SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2016

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2016

VOLUME THREE NUMBER THREE

HENRY THREADGILL

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

CHRISTIAN MCBRIDE

(December 3-9)

DEXTER GORDON

(December 10-16)

JEANNE LEE

(December 17-23)

CASSANDRA WILSON

(December 24-30)

SAM RIVERS

(December 31-January 6)

TERRY CALLIER

(January 7-13)

ODETTA

(January 14-20)

LESTER BOWIE

(January 21-27)

SHIRLEY BASSEY

(January 28-February 3)

HAMPTON HAWES

(February 4-10)

GRACHAN MONCUR III

(February 11-17)

LARRY YOUNG

(February 18-24)

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2011/12/sam-rivers-1923-2011-multi.html

Saturday, December 31, 2011

SAM RIVERS (1923-2011):

Multi-Instrumentalist, Saxophonist, Arranger, Bandleader, And Composer

CHRISTIAN MCBRIDE

(December 3-9)

DEXTER GORDON

(December 10-16)

JEANNE LEE

(December 17-23)

CASSANDRA WILSON

(December 24-30)

SAM RIVERS

(December 31-January 6)

TERRY CALLIER

(January 7-13)

ODETTA

(January 14-20)

LESTER BOWIE

(January 21-27)

SHIRLEY BASSEY

(January 28-February 3)

HAMPTON HAWES

(February 4-10)

GRACHAN MONCUR III

(February 11-17)

LARRY YOUNG

(February 18-24)

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2011/12/sam-rivers-1923-2011-multi.html

Saturday, December 31, 2011

SAM RIVERS (1923-2011):

Multi-Instrumentalist, Saxophonist, Arranger, Bandleader, And Composer

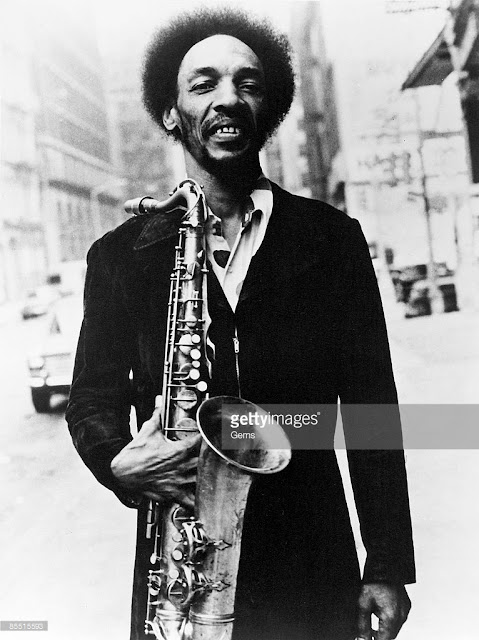

Sam Rivers

(1923-2011)

(1923-2011)

All,

Another great and iconic African American musician and composer is gone--the internationally acclaimed multi-instrumentalist, tenor saxophonist, and composer Sam Rivers. Thankfully, I was privileged to see and hear Sam perform many times in New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and Detroit. During an astounding and highly varied six decade long career (!) Sam played and recorded with everyone from Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie to Billie Holiday, T-Bone Walker, Tony Williams, David Holland, Cecil Taylor, David Holland, and Anthony Braxton among many others. He also organized and led a large number of his own ensemble groups in duo, trio, quartet, quintet, septet, octet, and orchestral big band settings. His legendary loft space for music and dance performance that he founded with his wife Beatrice in downtown Manhattan was called Studio Rivbea and was THE place to hear really original and dynamic avant-garde Jazz by a wide array of musicians and composers in New York in the mid and late 1970s and he also led a terrific anf highly influential Jazz orchestra of over 20 musicians throughout the '80s, '90s. and well into the 2000s. He was yet another real GIANT of the music in the post-1950s era. What an artist! What follows is an extended homage to and celebration of this man and his indelible music via words, visual images and of course SOUND. ENJOY! and RIP Sam...

Kofi

Sam Rivers, Jazz Artist of Loft Scene, Dies at 88

by NATE CHINEN

December 27, 2011

New York Times

Sam Rivers, an inexhaustibly creative saxophonist, flutist, bandleader and composer who cut his own decisive path through the jazz world, spearheading the 1970s loft scene in New York and later establishing a rugged outpost in Florida, died on Monday in Orlando, Fla. He was 88.

The cause was pneumonia, his daughter Monique Rivers Williams said.

With an approach to improvisation that was garrulous and uninhibited but firmly grounded in intellect and technique, Mr. Rivers was among the leading figures in the postwar jazz avant-garde. His sound on the tenor saxophone, his primary instrument, was distinctive: taut and throaty, slightly burred, dark-hued. He also had a recognizable voice on the soprano saxophone, flute and piano, and as a composer and arranger.

Music ran deep in his family. His grandfather Marshall W. Taylor published one of the first hymnals for black congregations after emancipation, “A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies,” in 1882. His mother, the former Lillian Taylor, was a pianist and choir director, and his father, Samuel Rivers, was a gospel singer. They were on tour with the Silvertone Quintet in El Reno, Okla., when Samuel Carthorne Rivers was born, on Sept. 25, 1923.

Growing up in Chicago and on the road, Mr. Rivers studied violin, piano and trombone. After his father had a debilitating accident in 1937, he moved with his mother to Little Rock, Ark., where he zeroed in on the tenor saxophone. Joining the Navy in the mid-’40s, he served for three years.

Mr. Rivers enrolled in the Boston Conservatory of Music in 1947 and later transferred to Boston University, where he majored in composition and briefly took up the viola and fell into the busy Boston jazz scene.

He made an important acquaintance in 1959: Tony Williams, a 13-year-old drummer who already sounded like an innovator. Together they delved into free improvisation, occasionally performing in museums alongside modernist and abstract paintings.

By 1964 Mr. Williams was working with the trumpeter Miles Davis and persuaded him to hire Mr. Rivers, who was with the bluesman T-Bone Walker at the time, for a summer tour. Mr. Rivers’s blustery playing with the Miles Davis Quintet, captured on the album “Miles in Tokyo,” suggested a provocative but imperfect fit. Wayne Shorter replaced him in the fall.

On a series of Blue Note recordings in the middle to late ’60s, beginning with Mr. Williams’s first album as a leader, “Life Time,” Mr. Rivers expressed his ideas more freely. He made four albums of his own for the label, the first of which — “Fuchsia Swing Song,” with Mr. Williams, the pianist Jaki Byard and the bassist Ron Carter, another Miles Davis sideman — is a landmark of experimental post-bop, with a free-flowing yet structurally sound style. “Beatrice,” a ballad from that album Mr. Rivers named after his wife, would become a jazz standard.

Beatrice Rivers died in 2005. In addition to his daughter Monique, Mr. Rivers is survived by two other daughters, Cindy Johnson and Traci Tozzi; a son, Dr. Samuel Rivers III; five grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren.

Mr. Rivers pushed further toward abstraction in the late ’60s, moving to New York and working as a sideman with the uncompromising pianists Andrew Hill and Cecil Taylor. In 1970 he and his wife opened Studio Rivbea, a noncommercial performance space, in their loft on Bond Street in the East Village. It served as an avant-garde hub through the end of the decade, anchoring what would be known as the loft scene.

The albums Mr. Rivers made for Impulse Records in the ’70s would further burnish his reputation in the avant-garde. After Studio Rivbea closed in 1979, Mr. Rivers continued to lead several groups, including a big band called the Rivbea Orchestra, a woodwind ensemble called Winds of Change and a virtuosic trio with the bassist Dave Holland and the drummer Barry Altschul. With the trio, Mr. Rivers often demonstrated his gift as a multi-instrumentalist, extemporizing fluidly on saxophone, piano and flute.

Mr. Rivers tacked toward more mainstream sensibilities from 1987 to 1991, when he worked extensively with an early influence, the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. While touring through Orlando with Gillespie in 1991, Mr. Rivers met some of the skilled musicians employed by the area’s theme parks, who persuaded him to move there and revive the Rivbea Orchestra. He lived most recently in nearby Apopka, Fla.

The music made by his band in the 1990s and beyond was as spirited and harmonically dense as anything in Mr. Rivers’s musical history. And the trio at its core — Mr. Rivers, the bassist Doug Mathews and the drummer Anthony Cole — also performed on its own, honing a dynamic versatility distinct from that of any other group in jazz.

Mr. Rivers’s late-career renaissance was confirmed by the critical response to “Inspiration” and “Culmination,” two albums he recorded for RCA in 1998 with a New York big band assembled by the alto saxophonist Steve Coleman. In 2000, Mr. Rivers led the Orlando iteration of the Rivbea Orchestra in a concert presented by Jazz at Lincoln Center. The next year he served as the fiery eminence on “Black Stars,” an acclaimed album by the 26-year-old pianist Jason Moran.

