SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2017

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2017

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

EARTH WIND AND FIRE

(May 20-May 26)

JACK DEJOHNETTE

(May 27-June 2)

ALBERT AYLER

(June 3-June 9)

VI REDD

(June 10-June 16)

LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS

(June 17-June 23)

JULIAN “CANNONBALL” ADDERLEY

(June 24-June 30)

JAMES NEWTON

(July 1-July 7)

ART TATUM

(July 8-July 14)

SONNY CLARK

(July 15-July 21)

JASON MORAN

(July 22-July 28)

SONNY STITT

(July 29-August 4)

BUD POWELL

(August 5-August 11)

EARTH WIND AND FIRE

(May 20-May 26)

JACK DEJOHNETTE

(May 27-June 2)

ALBERT AYLER

(June 3-June 9)

VI REDD

(June 10-June 16)

LIGHTNIN’ HOPKINS

(June 17-June 23)

JULIAN “CANNONBALL” ADDERLEY

(June 24-June 30)

JAMES NEWTON

(July 1-July 7)

ART TATUM

(July 8-July 14)

SONNY CLARK

(July 15-July 21)

JASON MORAN

(July 22-July 28)

SONNY STITT

(July 29-August 4)

BUD POWELL

(August 5-August 11)

Monday, July 14, 2014

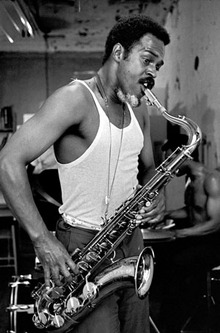

In Memory of Albert Ayler, 1936-1970: Legendary Saxophonist, Composer, and Musical Visionary On His 78th Birthday--A Tribute to His Life And Work

ALBERT AYLER

(b. JULY 13, 1936--d. November 25, 1970)

http://www.newyorker.com/arts/reviews/film/my_name_is_albert_ayler_collin

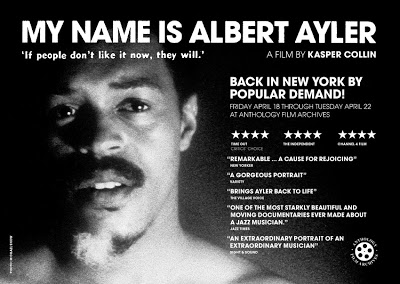

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER

(Director: Kaspar Collin; 2007)

BY RICHARD BRODY

NOVEMBER 12, 2007

THE NEW YORKER

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER

(Director: Kaspar Collin; 2007)

BY RICHARD BRODY

NOVEMBER 12, 2007

THE NEW YORKER

ALBERT AYLER

Kasper

Collin’s documentary portrait of the great saxophonist, who died in

1970, evinces a remarkable sympathy with its subject and his art. Born

in Cleveland, Ayler first made a name for himself in Stockholm in 1962;

Collin, who is Swedish, does terrific legwork to find the musician’s

former girlfriend and sidemen, including one who recalls how the

unheralded outsider dared to compare his importance to Picasso’s. The ne

plus ultra of free jazz, Ayler performed the musical equivalent of

speaking in tongues: he left chord changes and swinging rhythms far

behind and emitted great spiritual wails and shrieks from his horn.

Collin expertly evokes the revolutionary impact of Ayler’s arrival in

New York in 1963, when an astonished John Coltrane yielded the bandstand

to him. (At Coltrane’s request, Ayler played at his funeral, in 1967,

and the film includes an archival recording of that harrowing

performance.) The stirring presence and fascinating anecdotes of such

bandmates as the drummer Sunny Murray, the judicious, evocative use of

archival footage of New York in the mid-sixties, and a generous helping

of the music itself combine to offer magical moments of a madeleine-like

power, summoning up a vanished world that the music both thrived on and

exemplified. Though the end of the film seems rushed—its seventy-nine

minutes could have gone on for hours—it is nonetheless a cause for

rejoicing. In English and Swedish.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/movies/2010/09/ghost-stories.html

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/movies/2010/09/ghost-stories.html

SEPTEMBER 23, 2010

GHOST STORIES

POSTED BY RICHARD BRODY

THE NEW YORKER

The mysterious death, in 1970, of Albert Ayler, the most visionary of jazz musicians—or, rather, the one who, definitively, broke jazz out of the bounds of staffs and scales and chords and bar lines toward the realms of sound and spirit as such—is the subject of a recently-published French book that I’d very much like to read: “Albert Ayler: Témoignages sur un Holy Ghost” (Albert Ayler: Testimony on a Holy Ghost), an oral history by the critic Franck Médioni. The filmed portrait of the musician, “My Name Is Albert Ayler,” by the Swedish director Kasper Collin makes for poignant and exhilarating viewing, and I’m eager to see what Médioni has come up with.

I was pointed in the book’s direction by yesterday’s blog post on Libération’s Web site from Bruno Pfeiffer, their jazz critic. There, he interviews one of Ayler’s great contemporaries, Archie Shepp (who lives in France), who explains that he met Ayler by chance on the streets of Greenwich Village in 1963.

We introduced ourselves. We agreed to meet again soon. You know, I come from the blues, I grew up with my father’s banjo. Free jazz didn’t knock me out, didn’t turn my head. I never thought of myself as a free-jazzman. But I had recently recorded with Cecil Taylor. The pianist had opened me up to new aspects of jazz. Without the doors opened by Cecil, I’d have wondered, when I heard him, what this guy was trying to do. The first time I heard Ayler, at the Jazz Gallery, I thought that the room was exploding in every direction. Nobody had ever heard a saxophonist play with such freedom, take such risks…. I understood that this guy was in the process of replacing one school with another.

Interesting that Shepp—one of the principal free-jazz musicians of the sixties (listen to him on the opening track of the 1966 studio recording “Mama Too Tight,” or “Three for a Quarter, One for a Dime,” from the 1966 recording “Live in San Francisco” or the fierce 1967 recording “Life at the Donaueschingen Music Festival”)—distances himself from it. But, even in the mid-sixties, while Ayler and Taylor were breaking away from the familiar jazz repertory, Shepp brought a bluff Ellingtonian romanticism to some of his recordings (also in evidence on “Mama Too Tight”). It’s also noteworthy that he mentions his father’s banjo—I’ve always thought that there’s something guitar-like in his playing. (I wrote about it several months ago.) Shepp, in recent decades, has been working more squarely within the jazz traditions that predate the musical revolutions of the sixties; it is tragic not to know what Ayler would have gone on to do.

GHOST STORIES

POSTED BY RICHARD BRODY

THE NEW YORKER

The mysterious death, in 1970, of Albert Ayler, the most visionary of jazz musicians—or, rather, the one who, definitively, broke jazz out of the bounds of staffs and scales and chords and bar lines toward the realms of sound and spirit as such—is the subject of a recently-published French book that I’d very much like to read: “Albert Ayler: Témoignages sur un Holy Ghost” (Albert Ayler: Testimony on a Holy Ghost), an oral history by the critic Franck Médioni. The filmed portrait of the musician, “My Name Is Albert Ayler,” by the Swedish director Kasper Collin makes for poignant and exhilarating viewing, and I’m eager to see what Médioni has come up with.

I was pointed in the book’s direction by yesterday’s blog post on Libération’s Web site from Bruno Pfeiffer, their jazz critic. There, he interviews one of Ayler’s great contemporaries, Archie Shepp (who lives in France), who explains that he met Ayler by chance on the streets of Greenwich Village in 1963.

We introduced ourselves. We agreed to meet again soon. You know, I come from the blues, I grew up with my father’s banjo. Free jazz didn’t knock me out, didn’t turn my head. I never thought of myself as a free-jazzman. But I had recently recorded with Cecil Taylor. The pianist had opened me up to new aspects of jazz. Without the doors opened by Cecil, I’d have wondered, when I heard him, what this guy was trying to do. The first time I heard Ayler, at the Jazz Gallery, I thought that the room was exploding in every direction. Nobody had ever heard a saxophonist play with such freedom, take such risks…. I understood that this guy was in the process of replacing one school with another.

Interesting that Shepp—one of the principal free-jazz musicians of the sixties (listen to him on the opening track of the 1966 studio recording “Mama Too Tight,” or “Three for a Quarter, One for a Dime,” from the 1966 recording “Live in San Francisco” or the fierce 1967 recording “Life at the Donaueschingen Music Festival”)—distances himself from it. But, even in the mid-sixties, while Ayler and Taylor were breaking away from the familiar jazz repertory, Shepp brought a bluff Ellingtonian romanticism to some of his recordings (also in evidence on “Mama Too Tight”). It’s also noteworthy that he mentions his father’s banjo—I’ve always thought that there’s something guitar-like in his playing. (I wrote about it several months ago.) Shepp, in recent decades, has been working more squarely within the jazz traditions that predate the musical revolutions of the sixties; it is tragic not to know what Ayler would have gone on to do.

