AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2016

VOLUME TWO NUMBER THREE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LEO SMITH

March 26-April 1

AHMAD JAMAL

April 2-8

DIONNE WARWICK

April 9-15

LEE MORGAN

April 16-22

BILL DIXON

April 23-29

SAM COOKE

April 30-May 6

MUHAL RICHARD ABRAMS

May 7-13

BILLY HARPER

May 14-20

SISTER ROSETTA THARPE

May 21-27

QUINCY JONES

May 28-June 3

BESSIE SMITH

June 4-10

ROBERT JOHNSON

June 11-17

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/robert-johnson-mn0000832288/biography

Robert Johnson

(1911-1938)

In the mid-'60s, Columbia Records released King of the Delta Blues Singers, the first compilation of Johnson's music and one of the earliest collections of pure country blues. Rife with liner notes full of romantic speculation, little in the way of hard information and a painting standing for a picture, this for years was the world's sole introduction to the music and the legend, doing much to promote both. A second volume -- collecting up the other master takes and issuing a few of the alternates -- was released in the '70s, giving fans a first-hand listen to music that had been only circulated through bootleg tapes and albums or cover versions by English rock stars. Finally in 1990 -- after years of litigation -- a complete two-CD box set was released with every scrap of Johnson material known to exist plus the holy grail of the blues; the publishing of the only two known photographs of the man himself. Columbia's parent company, Sony, was hoping that sales would maybe hit 20,000. The box set went on to sell over a million units, the first blues recordings ever to do so.

During his brief career, Johnson traveled around, playing wherever he could. The acclaim for Johnson's work is based on the 29 songs that he wrote and recorded in Dallas and San Antonio from 1936 to 1937. These include "I Believe I'll Dust My Broom" and "Sweet Home Chicago," which has become a blues standard. His songs have been recorded by Muddy Waters, Elmore James, the Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton.

But much of Johnson's life is shrouded in mystery. Part of the lasting mythology around him is a story of how he gained his musical talents by making a bargain with the devil: Son House, a famed blues musician and a contemporary of Johnson, claimed after Johnson achieved fame that the musician had previously been a decent harmonica player, but a terrible guitarist—that is, until Johnson disappeared for a few weeks in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Legend has it that Johnson took his guitar to the crossroads of Highways 49 and 61, where he made a deal with the devil, who retuned his guitar in exchange for his soul.

Strangely enough, Johnson returned with an impressive technique and, eventually, gained renown as a master of the blues. While his reported "deal with the devil" may be unlikely, it is true that Johnson died at an early age.

Robert Johnson stamp (Photo: via The Robert Johnson Blues Foundation)

http://www.npr.org/2011/05/07/136063911/robert-johnson-at-100-still-dispelling-myths

Sunday marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Robert Johnson. Although he recorded just 29 songs, the bluesman had a huge influence on guitarists such as Eric Clapton and Keith Richards.

Johnson is one of the most studied of all country blues musicians, and

he's been the subject of many books, films and essays. But the

mythology surrounding his life just won't go away.

Sunday marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Robert Johnson. Although he recorded just 29 songs, the bluesman had a huge influence on guitarists such as Eric Clapton and Keith Richards.

Johnson is one of the most studied of all country blues musicians, and

he's been the subject of many books, films and essays. But the

mythology surrounding his life just won't go away.

If you know anything about Johnson, chances are it's the story that he sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads in exchange for his musical talent. That legend reached a mainstream audience with the 1986 movie Crossroads, starring Joe Seneca and Ralph Macchio.

But according to folklorist Barry Lee Pearson, it didn't happen.

"The popular mythology has him as a total loner," Pearson says, "and kind of lived this life in regret as a repayment for his alleged sin of making a contract with Old Scratch."

Pearson, a professor at the University of Maryland and the co-author of the book Robert Johnson: Lost and Found, says none of it is true. In the absence of any real biographical information, Pearson says early blues writers got a little carried away.

"Everybody was so anxious to make this devil story true that they've been working on finding little details that can corroborate it," he says.

Here is what we do know about Robert Johnson. He said he was born in Mississippi on May 8, 1911, and grew up on a plantation in the Delta. As a young man, he was more interested in music than farming: He'd hound the older blues musicians for a chance to play. In an interview included in the 1997 documentary Can't You Hear the Wind Howl, Son House recalls that the young Johnson would annoy audiences with his lousy guitar playing.

"Folks they come and say, 'Why don't you go out and make that boy put that thing down? He running us crazy,' " House said. "Finally he left. He run off from his mother and father, and went over in Arkansas some place or other."

When Johnson came back from Arkansas six months later, he'd mastered the guitar. That's where the rumors about his deal with the devil came from, but Johnson acknowledged studying with a human teacher while he was gone. After that, Johnson worked as a traveling musician, playing on street corners and in juke joints, mostly in Mississippi. And in 1936, he got a chance to record in Texas.

"Terraplane Blues" was a minor hit, and he was invited back for a second recording session. Johnson died a year later at age 27, under mysterious circumstances. Some think he was poisoned, although a note on the back of his death certificate says the cause was syphilis.

In any case, the timing was tragic. Legendary Columbia Records talent scout John Hammond wanted to book Johnson at Carnegie Hall for the landmark "Spirituals to Swing" concert in 1938. Hammond was also the driving force behind the first LP reissue of Johnson's music in 1961. At the time, Johnson was so obscure that Columbia didn't even have a picture of him to put on the cover. The LP was produced by Frank Driggs, who also wrote the liner notes.

"If you read the liner notes," Driggs says, "you see next to nothing. 'Cause I just created a thing out of whole cloth when I wrote the notes. Because there really was very little known about the guy."

Up Against The Wall

That LP, King of the Delta Blues Singers, introduced Johnson's music to a new generation of young, mainly white blues fans, including Eric Clapton, as the rock legend told NPR in 2004.

"It was on Columbia and it had, like, some pretty interesting sleeve notes on it about the fact that these were the only sides he had cut, and that they'd done it in a hotel room, and when he was auditioning for the sessions that he was so shy, he had to play facing into the corner of the room," Clapton says. "I mean, I immediately identified with that, because I was paralyzed with shyness as a kid."

But there may be another reason why Johnson recorded facing the wall. Elijah Wald is a musician and the author of the book Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. He says there were pre-war blues musicians who played guitar better than Johnson, as well as musicians who sang better. But Wald says that, unlike most of them, Johnson learned to play from listening to radio and records.

"Robert Johnson certainly was very conscious of what a hit record sounded like," Wald says. "If you listen to something like 'Come on in My Kitchen,' he's singing very quietly, and he actually has a moment when he says, 'Can't you hear the wind blowin'.' He whispers it and then plays this very quiet riff. That never would have worked on a street corner or a Mississippi juke joint, but it sounds great on records."

Sound is one of the main things that distinguishes Johnson's sides from other records of the time. By facing the wall, Wald says Johnson might have made his vocals sound better to a later generation accustomed to high fidelity. It doesn't hurt that the original masters of his recordings survived, too. But what really set Johnson apart from his peers was all of the mythology that grew up around him, especially the part about the devil. Many of Johnson's friends, including Johnny Shines in Can't You Hear the Wind Howl, dismissed it as false.

"No," Shimes says, "he never told me that lie. If he would've, I would've called him a liar right to his face. You have no control over your soul. How you gonna do anything with your soul?"

But the myth about Johnson persists, in part because it helps sell records. Steve Berkowitz is a producer at Sony Legacy, which is reissuing Johnson's music again, this time in a new centennial edition.

"That was always the heart and soul of the marketing plan," Berkowitz says. "We always knew the music was great. But a guy sells his soul to the devil at midnight down at the crossroads, comes back and plays the hell out of the guitar, and then he dies. I mean, it's a spectacular story."

And there wouldn't be any harm in that, Wald says, except that the legend tends to overshadow the real Robert Johnson.

"To just say that he went to the crossroads in the dead of night, first of all means we're not getting what happened. And second of all, it's kind of insulting," Wald says. "It's kind of implying that, unlike us who do this serious work to understand music, these old black blues guys just went and sold their soul to the devil."

If it were really that easy, Wald says, the devil would own the souls of every teenage boy and girl in America.

