accompaniment of an ensemble led by Richard Wang. Burroughs will read "Shakespeare in Harlem," a eulogy she wrote after attending Hughes's funeral. Admission is free. Call 312-747-1430 or 312-427-1676 for more information.

Art accompanying story in printed newspaper (not available in this archive): photo by Nathan Mandell; Langston Hughes uncredited photo.

http://www.bruceduffie.com/halesmith.html

Composer Hale Smith and Composer T. J. Anderson

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

By the beginning of 1987, I had already done quite a number of interviews. I mention this because the experience I had gained allowed me to take advantage of a significant opportunity in this particular case.

As shown in the letter (reproduced above) responding to my inquiry, composer Hale Smith had agreed to meet with me, and that interview was set up for January 26th at his hotel. After we had been speaking together for a few minutes, another gentleman came into the room, and I found out this was T.J. Anderson. He and Smith were old buddies. Smith called T.J. ‘The Boss’, and ‘one of my esteemed colleagues and friends’. Their exchanges made me realize this was someone I should also speak with as an interview guest, and they were both gracious enough to allow me to do so. The result of this double encounter is presented on this webpage.

HALE SMITH is regarded as one of America's finest composers. He also had a distinguished career as an arranger, editor, and educator. Born in Cleveland, Ohio on June 29, 1925, he began study of the piano at age seven, and his initial performance experience included both classical and jazz music. After military service (1943-45), he entered the Cleveland Institute of Music as a composition major, receiving a bachelor's degree in 1950 and a master's degree in 1952. His principal teachers were Ward Lewis in theory, and Marcel Dick, his only teacher of composition.

He moved to New York in 1958 and from that time he worked with many prominent jazz artists, including Chico Hamilton, Dizzy Gillespie, Eric Dolphy, Randy Weston, Melba Liston, Ahmad Jamal, and Oliver Nelson. He also served as an editor and consultant with several music publishers (E.B. Marks, C.F. Peters, Frank Music Corp. and Sam Fox Music Publishers).

In 1952, Smith was a winner of the first Student Composer's Award sponsored by Broadcast Music Inc., and in 1960 was commissioned by BMI to compose Contours for Orchestra. His other works include Ritual and Incantation, Innerflexions, By Yearning and By Beautiful, Music for Harp and Orchestra, Orchestral Set, Mediations in Passage, several chamber music and solo pieces and several works for chorus and solo voice and piano.

Smith received several honors including the Cleveland Arts Prize, and Awards from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, The National Black Music Caucus, and an honorary doctorate from the Cleveland Institute of Music.

He taught at C.W. Post College (Long Island) and was Professor Emeritus from the University of Connecticut. In addition, he served on the boards of several organizations including The American Composers Alliance, Composer's Recordings, Inc., The American Music Center, and several state arts councils. He also was a copyright infringement consultant, and orchestrator and artistic consultant for the Black Music Repertory Ensemble of the Center for Black Music Research Columbia College Chicago. Smith was appointed to the New York State Council on the Arts (1993-1997) by Governor Mario Cuomo.

Smith died after a long illness on November 24, 2009.

In my quest for interviews, one of my main contacts was Barbara Petersen, Vice President of BMI. Knowing her and working with her was rewarding for both of us since she put me in touch with many composers in her stable, and I was thus able to present programs of their music and interviews on WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago. It was also nice because she was married to baritone Roger Roloff, a major Wagner/Strauss singer whom I had known since undergraduate days.

With that in mind, we started our conversation . . . . . . . . .

Hale Smith: Did you know anything about me before Barbara mentioned me? I’m just curious about things like that sometimes!

Bruce Duffie: I wrote to Barbara with a list of requests, so I was the one who came up with your name. I had read about you in Baker’s Biographical Dictionary [edited by Nicolas Slonimsky], and had played a couple of your recordings on the air.

HS: Well, I don’t have too much that’s available anymore, to tell you the truth. Would a cigar bother you? If it would, tell me.

BD: Can I ask you not to? If you can delay it until later, I would appreciate it. It gets into my eyes.

HS: No problem. I’m not hooked! I go days and days without them. That’s the reason I asked the question. [The photo at right shows Smith with a cigar! The only other person who inquired about smoking a cigar during our interview was Daniel Barenboim, and he also graciously agreed not to.]

BD: Thank you very much. I want to talk about music and composing. You’re also a teacher of composition?

HS: I guess that’s true. Officially I am Professor Emeritus in the University of Connecticut.

BD: Perhaps this is a difficult question, but is musical composition something really can be taught, or must it be something that is innate within each person?

