SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2018

VOLUME FIVE NUMBER ONE

ORNETTE COLEMAN

Featuring the Music and Aesthetic Visions of:

TYSHAWN SOREY

(November 4-10)

JALEEL SHAW

(November 11-17)

COUNT BASIE

(November 18-24)

NICHOLAS PAYTON

(November 25-December 1)

JONATHAN FINLAYSON

(December 2-8)

JIMMY HEATH

(December 9-15)

BRIAN BLADE

(December 16-22)

RAVI COLTRANE

(December 23-29)

CHRISTIAN SCOTT

(December 30-January 5)

GIL SCOTT-HERON

(January 6-12)

MARK TURNER

(January 13-19)

CRAIG TABORN

(January 20-26)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/mark-turner-mn0000331567/biography

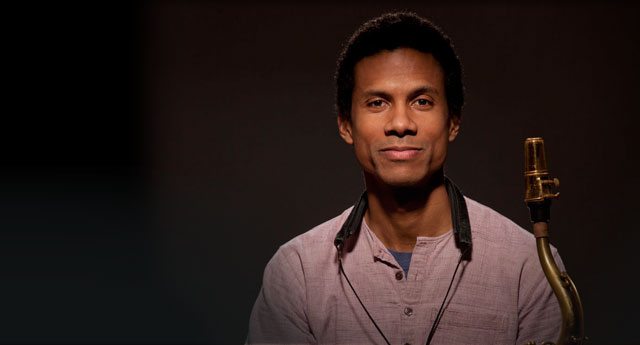

Mark Turner

(b. November 10, 1965)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

Mark Turner is a post-bop tenor saxophonist most influenced by John Coltrane, but also notably Warne Marsh. Born November 10, 1965 in Ohio, Turner

was raised in California and initially studied visual arts at Long

Beach State, but decided instead to pursue music and transferred to

Berklee. Turner moved to New York and worked with James Moody, Jimmy Smith, the TanaReid Quintet, Ryan Kisor, Jonny King, Leon Parker, and Joshua Redman. He recorded his first album as a leader, Yam Yam, in 1994; the follow-up, a self-titled effort, did not appear until 1998. In This World appeared later that same year, and in early 2000, he resurfaced with The Ballad Session. Cafe Oscurra appeared a year later. In 2004, the saxophonist teamed with bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard for the trio album Fly. Starting with 2012's All Our Reasons, Turner began a recording relationship with the storied European label ECM that resulted in several more albums, including 2012's Year of the Snake and 2014's piano-less quartet recording, Lathe of Heaven.

Arts

The Best Jazz Player You've Never Heard

THE tenor saxophonist Mark Turner is possibly jazz's premier player, and at the same time he's a very typical one.

He

isn't getting rich. He isn't becoming famous. He has no publicist. He

doesn't even have a record contract. He had one for three years, but the

label, Warner Brothers, dropped him -- the way the major record labels

are dropping mainstream jazz artists right and left these days. Yet Mark

Turner, who is 36, keeps playing where he can, and his stature in the

jazz world keeps growing. This month, for the first time, he'll appear

in the JVC Jazz Festival in New York, which starts today.

A few months ago I had an experience that starkly demonstrated how important Mr. Turner is among younger musicians. While reporting on the Thelonious Monk Institute saxophone competition in Washington -- an annual contest that has become something like the Van Cliburn competition of jazz -- I heard 15 young players. As expected, most of them drew much of their sound from one source: John Coltrane. There was no mistaking that gruff, keening tone, those scale-based patterns.

But to my surprise, the second most prevalent sound among the 15 was very different. It was lighter, more evenly produced from the bottom to the very top of the horn, in long, chromatic strokes. At first I thought it was the sound of Warne Marsh. But there was no reason to think that Marsh, who died in 1987 and was always a minority taste, had suddenly become au courant. Then I realized that it was the sound of Mark Turner.

Outside of jazz's small world, however, I can't remember holding a conversation with anyone who has heard of Mr. Turner. This is how it often works in serious mainstream jazz, a discipline that bears comparison to serious painting or poetry in that it is often accused of being dead yet continues to evolve and even find a modest audience.

Mr. Turner should have his own regular band, as the more successful artists in jazz do. (He'll play with Ben Street on bass and Jeff Ballard on drums in his JVC show at the Village Vanguard on June 27 -- a trio that looks as if it may become regular in time.) Within the limited circle of jazz clubs across the country, Mr. Turner tends to play with young, top-shelf rhythm-section musicians like the drummers Brian Blade and Nasheet Waits, the bassists Larry Grenadier and Reid Anderson, the pianists Ethan Iverson and Brad Mehldau. In the past, he hasn't been offered enough steady work to keep musicians like those with him. To maintain a high-level band, you need an international audience and a lot of festival gigs. To get a lot of festival gigs, it helps to have a major-label record deal.

Mr. Turner lost his in December, after four releases. At first, his association with Warner Brothers looked as if it could last. He is a standard-bearer. His music is intellectual and rigorously composed, defined by long, flowing, chromatically complex lines that keep their stamina and intensity as they stay dynamically even. He has learned how to play the highest reaches of his instrument, the altissimo register, with a serene strength, never shouting for the effect that audiences love. The overwhelming sense about Mr. Turner is that he wants to get on with his work.

Musicians can't say a negative word about him. (''His music is the freshest thing around,'' said the singer Luciana Souza, an accomplished composer. ''I want to write like that. It's 'out' music that still sounds very musical and consonant.'') Mr. Turner writes his own material; he is lean and handsome; he has a thrift-store-cool fashion sense: large-collar shirts, cardigans and 1970's earth tones.

But in the end, Mr. Turner's music may have been too rigorous for Warner Brothers and he isn't the sort who might turn his music around to sell records. There was some disconnection between artist and label. An album, ''Ballad Session,'' conceived by Warner Brothers as a corrective to the notion that Mr. Turner was all intellect, ended up becoming a collection of candlelight jazz standards like ''Skylark'' and ''All or Nothing at All.'' Mr. Turner had originally wanted to record an album of ''slow music,'' as he called it -- pieces from all over the map, including original tunes and works by Olivier Messaien and Aphex Twin.

Finally, as explained by Matt Pierson, senior vice president of jazz at Warner Brothers, it came down to brute numbers. The albums didn't sell well (in major-label terms, that means at least 10,000 copies). The company couldn't justify the cost of the marketing that it routinely puts into its releases, which can run to $50,000 -- easily twice what an independent label would spend.

''It's fine,'' Mr. Turner said of the end of his relationship with the label. ''I was considering trying to get out of it myself. Nothing against Warner, but I feel relieved and open and free.''

Since being dropped by Warner Brothers, Mr. Turner says he has had no calls from record labels.

Some jazz recording executives say that broader audiences don't have the patience to deal with compositions like his -- moody, with long, difficult-to-remember themes. But the fact is that Mark Turner is a great jazz musician during a particularly bad time for being a great jazz musician.

Jazz does not stand alone anymore as a viable, self-sustaining department within most major record companies. Most are following the successful example of Nonesuch, which has sprinkled a few jazz artists among its list of new classical music, singer-songwriter rock, Cuban and African oldies and chic unclassifiables like Laurie Anderson. Since the mid-90's, when major labels were let down by the failure of a mostly press-driven ''renaissance'' that had encouraged them to sign young jazz bandleaders in the vein of Wynton Marsalis and Terence Blanchard, jazz is now seen by record executives as one of many possible kinds of ''adult'' music. (The big exception is for the back-catalog jazz reissues, which are far outselling new work.)

Verve -- an important label in jazz since 1956 -- has cut half of its traditional jazz roster in the last year, canceling contracts with respected names like Russell Malone, Kenny Barron and Christian McBride; it is putting its energies into promoting the singers Diana Krall and Natalie Cole. Blue Note, the other well-known strictly jazz imprimatur, has just had its first gold album (with sales of more than 500,000 copies) in nine years: ''Come Away With Me,'' by Norah Jones, who is not a jazz artist but a folk-rock singer. Not surprising, the label is looking for more of her kind and less of Mark Turner's.

