SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2019

VOLUME SIX NUMBER THREE

ANTHONY BRAXTON

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

ISAAC HAYES

(December 29—January 4)

THOM BELL

(January 5-11)

THE O'JAYS

(January 12-18)

BOOKER T. JONES

(January 26-February 1)

THE STYLISTICS

OTIS REDDING

(January 19-25)

BOOKER T. JONES

(January 26-February 1)

THE STYLISTICS

(February 2-8)

THE STAPLE SINGERS

(February 9-15)

OTIS RUSH

(February 16-22)

ERROLL GARNER

(February 23-March 1)

EARL HINES

(March 2-8)

BO DIDDLEY

(March 9–15)

BIG BILL BROONZY

(March 16–22)https://www.allmusic.com/artist/booker-t-jones-mn0000772976/biography

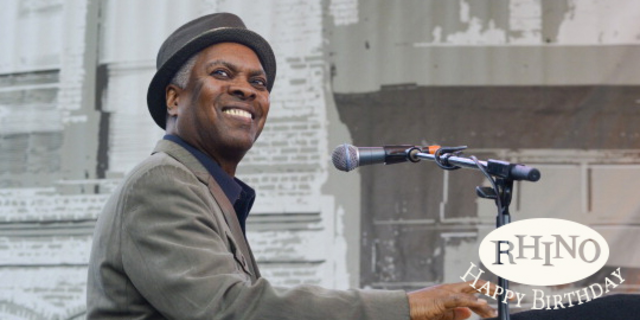

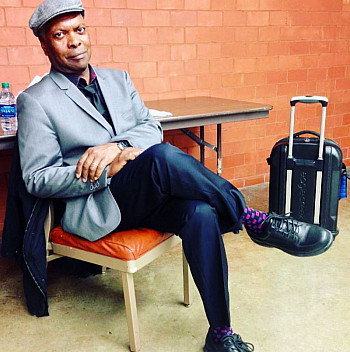

Booer T. Jones

(b. November 12, 1944)

Artist Biography by Mark Deming

Booker T. Jones was one of the architects of the Memphis soul sound of the 1960s as the leader of Booker T. & the MG's, who scored a number of hits on their own as well as serving as the Stax Records house band. But Jones'

accomplishments don't stop there, and as a producer, songwriter,

arranger, and instrumentalist, he's worked with a remarkable variety of

artists, from Willie Nelson to John Lee Hooker, from Soul Asylum to the Roots.

Booker T. Jones was born in Memphis, Tennessee on November 12, 1944. Jones developed an keen interest in music as a boy; while working a paper route, he used to pass by the house of jazz pianist Phineas Newborn, and would often stop and listen to him practice as he folded newspapers. By the time Jones was in high school, he helped to direct the school band and was proficient on saxophone, trombone, oboe, and keyboards; he also played organ during services at his church, and would occasionally sneak out and sit in with R&B combos at local nightclubs. In 1960, Jones, a frequent customer at Memphis' Satellite Record Shop, was recruited to play sax on a Rufus and Carla Thomas recording session when the proprietors of the store, Estelle Axton and Jim Stewart, decided to start their own record label. The label soon evolved into Stax Records, and Jones, along with guitarist Steve Cropper (who was managing the record store when he met Jones), bassist Lewis Steinberg (later replaced by Donald "Duck" Dunn), and drummer Al Jackson Jr., would form the MG's, who would back up Stax artists Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Eddie Floyd, Albert King, and many others, as well as releasing a steady stream of instrumental recordings on their own, including the smash hit "Green Onions." Jones' productivity in the early to mid-'60s is all the more remarkable as he was also a full-time student at Indiana University, where he studied composition and music theory while doing shows and recording sessions during weekends and vacations.

Booker T. & the MG's enjoyed considerable success in their heyday -- cutting hits, backing Stax's leading artists, touring Europe and the U.K. with the Stax/Volt Revue, and accompanying Otis Redding for his legendary set at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival -- but between internal disputes at Stax (mostly regarding the spoils of their successful distribution deal with Atlantic Records) and the increasingly busy schedules of the various members, the group was on the verge of breaking up, and in 1970, Jones relocated to Los Angeles. He had already been branching out, appearing on Delaney & Bonnie's 1969 album Home and Mitch Ryder's ambitious The Detroit-Memphis Experiment, and after 1971's Melting Pot, the MG's quietly broke up. Jones stayed busy with session work, playing on albums by Bob Dylan, Steven Stills, Kris Kristofferson, and Rita Coolidge, and in 1971 he released Booker T. & Priscilla, the first of two albums he would record with his then-wife, Priscilla Coolidge-Jones (the sister of Rita Coolidge). The same year, Jones produced Just as I Am, the outstanding debut album by Bill Withers, which featured the hits "Ain't No Sunshine" and "Grandma's Hands." In 1975, Jones and the MG's were working on a reunion album when Al Jackson, Jr. was murdered; the group continued to record with drummer Willie Hall, but they parted ways again in 1977. In 1978, Jones released his first solo album, Try and Love Again, and enjoyed one of his biggest successes as a producer with Willie Nelson's Stardust, a collection of pop standards that established Nelson as one of country's biggest crossover acts.

Session work and production assignments with Nelson dominated Jones' schedule in the '80s, though he released a second solo album, I Want You, in 1981; another followed late in the decade, 1989's The Runaway. In 1992, Booker T. & the MG's were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and that same year, the group reunited for a special, high-profile gig: they served as the house band for an all-star tribute to Bob Dylan staged in honor of the songwriter's 30th year as a recording artist. Neil Young, one of the artists who appeared at the concert, was impressed enough with the MG's that he invited them to serve as his backing band for a major concert tour in 1993. The tour sparked new interest in the band, and in 1994, Jones and the MG's cut a new album, That's the Way It Should Be, and they supported it with a number of live dates. Jones soon returned to a steady schedule of session work, and he produced as well as performed on Neil Young's 2002 album Are You Passionate? But in 2008, Jones stepped up for one of his most ambitious solo efforts to date, Potato Hole, in which he was backed up by country-influenced hard rockers the Drive-By Truckers, with Neil Young adding additional guitar on several tunes. The album earned enthusiastic reviews, and Jones supported the release with a number of live dates in America, Europe, and the U.K. In 2011, Jones returned with another inspired collaboration, The Road from Memphis, in which he teamed up in the studio with Philadelphia-based hip-hop/modern soul collective the Roots. Jones returned to Stax Records, now under the Concord Records umbrella, for 2013's guest-laden Sound the Alarm.

Booker T. Jones was born in Memphis, Tennessee on November 12, 1944. Jones developed an keen interest in music as a boy; while working a paper route, he used to pass by the house of jazz pianist Phineas Newborn, and would often stop and listen to him practice as he folded newspapers. By the time Jones was in high school, he helped to direct the school band and was proficient on saxophone, trombone, oboe, and keyboards; he also played organ during services at his church, and would occasionally sneak out and sit in with R&B combos at local nightclubs. In 1960, Jones, a frequent customer at Memphis' Satellite Record Shop, was recruited to play sax on a Rufus and Carla Thomas recording session when the proprietors of the store, Estelle Axton and Jim Stewart, decided to start their own record label. The label soon evolved into Stax Records, and Jones, along with guitarist Steve Cropper (who was managing the record store when he met Jones), bassist Lewis Steinberg (later replaced by Donald "Duck" Dunn), and drummer Al Jackson Jr., would form the MG's, who would back up Stax artists Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Eddie Floyd, Albert King, and many others, as well as releasing a steady stream of instrumental recordings on their own, including the smash hit "Green Onions." Jones' productivity in the early to mid-'60s is all the more remarkable as he was also a full-time student at Indiana University, where he studied composition and music theory while doing shows and recording sessions during weekends and vacations.