In June 2005,

Steven “Zeke” Schein was killing time on his home computer when he

logged on to eBay and typed “old guitar” into the auction site’s search

engine. Classically trained as a guitarist, Schein had turned his

longtime passion for the instrument into a profession when, in 1989, he

had joined the sales force at Matt Umanov Guitars, in Manhattan’s West

Village. In the more than 15 years that Schein had worked there, he had

cultivated a regular clientele that included Patti Smith, ZZ Top’s Billy

Gibbons, and record producers Daniel Lanois and John Leventhal; he had

also sold guitars to Bob Dylan, Pete Townshend, Brad Pitt, and Johnny

Depp, among other celebrities. His job had also exposed him to the

painstaking, detail-oriented detective work that often goes into

identifying and authenticating vintage guitars. Even when the make,

model, and serial number of an instrument are apparent, pinpointing its

age and value sometimes requires scrutinizing the idiosyncrasies of its

construction. The design of the instrument’s tailpiece, its headstock,

the number of frets embedded in its neck, its paint job or finish—all

could be identifying factors.

Schein enjoyed this aspect of the business, and when he had nothing better to do, he would sometimes log on to eBay to test his knowledge against the sellers who were advertising vintage guitars on the Web site. At the very least, he found it amusing that some people had no idea what they were selling.

As he pored over the mass of texts and thumbnail photos that the eBay search engine had pulled up on that day in 2005, one strangely worded listing caught Schein’s eye. It read, “Old Snapshot Blues Guitar B.B. King???” He clicked on the link, then took in the sepia-toned image that opened on his monitor. Two young black men stared back at Schein from what seemed to be another time. They stood against a plain backdrop wearing snazzy suits, hats, and self-conscious smiles. The man on the left held a guitar stiffly against his lean frame.

Neither man looked like B. B. King, but as Schein studied the figure with the guitar, noticing in particular the extraordinary length of his fingers and the way his left eye seemed narrower and out of sync with his right, it occurred to him that he had stumbled across something significant and rare.

If there was one thing that Schein was as passionate about as guitars, it was the blues, particularly the Delta blues, that acoustic, guitar-driven form of country blues that started in the Mississippi Delta and thrived on records from the late 1920s to almost 1940. Not long after he’d begun working at Matt Umanov, Schein’s customers and co-workers had turned him on to this powerful music form, and, once hooked, he had studied the genre—its music and its history—with the same obsessive attention to detail that he brought to his work. And the longer Schein looked at the photograph on his computer monitor, the more convinced he became that it depicted one of the most mysterious and mythologized blues artists produced by the Delta: the guitarist, singer, and songwriter whom Eric Clapton once anointed “the most important blues musician who ever lived.”

That’s not B. B. King, Schein said to himself. Because it’s Robert Johnson.

If his hunch was correct, he’d made quite a find. Johnson is the Delta-blues guitarist who on one dark Mississippi night “went to the crossroad,” as he wrote in one of his most famous songs, to barter his soul to the Devil for otherworldly talent. At least that’s how the legend that’s become ingrained in popular culture has it. (In the song, “Cross Road Blues,” Johnson is actually pleading with God for mercy, not bargaining with the Devil.) A short life, a death under murky circumstances, and a body of recorded work consisting of but 29 songs only added to that legend. So did the preternatural quality of his guitar playing, the bone-deep sadness of some of his music and lyrics, the haunting quaver of his smooth, high voice, and the dark symbolism of his songs. In some respects, you could say that Johnson is the James Dean of the blues, an artist whose tragically foreshortened life and small if brilliant body of work make him a figure of great romantic allure. This was especially true in the 60s and early 70s, when little was known about Johnson, and his music was being taken up by the likes of Clapton, the Rolling Stones, and Led Zeppelin. By the early 1990s, 50 years after his death, he was a platinum-selling artist, and since then he has influenced a whole new generation of guitar players, among them John Mayer and Jack White.

Defiant and Haunted

While popular culture loves a mystery, its most obsessive fans abhor a vacuum; thus there are vast archives of bootleg album outtakes and Ph.D. dissertations on forgotten record labels. The lives of poor, itinerant black musicians in the rural South of the late 1920s and 30s aren’t the most well-documented of lives, but over the past 35 years, blues researchers and historians have done a pretty good job of revealing the man behind the Johnson myth, from his birth in Hazlehurst, Mississippi (May 8, 1911, is often cited as Johnson’s birth date, though his birth certificate has yet to be found), to his death, which probably occurred in the Baptist Town section of Greenwood, Mississippi, in 1938. According to Elijah Wald’s 2004 book, Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues, there is currently more information available about Johnson “than about almost any of the bigger blues stars of his day.” Still, in the field of Johnson research, attempting to separate fact from fiction from politics can be maddening. As Wald writes, “So much research has been done [on Johnson] that I have to assume the overall picture is fairly accurate. Still, this picture has been pieced together from so many tattered and flimsy scraps that almost any one of them must to some extent be taken on faith.”

The biggest hole in this patchwork is the one thing that would establish Johnson’s humanity in a society hooked on visual media: photographs. In the years since he died, only two known photographs of Johnson have ever been seen by the public. The first of those images is believed to have been taken in the early 1930s and has been described as Johnson’s “photo-booth self-portrait.” The size of a postage stamp, it provided the public its first real glimpse of Johnson when it was published, more than a dozen years after it was found, in Rolling Stone magazine in 1986, the year that Johnson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. In the photo, Johnson, wearing a button-down shirt with thin suspenders and holding a guitar, stares at the lens with eyes that look both defiant and haunted. A cigarette dangles from his lips, and although the guitar is only partially visible, his long left-hand fingers can be seen forming an indeterminate chord on the guitar’s neck.

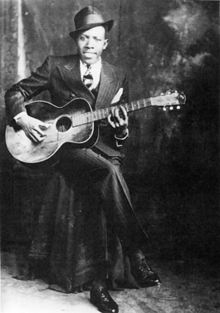

If the photo-booth shot was a low-budget affair, the second image had production values. Taken by Hooks Bros., a photographic studio located in Memphis, it shows Johnson once again holding his guitar as he sits cross-legged on what appears to be a tapestry-covered stool. But this time, the bluesman is resplendent in a pin-striped suit, a striped tie, shiny dress shoes, and a narrow-brimmed fedora cocked over his right eye. He is smiling in the photo, but his eyes make him look like a deer caught in the headlights.

The Hooks Bros. photo was first widely seen in 1990, when it was featured on the cover of Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings, the two-CD boxed set issued by Columbia Records that collected what, at the time, was Johnson’s entire surviving canon. The set sold more than a million copies, establishing Johnson as the biggest-selling pre-war blues artist of all time.

Schein had bought the boxed set about a year after it came out and had spent numerous hours immersing himself in the music and studying Johnson’s life story. The crossroads legend held little magic for him. After all, Schein dealt with professional musicians every day and knew plenty of talented guitarists and songwriters who toiled in obscurity or struggled for recognition, and even some who had died just as their careers were taking off. For Schein, Johnson’s appeal wasn’t any aura of mystery but rather his humanness. Born illegitimate, Johnson had lived a life freighted with alienation and misfortune. In 1930 he lost his first wife and their baby in childbirth, and yet, in the wake of this tragedy, Johnson managed to become a guitar virtuoso who still influences musicians today. He was “one guy with a guitar standing to [make] his peace,” Schein says. As far as he was concerned, Johnson’s story needed no embellishment.

With the eBay photo still on his computer monitor, Schein dug up his copy of the Johnson boxed set and took another look. Not only was he more confident than ever that he had found a photo of Robert Johnson, he had a hunch who the other man in the photo was, too: Johnny Shines, a respected Delta-blues artist in his own right, and one of the handful of musicians who, in the early 1930s and again in the months before Johnson’s death, had traveled with him from town to town to look for gigs or stand on busy street corners and engage in a competitive practice known as “cuttin’ heads,” whereby one blues musician tries to draw away the crowd (and their money) gathered around another musician by standing on a nearby corner and outplaying him.

Shines had died in 1992. His picture was included in the boxed-set booklet, and Schein saw a resemblance; if both of his hunches were right, then the photo was even more of a find. At that point, Schein became possessed of two thoughts: One was “to hold the photo in my hands,” he says. The other was “to protect it.”