Mr. Turner is quiet and self-assured but essentially noncompetitive. (During an interview with him at a Midtown Manhattan restaurant, my tape recorder barely registered his voice; when I suggested that his sound had been studied by some of the saxophonists who regularly played at the New York jazz club Smalls in the mid-90's, he demurred by saying nothing.)

Among younger jazz musicians, he inspires admiration for his approach to practicing and living as much as for his playing. Mr. Turner, a Buddhist, lives in New Haven with his wife, Helena Hansen, a doctoral candidate in anthropology at Yale University, and two children; he enjoys the quiet of a town where there is no jazz scene to speak of.

''I went and practiced with him once,'' said the saxophonist Bill McHenry, who is 29. ''He showed me these music books of things he writes out; just in one book of 36 pages he had tons of different chords and exercises. Because of the purity of his approach, he influences a lot of different people in that way -- either like me, who does freer stuff, or someone else, who does straight-ahead music: it doesn't matter.''

It took some time for Mr. Turner to find his own voice on the instrument. He was born in Ohio, grew up in Cerritos and Palos Verdes, Calif., near Los Angeles, and played saxophone in high school. (He was also a dedicated break-dancer, who broke his front teeth attempting a back flip.) After a brief period studying design and illustration at Long Beach State University, he went to the Berklee College of Music in Boston, in the late 80's, where he quickly became known as a super-studious musician who had explored Coltrane more deeply than anyone around him.

''I was fairly methodical,'' Mr. Turner remembered. ''I almost always wrote out Coltrane's solos, and I'd have a lot of notes on the side.''

Wasn't he afraid of becoming trapped inside Coltrane's voice? ''No,'' he said, sanguinely. ''By doing it, I knew I would eventually not be interested in it anymore. Also, I noticed that if you looked at someone else who was into Trane, and if you could listen through that person's ear and mind, it would be a slightly different version. That's who you are -- it's how you hear.'' After exploring Coltrane, Mr. Turner approached the work of Joe Henderson, Dexter Gordon and Sonny Rollins in the same meticulous way.

By the early 90's, he said, he had exhausted his interest in ''a line of tenor players who do pretty much what most tenor players do today. That is, more of an aggressive sound, with a vocabulary that's come to be a bit programmed.'' When he moved to New York in 1990, he turned to a new figure, who bumped him into a new place: Warne Marsh.

Best known as a fellow-traveler of the pianist Lennie Tristano, Marsh represented the opposite of aggression: he was a linear, melodic improviser who managed to merge spontaneity and research, playing nearly Bach-like melodic lines. As he listened more closely, Mr. Turner found that there was a link between Marsh, Coltrane and Mr. Henderson. And that was Lester Young, the great light-toned saxophonist of the swing era.

Mr.

Turner has appeared on some excellent records -- particularly his own

''In This World'' (Warner Brothers, 1998) and ''Abolish Bad

Architecture'' (Fresh Sound, 1999), an album by the bassist Reid

Anderson on which he played a sideman role. But his best work is clearly

still ahead of him. He says he is done with being the leader of the

Mark Turner Trio or the Mark Turner Quartet: he wants to form a

cooperative band that doesn't bear his name and to share composing and

publishing credit. Part of his reasoning is modesty, but he also

believes he can reach a new and wider audience that way. Some of his

contemporaries believe that his dedication to music may be so pure that

it affects the music's reception. ''His style is so understated in a

way,'' said the saxophonist Donny McCaslin. ''His demeanor is reserved,

and his playing reflects that. He has an introspective sound. Maybe

people aren't seeing what's there.''

Mr. Anderson, the bassist, puts it more precisely. ''He uses harmonies that are his language of harmony; he hears the melody within those harmonies. Sometimes they're complex, and on the surface are almost nonfunctional. But they're of course fully functional. He's dealing on that high level that perhaps only the initiated can appreciate.''

Mark Turner Trio

Village Vanguard,

Seventh Avenue South at 11th Street.

June 27 at 9:30 and 11:30

Turner Times 7

Before Mark Turner was dropped by Warner Brothers, he had made these albums:

DHARMA DAYS: Warner Brothers, 2001

BALLAD SESSION: Warner Brothers, 2000

TWO TENOR BALLADS: Criss Cross, 2000

IN THIS WORLD: Warner Brothers, 1998

MARK TURNER: Warner Brothers, 1998

WARNER JAMS, VOL. 2 -- THE TWO TENORS: (with the saxophonist James Moody) Warner Brothers, 1997

Biography

2013 Long Form

In a career that spans two decades and encompasses a broad array of musical ventures, saxophonist Mark Turner has emerged as a towering presence in the jazz community. With a distinctive, personal tone, singular improvisational skills and an innovative, challenging compositional approach, he has earned a far-reaching reputation as one of jazzs most original and influential musical forces.

2013 finds Turner entering an exciting new creative phase, with his varied talents showcased on a variety of notable new recording projects. Later this year, hell release his sixth album as a leader—his first under his own name in a dozen years. Hes also featured on new or upcoming releases by pianist Stefano Bollani, guitarist Gilad Hekselman, pianist Baptiste Trotignon and the Billy Hart Quartet, of which Turners been a member for nearly a decade and with whom he recorded two previous albums. Hes also continuing his work as a member of spbobet , a collaborative trio with bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard.

Those projects add to an already expansive body of work that encompasses Turners own widely acclaimed albums and an assortment of collaborations, along with his prolific work as an in-demand sideman. Turners diverse discography includes collaborations with many of jazzs leading lights, including Kurt Rosenwinkel, Lee Konitz, James Moody, Dave Holland, Joshua Redman, Delfeayo Marsalis, Brad Mehldau, Reid Anderson, Omer Avital, Diego Barber, David Binney, Brian Blade, Seamus Blake, Chris Cheek, George Colligan, Gary Foster, Jon Gordon, Aaron Goldberg, Ethan Iverson, Jonny King, Ryan Kisor, Guillermo Klein, Matthias Lupri, OAM Trio, Mikkel Ploug, Enrico Rava, Jochen Rueckert, Jaleel Shaw, Edward Simon and the SF Jazz Collective.

Born in 1965 in Ohio and raised in Southern California, Turner grew up surrounded by music of Bola Tangkas Online. There was always a lot of R&B and jazz and soul and gospel going on in the house all the time, he recalls. This was in the early 70s, when the whole integration and civil rights thing had begun to go mainstream, and my mother and stepfather were in the first wave of young black professionals and intellectuals who moved to upper-middle-class white neighborhoods. They and their friends were always going out to see live jazz. I was intrigued by that, and I was intrigued by the whole history of jazz music and African-American culture, as well as the music itself. And my father, who died when I was one and a half, had played saxophone, so maybe I was looking for a connection with him too.

After starting out on clarinet in elementary school, Turner gravitated towards saxophone in high school, while also exploring his talent for the visual arts. Although he briefly studied design and illustration at Long Beach State University, his passion for jazz ultimately led him to pursue a career in music. Turners meticulous, analytical work ethic led him to study and dissect the work of such saxophone giants as John Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins, Warne Marsh and Lester Young in the pursuit his own musical voice.

I really got into it and worked really hard, just trying to figure out who I am, he says, adding, Thats how I am with everything. It took a while, and it was kind of an arduous struggle, but it allowed me to figure out what I wanted from music. Even when I was spending my time sounding like other people, I felt like that was part of my path to sounding like myself. The more you spend time with the form and the language, the more your own personality comes out.

After graduating from Bostons prestigious Berklee College of Music in 1990, Turner moved to New York, where his rapidly developing talents were quickly recognized. Between 1995 and 2001, he recorded five albums of his own—Yam Yam, Mark Turner, In This World, Ballad Session and Dharma Days—while keeping busy as a sought-after collaborator and sideman.

It was around 1992 that I began to notice or feel that what I was doing was uniquely mine, Turner asserts. It had been two and a half years of struggle, but the summer of 1992 was the period where I was finally able to hear it. Maybe no one else would notice, but thats where I could see how things were gonna go.

Despite his growing reputation and influence, Turner intentionally pulled back from working as a leader after 2001s Dharma Days, focusing much of his energy on parenthood while channeling his creativity into numerous collaborative projects.