'SPIRITUAL UNITY' (Recorded in 1964; all compositions by Albert Ayler)

"Trane was the Father, Pharoah [Sanders] was the Son, I am the Holy Ghost."

--Albert Ayler

Spiritual Unity is an album by the American jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler, with bassist Gary Peacock and percussionist Sunny Murray. It was recorded for the ESP-Disk label and was a key free jazz recording which brought Ayler to international attention. It features two versions of Ayler's most famous composition, "Ghosts".

ALBERT AYLER: 1936-1970

BY FARUQ Z. BEY

they did not need you, Albert

they did not need and

we could not bear

the awful weight of

your song Albert

of Ancient Dynasties

of occult stellar

communities, of Ausars

insistant transmigration

& cosmic parody they

prefer to stare blank-eyed

into the god-damned maw

of instransigence, we

could not hold nor protect

you, Albert

we who are raw &

debauched would not

suffer for your

brutally olympian sweetness,

the invocation of power

ghosts, your untimely

candor, the burden of your

martyrdom

and so they come

loudspeakers in the nite

with jarring angular

voices comes red mists

& sulphiric yellow rains

so we sweat pus &

languid oils from the east

comes prophets unacquainted

with sin

comes the anti-cristo

comes in halting

arhythmic steps, & we're

to assume them dancers

they come with stones

& equations they claim

to love the brilliant imago

if you are the dali lama

then your light is dispursed

among raggedy-assed

saxophonists under the

evasive streetlights of

tomorrow

As for Me I must forage

PUBLISHED IN:

SOLID GROUND: A New World Journal

Fall 1981

Volume 1 Number 1

Page 39

Editor: Kofi Natambu

Reprinted in Nostalgia For The Present: An Anthology of Writings (From Detroit)

April 1985

Editor: Kofi Natambu

they did not need you, Albert

they did not need and

we could not bear

the awful weight of

your song Albert

of Ancient Dynasties

of occult stellar

communities, of Ausars

insistant transmigration

& cosmic parody they

prefer to stare blank-eyed

into the god-damned maw

of instransigence, we

could not hold nor protect

you, Albert

we who are raw &

debauched would not

suffer for your

brutally olympian sweetness,

the invocation of power

ghosts, your untimely

candor, the burden of your

martyrdom

and so they come

loudspeakers in the nite

with jarring angular

voices comes red mists

& sulphiric yellow rains

so we sweat pus &

languid oils from the east

comes prophets unacquainted

with sin

comes the anti-cristo

comes in halting

arhythmic steps, & we're

to assume them dancers

they come with stones

& equations they claim

to love the brilliant imago

if you are the dali lama

then your light is dispursed

among raggedy-assed

saxophonists under the

evasive streetlights of

tomorrow

As for Me I must forage

PUBLISHED IN:

SOLID GROUND: A New World Journal

Fall 1981

Volume 1 Number 1

Page 39

Editor: Kofi Natambu

Reprinted in Nostalgia For The Present: An Anthology of Writings (From Detroit)

April 1985

Editor: Kofi Natambu

Faruq Z. Bey and the Magic Poetry Band

"Albert Ayler"

(Poem and music by Faruq Z. Bey)

Detroit saxophonist and composer Faruq Z. Bey passed away at the age of 70 on June 2, 2012 after a long fight with emphysema. This song, performed by Faruq as a tribute to legendary sax player Albert Ayler, was featured on the 2007 Magic Poetry Band album "The Kurl of the Butterfly's Tongue”.

“Untitled” International Times (UK), No. 10, March 13-26, 1967, p. 9.

“To Mr. Jones - I Had A Vision” The Cricket (US), 1969, p. 27-30.

Articles about Ayler:

Francois Postif: "Albert Ayler, le Magicien." Jazz Hot (France), No. 213, October, 1965, p. 20-22.

Frank Smith: "His Name is Albert Ayler." Jazz (US), 11 November 1965, p. 11-14.

John Norris: "Three Notes with Albert Ayler." Coda (Canada), April./May 1966, p. 9-11.

Erik Raben: “I Dischi Di Albert Ayler.” Musica Jazz (Italy), August/September 1966, p. 36-39. (Revised version in Orkester Journalen (Sweden) May/June 1967.)

Michel Le Bris: "l'artiste volé par son art." Jazz Hot (France), No. 229, March 1967, p. 16-19.

P. Charles & J. L. Comolli: "Les secrets d'Albert le Grand." Jazz Magazine (France), No. 142, May 1967, p. 34-39.

W. A. Baldwin: “Albert Ayler—Conservative Revolution?” Jazz Monthly (UK), No. 151, September, 1967, p. 15-19, No. 152, October, 1967, p. 15-16, 31, No. 153, November, 1967, p. 9-13, No. 155, January, 1968, p. 10-13, No. 156, February, 1968, p.12-17.

Peter Smids: “A.A.” Gandalf (Netherlands), No. 24, December/January 1967-68.

Martin Schouten: “Albert Ayler En De Tranen Van Stan Laurel” Algemeen Handelsblad (Netherlands) 11 January 1969

Rudy Koopmans: “Albert Ayler: New Grass.” Jazz Wereld (Netherlands), No. 24, June/July 1969, p. 12-18.

Philippe Carles: “La Bataille d’Ayler n’est pas finie.” Jazz Magazine (France), No. 185, January 1971.

John Litweiler: "The Legacy of Albert Ayler." Down Beat (US) 1 April, 1971, p. 14-15, 29.

Ted Joans: "Spiritual Unity—Albert Ayler—Mister AA of Grade Double A Sounds." Coda (Canada), August, 1971,

p. 2-4

Philippe Carles, Patrice Blanc-Francard, Steve Lacy, Yasmina Khassani, Jean-Louis Comolli, Pierre Lattès, Daniel Caux, Delfeil de Ton, Jacques Réda: “Un Soir Autour d’Ayler.” Jazz Magazine (France), No. 192, September 1971, p. 26-31, 48-50.

Alain Tercinet, Chris Flicker & Gerard Noel: “Albert Ayler.” Jazz Hot (France), 1971, p. 22-25.

Han Schulte: “De Schreeuw Van Albert Ayler.” Jazz Nu (Netherlands), November 1980, p. 56-73.

Mike Hames: "The Death of Albert Ayler." The Wire (UK), No. 6, Spring 1984, p. 27-28.

Richard Williams: “Blowing In The Wind.” The Guardian (UK), 24 November 2000.

Jedediah Sklower: “Rebel with the wrong cause. Albert Ayler et la signification du free jazz en France (1959-1971.” Volume! La revue des musiques populaires (France), No. 6 (1&2), 2008, p. 193-219. (offsite)

John Fordham: “50 great moments in jazz: The shortlived cry of Albert Ayler.”The Guardian (UK), 27 September 2010. (offsite)

Albert Ayler - The Truth Is Marching In

By Nat Hentoff

Down Beat

17 November, 1966

USA

IN A RESTAURANT-BAR IN Greenwich Village, tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler was ruminating on the disparity between renown and income. In his case, anyway. Covers of his albums are prominent in the windows of more and more jazz record stores; references to him are increasingly frequent in jazz magazines, here and abroad; a growing number of players are trying to sound like him.

“I’m a new star, according to a magazine in England,” Ayler said, “and I don’t even have fare to England. Record royalties? I never see any. Oh, maybe I'll get $50 this year. One of my albums, Ghosts, won an award in Europe. And the company didn’t even tell me about that. I had to find out another way.”

All

this is said in a soft voice and with a smile but not without

controlled exasperation. Bitterness would be too strong a term for the

Ayler speaking style. He is concerned with inner peace and tries to

avoid letting the economic frustrations of the jazz life corrode him

emotionally. It’s not easy to remain calm, but Ayler so far appears to

be.

In manner, he is reminiscent of John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet—a gentle exterior with a will of steel, a shy laugh, and a constant measuring of who you are and what you want. Ayler’s younger brother, trumpeter Don, is taller, equally serious, and somewhat less given to smiling.

“I

went for a long time without work,” Albert said. “Then George Wein

asked me to come to Europe with a group of other people for 11 days

starting Nov. 3. I hope to be able to add five or six days on my own

after I’m there. Henry Grimes and Sunny Murray will be with Don and me.

But before I heard from Wein, I’d stopped practicing for three weeks. I

was going through a thing. Here I am in Time, in Vogue, in other places.

But no work. My spirits were very low.”

“That’s what they call the testing period,” Don volunteered. “First you get exploited while the music is being examined to see if it has any value. Then when they find there's an ideology behind it, that there’s substance to it, they’ll accept it as a new form.”