Booker T. & the MG's enjoyed considerable success in their heyday -- cutting hits, backing Stax's leading artists, touring Europe and the U.K. with the Stax/Volt Revue, and accompanying Otis Redding for his legendary set at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival -- but between internal disputes at Stax (mostly regarding the spoils of their successful distribution deal with Atlantic Records) and the increasingly busy schedules of the various members, the group was on the verge of breaking up, and in 1970, Jones relocated to Los Angeles. He had already been branching out, appearing on Delaney & Bonnie's 1969 album Home and Mitch Ryder's ambitious The Detroit-Memphis Experiment, and after 1971's Melting Pot, the MG's quietly broke up. Jones stayed busy with session work, playing on albums by Bob Dylan, Steven Stills, Kris Kristofferson, and Rita Coolidge, and in 1971 he released Booker T. & Priscilla, the first of two albums he would record with his then-wife, Priscilla Coolidge-Jones (the sister of Rita Coolidge). The same year, Jones produced Just as I Am, the outstanding debut album by Bill Withers, which featured the hits "Ain't No Sunshine" and "Grandma's Hands." In 1975, Jones and the MG's were working on a reunion album when Al Jackson, Jr. was murdered; the group continued to record with drummer Willie Hall, but they parted ways again in 1977. In 1978, Jones released his first solo album, Try and Love Again, and enjoyed one of his biggest successes as a producer with Willie Nelson's Stardust, a collection of pop standards that established Nelson as one of country's biggest crossover acts.

Session work and production assignments with Nelson dominated Jones' schedule in the '80s, though he released a second solo album, I Want You, in 1981; another followed late in the decade, 1989's The Runaway. In 1992, Booker T. & the MG's were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and that same year, the group reunited for a special, high-profile gig: they served as the house band for an all-star tribute to Bob Dylan staged in honor of the songwriter's 30th year as a recording artist. Neil Young, one of the artists who appeared at the concert, was impressed enough with the MG's that he invited them to serve as his backing band for a major concert tour in 1993. The tour sparked new interest in the band, and in 1994, Jones and the MG's cut a new album, That's the Way It Should Be, and they supported it with a number of live dates. Jones soon returned to a steady schedule of session work, and he produced as well as performed on Neil Young's 2002 album Are You Passionate? But in 2008, Jones stepped up for one of his most ambitious solo efforts to date, Potato Hole, in which he was backed up by country-influenced hard rockers the Drive-By Truckers, with Neil Young adding additional guitar on several tunes. The album earned enthusiastic reviews, and Jones supported the release with a number of live dates in America, Europe, and the U.K. In 2011, Jones returned with another inspired collaboration, The Road from Memphis, in which he teamed up in the studio with Philadelphia-based hip-hop/modern soul collective the Roots. Jones returned to Stax Records, now under the Concord Records umbrella, for 2013's guest-laden Sound the Alarm.

Booker T. Jones’ New Memoir to Be Released Next Year

“I want to share with readers how each step of my winding, rocky road has led me to where I am today,” musician says

Booker T. Jones will be releasing a new memoir

next year. Richard Isaac/LNP/REX/Shutterstock

Multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and producer Booker T. Jones will be releasing his long-awaited memoir next fall. The leader of the Stax Records house band and Memphis soul legend’s as-yet-untitled tome is projected for release this fall via Little, Brown and Company. An audiobook version will be available simultaneously through the publisher’s Hachette Audio.

The memoir will explore Jones’ half-century in music and his artistic process, chronicling both his personal journey as well as career hallmarks. It will traverse his early years in the segregated South and examine the music industry pitfalls he experienced along with him revisiting the nightclubs of his youth. It will also trace his successes with Booker T. & the M.G.’s., delve into Stax Records and discuss his group’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992.

“Had

I known in third grade when I started playing my clarinet that one day I

would be playing with the likes of B.B. King, Otis Redding, or Bob

Dylan, I might have been too paralyzed to continue my journey,” Jones

said in a statement. “But in life, you do things one moment at a time.

That’s what I want to share with readers—how each step of my winding,

rocky road has led me to where I am today.”

The book will also offer a behind-the-scenes look at the music history he helped shape, such as discussing the writing of Booker T. & the M.G.’s “Green Onions” while he was still a high school student, to talking about the recording of Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ on) the Dock of the Bay” and detailing collaborations with Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave, Neil Young, Carlos Santana and Willie Nelson.

Last year, Jones told Rolling Stone why he was inspired to write a memoir, recalling that he feels just excited about making music as when he was a teenager. “I think of musicians as a brotherhood with a purpose, and our purpose is being realized right now, so if I have anything to say it’s about that: what music means to people, what we can give people with our work, whether they use it for pleasure or for spiritual events, weddings, or just living day-to-day,” he said. “It’s about connecting to each other, understanding each other. I think you’re not ever completely alone out here if you’re connecting through music or art.”

https://www.kuumbwajazz.org/soul-legend-booker-t-jones-creative/

Soul legend Booker T. Jones as creative now as he’s ever been

Wednesday, 15 January 2014 | Wallace Baine | Santa Cruz Sentinel

He could have born anywhere, in Little Rock, in Charlotte, in Baltimore. But in the fall of 1944, Booker T. Jones was born in Memphis. And that fact of geography not only shaped his life, it deeply influenced American music as well.

Today, Jones is something beyond a mere star. He is a member of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and a recipient of the Grammys’ Lifetime Achievement Award. He’s also one of the few people that can be said to have pioneered a beloved American musical genre: soul music.

As the frontman for Booker T. & the MGs and the prime instrumentalist behind the groundbreaking sound of Stax Records in the 1960s, Jones was an architect of a distinct Memphis sound that helped delivered R&B from Ray Charles in the 1950s to the funk of the 1970s.

And it might not have happened had been born some other place. Jones grew up as something of a musical prodigy, playing saxophone, trombone, piano, even oboe throughout his school years.

“Memphis is special,” said Jones who performs live for two shows at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center on Monday. “As a young musician, there were just so many opportunities, so many clubs to play, so many musicians to play with. In school, there were all kinds of instruments available to me. It was a gathering place for musicians from all around. Really, for musicians who have grown up in Memphis and have left, Memphis is a frame of mind.”

Jones will forever be famous for the 1962 Top Five hit “Green Onions,” one of the most famous instrumentals in pop music history. Jones wrote and recorded the song with his fabled band the MGs while still in high school.

“It was a Sunday afternoon and I was enjoying some free studio time,” he said. “I hadn’t even graduated (high school) yet.”

The MGs were a four-piece band that was a rarity in the days of civil rights unrest. They were a racially integrated band. Jones and drummer Al Jackson Jr. were black; guitarist Steve Cropper, bass player Lewie Steinberg and Steinberg’s replacement Duck Dunn were all white.

“You know, it was not a big deal to us at that time,” he said. “It’s a big deal now, looking back on it. But not then. We were just haphazardly thrown together mainly because we all like the same kind of music.”

The MGs did not make their most lasting mark as a recording act in their own right, but as the house band at Stax, though they continued to release hit records after “Green Onions,” including “Hip-Hug-Her” and “Hang-‘Em High.” The band backed up many of the most glorious names of the era: Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Albert King and others. Over his long, 50-plus-year career, Jones has played on many landmark recordings. He was the piano player on Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” and the bass player on Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.” He was the producer of songs such as “Ain’t No Sunshine” by Bill Withers and Willie Nelson’s “Georgia on My Mind.”

However, at 69, Jones is no oldies act. The last five years have been one of his most fruitful periods as a recording artist, as he has found a new groove as an instrumentalist, composer and collaborator. His 2009 album “Potato Hole” on which he brought in the popular indie country band the Drive-By Truckers — Truckers’ lead man Patterson Hood is the son of David Hood, a long-time session man from Muscle Shoals, Ala., and a contemporary of Jones. The album won a Grammy.

In 2011, Jones released the ambitious where he unleashed his trademark Hammond B-3 organ in tribute to the city that created him, with such eye-popping guest collaborators as ?uestlove from the hip-hop band the Roots, and the late Lou Reed. In 2013, Jones was in record stores again with the album “Sound the Alarm,” which marked his return to Stax for the first time in 40 years.

“I think I’ve always been a creative person since I was probably six or seven years old and started playing ukulele and piano. And I’ve had a lot of ideas in my mind the whole time. But I haven’t really had the opportunity to record my ideas until recently.”

Stax Records is not what it used to be. The great Memphis label is now headquartered in Beverly Hills. With his return, Booker T. is the last echo of what Stax used to be, he said.

“They were really nice to me when I walked in,” he said. “I kind of think that I’m the constant between then and now. You know, just carrying on the tradition.”

{ Monday Two shows: 7 and 9 p.m. Kuumbwa Jazz Center, 320-2 Cedar St., Santa Cruz. $30 advance; $35 at the door. www.kuumbwajazz.org. }

https://www.songfacts.com/blog/interviews/booker-t-jones

Songwriter Interviews

Booker T. Jones

by Roger Catlin

While

still a teenager and a studio musician at Stax Records, Booker T. Jones

came up with one of the defining instrumentals of soul in "Green Onions."