Because the image had just recently been listed, by a New York–based antiques dealer, bidding was still at a reasonable $25, but Schein guessed that the ending bid was going to be many times that initial figure. He had just sold a beautiful 1920s Stella acoustic guitar—a favorite among the old country-blues musicians—and when he added together the money he’d gotten for that and some extra cash on hand, he came up with a budget of $3,100. If someone spends more than that, he figured, the bidder will also know it’s a photo of Robert Johnson, so it will be protected.

A co-worker of Schein’s set up a computer “snipe” program that automatically bid on the picture up to the specified limit, and Schein held his breath. Approximately $2,200 later, he held the photo in his hands. What had he gotten for his money? An extremely fragile, three-inch-by-four-inch photo that bore no identifying marks that could be traced to a photographer’s studio, no date stamp that could establish when the picture had been taken, no provenance whatsoever save for a note from the seller saying he’d purchased the photo in Atlanta. Schein was still convinced that he had found and purchased a photo of Robert Johnson and Johnny Shines. The question was, could he convince anyone else? And, if he could, would he then be able to navigate the complicated and treacherous legal minefield surrounding Johnson’s lucrative and much disputed estate?

The Right to Play the Blues

The story of Robert Johnson is usually presented as a Faustian bargain, but it is really a tale of possession. Johnson was the product of an affair his mother, Julia Dodds, had with a plantation worker. Johnson had unusually long fingers and a bad left eye (that has been attributed to a cataract), and by the time he had recorded his canon, he had earned the right to sing and play the blues.

His youth was spent moving between homes in Memphis and Robinsonville, Mississippi, 30 miles south of Memphis, where he lived with his mother and her second husband on a plantation. There he was known for his interest in guitar and his reluctance to work the fields.

It was in the aftermath of his wife’s and child’s deaths—Johnson was approximately 19 at the time—that his musical education is believed to have begun in earnest. In 1930 the ferocious blues singer Son House had moved to Robinsonville to begin a fruitful musical partnership with the guitar ace Willie Brown, and Johnson became a regular presence at their performances, although the two elder bluesmen perceived him as a nuisance. House’s recollection of Johnson—as told to folklorist Julius Lester in 1965—was of a “little boy” who would commandeer either his or Brown’s guitar during their breaks and irritate the audience with his marginal skills. Perhaps Johnson sensed, too, that he was not ready for the stage, because around this time he moved back to the Hazlehurst area, his birthplace, where he began an apprenticeship with a blues guitarist named Ike Zimmerman (the spelling of his name is disputed) which would transform Johnson into the virtuoso he is known as today.

That Robert Johnson is remembered as a guitarist who could play almost any song after hearing it just once on the radio; a singer whose repertoire, like those of most itinerant bluesmen, included numbers made famous by Bing Crosby, Irish standards, and even polkas, in addition to his own songs; a performer whose travels took him as far north as New York City and even Canada in search of an audience; and an artist who could move an audience to tears and then disappear into the crowd as if he had never played at all.

Clearly, Johnson was a man of some ambition, and in November of 1936 he traveled to San Antonio, Texas, for the first of two recording sessions for the American Record Corporation. Once in the makeshift studio, he played facing a corner, with his back to the technicians and other musicians who had come to record, a move that has been variously interpreted as shyness, an attempt to prevent other guitarists from seeing his unusual playing style, or a street-savvy technique for getting the most sound out of his acoustic guitar. Whatever the case, Johnson recorded approximately 16 songs over three days, most of them in two or three takes. One of those tunes, “Terraplane Blues,” a double-entendre-laden number, was issued as a 78-r.p.m. single on the Vocalion label and became a modest regional hit, selling approximately 5,000 copies. As a result, Johnson was invited back to Texas, this time, in June 1937, to Dallas, where he recorded another 13 tracks, but no more hits.

A little more than a year later, Johnson would be dead—and probably destined for obscurity had his music not already gotten the attention of a record producer who would exert a huge impact on popular music in the 20th century. By the time John H. Hammond Jr. came across Johnson’s records, he had persuaded Benny Goodman to integrate his band, discovered a young Billie Holiday in Harlem, and recorded Count Basie, but he was just getting started. As a talent scout for Columbia Records in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, Hammond would discover Aretha Franklin and sign Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Bruce Springsteen, and Stevie Ray Vaughan to the label.

Hammond’s role in Johnson’s legacy is pivotal. He first championed Johnson in print in 1937 when, writing under a pseudonym for the left-wing publication New Masses, he asserted that “Johnson makes Leadbelly look like an accomplished poseur.” Then, in 1938, Hammond sought to feature Johnson in a concert he was producing at Carnegie Hall that December called “From Spirituals to Swing.” He sent an emissary into the South to track down Johnson and bring him back to New York. But as the day of the show approached, Hammond learned that Johnson was dead—possibly murdered. On the night of the concert, Big Bill Broonzy took Johnson’s place, but Hammond memorialized the late Delta artist by playing two recordings of his songs for the Carnegie Hall audience.

More than 20 years later, Hammond would expose Johnson’s music to a whole new generation of listeners. Columbia now controlled Johnson’s recordings, and in 1961, Hammond oversaw the release of King of the Delta Blues Singers, the first album-length collection of Johnson’s music, which helped spark a blues revival in America. According to the album’s producer, Frank Driggs, it sold approximately 10,000 copies upon its initial release—impressive for an obscure, dead, vernacular performer.

“The Music Almost Repelled Me”

Not long before the album became available to the public, Hammond had given a young Bob Dylan an early acetate copy of the LP. Near the end of his 2004 memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan recounts the rather intense effect King of the Delta Blues Singers had on him. If he hadn’t heard the album at such an early, formative stage in his career, Dylan writes, “there probably would have been hundreds of lines of mine that would have been shut down—that I wouldn’t have felt free or upraised enough to write.”

King of the Delta Blues Singers had an arguably larger impact across the Atlantic in Britain, where a new generation of rock ’n’ rollers were learning their chops and finding their influences. One of them was a shy, alienated teenager named Eric Clapton, who was given the Johnson album by one of his early bandmates. “At first the music almost repelled me, it was so intense and this man made no attempt to sugarcoat what he was trying to say, or play,” Clapton writes in his recently published memoir, Clapton: The Autobiography.

The chance of this music’s having such an immediate and visceral effect on an aspiring rock star today is, frankly, pretty slim. To ears accustomed to modern, computer-generated effects that can make almost anyone sound like a guitar god or a vocal powerhouse, Johnson’s music can sound thin and primitive at first spin, even though it’s remarkably complex and polished for its time. As Clapton explains in his autobiography, Johnson employed a fingerpicking style that had him “simultaneously playing a disjointed bass line on the low strings, rhythm on the middle strings, and lead on the treble strings while singing at the same time.” Occasionally, Johnson worked in some bottle-slide playing, too, which involves placing a small glass bottle or sleeve over the left pinkie, then sliding it up and down the guitar’s neck to create the pitch-bending wail that is a signature of the blues. Even accomplished guitarists can have a hard time re-creating Johnson’s sound, let alone mastering it. Says Dave Rubin, an author for the music publisher Hal Leonard Corporation who led the team of musicians who transcribed Johnson’s songs for the guitar instructional Robert Johnson: The New Transcriptions, “When you get to ‘Crossroads’ and ‘Preachin’ Blues’—oh my God, forget it. It sounds like three guys playing.”

Johnson’s guitar chops were just one part of the equation, however. For a blues singer, he was more of a crooner than a croaker, and his voice sometimes had a quaver that could sound haunted or seductive. There was also an urgency to Johnson’s singing that made him sound “like he’s about five minutes away from the electric chair,” Driggs says. Lyrics such as “She got a mortgage on my body now, a lien on my soul,” from “Traveling Riverside Blues,” could also have a devastating poetic economy. In Chronicles, Dylan recounts writing Johnson’s words down on scraps of paper to examine their structure and finding “big-ass truths wrapped in the hard shell of nonsensical abstraction—themes that flew through the air with the greatest of ease.” (Dylan could have been talking about himself.) He doesn’t put much stock in criticism that is often leveled at the blues artist: that Johnson’s work is derivative. In Chronicles, Dylan plays King of the Delta Blues Singers for his friend Dave Van Ronk, the respected folksinger known as the Mayor of MacDougal Street, but Van Ronk mostly hears a musician mimicking his predecessors. “He didn’t think Johnson was very original. I knew what he meant, but I thought just the opposite. I thought Johnson was as original as could be, didn’t think him or his songs could be compared to anything.”

