SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2019

VOLUME EIGHT NUMBER ONE

HERBIE HANCOCK

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

MELBA LISTON

(November 30-December 6)

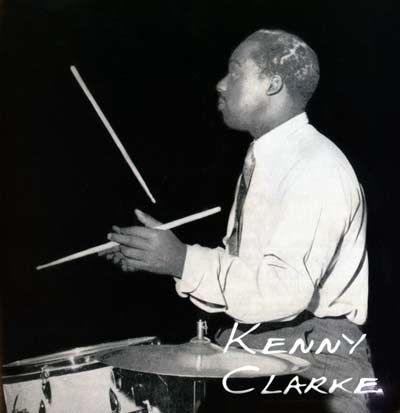

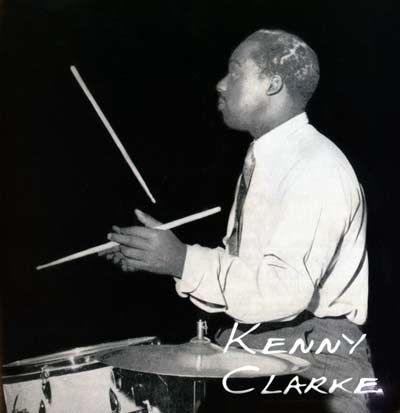

KENNY CLARKE

(December 7-13)

LEONTYNE PRICE

(December 14-20)

JIMMY LYONS

(December 21-27)

PATRICE RUSHEN

(December 28-January 3)

ELVIN JONES

(January 4-10)

GARY BARTZ

(January 11-17)

HALE SMITH

(January 18-24)

BENNY CARTER

(January 25-31)

BENNY GOLSON

(February 1-7)

BENNY BAILEY

(February 8-14)

SKIP JAMES

(February 15-21)

A key influence on the rhythmic development of bebop, drummer played with icons in the 1940s, formed legendary Modern Jazz Quartet.

Kenny Clarke

(1914-1985)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Kenny Clarke

was a highly influential if subtle drummer who helped to define bebop

drumming. He was the first to shift the time-keeping rhythm from the

bass drum to the ride cymbal, an innovation that has been copied and

utilized by a countless number of drummers since the early '40s.

Clarke played vibes, piano and trombone in addition to drums while in school. After stints with Roy Eldridge (1935) and the Jeter-Pillars band, Clarke joined Edgar Hayes' Big Band (1937-38). He made his recording debut with Hayes (which is available on a Classics CD) and showed that he was one of the most swinging drummers of the era. A European tour with Hayes gave Clarke an opportunity to lead his own session, but doubling on vibes was a definite mistake! Stints with the orchestras of Claude Hopkins (1939) and Teddy Hill (1940-41) followed and then Clarke led the house band at Minton's Playhouse (which also included Thelonious Monk). The legendary after-hours sessions led to the formation of bop and it was during this time that Clarke modernized his style and received the nickname "Klook-Mop" (later shortened to "Klook") due to the irregular "bombs" he would play behind soloists. A flexible drummer, Clarke was still able to uplift the more traditional orchestras of Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald (1941) and the combos of Benny Carter (1941-42), Red Allen and Coleman Hawkins; he also recorded with Sidney Bechet. However after spending time in the military, Clarke stayed in the bop field, working with Dizzy Gillespie's big band and leading his own modern sessions; he co-wrote "Epistrophy" with Monk and "Salt Peanuts" with Gillespie. Clarke spent the late '40s in Europe, was with Billy Eckstine in the U.S. in 1951 and became an original member of the Modern Jazz Quartet (1951-55). However he felt confined by the music and quit the MJQ to freelance, performing on an enormous amount of records during 1955-56.

In 1956 Clarke moved to France where he did studio work, was hired by touring American all-stars and played with Bud Powell and Oscar Pettiford in a trio called the Three Bosses (1959-60). Clarke was co-leader with Francy Boland of a legendary all-star big band (1961-72), one that had Kenny Clarke playing second drums! Other than a few short visits home, Kenny Clarke worked in France for the remainder of his life and was a major figure on the European jazz scene.

https://www.moderndrummer.com/article/february-1984-kenny-clarke-jazz-pioneer/

Features

Clarke played vibes, piano and trombone in addition to drums while in school. After stints with Roy Eldridge (1935) and the Jeter-Pillars band, Clarke joined Edgar Hayes' Big Band (1937-38). He made his recording debut with Hayes (which is available on a Classics CD) and showed that he was one of the most swinging drummers of the era. A European tour with Hayes gave Clarke an opportunity to lead his own session, but doubling on vibes was a definite mistake! Stints with the orchestras of Claude Hopkins (1939) and Teddy Hill (1940-41) followed and then Clarke led the house band at Minton's Playhouse (which also included Thelonious Monk). The legendary after-hours sessions led to the formation of bop and it was during this time that Clarke modernized his style and received the nickname "Klook-Mop" (later shortened to "Klook") due to the irregular "bombs" he would play behind soloists. A flexible drummer, Clarke was still able to uplift the more traditional orchestras of Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald (1941) and the combos of Benny Carter (1941-42), Red Allen and Coleman Hawkins; he also recorded with Sidney Bechet. However after spending time in the military, Clarke stayed in the bop field, working with Dizzy Gillespie's big band and leading his own modern sessions; he co-wrote "Epistrophy" with Monk and "Salt Peanuts" with Gillespie. Clarke spent the late '40s in Europe, was with Billy Eckstine in the U.S. in 1951 and became an original member of the Modern Jazz Quartet (1951-55). However he felt confined by the music and quit the MJQ to freelance, performing on an enormous amount of records during 1955-56.

In 1956 Clarke moved to France where he did studio work, was hired by touring American all-stars and played with Bud Powell and Oscar Pettiford in a trio called the Three Bosses (1959-60). Clarke was co-leader with Francy Boland of a legendary all-star big band (1961-72), one that had Kenny Clarke playing second drums! Other than a few short visits home, Kenny Clarke worked in France for the remainder of his life and was a major figure on the European jazz scene.

https://www.moderndrummer.com/article/february-1984-kenny-clarke-jazz-pioneer/

Features

Kenny Clarke — Jazz Pioneer

It’s understandably difficult for a young drummer to imagine that the various components of the drumset were ever utilized in a manner unlike the way they are today. In actuality, the approach was, at one time, considerably different, and Kenny Clarke had a whole lot to do with changing it all. His drumming led the way towards usage of the bass drum for accentuation as well as timekeeping; the establishment of a jazz-time rhythm for the ride cymbal, and freedom from a strictly metronomic role, forcing the bassist to share in the responsibility of timekeeping.

Kenny Clarke can also be credited with freeing the left hand so it could interact with the soloist—the obvious reason why thousands of young student drummers still sweat over Jim Chapin’s Advanced Techniques For The Modern Drummer, a classic text which captured the elements of “bop-style” drumming and documented it for us all. Most importantly, Kenny Clarke is primarily responsible for giving jazz drummers an opportunity to fully express themselves on the instrument, and un leashing the chains that bound them up to that point.

Born in Pittsburgh in 1914, Kenneth Spearman “Klook” Clarke began his career as a swing band drummer, enjoying a moderate degree of success with the likes of Roy Eldridge, Claude Hopkins, and The Edgar Hayes Orchestra. However, dissatisfied with the relentless press roll, and four-to-the-bar bass drum style so prevalent at the time, Clarke began to venture off in new directions, often losing gigs as a result of these daring rhythmic experiments. That is, until 1940, when he took his jazz drumming concepts to a place called Minton’s, a smoky little club on 118th Street in New York City. The rest is history, for it was here that the new style of drumming began to mesh with the musical ideas of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Thelonius Monk and Charlie “Yardbird” Parker in the formation of a new music soon to become known as “bebop. “It was a drumming style which would have an immediate impact on people like Max Roach, Art Blakey, Tiny Kahn, Stan Levy and Shelly Manne, a group of young drummers who would ultimately take the style to even greater heights.

To say that Kenny Clarke was “important,” or “influential,” or even “a key musical figure,” does not do his contribution justice. To state, unequivocally, that he was drumming’s all-time Great Emancipator, a man to whom every jazz drummer who’s ever lived owes a debt of gratitude, is perhaps a much more honest appraisal.

ET: I’d be interested to find out how you started. Did you start on drums?

KC: Well, not really. My father played trombone and my brother was also a musician. I was in a school where they had all kinds of instruments. We had a little parade band, and we used to parade all the time, sometimes for the Masons if they wanted a band. I actually started on peck horn. That was the easiest way, you know. Then I started playing the baritone horn, which was a little bigger, and then the trumpet. My mother also started me on piano and she taught me how to read music. She really instilled a love of music in me. In high school, I studied piano, trombone, vibes, theory and finally drums. I was working gigs in and around Pittsburgh as a drummer when I was in my teens. After I finished high school, I started hanging out with all the people who were in bands, and learning to improvise and spread out a little bit.