There followed a career as head of Booker T. & the MG's, with ace

guitarist Steve Cropper, drummer Al Jackson Jr. and eventually Donald

"Duck" Dunn on bass, recording a series of instrumental hits and backing

Stax artists like Otis Redding in the studio and on tour. Since then,

he's produced Bill Withers' debut and Willie Nelson's Stardust

album, recorded with Stephen Stills (on his first album), and backed

Neil Young as part of the Bob Dylan 30th anniversary concert, where he

led the house band.

Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992, Jones earned a lifetime achievement Grammy a decade ago. Since then, he's recorded with Drive-By Truckers, played on the Elton John-Leon Russell album, and released a solo album, The Road from Memphis, with contributions from Questlove, Lou Reed and Sharon Jones.

Though he sometimes tours with a big Stax revue show, Jones at 72 was on the road earlier this year with a quartet featuring his son Ted on guitar. He spoke from snowy Lake Tahoe not long after the 2017 Grammys about his early days, playing the Monterey Pop Festival, and the qualities of the B-3.

Roger Catlin (Songfacts): Hey there, how is everything in Lake Tahoe? Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992, Jones earned a lifetime achievement Grammy a decade ago. Since then, he's recorded with Drive-By Truckers, played on the Elton John-Leon Russell album, and released a solo album, The Road from Memphis, with contributions from Questlove, Lou Reed and Sharon Jones.

Though he sometimes tours with a big Stax revue show, Jones at 72 was on the road earlier this year with a quartet featuring his son Ted on guitar. He spoke from snowy Lake Tahoe not long after the 2017 Grammys about his early days, playing the Monterey Pop Festival, and the qualities of the B-3.

Booker T. Jones: I've got snow above my height. Looking at icicles that look like daggers. Lake Tahoe. The road is closed to Reno. We're doing fine. The sun is shining, the icicles are melting, but it's been an unbelievable storm.

Songfacts: Sounds like you were busy at the Grammys.

Booker T: I played the Tom Petty tribute at MusiCares. We played all his songs for the MusiCares benefit show, with all the guests who came - Norah Jones and a lot of people who played Tom Petty songs - and we raised a bunch of money for MusiCares. They raised $8.5 million.

Held

two days before the Grammy Awards, the 27th annual gala benefitting the

MusiCares Foundation in Los Angeles broke a record for fundraising,

with proceeds going to musicians in medical or financial need. The

previous record event, the 2016 gala honoring Lionel Richie, raised $7.2

million. Jones helmed the house band that also included David

Mansfield, Jay Bellerose, Larkin Poe and a number of Tom Petty's

Heartbreakers.

It was also the longest gala, with performances by Jackson Browne, Randy Newman, George Strait, Foo Fighters, Gary Clark Jr., Lucinda Williams, Jakob Dylan, Taj Mahal, Don Henley, Jeff Lynne and Stevie Nicks, as well as Petty. Younger acts on the bill included The Head and the Heart, Regina Spektor, Cage the Elephant, The Lumineers and Elle King.

It was also the longest gala, with performances by Jackson Browne, Randy Newman, George Strait, Foo Fighters, Gary Clark Jr., Lucinda Williams, Jakob Dylan, Taj Mahal, Don Henley, Jeff Lynne and Stevie Nicks, as well as Petty. Younger acts on the bill included The Head and the Heart, Regina Spektor, Cage the Elephant, The Lumineers and Elle King.

Songfacts: Are those difficult to do? It seems like you would need to know all the songs, and all of the performers as well.

Booker T: It takes some work. I got there on the previous Saturday, and the show was on Friday. It took some rehearsal, but it was fun. His songs are good, and the performers are good. Jakob Dylan sang a song, and Gary Clark Jr. sang a song and a guy from the Eagles. It was good.

Songfacts: You've done a number of those kinds of events. I'm thinking of the Bob Dylan 30th Anniversary Concert at Madison Square Garden in 1992 and at the White House as well.

Booker T: A couple of shows at the White House, yeah.

Songfacts: What are those like to do?

Booker T: If you're the music director, it's a lot of work, but if you're just playing the organ like I was, it can be a lot of fun. I was the music director for the White House shows, so that was Mick Jagger and B.B. King, and a lot of artists from Memphis. There were two shows: a Memphis show, and a tribute to the blues show.

Songfacts: Is there added pressure because of where you are?

Booker T: It's a lot of pre-preparation, because the music changes keys a lot and the arrangements change. And then everything has to be provided. The production company had to come from California - there were no production companies in DC to do that. They have to know everything from lyrics to times, all that stuff, if it's going to be televised.

Songfacts: Does the President being there add any pressure?

Booker T: Not for the Obamas. He came down to the rehearsals. They made us very comfortable.

There was more security for Obama. The Clinton people were a little more relaxed about it. It wasn't bad though. Playing for the president is hard, though, because presidents have so much security.

Songfacts: You're on tour doing some Stax revues on other dates. What are you doing on your current tour?

Booker T: I play with a quartet, but there may be some Stax songs with the quartet. We've been changing up the setlist quite a bit for the past few years. My son has been playing with me for the past two years. We're doing some new things, some Bill Withers songs and songs we didn't do previously. People like to hear some of the old MG's instrumentals, so we're doing some of those. We're doing some new compositions, changing it up some. I like to do the MG's staple songs: "Green Onions," "Time is Tight," "Hip-Hug-Her." People really love to hear those.

Songfacts: Those have stood the test of time. Why do you think that is? The groove? The simplicity?Booker T: Yeah, you hit the nail on the head there: the simplicity. Well, the apparent simplicity, I'll put it like that, from the position of the player. "Green Onions" appears to be a simple song, but every time I play it I have to pay attention. I have to remember, and school myself on how the notes go, because it's just not as simple as it sounds.

Songfacts: When you recorded that song, it was not something you thought would be the hit it became, right?

Booker T: Exactly, no. I wasn't thinking about a hit. I was just having fun, playing chord changes I learned in my theory lesson.

Songfacts: And you were quite young at the time.

Booker T: Yeah man, I was 17.

Songfacts: That's pretty young to be in a studio at all, let alone all those Stax records you were on.

Booker T: It was, but I was fortunate. I had been in the studio two years at that point. Stax needed a baritone sax player, because their player, Floyd Newman, was a school teacher. He would be in school weekdays, so they came and got me out of algebra class. I got my baritone sax, went down there and got the job. And I told them I could play piano. So I had been playing in a studio since I was in the 10th grade.

Songfacts: Did you pick up a lot of things being in the studio?

Booker T: Most of the stuff during that time I picked up from the clubs, because I was trying to learn music theory: how to play the notes in my head. And a lot of the studio musicians were the club musicians also. Most of what I learned I took from the clubs to the studio.

Songfacts: What made for the Stax sound?

Booker T: A lot of it came from the lack of sophisticated equipment, and the lack of sophistication in general, to be honest with you. Then there was a concerted effort to be simple, to be accessible. We used to say, "Keep it funky and don't play too many notes" - don't have too many frills in the music. I think that created the Stax sound. The chords were simple and accessible.

Songfacts: When did you start writing songs?

Booker T: It takes some work. I got there on the previous Saturday, and the show was on Friday. It took some rehearsal, but it was fun. His songs are good, and the performers are good. Jakob Dylan sang a song, and Gary Clark Jr. sang a song and a guy from the Eagles. It was good.

Songfacts: You've done a number of those kinds of events. I'm thinking of the Bob Dylan 30th Anniversary Concert at Madison Square Garden in 1992 and at the White House as well.

Booker T: A couple of shows at the White House, yeah.

Songfacts: What are those like to do?

Booker T: If you're the music director, it's a lot of work, but if you're just playing the organ like I was, it can be a lot of fun. I was the music director for the White House shows, so that was Mick Jagger and B.B. King, and a lot of artists from Memphis. There were two shows: a Memphis show, and a tribute to the blues show.

Songfacts: Is there added pressure because of where you are?

Booker T: It's a lot of pre-preparation, because the music changes keys a lot and the arrangements change. And then everything has to be provided. The production company had to come from California - there were no production companies in DC to do that. They have to know everything from lyrics to times, all that stuff, if it's going to be televised.

Songfacts: Does the President being there add any pressure?