HS: I don’t think that’s a difficult question. The ability to express oneself through any art form is something I think is innate. That cannot be taught, but craft is teachable. The best teaching — which is very, very rare in my opinion, especially in the creative area and music composition — is an approach that helps the student to delve within his own resources, and at the same time giving that student a craft that is necessary to express those thoughts or ideas or whatever one might want to call them. I have a favorite analogy where I tell students, or young people in general, having to do with the place of craft and technique in the creative process. The analogy relates to when one first starts learning how to write is like learning to ride a bicycle. One has to be very conscious of every gesture, every shift of balance, the slightest of degree of manipulating the handlebar, the precise degree of pressure on the pedals, the precise rate of speed that the pedals should be turned, and if one miscalculates, the result is that one ends up on the ground. [Both laugh] But one continues to work these problems out, and then eventually, sooner or later, one jumps on the bicycle, starts off, and somewhere down the road he might stop to think, “My goodness, here I’ve been riding this thing around and I didn’t think about it at all! All I had my mind on was where I was going and what I wanted to do!”

BD: And composition is like this?

HS: That’s the way I view the role of craft. It’s indispensable, but until it’s subordinated to the point where you don’t have to think that way, it’s not fully under one’s control. So when one gets out into the world of really creating, one shouldn’t have to stop to think about making a particular chord progression here, or using a certain inversion there, then having to distribute the voices in such a way. By that time, what one thinks about, or should be able to think about, is the piece and what one is doing with it. What one is expressing is purely music, or one is trying to express the way clouds go through a sky. It doesn’t matter to me, but the technique has to be subordinated to the point where one doesn’t have to think about it. I was talking with a teacher down in New Orleans, who is a fine pianist and evidently a good teacher, but I think he has some misconceptions. To me he’s primarily an educator rather than primarily a performer, and he mentioned Wynton Marsalis. We both had read this article where Wynton had made a statement that he never thinks about how he’s going to do something, or what he’s going to play, or how he’s going to play while he’s performing. He does not have time to think what chord is going to be played next, or what notes are going to be played next, or the fingering for the next series of whatever. You just don’t have time for that in performing. So this person, who I like very much, was emphatic that Wynton didn’t fully understand performance because one has to think about those things. I said, “Oh, no. Wynton is precisely correct because when one is in the process of performing, one does not have time to think of those things. Those things are supposed to be part of the equipment, and it’s supposed to be dealt with before you go on the stage.” It’s really funny... I had gone to a recital in New Orleans, and after it I went to the hotel in the French quarter to visit a friend of mine, a fine composer named Roger Dickinson and who plays piano in the Royal Orleans Hotel there. There’s an open lounge there where he plays, and I waited until Roger finished the evening. We went out to the parking area and he was starting to get into his car to pull out so I could follow. We were going someplace for breakfast, when who should walk in but Wynton! [Both laugh] So I told him the story, and he said, “Oh, man, if you try to think of everything you’re going to do like that, it’s gone before you get it!” So that’s what I think about it.

BD: Is it precisely at this point when you no longer have to think about the technique that the real music begins?

HS: I think so, because there you don’t have to think about how you’re going to do it so much.

BD: Now, you’ve been involved in the teaching of music for a number of years. How has the teaching of music changed over ten, fifteen, twenty, thirty years?

HS: In general, you mean?

BD: The teaching of young students of composition, or the young students of music.

HS: I don’t think it’s improved. In fact, if anything, education has declined and musical education has declined. The problem is that there’s too many teachers who go through school, say from elementary and high school through college and get into graduate work without ever getting out into the world itself. They never have a chance of dealing with the application and these ideas, what I call the real world. It’s all about academia. Too many of these students become accustomed to having material handed to them on a platter. They don’t learn to think. They don’t even know what thinking is these days. The name ‘education’ as it’s used today is a misnomer, because all we’re doing is some sort of very extended half-way job training course.

BD: You say the education has declined. Has the standard of performance of young musicians declined, or has that gotten better?

HS: It depends. There is, of course, a very large number of performers, people who are trained to be performers that are coming out of schools every year, and many of these people — at least those coming through qualified music schools — have a pretty fair degree of competency on their instrument. But again, because so little is brought to the training process, where they might be well-trained as instrumentalists, they’re not training well as musicians in my opinion.

BD: So technically they’re very good but not emotionally?

HS: In most cases, yes. You can use that word, but I would call it an expressive capacity, meaning the ability to project some expressive purpose. I don’t really believe too much in who’s going to be emotional when he’s playing the Hearts and Flowers throbbing kind of thing, because somewhere in the performance of music — I don’t care what kind of music it is — the brain has to be involved. And, since education in general seems to be committed to doing anything but developing the capacity of the brain, they do not bring much of that to anything. The evidence of it is what we hear on the radio or on the TV, or what you read in the newspapers and magazine articles, and so on. There’s very little bit of that which is conducive to thought or dealing with serious issues, whether it’s in art or anything else. Frankly, I don’t think it’s a good period in that sense.

