SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2018

VOLUME FIVE NUMBER TWO

GERI ALLEN

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

TOMEKA REID

(January 27--February 2)

FARUQ Z. BEY

(February 3--9)

HANK JONES

(February 10--16)

STANLEY COWELL

(February 17–23)

(February 17–23)

GEORGE RUSSELL

(February 24—March 2)

ALICE COLTRANE

(March 3–9)

DON CHERRY

(March 10–16)

MAL WALDRON

(March 17–23)

JON HENDRICKS

(March 24–30)

MATTHEW SHIPP

(April 1–7)

PHAROAH SANDERS

(April 8–14)

WALT DICKERSON

(April 15–21)https://www.allmusic.com/artist/george-russell-mn0000646353/biography

George Russell

(1923-1986)

Artist Biography by Richard S. Ginell

While George Russell

was very active as a free-thinking composer, arranger, and bandleader,

his biggest effect upon jazz was in the quieter role of theorist. His

great contribution, apparently the first by a jazz musician to general

music theory, was a book with the intimidating title The Lydian

Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, where he concocted a concept of

playing jazz based on scales rather than chord changes. Published in

1953, Russell's theories directly paved the way for the modal revolutions of Miles Davis and John Coltrane -- and Russell even took credit for the theory behind Michael Jackson's huge hit "Wanna Be Startin' Somethin'," which uses the Lydian scale (no, he didn't ask for royalties). Russell's

stylistic reach in his own compositions eventually became omnivorous,

embracing bop, gospel, blues, rock, funk, contemporary classical

elements, electronic music, and African rhythms in his ambitious

extended works -- most apparent in his large-scale 1983 suite for an

enlarged big band, The African Game. Like his colleague Gil Evans, Russell never stopped growing, but his work is not nearly as well-known as that of Evans, being more difficult to grasp and, in any case, not as well documented by U.S. record labels.

Russell's

first instrument was the drums, which he played in the Boy Scout Drum

and Bugle Corps and at local clubs when he was in high school. At 19, he

was hospitalized with tuberculosis, but he used the enforced inactivity

to learn the craft of arranging from a fellow patient. Once back on his

feet, he played with Benny Carter, but after being replaced on drums by Max Roach, Russell began to zero in on composing and arranging. He moved to New York to join the crowd of young firebrands who gathered in Gil Evans' "salon," and he was actually invited to play drums in Charlie Parker's

band. But once again, he fell ill, finding himself in a Bronx hospital

for 16 months (1945-1946), where he began to formulate the ideas for the

Lydian Concept. Upon his recovery, Russell leaped into the embryonic fusion of bebop and Afro-Cuban rhythms by writing "Cubana Be" and "Cubana Bop," which the Dizzy Gillespie big band recorded in 1947. He contributed arrangements to Claude Thornhill and Artie Shaw in the late '40s and wrote the first (and not the last) speculative scenario of a meeting between Charlie Parker and Igor Stravinsky, "A Bird in Igor's Yard," recorded by Buddy De Franco.

While working on his Lydian theories, Russell

dropped out of active music-making for a while, working at a sales

counter in Macy's when his book was published. But when he resumed

composing in 1956, he had established himself as an influential force in

jazz. Russell's connection with Gunther Schuller

resulted in the commission of "All About Rosie" for the 1957 Brandeis

University jazz festival, and he also taught at the Lenox School of Jazz

that Schuller co-founded. He formed a rehearsal sextet in the mid-'50s that became known as the George Russell Smalltet, with Art Farmer, Bill Evans, Hal McKusick, Barry Galbraith, and various drummers and bassists. Their 1956 recording Jazz Workshop (RCA Victor) became a landmark of its time, and Russell

continued to record intriguing LPs for Decca in the late '50s and

Riverside in the early '60s. Another key album from this period, Ezz-Thetics, featured two important progressive players, Eric Dolphy and Don Ellis.

Finding the American jazz scene too confining for his music, Russell

left for Europe in 1963, living in Sweden for five years. From his new

base, he toured Scandinavia with a new sextet of European players and

received numerous commissions -- including a ballet based on Othello, a

mass, and the orchestral suite Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature: 1980. Upon his return to the U.S. in 1969, he joined the faculty of the New England Conservatory of Music, where Schuller had started a jazz department, and this gave him a secure base from which to tour occasionally with his own groups. Russell

stopped composing from 1972 to 1978 in order to finish a second volume

on the Lydian Chromatic Concept. He led a 19-piece big band at the

Village Vanguard for six weeks in 1978, played the Newport Jazz Festival

when it was based in New York City, and made tours of Italy, the U.S.

West Coast, and England in the '80s.

Russell's

most imposing latter-day commissions included "An American Trilogy" and

the monumental three-hour work "Time Line" for symphony orchestra, jazz

ensembles, rock groups, choir, and dancers. In addition to The African Game and So What on Blue Note, Russell

made recordings for Soul Note in the '70s and '80s and Label Bleu in

the '90s, while continuing to teach at the New England Conservatory and

leading his Living Time Orchestra big band into the 21st century. In 2005 George Russell & the Living Time Orchestra's The 80th Birthday Concert,

released on the Concept label, celebrated the legendary octogenarian's

contributions to the art of jazz with performances of some of his most

groundbreaking extended compositions and arrangements. George Russell died in Boston on July 27, 2009 of complications from Alzheimer's disease; he was 86 years old.

George Russell

George Russell

George Russell is a hugely influential, innovative figure in the

evolution of modern jazz, the music's only major theorist, one of its

most profound composers, and a trail blazer whose ideas have transformed

and inspired some of the greatest musicians of our time.

Russell

was born in Cincinnati in 1923, the adopted son of a registered nurse

and a chef on the B&O Railroad. He began playing drums with the Boy

Scout Drum and Bugle Corps and eventually received a scholarship to

Wilberforce University where he joined the Collegians, whose list of

alumni include Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Fletcher Henderson, Ben

Webster, Cootie Williams, Ernie Wilkins and Frank Foster. But his most

valuable musical education came in 1941, when, in attempting to enlist

in the Marines, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, spending 6 months in

the hospital where he was taught the fundamentals of harmony from a

fellow patient. From the hospital he sold his first work, “New World,”

to Benny Carter. He joined Benny Carter's

Band, but was replaced by Max Roach; after Russell heard Roach, he

decided to give up drumming. He moved to New York where he was part of a

group of musicians who gathered in the basement apartment of Gil Evans.

The circle included Miles Davis, Gerry Mulligan, Max Roach, Johnny

Carisi and on occasion, Charlie Parker. He was commissioned to write a

piece for Dizzy Gillespie's orchestra; the result was the seminal

“Cubano Be/Cubano Bop” the first fusion of Afro-Cuban rhythms with jazz,

premiered at Carnegie Hall in 1947 and featuring Chano Pozo. Two years

later his “Bird in Igor's Yard” was recorded by Buddy DeFranco, a piece

notable for its fusion of elements from Charlie Parker and Stravinsky.

It

was a remark made by Miles Davis when George asked him his musical aim

which set Russell on the course which has been his life. Miles said he

“wanted to learn all the changes.” Since Miles obviously knew all the

changes, Russell surmised that what he meant was he wanted to learn a

new way to relate to chords. This began a quest for Russell, and again

hospitalized for 16 months, he began to develop his “Lydian Chromatic

Concept of Tonal Organization.” First published in 1953, the Lydian

Concept is credited with opening the way into modal music, as

demonstrated by Miles in his seminal “Kind of Blue” recording. Using the

Lydian Scale as the PRIMARY SCALE of Western music, the Lydian

Chromatic Concept introduced the idea of chord/scale unity. It was the

first theory to explore the vertical relationship between chords and

scales, and was the only original theory to come from jazz. Throughout

the 1950's and 60's, Russell continued to work on developing the Concept

and leading bands under his direction. In the mid-fifties, a superb

sextet, including Bill Evans and Art Farmer recorded under his

direction, producing “The Jazz Workshop,” an album of astonishing

originality; the often dense textures and rhythms anticipated the

jazz-rock movement of the 1970's. Click for larger imageDuring this

time, he was also working odd jobs as a counterman in a lunch spot and

selling toys at Macy's at Christmas; the release of “The Jazz Workshop”

put an end to Russell's jobs outside of music. He was one of a group to

be commissioned to write for the first annual Brandeis Jazz Festival in

1957--”All About Rosie” was based on an Alabama children's song. “New

York, New York,” with poetry by Jon Hendricks and featuring Bill Evans,

Max Roach, John Coltrane, Milt Hinton, Bob Brookmeyer, Art Farmer and a

Who's Who of the New York jazz scene is striking in it evocation of the

New York of the late fifties. From 1960, Russell began leading his own

sextets around the New York area and at festivals; he also toured

throughout the Midwest and Europe with his sextet. One of the important

albums of this time was “Ezz-Thetic,” which featured Eric Dolphy, Don

Ellis and Steve Swallow.