Booker T: Not for the Obamas. He came down to the rehearsals. They made us very comfortable.

There was more security for Obama. The Clinton people were a little more relaxed about it. It wasn't bad though. Playing for the president is hard, though, because presidents have so much security.

Songfacts: You're on tour doing some Stax revues on other dates. What are you doing on your current tour?

Booker T: I play with a quartet, but there may be some Stax songs with the quartet. We've been changing up the setlist quite a bit for the past few years. My son has been playing with me for the past two years. We're doing some new things, some Bill Withers songs and songs we didn't do previously. People like to hear some of the old MG's instrumentals, so we're doing some of those. We're doing some new compositions, changing it up some. I like to do the MG's staple songs: "Green Onions," "Time is Tight," "Hip-Hug-Her." People really love to hear those.

Songfacts: Those have stood the test of time. Why do you think that is? The groove? The simplicity?Booker T: Yeah, you hit the nail on the head there: the simplicity. Well, the apparent simplicity, I'll put it like that, from the position of the player. "Green Onions" appears to be a simple song, but every time I play it I have to pay attention. I have to remember, and school myself on how the notes go, because it's just not as simple as it sounds.

Songfacts: When you recorded that song, it was not something you thought would be the hit it became, right?

Booker T: Exactly, no. I wasn't thinking about a hit. I was just having fun, playing chord changes I learned in my theory lesson.

Songfacts: And you were quite young at the time.

Booker T: Yeah man, I was 17.

Songfacts: That's pretty young to be in a studio at all, let alone all those Stax records you were on.

Booker T: It was, but I was fortunate. I had been in the studio two years at that point. Stax needed a baritone sax player, because their player, Floyd Newman, was a school teacher. He would be in school weekdays, so they came and got me out of algebra class. I got my baritone sax, went down there and got the job. And I told them I could play piano. So I had been playing in a studio since I was in the 10th grade.

Songfacts: Did you pick up a lot of things being in the studio?

Booker T: Most of the stuff during that time I picked up from the clubs, because I was trying to learn music theory: how to play the notes in my head. And a lot of the studio musicians were the club musicians also. Most of what I learned I took from the clubs to the studio.

Songfacts: What made for the Stax sound?

Booker T: A lot of it came from the lack of sophisticated equipment, and the lack of sophistication in general, to be honest with you. Then there was a concerted effort to be simple, to be accessible. We used to say, "Keep it funky and don't play too many notes" - don't have too many frills in the music. I think that created the Stax sound. The chords were simple and accessible.

Songfacts: When did you start writing songs?

Jones is partly responsible for the famous "I know, I know, I know" bridge in "Ain't No Sunshine."

Bill Withers planned to fill that in with lyrics, but Jones told him to

leave it as is. Withers, who was a factory worker at the time with no

recording experience, took the advice.

Booker T: That's a

good question. I can remember being a young kid, and pretending to write

songs, but I was really, really young. Maybe 6 years old. I pretended I

was a songwriter. I would put lyrics and words together around the

house, singing to myself. I'm sure none of it was any good, but I had

always seen myself as a songwriter all my life.

Songfacts: What was the first opportunity you had to record one of your songs?

Booker T: You won't believe this. "Green Onions." That was the first time. And that happened by mistake. We got to the studio, and something didn't work with the band before us, and we were supposed to be the backup band. I'm not sure whether they finished early, or whether [label founder and producer] Jim [Stewart] was unhappy with what they were doing, but we ended up with a free studio on a Sunday afternoon.

Songfacts: And you had that melody in your head?

Booker T: Yeah. I had been playing it on piano. I hadn't thought to play it on organ at that time, though. I had been playing it on piano, but I played organ on the previous session, so I was sitting on the organ and played it at the organ, and they liked it on the organ better than on piano.

Songfacts: It defined your role as an organist. It wasn't your main instrument at the time, was it?

Booker T: It did. I got the job at Stax on piano because [Steve] Cropper was the guitar player. I had always played ukulele, clarinet and guitar - that was my main rock 'n' roll instrument. That's what I played at school and at home. I had a Sears Silvertone and I fancied myself as a guitar player, but I never did get that job. Later at Stax I played guitar, but not at first.

Songfacts: Once you had that hit, you stayed at the organ.

Booker T: Well, I was happy at the organ. The first time I saw a Hammond organ I just got a feeling inside about it and I was comfortable. I still am comfortable. Maybe I'm more comfortable at that than any other instrument.

Songfacts: It wasn't a Hammond B-3 on "Green Onions," was it?

Songfacts: What was the first opportunity you had to record one of your songs?

Booker T: You won't believe this. "Green Onions." That was the first time. And that happened by mistake. We got to the studio, and something didn't work with the band before us, and we were supposed to be the backup band. I'm not sure whether they finished early, or whether [label founder and producer] Jim [Stewart] was unhappy with what they were doing, but we ended up with a free studio on a Sunday afternoon.

Songfacts: And you had that melody in your head?

Booker T: Yeah. I had been playing it on piano. I hadn't thought to play it on organ at that time, though. I had been playing it on piano, but I played organ on the previous session, so I was sitting on the organ and played it at the organ, and they liked it on the organ better than on piano.

Songfacts: It defined your role as an organist. It wasn't your main instrument at the time, was it?

Booker T: It did. I got the job at Stax on piano because [Steve] Cropper was the guitar player. I had always played ukulele, clarinet and guitar - that was my main rock 'n' roll instrument. That's what I played at school and at home. I had a Sears Silvertone and I fancied myself as a guitar player, but I never did get that job. Later at Stax I played guitar, but not at first.

Songfacts: Once you had that hit, you stayed at the organ.

Booker T: Well, I was happy at the organ. The first time I saw a Hammond organ I just got a feeling inside about it and I was comfortable. I still am comfortable. Maybe I'm more comfortable at that than any other instrument.

Songfacts: It wasn't a Hammond B-3 on "Green Onions," was it?

Booker T: No, it was an M-3 - half of a B-3. A cut down, spinet model of a B-3.

Songfacts: Are you B-3 entirely now?

Booker T: No, I have an M-3 in my studio again. I favor the sound of the M-3, but none of the organs are practical, so when I play on the road, I have to play what the rental companies have. Sometimes they have an M-3 but very, very rarely.

I think the B-3 became my signature sound because of "Hip Hug-Her" and "Hang 'Em High" and "Time is Tight." Those are all B-3 songs, and they have the Leslie speaker spinning with the choral sound.

Songfacts: So every time you go to a city, somebody has to rent one of those for you?

Booker T: That's the way it is. That all ended in 1992 when the airlines changed their freight fares, and now I don't carry mine any more. They started doing it by weight and it became prohibitive. They used to come out to the house and pick it up and ship it for me. Now they don't do that any more.

Songfacts: Has that caused any problems on the road, where you've had trouble finding one?

Booker T: Yes. There was a Hammond school in Chicago. I think the last guys who attended that school passed away maybe 10 years ago. It's a very difficult instrument to maintain. It's not meant to be moved around. They don't travel well, and there are problems, yes.

Songfacts: What is it about the sound of it that no other instrument can do?

Booker T: Well, because it's a sustained sound as opposed to a piano, and because it has those Leslie cabinets and the horns turn, you can make it sing like a human voice. You can make it sustain louder or softer. You can play more than one note at a time or you can move the notes. I think an organ player can make it sing.

Songfacts: Did anyone try to make an electronic keyboard to emulate that sound?

Booker T: Yes, the process is going on right now. I've been going back and forth with Hammond for I don't know how long in Chicago. They made another prototype and they want me to OK it. I have the manual, which is a digital organ. And to be honest with you, I'm still not sure about it.

Songfacts: There's something about the presence of the B-3 that makes it an imposing instrument to see in concert.

Booker T: Yes. You know, they came up with this thing in 1934 out of automobile parts. Laurens Hammond designed it. He was a clockmaker and an inventor. He was just a special person. And sometimes the first time they do something is the best way. That's the way this is, I think.

Songfacts: Can you see yourself going to a digital version at some point?

Booker T: I'm trying. They've made two or three that I've gone there and played, but I'm still not comfortable with them. I want to be, but I'm not.

Songfacts: You're playing some guitar in live shows now?

Booker T: Yeah. I've been going back to guitar for maybe 30 percent of the show, because a lot of the songs I started with a guitar.