“What is its ideology?” I asked.

“To begin with,” Albert answered, “we are the music we play. And our commitment is to peace, to understanding of life. And we keep trying to purify our music, to purify ourselves, so that we can move ourselves—and those who hear us—to higher levels of peace and understanding. You have to purify and crystallize your sound in order to hypnotize. I’m convinced, you see, that through music, life can be given more meaning. And every kind of music has an influence— either direct or indirect—on the world around it so that after a while the sounds of different types of music go around and bring about psychological changes. And we’re trying to bring about peace. In his way, for example, that’s what Coltrane, too, is trying to do.

“To accomplish this, I must have spiritual men playing with me. Since we are the music we play, our way of life has to be clean or else the music can’t be kept pure.”

This meant, he continued, that he couldn’t work with someone addicted to narcotics or who otherwise is emotionally unstable.

“I couldn’t use a man hung up with drugs, because he’d draw from the energy we need to concentrate on the music,” Ayler said. “Fortunately, I’ve never had that problem. I need people who are clear in their minds as well as in their music, people whose thought waves are positive. You must know peace to give peace.”

“You can hear what we’re talking about,” Don emphasized, “in the sound of the musicians we’ve worked with. It’s a pure sound, like crystal.”

“Like Gary Peacock,” Albert said.

“That

is,” he said, smiling thinly, “if you can hear it on the kind of

recordings we make. Except maybe for Ghosts, we have yet to be recorded

right. So far, they’ve just run us into a studio and out again with

never time to get a real balance. That’s the worst way to exploit an

artist. When I hear how well Coltrane is recorded on Impulse, I feel all

the more keenly what is lost of us when we record.”

“We’re

still in the position,” Don added, “of the guy blowing a harp on a

corner years ago, and some record man comes up to him and says, “We’ll

give you something to drink while you play into this tape recorder, and

we’ll see what you can do!”

The

image of the harmonica player on the corner stirred Albert to a

reminiscent smile, and he said, “I used to blow footstool when I was 2.

My mother told me how I’d hold it up to my mouth and blow, as if it were

a horn.”

THE ELDER AYLER brother was born in Cleveland, Ohio, July 13, 1936.

THE ELDER AYLER brother was born in Cleveland, Ohio, July 13, 1936.

“My

father played violin, and he also played tenor somewhat like Dexter

Gordon,” he said. “He played locally and traveled, but he never was

where he wanted to be musically. He thought I might get to where he

wanted to be; so when I was young, he insisted I practice, sometimes

beating me to play when I’d rather be out on the street with the other

kids.

“On

Sundays I’d play duets with him at church. I started on alto, and

gradually I began to work with various rhythm-and- blues combos,

including Little Walter’s. As for training, my father taught me until I

was 10, and from 10 to 18, I studied at the Academy of Music with Benny

Miller, who had played in Cleveland with Bird and Diz and who had also

spent about four years in Africa. My technique grew to the point that in

high school, I always played first chair.”

For three years, Albert was in the Army. “It was at that time,” he said, “that I switched to tenor. It seemed to me that on the tenor you could get out all the feelings of the ghetto. On that horn you can shout and really tell the truth. After all, this music comes from the heart of America, the soul of the ghetto.”

“Do you feel, then, that only black men can play this kind of music?” I asked.

Ayler laughed and said, “There are ghettos everywhere, including in everybody’s head.”

“What this music is,” Don added, “is one individual’s suffering—through his imagination—to find peace.”

“In the Army,” Albert said, returning to autobiography, “we’d have to play concert music six and seven hours a day. But after that, we’d always practice to find new forms. The C.O. in the band would say about my playing during those times, ‘He’s insane. Don’t talk to him. Stay away from him.’ But all the guys—and Lewis Worrell was one of them—were just as interested as I was in getting deeper into ourselves musically.”

Two years of that Army service were spent in France, and in off-base hours, Ayler played at the Blue Note and other Paris clubs. On being discharged in 1961, he stayed in Europe for a time. There were eight months in Sweden during which he traveled through the country in a commercial unit that included a singer.

“I remember one night in Stockholm,” he said, “I started to play what was in my soul. The promoter pulled me off the stage. SO I went to play for little Swedish kids in the subway. They heard my cry. That was in 1962. Two years later I was back with my own group—Don Cherry, Sonny MJurray, Gary Peacock. The promoter woke up. He didn’t pull me off the stage that time.”

By 1963 Ayler was back in the United States. He was heard in New York with Pianist Cecil Taylor, and the word began to spread that whatever was going to happen in the music in the years ahead, Albert Ayler would be an important force. But lack of work at the time sent him back to Cleveland.

“Our parents are very understanding,” he said. “When the economics get to be too much, we’ve always been able to go back home, work out new tunes, and keep the music going.”

In 1964 Albert was back in Europe with bassist Peacock and drummer Murray, picking up trumpeter Cherry who was already there. Their tour included Sweden and Holland. Since then, records Ayler made in Europe and albums he recorded here for ESP have strengthened his reputation and have intensified curiosity about his work. But club and concert work remains exceedingly rare.

DON AYLER, born in Cleveland Oct. 5, 1942, was taught alto saxophone by his father. While studying at the Cleveland Settlement, he switched to trumpet when he was about 13.

“I enjoyed the trumpet more,” Don explained, “because for me, it was possible to deliver a more personal feeling and explore a greater range on that instrument.”

In 1963 the younger Ayler went to Sweden. “I wanted to free my mind from America,” he said, “and I wanted to find my own form—not only in music but in thought and in the way I used my imagination. After four months in Stockholm, I felt my imagination wasn’t being stimulated any more. And I wanted to be a free body, moving. So I went up to the North Pole. I hitchhiked three or four thousand miles to a place called Jokkmockk.”

“With a big pack on his back,” Albert added admiringly.

“In 1964,” Don continued, “I came back home to Cleveland, and for three months, I just stayed in the house, practicing nine and 10 hours a day.”

I asked the brothers about the primary influence on their music.

“Lester

Young,” Albert answered. “The way he connected his phrases. The freedom

with which he flowed. And his warm tone. When he and Billie Holiday got

together, there was so much beauty. These are the kind of people who

produce a spiritual truth beyond this civilization. And Bird, of course.

I met him in 1955 in Cleveland, where they were calling me ‘Little

Bird.’ I saw the spiritual quality in the man. He looked at me, smiled,

and shook my hand. It was a warm feeling. I was impressed by the way

he—and later, Trane—played the changes.

“There was also Sidney Bechet. I was crazy about him. His tone was unbelievable. It helped me a lot to learn that a man could get that kind of tone. It was hypnotizing—the strength of it, the strength of the vibrato. For me, he represented the true spirit, the full force of life, that many of the older musicians had—like in New Orleans jazz—and which many musicians today don’t have. I hope to bring that spirit back into the music we’re playing.”

“The thing about New Orleans jazz,” Don broke in, “is the feeling it communicated that something was about to happen, and it was going to be good.”

“Yes,”

Albert said, “and we’re trying to do for now what people like Louis

Armstrong did at the beginning. Their music was a rejoicing. And it was

beauty that was going to happen. As it was at the beginning, so will it

be at the end.”

As for Don’s influences, they were John Coltrane, Parker, Eric Dolphy, and, later, Clifford Brown and Booker Little.

“Also Freddie Webster,” he emphasized. “One of the best trumpet players there ever was.”

I asked the brothers how they would advise people to listen to their music.

I asked the brothers how they would advise people to listen to their music.

“One

way not to,” Don said, “is to focus on the notes and stuff like that.

Instead, try to move your imagination toward the sound. It’s a matter of

following the sound.”

“You have to relate sound to sound inside the music,” Albert said. “I mean you have to try to listen to everything together.”

“Follow the sound,” Don repeated, “the pitches, the colors. You have to watch them move.”

“This music is good for the mind,” Albert continued. “It frees the mind. If you just listen, you find out more about yourself.”

“It will educate people,” Don said, “to another level of peace.”

“It’s

really free, spiritual music, not just free music,” Albert said. “And

as for playing it, other musicians worry about what they’re playing. But

we’re listening to each other. Many of the others are not playing

together, and so they produce noise. It’s screaming, it’s

neo-avant-garde music. But we are trying to rejuvenate that old New

Orleans feeling that music can be played collectively and with free

form. Each person finds his own form. Like Cecil Taylor has beautiful

form. And listen to Ornette Coleman—rhythmic form.

“When

I say free form, I don’t mean everybody does what he wants to. You have

to listen to each other, you have to improvise collectively.”

“You

have to hear the relationship of a free sound when it happens,” Don

said, “and know it’s right and then know what the next one will be.”

“I’m

using modes now,” Albert said, “because I’m trying to get more form in

the free form. Furthermore, I’d like to play something—like the

beginning of Ghosts—that people can hum. And I want to play songs like I

used to sing when I was real small. Folk melodies that all the people

would understand. I’d use those melodies as a start and have different

simple melodies going in and out of a piece. From simple melody to

complicated textures to simplicity again and then back to the more

dense, the more complex sounds. I’m trying to communicate to as many

people as I can. It’s late now for the world. And if I can help raise

people to new plateaus of peace and understanding, I’ll feel my life has

been worth living as a spiritual artist, that’s what counts.”

“Why,” I asked, “did bop seem too constricting to you?”

“For me,” Albert said, “it was like humming along with Mitch Miller. It was too simple. I’m an artist. I’ve lived more than I can express in bop terms. Why should I hold back the feeling of my life, of being raised in the ghetto of America? It’s a new truth now. And there have to be new ways of expressing that truth. And as I said, I believe music can change people. When bop came, people acted differently than they had before. Our music should be able to remove frustration, to enable people to act more freely, to think more freely.

“For me,” Albert said, “it was like humming along with Mitch Miller. It was too simple. I’m an artist. I’ve lived more than I can express in bop terms. Why should I hold back the feeling of my life, of being raised in the ghetto of America? It’s a new truth now. And there have to be new ways of expressing that truth. And as I said, I believe music can change people. When bop came, people acted differently than they had before. Our music should be able to remove frustration, to enable people to act more freely, to think more freely.

“You

see, everyone is screaming ‘Freedom,’ but mentally, everyone is under a

great strain. But now the truth is marching in, as it once marched back

in New Orleans. And that truth is that there must be peace and joy on

earth. Music really is the universal language, and that’s why it can be

such a force. Words, after all, are only music.”

“Sure,”

Don said. “Music is everybody’s middle name, but people don’t know

this. They don’t know they live by music all the time. Their thoughts

are dancing; their words are music. People don’t realize that they are

continually producing and reacting to sound vibrations. When you’re

connecting—in work, in talk, in thought—you’re making music.”

I still wasn’t clear as to how music could bring peace.

“People talk about love,” Albert explained, “but they don’t believe in each other. They don’t realize they can get strength from each other’s lives. They don’t extend their imaginations. And once a man’s imagination dies, he dies.”

“Everybody,” Don said, “is afraid to find out the ultimate capacities of his imagination.”

“People talk about love,” Albert explained, “but they don’t believe in each other. They don’t realize they can get strength from each other’s lives. They don’t extend their imaginations. And once a man’s imagination dies, he dies.”

“Everybody,” Don said, “is afraid to find out the ultimate capacities of his imagination.”

“And

our music, we think, helps people do just that,” Albert said firmly.

“This music is our imagination put to sound to stimulate other people’s

imaginations. And if we affect somebody, he may in turn affect somebody

else who never heard our music.”

In

an article on the new music by Robert Ostermann in The National

Observer (June 7, 1965), Don Ayler had rejected jazz as a name for their

music because, he said, “Jazz is Jim Crow. It belongs to another era,

another time, another place. We’re playing free music.” But he had also

said that their music was not exclusively an expression of their

personal problems or those of the American black man. “We aren’t selfish

enough to limit it to that,” Don had been quoted in the piece.

I asked him if he still felt that way.

“Yes,” said Don, “people have to get beyond color.”

“Yes,” said Don, “people have to get beyond color.”

“True,”

Albert added, “but I think it’s a very good thing that black people in

this country are becoming conscious of the strengths of being black.

They are beginning to see who they are. They are acquiring so much

respect for themselves. And that’s a beautiful development for me

because I’m playing their suffering, whether they know it or not. I’ve

lived that suffering. Beyond that, it all goes back to God. Nobody’s

superior, and nobody’s inferior. “All we’re guilty of anyway,” said Don,

“is breathing.”

“I’m

encouraged about the music to come,” Albert said. “There are musicians

all over the States who are ready to play free spiritual music. You’ve

got to get ready for the truth, because it’s going to happen. And listen

to Coltrane and Pharaoh Sanders. They’re playing free now. We need all

the help we can get. That Ascension is beautiful! Consider Coltrane.

There’s one of the older guys who was playing bebop but who can feel the

spirit of what’s happening now. He’s trying to reach another peace

level. This is a beautiful person, a highly spiritual brother. Imagine

being able in one lifetime to move from the kind of peace he found in

bebop to a new peace.”

“The most important thing,” Don said, “is to produce your sound and have no psychic frustrations. And that involves

having enough to eat.”

“Yes,”

Albert said. “Music has been a gift to me. All I expect is a chance to

create without worrying about such basics as food.”

“To give peace,” Don said, “you have to have peace.”

http://www.ayler.co.uk/html/bibliography.html

Selected Bibliography of critical/literary texts and musical recordings by and about Albert Ayler in the United States and Europe:

Biography

As Serious As Your Life by Val Wilmer

London: Allison & Busby, 1977, 296 pages.

(current edition - London: Serpent’s Tail, 1999, 304 pages, ISBN 1852427302)

Journalist and photographer, Val Wilmer chronicled the Free Jazz scene as it was happening. Her book, As Serious As Your Life is an acknowledged classic and the chapter on Albert Ayler is the source for much of the Jeff Schwartz biography.

Albert Ayler: His Life and Music by Jeff Schwartz

Unpublished, 1993. Available online.

Jeff Schwartz credits Val WIlmer as the source for much of his own book, however he also draws on a number of other sources to compile an oral history of Albert Ayler. All recording sessions are listed and the author adds his own critical evaluation.

Fiction:

‘Now and Then’ by Leroi Jones

First published in Tales

New York: Grove Press, 1968, 132 pages.

Selected Bibliography of critical/literary texts and musical recordings by and about Albert Ayler in the United States and Europe:

Biography

As Serious As Your Life by Val Wilmer

London: Allison & Busby, 1977, 296 pages.

(current edition - London: Serpent’s Tail, 1999, 304 pages, ISBN 1852427302)

Journalist and photographer, Val Wilmer chronicled the Free Jazz scene as it was happening. Her book, As Serious As Your Life is an acknowledged classic and the chapter on Albert Ayler is the source for much of the Jeff Schwartz biography.

Albert Ayler: His Life and Music by Jeff Schwartz

Unpublished, 1993. Available online.

Jeff Schwartz credits Val WIlmer as the source for much of his own book, however he also draws on a number of other sources to compile an oral history of Albert Ayler. All recording sessions are listed and the author adds his own critical evaluation.

Fiction:

‘Now and Then’ by Leroi Jones

First published in Tales

New York: Grove Press, 1968, 132 pages.

The Fiction of Leroi Jones /Amiri Baraka

Lawrence Hill Books, 2000, 462 pages,

ISBN 155652353X)

‘Now and Then’, a short story by Leroi Jones, begins:

ISBN 155652353X)

‘Now and Then’, a short story by Leroi Jones, begins:

“This musician and his brother always talked about spirits. They were good musicians, talking about spirits, and they had them, the spirits, and soared with them, when they played. The music would climb, and bombard everything, destroying whole civilizations, it seemed.”

The name ‘Ayler’ never appears, but the connection is obvious.

Leroi Jones, later known as Amiri Baraka, was one of the most important writers of his generation. A respected poet, playwright, essayist and political activist, he was heavily involved in the 'free jazz' scene of the 1960s and was responsible for the recording session which resulted in Sonny’s Time Now. The LP was originally released on his own Jihad label and his performance of his poem Black Art with the group gave rise to a great debate (in England at least, in the pages of Jazz Monthly) about whether Albert Ayler’s music was politically motivated, or even, given the extreme imagery of Black Art, racist. Ayler's strange 'essay', ‘To Mr. Jones - I Had a Vision' was published in Baraka's magazine, The Cricket in 1969 and Baraka also recorded an album by Don Ayler for Jihad which has never been released. Baraka's relationship with the Ayler brothers raises a number of questions, none of which are answered in his contribution to the Holy Ghost book (see above). It would have been nice if he'd removed his poet's hat for a while and followed the advice of Joe Friday, but it was not to be.

Spirits Rejoice: Albert Ayler und seine Botschaft

(Spirits Rejoice: Albert Ayler and His Message)

by Peter Niklas Wilson

Hofheim, Germany: Wolke Verlag, 1996, 190 pages

(Spirits Rejoice: Albert Ayler and His Message)

by Peter Niklas Wilson

Hofheim, Germany: Wolke Verlag, 1996, 190 pages

The only published full-length biography of Albert Ayler (unfortunately unavailable in an English translation) was written by Peter Niklas Wilson. Wilson, who sadly died in October 2003, was a German musician, writer, broadcaster and academic who wrote a series of books about jazz musicians, including Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins, Charlie Parker, Anthony Braxton and Albert Ayler. The Ayler book contains an extensive biography, an analysis of Ayler's style and an annotated discography. Wilson met with Edward and Donald Ayler and also interviewed many musicians associated with Albert Ayler, including Sunny Murray, Michel Samson, Milford Graves, Steve Tintweiss, Bobby Few and Gary Peacock.

