SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2017

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2017

VOLUME THREE NUMBER THREE

HENRY THREADGILL

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

CHRISTIAN MCBRIDE

(December 3-9)

DEXTER GORDON

(December 10-16)

JEANNE LEE

(December 17-23)

CASSANDRA WILSON

(December 24-30)

SAM RIVERS

(December 31-January 6)

TERRY CALLIER

(January 7-13)

ODETTA

(January 14-20)

LESTER BOWIE

(January 21-27)

MACY GRAY

(January 28-February 3)

HAMPTON HAWES

(February 4-10)

GRACHAN MONCUR III

(February 11-17)

LARRY YOUNG

(February 18-24)

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/larry-young-mn0000134393/biography

Larry Young

(1940-1978)

Artist Biography by Alex Henderson

If Jimmy Smith was "the Charlie Parker of the organ," Larry Young was its John Coltrane. One of the great innovators of the mid- to late '60s, Young fashioned a distinctive modal approach to the Hammond B-3 at a time when Smith's earthy, blues-drenched soul-jazz style was the instrument's dominant voice. Initially, Young was very much a Smith admirer himself. After playing with various R&B bands in the 1950s and being featured as a sideman with tenor saxman Jimmy Forrest in 1960, Young debuted as a leader that year with Testifying, which, like his subsequent soul-jazz efforts for Prestige, Young Blues (1960), and Groove Street, (1962), left no doubt that Smith was his primary inspiration. But when Young went to Blue Note in 1964, he was well on his way to becoming a major innovator. Coltrane's post-bop influence asserted itself more and more in Young's playing and composing, and his work grew much more cerebral and exploratory. Unity, recorded in 1965, remains his best-known album. Quick to embrace fusion, Young played with Miles Davis in 1969, John McLaughlin in 1970, and Tony Williams' groundbreaking Lifetime in the early '70s. Unfortunately, his work turned uneven and erratic as the '70s progressed. Young

was only 38 when, in 1978, he checked into the hospital suffering from

stomach pains, and died from untreated pneumonia. The Hammond hero's

work for Blue Note (as both a leader and a sideman) was united for

Mosaic's limited-edition six-CD box set The Complete Blue Note Recordings.

A true innovator on the Hammond B3, Young took a different musical path than any of the other organ masters of his time: Although he started out drawing his major influences from the work of Jimmy Smith and the gospel and blues elements that other players employed, but eventually turned to a more complex, modal approach to the organ with sophisticated harmonic and chordal structure

Larry Young was born

on October 7, 1940, and hails from Newark, New Jersey. His background

includes study of both classical and jazz music on the piano, but had a

natural family bond with the organ. Larry Young, Senior, his father, was

an organist and was the first major musical influence on his son. The

father, moreover, provided an organ in the family home so that Larry

Young, Junior, who had studied piano, could gravitate easily and at his

own pace to the organ. In his teen years, Young was relatively inactive

musically; but a reawakened interest in the organ, encouraged by his

father, propelled Young into music in 1958. After a rhythm and blues

apprenticeship, Young gained wider experience with Lou Donaldson; worked

around New York and New Jersey with Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley and Tommy

Turrentine, among others; and then began heading his own units.

He

recorded his first sides for Prestige in 1960 with the offering

“Testifying,” followed up with “Young Blues,” the same year, then into

“Groove Street,” in ’62. He jumped over to the Blue Note label, and in

’64 put out “Into Somethin.” Young's premier album is thought to be

“Unity”, with Joe Henderson, Woody Shaw, and Elvin Jones, which came out

in 1965. This is considered to be his best outing, and still holds up

as a hard bop organ classic. Young’s work for Blue Note (as both a

leader and a sideman) was compiled for Mosaic's limited-edition six- CD

box set “The Complete Blue Note Recordings.”

Young was attracted

to the novel concept of fusion, he played with Miles Davis in 1969, on

the “Bitches Brew,” sessions, worked with John McLaughlin, and then Tony

Williams' groundbreaking 'Lifetime' in the early '70's, where he was an

important third of that band, one of the first jazz fusion groups. From

here he recorded two solo albums for Arista, “Larry Young's Fuel,”

(1975) and “Spaceball.” (1976)

Larry Young was only 38 when, in

1978, he checked into a hospital suffering from stomach pains, and died

from untreated pneumonia.

He was technically superb, playing pedal

bass, and independent left and right hands, but with a lighter touch

than previous organists, often preferring to solo pianissimo, sometimes

being only slightly audible over the drummer. Young also differed from

his contemporaries in that he loved to play duets with the drummer, who

was invariably his Newark pal, Eddie Gladden.

Young was the sole

major transitional figure responsible for shifting away from the

blues-based style of Jimmy Smith and moving toward a free approach, and

he revolutionized the instrument comprehensively, in composition,

arrangement, and technique.

Source: James Nadal

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/larry-youngs-self-questioning-jazz

Larry Young’s Self-Questioning Jazz

by Richard Brody

March 8, 2016

The New Yorker

A recently discovered collection of sixties-era live recordings shows the jazz organist Larry Young in his prime.Photograph by Gilles Petard / Redferns /Getty

The organ has been a jazz instrument since the nineteen-twenties, when Fats Waller recorded solos at a converted church in

Camden, New Jersey, but it didn’t come to the fore until the

mid-nineteen-fifties, when Jimmy Smith fused his bebop virtuosity with

gospel exhortations. The organists who followed, such as Brother Jack McDuff,

Shirley Scott, and Baby Face Willette, also merged contemporary jazz

with popular rhythm-and-blues traditions. But one organist in

particular, who led his first record date at the age of nineteen, in

1960, pushed the jazz organ headlong into modernity: Larry Young.

Influenced

by John Coltrane, Young made an extraordinary series of recordings from

1964 to 1969, for the Blue Note label, in which his original ideas and

avant-garde tendencies came to the fore. Then he went electric,

recording (uncredited) with Miles Davis on “Bitches Brew,” with the

drummer Tony Williams and the guitarist John McLaughlin in the

hard-edged jazz-rock band Lifetime, with McLaughlin on “Devotion,” and

with McLaughlin and Carlos Santana on “Love Devotion Surrender.” Young

then recorded his own free-jazz-slash-fusion-jam album, “Lawrence of

Newark,” in 1973, followed by some funk-styled albums that weren’t big

hits. He died (officially of pneumonia) at the age of thirty-seven, in

1978. What Young didn’t do, apparently, was leave an accidental trove of

unreleased live recordings from his prime, in the mid-to-late sixties

to early seventies.

Or

so it seemed. The producer Zev Feldman, of Resonance Records, visiting

France’s national audiovisual archives (known as the INA), struck gold,

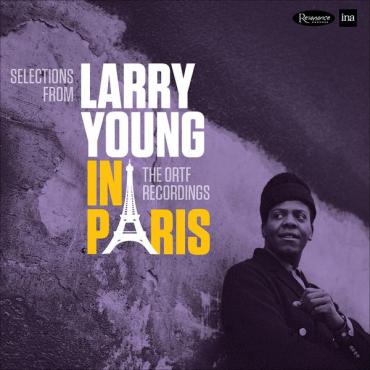

and the treasures he found are now available in a two-CD set, “Larry Young in Paris: The ORTF Recordings,” which offers the double exaltation of sheer serendipity and musical revelation.

