SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2018

VOLUME FIVE NUMBER THREE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

DOROTHY ASHBY

(April 21-27)

MILFORD GRAVES

(April 28-May 4)

LOUIS JORDAN

(May 5-11)

JOSEPH JARMAN

(May 12-18)

OTIS BLACKWELL

{May 19-25)

MARION BROWN

(May 26-June 1)

THE ROOTS

(June 2-8)

CHARLIE PATTON

(JUNE 9-15)

STEFON HARRIS

(JUNE 16–22)

MEMPHIS MINNIE

(June 23-29)

HAROLD LAND

(June 30-July 6)

WILLIE DIXON

(July 7--13)

Marion Brown

(1931-2010)

Artist Biography by Thom Jurek

Alto saxophonist Marion Brown

was an underappreciated hero of the jazz avant-garde. Committed to

discovering the far-flung reaches of improvisational expression, Brown nonetheless possessed a truly lyrical voice but was largely ignored in discussions of free jazz of the '60s and '70s. Brown came to New York from Atlanta in 1965. His first session was playing on John Coltrane's essential Ascension album. He made two records for the ESP label in 1965 and 1966 -- Marion Brown Quartet and Why Not? -- and also played on two Bill Dixon soundtracks. It wasn't until his defining Three for Shepp (including Grachan Moncur III and Kenny Burrell)

on the Impulse! label in 1966 that critics took real notice. This set,

lauded as one of the best recordings of that year, opened doors for Brown (temporarily) to tour. He didn't record for another two years because of extensive European engagements, and in 1968 issued Porto Novo (with Leo Smith) on the Black Lion label. In 1970, Brown recorded Afternoon of a Georgia Faun for the ECM label, his second classic. This date featured Anthony Braxton, Andrew Cyrille, Bennie Maupin, Jeanne Lee, and Chick Corea, among others. In 1973, he cut his second Impulse! session, Geechee Recollections, with Leo Smith. Brown

registered at Wesleyan University in the mid-'70s, studying ethnic

instruments and black fife-and-drum corps music and maintained a regular

recording schedule. He also recorded with Gunter Hampel in the late '70s and '80s, as well as composer Harold Budd on his Pavilion of Dreams album (issued on Brian Eno's Obscure label), Steve Lacy in 1985, Mal Waldron

in 1988, and many others. There are numerous duet and solo recordings

that may or may not be sanctioned. Due to health problems, Brown

didn't record after 1992. After the turn of the millennium he lived for

a while at a New York nursing home before moving to an assisted living

facility in Florida. Marion Brown died in October of 2010.

N.Y. / Region

Marion Brown, Free-Jazz Saxophonist, Dies at 79

Marion

Brown, a saxophonist whose lyrical, low-key style made him a

distinctive presence in the high-energy jazz avant-garde of the 1960s

and ’70s, died Monday in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. He was 79.

His

death, in a hospice, was confirmed by his son, Djinji. Mr. Brown had

been treated for a variety of illnesses in recent years and had been

living in an assisted-living home in Hollywood, Fla.

Mr.

Brown, whose main instrument was alto saxophone, was a key figure in

the movement that came to be known as free jazz, an approach to

improvisation that challenged conventional notions of harmony, rhythm,

pitch and pretty much everything else.

He first attracted wide attention as a member of the 11-piece ensemble featured on John Coltrane’s

influential and controversial album “Ascension.” That album, recorded

in 1965 and released in 1966, signaled Coltrane’s commitment to free

jazz and, while it drew as much criticism as praise, helped give

legitimacy to what had been largely an underground phenomenon.

By

that time Mr. Brown had been participating in the avant-garde for a

while, having worked with the tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp (who

introduced him to Coltrane), the idiosyncratic pianist and bandleader

Sun Ra and other musicians who were pushing the boundaries of jazz. Mr.

Brown soon began leading sessions for ESP-Disk, ECM, Impulse and other

labels, developing a style as melodic as it was adventurous.

His

most notable recordings were a trilogy of albums — “Afternoon of a

Georgia Faun,” “Geechee Recollections” and “Sweet Earth Flying” — on

which he evoked his Georgia roots. Reviewing all three for The New York

Times in 1974, Robert Palmer called them “an exemplary demonstration of

how, in the new jazz which is primarily a legacy of the 1960s, a

thoughtful artist can explore a ‘subject’ through a variety of

techniques, processes and formal disciplines.”

Marion

Brown Jr. was born in Atlanta on Sept. 8, 1931. He studied music in

high school and, after serving in the Army and attending Clark College

and Howard University, moved to New York in 1962 and began his musical

career in earnest. In the 1970s he taught African and African-American

music at Bowdoin College and studied ethnomusicology at Wesleyan

University. Despite failing health, he remained intermittently active

into the 21st century.

Mr.

Brown’s marriage to Gail Anderson ended in divorce. In addition to his

son, he is survived by two daughters, Anais St. John and La Paloma

Soria-Brown, and two granddaughters.

A version of this article appears in print on October 24, 2010, on Page A29 of the New York edition with the headline: Marion Brown, 79, Free-Jazz Saxophonist.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/marionbrown

Biography

Marion Brown made his name as an alto saxophonist after mastering clarinet and oboe, and established himself in the forefront of the free jazz movement.

Born in Atlanta, on Sept. 8, 1931, he moved to Harlem as a teenager. In the 50s he studied music at Clark College, Atlanta and law at Howard University, Washington, DC. He spent 18 months playing the clarinet in an army band on the Japanese island of Hokkaido. In 1962 he moved back to New York to play jazz full time, and was mentored by Ornette Coleman. His first musical exposure came with Archie Shepp, and he quickly gained a reputation after playing on John Coltrane's historic “Ascension.”

Brown recorded “Marion Brown Quartet” (’65) and “Why Not?” (’66) for the ESP label, but it was his significant “Three For Shepp” with Grachan Moncur III and Kenny Burrell on the Impulse label in 1966 that solidified his status as a major innovator. His 1970 release of “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun,” has also become a standout in his career.

Brown toured Europe with vibes player Gunter Hampel in the early 70s, made a series of extremely individual records with avant gardists such as Hampel, Leo Smith, Muhal Richard Abrams and Steve McCall, and led his own groups into the new millennium, although health problems have limited his scope.

He has continued to investigate African American ethnomusicology both musically and academically, and recordings have included the solo “Recollections: Ballads And Blues For Alto Saxophone,” and duos with pianist Mal Waldron. He has written a book of essays on his life and music, also titled Recollections, which was published in Germany in 1985. Brown's dry, breathy alto sound and the tenacious logic of his improvisations mark him as a unique player.

Marion Brown, at one time, was a very close friend of mine. It was during the middle-’60s. I had been living in NYC since 1957, when I got out of the Air Force, moving from the far West Side and transitioning to a loft in Chelsea where I could finish working on my book Blues People. We came to end up together in a weird little building on Cooper Square in the upper Bowery. This part of the Bowery has a more colorful sobriquet because it’s just a couple blocks down from historic Cooper Union.

Living in that same building after awhile was a drama school one floor down, Archie Shepp and family a floor under that, and saxophone player Marzette Watts below him. This was before this was the East Village; I guess it was a more homey, less commercial kind of bohemianism. It seemed more of a neighborhood. Right around the corner from the ancient McSorley’s and a few steps from a Bowery bar, the abstract expressionists neutralized the bums out of a place called the Five Spot.

Marion, from the jump, was quiet yet intense. He seemed interested to find out what I, actually, we, the whole of that neighborhood, was doing. But at the same time Marion was the kind of person who told you great stretches of his life every time he asked a question. So I quickly found out about his Georgia birth, his study of music at Clark College in Atlanta, and how he’d then suddenly decided he wanted to go to Howard University and study law.

But this was how Marion’s mind moved, not altogether centered but drawn from one point of interest to another very rapidly. Though, obviously, the love of music was one foundation of his person, his later interest in architecture and painting are not obscure. In fact, it was the burgeoning scene on the Lower East Side that pushed him so deeply into the music at that time; the fact that in that community he was surrounded not just by music but new voices, profound voices. And he could feel that as something important to be involved in.

Marion emerged just as the new music and the new musicians who played it arrived downtown; that point when Coltrane had left Miles and some people were putting him down for being weird and Sonny was practicing on the Williamsburg Bridge. And all of us who were close to the music knew some other stuff was about to go down: about the time a dude name Ornette Coleman and his crew showed at the Five Spot in some colored Eisenhower jackets and let us know, yeh, we had been correct, that some other stuff was afoot. So in the neighborhood, not the radio or television, but in those streets the Yeh went up of something new. Next thing we know, Monk had Trane right next door and we sat in there nightly to dig the new learning.