The last record I made was right when our first child was born, and that had a lot to do with me pulling back from being a leader for awhile, Turner states, explaining, Being a leader is so intense and you really have to put your whole self into it, and I just felt like I wanted to be there for my kids. When youre a leader, youre carrying a lot of weight and responsible for a lot of things that have nothing with music. Being a sideman, you basically just have to worry about being there and doing a good job. But my kids are 10 and 13 now, so its a little less demanding and Ive got more room now to do more things that I feel strongly about.

Of his forthcoming album, a quartet effort with Avishai Cohen on trumpet, Joe Martin on bass and Marcus Gilmore on drums, Turner notes, I spent a lot of time on the compositions, which I usually do. The blowing is important, but I dont think about that when Im writing. I just write the tune, and then we see if we can improvise on it or not. Some of the new tunes are long and kind of involved, and some of them are kind of my version of being pyrotechnical. I just wanted to explore, and I wanted to be able to go in there with a band that would be flexible and have the craftsmanship and the foundation to play something difficult and still make it sound musical.

Despite his long-awaited return to recording as a leader, Turner still values his collaborative work and has no plans to cut back on it.

I would never want to solely be a leader, and if someone handed me the chance to do that, Id say no, he says. I like to interpret other peoples music. I learn from doing that, and its a big part of what Ive become as a musician. In the situations where Im the leader and writing the music, its a combination of everything Ive heard and everything Ive done,. The way that I write and the way that I play and the bands that I bring together are all a representation of all of the musical situations that Ive been in, and Id never want to give that up.

With an impressive musical history already under his belt and more on the way, Mark Turner is clearly on the verge of a creative renaissance. As The New York Times noted, His best work is clearly still ahead of him.

© 2018 Mark Turner Jazz All Rights Reserved

Theme Smartpress by Level9themes.

http://jaleelshaw.blogspot.com/2011/06/mark-turner.html

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

MARK TURNER!

For a while I've been inspired by Marks sense of harmony, range, and control of the horn. But what stands out just as much as all of those qualities is his humility and sense of self control. Upon meeting him, you will find him to be a very cool, quiet person, almost in a meditative state. If you get a chance to sit down and talk to him, you'll find he has lots of information and is just seriously cool. I have a lot of respect for this guy. Nuff said... Here's a recent Q & A between the maestro and I.

Jaleel: I know you were born in California. Can you talk about what it was like growing up in California, how you came to play the saxophone, and who some of your early influences were? Also, how old you were when you started to get serious and realized this is something you wanted to do as a career? Was Berklee your first choice?

Mark: Actually I was born in Ohio, Wright Patterson Air Force Base. My father was a Captain in the air force...his job was navigator in B52 bombers. We later moved with my stepfather(bio father died in plane crash) to L.A. (where I grew up) when I was four. I started playing the clarinet in school band in 4th grade(age 9). There was also a citywide marching band in which I was also involved. I played clarinet until 9th grade when Jazz (big) band was an option so I switched to alto and later tenor (11th/12th grade).

Some early influences were my saxophone teacher Bill McNairn who was strongly inlfuenced by Lester Young, Zoot Sims, Al Cohn. Also My parents had some Sonny Stitt/Gene Ammons records, My Favorite Things, Stardust(John Coltrane) Sonny Rollins(The Bridge), Sonny Side Up(Dizzy Gillespie), some Brecker Bros. Also my parents listened to music a quite a bit - partiularly lots of R&B(Stevie Wonder,Al Green, The Spinners, Earth Wind and Fire, Marvin Gaye, Otis Redding etc). Regarding getting serious, not sure how to answer that as I'm still working on that part.

That said, serious meaning consistant daily practice/ involvment in music...started to take shape first or second year of college then by the third I was "serious" about music. Berklee was my first and only choice as I didn't really know about any other music schools on the east coast. Incidentally, by the way I got to Berklee that was my third year of college. Notion of Music as a career? That was gradual and was never really sure. Just took it a day, month, year at a time while it became a more consistent part of my life.

Jaleel: How was your experience at Berklee College of Music? Who did you study with and what were some of the things you focused on when you were shedding at this time? Also, who else was studying at Berklee at this time?

Mark: My time at Berklee was generally good. When I came I didn't know anything so there was nothing to lose(musically) and everything to gain. I learned from the other students as much as from the teachers. At that time there was Josh Redman(across the Charles river), Seamus Blake, Chris Cheek, Chris Speed(NEC), Antonio Hart(Tony back then), Donny McCaslin, Jordi Rossy, Danilo Perez, Roy Hargrove, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Scott Amendola, Scott Kinsey, Laila Hathaway, Delfeayo Marsalis, Jim Blake, Skooli Svereson, Dan Rieser, Jeff Parker, as well others. Teachers were George Garzone, Joe Viola, Billy Pierce. At that time I was mainly trying to learn the vocabulary(transcribing) and play the saxophone reasonably well(technique/time). Basically learning how to play. I wasn't as interested in originality as in fundamentals. How could I approach making this music mine if I don't really know what it is and or cannot speak its language? I'm still learning it as the process is gradual but at that time it was more fundamental than the present for the most part.

Jaleel: One of the first things I noticed when I first heard you was your control over the horn, your range, and your sense of harmony. What are some things that you practiced regularly? Are these things you are pretty much consistent with today?

Mark: Much of that (harmonic sensibility, horn range) were things that came after Berklee. Although foundation started there. After transcribing a lot I had learned from that process things other than vocabulary such as voice leading/harmony, note groupings, ornamentation, pacing, phrasing, swing/time, sound. Transcribing helped me to learn how to assimilate/integrate information in my own way. So I tried to find ways to combine/continue these things without transcribing. For example play a two five with voice leading( two to six voices all smooth voice leading), see all common tones including all alterations/change of chord color, change cadence with final chord the same, keep cadence change final chord, use note grouping of some type, triads, intervals, use ornamentation etc. Range came out of necessity. There were things I wanted to play that required it. So these are all things that I still work on. Maybe content changes but the format is similar.

Jaleel: Another thing I've noticed about you is that you are a very centered, focused, and humble. On the gigs I've done with you, it sometimes seems like you are meditating before you play. Sometimes doing yoga too. How has this helped you today and do you think it has had an influence on your playing?

Mark: I just try to keep things in perspective and maintain mindfulness on the task at hand. Perspective(what is really important in the relative and absolute, what is one's role/intention in a given situation) helps keep the ego( belief/clinging to an inherently existent I/self. Which includes all things associated with self such as... my body, my mind, my hopes, my fears, my desires, my aversions, my friends, my enemies, my material possessions, me, me, me and on and on etc) in check. Besides, ego is the killer of imagination...drags you down. Have no time for it. Mindfulness/Meditation help to keep the mind clear, focused, pliable. Yoga and running help to keep body/mind reasonably healthy. I'm a slow learner so I need time. Don't want this body to fail too soon.

Jaleel: As both a great saxophonist and composer, who would you say are your biggest influences in music and why?

Mark: Although this not a musical influence I would say at this point my grandfather Lewis Jackson is my greatest influence. Born to a working class family, died an aeronautical engineer, college educator, multimillionaire. If you met him you would never know it. He didn't talk about himself, what he lacked, or what others had. He just did. Keep in mind that he did this during the height of twentieth century segregation, before civil rights laws passed in the sixties. He and my grandmother lived in the same modest home until his death and left almost all of their money to education, the arts, and other charities. He was curious, imaginative, practical, intelligent, action oriented, and generous up to the end of his life. He died as he lived.

John Coltrane. More or less the same reasons as my grandfather but of course applied to music, craft, and culture. I would like to add adventure combined with taste and elegance. power/strength with tenderness and lyricism, blues/folklore with complex harmony/melody. Maintains center no matter what. Sound

Joe Henderson. Master of fast tempos, time, and pacing. Always in the rhythm section, over it on command. In other words he wields/galvanizes the rhythm section...does not simply play his language over it. One of the fathers of quickly moving form(in composition) which we now take for granted. Master of playing different "styles" /bands and giving each what it needs while maintaining his musical integrity/language. Always makes everyone else sound good. Blues/folklore. Maintains slick, cool, swagger no matter what. Sound

Warne Marsh. Master of invention. Rarely repeats himself. Willing to fall/stumble(musically) to find a new melody. Improvises at all costs. Relies primarily on content, placement, anticipation rather than volume/ dynamic range and inflection. Brings an inward contained/concentrated energy rather then an outward spread. Maintains cool no matter what. Sound.