I joke with the audience. I tell them my doctor told me at my age, don't sit on the job for too long, so I get up and play some blues on the guitar. I love playing blues on the guitar. Some of the songs I wrote or was involved with in California, those were guitar songs. "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" or songs when I played a stringed instrument, or William Bell songs, Bill Withers songs.

Songfacts: I see that William Bell was singing one of your songs on the Grammys too.

Booker T: "Bad Sign?" Yeah, we wrote it together. We were partners. He did a good job. He's doing well.

Booker T: Stax was trying to grow as a company and was beginning to record a blues artist, Albert King, who was driving down from East St. Louis and didn't have any music. He needed a song, so they gave me and William the assignment the day before the session to write a song for Albert King. That's what we came up with. He killed it.

Songfacts: You played the Monterey Pop Festival 50 years ago, backing Otis Redding. Did your band play a set there as well?

Booker T: We might have played a couple of songs, but our main job was to back Otis. We may have opened the set with a couple of songs. I played organ and we were backup for Otis.

Songfacts: What do you recall from that event?

Booker T: That was a landmark show. It was the first time we played for that kind of audience. They were so warm and receptive.

There was an indication that the country was changing. We had been in Europe for three weeks, and when we landed in Detroit, we saw hippies for the first time. Otis was nervous and apprehensive about the reception, but it was just extremely warm and successful. It was nice.

Songfacts: Did you see some of the other acts that weekend?

Booker T: We did. We saw some of the acts that night and had a couple of days in town to hang out.

Songfacts: Are you B-3 entirely now?

Booker T: No, I have an M-3 in my studio again. I favor the sound of the M-3, but none of the organs are practical, so when I play on the road, I have to play what the rental companies have. Sometimes they have an M-3 but very, very rarely.

I think the B-3 became my signature sound because of "Hip Hug-Her" and "Hang 'Em High" and "Time is Tight." Those are all B-3 songs, and they have the Leslie speaker spinning with the choral sound.

Songfacts: So every time you go to a city, somebody has to rent one of those for you?

Booker T: That's the way it is. That all ended in 1992 when the airlines changed their freight fares, and now I don't carry mine any more. They started doing it by weight and it became prohibitive. They used to come out to the house and pick it up and ship it for me. Now they don't do that any more.

Songfacts: Has that caused any problems on the road, where you've had trouble finding one?

Booker T: Yes. There was a Hammond school in Chicago. I think the last guys who attended that school passed away maybe 10 years ago. It's a very difficult instrument to maintain. It's not meant to be moved around. They don't travel well, and there are problems, yes.

Songfacts: What is it about the sound of it that no other instrument can do?

Booker T: Well, because it's a sustained sound as opposed to a piano, and because it has those Leslie cabinets and the horns turn, you can make it sing like a human voice. You can make it sustain louder or softer. You can play more than one note at a time or you can move the notes. I think an organ player can make it sing.

Songfacts: Did anyone try to make an electronic keyboard to emulate that sound?

Booker T: Yes, the process is going on right now. I've been going back and forth with Hammond for I don't know how long in Chicago. They made another prototype and they want me to OK it. I have the manual, which is a digital organ. And to be honest with you, I'm still not sure about it.

Songfacts: There's something about the presence of the B-3 that makes it an imposing instrument to see in concert.

Booker T: Yes. You know, they came up with this thing in 1934 out of automobile parts. Laurens Hammond designed it. He was a clockmaker and an inventor. He was just a special person. And sometimes the first time they do something is the best way. That's the way this is, I think.

Songfacts: Can you see yourself going to a digital version at some point?

Booker T: I'm trying. They've made two or three that I've gone there and played, but I'm still not comfortable with them. I want to be, but I'm not.

Songfacts: You're playing some guitar in live shows now?

Booker T: Yeah. I've been going back to guitar for maybe 30 percent of the show, because a lot of the songs I started with a guitar.

I joke with the audience. I tell them my doctor told me at my age, don't sit on the job for too long, so I get up and play some blues on the guitar. I love playing blues on the guitar. Some of the songs I wrote or was involved with in California, those were guitar songs. "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" or songs when I played a stringed instrument, or William Bell songs, Bill Withers songs.

Songfacts: I see that William Bell was singing one of your songs on the Grammys too.

Booker T: "Bad Sign?" Yeah, we wrote it together. We were partners. He did a good job. He's doing well.

Although

Jones co-wrote a number of hits for others, including "I've Never Found

a Girl (To Love Me Like You Do)" for Eddie Floyd and "I Love You More

Than Words Can Say" for Otis Redding, one of his most enduring

compositions is "Born Under a Bad Sign," co-written with William Bell. A hit for Albert King in 1967, Cream recorded it for their third album, Wheels of Fire,

the following year. It was listed by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as

one of the 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll. Others to record it

include Paul Butterfield, Blue Cheer, Etta James, Jimi Hendrix, Rita

Coolidge and even Homer Simpson.

Jones and Bell, whose big hit in 1961 was "You Don't Miss your Water," recorded it as well, Jones with The MG's on their 1968 Soul Limbo album, Bell on his 2016 Grammy-nominated comeback album, This is Where I Live.

Songfacts: That song has become a blues standard. Do you recall how it came about?Jones and Bell, whose big hit in 1961 was "You Don't Miss your Water," recorded it as well, Jones with The MG's on their 1968 Soul Limbo album, Bell on his 2016 Grammy-nominated comeback album, This is Where I Live.

Booker T: Stax was trying to grow as a company and was beginning to record a blues artist, Albert King, who was driving down from East St. Louis and didn't have any music. He needed a song, so they gave me and William the assignment the day before the session to write a song for Albert King. That's what we came up with. He killed it.

Songfacts: You played the Monterey Pop Festival 50 years ago, backing Otis Redding. Did your band play a set there as well?

Booker T: We might have played a couple of songs, but our main job was to back Otis. We may have opened the set with a couple of songs. I played organ and we were backup for Otis.

Songfacts: What do you recall from that event?

Booker T: That was a landmark show. It was the first time we played for that kind of audience. They were so warm and receptive.

There was an indication that the country was changing. We had been in Europe for three weeks, and when we landed in Detroit, we saw hippies for the first time. Otis was nervous and apprehensive about the reception, but it was just extremely warm and successful. It was nice.

Songfacts: Did you see some of the other acts that weekend?

Booker T: We did. We saw some of the acts that night and had a couple of days in town to hang out.

The Monterey International Pop Music Festival,

held June 16-18, 1967 in California, was one of the first big rock

festivals, with seminal performances by The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Janis

Joplin and Otis Redding - all captured in D.A. Pennebaker's 1968 film, Monterey Pop.

The Grateful Dead, Buffalo Springfield, Ravi Shankar, Jefferson

Airplane, Laura Nyro, The Byrds, Moby Grape, Steve Miller Band,

Quicksilver Messenger Service, Country Joe and the Fish, Canned Heat,

Eric Burdon and the Animals, Simon & Garfunkel and The Association

all performed, as did Lou Rawls, Hugh Masekela, The Electric Flag and

the Butterfield Blues Band. Redding's performance, closing the show on

Saturday, proved he could enthrall a wider audience, but six months

later, he died in a plane crash at the age of 26 along with four members

of the Bar-Kays.

Songfacts: Are there other other shows you played back then that stand out for you?

Booker T: The Stax revue in Europe was probably the most prominent that I participated in. Of course, the original performance for me in my life was being a young kid at a kite contest and seeing Al Jackson Jr. playing in his dad's big band in Memphis. That was something that I'll never forget. It's seared in my memory. It was the first time I saw horns on stage. It was the first time I heard live music. And the guy who ended up being my drummer was a young kid playing drums in his dad's band. It's just something about live music seeing it for the first time that just hits you.

Songfacts: Was that in Memphis?

Booker T: That was in Lincoln Park in Memphis. Al Jackson Sr. was the band leader.

There was a Count Basie concert in Chicago that affected me like that a few years later when I was a teenager. I took a train up to Chicago to see his concert and sneaked into a hotel there and heard him play in the ballroom. He had Sonny Payne on drums and I was sitting there in front of Count Basie, hearing that music, hearing him live, playing his arrangements, the horns. There were five brass, five reeds, guitar and upright bass. That was a special concert for me. He was such a special musician and bandleader.

Songfacts: Did you think you'd go into jazz when you were young?