But that also meant Cecil Taylor (who had showed up even earlier, further transforming the bum’s bar) and the host of young dudes who followed. In an essay dated 1961, “The Jazz Avant Garde,” I named a bunch of folks who had just shown up. Reeds: Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Wayne Shorter, Oliver Nelson. Brass: Don Cherry, Freddie Hubbard. Percussion: Billy Higgins, Ed Blackwell, Dennis Charles, Earl Griffith (vibes). Bass: Wilbur Ware, Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, Buell Neidlinger. Piano: Cecil Taylor. Composition: Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Wayne Shorter, Cecil Taylor. There’s a mea culpa at the end of the piece talking about how some of those named vanished shortly after. But basically this is the “new” at the beginning of the ’60s, and the class that Marion Brown sought to enter. But see, in this essay neither Pharoah Sanders nor Albert Ayler nor Sun Ra had really made the scene yet, so Marion must have showed just after this.

You can imagine then the sweep of charismatic magnetism such heavy entrances must have wired up, so that young Marion appearing, actually at a center of that newly rising turbulence, was deeply affected. I met Pharoah Sanders, who was called then “Little Rock,” walking down the street. He told me his name and I heard Pharoah and it’s been that ever since. Albert showed up one night just like Marion with a dude named Black Norman. Marion was witnessing these mighty comings, and we spent hours and hours talking about the scene and how the major problem of the day-no venues-was to be resolved.

That ushered in the period I wrote about called “Loft & Coffee Shop Jazz.” The old club owners didn’t want to hear the new music so new venues had to be found-and they were. Many times they were the very lofts we lived in. It was in those kinds of lofts and coffee shops that Marion Brown rose to prominence, not in the club world: places like 27 Cooper Square, White Whale, Playhouse Coffee Shop (we first heard of Sun Ra there), Avital, Harouts, the Speakeasy, the Ninth Circle, the Cinderella Club, the Center, Maidman’s and, later, Ladies’ Fort.

Marion got one of his first chances to record through Archie Shepp, because Marion would see Shepp every time he came over to our house-learning from all of us and being drawn to Shepp’s then-brand-new outrageous funk. Marion was “raised” in this warhead of the avant-garde, and it seemed everything was possible!

Marion played on Shepp’s Fire Music (’65), steadily making his way up among the young names in the ’60s, and by that association was one of the privileged sidemen on Trane’s explosive Ascension (’65), which was the ultimate recognition that the new learning was here. It was also at a session, The New Wave in Jazz, which featured Trane, Shepp, Ra, Tolliver, Hutcherson and many of the other new musicians, that I last saw Marion.

That was the year of Malcolm X’s murder; a month later I was in Harlem. The next I heard of Marion he was in Europe. Later I heard he was back in the U.S., and every once in a while I’d hear about some of the things he was doing; still later I heard he’d gotten ill. But I never saw him again.

http://variety.com/2010/music/news/alto-saxophonist-marion-brown-dies-1118026100/

Music Reporter @CeeMo100

Alto saxophonist Marion Brown, a leading jazz avant gardist and

music educator, died Oct. 18 in Hollywood, Fla. He was believed to be

79, though some sources list his age as 75.

Beginning with LPs for the experimental ESP-Jazz label in the late ’60s, Brown worked as a leader through the early ’90s. His best-known albums included “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun” (ECM, 1970) and “Geechee Recollections” (Impulse, 1973).

He taught at such universities as Brandeis and Amherst during the ’70s, and earned a master’s degree in ethnomusicology from Wesleyan. In later years, he developed a parallel career as a graphic artist. https://www.allaboutjazz.com/marion-brown-why-not-by-clifford-allen.php

https://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2010/10/19/130669448/marion-brown

As I see it, Georgia didn't open up to me until I left home. Don't be fooled: Atlanta suburbs are not the Old South. Neighborhoods are named for the farmers who once plowed the soil, and sweet-tea-sipped accents are at least five counties away. Not until I moved to Athens, Ga., and eventually to Washington, D.C., did I see Georgia for the weird and surreal place it was and is.

Marion Brown was born Sept. 8, 1935 in Atlanta (or 1931, depending on who you ask). He stayed in Georgia long enough to see the Confederate stars and bars added to the state flag at the height of desegregation. His travels took him to New York, where Archie Shepp and Ornette Coleman encouraged Brown to develop his talents. The alto saxophonist appeared on John Coltrane's Ascension and Shepp's Fire Music, his reflective and sometimes playful tone an ear-bending foil to the fire-breathing of his peers.

After time in Paris and touring Europe, Brown returned to Atlanta, where a surge of creativity flowered like dogwood: Beautiful and bright, but burnt at the tips. Inspired by the stark Southern reflections in Jean Toomer's epic work Cane, and his own birthplace enlightenment, Marion Brown released a trilogy of records dedicated to Georgia: Afternoon of a Georgia Faun (1970), Geechee Recollections (1973) and Sweet Earth Flying (1974). (The latter two remain out of print.) Adorned with pastoral poetry and folksong, these albums evoke a Southern experience.

At a certain point of reflection and education, I became a conflicted Southerner. I sought the harmony of my past, the understanding of a history I adopted as my own. (My family moved to Georgia at age seven, but "American by birth, Southern by the grace of God," we say). Like its soul food, Georgia's history is lush and cooked down, yet brutal in its lumbering wake. It's near impossible to reconcile what came and what is to come with a state that only in the last decade removed the Dixie from its flag. It is our heritage, yes. And in an odd way, those of us who've struggled with those issues are proud still.

There is hurt in Marion Brown's trilogy. How could there not be? Jean Toomer wrote of "Thunder blossoms gorgeously above our heads [...] Bleeding rain / Dripping rain like golden honey." Beautiful and terrifying: In its unique and abstract way, this is how I eventually came to see my home. The quiet, percussive "Afternoon of a Georgia Faun" as a haunting spirit of the swampy urban jungle; the rhythmic dance of "Once Upon a Time (A Children's Tale)" as the celebration of summer; the solo bookends of the Sweet Earth Flying suite, played by Paul Bley (Fender Rhodes) and Muhal Richard Abrams (piano), two soulful and somber blues rendering Georgia dawn and Georgia dusk.

While this Southern trilogy certainly doesn't capture the breadth of Brown's work, it's a personal statement that speaks beyond music. It should be part of the Southern canon along with The Color Purple, Coca-Cola, Rev. Howard Finster, James Brown, the Stone Mountain laser show and Sid Bream's slide into home plate.

Multiple sources are reporting that Brown died in his assisted living community in Hollywood, Fl. this past weekend. Out of sight for the past three decades due to illness, Marion Brown was a musical spirit guide to those lucky to find him. Cradled between Anthony Braxton sides at WUOG was Afternoon of a Georgia Faun for me to discover in 2004. Listening then as now, I'm taken off I-85 and down the winding, unlit roads of 441, hearing the South in moving fabric. I'm home.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/a-fireside-chat-with-marion-brown-marion-brown-by-aaj-staff.php?page=1

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/marionbrown

Marion Brown

Marion Brown

BiographyMarion Brown made his name as an alto saxophonist after mastering clarinet and oboe, and established himself in the forefront of the free jazz movement.

Born in Atlanta, on Sept. 8, 1931, he moved to Harlem as a teenager. In the 50s he studied music at Clark College, Atlanta and law at Howard University, Washington, DC. He spent 18 months playing the clarinet in an army band on the Japanese island of Hokkaido. In 1962 he moved back to New York to play jazz full time, and was mentored by Ornette Coleman. His first musical exposure came with Archie Shepp, and he quickly gained a reputation after playing on John Coltrane's historic “Ascension.”

Brown recorded “Marion Brown Quartet” (’65) and “Why Not?” (’66) for the ESP label, but it was his significant “Three For Shepp” with Grachan Moncur III and Kenny Burrell on the Impulse label in 1966 that solidified his status as a major innovator. His 1970 release of “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun,” has also become a standout in his career.

Brown toured Europe with vibes player Gunter Hampel in the early 70s, made a series of extremely individual records with avant gardists such as Hampel, Leo Smith, Muhal Richard Abrams and Steve McCall, and led his own groups into the new millennium, although health problems have limited his scope.

He has continued to investigate African American ethnomusicology both musically and academically, and recordings have included the solo “Recollections: Ballads And Blues For Alto Saxophone,” and duos with pianist Mal Waldron. He has written a book of essays on his life and music, also titled Recollections, which was published in Germany in 1985. Brown's dry, breathy alto sound and the tenacious logic of his improvisations mark him as a unique player.