Disillusioned by his lack of recognition

and the meager work opportunities in America, he arrived in a wheel

chair in Scandinavia in 1964, but returned five years later in spiritual

health. In Sweden and Norway he found support for both himself and his

music. All his works were recorded by radio and TV, and he was

championed by Bosse Broberg, the adventurous Director of Swedish Radio,

an organization with which Russell maintains a close association and

admiration. While there, he heard and recorded a young Jan Garbarek,

Terje Rypdal, and Jon Christensen.

In 1969, he returned to the

States at the request of his old friend, Gunther Schuller to teach at

the newly created Jazz Department at the New England Conservatory where

Schuller was President. He continued to develop the Lydian Concept and

toured with his own groups. He played Carnegie Hall, the Village

Vanguard, the Bottom Line, Newport, Wolftrap, The Smithsonian, Sweet

Basil, the West Coast, the Southwest, and Europe with his 14 member

orchestra. He continued to compose extended works which defined jazz

composition. His 1985 recording, “The African Game,”one of the first in

the revived Blue Note label, received two Grammy nominations. Russell

has taught throughout the world, and has been guest conductor for

Swedish, Finnish, Norwegian, Danish, German and Italian radio.

In

1986, he was invited by the Contemporary Music Network of the British

Council to tour with an orchestra of American and British musicians,

which resulted in The International Living Time Orchestra, which has

been touring and performing since that time. Among the soloists of

stature are Stanton Davis, Dave Bargeron, Brad Hatfield, Steve Lodder,

Tiger Okoshi, and Andy Sheppard. The musicians have developed a rare

understanding of the music, astonishing audiences with fiery music both

complex and challenging, but added to the dynamism and electric power of

funk and rock. Russell himself is a tremendously visual leader, dancing

and forming architectural structures with his hands.

The Living

Time Orchestra has toured all over the world. Most recent projects

included a performance at the Barbican Centre in London and the Cite de

la Musique in Paris, augmented with string players from the U.K. and

France, the Theatre Champs-Elysees for the Festival D'automne in Paris,

the Glasgow International Festival, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Tokyo Music

Joy, the Library of Congress, Festivals of Umbria, Verona, Lisbon,

Milano, Pori, Bath, Huddersfield, Ravenna, Catania, North Sea, and many

more.

Russell has received the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship,

the National Endowment for the Arts American Jazz Master, been elected a

Foreign Member of the Royal Swedish Academy, two Guggenheim

Fellowships, the Oscar du Disque de Jazz, the Guardian Award, six NEA

Music Fellowships, the American Music Award, and numerous others.

http://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/11/arts/george-russell-his-big-band-and-his-big-theory.html?fta=y

It played at the San Diego Kool Jazz Festival, at the University of Arizona at Tempe, at the Kimo Theater in Albuquerque and in Houston. ''I was impressed by the open- mindedness and the receptivity of the people in the Southwest,'' Mr. Russell said by phone the other day from Boston, where he teaches at the New England Conservatory of Music. ''They're really open to new artistic experiences, and they're hungry for them.''

Focus Now on Boston Area

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/30/arts/music/30russell.html

http://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/11/arts/george-russell-his-big-band-and-his-big-theory.html?fta=y

GEORGE RUSSELL: HIS BIG BAND AND HIS BIG THEORY

by JOHN S. WILSON

November 11, 1983

New York Times

GEORGE RUSSELL is a jazz composer and a jazz

musician. But, primarily, he is a jazz theorist - possibly the first of

his kind. For almost 40 years, he has been developing, justifying and

clarifying his Lydian chromatic concept of tonal organization, which has

over the last two decades vitally affected both jazz and popular music.

The pianist and composer John Lewis has called it ''the first profound

theoretical contribution to come from jazz.''

A concert encompassing Mr. Russell's compositions,

from his pioneering modal piece for Dizzy Gillespie's big band in 1947,

''Cubana Be/ Cubana Bop,'' to his most recent work, ''The African

Game,'' will be given tomorrow evening at 11 at the Entermedia Theater,

Second Avenue at 12th Street (tickets, $10; students and the elderly $8,

at the box office or through Chargit, 944-9300). It will be played by

his new 14-piece group, the George Russell Big Band, which has just

completed the first United States tour that Mr. Russell has ever made

with a large ensemble.

It played at the San Diego Kool Jazz Festival, at the University of Arizona at Tempe, at the Kimo Theater in Albuquerque and in Houston. ''I was impressed by the open- mindedness and the receptivity of the people in the Southwest,'' Mr. Russell said by phone the other day from Boston, where he teaches at the New England Conservatory of Music. ''They're really open to new artistic experiences, and they're hungry for them.''

Focus Now on Boston Area

Although Mr. Russell has led big ensembles

sporadically since the late 1970's, usually made up largely of

established musicians, mostly based in New York, his present band is

focused on young musicians from the Boston area.

''I've always felt the need to have a band that had a

special kind of energy, who were sources of enthusiasm and musical

fire,'' he said. ''And I felt the need to have a band that was a little

more under my control, people who were not so much concerned with other

commitments that I couldn't reach them, get them together and make a

really tight band.''

''My music needs them,'' he went on. ''It's got to

be well rehearsed. My bands have to be tight. We don't just come in and

play off the wall. I find these young musicians a joy to work with

because, to them, going on the road is absolutely new. It's thrilling.

It's what they dreamed about. They envisioned music to be performed, and

they envisioned themselves participating in it. They produce the same

kind of fresh energy that I heard when I first heard Bill Evans in the

50's and when I heard Jan Garbarek and Terry Rybdal in Europe.''

From Drums to Writing

Mr. Russell, who is now 60, started in music as a

drummer, but after hearing Max Roach, who replaced him in Benny Carter's

orchestra in 1943, he decided to concentrate on writing. Shortly after,

hospitalized with tuberculosis, he began to evolve his Lydian chromatic

concept which has been described in Down Beat magazine as ''a 12-tone

concept based on the grading of the intervals on the basis of their

close-to-distant relationship to a central tone.'' In trying to describe

the concept for the lay listener, Mr. Russell envisions four

saxophonists taking a trip down the Mississippi in the guise of

steamboats.

''Coleman Hawkins would be a local steamboat that

stopped at every town and conveyed the local color,'' Mr. Russell

explained. ''Each town would be a chord, and the Hawkins steamboat would

be the scale that sounds the chord. Lester Young would be an express

steamboat stopping only at larger cities - tonic resting points to which

other towns lead. John Coltrane would be a rocket ship that is vocal,

like Hawkins, but it would jet up and down from town to town, while

Ornette Coleman would be a rocket ship that may not descend at all.''

Mr. Russell published the first of a proposed

three-volume explication of his chromatic concept in 1953. Since then he

has been working on a second volume in which he is trying to clarify it

and make it accessible to readers.

''When you are trying to communicate a new theory of

music,'' he said, ''the whole fight is to put the sentences together so

that other people understand them. Sometimes,'' he admitted, ''when I

read them back, I don't understand them.''

Mr. Russell's latest work, ''The African Game,''

which will take up the second half of his program tomorrow and which was

commissioned by the Massachusetts Council on the Arts and the Swedish

Broadcasting System, is based on Albert Einstein's remark that ''God

didn't play dice with the universe.''

''But I think he did once,'' Mr. Russell said. ''In

Africa, between four and eight million years ago, he said grace and then

rolled the dice on the human race, and a species emerged. I don't know

whether the Lord won or lost that game, but hopefully the game is won

and the human race won't blow itself to smithereens.''