Booker T: That's what you were supposed to do in Memphis if you were studying music and went to music theory. That was what we all thought our calling and legacy would be. I say us, I mean myself and my buddy Maurice White - he was my young musician friend. He ended up trying to do that. He went to play with Ramsey Lewis and the jazz people in Chicago. [White later formed Earth, Wind & Fire.]

But that was what you were supposed to do. You were supposed to follow the footsteps of Frank Strozier, Booker Little, Jack McDuff. Those guys that played a little blues, maybe with B.B. King, but ultimately, they studied classical and they played jazz. And that's what you were supposed to do.

Songfacts: The soul music you played on is stuff you were inventing as you went along.

Booker T: That's the strange position I was in. You're absolutely right. It didn't really exist like that until we started playing, until they started playing over at Hi [Records]. Al Green and those people, it sort of grew up with us. It sort of originated with us, and that's kind of funny. The music before that was really nightclub blues. Then we started mixing it with some rockabilly and some country and some funk at Stax with Cropper and Dunn and those musicians - white musicians from east Memphis.

Yeah, it was strange. And of course, there was Sam Cooke and some of the gospel groups that evolved into soul groups when they left the church. The Soul Stirrers. But they were offsprings of gospel groups.

Booker T: The Stax revue in Europe was probably the most prominent that I participated in. Of course, the original performance for me in my life was being a young kid at a kite contest and seeing Al Jackson Jr. playing in his dad's big band in Memphis. That was something that I'll never forget. It's seared in my memory. It was the first time I saw horns on stage. It was the first time I heard live music. And the guy who ended up being my drummer was a young kid playing drums in his dad's band. It's just something about live music seeing it for the first time that just hits you.

Songfacts: Was that in Memphis?

Booker T: That was in Lincoln Park in Memphis. Al Jackson Sr. was the band leader.

There was a Count Basie concert in Chicago that affected me like that a few years later when I was a teenager. I took a train up to Chicago to see his concert and sneaked into a hotel there and heard him play in the ballroom. He had Sonny Payne on drums and I was sitting there in front of Count Basie, hearing that music, hearing him live, playing his arrangements, the horns. There were five brass, five reeds, guitar and upright bass. That was a special concert for me. He was such a special musician and bandleader.

Songfacts: Did you think you'd go into jazz when you were young?

Booker T: That's what you were supposed to do in Memphis if you were studying music and went to music theory. That was what we all thought our calling and legacy would be. I say us, I mean myself and my buddy Maurice White - he was my young musician friend. He ended up trying to do that. He went to play with Ramsey Lewis and the jazz people in Chicago. [White later formed Earth, Wind & Fire.]

But that was what you were supposed to do. You were supposed to follow the footsteps of Frank Strozier, Booker Little, Jack McDuff. Those guys that played a little blues, maybe with B.B. King, but ultimately, they studied classical and they played jazz. And that's what you were supposed to do.

Songfacts: The soul music you played on is stuff you were inventing as you went along.

Booker T: That's the strange position I was in. You're absolutely right. It didn't really exist like that until we started playing, until they started playing over at Hi [Records]. Al Green and those people, it sort of grew up with us. It sort of originated with us, and that's kind of funny. The music before that was really nightclub blues. Then we started mixing it with some rockabilly and some country and some funk at Stax with Cropper and Dunn and those musicians - white musicians from east Memphis.

Yeah, it was strange. And of course, there was Sam Cooke and some of the gospel groups that evolved into soul groups when they left the church. The Soul Stirrers. But they were offsprings of gospel groups.

Songfacts: It must be gratifying for you to have helped create the Stax sound, and have it be so strong today.

Booker T: You know, Roger, it was unbelievable good fortune to be born there, even if nothing had happened like it did, because it was such a rich field to grow in - to learn the chords, to play with the musicians, to get the opportunities to play. Just the atmosphere there, the schools, the horns that were available to me. When I was nine years old I had my hands on an oboe - I was playing oboe in the school orchestra. It was such good fortune.

Songfacts: Do you think kids have less of an opportunity to do that today?

Booker T: So much so that I'm working with the recording academy to just give money right to a school in LA, right to a school in Kansas City. Kids don't have the instruments, and they don't have the teachers like we did. I don't know what's happened with the legislators around the country, but they just have not made that a priority like it was back then.

Songfacts: You've played with a lot of younger musicians, getting Grammys for albums you've recorded with The Roots and Drive-By Truckers. How did those come about?

Booker T: A lot of my early recordings in Memphis were listened to by a lot of bands and practically every band I've worked with in the recent past has been someone who grew up with that music or their parents did, so they know me.

In the case of the Drive-By Truckers, Patterson Hood, he just felt like he knew me because his dad listened to the music and his dad had played music that was very similar. [His dad is David Hood, one of the famous Swampers responsible for the Muscle Shoals sound.] So when we went into the studio, they felt like they knew me.

And the same with The Roots in New York City. Questlove and his guys, they listened to The Meters and they listened to Booker T. & the M.G.'s when they were young, so they felt like they knew me when we went into the studio.

Songfacts: Is it fun to get in the studio with those guys?Booker T: It is, yes. It's great. The new ideas and the fresh energy is amazing. I'm really experiencing that with my son Ted now. he just left here yesterday. We've been working on some new stuff up here. The fresh energy - it's amazing to compare their energy and my energy when I was their age. And they're so much more inventive and quick, because they have a richer legacy to grow on than I did.

Songfacts: Are you working on a new album now?

Booker T: Yes, with my son, and for myself. And working on the road with the four-piece. One thing I'm doing with the four-piece is I'm teaching them the old MG's songs and I'm also working on the Stax revue. That's just some wonderful music that we're beginning to present again to the public - Otis Redding songs, Sam & Dave, Wilson Pickett, Eddie Floyd - so much good music there. Jean Knight from Stax. But yeah, there's a lot to do. Writing a book.

Songfacts: You're not slowing down at all?

Booker T: Not at this point. I don't really understand it yet.

June 13, 2017.

Further reading:

Booker T: You know, Roger, it was unbelievable good fortune to be born there, even if nothing had happened like it did, because it was such a rich field to grow in - to learn the chords, to play with the musicians, to get the opportunities to play. Just the atmosphere there, the schools, the horns that were available to me. When I was nine years old I had my hands on an oboe - I was playing oboe in the school orchestra. It was such good fortune.

Songfacts: Do you think kids have less of an opportunity to do that today?

Booker T: So much so that I'm working with the recording academy to just give money right to a school in LA, right to a school in Kansas City. Kids don't have the instruments, and they don't have the teachers like we did. I don't know what's happened with the legislators around the country, but they just have not made that a priority like it was back then.

Songfacts: You've played with a lot of younger musicians, getting Grammys for albums you've recorded with The Roots and Drive-By Truckers. How did those come about?

Booker T: A lot of my early recordings in Memphis were listened to by a lot of bands and practically every band I've worked with in the recent past has been someone who grew up with that music or their parents did, so they know me.

In the case of the Drive-By Truckers, Patterson Hood, he just felt like he knew me because his dad listened to the music and his dad had played music that was very similar. [His dad is David Hood, one of the famous Swampers responsible for the Muscle Shoals sound.] So when we went into the studio, they felt like they knew me.

And the same with The Roots in New York City. Questlove and his guys, they listened to The Meters and they listened to Booker T. & the M.G.'s when they were young, so they felt like they knew me when we went into the studio.

Songfacts: Is it fun to get in the studio with those guys?Booker T: It is, yes. It's great. The new ideas and the fresh energy is amazing. I'm really experiencing that with my son Ted now. he just left here yesterday. We've been working on some new stuff up here. The fresh energy - it's amazing to compare their energy and my energy when I was their age. And they're so much more inventive and quick, because they have a richer legacy to grow on than I did.

Songfacts: Are you working on a new album now?

Booker T: Yes, with my son, and for myself. And working on the road with the four-piece. One thing I'm doing with the four-piece is I'm teaching them the old MG's songs and I'm also working on the Stax revue. That's just some wonderful music that we're beginning to present again to the public - Otis Redding songs, Sam & Dave, Wilson Pickett, Eddie Floyd - so much good music there. Jean Knight from Stax. But yeah, there's a lot to do. Writing a book.

Songfacts: You're not slowing down at all?

Booker T: Not at this point. I don't really understand it yet.

June 13, 2017.