BD: Is there any hope, or are we doomed forever?

HS: I don’t believe in anything being doomed forever. Of course there are those out there doing their best to doom it, but it would come from something else! [Both laugh]

BD: Well, let me pursue that just a bit! Who is dooming it, or who is attempting to doom it?

HS: I’ll put it in these terms to keep it from being too particularized. I don’t believe there’s a country on the face of the Earth these days which has a governmental leadership that it can afford, and that goes for all of them. These people who have taken it upon themselves to lead the world are leading it to hell and back and downhill every step of the way, and I don’t see anything getting too much better.

BD: Shouldn’t there be a role of government in the arts?

HS: If you don’t have a general atmosphere of well-being, you can’t have anything else. It’s a fallacy to think that arts really flourish in adversity. No, they don’t. When the so-called ‘good life’ has been appropriated by the financiers of the world, the ‘get-rich-quickers’ of the world, the ‘holier-than-thou’ of the world — whether they’re preachers or followers I don’t care, or whether it’s presidents, mayors and governors of the world — those who have themselves not been cognizant of the fact that they themselves are ignorant of most of what has made the world better in human history, I don’t see that we’re going to improve very much soon. I don’t know whether that’s fair to these people or not, but in an atmosphere like that, art cannot really flourish. In this country, there’s a big to-do about performing arts. A lot of government money — federal state and municipal — is spent on what they call ‘performing arts’. There’s very little said about the creative arts. If we’re talking about dance, we’re eliminating the choreographers. If we talk about actors, we’re eliminating the people who are writing the plays and films scripts. And if we talk about music, we’re eliminating the people who create it, people like myself and other rather good names such as Carter and Babbitt, right through Anderson, especially down to those who are younger coming along, trying to scratch out careers. They have to compete with the giants of the past because it’s to the benefit of a Program Director on a radio station, or to an accountant in any of the businesses that are related to the dissemination of music, that they make yet another recording of a Mozart symphony or Beethoven symphony or some fragments from Wagner because they have already in their hands ‘saleable’ names. They’re not interested in the concept of building names to the point where they in turn will become saleable items, if you want to put it that way. They’re not interested in funding the music. They’re not interested in making it possible for this music to become popular by being heard. Let’s face it, not all modern music is harsh or hard to listen to. Not all of it is like that. There’s a lot of very, very accessible music written by composers that either lived not too recently, or who are still alive.

BD: Do you want the situation to change to where Hale Smith becomes a household word?

HS: I’m not particularly interested in being a household word. I wouldn’t mind the money, but the problem that comes with that is that one in turn has an obligation to live up to the image. I don’t want to become another Andy Warhol. I saw a picture of him yesterday in one of the New Orleans newspapers standing in front of one of his brand new works in that little town in Italy where The Last Supper is being refurbished. Warhol has his The Last Supper in a building across from that little chapel, and the thing that struck me was that in Warhol’s he had a part of Da Vinci’s painting upside down. I think Dali was a far greater painter than Warhol could ever dream of starting to be, and he destroyed himself in terms of becoming the essence of his image. That’s one of the dangers in that type of thing. I’m not interested being a household word except in certain circles. I want to be deserving of being respected by the people that I respect, and that includes the listener.

* * * * *

BD: When you’re writing a piece of music, for whom are you writing?

HS: I don’t think any serious musician, or composer, or creator is ever writing for anyone but himself. He has an external purpose. For instance, if I were to write a piece for you and you were going to play it, then I have to take certain things into consideration. That’s only being professional. But first, if it doesn’t satisfy me I don’t care what you think about it! And if it does satisfy me, I still don’t care! [Both laugh] It has to be that way I believe.

BD: Have you basically been pleased with the performances you’ve heard of your music?

HS: I’ve had some good ones and I’ve had some disasters. Most of them have been pretty good. I’m not the type of composer that gets excited if everything isn’t perfect. I get upset if the commitment to the piece, or just to the art of music, is not there. I prefer having flawless performances; I very definitely would prefer that, because I know if it’s flawless, that’s what I have in my ear. Usually that doesn’t happen, but I also have the experience of really dedicated people playing music of mine, who for some reason or other couldn’t pull everything off. But the commitment was so strong there that the music worked anyhow, and I would satisfy myself with that.

BD: Are most of your pieces written on commission, or are there some things that you just say, so you have to write them and hope that they get published?