Wayne Shorter. Prolific, varied, composer. Conjurer. Wide imagination. Covers full range of emotion. Sound.

Thelonius Monk. In terms of composition and playing. Great attention to detail. Says a great deal with only what is necessary. Covers full range of emotion. Fully aware. Conjurer. Blues/folklore. Chords. Sound. Use of space.

Lester Young. Melody. Use of space, pacing. Says a lot with little in a short time. Intelligent, witty improviser. Blues/folklore. Sound.

Miles Davis. The power of one note.

Duke Ellington. Prolific composer. Able to take a format and write on it inexhaustibly. Chords.

Morton Feldman, Arnold Shoenberg, Bach, Beethoven. Harmony, Form, Chords, Space

Issac Asimov, Ursula K. LeGuin. Imagination. Ability to created a world/paradigm that lives on it's own terms

John Lennon/Paul McCartney, Stevie Wonder. Great song writers

All musical colleagues.

I could go on and on but need to stop somewhere.

Jaleel: Lately, I'm realizing a lot of the masters have moved out of NYC. And I've been reading some great books that talk about how EVERYONE used to live in NY and how there was a little more networking going on amongst the older and younger musicians back in the day. I'm also seeing a lot of great musicians move out of the city and even the country to pursue their careers. But it's something I'm kind of afraid to do. Do you feel a connection to NYC musically? How important is it for you to be in New York?

Mark: I do feel a connection to NYC musically although I don't feel a necessity to stay here. I did live in New Haven for nine years. There is no other energy like it anywhere else in the jazzworld. It is and has been important to get a taste of it. I would not be what I am (musically) if I had not lived here at some point...at the very least to experience the culture as I believe it is still here(NYC).

Jaleel: You were one of many great jazz artist that were signed to a major label and experienced the collapse of those labels. I still remember running into you at the Vanguard and you telling me that Warner Bros. Jazz was basically no more. How was it to experience something like that first hand and how do you feel about the direction the music scene is going as far as recording goes?

Mark: On many levels it was good experience. If put back in same time period I would do it again but with a different head. Namely I did not realize how much power I/we musicians have. The people I knew at Warner Bros. loved music and worked really hard to keep it going/living. Regarding collapse, everything arises, abides, and falls/ born, lives and dies. So what else is knew? Something is being born/created in terms of recording. More creative freedom. Home made recording. Mobilization from musicians/ community.

Jaleel: What do you work on now when you practice? Do you still transcribe?

Mark: I practice sound mostly. Time in various ways. Vocabulary, technique, Voice leading, Ear training, Mind exercise. I don't transcribe much...little bits here and there from any type of music

SET UP:

Mark Turner plays:

49,000 Selmer Balanced Action Tenor Saxophone

w/ and early Babbit Otto Link #7 mouthpiece & 4 1/2 - 5 Robertos Woodwinds reeds

and

Yamaha 62 Soprano (which I would like to change to a Conn)

w/ a Bill Street mouthpiece (super great) w/ 4 1/2 - 5 Robertos Woodwind Reeds

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/mark-turner-empathy-warmth-and-generosity-mark-turner-by-kurt-rosenwinkel.php

Mark Turner: Grounded in a Spiritual World

by

This article first appeared in issue no 8 of Music & Literature Magazine.

I remember being at Berklee and listening to Mark in the practice room. A lot of people used to gather outside his practice room at various times and just listen to him. He would be in there ten hours a day, usually. And then I heard him in a cafeteria concert—I think he was with Paul LaDuca and Jorge Rossy—and he was playing a lot like John Coltrane. He was really in deep; he was absorbing everything he could from Coltrane at that time.

People's first impression of Mark is usually of a stoic remoteness to the atmosphere around him. It's interesting, because I had that feeling too, but now that I know him so well, I know that that's just a first impression. Once you get to know him and his playing, you feel its empathy, its warmth and generosity. But my first impression was like, "Woah, this guy is deep into this very rarefied area." We didn't really hook up until a couple years later, around 1992, in New York, when I had a trio with Ben Street and Jeff Ballard. At one point we were playing and somebody was like, "You know, Mark's living down the street. We should call him." So we called him and he came over and it was like, boom! That was it. Then it was a quartet. And we just went from there.

We got a weekly gig at Small's jazz club. Over the next excellent seven years, we pretty much only played local gigs, so we had a lot of time on our hands; we weren't really busy like we are now. We would play our Tuesday night gig, and the rest of the time we'd be practicing on our own. I'd be writing a lot of music, and we'd get together two or three times before the next gig and rehearse the new material. We had some other gigs together, too—we had one at the Three of Cups, another club in New York, and in the beginning, we were playing a mix of standards and my music. I remember this one time, I think we were playing "Satellite" by Coltrane, and it was at the end of the song, we were vamping out, and Mark and I started playing together, sort of soloing together, and the four of us hit this zone. It was almost like we blasted out of the atmosphere and found ourselves in this different solar system and everything we did was just magically going together. And I remember, particularly, this one moment that Mark and I had: we played a run together—we were improvising, but we played exactly the same notes, not just one or two but an entire phrase. It was amazing. That was when I think we all realized the potential that we had as a group. I think it encouraged us to work harder and do more. We were always feeling this kind of magic chemistry between us, and we continued to develop over the next ten years.

When we became a quartet, that started feeding into my writing. My writing was developing with the sound of the group, which was developing from the sound of my writing, and also developing from everything that we were listening to together—Keith Jarrett's American Quartet or Duke Ellington or Joe Henderson or Sonny Rollins—all these different touchstones that we all had in common. And then, as we were practicing together, the way that everybody was interacting would start to inform the way I would write. And because Mark and I were developing our own personal styles in the presence of one another, there was a lot of cross-pollination. He would grab something from me and I would grab something from him, and in between songs, we'd be working stuff out. We were developing our own personal language together. His playing definitely informed my playing and my writing, and vice versa.

One of the things that's particular to us is this mind-reading thing where we can play a rubato melody and play every single note exactly together, no matter what or where we put it. And, interestingly, this also goes for written music. I made a record called Heartcore, and it was music that I made in my studio, and I asked Mark to come over and play on something and I didn't really have a chart. All I had was a short-hand scribble that I'd written out for myself that was almost illegible. I gave it to him and was like, this is all I have, and he just read it and just knew what it was. He played incredibly, completely on-target, everything perfect. It happened again on my most recent album, Caipi, which is kind of similar to Heartcore, and I had him come into the studio, and again, it was just a bunch of dots on the staff without any stems or any rhythmic delineations, just a bunch of note heads bunched together. I hadn't bothered to write it out for myself because I knew what the rhythms were, but that was the chart I had for him. It was a mess. And the same thing happened, it was hilarious. He just knew, he just knows! There's a real feeling of closeness there.

One of the most special things about Mark is the absolute egolessness of his involvement with music. He can do anything he wants on the saxophone; his abilities are completely unlimited. But he never has any particular agenda; he's just responding to the music at that moment, and his concern is with shaping the whole performance or song. So that results in a few things: it results in patience, and taste, and maturity, and empathy and graciousness and grace and blending and making and generosity. And then, in those moments where it's needed, because of the same reasons, he might just absolutely tear the roof off. And he can do that because of that natural, stable place from which he's coming. He's always a very grounded presence.

Mark is one of the most dedicated people I've ever met, both musically and in terms of his personal, spiritual journey in this life. He's very methodical. He's very patient. I remember when he almost cut off his hand with the electric saw: everybody was in shock—except for him! And the first time I talked to him after that, he was like, "Yeah, you know, I've had a pretty good run. It's okay." He had already accepted, and was already okay with, the prospect that he'd never play again. To me, that really illustrates where he's grounded. He's not grounded in this world; he's grounded in a deeper—not deeper, but larger—spiritual world. He's able to let go of any worldly things because he knows that his true root and home is in this larger, spiritual, cosmic world.