MARION BROWN

AMIRI BARAKA

Marion Brown, at one time, was a very close friend of mine. It was during the middle-’60s. I had been living in NYC since 1957, when I got out of the Air Force, moving from the far West Side and transitioning to a loft in Chelsea where I could finish working on my book Blues People. We came to end up together in a weird little building on Cooper Square in the upper Bowery. This part of the Bowery has a more colorful sobriquet because it’s just a couple blocks down from historic Cooper Union.

Living in that same building after awhile was a drama school one floor down, Archie Shepp and family a floor under that, and saxophone player Marzette Watts below him. This was before this was the East Village; I guess it was a more homey, less commercial kind of bohemianism. It seemed more of a neighborhood. Right around the corner from the ancient McSorley’s and a few steps from a Bowery bar, the abstract expressionists neutralized the bums out of a place called the Five Spot.

Marion, from the jump, was quiet yet intense. He seemed interested to find out what I, actually, we, the whole of that neighborhood, was doing. But at the same time Marion was the kind of person who told you great stretches of his life every time he asked a question. So I quickly found out about his Georgia birth, his study of music at Clark College in Atlanta, and how he’d then suddenly decided he wanted to go to Howard University and study law.

But this was how Marion’s mind moved, not altogether centered but drawn from one point of interest to another very rapidly. Though, obviously, the love of music was one foundation of his person, his later interest in architecture and painting are not obscure. In fact, it was the burgeoning scene on the Lower East Side that pushed him so deeply into the music at that time; the fact that in that community he was surrounded not just by music but new voices, profound voices. And he could feel that as something important to be involved in.

Marion emerged just as the new music and the new musicians who played it arrived downtown; that point when Coltrane had left Miles and some people were putting him down for being weird and Sonny was practicing on the Williamsburg Bridge. And all of us who were close to the music knew some other stuff was about to go down: about the time a dude name Ornette Coleman and his crew showed at the Five Spot in some colored Eisenhower jackets and let us know, yeh, we had been correct, that some other stuff was afoot. So in the neighborhood, not the radio or television, but in those streets the Yeh went up of something new. Next thing we know, Monk had Trane right next door and we sat in there nightly to dig the new learning.

But that also meant Cecil Taylor (who had showed up even earlier, further transforming the bum’s bar) and the host of young dudes who followed. In an essay dated 1961, “The Jazz Avant Garde,” I named a bunch of folks who had just shown up. Reeds: Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Wayne Shorter, Oliver Nelson. Brass: Don Cherry, Freddie Hubbard. Percussion: Billy Higgins, Ed Blackwell, Dennis Charles, Earl Griffith (vibes). Bass: Wilbur Ware, Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, Buell Neidlinger. Piano: Cecil Taylor. Composition: Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Wayne Shorter, Cecil Taylor. There’s a mea culpa at the end of the piece talking about how some of those named vanished shortly after. But basically this is the “new” at the beginning of the ’60s, and the class that Marion Brown sought to enter. But see, in this essay neither Pharoah Sanders nor Albert Ayler nor Sun Ra had really made the scene yet, so Marion must have showed just after this.

You can imagine then the sweep of charismatic magnetism such heavy entrances must have wired up, so that young Marion appearing, actually at a center of that newly rising turbulence, was deeply affected. I met Pharoah Sanders, who was called then “Little Rock,” walking down the street. He told me his name and I heard Pharoah and it’s been that ever since. Albert showed up one night just like Marion with a dude named Black Norman. Marion was witnessing these mighty comings, and we spent hours and hours talking about the scene and how the major problem of the day-no venues-was to be resolved.

That ushered in the period I wrote about called “Loft & Coffee Shop Jazz.” The old club owners didn’t want to hear the new music so new venues had to be found-and they were. Many times they were the very lofts we lived in. It was in those kinds of lofts and coffee shops that Marion Brown rose to prominence, not in the club world: places like 27 Cooper Square, White Whale, Playhouse Coffee Shop (we first heard of Sun Ra there), Avital, Harouts, the Speakeasy, the Ninth Circle, the Cinderella Club, the Center, Maidman’s and, later, Ladies’ Fort.

Marion got one of his first chances to record through Archie Shepp, because Marion would see Shepp every time he came over to our house-learning from all of us and being drawn to Shepp’s then-brand-new outrageous funk. Marion was “raised” in this warhead of the avant-garde, and it seemed everything was possible!

Marion played on Shepp’s Fire Music (’65), steadily making his way up among the young names in the ’60s, and by that association was one of the privileged sidemen on Trane’s explosive Ascension (’65), which was the ultimate recognition that the new learning was here. It was also at a session, The New Wave in Jazz, which featured Trane, Shepp, Ra, Tolliver, Hutcherson and many of the other new musicians, that I last saw Marion.

That was the year of Malcolm X’s murder; a month later I was in Harlem. The next I heard of Marion he was in Europe. Later I heard he was back in the U.S., and every once in a while I’d hear about some of the things he was doing; still later I heard he’d gotten ill. But I never saw him again.

http://variety.com/2010/music/news/alto-saxophonist-marion-brown-dies-1118026100/

Alto saxophonist Marion Brown dies

Jazz avant gardist was also an educator

by Chris Morris

October 21, 2010

Music Reporter @CeeMo100

Brown had been in ill health for many years after multiple surgeries and the partial amputation of a leg, and was in an assisted living facility at his death, according to the website of instrument maker Gibson.

Brown had considered a law career before he moved to New York in 1962 and began playing professionally. He was befriended by playwright and jazz observer LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), who wrote about him favorably, and became a key player of the new jazz. In 1965, he made key appearances as a sideman on John Coltrane’s “Ascension” and Archie Shepp’s “Fire Music,” both acknowledged free jazz landmarks.

Beginning with LPs for the experimental ESP-Jazz label in the late ’60s, Brown worked as a leader through the early ’90s. His best-known albums included “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun” (ECM, 1970) and “Geechee Recollections” (Impulse, 1973).

He taught at such universities as Brandeis and Amherst during the ’70s, and earned a master’s degree in ethnomusicology from Wesleyan. In later years, he developed a parallel career as a graphic artist.

Marion Brown: Why Not?

by

Why Not?

ESP-Disk

2009 (1966)

While the term "fire music" has held sway as a descriptor of the music of post-John Coltrane/Albert Ayler saxophonists from the 1960s onward, it's long been an incomplete summation of the work of most of these musicians. Alto saxophonist Marion Brown appeared on Coltrane's Ascension and tenor man Archie Shepp's Fire Music (both Impulse, 1965) and his playing was early on championed by poet/critic LeRoi Jones. His first recording as a leader, for ESP in 1965, was a spirited post-Coleman pianoless group with trumpeter Alan Shorter, tenor man Bennie Maupin, bassists Reggie Johnson and Ronnie Boykins and drummer Rashied Ali. The recording moved effortlessly between the poles of bouncy, Latinate blues and a more urbane freedom, but Brown's tight, squirrely sound wasn't without a sense of melody and a penchant for gentle, folksy exploration.

Like Coltrane and saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, Brown's brand of "free music" often necessitated the harmonic underpinnings of a piano or a guitar. After an aborted and unreleased session for the tiny, short-lived Pixie label, Brown returned to the ESP studio with his working quartet on October 23, 1966 to wax Why Not?. Rashied Ali sat in the drum chair otherwise occupied by the excellent Bobby Kapp, while bassist Norris "Sirone" Jones and pianist Stanley Cowell rounded out the unit.

The most immediately striking thing about Why Not? is its utter and complete dedication to both wistful, romantic lyricism and the edgy, insistent "cry." There are few recordings in this music which balance hunger and fullness so well. The theme toys with an expansive, Coltrane-like keen and ebullient, skipping Latin rhythms, Brown switching between a liquid purr and clipped barks. Cowell is the first soloist on what was one of his earliest recordings, lushly orchestral arcs clambering a poised modal staircase as Sirone and Ali follow an independent yet wholly relational path. Brown's solo is playfully loquacious, tugging at notes with hiccups and flourishes until he reaches a long, palate-cleansing passage of high harmonic squeals. Like fellow altoists Ornette Coleman, Prince Lasha and Eric Dolphy, the building of a solo across bar lines is natural and approximates speech-like cadences toward poetic bubblings-over.

The stately ballad "Fortunato," reprised on Three for Shepp (Impulse, 1966) and La Placita (Timeless, 1977) is a tense caress, an aching lament hanging in midair with occasional punctuated agitation. The theme itself recalls altoist Jackie McLean's rendition of "Poor Eric" on Right Now (Blue Note, 1965) in its eulogistic cries and the skittering eddies of light dissonance underneath the altoist's statements. Following the mashed arpeggios and trills of the title piece, the quartet closes with "Homecoming," a processional that gives Cowell room to stretch his free stride (not unlike peer Dave Burrell) into nose-dives and surging architecture. Known more for his work in trumpeter Charles Tolliver's progressive post-bop group Music Inc., it's a gas to hear him in a freer context. With the support of bass and drums, Brown's phrases dig in their heels with a peppery grit, martial calls-to-arms elevating into curlicues and winking abstractions in the mode of a lighter Sonny Rollins before Ali expounds on the theme, a testament to his then-growing abilities as a highly melodic drummer.