The

sessions themselves are a living tale of musical filiation, and it’s

told well in the set’s copious booklet, particularly by Pascal Rozat, of

INA; the saxophonist Nathan Davis; and the trumpeter Woody Shaw’s son

Woody Louis Armstrong Shaw III. The elder Shaw was a prodigy; he

recorded at age eighteen with the mighty jazz modernist Eric Dolphy and

had been about to travel to Europe, in 1964, to join Dolphy’s band when

Dolphy died suddenly, of diabetic shock, at thirty-six. In Paris, Davis

was asked to put together a Dolphy tribute band. (Dolphy had made his

last recordings there with Davis.) Davis invited Shaw; Shaw arrived and

soon wanted to bring over a pair of Newark cohorts to join the band, the

drummer Billy Brooks and Young (Davis and Shaw financed their trip).

The performances of that quartet—Davis, Shaw, Brooks, and Young

(augmented at times by local musicians)—are the core of the newly

discovered tracks in the Resonance set.

All

the performances were recorded in late 1964 and early 1965. The

majority of them were done in a French radio studio for

broadcast—several in a show headed by the pianist Jack Diéval, who

folded Young, Shaw, and Davis into his own regular working band of local

musicians to make an octet for jam sessions that unfortunately didn’t

allow the American guests much solo time. A pair of studio tracks

recorded by the quartet (recording as the Nathan Davis Quartet) give a

hint of Young’s own musical preoccupations, offering the same

instrumentation as Young’s forthcoming quartet on “Unity,” from late

1965 (and his great last Blue Note effort, “Mother Ship,” from 1969),

and Young steals the show. His enthusiastic solo on his own composition

“Luny Tune” picks up the tempo and raises the heat, as he matches his

exotic harmonies with an increasingly free and swirling sense of

rhythmic turbulence over Brooks’s clamorous swing.

As

for those harmonies, Shaw likened them to the ones that McCoy Tyner

employed as the pianist in John Coltrane’s quartet. (I’d add that Young,

with his angular sense of off-balance phrasing, his impulsive

accelerations, and the colors of his voicings, adds an additional

dimension of dissonance and mystery.) But, in the booklet, John Koenig

offers a remarkable sidebar regarding Young’s piano teacher in New

Jersey, Olga Von Till, a native of Hungary who, in her own youth, had

studied with Béla Bartók and “had been exposed to two other important

Hungarian composers, Ernő Dohnányi and Zoltán Kodály”—and who also the

taught the pianist Bill Evans.

The

zenith of the Resonance set is two tracks from the quartet’s live

performance from February 9, 1965, at the Paris jazz club La Locomotive,

where they stretch out on a pair of compositions—“Black Nile,” by Wayne

Shorter, from his vastly influential album “Night Dreamer,” and Shaw’s

“Zoltan” (as in Kodály)—and the young lions mightily roar. There, Shaw

displays a thrilling tension between complexity and fury, his intricate

solo lines yielding to hectically intense high-energy blasts and

shrieks. On “Zoltan,” Young takes a heroically long but not

self-indulgent solo that builds, with a relentless intricacy, to a

terrific noise that highlights another facet of his artistry—a sure

dramatic sense.

Between

Young’s own solo and Shaw’s joyful musical exclamations during Davis’s

performance, the live recording of “Zoltan” displays the hot core of

Young’s big musical idea. One of the distinguishing traits of the prime

modern jazz musicians, whether Coltrane or Coleman, Miles Davis or Cecil

Taylor, is that their musical ideas aren’t limited to their solos and

their compositions. They think in terms of a group, they have a unique

idea for the sound of a group. Their groups aren’t just collections of

soloists; they create not just an original sound for themselves but an

original quasi-orchestral sound. In forming a band, they renovate the

very notion of a band itself.

Young

is one of them, and his idea is rooted in the nature of his instrument,

the organ. (He played piano, too, on a few recordings; a piano track in

the Resonance set, “Larry’s Blues,” sounds like a near-parody, loving

and joyful, of the style of Thelonious Monk, whose composition “Monk’s

Dream” he would play, as a duet with the drummer Elvin Jones, on the

album “Unity.”)* Speaking of his own band after he brought in the

electric guitarist James (Blood) Ulmer, Ornette Coleman (quoted in John

Litweiler’s superb biography) said that he then recognized “that the

guitar had a very wide overtone, so maybe one guitar might sound like

ten violins as far as range of strength. You know, like in a symphony

orchestra two trumpets are equivalent to twenty-four violins.” Young’s

Hammond organ is an electric instrument, too, and, as he formed his

bands, he built them on the massing of sound, adding horn players and

percussionists to create a density that wasn’t like that of a big band,

based on sheer numbers of massed voices, but that instead let each go

their own way, in a sort of planned cacophony that made noises of their

melodies and gave the organ a tangle of sound to challenge it, as on the

albums “Of Love and Peace,” “Contrasts,” and, above all, the great, Sun Ra-inspired exultation of “Lawrence of Newark.”

Yet

it seems, in retrospect, only natural that Young, revelling in the

plugged-in power of his instrument, would make the turn to electric

music overall and fight it out in great musical wrangles with such

guitarists as Jimi Hendrix and John McLaughlin. (Jack Bruce, of “Cream,”

played with Lifetime as well; his adulation of Young’s musicianship is

cited in the set’s booklet.) Young also put his art of noise in the

nation’s service—he had the distinction of having one of his concerts

personally interrupted by Richard Nixon. In June, 1972, Young was

performing in Washington, D.C.’s Lafayette Square, just across from the

White House, with the electronic-music innovators Joe Gallivan and the

mononymic Nicholas in the trio Love Cry Want. Reportedly,

President Nixon ordered an aide, J. R. Haldeman, to “pull the plug on

the concert fearing that this strange music would ‘levitate the White

House.’ ”

Young, for all his

musical boldness of vision, played with a decided introversion. He

played fast and at times he played loud, but he favored slightly

muffled, softened registrations on the organ with the result that, even

when he played very fast and complicated music, his performances had the

feeling of a murmur, of musical asides spoken to himself—of an interior

monologue overheard. There’s a meditative self-consciousness, a

sense—and perhaps this, even more than any technical or harmonic device,

marks his heritage from Coltrane—of a struggle within, an effort at

self-questioning and self-overcoming. That spiritual dimension,

contending with the assertive striving of progressive musical thought

and the early-flowering energies of youth itself, is proudly and

sublimely on display in the new set from Resonance.