And another little anecdote about him that's really funny is: Because of where he's coming from, nothing around him really bothers him. And when we started to play internationally in concert halls, I remember many times, we'd be playing and he would take a solo and then I'd be taking a solo and then I would look to cue the melody out —and he wouldn't be there! And I'd turn around and he'd be behind us, on the floor, doing yoga! And I'd look at him and I'd be like raising my eyebrows like, "Here we go! It's coming around!" and he'd give me this look—like a thousand-mile stare. Actually, it was more of a complete, unaffected, no expression, just looking at me like—blank. And it always made me laugh. 'Cause you always knew he would be there—he'd just be nailing it. That was funny, 'cause that happened all the time, he was always doing that. It made me love him a little bit more each time.

Photo credit: Per Kreuger

https://jazztimes.com/features/mark-turner-road-to-recovery/

I remember being at Berklee and listening to Mark in the practice room. A lot of people used to gather outside his practice room at various times and just listen to him. He would be in there ten hours a day, usually. And then I heard him in a cafeteria concert—I think he was with Paul LaDuca and Jorge Rossy—and he was playing a lot like John Coltrane. He was really in deep; he was absorbing everything he could from Coltrane at that time.

People's first impression of Mark is usually of a stoic remoteness to the atmosphere around him. It's interesting, because I had that feeling too, but now that I know him so well, I know that that's just a first impression. Once you get to know him and his playing, you feel its empathy, its warmth and generosity. But my first impression was like, "Woah, this guy is deep into this very rarefied area." We didn't really hook up until a couple years later, around 1992, in New York, when I had a trio with Ben Street and Jeff Ballard. At one point we were playing and somebody was like, "You know, Mark's living down the street. We should call him." So we called him and he came over and it was like, boom! That was it. Then it was a quartet. And we just went from there.

We got a weekly gig at Small's jazz club. Over the next excellent seven years, we pretty much only played local gigs, so we had a lot of time on our hands; we weren't really busy like we are now. We would play our Tuesday night gig, and the rest of the time we'd be practicing on our own. I'd be writing a lot of music, and we'd get together two or three times before the next gig and rehearse the new material. We had some other gigs together, too—we had one at the Three of Cups, another club in New York, and in the beginning, we were playing a mix of standards and my music. I remember this one time, I think we were playing "Satellite" by Coltrane, and it was at the end of the song, we were vamping out, and Mark and I started playing together, sort of soloing together, and the four of us hit this zone. It was almost like we blasted out of the atmosphere and found ourselves in this different solar system and everything we did was just magically going together. And I remember, particularly, this one moment that Mark and I had: we played a run together—we were improvising, but we played exactly the same notes, not just one or two but an entire phrase. It was amazing. That was when I think we all realized the potential that we had as a group. I think it encouraged us to work harder and do more. We were always feeling this kind of magic chemistry between us, and we continued to develop over the next ten years.

When we became a quartet, that started feeding into my writing. My writing was developing with the sound of the group, which was developing from the sound of my writing, and also developing from everything that we were listening to together—Keith Jarrett's American Quartet or Duke Ellington or Joe Henderson or Sonny Rollins—all these different touchstones that we all had in common. And then, as we were practicing together, the way that everybody was interacting would start to inform the way I would write. And because Mark and I were developing our own personal styles in the presence of one another, there was a lot of cross-pollination. He would grab something from me and I would grab something from him, and in between songs, we'd be working stuff out. We were developing our own personal language together. His playing definitely informed my playing and my writing, and vice versa.

One of the things that's particular to us is this mind-reading thing where we can play a rubato melody and play every single note exactly together, no matter what or where we put it. And, interestingly, this also goes for written music. I made a record called Heartcore, and it was music that I made in my studio, and I asked Mark to come over and play on something and I didn't really have a chart. All I had was a short-hand scribble that I'd written out for myself that was almost illegible. I gave it to him and was like, this is all I have, and he just read it and just knew what it was. He played incredibly, completely on-target, everything perfect. It happened again on my most recent album, Caipi, which is kind of similar to Heartcore, and I had him come into the studio, and again, it was just a bunch of dots on the staff without any stems or any rhythmic delineations, just a bunch of note heads bunched together. I hadn't bothered to write it out for myself because I knew what the rhythms were, but that was the chart I had for him. It was a mess. And the same thing happened, it was hilarious. He just knew, he just knows! There's a real feeling of closeness there.

One of the most special things about Mark is the absolute egolessness of his involvement with music. He can do anything he wants on the saxophone; his abilities are completely unlimited. But he never has any particular agenda; he's just responding to the music at that moment, and his concern is with shaping the whole performance or song. So that results in a few things: it results in patience, and taste, and maturity, and empathy and graciousness and grace and blending and making and generosity. And then, in those moments where it's needed, because of the same reasons, he might just absolutely tear the roof off. And he can do that because of that natural, stable place from which he's coming. He's always a very grounded presence.

Mark is one of the most dedicated people I've ever met, both musically and in terms of his personal, spiritual journey in this life. He's very methodical. He's very patient. I remember when he almost cut off his hand with the electric saw: everybody was in shock—except for him! And the first time I talked to him after that, he was like, "Yeah, you know, I've had a pretty good run. It's okay." He had already accepted, and was already okay with, the prospect that he'd never play again. To me, that really illustrates where he's grounded. He's not grounded in this world; he's grounded in a deeper—not deeper, but larger—spiritual world. He's able to let go of any worldly things because he knows that his true root and home is in this larger, spiritual, cosmic world.

And another little anecdote about him that's really funny is: Because of where he's coming from, nothing around him really bothers him. And when we started to play internationally in concert halls, I remember many times, we'd be playing and he would take a solo and then I'd be taking a solo and then I would look to cue the melody out —and he wouldn't be there! And I'd turn around and he'd be behind us, on the floor, doing yoga! And I'd look at him and I'd be like raising my eyebrows like, "Here we go! It's coming around!" and he'd give me this look—like a thousand-mile stare. Actually, it was more of a complete, unaffected, no expression, just looking at me like—blank. And it always made me laugh. 'Cause you always knew he would be there—he'd just be nailing it. That was funny, 'cause that happened all the time, he was always doing that. It made me love him a little bit more each time.

Photo credit: Per Kreuger

https://jazztimes.com/features/mark-turner-road-to-recovery/

Mark Turner: Road to Recovery

In the split second that he saw his left index and middle finger

dangling, tenor saxophonist Mark Turner must’ve thought his very

promising career had ended. “I work in my house with power saws and I

was cutting wood for the fireplace,” he explains. “Sometimes the saw

takes the wood into it … it’s just very powerful. And my hand went with

the wood. The saw cut the tendons and nerves as well. It didn’t actually

hit the bone but it was right there, so it severed them completely.”

The first doctor he saw at the emergency room on Nov. 5 of last year was somewhat dubious about the prospect of Turner regaining the use of his fingers. An orthopedic surgeon had a more optimistic prognosis-six to eight months and he’d be back in the saddle again. “I didn’t touch the sax for two months after the surgery,” says Turner. “For the first month I did physical therapy twice a week, then once a week for the second month. I did some acupuncture, too. And I had to do certain exercises for the first three months, every two hours, all day. After two months I started fingering the sax five minutes every few days and three months after surgery I began practicing maybe two hours every few days.”

By the end of February, less than four months after his surgery, Turner was back on the bandstand, performing at the Village Vanguard in pianist Edward Simon’s quartet. The following month he played a weeklong engagement at Birdland with Italian trumpeter Enrico Rava, pianist Stefano Bollani, bassist Ben Street and drummer Paul Motian, in support of Rava’s new CD, New York Days (ECM). And in early April, Turner joined the members of his freewheeling collective Fly (bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard) for a weeklong engagement at Jazz Standard to celebrate the release of their extraordinary ECM debut, Sky & Country.

During all these gigs, Turner could be seen alternately flexing his fingers and making a fist whenever he wasn’t playing. “I have to keep them going because they get stiff,” he explains. “I have to keep them limber so they work.”

While he appeared to play with the same effortless fluidity, daring intervallic leaps and remarkable command of the altissimo register that have been Turner signatures since his 1998 self-titled debut for Warner Bros., he is not yet back in peak playing form.