This year saw the release of “Sam Rivers and the Rivbea Orchestra — Trilogy” (Mosaic), a three-CD set featuring recordings from 2008 and 2009. His last performance was in October in DeLand, Fla.

In 2006. the Vision Festival, a nonprofit New York event aesthetically indebted to the loft scene, honored Mr. Rivers with a Sam Rivers Day program featuring both his bands. The names of two of the bustling pieces performed were, appropriately, “Flair” and “Spunk.”

SAM RIVERS

(b. September 25, 1923--d. December 26, 2011)

Rivers' father was a church musician, touring with a gospel quartet. Rivers was raised in Chicago and then Little Rock, Arkansas, where his mother taught music and sociology at Shorter College. He began taking piano and violin lessons at about the age of five. He later played trombone, before finally settling on the tenor. Early favorites were Don Byas, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Buddy Tate. Rivers moved to Boston in 1947, where he studied at the Boston Conservatory of Music and, later, Boston University. There, he played in Herb Pomeroy's little big band, which, in the early '50s, also featured such players as Jaki Byard, Nat Pierce, Quincy Jones, and Serge Chaloff.

Rivers left school in 1952. He moved to Florida for a time, then returned to Boston in 1958, where he again played with Pomeroy. Rivers became active in the local scene. He formed his own quartet with pianist Hal Galper, and played on his first Blue Note recording session with pianist/composer Tadd Dameron. In 1959, he began playing with 13-year-old Tony Williams. It was about this time that Rivers became involved in the avant-garde. He developed a free improvisation group with Williams. Perhaps befitting his educational background, Rivers approached free jazz from more of a classical perspective, in contrast to the style of his contemporary, Ornette Coleman, who came out of the blues.

In the early '60s, Rivers became involved with Archie Shepp, Bill Dixon, Paul Bley, and Cecil Taylor, all members of the Jazz Composer's Guild. In 1964, Rivers moved to New York. That July, Miles Davis hired Rivers on Tony Williams' recommendation. The group played three concerts in Japan; one was recorded and the results released on an LP. In August of 1964, following the brief experience with Davis, Rivers played on Life Time (Blue Note), Williams' first album as a leader. Later that year, Rivers led his own session for Blue Note, Fuchsia Swing Song, which documented his inside/outside approach. Rivers led four more dates for Blue Note in the '60s. In the middle part of the decade, he also recorded with Larry Young, Bobby Hutcherson, and Andrew Hill. In 1969, he toured Europe with Cecil Taylor in a band that also included Andrew Cyrille and Jimmy Lyons. In 1970, Rivers -- along with his wife, Bea -- opened a studio in Harlem where he held music and dance rehearsals. The space relocated to a warehouse in the Soho section of New York City. Named Studio Rivbea, the space became one of the most well-known venues for the presentation of new jazz. Rivers' own Rivbea Orchestra rehearsed and performed there, as did his trio and his Winds of Change woodwind ensemble. Rivers' trio of the time was a free improvisation ensemble in the purest sense. The group used no written music whatsoever, relying instead on a stream-of-consciousness approach that differed structurally from the head-solo-head style that still dominated free jazz. Much of this early- to mid-'70s music was documented on the Impulse! label.

In 1976, Rivers began an association with bassist Dave Holland. The duo recorded enough music for two albums, both of which were released on the Improvising Artists label. Opportunities to record became more scarce for Rivers in the late '70s, though he did record occasionally, notably for ECM; his Contrasts album for the label was a highlight of his post-Blue Note work. In the '80s, Rivers relocated to Orlando, Florida, where he created a scene of his own. Rivers formed a new version of his Rivbea Orchestra, using local musicians who made their living playing in the area's theme parks and myriad tourist attractions. From the '80s into the new millennium, Rivers recorded albums on his own Rivbea Sound label and other imprints as well, including a pair of critically acclaimed big band albums for RCA. Sam Rivers died of pneumonia on December 26, 2011; he was 88 years old.

http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/music-arts/sam-rivers-jazz-sax-great-hosted-village-concerts-dead-88-article-1.997947

December 27, 2011

New York Times

Sam Rivers, an inexhaustibly creative saxophonist, flutist, bandleader and composer who cut his own decisive path through the jazz world, spearheading the 1970s loft scene in New York and later establishing a rugged outpost in Florida, died on Monday in Orlando, Fla. He was 88.

The cause was pneumonia, his daughter Monique Rivers Williams said.

With an approach to improvisation that was garrulous and uninhibited but firmly grounded in intellect and technique, Mr. Rivers was among the leading figures in the postwar jazz avant-garde. His sound on the tenor saxophone, his primary instrument, was distinctive: taut and throaty, slightly burred, dark-hued. He also had a recognizable voice on the soprano saxophone, flute and piano, and as a composer and arranger.

Music ran deep in his family. His grandfather Marshall W. Taylor published one of the first hymnals for black congregations after emancipation, “A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies,” in 1882. His mother, the former Lillian Taylor, was a pianist and choir director, and his father, Samuel Rivers, was a gospel singer. They were on tour with the Silvertone Quintet in El Reno, Okla., when Samuel Carthorne Rivers was born, on Sept. 25, 1923.

Growing up in Chicago and on the road, Mr. Rivers studied violin, piano and trombone. After his father had a debilitating accident in 1937, he moved with his mother to Little Rock, Ark., where he zeroed in on the tenor saxophone. Joining the Navy in the mid-’40s, he served for three years.

Mr. Rivers enrolled in the Boston Conservatory of Music in 1947 and later transferred to Boston University, where he majored in composition and briefly took up the viola and fell into the busy Boston jazz scene.

He made an important acquaintance in 1959: Tony Williams, a 13-year-old drummer who already sounded like an innovator. Together they delved into free improvisation, occasionally performing in museums alongside modernist and abstract paintings.

By 1964 Mr. Williams was working with the trumpeter Miles Davis and persuaded him to hire Mr. Rivers, who was with the bluesman T-Bone Walker at the time, for a summer tour. Mr. Rivers’s blustery playing with the Miles Davis Quintet, captured on the album “Miles in Tokyo,” suggested a provocative but imperfect fit. Wayne Shorter replaced him in the fall.

On a series of Blue Note recordings in the middle to late ’60s, beginning with Mr. Williams’s first album as a leader, “Life Time,” Mr. Rivers expressed his ideas more freely. He made four albums of his own for the label, the first of which — “Fuchsia Swing Song,” with Mr. Williams, the pianist Jaki Byard and the bassist Ron Carter, another Miles Davis sideman — is a landmark of experimental post-bop, with a free-flowing yet structurally sound style. “Beatrice,” a ballad from that album Mr. Rivers named after his wife, would become a jazz standard.

Beatrice Rivers died in 2005. In addition to his daughter Monique, Mr. Rivers is survived by two other daughters, Cindy Johnson and Traci Tozzi; a son, Dr. Samuel Rivers III; five grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren.

Mr. Rivers pushed further toward abstraction in the late ’60s, moving to New York and working as a sideman with the uncompromising pianists Andrew Hill and Cecil Taylor. In 1970 he and his wife opened Studio Rivbea, a noncommercial performance space, in their loft on Bond Street in the East Village. It served as an avant-garde hub through the end of the decade, anchoring what would be known as the loft scene.

The albums Mr. Rivers made for Impulse Records in the ’70s would further burnish his reputation in the avant-garde. After Studio Rivbea closed in 1979, Mr. Rivers continued to lead several groups, including a big band called the Rivbea Orchestra, a woodwind ensemble called Winds of Change and a virtuosic trio with the bassist Dave Holland and the drummer Barry Altschul. With the trio, Mr. Rivers often demonstrated his gift as a multi-instrumentalist, extemporizing fluidly on saxophone, piano and flute.

Mr. Rivers tacked toward more mainstream sensibilities from 1987 to 1991, when he worked extensively with an early influence, the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. While touring through Orlando with Gillespie in 1991, Mr. Rivers met some of the skilled musicians employed by the area’s theme parks, who persuaded him to move there and revive the Rivbea Orchestra. He lived most recently in nearby Apopka, Fla.

The music made by his band in the 1990s and beyond was as spirited and harmonically dense as anything in Mr. Rivers’s musical history. And the trio at its core — Mr. Rivers, the bassist Doug Mathews and the drummer Anthony Cole — also performed on its own, honing a dynamic versatility distinct from that of any other group in jazz.

Mr. Rivers’s late-career renaissance was confirmed by the critical response to “Inspiration” and “Culmination,” two albums he recorded for RCA in 1998 with a New York big band assembled by the alto saxophonist Steve Coleman. In 2000, Mr. Rivers led the Orlando iteration of the Rivbea Orchestra in a concert presented by Jazz at Lincoln Center. The next year he served as the fiery eminence on “Black Stars,” an acclaimed album by the 26-year-old pianist Jason Moran.