ET: What happened after that?

KC: I went to Cincinnati. We had a very hip band with Leroy Bradley. The young cats were so hip in that band. We were using stock arrangements, but sometimes we would invent things. I also worked the Cotton Club in Cincinnati and played all the shows.

ET: You once mentioned that, in order to play shows in those days, you had to play all the percussion instruments. Drummers really had to be percussionists in order to get work.

KC: Oh yeah, sure. And bass players had tubas; a big tuba sitting right on the stand. I had vibes; I always had vibes.

Anyway, on the weekends, all of the great big bands would come in: Duke, Don Redmond, Earl “Fatha” Hines. And that’s where I got to meet all of the great musicians of the day. After that I worked for a short while with Roy Eldridge. Roy was really chief of the trumpets at that time, you know. He could blow everybody out. Man, he was fantastic.

When I came to New York, I started working in the Village with some small groups, and then I got the opportunity to go to Europe with the Edgar Hayes band. We toured Finland and Sweden—all over—and I made my first recording with that band.

After the tour, I moved on to work with Claude Hopkins and then Teddy Hill. I worked at the Savoy with Teddy’s band, and that was great because that’s when I first got the chance to work with Dizzy. Diz had already been with the band in Paris and that’s when I first heard him.

ET: Who do you remember as being your very earliest drumming influences?

KC: Well, there weren’t that many really good drummers then. There was a guy named “Honeyboy” who did all kinds of tricks and stuff, but he wouldn’t settle down and keep the thing together. He’d be playing and singing, and sparks would be flying. He was a fantastic showman.

But there was one cat who taught me everything about cymbal playing. His name was Jimmy Peck. He was a pilot and he had fought in the Spanish-American War. Later he became one of the directing engineers at Bell Aircraft in Philadelphia. He was mean, baby—a smart player.

Of course, there was Baby Dodds, and though I had heard about him, I never got a chance to see him because he never came to my town. Anyway, I never liked that style of playing; that heavy, rolling type of drumming. It took too much time. I didn’t like it, but I played it to get into the clique. But through all of it, I was always thinking, there must be another way, you know. To “dig coal” all night long, man, you got so tired that you couldn’t pick up your bag the next morning. I used to say, “There must be an easier, simpler way to get the same effect and keep the band together without straining your arms.” I thought about it for many years. I was still basically playing the old way, but every once in a while I’d go up there and do that cymbal thing. Ding-ding-a-ding. The other guys would say, “What are you doin’, man? Get back on the snare drum.”

ET: You were actually moving the time feeling up to the cymbal.

KC: Yeah, yeah. I figured you could hear it better than on the snare drum. “Diggin” coal” would cover it all up.

ET: You once mentioned that you were quite tuned in to melody and harmony, and it seemed as though you wanted to complement that more.

KC: Sure. A lot of people said, “Klook, when you play drums, it sounds like a melody.” Well, that’s just what I was trying to do. When they’d say, “Take a solo,” I’d just hum “Sweet Sue” and keep on playing. And it would always come out right. They all knew when I’d taken a chorus. You knew when the 32 bars were up. That was my little trick for solos.

ET: After you got to New York, and you were playing with swing bands more, I imagine it was acceptable to be playing that ride rhythm on the cymbal, right?

KC: No, not in a big, organized band. They didn’t go for it even up to 1937 or 38. When I went to Europe with Edgar Hayes, I was playing a mixture.

ET: But it was still mostly on the snare drum?

KC: Yeah, and I’d say, “Oh man, I gotta do something to drive out the monotony.” Some guys would say, “Yeah man, pretty hip.” I’d say, “Look man, I can’t dig coal all night. I gotta do something.” So I’d play the figures with the brass, but then I’d have to start diggin’ that coal again. I was always trying to get away from that.

ET: Those press rolls?

KC: Yeah. You see, we didn’t really have a ride rhythm. I was trying to perfect that. I figured if I could perfect it, it would be a feather in my cap.

ET: When did the ride rhythm finally become more or less acceptable?

KC: It wasn’t accepted until we went up to Minton’s in 1940. I had gotten everything I was trying to do together by that time and my style was pretty well set.

ET: Tell me about the scene at Minton’s during those great days.

KC: Oh man, those were the days. When Teddy Hill became the manager at Minton’s, he turned the whole back room over to the musicians, and we could pretty much do as we pleased. I organized the first house band for the place with Monk, and Joe Guy on trumpet. All the great musicians in town would show up to sit in. That’s where the bebop movement was born. Teddy never told us what to play, or how to play. We just played whatever we felt. Work was pretty scarce at that time, so Teddy just wanted to do something for the guys who had worked for him.

Cats used to come from all over to listen to what we were doing and to sit in. Musicians from all over the country—Dizzy, Hot Lips Page, Georgie Auld, Roy Eldridge, and even Lester Young—would come around a lot. Lester loved what we were doing. All the musicians from whatever bands were working in town would come up after work. Jimmy Blanton, Duke’s bass player, was always dropping in. There was a lot of sitting in.

ET: I’d be interested to hear what you recall about some of the pioneers of the movement who would come up to Minton’s to sit in, like Charlie Christian, for example.

KC: Charlie was a very quiet, very reserved little guy, and we used to really look forward to him coming up. He usually came in every night after he finished working downtown with Benny Goodman. Charlie talked about the place and what we were doing so much that even Benny came up once in a while. He sat in too.

Charlie contributed a tremendous amount to the new music and we were always swinging hard when he came up. He wrote some really great tunes as well. At the time, we didn’t even have a name for the music we were playing. It wasn’t even called “bebop” at that time. We just called it modern music.

ET: Dizzy?

KC: Diz was the most advanced of all of them as far as harmonies and rhythms went—very progressive. Roy Eldridge and Diz would always have these cutting contests, and at the time, Roy was always the favorite. People understood what he was doing more. But as time went on, the musicians started to catch on to what it was Diz was doing, and after a while, everybody kind of forgot about Roy. Then Diz became the trumpet player at Minton’s. But Roy never stopped coming up, though he never really did change his style. I owe a lot to Roy actually, because he always encouraged me when I was working out my ideas for a new style of drumming.

ET: Tadd Dameron?

KC: Tadd really impressed all of us. He was using flatted fifths in chords back as early as 1940, and though it sounded very odd to us at first, he was definitely a forerunner of the movement. He was also one of the first people to play full, 8th-note patterns in that real legato style.

ET: Charlie Parker?

KC: Bird first came to New York with Jay McShann’s band. He was working at a place called Monroe’s. The sessions were always either at Monroe’s or Minton’s. Well, Monroe’s used to open up after Minton’s closed, about four in the morning. So, we’d leave Minton’s and then go there.

We first went to hear Charlie at Monroe’s because the word was out that he sounded like Pres. Actually, Pres was the pacesetter at the time, so everyone was really interested to see what this young cat named Charlie Parker was doing with the music. Well, when we first heard him, we realized that this was a man with a whole lot more to offer. He’d play things that no one ever heard before—incredible stuff.

Bird was a very, very quiet guy. He was not talkative at all. He’d never talked much about what he was doing with the music. He’d just get up there and do it. I don’t think he ever realized himself the changes he was bringing about.

ET: What about the drummers who would come in?

KC: Well, when I was at Minton’s, nobody had really caught on to what I was doing with the instrument. I remember Sid Catlett came up one night, and he listened and listened. Finally he said, “Are you still playing the bass?” I said, “Yeah, but I make the accents off the four beats.” I couldn’t give that up and play with no bass drum. The accent wouldn’t have come in right.

Big Sid said, “Yeah, that’s it.” I looked around, and he and Jo Jones were both playing like that. Of course, Jo was a hi-hat man. But, I couldn’t make that hi-hat thing. I wanted my arms free.

ET: So you moved over to the ride cymbal.

KC: Yeah, I just moved over from the hi-hat to the ride and played the same thing that I’d been playing on the hi-hat. The hi-hat then became another instrument I could play with my left hand. It opened up the whole set, you know.

Before that, cats didn’t use the cymbal except for accents, endings and stuff like that. I wanted to use it all the time. But, I was always getting fired. I knew after the first night that I was out, so I would just pack up and move out. The boss would come over and say, “Look, we’ve got to get another drummer for tomorrow night.” And I’d say, “Okay man, I was just leaving. I’ve got my stuff packed.” And I’d split.

ET: But you persevered, which is what an innovator has to do.

KC: Oh, I did believe I was on the right track; that what I was doing was right. If nobody else liked it, the hell with them. I’d just keep playing like that anyway.

ET: Well, fortunately, not everyone closed their ears to what you were doing.

KC: No. They used to come to Minton’s. I’d look out there and it would be all drummers. Art Blakey used to hang out there a lot and he got the style down real good. And Max too.