What Dylan

understands about Johnson is that, while his influences are easily

divined, in all but a few cases, every guitar lick, vocal technique, or

lyrical flourish that he borrows or steals he makes his own. For

example, Rubin explains, while Johnnie Temple’s “Lead Pencil Blues” was

the first recorded example of the “cut boogie pattern”—the chugging,

trainlike guitar line that’s a staple of basic rock ’n’ roll—it’s

Johnson’s harder, more propulsive version, found, for example, on “Sweet

Home Chicago,” that other guitarists began to adopt, from Elmore James

to Chuck Berry and beyond.

“To me, he was the synthesis of his generation,” says blues guitarist and singer-songwriter John P. Hammond, whose father was the John Hammond who signed Dylan and oversaw the release of King of the Delta Blues Singers. Hammond fils discovered Robert Johnson independently of his father, in the late 1950s, when he heard one of the bluesman’s songs on a Folkways album compilation. “He was my inspiration to want to play,” Hammond says of Johnson. Hammond joined a number of artists in the 60s who were influenced by Johnson, covering his music on their albums or in their concerts, or both. The Rolling Stones reworked Johnson’s “Love in Vain” for their now classic 1969 album Let It Bleed (although they credited the writer as “Woody Payne,” presumably to avoid copyright problems), and that same year Led Zeppelin’s second album included “The Lemon Song,” a track that owed much to Howlin’ Wolf but also took part of its lyrics—“You can squeeze my lemon ’til the juice run down my leg”—from Johnson’s “Traveling Riverside Blues.”

And then there was Clapton. Initially taken aback by the intensity of Johnson’s work, he writes in his autobiography that, after letting the record get under his skin, “I realized that, on some level, I had found the master, and that following this man’s example would be my life’s work.” In 1966, with John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, he recorded Johnson’s “Ramblin’ on My Mind,” and then, in 1968, with the band Cream, he worked up an electrified and modified take on Johnson’s “Cross Road Blues” called “Crossroads” that became one of his signature hits. But only after recording his 2004 homage to the blues musician, Me and Mr. Johnson, and filming a companion DVD, Sessions for Robert J, was Clapton left with the sense that “my debt to Robert was paid.”

As interest in Johnson’s music was rekindled, curiosity about the man grew. When King of the Delta Blues Singers

was released, in 1961, Johnson’s life was almost a complete mystery,

save for the lurid bit of information included in the album’s liner

notes that he had been murdered, “poisoned by a jealous woman.” But as

Columbia’s Johnson release helped spark new interest in the blues

artists of the 20s and 30s, field researchers and journalists began to

comb the South in search of clues to the lives musicians led. Johnson

“was the toughest case to crack,” says blues researcher Gayle Dean

Wardlow, author of Chasin’ That Devil Music and the first

person to track down an actual document pertaining to the blues

musician: Johnson’s death certificate, which Wardlow found in 1968. The

record indicated that Johnson died at the age of 26 on August 16,

1938—the same month and day that would claim Elvis Presley in

1977—although it is believed today that Johnson was actually 27. The

document lists no cause of death, but years later someone checked the

back of Johnson’s death certificate and discovered notes that suggest

the owner of the plantation where Johnson died believed syphilis was the

cause. It is one of the niggling details that fly in the face of what

has become the generally accepted story of Johnson’s death: that he was

somehow slipped poisoned whiskey after a juke-joint owner who had hired

Johnson to play at his establishment discovered that the blues musician

was keeping time with the owner’s wife. Some researchers suspect that

Johnson may have survived the poisoning, only to succumb to pneumonia

that attacked his weakened immune system.

But one aspect of Johnson’s life remained stubbornly concealed. In 1971, Columbia released a second volume of King of the Delta Blues Singers, and its cover featured an artist’s rendering of Johnson at his first recording session, playing his guitar while facing the corner of a room. As on the first album, the features of his face were barely discernible for good reason: no one yet knew what Johnson looked like. But that was about to change. And with it would begin a new and disputed chapter in Johnson’s story.

In 1972 a

Smithsonian field researcher named Robert “Mack” McCormick, who had been

on the blues musician’s trail for more than a decade, located Johnson’s

two half-sisters and came away with not only photos of Johnson and

members of his family but, reportedly, first publication rights as well.

McCormick, who had a reputation as an inspired researcher and an

excellent writer, had gone as far as to travel to Mississippi on the

Rolling Store, a bus that had been converted into a canteen for

sharecroppers—and, in a 1976 Rolling Stone piece, he told writer Peter Guralnick that he had even tracked down and interviewed Johnson’s killer.

McCormick intended to write about this and other revelations in a book about Johnson that he had tentatively titled Biography of a Phantom. Presumably, it was where the first published picture of Johnson would appear as well. But Guralnick’s Rolling Stone piece reported on another man on Johnson’s trail who had come up with his own trove of historical gold and would use it to steal McCormick’s thunder and essentially take control of Robert Johnson’s image and music. A year or so after McCormick had located Johnson’s kin, a record collector and researcher named Steve LaVere, the son of the late jazz pianist and vocalist Charles LaVere, tracked down one of the half-sisters, Carrie Thompson, in Maryland, and hit the jackpot. (Thompson and Johnson were both the children of Julia Dodds but by different fathers.) Since McCormick had come and gone, Thompson had found two more photos of Johnson, the Hooks Bros. photo and the photo-booth self-portrait, and in 1974 she permitted LaVere to make copies of them. Under the assumption that she was Johnson’s next of kin—the second half-sister had reportedly died by then, though Johnson’s mother and other half-siblings were still alive—she also signed an agreement that transferred to LaVere “her right, title and interest, including all common law and statutory copyrights” to the two photographs, as well as a handwritten note Johnson had purportedly composed on his deathbed and, most important, all musical works and recordings of Robert Johnson.

The deal also gave LaVere first right of refusal for any subsequent Johnson-related photos or documents that might be found, and, more crucially, appointed him as Thompson’s agent “for the purpose of collecting royalties in connection with any and all works of Robert L. Johnson” and authorized him “to use whatever means at his disposal to make such collections.” In return, he would split any royalties generated 50-50 with Thompson.

Contract in hand, LaVere went to Columbia Records with an idea to produce an anthology of Robert Johnson’s complete recordings. According to a 1991 piece by Robert Gordon in L.A. Weekly, Frank Driggs, the producer who had worked on both of the King of the Delta Blues Singers releases, was already planning just such a project for Columbia, but John Hammond père added Steve LaVere as a co-producer. In addition, Gordon reported, Hammond, a friend of Charles LaVere’s, signed away the copyrights to Johnson’s music, which Columbia Records may not have even owned. (If Johnson ever signed a contract with American Record Corporation, it has yet to be located, but chances are that, by the 70s, the copyrights to his recordings had expired and his music had entered the public domain.) Driggs told Gordon, “LaVere got a deal such as nobody I’ve ever heard of getting in the history of the business.”

It appeared that all rights to the blues artist who had possessed the Hammonds, Clapton, Jagger, Richards, Plant, Page, and Dylan were now in the possession of Steve LaVere.

When Mack McCormick heard about LaVere’s deal, he contacted Columbia and notified the label that his agreement with Johnson’s half-sisters preceded LaVere’s. Columbia put the anthology on hold for 15 years, during which time vinyl LPs gave way to plastic CDs. In 1990, Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings was finally released. LaVere was listed as a producer, and the biographical essay published in the boxed set’s accompanying booklet carried his byline. Mack McCormick was not involved at all. The Complete Recordings went gold, rekindling interest in Johnson yet again. It put a nice chunk of change in LaVere’s pocket, and it also cemented his status as the gatekeeper to all things Robert Johnson. In that role he soon became known for litigious ways. He sued or threatened to sue bands and artists, and their representatives—including, successfully, ABKO Music, former record label of the Rolling Stones—who had covered Robert Johnson songs and, he alleged, not paid proper royalties. When the cartoonist Robert Crumb drew a vivid homage to Johnson, based on the photo-booth self-portrait, and then had it reproduced on T-shirts and, later, silkscreen prints, LaVere threatened legal action. Initially, Crumb says, “I wrote back a letter that said, ‘Fuck you. It’s my drawing and I’ll do what I want with it.’ ” But faced with the prospect of an expensive legal battle, he eventually settled with LaVere. “If I ever want to use that drawing commercially again,” Crumb says, “he gets part of the action.”