There's another story behind Why Not?, however, and that is of its curious cover images, taken upon Brown's arrival in Europe in late 1967. Photographer Guy Kopelowicz says: "the photo on the cover was taken in September shortly after Marion arrived in Paris. On the day of the photo shoot, Daniel Berger drove Marion and I in his 2CV Citroen. We started from central Paris and headed to the Place de la Concorde at the bottom of the Champs-Elysees. Marion was delighted in having a tour of the city and managed to avoid being hit by passing cars as he walked around for vantage positions of the fountains and the Eiffel Tower. He also enjoyed the ice cream that was being sold by a vendor on the Place [as reproduced on the Base Records reissue of Brown's ESP debut].

"At the corner of the Rue Washington, near the Arc de Triomphe, there was a huge publicity poster depicting the red and blue Bonnet Phrygien, the headwear of participants in the French Revolution. The poster had a 'Revolutionnaire' sign and was a teaser for a publicity campaign for an undisclosed product. Berger thought it might be worth a try to have photos taken of Marion in front of the colorful poster with a revolutionary attitude over what looked like a mini barricade."

The back cover image of Brown and his saxophone was also taken by Kopelowicz, at a concert at the American Center in Paris, where he was playing with his cooperative group with German vibraphonist and multi-instrumentalist Gunter Hampel. By the time Marion Brown's music started to get attention—he recorded two larger groups for the Fontana and Impulse! labels before leaving New York—the intrepid saxophonist was already off to Europe to find appreciation.

Tracks: La Sorella; Fortunato; Why Not?; Homecoming.

Personnel: Marion Brown: alto saxophone;

Stanley Cowell: piano; Sirone: bass; Rashied Ali: drums.

ESP-Disk

2009 (1966)

While the term "fire music" has held sway as a descriptor of the music of post-John Coltrane/Albert Ayler saxophonists from the 1960s onward, it's long been an incomplete summation of the work of most of these musicians. Alto saxophonist Marion Brown appeared on Coltrane's Ascension and tenor man Archie Shepp's Fire Music (both Impulse, 1965) and his playing was early on championed by poet/critic LeRoi Jones. His first recording as a leader, for ESP in 1965, was a spirited post-Coleman pianoless group with trumpeter Alan Shorter, tenor man Bennie Maupin, bassists Reggie Johnson and Ronnie Boykins and drummer Rashied Ali. The recording moved effortlessly between the poles of bouncy, Latinate blues and a more urbane freedom, but Brown's tight, squirrely sound wasn't without a sense of melody and a penchant for gentle, folksy exploration.

Like Coltrane and saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, Brown's brand of "free music" often necessitated the harmonic underpinnings of a piano or a guitar. After an aborted and unreleased session for the tiny, short-lived Pixie label, Brown returned to the ESP studio with his working quartet on October 23, 1966 to wax Why Not?. Rashied Ali sat in the drum chair otherwise occupied by the excellent Bobby Kapp, while bassist Norris "Sirone" Jones and pianist Stanley Cowell rounded out the unit.

The most immediately striking thing about Why Not? is its utter and complete dedication to both wistful, romantic lyricism and the edgy, insistent "cry." There are few recordings in this music which balance hunger and fullness so well. The theme toys with an expansive, Coltrane-like keen and ebullient, skipping Latin rhythms, Brown switching between a liquid purr and clipped barks. Cowell is the first soloist on what was one of his earliest recordings, lushly orchestral arcs clambering a poised modal staircase as Sirone and Ali follow an independent yet wholly relational path. Brown's solo is playfully loquacious, tugging at notes with hiccups and flourishes until he reaches a long, palate-cleansing passage of high harmonic squeals. Like fellow altoists Ornette Coleman, Prince Lasha and Eric Dolphy, the building of a solo across bar lines is natural and approximates speech-like cadences toward poetic bubblings-over.

The stately ballad "Fortunato," reprised on Three for Shepp (Impulse, 1966) and La Placita (Timeless, 1977) is a tense caress, an aching lament hanging in midair with occasional punctuated agitation. The theme itself recalls altoist Jackie McLean's rendition of "Poor Eric" on Right Now (Blue Note, 1965) in its eulogistic cries and the skittering eddies of light dissonance underneath the altoist's statements. Following the mashed arpeggios and trills of the title piece, the quartet closes with "Homecoming," a processional that gives Cowell room to stretch his free stride (not unlike peer Dave Burrell) into nose-dives and surging architecture. Known more for his work in trumpeter Charles Tolliver's progressive post-bop group Music Inc., it's a gas to hear him in a freer context. With the support of bass and drums, Brown's phrases dig in their heels with a peppery grit, martial calls-to-arms elevating into curlicues and winking abstractions in the mode of a lighter Sonny Rollins before Ali expounds on the theme, a testament to his then-growing abilities as a highly melodic drummer.

There's another story behind Why Not?, however, and that is of its curious cover images, taken upon Brown's arrival in Europe in late 1967. Photographer Guy Kopelowicz says: "the photo on the cover was taken in September shortly after Marion arrived in Paris. On the day of the photo shoot, Daniel Berger drove Marion and I in his 2CV Citroen. We started from central Paris and headed to the Place de la Concorde at the bottom of the Champs-Elysees. Marion was delighted in having a tour of the city and managed to avoid being hit by passing cars as he walked around for vantage positions of the fountains and the Eiffel Tower. He also enjoyed the ice cream that was being sold by a vendor on the Place [as reproduced on the Base Records reissue of Brown's ESP debut].

"At the corner of the Rue Washington, near the Arc de Triomphe, there was a huge publicity poster depicting the red and blue Bonnet Phrygien, the headwear of participants in the French Revolution. The poster had a 'Revolutionnaire' sign and was a teaser for a publicity campaign for an undisclosed product. Berger thought it might be worth a try to have photos taken of Marion in front of the colorful poster with a revolutionary attitude over what looked like a mini barricade."

The back cover image of Brown and his saxophone was also taken by Kopelowicz, at a concert at the American Center in Paris, where he was playing with his cooperative group with German vibraphonist and multi-instrumentalist Gunter Hampel. By the time Marion Brown's music started to get attention—he recorded two larger groups for the Fontana and Impulse! labels before leaving New York—the intrepid saxophonist was already off to Europe to find appreciation.

Tracks: La Sorella; Fortunato; Why Not?; Homecoming.

Personnel: Marion Brown: alto saxophone;

Stanley Cowell: piano; Sirone: bass; Rashied Ali: drums.

Title: Marion Brown: Why Not?

| Year Released: 2010

Georgia Recollections: Goodbye, Marion Brown

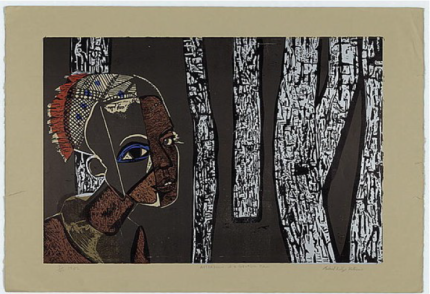

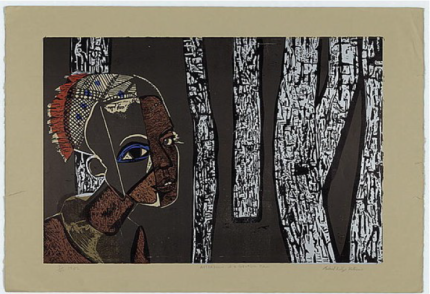

Marion Brown on the cover of Geechee Recollections, part of his trilogy about Georgia. Courtesy of the artist

As I see it, Georgia didn't open up to me until I left home. Don't be fooled: Atlanta suburbs are not the Old South. Neighborhoods are named for the farmers who once plowed the soil, and sweet-tea-sipped accents are at least five counties away. Not until I moved to Athens, Ga., and eventually to Washington, D.C., did I see Georgia for the weird and surreal place it was and is.

Marion Brown was born Sept. 8, 1935 in Atlanta (or 1931, depending on who you ask). He stayed in Georgia long enough to see the Confederate stars and bars added to the state flag at the height of desegregation. His travels took him to New York, where Archie Shepp and Ornette Coleman encouraged Brown to develop his talents. The alto saxophonist appeared on John Coltrane's Ascension and Shepp's Fire Music, his reflective and sometimes playful tone an ear-bending foil to the fire-breathing of his peers.