HS: Fortunately, for a very long time I have not had to worry about publishing or publication. I’ve been very lucky in that way. Usually I have so many things to do that I don’t just sit down and write a piece like that. Rather, I just block out a certain period of time just to be writing, and it is something I find very difficult to do. Besides, I don’t mind being professional. The great masters of the past were paid for what they did... Schubert was an exception. He didn’t understand the market place, but for the most part they got paid in one way or the other. Usually there was enough to support them.

BD: So then you feel it’s important for even a creative artist to understand the market place?

HS: I think so. Samuel Johnson made a very good point. I can’t quote him exactly, but he did say something to the effect that if one must write, one must write, but one is a fool to write except for money. Maybe one can’t carry that quite to such an extent, especially if he’s writing music. If he’s writing words, that’s a little different. Words seem to get a little more play by the conglomerates who are even taking care of that these days.

BD: If you have a lot of commissions, how do you decide which commissions you will accept and which you will decline?

HS: I’ve never had that many at one time that I have to make that choice, not on that ground. But I will accept a commission if there is a serious amount of money involved, and if it’s clearly understood that the commissioning money is mine. The expenses for preparing the materials, copying parts and so on, comes extra. That is not to be taken out of my commission. I will be satisfied with that if, in addition, the commissioning party and I come to an agreement on duration, and the type of forces for which I am to write — whether it’s a chamber group, a solo piece, or full orchestra, or whether it’s for students, or whether it’s for amateurs, or full-fledged professional players, all of that. It’s something the commissioner has a right to impose, but what I write and how I write it is MY business. And when I write it, I own the rights, and that is clearly covered in the copyright law of the United States. So if they have got enough money and they buy that other stuff, I write the piece. I think it’s reasonable that way.

BD: You’ve got to be protecting yourself and your own interests.

HS: Yes. When people commission music, that’s a different proposition from buying music. If you want to ‘buy’ a piece of something written for hire, and the writer is good enough to go along with that program, then you as the buyer own the music. You own the rights to it because that person will have sold his rights to you. A true commission gives you the privilege of being connected with the creation with the work of art. Now that might be rather tenuous. There are names that are coming down to us in history of people who would not be known except for their connection with composers in that way. In other words, that takes care of ego and the mortality factor and the rest. But one could get the privilege of first performance, and there’s a general range of time where a person might negotiate a kind of exclusivity. If there’s enough money, you might say you’d like to have exclusive rights to the performance for a year. Fair enough. A year’s a good time if the money is enough to make it worth the composer’s while, because even if a composer writes quickly, there is not wastage of energy in the sense that the energy you used to write the piece quickly is exactly the same energy that would be used if the piece took up a longer time. It’s the conversion from one level to another. It’s a basic physical fact, that’s all. I’m not talking about metaphysics here.

BD: Are some compositions not harder to get out than others?

HS: That might have to do with a number of factors, in the sense that it has to do with the amount of energy that would be required in pulling a heavy weight up by attaching it to a rope that would go through a number of pulleys. At the other end, the person pulling on the other end of that rope might find it easier to pull that weight up, than to just pull it up by his two hands, but the physical factors, the amount of energy expended is exactly the same.

BD: You’re still going to have the same weight?

HS: Yes, and the energy that’s involved is precisely the same. That’s what I mean.

BD: So the parameters of the commission then determine how much weight each composition is going to be?

HS: Oh, yes, but then again, a very easy-sounding passage to a very easy-sounding piece might be very difficult to write. It might be more difficult to write than something with an all hell-fire and glory! Schoenberg wrote an essay called Heart and Brain in Music (1946) which dealt with that point, and he referred to a passage in Verklärte Nacht. It looks very difficult on paper — there’s multiple counterpoint, a lot of complex little things going on here and there — and he said he tossed it off in no time flat. But there was another passage that looks very easy and looks empty, and it took him days going to work it through. All of us who write know that. We have experienced that.

BD: How do you know when a piece is finished, when you’ve got to quit tinkering with it, when everything is just right?

HS: I don’t know how other people work, but I don’t tinker. I can’t really get much of a head of steam, and I can’t really work very well at a piece until I have a pretty good idea of where it is — its dimensions and its various parameters. I tend to think of composition in sculptural or architectural terms. I equate this block of time with a stone or a space, and the problem then is shaping that time, space, stone in such a way that the piece grows out of it. I keep thinking of the story of this block of Carrara marble that was discarded by a rather renowned local sculptor because its shape was bad. The dimensions didn’t fit his imagination. So along came this other sculptor who looked at it and saw exactly what was in there. He went to work on it, and out came Michelangelo’s David! [Both laugh] According to the story, which I’m inclined to believe, the height of this block of stone exactly matched the height of the finished statue. So I guess it’s the ability to take whatever it is one is dealing with and visualize what fits in it.

BD: So then really instead of putting something into a space, you’re releasing from the space what is already there?