JAZZ: A LOOK BACK BY GEORGE RUSSELL

by Jon Pareles

July 12, 1985

New York Times

THE composer George Russell is treating his stint

through Sunday at Sweet Basil, 88 Seventh Avenue South, as a full-scale

career retrospective, culminating with his latest large work, ''The

African Game.'' In Wednesday's first set, Mr. Russell and his 15-piece

Living Time Orchestra made their way through his first 23 years in the

jazz world, from the 1945 ''Cubano-Be Cubano-Bop'' to the 1968

''Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature.''

The constants in Mr. Russell's pieces are modal

harmonies and a distinctive way of layering material; the parts of his

arrangements slide into place like cantilevered architecture, with

trumpet, trombone, saxophone, synthesizer and percussion lines all

overlapping.

Mr. Russell also enjoys eclectic juxtapositions,

from jazz and Afro-Cuban rituals in ''Cubano-Be, Cubano-Bop'' to African

xylophones, electronic sounds, overblown saxophone, jazzy brass chords,

blues guitar and funk bass lines in the Electronic Sonata.

The Sonata, which anticipated much of the jazz-rock

of the 1970's, was the showpiece in Wednesday's first set. It builds

from buzzing electronic sounds, through oozy slow sections, through

brass fanfares, to a climactic battle between a funk vamp and an

accelerating riff.

The Living Time Orchestra, which is partially drawn

from Mr. Russell's students at the New England Conservatory of Music,

was most comfortable with the Sonata's jazz-rock. Mr. Russell's earlier

pieces, which are closer to mainstream jazz, didn't always swing enough.

Although the band hit all the notes, the layers of the music were

blurred. Of the featured soloists, the brooding trumpeter Stanton Davis

and the energetic saxophonist George Garzone stood out.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/30/arts/music/30russell.html

George Russell, Composer Whose Theories Sent Jazz in a New Direction, Dies at 86

George Russell, a jazz composer, educator and musician whose

theories led the way to radical changes in jazz in the 1950s and ’60s,

died on Monday in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston. He was 86

and lived in Boston.

The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease, said his wife, Alice.

Though he largely operated behind the scenes and was never well known to the general public, Mr. Russell was a major figure in one of the most important developments in post-World War II jazz: the emergence of modal jazz, the first major harmonic change in the music after bebop.

Bebop, the modern style pioneered by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and others, had introduced a new level of harmonic sophistication, based on rapidly moving cycles of dense and sometimes dissonant chords. Modal jazz, as popularized by Miles Davis and John Coltrane, sought to give musicians more freedom and to simplify the harmonic playing field by, in essence, replacing chords with scales as the primary basis for improvisation.

Mr. Russell explained the concept in great detail in a book that came to be considered the bible of modal jazz, “The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization for Improvisation.” Conceived during bouts with tuberculosis in the 1940s, the book was originally self-published in 1953 and published as a book six years later. A final revised edition was published as Volume 1 in 2001; Mr. Russell had been working on a second volume.

Mr. Russell’s concept could be difficult for readers to absorb. “When you are trying to communicate a new theory of music,” he told The New York Times in 1983, “the whole fight is to put the sentences together so that other people understand them. Sometimes, when I read them back, I don’t understand them.”

But the basic idea behind it was simple. He believed that a new generation of jazz improvisers deserved new harmonic techniques, and that traditional Western tonality was running its course. The Lydian chromatic concept — based on the Lydian mode, or scale, rather than the familiar do-re-mi major scale — was a way for musicians to improvise in any key, on any chord, without sacrificing the music’s blues roots.

Mr. Russell proposed that chords and scales were interrelated. He sought ways for an improvising musician to play more notes that fit harmonically with whatever he was playing; to put it another way, he was trying to develop a system in which there are no “wrong” notes.

Miles Davis most famously put Mr. Russell’s ideas into practice. His “Milestones,” written and recorded in 1958, swung back and forth between two scales, rejecting the rapid chord changes that had become prevalent in modern jazz. His landmark album “Kind of Blue,” recorded a year later, is widely regarded as the first great document of modal jazz.

Subsequent recordings by, among many others, the saxophonists John Coltrane (a participant in the “Kind of Blue” sessions) and Eric Dolphy (who also recorded with Mr. Russell), helped spread the gospel of modal jazz. Mr. Russell still stayed mostly behind the scenes, and, in later years, was primarily a teacher, but his fellow musicians acknowledged and appreciated his influence.

George Russell was born in Cincinnati on June 23, 1923, and grew up in a foster home. His adoptive father was a chef on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and his adoptive mother was a nurse. He played drums with the Boy Scouts’ drum-and-bugle corps and attended Wilberforce University in Ohio on a scholarship. At Wilberforce he played with the Collegians, the university’s imposing jazz and dance band. In 1941, while hospitalized for tuberculosis, he learned the science of harmony from a fellow patient. At that time he composed “New World” for the saxophonist and bandleader Benny Carter.

He later moved to New York to play drums with Carter’s band, but he gave up the instrument as soon as Max Roach was called in to replace him. “Max had it all on drums,” he said. “I decided that writing was my field.”

In 1947 he composed the modal introduction to “Cubano Be” and other sections of the multipart “Cubano Be, Cubano Bop,” an early example of Afro-Cuban jazz recorded by Gillespie. He later wrote “A Bird in Igor’s Yard,” an early experiment in classical-jazz crossover, for the clarinetist Buddy DeFranco.

He was part of the circle that convened around the arranger Gil Evans’s Manhattan apartment in the late 1940s, a group that included Miles Davis; returning to music after an illness, he wrote “Odjenar” and “Ezz-Thetic” for a Lee Konitz album recorded in 1951 that also included Davis.

In 1956 he began his own career as a recording artist and a bandleader with the album “The Jazz Workshop.” His other albums from that period included “New York, N.Y.” (1959) and “Ezz-Thetics” (1961).

In 1958 he taught at the Lenox School of Jazz in Massachusetts, run by the pianist and composer John Lewis, who called Mr. Russell’s Lydian chromatic concept “the first profound theoretical contribution to come from jazz.”

In 1964 Mr. Russell, who as a black man was dismayed by race relations in the United States, moved to Scandinavia. He returned in 1969 and joined the faculty of the New England Conservatory, where he taught until 2004.

He also began touring with his own groups, notably the Living Time Orchestra, a large international ensemble he led from the mid-1980s on, which experimented with all kinds of music, including funk, electronics and jazz-rock. A 21-piece version of that band recorded “The African Game,” an album for Blue Note in 1983.

Among the many awards Mr. Russell received were a MacArthur Foundation grant in 1989 and a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters fellowship in 1990.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his son, Jock Millgardh, of Los Angeles, and three grandchildren.

On the first few albums released under his name, Mr. Russell composed the music and led the ensemble but did not perform, and although he later played piano in the groups he led, he did not have a high opinion of himself as a pianist. “I don’t play the piano,” he once said. “I play the Lydian concept.”

Matt Stone/Boston Herald, via Associated Press

George Russell in 1999.

Multimedia

Video: 'The

Subject Is Jazz' | George

Russell and Ornette Coleman (Youtube.com)

Video: 'The

Subject Is Jazz' | George

Russell and Ornette Coleman (Youtube.com)

Blog

ArtsBeat

The latest on the arts, coverage of live events, critical reviews, multimedia extravaganzas and much more. Join the discussion.

The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease, said his wife, Alice.

Though he largely operated behind the scenes and was never well known to the general public, Mr. Russell was a major figure in one of the most important developments in post-World War II jazz: the emergence of modal jazz, the first major harmonic change in the music after bebop.

Bebop, the modern style pioneered by Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and others, had introduced a new level of harmonic sophistication, based on rapidly moving cycles of dense and sometimes dissonant chords. Modal jazz, as popularized by Miles Davis and John Coltrane, sought to give musicians more freedom and to simplify the harmonic playing field by, in essence, replacing chords with scales as the primary basis for improvisation.

Mr. Russell explained the concept in great detail in a book that came to be considered the bible of modal jazz, “The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization for Improvisation.” Conceived during bouts with tuberculosis in the 1940s, the book was originally self-published in 1953 and published as a book six years later. A final revised edition was published as Volume 1 in 2001; Mr. Russell had been working on a second volume.