*An earlier version of this article misstated the year of Young’s recording of “Monk’s Dream.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

On Unity, jazz organist Larry Young began to display some of the angular drive that made him a natural for the jazz-rock explosion to come barely four years later. While about as far from the groove jazz of Jimmy Smith as you could get, Young hadn't made the complete leap into freeform jazz-rock either. Here he finds himself in very distinguished company: drummer Elvin Jones, trumpeter Woody Shaw, and saxman Joe Henderson. Young was clearly taken by the explorations of saxophonists Coleman and Coltrane, as well as the tonal expressionism put in place by Sonny Rollins and the hard-edged modal music of Miles Davis and his young quintet. But the sound here is all Young: the rhythmic thrusting pulses shoved up against Henderson and Shaw as the framework for a melody that never actually emerges ("Zoltan" -- one of three Shaw tunes here), the skipping chords he uses to supplant the harmony in "Monk's Dream," and also the reiterating of front-line phrases a half step behind the beat to create an echo effect and leave a tonal trace on the soloists as they emerge into the tunes (Henderson's "If" and Shaw's "The Moontrane"). All of these are Young trademarks, displayed when he was still very young, yet enough of a wiseacre to try to drive a group of musicians as seasoned as this -- and he succeeded each and every time. As a soloist, Young is at his best on Shaw's "Beyond All Limits" and the classic nugget "Softly as in a Morning Sunrise." In his breaks, Young uses the middle register as a place of departure, staggering arpeggios against chords against harmonic inversions that swing plenty and still comes out at all angles. Unity proved that Young's debut, Into Somethin', was no fluke, and that he could play with the lions. And as an album, it holds up even better than some of the work by his sidemen here.

http://hardbop.tripod.com/lyoung.html

LARRY YOUNG

October 7, 1940-March 30, 1978

"His technique is out of sight; he has very big ears and a beautiful time conception. Larry Young is where jazz is going on the organ!"

--Woody Shaw

"One thing about Larry Young:" Grant Green was emphasizing as he talked about this album, "is that he's really an organist. He knows that instrument; and furthermore, unlike some other organ players in jazz, Larry never gets in your way. On the contrary, he keeps building in and around what you're doing while always listening so that his comping is always a great help. He's much more flexible than organists usually are, and that makes it possible for him to comp specifically for each different player. Man, he even comps in a particular way for drums.

"Another thing:" Green continued, "is that Larry is always identifiable right away. You know it's him. It's his sound, his imagination and the way he creates melodic lines. His sense of melody is very fresh and very much his own."

The organ skills of Larry Young, furthermore, are, in a sense, a continuation of a family tradition. As Leonard Feather points out in his notes for Talkin' About, a Grant Green album on which Larry Young and Elvin Jones also appear, "Larry is the first important young jazz organist to claim second-generation status in this profession." Larry Young, Senior, is an organist and was the first major musical influence on his son. The father, moreover, provided an organ in the family home so that Larry Young, Junior, who had studied piano, could gravitate easily and at his own pace to the organ.

The younger Larry Young was born on October 7, 1940. His background includes study of both classical and jazz music. (Bud Powell was a particular force in Young's early indoctrination into modern jazz.) From about 1951 to 1958, Young was relatively inactive musically; but a strongly reawakened interest in the organ, encouraged by his father, propelled Young back into music in 1958. After a rhythm and blues apprenticeship, Young gained wider experience with Lou Donaldson; worked around New York and New Jersey with Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley and Tommy Turrentine, among others; and then began heading his own units.

Young went to Paris in November, 1964, and has since created a European following through his quartet at Le Chat Qui Peche. One reason for his decision to spend some time in Europe is Young's persistent concern with widening his experience so that he can express a greater diversity of emotions and insights in his music. But Young has no intention of becoming an expatriate. With regard to jazz, he points out, "the States are the basis of it all and I won't stay in Europe so long that I'll lose my roots."

The strength of Young's roots in the blues and in corollary foundation blocks of the jazz language are evident throughout this album. Also clear is Young's variegated imagination as a composer. In Larry Young, Blue Note has one of the more rare contemporary phenomena in jazz--thoroughly skilled jazz organist who recognizes the virtues of clarity and spareness as well as the need to keep attuned to the individual, expressive needs and directions of his colleagues.

--NAT HENTOFF, from the liner notes,

Into Somethin', Blue Note.

A selected discography of Larry Young albums:

- Testifying, 1960, Prestige.

- Young Blues, 1960, Prestige.

- Groove Street, 1962, Prestige.

- Into Somethin', 1964, Blue Note.

- Unity, 1965, Blue Note.

- Contrasts, 1967, Blue Note.

Larry Young - In Paris: The ORTF Recordings

Release Date: 3/11/16

Available now as Deluxe 2-CD and Limited Edition 2-LP Sets Digital Download - Available on iTunes now Mastered for iTunes version includes a complete digital booklet |

- First release of all previously unreleased Larry Young recordings in nearly 40 years.

- Featuring the iconic jazz organist Larry Young with Woody Shaw (trumpet), Nathan Davis (saxophone), Billy Brooks (drums) & others.

- Endorsed by the estate of Larry Young.

- Extensive liner notes with essays and interviews by John McLaughlin, Dr. Lonnie Smith, John Medeski, Bill Laswell, Nathan Davis, Andre Francis, producer Zev Feldman, Larry Young III & Woody Shaw III.

- Includes rare and previously unreleased photos from the Francis Wolff, Jean-Pierre Leloir and INA archives.

- Tracks include an over 20-minute version of “Zoltan,” “Beyond All Limits” from the classic Unity album, as well as other mid-1960’s songs including “Talkin’ About J.C.” and “Luny Tune.”

- Released in partnership with the National Audiovisual Institute (INA) of France.

Deluxe Limited Edition 2-LP Set

- Limited Edition pressing of 2,000

- 180 gram vinyl pressed on 12” LPs at 33-1/3 RPM by Record Technology Incorporated (R.T.I.)

- Gatefold LP includes booklet with essays, unpublished photos, collector postcards and digital download card

- Mastered by the legendary engineer Bernie Grundman

Resonance Records, in partnership with the

National Audiovisual Institute (INA) of France, is pleased to

announce the release of Larry Young In Paris/The ORTF Recordings. Featuring

groundbreaking performances by the ingenious organist and pianist,

these studio and live recordings from 1964 and 1965 made for

French radio and never before issued on record, will be released on

March 11, 2016 in deluxe two-CD and limited-edition two-LP sets.

Producer Zev Feldman notes,

"It's particularly exciting because none of this music has ever

been heard before except on its initial broadcast in France five

decades ago. I think that's something to celebrate and a call for

us all — as we often do with the archival recordings we at

Resonance Records uncover — to revisit and discuss this

legendary artist's legacy."

Musicians featured on these

recordings include trumpet legend Woody Shaw, tenor saxophonist and bandleader Nathan Davis and drummer Billy Brooks. An international cast of supporting players — pianist Jack Diéval, tenor saxophonist Jean-Claude Fohrenbach and bassist Jacques B. Hess; Italian drummer Franco Manzecchi, Jamaican trumpet player Sonny Grey and Guadaloupean

percussionist Jacky

Bamboo

— round out the personnel. This album marks the first new release

of Larry

Young music

in 38 years.

This project came about in

2012 when Feldman traveled to France to explore the ORTF (Office

of French Radio and Television) archives (the media vaults

overseen by the French National Audiovisual Institute (INA) in the

hope of finding undiscovered treasures, which he suspected he

might find there. Feldman asked INA executives about specific

artists and was stunned to learn that the vaults contained

recordings documenting some of the greatest American jazz

musicians who lived in — or visited — Paris in the 1960s,

including Larry Young. Resonance Records presents in this album

tapes that had been sitting idly in the vaults for nearly 50

years, scrupulously maintained by INA.

Resonance will release other

projects from the INA vaults; details to come soon. Feldman

states, "It's been a thrill of a lifetime working with Christiane

Lemire, Laure Audinot and Pascal Rozat at INA France

to find this great music and shepherd this release. No question

about it, this project represents jazz through diplomacy and the

greater good of a mission. These recordings showcase American

artists who found their home and voice in Europe at a time when

the American landscape wasn't always as supportive." Feldman

continues, "When we started to explore the vaults of the ORTF and

search for recordings to release, we had a wish list of various

artists we were on the hunt for, but Larry was the one artist whom

I personally felt we needed to look extra hard for. I couldn't be

more thrilled with what we found and which we are now releasing. I

hope we'll all revisit this genius's legacy and appreciate why he

mattered so much."

These recordings tell the

story of a brief but critically important period when Young lived

in Paris in the 1960s. The 19-year-old Woody Shaw was supposed to

have joined saxophone/flute/bass clarinet legend Eric Dolphy in

Dolphy's group in Paris, which was to have been the house band at

the legendary Parisian jazz club Le Chat Qui Pêche. Unfortunately,

Dolphy died unexpectedly shortly before Shaw was to have arrived.

The venue's owner, Madame Ricard, and Dolphy's fiancée, Joyce

Mordecai, asked Nathan Davis, who was the club's de facto music

director, to put together a band to honor Dolphy and to provide

the musical anchor for the club. Dolphy had extolled the young

Shaw's virtues to Davis, and so Woody was invited to come to Paris

and join Davis's ensemble. After being in Paris for a few weeks,

Woody felt homesick and prevailed upon Davis and Madame Ricard to

bring his Newark colleagues Larry Young and Billy Brooks, to join

him and Davis in the Nathan Davis Quartet, which became Le Chat

Qui Pêche's house band. For several months, Young immersed himself

in the flourishing Parisian jazz scene, which had attracted many

American jazz players who were able to find steady work playing

nightly gigs with both with their American comrades and

international artists who had been drawn to the scene. Many

American musicians found the atmosphere a welcome escape from

economic and social tensions back home. In the '60s, Parisian jazz

clubs were filled with legends such as Dolphy, Kenny Clarke,

Dexter Gordon, Slide Hampton and Bud Powell.

While in France, Young

recorded at the ORTF Studios in Paris (now Maison de Radio

France) as a sideman with the Nathan Davis Quartet, the Jazz aux

Champs-Élysées All-Stars and with his own piano trio, which

included bassist Jacques B. Hess drummer and Franco Manzecchi. Larry Young In Paris/The ORTF Recordings includes selections from the original tapes, which were

made specifically for broadcast on French radio. As noted, the

only time these recordings have been shared with the public were

in their original airings on two iconic monthly radio programs: Musique aux

Champs-Élysées, hosted by Jack Diéval; and Jazz sur scène, hosted by producer and jazz scholar André Francis.

Shortly after the tapes were made, Larry Young returned to New York to record

the classic album Unity, his second album for Blue Note as a leader.

Resonance Records has

packaged the two-CD version of this album with a 68-page book of

essays by Feldman, legendary guitarist John McLaughlin, associate

producer/ jazz scholar/INA executive Pascal Rozat, associate

producers John Koenig, Larry Young III and Woody Shaw III; and

illuminating interviews with Davis (conducted by executive

producer Michael Cuscuna), organists Dr. Lonnie Smith and John

Medeski (of Medeski, Martin & Wood), bassist/producer Bill

Laswell and French broadcasting legend André Francis. The historic

package also contains many rare, previously unpublished images

from the archives of INA and photographers Francis Wolff and

Jean-Pierre Leloir. The limited edition 12" two-LP set contains

all of the same material as contained in the CD set in an elegant

insert, with collector postcards and a digital download card. The

LPs are pressed on 180-gram vinyl at 33-1/3 rpm by Record

Technology Incorporated (R.T.I.), mastered by the legendary

engineer Bernie Grundman. The packages for both sets represent

further brilliant creations by art director Burton Yount in a

series of beautiful packages he's done for Resonance Records, this

time assisted by art director Gordon H. Jee.

Larry Young was only 23 and 24 years old when these

recordings were made. He would soon be known as one of the great

organ players of his time, and indeed, all time. The son of a

professional organist, he played piano and organ from early

childhood. Indeed, his first serious piano teacher, after his

father, had been a student of Bartók and Dohnanyi at the Franz

Liszt Academy in Budapest. The influence of this teacher, Olga Von

Till, might explain Young's penchant for harmonic structures based

on fourths and his use of pentatonic scales — both characteristic

of the strains of Hungarian folk music found in the music of

Bartok, Dohnanyi and their compatriot, Kodaly; structures that

were unusual in jazz at the time. The only truly notable musician

of Young's era who applied these musical elements to his artistry

was modern jazz piano icon McCoy Tyner. Although Young grew up

playing R&B and jazz in and around Newark, his colleagues

always saw him as pushing the boundaries while still respecting

the solid jazz traditions of those who came before. Woody Shaw's

son, Woody Louis Armstrong Shaw III, writes that the compositions

on this album break through the barriers of jazz standards, "all

of them bearing idiosyncrasies of a burgeoning style, a new way of

speaking to the tradition of jazz, while pushing the limits of the

music to new heights."

Young's musical journey swept him into fusion music,

joining Miles Davis in 1969 for Bitches Brew (Columbia); the same year Young, Tony Williams and John

McLaughlin formed the seminal fusion group the Tony Williams

Lifetime (which later added Jack Bruce, who had risen to fame as

the co-founder, singer and bassist for the British power trio

Cream). Young's popularity in the jazz world expanded to other

musical genres, from R&B to rock (he would record with Jimi

Hendrix and Carlos Santana). His son, Larry Young III, writes in

his essay for the album book, "In the decades since his death,

more and more people have discovered the magnitude of his

contribution to all of the genres of music in which he was a

creative and trailblazing force. My father truly lit a fire, which

is still burning, although he has been gone for almost four

decades. His music is still relevant and fresh."

Tracks include an

over-20-minute version of "Zoltan" (dedicated to the Hungarian

nationalist composer Zoltan Kodály), "Beyond All Limits" (which

can also be heard on the Blue Note album Unity), other mid-'60s compositions by Young (including

"Talkin' About J.C.," "Luny Tune" and the impromptu "Larry's

Blues"), and much more.

Feldman notes, "Larry Young

might be one of the great all-time unsung heroes in this music.

This is very personal for me and I want to awaken a new generation

of fans. Young's contemporary, Jimmy Smith, was a pioneer who took

the Hammond organ out of the church, but Larry Young took the

organ out of this world! I hope this project will allow us the

opportunity to go back and celebrate this artist's unheralded

legacy."

