SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

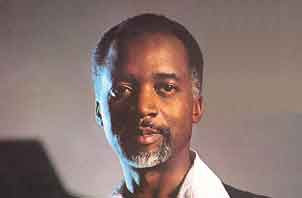

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SPRING, 2016

VOLUME TWO NUMBER THREE

WAYNE SHORTER

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LEO SMITH

March 26-April 1

AHMAD JAMAL

April 2-8

DIONNE WARWICK

April 9-15

LEE MORGAN

April 16-22

BILL DIXON

April 23-29

SAM COOKE

April 30-May 6

MUHAL RICHARD ABRAMS

May 7-13

BILLY HARPER

May 14-20

SISTER ROSETTA THARPE

May 21-27

QUINCY JONES

May 28-June 3

BESSIE SMITH

June 4-10

ROBERT JOHNSON

June 11-17

LEO SMITH

March 26-April 1

AHMAD JAMAL

April 2-8

DIONNE WARWICK

April 9-15

LEE MORGAN

April 16-22

BILL DIXON

April 23-29

SAM COOKE

April 30-May 6

MUHAL RICHARD ABRAMS

May 7-13

BILLY HARPER

May 14-20

SISTER ROSETTA THARPE

May 21-27

QUINCY JONES

May 28-June 3

BESSIE SMITH

June 4-10

ROBERT JOHNSON

June 11-17

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/ahmad-jamal-mn0000127369/biography

AHMAD JAMAL (b. July 2, 1930)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

One of the most individualistic pianists, composers, and arrangers of his generation, Ahmad Jamal's disciplined technique and minimalist style had a huge impact on trumpeter Miles Davis, and Jamal is often cited as contributing to the development of cool jazz throughout the 1950s. Though Jamal

was a highly technically proficient player, well-versed in the

gymnastic idioms of swing and bebop, he chose to play in a more pared

down and nuanced style. Which is to say that while he played with the

skill of a virtuoso, it was often what he chose not to play that marked

him as an innovator. Influenced by such pianists as Errol Garner, Art Tatum, and Nat King Cole, as well as big-band and orchestral music, Jamal

developed his own boundary-pushing approach to modern jazz that

incorporated an abundance of space, an adept use of tension and release,

unexpected rhythmic phrasing and dynamics, and a highly melodic,

compositional style.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on July 2, 1930, Jamal was a child prodigy and began playing piano at age 3, discovered by his uncle. By the time he was 7 years old, Jamal was studying privately with Mary Cardwell Dawson, the founder of the National Negro Opera Company. An accomplished musician by his teens, Jamal performed regularly in the local jazz scene and in 1949 toured with George Hudson's Orchestra. After leaving Hudson, he joined swing violinist Joe Kennedy's group the Four Strings, with whom he stayed until Kennedy's departure around 1950.

After leaving the Four Strings, Jamal relocated to Chicago, where he formed his own group, the Three Strings with bassist Eddie Calhoun and guitarist Ray Crawford. The precursor to the later Ahmad Jamal Trio, the Three Strings would, at different times, include bassists Richard Davis and Israel Crosby. During a stint in New York City, the Three Strings caught the ear of legendary Columbia record exec and talent scout John Hammond who signed the group to the Columbia subsidiary Okeh in 1951. During this time, Jamal released several influential albums including Ahmad Jamal Trio Plays (also known as Chamber Music of the New Jazz ) on Parrot (1955), The Ahmad Jamal Trio on Epic (1955), and Count 'Em 88

on Argo (1956). Some of the landmark songs recorded during these

sessions included "Ahmad's Blues" and "Pavanne," both of which had a

profound impact on Miles Davis, who later echoed the spare, bluesy quality of Jamal's playing on his own recordings.

In 1958, Jamal took up a residency in the lounge of the Pershing Hotel in Chicago. Working with bassist Crosby and drummer Vernell Fornier, Jamal recorded the seminal live album, Ahmad Jamal at the Pershing: But Not for Me.

Comprised primarily of jazz standards, including his definitive version

of the buoyant Latin number "Poinciana," the album showcased Jamal's

minimalist phrasing and unique approach to small group jazz,

emphasizing varied dynamics and nuanced shading as opposed to the high

energy freneticism commonly associated with jazz of the '40s and '50s.

Though somewhat misunderstood by critics at the time

who did not fully appreciate the inventive qualities of Jamal's

playing, the album proved a commercial success and remained on the

Billboard album charts for over two years -- a rarified achievement for a

jazz musician of any generation.

The smash success of Ahmad Jamal at the Pershing: But Not for Me

raised the musician's profile and allowed him to open his own club and

restaurant, The Alhambra, in Chicago in 1959. During this time, Jamal released several albums on the Argo label including Ahmad Jamal Trio, Vol. 4 (1958), Ahmad Jamal at the Penthouse (1960), Happy Moods (1960), Ahmad Jamal's Alhambra (1961), and All of You (1961). Unfortunately, The Alhambra closed in 1961. The following year, Jamal disbanded his trio, moved to New York City and took a two year hiatus from the music industry.

In 1964, Jamal returned to performing and recording. Working with a new version of his trio that included bassist Jamil Nasser and drummer Frank Gant, with whom he would work until 1972, Jamal recorded several more albums for Argo (later renamed Cadet) including Naked City Theme (1964), The Roar of the Greasepaint (1965), and Extensions (1965), Rhapsody (1966), Heat Wave (1966), Cry Young (1967), and The Bright, the Blue and the Beautiful (1968). Also in 1968, Jamal made his Impulse Records debut with the live album Ahmad Jamal at the Top: Poinciana Revisited. This was followed by several more Impulse releases including The Awakening (1970), Freeflight (1971), and Outertimeinnerspace (1972), both of which culled tracks from his appearance at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1971. These albums found Jamal moving toward an expansive, funk-infused style, sometimes playing a Fender Rhodes electric keyboard. Also during the '70s, Jamal

moved to the 20th Century label and continued to release a steady

stream of albums that attracted both hardcore jazz and crossover

audiences. Of his '70s albums, both Genetic Walk (1975) and Intervals (1979) made the R&B charts.

The '80s continued to be a productive time for Jamal, who kicked the decade off with such albums as Night Song on Motown (1980) and Live in Concert Featuring Gary Burton (1981). After signing with Atlantic, Jamal released several well-received albums that found him returning to his classic, acoustic small group sound including Digital Works (1985), Live at the Montreal Jazz Festival 1985 (1985), Rossiter Road (1986), Crystal (1987), and Pittsburgh (1989).

The '90s also saw a resurgence in interest and acclaim for Jamal,

who was awarded the American Jazz Master Fellowship by the National

Endowment for the Arts in 1994. Though he never stopped interpreting

standards, Jamal utilized his own compositions more and more as the decades passed. During this period, he delivered such albums as Chicago Revisited: Live at Joel Segal's Jazz Showcase on Telarc (1992), Live in Paris '92 on Verve (1993), I Remember Duke, Hoagy & Strayhorn on Telarc (1994), as well as a handful of superb releases for Birdology including The Essence, Pt. 1 (1995), Big Byrd: The Essence, Pt. 2 (1995), and Nature: The Essence, Pt. 3 (1997).

In 2000, Jamal celebrated his 70th birthday with the concert album L'Olympia 2000 (2001), which featured saxophonist George Coleman. He followed up with In Search of Momentum (2003), After Fajr (2005), It's Magic (2008), A Quiet Time (2010), and Blue Moon: The New York Session/The Paris Concert (2012). In 2013, Jamal released the album Saturday Morning: La Buissone Studio Sessions, featuring bassist Reginald Veal and drummer Herlin Riley. Also in 2013, Jamal opened Lincoln Center's concert season by performing live with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra.

http://jazztimes.com/articles/14082-ahmad-jamal-walking-history

Ahmad Jamal: Walking History

July/August 2003

Ahmad Jamal is relaxing in the poolroom-or rather, the large room that contains a swimming pool-abutting his otherwise modest, tidy home in the rolling hills of upstate New York. The rewards of well over 50 years at his craft are earned and appropriate; his stately demeanor seems at one with his comfortable surroundings. He is gracious, offering fruit-flavored soda or water, and personable. He repeats his interviewer's name often when answering queries like, after a lifetime's worth of style-Ahmad Jamal's never-ending momentum developing and legend-crossing experiences, would he ever write an autobiography?

"I doubt it," he laughs. "I don't have to write it. I live it every day, Ashley. Every single day, every minute."