In June 2013 an Italian translation was published:

Albert Ayler. Lo spirito e la rivolta

Translated and edited by Francesco Martinelli and Antonio Pellicori

Italy: Edizioni ETS, 2013, 274 pages

ISBN: 9788846735720

Albert Ayler Holy Ghost by various

U.S.: Revenant Records, 2004, 208 pages.

Included in the Holy Ghost box set.

Although it cannot be purchased separately and two sections of the book relate directly to the 9 CDs of music in the Holy Ghost box set, there is enough other material to make this qualify as the first ‘proper’ book about Albert Ayler published in the English language. The contents are as follows:

1. ‘Spiritual Unity’ by Val Wilmer

(An updated version of the chapter in As Serious As Your Life)

2. ‘You Think This Is About You?’ by Amiri Baraka

(Amiri Baraka’s memories of Ayler in his own inimitable style)

3. ‘Whence’ by Ben Young

(Ayler’s influences)

4. ‘Albert Ayler in Europe: 1959-62’ by Marc Chaloin

(A meticulously researched essay about Ayler’s first visits to Europe.)

5. ‘Apparitions of Albert the Great in Paris and Saint-Paul-de-Vence’

by Daniel Caux

(Ayler at the Fondation Maeght)

6. ‘Witnesses’ compiled by Ben Young

(Reminiscences of Ayler)

7. ‘Tracks’ by Ben Young

(The sleevenotes to the 9 CDs in the box)

8. ‘Sidemen’ by Ben Young, Tom Greenwood and Matti Konttinen

(Brief biographies of all the other musicians on the CDs)

9. ‘Appendix’

A. ‘Close Encounter with Holy Ghost (and Horn) by Carl Woideck

(A short article about Ayler’s saxophones)

B. ‘Sightings’ by Ben Young and Carlos Kase

(An extensive Ayler sessionography)

Essays, etc.

Albert Ayler, Sunny Murray, Cecil Taylor, Byard Lancaster, Kenneth Terroade : on disc & tape

by Mike Hames

M. Hames, 1983, 63 pages - out of print.

‘Privately printed by the author with the financial assistance of the Arts Council of Great Britain.’

La Marseillaise by Marc-Edouard Nabe

France: La Dilettante, 1989, 38 pages - out of print.

An essay on the French national anthem (no English translation), published in a limited edition (666 copies) on the bicentenary of the French Revolution. According to Paul Jimenes (who first let me know about the book):

“The

author says that the Marseillaise he prefers is that of Ayler, and that

the official french national hymn bothers him. He says why he loves

Ayler. It's not a historical book. I have the impression that Nabe made

variations on a theme, that he tries to write as Ayler played ... and I

reckon that the author reached his aim (we can feel the beginning of the

songs, with Ayler and his brother calling people on a slow rhythm, then

the frantic choruses, we can feel the rage of the drums, and then the

sort of decreasing of the tension...). I think this book is a good

description of Ayler's sound and music.”

(Click image to enlarge.)

Improvisation analysis of selected works of Albert Ayler, Roscoe Mitchell and Cecil Taylor

by Jane Martha Reynolds

PhD thesis (unpublished) University of Wisconsin - Madison, 1993.

David Sanders has provided the following description:

“The main discussion of Albert Ayler in this thesis fills the first chapter, summarized again later in the conclusion. It outlines Ayler’s unconventional improvisation and his composition styles and techniques, including his use of wide vibrato, motivic riffing, overblown notes, and folk themes. The main focus of the chapter is an analysis of Ayler’s improvisation on the version of Ghosts from Prophecy. Reynolds claims that Ayler’s improvisation progressively becomes more and more timbrally based (she means further away from the theme and traditionally sounded notes in general) until tonal references are the only structural device linking his improvisation to the composition.”

Tous les blues d'Albert Ayler by Simon Guibert

E-Dite, France, 2005, 133 pages.

ISBN 2846081638

Based on the radio documentary by Simon Guibert and Yvon Croizier broadcast on France Musique in February 2005.

(Click image to enlarge.)

Improvisation analysis of selected works of Albert Ayler, Roscoe Mitchell and Cecil Taylor

by Jane Martha Reynolds

PhD thesis (unpublished) University of Wisconsin - Madison, 1993.

David Sanders has provided the following description:

“The main discussion of Albert Ayler in this thesis fills the first chapter, summarized again later in the conclusion. It outlines Ayler’s unconventional improvisation and his composition styles and techniques, including his use of wide vibrato, motivic riffing, overblown notes, and folk themes. The main focus of the chapter is an analysis of Ayler’s improvisation on the version of Ghosts from Prophecy. Reynolds claims that Ayler’s improvisation progressively becomes more and more timbrally based (she means further away from the theme and traditionally sounded notes in general) until tonal references are the only structural device linking his improvisation to the composition.”

Tous les blues d'Albert Ayler by Simon Guibert

E-Dite, France, 2005, 133 pages.

ISBN 2846081638

Based on the radio documentary by Simon Guibert and Yvon Croizier broadcast on France Musique in February 2005.

Albert Ayler

Tenor

saxophonist Albert Ayler was born on July 13th 1936 in Cleveland

Heights, Ohio. He learned to play the alto sax at a young age. His

father, Edward, encouraged his musical interests and was his first

teacher. Albert Ayler continued his musical education at John Adams High

School, where he played oboe, and at the local music academy. His first

gig was with Lloyd Pearson and his Counts of Rhythm when has was 15 in

1951. This led to a job with Little Walter Jacobs’ R&B band with

whom he spent the following two summer vacations traveling. After

graduating from high school in 1954 he went to a local college but

financial difficulties forced him to leave college in 1956 and join the

army. He continued to play in the military band and regularly practiced

with other musicians. He spent his last two years of service in France

and then in 1961 he left the army and moved to California for a brief

period before returning to Cleveland.

His

music was moving into the free jazz genre but with his own unique

style. He was not able to find work though in the US and moved to Sweden

in 1962 where he made his first recordings, which were not released

until some years later. Later that year he recorded four albums with Don

Cherry. In December he joined the Cecil Taylor group in Stockholm after

seeing them play at a local venue. He went to Denmark with Taylor and

made his official debut recording, My Name Is Albert Ayler

in January of 1963 with a group of local musicians. He continued to

tour with the Taylor group and returned with them to New York but again

financial difficulties forced him to return to Cleveland where he

received economic support from his parents before moving back to New

York and for a while shared musical ideas with the likes of Ornette

Coleman in impromptu jam sessions. Throughout his life he periodically

depended on financial help initially from his parents and later from his

friend and mentor John Coltrane.

He married Arlene Benton on January 14th, 1964.

The Danish Debut Records label organized the recording of Witches and Devils

in New York around February of 1964. A second set of more traditional

material was also recorded at the same time that was later posthumously

released. In July of 1964 Albert Ayler recorded his masterpiece for the

ESP label with his newly formed trio of Gary Peacock on bass and Sunny

Murray on drums. The LP Spiritual Unity remains a classic 43 years after its recording.

Later on that year a larger group recording that included Don Cherry resulted in the ESP LP New York Eye And Ear Control.

Albert Ayler accepted an invitation from The Cafe Montmartre in

Copenhagen and returned to Europe in the fall of 1964 where together

with his regular trio and Don Cherry her recorded Ghosts.

Don Cherry remained in Europe so Donald Ayler, Albert Ayler’s brother,

replaced him in the group upon their return to New York.

Albert

Ayler started incorporating unusual elements in the music of his new

quartet; making it sound occasionally like a New Orleans marching band.

His notoriety reached its peak when his record Bells

was released on a one-sided, transparent disc in 1965. The mid-sixties

were the pinnacle of both the Free Jazz movement and Albert Ayler’s

popularity. Despite this, however, this genre was never a commercially

viable and popular form of music and despite abundant work Ayler had to

still rely on his parents and John Coltrane for financial support. In

beginning of 1966, he left his wife for Mary Parks.

In

November 1966 he went on a European tour again and on November 15th he

played at the London School of Economics. BBC2 recorded this concert as

part of its “Jazz Goes To College” series, but never broadcast it and

later destroyed it with other tapes.

After

his return from Europe, Ayler landed a recording contract, thanks to

John Coltrane, at Impulse Record. Ayler recorded four sessions for

Impulse. These sessions started off with the Greenwich Village classic

live recordings in December 1966 and February 1967.