Mr. Russell’s concept could be difficult for readers to absorb. “When you are trying to communicate a new theory of music,” he told The New York Times in 1983, “the whole fight is to put the sentences together so that other people understand them. Sometimes, when I read them back, I don’t understand them.”

But the basic idea behind it was simple. He believed that a new generation of jazz improvisers deserved new harmonic techniques, and that traditional Western tonality was running its course. The Lydian chromatic concept — based on the Lydian mode, or scale, rather than the familiar do-re-mi major scale — was a way for musicians to improvise in any key, on any chord, without sacrificing the music’s blues roots.

Mr. Russell proposed that chords and scales were interrelated. He sought ways for an improvising musician to play more notes that fit harmonically with whatever he was playing; to put it another way, he was trying to develop a system in which there are no “wrong” notes.

Miles Davis most famously put Mr. Russell’s ideas into practice. His “Milestones,” written and recorded in 1958, swung back and forth between two scales, rejecting the rapid chord changes that had become prevalent in modern jazz. His landmark album “Kind of Blue,” recorded a year later, is widely regarded as the first great document of modal jazz.

Subsequent recordings by, among many others, the saxophonists John Coltrane (a participant in the “Kind of Blue” sessions) and Eric Dolphy (who also recorded with Mr. Russell), helped spread the gospel of modal jazz. Mr. Russell still stayed mostly behind the scenes, and, in later years, was primarily a teacher, but his fellow musicians acknowledged and appreciated his influence.

George Russell was born in Cincinnati on June 23, 1923, and grew up in a foster home. His adoptive father was a chef on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and his adoptive mother was a nurse. He played drums with the Boy Scouts’ drum-and-bugle corps and attended Wilberforce University in Ohio on a scholarship. At Wilberforce he played with the Collegians, the university’s imposing jazz and dance band. In 1941, while hospitalized for tuberculosis, he learned the science of harmony from a fellow patient. At that time he composed “New World” for the saxophonist and bandleader Benny Carter.

He later moved to New York to play drums with Carter’s band, but he gave up the instrument as soon as Max Roach was called in to replace him. “Max had it all on drums,” he said. “I decided that writing was my field.”

In 1947 he composed the modal introduction to “Cubano Be” and other sections of the multipart “Cubano Be, Cubano Bop,” an early example of Afro-Cuban jazz recorded by Gillespie. He later wrote “A Bird in Igor’s Yard,” an early experiment in classical-jazz crossover, for the clarinetist Buddy DeFranco.

He was part of the circle that convened around the arranger Gil Evans’s Manhattan apartment in the late 1940s, a group that included Miles Davis; returning to music after an illness, he wrote “Odjenar” and “Ezz-Thetic” for a Lee Konitz album recorded in 1951 that also included Davis.

In 1956 he began his own career as a recording artist and a bandleader with the album “The Jazz Workshop.” His other albums from that period included “New York, N.Y.” (1959) and “Ezz-Thetics” (1961).

In 1958 he taught at the Lenox School of Jazz in Massachusetts, run by the pianist and composer John Lewis, who called Mr. Russell’s Lydian chromatic concept “the first profound theoretical contribution to come from jazz.”

In 1964 Mr. Russell, who as a black man was dismayed by race relations in the United States, moved to Scandinavia. He returned in 1969 and joined the faculty of the New England Conservatory, where he taught until 2004.

He also began touring with his own groups, notably the Living Time Orchestra, a large international ensemble he led from the mid-1980s on, which experimented with all kinds of music, including funk, electronics and jazz-rock. A 21-piece version of that band recorded “The African Game,” an album for Blue Note in 1983.

Among the many awards Mr. Russell received were a MacArthur Foundation grant in 1989 and a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters fellowship in 1990.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his son, Jock Millgardh, of Los Angeles, and three grandchildren.

On the first few albums released under his name, Mr. Russell composed the music and led the ensemble but did not perform, and although he later played piano in the groups he led, he did not have a high opinion of himself as a pianist. “I don’t play the piano,” he once said. “I play the Lydian concept.”

More Articles in

Arts »

A version of this article appeared in print on July 30, 2009, on page A29 of the New York edition.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/why-george-russell-will-always-live-in-time-george-russell-by-raul-dgama-rose.php?page=1

Why George Russell Will Always Live in Time

by

AllAboutJazz

AllAboutJazz

A measure of just how underrated a musician he was in his lifetime is reflected in the fact that even three days after he passed on most of the major publications had not even reported his death, much less celebrated his life in the glowing terms that he so richly deserved. Perhaps this was because oddly enough he may have spent a lifetime mostly in the quietude of musical intellectualism rather than in its practice. That is, after all how most may ultimately remember George Russell, born June 23, 1923—died July 27, 2009. He did author the most important work in jazz, The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization (Concept Publishing, 1953; Concept Publishing Ed. 1959), which is odd, because George Russell just happens to also rank as one of the most important composers, arrangers, conductors—not just a musical intellectual—in the history of jazz. Listen to his peers. Read what they have said. Men like Gunther Schuller and Gil Evans, Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, David Baker and scores of others. But trust fickle audiences and big record labels to have given him the short shrift in his lifetime.

George Russell wrote one of the earliest Afro-Cuban-Jazz classics, "Cubana-Be/Cubana-Bop," which was immortalized by Dizzy Gillespie. And the great conguero, Chano Pozo glorified it with a solo that will forever stick in the memory. But the song was a majestic piece of musical architecture that even Diz and Chano Pozo would agree that though Pozo's solo was such a lesson in drumming, nothing could detract from the melding of styles: the electrifying chopped rhythms of bebop and the beautifully cadenced, calculated stutter of Afro-Cuban polyrhythms.

That was in 1947. So although Russell did contribute one of the most important books in jazz theory, he matched that up amply and more and earlier too, with some exquisite music, "Cubana-Be/Cubana-Bop" and the later "A Bird in Igor's Yard" (1949), which took an impressionistic look at how the bebop of Bird and the ultra-radical concepts of Igor Stravinsky could become not-so-strange-bedfellows. And these were just the start of a glorious songbook.

The Theory

Still it pays to remember the theory. Russell's historic book marked a major advancement in jazz: the beginning of the Modal period that was to influence men like Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and later Ornette Coleman as well. Jazz musicians had been improvising on chord changes for decades before, whereas modal compositions emphasized more linear modes (like melody) rather than vertical ones (Chordal).

Russell's theory had united the Lydian—one of several ancient modes, which is a scale of unity for the tonic major chord—with a modern use of chromatics, so instead of a key signature dictating and limiting the musician's choice of notes, the tonal center of the piece of music became its center of gravity; the harmonic, chordal richness was still available but now the choice of notes became wider, almost limitless.

This concept—that melodic ideas assume sectional autonomy, independent of any harmonic progression—may have inadvertently begun with Lester Young. But Russell captured it in its entirety and made it stick with compositions to match. No wonder that men like John Lewis, Art Farmer and Ornette Coleman, among others, called it the single most important advance in Jazz theory.

Their paths crossed and forever changed the jazz geography of New York in the 1950s. So George Russell was also associated with Gil Evans. But if anything, Russell's seminal work was a big influence on the thing of Evans. And both men conceived their music on infinitely larger aural canvases. However, because of the complexity of Russell's work, they were less easy to grasp than Evans' music. Consequently Russell may have got the shorter end of the straw when it came to documentation and representation on major record labels in the US. That did not stop him.

Debut as leader

George Russell's musical debut as a bandleader came with the 1956 release of Jazz Workshop (Koch Records). The record featured some of his most enduring songs, "Ezz-thetics," "Concerto for Billy the Kid" and "Ye Hypocrite Ye Beelzebub." At the time it seemed inconceivable that this record was made by a septet, but it actually was. Art Farmer played trumpet, Bill Evans was on piano, there were two bassists and three drummers—Russell himself played chromatic drums and Osie Johnson was on wood drums. In 1959 he made New York, New York (Impulse) with John Coltrane, Max Roach and Evans. The record is a magnificent example of composition, arranging and performance. By 1960, Russell's adventurous spirit took flight. Jazz in the Space Age (Decca/GRP). This featured the two pianos of Bill Evans and Paul Bley together with a large ensemble. The music was made to order and its highlight was the three-part suite, "Chromatic Universe," an ambitious work that mixed punctiliously-written parts and free improvisation. In a second session for this record, Russell added trumpeter, Marky Markowitz, valve trombonist, Bob Brookmeyer and the slow, mysterious, "Waltz from Outer Space," which also incorporated an oriental sounding theme. This record represents some of Russell's finest work.