After time in Paris and touring Europe, Brown returned to Atlanta, where a surge of creativity flowered like dogwood: Beautiful and bright, but burnt at the tips. Inspired by the stark Southern reflections in Jean Toomer's epic work Cane, and his own birthplace enlightenment, Marion Brown released a trilogy of records dedicated to Georgia: Afternoon of a Georgia Faun (1970), Geechee Recollections (1973) and Sweet Earth Flying (1974). (The latter two remain out of print.) Adorned with pastoral poetry and folksong, these albums evoke a Southern experience.

YouTube

"Once Upon a Time (A Children's Tale)," from Marion Brown, Geechee Recollections [Impulse]. Marion Brown, alto and soprano sax; Wadada Leo Smith, trumpet; James Jefferson, bass, cello; Steve McCall, drums; William Malone, autoharp, thumb piano; A. Kobena Adzenyah, African drums. Released 1973.

At a certain point of reflection and education, I became a conflicted Southerner. I sought the harmony of my past, the understanding of a history I adopted as my own. (My family moved to Georgia at age seven, but "American by birth, Southern by the grace of God," we say). Like its soul food, Georgia's history is lush and cooked down, yet brutal in its lumbering wake. It's near impossible to reconcile what came and what is to come with a state that only in the last decade removed the Dixie from its flag. It is our heritage, yes. And in an odd way, those of us who've struggled with those issues are proud still.

There is hurt in Marion Brown's trilogy. How could there not be? Jean Toomer wrote of "Thunder blossoms gorgeously above our heads [...] Bleeding rain / Dripping rain like golden honey." Beautiful and terrifying: In its unique and abstract way, this is how I eventually came to see my home. The quiet, percussive "Afternoon of a Georgia Faun" as a haunting spirit of the swampy urban jungle; the rhythmic dance of "Once Upon a Time (A Children's Tale)" as the celebration of summer; the solo bookends of the Sweet Earth Flying suite, played by Paul Bley (Fender Rhodes) and Muhal Richard Abrams (piano), two soulful and somber blues rendering Georgia dawn and Georgia dusk.

While this Southern trilogy certainly doesn't capture the breadth of Brown's work, it's a personal statement that speaks beyond music. It should be part of the Southern canon along with The Color Purple, Coca-Cola, Rev. Howard Finster, James Brown, the Stone Mountain laser show and Sid Bream's slide into home plate.

Multiple sources are reporting that Brown died in his assisted living community in Hollywood, Fl. this past weekend. Out of sight for the past three decades due to illness, Marion Brown was a musical spirit guide to those lucky to find him. Cradled between Anthony Braxton sides at WUOG was Afternoon of a Georgia Faun for me to discover in 2004. Listening then as now, I'm taken off I-85 and down the winding, unlit roads of 441, hearing the South in moving fabric. I'm home.

A Fireside Chat with Marion Brown

by

In recent years, I had heard that Marion Brown was ill. Such vague

details were of grave concern since I had first experienced his virtuoso

playing on John Coltrane's wicked Ascension opus. It was only a matter

of time before Three for Shepp was in my collection and then came Porto

Nova, Reed 'n Vibes, and Live in Japan. Through Roadshow friend, Gunter

Hampel, I learned of Brown's trials and they are many in number. Brown

has undergone brain surgery, eye surgery, has had all of his teeth

extracted, and a portion of his leg has been amputated and he has had to

learn to walk with a prosthetic. For such a gentle soul, it is too much

for me to bear. From an undisclosed nursing home in New York, we spoke

of his life, his love, his music, as always, unedited and in his own

words.

All About Jazz: Let's start from the beginning.

Marion Brown: It was because of my mother. My mother liked music and I loved her a lot and she brought me to the attention of music and it stuck, so I started taking lessons. The saxophone was my first instrument because of Charlie Parker. When I heard him, it was the greatest saxophonist I had ever heard before. He decimated me. I liked his technique and his ideas. He had stupendous technique and brilliant ideas. That showed me that he's a very intelligent man.

AAJ: You attended both Clark College and Howard University, an impressive amount of education, which at the time was unheard of for a black man.

MB: Yeah, right, Fred. And then I played in the army band for three years. It was very good experience. That's how I got my chops and learned to be able to rely on myself. I played the alto, the clarinet and the baritone saxophone.

AAJ: What prompted the move to New York?

MB: My mother wanted a better life for herself and a better life for me, so she came to New York to find it.

AAJ: Sounds like she was a single mother.

MB: Yes, she was. My mother was my total inspiration. Everything I did, I did it for her.

AAJ: How did you get involved with the Sixties free jazz whirlwind?

MB: After I left Howard University and came to New York City and met Archie Shepp and Ornette Coleman. I met Archie Shepp in 1962. He lived in a building where I had a friend live, Leroy Jones. And one time I was visiting Leroy Jones and on the way downstairs, I heard Archie Shepp in his studio practicing, so I went in. I had a soprano recorder in my pocket and I played some soprano sonatas for Archie and he liked my playing so well, he offered me the opportunity to play with him. But I didn't have a saxophone, so Ornette Coleman let me use his white plastic saxophone to get started.

AAJ: Nice of Ornette to come through and the infamous white plastic saxophone no less.

MB: Well, I met Ornette through WBAI FM. I did some jazz programs on there substituting for A.B. Spellman and Ornette heard me and he liked what I did and he wanted to meet me.

AAJ: At the time, Ornette was creating quite a firestorm in New York. What was your impression of Ornette?

MB: Ornette Coleman is the same as Charlie Parker, but he did it a different, the opposite way. Charlie Parker did everything that he did based on knowing harmony and chords. Ornette Coleman did everything he did based on knowing how to reach inside of himself and create music intuitively.

AAJ: Whose approach did you find more appealing?

MB: I found Ornette more appealing. I thought it was better to play what you felt naturally than to have a lot of systems based on chords and things.

AAJ: Being without a saxophone initially, when were you able to purchase your own horn?

MB: As soon as I started working with Archie, I earned enough money to buy my own, so I gave Ornette his horn back.

AAJ: You performed on John Coltrane's Ascension. How did you find yourself on the session?

MB: Well, I met Coltrane through Archie Shepp. Archie told him about my music and he started to listen to it and he liked it. And then, several times, he would come to hear me play and he liked that. So when he decided to do "Ascension," I fit the picture of somebody that he wanted in it. Coltrane was a very brilliant man and a beautiful person. He was one of a kind. His sound and technique, those things he used to play called "sheets of sound," that and his feeling of a love for God. His spirituality became the most important part of his music because he was thankful to God for all the things that God had given him to make him who he was.

AAJ: During much of the Sixties, American musicians were seeking sanctuary and employment in Europe. You were one of them.

MB: The climate was good as far as people liking the music, but it was impossible to make enough money to meet the cost of living. The climate was the same in Europe. People liked music and it was possible to get enough gigs to survive.

AAJ: You recorded two sessions for the ESP label, Marion Brown Quartet and Why Not?, how did you end up recording for the now defunct label?

MB: I found out where their office was and I started going by there and talking to them. So they basically became interested in seeing what I had and when he heard me, he liked me and so he gave me an opportunity to record. As a matter of fact, Fred, that very first album that I made for ESP is being reissued next month.

AAJ: Compared to the ESP dates, Three for Shepp, and Porto Nova, Afternoon of a Georgia Faun set in motion the inclusion of African rhythms and motifs in your music.

MB: It is the performance of it because African music has as performers, not only the performers, but the audience and listeners as well.

AAJ: An example of that would be the Art Ensemble.

MB: Yes. I did that with Leo Smith. He stayed in Connecticut when I was up there teaching. He needed a place to stay and I had a house, so I let him stay with me. We became friends and musical partners back then. I was teaching in elementary schools. I was teaching children how to make instruments and create their own music.

AAJ: What were some instruments you developed?

MB: I made mostly percussion instruments and I made some flutes from bamboo. I played them with Leo Smith and for ECM on Afternoon of a Georgia Faun.

AAJ: Let's touch on your collaboration with Gunter Hampel, whom you worked with for almost twenty-five years.

MB: I met him the first time in Belgium, Liege. We became friends and worked together and as a matter of fact, him and I played here at this place last month.

AAJ: As educated as you are, music is one of many options you could have taken, any regrets?

MB: No regrets and I still don't because I'm a very well known musician and I met a lot of people. As a matter of fact, Fred, last year, I met Sonny Rollins, who is one of the most beautiful people that I've met in my whole life. Not only is he a musical genius, but he's a human genius. I would love to record with him.

AAJ: Your health has been a concern, how are you holding up?

MB: I'm fine now, but for the last six years, I've been through some serious health problems. I had brain surgery. I had laser eye surgery, all of my teeth removed, and the last thing was that my left foot was amputated, so I have to walk now with a prosthetics. It has been a challenge. That is what they taught me to do at this place.