But it took a long time to figure out what to do with my left hand. A lot of cats helped me. They saw it was a usable style coming into action. Jim Chapin, cats like that, would hang around all the time. He’d never leave me to see what I was doing with my left hand. And, of course, he wrote the book on it. He wrote down all the stuff we did. But I didn’t care. As long as it got to the cats, I was happy.

ET: Your whole approach has always been from the standpoint of playing the drums as a musical instrument.

KC: Yeah, it was to integrate them into the music. I thought that approach would give the soloists more freedom, rather than fencing them in with, “boom, boom, boom, boom.”

Actually, the bottom never changed. I just put it up on the cymbal to kind of ease the weight of the bass drum which I played very softly. It was always four beats, but I would syncopate the bass drum. Whatever accent the band was playing, I would make it, but they could always feel it. I’d just say to the guys, “Put the time in your head and play. Don’t listen for the drums because the drums are not working for you. They’re working for everybody.” The best thing to do was to feel the beat and not listen for it, you know. Once they got it in their heads, then I went upstairs to stay. I played ding-ding-a-ding up there and it gave my left hand freedom to do other things.

It was another way to play. I wasn’t try ing to be hip, but I wanted to make it easier than diggin’ coal all night. I was just figuring it out for me.

ET: What other bands were you able to work with prior to the bebop era?

KC: Claude Hopkins, Teddy Hill. Hill was just beginning to accept my style of playing. But they all still wanted to hear the bass drum. They’d stop playing if they didn’t and there would be all kinds of confusion. I’d say, “Why don’t you just feel it the way I want to play?” They’d say, “No man, we have to know where the beat is.”

ET: What about the bass players?

KC: Most of them were slap bass players until Jimmy Blanton came on with Duke. Sonny Greer’s drumming was mostly for color, more or less. Jimmy carried the pulse. That was his job.

When I started playing up on the cymbal, the bass players would say, “Man, when I hear that bass drum going all the time, I can’t concentrate on my solo. Just play that cymbal.” So I started playing the bass drum real soft and just making accents. The four beats were there, but it was real soft. I still play like that today.

When I played with Oscar Pettiford, I would be in the background going ding-ding-a-ding with a real soft bass drum, and he’d get out in front of that mic’ and shine. He’d say, “Man, just keep that rhythm on the cymbal and that soft bass drum, and everything will be cool.” So I began to practice with just a cymbal—no bass drum. I just played from hand to hand. Oscar would say, “That’s it. That’s what I want!” I had to work with him all the time because no other drummer played like that. Then I started playing it with the big bands. The cats would say, “Yeah man, that’s hip.” I remember one time with Mingus’ band, I sat down and started to play. The whole reed section stood up and said, “Yeah!” So I figured I was on the right track.

ET: Years ago, when I first saw you, you used a big, thick felt beater.

KC: Well, that’s because I was trying to play very soft. I knew if I played soft, I could just say “Boom,” and it would be loud. I didn’t have to go too far to play loud. But if I played, “BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM,” there wouldn’t be any accents. The accents would have to be louder and that would mess up the whole band. I’d play soft for the most part, and the accents would come out better.

ET: Your time beat was almost like a straight four, but it wasn’t. It was right on top, almost like a 64th note, or closer, on the second and fourth triplet.

KC: Well, this cat I was telling you about, named Jimmy Peck, he just sat me down and said, “Look, if you’re going to play it up there, make it sound pretty. It’s all in here, in the wrist, and you kind of throw it out.” When you throw it out, it changes the sound. There are so many things you can do when you get the idea.

Actually, a guy named Joe Garland, a tenor player with Edgar Hayes, would write things for me. He’d write out a trumpet part, and he’d leave it up to me to play whatever I felt would be most effective. I’d play the figures over the regular beat. That’s how I first got the idea to play that way. Then I developed the idea further with Roy. Most of the guys who’d played with Roy didn’t do anything with their left hands. Almost everybody was just copying Jo with that hi-hat thing. I was looking for something new. When I started to play that way, the guys in the band would always kid me about not playing the hi-hat like Jo, but I didn’t want to copy anyone. I wanted to be an original.

ET: Could you trace your career after the Minton’s years?

KC: Well, I went on to work with Louie Armstrong, and then Ella Fitzgerald’s band. I spent a year with Benny Carter in 1942, and then I worked with Henry “Red” Allen in Chicago. I came back to New York right after that and went into the Army in 1943. I was in Europe during the war.

When I came out in ’46, I was a little fed up with the music business and I was actually considering doing something else, but that idea didn’t last very long. I went with Dizzy’s band later in ’46 and stayed for a year before joining Tadd Dameron’s band. I went back with Diz in ’48 for a tour of Europe, and I stayed on in Paris after the tour to do some teaching and recording. Then I came back to the United States in ’51 to tour with Billy Eckstine.

ET: Just to backtrack for a moment, didn’t you once spend some time with the great composer, Darius Milhaud, in Paris?

KC: Oh yeah. That was in 1949. A trumpet player by the name of Dick Collins was living in Paris and he was a student of Milhaud. He told him about me and Milhaud wanted to meet me. Well, Dick and I played for him, and he was taking notes. He’d stop us and take notes. Then we’d play again and he’d stop us again. He was very interested in the ride cymbal beat and in what I was doing with my left hand. He really knew a lot about jazz and he was very enthusiastic.

KC: We did that in 1952. That was with John Lewis and Milt Jackson. That was some quartet; made a hell of a racket. It was so beautiful, you know. And Bags, he could hear around the corner. He had the power to do anything he wanted to do.

ET: Before you moved to Paris permanently in 1956, you did a lot of recording in New York.

KC: I did most of the work for Savoy, and I also worked as an A & R man for them. We recorded people like Cannonball, Donald Byrd, Lee Konitz and Lennie Tristano.

I went to Paris in ’56 to work with this big band over there. The band eventually broke up, but I stayed on in Paris. I did some work with Quincy Jones and I worked at this club in a rhythm section that backed up most of the great American jazz players that came through. I also did a lot of studio work. I liked it better over there. It was a peaceful life, and I could always work. I’d always say, “I’m gonna go back home,” but I never got around to it.

ET: In 1960, you were co-leader of the Clarke-Boland Big Band, until it disbanded in ’73. How did that come about?

KC: Oh, that was weird. We started out with a duo—piano and drums—just Francy [Boland] and me. Gigi Gryce had an ice cream parlour in Cologne, and he would clear the tables in one part of the place so Francy and I could play. Then, Jimmy Wood came in, and he looked up and didn’t see any bass. So he went out and got his bass. Then we had a trio. And that’s the way it went. The band just kept growing and growing.

Then some cat from Blue Note came over and we recorded it. We were eight pieces at the time. Well, the record sold so well that we decided to make another one with 13 pieces. We added the saxes and we started recording again. Gigi would record everything when we got together. We did the Jazz Is Universal album with 13 pieces, and it turned out pretty fair.

ET: That was an international band, wasn’t it?

KC: Oh, yeah. We just picked cats up from everywhere.

ET: You had two drummers there for a while; you and Kenny Clare.

KC: Well, what happened there was, I had an engagement in Morocco for the Moroccan Red Cross, and I had booked it months in advance. Gigi had a transcription date in Cologne, so Ronnie Scott said, “I’ve got a good drummer to bring in. He can fill in for Klook.” So they brought in Kenny Clare. When I got back from Morocco, they played the tapes for me and I said, “When did I do that? I don’t remember doing that.” It sounded like me all through the thing; sounded like everything I did. They said, “Kenny Clare did that while you were away.” I said, “Who is this guy? Bring him over.” There was no use in him being over there and me being here when we played alike. So we brought him to Cologne and tried a couple of tunes. He would always follow me. He’d say, “Klook, you’re the leader.” When I’d take sticks, he’d take brushes. He didn’t want to get in the way.

ET: He’s very simpatico, isn’t he?

KC: He’s a great drummer—a fantastic player.

ET: It’s very difficult to get two drummers synchronized properly in one band.

KC: Well, we started getting things together, you know. We’d play different patterns, because if we both played them, it would be too pronounced. But we figured out the patterns and it worked out.

ET: I’d like to touch on your activity in education for a moment. I have the original series of books that you and Dante Augustini collaborated on. Both of you worked seven years on developing the Dante Augustini Methods, didn’t you?

KC: Yeah. I had the ideas and he had the bread. He paid for everything. He was very quick with transcribing. He could write almost as fast as you could play. Then we’d go over it and see if everything was correct. He had all these connections and a printer. He knew everybody, so he took care of all that.

ET: You know, I’m still working with these things. It’s such a wealth of stuff.

KC: Unlike most syncopation studies, everything swings so hard; there’s so much stuff that just swings. We even had the things we worked out with drumset choirs.