The white-bearded, 73-year-old, Pittsburgh-born pianist is in no mood for resting on laurels or looking back. "I'm a busy person. I'm always doing things. My life is very interesting to me-I'm making new discoveries, musically and otherwise every minute, every second. There's a mystery to this life, there's a mystery to music, there's a mystery to writing, and you have to try to unlock them. I'm still unlocking, much to my delight."

That which drives and delights Jamal has taken musical form on a new, energetic album, In Search Of: Momentum [1-10] (Dreyfus), which many jazz-watchers already hail as his best in decades. "One of the most fiery and inspired of Jamal's career," argues Allmusic.com, "[a] more percussive style is in evidence...in a modern version of something that unites McCoy Tyner's Coltrane period with the barrelhouse." It's an accurate assessment. From its dynamic opening, leading immediately to equal-footed interplay from drummer Idris Muhammad and bassist James Cammack, the trio-charged album easily stands as one of the year's most compelling.

Here's how Jamal, ever forward-looking, measures his own satisfaction with his first studio effort in years. "I have gone back and listened to this present CD quite a few times, much to my surprise. I usually don't do that. There are some interesting things on there-the title track, 'In Search Of,' the ballad 'Should I' and 'Whisperings.'" Of the last title-the album's lone vocal track featuring the recently deceased gospel and jazz singer O.C. Smith-Jamal adds: "That probably is one of the last records that O.C. made. He was one of the great 20th century voices, a phenomenal singer. A lot of people don't know he succeeded Joe Williams in the Basie band. They know him by the hit 'Little Green Apples.'"

Jamal also highlights one of the album's most dramatic, suitelike tracks. "I particularly like 'I'll Take the 20.' Yeah, I like the structure and what we're doing on that one...."

Jamal describes his group not as a "trio" but as a "team." "James has been with me 22 years; Idris has been with me off and on for the last five. We have a lot of fun when we work and a wonderful relationship. Good or bad, mistakes, no mistakes. What we do equals fun. It's a fun happening every time we go on stage. If you're enjoying yourself, you're going to have a lot of commerce."

That commerce-artistic or economic, both definitions work in Jamal's case-is just one happy consequence of the career choices he can now afford to make for himself. "When I was 27 I was in the development years: trying to keep a group working, raising a family and trying to figure out what all these obstacles are about when life presents them and trying to overcome them. Now I'm sort of on a vacation from all those things. Now I have time to develop in areas that I couldn't develop before."

Today, Jamal will record only if the maturity of the music demands it: "Those are the key factors in determining when I'm going to record: new material and if I have lived with the material long enough." He tours only for a set period at a time ("I'm still basically the same as before: I'll be out for no more than six weeks") and carefully selects where and how he travels. "I try to plan an intelligent itinerary for myself as well as my men and make conditions that are conducive to success. Hotels, venues, promoters-you have to work with people who like to work with you."

Even Jamal's choice of his Paris-based label results from a go-with-what-you-know approach. "Jean-Louis [Dreyfus, head of Dreyfus Jazz and Birdology] is a real genuine record man, which you don't run into too often, the same cut of cloth as Leonard Chess-whose company I helped build-and [Atlantic Record's] Ahmet Ertegun. He's a music man, a record man-he's done some compilations that nobody else is doing: Don Byas, Billie Holiday. I'm very comfortable with that. Those are the people that I grew up around."

Familiarity-a guiding factor in Jamal's current path-certainly steers his conversation as well. In sharing his own history, what initially seemed reluctance ("I'm a look-aheader; I don't look back too much") becomes a trickle as the dialogue develops, then an outpouring of random recollections. His first professional forays around the Midwest while still a teenager. His extended run at a Chicago hotel, signing with Chess Records and rocketing to renown with a best-selling album that, as it turned out, offered only a scant selection of a mother lode of recordings from that residency. ("I only picked eight out of the 43 tracks for the live At the Pershing album.") His early start as a piano prodigy in Pittsburgh, meeting and urged on by Art Tatum.

Jamal invokes his hometown with a smile, proud of many tributes received- "It's a mutual admiration society; they've honored me, and I've honored them. I produced a CD called Pittsburgh that's used in the science museum"-and in being part of the city's long musical tradition. Jamal offers his oft-spoken litany: "You're talking about Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey, Roy Eldridge, Dodo Marmarosa-who is forgotten-Johnny Costa, who remained in Pittsburgh all his life, and when people watched Mr. Rogers on TV, they heard Johnny playing piano. Mary Lou Williams, Erroll Garner, George Benson, Stanley Turrentine, Earl Wild. That's what my hometown gave me: a rich legacy."

An avid record collector during his teen years, Jamal sent away for what he could not find in Pittsburgh. "We had to send for them mail order. I did all my collecting in my formative years, which would have been in the '40s and '50s. I was real eclectic. Georgie Auld and Boyd Raeburn recordings with Erroll Garner. Savoy records with Don Byas. Those early things Martial Solal did for Contemporary. The old Comet 12-inch masters with Art Tatum and Tiny Grimes and Slam Stewart, and Nat [Cole], and Lester Young playing 'Body and Soul.' Lucky Thompson, all that kind of stuff."

His prized collection now resides safely with Jamal's brother in Pittsburgh. Does he pull the old 78s out when visiting? "No, very rarely-now it's even hard to get a turntable." But, he adds philosophically, "there's no such thing as old music. It's either good or bad."

So much has been said of Miles Davis and his embrace of Jamal's '50s sound that it seems fitting to ask what the pianist thought of the trumpeter.

"Well, I was a great collector of Miles' recordings going back to the Capitol years. We grew up listening to each other, no question about it. We had a quality relationship, not a quantitative one, not one that was full of a lot of hours spent together. We were always too busy to hang out!"

In his autobiography, Davis made much of catching Jamal at the Pershing in 1953. Does Jamal recall this encounter?

"A lot of people came in and out of the Pershing: Billie Holiday, Miles and dozens of others because it was a popular spot, and we helped to make it that way. What I remember more vividly than that is in the late '50s Paul Chambers-who looked like he was 12 years old-coming down to Cadillac Bob's [a two-level steakhouse featuring music in a black section of Chicago.] Because we would go downstairs where the bands were and they would come upstairs where we were.

"I also remember Miles once came in the Smiling Dog Saloon in Cleveland, and at the Pori festival in Finland, for example. And we lived a block and a half from each other in New York: I was on 75th Street; he was on 77th. But we never did get into any hanging out or any extensive conversations."

Those days in the late '50s-when some dismissed Jamal as a cocktail pianist, while some like Davis championed his use of space and subtlety-seem practically ancient when listening to the vibrancy and depth of his current efforts. So much has changed, and yet there are moments when a telling constancy in Jamal's style becomes apparent on In Search Of-moments of contemplative hesitation and smoothly executed rhythmic shifts; drop-offs in dynamics and harmonically rich chordal approach; surprise melodic fragments, like the "Stolen Moments" quote spicing "I've Never Been in Love Before."

Noting that the pianist continues to cover songs by the likes of Frank Loesser and others (a version of Monty Alexander's "You Can See" also made it onto In Search Of) leads him to comment on what it is that deems a tune worthy of a Jamal treatment.

"Take 'Whisperings,' by Aziza Miller, who wrote the words. It helps to have an in-depth study of the melodic line. And if you know the lyrics as well as the melodic line, you're going to approach it differently. If you're playing 'Lush Life' and you don't know what the lyrics are, you're not going to be able to really do as good a job as a person who does know them, as far as I'm concerned. Sure, you're an instrumentalist, but you should know what the human voice is saying, too. That's the oldest instrument in the world. If you don't respect that, you've got a problem."

The conversation shifts from repertoire to the subject of career crests and changes. As is his wont, Jamal responds with metaphor.

"Of course, you wouldn't expect a doctor not to use certain developments that weren't in existence 20 years ago. Music is the same way. The approach to music changes according to the times. As life changes, so do you. Now I have time to try to write, so I'm doing maybe 80 percent my compositions. It used to be the other way around-80 percent the compositions of others. You have a basic foundation, yes, but you're supposed to build on that. You don't stay in one position in life. You have many peaks. One of my peaks of my career was my emergence at the Pershing."

By "peaks," does he mean what fans and critics have celebrated as defining signposts along the road of Jamal's progress: the Pershing, his return to New York at the Village Gate in the early '60s, his excursions on electric piano in the late '60s and late '70s?

"Maybe I use the term loosely. I was referring to mass acceptance, if I can call it that. The little acceptance that we get as instrumentalists-be it Miles or Herbie Hancock or Dave Brubeck-are peaks. For example, there was a period of my career where I worked Carnegie Hall with Dakota Staton, the wonderful lady who went to the same high school I went to. She was at her peak with 'The Late Late Show' [in 1957] and I had it at the Pershing-we were very much in demand at that time. But 'peaks' can also mean how you feel about yourself, so right now is a peak too."

Jamal's current self-satisfaction spreads wide. Life is good, and as he has done during career heights in the past, he has taken on new projects. In the late '50s it was a restaurant in Chicago, alcohol-free as per his Muslim faith. In the late '60s, he formed a management company and ran three record labels (Cross, Jamal and AJP), producing titles by Shirley Horn, Sonny Stitt and others. Today, it turns out to be a gig managing a young pianist Jamal was turned on to by his former bassist.

"Hiromi-she's Japanese and only 23 years old. Richard Evans, who is head of the orchestra department at Berklee, called me up on the phone, and I heard two minutes of her playing and that was it. She's doing graduate work, but she's already a pro, and does it all-playing ensemble, writing. She can do stride. I comanage her along with my manager, Laura Hess-Hay, and the Yamaha Music Foundation. I have her doing two of George Wein's festivals this year, Bryant Park and Saratoga, and Tanglewood. And she has a release on Telarc [Another Mind]."

Jamal excuses himself and returns with an advance copy of the album, being sure to point out one of his favorite tracks. "She wrote 'The Tom & Jerry Show' when she was a little kid, listening to the cartoon music. That's Hiromi. When you hear that, then you'll know what I'm talking about. So I'm very busy managing her now."

And busy handling interviews with persistent writers with just one more question focusing on the past. How does it feel being one of a vanishing few active in the days when jazz giants ruled and scuffled? The pianist accommodates his interviewer good-naturedly.

"It feels like I'm walking history, Ashley. I was fortunate, and I caught most of the giants. I met Art Tatum when I was 14 years old. We went to a jam session together at the Washington Club up in Pittsburgh. I have some cufflinks somewhere that Ben Webster gave me. Great man-what a player! I had occasion to finally meet Billy Strayhorn, whose family I sold papers to when I was seven years old. I remember a Carnegie Hall concert from 1952. It was Duke Ellington's 25th anniversary, and it had Charlie Parker with strings, Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday and myself. I'm the only one remaining headliner from that billing. So I'm a bit of walking history-that's what it feels like."

Gearbox

"I've been with Steinway since 1960-that's 42 years. I went over to [New York's Steinway showroom on] 57th street with Fritz Steinway on my right and John Hammond on my left, and I've been with them ever since. I have two in my playing room there-9-footers-my black beauties.

"On the road I take a digital piano-Technics SX-P50-just to have in my hotel room so I don't have to go searching for a piano. With the amp, it gets a bit heavy-about 73 pounds-but with earphones, it doesn't disturb anybody. I used to have Steinway send me a piano in the room, years ago, but I stopped that. It's very important that I have a piano visible at all times because I want to be able to write any time I get ready."

Ahmad & Shirl

When Shirley Horn's latest, May the Music Never End (Verve), hit the shelves this past June, astute fans of the dulcet-toned singer might have noticed a rare listing on the cover: piano on two tracks courtesy of Ahmad Jamal. His guesting on another's album-especially one known for her own laconically phrased keyboard work-speaks to a number of things: a long-lasting friendship, an enduring mutual admiration and a serious health issue.

In January 2002, Horn lost her right foot due to diabetes, a serious impediment for one whose playing relied heavily on manipulating the instrument's pedal. But by May, the 69-year-old had already returned to performing, singing from a wheelchair, with favorite pianist George Mesterhazy at the keys ("He was a godsend-he's right there for me.") By 2003, Horn had recovered to the point that she was flying around, back to her normal monthly touring schedule. Audiences in Miami, Las Vegas and New York found her gregarious as ever, a bouquet of welcome-back roses inevitably in her lap. Such a severe, life-saving procedure normally demands a longer recuperative period. "Well, I'm impatient!" Horn admits.

After appearing for a weeklong engagement at New York's Iridium this past February-two, hour-long sets a night, Tuesday through Saturday-Horn remained in town to record the music for May the Music Never End. It's classic Horn: sparse, seductive, with her trio (Mesterhazy, bassist Ed Howard and drummer Steve Williams). The material diverse, evocative and unexpected: Jacques Brel's "If You Go Away," Paul McCartney's "Yesterday," Harold Arlen's "Ill Wind," Duke Ellington's "Take Love Easy." (The latter two are tastefully laced by Roy Hargrove's trumpet.) The title track is again by Artie Butler, the songwriter who delivered Horn her late-career anthem, "Here's to Life."

And of course, there are two tracks-Percy Faith's "Maybe September" and Gordon Jenkins' "This Is All I Ask"-with an old friend.

"He's my Debussy, you know? We had the same manager for many years- [former bassist] John Levy. I first heard Ahmad on a record in his office in the early '60s-and it just knocked me out. Then I met him in New York on several occasions. Once he was playing in Washington when I was about to have a baby. I was having labor pains and I told my husband I had to go see Ahmad and he said, 'No, you can't do that!' He took the [car] keys from me."

Their connection, as Jamal adds, "has continued through the years. I've known Shirley for a long, long time. She recorded for my company in the late '60s. I discovered Shirley on my own and vice-versa. She's one of the great voices of the present age and still remains brilliant. You know, we were supposed to do a session in Paris about five years ago, but it didn't come off because I was tied up with some other things. So when she asked me to do these tracks with her, I consented."

Anything to the choice of tunes they covered together?

"They were her choice," Jamal notes. "I don't know what inspired her to do 'This Is All I Ask,' but she always asked me to do 'Maybe September' when she would come in the clubs."

"He did an album and this song was on it [Heat Wave, Cadet, 1966] and it haunted me," Horn recalls. "I never did it myself, but I said, 'One day I want to sing this particular song with him. We met up in France and I had witnesses. I said, 'Do I have to throw a net over you? You're going to do this with me' [laughs]. And I love that 'This Is All I Ask.' It all just seemed to fit."

Undaunted as ever, Horn continues to juggle performances, housework and therapy sessions, learning to work with a set of custom-designed prostheses that will eventually have her playing piano full time again. "There are three: one for walking, one for sitting and one just for playing the sustaining pedal on the piano. It does take a little more time, and I'm always into cooking and tending my home and doing all my work around the house. I fight with the prosthesis daily, but my target date is tomorrow. I will win!" she laughs. "I have to because I have to play for myself. That's all I know."

Music News

Ahmad Jamal, 'A Musical Architect Of The Highest Order,' Keeps On Building

At 84, acclaimed jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal is still recording and touring

by Karen Michel Jamal's music can sound expansive, even friendly. He seems at peace in his Connecticut home, tinkering at one of his two grand pianos. But that doesn't mean he's "happy."

"Happy is kind of a shallow word," Jamal says. "Happy new year, happy this, happy that. But peace is another dynamic, OK?

The house, well away from New York City, boasts a waterfall in the backyard, a music room and walls hung with photos and awards. He points out one of the pictures and says, "This is the oldest mosque in the US, where I went to study."

Jamal was 20 and living in Chicago when he changed his name and religion and was, he says, "born." Along with the name of his youth, the moment and what preceded it is something he says he doesn't want to be asked about.

By other reckonings, though, Jamal was born in Pittsburgh on July 2, 1930. And he is happy to talk about being 3 years old and sitting at a piano for the first time.

"My mother's piano, I walked by it, and my Uncle Lawrence — 'Can you do what I'm doing?' And that's it," he says. "My uncle was quite surprised: I played everything he played. And the rest is history."

Jamal kept playing, starting formal lessons when he was 7. By the time he was 14, he was playing piano professionally and soaking in the music of Earl Hines, Erroll Garner and Billy Strayhorn whenever they were playing in town.

Jamal attracted the attention of respected producer John Hammond, who later helped launch the careers of Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and Aretha Franklin, among others. Hammond signed the pianist in the early 1950s, but it wasn't until the end of the decade that he reached a wide audience. His live album But Not for Me and its version of the latin tune "Poinciana" put him on the charts.

Miles Davis became a fan, says Gerald Early, an author music critic and professor at Washington University in St. Louis, Mo.

Jamal prefers the term "American classical music" to "jazz." And he says that just like classical musicians, he, too, plays other people's music.

"There are very, very few of us who don't play covers. Whhether it's people working in the European tradition or European classical music, be it Van Cliburn — those are covers. Or Horowitz — those are covers.They're playing Mozart, they're playing Beethoven; they're not playing their compositions. Ninety percent of the time they're playing covers, and that's what we do with American songbook as well," he says.

Still, as Gerald Early points out, in the 1960s and '70s, Jamal was often under-appreciated by critics for his restrained, almost minimalist approach.

"He was dismissed by some of the leading jazz critics as a cocktail pianist because of the kind of quiet approach he made to the music — and also because he was commercially successful," Early says. "For many jazz critics, it was the kiss of death if a jazz performer was commercially successful, and Jamal was a very popular pianist."

Critics are one thing. Peers are another. Matthew Shipp is among the younger jazz pianists who've been influenced by Ahmad Jamal. He says that Jamal's impact on him was huge, as is Jamal's place in American musical history.

"His imagination is so deep," Shipp says. One of the joys of listening to him is to see how his fertile imagination interacts with the material he does pick, and recombines it into a musical entity that we've never heard. I mean, Ahmad Jamal is a musical architect of the highest order."

"My music is a lot of things: it's serious, it's humorous, it's sad, it's happy," Jamal says. "It's many things and it's many years of living, and still continues to be."

In recent years, Jamal's been been recording and playing more of his own compositions. But he continues to play "Poinciana," the tune that made him a jazz star more than 50 years ago. And he still plays it with plenty of oomph — and restraint.

Featured Artist

http://www.npr.org/2013/10/09/230702507/ahmad-jamal-weaves-the-old-with-some-new-on-saturday-morning

Music Reviews

Ahmad Jamal Weaves Old And New On 'Saturday Morning'

Ahmad Jamal.

Courtesy of the artist Jamal's old trios were quieter — it's no surprise when a pianist plays with lots of energy in youth, and then with more reserve when he or she is older. But Jamal has gone the other way: Over time, he's become more expansive. Bassist Reginald Veal and New Orleans drummer Herlin Riley bring hardcore swing and funk to his new record.

In the composition "Back to the Future," Jamal slips in an on-the-nose quote from "Things Ain't What They Used to Be." But the more things change, the more they stay the same. Jamal is a grand master of seasoning his solos with obvious or covert fragments of songs he's been collecting all his life. Sometimes, those quotes reflect his personal history. A snippet of Morton Gould's light classic "Pavanne" in the midst of "Firefly" rings bells in the distance. Jamal recorded a cover of "Pavanne" in the 1950s, and his version inspired both Miles Davis' "So What" and John Coltrane's "Impressions." Jamal shows he was tuned to AM radio in the '60s, as he quotes The Animals' "Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood" and The Association's "Windy." But a witty quote alone isn't enough: It's about where you put it.

Ahmad Jamal loves misdirection; he'll sound like he's introducing one tune when he's really lining up another. He rephrases the beginning of 1935's "I'm in the Mood for Love" to resemble "I'll String Along with You," written the year before. That makes a subtle point about how composers rework colleagues' ideas, just as improvisers do.

The pianist combines his love of quotation and misdirection in Duke Ellington's "I Got It Bad and That Ain't Good," where Jamal keeps mixing in other 1941 Ellingtonia: "Just Squeeze Me" (also from the show Jump for Joy) and the piano intro to Duke's then-new theme, "Take the 'A' Train," by Jamal's friend from his Pittsburgh days, Billy Strayhorn. The pianist weaves three related tunes into one memory.

One more thing Ahmad Jamal never tires of: the lilt he gets from Afro-Caribbean rhythms. In his first trio, Ray Crawford faked bongo beats on guitar strings; in the current quartet, Manolo Badrena brings out the Latin accents on bongos and conga. He also courageously still uses chime rack and flexatone, long after other percussionists have moved on.

I confess the newer, splashier Ahmad Jamal can send me back to his quietly precise early trios. He's not playing the way he did 60 years ago, now that he's finished warming up.

Featured Artist

http://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2012/07/02/156110245/ahmad-jamal-still-fearless-and-innovative-at-82

Music Articles

Ahmad Jamal: Still Fearless And Innovative At 82

Ahmad Jamal at the grand piano during the Blue Moon sessions. Jacques Beneich

Since the early 1950s, Jamal has been a driving force in jazz, profoundly influencing a number of musicians including Miles Davis and John Coltrane. Jamal's earliest recording sessions were with piano, bass and guitar; he soon replaced the guitar with drums. In each of these formats, Jamal's approach was groundbreaking. In an essay on Jamal, the great critic Stanley Crouch wrote, "Through the use of space and changes of rhythm and tempo, Jamal invented a group sound that had all the surprise and dynamic variation of an imaginatively imagined big band."

Though Jamal occasionally works with larger groups, string sections and orchestras, it is the jazz piano trio format that he revolutionized and continues to explore. As a birthday salute to one of the true masters of jazz, here are five selections from Ahmad Jamal's staggering and ever-expanding body of small-group work.

Pavanne

- from Pavanne for Ahmad

- by Ahmad Jamal

Poinciana

- from Complete Live at the Pershing Lounge 1958

- by Ahmad Jamal

One

- from Digital Works

- by Ahmad Jamal

Blue Gardenia

- from Chicago Revisited: Live at Joe Segal's Jazz Showcase

- by Ahmad Jamal

Autumn Rain

- from Blue Moon: The New York Session

- by Ahmad Jamal

Blue Moon is available from Harmonia Mundi.

Featured Artist

Ahmad Jamal

http://www.joealtermanmusic.com/new-page-2/Interview with Ahmad Jamal

Interview with Ahmad Jamal

by Joe Alterman

5/10/2011

This past Saturday, I had the honor and pleasure of interviewing the great Ahmad Jamal. Not only has he been one of the most influential jazz musicians of all time, but his music has been instrumental (no pun intended) in my development as a musician; in fact, it was his recording of "Like Someone In Love" that got me hooked on jazz. For years, I've had many questions that I've wished I could ask Mr. Jamal, and this past Saturday I was given that opportunity. He was extremely kind, honest, thoughtful, and giving in his answers. It was an absolute thrill to speak with one of my heroes, the great Ahmad Jamal, and I hope you enjoy reading the following bits from our conversation.

Joe Alterman: One of the things that I’ve always loved about your playing is your repertoire. I’m curious how you were originally introduced to the great standards.

- Ahmad

Jamal: My aunt, who was an educator in North Carolina, sent me many,

many compositions via sheet music, and that’s how I gained the vast

repertoire that you hear me indulge in. I was sent those things by her

gracious efforts from 10 years old and on. So my Aunt Louise was the one

responsible for me acquiring that vast repertoire of standards…It’s a

combination of what she did and also working around one of the great

cities for musicians, or people who were developing a career in music:

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. So working with groups in Pittsburgh, and what

she sent me, and the environment under which I grew up in. As you know

I…well you don’t know (laughter), but I sold papers to Billy Strayhorn’s

family when I was seven years old. So we [Pittsburgh] have Billy

Strayhorn and Erroll Garner and Earl Hines and Roy Eldridge, Ray Brown,

Art Blakey, and a pianist that you’ve probably never heard of, Dodo

Momarosa. He was a great pianist…And Earl Wild, the great exponent of

Liszt; a great interpreter of Franz Liszt…And Gene Kelly the tap dancer.

The list goes on and on and on…George Benson, who was a much later

personality that developed in Pittsburgh. But he’s a Pittsburgh

personality, as well as Stanley Turrentine. It goes on and on and on.

JA: Mary Lou Williams too. Right?

AJ: Mary Lou came there when she was very, very young – a lot of people think she’s from Pittsburgh…but she came there when she was very, very young. I think she’s from Georgia, but she came to Pittsburgh when she was three or four years old. She went to the same high school I went to. And you can’t forget Billy Eckstine and Kenny Clarke…All those masters come from Pittsburgh.

JA: A couple months ago, Jimmy Heath came to NYU to give a class, and our teacher asked, “What was it like growing up in Philadelphia?” And he said, “I don’t want to talk about that. The great music town was Pittsburgh.”

AJ: (Lots of laughter) They had some great musicians too. That’s all the same; I kind of group them all as “Pennsylvanians.” Philadelphia had some wonderful artists, and Harrisburg produced one of the great bassists of all time, who I was just thinking about recently, Dr. Art Davis. Jimmy Smith is from Pennsylvania as well. So we have a grouping there. Philadelphia was a great area for music, but that’s all part of Pennsylvania. (laughter)

JA: There’s a bunch of tunes you played that are really rare, such as “Music, Music, Music”, tunes that you may have the only jazz version of. Were you purposely trying to pick out songs that weren’t played as frequently? Or did you just like those songs?

AJ: No, I just played songs that I liked. I just picked out songs that I favored; it wasn’t an attempt to do anything but use the repertoire and use the things that I had learned and heard in my growing-up years.

JA: Do you remember when you first heard “Poinciana”?

AJ: “Poinciana” was a part of the repertoire that Dr. Joseph Kennedy, Jr. had in our book. Joe Kennedy, the great violinist and educator - who is also from Pennsylvania. McDonald, which is also part of Pittsburgh…suburbia. But he had that in the repertoire when I formed “The Three Strings.” It was a spin-off from “The Four Strings;” I was the pianist in that, which was his group. I was introduced to “Poinciana” through his repertoire and what he wrote and what he selected as compositions that “The Four Strings” should perform. It was Joe Kennedy, myself, and Ray Crawford, the guitarist. Joe Kennedy was a master violinist.

JA: Do you learn the lyrics to the songs you play? Are lyrics important to you?

AJ: You have to…Well you don’t have to, but in order to re-interpret these things correctly or in a more informed-of manner, you should know the lyrics or know something about the lyrics. It gives you an idea about what the composer had in mind. Most of the songs that I perform I know the lyrics.

In fact, recently I’ve started writing lyrics to a lot of my things. I’m beginning to write lyrics to a composition that I wrote which is also going to Moscow, “Flight to Russia.” I think I’m going to send that to Igor Butman. I think Igor is one of the really popular musicians in Russia; I think he went to Berkeley too. James [Cammack] is well aware of Igor. I’m in the process of doing that as well.

So, lyrics are very essential. It’s like the famous story about Ben Webster, the great saxophonist. He’s playing a beautiful ballad…you’ve heard this story many times but I’m going to repeat it: Ben Webster was one of the great ballad players of all time, and he was playing this wonderful ballad and he suddenly stopped. And they said, “Ben, why in the world did you stop?” He said, “I forgot the lyrics.” You’ve heard that story before?

JA: Yes. I was reading an interview with Bill Evans and the interviewer asked him the same question and Evans said that he’s never learned any lyrics, he doesn’t care for them, and that the singer might as well be a horn player.

AJ: (Laughter). Well, different strokes for different folks. But, to me, lyrics are very essential. You know, you don’t have to, but I think you’re a more informed interpreter if you know the lyrics.

JA: Did you work consciously on your touch? You’ve got the “magic touch.”

AJ: Well, you know, that’s the interesting thing about Horowitz: he’s playing the same repertoire, but it’s his touch that makes the difference. If you listen to Horowitz or some of the great people who work in the European body of work, it’s the same repertoire. But, everything lies in the touch. Horowitz had a great touch.

JA: One of the other people I think of, in jazz, with a great touch is Hank Jones.

AJ: Hank Jones had a wonderful touch. So did Art Tatum. In fact, that should be a prerequisite for every music student: Tiny Grimes, Slam Stewart, and Art Tatum playing “Flying Home.” Whether you’re working in a European body of work or in American Classical repertoire, the prerequisite should be Art Tatum’s “Flying Home.”

That’s a unique thing about people in American Classical Music, which is a phrase I coined some time ago: you have to know the best of both worlds. I was playing Franz Liszt in competition when I was ten years old, but I was also playing Duke Ellington. So that’s a marvelous thing about the wonderful players that make up our genre. We have to be multi-dimensional. Dave Brubeck has to know Mozart. He has to know Duke Ellington, and it’s the same way with George Shearing; he can play the concertos but he can also write “Lullaby of Birdland.” So that’s the wonderful thing about people that are working in our field. They’re multi-dimensional; they’re not one-dimensional. That’s why I call them “American Classicists.” I think that “jazz” does not define properly what we do. I’m not paranoid about the term “jazz” but I don’t call myself a “jazz musician.” I call myself and my colleagues, the John Coltranes, and the Duke Ellingtons, “American Classicists.”

There are only two art forms that developed in the United States and that’s American Indian art and this thing we call jazz. I call it American Classical Music and that’s what it is. The little thoughts that we have here have been put here by way of these two developments: American Indian Art and American Classical Music, both of which are never promoted. You don’t see Duke Ellington every day on the television. You should, but you don’t. You don’t see Dave Brubeck every day on the television. You don’t see me and you don’t see George Shearing, but you should. You don’t see Louis Armstrong. But in Europe, you do. Not here, and that’s unfortunate.

JA: I’m wondering if you were purposely trying to innovate this music, which is what I often hear from different educators that the greats such as yourself did, or if you played what you loved and it just happened to be different.

AJ: Well, the fact is that all Pittsburghers are uniquely different. No one plays piano like Erroll Garner. No one plays bass like Ray Brown. No one plays piano like Earl Hines. No one plays drums like Art Blakey. No one plays saxophone like Stanley Turrentine. We all have ushered in a different era that’s just one of the unique phenomena of Pittsburgh. No one danced like Gene Kelly. No one interpreted Liszt quite like Earl Wild. Lorin Maazel, the conductor, is from Pittsburgh too. Andy Warhol is from Pittsburgh. It goes on and on. It’s very difficult for me to exhaust the list but all of us are different and unique so it’s just a phenomenon that all of us have a different approach. This is a thing that happened to me as a result of growing up there; I followed that same pattern.

JA: Were you close with Erroll Garner?

AJ: My mother and his mother were friends, but I didn’t meet Erroll until after because he was working in places I couldn’t go in was a kid. Erroll had the best jobs in Pittsburgh and I was too young to go where he was working. So I didn’t know Erroll until later. He came back to Westinghouse High School and played for us. I was amazed because it seemed as though he was playing on all the black keys and in all the multi-flat and multi-sharp keys. He was certainly a person who heard everything in all the keys…B Natural, G Flat, F Sharp; it didn’t make any difference.

He was quite a stride player, too. A lot of people don’t know that. So I didn’t know Erroll until later on; I met him after I left home.

JA: I know you’re obviously influenced by Garner and Nat Cole, but one of the things that people don’t talk about as much as they talk about your linear and melodic lines is your mastery of the block chord technique. Who influenced you in terms of block chords? Erroll Garner? George Shearing? Milt Buckner?

AJ: If you really want to do a study on the mastery of block chords you have to listen to Phineas Newborn. Even today, he’s certainly underrated…That’s another area that’s produced some fantastic musicians: Memphis. My former bassist, the late Jamil Nasser, is one of them. But Phineas is from Memphis and so is Harold Mabern, who’s doing a professorship at one of your schools now – William Patterson College I think.

The block chords is, to me, demonstrated more by people like Phineas than myself. But I didn’t learn anything from George Shearing; we’re peers. I mean I admired George, but my influences were Erroll and Nat and Art Tatum.

JA: In the ‘50’s and ‘60’s people like you, Erroll Garner, Ray Brown, Oscar Peterson, and Dave Brubeck were the most popular guys around; but a lot of times in the textbooks and classes in schools they don’t talk about those people as much; instead they focus on people like George Russell, Lennie Tristano, and Cecil Taylor. Does this surprise you at all?

AJ: I pay little attention to that. I’m so busy doing my own thing that I don’t reflect on what the people are crediting and giving other people in my field. It’s just a waste of time for me. You know? (Laughter)

JA: Are you a book lover? A movie lover?

AJ: I don’t do movies at all. I like non-fiction and if I read, it has to be non-fiction. I don’t like fiction; I like the real thing. And I have books that I read but most of them are philosophical. I’m going back to the discipline of reading; I used to gobble up books when I was a youngster. But I’m going back to it now. In fact, I was surprised at myself: I was waiting for my car to be serviced today and I was reading the editorials in the Wall Street Journal, and I was reading also about the focus on the new approach to music videos. It was very interesting. A lot of it has stuff to do with things that are not musical, as far as I’m concerned. A lot of stuff on MTV has nothing to do with music, but that’s what we’ve created here. We have a focus on non-musical things and a lack of focus on musical things. Music is supposed to sooth the savaged beast and in many instances we’re raising the savaged beast.

But my point is that I’m getting back to the discipline of reading, which I lost some years ago.

Most of the things I read are non-fiction and I don’t care for movies too much. The last movies I went to see was “The Bridges of Madison County” because my daughter said Clint Eastwood had two of my recordings in part of the soundtrack. I wanted to see that. That’s the first thing you hear, soundtrack-wise, are my recordings of “Music, Music, Music” and “Poinciana”.

JA: Does it bother you that there is so much music in the background these days? Like at the mall while you’re shopping, for example.

AJ: Not as long as it’s good music. I can’t stand the commercials. Without the mute button, I could never tolerate television because some of the commercials are just horrible. I don’t know what these manufacturers are thinking of because you can sell a product, to me, much more effectively with music that soothes and is not irritable and not nerve-wracking, as opposed to what they have now. I don’t know why they chose to do the negative instead of the positive on these commercials.

JA: I’ve been fortunate enough to be in contact with Houston Person, and one of the things he talks about is that it’s an enormous responsibility to have people come out at night and spend their hard-earned money on him. He wants to play good music of course, but he wants to relax the people in the audience; he doesn’t want to make them nervous with the music, and he feels a great responsibility to do this, especially after the people worked so hard for their money that they’re spending on him. Do you agree?

AJ: I have two words: He’s right.

JA: I find it interesting that you’re one of the few great pianists that didn’t come up as, or wasn’t documented as, a sideman, backing horn players for example. It seems that you’ve always been known as a leader. Did you ever do more sideman work and how did you make it as a leader?

AJ: Your question is a very interesting one and it has to do with my longevity in the field. I started playing at three years old, which is very, very young. That’s what I say when people ask, “How did you choose music?” I say, when you are that young, you don’t make conscious decisions, Joe. Music chose me; I didn’t choose it, and I was working as a sidemen at ten years old. I worked with groups around Pittsburgh for many years. I worked on the road with a song and dance team. So I had a history of being a sideman. I worked with George Hudson’s orchestra; he made me leave my happy home in 1948. I left at 17 years old and worked all over the country with him. Out of that band came Clark Terry and the great writer Ernie Wilkins. He was a great orchestrator, and I think he passed [away] in Europe, in Copenhagen. I was a sideman for many, many, many years…When I was young; that was part of my growing-up years…I was an old man by the time I was 18 (laughter). I went from young to old very quick and what made me old was when I started my group in 1951. That was the end of any sideman issues; I had to keep my men working, and I’ve had that responsibility now for over five decades, Joe: being a leader. But I was a sideman for many, many years in and around Pittsburgh and all over the United States with a group called the Cardwells. When I left that group, Ray Bryant, the great pianist, became their person in the pianists’ chair. And I worked with George Hudson all over; that was my first time at the Apollo Theater actually. We were touring with stars like Dinah Washington at that time so I was a sideman for many years. I became a leader at a very young age; I was 21 years old, so that’s quite a span of time.

JA: I know Miles Davis loved you. Did you two ever talk about playing together?

AJ:No, because he was leading and I was leading. That never happened; there was some attempt to get Miles and Cannonball and myself on record together, but that never reached fruition.

JA: I love the video of you and your trio playing “Darn That Dream”.

AJ: Oh yes. With Israel Crosby and Vernell Fourier as my guys, the masters that helped make my career what it is.

JA: In that video, I see Hank Jones standing over your shoulder, and Ben Webster.

AJ: That’s correct. Ben Webster, who I spoke of, is there. Jo Jones – Papa Jo that is – and some of the other greats were there: George Duvivier and Buck Clayton…That’s a classic. That video’s a classic.

JA: That must have been nerve-wracking. Did you used to get nervous?

AJ: I don’t remember what I got (Laughter). I know it was a very interesting experience, and it’s still being shown all over the world, especially now with the Internet.

JA: Do you teach?

AJ: I taught for a brief period of time in Chicago, my second home. But, you know, teaching is something you must dedicate your life to in order to give that student his or her due. So, I haven’t taught in a long, long time. I spent a period of time doing that in Chicago. I had this hit record, or what they call a hit record for instrumentalists. We don’t have hit records, but I had one and Dave Brubeck had one with “Take Five” and Herbie Hancock had a few and Chuck Mangione and Miles, but very few instrumentalists had hits. Singers get the hits but I did have one, and that took me away from teaching and I never went back to it (laughter). I was performing, and that’s what I’ve been devoting my life to. And now I’ve been devoting my life to resetting and reshaping my career, doing what I love so much, and that’s composing. I’m trying to get away from the sense of urgency that the cell-phone and the computer and all the activities have thrust upon us, and I’ve been trying to do the things I really love to do, which is playing in my favorite venue: my home.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324492604579082994292232418Masterpiece

A New Architecture for Jazz

The

Ahmad Jamal Trio's 1958 album "But Not For Me" may have confounded

critics, but it changed the direction of the jazz-piano trio,

influencing such great names as Peterson, Evans and Davis. The recording

remains one of jazz's most elegant recordings.

by Marc Myers

by Marc Myers

Sept. 28, 2013

Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal

Fifty-five

years ago this week, an album by a jazz trio entered Billboard's

best-sellers chart and within weeks jumped over Elvis Presley's "King

Creole" and Mitch Miller's "Sing Along With Mitch" to occupy the No. 3

slot. The album—the Ahmad Jamal Trio's "But Not For Me," recorded live

at Chicago's Pershing Lounge—would appear on the chart for 107 weeks,

confounding jazz critics and influencing the direction of the jazz-piano

trio. Today, it remains one of jazz's most elegant recordings.

http://shop.cherryred.co.uk/el-exd.asp?id=5334

Recorded on Jan. 16, 1958, and released that spring, "But Not for Me" deeply affected how jazz pianists voiced standards and interacted musically with their bass players and drummers. By August, the album had sold nearly 48,000 copies—a staggering accomplishment since any album's sale of just 20,000 copies in its first few months back then was considered significant. Equally impressive was that the album was on Argo—a niche label based in Chicago. By contrast, one of jazz's most successful albums—the Dave Brubeck Quartet's "Time Out"—wouldn't be released until the following year and was greatly helped by Columbia's powerful mail-order record club and marketing machine. By the end of 1958, "But Not for Me" was the top-selling jazz album in stores.

The rapid rise of Mr. Jamal's album and its staying power owed much to the trio's relaxed sound, its long-term stay at the Pershing and a media gambit by Argo executives. When early word of the album's strong sales trickled out, the label invited Billboard to review its books. Billboard took a look and published a buzz-building trade article in August 1958 that caught the eye of radio and retailers and led to the release of singles from the album—including "Poinciana," which became the trio's signature song.

Mr. Jamal's distinctive style—melodies played on the piano's upper-most notes combined with elegant and brief midkeyboard chord clusters—had been revered by jazz musicians since his first recordings in 1951. Miles Davis so admired Mr. Jamal's lyrical, space-rich approach on "Surrey With the Fringe on Top," "A Gal in Calico," "Billy Boy" and other early recordings by the pianist that he recorded them virtually the same way. The trio's conversational approach also left a lasting impression on many pianists, including Oscar Peterson, Red Garland, Bill Evans, Phineas Newborn Jr. and Herbie Hancock.

Yet jazz critics gave "But Not for Me" and Mr. Jamal a rough ride. Martin Williams in Down Beat magazine called the album "cocktail piano" music, while Ralph J. Gleason wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle that Mr. Jamal was "an effete Erroll Garner" who left "too many spaces for the other members to fill." The New Yorker's Whitney Balliett said Mr. Jamal's style gave "the impression achieved by spasmodically stopping and unstopping the ears in a noisy room." Rather than embrace Mr. Jamal's minimalist sophistication, critics simply concluded he had sold out.

Listening to the album today (it can be found on Mosaic's "The Complete Ahmad Jamal Trio Argo Sessions: 1956-62"), it's hard to grasp why so many jazz critics missed the point. The album features Mr. Jamal, bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernel Fournier performing eight swinging interpretations of well-known songs. Critics who had gushed about Ella Fitzgerald's Songbook series and many jazz-pop albums produced by Norman Granz were curiously hard on Mr. Jamal.

For their part, many critics by 1958 had come to expect jazz pianists to serve up growling, robust attacks—like the gospel-funk of Horace Silver, the fiery flash of Mr. Peterson and the daring of Thelonious Monk. By contrast, Mr. Jamal was gentle and spirited, playing with songs like a cat on its back having fun with a ball of string. But while the album is a study in subtlety, Mr. Jamal used plenty of percussive surprise and an elastic range.

"The orchestral sense I had developed growing up in Pittsburgh never left me," said the 83-year-old Mr. Jamal in a recent phone interview shortly after releasing "Saturday Morning," his latest CD. "My extensive use of the keyboard's high end just happened. I liked the melodic nature it lent compositions. By lingering there, I also could leave plenty of room for Vernel and Israel."

Mr. Jamal's orchestral approach to his trio arrangements—worked out in advance of performances and recordings—allowed the listener to hear the piano melody way up top, Mr. Fournier's whiskerlike brush strokes in the middle range and the thump of Mr. Crosby's bass down below. Mr. Jamal was keenly aware of how space could pull listeners close while familiar melodies and high notes won hearts.

Fans can thank a glass of wine for the recording. In 1956, Mr. Jamal was playing during intermissions at the Embers in New York when a drunk with a request accidentally spilled his drink all over him. "That was it," Mr. Jamal said. "I got up, Israel and I got our coats, and we drove to Chicago in my Buick station wagon. My guitarist, Ray Crawford, didn't want to come, so he stayed behind."

Once in Chicago, Mr. Jamal went to the Pershing Lounge and proposed playing there as its artist in residence. "I had a name by then and they liked the idea. I hired Vernel to join Israel and me, and we played five sets a night, six nights a week, for over a year. Everyone in the music business dropped by to hear us—and many heard ideas that they used for their own trios and albums."

In late 1957, when Argo's owner, Leonard Chess, began talking about recording the trio, Mr. Jamal insisted they do it live at the Pershing. "The room was about intimacy and drama, and we were comfortable there. We were more than ready after playing together for so long. We recorded 43 songs that night in front of a live audience. I listened back for a week and chose eight tracks for the album. There was no splicing. What you hear is what we played."

But fear of artistic theft had forced Mr. Jamal to take precautions. "Leading up to the recording, we stopped playing 'Poinciana' to keep my arrangement a secret. I thought another pianist might come in, hear it and steal what I was doing. I knew we had something special. I had a gut feeling."

Mr. Jamal was more than right. When "But Not for Me" was released in 1958, it had enormous crossover appeal—creating a new architecture for the jazz trio and how standards were interpreted. Unfortunately, many jazz critics didn't know what to make of it. The album had become too successful.

Trio & Quintet Recordings - Ahmad Jamal

'Listen to the way Jamal uses s

'Listen to the way Jamal uses space. He lets it go so that you can feel the rhythm section and the rhythm section can feel you. It's not crowded. Ahmad is one of my favourites. I live until he makes another record.'

--Miles Davis, 1958

The complete,

legendary recordings made by Ahmad Jamal with the guitarist Ray Crawford in

Trio and Quintet context. Jamal's trios are considered to be amongst the most

important in the history of jazz, creating unique articulations of space,

openness and light, which still seem so far ahead of their time and which made

such a profound impression on Miles

Davis and his arranger, Gil Evans.

Jamal's art

embodies discipline, restraint, refinement and subtlety and furthermore he

swings. Miles appreciated the level of intensity Jamal achieved within such a

subtle framework.

Compositions such

as ‘New Rhumba’ were transcribed note for note by Gil Evans for 'Miles Ahead'.

"I was delighted, " recalled Jamal "We needed that kind of

support at the time Miles came along and paid us that compliment."

Our edition

comprises the albums "Chamber Music of The New Jazz”, "The Ahmad Jamal Trio”, "The

Piano Scene of Ahmad Jamal” (with material recorded between 1951 and 1955) and "Listen

to the Ahmad Jamal Quintet” (recorded in 1960).

DISC

ONE: THE AHMAD JAMAL TRIO

1. NEW RHUMBA

2. A FOGGY DAY

3. ALL OF YOU

4. IT AIN'T NECESSARILY SO

5. I DON'T WANNA BE KISSED (BY ANYONE BUT YOU)

6. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU

7. JEFF

8. DARN THAT DREAM

9. SPRING IS HERE

10. PERFIDIA

11. LOVE FOR SALE

12. RICA PULPA

13. AUTUMN LEAVES

14. SQUEEZE ME

15. SOMETHING TO REMEMBER YOU BY

16. BLACK BEAUTY

17. THE DONKEY SERENADE

18. DON'T BLAME ME

19. THEY CAN'T TAKE THAT AWAY FROM ME

20. NEW RHUMBA

Miles Davis with the Gil Evans

Orchestra

DISC TWO: THE AHMAD JAMAL TRIO / THE THREE STRINGS

1. OLD DEVIL MOON

2. AHMAD'S BLUES

3. POINCIANA

4. BILLY BOY

5. WILL YOU STILL BE MINE

6. PAVANNE

7. CRAZY HE CALLS ME

8. THE SURREY WITH THE FRINGE ON TOP

9. AKI AND UKTHAY

10. SLAUGHTER ON 10TH AVENUE

11. A GAL IN CALICO

12. IT'S EASY TO REMEMBER

THE

AHMAD JAMAL QUINTET

13. AHMAD'S WALTZ

14. VALENTINA

15. YESTERDAYS

16. TEMPO FOR TWO

17. HALLELUJAH

18. IT'S A WONDERFUL WORLD

19. BAIA

20. YOU CAME A LONG WAY FROM ST. LOUIS

21. LOVER MAN

22. WHO CARES

23. JOY SPRING – Gil

Evans Orchestra (with Ray Crawford)

Music News: Interview with Ahmad Jamal

ROBERT SIEGEL

NPR HOST:

Ahmad Jamal has been playing piano for most of his 84 years. He has been named an American Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts and achieved that rarest of feats for a jazz musician - mainstream popularity. His most recent release came out earlier this year. And for our series The Ones That Got Away, stories we didn't get to before now, Karen Michel spoke to the musician at his home in Connecticut.

KAREN MICHEL, BYLINE: Ahmad Jamal seems cautious at the keyboard.

AHMAD JAMAL: Let me see, Ms. Michel, if I can't get these hands in motion (playing piano).

MICHEL: His music can sound expansive, even friendly.

JAMAL: (Playing piano). That's it (laughter).

MICHEL: And that's how Jamal comes across at home. He's at peace here, but that doesn't mean that he's necessarily happy.

JAMAL: Happy is kind of a shallow word, you know? Happy - happy New Year, happy this, happy that - peace is another dynamic, OK?

MICHEL: Jamal's home, well away from New York City, boasts a waterfall in the backyard, a music room with two grand pianos and walls hung with awards and photos.

JAMAL: This is the oldest mosque in the United States where I went to study. I studied at this mosque in Chicago.

MICHEL: Jamal was 20 and living in Chicago when he changed his name and his religion and was, he says, born. Along with the name of his youth, it's something Jamal says he doesn't want to be asked about, talk about, any of it. Though, by other reckonings he was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on July 2, 1930. He will talk about being 3 years old and sitting at a piano for the first time.

JAMAL: Sure - 6307 Dean Street in Pittsburgh. My mother's piano - I walked by it and my Uncle Lawrence said can you do that, what I'm doing? And my uncle was quite surprised that I played everything he played, and the rest is history.

MICHEL: Jamal started formal lessons when he was 7. By the time he was 14, he was playing piano professionally.

(SOUNDBITE OF PIANO MUSIC)

MICHEL: Jamal eventually attracted the attention of respected producer John Hammond, who later helped launch the careers of Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and Aretha Franklin, among others. Hammond signed the pianist in the early 1950s.

(SOUNDBITE OF PIANO MUSIC)

MICHEL: But it wasn't until the end of the decade that Jamal reached a wide audience. His live album "But Not For Me" and its version of the Latin tune "Poinciana" put Jamal on the charts.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "POINCIANA")

MICHEL: Trumpeter Miles Davis became a fan, says Gerald Early, an author, music critic and professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

GERALD EARLY: He admired Jamal as a player, but he also admired him as kind of a theoretician, in so far as OK, here's a way you can improvise in jazz music that opens up a new way of looking at virtuosity that isn't built on just stacking up a whole bunch of cords.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "POINCIANA")

MICHEL: Jamal prefers the term American classical music to jazz. And he says just like classical musicians, he too plays other people's compositions.

JAMAL: There are very, very few of us who don't play covers. Whether it's people who are working in the European classical music tradition - be it Van Cliburn or Horowitz - those are covers. They're playing Mozart; they're playing Beethoven. They're not playing their compositions. Ninety percent of the time, they're playing covers, and that's what we do with American songbook as well.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "POINCIANA")

MICHEL: Jamal's restrained, almost minimalist approach won him a broad audience, but did not win over critics, says Gerald Early.

EARLY: He was dismissed by some of the leading jazz critics as a cocktail pianist because of the kind of quiet approach that he made to the music, and also because he was commercially successful (laughter). For many jazz critics that was the kiss of death if a jazz performer was commercially successful. And Jamal was a very popular pianist.

MICHEL: Critics are one thing, peers are another. Matthew Shipp is among the younger jazz pianists who've been influenced by Ahmad Jamal.

MATTHEW SHIPP: His imagination is so deep. I mean, that's what's so special about him is to see how his fertile, compositional imagination interacts with any standards that he does pick and kind of recombines it and reconstructs it into a musical entity that we've never heard. I mean, Ahmad Jamal's a musical architect of the highest order.

MICHEL: In recent years, Jamal's been recording and playing more of his own compositions.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC)

JAMAL: My music is a lot of things - it's serious, it's humorous, it's sad, it's happy, it's peaceful; it's many, many things. And it's many, many years of living. My music is many, many years of living and it still continues to be.