John Coltrane died on July 17th 1967.

Shortly after the death of Coltrane, Ayler recorded Love Cry which, although not as raw as his earlier recordings, remained firmly planted in the free jazz genre.

In

the summer of 1968 Ayler fired his brother from the group on the

suggestion of the record label. Donald Ayler was having emotional

problems and was later institutionalized for a while due to a nervous

breakdown.

The last two records for Impulse were an attempt to commercialize his music but they ended up producing the disastrous New Grass and Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe.

Both records were derided by critics and failed as commercial ventures.

In July 1970, after having his contract terminated by Impulse, Albert

played his last concerts in France.

On

November 25, 1970, in Brooklyn, Albert Ayler's body was found floating

in the East River, at the foot of Congress Street Pier.

Albert Ayler : Holy Ghost

by Scott Hreha & Matthew Sumera

November 2004

According to Amiri Baraka, Albert Ayler's favorite rhetorical barb was, "You think it's about you?"—a tactic that at once challenged and disarmed its recipient, especially after Ayler confessed that it wasn't about him either. So who (or what) was it about then? No analysis of Ayler's music will ever trivialize the importance of religion as a primary influence on both his philosophy and compositional/improvisational devices; at certain points in his career, interviews with and published writings by Ayler directly assert that he was little more than a mortal conduit for the voice of God, to an oftentimes troubling extent. But if there is any question as to whether or not it was indeed all about a higher power in the extemporaneous moments in which Ayler so often musically lived, Revenant's new addition to the saxophonist's legacy does little to dispel the myths surrounding Ayler's life. Billed as "the first comprehensive attempt to construct a monument in sound to Albert Ayler", what is perhaps most interesting about the Revenant set is the construction itself. For presumably by now, Ayler's music is strong enough to stand alone.

If the name chosen for the package—a play on Ayler's famous permutation of the Christian trinity that cast Coltrane as the Father, Pharoah Sanders as the Son, and himself as the Holy Ghost—isn't the most obvious tip-off that Ayler's mystique is of principal importance in this (re)telling of the story, then the presentation itself closes the deal. There's good reason why Revenant has won awards for similarly extravagant undertakings; without getting too far into a table of contents, let it suffice to say that this set is no exception to their established standard of both aesthetic and partisan detail. But beyond the gig poster reproductions and 200-page hardbound book, there is a sort of contrived shamanism at work in the pressed dogwood flower and plastic-molded "spirit box" that reflects a materialistic iconography entirely disconnected from the presumed sanctity of Ayler's musical message.

As Ben Ratliff, writing in the New York Times, has already commented, the book's essays are little more than pat retellings of the now mythic Ayler story—a life spent as a misunderstood, precocious, and later anarchistic/visionary artist. Val Wilmer's piece is simply an updated version of her As Serious As Your Life chapter; Amiri Baraka's solipsistic essay is a rehashing of his Black Music-era writings, lacking a bit of the vitriol but also, unfortunately, most of the poetics; and Marc Chaloin's meticulously researched reconstruction of Ayler's post-Army, pre-Spiritual Unity time boasts another handful of primary sources to reinforce the tale. While there is some merit in having these materials compiled, there is little new here and even less that helps clear up the polemics and pseudo-religiosity continuously surrounding Ayler. Project Supervisor Ben Young's annotations, on the other hand, contribute invaluable insight to the existing musicological analysis regarding Ayler and it's appropriate and compelling that his contributions comprise roughly half of the book's content. In many ways, Young is the unsung hero of this entire endeavor.

The audio interviews with Ayler himself—found on discs eight and nine of the set—make up for some of the book's obfuscations by providing glimpses both brief and exhaustive into Ayler's disposition and worldview at different points in his career. The 1964 and 1966 interviews in Copenhagen present flip sides of Ayler's state of mind, practically bookending the period of his most fertile musical development. In 1964, Ayler sounds upbeat and optimistic on the eve of returning to the US, confident that he will reconvene his group with Peacock and Murray and insistent that his music will soon be accepted as a legitimate progression of jazz. 1966 finds him more resigned and vague in tone, wanting to clarify the fact that his music is not about protest but rather a message of peace.

A July 27, 1970 interview with Daniel Caux is conducted with a calmer, more reflective Ayler who largely dwells on autobiography; Val Wilmer's essay in his own words, so to speak. He does add some fuel to the long-debated fire surrounding his "commercial" turn with New Grass and signing with Impulse! Records by stating that producer Bob Thiele "told" him he had to sing. He doesn't seem all that bitter about it, however, rather sounding pleased to finally be able to make significant money as an artist (of course, this being Free Jazz we're talking about, significant is certainly a relative term.) Ayler is revealing through his reticence to a question about the connections between his music and the Black Power/Black Arts movement, distancing himself from Baraka and coolly dismissing Larry Neal's scathing review of New Grass in The Cricket—in light of the man's own words, then, it's interesting that Baraka would be included at all in Holy Ghost, much less as a featured contributor. The box's fundamentally Afrocentric design elements also seem suspect.

The interview with Kiyoshi Koyama, conducted two days earlier in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, is easily the set's most priceless non-musical treasure. More conversational than Q&A in tone, Ayler speaks in depth on some issues very close at hand during that late stage of his life: His settling down with companion Mary Maria in Brooklyn and the growing infrequency of his trips to the East Village, and his allusion to the fact that his brother Donald had been staying in Cleveland to take care of their ailing mother are just two examples of the conversation's loose vibe. The candid setting even lets Ayler reveal a rare sense of artistic conceit, whether implying that Sonny Rollins would be jealous of the strength of Ayler's tenor tone (and presumably, few wouldn't be), or telling an interrupting Allen Blairman that he had better keep the intensity level high at that evening's concert because Ayler was "gonna be vibratin' that plastic ceiling off".

Koyama's interview also provides greater insight into the Impulse! era than has previously been available; as Ben Young outlines in his discussion of the New Grass outtakes, the interviews and the music work in tandem to give a palpable sense of closure to that unresolved aspect of Ayler's career.

As to the music presented, for the Ayler fan it is what one would expect: A series of striking performances (bootleg quality, mostly) ranging from the European days through the early trio with Peacock and Murray (still the most compelling music of his career), to the quartet with Cherry, through to the Michel Sampson era, and ending in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. Notable side-performances include a track with Cecil Taylor (a nice companion to Revenant's masterpiece release of Taylor's Café Monmartre recordings), a rather unfocused reading of "Upper and Lower Egypt" with the Pharoah Sanders Ensemble, and an absolutely paint-peeling Don Ayler Sextet, which turns out to be the real revelation of the entire box, sounding like a cross between a bullfight and a bloody insurrection. As a box set devoted to a central figure of the jazz avant-garde, it is certainly a valuable document to have. As a "monument in sound" to Ayler, it is suspect for both what it presents as well as what it lacks.

On the presentation side, anyone coming to Ayler cold would unfortunately come away with a rather skewed version of the man's music. What one hears throughout the box are performances attended seemingly by three people in the audience, all clapping uncomfortably, and recorded by a gentleman in the back with a microphone hidden in his coat pocket. Hard to make an argument about the centrality of Ayler without evidence to support those statements—and make no mistake, this is a document fundamentally about canon formation. Based upon the evidence that Revenant presents, one might come away with the impression that Ayler was a profoundly powerful saxophonist who was never heard and never recorded. While he certainly was under-heard and under-recorded, Ayler was also well known—enough at least according to Revenant to be "THE catalytic force in defining the sound of the tenor in Free Jazz." (It is this kind of hyperbole that unfortunately undermines the set as a whole.) Compared to Beauty is a Rare Thing, Berlin '88, or the recent Ayler Records set devoted to a similarly overlooked genius, Jimmy Lyons, Holy Ghost somehow feels like it is underselling the man. While all of the essential songs and tunes are here, for better and for worse, Ayler's recorded output is inextricably linked to the solvency of the ESP label. Due to, no doubt, contractual reasons, those items are not in the set and it is consequently why Holy Ghost can never be the definitive Ayler collection.

Luckily, Ayler's other recordings (including those on Impulse!) are available, and the Revenant set helps immeasurably to flesh out the story, as opposed to being the sole documentation. But it is the Revenant argument that remains troubling: "Albert Ayler. Heard ABOUT more than heard. But that's all about to change." This sort of overzealousness cannot help Revenant's (or the Ayler estate's) cause and undoubtedly will not sell any more copies of the set. While they managed to treat Cecil Taylor with understated elegance, there is a sense that Ayler somehow needs to be built up more than necessary. It is an odd feeling that pervades the entire box and ultimately cannot help but mar Holy Ghost. But perhaps it's only fitting that, even 35 years beyond his time on the planet, Albert Ayler's music continues to have to burn through both hype and hysteria, depending upon one's proclivities. It is his sound, after all, that ushers forth from the discs as powerful as ever, regardless of what constructs we might wish to place upon it.

