SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2016

VOLUME TWO NUMBER TWO

NINA SIMONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

NAT KING COLE

January 2-8

ETTA JAMES

January 9-15

JACKIE MCLEAN

January 16-22

TERRI LYNE CARRINGTON

January 23-29

NANCY WILSON

January 30-February 5

BOB MARLEY

February 6-12

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

February 13-19

HORACE SILVER

February 20-26

SHIRLEY HORN

February 27-March 4

T-BONE WALKER

March 5-11

HOWLIN’ WOLF

March 12-18

DIANNE REEVES

March 19-25

LOUIS ARMSTRONG (1901-1971)

Artist Biography by William Ruhlmann

Louis Armstrong was the first important soloist to emerge in jazz, and he became the most influential musician in the music's history. As a trumpet virtuoso, his playing, beginning with the 1920s studio recordings made with his Hot Five and Hot Seven ensembles, charted a future for jazz in highly imaginative, emotionally charged improvisation. For this, he is revered by jazz fans. But Armstrong also became an enduring figure in popular music, due to his distinctively phrased bass singing and engaging personality, which were on display in a series of vocal recordings and film roles.

Armstrong had a difficult childhood. William Armstrong, his father, was a factory worker who abandoned the family soon after the boy's birth. Armstrong was brought up by his mother, Mary (Albert) Armstrong, and his maternal grandmother. He showed an early interest in music, and a junk dealer for whom he worked as a grade-school student helped him buy a cornet, which he taught himself to play. He dropped out of school at 11 to join an informal group, but on December 31, 1912, he fired a gun during a New Year's Eve celebration, for which he was sent to reform school. He studied music there and played cornet and bugle in the school band, eventually becoming its leader. He was released on June 16, 1914, and did manual labor while trying to establish himself as a musician. He was taken under the wing of cornetist Joe "King" Oliver, and when Oliver moved to Chicago in June 1918, he replaced him in the Kid Ory Band. He moved to the Fate Marable band in the spring of 1919, staying with Marable until the fall of 1921.

Armstrong moved to Chicago to join Oliver's band in August 1922 and made his first recordings as a member of the group in the spring of 1923. He married Lillian Harden, the pianist in the Oliver band, on February 5, 1924. (She was the second of his four wives.) On her encouragement, he left Oliver and joined Fletcher Henderson's band in New York, staying for a year and then going back to Chicago in November 1925 to join the Dreamland Syncopators, his wife's group. During this period, he switched from cornet to trumpet.

Armstrong had gained sufficient individual notice to make his recording debut as a leader on November 12, 1925. Contracted to OKeh Records, he began to make a series of recordings with studio-only groups called the Hot Fives or the Hot Sevens. For live dates, he appeared with the orchestras led by Erskine Tate and Carroll Dickerson. The Hot Fives' recording of "Muskrat Ramble" gave Armstrong a Top Ten hit in July 1926, the band for the track featuring Kid Ory on trombone, Johnny Dodds on clarinet, Lillian Harden Armstrong on piano, and Johnny St. Cyr on banjo.

By February 1927, Armstrong was well-enough known to front his own group, Louis Armstrong & His Stompers, at the Sunset Café in Chicago. (Armstrong did not function as a bandleader in the usual sense, but instead typically lent his name to established groups.) In April, he reached the charts with his first vocal recording, "Big Butter and Egg Man," a duet with May Alix. He took a position as star soloist in Carroll Dickerson's band at the Savoy Ballroom in Chicago in March 1928, later taking over as the band's frontman. "Hotter than That" was in the Top Ten in May 1928, followed in September by "West End Blues," which later became one of the first recordings named to the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Armstrong returned to New York with his band for an engagement at Connie's Inn in Harlem in May 1929. He also began appearing in the orchestra of Hot Chocolates, a Broadway revue, given a featured spot singing "Ain't Misbehavin'." In September, his recording of the song entered the charts, becoming a Top Ten hit.

Armstrong fronted the Luis Russell Orchestra for a tour of the South in February 1930, then in May went to Los Angeles, where he led a band at Sebastian's Cotton Club for the next ten months. He made his film debut in Ex-Flame, released at the end of 1931. By the start of 1932, he had switched from the "race"-oriented OKeh label to its pop-oriented big sister Columbia Records, for which he recorded two Top Five hits, "Chinatown, My Chinatown" and "You Can Depend on Me" before scoring a number one hit with "All of Me" in March 1932; another Top Five hit, "Love, You Funny Thing," hit the charts the same month. He returned to Chicago in the spring of 1932 to front a band led by Zilner Randolph; the group toured around the country. In July, Armstrong sailed to England for a tour. He spent the next several years in Europe, his American career maintained by a series of archival recordings, including the Top Ten hits "Sweethearts on Parade" (August 1932; recorded December 1930) and "Body and Soul" (October 1932; recorded October 1930). His Top Ten version of "Hobo, You Can't Ride This Train," in the charts in early 1933, was on Victor Records; when he returned to the U.S. in 1935, he signed to recently formed Decca Records and quickly scored a double-sided Top Ten hit, "I'm in the Mood for Love"/"You Are My Lucky Star."

Armstrong's new manager, Joe Glaser, organized a big band for him that had its premiere in Indianapolis on July 1, 1935; for the next several years, he toured regularly. He also took a series of small parts in motion pictures, beginning with Pennies From Heaven in December 1936, and he continued to record for Decca, resulting in the Top Ten hits "Public Melody Number One" (August 1937), "When the Saints Go Marching in" (April 1939), and "You Won't Be Satisfied (Until You Break My Heart)" (April 1946), the last a duet with Ella Fitzgerald. He returned to Broadway in the short-lived musical Swingin' the Dream in November 1939.

Louis Armstrong was the first important soloist to emerge in jazz, and he became the most influential musician in the music's history. As a trumpet virtuoso, his playing, beginning with the 1920s studio recordings made with his Hot Five and Hot Seven ensembles, charted a future for jazz in highly imaginative, emotionally charged improvisation. For this, he is revered by jazz fans. But Armstrong also became an enduring figure in popular music, due to his distinctively phrased bass singing and engaging personality, which were on display in a series of vocal recordings and film roles.

Armstrong had a difficult childhood. William Armstrong, his father, was a factory worker who abandoned the family soon after the boy's birth. Armstrong was brought up by his mother, Mary (Albert) Armstrong, and his maternal grandmother. He showed an early interest in music, and a junk dealer for whom he worked as a grade-school student helped him buy a cornet, which he taught himself to play. He dropped out of school at 11 to join an informal group, but on December 31, 1912, he fired a gun during a New Year's Eve celebration, for which he was sent to reform school. He studied music there and played cornet and bugle in the school band, eventually becoming its leader. He was released on June 16, 1914, and did manual labor while trying to establish himself as a musician. He was taken under the wing of cornetist Joe "King" Oliver, and when Oliver moved to Chicago in June 1918, he replaced him in the Kid Ory Band. He moved to the Fate Marable band in the spring of 1919, staying with Marable until the fall of 1921.

Armstrong moved to Chicago to join Oliver's band in August 1922 and made his first recordings as a member of the group in the spring of 1923. He married Lillian Harden, the pianist in the Oliver band, on February 5, 1924. (She was the second of his four wives.) On her encouragement, he left Oliver and joined Fletcher Henderson's band in New York, staying for a year and then going back to Chicago in November 1925 to join the Dreamland Syncopators, his wife's group. During this period, he switched from cornet to trumpet.

Armstrong had gained sufficient individual notice to make his recording debut as a leader on November 12, 1925. Contracted to OKeh Records, he began to make a series of recordings with studio-only groups called the Hot Fives or the Hot Sevens. For live dates, he appeared with the orchestras led by Erskine Tate and Carroll Dickerson. The Hot Fives' recording of "Muskrat Ramble" gave Armstrong a Top Ten hit in July 1926, the band for the track featuring Kid Ory on trombone, Johnny Dodds on clarinet, Lillian Harden Armstrong on piano, and Johnny St. Cyr on banjo.

By February 1927, Armstrong was well-enough known to front his own group, Louis Armstrong & His Stompers, at the Sunset Café in Chicago. (Armstrong did not function as a bandleader in the usual sense, but instead typically lent his name to established groups.) In April, he reached the charts with his first vocal recording, "Big Butter and Egg Man," a duet with May Alix. He took a position as star soloist in Carroll Dickerson's band at the Savoy Ballroom in Chicago in March 1928, later taking over as the band's frontman. "Hotter than That" was in the Top Ten in May 1928, followed in September by "West End Blues," which later became one of the first recordings named to the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Armstrong returned to New York with his band for an engagement at Connie's Inn in Harlem in May 1929. He also began appearing in the orchestra of Hot Chocolates, a Broadway revue, given a featured spot singing "Ain't Misbehavin'." In September, his recording of the song entered the charts, becoming a Top Ten hit.

Armstrong fronted the Luis Russell Orchestra for a tour of the South in February 1930, then in May went to Los Angeles, where he led a band at Sebastian's Cotton Club for the next ten months. He made his film debut in Ex-Flame, released at the end of 1931. By the start of 1932, he had switched from the "race"-oriented OKeh label to its pop-oriented big sister Columbia Records, for which he recorded two Top Five hits, "Chinatown, My Chinatown" and "You Can Depend on Me" before scoring a number one hit with "All of Me" in March 1932; another Top Five hit, "Love, You Funny Thing," hit the charts the same month. He returned to Chicago in the spring of 1932 to front a band led by Zilner Randolph; the group toured around the country. In July, Armstrong sailed to England for a tour. He spent the next several years in Europe, his American career maintained by a series of archival recordings, including the Top Ten hits "Sweethearts on Parade" (August 1932; recorded December 1930) and "Body and Soul" (October 1932; recorded October 1930). His Top Ten version of "Hobo, You Can't Ride This Train," in the charts in early 1933, was on Victor Records; when he returned to the U.S. in 1935, he signed to recently formed Decca Records and quickly scored a double-sided Top Ten hit, "I'm in the Mood for Love"/"You Are My Lucky Star."

Armstrong's new manager, Joe Glaser, organized a big band for him that had its premiere in Indianapolis on July 1, 1935; for the next several years, he toured regularly. He also took a series of small parts in motion pictures, beginning with Pennies From Heaven in December 1936, and he continued to record for Decca, resulting in the Top Ten hits "Public Melody Number One" (August 1937), "When the Saints Go Marching in" (April 1939), and "You Won't Be Satisfied (Until You Break My Heart)" (April 1946), the last a duet with Ella Fitzgerald. He returned to Broadway in the short-lived musical Swingin' the Dream in November 1939.

With

the decline of swing music in the post-World War II years, Armstrong

broke up his big band and put together a small group dubbed the All

Stars, which made its debut in Los Angeles on August 13, 1947. He

embarked on his first European tour since 1935 in February 1948, and

thereafter toured regularly around the world. In June 1951 he reached

the Top Ten of the LP charts with Satchmo at Symphony Hall ("Satchmo"

being his nickname), and he scored his first Top Ten single in five

years with "(When We Are Dancing) I Get Ideas" later in the year. The

single's B-side, and also a chart entry, was "A Kiss to Build a Dream

On," sung by Armstrong in the film The Strip. In 1993, it gained renewed

popularity when it was used in the film Sleepless in Seattle.

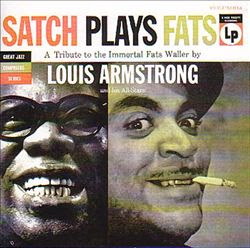

Armstrong completed his contract with Decca in 1954, after which his manager made the unusual decision not to sign him to another exclusive contract but instead to have him freelance for different labels. Satch Plays Fats, a tribute to Fats Waller, became a Top Ten LP for Columbia in October 1955, and Verve Records contracted Armstrong for a series of recordings with Ella Fitzgerald, beginning with the chart LP Ella and Louis in 1956.

Armstrong continued to tour extensively, despite a heart attack in June 1959. In 1964, he scored a surprise hit with his recording of the title song from the Broadway musical Hello, Dolly!, which reached number one in May, followed by a gold-selling album of the same name. It won him a Grammy for best vocal performance. This pop success was repeated internationally four years later with "What a Wonderful World," which hit number one in the U.K. in April 1968. It did not gain as much notice in the U.S. until 1987 when it was used in the film Good Morning, Vietnam, after which it became a Top 40 hit. Armstrong was featured in the 1969 film of Hello, Dolly!, performing the title song as a duet with Barbra Streisand. He performed less frequently in the late '60s and early '70s, and died of a heart ailment in 1971 at the age of 69.

As an artist, Armstrong was embraced by two distinctly different audiences: jazz fans who revered him for his early innovations as an instrumentalist, but were occasionally embarrassed by his lack of interest in later developments in jazz and, especially, by his willingness to serve as a light entertainer; and pop fans, who delighted in his joyous performances, particularly as a vocalist, but were largely unaware of his significance as a jazz musician. Given his popularity, his long career, and the extensive label-jumping he did in his later years, as well as the differing jazz and pop sides of his work, his recordings are extensive and diverse, with parts of his catalog owned by many different companies. But many of his recorded performances are masterpieces, and none are less than entertaining.

Armstrong, Louis

The work of trumpeter and vocalist Louis Armstrong both summed up the achievements of New Orleans style jazz and pointed the way to the later evolution of the music as a solo-oriented art form. His historical importance was matched by his popular appeal a rare combination in the jazz art form, which is often suspicious of commercial success and his career is bookmarked by the great "West End Blues" of 1928, at one end, which changed the course of jazz with its flamboyance and virtuosity, and (at the other end), by his hit records Hello Dolly and What a Wonderful World, which charmed a mass audience with their charisma and emotional directness. Critic Leslie Gourse entitled her book on jazz singers Louis Children, but the term could just as easily be applied to all later jazz musicians, who bask in legacy and often work in the shadow of this towering figure from the art form’s earliest days.

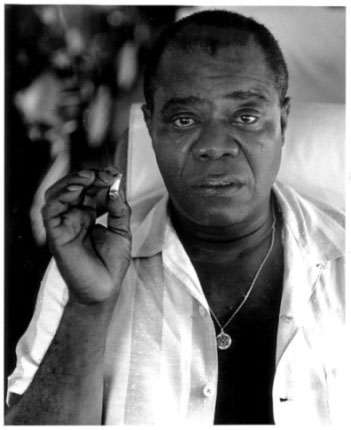

Louis Armstrong, photo by Herb Snitzer

Armstrong suffered the stigma of being the illegitimate child of a prostitute, raised in the abject poverty of turn-of-the-century New Orleans. His father William Armstrong left the family when Louis was still an infant, and his mother Mary Armstrong was often absent as well, with the child falling into the care of his grandmother or uncle. He briefly attended the Fisk School for Boys, but left when he was eleven. He earned money singing in the streets with a quartet of youngsters and working odd jobs. Arrested for firing a pistol as part of a New Year’s Eve celebration, Armstrong was placed in the New Orleans Home for Waifs. Armstrong benefited from the disciplined and structured environment in this setting, but perhaps even more by the musical training he received at the hands of Professor Peter Davis. Armstrong was soon gaining attention for his cornet playing, and soaking up the sounds of New Orleans jazz.

Armstrong was excited by the playing of cornetist Buddy Bolden, a quasi-legendary figure who never recorded but is often credited as the first musician to perform New Orleans style jazz. The youngster also admired and learned from Bunk Johnson, Kid Ory, Buddy Petit and especially the great Joe King Oliver. When Oliver left New Orleans in 1919 to try his luck up north, Armstrong took his place in Kid Ory’s ensemble. Armstrong also played on the riverboats, and served as second trumpet for the Tuxedo Brass Band. Around this time Armstrong married Daisy Parker, and the couple adopted Clarence Armstrong, the son of Louis’s cousin Flora who had died shortly after the boy�s birth. But the marriage did not last long, and Parker herself died soon after the divorce.

In 1922, Armstrong was invited to travel to Chicago and join King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. This ensemble was the most celebrated jazz band in Chicago at the time, and the association gave Armstrong a platform for his later fame and success. Armstrong and Oliver gained attention for the counterpoint of their two cornets, but in time the younger players more assertive approach tended to outshine the work of his employer. On King Oliver’s classic recording of Dippermouth Blues", we see the stark contrast between the two stylists. The older Oliver stays true to the New Orleans tradition of blending in with the other instruments, and focusing on timbre and texture rather than varity of notes; but the younger Armstrong is chomping at the bit, anxious to demonstrate his virtuosity on the horn. His second wife, Lil Hardin Armstrong, who was also pianist with Oliver band, encouraged him to step out as a leader and develop his own style and sound as a jazz musician.

Louis Armstrong, photo by Herb Snitzer

Armstrong's

later recordings as a leader, known as the Hot Fives and Hot Sevens,

gave him an opportunity to do just that. Armstrong shifted from cornet

to trumpet in this period, and in a series monumental performances such

as Potato Head Blues, Struttin With Some Barbecue, and the aforemention

West End Blues -- he changed the shape of the jazz art form. Solos

became more prominent, the rhythmic and melodic vocabulary of the music

became more complex and varied, and the ethos of jazz shifted from an

emphasis on the ensemble to a focus on the individual. When Armstrong

encountered pianist Earl Hines, he had found another soloist who was

interested in re-shaping the traditions of the music, and their duet on

Weatherbird stands out as another milestone recording from the late

1920s.

But Armstrong also made an equally powerful impact on jazz singing. His recording of Heebie Jeebies is often cited as the birth of scat-singing. This is far from true -- vaudevillian Gene Greene recorded a scat-type vocal back in 1909 but no one exerted more influence on early jazz vocal styles than Armstrong. His phrasing as a singer captured the exciting syncopations of early jazz, but also stood out for the balance it offered between gritty roughness and sentimental tenderness.

These works both instrumental and vocal -- from the late 1920s represent Armstrong’s key contributions to the evolution of the jazz art form. But his work from the early 1930s deserves to be much better known. Outstanding but seldom heard recordings form this period include I’m a Ding Dong Daddy from 1930, as well as Shine, Lazy River, I Surrender Dear, Star Dust and Sweethearts on Parade from 1931. Armstrong continued to build his fame and reputation, and even the Great Depression, and a conviction for marijuana possession (in 1931), failed to hurt his commercial prospects and popular appeal. Armstrong moved to Los Angeles at the start of the decade, where he lived briefly, and dazzled Hollywood just as he had earlier charmed New Orleans and Chicago.

As the decade progressed, however, Armstrong became increasingly focused on adapting to the standard big band sound of the Swing Era. His recordings from this period are not without their merits, but this was a low point artistically for Armstrong. Yet Armstrong did not slacken his pace or stifle his ambitions. He often played as many as three hundred engagements during the course of a year. But this led to problems with his lip and fingers. His personal life was also turbulent in these years. For all his successes, Armstrong spent heavily and was often short of cash. His marriage to Lil ended in 1938 and he married his girlfriend Alpha, which also soon ended in divorce, before he settled down with his fourth and final wife Lucille.

Armstrong’s decision to return to the traditional New Orleans sound in the late 1940s was, in some degree, an ironic shift for the person who had done more than anyone to move jazz beyond the confines of this style. But his successful traditional jazz concert at Town Hall on May 17, 1947 showed that the public was receptive to this revivalist approach. Armstrong formed his All Stars, drawing on a changeable cast of older musicians, including Earl Hines, Jack Teagarden, Trummy Young, Edmond Hall, Barney Bigard and others who could authentically recreate the sounds and styles of the Jazz Age.

Armstrong had made the switch from fiery young artist to sedate elder statesman a role which he would continue to occupy with aplomb for the rest of his life. But Armstrong was never too sedate, and his performances continued to attract new fans with his extroverted personality and consummate skills as an entertainer. Yet even Louis must have been surprised with the success of his recording of Hello Dolly, which reached number one on the pop charts, and even dislodged the Beatles a remarkable achievement for a 63 year old performer in an era which was increasingly obsessed with the latest and newest young rock bands.

Armstrong died on July 6, 1971 at age 69, the victim of a heart attack. His funeral was an all-star event in its own right, and those in attendance included Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Johnny Carson, Ed Sullivan and Harry James. Armstrong’s last house is now a museum and historic landmark. Armstrong’s music and larger-than-life presence will no doubt still be remembered and honored at that late date.

Selected Bibliography

Armstrong, Louis. Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. New York: New American Library. Books, 1954.

Armstrong, Louis. Swing That Music. New York: Da Capo Press. Originally published in 1936 (London and New York: Longmans, Green), 1933.

Bergreen, Laurence. Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life. New York: Broadway Books, 1998.

Berrett, J., ed. 1999. The Louis Armstrong Companion: Eight Decades of Commentary. New York: Schirmer Books.

Brothers, Thomas. Louis Armstrong: In His Own Words. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Collier, James L. 1983. Louis Armstrong: An American Genius. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Giddins, Gary Satchmo. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988.

Gioia, Ted. The History of Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Goffin, Robert. Horn of Plenty; The Story of Louis Armstrong. James F. Bezou, trans. New York: Allen, Towne & Heath, 1947.

Hadlock, Richard. Jazz Masters of the Twenties. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988.

Schuller, Gunther. Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Travis, Dempsey J. The Louis Armstrong Odyssey: From Jane Alley to America's Jazz Ambassador. Chicago: Urban Research Press, 1997.

Williams, Martin. Jazz Masters of New Orleans. New York: Da Capo Press, 1979.

But Armstrong also made an equally powerful impact on jazz singing. His recording of Heebie Jeebies is often cited as the birth of scat-singing. This is far from true -- vaudevillian Gene Greene recorded a scat-type vocal back in 1909 but no one exerted more influence on early jazz vocal styles than Armstrong. His phrasing as a singer captured the exciting syncopations of early jazz, but also stood out for the balance it offered between gritty roughness and sentimental tenderness.

These works both instrumental and vocal -- from the late 1920s represent Armstrong’s key contributions to the evolution of the jazz art form. But his work from the early 1930s deserves to be much better known. Outstanding but seldom heard recordings form this period include I’m a Ding Dong Daddy from 1930, as well as Shine, Lazy River, I Surrender Dear, Star Dust and Sweethearts on Parade from 1931. Armstrong continued to build his fame and reputation, and even the Great Depression, and a conviction for marijuana possession (in 1931), failed to hurt his commercial prospects and popular appeal. Armstrong moved to Los Angeles at the start of the decade, where he lived briefly, and dazzled Hollywood just as he had earlier charmed New Orleans and Chicago.

As the decade progressed, however, Armstrong became increasingly focused on adapting to the standard big band sound of the Swing Era. His recordings from this period are not without their merits, but this was a low point artistically for Armstrong. Yet Armstrong did not slacken his pace or stifle his ambitions. He often played as many as three hundred engagements during the course of a year. But this led to problems with his lip and fingers. His personal life was also turbulent in these years. For all his successes, Armstrong spent heavily and was often short of cash. His marriage to Lil ended in 1938 and he married his girlfriend Alpha, which also soon ended in divorce, before he settled down with his fourth and final wife Lucille.

Armstrong’s decision to return to the traditional New Orleans sound in the late 1940s was, in some degree, an ironic shift for the person who had done more than anyone to move jazz beyond the confines of this style. But his successful traditional jazz concert at Town Hall on May 17, 1947 showed that the public was receptive to this revivalist approach. Armstrong formed his All Stars, drawing on a changeable cast of older musicians, including Earl Hines, Jack Teagarden, Trummy Young, Edmond Hall, Barney Bigard and others who could authentically recreate the sounds and styles of the Jazz Age.

Armstrong had made the switch from fiery young artist to sedate elder statesman a role which he would continue to occupy with aplomb for the rest of his life. But Armstrong was never too sedate, and his performances continued to attract new fans with his extroverted personality and consummate skills as an entertainer. Yet even Louis must have been surprised with the success of his recording of Hello Dolly, which reached number one on the pop charts, and even dislodged the Beatles a remarkable achievement for a 63 year old performer in an era which was increasingly obsessed with the latest and newest young rock bands.

Armstrong died on July 6, 1971 at age 69, the victim of a heart attack. His funeral was an all-star event in its own right, and those in attendance included Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, Johnny Carson, Ed Sullivan and Harry James. Armstrong’s last house is now a museum and historic landmark. Armstrong’s music and larger-than-life presence will no doubt still be remembered and honored at that late date.

Selected Bibliography

Armstrong, Louis. Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. New York: New American Library. Books, 1954.

Armstrong, Louis. Swing That Music. New York: Da Capo Press. Originally published in 1936 (London and New York: Longmans, Green), 1933.

Bergreen, Laurence. Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life. New York: Broadway Books, 1998.

Berrett, J., ed. 1999. The Louis Armstrong Companion: Eight Decades of Commentary. New York: Schirmer Books.

Brothers, Thomas. Louis Armstrong: In His Own Words. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Collier, James L. 1983. Louis Armstrong: An American Genius. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Giddins, Gary Satchmo. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988.

Gioia, Ted. The History of Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Goffin, Robert. Horn of Plenty; The Story of Louis Armstrong. James F. Bezou, trans. New York: Allen, Towne & Heath, 1947.

Hadlock, Richard. Jazz Masters of the Twenties. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988.

Schuller, Gunther. Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Travis, Dempsey J. The Louis Armstrong Odyssey: From Jane Alley to America's Jazz Ambassador. Chicago: Urban Research Press, 1997.

Williams, Martin. Jazz Masters of New Orleans. New York: Da Capo Press, 1979.

http://www.britannica.com/biography/Louis-Armstrong

Louis Armstrong,nickname Satchmo (truncation of “Satchel Mouth”) born August 4, 1901, New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S.—died July 6, 1971, New York, New York), the leading trumpeter and one of the most influential artists in jazz history.

Although Armstrong claimed to be born in 1900, various documents, notably a baptismal record, indicate that 1901 was his birth year. He grew up in dire poverty in New Orleans, Louisiana, when jazz was very young. As a child he worked at odd jobs and sang in a boys’ quartet. In 1913 he was sent to the Colored Waifs Home as a juvenile delinquent. There he learned to play cornet in the home’s band, and playing music quickly became a passion; in his teens he learned music by listening to the pioneer jazz artists of the day, including the leading New Orleans cornetist, King Oliver. Armstrong developed rapidly: he played in marching and jazz bands, becoming skillful enough to replace Oliver in the important Kid Ory band about 1918, and in the early 1920s he played in Mississippi riverboat dance bands.

![Oliver, King: King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band [Credit: Frank Driggs Collection/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_vQk9DJLgvAMge0gxsL1EimpeebtNIy1NJwdl-yKu4nEqVM77LTnk5rVXgwxuM2tgNfjmzfQF705sZUgL7QuwuPSREZO4mgx4nkRA7aIT-QC8ONLCj9fZ7jMiyEGPmHQSe1ihhKGF3aLg=s0-d)

Fame beckoned in 1922 when Oliver, then leading a band in Chicago, sent for Armstrong to play second cornet. Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band was the apex of the early, contrapuntal New Orleans ensemble style, and it included outstanding musicians such as the brothers Johnny and Baby Dodds and pianist Lil Hardin, who married Armstrong in 1924. The young Armstrong became popular through his ingenious ensemble lead and second cornet lines, his cornet duet passages (called “breaks”) with Oliver, and his solos. He recorded his first solos as a member of the Oliver band in such pieces as “

Encouraged by his wife, Armstrong quit Oliver’s band to seek further fame. He played for a year in New York City in Fletcher Henderson’s band and on many recordings with others before returning to Chicago and playing in large orchestras. There he created his most important early works, the Armstrong Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings of 1925–28, on which he emerged as the first great jazz soloist. By then the New Orleans ensemble style, which allowed few solo opportunities, could no longer contain his explosive creativity. He retained vestiges of the style in such masterpieces as “

Armstrong was a famous musician by 1929, when he moved from Chicago to New York City and performed in the theatre review Hot Chocolates. He toured America and Europe as a trumpet soloist accompanied by big bands; for several years beginning in 1935, Luis Russell’s big band served as the Louis Armstrong band. During this time he abandoned the often blues-based original material of his earlier years for a remarkably fine choice of popular songs by such noted composers as Hoagy Carmichael, Irving Berlin, and Duke Ellington. With his new repertoire came a new, simplified style: he created melodic paraphrases and variations as well as chord-change-based improvisations on these songs. His trumpet range continued to expand, as demonstrated in the high-note showpieces in his repertoire. His beautiful tone and gift for structuring bravura solos with brilliant high-note climaxes led to such masterworks as “

Louis and Lil Armstrong separated in 1931. From 1935 to the end of his life, Armstrong’s career was managed by Joe Glaser, who hired Armstrong’s bands and guided his film career (beginning with Pennies from Heaven, 1936) and radio appearances. Though his own bands usually played in a more conservative style, Armstrong was the dominant influence on the swing era, when most trumpeters attempted to emulate his inclination to dramatic structure, melody, or technical virtuosity. Trombonists, too, appropriated Armstrong’s phrasing, and saxophonists as different as Coleman Hawkins and Bud Freeman modeled their styles on different aspects of Armstrong’s. Above all else, his swing-style trumpet playing influenced virtually all jazz horn players who followed him, and the swing and rhythmic suppleness of his vocal style were important influences on singers from Billie Holiday to Bing Crosby.

![Armstrong, Louis: 1956 [Credit: Ted Streshinsky/Corbis]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_uBQBz-I9pBb6UWAaHzN1h3cc2XG0GXncfzJs72ty5nsHE9R3_2qQi_f3UxqcfwOHd11e7bq22dhytfzP4NMRGSBc424m8dQoP6BNof_YVeS_JvmqYxojceFcitIId4XXMGuP6sGLh3=s0-d)

In most of Armstrong’s movie, radio, and television appearances, he was featured as a good-humoured entertainer. He played a rare dramatic role in the film New Orleans (1947), in which he also performed in a Dixieland band. This prompted the formation of Louis Armstrong’s All-Stars, a Dixieland band that at first included such other jazz greats as Hines and trombonist Jack Teagarden. For most of the rest of Armstrong’s life, he toured the world with changing All-Stars sextets; indeed, “Ambassador Satch” in his later years was noted for his almost nonstop touring schedule. It was the period of his greatest popularity; he produced hit recordings such as “

![Voice of America: Willis Conover interviewing Louis Armstrong for a VOA radio broadcast, 1955 [Credit: Courtesy of Voice of America]](https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/blogger_img_proxy/AEn0k_tI6RaR-e45QmeyWGd86M4ngbUD2YW_jBf_qGRutzBdAtO2xeTPdG3xz4xiZju5CaegyAqVgdvBxH5TtEMS-LNEwia-XHYIBc356FaPE113t3kmSqLN3c03R7JCmiszWeXQPJlluKTdhQ=s0-d)

More than a great trumpeter, Armstrong was a bandleader, singer, soloist, film star, and comedian. One of his most remarkable feats was his frequent conquest of the popular market with recordings that thinly disguised authentic jazz with Armstrong’s contagious humour. He nonetheless made his greatest impact on the evolution of jazz itself, which at the start of his career was popularly considered to be little more than a novelty. With his great sensitivity, technique, and capacity to express emotion, Armstrong not only ensured the survival of jazz but led in its development into a fine art.

Armstrong’s autobiographies include Swing That Music (1936, reprinted with a new foreword, 1993) and Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans (1954).

http://dothemath.typepad.com/dtm/2014/03/louis-armstrong-and-miles-davis.html

Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis

Terry Teachout's play Satchmo at the Waldorf recently opened in New York. While obviously well-acted by John Douglas Thompson and successful with the audience, for me there wasn't enough unconditional love and respect for Mr. Louis Armstrong. This is also the theme of my essay about Terry's book on Duke, "Reverential Gesture."

I did appreciate Terry's biography of Armstrong, Pops. He's a true polymath (see our interview), and always considers jazz as part of American popular music. Those dedicated to jazz are often over-informed by insider knowledge, and it is refreshing to remember there's a whole wide world out there.

Even when I disagree with Terry it is grist for the mill. I was pulled up short by one aspect of Satchmo at the Waldorf: the portrayal of Miles Davis. After spending an afternoon with Google and my library, what I found was interesting enough to write up briefly for DTM.

---

I can't cite exact quotes from Satchmo at the Waldorf, but essentially Miles Davis appears as the "young angry black man" who thought Louis Armstrong was an Uncle Tom.

The fullest explication of the discordance between the civil rights era and Armstrong that I've seen is in Gerald Early's Tuxedo Junction:

The pain that one feels when Armstrong's television performances of the middle and late sixties are recalled is so overwhelming as to constitute an enormously bitter grief, a grief made all the keener because it balances so perfectly one's sense of shame, rage, and despair. The little, gnomish, balding, grinning black man who looked so touchingly like everyone's black grandfather who had put in thirty years as the janitor of the local schoolhouse or like the old black poolshark who sits in the barbershop talking about how those old boys like Bill Robinson and Jelly Roll Morton could really play the game; this old man whose trumpet playing was just, no, not even a shadowy, ghostly remnant of his days of glory and whose singing had become just a kind of raspy-throated guile, gave the appearance, at last, of being nothing more than terribly old and terribly sick. One shudders to think that perhaps two generations of black Americans remember Louis Armstrong, perhaps one of the most remarkable musical geniuses America ever produced, not only as a silly Uncle Tom but as a pathetically vulnerable, weak old man. During the sixties, a time when black people most vehemently did not wish to appear weak, Armstrong seemed positively dwarfed by the patronizing white talk-show hosts on whose programs he performed, and he seemed to revel in that chilling, embarrassing spotlight.

Early is writing in the late '80s, just before Wynton Marsalis and Stanley Crouch would gain traction with an alternative narrative. Wynton has said, "[Louis Armstrong] left an undying testimony to the human condition in the America of his time." For Stanley, Armstrong is, "One of the few who can be easily be mentioned with Stravinsky, Picasso and Joyce."

This narrative isn't always popular with contemporary jazzmen, who want more unreserved praise given to Miles Davis and John Coltrane when Wynton or Stanley appear on TV for a sound bite about jazz. For myself, I fervently hope that their narrative is closer to what young black kids learn today than the "silly Uncle Tom" narrative that worries Early.

---

People like beefs. Satchmo at the Waldorf includes Armstrong jousting with both Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis. Terry is very canny, and I'm certain that all the quotes are true, although it isn't explained that some of them are from years after Louis was dead.

Miles's appearances in Waldorf culminate in that remarkable bit of gallows humor from 1985 in Jet:

If somebody told me that I had an hour to live, I'd spend it choking a white man. I'd do it nice and slow.

Who am I to analyse Miles Davis? But I think he playing to the audience here. He wouldn't say that to DownBeat, he's saying it to Jet. (It reminds me of Armstrong being photographed with Amiri Baraka's Blues People in the pages of Ebony twenty years earlier.) If Miles makes you upset, you've fallen into his trap. Later on in the Jet piece, Davis says, "Those the shoe don't fit, well, those don't wear it."

Miles had a lot of facets. His support of Gil Evans and Bill Evans did the most of anybody to validate a kind of romantic or white sound in modern jazz. By 1985 all the editions of his band had had white players for years.

Anyway, back to beefs. According to Waldorf, Miles really gave Louis Armstrong a hard time. A casual search of the internet indicates this is common wisdom. (Rifftides; CBC; Daily Kos; Newsday; many more.)

Beefs are fun, but it is more helpful to see Afro-American jazz as a continuum. I was just listening to Miles Davis's E.S.P. and think that part of the trumpeter's solution to this hard new Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock music was to play Louis Armstrong quotes.

As far as I can discover from my library and the internet at this moment, the following is what Miles said about Louis Armstrong when he was alive:

1949: In DownBeat to Pat Harris, Miles says that Louis is one of his favorite musicians.

1955: In a DownBeat blindfold test with Leonard Feather, he listened to "Ain't Misbehavin'" with Bobby Hackett and Jack Teagarden. I believe the "statements" Miles refers to are Louis's putdowns of modern jazz.

I like Louis! Anything he does is all right. I don't know about his statements, though, I could do without them...I'd give it five stars.

1958: In the Jazz Review with Nat Hentoff, he listened to "Potato Head Blues":

Louis has been through all kinds of styles. That's good tuba, by the way. You know you can't play anything on a horn that Louis hasn't played - I mean even modern. I love his approach to the trumpet; he never sounds bad. He plays on the beat - with feeling. That's another phrase for swing. I also love the way he sings.

1962: In Playboy to Alex Haley:

I love Pops, I love the way he sings, the way he plays - everything he does, except when he says something against modern-jazz music. He ought to realize that he was a pioneer, too. No, he wasn't an influence of mine, and I've had very little direct contact with Pops. A long time ago, I was at Bop City, and he came in and told me he liked my playing. I don't know if he would even remember it, but I remember how good I felt to have him say it. People really dig Pops like I do myself. He does a good job overseas with his personality. But they ought to send him down South for goodwill. They need goodwill worse in Georgia and Alabama and Mississippi than they do in Europe.

Hyland Harris also sent me two candids, and you can see the respect Miles has on his face when greeting Pops.

The

most condemning things Miles said about Armstrong seem to be from his

1989 autobiography co-written with Quincy Troupe. Armstrong is

repeatedly name-checked as one of the greats, but in the photo album he

gives us Pops, Beulah, Buckwheat, and Rochester: "Some of the images of

black people I would fight against throughout my career. I loved Satchmo

but couldn't stand all the grinning he did."

Also from the book:

As much as I love Dizzy and loved Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong, I always hated the way they used to laugh and grin for the audiences. I know why they did it - to make money and because they were entertainers as well as trumpet players. They had families to feed. Plus they both liked acting the clown; it's just the way Dizzy and Satch were. I don't have nothing against them doing it if they want to. But I didn't like it and didn't have to like it...Also I was younger than them and didn't have to go through the same shit to get accepted by the music industry. They had already opened up a lot of doors for people like me to go through...

...

I loved the way Louis played trumpet, man, but I hated the way he had to grin in order to get over with some tired white folks. Man, I just hated when I saw him doing that, because Louis was hip, had a consciousness about black people, and was a real nice man. But the only image people have of him is that grinning image off TV.

This last quote is close to what Early worries about in Tuxedo Junction.

After leaving Satchmo at the Waldorf I asked myself: is this progress? I decided that it was. At the least, having a black man best known as a cheerful entertainer repeatedly curse at a mostly white audience is still mildly subversive. (Many reviewers of Waldorf are somehow surprised that Mr. Armstrong swore and smoked weed.)

In drama, clear antagonists are required. Terry has to make a story go. That should be fine, except that in Waldorf, fast-talking manager Joe Glaser is almost more interesting than doddering old Armstrong, and Miles Davis becomes a cartoon version of black nationalism.

To his credit, the portrayal of the Armstrong/Davis divide is much more nuanced in Terry's book Pops than in the play.

It's just good to remember how much Miles Davis must have loved Louis Armstrong. When Miles told Haley that Louis wasn't an influence, that just wasn't true. Trumpet playing aside, the whole concept of playing white show tunes in an improvisatory and black music context - i.e., the bulk of Miles Davis's recordings from the studio in the 50's and live in the 60's - comes straight from Louis Armstrong.

03/11/2014

Although Armstrong claimed to be born in 1900, various documents, notably a baptismal record, indicate that 1901 was his birth year. He grew up in dire poverty in New Orleans, Louisiana, when jazz was very young. As a child he worked at odd jobs and sang in a boys’ quartet. In 1913 he was sent to the Colored Waifs Home as a juvenile delinquent. There he learned to play cornet in the home’s band, and playing music quickly became a passion; in his teens he learned music by listening to the pioneer jazz artists of the day, including the leading New Orleans cornetist, King Oliver. Armstrong developed rapidly: he played in marching and jazz bands, becoming skillful enough to replace Oliver in the important Kid Ory band about 1918, and in the early 1920s he played in Mississippi riverboat dance bands.

Fame beckoned in 1922 when Oliver, then leading a band in Chicago, sent for Armstrong to play second cornet. Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band was the apex of the early, contrapuntal New Orleans ensemble style, and it included outstanding musicians such as the brothers Johnny and Baby Dodds and pianist Lil Hardin, who married Armstrong in 1924. The young Armstrong became popular through his ingenious ensemble lead and second cornet lines, his cornet duet passages (called “breaks”) with Oliver, and his solos. He recorded his first solos as a member of the Oliver band in such pieces as “

Chimes Blues” and “

Tears,” which Lil and Louis Armstrong composed.

Encouraged by his wife, Armstrong quit Oliver’s band to seek further fame. He played for a year in New York City in Fletcher Henderson’s band and on many recordings with others before returning to Chicago and playing in large orchestras. There he created his most important early works, the Armstrong Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings of 1925–28, on which he emerged as the first great jazz soloist. By then the New Orleans ensemble style, which allowed few solo opportunities, could no longer contain his explosive creativity. He retained vestiges of the style in such masterpieces as “

Hotter than That,” “

Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” “

Wild Man Blues,” and “

Potato Head Blues” but largely abandoned it while accompanied by pianist Earl Hines (“

West End Blues” and “

Weather Bird”). By that time Armstrong was playing trumpet, and his technique was superior to that of all competitors. Altogether, his immensely compelling swing; his brilliant technique; his sophisticated, daring sense of harmony; his ever-mobile, expressive attack, timbre, and inflections; his gift for creating vital melodies; his dramatic, often complex sense of solo design; and his outsized musical energy and genius made these recordings major innovations in jazz.

Armstrong was a famous musician by 1929, when he moved from Chicago to New York City and performed in the theatre review Hot Chocolates. He toured America and Europe as a trumpet soloist accompanied by big bands; for several years beginning in 1935, Luis Russell’s big band served as the Louis Armstrong band. During this time he abandoned the often blues-based original material of his earlier years for a remarkably fine choice of popular songs by such noted composers as Hoagy Carmichael, Irving Berlin, and Duke Ellington. With his new repertoire came a new, simplified style: he created melodic paraphrases and variations as well as chord-change-based improvisations on these songs. His trumpet range continued to expand, as demonstrated in the high-note showpieces in his repertoire. His beautiful tone and gift for structuring bravura solos with brilliant high-note climaxes led to such masterworks as “

That’s My Home,” “

Body and Soul,” and “

Star Dust.” One of the inventors of scat singing, he began to sing lyrics on most of his recordings, varying melodies or decorating with scat phrases in a gravel voice that was immediately identifiable. Although he sang such humorous songs as “

Hobo, You Can’t Ride This Train,” he also sang many standard songs, often with an intensity and creativity that equaled those of his trumpet playing.

Louis and Lil Armstrong separated in 1931. From 1935 to the end of his life, Armstrong’s career was managed by Joe Glaser, who hired Armstrong’s bands and guided his film career (beginning with Pennies from Heaven, 1936) and radio appearances. Though his own bands usually played in a more conservative style, Armstrong was the dominant influence on the swing era, when most trumpeters attempted to emulate his inclination to dramatic structure, melody, or technical virtuosity. Trombonists, too, appropriated Armstrong’s phrasing, and saxophonists as different as Coleman Hawkins and Bud Freeman modeled their styles on different aspects of Armstrong’s. Above all else, his swing-style trumpet playing influenced virtually all jazz horn players who followed him, and the swing and rhythmic suppleness of his vocal style were important influences on singers from Billie Holiday to Bing Crosby.

In most of Armstrong’s movie, radio, and television appearances, he was featured as a good-humoured entertainer. He played a rare dramatic role in the film New Orleans (1947), in which he also performed in a Dixieland band. This prompted the formation of Louis Armstrong’s All-Stars, a Dixieland band that at first included such other jazz greats as Hines and trombonist Jack Teagarden. For most of the rest of Armstrong’s life, he toured the world with changing All-Stars sextets; indeed, “Ambassador Satch” in his later years was noted for his almost nonstop touring schedule. It was the period of his greatest popularity; he produced hit recordings such as “

Mack the Knife” and “

Hello, Dolly!” and outstanding albums such as his tributes to W.C. Handy and Fats Waller. In his last years ill health curtailed his trumpet playing, but he continued as a singer. His last film appearance was in Hello, Dolly! (1969).

More than a great trumpeter, Armstrong was a bandleader, singer, soloist, film star, and comedian. One of his most remarkable feats was his frequent conquest of the popular market with recordings that thinly disguised authentic jazz with Armstrong’s contagious humour. He nonetheless made his greatest impact on the evolution of jazz itself, which at the start of his career was popularly considered to be little more than a novelty. With his great sensitivity, technique, and capacity to express emotion, Armstrong not only ensured the survival of jazz but led in its development into a fine art.

Armstrong’s autobiographies include Swing That Music (1936, reprinted with a new foreword, 1993) and Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans (1954).

http://dothemath.typepad.com/dtm/2014/03/louis-armstrong-and-miles-davis.html

Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis

Terry Teachout's play Satchmo at the Waldorf recently opened in New York. While obviously well-acted by John Douglas Thompson and successful with the audience, for me there wasn't enough unconditional love and respect for Mr. Louis Armstrong. This is also the theme of my essay about Terry's book on Duke, "Reverential Gesture."

I did appreciate Terry's biography of Armstrong, Pops. He's a true polymath (see our interview), and always considers jazz as part of American popular music. Those dedicated to jazz are often over-informed by insider knowledge, and it is refreshing to remember there's a whole wide world out there.

Even when I disagree with Terry it is grist for the mill. I was pulled up short by one aspect of Satchmo at the Waldorf: the portrayal of Miles Davis. After spending an afternoon with Google and my library, what I found was interesting enough to write up briefly for DTM.

---

I can't cite exact quotes from Satchmo at the Waldorf, but essentially Miles Davis appears as the "young angry black man" who thought Louis Armstrong was an Uncle Tom.

The fullest explication of the discordance between the civil rights era and Armstrong that I've seen is in Gerald Early's Tuxedo Junction:

The pain that one feels when Armstrong's television performances of the middle and late sixties are recalled is so overwhelming as to constitute an enormously bitter grief, a grief made all the keener because it balances so perfectly one's sense of shame, rage, and despair. The little, gnomish, balding, grinning black man who looked so touchingly like everyone's black grandfather who had put in thirty years as the janitor of the local schoolhouse or like the old black poolshark who sits in the barbershop talking about how those old boys like Bill Robinson and Jelly Roll Morton could really play the game; this old man whose trumpet playing was just, no, not even a shadowy, ghostly remnant of his days of glory and whose singing had become just a kind of raspy-throated guile, gave the appearance, at last, of being nothing more than terribly old and terribly sick. One shudders to think that perhaps two generations of black Americans remember Louis Armstrong, perhaps one of the most remarkable musical geniuses America ever produced, not only as a silly Uncle Tom but as a pathetically vulnerable, weak old man. During the sixties, a time when black people most vehemently did not wish to appear weak, Armstrong seemed positively dwarfed by the patronizing white talk-show hosts on whose programs he performed, and he seemed to revel in that chilling, embarrassing spotlight.

Early is writing in the late '80s, just before Wynton Marsalis and Stanley Crouch would gain traction with an alternative narrative. Wynton has said, "[Louis Armstrong] left an undying testimony to the human condition in the America of his time." For Stanley, Armstrong is, "One of the few who can be easily be mentioned with Stravinsky, Picasso and Joyce."

This narrative isn't always popular with contemporary jazzmen, who want more unreserved praise given to Miles Davis and John Coltrane when Wynton or Stanley appear on TV for a sound bite about jazz. For myself, I fervently hope that their narrative is closer to what young black kids learn today than the "silly Uncle Tom" narrative that worries Early.

---

People like beefs. Satchmo at the Waldorf includes Armstrong jousting with both Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis. Terry is very canny, and I'm certain that all the quotes are true, although it isn't explained that some of them are from years after Louis was dead.

Miles's appearances in Waldorf culminate in that remarkable bit of gallows humor from 1985 in Jet:

If somebody told me that I had an hour to live, I'd spend it choking a white man. I'd do it nice and slow.

Who am I to analyse Miles Davis? But I think he playing to the audience here. He wouldn't say that to DownBeat, he's saying it to Jet. (It reminds me of Armstrong being photographed with Amiri Baraka's Blues People in the pages of Ebony twenty years earlier.) If Miles makes you upset, you've fallen into his trap. Later on in the Jet piece, Davis says, "Those the shoe don't fit, well, those don't wear it."

Miles had a lot of facets. His support of Gil Evans and Bill Evans did the most of anybody to validate a kind of romantic or white sound in modern jazz. By 1985 all the editions of his band had had white players for years.

Anyway, back to beefs. According to Waldorf, Miles really gave Louis Armstrong a hard time. A casual search of the internet indicates this is common wisdom. (Rifftides; CBC; Daily Kos; Newsday; many more.)

Beefs are fun, but it is more helpful to see Afro-American jazz as a continuum. I was just listening to Miles Davis's E.S.P. and think that part of the trumpeter's solution to this hard new Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock music was to play Louis Armstrong quotes.

As far as I can discover from my library and the internet at this moment, the following is what Miles said about Louis Armstrong when he was alive:

1949: In DownBeat to Pat Harris, Miles says that Louis is one of his favorite musicians.

1955: In a DownBeat blindfold test with Leonard Feather, he listened to "Ain't Misbehavin'" with Bobby Hackett and Jack Teagarden. I believe the "statements" Miles refers to are Louis's putdowns of modern jazz.

I like Louis! Anything he does is all right. I don't know about his statements, though, I could do without them...I'd give it five stars.

1958: In the Jazz Review with Nat Hentoff, he listened to "Potato Head Blues":

Louis has been through all kinds of styles. That's good tuba, by the way. You know you can't play anything on a horn that Louis hasn't played - I mean even modern. I love his approach to the trumpet; he never sounds bad. He plays on the beat - with feeling. That's another phrase for swing. I also love the way he sings.

1962: In Playboy to Alex Haley:

I love Pops, I love the way he sings, the way he plays - everything he does, except when he says something against modern-jazz music. He ought to realize that he was a pioneer, too. No, he wasn't an influence of mine, and I've had very little direct contact with Pops. A long time ago, I was at Bop City, and he came in and told me he liked my playing. I don't know if he would even remember it, but I remember how good I felt to have him say it. People really dig Pops like I do myself. He does a good job overseas with his personality. But they ought to send him down South for goodwill. They need goodwill worse in Georgia and Alabama and Mississippi than they do in Europe.

Hyland Harris also sent me two candids, and you can see the respect Miles has on his face when greeting Pops.

Also from the book:

As much as I love Dizzy and loved Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong, I always hated the way they used to laugh and grin for the audiences. I know why they did it - to make money and because they were entertainers as well as trumpet players. They had families to feed. Plus they both liked acting the clown; it's just the way Dizzy and Satch were. I don't have nothing against them doing it if they want to. But I didn't like it and didn't have to like it...Also I was younger than them and didn't have to go through the same shit to get accepted by the music industry. They had already opened up a lot of doors for people like me to go through...

...

I loved the way Louis played trumpet, man, but I hated the way he had to grin in order to get over with some tired white folks. Man, I just hated when I saw him doing that, because Louis was hip, had a consciousness about black people, and was a real nice man. But the only image people have of him is that grinning image off TV.

This last quote is close to what Early worries about in Tuxedo Junction.

After leaving Satchmo at the Waldorf I asked myself: is this progress? I decided that it was. At the least, having a black man best known as a cheerful entertainer repeatedly curse at a mostly white audience is still mildly subversive. (Many reviewers of Waldorf are somehow surprised that Mr. Armstrong swore and smoked weed.)

In drama, clear antagonists are required. Terry has to make a story go. That should be fine, except that in Waldorf, fast-talking manager Joe Glaser is almost more interesting than doddering old Armstrong, and Miles Davis becomes a cartoon version of black nationalism.

To his credit, the portrayal of the Armstrong/Davis divide is much more nuanced in Terry's book Pops than in the play.

It's just good to remember how much Miles Davis must have loved Louis Armstrong. When Miles told Haley that Louis wasn't an influence, that just wasn't true. Trumpet playing aside, the whole concept of playing white show tunes in an improvisatory and black music context - i.e., the bulk of Miles Davis's recordings from the studio in the 50's and live in the 60's - comes straight from Louis Armstrong.

03/11/2014

February 25, 2014

What Louis Armstrong Really Thinks

by Ben Schwartz

The New Yorker

On October 31, 1965, Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong gave his first performance in New Orleans, his home town, in nine years. As a boy, he had busked on street corners. At twelve, he marched in parades for the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys, where he was given his first cornet. But he had publicly boycotted the city since its banning of integrated bands, in 1956. It took the Civil Rights Act, of 1964, to undo the law. Returning should have been a victory lap. At sixty-four, his popular appeal had never been broader. His recording of “Hello, Dolly!,” from the musical then in its initial run on Broadway, bumped the Beatles’ ”Can’t Buy Me Love” from its No. 1 slot on the Billboard Top 100 chart, and the song carried him to the Grammys; it won the 1964 Best Vocal Performance award. By the time the movie version came out, in 1969, he was brought in to duet with Barbra Streisand.

Armstrong was then widely known as America’s gravel-voiced, lovable grandpa of jazz. Yet it was a low point for his critical estimation. “The square’s jazzman,” the journalist Andrew Kopkind called him, while covering Armstrong’s return to New Orleans for The New Republic. Kopkind added that “Among Negroes across the country he occupies a special position as success symbol, cultural hero, and racial cop-out.” Kopkind was not entirely wrong in this, and hardly alone in saying so. Armstrong was regularly called an Uncle Tom.

Detractors wanted Armstrong on the front lines, marching, but he refused. He had already been the target of a bombing, during an integrated performance at Knoxville’s Chilhowee Park auditorium, in February, 1957. In 1965, the year Armstrong returned to New Orleans, Malcolm X was killed on February 21st, and on March 7th, known as Bloody Sunday, Alabama state troopers armed with billy clubs, tear gas, and bull whips attacked nearly six hundred marchers protesting a police shooting of a voter-registration activist near Selma. Armstrong flatly stated in interviews that he refused to march, feeling that he would be a target. “My life is my music. They would beat me on the mouth if I marched, and without my mouth I wouldn’t be able to blow my horn … they would beat Jesus if he was black and marched.”

When local kids asked Armstrong to join them in a homecoming parade, as he had done with the Colored Waif’s Home in his youth, he said no. He knew the 1964 Civil Rights Act was federal law, not local fiat. Armstrong had happily joined in the home’s parades in the past, but his refusal here can be read as a sign of the times. The Birmingham church bombings in 1963 had shown that even children were not off limits.

And yet little of what Armstrong said about the civil-rights struggle registered. The public image of him, that wide performance smile, the rumbling lilt of his “Hello, Dolly!,” obviated everything else. “As for Satchmo himself,” Kopkind wrote, “he seems untouched by all the doubts around him. He is a New Orleans trumpet player who loves to entertain. He is not very serious about art or politics, or even life.”

* * *

To be fair to Kopkind, and many others who wrote about Armstrong, they did not know much of what Armstrong thought, because, at the time, Armstrong’s more political views were rarely heard publicly. To the country at large, he insisted on remaining a breezy entertainer with all the gravitas of a Jimmy Durante or Dean Martin. Fortunately, that image is now being deeply reëxamined. This month, the publication of Thomas Brothers’s “Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism” and the Off Broadway opening of Terry Teachout’s “Satchmo at the Waldorf” (which follows his 2009 biography, “Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong,” which was reviewed in the magazine by John McWhorter) provide a rich, nuanced picture of what was behind Armstrong’s public face.

Armstrong’s thoughts were scattered about in uncollected letters, unpublished autobiographical manuscripts, and tape recordings. He brought a typewriter with him on the road, and an inquisitive fan who sent a letter stood a good chance of getting a reply from Satchmo himself. When reel-to-reel tape decks were introduced, he bought one so that he could listen to music, study his own performances, and record conversations with friends and family to get down his own version of events. Scholars and researchers have been studying his writing and recordings for a number of years. Teachout’s play, a one-man show starring John Douglas Thompson, is based on more than six hundred and fifty reels of tape stored at Queens College, all of which reveal an Armstrong who did indeed take art, politics, and life seriously.

His talk came from the streets, as did his understanding of race, celebrity, and politics. In 1951, when Josephine Baker returned to the United States from France, she complained publicly of racist treatment at New York’s Stork Club, and persuaded the Copa City night club, in Miami, to desegregate for her shows. Armstrong was not impressed. In 1952, according to a transcript in Ricky Riccardi’s “What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years” (2012), he said:

But she’s going to come over here and stir up the nation, get all them ofays—people that think a lot of us—against us, because you take a lot of narrow minded spades following up that jive she’s pulling—you understand?—then she go back with all that loot and everything and we’re over here dangling. I don’t dig her.

The key word is “we’re.” Armstrong grew up poor and powerless, and he never forgot it. Despite his fame, he understood the repercussions for a community after the celebrity savior jets home. “I don’t socialize with the top dogs of society after a dance or concert,” he said in a 1964 profile in Ebony. “These same society people may go around the corner and lynch a Negro.”

Armstrong chose his battles carefully. In September, 1957, seven months after the bombing attempt in Knoxville, he grew strident when President Eisenhower did not compel Arkansas to allow nine students to attend Little Rock Central High School. As Teachout recounts in “Pops,” here Armstrong had leverage, and spoke out. Armstrong was then an unofficial goodwill ambassador for the State Department. Armstrong stated publicly that Eisenhower was “two-faced” and had “no guts.” He told one reporter, “It’s getting almost so bad a colored man hasn’t got any country.” His comments made network newscasts and front pages, and the A.P. reported that State Department officials had conceded that “Soviet propagandists would undoubtedly seize on Mr. Armstrong’s words.”

Doing things Armstrong’s way, no one had to accept responsibility for his actions but Louis Armstrong. When Eisenhower did force the schools to integrate, Armstrong’s tone was friendlier. “Daddy,” he telegrammed the President, “You have a good heart.”

* * *

The work of Thomas Brothers, a professor of music at Duke University, radically undercuts the breezy image that Armstrong worked so hard to maintain. Brothers began editing Armstrong’s letters and writings in the early nineteen-nineties, now collected in “Louis Armstrong: In His Own Words.” He followed that with his own “Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans” (2006), and, this month, with “Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism,” which charts Armstrong’s peak creative period, from 1925 until 1932. It’s not so much biography that Brothers is after as a history of “black vernacular” music as seen through Armstrong’s life. In the book on New Orleans, he traces that music from plantation culture through Armstrong’s youth, and on to his move north, in 1922. “Master of Modernism” picks up as Armstrong’s mentor, Joe (King) Oliver, summons Armstrong to join his band in Chicago. Brothers discounts comforting histories of the early jazz world as an oasis where race was irrelevant, a multi-cultural melting pot that created a uniquely American sound. Armstrong’s music came from the black tradition, from his own neighborhood, which he modernized for Chicago’s upscale cafés, theatres, and fast-paced, flashy, urban clubs.

By 1925, after a three-year apprenticeship in Oliver’s band and, later, a stint in Fletcher Henderson’s group, Armstrong formed his Hot Fives and Hot Sevens combos. Here he perfected his mature horn style, a New Orleans sound broken down into what Brothers calls a “microscopic level of blues phrasing” sped up into a “dazzling melodic flow” of “weird, crazy, and eccentric figures.” Armstrong was part of the Great Migration, the movement of Southern African-Americans to Northern cities to escape Jim Crow terrorism. His local audiences were made up of many people in transition, just like him. “The connection to the Deep South could still be heard, but there was also a step up and forward into a more professional world,” Brothers writes. “He was a modern, sophisticated, northern, well-paid musician. Whether he knew it or not, the task that lay before him was to help his audience understand themselves more deeply by providing them with a musical identity that was black and modern. This is the context of his mature style.”

Brothers also convincingly dismisses the idea that Armstrong was a purely instinctive, improvisational artist, a lucky savant whom fortune favored with a cornet. In recently discovered copyrighted music for “Cornet Chop Suey,” which contains an early gem of a solo registered in 1924, but not recorded until 1926, Brothers shows that Armstrong was, in fact, an intellectual musician who composed his breakthrough solos. Of another solo, Brothers writes, “The chiseled perfection of ‘Big Butter and Egg Man’ came from working on it night after night, like a sculptor fussing over a chunk of marble. Armstrong changed the history of jazz solos by composing rather than improvising.”

The solos, with their incredibly fast breaks, their “freakish” (as traditionalists called them) squawks and “wah-wahs,” were considered pure noise, just novelty music, by many. Complaints from critics about Armstrong’s clowning dogged him all his life. But he made brilliant, satirical use of humor, which you can hear in his biggest hits of the twenties: “Heebie Jeebies,” “Big Butter and Egg Man,” and “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” In the first of that trio, Armstrong offers an early example of scat singing. He did not invent scat (as was mistakenly thought for decades), but here he popularized it by cheerfully mocking the song’s inane lyrics with his own nonsensical sound, one that flows along with the melody better than the original words.

His humor revealed an irreverent man with a distinctly black point of view. On “You’re Drivin’ Me Crazy,” from 1930, Armstrong stops the band momentarily to chide their sloppy performance. One musician answers, in a typical stuttering minstrel style, “Aw, Pops, w-we j-just m-muggin’ lightly.” Armstrong starts to answer in that stuttering style, too, then catches himself. “Aw, man, now you got me talkin’ all that chop suey.” Here Armstrong’s wisecrack undercuts a century of the minstrel humor expected of him by many white listeners, a simple joke making clear who Louis Armstrong really is.

By 1929, Armstrong was a cultural hero in Chicago. Yet his next innovation, his vocal style, raised questions about whether he was assimilating in order to attract white audiences (his “white turn,” as Brothers calls it) by recording pop hits that left his jazz fan base behind. In “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” a widely recorded song of the day, which Armstrong sang in the Broadway musical “Connie’s Hot Chocolates,” he takes a modernist’s approach of distancing himself from the source material, not assimilating. As he put it, “On the first chorus I plays the melody, on the second chorus I plays the melody around the melody, and on the third chorus I routines.” Like “Heebie Jeebies,” Armstrong irreverently comments on the song as much as plays it. His voice remains unassimilated, as well. As Brothers puts it, he sang with “a voice as different from the normative style of Broadway show singing as black and white … mixing scat, blues, double-time, and witty paraphrase, keeping things humorous and accessible.” A voice that made Armstrong’s “Ain’t Misbehavin’ ” a distinctly black mainstream hit, and one heard all the way through “Hello, Dolly!”

“That he was not interested in cultural assimilation is an indication of psychological security and confidence,” Brothers writes in “Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans.” “It may also be taken as a political stance. To insist on the value of vernacular culture and to reject assimilation was not an idle position to take. There were considerable ideological pressures working in the other direction.”

Yes, unfortunately, there were. One example, of too many, came when Armstrong was arrested by the Memphis Police Department in 1931. His crime? He sat next to his manager’s wife, a white woman, on a bus. Armstrong and his band were thrown in jail as policemen shouted that they needed cotton pickers in the area. Armstrong’s manager got him out in time to play his show the next evening. When he did play, Armstrong dedicated a song to the local constabulary, several of whom were in the room, then cued the band to play “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Old Rascal You.” The band stiffened, expecting another night in jail, or worse. