SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2016

VOLUME TWO NUMBER THREE

WAYNE SHORTER

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LEO SMITH

March 26-April 1

AHMAD JAMAL

April 2-8

DIONNE WARWICK

April 9-15

LEE MORGAN

April 16-22

BILL DIXON

April 23-29

SAM COOKE

April 30-May 6

MUHAL RICHARD ABRAMS

May 7-13

BILLY HARPER

May 14-20

SISTER ROSETTA THARPE

May 21-27

QUINCY JONES

May 28-June 3

BESSIE SMITH

June 4-10

ROBERT JOHNSON

June 11-17

Encyclopedia of Jazz Musicians

Abrams, Muhal Richard

(b. September 19, 1930)

(b. September 19, 1930)

Pianist and composer Muhal Richard Abrams combines influences from

classical, jazz and experimental music in a prolific, thorougly modern

and personal body of work. Cofounder and New York chapter president of Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, he has dedicated his life and career towards the progress of new music in the jazz idiom.

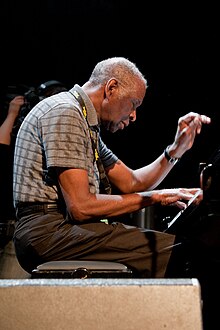

Muhal Richard Abrams (photo by Michael Wilderman)

As a pianist, Abrams's style includes free jazz, bebop, contemporary classical music and stride piano. Muhal's technique runs the gamut of freewheeling blues-inspired reflections, progressive atonality and unbridled phrasing. The result is a sound that is equally reflective of jazz's past as well as its future. Richard Abrams was born on September 19, 1930 in Chicago, Illinois. As a teenager, Abrams attended DuSable High School in Chicago where he focused his attention more towards the school's sports program than the music program. Wanting to learn more about music, Muhal briefly enrolled at Chicago's Roosevelt University. He left stating that what he was learning was not what he was hearing in the Chicago jazz scene. Soon after, Abrams decided to teach himself what he wanted to learn. Upon acquiring a piano, Muhal tirelessly taught himself the fundamentals of music including everything from basic reading skills to transcribing solos. Early influences included Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. When it came to composition, Muhal has cited bandleaders Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington as his primary influences. During this period, Abrams also picked up the fundamentals of several other instruments including the clarinet and cello. He sharpened this composition and arranging skills by observing and listening to other artists as well as analyzing their work. At the age of seventeen, Abrams enrolled at Chicago Musical College, which he attended for four years. In 1948, made his professional performance debut and two years later, he secured a gig writing music for the King Fleming Band. Upon finishing his studies at Chicago Musical College, he began to attend Governors State University where he took courses in electronic music.Throughout the 1950s, Abrams began to accompany several local and visiting musicians in Chicago including drummer Max Roach, saxophonists Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt and singer Ruth Brown, amongst others. In 1957, Muhal became a member of drummer Walter Perkins's group Modern Jazz Two + Three, otherwise known as the MJT + 3. In the following year, he made his recording debut with the group with Daddy-O Presents MJT + 3. The album features several Abrams originals including End of the Line and No Land's Man. In 1961, Abrams and tenor saxophonist Eddie Harris joined forces with trumpeter Johnny Hines to form an ensemble where they could workshop their ideas and compositions. Harris would later state that dozens of enthusiastic musicians of numerous ages and levels of talent attended these workshops, though the ensemble disbanded after several months. Taking the idea of a band to workshop his ideas, Abrams formed his first group the Experimental Band in the early 1960s, which for a brief time included a young Don Pullen. The ensemble featured some of the best talent in Chicago including Harris, saxophonists Roscoe Mitchell and Donald Garret and bassist Victor Sproles. The band was initially started as a rehearsal group and was short-lived. Though the group was momentary, it sowed the seeds of what would later be known as the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, otherwise known as the AACM. The AACM officially formed in Chicago on May 8, 1965. The group was a collective of musicians that wished to see the full sonic potential of their music and each other. Abrams was the group's first president and one of its main proponents. One of the major ideas of the group was the encouragement of young musicians to become familiar with the history of jazz so that they can better experiment in the idiom. They were inspired by the avant-garde jazz that was happening in New York City, with alto saxophonists Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy being of particular inspiration. Before long, the AACM began to expand, including saxophonist Anthony Braxton, trumpeters Lester Bowie and Leo Smith, drummer Steve McCall and violinist Leroy Jenkins. The AACM began to become a Chicago staple with its members starting other groups and side projects including the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the Creative Construction Company.By the late 1960s, Abrams set out to show the world what he had been work shopping with the AACM. In 1967, Muhal recorded Levels and Degrees of Light, his debut album as a leader. The album is of note partly because it was the first recording sessions for Braxton as well charting the course for his compositional genius for decades to come. The album features contributions from Leroy Jenkins, saxophonist Maurice McIntyre, vibraphonist Gordon Emmanuel, bassist Leonard Jones and vocalist Penelope Taylor. Before the release of the album, he added the Muhal in front on his name. In the following year, Abrams performed on Braxton's album 3 Compositions of New Jazz on which he played piano, cello and clarinet. In 1969, Muhal released the album Young at Heart/Wise in Time. He continued his prolific recording with the decade to come by appearing with trumpeter Kenny Dorham on his 1970 release Kenny Dorham Sextet. In 1971, Abrams appeared on Eddie Harris's album Instant Death for Atlantic Records. The album's title song is a great example of Muhal's work in this period.The song begins with Abrams performing a funky phrase on the electric piano before the rest of the ensemble comes into the arrangement. The light, airy performance of Muhal's serves to solidify the free from, yet very tight arrangement of the song. With the help of bassist Rufus Reid, his overall performance is augmented with Reid solidifying the rhythmic foundation of the song, which frees up Abrams's melodic potential. The following year, Abrams released the album Things to Come from Those Now Gone. The album along with his 1976 release Sightsong, showcases the ever-evolving compositional desires of Muhal with both albums incorporating bebop, electronic music, orchestral music and even opera. Released on the Black Saint label, Sightsong was an album co-led with bassist Malachi Favors of the Art Ensemble of Chicago. The same year, he recorded the album Duets with Braxton. In 1975, Abrams moved to New York City where he began to perform and record in a variety of formats whether as a soloist or in duos with Lewis, Braxton, Leroy Jenkins and pianist Amina Claudine Myers. Muhal also led smalls group and a big band that featured saxophonist Henry Threadgill, and drummer Andrew Cyrille amongst others. Upon his arrival in New York City, Abrams found himself a major player in the city's loft jazz scene, which were jazz performances at venues that were once formal industrial spaces in the city's Soho neighborhood. Muhal continued to experiment with different styles with 1978

's 1-OQA+19. The same year, he performed at the Montreux Jazz Festival, which expanded his presence in the European jazz community. By

the early 1980s, Abrams began to experiment with different vocal and

synthesizer effects, an early example being is 1980 album Spihumonesty. The same year, he recorded his project Mama and Daddy, an

ambitious endeavor that saw the instrumentation including strings,

brass and percussion blending with experimental music and chamber music.

Abrams continued his experiments with the orchestra with his 1981 album Blues Forever and its follow-up release Rejoicing with the Light in

1983. During this time, Muhal began to receive more commissions for his

work, including Variations for Solo Saxophone, Flute and Chamber

Orchestra, which was commissioned by the City of Chicago for the 1982

New Music America Festival. Muhal opted for smaller groups with 1985's View from Within. A standout track on View from Within is the song �Down at Pepper�s.�

This blues-infused number showcases the relaxed feel of Abrams, with

his tight piano rolls and blues scale-laden melodic devices. Muhal's use

of descending half steps back into the verse makes the overall blues

feel that much more classic. The song also serves to demonstrate his

superb accompanying skills, with his rich ornamentations serving to

bring out the timbre of trumpeter Stanton Davis Jr.s performance. The

same year, Abrams compositional efforts received a boost in acclaim

when he composed the piece String Quartet #2 for the acclaimed Kronos

Quartet. The piece was premiered on November 22, 1985 at the Carnegie

Recital Hall in New York. On February 7, 1986, Muhal performed with

bassist Cecil McBee at the Carnegie Recital Hall. Four days later,

pianists Ursula Oppens and Frederic Rzewski at the Whitney Museum in New

York City performed his piece Piano Duet #1. In 1987, Abrams released the album Colors in Thirty-Third. The album's title track

is an excellent example of his 1980s compositional efforts. Arranged

for violin, soprano sax, piano, bass and drums, the song showcases how

tight his arranging is for the unusual instrumentation. Richard's use of

counterpoint within the ensemble is especially noteworthy, with each

voice weaving in and out of each other with ease. In the

late 1980s, Abrams led a quintet that featured Stanton Davis and

saxophonist John Purcell. On July 9, 1988, Muhal's piece Folk Tales 88

was performed by the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra at Fort Hamilton

Base in Brooklyn, New York. In, 1989, he performed at the Knitting

Factory in New York with Purcell, Andrew Cyrille and bassist Fred

Hopkins. The following year, he was the first recipient of the Danish

Jazz Center's Jazzpar Award.Abrams began the 1990s with the release of his album Blu Blu Blu. The

album was lauded as one of Muhal's strongest albums as a leader of a

big band. In the following year, he brought his orchestra on a tour of

France. Two years later, he performed in a duo with Roscoe Mitchell. In

1994, Abrams performed in Britain with an octet and in New York with a

quintet that included trumpeter Eddie Allen, bassist Bradley Jones and

drummer Reggie Nicholson. The following year Muhal released the album One Live, Two Views, which featured his continuing experiments with the juxtaposition of jazz, classical music and traditional African music. In 1996, Abrams paid tribute to Thelonoius Monk with the album Interpretations of Monk, Vol. 1. The project came about from a series of recordings he made at Columbia University in 1981 with pianist Barry Harris. The same year, he released the album Open Air Meeting, an album of duets with saxophonist/clarinetist Marty Ehrlich.In

1997, Abrams received a grant from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts

Grants to Artists Award. Muhal continues to be active with the AACM,

serving as the president of its New York chapter. He is also on the

board of the National Jazz Service Association and was once a panelist

for the National Endowments for the Arts and the New York State Council

on the Arts. In 1999, Mayor Richard M. Daley of Chicago

declared April 11, 1999 Muhal Richard Abrams Day in Chicago. Abrams

continues to educate outside of the AACM by teaching composition and

improvisation at several schools and organizations including academic

positions at Columbia University, Syracuse University, and The New

England Conservatory. He has also led workshops and lectured

internationally at The Banff Centre in Canada and The Sibelius Academy

in Helsinki, Finland.In March 2001, Abrams released the album Visibility of Thought on

the Mutable Music label. The album features four contemporary classical

pieces as well as an electronic piece and a thirty-minute piano

improvisation. In October 2006, Muhal released the album Streaming with

George Lewis and Roscoe Mitchell. The album's use of exploratory

electronic sounds juxtaposed with free jazz makes the album a shining

example in the three men's discography. In 2008, Abrams

performed with Amina Claudine Myers at The Kitchen in New York City.

Muhal's most recent release is the live album Vision Towards Essence in

2008. Originally recorded on September 11, 1998 at the Guelph Jazz

Festival in Canada, the album features three solo pieces showcasing the

various techniques and styles of Abrams. In May 2009,

Abrams was declared a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the

Arts, the United States' highest honor for jazz musicians. Abrams lives

in New York City where he continues to perform with his own ensembles

and as a soloist and composer for the orchestra and chamber works.

Select Discography:

As a leader:

Levels and Degrees of Light (1967) Young at Heart/Wise in Time (1969) Things to Come from Those Now Gone (1972)Sightsong (1976) 1-OQA+19 (1978) Spihumonesty (1980) Mama And Daddy (1980) Blues Forever (1981) Rejoicing with the Light (1983) View From Within (1985) Colors in Thirty-Third (1987) Blu Blu Blu (1990) One Live, Two Views (1995) Interpretations of Monk (1996) Visibility of Thought (2001) Vision Towards Essence (2008)

With Anthony Braxton

3 Compositions of New Jazz (1968)

Duets (1976)

With Kenny Dorham

Kenny Dorham Sextet (1970)

With Marty Ehrlich

Open Air Meeting (1996)

With Eddie Harris

Instant Death (1971)

With George Lewis & Roscoe Mitchell

Streaming (2006)

With MJT + 3 Daddy-O Presents MJT + 3 (1958)

Levels and Degrees of Light (1967) Young at Heart/Wise in Time (1969) Things to Come from Those Now Gone (1972)Sightsong (1976) 1-OQA+19 (1978) Spihumonesty (1980) Mama And Daddy (1980) Blues Forever (1981) Rejoicing with the Light (1983) View From Within (1985) Colors in Thirty-Third (1987) Blu Blu Blu (1990) One Live, Two Views (1995) Interpretations of Monk (1996) Visibility of Thought (2001) Vision Towards Essence (2008)

With Anthony Braxton

3 Compositions of New Jazz (1968)

Duets (1976)

With Kenny Dorham

Kenny Dorham Sextet (1970)

With Marty Ehrlich

Open Air Meeting (1996)

With Eddie Harris

Instant Death (1971)

With George Lewis & Roscoe Mitchell

Streaming (2006)

With MJT + 3 Daddy-O Presents MJT + 3 (1958)

http://www.allaboutjazz.com/muhal-richard-abrams-the-advancement-of-creative-music-muhal-richard-abrams-by-aaj-staff.php

Muhal Richard Abrams: The Advancement of Creative Music

by

--Muhal Richard Abrams

At a certain point in the mid-1960s—the exact date escapes

him—pianist/composer Muhal Richard Abrams, a lifelong resident of the

South Side of Chicago, visited New York for the first time on a gig with

saxophonist Eddie Harris at Harlem's Club Barron. "New York suited my

energy, Abrams recalled. "Of course. But I was already in that sort of

energy. I had no doubt that I could be in New York. No doubt at all.

Doubt seems to be a concept foreign to Abrams, 76, who moved to New York permanently in 1975. In 1983, he established the New York chapter of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, commonly known as the AACM, which launches its twenty-fourth concert season on May 11, 2007 at the Community Church of New York with a recital featuring Abrams' quartet and a duo by Abrams with guitarist Brandon Ross.

The institutional pre-history of the AACM began in 1961, when Abrams and Harris joined a West Side trumpeter named Johnny Hines to organize an orchestra where local musicians could workshop their charts. By Harris' recollection, over one hundred musicians of various ages and skill levels attended. Although it disbanded within a few months, Abrams decided to begin another orchestra, which he called the Experimental Band. He recruited younger musicians like Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman, who were interested, as Abrams puts it, "in more original approaches to composing and performing music.

Doubt seems to be a concept foreign to Abrams, 76, who moved to New York permanently in 1975. In 1983, he established the New York chapter of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, commonly known as the AACM, which launches its twenty-fourth concert season on May 11, 2007 at the Community Church of New York with a recital featuring Abrams' quartet and a duo by Abrams with guitarist Brandon Ross.

The institutional pre-history of the AACM began in 1961, when Abrams and Harris joined a West Side trumpeter named Johnny Hines to organize an orchestra where local musicians could workshop their charts. By Harris' recollection, over one hundred musicians of various ages and skill levels attended. Although it disbanded within a few months, Abrams decided to begin another orchestra, which he called the Experimental Band. He recruited younger musicians like Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman, who were interested, as Abrams puts it, "in more original approaches to composing and performing music.

Over the next few years, musicians such as Malachi Favors, Leroy Jenkins, Anthony Braxton, Wadada Leo Smith and Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre entered the mix to participate in the adventure. A certain momentum developed with the Experimental Band as the nucleus and in 1965 Abrams, fellow pianist Jodie Christian, trumpeter Phil Cohran and drummer Steve McCall convened a meeting towards the purpose of forming a new musicians' organization devoted to the production of original music with a collective spirit. Thus, the AACM was launched.

Under the organization's auspices, Abrams mentored composer/instrumentalist/improvisers like Mitchell, Jarman, Braxton, Smith, Henry Threadgill and George Lewis in their nascent years. He also spawned an infrastructure within which each individual had autonomy to assimilate and process an enormous body of music from a broad spectrum of sources in a critical manner and gave them manpower with whom to workshop and develop their ideas while evolving their respective voices.

The AACM first hit New York in May 1970, when cultural activist Kunle Mwanga produced a concert at the Washington Square Methodist Church with Leroy Jenkins and Anthony Braxton (who had relocated from Chicago three months earlier), their AACM mates Abrams, Smith and McCall and bassist Richard Davis (also a South Sider). At the time, Abrams had recorded two albums of his own music—Levels and Degrees of Light (Delmark, 1967) and Young At Heart, Wise In Time (Delmark, 1969). Added to the mix by 1975 were Things To Come From Those Now Gone (Delmark, 1972) and solo piano sessions Afrisong (India Navigation, 1975) and Sightsong (Black Saint, 1975).

Once settled in New York, however, Abrams would record prolifically for the next two decades, with fifteen albums on Black Saint in addition to two dates for Novus, two for New World Countercurrents and one for UMO. You can't pigeonhole his interests—in Abrams' singular universe, elemental blues themes and warp speed post-bop structures with challenging intervals coexist comfortably with fully-scored symphonic works, string quartets, saxophone quartets, solo and duo piano music and speech-sound collage structures.

Abrams resists the idea that location factors into the content that emerges from his creative process. "What affected my output is the opportunity to record, he says. "In Chicago, if an opportunity presented itself, I created something for the occasion. When I got here [NYC], there was no difference. I am always composing and practicing for myself. Actually, it's more like studying than composing; I research and seek and analyze music—or sound, rather, because sound precedes music itself—and things come up. When a recording or something else comes along, I put some of those things together and it becomes a recording. Of course, in New York, I'm hearing more around me, but it doesn't make me process things any differently. I'm still dealing with my individualism.

The notion of following one's own muse at whatever cost was embedded in South Side culture during the years after World War II, when African-Americans were migrating en masse from Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama to Chicago for factory, railroad and stockyard jobs. As Harris told me on a WKCR interview in 1994: "In Chicago, you could hear Gene Ammons in one club, Budd Johnson in another or Tom Archia or Dick Davis—just speaking of the saxophone. Then there were all sorts of piano players that were really...different. You'd go to one club and the guy didn't sound a little different from the guy down the street. It was totally different.

"You were expected to do whatever it is that you felt you wanted to do and nobody said a word, Abrams says of the ethos of the South Side's world-class musician pool. "The jam sessions were like that. We played bebop and kept up with the geniuses like Bird and them. But I was never that interested in copying something and then using it for myself. I was interested in copying it in order to analyze it. Then I would decide how I would use or do that same thing. Chicago was full of musicians who distinguished themselves as individuals.

As an example he cites pianist John Young, best known outside Chicago for his work with tenorist Von Freeman and a prominent stylist since the 1940s. "When you listen to John, you hear remnants of [Earl] Fatha Hines, Abrams notes, leaving unsaid Hines' presence in Chicago from 1926 until the late 1940s. "He was very influenced by Fatha Hines, but John had his own way. We were impressed with the individualism from him, Ahmad Jamal, Von Freeman, Chris Anderson, Johnny Griffin, Ike Day and Sun Ra and the Arkestra. People wonder how an AACM could develop in a city like that. It's because you could do individual things and nobody bothered you.

Abrams himself is a self-taught pianist and composer. "I used to play

sports, but for some reason, whenever I'd hear musicians perform, I had

to stop to listen, he recalls. "It fascinated me and one day I decided

that I wanted to be a musician. So I took off and started to seek out

information about how to play the piano.

Although Abrams attended DuSable High School, where the legendarily stern band director Walter Dyett held sway, he preferred sports to school-sponsored music programs. But by 1946, he decided to enroll in music classes at Roosevelt University in the Loop. "I didn't get too much out of that, because it wasn't what I was hearing in the street, he says. "I decided to study on my own. I don't know why, but I've always had a natural ability to study and analyze things. I used that ability, not even knowing what it was (it was just a feeling) and started to read books.

Although Abrams attended DuSable High School, where the legendarily stern band director Walter Dyett held sway, he preferred sports to school-sponsored music programs. But by 1946, he decided to enroll in music classes at Roosevelt University in the Loop. "I didn't get too much out of that, because it wasn't what I was hearing in the street, he says. "I decided to study on my own. I don't know why, but I've always had a natural ability to study and analyze things. I used that ability, not even knowing what it was (it was just a feeling) and started to read books.

From there, I acquired a small spinet piano and started to teach myself

how to play the instrument and read the notes—or, first of all, what

key the music was in. It took time and a lot of sweat. But I analyzed it

and before long I was playing with the musicians on the scene. I

listened to [Art] Tatum, Charlie Parker, [Thelonous Monk], Bud Powell

and many others and concentrated on Duke [Ellington] and Fletcher

Henderson for composition. Later I got scores and studied more extensive

things that take place in classical composition and started to practice

classical pieces on the piano, as I do now.

Abrams documents all his New York performances. Still, the decade between 1996 and Streaming

(Pi, 2006), a compelling triologue between Abrams, Lewis and Mitchell,

shows only one, self-released, issue under Abrams' name. As of this

writing, no releases were scheduled for 2007. "That's okay, Abrams says.

"I think things that are supposed to reach the public, eventually will.

I understand that people want to be able to hear whatever is happening

at any given time. However, the recording industry has ways that it does

things and sometimes this may not be consistent with what the musician

wants to do.

Business has a right to be whatever it is and the artist has a right to be whatever the artist wants to be. I also think the fact that musicians can do these things themselves today because of technology causes output to come out a little bit slower. But the quality is pretty much equal, often higher, than it used to be, because the musician can spend more time preparing the output. It's important for people to hear what I do, but the first point of importance is my being healthy enough to do it. I don't worry about whether it gets distributed right away.

"I always felt that you need to be about the work you need to do and that's to find out about yourself. That's pretty much a full-time job. You pay close attention to others, but the work that you have to do for yourself is the most difficult. I seem to move forward every time I reflect on the fact that I don't know enough. If you feel you have something, it's very important to get that out and develop it. Health is first. But your individualism I think is a close second.

Business has a right to be whatever it is and the artist has a right to be whatever the artist wants to be. I also think the fact that musicians can do these things themselves today because of technology causes output to come out a little bit slower. But the quality is pretty much equal, often higher, than it used to be, because the musician can spend more time preparing the output. It's important for people to hear what I do, but the first point of importance is my being healthy enough to do it. I don't worry about whether it gets distributed right away.

"I always felt that you need to be about the work you need to do and that's to find out about yourself. That's pretty much a full-time job. You pay close attention to others, but the work that you have to do for yourself is the most difficult. I seem to move forward every time I reflect on the fact that I don't know enough. If you feel you have something, it's very important to get that out and develop it. Health is first. But your individualism I think is a close second.

Selected Discography:

Muhal Richard Abrams/George Lewis/Roscoe Mitchell, Streaming (Pi, 2005)

Muhal Richard Abrams Orchestra, Blu Blu Blu (Black Saint, 1990)

Muhal Richard Abrams Octet, View From Within (Black Saint, 1984)

Muhal Richard Abrams, Mama and Daddy (Black Saint, 1980)

Muhal Richard Abrams, Levels and Degrees of Light (Delmark, 1967)

Creative Construction Company, Vol. 1 & 2 (Muse, 1970) Photo Credit: Courtesy of AACM

Muhal Richard Abrams Orchestra, Blu Blu Blu (Black Saint, 1990)

Muhal Richard Abrams Octet, View From Within (Black Saint, 1984)

Muhal Richard Abrams, Mama and Daddy (Black Saint, 1980)

Muhal Richard Abrams, Levels and Degrees of Light (Delmark, 1967)

Creative Construction Company, Vol. 1 & 2 (Muse, 1970) Photo Credit: Courtesy of AACM

Interview with Muhal Richard Abrams

This telephone interview with pianist, composer and bandleader Muhal Richard Abrams was recorded a few days before his 1996 orchestra concert at the Kennedy Center. That performance also marked the world premiere of an Abrams’ commission, Duet for Violin and Piano. Eighteen years later to the day, Muhal returned to the Kennedy Center, where I shot this pic at close of his concert.

Why don’t you tell us about the music you’re playing here this coming week?

Well, each piece is completely different. It’s original music; some older pieces and some newer pieces recently composed, of course.

How often does this orchestra perform?

This particular group hasn’t performed before. It’s a complete new setup.

For the commissioned work for violin and piano, you’ll have Regina Carter and Anthony Davis performing the premiere. Did you consider playing the piano part yourself?

I’d prefer to have someone else play it. I have quite a bit to do so I’ll be concentrating on the orchestra and the things I want to do there.

Did you write the piece with these two players in mind?

No. I never write with players in mind, except for the quality of player. So when I wrote it I didn’t have any specific players in mind, except for good players. And after I wrote it I decided who I wanted to perform it.

Have they rehearsed it yet?

Oh sure. They’ve been in rehearsal for quite a while.

Are there elements of improvisation, or is it strictly composed?

This piece is strictly composed. There’s a possibility there may be elements of improvisation, I have to talk to them about that. But in terms of the composed part, I’m sure they have that well in hand. If there will be any improvisation in that piece, I will allow them to interpret sections for themselves in order to develop any improvisational part.

You’ve been composing for more than 30 years now. Has your approach to it changed over time?

It’s constantly changing [chuckles].

In what way?

Well, it changes because you get different impressions at different times. You’re hearing other people do things, and you’re studying, you know, personal studies. So it’s constantly changing because you’re trying to improve it. And to learn from the environment itself, you know?

Tell me more about your personal studies. Are you studying technique, are you studying yourself or the world itself?

The world itself. Well, a little of all of it, actually. I don’t think you ever stop learning in terms of technical study. And self-study.

Can you give an example of something you’ve studied in the world or with other musicians and how it impacts on your own music or concept?

No, it’s nothing specific. It’s everything. It could be anything that might impress me. It can be any style of music.

At what point did you know that music would be your life?

Hm… [long pause]. I don’t know [laughs]. It just started to happen. I was quite young, of course.

This was in Chicago?

Oh yeah, sure.

Did you know Captain Walter Dyatt?

Sure. I knew him pretty well.

So I want to know more about that time in Chicago in the 50s. Walter Dyatt was there, you were there. Was Sun Ra around at that time?

Sure.

How involved were you with each other?

We were all on the scene. It was like a neighborhood, so to speak. Everyone knew everyone else and we were aware of everyone’s activities, and whatnot. We would perform in some of the same venues. It was a close community at that time.

You’ve been an important teacher for many musicians. Who were your mentors?

Two of my main mentors were the pianist and bandleader King Fleming, who’s still performing, and William E. Jackson who is now deceased. He taught me a lot about arranging music. They were my first real teachers, in terms of the approach I started to develop.

What inspires you outside of music?

Painting and visual art.

Anyone in particular?

No, all of the great masters; African artists, European artists. Chinese, Japanese, you name it. All art. My impressions of art and color, and rhythm and color have had a great impact on me in terms of music and art.

Have you ever composed for moving image, say film or video?

No. I’ve been asked that quite a bit, but no, I never have.

The reason I ask is that your music often evokes images for me and I wonder if there’s anything specific that you’re trying to convey, or is it just expressing a feeling inside of you?

Well, music has a basis that can sort of give impressions of drama and related type activities. And in my studies and observations, I more or less observe it all, especially functional music like movie music, so I guess some of it has to get into what I do, you know? Not as a deliberate situation. I don’t know, it’s a part of the music. And sometimes the impression is not to write a musical phrase. The impression might be to write a dramatic phrase. It’s very difficult to put into words, but it’s pretty close to what I could say concerning that question.

In recent years you’ve incorporated certain electronics into your music. Will you be playing those on stage?

Just a little bit.

How do you integrate them without them sounding inhuman? In other words, how do you make a machine sound natural?

I’m not trying to make it sound natural. I’m using it as an element of sound, you know? It’s just a part of the world of sound.

Do you hear sounds in your head that you cannot reproduce?

Sometimes. But it’s probably because I don’t have the instrument to produce it. Maybe the instrument is somewhere else in the world. Or maybe there’s a sound that I’m not sure what instrument could produce it, whether there is an instrument to produce the sound.

As the 20th century is ending, is it time to create a new language for music, new vocabulary?

Well, I don’t think you’re going to create a new language for music because I think music is far beyond that which we know at this time. We’re just discovering more about it. In terms of this age of mankind, I think it’s infinite enough and far enough ahead of us that we’ll just be discovering more ways to approach writing and performing and appreciating music. So I think it’s more a question of that rather than inventing a new music that is different from the basic element inherent in what we call music today.

Do you still record for two different labels; Black Saint and New World?

I regularly record for Black Saint. New World was a side project; a good one and most enjoyable one, of course. But my regular recording work has been with Black Saint, and still is.

The reason I ask is you’re an artist, you’re a composer and instrumentalist, but you also have a foot in the world of commerce in the music business. Do you have difficulty reconciling those two worlds?

No. I think that time and necessity teaches one to become a businessperson in addition to being an artist. Now that’s not true in all cases, but I think in my case it’s true.

Is it distracting for you?

No. It’s two different things in terms of times of concentration. Like this hour you concentrate on the contract. The next hour it’s time to rehearse the music. So you do each particular thing with respect to its time.

I guess now’s the time for a radio interview.

Yes [laughs]

Can we clear up one discrepancy in your bio, the year of your birth? Ekkard Jost writes that you were born in 1929. The Grove Dictionary says it’s 1930. Which is it?

Well you have to go by what I say: 1930. I don’t know where Ekkard Jost got that from.

You’re very well known among creative musicians, but not as much among the general public. Is recognition important to you?

Oh, I think I’m known among the general public, but I guess it depends what general public you’re talking about. The Top 40 public does not know a lot of musicians because the mass media is broadcasting more commercial music, which is ok. And I think that’s the reason. But, on the other hand, if you’re talking about a certain segment of the population, in terms of your comment, then I don’t know. I couldn’t say why it’s that way. So it depends who you’re talking about.

But I’m still wondering whether recognition is important to you?

Of course recognition is important to most artists, in the sense that you want people to hear what you do, because, after all, that’s why you do it. In other words, that’s why you perform it. You want to perform and give it to other people. So of course recognition is very important. But it’s like the end result. You know what I mean?

This interview was broadcast on WPFW-FM in Washington DC on Oct. 6, 1996.

Muhal Richard Abrams projects

AKAMU representation: worldwide + european exclusiveAs a leader:

Muhal Richard Abrams Experimental Band

Wadada Leo Smith - trumpet

Henry Threadgill - alto sax and flute

Roscoe Mitchell - saxes and flutes

George Lewis - trombone

Amina Claudine Myers - organ

Muhal Richard Abrams - piano

Leonard Jones - double bass

Reggie Nicholson - drums

Thurman Baker - drums and percussion

Muhal Richard Abrams Two Piano Ensemble

Laroy Wallace McMillan - reeds

Amina Claudine Myers - piano

Muhal Richard Abrams - piano

Leonard Jones - double bass

Reggie Nicholson - drums

Muhal Richard Abrams Quintet

Jonathan Finlayson - trumpet

Brian Carrott - vibraphone

Muhal Richard Abrams - piano

Brad Jones - double bass

Reggie Nicholson - drums

Muhal Richard Abrams Solo

Muhal Richard Abrams - piano

As a co-leader:

Muhal Richard Abrams - Roscoe Mitchell - George Lewis

Roscoe Mitchell - saxes and flutes

Muhal Richard Abrams - piano

George Lewis - trombone and electronics

Muhal Richard Abrams - Roscoe Mitchell

Roscoe Mitchell - saxes and flutes

Muhal Richard Abrams - piano

Muhal Richard Abrams: Think All, Focus One

A conversation at New Music USA

January 15, 2016—2:00 p.m.

Video presentations and photography by Molly Sheridan

Transcribed by Julia Lu

Although very early on in our conversation Muhal Richard Abrams adamantly denied ever being anyone’s teacher, I learned more during the hour I spent talking to him than I had in most of my music classes. And yet, I feel like it’s almost impossible to adequately communicate what it is exactly that I learned. At the risk of sounding like a Zen koan, that is precisely what I learned.

Let me attempt to explain. To Abrams, there are no boundaries. Any label we put on something—fixed composition vs. spontaneous improvisation, group vs. individual, even old music vs. new music—is artificial and limits possibilities. From his vantage point, all dualities are contained within each other. All improvisations are compositions and all compositions begin as improvisations. A solo performance can inhabit multiple personalities and an orchestra can be the embodiment of a pluralistic individualism. As for old and new, “None of it’s real because the situation that is characterized as old often times is revisited and found to be useful for some future purpose. And something new can be visited and found that is reminiscent of something that’s old.”

“The word jazz can be confusing,” Abrams points out. “But if we say music, it could be anywhere. It’s just music. The next question, what type of music? Okay. No type of music. Just sound.”

And indeed over the past seven decades, Abrams has created music that some listeners might categorize as blues, Latin, classical, and all kinds of jazz from swing to bop to free. He’s even experimented with electronic music.

“That came about because sound can be produced in any way that you feel that you’d like to produce sound,” Abrams explains. “It’s just electronic sound. … But sound, that’s the thing, because before music can be called music, it has to be harnessed and structured from sound. Music is a by-product of sound. Sound is the thing. Sound.”

While the music he has created is extremely individualistic, it is also the by-product of his humility and deep sense of community. I titled this feature “Think All, Focus One,” which is the name of one of his most fascinating explorations involving electronics, the closing track of an album released 21 years ago on the Black Saint label. It’s as succinct and definitive a summation I can conceive of for a creator whose life’s work embraces and reconciles such a broad range of aesthetics.

This Spotify playlist containing over seven hours of music by

Muhal Richard Abrams merely scratches the surface of his immerse and

highly varied discography.

Muhal Richard Abrams: Well, I think I was trying to be in any time. I was thinking infinitely, if that’s possible. And I believe it is. Whatever I said could be in any time because it applied to what I feel is your essence, your inner focus.

FJO: So many people describe music as either being “old music” or “new music.” But sometimes the lines can be very blurry. For example, in jazz, changes in style happened very rapidly; the transition from swing to bop and then cool and free all happened in a relatively brief period of time. Your music incorporates elements from all of these styles. For you, it’s all part of the language. And your music tells us that we can do it all.

MRA: Well, it’s partly human language. We can’t separate ourselves from other human beings because we are expressing ideas and all human beings express ideas. I may express it through a musical continuum and a poet may it express through literary continuums, but it’s basically the same thing because when we confront the whole idea of movement or rhythm, all these different sections or areas have rhythm in common, you know. And human beings have rhythm and breathing in common.

So, in reference to people saying this is old or this is new, if it’s old for you, then it’s old for you. If it’s new for you, it’s new for you. But those are just terms that are useful to describe the particular mood that that person or those people are feeling. None of it’s real because the situation that is characterized as old often times is revisited and found to be useful for some future purpose. And something new can be visited and found that is reminiscent of something that’s old. Take women’s fashion or men’s fashion. We see it every day. You know what I mean? And we certainly see it in music. Why is it that Beethoven and Bach are current and present today and valid today? Why is Duke Ellington still extremely important? When we view him as an individual creator, there’s a lot to learn. We’re observing an individual’s output, and I think the fact that we are all individuals for some reason or other is the basis of real education.

MRA: I expressed myself in the visual arts first, though certainly not long enough in terms of a practice. I was attracted to all of it at the same time. But I applied myself to the visual arts and then music took over. That’s it. It just took over.

FJO: Was there any kind of crystallizing moment of hearing something?

MRA: I think I started remembering something. I think that’s what it was. In the visual arts also, I was remembering something because it didn’t seem like I had to learn it. It certainly required practice, of course. Everything requires practice because if you don’t practice, then you’re kidding yourself, in terms of developing and receiving really great ideas. I started remembering things and my musical memory started to dominate. It’s the best way I can explain it. It just started to dominate, so I just put the bulk of the practice in music.

FJO: Was there a lot of music in your household when you were growing up?

MRA: I grew up in Chicago, and there was music all around. It was a blues center. I listened to all kinds of that. I grew up around Muddy Waters and all those guys. And there were a lot of great jazz musicians. And a lot of those great jazz musicians played classical music. So I was impressed with all of it. Then I got a chance to listen to regular so-called classical music. I was enjoying and appreciating that, and having the desire to learn how to compose all sorts of music because my training was like a street improviser. I learned to play standard tunes and what not like that. But I always held two situations at the same time: making up things and being with things that were made already. It all was happening at the same time.

FJO: One of the things that I find so fascinating about your development is that playing the piano and composing music are both things that you pretty much did without a teacher.

MRA: Oh yeah.

FJO: This is pretty extraordinary. Of course, there have been others who have done that, but there aren’t too many of them, especially not many who have taken it to the level that you have. But what’s ironic about that is that you have been an important mentor to so many other people, both your contemporaries and musicians from younger generations, yet you yourself had no such mentor.

MRA: I can certainly identify some people that I associated with that were older than I was around Chicago. I certainly learned a lot from them. But I don’t claim to be a teacher. I never have claimed to be a teacher. If someone claims that they’ve learned something from being close or around me or associated with me, that’s fine. Those kinds of things happen through association, but mentor or teacher? If people want to apply those terms, fine. But I don’t think of myself in that way. I love sharing and collaborating with people, young or old. There’s something to learn from each person’s individualism, and if I’m associating with you, then your individualism can tell me something that I don’t know anything about. And my individualism can possibly do the same for you, because we all, as individuals, have something that no one else has. As I tried to state earlier, I think that’s the basis of the real human education.

MRA: We have used the word jazz, but any type of description of music, especially the word jazz, can be confusing because, like we spoke of earlier, some people say they like the old or that this is new and the word jazz has stuck with a lot of people as a certain type of activity, so it can’t describe anything past that for those people. But if we say music, it could be anywhere. It’s just music. The next question, what type of music? Okay. No type of music. Just sound. You know, because that’s what it is. Sound. Before it’s even organized into any kind of continuum that we would call music, it’s just sound. As we speak here, I certainly feel that every serious practiced output that has come about since the beginning of time, is good—and valid. A style name limits the scope or the focus and that turns out to be unfair to quite a number of people.

FJO: Jazz has certain associations for people and so does classical. It was interesting to hear you say “so-called classical.”

MRA: It’s the same. You’re putting a restriction on a vast area of activity. And, by the way, you alluded to the fact that one could learn from the other. Classical music is the same thing. It’s written composition, of course, but the great composers did a lot of improvising, too. All of them. When you play their music, you can tell. It’s not just mechanical. Rachmaninoff sat down and played ideas at pianos. I’m sure he did that. Then he said, “Well, I’ll make this a piece.” Certainly Chopin must have done that. But they were well-trained musicians, so they knew how to handle the material of harmony, rhythm, and melody, because you hear all those things. It’s just too human in its feeling and its activity to be strictly mechanical. As a composer, if you give me a score pad I could just sit right now—I don’t need to have a piano or anything—and I can just write; I don’t have to know what it sounds like. I know how to structure it. That’s one way. If I sit down at the piano and start playing and say, “Yeah, I like this. I’ll write this down.” That’ll sound a little different. So I’m sure in their case, they improvised a lot of things. But it’s quite different from a person that has had the experience of improvising as a focus; theirs was compositional as a focus.

FJO: So to take an improvisation and turn it into a composition, the lines can often be very fluid and very blurry, as they ought to be. And I think they always were, as you’ve said. But what are things that make something that was spontaneously conceptualized in the moment into something that could theoretically be something that you’d want to repeat and do the same way other times, again and again? What gives it that essence of compositionality? How does it go from being an improvisation to being a composition?

MRA: I can’t speak for anyone else, but I think what I’ll say is probably pretty similar in each case. Some things you want to keep for several reasons, but one of the main reasons is that you learned something from doing this. You were enlightened by it. So you want to keep it because it might have constituted an area where you solved something that you might have been having questions about. Let me try this. Let me see what this is like. Oh, I think I’ll write it down. Sure.

FJO: So when did that first start happening for you?

MRA: It always happened.

FJO: But you said that when you first started making music, you were improvising.

MRA: But I was doing that too, though.

FJO: So you were writing stuff down? How did you come to learn music notation?

MRA: Well, I came to a point where I wanted to be more technically enlightened about composing, so I started to study on my own. I remember they had these harmony books. They’re teaching people harmony out of a book. I’ll just go buy the books, and I’ll read the books. And so I just see what it is. I didn’t need the teacher. No disrespect to the teachers, it’s just my kind of feeling. I’ve always had a kind of feeling that I could teach myself if I could find the information somewhere because I had the patience to spend the time to try and learn it no matter how difficult the learning curve.

MRA: Oh yeah, on the stage—listen, that was it! You didn’t go up on the stage unless you could really complement the scene.

FJO: So how did those opportunities come about? How did Max Roach learn about you?

MRA: Mostly through Joe Segal, the person who had a venue called the Jazz Showcase. He had it at different clubs and things, but he really started with having jam sessions at Roosevelt University, so we would all participate in jam sessions. Then he started to bring in national and international entertainment and would hire us as sidemen for the people that were coming. That’s how that came about.

FJO: You attended Roosevelt briefly.

MRA: Very briefly. I was searching for a learning path. However, I found that I didn’t really need that either.

FJO: Well, there’s a quote from you I came across where you said you wanted to go there to learn about the music, but what they were telling you about the music wasn’t the same as what you were experiencing.

MRA: It was very basic, and I was performing more advanced type things than they were. But let me be fair to them. You know, if teachers are going to teach, they start with the basics. I don’t blame them for not having different information than I had from actual playing in the street. But, like I said, what I did decide is that the same literature that they had there to teach me, I could just get the literature and teach myself. That way, the pace by which I would learn the literature could be a pace that I would set. It would take me six months to learn that a triad has a positive and a negative, but you could learn that in two days.

FJO: I wish there was some recorded documentation of your performances with Max Roach.

MRA: No, we didn’t record. I performed with him, and it was great. That was some education. That was like a Ph.D.

FJO: And Dexter Gordon?

MRA: Same. And Sonny Stitt.

FJO: I’m also intrigued that you worked with a really great singer who’s not as well remembered now as she should be—Ruth Brown.

MRA: Yeah. Believe it. And Percy Mayfield. You remember Percy Mayfield’s “Please Send Me Someone to Love”?

FJO: What do you feel you got from working with Ruth Brown?

MRA: Her feeling was so great. It was a challenge to present the right complement every night. Just basic things. But my experience in Chicago around blues and different forms like that came in handy. I was ready to do it.

FJO: One thing that I hear, and I was wondering if you will agree with me or not, is I find your piano playing so melodically rich; the melodies just soar. It almost sounds like singing at times. Some pianists are really rhythmic, or percussive, or really big on harmonies, but I feel that your pianism is a very melodically flowing pianism.

MRA: Yeah, I guess it is. I don’t know. I feel a lot of worlds all at the same time and respect for a lot of worlds, even the percussive world sometimes. I do that, too. Actually, I think what it is for me is I’m composing. I think it’s basically that. I’m composing. And for me, there are two ways of composing: writing it on a paper and improvising. So when I’m playing the piano, it’s improvised composing or composed improvising. The memory of what you’ve been and what you are and whatever you will be comes out.

FJO: None of what you did with Max Roach, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Stitt, Percy Mayfield, and Ruth Brown got recorded. But you did record with a group called Modern Jazz Two + Three.

MRA: Oh yeah. It was the first recording I ever made.

FJO: I’ve been trying to track down that record for a very long time, but somebody posted one of the tracks on YouTube—a composition of yours called “Temporarily Out of Order.”

MRA: George Coleman reminded me of that piece a couple years back. He used to play it. He sang it. I’m surprised that he remembered it.

FJO: It’s got a great melody and some interesting chord progressions, but what strikes me about it is how different it is from what you started doing very soon afterwards with the Experimental Band. I don’t know the whole album, but judging from that one track, wonderful though it is, it is not experimental music. So what led you to go from straight-ahead type playing to wanting to really be open to the full range?

MRA: I was always that way. It’s just that I came to a point where I needed to express the more open type approach. You know, you evolve. So I came to that point and, because I was seeing it all the time through writing original pieces, I just decided to open it up. There were a couple of musicians around Chicago who agreed with that. And we just started opening things up.

FJO: But what’s interesting about what happened in Chicago with you and the other musicians there is that it was very different than similar developments with free music in New York and Los Angeles at the time. While you were opening things up, as you say, you remained mindful about earlier history and also about contemporaneous popular music. It was never experimental for the sake of being experimental. It was really about just having this open view, as we’ve been saying before, of being mindful of the past, the present, and the future all at the same time rather just making music for the future and forgetting about the past.

MRA: Well, I don’t even think that’s possible. People could fancy themselves doing what you just said, but I think basically people were trying to be composer-improvisers and the main generator was the individualism of each person. That is very important because I believe that individualism resulted in a scene with quite a few very strong individuals, like those that came out of the AACM. They were very strong individuals because they were encouraged and presented with a situation that asked them to present their individualism in concert. So there was a constant challenge to meet those challenges.

FJO: Since the past, present, and future are all a continuum, I’m going to jump decades ahead and then we’ll jump back. In the ‘80s you released a record with a very interesting title—View from Within. There’s an incredibly wide range of music on there. One track is Latin music. Another one is a full-on Chicago blues.

MRA: That’s right.

FJO: There’s also material on there that sounds like classical music, as well as stuff that sounds like straight-ahead jazz. But what’s interesting is that you describe all this as a view from within as opposed to the view from outside.

MRA: I’ve kept a better balance by respecting other things. Somehow it balances me to do that. Learning from another individual’s information—that’s extremely important.

FJO: Now in terms of balancing, to bring it back to the 1960s, your second LP—Young at Heart/Wise in Time—is like two completely different records. You reminded me of it when you were saying that sometimes you also get all rhythmic and percussive. There are sections on the ensemble side, Young at Heart, that are throbbing and really intense, especially in the interplay between you and the percussionist, Thurman Barker. But the other side, Wise in Time, is a beautiful, lush, at times almost Rachmaninoff-esque piano solo.