Throughout the 1960s George Russell was constantly changing, learning, evolving in his music and was also surrounding himself with extra-ordinary musicians. It was during this period that he produced two of his landmark recordings. The first was Outer Thought (OJC, 1960). A pivotal work, the record featured the art of Eric Dolphy on alto saxophone and bass clarinet, David Baker and Garnett Brown on trombones and two bassists—Chuck Israels and Steve Swallow. The drummers were Pete La Roca and Ivory Joe Hunter. This date also featured a George Russell discovery, the amazing Sheila Jordan on vocals. The group made splendid versions of "Ezz-Thetics" and "Stratusphunk."

The second record was Ezz-Thetics

(OJC, 1961). This was a truly classic record, with three Russell

originals as well as extraordinary versions of "'Round Midnight," (with a

jaw-dropping performance by Eric Dolphy), Miles Davis' "Nardis" and

David Baker's "Honesty." A year later came The Stratus Seekers (OJC) with "Blues in Orbit," later recorded by Gil Evans. Russell's musical catalogue also included The Outer View,

(OJC, 1962) on which he absolutely transformed Charlie Parker's "Au

Privave," a challenge to his musicians to stretch beyond their wildest

limits. There was also a most haunting version of "You are my Sunshine,"

by Sheila Jordan.

Europe and after

But in the early 1960s, disillusionment had set in and the composer moved to Europe. Here he taught music and performed, gathering together, teaching and influencing some of the most important musicians there. Jan Garbarek was one such musician and nominated him as one of his most important influences in his own playing and composing. Russell also celebrated his years in Europe with some of his mightiest work. At Beethoven Hall (Saba, 1965) was one such record, which brought the composer together with cornetist Don Cherry. Dipping in to his Lydian concepts in Europe, Russell turned in extraordinary versions of "Bag's Groove," "Confirmation" and "'Round About Midnight." Then he turned his attention to something even more daunting and produced Othello Ballet Suite and Electronic Sonata No. 1 (Flying Dutchman, 1968). This compelling work combined the jazz, classical idioms with Shakespeare. A year later he produced Electronic Sonata, 1968 (Soulnote, 1969). This two-part, 14-event piece featured a very young Jan Garbarek on tenor saxophone and Terje Rypdal on guitars. And The Essence of George Russell (1966) featured the first big band version of "Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature."

The 70s were marked by more teaching Trip to Prillaguri (ECM, 1973), more learning and more critical acclaim, especially in Europe. First with the ECM debut and later also with Listen to the Silence. A Mass for Our Time (Concept, 1974); and Vertical Form 6 (Soulnote, 1976).

By now, George Russell was entering a new stage in his career, one that was to characterize his later—and perhaps—his most important music conceptually. This was first heard on Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature (Strata East, 1980) was released in the US. This was an ambitious, elaborate composition and it blended bebop, free improvisation, Asian musical elements and the blues, electronics—including tapes and previously recorded performances. The collision was a brilliant—some say a historic—recording that ranks with Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz (Blue Note, 1959). Then came Live in an American Time Spiral (1982), a Village Vanguard recording that was a prelude to his next enormous work.

But absolutely nothing could prepare audiences for The African Game (Blue Note, 1983). This was Russell's Magnum opus. A highly eclectic, nine-event 45-minute suite for augmented big band that depicted the dawn of human civilization from—as we now know—the correct, African perspective. The work attempts, successfully, to embrace an enormous world of sound in an open, colorful manner, with several degrees of timbral unity and emotion, to keep the various idioms from flying out of control. This is a celebrated recording by Russell—his first in 13 years, made with his latest large ensemble, The Living Time Orchestra, a unit that was to be, with personnel changes, his last and greatest big band. That record was followed quickly by So What (Blue Note, 1983). Here too, the Living Time Orchestra responds to Russell's direction with the same kick that typified his Promethean career that began in the 50s and also featured one of his last long compositions, "Time Spiral."

Then again there was a long period of inactivity, before Russell made the first of three visits to the UK. Between 1986 and 1988, he performed and put together London Concerts Vols 1 & 2 (Label Bleu, 1989). Then the recording trail went cold again. But nothing really could prevent George Russell from staying close to the music he so loved. When Gunther Schuller had persuaded him to return to the US in 1969, he did not simply come back. He joined Schuller at the New England Conservatory of Music. He played festivals and he broadcasted in North America and in Europe. His last record was the gargantuan 80th Birthday Concert (Concept Publishing, 2005). Too bad he was stricken by Alzheimer's towards the end of his life, incapacitated not unlike that other compositional genius, Charles Mingus. But it may be that George Russell may not be done after all. Perhaps he will celebrate with a chair in the sky. While down here, we in the world will wait with bated breath.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/george-russell-the-story-of-an-american-composer-by-duncan-heining.php?page=1

New York, NY

http://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-george-russell29-2009jul29-story.html

FOR THE RECORD:

George Russell obituary: The obituary of jazz composer George Russell in Wednesday's Section A said that among his survivors was a son, Millgardh. His son's name is Jock Millgardh. —

Russell was a rare spokesman for the study of theoretical principles in an art form that emphasizes improvisation and spontaneity. His treatise “The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization” -- first published in 1953 -- had a significant effect on the growing fascination with modal and free improvisation surfacing in the late 1950s. Elements of the concept, which outlines methods by which improvisers can free themselves from the "tyranny of chords," as Russell described it, were a factor in the modal works present in Miles Davis' "Kind of Blue," the bestselling album in jazz history.

Russell's premise that jazz improvisation could reach beyond well-established harmonic foundations further validated the methods chosen by jazz artists such as John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, Herbie Hancock, Don Ellis, Wayne Shorter and others. His own compositions -- beginning with the startlingly inventive music on his mid-1950s breakthrough recording, "The Jazz Workshop," continuing with his small groups of the '60s, occasional large ensembles of the '80s, and the Living Time Orchestra that he led on and off until his death -- were constantly evolving displays of the expansive possibilities of his creative overview.

"My work," he told The Times after the MacArthur grant was awarded in 1989, "tries to achieve a kind of world view or synthesis of many kinds of musics, one that doesn't ignore the sounds of our time. My hope is that it's a complete music -- physical, emotional as well as thought-provoking."

George Allen Russell was born June 23, 1923, in Cincinnati, the adopted son of Joseph, a chef on the B&O Railroad, and Bessie, a nurse. Drawn to music at an early age, he sang a number with Fats Waller at age 7 and played drums in a Boy Scout drum and bugle corps. After receiving a scholarship to Wilberforce University, he was called up for the World War II draft. But when tuberculosis was diagnosed in his examination, he was hospitalized, serendipitously with a fellow patient who instructed him in the fundamentals of music theory.

Briefly working as a jazz drummer after his release, Russell decided to explore other areas of music after hearing Max Roach play the drums, and wound up in New York City. By the mid-1940s, he had become part of an adventurous group of young musicians -- Davis, Gerry Mulligan, John Lewis, John Benson Brooks among them -- who frequented Gil Evan's West Side apartment. Told by Davis that he wanted to "learn all the changes," Russell interpreted the remark as a quest to find new ways to approach harmony, and he began to work on his Lydian Concept. Applying the principles he was discovering, he composed "Cubana Be/Cubana Bop" -- early examples of the blending of jazz and Afro-Cuban rhythms -- for Dizzy Gillespie's big band.

In the 1950s, while still supporting himself with odd jobs, he wrote and recorded "The Jazz Workshop" album, which -- combined with the publication of the Lydian Concept -- thoroughly established his credibility as a jazz artist. A commission from the Brandeis Jazz Festival followed, along with the large ensemble album, "New York, New York," which showcased Russell compositions performed by an all-star assemblage that included Coltrane, Bill Evans, Jon Hendricks and others.