The same single-minded determination that allowed Turner to very thoughtfully and methodically forge his own unique vocabulary on the instrument-one that owes more to Warne Marsh and Lennie Tristano than to earlier towering influences John Coltrane and Joe Henderson-has been a key to his comeback. “It’s never going to be all the way back,” he says of his injured left hand. “I’m not going to be able to make a full fist, but I’m definitely on the road to recovery and it gets better and my hand gets stronger every day. My technique is a lot more specific now. I don’t have the leeway that I used to. There are certain things I have to do; otherwise, I can’t play certain passages. So I have to learn how to play flat-fingered. But it’s OK. It makes it even more intense.”

Both Sky & Country and Rava’s New York Days were recorded around the same time last year (February), at the same studio (Avatar in Manhattan), using the same engineer (James Farber). Both ECM projects were, of course, produced by Manfred Eicher, yet they have distinctly different sonic characteristics. The Rava recording utilizes a lot more reverb in the mix than the Fly recording, though Sky & Country is actually a “wetter” mix than Fly’s previous outing, 2004’s self-titled debut on Savoy Jazz. As drummer Ballard notes, “The presence of the drums is really in your face on the new one. If you compare it to our first record it doesn’t sound anything like it at all. There’s a very strong, very robust sound to the whole record. It’s close and you hear detail, but with the reverb it kind of spreads a little bit more than the first record.”

On Ballard’s kinetic “Lady B” and his funk-laden title track, Turner’s evocative “Anandananda” and long-form composition “Super Sister,” or Grenadier’s spacious meditation “CJ” and his swinging “Transfigured,” the freewheeling collective demonstrates uncanny chemistry. Onstage together at Jazz Standard, whether they were running down the elegant and restrained “Fly Mr. Freakjar” or burning their way through John Coltrane’s “Satellite” (a blistering romp based on “How High the Moon”), their approach was intimate and conversational from bar to bar. And their roles shifted easily from tune to tune.

“There’s some pieces where I play just melodies on the drums and then Larry plays more of a function of the rhythmic element,” says Ballard. “And Mark can assume that role of comping, as he did on the gig the other night behind my drum solo on ‘Satellite,’ just offering a bit of a push in there. The moment was calling for that and he answered.”

“On certain tunes, the bass is supplying the more fundamental rhythmic thing and then Jeff is coloring against it,” adds Grenadier. “The focus is always shifting so that the person who is commandeering any particular aspect of the music is always moving around the band.” They’ve had quite a lot of time to develop their musical relationships. “Jeff and I probably first played together in 1982 at a Jamey Aebersold camp,” says Grenadier. “And then Mark and I first played together in 1984 at a California All-State Jazz Band concert at the Monterey Jazz Festival. So we definitely have a long history.”

The first time all three played together was at a 1991 jam session at the West Side loft where Grenadier and Ballard were living. “Larry knew Mark from Berklee,” recalls Ballard, “and so he asked him to come by and play. And it clicked right away.”

The first time the trio recorded together was a track for a 2000 compilation album called Originations, executive produced by Chick Corea to showcase the individual members of his Origin octet. Ballard had been the drummer of Origin since joining in 1997, and for this session (the track “Beat Street”) he recruited Turner and Grenadier and billed it as the Jeff Ballard Trio.

Over the years there have been working situations where two of the three members of Fly might overlap in one band. Ballard and Turner, for instance, played together in Guillermo Klein’s Los Guachos in the late ’90s and later put in several years together in guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel’s band. Says Ballard of Turner, “When I first heard Mark play long ago he was absorbing everything piece by piece, and really not sounding like himself at all. At first he sounded like Trane, then he sounded just like Joe Henderson. And then, suddenly-bam!-he started coming out. He and Kurt developed this great language together and it was really something different.”

Says Turner, “At a certain point I just decided there were certain things I need to do. And it wasn’t so much, ‘I need to find myself.’ I just wanted to have more fun with music and learn how to improvise. I had acquired all this other vocabulary from other people-Trane and Joe Henderson-and it wasn’t fun anymore. So I just went on this search to figure out how can I really learn to truly improvise and I just devised all these different ways to practice. I started to figure out what are the nuts and bolts of music and I came up with some techniques of my own. And eventually it came out to be whatever it is I am now.”

The first doctor he saw at the emergency room on Nov. 5 of last year was somewhat dubious about the prospect of Turner regaining the use of his fingers. An orthopedic surgeon had a more optimistic prognosis-six to eight months and he’d be back in the saddle again. “I didn’t touch the sax for two months after the surgery,” says Turner. “For the first month I did physical therapy twice a week, then once a week for the second month. I did some acupuncture, too. And I had to do certain exercises for the first three months, every two hours, all day. After two months I started fingering the sax five minutes every few days and three months after surgery I began practicing maybe two hours every few days.”

By the end of February, less than four months after his surgery, Turner was back on the bandstand, performing at the Village Vanguard in pianist Edward Simon’s quartet. The following month he played a weeklong engagement at Birdland with Italian trumpeter Enrico Rava, pianist Stefano Bollani, bassist Ben Street and drummer Paul Motian, in support of Rava’s new CD, New York Days (ECM). And in early April, Turner joined the members of his freewheeling collective Fly (bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard) for a weeklong engagement at Jazz Standard to celebrate the release of their extraordinary ECM debut, Sky & Country.

During all these gigs, Turner could be seen alternately flexing his fingers and making a fist whenever he wasn’t playing. “I have to keep them going because they get stiff,” he explains. “I have to keep them limber so they work.”

While he appeared to play with the same effortless fluidity, daring intervallic leaps and remarkable command of the altissimo register that have been Turner signatures since his 1998 self-titled debut for Warner Bros., he is not yet back in peak playing form.

The same single-minded determination that allowed Turner to very thoughtfully and methodically forge his own unique vocabulary on the instrument-one that owes more to Warne Marsh and Lennie Tristano than to earlier towering influences John Coltrane and Joe Henderson-has been a key to his comeback. “It’s never going to be all the way back,” he says of his injured left hand. “I’m not going to be able to make a full fist, but I’m definitely on the road to recovery and it gets better and my hand gets stronger every day. My technique is a lot more specific now. I don’t have the leeway that I used to. There are certain things I have to do; otherwise, I can’t play certain passages. So I have to learn how to play flat-fingered. But it’s OK. It makes it even more intense.”

Both Sky & Country and Rava’s New York Days were recorded around the same time last year (February), at the same studio (Avatar in Manhattan), using the same engineer (James Farber). Both ECM projects were, of course, produced by Manfred Eicher, yet they have distinctly different sonic characteristics. The Rava recording utilizes a lot more reverb in the mix than the Fly recording, though Sky & Country is actually a “wetter” mix than Fly’s previous outing, 2004’s self-titled debut on Savoy Jazz. As drummer Ballard notes, “The presence of the drums is really in your face on the new one. If you compare it to our first record it doesn’t sound anything like it at all. There’s a very strong, very robust sound to the whole record. It’s close and you hear detail, but with the reverb it kind of spreads a little bit more than the first record.”

On Ballard’s kinetic “Lady B” and his funk-laden title track, Turner’s evocative “Anandananda” and long-form composition “Super Sister,” or Grenadier’s spacious meditation “CJ” and his swinging “Transfigured,” the freewheeling collective demonstrates uncanny chemistry. Onstage together at Jazz Standard, whether they were running down the elegant and restrained “Fly Mr. Freakjar” or burning their way through John Coltrane’s “Satellite” (a blistering romp based on “How High the Moon”), their approach was intimate and conversational from bar to bar. And their roles shifted easily from tune to tune.

“There’s some pieces where I play just melodies on the drums and then Larry plays more of a function of the rhythmic element,” says Ballard. “And Mark can assume that role of comping, as he did on the gig the other night behind my drum solo on ‘Satellite,’ just offering a bit of a push in there. The moment was calling for that and he answered.”