AAJ: How long of a period passed before you were able to comfortably walk?

MB: Twelve weeks. It puts life in a perspective, but the perspective is more beautiful before these things happened because I've learned to appreciate God more.

AAJ: Any memories stand out?

MB: Philly Joe Jones. He was an incredible drummer and a very incredible person. It was the night that I recorded with him first. I went into the studio and he was setting up his drums. So I walked over to him and said, "Hey, Joe, how you doing?" And he said, "Fine, Marion." I said, "What are you going to do for me tonight?" And then he smiled and said, "I'm going to fry your little ass." (Laughing) And he did. Yes, he did because the man could play four, five rhythms all at the same time, different ones and have them all clicking on the one. I played better than I had ever played before because he spun a carpet under me. All I had to do was ride it.

AAJ: And the future?

MB: I recorded last year with a singer and that's about it. There is a new record out in Germany that I'm on.

https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Marion%20Brown

Marion Brown (September 8, 1931 – October 18, 2010)[1] was an American jazz alto saxophonist and ethnomusicologist. He is most well known as a member of the 1960s avant-garde jazz scene in New York City, playing alongside musicians such as John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, and John Tchicai. He performed on Coltrane's landmark 1965 album Ascension.[2]

Biography

As sideman

“A man walking into the future backwards”:

“It’s high time for a re-assessment of the work of Artist X.” ‘Re-assessment’; ‘re-appraisal’ – these words imply that something has been (unjustly) forgotten, and hence that it must be discovered anew. What, then, is the catalyst for such a process? What makes us (critics, listeners, musicians) suddenly pay attention, having ignored the forgotten object for so long? Sadly, it seems that sometimes it takes the death of a great artist for us to really pay proper attention to what they created during life. And it’s noticeable that the alto saxophonist, ethnomusicologist, composer and writer Marion Brown, who passed away on October 18th 2010, is still most frequently mentioned as ‘one of the saxophonists who played on John Coltrane’s Ascension’ – this despite the fact that he subsequently produced an impressive body of work arguably equal to that of any of the major artists who came to prominence during the flourishing ‘New Thing’ movement of the ’60s and ’70s. True, he had barely played in the last couple of decades, due to ill-health and some disastrous medical procedures, and his straightahead jazz work from the late 70s and through the eighties, while pleasant and melodic, lacked the structural and emotional range of his more experimental period. True also that almost all of his recordings were out of print, though most had become available, in recent years, on music-sharing blogs, and had perhaps even extended their influence to the world of left-field rock music: a few years ago, the band His Name is Alive released a surprisingly effective (and affecting) album consisting solely of Brown’s compositions, combining African percussion withswampy, droning electric guitars and pianos and free jazz horn parts in a way that was both faithful to the spirit of the original music and willing to take it in different directions. In any case, I know that, over the past few years, before and after the release of that tribute album, I have returned again and again to Brown’s recordings, which so generously, so easily give up their riches – accessible on first listen, but with a depth that rewards deeper and further digging, re-listening, re-appraisal, re-assessment.

Despite his neglect, Brown was certainly as good an improviser as the better-known ‘New Thing’ musicians Archie Shepp (an early friend and mentor) and Pharoah Sanders. All along though, and despite overtly free jazz work with Burton Greene and in his own group with Alan Shorter[1], he wasn’t so much ‘New Thing’ as into his own thing – a good dose of classical influence, an interest in ethnic musics (which, admittedly, Sanders and Shepp shared), and, above all, a sparer approach than the other two musicians. Whereas Shepp and Sanders were well capable of emoting to great effect (the prelude section to ‘Creator has a Master Plan’, or Shepp’s gorgeous, impressionistic reading of ‘In a Sentimental Mood’ (from ‘On this Night’, 1965)), Brown was more understated, relying on the carefully chosen phrase, on clear motivic development rather than the pure sound/smear/scream tactic. This approach can be heard at its purest on his two solo saxophone recordings from the late 70s and early 80s, ‘Solo Saxophone’ and ‘Recollections – Ballads and Blues for Alto Saxophone’. The solo concert was a context in which he played often, at small local engagements with perhaps twenty or thirty people in the crowd, and this perhaps accounts for the relaxed feel to the music. Here, Brown is not so much concerned with ‘playing free’ or ‘being innovative’ as with simply playing, standards mostly. It’s almost as if he were practicing in a back room, woodshedding, revisiting the familiar melody, thinking about it as he plays – picking up, for example, on connections between Ellington’s ‘Black and Tan Fantasy’ and ‘Ask Me Now’, the latter appended as a little coda to the end of the former in a way that sound spontaneous rather than pre-planned. (I’m reminded here of Anthony Braxton’s approach to standards on his Piano Quartet recordings of the mid-90s, where the tunes flow into one another, medley-style: improvisation as a method of melodic thinking that harks back to the earliest developmental stages of jazz, where the solo was an extension of the original tune – a counter-melody, or succession of counter-melodies, fitted well within the original contours of the piece.)

In some ways, though, that solo recording is something of something of an anomaly in Brown’s recorded work, for his finest music invariably focuses very much on a group ethic – it’s the sound of the whole band that one remembers after the music stops, as much as it is the playing of the leader. This is not achieved through free, collective blowing, but through compositional and organizational strategies similar to those adopted by the AACM (with whose members Brown often played, though he was never a fully-fledged member), or through a loose, groove-based approach that seems to derive at least in part from jazz fusion. The result is a special kind of atmosphere – that intangible quality which critics love to harp on about, perhaps as an excuse not to have to delve into the technical details of how said ‘atmosphere’ is actually accomplished – that ‘grain’ which gives Brown’s music its special ‘voice’. Listen: it’s there when he takes elements of the keyboard-rich sound found on early Miles Davis fusion – all those twinkling electric piano melodies and chordal textures – to build something that’s soothingly lovely, static and hovering (‘Sweet Earth Flying’); it’s there when, with different instrumentation, he conjures up the wonderful, hazy, late-summer, small-town feel of a piece like ‘Karintha’ from ‘Geechee Reccollections’; and it’s there when he presents a challengingly indeterminate (though in fact, carefully organized) avant-garde soundscape on ‘Afternoon of a Georgia Faun’ – music which seems to be half-asleep, yet is crafted with subtly shifting, delicate improvisational care.

Perhaps it has something to do with Brown’s Southern background. Born in Georgia, he moved to New York City where the ‘jazz revolution’ was in progress, but never forgot his regional roots. Archie Shepp, who also moved from the South up to New York, where he met Brown, commented: “We bonded, in a way. We were both from small towns in the South. Most of my close friends, in general, were African Americans born in the North. It was quite fortuitous meeting Marion. He reminded me of people I grew up with. He always held onto his southern drawl, but had an enormous intellect and spirit.”[2]

This is not simply a romanticised American primitivism, contrasting with the city sophistication of, say, Cecil Taylor – indeed, the title of Brown’s record ‘Afternoon of a Georgia Faun’ specifically invokes the urbane Claude Debussy, in whose music ‘nature’ is the ‘nature’ of the Parisian city-dweller’s boat trips and river-side picnics, or of an idealised classical arcadia, rather than the ‘nature’ of genuine rural experience. What Brown is doing is to apply the dreamy, symbolist languor of turn-of-the-century French impressionist classical music to his own Southern childhood – a life, let us speculate, that was governed by changes in the weather and the seasons, by an engagement with light and shade, with touch and taste and sight and smell rather than the adrenaline and stimulant buzz of the city – a life with something ‘unreal’ about it, something undefined, hazy, dreamy, even surreal; alright, a life that was never quite like this, with hardships and injustices that are present within the dream, but downplayed, receding into the background of an imaginative and partly imaginary dreamscape. Importantly, this is the South as recalled from the North, from the big city, the ‘Big Apple’ (and even from abroad – Brown lived in Paris from 1967-1970[3]), drawing on the resources of memory to create a quasi-mythology with which to contrast life as it is lived in the metropolis, a means of coping with that pain, that sense of awkwardness and uncertainty to which early blues lyrics so often attest: “I’d rather drink muddy water and sleep in a hollow log/ Than go up to New York City and be treated like a dirty dog.” [4] The blues, in all its different forms – the country blues, the town blues, the town-and-country blues;[5] not so much the blues as form (Shepp and even Ayler were far more obviously blues and R-&-B based players than Brown (check out Ayler’s ‘Drudgery’)), but the blues as feeling – the blues as a reflection of life. Brown was quoted thus in the liner notes to Porto Novo: “My reference is the blues, and that’s where my music comes from. I do listen to music of other cultures, but I just find them interesting. I don’t have to borrow from them. My music and my past are rich enough. B.B. King is my Ravi Shankar”. [6]