This year saw the release of “Sam Rivers and the Rivbea Orchestra — Trilogy” (Mosaic), a three-CD set featuring recordings from 2008 and 2009. His last performance was in October in DeLand, Fla.

In 2006. the Vision Festival, a nonprofit New York event aesthetically indebted to the loft scene, honored Mr. Rivers with a Sam Rivers Day program featuring both his bands. The names of two of the bustling pieces performed were, appropriately, “Flair” and “Spunk.”

SAM RIVERS

(b. September 25, 1923--d. December 26, 2011)

Artist Biography by Chris Kelsey

Few, if any, free jazz saxophonists approached music with the same degree of intellectual rigor as Sam Rivers; just as few have managed to maintain a high level of creativity over a long life. Rivers played with remarkable technical precision and a manifest knowledge of his materials. His sound was hard and extraordinarily well-centered, his articulation sharp, and his command of the tenor saxophone complete. Rivers' playing sometimes had an unremitting seriousness that could be extremely demanding, even off-putting. Nevertheless, the depth of his artistry was considerable. Rivers was as substantial a player as avant-garde jazz ever produced.

Rivers' father was a church musician, touring with a gospel quartet. Rivers was raised in Chicago and then Little Rock, Arkansas, where his mother taught music and sociology at Shorter College. He began taking piano and violin lessons at about the age of five. He later played trombone, before finally settling on the tenor. Early favorites were Don Byas, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Buddy Tate. Rivers moved to Boston in 1947, where he studied at the Boston Conservatory of Music and, later, Boston University. There, he played in Herb Pomeroy's little big band, which, in the early '50s, also featured such players as Jaki Byard, Nat Pierce, Quincy Jones, and Serge Chaloff.

Rivers left school in 1952. He moved to Florida for a time, then returned to Boston in 1958, where he again played with Pomeroy. Rivers became active in the local scene. He formed his own quartet with pianist Hal Galper, and played on his first Blue Note recording session with pianist/composer Tadd Dameron. In 1959, he began playing with 13-year-old Tony Williams. It was about this time that Rivers became involved in the avant-garde. He developed a free improvisation group with Williams. Perhaps befitting his educational background, Rivers approached free jazz from more of a classical perspective, in contrast to the style of his contemporary, Ornette Coleman, who came out of the blues.

In the early '60s, Rivers became involved with Archie Shepp, Bill Dixon, Paul Bley, and Cecil Taylor, all members of the Jazz Composer's Guild. In 1964, Rivers moved to New York. That July, Miles Davis hired Rivers on Tony Williams' recommendation. The group played three concerts in Japan; one was recorded and the results released on an LP. In August of 1964, following the brief experience with Davis, Rivers played on Life Time (Blue Note), Williams' first album as a leader. Later that year, Rivers led his own session for Blue Note, Fuchsia Swing Song, which documented his inside/outside approach. Rivers led four more dates for Blue Note in the '60s. In the middle part of the decade, he also recorded with Larry Young, Bobby Hutcherson, and Andrew Hill. In 1969, he toured Europe with Cecil Taylor in a band that also included Andrew Cyrille and Jimmy Lyons. In 1970, Rivers -- along with his wife, Bea -- opened a studio in Harlem where he held music and dance rehearsals. The space relocated to a warehouse in the Soho section of New York City. Named Studio Rivbea, the space became one of the most well-known venues for the presentation of new jazz. Rivers' own Rivbea Orchestra rehearsed and performed there, as did his trio and his Winds of Change woodwind ensemble. Rivers' trio of the time was a free improvisation ensemble in the purest sense. The group used no written music whatsoever, relying instead on a stream-of-consciousness approach that differed structurally from the head-solo-head style that still dominated free jazz. Much of this early- to mid-'70s music was documented on the Impulse! label.

In 1976, Rivers began an association with bassist Dave Holland. The duo recorded enough music for two albums, both of which were released on the Improvising Artists label. Opportunities to record became more scarce for Rivers in the late '70s, though he did record occasionally, notably for ECM; his Contrasts album for the label was a highlight of his post-Blue Note work. In the '80s, Rivers relocated to Orlando, Florida, where he created a scene of his own. Rivers formed a new version of his Rivbea Orchestra, using local musicians who made their living playing in the area's theme parks and myriad tourist attractions. From the '80s into the new millennium, Rivers recorded albums on his own Rivbea Sound label and other imprints as well, including a pair of critically acclaimed big band albums for RCA. Sam Rivers died of pneumonia on December 26, 2011; he was 88 years old.

http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/music-arts/sam-rivers-jazz-sax-great-hosted-village-concerts-dead-88-article-1.997947

New Yorker played with Miles Davis, Billie Holiday and T. Bone Walker

by BEN CHAPMAN

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

December 28 2011

Sam Rivers played saxophone with some of the all-time jazz and blues greats, including Billie Holliday, Miles Davis and B.B. King.

Sam Rivers, a legendary jazz saxophonist who threw raucous jam sessions in his west Village loft, died of pneumonia in Orlando on Monday. He was 88.

Rivers was born in El Reno, Oklahoma in 1923. He was heir to a musical legacy that began with his grandfather Marshall W. Taylor, who in 1882 published an early classic of African-American folk music, “A Collection of Revival Hymns & Plantation Melodies.”

Rivers’ mother and father played together in a local quartet and encouraged their son to study music from an early age.By age 13, Rivers settled on the tenor saxophone as his instrument of choice. He stuck with the sax for more than 70 years, cutting 35 albums and playing countless gigs with many of the greatest artists in jazz.

After a stint in the Navy as a young man, Rivers enrolled in the Boston Conservatory, where he would begin his career as a professional musician.

By the mid-1950’s Rivers was backing up Billie Holiday on the sax and acting as musical director for a number of great R&B acts including B.B. King and T-Bone Walker.

In 1964 he moved to New York and joined Miles Davis’s quintet, with whom he recorded the seminal live record “Miles in Tokyo.” In that year Rivers also began recording his own groups for Blue Note, eventually releasing four records as a band leader for the famed jazz label.

In 1970, Rivers and his wife Beatrice opened a jazz and dance performance space called Studio Rivbea in their Bond Street loft.

The freewheeling venue was a fixture of the Village’s art and jazz scene until 1979 when Rivers and his wife relocated to New Jersey.

Rivers moved to Orlando in 1991 and continued to record and tour until his death.

Rivers is survived by five children, five grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren. His wife Beatrice Rivers died in 2005.

His family is holding a private funeral service and plans are being made for a public memorial concert to be held in his honor.

With News Wire Servicesbchapman@nydailynews.com

Sam Rivers: A Compelling Force

by Kofi Natambu

August 29, 1984

Detroit Metro Times

by Kofi Natambu

August 29, 1984

Detroit Metro Times

“You don’t pin me down. I am as general as a musician can be, general and open. I have the scope of the whole thing and I really try to do it that way with every composition."

--Sam Rivers

Everything about Samuel Carthorne Rivers defies traditional attempts to blithely categorize or pigeonhole. In fact, his entire life history as a black creative musician suggests there is something seriously wrong with most general notions about what “jazz” is (or is supposed to be). A brilliant multi-instrumentalist and composer who excels with world-class proficiency on tenor and soprano saxophones, flute and piano. Rivers is a musician for whom the extraordinary is quite commonplace. It is Rivers’s extensive background in all the major styles and concepts of Afro-American music (which is the mainstream of all American music), that allows him to create freely in a multitude of settings.

Rivers was born Sept. 25, 1923 in El Reno, Oklahoma. The other significant fact about his birth is that it literally took place on the road. You see, Rivers comes from a family of very talented musicians. His grandfather, the Rev. Marshall W. Taylor, is famous for the publication of a volume of slave folk songs and gospel tunes. Sam’s very early years were spent in Chicago until his father died and the family moved to Arkansas when he was seven.

Sam’s extremely varied training in music began then. He studied and learned how to play several instruments, beginning with piano and then violin and alto saxophone. He also sang with his brother and two cousins in a group called—and you won’t believe this—the “Tiny Tims.”

After a stint in the Navy, Sam enrolled at the Boston Conservatory of Music. While there, Sam studied composition and viola, in addition to violin. At night Sam played tenor saxophone in an improvisational music setting at a small bar and grill. This was in Boston during the early 1950s, and it was jumping with great music and musicians—Jaki Byard, Charlie Mariano, Nat Pierce, Quincy Jones (then a trumpet player), Joe Gordon, Gigi Gryce and, of course, Cecil Taylor were a few notables on the scene. As Rivers described it: “There were three or four bands a night—never a dull moment. They’d start at noon and go to midnight. Two bands during the day and two at night. I was lucky—we played from seven to ten, but it was seven days a week”

During this period Rivers was also a regular member of a big band called ‘The Beboppers” that played the bop classics (Bird, Dizzy, Dameron et al). Despite this, Rivers’ main influences were, as he says: “Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins. Lester Young was my first influence, later Hawkins, Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis, people like that.” Even then Rivers, always an original and innovative stylist, did not imitate the styles of those he admired. He also consciously made a point of playing in a bebop vein without playing too many bop tunes.

The early 1960s marked a change in Rivers’ style and a turning point in his long career. He was still playing classical music and holding down a regular gig with blues groups and a Basie-like big band, but at the same time he was working with a new, more advanced group that included the then 16-year-old prodigy of the drums, the great Tony Williams. Hal Galper was on piano and Rivers on various reeds, Rivers took a never-look-back plunge into the so-called “avant-garde” of black creative music. Rivers states: “We were listening to Cecil Taylor’s music and Ornette Coleman’s music. So that opened the music up. It was a natural evolution for me.” Rivers had already been playing compositions without a preset chord structure before he heard Coleman and Taylor. Their bold innovations only confirmed the validity of his own experiments. Rivers considers this development in the music to be the most radical innovation in music in the last fifty years.

It was in 1964 after playing on the road with the legendary blues singer and guitarist T-Bone Walker that Rivers was first brought to the attention of a national audience when he was asked to play with the Miles Davis group. Though Rivers only played with Miles for six months, he made an indelible impression by playing some very fiery and wildly original tenor saxophone on a now-classic recording called Miles Davis Live in Tokyo (recently reissued by Columbia on a 1983 two-fer called Heard ‘Round the World). This recording identified Rivers as a major force to be reckoned with and put him in the upper echelon of saxophonists with the likes of John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins and Rivers’ replacement with the Davis band, Wayne Shorter. Later, in 1970, Rivers opened what became a very famous and successful musicians’ loft Studio Rivbea. Named after Sam and his artist wife of thirty years, Bea Rivers, this studio became the spot to hear the new generation of innovative black creative musicians such as then unknowns Arthur Blythe, David Murray, Henry Threadgill, Olu Dara, Frank Lowe, and the dynamos from Chicago’s AACM: Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Leo Smith, Leroy Jenkins and others.

The loft and Rivers became central figures in what the media dubbed “Loft Jazz” as many similar sites. for playing contemporary black creative music began to spring up. In 1976 many of the major artists in the movement were documented on record in a five-album series for Douglas Records that Rivers co-produced called Wildflowers. Now out of print, this series is a real collector’s item. As a concert and rehearsal space, Studio Rivbea was a fantastic place to hear live music without any distractions whatever. Its absence (Rivers closed it in 1980) is sorely felt.

Throughout the 1960s, 1970s and into this decade. Rivers has recorded some amazing music. In the mid 1960s, he did a series of classic recordings for Blue Note that featured a very fluid and dynamic style on tenor and a characteristically varied compositional approach. He also appeared as a sideman giving great performances on records led by Tony Williams, Larry Young and Andrew Hill. Rivers also performed and recorded with Cecil Taylor in the late 1960s, culminating in an exhilarating three-record set for wealthy European patron that was released in the U.S. as The Great Concert of Cecil Taylor, Rivers continued to play on and off with Taylor until 1973. After another brief stint with McCoy Tyner, Rivers really came into his own in the early 1970s.

It was during this phase that Rivers finally got an opportunity to record his orchestral music. Utilizing groups of between 10-25 pieces, Rivers extends the traditional big band concept through a distinctly melodic and rhythmic approach that relies on tonal density and textural richness to convey sound colors. There is a broad canvas of sounds to choose from in exploring the multidirectional movement of lines and rhythms. The first recorded evidence of this creative approach appears on a brilliant Rivers date for Impulse called Crystals from 1974. Since then Rivers has led outstanding large ensemble groups in various music festivals in the U.S., Europe, and Japan as well as continuing his unique uses of the small group idiom.

Ironically, despite the consistent high quality of Rivers’ work, he has only been able to make five recordings in America in the past eight years. Another glaring example of the music industry’s neglect of creative music. All of Rivers’ recent records (Duets 1 & 2 with the great bassist David Holland, Waves, Contrasts and his latest 1983 masterpiece for the Italian Black Saint label entitled Colours), are leading forces in contemporary creative music in the world today.

As Rivers says: “This music has developed at a very rapid pace over the last sixty years and has come to dominate the world music scene. The fine art music is jazz, now at its highest state, which we prefer to call creative music. We would like to change the name but the writers won’t allow it, they just keep saying ‘jazz.” I just let it go. It’s a category for me that covers all. I’ve played in symphony orchestras, blues bands, experimental groups, avant-garde groups, bebop groups, show bands; you name the music and I’ve pretty much done it. Saying that I’m a jazz musician means I play all kinds of music.”

On Friday, August 31 at 8pm you will hear more than versatility, exquisite technical control and prowess, or even creative values at work. You will hear passion, strength, tenderness and love. What else can you expect from music?

Sam Rivers

by Kofi Natambu

Source: African American National Biography

Born: El Reno, Oklahoma, United States

25 September 1923

Activity/Profession: Saxophonist, Composer / Arranger, Pianist, Jazz Musician

Multi-instrumentalist (tenor, soprano, and alto saxophones, piano, and flute), composer, arranger, and teacher was born Samuel Carthorne Rivers in El Reno, Oklahoma, to a family of musicians. Rivers's grandfather the Reverend Marshall Wiliam Taylor published a famous book of hymns and African American folk songs in 1882 entitled A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies. His parents, both college graduates from Chicago, played and toured with the Silvertone Quartet, a gospel group in which his father sang and his mother accompanied on piano. When he was still an infant, Rivers and his family moved to Chicago, where from the age of four Rivers sang in choirs directed by his mother. He joined his father on excursions to famous South Side venues—namely the Regal Theatre and Savoy Ballroom—to hear the top African American big bands of the day, from Duke Ellington and Count Basie to Earl “Fatha” Hines. During this time Rivers also learned piano and violin, dropping the latter instrument a few years later to concentrate exclusively on piano.

After Rivers's father died in an automobile accident in 1937, his mother took a teaching position at Shorter College in Little Rock, Arkansas. Rivers continued to develop his musical talent, playing trombone in the marching band at age eleven, and two years later picking up a saxophone, which he found more to his liking and on which he then concentrated exclusively. By the time he graduated from high school in Little Rock at age fifteen, Rivers had learned the trombone, soprano saxophone, and baritone horn.

As a student at Jarvis Christian College in Texas, Rivers started improvising on the saxophone while learning the classic Coleman Hawkins tenor saxophone interpretation and improvisation on “Body and Soul” from transcription. Soon Rivers was fervently studying other major saxophonists, like Lester Young and Chu Berry. In the mid-1940s he heard the revolutionary innovations of “bebop” pioneers Charlie “Yardbird” Parker and John “Dizzy” Gillespie while working as a navy clerk stationed near San Francisco, California. He felt he had received his calling to become a professional musician. The 1945 Gillespie and Parker recording “Blue and Boogie” particularly intrigued Rivers. Rivers spent his off-hours moonlighting on gigs with singer Jimmy Witherspoon and participating in Bay Area jam sessions.

Inspired to further his musical training, Rivers enrolled in the Boston Conservatory of Music in 1947, studying composition and theory, and also attended Boston University. He occasionally worked with other artistically ambitious jazz musicians, including Jaki Byard, Nat Pierce, Charlie Mariano, Gigi Gryce, Herb Pomeroy, and Alan Dawson. In 1952 Rivers dropped out of Boston University, suffering from illness for the next few years. He spent some time composing, but he remained relatively inactive as a performing musician. After his recovery Rivers moved to Florida in 1955, working in Miami with his brother, bass player Martin Rivers, and touring the South with rhythm and blues bands. A few years later, he returned to Boston, supporting himself by writing advertising jingles before rejoining the Herb Pomeroy orchestra (1960–1962) and forming a quartet in 1959 with pianist Hal Galper, bassist Henry Grimes, and a phenomenal thirteen-year-old drummer named Tony Williams.

Williams and Rivers would meet again in the summer of 1964 when the saxophonist, upon Williams's ardent recommendation, joined the Miles Davis Quintet, replacing tenor saxophonist George Coleman. Rivers toured and recorded with the quintet in Japan and as part of the World Jazz Festival. After his six-month tenure was over, he discovered that most of his musical peers in Boston were so busy teaching and performing on their own that they could no longer play with him. Undaunted, Rivers decided to move to Harlem and signed a recording contract with Blue Note, making his 1964 debut as a bandleader with the recording Fuchsia Swing Song, which demonstrated his movement from a post-bop conception into “free jazz” playing. The recording was well received by critics, and Rivers followed this success with another Blue Note session, Contours, with trumpeter Freddie Hubbard and pianist Herbie Hancock, which was much closer to mainstream jazz traditions. Rivers returned to free jazz in 1966 with Invocation.

Rivers grew increasingly interested in teaching, eventually conducting a workshop with his big band music at a Harlem junior high school. After touring and recording with the Cecil Taylor Unit Ensemble in 1969 (he played with the group from 1968 to 1973), and a six-month stint with pianist McCoy Tyner's group, in 1971 Rivers and his wife, Bea, opened Studio Rivbea, a performance and loft living space in lower Manhattan, for rehearsals and performances of his own original compositions as well as those of musicians interested in new, experimental work in the jazz tradition. One of the first major New York “loft spaces” to emerge during the 1970s, the studio became a nurturing ground and a live performance outlet for numerous improvisational musicians and composers in New York.

From 1972 to 1982, after working again with Miles Davis as well as Chick Corea's avant-garde ensemble Circle, Rivers performed and recorded regularly in duos, trios, quartets, quintets, and big bands, and he continued to foster and promote his studio. Throughout the 1980s Rivers composed for orchestral and smaller groups for Impulse Records and many minor labels. In 1991, after concluding four years of international touring with Dizzy Gillespie's quintet and big band, Rivers left New York to settle in Orlando, Florida, with his wife. While vacationing there, they had discovered a talented network of musicians working in theme parks and studios. Rivers formed his own record label (also called Rivbea) and wrote compositions for three Orlando-based ensembles: a sixteen-piece big band, an eleven-piece wind ensemble, and a trio, which was the orchestra's core rhythm section. He released two critically acclaimed albums for RCA, the 1999 Grammy Award–nominated Inspiration and 2000's Culmination. In the summer of 2000, Rivers released a double-CD on Rivbea, documenting his Orlando big band.

Further Reading:

Davis, Francis. “At 75, a Maverick Has a Big Band ‘Talking,’” New York Times, 10 Oct. 1999.

Gettelman, Parry. “Rivers Keeps It Fresh,” Orlando Sentinel Tribune, 19 November 1999.

Hazell, Ed. “Big-band Bop: Sam Rivers's Inspiration,” Boston Phoenix, 5 Aug. 1999

Rubien, David. “Sam Rivers Jazz Original Reappears,” San Francisco Chronicle, 7 Nov. 1993.

Sam Rivers Biography Timeline

Born: September 25, 1923 | Died: December 26, 2011 Instruments: Tenor and soprno saxophones, bass clarinet, piano, flute, percussion

Samuel Carthorne Rivers (born September 25, 1923, El Reno, Oklahoma) is a jazz musician and composer. He performs on soprano and tenor saxophones, bass clarinet, flute, and piano. Rivers was previously thought to have been born in 1930.

Rivers's father was a gospel musician who had sung with the Fisk Jubilee Singers and the Silverstone Quartet, exposing Rivers to music from an early age.

Rivers moved to Boston, Massachusetts in 1947, where he studied at the Boston Conservatory with Alan Hovhaness. He performed with Quincy Jones, Herb Pomeroy, Tadd Dameron and others.

In 1959 Rivers began performing with 13-year-old drummer Tony Williams, who later went on to have an impressive career. Rivers did a brief stint with Miles Davis's quintet in 1964, partly at Williams's recommendation. This quintet was recorded on a single album, Miles in Tokyo. Unfortunately, Rivers' playing style was too free to be compatible with Davis's music at this point, and he was soon replaced by Wayne Shorter. Rivers was signed by Blue Note Records, for whom he recorded four albums as leader and made several sideman appearances. Among noted sidemen on his own Blue Note Records were Jaki Byard who appears on Fuschia Swing Song, Herbie Hancock and Freddie Hubbard. He appeared on Blue Note recordings of Tony Williams, Andrew Hill and Larry Young.

Rivers's music is rooted in bebop, but he is an adventurous player, adept at free jazz. The first of his Blue Note albums, Fuchsia Swing Song, is widely regarded as a masterpiece of an approach sometimes called “inside-outside”. The performer frequently obliterates the explicit harmonic framework (”going outside”) but retains a hidden link so as to be able to return to it in a seamless fashion. Rivers brought the conceptual tools of bebop harmony to a new level in this process, united at all times with the ability to “tell a story” which Lester Young had.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/28/arts/music/sam-rivers-jazz-musician-dies-at-88.html

Sam Rivers, Jazz Artist of Loft Scene, Dies at 88

by NATE CHINEN

Sam Rivers, Jazz Artist of Loft Scene, Dies at 88

by NATE CHINEN

December 27, 2011

New York Times

Sam Rivers, an inexhaustibly creative saxophonist, flutist, bandleader and composer who cut his own decisive path through the jazz world, spearheading the 1970s loft scene in New York and later establishing a rugged outpost in Florida, died on Monday in Orlando, Fla. He was 88.

The cause was pneumonia, his daughter Monique Rivers Williams said.

With an approach to improvisation that was garrulous and uninhibited but firmly grounded in intellect and technique, Mr. Rivers was among the leading figures in the postwar jazz avant-garde. His sound on the tenor saxophone, his primary instrument, was distinctive: taut and throaty, slightly burred, dark-hued. He also had a recognizable voice on the soprano saxophone, flute and piano, and as a composer and arranger.

Music ran deep in his family. His grandfather Marshall W. Taylor published one of the first hymnals for black congregations after emancipation, “A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies,” in 1882. His mother, the former Lillian Taylor, was a pianist and choir director, and his father, Samuel Rivers, was a gospel singer. They were on tour with the Silvertone Quintet in El Reno, Okla., when Samuel Carthorne Rivers was born, on Sept. 25, 1923.

Growing up in Chicago and on the road, Mr. Rivers studied violin, piano and trombone. After his father had a debilitating accident in 1937, he moved with his mother to Little Rock, Ark., where he zeroed in on the tenor saxophone. Joining the Navy in the mid-’40s, he served for three years.

Mr. Rivers enrolled in the Boston Conservatory of Music in 1947 and later transferred to Boston University, where he majored in composition and briefly took up the viola and fell into the busy Boston jazz scene.

He made an important acquaintance in 1959: Tony Williams, a 13-year-old drummer who already sounded like an innovator. Together they delved into free improvisation, occasionally performing in museums alongside modernist and abstract paintings.

By 1964 Mr. Williams was working with the trumpeter Miles Davis and persuaded him to hire Mr. Rivers, who was with the bluesman T-Bone Walker at the time, for a summer tour. Mr. Rivers’s blustery playing with the Miles Davis Quintet, captured on the album “Miles in Tokyo,” suggested a provocative but imperfect fit. Wayne Shorter replaced him in the fall.

On a series of Blue Note recordings in the middle to late ’60s, beginning with Mr. Williams’s first album as a leader, “Life Time,” Mr. Rivers expressed his ideas more freely. He made four albums of his own for the label, the first of which — “Fuchsia Swing Song,” with Mr. Williams, the pianist Jaki Byard and the bassist Ron Carter, another Miles Davis sideman — is a landmark of experimental post-bop, with a free-flowing yet structurally sound style. “Beatrice,” a ballad from that album Mr. Rivers named after his wife, would become a jazz standard.

Beatrice Rivers died in 2005. In addition to his daughter Monique, Mr. Rivers is survived by two other daughters, Cindy Johnson and Traci Tozzi; a son, Dr. Samuel Rivers III; five grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren.

Mr. Rivers pushed further toward abstraction in the late ’60s, moving to New York and working as a sideman with the uncompromising pianists Andrew Hill and Cecil Taylor. In 1970 he and his wife opened Studio Rivbea, a noncommercial performance space, in their loft on Bond Street in the East Village. It served as an avant-garde hub through the end of the decade, anchoring what would be known as the loft scene.

The albums Mr. Rivers made for Impulse Records in the ’70s would further burnish his reputation in the avant-garde. After Studio Rivbea closed in 1979, Mr. Rivers continued to lead several groups, including a big band called the Rivbea Orchestra, a woodwind ensemble called Winds of Change and a virtuosic trio with the bassist Dave Holland and the drummer Barry Altschul. With the trio, Mr. Rivers often demonstrated his gift as a multi-instrumentalist, extemporizing fluidly on saxophone, piano and flute.

Mr. Rivers tacked toward more mainstream sensibilities from 1987 to 1991, when he worked extensively with an early influence, the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. While touring through Orlando with Gillespie in 1991, Mr. Rivers met some of the skilled musicians employed by the area’s theme parks, who persuaded him to move there and revive the Rivbea Orchestra. He lived most recently in nearby Apopka, Fla.

The music made by his band in the 1990s and beyond was as spirited and harmonically dense as anything in Mr. Rivers’s musical history. And the trio at its core — Mr. Rivers, the bassist Doug Mathews and the drummer Anthony Cole — also performed on its own, honing a dynamic versatility distinct from that of any other group in jazz.

Mr. Rivers’s late-career renaissance was confirmed by the critical response to “Inspiration” and “Culmination,” two albums he recorded for RCA in 1998 with a New York big band assembled by the alto saxophonist Steve Coleman. In 2000, Mr. Rivers led the Orlando iteration of the Rivbea Orchestra in a concert presented by Jazz at Lincoln Center. The next year he served as the fiery eminence on “Black Stars,” an acclaimed album by the 26-year-old pianist Jason Moran.

This year saw the release of “Sam Rivers and the Rivbea Orchestra — Trilogy” (Mosaic), a three-CD set featuring recordings from 2008 and 2009. His last performance was in October in DeLand, Fla.

In 2006. the Vision Festival, a nonprofit New York event aesthetically indebted to the loft scene, honored Mr. Rivers with a Sam Rivers Day program featuring both his bands. The names of two of the bustling pieces performed were, appropriately, “Flair” and “Spunk.”

http://jazztimes.com/articles/29221-sam-rivers-dies-at-88

Sam Rivers, an inexhaustibly creative saxophonist, flutist, bandleader and composer who cut his own decisive path through the jazz world, spearheading the 1970s loft scene in New York and later establishing a rugged outpost in Florida, died on Monday in Orlando, Fla. He was 88.

The cause was pneumonia, his daughter Monique Rivers Williams said.

With an approach to improvisation that was garrulous and uninhibited but firmly grounded in intellect and technique, Mr. Rivers was among the leading figures in the postwar jazz avant-garde. His sound on the tenor saxophone, his primary instrument, was distinctive: taut and throaty, slightly burred, dark-hued. He also had a recognizable voice on the soprano saxophone, flute and piano, and as a composer and arranger.

Music ran deep in his family. His grandfather Marshall W. Taylor published one of the first hymnals for black congregations after emancipation, “A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies,” in 1882. His mother, the former Lillian Taylor, was a pianist and choir director, and his father, Samuel Rivers, was a gospel singer. They were on tour with the Silvertone Quintet in El Reno, Okla., when Samuel Carthorne Rivers was born, on Sept. 25, 1923.

Growing up in Chicago and on the road, Mr. Rivers studied violin, piano and trombone. After his father had a debilitating accident in 1937, he moved with his mother to Little Rock, Ark., where he zeroed in on the tenor saxophone. Joining the Navy in the mid-’40s, he served for three years.

Mr. Rivers enrolled in the Boston Conservatory of Music in 1947 and later transferred to Boston University, where he majored in composition and briefly took up the viola and fell into the busy Boston jazz scene.

He made an important acquaintance in 1959: Tony Williams, a 13-year-old drummer who already sounded like an innovator. Together they delved into free improvisation, occasionally performing in museums alongside modernist and abstract paintings.

By 1964 Mr. Williams was working with the trumpeter Miles Davis and persuaded him to hire Mr. Rivers, who was with the bluesman T-Bone Walker at the time, for a summer tour. Mr. Rivers’s blustery playing with the Miles Davis Quintet, captured on the album “Miles in Tokyo,” suggested a provocative but imperfect fit. Wayne Shorter replaced him in the fall.

On a series of Blue Note recordings in the middle to late ’60s, beginning with Mr. Williams’s first album as a leader, “Life Time,” Mr. Rivers expressed his ideas more freely. He made four albums of his own for the label, the first of which — “Fuchsia Swing Song,” with Mr. Williams, the pianist Jaki Byard and the bassist Ron Carter, another Miles Davis sideman — is a landmark of experimental post-bop, with a free-flowing yet structurally sound style. “Beatrice,” a ballad from that album Mr. Rivers named after his wife, would become a jazz standard.

Beatrice Rivers died in 2005. In addition to his daughter Monique, Mr. Rivers is survived by two other daughters, Cindy Johnson and Traci Tozzi; a son, Dr. Samuel Rivers III; five grandchildren; and nine great-grandchildren.

Mr. Rivers pushed further toward abstraction in the late ’60s, moving to New York and working as a sideman with the uncompromising pianists Andrew Hill and Cecil Taylor. In 1970 he and his wife opened Studio Rivbea, a noncommercial performance space, in their loft on Bond Street in the East Village. It served as an avant-garde hub through the end of the decade, anchoring what would be known as the loft scene.

The albums Mr. Rivers made for Impulse Records in the ’70s would further burnish his reputation in the avant-garde. After Studio Rivbea closed in 1979, Mr. Rivers continued to lead several groups, including a big band called the Rivbea Orchestra, a woodwind ensemble called Winds of Change and a virtuosic trio with the bassist Dave Holland and the drummer Barry Altschul. With the trio, Mr. Rivers often demonstrated his gift as a multi-instrumentalist, extemporizing fluidly on saxophone, piano and flute.

Mr. Rivers tacked toward more mainstream sensibilities from 1987 to 1991, when he worked extensively with an early influence, the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. While touring through Orlando with Gillespie in 1991, Mr. Rivers met some of the skilled musicians employed by the area’s theme parks, who persuaded him to move there and revive the Rivbea Orchestra. He lived most recently in nearby Apopka, Fla.

The music made by his band in the 1990s and beyond was as spirited and harmonically dense as anything in Mr. Rivers’s musical history. And the trio at its core — Mr. Rivers, the bassist Doug Mathews and the drummer Anthony Cole — also performed on its own, honing a dynamic versatility distinct from that of any other group in jazz.

Mr. Rivers’s late-career renaissance was confirmed by the critical response to “Inspiration” and “Culmination,” two albums he recorded for RCA in 1998 with a New York big band assembled by the alto saxophonist Steve Coleman. In 2000, Mr. Rivers led the Orlando iteration of the Rivbea Orchestra in a concert presented by Jazz at Lincoln Center. The next year he served as the fiery eminence on “Black Stars,” an acclaimed album by the 26-year-old pianist Jason Moran.

This year saw the release of “Sam Rivers and the Rivbea Orchestra — Trilogy” (Mosaic), a three-CD set featuring recordings from 2008 and 2009. His last performance was in October in DeLand, Fla.

In 2006. the Vision Festival, a nonprofit New York event aesthetically indebted to the loft scene, honored Mr. Rivers with a Sam Rivers Day program featuring both his bands. The names of two of the bustling pieces performed were, appropriately, “Flair” and “Spunk.”

http://jazztimes.com/articles/29221-sam-rivers-dies-at-88

JazzTimes

12/27/11

Sam Rivers Dies at 88

Saxophonist and bandleader was a leading light of free jazz in the ’60s and ’70s

Sam Rivers, the multi-instrumentalist and bandleader who helped

to define free jazz but whose compositions also embraced form and

melody, died Dec. 26 in Orlando, Fla. He was 88. The cause of death, as

reported by the Orlando Sentinel, was pneumonia.

Born in Oklahoma in 1923, Rivers, like so many other future jazz

musicians, was raised on the music of the church, and his father was a

gospel singer with the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Rivers’ mother taught

music, and Rivers learned to play violin and piano as a child. The

family lived in Chicago and Little Rock, but in 1947, Rivers, who

ultimately played tenor and soprano saxophones (his primary

instruments), flute, bass clarinet, piano and harmonica, moved to

Boston, where he studied at the Boston Conservatory of Music and Boston

University.

Riku

Sam Rivers

Early in his career, in the 1950s, Rivers played in trumpeter Herb

Pomeroy’s band, alongside Quincy Jones and Jaki Byard. Rivers began to

lead his own bands in the late ’50s, one of which included the teenaged

drummer Tony Williams. Although he came up on bebop, Rivers took to

jazz's burgeoning avant-garde, aligning himself with the Jazz Composers’

Guild, along with such leading free-jazz figures as Cecil Taylor and

Archie Shepp.

Rivers joined Miles Davis’ quintet briefly in 1964, appearing on his Miles in Tokyo album, but was replaced by Wayne Shorter when Davis felt Rivers’ playing was too free. That same year, Rivers released his highly regarded first album as a leader, Fuschia Swing Song, on Blue Note. (It includes one of Rivers' best and most enduring compositions, "Beatrice.") During the ’60s, Rivers also kept busy as a sideman, playing on recordings (most on Blue Note) by Andrew Hill, Cecil Taylor, Bobby Hutcherson, Larry Young and Williams. Rivers ultimately recorded four albums for Blue Note as a leader, which featured such top players as Byard, Young, Hill, Freddie Hubbard and Herbie Hancock. Rivers’ '60s recordings, especially his debut and its follow-up, Contours, are essential listening: They showcase his remarkable ability to balance "inside" elements (the blues and hard bop) with the "outside" qualities (harmonic tension, dissonance) of the avant-garde.