“On certain tunes, the bass is supplying the more fundamental rhythmic thing and then Jeff is coloring against it,” adds Grenadier. “The focus is always shifting so that the person who is commandeering any particular aspect of the music is always moving around the band.” They’ve had quite a lot of time to develop their musical relationships. “Jeff and I probably first played together in 1982 at a Jamey Aebersold camp,” says Grenadier. “And then Mark and I first played together in 1984 at a California All-State Jazz Band concert at the Monterey Jazz Festival. So we definitely have a long history.”

The first time all three played together was at a 1991 jam session at the West Side loft where Grenadier and Ballard were living. “Larry knew Mark from Berklee,” recalls Ballard, “and so he asked him to come by and play. And it clicked right away.”

The first time the trio recorded together was a track for a 2000 compilation album called Originations, executive produced by Chick Corea to showcase the individual members of his Origin octet. Ballard had been the drummer of Origin since joining in 1997, and for this session (the track “Beat Street”) he recruited Turner and Grenadier and billed it as the Jeff Ballard Trio.

Over the years there have been working situations where two of the three members of Fly might overlap in one band. Ballard and Turner, for instance, played together in Guillermo Klein’s Los Guachos in the late ’90s and later put in several years together in guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel’s band. Says Ballard of Turner, “When I first heard Mark play long ago he was absorbing everything piece by piece, and really not sounding like himself at all. At first he sounded like Trane, then he sounded just like Joe Henderson. And then, suddenly-bam!-he started coming out. He and Kurt developed this great language together and it was really something different.”

Says Turner, “At a certain point I just decided there were certain things I need to do. And it wasn’t so much, ‘I need to find myself.’ I just wanted to have more fun with music and learn how to improvise. I had acquired all this other vocabulary from other people-Trane and Joe Henderson-and it wasn’t fun anymore. So I just went on this search to figure out how can I really learn to truly improvise and I just devised all these different ways to practice. I started to figure out what are the nuts and bolts of music and I came up with some techniques of my own. And eventually it came out to be whatever it is I am now.”

https://stagebuddy.com/music/music-feature/review-mark-turner-quartet-jazz-standard

September 22, 2014

Review: Mark Turner Quartet at Jazz Standard

Saxophonist Mark Turner and a mysterious band of musical magicians began their run at the Jazz Standard Friday evening, and it is safe to say they managed to surprise and astound a full house of jazz fans.

Decidedly modernist, Turner, his main musical partner-in-crime Avishai Cohen on trumpet, as well as Joe Martin on bass and Justin Brown on drums were intoxicating to listen to and mesmerizing to watch. Amazingly in sync with one another, Turner and Cohen often seemed to merge into a single instrument for a time before occasionally drifting away from one another (Turner literally leaving the performance space and hanging out by the stage door for minutes at a time) to create an evening of music that was quite suspenseful and ultimately satisfying. If these two masters have different styles, I could not detect them.

The utter seriousness with which these artists entered the stage and prepared to play set the tone for the evening. There would be no jokes and almost no speaking to the audience at all in-between the music selections. There were five pieces, all of them quite long and each of them very complex. This was the jazz equivalent of contemporary chamber music. Atonal, sometimes arhythmical, but always impeccably played and gripping. Nothing seemed to have been set in stone and yet nothing was left to chance. The quartet started things off with "It’s Not Alright With Me" and immediately showed the audience some fascinating improvisation from Turner and Cohen, symmetrically placed on stage like two bookends. Justin Brown’s drums were dreamlike and hallucinogenic. "Ethans Line" was dissonant, atonal and through it all Martin’s bass and Brown’s drums created the sound of distant thunder. Cohen’s trumpet sounded like a child that is lost and trying to find its way home. And as in every piece, Tuner joined him to play a nearly identical melody before letting him alone to explore. "Left-Handed Darkness" was my personal favorite, a drunken, dizzy-sounding melodic line that was punctuated by the sharpest bass chords I’ve ever heard. Haunting and melancholy, it was the soulful and occasionally menacing highlight of the evening.

There were remarkable duets, not just between the front-and-center Turner and Cohen but also between Martin and Brown. Martin’s most powerful drum solo came towards the end of the evening. It was a rapid yet velvety-soft tour-de-force. Brown kept the symbol sounding constantly (this seems to be a trademark of his, and it is magical) His playing was so fast it was a blur, yet the sound was soft and exquisite.

In an eclectic schedule of talented performers at the Jazz Standard, it is wonderful to hear exquisite playing in this highly modern style. It is also gratifying to experience such an appreciative crowd.

http://www.westword.com/music/mark-turner-the-world-is-magical-and-theres-no-reason-to-ever-be-bored-6044385

Paolo Soriani

Mark Turner: "The World Is Magical and There's No Reason to Ever Be Bored"

September 26, 2014

Westword

Mark Turner is a dynamic and lucid jazz tenor saxophonist who's been

part of Billy Hart's Quartet for a decade. He's also been a member of

Fly, the collaborative trio with the skilled bassist Larry Grenadier and

drummer Jeff Ballard. But Turner, who will be at Dazzle

on Saturday, September 27, also considers himself a fairly avid science

fiction reader, with Ursula K. Le Guin being one of his favorite

authors, and Turner's brand new ECM album, Lathe of Heaven, borrows its name from her 1971 novel.

The 48-year-old Turner remembers as a kid being impressed by both the PBS adaptation of The Lathe of Heaven and later reading the novel, which is essentially about a man whose dreams alter reality.

"Basically it's about the changing nature of reality," Turner says of the book. "That's it not as solid as we think it is, and that at any point things that could be changing yesterday everyone could have purple and we wouldn't know because some guy dreamed it up and we had no idea what's really go on. It's just that reality is stranger than fiction.

"Even if you have in dreams in your own life, you want to do something to make it real. We are the universe. We make it real every time, every day. Just that. It's pliable. Don't get stuck in your rut, and make things happen. The world is magical and interesting and there's no reason to ever be bored. So that's basically the vibe."

Turner, who practices Buddhism, says the idea of impermanent nature of reality and that it's not as solid as we think it a Buddhist notion, but he adds that the novel itself happens to deal with similar issues. Part of one of the tenants of Buddhism, he says, is that all things are impermanent, and that notion carries over to way he approaches music.

"In terms of writing music and playing music I would say that it's important to remain concentrated to try in the moment and not be worried about the future or the past, not worry about discursive thought when you're trying to improvise," he says. "It's too slow. It's like trying to be in a fight when you're thinking about it or tying your shoes and you think about it. Or not worrying about, for example, if you're improvising getting overly worried about things changing or the fact that maybe you played something you didn't like or writing something and being overly concerned about a past mistake, or a past triumph and getting over it or getting attached to it so much that you can't move forward."

And moving forward is something Turner has been doing professionally for the last two decades and with his earlier five albums as a leader, starting with Yam Yam, his 1995 debut on Criss Cross. While he's has kept active performing with Hart's group and with Fly, Lathe of Heaven is Turner's first album as a leader since 2001's Dharma Days.

"I'm not so into being a leader for leader's sake," he says. "You know, being in the limelight, being in the front and all that. I'm only a leader for basically practical and musical reasons because there are things you get to do as a leader that you wouldn't otherwise get to do, for example, as a sideman. So, part of it is just that I wasn't ready to deal with all of it when I was younger."

Around the time of Dharma Days, Turner and his wife had children, and he was "trying to be a viable, responsible, skillful parent the best I could and trying to be a viable, responsible, skillful saxophone player was pretty much all that I could handle. Trying to be a leader too would basically make me at the very least mediocre of all three. I wanted to try to do at least two things well.

"If I had a huge desire to be leader and I really just wanted to be leading bands no matter what I might have done it anyway but I basically waited until the time was right. My time freed up enough so that would be able to handle being a leader and fulfill my other responsibilities because being a leader you have to do a bunch of other things that have nothing to do with music. You probably spend half your time or more dealing with promoters and all kinds of other stuff. As a side man you basically just deal with music."

Joining Turner on Lathe of Heaven are trumpeter Avishai Cohen, bassist Joe Martin, who Turner has played with in various groups over the last 15 years, and drummer Marcus Gilmore, who Turner says all very detailed players and that they all pay great attention to specifics about the music whatever situation they're in, which is something that's true for most musicians that he like playing with and that he's associated with.