THE FOLLOWING INTERVIEW WITH ALBERT AYLER WAS CONDUCTED BY A JAPANESE JAZZ JOURNALIST FROM THE FAMOUS JAPANESE JAZZ MAGAZINE, SWING JOURNAL.

AYLER

TALKS WARMLY ABOUT HIS LEGENDARY PEERS AND COLLEAGUES SONNY ROLLINS,

ORNETTE COLEMAN, AND JOHN COLTRANE. GENIUS RESPECTS AND HONORS GENIUS:

AUDIO: <iframe width="420" height="315" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/a6RWMHVwKhk" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

This

interview took place on July 25, 1970 just two weeks after Ayler's 34th

birthday and exactly four months before Ayler's mysterious and tragic

death in New York on November 25, 1970. Ayler was found in the East

River and no one knows to this day if he was murdered or committed

suicide. At the time of his death Ayler had been missing for three

weeks.

Documentary Film: My Name

is Albert Ayler:

January 19, 2011

The New Yorker

A quick word to mention that “My Name Is Albert Ayler,” a superb jazz documentary—one not available on DVD—is back, tonight, at 7:30, Maysles Cinema. (The director, Kasper Collin, will be on hand for a Q. & A.) I wrote about it at the time of its release, in 2007. Ayler, who died in 1970, simply took jazz farther than it had ever gone, and, indeed, as far as it could go; suddenly, all other jazz musicians seemed neo-classical (with the possible exception of Cecil Taylor, who played symbiotically with Ayler in 1962)—even if Ayler himself, in his incomparable freedom, embraced traditions, including those of New Orleans, that modern boppers had spurned (such as collective improvisation, wide vibrato, stark melodic simplicity, and lines based more on voice-like inflections than on complex harmonies). John Coltrane, in his last years, strongly reflected his influence, as did Eric Dolphy, in his last studio recording, “Out to Lunch,” from 1964. Collin’s film features interviews with Ayler’s family (including his brother, Donald, who played trumpet in his band) and an astonishing array of clips (including one of Ayler’s shattering performance at Coltrane’s funeral).

My

colleague Sasha Frere-Jones wrote, in 2004, about “Holy

Ghost,” a copious boxed set of Ayler’s work. In 1967, writing from the Newport

Jazz Festival (in an article available to subscribers),

Whitney Balliett described a performance by Ayler’s quintet:

"Most of their efforts were expended on an occasionally funny parody of what sounded like a Salvation Army hymn and of fragments of “There’s No Place Like Home” and “Eeny-Meeny-Miney-Mo.” After a small sampling, the audience began packing up and leaving, causing my companion to observe that “Ayler is really breaking it up.”

So

much for the avant-garde. (In the same review, Balliett wrote of the guitarist

Larry Coryell that he “is the first great hope on his instrument since Charlie

Christian and Django Reinhardt”; had he really never heard Grant Green or Wes

Montgomery? Or did he actually find them hopeless?)

'SPIRITUAL UNITY' (Recorded in 1964; all compositions by Albert

Ayler)

"Trane was the Father, Pharoah [Sanders] was the Son, I am the Holy Ghost."

--Albert Ayler

Spiritual Unity is an album

by the American jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler, with bassist Gary Peacock and

percussionist Sunny Murray.

It was recorded for the ESP-Disk label and was a key free jazz recording which brought Ayler to international attention. It features two versions of Ayler's most famous composition, "Ghosts".

It was recorded for the ESP-Disk label and was a key free jazz recording which brought Ayler to international attention. It features two versions of Ayler's most famous composition, "Ghosts".

Albert Ayler - Lörrach /

Paris 1966 (hatMUSICS)

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER' DOCUMENTARY FILM PROMOTION (2007)

PERSONNEL:

Albert Ayler (tenor sax); Don Ayler (trumpet); Michael Samson

(violin); William Folwell (bass); Beaver Harris (drums)

Recorded

live by South Western Radio Network (SWF-Jazz-Session) in Lörrach, Germany, on

November 7, 1966. Composed

by Albert Ayler:

Movies | Movie Review | 'My Name Is Albert Ayler'

Free-Jazz Pioneer, Aware of His Legacy

My Name Is Albert Ayler

- Directed by Kasper Collin

- Documentary, Music

- 1h 19m

by MATT ZOLLER SEITZ

November 8, 2007

New York Times

The Ohio-born tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler probably would have gotten a kick out of Kasper Collin’s documentary about his life, “My Name Is Albert Ayler,” which opens today at the Anthology Film Archives. Named after one of his albums and built around snippets of audio interviews with Mr. Ayler, it attempts and often achieves a fresh, playful style that’s equally informed by jazz traditions and Mr. Ayler’s urge to shatter them.

Mr. Ayler used marchlike structures as the foundation for multiple, chaotic improvisations by himself and his band mates. The solos on his landmark 1964 album “Spiritual Unity” are musical action paintings in which feeling dictates form.

Mr. Ayler’s sound was formed during a rhythm-and-blues-influenced adolescence, a stint as an Army musician and a two-year sojourn in Northern Europe in the early ’60s that included exposure to the music of the free-jazz innovator Cecil Taylor.

The attention-getting final stretch of Mr. Ayler’s life started in 1963 in New York City (where he barged onstage with his sax during a John Coltrane performance and, to everyone’s astonishment, earned himself a fan and a sometime patron) and ended in 1970, when he went missing for two and a half weeks, then turned up floating in the East River.

From left, Donald and Albert Ayler, both early practitioners of free jazz, in the documentary “My Name Is Albert Ayler.” Credit Larry Fink/Kasper Collin Produktion

In his time Mr. Ayler was marginalized as a grandiose, spaced-out eccentric who played like Charlie Parker trapped under something heavy. As the bassist Gary Peacock, one of many former Ayler band mates interviewed by the director, puts it, people either loved or hated Mr. Ayler’s music: “Nobody said, ‘Ah, he has his good points.’” A straightforward, PBS-style documentary about Mr. Ayler would have seemed clueless. Thankfully, Mr. Collin hasn’t made one.

When you purchase a ticket for an independently reviewed film through our site, we earn an affiliate commission. But our primary goal is that this feature adds value to your reading experience.

The documentary is far from perfect. It compresses Mr. Ayler’s complex, contradictory, Christianity-derived spirituality into New Age hash. It gives short shrift to the women in Mr. Ayler’s life, especially Mary Parks, his final companion and de facto manager, who has been vilified for building a wall between him and the world. (She spoke to Mr. Collin on the phone but refused to appear on camera.) And it waits too long to reveal that Mr. Ayler’s brother and sometime band mate, the trumpeter Donald Ayler, exhibited obsessive and abrasive behavior because he was psychotic. (He died on Oct. 21.)

Luckily the movie’s missteps are eclipsed by its confident and appropriate style. Mr. Collin and his team of editors treat the sparse physical evidence of Mr. Ayler’s life as the filmic equivalent of a melodic through-line in jazz, staging areas from which to mount improvisations: a montage of newsreel footage of bustling Stockholm thoroughfares, circa 1960; blurry, weirdly poetic details from snapshots and home movies; oft-repeated images of the white-bearded Ayler blowing his sax.

The movie starts and ends with shots of Mr. Ayler’s 89-year-old father searching for his son’s gravesite in an Ohio cemetery, and black-and-white film snippets of the saxophonist standing against a blank wall and somewhat furtively looking into the camera, as if daring us to connect with him.

Throughout, Mr. Collin repeats certain quotations as if they were signature riffs recurring in a tune. The most electrifying is a statement from Mr. Ayler, confidently predicting the staying power of his music: “If people don’t like it now, they will.”

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER

Opens today in Manhattan.

Written, produced and directed by Kasper Collin; director of photography, Peter Palm; edited by Eva Hillstrom, Patrick Austen and Mr. Collin. At the Anthology Film Archives, 32 Second Avenue, at Second Street, East Village. Running time: 79 minutes. This film is not rated.

My Name Is Albert Ayler

- Director Kasper Collin

- Writer Kasper Collin

- Stars Albert Ayler, Donald Ayler, Edward Ayler, John Coltrane, Bill Folwell

- Running Time 1h 19m

- Genres Documentary, Music

- Movie data powered by IMDb.com

Last updated: Mar 30, 2016

A

version of this review appears in print on , on Page E10 of the New York

edition with the headline: Free-Jazz Pioneer, Aware of His Legacy. Order Reprints| Today's Paper

http://www.mynameisalbertayler.com/

http://mynameisalbertayler.com/blog/

Recorded Live on September, 1965 at Judson Hall, New York.