In the late 90s, LaVere also sued McCormick—unsuccessfully—in an attempt to gain possession of the photographs that the Texas researcher had been given by Carrie Thompson. One of the images is of Johnson. It is believed to be another shot taken during the Hooks Bros. studio session, but has yet to be seen by the public. One of the few people who have seen it is Guralnick, who wrote about it in his 1989 book, Searching for Robert Johnson. In the photo, Johnson is joined by a man in a sailor’s uniform—his nephew, who was in the navy (and, according to a comment attributed to Carrie Thompson, was the owner of the pin-striped suit Johnson is wearing). The whereabouts of this photo are currently unknown, and McCormick’s Biography of a Phantom was never published. McCormick did not respond to my requests for an interview, but in a 2002 profile by Michael Hall in Texas Monthly, McCormick revealed that he suffers from crippling “manic-depressive illness,” and that he had abandoned his Johnson book. “It ain’t happening anymore,” he told Hall. “I lost interest.” But a source who has had contact with Mack McCormick in the last two years told me, “One of the reasons McCormick’s Johnson book has never seen the light of day, I think, is that he seems scared of litigation from a notoriously litigious guy like Steve LaVere.”

Dealing with the legacy of Robert Johnson had become a particularly brutal game of cuttin’ heads, and Steve LaVere seemed to be the man holding the sharpest scythe.

Younger than His Years

When I first encounter Zeke Schein, almost two years have passed since he purchased the photo. I hear about him through a friend, a lawyer who has represented me in business dealings. Schein is also a client, and, one afternoon when he is on break, we meet outside Matt Umanov and head to an Italian espresso joint a few storefronts away. After telling me that his legal name is Steven, but that “no one” ever calls him that, Schein places an 8-by-10 blowup of the photo on the table in front of me. The first thing I notice is the repeating pattern of warning bars that have been superimposed horizontally across the image. One reads, this image is copyrighted. The other, unauthorized use is prohibited by law. The next is that the faces peering back at me beneath wide-brim hats appear remarkably young, but the figure holding the guitar does resemble Johnson, and his fingers are long. I remember a description of the blues artist as looking younger than his years.

Schein peers at me from beneath his own hat—a retro-looking stingy-brim that rides low on his head. Lanky, appropriately pale, and dressed in a black T-shirt and black jeans, with a strand of Tibetan sandalwood mala beads wrapped several times around his left wrist, he looks as though he could be a rock band’s roadie or a member of Jack Kerouac’s entourage. He recounts how he came to acquire the photo, then points at it and says, “What I can confirm is that the guitar itself—and I feel very comfortable saying this—is a Chicago-made guitar from the mid-30s.”

I study the picture. The instrument is shrouded in darkness. It is possible to make out a fancy tailpiece down by the bridge and the dots on the fretboard, but the insignia on the headstock is blurred, and the arm of the man who’s supposed to be Johnson is covering the sound hole. Plus, my gaze keeps being drawn to those long, long fingers.

“You can tell that?” I ask him.

“I’ve looked at thousands of these,” he says, and explains that, actually, the guitar was probably a prop. There are no strings on it, and it is missing all but one of its tuning pegs. But, he tells me, it is probably a guitar made in the mid-1930s by the Chicago-based Harmony Company. “That guitar, with 12 frets to a body like that, with that specific tailpiece, it’s screaming 1935 to me,” he says. “I just can’t find out more about it. It’s driving me crazy. The decal on the headstock is slightly blurred.” And then he adds with a laconic smile, “It fits in perfectly with the Robert Johnson enigma.”

In the two years

since he acquired the image, Schein explains, he has quietly been

trying to research it and, if possible, find someone who can tell him

definitively that he has a photo of Robert Johnson and Johnny Shines. “I

don’t want to put it out there and have people be disappointed that

it’s not real,” he says.

So far, he has come up with one good lead. While scouring the Internet for anything he could find on Johnson, Schein ran across a Web site that the filmmaker Peter Meyer had set up in conjunction with his Johnson documentary, Can’t You Hear the Wind Howl? On the site, Schein learned a bit of heartening trivia: according to an interview Johnny Shines gave before his death, a photo of him and Robert Johnson had been taken by a woman named Johnnie Mae Crowder in Hughes, Arkansas, in 1937 and later published in a local newspaper.

Schein tells me that after acquiring the photo he began showing it to a small number of trusted friends and clients, seeking their opinion—John Hammond is “sure” the photo depicts Johnson—and advice on how to go about getting the image authenticated.

Schein also showed the image to a collector of blues records and memorabilia named John Tefteller, who has scored a number of significant finds in recent years. In 2005, Tefteller, who’s based in Grants Pass, Oregon, had purchased a large cache of original advertising materials produced for the long-defunct jazz-and-blues label Paramount Records, and it had yielded the first full body shot of Charley Patton, who is considered the father of the Delta blues. Tefteller says he saw Schein’s photo for only a few minutes, “at a diner” during a stopover in New York, but what he saw was enough to persuade him to make a trip down to Hughes, Arkansas, in search of Johnnie Mae Crowder, the woman who Shines said had taken the photo of him and Johnson. Tefteller found a 1918 birth certificate for someone with that name, but he also found a death record. Johnnie Mae Crowder had died in 1940, not long after Robert Johnson, and, Tefteller says, though he looked he could find no evidence that Crowder had left behind any family. He had hit a dead end.

Schein wasn’t having any better luck. In May 2006, he learned that two veteran Delta bluesmen, David “Honeyboy” Edwards and Robert Lockwood Jr., were playing at B. B. King’s Blues Club in Times Square. For a guy trying to establish the bona fides of a Robert Johnson picture, the show was a real opportunity. In his memoir, The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing, Edwards writes about witnessing a clearly ill Johnson trying to play at what would be his last show, and later, seeing him suffer greatly from what he asserts were the effects of poisoned whiskey. Lockwood, meanwhile, had learned how to play guitar from Johnson during the years that the itinerant artist lived on and off with Lockwood and his mother in Helena, Arkansas. But when Edwards’s manager allowed Schein to show his picture to the musicians—on the condition that he not prompt them with Johnson’s and Shine’s names—neither identified the men in the photo. Still, Schein wasn’t ready to give up. The bluesmen hadn’t said it wasn’t Johnson, and there was another man who might be able to help.

About four

months after our first meeting, Schein agrees to let me take a copy of

the picture to Mississippi to see if I can make any progress in

determining whether it’s authentic or fake. I fly to Memphis and drive

to Crystal Springs, Mississippi, the town a man named Claud Johnson

calls home.

In 1989, a protracted and, at times, strange legal battle to determine Robert Johnson’s heir had begun in Mississippi. The proceeding was set into motion by two heirs of the bluesman’s half-sister Carrie Thompson. In 1980, she had attempted to rescind the 1974 agreement she had signed permitting Steve LaVere to make copies of the Hooks Bros. and photo-booth portraits and to profit from them. She died in 1983, but her will transferred any rights she still had to those pictures—and any money she was due from them—to her heirs, who turned to the Mississippi judicial system in hopes of gaining control of the estate and eventually recovering the Johnson photos. But after a nine-year legal scrum during which at least two other potential Johnson heirs joined the fray, and the case bounced between the Mississippi Chancery Court, the Mississippi Supreme Court, and the U.S. Supreme Court (which twice refused to hear the case), the Chancery Court ruled on October 15, 1998, that a truckdriver named Claud Johnson, who, according to his lawyer, had long heard that the blues legend was his father, was “the biological son and sole heir” of Robert Johnson; he was thus entitled to an initial inheritance of more than $1.3 million with future revenues. The court’s decision, which is irreversible because it was appealed and reaffirmed, was based not on DNA evidence but on an unusual bit of sworn testimony by the elderly Eula Mae Williams, a childhood friend of Claud Johnson’s mother, Virgie Jane Smith Cain. In what sounds more like a scene from Boston Legal than an actual court case, Williams testified that she had watched Cain and Robert Johnson having sex in a wooded area in the spring of 1931, which, nine months later, led to the birth of Claud.