"What these three in particular do in a way that I thought would be appropriate for these songs that I wrote," he says. "They're all complimentary to each other."

That's more than evident both in the live setting and on the stunning and captivating Lathe of Heaven, which features songs inspired by Bad Plus pianist Ethan Iverson, who Turner plays with in Hart's quartet, Stevie Wonder and another science fiction author, Peter F. Hamilton, who's Night's Dawn Trilogy and short-story collection A Second Chance at Eden prompted the title of Turner's song "The Edenist."

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/markturner-sax--tenor

In a career that spans two decades and encompasses a broad array of musical ventures, saxophonist Mark Turner has emerged as a towering presence in the jazz community. With a distinctive, personal tone, singular improvisational skills and an innovative, challenging compositional approach, he’s earned a far-reaching reputation as one of jazz’s most original and influential musical forces.

A New York Times profile of Turner titled “The Best Jazz Player You’ve Never Heard” called him “possibly jazz’s premier player,” noting his reputation amongst his peers and his influential stature in the jazz world.

2013 finds Turner entering an exciting new creative phase, with his varied talents showcased on a variety of notable new recording projects. Later this year, he’ll release his sixth album as a leader—his first under his own name in a dozen years. He’s also featured on new or upcoming releases by pianist Stefano Bollani, guitarist Gilad Hekselman, pianist Baptiste Trotignon and the Billy Hart Quartet, of which Turner’s been a member for nearly a decade and with whom he recorded two previous albums. He’s also continuing his work as a member of Fly, a collaborative trio with bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard.

Those projects add to an already expansive body of work that encompasses Turner’s own widely acclaimed albums and an assortment of collaborations, along with his prolific work as an in-demand sideman. Turner’s diverse discography includes collaborations with many of jazz’s leading lights, including Kurt Rosenwinkel, Lee Konitz, James Moody, Dave Holland, Joshua Redman, Delfeayo Marsalis, Brad Mehldau, Reid Anderson, Omer Avital, Diego Barber, David Binney, Brian Blade, Seamus Blake, Chris Cheek, George Colligan, Gary Foster, Jon Gordon, Aaron Goldberg, Ethan Iverson, Jonny King, Ryan Kisor, Guillermo Klein, Matthias Lupri, OAM Trio, Mikkel Ploug, Enrico Rava, Jochen Rueckert, Jaleel Shaw, Edward Simon and the SF Jazz Collective.

Born in 1965 in Ohio and raised in Southern California, Turner grew up surrounded by music. “There was always a lot of R&B and jazz and soul and gospel going on in the house all the time,” he recalls. “This was in the early ’70s, when the whole integration and civil rights thing had begun to go mainstream, and my mother and stepfather were in the first wave of young black professionals and intellectuals who moved to upper-middle-class white neighborhoods. They and their friends were always going out to see live jazz. I was intrigued by that, and I was intrigued by the whole history of jazz music and African-American culture, as well as the music itself. And my father, who died when I was one and a half, had played saxophone, so maybe I was looking for a connection with him too.”

After starting out on clarinet in elementary school, Turner gravitated towards saxophone in high school, while also exploring his talent for the visual arts. Although he briefly studied design and illustration at Long Beach State University, his passion for jazz ultimately led him to pursue a career in music. Turner’s meticulous, analytical work ethic led him to study and dissect the work of such saxophone giants as John Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins, Warne Marsh and Lester Young in the pursuit his own musical voice.

“I really got into it and worked really hard, just trying to figure out who I am,” he says, adding, “That’s how I am with everything. It took a while, and it was kind of an arduous struggle, but it allowed me to figure out what I wanted from music. Even when I was spending my time sounding like other people, I felt like that was part of my path to sounding like myself. The more you spend time with the form and the language, the more your own personality comes out.”

After graduating from Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music in 1990, Turner moved to New York, where his rapidly developing talents were quickly recognized. Between 1995 and 2001, he recorded five albums of his own—Yam Yam, Mark Turner, In This World, Ballad Session and Dharma Days—while keeping busy as a sought-after collaborator and sideman.

“It was around 1992 that I began to notice or feel that what I was doing was uniquely mine,” Turner asserts. “It had been two and a half years of struggle, but the summer of 1992 was the period where I was finally able to hear it. Maybe no one else would notice, but that’s where I could see how things were gonna go.”

Despite his growing reputation and influence, Turner intentionally pulled back from working as a leader after 2001′s Dharma Days, focusing much of his energy on parenthood while channeling his creativity into numerous collaborative projects.

“The last record I made was right when our first child was born, and that had a lot to do with me pulling back from being a leader for awhile,” Turner states, explaining, “Being a leader is so intense and you really have to put your whole self into it, and I just felt like I wanted to be there for my kids. When you’re a leader, you’re carrying a lot of weight and responsible for a lot of things that have nothing with music. Being a sideman, you basically just have to worry about being there and doing a good job. But my kids are 10 and 13 now, so it’s a little less demanding and I’ve got more room now to do more things that I feel strongly about.”

Of his forthcoming album, a quartet effort with Avishai Cohen on trumpet, Joe Martin on bass and Marcus Gilmore on drums, Turner notes, “I spent a lot of time on the compositions, which I usually do. The blowing is important, but I don’t think about that when I’m writing. I just write the tune, and then we see if we can improvise on it or not. Some of the new tunes are long and kind of involved, and some of them are kind of my version of being pyrotechnical. I just wanted to explore, and I wanted to be able to go in there with a band that would be flexible and have the craftsmanship and the foundation to play something difficult and still make it sound musical.”

Despite his long-awaited return to recording as a leader, Turner still values his collaborative work and has no plans to cut back on it.

“I would never want to solely be a leader, and if someone handed me the chance to do that, I’d say no,” he says. “I like to interpret other people’s music. I learn from doing that, and it’s a big part of what I’ve become as a musician. In the situations where I’m the leader and writing the music, it’s a combination of everything I’ve heard and everything I’ve done,. The way that I write and the way that I play and the bands that I bring together are all a representation of all of the musical situations that I’ve been in, and I’d never want to give that up.”

With an impressive musical history already under his belt and more on the way, Mark Turner is clearly on the verge of a creative renaissance. As The New York Times noted, “His best work is clearly still ahead of him.”

https://jazztimes.com/columns/solo/catching-up-with-saxophonist-mark-turner/ "Basically it's about the changing nature of reality," Turner says of the book. "That's it not as solid as we think it is, and that at any point things that could be changing yesterday everyone could have purple and we wouldn't know because some guy dreamed it up and we had no idea what's really go on. It's just that reality is stranger than fiction.

"Even if you have in dreams in your own life, you want to do something to make it real. We are the universe. We make it real every time, every day. Just that. It's pliable. Don't get stuck in your rut, and make things happen. The world is magical and interesting and there's no reason to ever be bored. So that's basically the vibe."

Turner, who practices Buddhism, says the idea of impermanent nature of reality and that it's not as solid as we think it a Buddhist notion, but he adds that the novel itself happens to deal with similar issues. Part of one of the tenants of Buddhism, he says, is that all things are impermanent, and that notion carries over to way he approaches music.

"In terms of writing music and playing music I would say that it's important to remain concentrated to try in the moment and not be worried about the future or the past, not worry about discursive thought when you're trying to improvise," he says. "It's too slow. It's like trying to be in a fight when you're thinking about it or tying your shoes and you think about it. Or not worrying about, for example, if you're improvising getting overly worried about things changing or the fact that maybe you played something you didn't like or writing something and being overly concerned about a past mistake, or a past triumph and getting over it or getting attached to it so much that you can't move forward."

And moving forward is something Turner has been doing professionally for the last two decades and with his earlier five albums as a leader, starting with Yam Yam, his 1995 debut on Criss Cross. While he's has kept active performing with Hart's group and with Fly, Lathe of Heaven is Turner's first album as a leader since 2001's Dharma Days.

"I'm not so into being a leader for leader's sake," he says. "You know, being in the limelight, being in the front and all that. I'm only a leader for basically practical and musical reasons because there are things you get to do as a leader that you wouldn't otherwise get to do, for example, as a sideman. So, part of it is just that I wasn't ready to deal with all of it when I was younger."