Larry Young died at the

tragically young age of 38 in 1978. Larry Young In

Paris: The ORTF Recordings is a tribute to his memory and endorsed by the estate of

Larry Young. It was produced Zev Feldman with executive producers

George Klabin and Michael Cuscuna, with sound restoration by Fran

Gala and Klabin

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/into-something-larry-young-blue-note-records-review-by-greg-simmons.php

by GREG SIMMONS

January 5, 2013

Larry Young: Into Something.

Blue Note records.1965

Organist Larry Young's Into Something is full of relaxed grooves, great melodies and strong performances from tenor saxophonist Sam Rivers and 1960s stalwarts Elvin Jones (drums) and Grant Green (guitar). Originally released in 1964, this record has been remastered and released on 45 RPM vinyl by Ron Rambach at Music Matters.

Soul Jazz? Groove Jazz? Whatever. It's good jazz and that's what matters. On the opening "Tyrone," Young plays deep blues at a straightforward, un-showy pace that gets enhanced and expanded, first by Green and then by Rivers who takes his saxophone the furthest out. Rivers, still a relatively new player here, hasn't reached the creative heights he'd hit in just a few years, but the pieces are clearly forming and his performance noteworthy.

Green's "Plaza De Toros" adds a little Latin rhythm to the date and provides the guitarist an opportunity for an extended workout. Like much of Young's playing on the date, he says more with less, eschewing flame-thrower licks to stay close to the rhythmic core of the song. Rivers plays with unusual attention to the melody, even as he clearly shows the greatest willingness to play hard. The consummate Jones taps out what, on the surface, sounds like a pretty tame backbeat. But careful listening reveals that he's actually doing three things at once: tapping the basic rhythm on the ride; adding a polyrhythmic round fill on the toms; and then throwing sharp fills into the short breaks. This isn't a thunderous drum performance. It's much subtler than that, but it's fully up to the standards expected from one of the era's premier drummers .

"Paris Eyes" is a funky, happy melody that provides Rivers with the first workout. He plays it loose, with a fair amount of breath through his horn, but flows along comfortably within the organ groove. It's too bad he doesn't get more time on the microphone, stepping off for Green to take his turn just when he's getting hot. But, then, there's that old saying: always leave them wanting more.

The Music Matters pressings are all about wringing the most sonic information from the original master tapes. The series has been wildly successful at presenting these old Blue Note titles with better fidelity to the master tapes than they've ever exhibited before. Into Something upholds the series' standards nicely, with dead quiet vinyl and exemplary sound quality. A Hammond B3 has rarely sounded this smooth.

Into Something digs a little deeper into the Blue Note catalog, but it's a good thing that Rambach went this far. This is a great, classic, mellow groove record that's worth hearing in the best possible light.

Track Listing: Tyrone; Plaza de Toros; Paris Eyes; Backup; Ritha.

Personnel: Larry Young: Hammond B3 organ; Grant Green: guitar; Sam Rivers: tenor saxophone; Elvin Jones: drums.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/jan/21/larry-young-in-paris-the-ortf-recordings-review-elegant-reckless-beauty-on-unearthed-60s-live-tapes

Larry Young: In Paris – The ORTF Recordings review – reckless beauty on unearthed live tapes

4 / 5 stars

(Resonance)

Breathtaking improvisations … Larry Young, on keys, with his trio. Photograph: Jean Pierre Leloir

The

hellfire-preacher mannerisms that stars like Jimmy Smith popularised

have often dominated the Hammond organ’s personality in jazz – but not

for 1960s/70s Hammond organist Larry Young. Young died at 38, leaving a few

great Blue Note sessions, work on Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew,

and some raw fusion with the Tony Williams Lifetime. These newly

unearthed 1964-65 recordings recently turned up in broadcaster ORTF’s

archives, featuring the then Paris-resident’s radio shows with American

and French musicians, fascinatingly including little-known Stan Getzian

sax maestro Jean-Claude Fohrenbach. Trumpeter Woody Shaw’s blistering,

high-register playing and Nathan Davis’s nonchalant tenor-sax ruggedness

mingle with a series of breathtaking Young improvisations – twisting

and quirky on Trane of Thought, sleek and then petrifyingly fierce on

Wayne Shorter’s Black Nile, percussively wayward on regular piano on the

Monk-like Larry’s Blues. The dominant style is earthy,

early-Coltraneish hard-bop, and there are long processions of solos –

but Young’s elegantly reckless improvisations lift this music into

another league.

https://web.musicaficionado.com/main.html#!/article/How_Larry_Young_Changed_The_Shape_Of_Jazz

How Larry Young Changed The Shape Of Jazz

August 1, 2016

by Chris Morris

Music Aficionado

Larry Young. Courtesy of Getty Images

Very few musicians, in any genre, can be said to have changed the fundamental approach to their instrument. In jazz, Larry Young did it significantly. He essentially re-thought the use of the Hammond B3 organ, taking the bulky, sonically versatile keyboard out of the soul-jazz wilderness into bold new terrain.

What's more, Young—also known as Khalid Yasin after his embrace of the Sunni Muslim faith in the '60s—revolutionized the B3 not once, but twice. In 1965, he began to work the freewheeling attack of avant-gardeists like his friend and inspiration John Coltrane into his hard-swinging music. In 1969, he became a key player in the burgeoning fusion scene, and found a truly distinctive voice as a member of the first freestanding fusion power trio, the Tony Williams Lifetime.

Beloved by the jazz cognoscenti and usually ahead of the curve musically, Young remains something of an obscure figure today, and also a frustrating one. His career was marked by an unusual series of advances, retreats, and retrenchments, and had more or less petered out by the time of his premature death at 37 in 1978. Yet he managed to cover an incredible amount of ground in his 17-year recording career.

You could say that Young was born to play the organ: His father Larry Young, Sr. played it professionally, and ran a club in his hometown of Newark, NJ, the Shindig, where the instrument was a permanent fixture on the bandstand. Though he studied piano at an early age—and would embrace the askew harmonics of Thelonious Monk in his own work—he didn't embrace the organ until his teens, after a stint as a singer in the local R&B unit the Challengers.

However, though a relatively late bloomer on the difficult instrument, Young had attained enough facility on the organ that, in his late teens, he found work as a sideman with the soulful saxophonist Lou Donaldson. In 1960, Prestige Records came a-calling, and he cut his first record date as a leader, 'Testifying', at the prodigious age of 19 in August of that year.

As the album's title suggests, Young was immediately cast as a pretender to the throne of the reigning soul-jazz organ grinder, Jimmy Smith. From his discovery in 1956, the prolific Smith had cranked out a series of funky, blues-based LPs—20 by the end of 1959!—for Blue Note Records, Prestige's principal competitor among indie jazz labels of the day. By the turn of the decade, Bob Weinstock's Prestige was looking for its own Smith; the year Young debuted also marked the label bow of another gutbucket B3 specialist, Brother Jack McDuff.