ET: I’ve written some suites off some of the things you’ve done in those books with five or six drummers. I understand that he had things with up to 15 drummers.

KC: Yeah. We’d check out the best students— the hippest students. Dante would be on one side and I’d be on the other to kind of keep things together. It was beautiful, man.

Some cat from television caught wind of it, and he called to ask if we would do something on one of the big shows. So, we picked out the best students who could really make it, and we did a hell of a TV show. People were asking, “When are those drummers coming back?”

ET: Well the things are so musical. It’s amazing what you can do with drums; the limitless possibilities. What’s your feeling on technique as it relates to musicality?

KC: I always tell people, don’t slough off the technique. I mean, it’s important, but only when you need it. You don’t really need a whole lot of technique to play drums. As far as soloing goes, if you hum the melody, the solo will come to you automatically.

You have to learn how to use your technique and how to apply it to the music. It’s like those people who walk into a million dollars. Okay, you’ve got a million dollars. Now, your next problem is you have to learn how to spend it wisely. It’s the same thing in music. You’ve got this technique, but you have to learn how to use it in places where it’s going to sound beautiful. You don’t just put it anywhere. You pick your spots.

ET: That takes a great deal of discipline.

KC: Yeah, that’s right. But if you get the stuff down to where you play it at the right time, then it comes out beautiful. But, if you mix it in with everything, the people get tired of listening to it. It’s not supposed to be like that. My idea of a drum solo is that you play like you sing. It comes from different things you listen to. And the beauty is always in the simple things.

I see young musicians with all kinds of equipment up there who hardly know how to play half of it. If you’re going to take all the stuff, then learn how to use it all. I never used more than two cymbals throughout my entire career.

Most young drummers I hear play too much. I say, just play what’s required of you; whatever’s necessary for that piece of music. Don’t overdo it. You have to be sensitive to the situation you’re in at the moment. If you really know your instrument, you can fit in with anybody.

ET: What’s your feeling about how the drums have evolved over the past 40 years or so?

KC: Well, the innovators always change the direction. Jo, Max, then Elvin, and then Tony Williams turned everything completely around. Now Jack DeJohnette is going on even further.

If you can reach a point where you can say, “Yeah, I found it,” then you’ll be able to show someone what you’re doing. You have to come to some conclusion. It’s like writing a piece of music. It has to have an ending. You can write a million pages, but it has to come to a conclusion. At some point, you have to say, “Well, this is what I’ve reached; this is my conclusion.” Then somebody can take it out and say, “Okay, let’s look over it.” Not that you’re running back every ten minutes saying, “Yeah, but I got this too.” No man, this is what you’ve contributed. Now give us a chance to study it and figure it out. Then you can go on further with it, because now we know what you’re doing.

You have to bring it all together, make one thing out of it, and come to some con clusions about what this is supposed to do and what that’s supposed to do. Don’t just wander out in the fields, searching and searching. Put it all together and draw some conclusions. You put it all in the sack and go on to work, you know. But, if the cats keep “jig-jagging” around, they will never get to the idea of why they’re doing it.

My idea was to make drumming easier for me. I didn’t like the way other drummers were playing. I wanted to be able to say, “Look, this is the way I play. Here it is.” I had to get it down to fine points, and it took a lot of work. I wanted something I could use all the time, no matter where I was, so I could do my gig. That’s what I was working on—something for me—something conclusive.

https://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2014/01/08/260769892/the-drummer-who-invented-jazzs-basic-beat

The Drummer Who Invented Jazz's Basic Beat

Kenny Clarke performs at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1968. He spent the second half of his career in Europe.

JazzSign/Lebrecht Music & Arts/Corbis

https://www.npr.org/2014/01/09/261051016/kenny-clarke-inventor-of-modern-jazz-drumming-at-100

Kenny Clarke, Inventor Of Modern Jazz Drumming, At 100

Kenny Clarke in 1971

January 9, 2014 marks the 100th birthday of drummer Kenny Clarke. One of the

founders of bebop, Clarke is less well-known than allies like Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk, but his influence is just as deep.

That

thing that jazz drummers do — that ching-chinga-ching beat on the ride

cymbal, like sleigh bells? It gives the music a light, airy, driving

pulse. Clarke came up with that, and that springy shimmer came to

epitomize swinging itself.

Before him, jazz drummers kept time

lightly on the bass drum. Kenny Clarke used bass drum sparingly, often

tethered to his snare, for dramatic accents in odd places — what jazz

folk call "dropping bombs." He drew on his playing for stage shows,

where drummers punctuate the action with split-second timing. Clarke

kicked a band along.

With those twin innovations, Kenny Clarke

invented modern jazz drumming. His fleet new style had begun to evolve

in the late 1930s, alongside other new developments that would blossom

into bebop. The very fast tempos were easier to handle on ride cymbal

than bass drum, and all the crazy accents let him do more with less.

Plus, string bass' role was expanding, and Clarke wanted his bass drum

out of its way. He explored his jittery new phrasing during legendary

sessions at Minton's in Harlem in the early '40s, with Dizzy Gillespie,

Thelonious Monk and guitarist Charlie Christian.

Clarke was drafted in 1943, and was still in uniform two

years later when the first bebop records got cut in New York. His

absence from those early bop sessions is one reason he never quite got

his due. But he made up for lost time after the war. While Clarke was

away, bebop had broken through as jazz's next wave. In trumpeter Dizzy

Gillespie's 1946 big band, everyone had mastered those tricky new

rhythms, as in "Things to Come."

Gillespie's four-piece rhythm section with Milt Jackson on vibes eventually became the Modern Jazz Quartet;

they were quite successful, but also too sedate for Kenny Clarke, who

quit in 1955. He just wanted to swing in any setting, and not just using

cymbals. He got the same smooth continuity with brushes on snare, and

had plenty of other techniques and colors at hand. Clarke was known for

the beautiful sound he coaxed from the drums, and singers adored the

lift he gave them. (He backed his ex-wife Carmen McRae on her 1954

debut.)

Kenny Clarke recorded a lot in the early '50s, with

Miles and Monk and Mingus and many more, but he craved a change. He'd

always gotten a warm reception in France as a GI or visiting musician,

and he resettled in Paris in 1956. That second, much longer absence from

the U.S. cost him more recognition. But he worked steadily, sometimes

with other expats like Dexter Gordon, Don Byas, Bud Powell or Sidney Bechet.

For 11 years, he and pianist-composer Francy Boland co-led the

Clarke-Boland Big Band that made plenty of room for their crack

international soloists — and for the drums.

Clarke stayed in

France, made a family there and taught a lot of students. He recorded

less often in his final decade, after a 1975 heart attack. On one of his

last sessions, in New York in 1983, he made up a percussion quartet

with avant-garde drummers Andrew Cyrille, Milford Graves and Famadou Don Moye. To the end, Kenny Clarke stayed open to new possibilities for the drums.

Kenny Clarke Biography

Born on January 9, 1914, in Pittsburgh, PA; died on January 26, 1985, in Paris, France.

In The Jazz Exiles, Bill Moody called Kenny Clarke "the man who changed the course of jazz drumming." In MusicHound Jazz,

Clarke is described as "probably the most important figure in the

transition from swing to early bebop drumming." In any survey of jazz

from the 1940s through the 1960s, Clarke is omnipresent: he is at New

York's legendary Minton's Playhouse, fomenting bebop alongside

Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, and Charlie Parker; he is present ten

years later at the Birth of the Cool recording sessions, shifting

bebop into more formal structures alongside Miles Davis and the Modern

Jazz Quartet. In the late 1950s he joined the mass emigration of jazz

musicians to Paris, joining such luminaries as Bud Powell and Dexter

Gordon. Clarke's name appears as composer on two of the most famous

tunes in jazz: Monk's "Epistrophy" and Gillespie's "Salt Peanuts."

Kenny Clarke is probably the most famous jazzman the public has never

heard of. Unlike his friend and rival Max Roach, Clarke cultivated

anonymity. As quoted in Scott DeVeaux's Birth of Bebop, Clarke

once told an interviewer: "I always concentrated on accompaniment. I

thought that was the most important thing, my basic function as a

drummer, and so I always stuck with that. And I think that's why a lot

of the musicians liked me so much, because I never show off and always

think about them first." While Clarke's drumming made him a perfect

accompanist to the likes of Gillespie and Parker, it stood out like a

sore thumb in the swing bands he played with early on in his career. A

widely circulated story told in DeVeaux's book has a trumpeter for Teddy

Hill's big band complaining to the bandleader, "Man, we can't use

[Clarke] because he breaks up the time too much." Clarke was fired

shortly thereafter.