HS: That’s what I think. That’s the way I tend to think of composition. I don’t ‘do’ a piece; I discover the piece, and in doing that, very often I do need to build up a very heavy head of steam to get all kinds of pressure and tension, which is why I say that the best guarantees in me writing are money and a deadline! I need to have some pressure I can’t squeeze away from to really make me go through the labor for sitting down. I’m not like T.J., who just writes! [All laugh] I wish I could do that! He’s always telling me, “Man, just write the piece!” But I consider myself part of the great tradition of Mozart and Rossini. In both cases they tended to put things off till they couldn’t put them off anymore. Very often to break through that, I’ll just sit down and start writing. It’s almost like a blind writing, and I’ll get a certain number of pages or a certain number of measures, whichever comes first, and then I stop and isolate the ideas into the harmonic elements, the rhythmic elements, and the melodic elements. When I isolate them, I write a series of motifs, sections of the melodic material, let’s say, and I’ll break it down and see what is the common motivic material with the same with harmonic structures and rhythms. I isolate them, starting them separately, and I call that my ‘getting acquainted with the biographies of my ideas’. I think that’s what Beethoven was doing in his sketchbooks. Then the time the piece falls in line. There also I do a little work with my stopwatch, and metronome, and my pocket calculator, in measuring, timing this, that, and the other. So by the time I actually start writing, I know it. Once I write it in my head, usually it flows, and I can write rather quickly like that.

* * * * *

BD: I want to go off in a little different direction for the moment. We were talking about Wynton Marsalis. He sort of made it in both camps — the ‘popular’ camp and the ‘serious’ camp.

HS: Now that’s a word that’s verboten for me!

BD: Which word?

HS: ‘Serious’! I hate that word! I use the word ‘formal’. My common statement is that some joker might be standing out there on the corner, right out there playing the Blues, and he’s dead serious.

BD: Is it a mistake, then, for the concert public to draw an artificial line between their music and the music of the guy out on the corner playing the Blues?

HS: I think so, sure. I don’t draw it for myself, except for when I’m writing ‘formal music’ I’m writing ‘formal music’, and when I’m writing jazz or playing jazz, I’m doing that. But the line is a continuum.

BD: Music is music?

Hat! [Both laugh]

D: But you seem to have decided to spend most of your efforts on the formal music side.

HS: No, I live on both sides of that fence every day of my life. I would sit in with Dizzy Gillespie, and I told Billy Taylor, “Say, man, you need a piano player in your group?” All the time I stay on both sides.

BD: [With a sly grin] Would you go up to Sir Georg Solti and ask if he would need a piano player in his group?

HS: [Laughs] Well, he can play pretty well! I’m what I would call an aspiring piano player, but I maintain close ties with jazz world.

BD: Is this, perhaps, what makes a performer like Marsalis so special because he does do both so well?

HS: That’s one of the things, but he’s not the only one by any means. Wynton came along under some very propitious conditions in time, and he was also very, very fortunate in his choice of a father. He really was. Ellis Marsalis is a brilliant musician in my opinion, but Wynton is paying a price for the fame he’s achieved. His case reminds me of a lot of things that used to be said about Heifetz. He was regarded as being The Perfect Violinist, and his technique was just beyond that of anybody else that ever picked up the instrument. The idea of him having a mistuned note was completely beyond the imagination, but many, many people spoke of the cold perfection of his playing. It was cold, but I’m not so sure he was, and that same kind of thing is applied to Wynton. Let me hear some mistakes! Let him fluff some time to show he’s human. He’s also upset a few people — more than a few people — by the broadness of certain statements he’s made. I find him very warm and very nice. I often measure a person by observing that person’s interaction with the lesser of the world, and that includes fans very often. I’ve known too many performers — names of some of them you would know — who act disdainfully towards the public. I’ve never seen that with Wynton. I know of him to going into schools, taking time out with youngsters, and I know several youngsters he has encouraged. In that way he’s like Dizzy, because both of them I’ve seen always encouraging younger players, and taking time out to talk with them and make them feel good. At least one or two of them he’s invited over to his apartment and given some lessons, for that matter.

BD: Do you do the same thing when you encourage young composers?

HS: No, I’m hard on all of them! [Has a hearty laugh] If I see talent, and even more so the fact when I see sincerity, I’ll take the time, of course. I tend to talk too much... like I’m talking too much here! [Both laugh]

* * * * *

HS: The one thing I’m not pleased about is that over the years there’s been so few, and there have been none for quite a while now. Those are other considerations, but in terms of performance there’s nothing that I would really turn my back on. Even though the Louisville recording of my Contours for Orchestra helped to make my name something that at least people interested in American music would have reason to pay attention to is done in a sincere way. It has that type of sincerity that I mentioned before, but I’ve heard performances of it that have a great deal more fire. That particular piece calls for that type of drama. The recording of the Ritual and Incantation done by Paul Freeman with the Detroit Symphony was damaged by decisions made on the recording side, tying in certain sections on the same microphone lines for the balances and so on. So when we got into the mixing studio, certain adjustments couldn’t be made without damaging some other section that was on that same line. I understand this record is coming out on CD, and in fact that whole Black Composers Series from CBS is coming back on CD.