MRA: Well, listening to people like Art Tatum, and also Rachmaninoff, it was sitting down getting a feeling of how the piano sounds as a complement to all these people. That’s all it was: Rachmaninoff, Chopin, Art Tatum, Monk. Just sitting down and being musical in that way, to explore how the piano can sound. I think that’s probably what happened in that instance.

FJO: It’s a perfect listening experience on an LP because you have the two sides, whereas on a CD or an online stream you don’t get that same sense of duality.

MRA: It was limited, but yet not.

FJO: Now, in terms of the composition-improvisation divide, how much was worked out in advance and how much was completely spontaneous.

MRA: The piano solos were improvised. Period.

FJO: Completely improvised?

MRA: Yes, that’s what I’m saying—just sitting down and respecting the fact that it’s important to make an effort to be musical and to explore, as best you can, how the piano can sound. So that’s a compliment to Rachmaninoff, Beethoven, Chopin, Monk, Duke, and also one of my first influences on piano, King Fleming. I just mentioned him because he needs to be mentioned. He was the first pianist I heard who was a jazz pianist and was classically trained. The way he played the piano, he was aware of the piano sounding in a combination of manners—jazz and classical, all at the same time. He listened to a lot of people who were like that: Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum. But I think King Fleming’s influence as to how a pianist should sound hit me first and early, because he was the first pianist that I’d gotten close to who could play like that. And he had a large band, and the arranger who orchestrated for that was a trumpet player, Will Jackson. I need to mention him, too. I learned a great deal from both of these gentlemen. I learned performing in a jazz band from King Fleming and writing for a jazz band from Will Jackson. They’re both deceased now, but I think that other people should know about them.

FJO: Curiously, on your first recording date as a leader, in addition to playing piano, you also played clarinet.

MRA: Well, I just feel musical with anything that I would apply myself to. I wanted to play the clarinet, so I just picked up clarinet and respected the fact—I practiced clarinet. I certainly didn’t stay with it as long as I could have, but I stayed with it long enough to do what I needed to do in terms of when I did perform with it.

FJO: And I imagine that it gave you other ideas that you might not have gotten on the piano, because of the different physical relationship it requires, producing sound with your breath.

MRA: It’s a different feeling because it’s a different mechanical manipulation. Sure.

FJO: This multi-instrumentalism is a hallmark of AACM members. In terms of the beginnings of the AACM, you were its founder as well as its first president. You were the person who brought these people together. But notions of hierarchy seem antithetical to you, as well as to aesthetics of the AACM overall; so how did that work?

MRA: There was no hierarchy. We all agreed to agree; sometimes we agreed not to agree. But we certainly agreed to contribute to each other’s efforts to express one’s individualism. And that was the basis of it.

FJO: So how did that whole thing come about?

MRA: Well, I had organized a band called Experimental Band, which was a precursor of the AACM. I needed a place to try out some of the newly learned things that I was educating myself about in terms of music through my studies. I needed a place to express those things. They were more open things. They weren’t things that you’d play in jazz clubs. So I organized what I called the Experimental Band. The musicians could come and experiment with composition and improvisation. We were of like minds. And so from there we came to a point where I collaborated with three other musicians to create a formal association based on the same idea. That’s how the AACM came about.

FJO: It began from a group, but it’s not a performing group per se. It’s sort of a composer collective, but it operates in a different way than most composer collectives. It came from this idea of not playing in clubs and finding alternative venues for this kind of music, but it’s not a venue in and of itself.

MRA: We presented our own concerts. We also created the venue for producing the music or, rather, for presenting the music. We created a venue through just renting a space and presenting the concerts. In other words, it was a total effort. We weren’t looking for a place to perform the music. We created a place to perform the music. And so it was all one.

FJO: There are two things that could be strong motivators for doing this. One is what you had said about making music that wouldn’t work in a club. Or maybe it was music that the club wouldn’t want necessarily because it didn’t fit with the definition of music the people at the club were interested in presenting or that they felt the audience expected from that club. But there’s also another motivator which is about creating a space for the kind of listening that is most appropriate for this music. To really be able to focus on it requires a different kind of space than a club.

MRA: Well, no. Not really. Let me say this. It could have been played in clubs. In fact, we did. We were in residence every Monday night at a club. We played the way we played, and the place stayed packed with people who wanted to hear what we were doing. So it could be played in clubs. It was just that it wasn’t regular gig music. People come to hear standard things. But certainly we played in several clubs and the night we played was the night that people would come to hear what we would do. So it could be played anywhere. In Chicago, it was like that. It could be played anywhere in the city.

FJO: The reason I wanted to talk about it now is because the world 50 years ago is quite different from the world today in terms of venues. Nowadays, people who doing the most experimental kinds of things want to go back and play in clubs and suddenly clubs have become an even more tolerant space; whereas a half century ago there were more limits on what you could do. I think the notion of what is possible in a club now is very different.

MRA: Certainly you go to clubs here in New York now and you might hear anything because it’s wide open to individualism. I think that is the real factor that brought this type of situation to the fore, because individualism is not something that’s strange. You know what I mean? People today expect to hear an individual doing an individual type of presentation.

FJO: I’m also curious about this in terms of recording and how most people experience music. We didn’t really talk about listeners so much in this, like the ideal listening experience for somebody hearing what you or what other people associated with the AACM do. I don’t expect you to speak for the others, but to speak for yourself. What is an ideal listener in terms of focus on the music? Should the person be paying full attention? Could the music just be in the background? So many people nowadays walk around wearing headphones and listening to music as they’re going through their daily routines. Is that an okay way to experience this music versus being completely focused on it and having it speak to you— and have only it, ideally, speak to you?

MRA: Well, let me ask a question. How many different ways can a person decide to concentrate? I think that question asks many other questions. If a person is concentrating and seriously listening, it could be through earphones walking down the street. I wouldn’t even attempt to try to say what would be the ideal situation or where a person should listen to music. I think they make that choice. But the fact that there are people who seriously want to listen to certain kinds of music—well, they’ll do it anywhere, even through earphones. You know what I mean? They’ll do it anywhere, if that is convenient for them, and they’ll just do it whenever they find a convenient time to do it. I think that’s the answer, because people are listening to all sorts of things and I think a lot of them are quite eclectic, too. I mean, they’re listening to all kinds of stuff.

FJO: Well, if they listen to you, they’ll be hearing everything.

MRA: [laughs] I don’t know about that.

FJO: To bring it back to those early AACM years, you were such an important voice in the Chicago music scene, and yet in the mid-1970s you moved to New York City and have been here ever since. What made you uproot yourself?

MRA: What can I say? It was just time to move. Chicago is a great place, but New York is a different kind of place. The intensity and the challenge is quite constant. I guess it was just time for me to do that. You’re swimming in a pond and sometimes you go where it feeds into the ocean.

FJO: You came to the ocean, but a lot of the things that you did here were similar to what you had done there. In New York City, you were a major force in developing the loft concert scene. So to some extent you brought a Chicago idea to New York.

The

somewhat cryptically titled 1-OQA+19, Muhal Richard Abrahms’s first

album as a leader recorded in New York City (in November and December of

1977) and featuring four other AACM alumni (Anthony Braxton, Henry

Threadgill, Steve McCall, and Leonard Jones), is definitely a

continuation of the ensemble music he was involved with in Chicago.

MRA: Well, I don’t know about that, but I didn’t intend to function in any other way except for the way I was functioning. I have to include other people, of course, but we all came to do what we do: presenting concerts, same as we’d been doing in Chicago. Now we’re in the ocean; we do it according to this space.

FJO: It was such a vital time for this music, but now, 40 years later, a lot of that scene has disappeared or has changed very fundamentally. Back then Roulette was a loft. It was Jim Staley’s apartment. Now it’s an official, street-level concert venue. It’s amazing that we finally have such a venue that’s dedicated to new, exploratory music. That’s wonderful. But I also think we might have lost some of the personal, home-grown, DIY quality that we once had when so many of these concerts were taking place in people’s own homes. With the way the real estate market has played out, the way demographics have changed, we probably can no longer have such a scene in quite the way that we had it back then.