In June 2000, a few days after the Mississippi Supreme Court had reaffirmed the Chancery Court’s decision, Claud gave an interview to The New York Times in which he talked about glimpsing Robert Johnson from the doorway of his grandparents’ house one day in 1937 when the blues artist showed up to visit his mother and the child he had purportedly sired. But a father-and-son reunion did not take place—Claud’s grandparents would not allow it. “They said he was working for the devil, and they wouldn’t even let me go out and touch him,” Claud told the Times. “I stood in the door, and he stood on the ground, and that is as close as I ever got to him.… I never saw him again.”

I was aware that the court’s ruling hadn’t exactly quelled skepticism in the blues world about Claud’s legitimacy, and that if Claud had indeed seen Robert Johnson at least 69 years had passed since then, but I thought that if I could get Claud to see the photo without involving his lawyers, though it might not lead to any definitive answers, it could lead somewhere interesting.

Schein, too, was curious to know what Johnson’s legal heir would make of the photo, and, after consulting with his attorney, he gave me permission to show Claud the photo, even though it carried a potential risk. According to copyright law, because Robert Johnson is no longer alive, his estate controls the right to use his image in a commercial context, which meant that although Schein owned the photograph outright he would have to seek the estate’s permission if he wanted to use the photo in such a manner. Schein had no intention of angering the estate, but there was a chance that, when I showed up on Claud Johnson’s doorstep, he would be more litigious than curious and initiate a legal tug-of-war for the photo.

Just such a skirmish is being waged over the two well-known Johnson photos that LaVere found in the 70s via a pending suit that Carrie Thompson’s heirs have filed in Mississippi Circuit Court against LaVere and Claud Johnson. In the meantime, there are indications that LaVere continues to make money off of Robert Johnson: legal documents indicate that, although LaVere’s deal as exclusive agent has been terminated, he is still splitting royalties with the Johnson estate on at least a couple of licensing deals. He’s quick to label his controversial status in the Johnson world “just so much hogwash” when I contact him. “People aren’t supposed to make money in the music business?” he asks. “Or is it just the blues that they’re not supposed to make money on?”

When I arrive at

the 49-acre property where Claud Johnson lives (and where he keeps his

gravel truck parked on his lawn), he isn’t home, and his son Michael,

who lives next door, has to get on the phone and persuade him to come

back so that I can show him the photo. He arrives sheathed in sunglasses

and a straw cowboy hat, looking more like Muddy Waters than Robert

Johnson. He is stockier and wider-faced than I would expect the son of

lithe Robert Johnson to be, but then again, Robert Johnson never drove a

gravel truck, and my mental image of him comes from a couple of photos

taken long before the thickening of middle age had a chance to encroach.

Though Claud is clearly uncomfortable when he shakes my hand, his grip

is strong, and the gray in his sideburns and mustache is the only sign

that he is a man in his 70s.

I pull the photo out of the envelope I’ve been carrying and hand it to Claud. “Well, no doubt about it,” he says after studying it for a few long seconds. “This look like before he was grown.”

Claud hands the photo back to me and walks away. When I attempt to get him to elaborate upon what he has just said, he explains that he has signed an agreement with HBO (for what I will later learn is a movie that the cable network is developing about Robert and Claud Johnson, which is being written by James L. White, the screenwriter of Ray). “If you cross a company like that, you could get yourself in a problem. And I really don’t need to get in a problem with HBO,” Johnson tells me, adding that as a result he can’t give me any further “insight” into the picture. “It may be a picture of him, but I really, I can’t really—I’m afraid, you know?” he says, sounding genuinely anguished. “Because, man, I’ll tell you—they’re still after me any way they can get at me, right now.”

I realize that Johnson is talking about the court battle that determined he was Robert Johnson’s heir, and perhaps the current legal skirmish being waged over Carrie Thompson’s photos. On the way back to my car, Michael Johnson apologizes for not being more helpful. He is wearing a T-shirt advertising the Robert Johnson Blues Foundation, an organization dedicated to preserving the music and the memory of the artist, which is run by another of Claud’s sons, Steve Johnson.

“My dad just got shell-shocked by that case,” Michael tells me. “They put him through a lot of stuff. To actually prove who you is”—he switches to the second person, though he is clearly talking about his dad—“they ask you a thousand questions. Hell, they tried to scrutinize him like he wasn’t nothing, you know, man?”

“The Face Doesn’t Lie”

In late summer 2007, Schein’s attorney, John Pelosi, submitted the photograph to John Kitchens, the lawyer for the Johnson estate, to see if there was any way of authenticating it. Kitchens’s father, Jim Kitchens, had been the lead attorney in Claud Johnson’s fight to be named heir of the Johnson estate, but he had since turned the day-to-day handling of the estate over to his son, who turned 30 this year and was all of 12 when the Johnson boxed set was released. Not surprisingly, when John Kitchens saw a copy of the photo, he wasn’t exactly floored. “I didn’t know who it was,” he says. But Kitchens remembered reading about a forensic artist who, that August, had reportedly determined the identity of the sailor kissing the nurse in Alfred Eisenstaedt’s famous Life-magazine photo of Times Square on the day World War II ended. The artist’s name is Lois Gibson and she works for the Houston Police Department. She is also a graduate of the F.B.I. Academy Forensic Artist Course and was deemed “The World’s Most Successful Forensic Artist” in The 2005 Guinness Book of World Records because, at the time, her sketches and facial reconstructions had helped net more than 1,062 criminals.

Kitchens sent Gibson a copy of Schein’s photo, along with reproductions of the Hooks Bros. portrait and the photo-booth shot. Gibson compared the facial features in each of the three photos and reported back with a pretty startling conclusion: “My only problem with this determination is the lack of certainty about the date of the questioned photo,” she wrote in her report to Kitchens. But, she continued, if Schein’s photo “was taken about the same time as, or a little earlier than,” the photo-booth self-portrait, “it appears the individual in [Schein’s photo] is Robert Johnson. All the features are consistent if not identical.”

“If the time frame is right, it’s him,” Gibson tells me when I call her up in Houston. “The face doesn’t lie.” She also points out that if Schein’s photo does depict Johnson, he’s probably younger—possibly two to four years younger—than he appears in the photo-booth self-portrait (which would mean that Schein’s photo had been taken years before the picture Johnny Shines remembered from 1937).

Kitchens is cautiously optimistic about Gibson’s assessment. “Based on the findings, we’re going to get behind it,” he says. “It is impossible to say with 100 percent certainty that this is Robert Johnson,” he adds, pointing out that the few living souls who knew Johnson when he was alive haven’t seen him in 69 years. “But we strongly believe that it is.”

When I meet

Schein at a Greenwich Village restaurant to discuss Gibson’s findings, I

expect him to be ecstatic. But, actually, he seems slightly conflicted,

and I soon realize why. Schein has enjoyed his long strange trip

through Robert Johnson’s past and isn’t ready to let go. Although he

tells me he thinks Gibson “did a wonderful job” with her analysis, he

says he doesn’t agree with her findings that his photo depicts a Johnson

who is younger than the man in the photo-booth shot. “I’ve been delving

deep,” Schein tells me, and though he still hasn’t been able to crack

the make and model of the guitar in his photo, he has come up with a

theory about the chronology of the three pictures: They were, he says,

all taken within a year of one another. The Hooks Bros. photo was taken

first, the self-portrait second, and his photo third, which would make

it the latest photo of Johnson, instead of the earliest. His reasoning

for this, he explains, is that his photo comes after Johnson has

recorded his 29 songs and come away with several hundred dollars,

probably the most money he’d ever made. As a result, he doesn’t need to

borrow a suit from his nephew, as he did in the Hooks Bros. photo. He

can afford his own duds and more. “You got the money from the record

deal. People recognize you. You got your own suit,” Schein says. “You’re

traveling around. You’re drinking better whiskey. You’re eating better

food. Guess what? You’re going to look a little better.”

It is just a theory from a man who plays guitar and works with musicians, a man who respects Robert Johnson, who knows his music, and, after studying his life, feels like he knows Johnson a bit, too—a man who wants to believe that Robert Johnson was singing the blues, but that he wasn't always living them.