Had Young not been heard from after his initial sessions for Prestige, history probably would have been written him off as just another Jimmy Smith pretender. His work on 'Testifying' and its sequels, 'Young Blues' (1960) and 'Groove Street' (1962)—all of which find him supported by Smith's regular guitarist Thornel Schwartz—are gutsy, swinging, but ultimately unambitious blues excursions. His other notable work as a sideman with the label came on Jimmy Forrest's 1960 set 'Forrest Fire', on which he backed the St. Louis tenor player best known for his No. 1 R&B 1952 instrumental hit Night Train, later a fixture of James Brown's sets.

Initially Young's fortunes did not perceptibly change when he moved from Prestige to Blue Note in 1964. By that time, Jimmy Smith had departed the label for Verve, where he was racking up significant pop hits, and Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff's label had responded by bringing on virtually every organ player who could play a convincing blues lick—Big John Patton, Baby Face Willette, Freddie Roach, and, finally, Young. (Others, like Reuben Wilson and Lonnie Smith, would follow.)

Young was at first cast as a studio sidekick to Blue Note utility player Grant Green. The four albums on which the organist supported the guitarist between 1963-65 are pretty typical fare: greasy rib-joint originals and pop covers like I Want to Hold Your Hand distinguished by Green's dithering, emotionally disengaged soloing—he was a player who manufactured his own clichés—and Young's heavily chorded support.

Green was present on the Nov. 12, 1964, session that would become Young's Blue Note debut as a leader, Into Somethin'. But the quartet date was more notable for the other sidemen. The drummer was Elvin Jones, who was propelling the explorations of John Coltrane's famed quartet. The tenor sax chair was occupied by Sam Rivers; only recently, and very briefly, a member of Miles Davis' band (on the recommendation of the trumpeter's teenage drummer, Tony Williams), Rivers was hip to the New Thing, and his angular playing enlivened a session that suggested Young was looking beyond hard bop and soul-jazz for inspiration.

What came next in the organist's career can be heard on Larry Young in Paris, an astonishing two-CD set released earlier this year by indie jazz label Resonance Records. The album fills in a critical gap in Young's musical development.

In late 1964, Young traveled to Paris to participate in some dates organized by tenor saxophonist Nathan Davis, a close friend of multi-instrumentalist and Coltrane collaborator Eric Dolphy, who had died suddenly in Berlin that June. The performances, put together in homage to Dolphy, also featured the 19-year-old trumpeter and composer Woody Shaw. Live quartet appearances recorded by French radio find Young expanding his sound in probing, out-of-time solos that show off his imaginative tonal control of the B3. Performances cut around the same time with a larger unit of French musicians include a version of Young's composition Talkin' About J.C., a tribute to Coltrane he had already cut for both Prestige and, with Green, for Blue Note.

After his return to the U.S. after these gigs in 1965, Young began playing informally with Coltrane at the saxophonist's Long Island home and embraced Islam. He was clearly moving in a new direction, one that was without precedent for his instrument. As his friend Michael Cuscuna says in the notes for the comprehensive collection of the keyboardist's Blue Note sessions for his Mosaic Records label, "[T]he market was overrun with moderately successful, second-generation, third-rate chitlin pumpers. And Larry Young offered a way out of all that."

He made his breakthrough with the November 1965 date that produced the classic Blue Note album Unity. Featuring Shaw (who contributed three compositions, including Zoltan, first performed with Young in Paris, and the trumpeter's signature The Moontrane), tenor man Joe Henderson, and Elvin Jones, the collection found a group of musicians fighting their way through the thickets of hard bop and soul-jazz into unplumbed territory refreshed by the free-spirited discoveries of such contemporaries as Trane, Dolphy, and Albert Ayler.

In the wake of 'Unity,' the newly inspired Young cut four more albums in 1966-69, one of which was only issued posthumously. All of them featured a couple of products of the keyboardist's New Jersey hometown, tenor player Herbert Morgan (a free-blowing full-on Coltrane disciple) and drummer Eddie Gladden (a polyrhythmic monster in the Elvin Jones mold).

The blazing, wholly satisfying '66 free jazz throwdown Of Love and Peace found Young totally embracing Trane's blazing, spiritually imbued template; his skittering, escalating solos represent a complete break with his soul-jazz origins. However, his subsequent sessions for Blue Note reflect some uncertainty about his direction, and possibly about the commercial viability of his chosen path: Wailing wild-fire originals sit side-by-side with a drab cover of Chris Montez's limp 1966 pop hit "Call Me" or flat ballad readings of "My Funny Valentine" and "Wild Is The Wind" featuring vocals by his wife Althea.

The year 1969 proved to be Young's annum mirabilis, as he arrived on the white-hot cusp of the fusion explosion. In quick succession, he jammed in the studio with Jimi Hendrix; supported John McLaughlin—fresh from his work behind Miles Davis on what was arguably the first jazz-rock fusion album, In A Silent Way—on the English guitarist's storming solo set Devotion; played electric piano on four tracks for Davis' monumental two-LP fusion extravaganza Bitches Brew; and, following McLaughlin's relocation to the U.S., joined the guitarist and Davis' longtime drummer Tony Williams in the latter's eponymous Lifetime.

The latter group's two-LP 1969 debut Emergency! completely lived up to its exclamatory title, and probably contains Young's most completely realized playing; even Williams' limpid vocalizing has not denatured its power over time. Loud, slamming, and uncompromising, the collection fuses free-jazz unpredictability with pure rock voltage. Young excels in this format: His scattergun solos resemble nothing so much as Monk on an electrified acid trip, while his molten comping rises out of the mix like volcanic eruptions.

'Emergency!' appeared to presage something completely radical in jazz, but its promise went unfulfilled, as Williams stepped away from the more extreme formulations of the band's bow. Possibly seeking increased marquee value, the drummer enlisted former Cream bassist-vocalist Jack Bruce for the 1970 follow-up Turn It Over; given Young's facility on the B3's bass pedals, it was a redundant proposition at best. The format appeared exhausted by the time Ted Dunbar replaced McLaughlin on the third TWL set Ego, issued in 1971.

Young did not stick around for Lifetime's swan song, 1973's aptly titled 'The Old Bum's Rush'. By that time, McLaughlin had formed his own massively popular fusion unit, the Mahavishnu Orchestra (the name of which was inspired by the guitarist's newly adopted surname, a reflection of his devotion to guru Sri Chinmoy). The organist made a final appearance with McLaughlin on 1972's Love Devotion Surrender, a Coltrane-inspired pairing co-headlining fellow Chinmoy acolyte Carlos Santana; the album's A Love Supreme—actually a reading of Acknowledgement, the first movement of Trane's 1965 masterwork of the same title—found Young elegantly stating the track's theme amid McLaughlin and Santana's frenetic soloing.

It's very possible that by the time Young entered the studio with McLaughlin and Santana, he was suffering from SFB—Severe Fusion Burnout. Though he had been among the first to plant the flag in jazz-rock turf, his efforts had been trumped commercially by a number of bands founded by fellow Miles Davis sidemen—Mahavishnu, Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul's Weather Report, Chick Corea's Return to Forever, and Herbie Hancock's Headhunters. So, for the moment at least, he turned his back on electric music for one final blast of free-jazz greatness.