MICHEL: Ahmad Jamal continues to play "Poinciana," the tune that made him a jazz star more than 50 years ago. And he still plays it with plenty of oomph - and restraint. For NPR News, I'm Karen Michel.

http://www.scfta.org/revue/1012/revue-1012-jamal.htmlNPR HOST:

Ahmad Jamal has been playing piano for most of his 84 years. He has been named an American Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts and achieved that rarest of feats for a jazz musician - mainstream popularity. His most recent release came out earlier this year. And for our series The Ones That Got Away, stories we didn't get to before now, Karen Michel spoke to the musician at his home in Connecticut.

KAREN MICHEL, BYLINE: Ahmad Jamal seems cautious at the keyboard.

AHMAD JAMAL: Let me see, Ms. Michel, if I can't get these hands in motion (playing piano).

MICHEL: His music can sound expansive, even friendly.

JAMAL: (Playing piano). That's it (laughter).

MICHEL: And that's how Jamal comes across at home. He's at peace here, but that doesn't mean that he's necessarily happy.

JAMAL: Happy is kind of a shallow word, you know? Happy - happy New Year, happy this, happy that - peace is another dynamic, OK?

MICHEL: Jamal's home, well away from New York City, boasts a waterfall in the backyard, a music room with two grand pianos and walls hung with awards and photos.

JAMAL: This is the oldest mosque in the United States where I went to study. I studied at this mosque in Chicago.

MICHEL: Jamal was 20 and living in Chicago when he changed his name and his religion and was, he says, born. Along with the name of his youth, it's something Jamal says he doesn't want to be asked about, talk about, any of it. Though, by other reckonings he was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on July 2, 1930. He will talk about being 3 years old and sitting at a piano for the first time.

JAMAL: Sure - 6307 Dean Street in Pittsburgh. My mother's piano - I walked by it and my Uncle Lawrence said can you do that, what I'm doing? And my uncle was quite surprised that I played everything he played, and the rest is history.

MICHEL: Jamal started formal lessons when he was 7. By the time he was 14, he was playing piano professionally.

(SOUNDBITE OF PIANO MUSIC)

MICHEL: Jamal eventually attracted the attention of respected producer John Hammond, who later helped launch the careers of Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen and Aretha Franklin, among others. Hammond signed the pianist in the early 1950s.

(SOUNDBITE OF PIANO MUSIC)

MICHEL: But it wasn't until the end of the decade that Jamal reached a wide audience. His live album "But Not For Me" and its version of the Latin tune "Poinciana" put Jamal on the charts.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "POINCIANA")

MICHEL: Trumpeter Miles Davis became a fan, says Gerald Early, an author, music critic and professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

GERALD EARLY: He admired Jamal as a player, but he also admired him as kind of a theoretician, in so far as OK, here's a way you can improvise in jazz music that opens up a new way of looking at virtuosity that isn't built on just stacking up a whole bunch of cords.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "POINCIANA")

MICHEL: Jamal prefers the term American classical music to jazz. And he says just like classical musicians, he too plays other people's compositions.

JAMAL: There are very, very few of us who don't play covers. Whether it's people who are working in the European classical music tradition - be it Van Cliburn or Horowitz - those are covers. They're playing Mozart; they're playing Beethoven. They're not playing their compositions. Ninety percent of the time, they're playing covers, and that's what we do with American songbook as well.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, "POINCIANA")

MICHEL: Jamal's restrained, almost minimalist approach won him a broad audience, but did not win over critics, says Gerald Early.

EARLY: He was dismissed by some of the leading jazz critics as a cocktail pianist because of the kind of quiet approach that he made to the music, and also because he was commercially successful (laughter). For many jazz critics that was the kiss of death if a jazz performer was commercially successful. And Jamal was a very popular pianist.

MICHEL: Critics are one thing, peers are another. Matthew Shipp is among the younger jazz pianists who've been influenced by Ahmad Jamal.

MATTHEW SHIPP: His imagination is so deep. I mean, that's what's so special about him is to see how his fertile, compositional imagination interacts with any standards that he does pick and kind of recombines it and reconstructs it into a musical entity that we've never heard. I mean, Ahmad Jamal's a musical architect of the highest order.

MICHEL: In recent years, Jamal's been recording and playing more of his own compositions.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC)

JAMAL: My music is a lot of things - it's serious, it's humorous, it's sad, it's happy, it's peaceful; it's many, many things. And it's many, many years of living. My music is many, many years of living and it still continues to be.

MICHEL: Ahmad Jamal continues to play "Poinciana," the tune that made him a jazz star more than 50 years ago. And he still plays it with plenty of oomph - and restraint. For NPR News, I'm Karen Michel.

Copyright © 2014 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline

by a contractor for NPR, and accuracy and availability may vary. This

text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the

future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of NPR’s

programming is the audio.

Jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal makes his Center debut

For more than 60 years, Ahmad Jamal has

been a master of American jazz piano as well as an educator and

composer. He's had an impact on generations of jazz musicians: According

to music critic Stanley Crouch, Jamal is second in importance in the

development of jazz after 1945 only to Charlie Parker. Another great

jazz pianist, Shirley Horn, studied classical music at university, but

soon after graduating she joined a jazz piano trio. Talking later about

her jazz influences, she said, "Oscar Peterson became my Rachmaninov,

and Ahmad Jamal became my Debussy."

One of Jamal's students, the incomparable Miles Davis, said, simply, "When people say Jamal influenced me, they're right!"

Jamal may be one of the last living titans of jazz's so-called Golden Era who continues to redefine modern jazz. The New York Times says, "[His] rows of shocking diversions and riffs … could be mistaken for a younger, experimental-minded pianist," while the Chicago Tribune

calls him a musician "who defies practically every convention of the

jazz pianist's art." Jamal's hallmark is his ability to take a tune and

expose all its vibrancy, his hands running lightly over the entire

keyboard to create his identifiable sound. There is an ease and elegance

to his music that has been his keynote throughout his career.

He plays with three musicians but considers

this ensemble an "orchestra," and he can easily coax a large sound out

of his musicians: Reginald Veal, bass; Herlin Riley, drums; and Manolo

Badrena, percussion. His piano provides the harmony and melody, while

bass, drums and percussion give the rhythmic underpinning. Jamal is

tight with his partners, and, although he's the leader, he gives them

opportunities to take the lead and carry the tune while Jamal adds a

deft touch. Some of his songs have a symphonic aspect, an elegant,

florid sound that can fill a room, but Jamal doesn't need to turn up the

volume to make his music exciting. He's able to conjure up wonderful

colors and a unique point of view with songs like "Swahililand" and

"Romance on the High Seas," creating a striking undercurrent that

connects to Jamal's sound from his early days. His 1958 hit "Poinciana"

is still his signature tune, and he continues to improvise and imbue

this tune with a modern sound.

Jamal's contributions have been recognized and

rewarded both nationally and internationally. He is a recipient of a

National Endowment for the Arts American Jazz Masters Fellowship, and

the French government inducted him into its prestigious Order of Arts

and Letters, an honor given to select distinguished artists and writers.

Even in his ninth decade, Jamal's signature sound remains youthful,

fresh, imaginative and always influential, and he continues to inspire

with his new arrangements and stylistic explorations of the keyboard.

RENÉE AND HENRY SEGERSTROM CONCERT HALL

Date: November 24, 2012

Tickets: $25 and up

For tickets and information, visit SCFTA.org or

call (714) 556–2787.

Group services: (714) 755–0236

audio.Date: November 24, 2012

Tickets: $25 and up

For tickets and information, visit SCFTA.org or

call (714) 556–2787.

Group services: (714) 755–0236

http://www.opb.org/kmhd/article/recap-an-interview-with-ahmad-jamal/

Living legend, Ahmad Jamal, is arguably one of the greatest pianists in jazz history. Having been on the scene since the 1950’s, Jamal answers questions about Miles Davis, his hometown of Pittsburgh, and his new quartet. Known for his use of space and time, Jamal’s work is minimalistic and a boundary-pushing approach to modern jazz. A well-seasoned musician, he seems to be getting more adventurous with every critically-acclaimed new album released.

Listen to the interview with Ahmad Jamal below:

https://soundcloud.com/kmhd-radio/ahmad-jamal-interview

AUDIO: <iframe width="100%" height="166" scrolling="no" frameborder="no" src="https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/136541526&color=ff5500&show_artwork=false"></iframe>

AHMAD JAMAL: INTERVIEW IN 2010: "American Classical Music"

"All my inspiration comes from Ahmad Jamal'

--Miles Davis

A conversation with the legendary educator, composer and pianist Ahmad Jamal.

Music, education and Miles Davis

("Ahmad's Blues" performed by Miles Davis) .

All music by Ahmad Jamal.

http://www.ahmadjamal.net