One might argue that this thesis is somewhat tenuous – I may be applying an inaccurate process of imaginative transformation to Brown’s childhood – and one might not immediately conceive the mid-60s free jazz dates for ESP as specifically ‘Southern’ or musics in this way. And yet, listen to the last track, ‘Homecoming’, on ‘Why Not’, with its almost Charles Ivesian melody. African-American music was always a melting pot – Afro-Cuban percussion melded to marching-band instruments, ‘streetwise’ sensibilities that would later manifest themselves into hip-hop culture melded to music derived from rural worksongs – and Brown’s music makes full use of this diversity in order to reflect on where he has come from and where he is now at.[7] After all, it’s not as if the memory of the South just disappeared, was simply swallowed up into new Northern, urban forms of African-American popular music – think of the popularity of Ray Charles singing ‘Georgia on My Mind’ in 1960. And it’s not simply a case of nostalgia, either: as fellow Georgian Lars Gotrich notes in his online appreciation of Brown,

Brown was heavily influenced by the writer Jean Toomer, and the word ‘bittersweet’ barely suffices as a description of Toomer’s exquisite evocation of a storm, from the poem that gave its name to Brown’s album ‘Sweet Earth Flying’: “Thunder blossoms gorgeously above our heads […] Bleeding rain / Dripping rain like golden honey.”[9] The storm is figured as a flower, as a bleeding human, or animal, and as a supernatural provider of food (like manna from heaven); an overabundance of metaphor and simile, like the abundance of water with which the clouds refresh the earth, like the simultaneous upsurge of feelings at the sight of its approach; an almost sexual sense of sky and ripeness – “Full-lipped flowers/ Bitten by the sun” – that reaches towards the kind of understanding found in mythologies, creation myths, old wives’ tales, magic, folklore, rather than towards that found in western, rationalist scientism. Music is the perfect vehicle for this evocative illogic, with its resource to the suggestiveness of sound, sound that does not need to be encumbered by direct explanation (though often Brown uses words – poetic recitation – and human voices – whispers, sighs – as an essential and sensual part of his music). Here we return once more to Debussy – his languorous ‘L’Après-Midi d’un Faune’, his portraits of the sea, of sunken cathedrals, joyous islands – or the dreamscape of ‘Péleas et Mélisande’ – not so much fulfilling the Romantic fad for ‘programme music’ (which would subsequently translate itself into the mimetic world of the Hollywood soundtracks), as evoking a general sense of place (hence the fact that he could title pieces of music, a non-visual art form, ‘Images’). One might argue that Brown has a comparatively direct approach that Debussy lacks, but then again, it’s probably not all that helpful to draw too direct a correlation between the two. As Cecil Taylor remarked when a fan compared his playing to Ravel’s Sonatine: “Why don’t you talk about Duke Ellington and Bud Powell?”[10]

Instead, let’s talk about Jean Toomer, whose words we have already quoted and briefly discussed. Brown’s ‘Georgia Trilogy’ (Afternoon of a Georgia Faun (1970), Geechee Recollections (1973), and Sweet Earth Flying (1974) – I’d also include Poems for Piano (1979), in which Amina Claudine Myers plays Brown’s Toomer-inspired compositions, and November Cotton Flower, from the same year) derives much of its inspiration from the seminal modernist ‘novel’ Cane, a work where prose and poetry are not so much juxtaposed as melted into each other in a languid evocation of the South that seems to have struck a chord with Brown’s own up-bringing; where images cluster like grapes, building up in liquid globs, at once sharply distinct and hazy, subject to change at any moment, like (again the simile) the passing storm looming, opening overhead, then passing once more.

Brown’s use of Cane is several-fold: on the one hand, its atmosphere is apt, apposite, similar to that of his own music; furthermore, this atmosphere has very personal, autobiographical resonances with Brown’s own Georgia childhood; in addition, drawing from a literary text (Bill Hasson recites a section from the book on ‘Geechee Recollections’) reflects Brown’s intellectual bent (he was a “running buddy” of the poet LeRoi Jones, appearing in a minor role in the first production of Jones’ play ‘Dutchman’, and contributing essays and record reviews to several publications[11]). White critics often argued (particular in relation to the music of Ornette Coleman), that free jazz was in some way a ‘primitive’ form of expression, bypassing thought in order to directly access feeling;[12] here we see the legacy of the Beats, the notion that African-Americans and their music somehow represented a ‘primitive’ state, preferable to the cynicism and ‘sophistication’ of nuclear white America. While such arguments may have been well-intentioned in the latter case, later critics often put a negative spin on them, and the racial connotations were patronising and potentially harmful. Thus, Brown’s employment of Toomer, as well as his articulate commentary on his own and other’s music, helped to mitigate against the erroneous notion of the untutored ‘Negro’, playing purely from feeling, with little or no training or compositional awareness. According to Nathaniel Mackey,

Michael Kelly Williams, ‘Afternoon of a Georgia Faun’ (1985)

It’s worth examining ‘Faun’ in depth: the most experimental of Brown’s works, it is also one of the richest in terms of its conceptual underpinnings. Indeed, an entire book, entitled ‘Afternoon of a Georgia Faun – Views and Reviews’, was dedicated to the album and published in 1973 (like ‘Recollections’, a collection of Brown’s writings which came out in 1984, this is out-of-print and extremely rare). Brown was not simply ‘making a record’, ‘laying down a few tunes’ for jukebox airplay: these were lengthy soundscapes for which the term ‘jazz’ seemed out-dated. They might not have existed without jazz, but they could not be constrained by the word, by the label ‘jazz’, or, at least, by the way in which critics and listeners sought to use that label in order to enforce and constraint a certain fixed idea of the music. Instead, things mix and merge, like the ‘eight-hour dialogues’ Brown remembers having with his fellow musicians, in which “stories go in and out of each other like Bach’s counterpoint.”[14] Dialogue and the sounded voice turn out to be particularly apposite on ‘Faun’ – while the spoken word itself would not appear until Bill Hasson’s recitations on the following two albums in the ‘Georgia Trilogy’, the vocalizations of Jeanne Lee and Gayle Palmoré do function as a kind of wordless prelude to those recitations (‘Prélude a l’après-midi…’); once more that merging, that suggestive blurring of boundaries, between voice and instrument, between speech and music. Between ‘professional’ and ‘amateur’ musicians too: the second piece, ‘Djinji’s Corner,’ adapts a practice from Ghanaian music, in which a core of skilled musicians is supplemented by community members with lesser ability. Thus, the main band of six instrumentalists is supplemented by a team of three ‘assistants’ who use various percussive devices and implements, some of them invented by Brown. While Andrew Cyrille, Anthony Braxton, Bennie Maupin, Chick Corea, Jeanne Lee and Jack Gregg and can be considered virtuoso practitioners of their respective instruments, here their sonic status is often the same as that of performers who might not even be considered ‘musicians’ in the normal sense: a democratic, if not communistic, openness that anticipates experimental projects such as the Portsmouth Sinfonia and the Scratch Orchestra, initiated by British free improvisers during the 60s and 70s. For Brown, this is an affirmation of the value of improvisation as the equal of composition: unlike composition, it allows anyone to communicate and jointly participate in a musical experience. Furthermore, as Brown hints when he talks about “mutual cooperation at a folk level,” the ‘open’ approach finds ‘avant-garde’ music coming to resemble a kind of imagined folk-music, very different in sound to the traditional folk melodies heard in West Africa, or Georgia, or New York City, where the album was recorded, but possessing a similarly radical means of making. From the liner notes: “Although I am responsible for initiating the music, I take no credit for the results. Whatever they may be, it goes to the musicians collectively.”[15]

Nonetheless, the music is not improvised in a completely free manner; Brown set out an initial structure for the titular first piece, which he described as “a tone poem. It depicts nature and the environment in Atlanta. The vocalists sing wordless syllables. The composition begins with a percussion sections that suggests raindrops – wooden rain drops. The second section is after the rain. Metallic sounds that suggest light.”[16] The poetic descriptions of wooden rain drops and metallic light could have come from Toomer (or perhaps from Surrealism), but they are not there simply as pretty or striking phrases. Rather, Brown shows through them his awareness of the unstable notions here at play, highlighting the uneasy correlation between music and the visual or programmatic (light is not really metallic (unless it reflects off a metal surface), and rain drops cannot be wooden), even as he describes sound in visual terms. (One might also detect in the phrase ‘after the rain’ a reference to the composition by John Coltrane.) Furthermore, this is not simply a case of simple mimesis, of creating ‘nature music’ and ‘scene-painting’ for decorative effect; Brown further comments that the opening ‘raindrops’ section suggests “feelings of loneliness in an imaginary forest of the mind”; a “first person experience” of the world of ghosts and spirits like Amos Tutuola’s Yoruba-inspired ‘My Life in the Bush of Ghosts’, here “told collectively in the musical first person.”[17] These ‘ghosts’ are at once connected to the religion, traditions and ways of seeing of Brown’s African ancestry, and to his memories of everyday childhood experiences and feelings in Georgia; the former, which one might call collective memory, passed down as it is through oral traditions, through stories and reminiscences originating in the experiences of other people, is that which can only be imagined, not directly experienced, the latter, which one might call personal memory, arises from incidents remembered from one’s own life.[18] Personal and collective memories can be drawn together through physical movement and through sound (“mind and body…unified through memory and muscle”[19]) – just as the jazz musician at once plays ‘himself’, his unique and personal style, and beyond himself, by using vocabularies established by his forbears, some of whom are long-dead.