It wasn't that Clarke couldn't keep time; indeed, he had been a

reliable swing drummer all his life. Clarke was born on January 9, 1914,

in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. While details of his early life are

scarce, it is known that he studied all manner of instruments in high

school, from the vibraphone to the piano. He got his start playing drums

in local big bands as a teenager, eventually graduating to the touring

bands of Roy Eldridge and Lonnie Simmons, both 1935, Claude Hopkins, and

the Edgar Hayes Big Band, which gave Clarke his first recording session

and the first of many trips to Europe. But swing drumming consisted

mainly of pounding out a 4/4 beat on the bass drum, adding the

occasional accent on the cymbals. Clarke was searching for something new

and was constantly engaged in behind-the-scenes experimentation. He

told Nat Hentoff, editor of Hear Me Talkin' to Ya: "I was trying

to make the drums more musical instead of just a dead beat ... with the

drums as a real participating instrument with its own voice."

When Clarke joined Hill's band in 1939, he encountered a kindred

spirit in fellow bandmate Dizzy Gillespie: "[Gillespie] got into

everything!" Clarke told Down Beat. "He couldn't stay still; the

man always was reaching out. I'd write out little things and hand them

back to my man--Diz always sat right behind the drums. He would play

them; then we'd play them together. We had the fire. There was an

excitement inside us; we knew we were moving into something." One day,

the dam finally burst, and Clarke inadvertently arrived at a rhythmic

innovation, as quoted in The Birth of Bebop: "It just happened

sort of accidentally....We were playing a real fast tune once with Teddy

Hill-- 'Old Man River,' I think--and the tempo was too fast to play

four beats to the measure, so I began to cut the time up. But to keep

the same rhythm going, I had to do it with my hand, because my foot just

wouldn't do it.... So then I began to think, and say, 'Well, you know,

it worked. It worked and nobody said anything, so it came out right. So

that must be the way to do it.'"

In other words, Clarke began keeping time on the ride cymbal and

using the bass drum to provide accents, a practice that became known as

"dropping bombs." Keeping time on the cymbal gave the music a much

brighter, lighter, more propulsive feel. But Clarke's use of the bass

drum was equally revolutionary. It wasn't just that he was using it for

accents, it was where he was placing those accents. He dropped bombs to

fill in gaps in the brass phrasing and to spur on soloists--nothing

could have been further from the staid rhythmic style of big band swing.

It was those accents, which Hill called "kloop-mop," that earned Clarke

the nickname "Klook."

Although Hill fired Clarke, he respected him, and when his own big

band failed in 1940, Hill hired Clarke to lead the band at the

down-and-out Harlem nightclub called Minton's Playhouse. According to

DeVeaux, Hill told Clarke: "Now Kenny, I'm managing this place. I want

you to be the bandleader. You can drop all the bombs, all the re-bop and

the boom-bams you want to play, you can do it here." The first musician

Clarke hired was a then-unknown pianist named Thelonious Monk, and thus

the bebop movement was born.

The jazz scene in New York in the early 1940s was studded with

after-hours clubs, mostly in Harlem, where big-band musicians would go

after gigs. At the clubs they would engage in "jam sessions" or "cutting

contests," seeking both to prove and improve their instrumental skills.

Given Monk and Clarke's peculiar rhythmic and harmonic predilections,

the scene at Minton's rapidly became a laboratory for the new style. In

Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns's Jazz: A History of America's Music,

guitarist Danny Barker describes the first time he heard Clarke and

Monk playing together: "Monk started. Klook fell in, dropped in, dived

in, sneaked in; by hook or by crook, he was in.... You would look, hear

the off-, off-, off-beat explosion and think 'fireworks,' and then the

color patterns formed in the high sky of your mind."

But the new musicians had no name for what they were doing; they

simply called it "playing modern." As the movement began to build,

audiences became more and more familiar with the opening count. In Jazz

Gillespie is quoted as saying that for most tunes, "we just wrote an

intro and a first chorus. I'd say 'Dee-da-pa-da-n-de-bop.' And we'd go

into it. People, when they'd want to ask for one of those numbers and

didn't know the name, would ask for 'bebop.'" As bebop caught on,

Clarke's looser, more "modern" style began to affect drumming as a

whole. Suddenly more conventional gigs were opening up, and Clarke

played with Louis Armstrong and His Big Band and behind such luminaries

as Ella Fitzgerald, Benny Carter, and Coleman Hawkins.

In 1943 Clarke was drafted into the Army, which brought him back to

Europe, where he met future collaborator John Lewis. By the time he

returned to New York in 1946, bop and its self-appointed spokesperson

Dizzy Gillespie were famous; the music had become a national movement,

and change was once again afoot. In a midtown basement, Gil Evans was

conducting a jazz laboratory of his own, one that attempted to harness

the harmonic and rhythmic energy of bebop to more formal, classical

structures. In Jazz, Miles Davis, a regular at Evans's sessions,

is quoted as saying "Bird [Charlie Parker] and Diz were great, [but] if

you weren't a fast listener you couldn't catch the humor or feeling of

their music. Their music wasn't sweet and it didn't have harmonic lines

that you could easily hum with your girlfriend trying to get over with a

kiss." Evans and Davis and saxophonist Gerry Mulligan were striving for

a more balanced feel, where the soloists would somehow be integrated

with the ensemble, and the ensemble playing would have the freedom and

eloquence of soloing. The outcome of these sessions was the Miles Davis

Nonet, which in 1949 recorded the classic Birth of the Cool, with

Kenny Clarke playing drums. Cool Jazz, a bebop movement characterized

above all by its restraint and formal sophistication, had been born;

once again, Kenny Clarke was there.

He was there, too, at the birth of another exemplar of Cool Jazz, the

Modern Jazz Quartet. In 1948 Clarke had gone on tour with Gillespie's

big band, which, like Evans's, was struggling to find a way to integrate

formal ensemble structures with the vibrancy of bebop. The effort left

Gillespie's trumpeters so exhausted that halfway through the set,

drummer Clarke, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, bassist Ray Brown, and

pianist John Lewis would play together for 15 minutes as a sort of

intermission. After leaving the big band, the four stayed together as

the Milt Jackson Quartet, playing Lewis's careful, contrapuntal

arrangements. The four decided early on to abandon the concept of a

bandleader, and they changed their name to the Modern Jazz Quartet. They

were as far as could be from the hepcat, bohemian image of the jazz

musician: they played sober, they wore tuxedos onstage. While musicians

like Parker were giving their compositions primitivist titles like

"KoKo" or "Ri-Bop," Lewis wrote tunes with arty, European-sounding

titles like "Vendome." Ted Gioia has noted in his History of Jazz

that the Modern Jazz Quartet is the "quintessential cool band

remarkable for its longevity and popularity, as well as its consistently

high musical standards," but by 1955, Clarke had had enough.

Indeed, he had had enough of life in the States, period. He told

Zwerin, "Economically everything was all right, but there was something I

had to clear up in my mind. You know people look for different things

in life, but all I wanted was peace and quiet--and money." He told Mike

Zwerin of the Culturekiosque website that he began turning down gigs:

"Miles [Davis] knocked on my door, so I told the little girl I was with

to tell him I'm out. He just kept knocking, said 'Klook, Klook, I know

you're in there.' I just didn't feel like going on that gig. I'd been

recording for Savoy Records almost every day. I was tired, man." Unsure

of what to do, Clarke moved to Paris, the city he had fallen in love

with in 1939 while touring with the Edgar Hayes Big Band. He was not

alone. Dexter Gordon had already moved there, Stan Getz and Bud Powell

would do so shortly. Paris was a city legendary for its love of American

jazz.

When Down Beat's Burt Korall travelled to Paris to interview

Clarke in 1963, the drummer had only good things to say about his

adoptive country. Clarke's exile did not separate him from other

American jazz musicians, who traveled through Paris frequently. With

pianist Powell and French bassist Pierre Michelot, Clarke founded the

Three Bosses, who backed legendary saxophonist Dexter Gordon on his

classic Blue Note recording Our Man in Paris. The Down Beat

interview, however, also revealed a deepening conservatism, expressed

in criticism of such next-generation jazzmen as John Coltrane and Eric

Dolphy. This conservatism was perhaps also expressed by Clarke's return

to the music he grew up on: swing. In 1960 he co-founded the

Clarke-Boland Big Band with arranger Francy Boland. Conservative though

it may have been, according to Zwerin, they "created some of the

fattest, most swinging big band sounds ever, and almost single-handedly

kept the genre in the public's ears--at least the European public."

Clarke died on January 26, 1985, in Paris, France; as Moody puts it in Jazz Exiles, Clarke had become "an elder statesman for the ... jazz exiles."

by David Levine

Kenny Clarke's Career

Played drums in touring big bands as a teen; played with Thelonious

Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian as bandleader at Minton's

Playhouse, beginning 1940; played on classic Birth of the Coolsessions

with the Miles Davis Nonet, 1949; founded Modern Jazz Quartet with John

Lewis and Milt Jackson, 1951; emigrated to Paris, formed Three Bosses

with American pianist Bud Powell and French bassist Pierre Michelot,

1955; Three Bosses recorded classic Our Man in Paris behind Dexter Gordon, 1963; co-founded Clarke-Boland Big Band with Belgian arranger Francy Boland, 1960.