MRA: You hit it on the head when you said real estate market. There’s a reason for that. The real estate requirement for higher rents caused people to just give it up in terms of maintaining those venues. It happened to quite a few, without naming them, as I’m sure you know. But with Roulette, his [Jim’s] perseverance in terms of what he wanted to do paid off, which is great.

FJO: But what’s interesting is now he’s got this great space, but it’s not a loft anymore. It’s something else. It’s a fabulous something else, but it’s a different listening modality. It doesn’t have the same intimacy. It can’t.

MRA: Well—and I’m sure you know this—you have to upgrade. You’re asking people for money, so you have to put it on a level where you can use that kind of money you’re asking for, if you’re fortunate enough to make those kind of contacts. But I think the music itself or the idea of the music and the presentation of the music hasn’t changed. At Roulette, they present a great variety of musical approaches. If anything, he expanded, but I suppose it has to be what it is in terms of physical structure in order to accomplish what it is that they want to do. If you do something for ten years, you say, “I want to do it again for the next ten years; however, I want to levitate and do it like this.” Things just have to grow. There’s a nostalgic feeling in reference to vinyl records and CDs, there’s a nostalgic feeling for the lofts and whatnot like that, but I think that the musical content in the lofts is still at play. It’s just not in the lofts.

FJO: So, for you, where are the ideal places where you would like to either play music or have your music played by others to be heard?

MRA: Oh, I don’t have any except for the AACM concerts. We’re still producing those concerts. But Roulette is a good place for having things done that are not AACM-type presentations. And Tom Buckner’s series does quite a few good things. I mean, I like seeing some things on his series that otherwise maybe wouldn’t be on an AACM series, some compositional things. I’ve done some things on his series. There are a few venues in Brooklyn. I don’t function in Brooklyn, so I’m not in touch with those other venues, except for Roulette. But they have other venues around that seem to be pretty consistent in presenting written and improvised music.

FJO: To bring it back to your music again, my all-time favorite piece of yours is The Hearinga Suite. I feel it has a foot in both of the worlds we’ve been talking about: that of composed improvisation and improvised composing—so-called classical music and so-called jazz. It’s a fluid interplay that is both at once—informed by both, yet neither. It’s its own thing. So I wanted to talk to you a bit about it and how it came into being. Do you feel it represented a turning point in your music because of its scale, both in terms of its length and the number of players involved in it?

MRA: No, I was always like that. I mean, it’s just happening. It’s a project that I did at that time, but in terms of the musical ingredients, they were always there. The idiom, the compositional makeup of the piece, that’s just me in that.

FJO: What does the word Hearinga mean?

MRA: It’s an expression, like a song—Hearinga—like a name or something. It has nothing to do with the music, but it’s an expression that is used to speak in reference to the music.

FJO: I thought it was about hearing, because it’s “hearing”-a. I thought you gave it the title as a way to focus listeners on hearing this multiplicity.

MRA: That’s great, because certainly I intended for the title to provoke thought and wonder. But the intention was to bring a thought from the listener that would require the listener to deal with the listener’s self. You see what I’m talking about? It’s hard to explain, but I mean—it’s like I’m thinking and I’m looking at the table. I’m thinking about the table, and all of a sudden I’m seeing shapes within myself and getting questions and answers about something that I might not have been thinking about at all.

FJO: The individual movements go in so many different directions like, for example, “Conversations with the Three of Me.”

MRA: Oh yeah, that’s the piano thing.

FJO: I love that title, but there are so many more than just three of you.

MRA: Well, hey, right. But that’s rather metaphysical and also quite mundane at the same time. I used three improvised approaches.

FJO: So what are they?

MRA: There are three different moods, but they’re not moods that are separate. They’re played like a sonata. You play this slow, you play this a little fast, and then you play this fast. But it’s not exactly that type of thing because everything is improvised on the spot. The name came after the performance. All names come after the performances.

FJO: You also use a synthesizer on it.

MRA: That’s one of the moods.

FJO: Certainly there are things that can be done on synthesizers that are impossible to do on a piano or with other instruments. Even by the mid-1980s when you made this music, electronic music was largely a new sound world. So what brought you to use synthesizers, and do you feel that changed your language in any way, musically?

MRA: Well, let’s think of it this way: we’re actually talking about sound. We’re talking about music, but we’re talking about sound. So that came about because sound can be produced in any way that you feel that you’d like to produce sound. And that’s it. It’s just electronic sound. That’s the difference. There’s electronic sound, then the two piano sounds—three moods. Three of me, you know, a conversation with the three, so there’s an electronic part, and then there’s two different moods for the piano. So that’s the conversation, you know what I mean? But sound, that’s the thing, because before music can be called music, it has to be harnessed and structured from sound. Music is a by-product of sound. Sound is the thing. Sound.

MRA: Well again, here I have a provocative statement which has nothing to do with describing the music. It’s a statement that is intended to provoke, but not for control or anything. It’s just meant to provoke. It’s a feeling that comes together in that statement. You know what I mean? Think all, focus one. And I know what I get from it, but I don’t know what you might get from it.

FJO: Well what I think I got from it is that there’s all sound out there available to you, and you should be mindful of all of it: all styles, all possibilities of what you’re doing on any instrument, the whole breadth, the whole line between complete spontaneous improvisation to fully worked-out composition, as well as the rhythms and the melodies of all cultures. But despite thinking of all of that, you must be an individual.

MRA: That’s very good. That’s a nice compliment to the title, I must say.

FJO: Now when you write music for other people to play—like, say, the music you’ve composed for groups like the Kronos Quartet or ETHEL who performed a piece of yours for baritone and string quartet with Thomas Buckner, or the orchestra pieces you’ve written that have been performed by the American Composers Orchestra or the Janacek Philharmonic—these are situations where the musicians are working from written musical scores and they are performing this music without you. I imagine there is no improvisation in any of this music.

MRA: No. It’s written.

FJO: How does it feel to be apart from the music and for it to be fixed in that way?

MRA: Well, I’m improvising all the time, and I’m composing all the time. It’s the same thing. It’s the application that’s different. I am applying the approach to this orchestra with a written presentation, but it’s the same process. The difference is in the sense that I can make a certain kind of a texture with fifty strings. Four French horns can make a certain kind of texture. So I’m dealing with respect for the orchestra. That’s a component. I have elected to respect this instrument called the orchestra. And the possibilities of sound that can be gotten from treating it in a certain compositional manner.

MRA: I insist on it.

FJO: And you’ve performed as a sideman with others and you bring your individualism to them.

MRA: That’s right.

FJO: But when you’re writing a piece for orchestra, the whole idea is that it’s all on the page. They’re following the notes, and then they’re following the conductor’s interpretation of those notes. There’s a lot less room for self-expression.

MRA: Well, but there’s room for self-expressions, plural. You follow what I mean? People who are adept at playing classical music, I mean really great orchestra people, interpret musical symbols in a manner that can conjure up all sorts of pictures and panoramic images in terms of what you feel and what you hear when you hear a piece played by a really good orchestra. The way they interpret what you put down, that’s another element. You’re getting a plural of individualism, a pluralistic individualism, as a result of all these people playing together and playing with each other. There’s something that happens with them. There are certain people that couldn’t play with them because they wouldn’t be able to transfer that, they maintain the orchestra feeling for whatever is going on. It’s very important to them. In those great orchestras, it’s very important what happens among them. And that’s the other element. See? So you’re getting this plural individualist situation that goes on with them. It’s hard to explain because I think that the whole situation of individualism is transferable in terms of what a situation might be in terms of numbers of people.

FJO: So would you be okay with them taking a lot of liberties with something you’ve written down? How much can they change it and have it still be your piece? How much give and take is there in that process?

MRA: But the orchestra doesn’t change. The conductor might want to—

FJO: Speed it up?