Released in 1973 by the New York jazz indie Perception Records and deeply indebted to Trane and Sun Ra, 'Lawrence of Newark' found Young harkening back to the impressionistic, relatively free-form style of his latter-day Blue Note records, and at times sports a heavy Middle Eastern influence (cf. "Khalid of Space—Part Two"). His collaborators couldn't have been better: sidemen included an uncredited Pharaoh Sanders on saxophones, Ornette Coleman's rampaging guitarist James Blood Ulmer, bassist and onetime Tony Williams sideman Juini Booth, and percussionist Juma Santos, one of Jimi Hendrix's latter-day band mates.

It was an expansive summation of Young's free-form brilliance, but 'Lawrence of Newark' disappeared virtually upon release, as Perception closed its doors for good in early 1974.

Somewhat stranded in an artistic no man's land, Young moved wholeheartedly to the commercial right with the last two albums released under his during his lifetime, 'Larry Young's Fuel' (1975) and 'Spaceball' (1976), both on the pop label Arista. Undoubtedly formulated with an ear cocked to Hancock's 1973 smash Head Hunters, the LPs feature manufactured jazz-funk of the lowest order, with the bandleader leaning heavily on a battery of synthesizers to no significant effect. The name of his group notwithstanding, Larry Young appeared to be out of gas.

In his last years, Young gigged around New York behind soulful sax man Houston Person and with his own trio, which also included drummer-pianist Joe Chambers. His last date was a duo session with Chambers, the understated and exquisite 'Double Exposure'. According to Cuscuna, he had already been inked to a deal with Warner Bros. Records when he succumbed suddenly to pneumonia in March 1978, after being rushed to the hospital with stomach pains.

Young happily enjoys a higher profile today than he did in the final years of his career and life, and his music can be readily found if you hunt for it. Most of his discography is in print on CD and available on the web, and the recent, revelatory 'Larry Young in Paris' has thrown his prescient achievements of the mid-'60s into bold relief. One of jazz's most creative soloists and adventurous bandleaders, he demands acquaintance among listeners who like to play on the far frontiers of sound.

https://jazztimes.com/news/previously-unreleased-60s-larry-young-performances-out-in-march/

Previously Unreleased ’60s Larry Young Performances Out in March, 2016

First new release of music by the organist in 38 years

JazzTimes Larry Young

Musicians featured on these recordings include trumpeter Woody Shaw, tenor saxophonist and bandleader Nathan Davis and drummer Billy Brooks. Supporting players include pianist Jack Diéval, tenor saxophonist Jean-Claude Fohrenbach and bassist Jacques B. Hess; Italian drummer Franco Manzecchi, Jamaican trumpet player Sonny Grey and Guadaloupean percussionist Jacky Bamboo. This album marks the first new release of Larry Young music in 38 years.

According to a press release, “This project came about in 2012 when producer Zev Feldman traveled to France to explore the ORTF (Office of French Radio and Television) archives (the media vaults overseen by the French National Audiovisual Institute (INA) in the hope of finding undiscovered treasures, which he suspected he might find there. Feldman asked INA executives about specific artists and was stunned to learn that the vaults contained recordings documenting some of the greatest American jazz musicians who lived in, or visited, Paris in the 1960s, including Larry Young. Resonance Records presents in this album tapes that had been sitting idly in the vaults for nearly 50 years, scrupulously maintained by INA.”

Resonance plans to release other projects from the INA vaults.

TRACK LIST:

Disc One

Trane Of Thought (6:46)

Talking About JC (14:53)

Mean To Me (4:12)

La Valse Girls (16:09)

Discotheque (10:43)

Disc Two

Luny Tune (4:36)

Beyond All Limits (7:36)

Black Nile (13:59)

Zoltan (20:31)

Larry’s Blues (6:13)

http://nodepression.com/album-review/larry-young%E2%80%99s-oceanic-organ-resurfaces-after-38-years

Album Review

Larry Young’s oceanic organ resurfaces after 38 years

Larry Young - In Paris: The ORTF Recordings

This two-CD set represents the first recordings in nearly 38 years by the late, pioneering organist who played on Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, Carlos Santana's Love, Devotion and Surrender, and John McLaughlin's Devotion and in the ground-breaking jazz-fusion group The Tony Williams Lifetime. These recordings feature the innovative trumpeter Woody Shaw who would soon record with Young on perhaps his best-known album under his own name Unity, recorded in Nov. 1965 for Blue Note.

These never before released recordings ,made in France, date from 1964 and represent important milestones in the development of the greatest innovator in jazz organ since Jimmy Smith. If Smith was the Oscar Peterson of the organ, Young was the McCoy Tyner -- or the John Coltrane -- of organ, as some claimed.

Organist Larry Young. Courtesy allaboutjazz.com

Among jazz’s freshest voices, Young’s organ swam like a shadowy dolphin, unfurling Tyner-esque fourths for a more expansive, mysterious sound. As Young often evoked oceanic depths, Woody Shaw’s trumpet caught the sun like a sea bird’s flashing wings. Shaw’s innovations included systematic “symmetrical cycles of intervals” and a “staggering fluency in pentatonic and modal scales,” says trumpeter Brian Lynch.1

Shaw’s percolating, fiery ideas hang together brilliantly atop Young’s streaming whirlpools. This two-CD set includes two excellent Shaw tunes, "Zoltan" and "Beyond All Limits" from their soon-recorded Unity album, and Wayne Shorter’s classic, “Black Nile.”

In Paris finds Young feeding on the blues and hard-bop traditions but you also hear steps towards the unknown, strivings for revelation. The discs also include a rare recording of Young on piano on "Larry's Blues," which closes the set.

In later years, Young grew more spiritual, free and modal on his recordings, embracing Islam and changing his name to Khalid Yasin. Of Love and Peace, with saxophonist-flutist James Spaulding and trumpeter Eddie Gale, and long renditions of Morton Gould's "Pavanne" and "Seven Steps to Heaven," allows his misterioso organ plenty of room to soar and marvel the listener. He recorded memorably with saxophonist Pharoah Sanders (listed as a "mystery guest") and guitarist James "Blood" Ulmer on Lawrence of Newark in 1973, a performance at once earthy and transporting.

Young died in 1978, at 37 with pneumonia symptoms, though the exact cause of death remains unclear.

The Paris recordings also represents one of the many highlights of the extraordinary Resonance Records, which specializes in searching out historic unreleased jazz recordings. In 2014, they released a late John Coltrane recording, Offering: Live at Temple University, which was among the most celebrated historical recordings of the year.

Producer Zev Feldman, who's been called "The Indiana Jones of Jazz," travels around the world to unearth quality previously-unreleased recordings. Resonance's most recent releases include an brilliant and historic album by The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra; two by Stan Getz from 1967, including a reunion with Joao Gilberto, the bossa-nova master who helped Getz become a jazz superstar; live recordings by the supreme jazz vocal diva Sarah Vaughan; and other live recordings by the great pianist Bill Evans, Some Other Time: The Lost Session from the Black Forest, the only studio recordings by the trio including bassist Eddie Gomez and drummer Jack DeJohnette.