Frank DiGiacomo is a Vanity Fair contributing editor.

http://www.robertjohnsonbluesfoundation.org/biography/

http://modernnotion.com/robert-johnson-the-blues-genius-who-sold-his-soul-to-the-devil/

Robert Johnson: The Blues Genius Who Sold His Soul to the Devil

by Jes Greene

January 11, 2016

Modern Notion

A newly found photo has the music world buzzing with excitement. Could this be a picture of the legendary music genius Robert Johnson? Even though bands including The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and The White Strips have covered Johnson’s music, there are only two other confirmed photos of the musician in existence. But who exactly is this guy?

Though his impact on the music industry is unquestionable, we actually know very little about Robert Johnson. Of the few things we know, Johnson was born in 1911 to impoverished parents on a plantation in the Mississippi Delta. And from there, much is legend. The stories go that Johnson loved to play music but was so terrible he’d annoy anyone in the vicinity of his playing. When Johnson was a teen, he ran away to Arkansas for six months, and when he returned, was suddenly a master of the guitar. Though it’s most likely that he devoted himself to learning the intricacies of the guitar from various teachers or mentors while he was away from home, a much more alluring myth has sprung up to explain the transformation.

Legend has it that one evening after fleeing home, Johnson met the devil at the crossroads of U.S. Highways 49 and 61 in Clarksdale, Mississippi at midnight. Wanting nothing more than to have the sharpest skills possible, he traded his soul to the devil in return for musical genius on the guitar. From that moment on, Johnson had an uncanny talent that allowed him to travel around the U.S. as an itinerant musician, playing on street corners and crummy joints. In 1936, he finally recorded an album in San Antonio and then another in Dallas the following year. In total, he recorded only 29 songs, but he laid so many of the foundations for rock ‘n’ roll as it would become.

Part of Robert Johnson’s revolutionary impact was the way he played the guitar, making it sound like he was actually playing two guitars instead of one. He did so by partially playing the driving rhythms on the guitar’s lower strings and the melodic chords on higher strings. His hallmark technique was the turnaround but he also used up-the-neck chords, chromatic movement, melodic fills between vocals and a host of others. Johnson was versatile, using both classical methods and twangy improvisations of his own in order to create the haunting sound that influenced everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Jack White. His tunings, though, continue to create the strongest fodder for debate. Because Johnson’s records were sped up when they were first released, it makes it impossible to truly analyze Johnson’s tunings and capo positions, but that doesn’t stop continued fierce debate.

During his lifetime only one of his songs, “Terraplane Blues,” caught anyone’s attention. It was only in 1961 when Johnson’s first LP was reissued that his music took flight. The driving force behind releasing the LP was John Hammond, the same talent scout who discovered Billie Holiday in the early ’30s. In 1938, Hammond sought out the genius blues player to participate in his “Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie, a show comprised of all black musicians and some of the greatest blues and jazz musicians of the time. Tragically, Johnson died right before, at the young age of 27. Unfortunately, just like so much of Johnson’s life the details of his untimely death remain mostly a mystery.

Despite Johnson’s death, Hammond didn’t forget Johnson’s talent. As he pushed for Johnson’s music to be released over 20 years after the blues musician’s death, Hammond ensured that Johnson’s legacy live on. As that LP was played on the radio, it inspired an untold number of artists and eventually landed Robert Johnson the number five position in Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Guitarists. Many would agree with Eric Clapton who said, “Robert Johnson to me is the most important blues musician who ever lived…I have never found anything more deeply soulful than Robert Johnson. His music remains the most powerful cry that I think you can find in the human voice.”

Take a minute to listen to Johnson’s twangy blues, and see if you can spot his influence on your favorite rock ‘n’ roll artist. Pay special attention to “Cross Roads Blues,” “Sweet Home Chicago” and “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,” which Rolling Stone says are among the most popular blues songs of all time.

http://articles.latimes.com/2011/may/01/entertainment/la-ca-robert-johnson-20110501/2

POP MUSIC

Bluesman at 100, ever at a crossroad

Decades after his death, reverence and debate still swirl around the legendary bluesman who supposedly made a deal with the devil.

May 01, 2011|Randy Lewis

CLARKSDALE, MISS. — The intersection of DeSoto and State streets here doesn't look like anything special.

On the southeast corner of the roads is H Town Custom Wheels. Across DeSoto to the west is Beer & Bud Mart, which faces a Church's Chicken stand. Immediately to the east of that are the Delta Donut shop and Abe's BBQ, the latter noting its service to residents and visitors since 1924.

Yet this is the focal point of one of the towering legends of 20th century popular music -- the original intersection of Highways 61 and 49, the place where seminal blues musician Robert Johnson is said to have arrived one midnight to seal a deal with the devil, trading his soul to become the greatest blues musician in history.

Perhaps.

Actually, there are at least three such crossroads around northern Mississippi, any of which might be the one Johnson had in mind 75 years ago when he wrote his signature song "Cross Road Blues" -- and that's only relevant to those who are remotely likely to believe in such things.

The only sign of anything out of the ordinary today at the crossing of 61 and 49 is a triangular traffic island with a tall pole atop which are three identical oversized replicas of a blue electric guitar -- not, by the way, the type of instrument Johnson played in the 1930s.

But whether his reputation was the outcome of a supernatural bargain or simply natural-born talent combined with patience and practice, Johnson remains the man most broadly considered the preeminent bluesman of all time, a reputation that grows only more solid as the 100th anniversary of his birth in Hazlehurst, Miss., approaches on May 8.

Consider that during his lifetime, his biggest-selling recording, "Terraplane Blues," sold about 5,000 copies. When the "King of the Delta Blues Singers" LP surfaced in 1961 with 16 of his songs, it sold around 20,000 copies. Since its 1990 release, a two-CD box set of all his known recordings has sold 1.5 million copies. That's despite detractors who have suggested his reputation is over-inflated.

"Robert Johnson to me is the most important blues musician who ever lived," said Eric Clapton, who helped turn a generation of rock fans on to Johnson playing an amped-up version of "Crossroads" with the English power trio Cream in 1968. "I have never found anything more deeply soulful than Robert Johnson. His music remains the most powerful cry that I think you can find in the human voice."

References to the supernatural in songs such as "Cross Road Blues," "Me and the Devil Blues" and "Hell Hound on My Trail" have only enhanced the mystery surrounding Johnson's seemingly overnight transformation from a competent guitarist and singer to the music's most powerful proponent before his death at 27 from poisoning by the jealous partner of a woman.

Hundreds of musicians from the famous to the obscure have recorded his songs over the last half-century since Johnson's own recordings first surfaced in a major way. Dozens of tribute albums have been recorded, and books, plays and films have been made about his extraordinary life, much of it shrouded in uncertainty.

The question is why. Johnson was just one of hundreds of African Americans struggling to eke out a living playing music in rural Mississippi in the early part of the last century, the only alternative for many to the backbreaking labor harvesting cotton in acre after acre of fields that still cover this part of the state.

Even a partial list of the music greats who emerged from Mississippi is imposing: Muddy Waters, B.B. King, John Lee Hooker, Elmore James, Son House, Charley Patton, Lonnie Johnson, Willie Dixon, Bo Diddley, Howlin' Wolf, Robert Junior Lockwood. And then there are blues-influenced rock and R&B giants including Elvis Presley and Sam Cooke. That cultural richness is the reason the Grammy Museum just announced that it has chosen Cleveland, Miss., as the site for its first facility away from its home in Los Angeles.

Before Johnson came along, others were playing the Delta blues. Artists such as Patton, Brown and House were major influences on him. But Johnson's hauntingly expressive, high-pitched voice, the sophistication of themes and lyrics in his songs and a technical mastery of the acoustic guitar that still has musicians scratching their heads in wonder all helped elevate him above his musical predecessors, peers and descendants.

One of those peers, 96-year-old David "Honey Boy" Edwards, will take part in a major centennial tribute to Johnson and his music coming up Thursday through May 8 in Greenwood, Miss., the town of about 15,000 where he is buried.

Even that core piece of biographical information wasn't confirmed until about 10 years ago. That site is now marked with a stately tombstone at the Little Zion Missionary Baptist Church about three miles north of Greenwood.

"So many mysteries remain, some we may never resolve," pianist and music historian Ted Gioia writes in the notes accompanying "Robert Johnson: The Complete Original Masters -- Centennial Edition," released Tuesday to mark the occasion. It culls all 29 recordings and the surviving alternate takes from his only recording sessions, the first in San Antonio in 1936, the last in Dallas the following year.