This, then, is another meaning of ‘folk art’ – “by connecting his physical skills as an improviser (that is, his technique) to his cultural memories and identity, [the jazz improviser] asserts that improvisation, as the height of black musical expression, connects the artist to his people.”[20]

If the title track of ‘Georgia Faun’ thus places a certain emphasis on the individual skill and ‘technique’ of the solo improviser (for instance, during Chick Corea’s piano solo during the second section of the piece), the second side of the album evinces a generally more collective approach – it is “structured in such a way…as to all but prevent the dominance of any single idea or of any one player.”[21] In Brown’s words,

Georgia Faun’ marks the only use of ‘non-musicians’ in Brown’s work, and thus constitutes something of a milestone in his discography, as well as, I would argue, the history of African-American improvised music in general. The parallels and connections between such jazz-derived experiments and the European free improvisation developing at this time are not as often explored as they might be, and certainly suggest a closer and more reciprocal relation between white and black, European and American, than might have been suggested by the racial and cultural rhetoric of the time. After all, many of the most important documents of 1960s and ’70s free jazz were recorded in Europe; and Brown’s own collaborations with European musicians (Gunter Hampel in particular) provide just one instance of the many musical connections and cross-fertilizations that occurred during this period. In any case, Brown’s notion of a “sane sociology of contemporary music”[23] was enacted not only through the specific case of using non-musicians on ‘Afternoon of a Georgia Faun’, but through his attitude to music in general:

Marion Brown: a masterful musician. Born, September 8, 1931 in Atlanta, Georgia, USA; Died, October 18th, 2010, in Hollywood, Florida, USA.

Notes

[1] Currently available are ‘Marion Brown Quartet’ (download-only, from the ESP-Disk website); ‘Why Not?’, a second quartet recording for the same label, now re-issued on CD; ‘Bloom in the Commune’, a date released under Greene’s leadership and reviewed in the first issue of this magazine; and ‘Live at the Woodstock Playhouse 1965’, a recently discovered live performance, also with Greene, released on Porter Records earlier this year.

[2] Archie Shepp, quoted in Bob Flaherty, ‘Friends Mourn Jazz Great Marion Brown’, available online at http://www.gazettenet.com/2010/10/22/friends-mourn-jazz-great-marion-brown [3] See Eric C. Porter, ‘What is this thing called Jazz? African American musicians as artists, critics, and activists’ (University of California Press, 2002), p.247 [4] Quoted in LeRoi Jones, Blues People (New York City; Perennial (Harper Collins), 2002 (1963)), pp.105-6 [5] For a more detailed discussion of the interplay between ‘country’ and ‘city’, North and South, in the development of the blues, see Jones, Blues People, pp.104-110 [6] The same could be applied to the music of the black church; compared to, say, Charles Mingus, Brown is not obviously harking back to such music in his improvisations. Nonetheless, there are echoes, reminiscences, feelings that suggest this background. As Brown puts it, “I’m constantly referring to my past…When I was growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, I went to Church every Sunday. I never really play black spirituals but I translate them into my music. Little bits of melody become footnotes to my past.” (Linda Tucci, ‘The Artist in Maine: Conversation with Marion Brown’, in The Black Perspective in Music, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Spring, 1973), pp.60-63.) [7] As Brown puts it, he seeks to convey “a personal view of my past culture…I’m constantly referring to my past…I’m like a man walking into the future backwards.” (Ibid) [8] Lars Gotrich, ‘Georgia Recollections: Goodbye, Marion Brown’

(http://www.npr.org/blogs/ablogsupreme/2010/10/19/130669448/marion-brown)

[9] Jean Toomer, ‘Storm Ending’, in ‘Cane’ (1923) [10] Gary Giddins, ‘Visions of Jazz’ (Oxford University Press, 1998), p.462 [11] See Eric Porter, ‘What is this Thing Called Jazz?: ’, p.246 [12] See, for example, James Lincoln Collier, ‘The Making of Jazz: A Comprehensive History’ (1978). [13] Nathaniel Mackey, ‘Interview by Edward Foster’, in ‘Paracritical Hinge: Essays, Talks, Notes, Interviews’ (Madison; University of Wisconsin Press, 2005), p.279 [14] Greg Tate, ‘Black-Owned: Jazz Musician Marion Brown and Son Djinji’ (Vibe, November 1994), p.38. [15] Marion Brown, Liner Notes to ‘Afternoon of a Georgia Faun’ (ECM Records, 1971) [16] Ibid [17] Quoted in Eric Porter, ‘What is this Thing called Jazz?’ (op. cit.), p. 249 [18] “My music is a personal view of my past culture. I’m transcribing from one time and place to another. I’ve never been to Africa, you know. These instruments are manifestations of something I’ve never really seen. But through listening to their music and reading, I’ve become a part of their

environment.”

(Brown, quoted in Linda Tucci (op. cit.)) [19] Porter (op. cit.) [20] Ibid [21] Henry Kuntz, review of ‘Duets’ (Brown/Leo Smith/Elliot Schwartz), http://bells.free-jazz.net/bells-part-one/marion-brown-duets/ [22]

Brown, liner notes to ‘Georgia Faun’ (op. cit.) [23] Quoted in Porter (op. cit.), p.250 [24] Marion Brown, Interview with A. Courneau (Jazz Magazine, No.133, 1966)

References

All About Jazz: Let's start from the beginning.

Marion Brown: It was because of my mother. My mother liked music and I loved her a lot and she brought me to the attention of music and it stuck, so I started taking lessons. The saxophone was my first instrument because of Charlie Parker. When I heard him, it was the greatest saxophonist I had ever heard before. He decimated me. I liked his technique and his ideas. He had stupendous technique and brilliant ideas. That showed me that he's a very intelligent man.

AAJ: You attended both Clark College and Howard University, an impressive amount of education, which at the time was unheard of for a black man.

MB: Yeah, right, Fred. And then I played in the army band for three years. It was very good experience. That's how I got my chops and learned to be able to rely on myself. I played the alto, the clarinet and the baritone saxophone.

AAJ: What prompted the move to New York?

MB: My mother wanted a better life for herself and a better life for me, so she came to New York to find it.

AAJ: Sounds like she was a single mother.

MB: Yes, she was. My mother was my total inspiration. Everything I did, I did it for her.

AAJ: How did you get involved with the Sixties free jazz whirlwind?

MB: After I left Howard University and came to New York City and met Archie Shepp and Ornette Coleman. I met Archie Shepp in 1962. He lived in a building where I had a friend live, Leroy Jones. And one time I was visiting Leroy Jones and on the way downstairs, I heard Archie Shepp in his studio practicing, so I went in. I had a soprano recorder in my pocket and I played some soprano sonatas for Archie and he liked my playing so well, he offered me the opportunity to play with him. But I didn't have a saxophone, so Ornette Coleman let me use his white plastic saxophone to get started.

AAJ: Nice of Ornette to come through and the infamous white plastic saxophone no less.

MB: Well, I met Ornette through WBAI FM. I did some jazz programs on there substituting for A.B. Spellman and Ornette heard me and he liked what I did and he wanted to meet me.

AAJ: At the time, Ornette was creating quite a firestorm in New York. What was your impression of Ornette?

MB: Ornette Coleman is the same as Charlie Parker, but he did it a different, the opposite way. Charlie Parker did everything that he did based on knowing harmony and chords. Ornette Coleman did everything he did based on knowing how to reach inside of himself and create music intuitively.

AAJ: Whose approach did you find more appealing?

MB: I found Ornette more appealing. I thought it was better to play what you felt naturally than to have a lot of systems based on chords and things.

AAJ: Being without a saxophone initially, when were you able to purchase your own horn?

MB: As soon as I started working with Archie, I earned enough money to buy my own, so I gave Ornette his horn back.

AAJ: You performed on John Coltrane's Ascension. How did you find yourself on the session?