BD: Oh good! It’s been out of the catalogue for a while, so I’m glad to know that it’s coming back.

HS: It’s supposed to. There’s supposed to be two different forms — one that is sponsored by the College Music Society, and I was also given word that there’s going to be a CBS release of it again. Now, of course, that was before Paley took over the reins again, so I don’t know what’s going to go on now! [Both laugh] CBS is a world unto itself. But the ending, the last section of that recording is defective because on the equipment they were using at the time, the ending built up such a dynamic level that it knocked the needles into the danger zone. When I first heard a test pressing, I almost died. When it got to the major climax near the end of the piece, it suddenly dropped. There’s a physiological expression that would cover the effect, which, since this is going to be on radio I won’t mention, but I think you would know what it is! [Both laugh] I objected to that strenuously. There’s a section that starts the so-called Incantational second part of the piece, which opens with a drum roll. They started it at that point and brought the entire thing down to a lower level so there is some approximation of a climax at the end. But the key problem of joining these various sections cannot be solved on that recording. The performance was good. Paul Freeman knew the piece, and in fact he did the first performance of it, and he’s performed it a number of times. So I got admiration there.

BD: Admittedly, a recording should get it right, but how are these technical problems with balances different from, say, a performance in an auditorium where you have one person sitting way over on one side in front of the harps and the violins, and another person sitting way over on the other side by the double basses, and somebody else way at the top of the balcony who can’t hear the inner textures?

HS: A lot of that depends on the hall and the way the piece is actually performed. There are certain concert halls that tend to clarify musical details, while other halls tend to distort them in one way or another. They make certain sections or certain pitch levels muddy, or overly sharp and bright, or whatever. But the other factor here is that we are dealing with a concert hall where sound is being dispersed through the entire space, for better or for worse, depending on the acoustical properties of the room. But when you’re dealing with microphones, you’re talking about certain elements of tone being particularized, isolated, sent into a control board, and then that is manipulateable by an engineer. So we have two different acoustical problems.

BD: Has the concert public become too enamored of the gramophone record?

HS: I can imagine a scene in a concert hall where somebody who is accustomed these recordings of whatever type is looking around frantically saying, “Where’s the bass button? I don’t hear enough bass!”

BD: They want to make their own adjustments!

HS: [Laughing] Today we’ve got a situation where in certain opera halls and concerts halls in the country, singers are miked. To me, that is one of the least understandable things for any kind of group. This happens a lot with popular groups of course, and in a hall like Carnegie, it completely disrupts the natural ambiance in that hall, and they are always having to struggle to get this adjusted and that adjusted, and so on and so on. Then when the mixture’s right, almost invariably they are having it far too loud, so it doesn’t work! I remember an event several years ago at St. Augustine’s College [as it was called in 1987 when this interview was held. Saint Augustine's University is a historically black college located in Raleigh, North Carolina. The college was founded in 1867 by prominent Episcopal clergy for the education of freed slaves.] Ragtime pianist Max Morath and I were there on separate nights, and also one of those nights had one of the Preservation Hall jazz groups. They played in the school gym, and immediately following them was a local group that played. In this Preservation Hall group, the youngest fellow was fifty-nine at the time, and the rest of them were in their sixties and seventies. I think one of them was just about hit eighty. They had to use a beat up upright school piano they had in the gym. This was a gym with a stage in it, and he had one electrical light. But it didn’t matter since they weren’t reading music anyhow. The leader was the trumpet player, and I notice he would stamp his foot once. By that second beat they were coming in and they were all rock solid. It was wonderful the way they kept that time. There was a clarinetist, a trumpet player, a trombone player, a banjo player, the piano player, a bass player, and a drummer. So there were seven people up there in this lousy gym, and I heard everything. Every once in a while one of them would sing, and when this person would get up there and sing there might have been one mike up front, but I don’t remember. But what I do remember is that when the singer got up there, the rest of that band came right down (in volume), and you could hear every word that singer was singing, and you could hear every note that the band was playing. Right after they’d finished, the other group started bringing in their stuff. They had a battery of speakers around the back of the stage! There were some pretty good musicians. A couple of them were teachers down there, and they played jobs at night or as extra players when needed. But when they got through turning those dials, boy, I remember putting my hand up against a brick wall, and that thing vibrated. [Both laugh hysterically] You didn’t hear a thing except noise, and the balances were terrible. I don’t see how musicians can do it. I just get upset about it. My poor head! [Laughs] There is a wonderful old popular song called I’m Old Fashioned, and when it comes down to that, I’m old fashioned. There’s somewhere down the line the music has to come through, and it’s not doing it.

BD: Is the music of Hale Smith wonderful?

HS: Frankly I think so because, as I told you before, the music I write has to meet my criteria, and if I don’t like it, who else should like it? I don’t think I’d want to put up with anything written by somebody who didn’t like their own stuff! Sure! I think I write beautiful music.

BD: Is writing music fun?

HS: Stravinsky said it was! I don’t know whether it’s fun or not. It’s like asking, “Are you a music lover?” I don’t know, except that there’s nothing else that I would put anywhere near it in terms of its effect on me. I like pretty things, beautiful things, and I like to have something to say. Even if I have something to say, if I can at least make it beautiful to me, then I like that. But I like hearing it more than I do putting it down. Maybe that’s why I put it off so much.

* * * * *

BD: Have you written an opera?

HS: It’s a funny thing. I’m listed in some opera guide as having written a chamber opera many years ago. What I did was write what I thought was incidental music for a production of Lorca’s Blood Wedding, and if it’s an opera, it’s a strange one because none of the principals were singers! [Both laugh] So all of the vocal work writing is done for people in the show. It was done for the Campbell Theater in Cleveland many years ago. The interesting thing to me is that in November I had two libretti handed to me within one week. People that had been working on them.

BD: Are you going to set them?

HS: I want to very much, so I’m thinking about them. Right now I’m trying to sort the two. They are so far apart that it’s possible I might even pull a Ravel coup and start writing two operas at one time! [Much laughter] Both of them, for whatever it’s worth, deal with essentially black subject matter, but they transcend those ideas, those conditions. One has very rich and beautiful imagery, and the other is quite stark.

BD: Are they full-length operas?

HS: Yes, they would be full length.

BD: If they were chamber works, maybe you could put them both together.

HS: No, no, these would be full length. In fact, my problem with the lush one is that the librettist was really thinking the impossible! I asked him how many stages in the world he thought could handle this! There’s one point when he has the chief protagonist is going through the theater, dropping down on a rope, trying to get to his seat, and he’s stumbling over people, stepping on shoes and everything. There’s action on the stage; a singer doing something on the stage, and while all that’s going on, he’s singing an aria! Even in the greatest theater in the world it would take you fifteen minutes to get down the theater aisle! [Much laughter during this entire story] That is something we have to work out, but I’m not mentioning names deliberately.

BD: I hope it comes to pass, both these operas.

HS: I wouldn’t mind doing it. Thinking of operas, there are two recent operas T.J. Anderson has done, that are quite remarkable. T.J. has written two of them. [Addressing Anderson, who has been listening to the conversation since his arrival] Have you finished the second one? [The second work would be Walker which would be completed in 1992.]

T.J. Anderson: Just one.

HS: You’ve only just finished the first? Soldier Boy, Soldier. I’ve not seen it. I wasn’t able to get to performances but I did see the score. So he’s done something. Then there was an opera based on the early life of Frederick Douglass by a woman composer, Dorothy Rudd Moore. The one which got the most attention I believe is Anthony Davis’s opera, X, based on Malcom’s life. I think they’re very strong; all three of those scores are quite strong in my opinion. I went to a performance of X that was at the City Center Opera, and during an intermission I went around holding my posterior for, as far as I’m concerned, Anthony Davis kicked a lot of us, and we were pretty tender. He did a beautiful job.

BD: High praise indeed!

HS: Well, yes, I think each of those are very strong pieces. Soldier Boy, Soldier is good, as is the Frederick Douglass work, and of course X, so I’ve got quite a precedent in front of me when I’m thinking of doing mine.

BD: Is opera the way to reach people today?

HS: The way to reach people today is to write rubbish, and be sure that properly placed radio people are paid enough to play it. That’s the way to reach people today.

BD: Then why write opera?

HS: Because it’s there to be done, and there are certain things that need to be expressed that people like us can express. The world — if it lasts — is not going to remain in the hands of the ‘know-nothings’ and ‘the great I ams’. I’m not being prophetic. It’s just that we’re going through a phase and a cycle, I believe, and if we live long enough and come out of it, hopefully there will be enough of our civilization left for really serious interesting beauty. It will have a chance.

BD: I hope we make it.

HS: So do I, I tell you!

BD: Thank you so much for sharing your time with me today.

BD: Is writing music fun?