Fact or fiction, it can seem everyone in this region wants a piece of the Johnson crossroad myth.

"He was poisoned at a little joint called Three Forks, which is at the crossroad of Highways 49 and 82 -- that could have been the mythical crossroad," said Paige Hunt, executive director of the Greenwood Visitors and Convention Bureau, which is coordinating the four-day Robert Johnson 100th Birthday Celebration this weekend.

Shelley Ritter, director of the Delta Blues Museum in downtown Clarksdale, notes that Living Blues magazine in 1990 identified the most likely sites as the intersection of 61 and 49 in Clarksdale or 61 and 82 in Leland.

Historian and Johnson authority Steve LaVere, the lawyer who championed his music and navigated through multiple lawsuits in recent decades to establish the rights of Johnson's son, Claud, as the legitimate heir to his estate, wants no part of such debates.

"If you want to know where he died, where he lived, where he was born, where he was poisoned -- any factual information, I'll tell you," said LaVere, who moved from Glendale, Calif., to Greenwood about 10 years ago to work on Johnson matters. "But don't ask me about that crap about the crossroad."

Besides, given the string of casinos that have opened in recent years along Highway 61, a.k.a. "the Blues Highway," between Memphis and Clarksdale, there's no shortage of real-world places to make Faustian bargains for those so inclined.

That taboo subject aside, LaVere has lost none of his passion for Johnson's music through more than four decades of work.

"If the music was second-rate, you'd say, 'What's all this fuss about?' But the music delivers," LaVere said. "The mystery and the myth and all that stuff become even more appealing when the music is something of value."

Claud Johnson's son, Steven, is a 51-year-old preacher who in 2009 started singing his grandfather's music to keep the family connection to the music alive. His Robert Johnson Grandson Band also is performing in Greenwood for the centenary festival.

"I believe the crossroad was a point in my granddad's life," he said. "In 'Drunken Hearted Man,' when I heard that song, it felt like my granddaddy was speaking to me, saying what kind of man he was, saying that if he could change his living, he would."

Johnson's posthumous fame also has sparked backlash. Some scholars have gone so far as to debunk not only the Johnson myths but his stature in the blues world.

"As far as the evolution of black music goes, Robert Johnson was an extremely minor figure, and very little that happened in the decades following his death would have been affected if he had never played a note," musician and author Elijah Wald wrote in his 2004 book, "Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues."

"The fact is, from the first, all sorts of people who heard Johnson had the same experience W.C. Handy did on that (mythical?) night he describes in his autobiography when he first heard someone play the blues," said Greil Marcus, who explored Johnson's legacy in his 1975 book "Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock 'n' Roll Music." "Handy -- the canniest and most ambitious black purveyor of black popular music -- couldn't believe what he heard.' And that's what people have continued to hear since."

Some have even debated the veracity of what everyone has been hearing for seven decades, suggesting the otherworldly sound of Johnson's voice and guitar are merely the result of all-too-worldly speeding up of his recordings -- a theory roundly dismissed by those with access to the original discs.

Musicians, for the most part, seem to think there's enough mystery in the music itself to obviate the need for additional mythology.

In his autobiography "Life," Rolling Stones songwriter and guitarist Keith Richards said that Johnson "took guitar playing, songwriting, delivery, to a totally different height. ... Robert Johnson was like an orchestra all by himself. Some of his best stuff is almost Bach-like in its construction."

Thematically too, Johnson "took the blues into new artistic areas in a new, self-consciously artistic mode," music journalist Peter Guralnick wrote in his 1982 book "Searching for Robert Johnson." "Where someone like Son House or Charley Patton was content to throw together a collection of relatively traditional lyrics ... Johnson intentionally developed themes in his songs; each song made a statement, both metaphorical and real. ...

"Unlike other equally eloquent blues, this is not random folk art, hit or miss, but rather carefully selected and honed detail, carefully considered and achieved effect."

Even with everything that's been said and written about Johnson over the last half century, debate and new analysis is unlikely to subside.

"Almost any interpretation you have of Robert Johnson can find some justification in the body of work he left behind -- but will still lead you to dead ends and unanswered questions," wrote Gioia. "And it is this open-endedness, this richness, his inexhaustibility of meanings that keeps drawing new listeners to Johnson long after other, more glamorous entertainers of his era have fallen from view."

Info Box

Why is Robert Johnson, above all other blues players, the preeminent figure in that bedrock form of American popular music?

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/debra-devi/robert-johnson-and-the-my_b_1628118.html

THE BLOG

Robert Johnson and the Myth of the Illiterate Bluesman

06/28/2012

(Robert Johnson took this self-portrait in a photo booth in the early 1930s. © 1986 Delta Haze Corporation, all rights reserved; used by permission)

(Robert Johnson took this self-portrait in a photo booth in the early 1930s. © 1986 Delta Haze Corporation, all rights reserved; used by permission)

Robert Johnson: Complete Recordings--

["Centennial Collection"

Rearranged in Chronological Order!]:

THE SAN ANTONIO SESSIONS:

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 23, 1936:

(0:00) Kindhearted Woman Blues [take 1]

(2:55) Kindhearted Woman Blues [take 2]

(5:27) I Believe I'll Dust My Broom

(8:31) Sweet Home Chicago

(11:32) Ramblin' On My Mind [take 1]

(14:26) Ramblin' On My Mind [take 2]

(16:51) When You Got a Good Friend [take 1]

(19:47) When You Got a Good Friend [take 2]

(22:27) Come On In My Kitchen [take 1]

(25:23) Come On In My Kitchen [take 2]

(28:09) Terraplane Blues

(31:13) Phonograph Blues [take 1]

(33:56) Phonograph Blues [take 2]

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 1936:

(36:33) 32-20 Blues

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 1936:

(39:26) They're Red Hot

(42:27) Dead Shrimp Blues

(45:01) Crossroad Blues [take 1]

(47:45) Crossroad Blues [take 2]

(50:18) Walkin' Blues

(52:50) Last Fair Deal Gone Down

(55:30) Preaching Blues (Up Jumped the devil)

(58:27) If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day

THE DALLAS SESSIONS:

SATURDAY, JUNE 19, 1937:

(1:01:06) Stones In My Passway

(1:03:37) (I'm a) Steady Rollin' Man

(1:06:19) From Four 'Till Late

SUNDAY, JUNE 20, 1937:

(1:08:45) Hellhound On My Trail

(1:11:25) Little Queen of Spades [take 1]

(1:13:41) Little Queen of Spades [take 2]

(1:16:05) Malted Milk

(1:18:31) Drunken Hearted Man [take 1]

(1:21:03) Drunken Hearted Man [take 2]

(1:23:34) Me and the Devil Blues [take 1]

(1:26:10) Me and the Devil Blues [take 2]

(1:28:48) Stop Breaking Down Blues [take 1]

(1:31:16) Stop Breaking Down Blues [take 2]

(1:33:36) Traveling Riverside Blues [take 1: w/ guitar test groove]

(1:36:32) Traveling Riverside Blues [take 2: once a lost recording!]

(1:39:15) Honeymoon Blues

(1:41:35) Love in Vain Blues [take 1]

(1:43:57) Love in Vain Blues [take 2]

(1:46:26) Milkcow's Calf Blues [take 1]

(1:48:51) Milkcow's Calf Blues [take 2]

Cross Road Blues

(Music and lyrics by Robert Johnson)

I went down to the crossroad

fell down on my knees

I went down to the crossroad

fell down on my knees

Asked the lord above “Have mercy now

save poor Bob if you please”

Yeeooo, standin at the crossroad

tried to flag a ride

ooo ooo eee

I tried to flag a ride

Didn’t nobody seem to know me babe

everybody pass me by

Standin at the crossroad babe

risin sun goin down

Standin at the crossroad babe

eee eee eee, risin sun goin down

I believe to my soul now,

Poor Bob is sinkin down

You can run, you can run

tell my friend Willie Brown

You can run, you can run

tell my friend Willie Brown

(th)’at I got the croosroad blues this mornin Lord

babe, I’m sinkin down

And I went to the crossroad momma

I looked east and west

I went to the crossroad baby

I looked east and west

Lord, I didn’t have no sweet woman

ooh-well babe, in my distress

http://www.robertjohnsonbluesfoundation.org/biography/