Famous Works

- Selected discography

- Solo

- Klook's Clique , Savoy, 1955; reissued, 1988.

- Telefunken Blues , Savoy, 1955; reissued, 1993.

- Bohemia after Dark , Savoy, 1956; reissued, 1996.

- Clarke-Boland Big Band , Atlantic, 1963; reissued, Koch International, 2000.

- With the Modern Jazz Quartet

- The Artistry of the Modern Jazz Quartet , Prestige, 1952-55; reissued, 1986.

- With others

- (Miles Davis) Birth of the Cool , Capitol, 1949-50; reissued, 2001.

- (Dexter Gordon) Our Man in Paris , Blue Note, 1963; reissued, 1987.

Further Reading

Sources

Books

- DeVeaux, Scott, The Birth of Bebop: A Social and Musical History, University of California Press, 1997.

- Gioia, Ted, The History of Jazz, University of Oxford Press, 1997.

- Holtje, Steve, and Nancy Ann Lee, editors, MusicHound Jazz: The Essential Album Guide, Visible Ink Press, 1998.

- Moody, Bill, The Jazz Exiles, University of Nevada Press, 1993.

- Shapiro, Nat, and Nat Hentoff, editors, Hear Me Talkin' to Ya, Rinehart & Co., 1955.

- Ward, Geoffrey C., and Ken Burns, Jazz: A History of America's Music, Knopf, 2000.

Online

- Down Beat.com, http://www.downbeat.com (November 5, 2001).

- "Kenny Clarke," Jazz, http://www.pbs.org/jazz/biography/artist_id_clarke_kenny.htm (November 20, 2001).

- "Kenny Clarke," Sonicnet, http://www.sonicnet.com/artists/biography/504796.jhtml (November 20, 2001).

- "Kenny Clarke: Dropping Bombs on Paris," Culturekiosque, http://www.culturekiosque.com/jazz/miles/rhemile14.htm (November 20, 2001).

Let's learn about: Kenny Clarke

Pittsburgh drummer Kenny Clarke help put the "bop" in bebop

music by creating the innovative tempos that paved the way for this new

musical genre.

Mr. Clarke, who was born in 1914, grew up on Wylie Avenue in

Pittsburgh's Hill District. He came from a musical family and developed

an early love for the piano, trombone and drums.

While still in high school, Mr. Clarke played multiple instruments,

including trombone and vibes, and even composed some of his own music.

Just a teenager, he caught on and began playing with multiple

Pittsburgh-based bands before traveling the Midwest with the

Jeter-Pillars band and finally heading to New York.

After landing in the Big Apple in the mid-1930s, he collaborated with

dozens of jazz greats, including legendary performer Dizzy Gillespie.

Together, the musicians developed the fundamental rhythms used in the

emerging bebop style.

Traditionally, drummers were used as timekeepers, but Mr. Clarke used

cymbals to keep the song's tempo, allowing him to unleash his

creativity on the snares and high-hats. His unusual beats were known as

"dropping bombs" and "klook-mops," earning him the nickname "Klook."

By freeing drummers from their predictable roles, Mr, Clarke finally

put his instrument in the spotlight. His innovative style set the stage

for the development of the bebop combo, creating exciting band

improvisation.

Eventually, audiences caught on to the new, exotic bebop sound, and

today, Mr. Clarke's rhythms can be heard throughout a wide variety of

music, including modern jazz, spoken-word poetry and contemporary rap.

Learn more about Mr. Clarke and other Western Pennsylvania jazz

legends at the History Center's exhibition "Pittsburgh: A Tradition of

Innovation," where visitors can step inside a re-creation of The

Crawford Grill and listen to music from some of the region's most

prominent jazz musicians.

Drummers

Kenny “Klook” Clarke

Kenny Clarke emerged from the swing bands of the ’30s, but was

actually the first important drummer of the bop era. Born in Pittsburgh

in 1914, Clarke began his career with Roy Eldridge and around the

Midwest with the Jeter-Pillars band. He made his first recordings with

Edgar Hayes in 1937, and later worked with Claude Hopkins, Teddy Hill,

Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Benny Carter.

Following his army discharge, Clarke returned to New York to join Dizzy Gillespie’s big band, where he made numerous recordings on which we can hear the first indications of drumming based on the use of the bass drum for accents, the timekeeping function shifting over to the ride cymbal, and the left hand interacting with the soloist. In essence, Kenny Clarke was freeing the drummer from a strictly metronomic role, allowing him the opportunity for more creative interplay, and forcing the bass player to share more of the timekeeping burden.

Kenny Clarke recalled experimenting with a new style of drumming as early as 1940 at Minton’s in New York. It was here where his rhythmic ideas meshed with the thinking of young boppers like Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Christian, Thelonius Monk, and Charlie Parker.

“By 1940, I had everything I was trying to do together,” said Clarke. “Before that, I was always thinking, ‘There must be an easier, simpler way to keep the band together.’ I thought about it for many years. I was still playing the old way, but once in a while I’d do that cymbal thing: ding-ding-a-ding. I figured you could hear the time better than on the snare drum. The bottom never changed. I just put the time up on the cymbal to ease the weight of the bass drum. I’d tell the guys to put the time in their heads and play. Once they got it in their heads, I went upstairs to stay. I played the time up there, and it gave my left hand the freedom to do other things.”

Later in his career, Clarke worked on 52nd Street with Tadd Dameron’s sextet, where his relaxed style was a modern extension of the feeling Jo Jones had achieved with the Basie band. His playing had become a synthesis of previous approaches, most notably the ride cymbal of Jo Jones, the unpredictable, explosive solos of Sid Catlett, and the timbral variations of Baby Dodds.

Clarke continued to freelance around New York with important modernists, and in 1952 was instrumental in the formation of the legendary Modern Jazz Quartet. In 1956, he left for Paris, where he took up residence and remained until his death in 1985. More than any player who had come before, Kenny Clarke gave jazz drummers an opportunity to fully express themselves, unleashing the chains that had bound them up to that point. His unique concepts would eventually impact on every jazz drummer the world over.

http://jazzprofiles.blogspot.com/2019/05/klook-kenny-clarke-and-beginnings-of.html

Saturday, May 25, 2019

Klook: Kenny Clarke and The Beginnings of Modern Jazz Drumming

© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

How did the Jazz world get from Gene Krupa to Philly Joe Jones?

The answer to that question is as central as asking how it got from Benny Goodman to Charlie Parker, or from Louis Armstrong to Dizzy Gillespie or from Earl “Fatha” Hines to Bud Powell or from Jimmy Blanton to Charlie Mingus.

Melodically and harmonically, Parker, Gillespie, Powell and Mingus created the basic musical structures of modern Jazz.

Kenny Clarke who acquired the nickname of “Klook-mop” which was later shortened to “Klook” created the rhythmic foundation over which the convoluted and fast moving Bebop lines - melodies- could ride unimpeded by the thump-thump-thump of the swing drum beat with its heavily accented 4-beats to the bar bass drum beat.

[Klook-mop was derived from the sound of the snare-to-bass-drum chatter that early Bebop drummers played behind the ride cymbal beat.]

Kenny’s modern style of drumming seemed to spring forth as a fully formed conception during the early jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse from about 1941 onwards.

In fact, Kenny was piecing his approach together over a four year period from about 1937-1941.

In probing for the sources of modern jazz styles, one is not likely to come upon a more influential figure than drummer Kenny Clarke.

Without Clarke's creative drum developments, there is a good possibility that the bebop phase would not have attained its musical importance and gone on to contribute to contemporary jazz forms. Two European critics have succinctly evaluated Clarke's importance. England's Max Harrison: "He built the rhythmic foundation of the new music." France's Andre Hodeir: "His rhythmic imagination has stimulated the melodic genius of others."

More than a decade ago, Max Roach, considered by many the greatest of the modern drummers, pointed out that a drummer should be able to compose, and he mentioned Clarke as an example. Roach said, "Clarke knows his harmony, melody, and has a million ideas." In the 1959 Down Beat drum issue Roach again spoke of his friend as follows: "I've been partial to Clarke. He doesn't borrow; you don't hear the way he plays anywhere else. It's not African or Afro-Cuban; it's unique."

Kenneth Spearman Clarke's conceptual individuality came to the fore early in his career. He was born Jan. 9, 1914, in Pittsburgh, Pa. His father was a trombonist, and Kenny had a younger brother, Frank, who played bass. Kenny studied piano, trombone, drums, vibra-harp, and theory in high school. His knowledge of keyboard harmony, obtained in those early years, was to be an important aspect of his future development.

His first professional job was with Leroy Bradley's Pittsburgh band for about five years. This was followed by a time with the Eldridge brothers, whose home also was in Pittsburgh. Trumpeter Roy had come in from the road about 1933 and with his late brother, Joe, an alto saxophonist and arranger, had formed a home-town band. It worked out well because if Clarke missed a date, Roy could take over on the drums, which he loved to do.

Clarke made his first trip out of town to join the commercial dance band organized by James Jeter and Hayes Pillars during 1934 in St. Louis, Mo. It is interesting to note that both Christian and Blanton served with the Jeter-Pillars Band about that time too.

Early 1937 found Clarke in New York City with Edgar Hayes' big band. He made his first recording, with Hayes, in March, 1937, and was to record regularly with the band on Decca for more than a year.

One interesting 78-rpm that they made was Decca 1882, Star Dust and In the Mood. It was Hayes' version of Star Dust, performed at a slow to medium tempo, that revived the Hoagy Carmichael song, first recorded in 1927, and started it to the top of the hit list. The reverse side, written by saxophonist Joe Garland, then with the Hayes band, went along for the ride, no one paying it much notice. Two years later Glenn Miller's Bluebird record of In the Mood made it a best-seller.

While on tour in Europe (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, Belgium, and Holland) during early 1938 with Hayes, Clarke made some quintet sides in Stockholm under his own name.

This Hayes band was a forward-looking swing aggregation. Clarinetist Rudy Powell did some arrangements for the group, and several years later, young Dizzy Gillespie was to mention he was interested in Powell's work. The band recorded quite a few swinging originals such as Stomping at the Renny (Renaissance Ballroom in Harlem).

Tenor saxophonist Budd Johnson, while with Earl Hines in 1937, has recalled a battle of bands Hines had with Hayes in Dayton, Ohio. At that time, Johnson said, he noticed some unusual drumming by Clarke.

Clarke himself has said, "I was trying to make the drums more musical. Garland would write out trumpet parts for me to read, and I would use my discretion in playing things that I thought would be effective. These were rhythm patterns superimposed over the regular beat."

After returning from Europe, the drummer and Powell joined the long-established Claude Hopkins Band. Clarke stayed eight months with Hopkins and then went with the Teddy Hill Band, in which he first met Gillespie.

By this time Clarke was well along in evolving a style of his own. The Hayes, Hopkins, and Hill bands played frequently at the Savoy Ballroom. Clarke has said it wore him out trying to keep up the fast tempos required.

One of the numbers in the Hill repertoire that he gives as an example was The Harlem Twister (also known as Sensation Stomp).

To get relief, Clarke fell back on experiments he had been making with his top cymbal. He developed a technique whereby he transferred his timekeeping chore from the bass drum to the top cymbal, riding it with his right hand. His right foot was then free to play off-beat accents on the bass drum, a sort of punctuating function to become known as "bombs." He devoted his left stick to the snare drum, sometimes using it for accents and other times using it to help the cymbal carry the rhythm.

All this confused leader Hill, and Clarke was fired, but he was in the band long enough to make an impression on Gillespie. The trumpeter said he found it stimulating to improvise around Clarke's off-rhythms.

From the Hill band Clarke followed Panama Francis into Roy Eldridge's big band at the Arcadia Ballroom on Broadway. None of these bands — Hopkins, Hill, Eldridge — recorded while Clarke was with them.

In the summer of 1940 Clarke was working with Sidney Bechet's quartet at the Log Cabin in Fonda, N.Y. During the fall of that year Teddy Hill took over the management at Minton's and asked Clarke and trumpeter Joe Guy to bring in a small group. The astute Hill wanted to make the spot a hangout for musicians, and in this setting he was sympathetic to Clarke's experiments. Hill said the drummer's unique figures sounded to him like "kloop" or "klook," and he told Clarke they could play all the "klook-mop music" they wanted at Minton's. I guess it followed naturally that Clarke became known as Klook.

Several writers in discussing the Jerry Newman acetates made in May, 1941, at Minton's have pointed out that actually the only suggestion of the things to come emanated from Clarke's drums. Marshall Stearns, in mentioning the Newman sides in his Story of Jazz, said, ". . . drummer Clark is playing fully matured bop drums."

Clarke worked with Charlie Christian, Thelonious Monk, and Dizzy Gillespie in developing unusual chord changes. The drummer has a long list of original compositions registered with Broadcast Music, Inc., including Klook Returns; Blues Mood; Roll 'Em, Bags; I’ll Get You Yet.

Before he left for the service in 1943, Clarke was a regular at Minton's when in town. During that period he spent a short time in Louis Armstrong's big band, from which he was soon fired, and Armstrong begged Big Sid Catlett to return; five weeks with Gillespie in Ella Fitzgerald's orchestra, which the two joined together and from which they were fired together; Benny Carter's sextet on 52nd St.; and a comparatively long run with Red Allen's small band at the Downbeat Room in Chicago.

At the time Clarke went into service, the new music had not as yet acquired the name bebop. Like Charlie Parker, he was later to disapprove of the appellation and attendant jargon heartily.

For those with a taste for discography, you can hear Kenny evolving the modern style of Jazz drumming on the following recordings, assuming you can find them!

New York City, March 9, 1937

Edgar Hayes and His Orchestra—Bernie Flood, Henry Goodwin, Shelton Hemphill, trumpets; Bob Horton, Clyde Bernhardt, John Haughton, trombones; Stanley Palmar, Al Sherrett, Crawford Wetherington, Joe Garland, saxophones; Hayes, piano; Andy Jackson, guitar; Elmer James, bass; Kenny Clarke, drums. MANHATTAN JAM (201)

..........Variety 586, Vocalion 3773

Stockholm, Sweden, March 8, 1938

Kenny Clarke's Quintet — Goodwin, trumpet; Rudy Powell, clarinet; Hayes, piano; George Gibb, guitar; Coco Darling, bass; Clarke, drums, vibraharp; John Clay Anderson, vocals. ONCE IN A WHILE (6317)

..............Swedish Odeon 255509

I FOUND A NEW BABY (6318).........

..............Swedish Odeon 255509

YOU'RE A SWEETHEART (6319)

..............Swedish Odeon 255510

SWEET SUE (6320)

..............Swedish Odeon 255510

New York City, Feb. 5, 1940

Sidney Bechet and His New Orleans Feetwarmers—Bechet, soprano saxophone, clarinet, vocal; Sonny White, piano; Charlie Howard, guitar; Wilson Myers, bass, vocal; Clarke, drums. INDIAN SUMMER (46832). .Bluebird 10623 ONE O'CLOCK JUMP (46833)

.................RCA Victor 27204

PREACHIN' BLUES (46834)

.....................Bluebird 10623

SIDNEY'S BLUES (46835).. .Bluebird 8509

New York City, May 15, 1940

Mildred Bailey and Her Orchestra— Roy Eldridge, trumpet; Robert Burns, Jimmy Carroll, clarinets; Irving Horowitz, bass clarinet; Ed Powell, flute; Mitch Miller, oboe; Teddy Wilson, piano; John Collins, guitar; Pete Peterson, bass; Clarke, drums; Miss Bailey, vocals. How CAN I EVER BE ALONE?

(27302).............Columbia 35532

TENNESSEE FISH FRY (27303)

....................Columbia 35532

I'LL PRAY FOR You (27304)

....................Columbia 35589

BLUE AND BROKEN HEARTED (27305)

....................Columbia 25589

New York City, Sept. 12, 1940

Billie Holiday and Her Orchestra—Eldridge, trumpet; Georgie Auld, Don Redman, alto saxophones; Don By as, Jimmy Hamilton, tenor saxophones; Wilson, piano; Collins, guitar; Al Hall, bass; Clarke, drums; Miss Holiday, vocals. I'M ALL FOR You (28617)

................Okeh-Vocalion 5831

I HEAR Music (28618)

................Okeh-Vocalion 5831

THE SAME OLD STORY (28619)

......Okeh-Vocalion 5806, V Disc 586

PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT (28620)

.................Okeh-Vocalion 5806

New York City, March 11, 1941

Slim Gaillard and His Flat Foot Floogie Boys—Loumell Morgan, piano; Gaillard, guitar, vocals; Slam Stewart, bass; Clarke, drums.

AH Now (29913)...........Okeh 6295

A TIP ON THE NUMBERS (29914)

.........................Okeh 6135

SLIM SLAM BOOGIE (29915).. .Okeh 6135

BASSOLOGY (29916)..........Okeh 6295

New York City, March 21, 1941

Eddie Heywood and His Orchestra— Shad Collins, trumpet; Leslie Johnakins, Eddie Barefield, alto saxophones; Lester Young, tenor saxophone; Heywood, piano; Collins, guitar; Ted Sturgis, bass; Clarke, drums; Miss Holiday, vocals.