Further reading:

Stax Today

Interview with Bill Withers

Booker's official site

During the 1960s there was a golden age of soul music in America. Some of the greatest songs from that era came from the Stax

Recording Studio in Memphis, Tennessee. A short list of artists who

recorded there could include Otis Redding, Rufus Thomas, Sam & Dave

and the instrumental band led by Hammond organist, Booker T.

Jones—Booker T. And The M.G.s.

Not only did Booker T. and his band have hit records of their own, they backed up many of the Stax/Volt soul singers. So we were honored to have Booker T. Jones visit KPLU for a solo organ/vocals studio session.

In conversation with jazz host, Mary McCann, Booker T. talked about his early days in the music business (he had his first hit record, Green Onions, when he was 17) and all the great musicians he’s worked with over the years and his love of fast cars. He also gave us solo renditions of 4 of his compositions: Green Onions, Down In Memphis, ’66 Impala (from his most recent recording) and Born Under A Bad Sign, which he wrote for Albert King … and which has gone on to become a blues classic.

You can also find our Studio Sessions available as a video podcast in iTunes.

The link can be found here: https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/kplu-studio-sessions-video/id657517777

I know it’s hard to do, but admit it: those Booker T. & the MG’s records are kinda corny. Yes, yes, they’re fun, they’re groovy, they’re funky, and they’re slathered with so much Memphis-style sauce, it wouldn’t be hard to mistake ‘em for a dish at Payne’s BBQ. But still, those Beatles covers, that Rascals cover, hell, even “Green Onions” … they’re all just kinda corny in a lighthearted, we-cracked-the-bottle-open-and-this-is-what-poured-out kinda way. This is an observation that nobody likes to make, mainly because it casts an aspersion on the World’s Best House Band, the guys that defined the Stax take on Memphis soul in the ‘60s. But I don’t think the band would mind; they knew that the rock-solid grooves they were laying down behind the likes of Isaac Hayes and Otis Redding were the meat and potatoes; “Green Onions” was just a garnish.

Booker T. Jones’ recent solo work, however, is anything but corny. His last solo record — 2009’s Potato Hole — was a tour de force of gritty, twangy blues on which he completely and appropriately overshadowed the contributions of the Drive-By Truckers and Neil Young. On The Road from Memphis, Jones ups the collaborator ante: the Roots are the backing band this time around, guests like Sharon Jones and Jim James make appearances, and Gabe Roth (Daptone Records) was brought in to man the boards. And, once again, the real stars here are Jones’ organ hands. Demonstrating a style that’s less concerned with the cheerful melodies and jaunty basslines of the M.G.s’ most famous work, Jones’ sound here is more measured and full-bodied, giving substantial leeway to Questlove’s ferocious, on-the-mark drumming. The organ still leads the way — sometimes in quirky and near-improvisational ways, such as on the fiercely funky “The Hive” — but most of The Road from Memphis sounds like the work of a band that’s spent years together, rather than a leader and a backup band.

The funk here is deep and solid, but what’s most refreshing is how Jones and the Roots never opt for the most obvious breaks or riffs; the noodly, soulful cover of “Crazy” (you knew he’d cover something, right?), the punishingly unpredictable twists and turns of “Harlem House,” and the head-bobbing crunch of “Down in Memphis” all manage to punch your gut with a groove without giving the slightest indication that the compositions are taking anything for granted. Of the 11 tracks on The Road from Memphis, the only real bummer is the treacly hometown homage of “Representing Memphis,” featuring Sharon Jones and The National’s Matt Beringer; instead of burning through the track with Sharon Jones’ fringe-flecked fire or Beringer’s deep-throated melodrama, both guests seem to shy away from the enormity of the job at hand, making the tourist-board-ready tune even more … well, corny.

https://www.keyboardmag.com/artists/booker-t-jones-revitalizes-the-memphis-soul-sound

Booker T Jones Revitalizes the Memphis Soul Sound

Booker is back. The living legend, who with his group

the MGs helped create the Memphis soul sound at Stax Records in the

1960s—and ushered in the idea of racially integrated bands in the

process—has been getting so much well deserved attention of late that it

feels like he never left.

His 2009 comeback Potato Hole, a rock-influenced project

featuring the Drive By Truckers and Neil Young, won the Grammy for Best

Instrumental Album. The phone started ringing off the hook, and one of

those calls was Roots’ drummer Questlove, who then produced Booker’s

2011 album The Road from Memphis. Boom—another Grammy.

Recently, Booker musically directed and played B-3 on PBS’ In Performance at the White House.

The episode, which aired April 16, celebrated Memphis music and

featured artists such as Mavis Staples, Queen Latifah, Ben Harper, and

Justin Timberlake, not to mention one very delighted U.S. President.

Now, Booker T. reaches for new creative heights on Sound the Alarm, a

musical time machine trip through what real soul music should sound

like. Booker co-produced the album with Bobby and Iz Avila of the Avila

Brothers, and collaborations include Mayer Hawthorne, Estelle, Anthony

Hamilton, Sheila E. and Poncho Sanchez, Gary Clark Jr., and Bill

Withers’ daughter Kori. Just before he played two shows at San

Francisco’s Yoshi’s music club—where he not only delivered his

crowd-pleasing B-3 hits but also played guitar and sang in a baritone

that held the audience rapt—I had the privilege of catching up with

Booker about the new record, where he’s been, and where he’s going.

We spoke in 2009 as Potato Hole was being released.

Since, you’ve won two more Grammys and gained a whole a new generation

of listeners. Back in 2009, did you imagine your resurgence being this

huge?

No, I didn’t care about commercial success. I just

wanted to play. But I’ve been fortunate because after the shows—when

very often I meet people—every other person will say, “This is my son”

or “This is my daughter.” They’re bringing their kids, both overseas and

here. Some of them are actually very young; some are teenagers,

20-year-olds, so that’s great. It’s kept me going that they’re playing

my records for their kids, who are asking me questions about them.

Sound the Alarm is on the Stax label, which you were a big part of in its early days in Memphis. What can you tell us about its rebirth?

That

was Norman Lear and John Burk at Concord rejuvenating the whole thing.

They were looking to bring me in the whole while, and I didn’t know

that, but now they have. When I walked into the office it was like,

“Where’ve you been?” They really made an effort to make me feel good.

Not that [previous label] Anti- wasn’t good for me, but this is

different.

How did music-directing the PBS White House special come about?

The

producers had seen a show I did and they wanted me to do my thing

there. It turned out to be a formidable task. I’d played at the White

House before, for President Clinton, but the security now is

unbelievable. Ken Ehrlich’s production company brought all their people

and gear from the West Coast, so it was pretty huge. Big cables running

into the east room, plus the musical equipment, but it ended up being

fun. President Obama and his wife enjoyed the music and all the

congresspeople and senators that came just relaxed and had a good time.

You played President Obama into the room with “Green Onions.” Who’s idea was that?

It

was his idea. We’d played a fundraiser in San Francisco a few years

back. The President walked into the room, I played “Green Onions,” and

he said, “I want to make that the new ‘Hail to the Chief.’” [Laughs.]

To you, what is the Memphis soul sound as contrasted with, say, the Motown sound or New Orleans sound?

Well,

the Memphis sound is something that was too big and broad to capture in

that one-hour show. You had Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis, Al Green . . . just

too much. The show wound up focusing on Stax—I guess because of me—but

it could easily have been four hours long. So much Memphis music got

ignored by the mainstream, whereas the Motown sound was so identifiably

Motown—the Temptations, the Four Tops, Diana Ross and the Supremes, and

you still have kind of basically the same sound. You don’t have the

difference between Elvis Presley and Ann Peebles. Then there was all the

Gospel stuff that started in Memphis that got overlooked, Joe Dukes,

all those people.

Who came out of Memphis that you think should be a lot more recognized than they are?

For

that show I called Bobby Manuel to play rhythm guitar. He’s an example

of undiscovered Memphis talent. Steve Potts, Bobby Manuel, James

Alexander—that was the rhythm section. That’s why the music sounded so

authentic.

Johnny Ace is one of my influences. Ann Peebles. Willie

Mitchell. I wouldn’t be here if Willie didn’t play. He was my very

first mentor. That’s how I got to meet [founding MGs drummer] Al Jackson

Jr. I was playing bass and Al was behind me and Willie was there. Plus,

he paid me some money! [Laughs.] Willie is in the Memphis

Music Hall of Fame, but he should be in a national hall of fame. He’s

done so much for music just by mentoring young musicians. He’s like

Quincy Jones, who will spend his own money to bring a young musician up.