Rivers signed with Impulse! Records in the ’70s, recording such highly regarded albums as Streams and Crystals. Rivers also made notable contributions to Dave Holland’s 1973 release Conference of the Birds, on ECM, which also included avant-garde pioneer Anthony Braxton. The drummer from that session, Barry Altschul, was, with Holland, part of a celebrated trio Rivers led in the '70s. In late 1975, Holland and Rivers recorded a series of duet sessions, released on two albums on the Improvising Artists label. In 1979, Holland was part of the quartet that recorded Rivers’ ECM album Contrasts. During that same decade, Rivers and his then-wife Beatrice ran a loft performance space (first in Harlem and then in lower Manhattan) called Studio Rivbea; Rivers also led a big band he called the Rivbea Orchestra.

Rivers continued to record and perform prolifically for the rest of his life, both as leader and sideman. In the late ’80s the diverse player worked for some time with Dizzy Gillespie’s United Nation Big Band. In 1999 and 2000 Rivers released a pair of albums on RCA with the Rivbea All-Star Orchestra and in 2001, at age 77, he contributed saxophone to pianist Jason Moran’s Blue Note album Black Stars.

In his final two decades Rivers settled in Orlando, where he continued to perform with his big band and a trio featuring bassist Doug Mathews. He continued to compose elaborate, ambitious work and record it with a new version of the Rivbea Orchestra (some of Rivers' musicians were students and teachers at local colleges, as well as players who made their livings performing at Disney World and other theme parks). Rivers composed more than 300 works during his career. This year Mosaic Select released Trilogy, a box set of recordings made by the Orlando group.

Just last year Rivers commented on his longevity. “I don’t know how to explain it, but at 87, I have greater musical powers than I did when I was 21,” he said in the liner notes for the Mosaic package. “These days all I do is practice and write. That’s as close to heaven as I can get, as a non-believer. There’s no such thing as retirement, anyway. Retirement? What is that? Who retires?”

Rivers joined Miles Davis’ quintet briefly in 1964, appearing on his Miles in Tokyo album, but was replaced by Wayne Shorter when Davis felt Rivers’ playing was too free. That same year, Rivers released his highly regarded first album as a leader, Fuschia Swing Song, on Blue Note. (It includes one of Rivers' best and most enduring compositions, "Beatrice.") During the ’60s, Rivers also kept busy as a sideman, playing on recordings (most on Blue Note) by Andrew Hill, Cecil Taylor, Bobby Hutcherson, Larry Young and Williams. Rivers ultimately recorded four albums for Blue Note as a leader, which featured such top players as Byard, Young, Hill, Freddie Hubbard and Herbie Hancock. Rivers’ '60s recordings, especially his debut and its follow-up, Contours, are essential listening: They showcase his remarkable ability to balance "inside" elements (the blues and hard bop) with the "outside" qualities (harmonic tension, dissonance) of the avant-garde.

Rivers signed with Impulse! Records in the ’70s, recording such highly regarded albums as Streams and Crystals. Rivers also made notable contributions to Dave Holland’s 1973 release Conference of the Birds, on ECM, which also included avant-garde pioneer Anthony Braxton. The drummer from that session, Barry Altschul, was, with Holland, part of a celebrated trio Rivers led in the '70s. In late 1975, Holland and Rivers recorded a series of duet sessions, released on two albums on the Improvising Artists label. In 1979, Holland was part of the quartet that recorded Rivers’ ECM album Contrasts. During that same decade, Rivers and his then-wife Beatrice ran a loft performance space (first in Harlem and then in lower Manhattan) called Studio Rivbea; Rivers also led a big band he called the Rivbea Orchestra.

Rivers continued to record and perform prolifically for the rest of his life, both as leader and sideman. In the late ’80s the diverse player worked for some time with Dizzy Gillespie’s United Nation Big Band. In 1999 and 2000 Rivers released a pair of albums on RCA with the Rivbea All-Star Orchestra and in 2001, at age 77, he contributed saxophone to pianist Jason Moran’s Blue Note album Black Stars.

In his final two decades Rivers settled in Orlando, where he continued to perform with his big band and a trio featuring bassist Doug Mathews. He continued to compose elaborate, ambitious work and record it with a new version of the Rivbea Orchestra (some of Rivers' musicians were students and teachers at local colleges, as well as players who made their livings performing at Disney World and other theme parks). Rivers composed more than 300 works during his career. This year Mosaic Select released Trilogy, a box set of recordings made by the Orlando group.

Just last year Rivers commented on his longevity. “I don’t know how to explain it, but at 87, I have greater musical powers than I did when I was 21,” he said in the liner notes for the Mosaic package. “These days all I do is practice and write. That’s as close to heaven as I can get, as a non-believer. There’s no such thing as retirement, anyway. Retirement? What is that? Who retires?”

Sam Rivers: Sax symbol blows on

Sam Rivers played with Charles Mingus, Miles Davis and Jimi

Hendrix. Keith Shadwick meets the energetic octogenarian

The Independent

Name a musician who has played in the bands of Miles Davis, T-Bone Walker, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Holland, BB King, Jimmy Witherspoon and Charles Mingus, hung out and jammed with everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Anthony Braxton and appeared as a soloist in concert with a symphony orchestra conducted by Seiji Ozawa. Oh, and by the way, he has written 30 symphonies of his own, as well as made a number of classic jazz albums in the past four decades. Today, he's something of a father figure to jazz radicals. It's 81-year-old Sam Rivers.

Name a musician who has played in the bands of Miles Davis, T-Bone Walker, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Holland, BB King, Jimmy Witherspoon and Charles Mingus, hung out and jammed with everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Anthony Braxton and appeared as a soloist in concert with a symphony orchestra conducted by Seiji Ozawa. Oh, and by the way, he has written 30 symphonies of his own, as well as made a number of classic jazz albums in the past four decades. Today, he's something of a father figure to jazz radicals. It's 81-year-old Sam Rivers.

Being in the presence of a man with the energy of someone 30 years his junior, such diverse and impressive achievements quickly make sense. The veteran saxophonist had been in London a couple of days and was spending much of his free time in between rehearsals, soundchecks and just getting around town developing compositional ideas. He has, he says, "too much music for me ever to record in my lifetime". I had to concur: I remember reading a liner note he wrote to one of his early large-ensemble 1970s albums where he identified some pieces as having been written back in the 1950s. He was already playing catch-up 30 years ago.

I asked if he considered himself a prolific composer. He stopped for a moment, obviously having never really thought about it, then gave a broad smile. "Prolific? Yes, that's it! I'm composing pretty much every day. I'm trying to finish a composition right now in my room. I don't need an instrument to compose. I can just work it all out in my head."

This, I recalled, was what people such as Benjamin Britten did. Britten used to write chamber works in his head for his own amusement during car journeys. "Yeah, that's right," said Rivers. "It's a thought process. It's the way you think. For me the piano limits that. I can't imagine writing some of my things by just working out at a piano. It's intellectual, a science." As opposed to Stravinsky, I suggested, who wrote everything on piano. He'd have been a bit stuck on tour. "Yes! And he wasn't much of a pianist either! But boy could he develop those ideas. Whoo!"

Given Rivers's extraordinary breadth and depth of knowledge in so many areas of music, I wondered what the background for it was. "Mine was the third generation of musicians in the Rivers family. I got my original musical education from my father, who was a violinist. My mother and father were both college graduates. So was my grandfather. I learned the viola. We were based in Chicago. Then I went to Boston to study theory and get my degree."

There he fell in with a large 1950s community of like-minded, ambitious musicians including Jaki Byard, Quincy Jones and Charlie Mariano. "The level of musicianship was very high, man," Rivers emphasised. "By day I was studying at the conservatory, playing viola, and at night I was playing saxophone in this club. Seven nights a week! People lived and breathed music."

One of the Boston people Rivers hit it off with in particular was teenage drum prodigy Tony Williams. Williams was knocking spots off the locals at the age of 13. At 17, in 1963, he was the rush of adrenalin behind Miles Davis. In 1964 Miles needed a saxophonist to work some international tour dates for him. Williams played Miles a tape of himself with Sam Rivers. "I was on the road with T-Bone Walker's band. Tony rang and said, 'Miles wants you to come and join the band, come right away.' So one week I was with T-Bone, the next with Miles."

I wondered if that felt weird. "No. I can play anybody's music. I enjoyed being with Miles. Most of the stuff we played was on the records, like Seven Steps to Heaven. Most jazz musicians like to play chord changes that are very simple so that they can improvise and every night's different. If the changes are hard, then you spend all your time trying to play the changes instead of trying to create! If the changes are simple and you can float, that's when you can express yourself."

Rivers remained on good terms with Miles after his stint came to an end in rather odd circumstances. "What nobody told me was that he and Art Blakey had already done a deal to have Wayne Shorter join Miles late in 1964, and I would go the other way. Swap over. Man! Why didn't they say? Anyway, I went with Andrew Hill's band instead."

Rivers went with the pianist/composer Andrew Hill because, along with lining Rivers up for the Davis band, Tony Williams had introduced the saxophonist to Blue Note's Alfred Lion by asking him to play on his first two albums for the label. By 1964 the man who'd made a star of Jimmy Smith was recording cutting-edge players such as Eric Dolphy, Joe Henderson, Andrew Hill and Herbie Hancock. He liked Rivers's highly individual approach and signed him. In the next three years Rivers would appear as a leader and sideman on a number of classic Blue Note recordings, not least a series with Andrew Hill.

Sam Rivers's gregariousness and industry led him to set up a loft space in New York in the late 1960s where he and other musicians could rehearse andexplore the outer limits of music. This would be a key development in creating the busy "loft jazz scene" that produced so many strong improvisers in the 1970s. It also spread Rivers's circle of musical acquaintance. Through percussionist Juma Sultan, who had jammed with John Coltrane and was by 1969 a close musical associate of Jimi Hendrix, the saxophonist got to jam with the guitar god many times.

Rivers derived great pleasure from playing with so many front-line stars, but it got to the stage that he wanted his own music to be out there in front of an audience. "I've got 30 symphonies of my own ready to go. I know the form and its disciplines, and I feel I've a little something to contribute."

I asked Sam if any of them had been performed yet. "No. I'm looking for an orchestra." BBC Proms programmers take note: there's a modern American master out there who'd love to have one of his 30 symphonies premiered at the next season. He's 81 and boy, is he ready.

http://pitchfork.com/news/44959-sam-rivers-jazz-musician-and-composer-rip/

Sam Rivers, Jazz Musician and Composer, R.I.P.

He was 88

Though his primary instruments were tenor and soprano saxophone, Rivers was a multi-instrumentalist who performed and recorded on flute and bass clarinet. Throughout his career, he never stuck to a single idiom or instrumental setting. Rivers began playing bebop but eagerly embraced the development of free jazz; he both recorded with small groups and composed for a big band.

Born into a musical family in El Reno, Oklahoma, Rivers worked as a sideman in the 1950s and 60s, and eventually joined Miles Davis' quintet for a brief period in 1964 before being replaced by Wayne Shorter. Blossoming as a bandleader and a sideman during the 60s, Rivers made records under his own name, including his highly regarded 1964 debut Fuchsia Swing Song, and also worked with jazz figures including pianists Andrew Hill and Cecil Taylor.

It was during the 70s, however, that Rivers arguably made his greatest impact. He established a performance space called Studio Rivbea inside the Manhattan loft he shared with his wife, Beatrice, and the couple's venue became a key hub for performance art and avant-garde jazz experimentation during the decade. Rivers eventually settled in Orlando, Florida, in part because the area is home to trained musicians employed by the Walt Disney Company, according to the Sentinel. There, he continued to write and perform. Check out video of Rivers and his band below.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/dec/30/sam-rivers

Sam Rivers obituary

Influential American jazz multi-instrumentalist who remained at the cutting edge

Sam Rivers in 1999. 'I have evolved into the avant garde whereas some

people have jumped into it with no history and no background,' he said.

Photograph: Mephisto/Rex

The multi-instrumentalist Sam Rivers, who has died aged 88,

was one of the last messengers from the 1940s bebop era and the classic

decades of jazz. Accomplished on tenor and soprano saxophones, flute,

piano and viola, he wanted only to remain at the sharp edge of

music-making. Rivers included Miles Davis, BB King and Wilson Pickett among

his employers, and made a lasting impact on those who worked with him,

heard him play or attended one of his influential music workshops.

Lean, bony and unflinchingly focused, Rivers looked in his earlier years like a walk-on performer in a spaghetti western. A sophisticated and theoretically advanced composer, teacher and large-scale orchestrator as well as a virtuoso performer, he became a key player (with his wife, Beatrice) on New York's dynamic Soho loft-jazz scene in the 1970s. Their Studio Rivbea was the movement's best-known establishment of the era. Rivers was associated with New York's dynamic Soho loft-jazz scene in the 1970s.

Photograph: Philippe Levy-Stab/Corbis

Like his saxophone contemporaries John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, he was a fearless mould-breaker and explorer of new forms who was nonetheless profoundly influenced by that most fundamental of black American musical forms, the blues. He told the Guardian in 1981 that it was harder to play the blues well than the most technically demanding contemporary music, and a sense of the continuity of jazz and blues pervaded everything he played, however radical.

Rivers directed and worked in jazz ensembles of all sizes, but his impact was rarely more telling than when his majestically hoarse-toned tenor saxophone was accompanied only by bass and drums (the bassist Dave Holland was a particularly congenial partner), and he would improvise fast and sinewy long-lined melodies, informed by modern classical music as well as jazz, for extended stretches without cliche or repetition. "I have evolved into the avant garde whereas some people have jumped into it with no history and no background," he said. Fiercely independent and disciplined, Rivers assiduously studied others in order to find his own path through the spaces between them.

He was born in El Reno, Oklahoma. His father, Samuel, sang spirituals with a travelling gospel group called the Silvertone Quartet. His pianist mother, Lillian, was the group's accordionist. Sam's grandfather Marshall Taylor was a church minister and musician who had published the pioneering work A Collection of Revival Hymns and Plantation Melodies for black congregations in 1882. Rivers performing in 2003.

Photograph: Frans Schellekens/Redferns

Rivers studied the piano as a child but switched to the saxophone in his early teens. He moved to Arkansas, served in the US navy and then attended the Boston Conservatory from 1947 to 1952. Through the 50s and 60s, he performed with many of the biggest names in jazz. He appeared on Davis's Miles in Tokyo album in 1964 and soon afterwards made his leadership debut on the Blue Note label with the innovative Fuchsia Swing Song. The rhythm section was Davis's own inspirational pairing of the bassist Ron Carter and the drummer Tony Williams. At this point, Rivers was steering a course between an earthy and swinging hard bop style and a looser approach employing a more personal harmonic language. Working with the pianist Cecil Taylor later in the decade accelerated his progress towards his own perspectives on both improvised and composed music.

Rivers recorded for the adventurous Impulse! company and various European labels in the 1970s, establishing increasingly fruitful relationships between complex, suite-like compositions and improvisation. He displayed growing diversity on tenor and soprano saxophones and flute, ranging from unaccompanied solo performances to big bands. The Rivbea Orchestra continued after its namesake studio closed in 1979, and from the early 80s Rivers led a woodwind ensemble without a rhythm section that included the avant-funk sax star Steve Coleman in its lineup. Between 1987 and 1991 he often performed with Dizzy Gillespie, and it was on tour with Gillespie in Florida in 1991 that he met a group of jazz-devoted musicians from Walt Disney World who knew his earlier work and invited him to reconvene the Rivbea band in Orlando.

Rivers, the bassist Doug Matthews and the drummer Anthony Cole were the core of the new band, and they created some of the most powerful and original music of Rivers' life, both in the big ensemble and as a standalone trio. Rivers released the landmark solo recording Portrait in 1997 (on which he played the piano and all the reeds instruments, and also sang); participated in a memorable duo session with the German pianist Alex von Schlippenbach; and fronted a big band assembled by Coleman for the albums Inspiration (1999) and Culmination (2000). In 2001 he took a trenchantly concise saxophone role on the young pianist Jason Moran's album Black Stars, and in 2006 he performed at a Sam Rivers Day as part of New York's Vision festival.

Beatrice died in 2005. Rivers is survived by his daughters, Monique, Cindy and Traci; his son, Samuel; five grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

• Samuel Carthorne Rivers, jazz musician, born 25 September 1923; died 26 December 2011

Lean, bony and unflinchingly focused, Rivers looked in his earlier years like a walk-on performer in a spaghetti western. A sophisticated and theoretically advanced composer, teacher and large-scale orchestrator as well as a virtuoso performer, he became a key player (with his wife, Beatrice) on New York's dynamic Soho loft-jazz scene in the 1970s. Their Studio Rivbea was the movement's best-known establishment of the era. Rivers was associated with New York's dynamic Soho loft-jazz scene in the 1970s.

Photograph: Philippe Levy-Stab/Corbis

Like his saxophone contemporaries John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, he was a fearless mould-breaker and explorer of new forms who was nonetheless profoundly influenced by that most fundamental of black American musical forms, the blues. He told the Guardian in 1981 that it was harder to play the blues well than the most technically demanding contemporary music, and a sense of the continuity of jazz and blues pervaded everything he played, however radical.

Rivers directed and worked in jazz ensembles of all sizes, but his impact was rarely more telling than when his majestically hoarse-toned tenor saxophone was accompanied only by bass and drums (the bassist Dave Holland was a particularly congenial partner), and he would improvise fast and sinewy long-lined melodies, informed by modern classical music as well as jazz, for extended stretches without cliche or repetition. "I have evolved into the avant garde whereas some people have jumped into it with no history and no background," he said. Fiercely independent and disciplined, Rivers assiduously studied others in order to find his own path through the spaces between them.