Tenor Saxophone – Albert Ayler

http://mynameisalbertayler.com/blog/

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER

News about the documentary film on Albert Ayler

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER AT ALL TOMORROW’S PARTIES

Saturday, December 3, 2011

My Name Is Albert Ayler, the celebrated film by the Swedish filmmaker and producer Kasper Collin, will be screened at the ATP Nightmare Before Christmas festival in December 2011 in Minehead, England. Kasper Collin is invited to introduce the film and to do a Q&A.

My Name Is Albert Ayler has been chosen by Caribou that co-curates the festival with Battles and Les Savy Fav. The festival includes performances by Theo Parrish, Caribou, Kieran Hebden, The Battles, Pharoah Sanders, Sun Ra Arkestra, The Ex with Getatchew Mekurya, Omar Souleyman No Age, The Psychic Paramount, Silver Apples and more.

Filed in News |

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER INSPIRES SWEDISH INDIE POP STAR

Thursday, March 24, 2011

According to P3 Swedish Radio’s Musikguiden Andreas Mattsson wrote his new song “AA” after having watched Kasper Collin’s documentary My Name Is Albert Ayler.

Andreas Mattsson is known from the indie pop group Popsicle.

Filed in News |

ALBERT AYLER FILM AT CALARTS IN LA

Monday, March 21, 2011

The film My Name Is Albert Ayler by Swedish filmmaker and producer Kasper Collin will be screened at California Institute of The Arts on Friday March 25th. The screening is presented by filmmaker Billy Woodberry. Among others Billy has made the film Bless Their Little Hearts. Since 1989 he teaches at CalArts.

On April 5th the Albert Ayler documentary will be screened in Berlin as part of the Musik Film Marathon festival.

Filed in News |

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER IN THE NEW YORKER

Thursday, January 20, 2011

Richard Brody blogs on My Name Is Albert Ayler in The New Yorker today.

Richard’s original review of the film can be read here.

And here is a blog post from September 2010 that we have missed to mention earlier.

Filed in News |

ALBERT AYLER FILM AT MAYSLES CINEMA IN NEW YORK JAN 19TH AND 20TH

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

My Name is Albert Ayler will be screened at Maysles Cinema in Harlem this week. Don’t miss this if you’re in New York!

The movie theater opened by legendary documentary filmmaker Albert Maysles in his Harlem building some years ago.

January 19th and 20th at 7.30pm.

Swedish filmmaker Kasper Collin who for some time has been staying in Harlem will be present for a Q&A on the 20th.

Maysles Cinema, 343 Lenox Avenue, between 127th & 128th, tel: 212 582 6050

Other upcoming screenings are California State University in Chico on February 8 and an encore showing at Cleveland Art Museum on March 16.

Filed in News |

AYLER FILM IN COLOGNE

Monday, August 23, 2010

The Albert Ayler documentary to be screened at Museum Ludwig in Cologne on August 27. Screening starts at 9 pm. The film’s director and producer Kasper Collin will be present to talk about the making of the film after the screening. Read more here.

Filed in News |

“SURELY ONE OF THE GREATEST OF JAZZ DOCUMENTARIES”

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

My Name Is Albert Ayler gets a four out of four stars review in The Buffalo News. The review is written by the papers arts editor Jeff Simon. ”This is a profoundly moving jazz film” he writes. He also calls the film ”surely one of the greatest of jazz documentaries”. The full page review was published on February 13, 2009. The reason was the Swedish produced film’s Buffalo premiere screening at Hallwalls. Read more here.

Filed in News |

AYLER FILM AT WEXNER CENTER FOR THE ARTS

Friday, January 9, 2009

My Name Is Albert Ayler will be screened at Wexner Center for the Arts on January 10. It is screened as one of four films in their series New Documentary. The other three documentaries are Stranded, Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine and Beautiful Losers.

Filed in News |

MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER THIRD BEST FILM OF 2008

Wednesday, January 7, 2009

San Francisco Bay Guardian film critic and writer Max Goldberg put the Swedish feature documentary My Name Is Albert Ayler as number three in his list over the ten best films of 2008. The list was published in SF360, San Francisco Film Society’s and IndieWIRE’S co-publishing venture. This is the complete list (11 films actually…): 1. 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu, Roumania) 2. Flight of the Red Balloon (Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Taiwan/France) 3. My Name is Albert Ayler (Kasper Collin, Sweden) 4. My Winnipeg (Guy Maddin, Canada) 5. The Last Mistress (Catherine Breillat, France/Italy) 6. Let the Right One In (Tomas Alfredson, Sweden) 7. Paranoid Park (Gus Van Sant, France/USA) 8. Still Life (Jia Zhang-ke, China/Hong Kong) 9. Trouble the Water (Carl Deal and Tia Lessin, USA) 10. Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell (Matt Wolf, USA) 11. The Witnesses (André Téchiné, France)

Here are links to Max Goldberg’s reviews of My Name Is Albert Ayler in San Francisco Bay Guardian and Flavourpill.

Filed in News |

AYLER FILM AT MONTEREY JAZZ FESTIVAL AND CALGARY INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL

Tuesday, September 16, 2008

On Sunday September 21 My Name Is Albert Ayler will be screened as part of the legendary Monterey International Jazz Festival. This is the 51st edition of the festival which is said to be the oldest jazz festival in the world. The Swedish filmmaker and producer Kasper Collin will attend the festival and participate in a post screening Q&A session.

On September 28 there will be an Alberta premiere screening at the Calgary International Film Festival. A My Name Is Albert Ayler After Party & the festival awards presentation will take place later that evening. From the festivals website: My Name Is Albert Ayler After Party & Awards Presentation. Informal CIFF Wrap Party & Awards Announcement at Escoba. Admission: VIPs and Albert Ayler patrons

Filed in News |

DJ LEGEND GILLES PETERSON ABOUT MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

We missed to post this before, Gilles Peterson blogs on the film. “I woke up this morning thinking about this film…” Read more

Filed in News |

BACK IN NEW YORK CITY BY POPULAR DEMAND!

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

From Anthology Film Archives website: “Back by popular demand! Anthology heeds the call! Kasper Collin’s invaluable documentary on Albert Ayler was a major success when it had its New York theatrical premiere run here late last year. Now it’s back for five days of encore screenings.”

The New Yorker review by Richard Brody from November last year was published again in their April 16-22 issue. Time Out listed the film as a recommended movie and New York Magazine highlighted it with a picture and review. Richard Brody also wrote about the film in the New Yorker’s Goings On blog on April 17.

His Name Was Albert Ayler

by David Hajdu

July 7, 2011

New Republic

At the risk of straining a flimsy journalistic gimmick, I’m going to use the less-than-momentous occasion of the seventy-fifth anniversary of his birth on July 13 to bring up Albert Ayler, the late saxophonist whose music had something rare in jazz during his short lifetime and rarer still today. Ayler, who died at the age of 34 in 1970, was a musical hellhound, an avant-gardist with Cecil Taylor’s fascination with unheard sounds and Buddy Guy’s blues fire. No one else in jazz has ever sounded like him, though his spirit hovers today over the noise bands on the fringes of rock.

While Ayler was alive, I was still in elementary school and listening to the Monkees. I was in my twenties, living in Greenwich Village, and deep in my first and worst pretentious phase when I discovered Ayler. At the time, I heard the assaults of an anarchist in the volatile intractability of Ayler’s wild improvisations over simple melodies and song forms derived from marching-band music and nursery rhymes. I thought of Ayler as the wildest boy in the schoolyard, which is exactly what hopeless nerds like me fantasized of being.

Over the years, I’ve come to recognize and appreciate the joy, the playfulness in Ayler’s work, and I can understand why he tended to talk about his music in spiritual terms. I hear in Ayler’s music less assault and more exultation—the pleasure screams of an artist allowing himself to do whatever pleases him. Or maybe I’m just projecting self-satisfaction on an artist who ended up abandoning not only music, but life before he reached middle age. Ayler drowned to death, apparently after jumping off the Staten Island Ferry, though the exact circumstances of his death will probably never be determined.

The only known film footage of Ayler performing, a few minutes shot in concerts in Sweden and France late in his life, appears in a fine documentary about him named for an album of his earliest recordings, My Name Is Albert Ayler, which is on DVD but not on YouTube. Still, Ayler’s uniqueness can be heard, if not seen, in dozens of YouTube posts of his songs accompanied by still images, such as this one of Ayler’s best-known composition, “Ghosts.”

http://www.allmusic.com/album/spiritual-unity-mw0000095214

http://www.allmusic.com/album/spiritual-unity-mw0000095214

ALBERT AYLER

ALL MUSIC REVIEW

BY STEVE HUEY