Image Courtesy resonancerecords.org

Feldman's great uncle was the revered Milwaukee jazz clarinet player Joe Aaron, who served the Milwaukee community where he taught music for over 50 years. Milwaukee pianist Frank Stemper calls Aaron "the best clarinetist I ever heard." But Joe's older brother, Zev’s great uncle Abe Aaron, was the real family star. He toured the world playing jazz (all reeds) with Les Brown (on all of those famous USO tours with Bob Hope and in the studio), Jack Teagarden, and others in Hollywood studios. Zev’s cousin is flutist Rick Aaron, who still performs in the Milwaukee area.

Feldman's vision and enterprise recently earned him Down Beat magazine's "rising star producer" award in its 2016 jazz critics poll.

The Resonance recordings website is here.

____________

- Brian Lynch, Brass School: "A Latin Jazz Perspective on Woody Shaw," Down Beat Magazine, April, 2016, 76-81

- This review was originally published in Culture Currents (Vernaculars Speak) http://kevernacular.com/?p=7595 and in shorter form in The Shepherd Express

THE MUSIC OF LARRY YOUNG: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH MR. YOUNG:

Larry Young - 'Unity'- (Complete Album)--1965--Blue Note records:

Larry Young - 'Tyrone"

Larry Young - 'Of Love And Peace' [Full Album]--Blue Note 1966:

Personnel: Larry Young: Hammond organ Eddie Gale: trumpet James Spaulding: flute on "Of Love And Peace", alto saxophone on remainder Herbert Morgan: tenor saxophone Wilson Moorman III: drums Jerry Thomas: drums

Tracklist:

Pavanne (14:12)

Of Love And Peace (6:34)

Seven Steps To Heaven (10:17)

Falaq (10:08)

Larry Young - 'Lawrence Of Newark'--Full album--1973:

Larry Young's Fuel:

06:07 2. I Ching (Book of Changes)

12:32 3. Turn off the Lights

19:35 4. Floating

23:48 5. H+J=B (Hustle+Jam=Bread)

30:07 6. People Do Be Funny

33:49 7. New York Electric Street Music

Bass [Fender Jazz Bass, Eliminator 1 Bottom Speaker, B-4 Head] – Fernando Saunders

Congas, Gong [Korean], Chimes [Yucatan Wind Chime] – Rob Gottfried

Engineer – Brian MacDonald, Doug Clark (3)

Guitar [Gibson Es-335] – Santiago (Sandy) Torano*

Synthesizer [Mini Moog Synthesizer, Cdx-0652 Portable Moog Organ, Frm-s810 Freeman String Symphonizer, Hammond Organ B-3], Electric Piano [Fender Rhodes],

Piano [Acoustic] – Larry Young

Vocals – Larry Young (tracks: B4), Linda "Tequila" Logan (tracks: A1, A3, B3)

Larry Young: "Mother Ship" (rec. 1969, released 1980)

Larry Young (musician)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Larry Young | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Khalid Yasin |

| Born | 7 October 1940 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | 30 March 1978 (aged 37) New York City, New York |

| Genres | Jazz, soul jazz, jazz-funk, modal jazz, jazz fusion |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter |

| Instruments | Organ |

| Labels | Blue Note |

Larry Young (also known as Khalid Yasin [Abdul Aziz]; 7 October 1940, in Newark, New Jersey – 30 March 1978, in New York City) was an American jazz organist and occasional pianist. Young pioneered a modal approach to the Hammond B-3 (in contrast to Jimmy Smith's soul jazz style). However, he did also play soul jazz, among other styles.[1]

Contents

Biography

Young played with various R&B bands in the 1950s before gaining jazz experience with Jimmy Forrest, Lou Donaldson, Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley and Tommy Turrentine. Recording as a leader for Prestige from 1960, Young made a number of soul jazz discs, Testifying, Young Blues and Groove Street. When Young went to Blue Note in 1964, his music began to show the marked influence of John Coltrane. In this period, he produced his most enduring work. He recorded many times as part of a trio with guitarist Grant Green and drummer Elvin Jones, occasionally augmented by additional players; most of these albums were released under Green's name, though Into Somethin' (with Sam Rivers on saxophone) became Young's Blue Note debut. Unity, recorded in 1965, remains his best-known album; it features a front line of Joe Henderson and the young Woody Shaw. Subsequent albums for Blue Note (Contrasts, Of Love and Peace, Heaven On Earth, Mother Ship)

also drew on elements of the '60s avant-garde and utilised local

musicians from Young's hometown of Newark. Young then became a part of

some of the earliest fusion experiments: first on Emergency! with the Tony Williams Lifetime (with Tony Williams and John McLaughlin) and also on Miles Davis's Bitches Brew.

His sound with Lifetime was made distinct by his often very percussive

approach and often heavy use of guitar and synthesizer-like effects. He

is also known to rock fans for a jam he recorded with Jimi Hendrix, which was released after Hendrix's death on the album Nine to the Universe.

His characteristic sound involved management of the stops on the

Hammond organ, producing overtone series that caused an ethereal,

drifting effect; a sound that is simultaneously lead and background.

In March 1978 he checked into the hospital for stomach pains. He died

there on March 30, 1978, while being treated for what is said to be

pneumonia. However, the actual cause of his death is unclear.[2][3]

Discography

As leader

- 1960: Testifying

- 1960: Young Blues

- 1962: Groove Street

- 1964: Into Somethin'

- 1965: Unity

- 1966: Of Love and Peace

- 1967: Contrasts

- 1968: Heaven on Earth

- 1969: Mother Ship

- Others

- 1973: Lawrence of Newark (Perception)

- 1975: Fuel (Arista)

- 1976: Spaceball (Arista)

- 1977: The Magician (Acanta/Bellaphon)

- 2016: Larry Young in Paris:The ORTF Sessions (Resonance, recorded for French radio in 1964 and 1965)

As sideman

With Joe Chambers- Double Exposure (1978, Muse)

- Bitches Brew (1969, Columbia)

- Big Fun

- Gumbo! (Prestige, 1963) - bonus tracks on CD only

- Forrest Fire (New Jazz, 1960)

- Talkin' About! (1963, Blue Note)

- Street of Dreams (1964, Blue Note)

- I Want to Hold Your Hand (1965, Blue Note)

- His Majesty King Funk (1965, Verve)

- Love Shout (Prestige, 1963)

- I'm Shooting High (Prestige, 1963)

- The Great Gildo (Prestige, 1964)

- Devotion (1969, Douglas)

- Love Devotion Surrender (1972, Columbia) - with Carlos Santana

- In the Beginning (Muse 1965 [1983])

- Natural Soul (Prestige, 1968)

- Emergency (1969, Polydor)

- Turn It Over (1970, Polydor)

- Ego (1971, Polydor)

- Love Cry Want (1997, Newjazz.com)

References

- Jarud Pauley, Encyclopedia of Jazz Musicians http://www.jazz.com/encyclopedia/young-larry-jr-khaled-yasin