LET'S Do IT (29987)........Okeh 6134,

Columbia 30235, CL 6129, Blue Ace 206 GEORGIA ON MY MIND (29988)

Okeh 6134, Columbia 30235, C3L-21, Blue Ace 206, Jolly Roger 5020 ROMANCE IN THE DARK (29989)

........Okeh 6214, Columbia C3L-21,

Blue Ace 205, Jolly Roger 5020

ALL OF ME (29990)

.......Okeh 6214, Columbia CL 6129,

C3L-21, Blue Ace 205

New York City, May 8, 1941

Minton House Band (with guests)— Joe Guy, Hot Lips Page, trumpets; Ker-mit Scott, Don Byas, tenor saxophones; Thelonious Monk, piano; Charlie Christian, guitar; Nick Fenton, bass; Clarke, drums. UP ON TEDDY'S HILL (HONEYSUCKLE

ROSE) ...............Esoteric ESJ-4,

Counterpoint 548 DOWN ON TEDDY'S HILL (STOMPING

AT THE SAVOY).........Esoteric ESJ-4

New York City, May 12, 1941

Same, except Scott, Byas, and Page are out. ^CHARLIE'S CHOICE (TOPSY)

.......Vox album 302, Esoteric ESJ-1,

Counterpoint 548 STOMPING AT THE SAVOY

......Vox album 302, Esoteric ESJ-1,

Counterpoint 548

* SWING TO BOP is the title on the Esoteric and Counterpoint LPs.

New York City, June 2, 1941

Count Basie and His Orchestra—Ed Lewis, Buck Clayton, Al Killian, Harry Edison, trumpets; Dicky Wells, Dan Minor, Ed Cuffey, trombones; Earl Warren, Jack Washington, Tab Smith, alto saxophones; Don Byas, Buddy Tate, tenor saxophones; Basic, piano; Freddie Green, guitar; Walter Page, bass; Clarke, drums. You BETCHA MY LIFE (30520)

.........................Okeh 6221

DOWN, DOWN, DOWN (30521)

.........................Okeh 6221

New York City, Oct. 6, 1941

Ella Fitzgerald—Teddy McRae, tenor saxophone; Tommy Fulford, piano; Ulysses Livingston, guitar; Beverly Peer, bass; Clarke, drums; Miss Fitzgerald, vocals.

JIM (69784)...............Decca 4007

THIS LOVE OF MINE (69785). .Decca 4007

Source:

Downbeat Magazine

March 28, 1963

The Kenny Clarke - Francy Boland Big Band:

Interview Transcription

The Kenny Clarke

/Francy Boland Big Band claims (through its most eloquent mouthpiece

Gigi Campi) to play “any music that is in the spirit of jazz.” It is a

pretty wide definition and one that will not offend even those musicians

obsessed with the fear of being categorised.

Reports from Tony Brown and Kenny Graham in 1968 about the big jazz band.

by Tony Brown

Source: Jazz Professional

KENNY CLARKE AND FRANCY BOLAND

Kenny Clarke we all know about—a drummer who has carved his own

place in jazz history. Pianist Francy Boland is a much more mysterious

figure—a product of the Royal Conservatoire, Liege, Belgium, whose work

was brought to the notice of Count Basie and Benny Goodman by pianist

Mary Lou Williams. Francy went to America to arrange for them and for

Herman and Gillespie and (we may assume) assimilated plenty.

Boland returned to Europe in 1957. Gigi Campi had been losing his

shirt running his own recording company and promoting jazz tours. On Lee

Konitz’s dates alone he dropped 10,000 dollars. As Francy arrived, Gigi

gave up. But he vowed that if he ever tried again he would find himself

a good rhythm section. And here they were—Boland, the great Kenny

Clarke (he had just settled in Paris) and bassist Jimmy Woode, who left

Ellington to emigrate to Sweden and finished up, like so many at that

time, in Paris.

Says Campi: “It was a fantastic section. I knew the moment I heard them together that one day I would start a big band. Then Kurt Edelhagen came to Cologne and played some of the arrangements Francy had written for Basie . . . ” 40–year–old Gigi Campi was born in Cologne of an Italian father and a German mother. (He is based on the city and owns an ice–cream parlour there.) (Cologne had its traditional Carnival and Gigi did not dig carnival time. “Junk music,” he says scathingly.

“So I put on jazz and my place was filled with people who didn’t

like the old stuff, either. We gave them Lucky Thompson, Ben Webster,

Don Byas, Charlie Shavers—always backed by groups that I put together.”

Kenny Clarke was visiting Cologne and listening to Francy Boland’s

writing, since Francy was then chief arranger for Kurt Edelhagen.

Gigi set up an octet recording for Blue Note—“The Golden

Eight.” Throughout one night, the octet recorded the whole

album—“Difficult music”, observes Campi. “In Kenny Clarke’s opinion, it

was the best group of its kind that has been recorded in the past ten

years.” The pieces were falling into

Kenny Clarke is not widely known for his big–band playing, since the bands he worked with before he joined Dizzy’s great outfit were not issued on record in Europe. “The only record that did him justice”, says Kenny Clare, “was a concert recorded in Paris. It wasn’t issued in Britain, though I managed to get a copy. His time—his actual rhythm playing—is not something that many can do. Gus Johnson has a similar kind of time. So many people would like to be able to get that very springy kind of beat that Klook has. I would. When I’m with him, I can play like that exactly, without even thinking about it. Soon as I’m away from it, I can’t do it any more. Strange. I can’t figure it out.” Kenny Clare got booked with the band originally when Klook got stuck in Spain. Everyone was so impressed that Gigi asked Clare to come back on the next session. It worked out so beautifully that Klook suggested that Kenny become a regular member of the band.

“After that first date”, says Kenny, “they were being nice, really. They gave me a couple of notes on vibraphone that I invariably played wrong. Well, they figured that I’d always be available to do anything that Klook wouldn’t be free to do. I could do sundry percussion. Then one number was a Turkish march thing and I played snare drum. When it was played back it sounded very much together, like one drummer They talked it over. Next time I came would I bring my drums as well? See if we could make it with both of us playing. It worked—and it’s been like that ever since.” Kenny Clarke, they say. might not appear to be a man who feels very involved in what happens in the world outside his music. He keeps pretty much to himself. Yet he has opinions on politics and the world situation—very definite ideas on the great issues.

“He is really a very intelligent man”, says Nat Peck, “And it’s not a superficial intelligence, but something very deep–rooted and something very mature.” They describe Francy Boland as not being a front man in the accepted sense. He is an introverted man and doesn’t speak that much. He doesn’t have a big voice. His authority shows most in his writing—and in the attitude of the musicians toward his writing. According to Gigi Campi, the band is a community. Aside from the obvious differences of colour, the character of every man is in marked contrast to the next. What are they? Catholics, Marxists, Moslems, Zionists, Socialists and Capitalists—a mixture. This was the one aspect of the international band that used to frighten some. With such a mixture is was potentially . . . explosive.

They say that there are seventeen soloists here, each man a strong individualist. Francy just walks to the front, waves a hand and the band blows. He walks back. The band has its own personality—a composite. It is a projection of seventeen musicians. In different circumstances these men might find themselves in conflict. Instead there is tolerance and respect. And affection. When it comes to music there is no argument. Never.

place.

American vocalist Billie Poole was in Cologne in 1961 to open the Storyville Club and wanted to do an album backed by Francy. Riverside agreed

to buy the tapes. The studio and musicians were booked—and at the last

moment Billie was called back to America by a bereavement. Rather than

cancel the session, they decided to record the Kenny Clarke/Francy

Boland Big Band.

How to describe the KC/FB Big Band’s identity? “We are, in a sense, a

Resistance band”, says Gigi. “We are shocking people with our

music—trying to awaken them. Not with so–called New Sounds. There is

nothing new in the sense of tradition. We don’t try to be avant garde.

In my opinion, Francy is the only man who really harmonises when he is

scoring. The sounds and the colour are between the lines, as it were.”

There are others who will confirm that it has the genuine stuff of

Protest. Trombonist Nat Peck has played with the band since its

inception. “It’s a protest against a situation that has come on big

bands of late,” he says. “A lot of people are using bands as a mere

projection of their own personality, forgetting the important role that

the individual musicians play in an orchestra. It’s no longer Ake

Persson on trombone and Benny Bailey on trumpet, but a trumpet and a

trombone. An arranger writes a piece of music and it is full of traps

and tricks and dynamics. The musicians are so involved with the

technical performance that they are handcuffed. They can take no

liberties with the music. They are restrained to such a degree that all

the warmth and the electricity is lost.” (Click the picture to enlarge.)

Boland, says Peck, has such an understanding of what musicians are,

what they mean. Maybe, he concedes, the band has gone to the other

extreme—because there is a conflict between the two attitudes. “I’ve

heard some people say: ‘Yes, it’s a good band—but there are no