HS: Stravinsky said it was! I don’t know whether it’s fun or not. It’s like asking, “Are you a music lover?” I don’t know, except that there’s nothing else that I would put anywhere near it in terms of its effect on me. I like pretty things, beautiful things, and I like to have something to say. Even if I have something to say, if I can at least make it beautiful to me, then I like that. But I like hearing it more than I do putting it down. Maybe that’s why I put it off so much.

* * * * *

BD: Have you written an opera?

HS: It’s a funny thing. I’m listed in some opera guide as having written a chamber opera many years ago. What I did was write what I thought was incidental music for a production of Lorca’s Blood Wedding, and if it’s an opera, it’s a strange one because none of the principals were singers! [Both laugh] So all of the vocal work writing is done for people in the show. It was done for the Campbell Theater in Cleveland many years ago. The interesting thing to me is that in November I had two libretti handed to me within one week. People that had been working on them.

BD: Are you going to set them?

HS: I want to very much, so I’m thinking about them. Right now I’m trying to sort the two. They are so far apart that it’s possible I might even pull a Ravel coup and start writing two operas at one time! [Much laughter] Both of them, for whatever it’s worth, deal with essentially black subject matter, but they transcend those ideas, those conditions. One has very rich and beautiful imagery, and the other is quite stark.

BD: Are they full-length operas?

HS: Yes, they would be full length.

BD: If they were chamber works, maybe you could put them both together.

HS: No, no, these would be full length. In fact, my problem with the lush one is that the librettist was really thinking the impossible! I asked him how many stages in the world he thought could handle this! There’s one point when he has the chief protagonist is going through the theater, dropping down on a rope, trying to get to his seat, and he’s stumbling over people, stepping on shoes and everything. There’s action on the stage; a singer doing something on the stage, and while all that’s going on, he’s singing an aria! Even in the greatest theater in the world it would take you fifteen minutes to get down the theater aisle! [Much laughter during this entire story] That is something we have to work out, but I’m not mentioning names deliberately.

BD: I hope it comes to pass, both these operas.

HS: I wouldn’t mind doing it. Thinking of operas, there are two recent operas T.J. Anderson has done, that are quite remarkable. T.J. has written two of them. [Addressing Anderson, who has been listening to the conversation since his arrival] Have you finished the second one? [The second work would be Walker which would be completed in 1992.]

T.J. Anderson: Just one.

HS: You’ve only just finished the first? Soldier Boy, Soldier. I’ve not seen it. I wasn’t able to get to performances but I did see the score. So he’s done something. Then there was an opera based on the early life of Frederick Douglass by a woman composer, Dorothy Rudd Moore. The one which got the most attention I believe is Anthony Davis’s opera, X, based on Malcom’s life. I think they’re very strong; all three of those scores are quite strong in my opinion. I went to a performance of X that was at the City Center Opera, and during an intermission I went around holding my posterior for, as far as I’m concerned, Anthony Davis kicked a lot of us, and we were pretty tender. He did a beautiful job.

BD: High praise indeed!

HS: Well, yes, I think each of those are very strong pieces. Soldier Boy, Soldier is good, as is the Frederick Douglass work, and of course X, so I’ve got quite a precedent in front of me when I’m thinking of doing mine.

BD: Is opera the way to reach people today?

HS: The way to reach people today is to write rubbish, and be sure that properly placed radio people are paid enough to play it. That’s the way to reach people today.

BD: Then why write opera?

HS: Because it’s there to be done, and there are certain things that need to be expressed that people like us can express. The world — if it lasts — is not going to remain in the hands of the ‘know-nothings’ and ‘the great I ams’. I’m not being prophetic. It’s just that we’re going through a phase and a cycle, I believe, and if we live long enough and come out of it, hopefully there will be enough of our civilization left for really serious interesting beauty. It will have a chance.

BD: I hope we make it.

HS: So do I, I tell you!

BD: Thank you so much for sharing your time with me today.

HS: Well, maybe I shouldn’t have gotten so vociferous.

BD: No, no, this was fine! [Looking at T.J. Anderson] Can I impose on you to change seats and let me talk with you?

HS: This guy upstages me so often. [Laughter all around]

TJA: Oh, no, never. He is my teacher. How can you upstage your teacher! [Much laughter]

HS: Do you want me to tell you something about him?

TJA: [Feigning a protest] No, no, no! [All laugh]

HS: He’s one of our privileged composers. For years he was head of music at Tufts University until he stepped down, and he’s still at Tufts. He is one of our most eminent educators. Before that he spent some time in Atlanta as composer-in-residence for the Atlanta Symphony with Robert Shaw, and he is one of the most articulate and pungent speakers.

Hale Smith

Hale Smith (June 29, 1925 – November 24, 2009) was an American composer, pianist, educator, arranger, and editor.[1]

Biography