Russell led his own sextets in the 1960s, but by mid-decade, the music industry's turn toward rock music had diminished the employment potential for jazz players. He moved to Sweden until 1969, then returned to teach at the New England Conservatory.

A second volume of his Lydian Concept -- "The Art and Science of Tonal Gravity" -- was published in 2001.

He is survived by his wife, Alice; a son, Millgardh; and three grandchildren.

Heckman is a freelance writer.

news.obits@latimes.com

When composer George Russell died in 2009, plenty of the world’s musicians and listeners remained indifferent to his achievements - or were still scratching their heads about them - close on 60 years after his revolutionary methods began transforming jazz. But plenty of others - Ornette Coleman and Jan Garbarek among them - knew exactly why he mattered. Russell didn’t believe that European music theory, with its roots in the major/minor scale system, and the cadential "urge" of its seven notes toward resolutions, could say much that was useful about jazz. So he shifted the emphasis from cadences and chords to the drifting modes of an updated medieval church music, to notions of "ingoing and outgoing" or "gravitational pull" rather than "tension and resolution".

His work inspired the likes of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Gil Evans and Ornette Coleman, and it inspires new artists still - including young US saxophonist John O’Gallagher, a developer of Russell’s theories who has applied jazz improv to serialist composer Anton Webern’s music, and who plays Birmingham and London next week. O’Gallagher’s pianist will be London-based composer and teacher Hans Koller, himself a student of the Russell approach who nonetheless admits that first contact with it can just seem "too weird, super-confusing. We learn piano in the key of C, but with Russell, everything’s a fourth away from where it should be. But the more you get into it, you hear the beauty in it. You can use all 12 notes, the black notes and the white, as long as you have structures, and he offered those."

Russell first published his Lydian Concept of Chromatic Organisation in 1953, and its influence soon spread. Kind of Blue’s So What has two modes replacing a chord sequence. Russell’s All About Rosie has one pentatonic mode superimposed on another, and that idea of bi-modality was central to Coltrane’s later music. When Jan Garbarek, at 19, began being mentored by Russell, he realised he could tap into his own Norwegian folk music this way, using its pentatonic modes. "So rather than a constant urge to cadence, the western idea that the next thing has to keep happening quickly," Koller continues, "you can stay in one colour as long as you want, then move to another. Russell thought of a mode as colour rather than a function - or as colour on top of function, because the beauty of it is that you can combine this approach and a jazz-standards one, and have the best of both worlds. That’s why this doesn’t turn into contemporary-classical music, but keeps the jazz earthiness, in jazz you don’t throw anything out, whereas the contemporary-classical guys wanted to remove things that had been there before. And that’s why it’s liberating, and why I love jazz more than anything else."

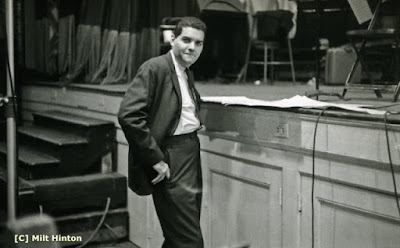

The NBC TV show The Subject Is Jazz caught Russell at work just as his message was beginning to be heard by likeminded musicians - five minutes into a 1958 edition of the show, he appears on some of his classic themes with pianist Bill Evans, trumpeter Art Farmer and others, representing The Future of Jazz.

https://www.macfound.org/fellows/377/

"George Russell: The Composer Who Thought Outside the Box"

George Russell , 1989 MacArthur Fellow

"George Russell, Composer Whose Theories Sent Jazz in a New Direction, Dies at 86"

George Russell , 1989 MacArthur Fellow

"George Russell Dies at 86; Composer Influenced the Evolution of Jazz"

Los Angeles Times

George Russell , 1989 MacArthur Fellow

https://necmusic.edu/faculty/george-russell

George Russell (1923–2009) was one

of the charter faculty who led the NEC jazz studies program, beginning

in 1969 and beyond his official retirement in 2004, when he became a

Distinguished Artist-in-Residence Emeritus. He remained a cornerstone of

the NEC jazz community through his death on July 27, 2009. Russell, his

music, and his ideas are inextricably woven into the international

history and culture of jazz and music that has learned from jazz, and

his legacy is found in NEC's all-embracing approach to the study of

music.

For almost 40 years, every jazz student at NEC was exposed to Russell’s music and ideas, even if they did not work with him directly as a studio teacher. Up to his retirement, Russell spent almost every spring semester with the players of the NEC Jazz Orchestra, studying and rehearsing his music for a traditional end-of-semester concert. Due to the aleatory elements in Russell’s music, this nuanced composer/performer experience prepared generations of NEC alumni to be uniquely qualified interpreters of these large-scale works.

A hugely influential, innovative figure in the evolution of modern jazz, Russell was one of its greatest composers, and its most important theorist. His 1953 book The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization is credited as a great pathbreaker into modal music, as pioneered by Miles Davis and John Coltrane. His second volume on the Lydian Concept, The Art and Science of Tonal Gravity, was published in 2001. All of the music’s most important developments—from modal improvisation to electronics, African polyrhythms to free form, atonality to jazz rock—have taken cues from Russell’s pioneering work.

Russell's Living Time Orchestra has performed throughout the world, including the Barbican Centre and Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, the Festival d’Automne and Cîté de la Musique in Paris, and Tokyo Music Joy. His career as a leader is preserved on more than 30 recordings, including work with such musicians as Bill Evans, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, and Jan Garbarek.

Among Russell's awards are a MacArthur Fellowship, the NEA American Jazz Master Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships, six NEA grants, three Grammy nominations, the American Music Award, the British Jazz Award, the Kennedy Center Living Jazz Legend Award, the Swedish Jazz Federation Lifetime Achievement Award, and election to the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. NEC bestowed an honorary Doctor of Music degree on George Russell in 2005.

Russell's commissions include the British Council, Swedish Broadcasting, the Glasgow International Festival, the Barbican Centre, and the Massachusetts Council on the Arts. He taught throughout the world, and was a guest conductor for Finnish, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, German, and Italian radio. Russell has been the subject of documentaries by NPR, NHK Japan, Swedish Broadcasting, and the BBC.

in photo: George Russell conducts in NEC's Jordan Hall in 2003 as part of celebration of Jordan Hall centennial (photo by Tom Fitzsimmons)

More about George Russell.

http://www.furious.com/perfect/georgerussell.html

Check out the rest of PERFECT SOUND FOREVER

http://jazzprofiles.blogspot.com/2016/06/george-russell-finds-musics-missing.html

COPYRIGHT by BOB BLUMENTHAL

Surrounded by the music of the black church and the big bands which played on the Ohio Riverboats, and with a father who was a music educator at Oberlin College, he started playing drums with the Boy Scouts and Bugle Corps, receiving a scholarship to Wilberforce University, where he joined the Collegians, a band noted as a breeding ground for great jazz musicians including Ben Webster, Coleman Hawkins, Charles Freeman Lee, Frank Foster, and Benny Carter. Russell served in that band at the same time as another noted jazz composer, Ernie Wilkins. When called up for the draft at the beginning of World War II, he was quickly hospitalized with tuberculosis, where he was taught the fundamentals of music theory by a fellow patient.

In 1945–46, Russell was again hospitalized for tuberculosis for 16 months. Forced to turn down work as Charlie Parker's drummer, during that time he worked out the basic tenets of what was to become his Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, a theory encompassing all of equal-tempered music which has been influential well beyond the boundaries of jazz. The first edition of his book was published by Russell in 1953, while he worked as a salesclerk at Macy's. At that time, Russell's ideas were a crucial step into the modal music of John Coltrane and Miles Davis[1] on his classic recording, Kind of Blue, and served as a beacon for other modernists such as Eric Dolphy and Art Farmer.

While working on the theory, Russell was also applying its principles to composition. His first famous composition was for the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra, the two-part "Cubano Be, Cubano Bop" (1947) and part of that band's pioneering experiments in fusing bebop and Cuban jazz elements;[4] "A Bird in Igor's Yard" (a tribute to both Charlie Parker and Igor Stravinsky) was recorded in a session led by Buddy DeFranco the next year.[5] Also, a lesser known but pivotal work arranged by Russell's was recorded in January 1950 by Artie Shaw entitled "Similau"[6][7] that employed techniques of both the works done for Gillespie and DeFranco.