He did that for me.

How did meeting Quincy Jones come about?

He’d

heard “Green Onions” and invited me to New York and took me downtown to

these clubs. That was the first time I’d heard music played like

that—the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Band, in 1962 or ’63. When I went to

California and was trying to write music for the film Uptight,

he showed me how to coordinate beats per minute with frames per second.

At that time we had to because everything was on 35-millimeter film and

to edit a soundtrack to the picture, you calculated your tempo by the

number of frames per second. Quincy sent me those charts. He was just a

generous guy. I was so glad when he was inducted into the Rock and Roll

Hall of Fame. Sometimes people just have to give to young people that

don’t have. Willie Mitchell was like that. I wouldn’t be here had it not

been for him.

On that topic, is there any new musician on your radar?

The

guitarist, Gary Clark Jr. We were doing a demo for iTunes at Apple in

Cupertino. I hear this music coming from downstairs. It’s Gary and a

drummer, and I go down there and give him my phone number and I tell

him, “If you need anything, call me.” He’s so humble. He was already a

star and I had no idea. But I found out that he was from Austin and that

he’d played with all the guys down at Clifford Antone’s blues club. [Clark plays on the track “Austin Blues” on Sound the Alarm. —Ed.]

You

performed with legends like Mavis Staples at the White House event, and

also with Justin Timberlake. What impression did he make on you?

Justin

is a true Memphis musician. He had the vibe, and the communication was

easy, with no need for many words. He’s a true professional. You know,

he comes from a part of Memphis that I wouldn’t have known about in the

early days, and he wouldn’t have known about mine. Memphis was

segregated. It was a minor miracle that Steve Cropper and “Duck” Dunn

and myself and all of us came together at Stax on McLemore Avenue. That

geographical juncture happened because Whites were moving out and Blacks

were moving in. Don Nix was another guy who tried to mix it up with the

Blacks and the Whites, kind of like Cropper.

A reader wrote on

our Facebook page that you play with great economy—few notes but tons of

expression—and wanted to know about this approach.

It comes from what I did right and what I did wrong for my childhood

music teacher, Mrs. Elmertha Cole. Her paradigm for music started with

Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. You talk about minimalism—Bach is

the essence of musical sentences that use as few “letters” as possible.

Not only is this coming from an entertaining standpoint, but also a

spiritual standpoint. That has stuck with me from ten or 11 years old:

Don’t play any note unless it has some type of significance. There was

my mother, too. She was a very soulful and emotive piano player. She

played Gospel music and Chopin—everything classical but also church

music. But Mrs. Cole is the one that taught me organ, so I owe her all

that. Mrs. Cole wasand still is my indicator of what’s right and what’s wrong in music.

Mrs. Cole’s house was also where you first heard the Hammond, correct?

Yes,

and again, the first notes I heard her play on organ were Bach. An

interesting thing about the Hammond is the dissent between Laurens

Hammond and Don Leslie—because the organ and the speaker were a marriage

made in heaven. The long, sustained note on the organ doesn’t mean

anything until the Leslie kicks in and starts to move the air. That’s

historic.

Some songs on Sound the Alarm are very

contemporary. Others sound so vintage they could be from the Stax

archives. Was this conscious or did it just come out of the different

collaborators?

It was the collaborations—Iz Avila and his

Akai MPC, for one thing. You know, he’s a Stax disciple. I think the

record sounds like the natural evolution of Stax—like where Stax

should’ve gone had not it had the hiccup of bankruptcy and all that.

It’s picking up where it left off.

On the title track to Sound the Alarm, how did working with Mayer Hawthorne come about?

I

was introduced to Mayer by Daryl Hall up at his house. It was an

eye-opening day for me to find a young, blue-eyed soul guy that could

hang with Daryl Hall. I was just shocked. We rehearsed those songs maybe

one time.

What was the sample at the beginning of someone saying that you “need no introduction”?

That’s

Albert King. That was from a show in Los Angeles that we did just

before the Watts riots. Iz Avila threw that in there with his MPC.

“Fun” is perhaps the most vintage-sounding track. What was its inspiration?

“Fun”

was one of the Avila Brothers’ ideas. It’s different from anything on

the album. It’s very much a ’60s song. It’s like a Four Tops type of

thing.

Then you have a big contrast, “Can’t Wait”

featuring Estelle, which is almost an electronica track. Did you play

any synths on it?

I did some of the background, but that

sound—I don’t know if you can tell, but it’s actually a Hammond. It’s

like what I did on “Melting Pot,” where the reverb appears.

What’s the technique?

I

get the reverb going and then I back off on the expression pedal. I

play, bring the volume back, and then you hear the reverb sound—the

tail—without the sound at the start. So that makes the chords a little

“behind.” For that song, if I play the chords on time it doesn’t sound on time.

Another unusual Hammond tone is on the Kori Withers duet “Watch You Sleeping.” The motif is sort of Japanese. . . .

It’s all fourths. One little drawbar—the eight-foot—and real soft. But I’m going like this. [Plays fourths with both hands in contrary motion.] To me it sounded gentle, like the subconscious, like sleeping. That was how the lyrics came.

How did you and your son Ted get together on “Father Son Blues”?

We

had an apartment in West Hollywood, and one day, Ted was practicing

guitar. He loves Joe Bonamassa and would watch him on TV, and one day I

thought, from the bedroom, that I was hearing Joe on the TV, but it was

actually Ted! That’s when I decided to put this tune together for him,

as he’s a great player and he approaches guitar like training for a

sport. Basically it’s just me trying to teach my son what it was like in

1950 to play the blues in a club. The basic riff in that song was what

we played on Beale Street all night long!

It’s also the tune where you stretch out the most on the organ.

I know—even though it’s in the key of B. How weird is that? How do you play blues in B? The blues scale doesn’t fall under the fingers well in B.

Why B, then?

It sounds great. It rings. That’s why I used Db for Albert King for “Born Under a Bad Sign” as opposed to F or even C. Db is like Gb,

those certain keys. They’re hard to play in but you get that sound.

Different instruments ring better in certain keys. There’s something

about the way the world is made, the way the keys go through the air.

Some are more effective than others.

What’s in your home studio these days?

I

still have my Hammond B-3, of course. Ableton, Pro Tools, and Sibelius

in the computer, and I’m using a Novation [SL Mk. II] controller. We

just moved, and I haven’t really got it set up yet.

Do you tour with a B-3 or portable, or is it on your rider for backline?

I

have a New B-3 Portable and Leslie 3300 speaker—I love the 3300, by the

way—but these days I’m playing so many places that I have to rent at

every place. We might jump from Vancouver to Paris. I’ve stayed on the

player’s side of the organ so much that I’ve only just gotten around to

studying how it works, but vintage B-3s need to be fixed more and more

now, even the good ones. So I’ve been opening up Beauty and the B by Mark Vail and studying how the instrument works.

Are there any songs where you prefer playing piano rather than organ?

I

wanted to play Leon Russell’s “A Song For You” the other day for my

wife Nan. Leon has these thirds and sixths at the beginning, and on the

organ, you don’t have the ring that you have on the piano. The intro to

“A Song For You” on the organ is just not as effective. You can do it

and walk down and you get to that final minor chord in the intro, and

then you start to sing. The emotional effect is lost on the Hammond if

you do that. But then you can do things on the organ that you can’t do

on the piano.

Did you also encounter Leon Russell early in your career?

When

I had just gone from Memphis to California, emotional because I’d left

my home, he was the first person I met. He was generous, just like

Quincy Jones: “Come to my house, use the studio, use the piano.” He’s

completely open and he’s writing all these song and he’s the session

player of the century. He was playing on everything—and he just

let musicians stay at his house. He was working on “A Song For You”

when I was around, so the song still means so much to me. I’ll probably

do it tomorrow night at the gig. Leon is just a national treasure.

The

Hammond was once sold as a pipe organ alternative for smaller churches.

Did you develop any organ technique playing in church as a young man?

I

did play in church. There was nobody else to play for them. I had to be

there, in a suit and tie. The church was just a couple blocks from the

club, too. I’d leave the club at 4 A.M. and get to Bible class at 9. My

church, though, was an African-American Methodist church where the

service was more formal compared to things like the Sanctified Church.

We played classical religious music in the church—hymns.

What type of project would you like to do next?

Well,

if you walk into my studio, you’ll see the score for Beethoven’s Ninth