Russell began playing piano, leading a series of groups which included Bill Evans, Art Farmer, Hal McKusick, Barry Galbraith, Milt Hinton, Paul Motian, and others. Jazz Workshop was his first album as leader, and one where he played relatively little, as opposed to masterminding the events (rather like his colleague Gil Evans). He was to record a number of impressive albums over the next several years, sometimes as primary pianist.

In 1957, Russell was one of six jazz musicians commissioned by Brandeis University to write a piece for their Festival of the Creative Arts. He wrote a suite for orchestra, All About Rosie, which featured Bill Evans among other soloists, and has been cited as one of the few convincing examples of composed polyphony in jazz.[8]

Members of the orchestra on his 1958 extended work, New York, N.Y., included Bill Evans, John Coltrane, Art Farmer, Milt Hinton, Bob Brookmeyer, and Max Roach, among others, and featured wrap-around raps by singer/lyricist Jon Hendricks. Jazz in the Space Age (1960) was an even more ambitious big band album, featuring the unusual dual piano voicings of Bill Evans and Paul Bley. Russell formed his own sextet in which he played piano. Between 1960 and 1963, the Russell Sextet featured musicians like Dave Baker and Steve Swallow and memorable sessions with Eric Dolphy (on Ezz-thetics) and singer Sheila Jordan (their bleak version of "You Are My Sunshine" on The Outer View (1962) is highly regarded).

This Scandinavian period also provided opportunities to write for larger groupings, and Russell's larger-scale compositions of this time pursue his idea of "vertical form", which he described as "layers or strata of divergent modes of rhythmic behaviour". The Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature, commissioned by Bosse Broberg of Swedish Radio for the Radio Orchestra, was first recorded in 1968, as an extended work recorded with electronic tape. It continued Russell's continuing exploration of new approaches and new instrumentation.

Russell returned to America in 1969, when Gunther Schuller assumed the presidency of the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston and appointed Russell to teach the Lydian Concept in the newly created jazz studies department, a position he held for many years. As Russell toured with his own groups, he was persistent in developing the Lydian Concept. He played the Bottom Line, Newport, Wolftrap, The Village Vanguard, Carnegie Hall, Sweet Basil and more with his 14-member orchestra.[10]

With Living Time (1972), Russell reunited with Bill Evans to offer a suite of compositions which represent the stages of human life. His Live in an American Time Spiral featured many young New York players who would go on to greatness, including Tom Harrell and Ray Anderson. When he was able to form an orchestra for his 1985 work The African Game, he dubbed it the Living Time Orchestra. This 14-member ensemble toured Europe and the U.S., doing frequent weeks at the Village Vanguard, and was praised by New York magazine as "the most exciting orchestra to hit the city in years."

The work The African Game, a 45-minute opus for 25 musicians, was described by Robert Palmer of The New York Times as "one of the most important new releases of the past several decades" and earned Russell two Grammy nominations in 1985.

Russell wrote nine extended pieces after 1984, among them: Timeline for symphonic orchestra, jazz orchestra, chorus, klezmer band and soloists, composed for the New England Conservatory's 125th anniversary; a re-orchestration of Living Time for Russell's orchestra and additional musicians, commissioned by the Cité de la Musique in Paris in 1994; and It's About Time, co-commissioned by The Arts Council of England and the Swedish Concert Bureau in 1995.

In 1986, Russell toured with a group of American and British musicians, resulting in The International Living Time Orchestra, a group who still tours and performs today. He played with Dave Bargeron, Steve Lodder, Tiger Okoshi, Mike Walker, Brad Hatfield, and Andy Sheppard.[10]

It was a remark made by Miles Davis in 1945 when Russell asked him his musical aim that led Russell on a quest which was to lead to his theoretical breakthrough. Davis answered that his musical aim was "to learn all the changes." Knowing that Davis already knew how to arpeggiate each chord, Russell reasoned that he really meant that he wanted to find a new and broader way to relate to chords. As music scholars Cooke and Horne wrote:

The Lydian Chromatic Concept was the first codified original theory to come from jazz. Musicians who assimilated Russell's ideas expanded their harmonic language beyond that of bebop, into the realm of post-bop. Russell's ideas influenced the development of modal jazz, notably in the album Jazz Workshop (1957, with Bill Evans and featuring the "Concerto for Billy the Kid") as well as his writings. Miles Davis also pushed into modal playing with the composition Miles on his 1957 album Milestones. Davis and Evans later collaborated on the 1959 album Kind of Blue, which featured modal composition and playing. John Coltrane explored modal playing for several years after playing on Kind of Blue.

His Lydian Concept has been described as making available resources rather than imposing constraints on musicians.[12] According to the influential 20th century composer Toru Takemitsu, "The Lydian Chromatic Concept is one of the two most splendid books about music; the other is My Musical Language by Messiaen. Though I'm considered a contemporary music composer, if I dare categorize myself as an artist, I've been strongly influenced by the Lydian Concept, which is not simply a musical method—we might call it a philosophy of music, or we might call it poetry."[13]

Europe and after

But in the early 1960s, disillusionment had set in and the composer moved to Europe. Here he taught music and performed, gathering together, teaching and influencing some of the most important musicians there. Jan Garbarek was one such musician and nominated him as one of his most important influences in his own playing and composing. Russell also celebrated his years in Europe with some of his mightiest work. At Beethoven Hall (Saba, 1965) was one such record, which brought the composer together with cornetist Don Cherry. Dipping in to his Lydian concepts in Europe, Russell turned in extraordinary versions of "Bag's Groove," "Confirmation" and "'Round About Midnight." Then he turned his attention to something even more daunting and produced Othello Ballet Suite and Electronic Sonata No. 1 (Flying Dutchman, 1968). This compelling work combined the jazz, classical idioms with Shakespeare. A year later he produced Electronic Sonata, 1968 (Soulnote, 1969). This two-part, 14-event piece featured a very young Jan Garbarek on tenor saxophone and Terje Rypdal on guitars. And The Essence of George Russell (1966) featured the first big band version of "Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature."

The 70s were marked by more teaching Trip to Prillaguri (ECM, 1973), more learning and more critical acclaim, especially in Europe. First with the ECM debut and later also with Listen to the Silence. A Mass for Our Time (Concept, 1974); and Vertical Form 6 (Soulnote, 1976).

By now, George Russell was entering a new stage in his career, one that was to characterize his later—and perhaps—his most important music conceptually. This was first heard on Electronic Sonata for Souls Loved by Nature (Strata East, 1980) was released in the US. This was an ambitious, elaborate composition and it blended bebop, free improvisation, Asian musical elements and the blues, electronics—including tapes and previously recorded performances. The collision was a brilliant—some say a historic—recording that ranks with Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz (Blue Note, 1959). Then came Live in an American Time Spiral (1982), a Village Vanguard recording that was a prelude to his next enormous work.

But absolutely nothing could prepare audiences for The African Game (Blue Note, 1983). This was Russell's Magnum opus. A highly eclectic, nine-event 45-minute suite for augmented big band that depicted the dawn of human civilization from—as we now know—the correct, African perspective. The work attempts, successfully, to embrace an enormous world of sound in an open, colorful manner, with several degrees of timbral unity and emotion, to keep the various idioms from flying out of control. This is a celebrated recording by Russell—his first in 13 years, made with his latest large ensemble, The Living Time Orchestra, a unit that was to be, with personnel changes, his last and greatest big band. That record was followed quickly by So What (Blue Note, 1983). Here too, the Living Time Orchestra responds to Russell's direction with the same kick that typified his Promethean career that began in the 50s and also featured one of his last long compositions, "Time Spiral."

Then again there was a long period of inactivity, before Russell made the first of three visits to the UK. Between 1986 and 1988, he performed and put together London Concerts Vols 1 & 2 (Label Bleu, 1989). Then the recording trail went cold again. But nothing really could prevent George Russell from staying close to the music he so loved. When Gunther Schuller had persuaded him to return to the US in 1969, he did not simply come back. He joined Schuller at the New England Conservatory of Music. He played festivals and he broadcasted in North America and in Europe. His last record was the gargantuan 80th Birthday Concert (Concept Publishing, 2005). Too bad he was stricken by Alzheimer's towards the end of his life, incapacitated not unlike that other compositional genius, Charles Mingus. But it may be that George Russell may not be done after all. Perhaps he will celebrate with a chair in the sky. While down here, we in the world will wait with bated breath.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/george-russell-the-story-of-an-american-composer-by-duncan-heining.php?page=1

George Russell: The Story of an American Composer

by

This article, adapted by the author, appears in Chapter 4 of George Russell: The Story of an American Composer, by Duncan Heining (Scarecrow Press, 2010).

New York, NY

It

was May 1945, the war was still on, Bebop was at its height in New York

and George Russell and his two friends, Little Bird and Little Diz, had

just arrived in the city. With fifteen dollars in their collective

pocket, they faced a simple choice. Two of them could get a room but the

third was out on the streets. So, they moved into the Hotel Barada,

right behind the Apollo at 125th and 7th Ave. and Russell would sneak in

after dark to share the room. After a week the money had run down to

five dollars and, to make it last, they moved into a cheaper room at the

Braddock Hotel, on 134th St, one without windows. It was high summer,

which in New York is about as humid and sticky as it gets in the

Northern hemisphere, and Russell decided he would be more comfortable

sleeping in nearby Gracie Park.

It all sounds quite jolly, one of those experiences that was hell at the time but looking back was character-forming or something. The trio would eat at a local Catholic Mission for fifty cents but even that got too expensive.

What strikes about Russell's account, and that of others such as Gil Evans and Gerry Mulligan, is the openness of that group. Bebop was a virtuoso music, rhythmically and harmonically adventurous and often played at breakneck tempos that discouraged all but the most confident and able. Yet, despite the cool, the hip vernacular, the drugs, the clothes and the attitude, all meant to exclude the straight world, genuine talent, black or white, was welcomed. As Russell said to this author, "The one entrée to the group was talent. So, people who later on were talented were welcomed." And musicians shared their ideas and knowledge, which was great for someone like the twenty-two year old mid-Westerner, as Russell told Ian Carr, "It didn't last but it was the prevailing feeling at the time, a feeling of great openness, you know."

Much of that spirit Russell attributes to Charlie Parker.

Although he had only been 'on the Street' a few months, Russell had by now met Miles Davis as well and by his account had been invited to join Charlie Parker's quintet on drums. That room on 48th was used by just about everyone playing the clubs around 52nd.

For some reason, Russell was unable to keep the apartment on 48th, probably because he could not make the rent. So, he moved in with a couple of other musicians who had a place over on the West side of Manhattan around the seventies. "We lived on cream of wheat every morning. We lived on Riverside Drive in a huge apartment but we didn't have any money. I remember laying out in the sun one day on Riverside Drive and this big [gurgling] in my chest started."

Russell had already been to the doctor with a nagging cough that had been diagnosed as a 'bad cold.' It was, however, his un-cured tuberculosis flaring up and that gurgling sensation was 'a haemorrhage coming on.' By now it was late summer of 1945. In just a few months, Russell had established himself within that group of musicians who were shaping the new Jazz but now he was really in a bad way. He was admitted to St. Joseph's Catholic Hospital in the Bronx and that was to be his home for the next 15 months. This time there was no private room and this time the nurses, mainly elderly nuns, reserved their hands for more strictly medical procedures. With fifteen chronically and critically ill men on the ward, Russell would turn over in his corner bed, face the wall and go deep inside his own thoughts. And that puzzle that Miles had set for him kept coming back to him.

In repeatedly playing these scales, it as if Russell was engaged in a scientific experiment, weighing notes against each other, examining sounds and tones in the most minute detail and testing their correspondence to each other. As he told Ian Carr, "And I finally decided that the major scale just doesn't cut it. It doesn't make it, you know. It doesn't sound a unity with its major chord. And then I began to look for reasons why it didn't. And then I found it wasn't a ladder of fifths. It wasn't a ladder of perfect fifths like the Lydian on the tonic because the Lydian did sound a unity. But the major scale always sounded this effortful feeling of striving for the tonic, striving to become a unity."

Russell then relates this to himself and his own sense of the world.

Apart from the diversion of occasional visits from Miles, Dizzy, Max and J.J. Johnson, Russell had little to do but continue his experiments with chords and scales. The only satisfactory way of describing Russell's breakthrough discovery is to allow him to tell it in his owns words, as he explained to Vivian Perlis.

In The Black Composer Speaks, Russell was asked what features of his music are uniquely 'black.' He replied these were the substitution of F# for F Natural and the conviction that the Lydian scale is "much more scientifically profound scale upon which to base a world of music." In relation to a question about the role of the black artist, he responded that it was to "show a new path to human evolution based upon his ancient high African Heritage." Russell had always been aware that what he was exploring was a different set of musical traditions that drew on Folk musics from around the world as opposed to the formalised musical structures of Western music. The point he is making above refers to his understanding of humanity's roots and origins in Africa, a point he would later make in interview with Ben Young of WKCR and even more eloquently in his work The African Game. What Russell is saying here is that the African-American brought with her/him a different set of musical ideas based on a different tradition and through Jazz and Blues gave those to America and the world. He is not making a political statement in any simplistic sense but is commenting on what he sees as the scientific basis of music and of his theories and their basis in natural world and the very origins of our species.

The scientific foundations of Russell's ideas are open to question. However, the approach he describes below and elsewhere of reading, studying and of experimenting musically, observing and reflecting is a scientific one. In terms of scientific research, this process would be described as inductive, that is observation leading to theorisation rather than deductive, which involves reasoning from a priori assumptions.

Grand theories, that is theories that make claims for comprehensiveness within a whole area such as Marx in Economics or Freud in Psychology, invite criticism. We will see later that Russell and his ideas have their critics. However, it suffices to note here that Russell was hearing something different in music, as well as hearing music differently. This led him to question the relationship, as traditionally understood, between chords and scales, between scales and their tonic, between different scales and how a musician or composer might move between these different scales in ways that challenged accepted notions of the antagonistic relationship between tonality and atonality.

As an aside, one of the other patients on the ward Russell befriended was Eddie Roane, the trumpeter who had played with Louis Jordan. Roane died of tuberculosis in Russell's arms. Russell was truly fortunate to survive. In fact, at one point, he recalls a priest coming to give him the last rites and shouting at him that he (Russell) was an atheist and to get lost.

We have already noted Campbell's identification of the 'Refusal of the Call' as an element within the Hero myth. Here it may be added that other aspects that he refers to are near death experiences, the inward journey and seeking of knowledge. (32) Once again, that does not make Russell's account inaccurate or mythical in itself. It may, however, mean that the construction or form of the tale has certain mythologized features to it. A more prosaic telling is actually no less remarkable. Had Russell not survived we would simply not have the Lydian Concept, Jazz would have missed out on his contribution to its development, music like All About Rosie and The African Game would have been denied to us and this book would not be written! Circumstances were such that Russell did survive and his achievements speak both of his efforts, then and later, and of our good fortune.

Russell came out of hospital around Xmas 1946 and went to stay with Max Roach and his family. Keeping track of Russell's living arrangements from the late forties into the early fifties is a demanding activity in itself. However, for much of the next period he lived variously with Roach or at one point with Roach's mother. Living conditions were quite squalid according to Russell but he is still grateful for Roach's support and generosity. He was in all respects treated as a member of the family.

Premiered at Carnegie Hall at a concert promoted by British-born critic Leonard Feather on 29th September 1947, Russell conducted Dizzy Gillespie's Big Band in front of a sell-out crowd. Charlie Parker played with Gillespie in a quintet at the same gig but sat in the audience for Russell, Gillespie and Pozo's number, and also for John Lewis}' Toccata for Trumpet. Ella Fitzgerald also sang with Gillespie and as Down Beat's headline put it—"Despite Bad Acoustics, Gillespie Concert Offers Some Excellent Music." Its critic Michael Levin saw Cubano Be, Cubano Bop as a definite 'stand-out,' writing,

The African-American contingent in the audience, however, were embarrassed by this. Looking back on the incident, Russell identifies this as a consequence of the way black people were taught to be ashamed of their culture and later in his conversation with Ian Carr, he relates this directly to a process of ethnocentricity that is 'literally messing up the planet.'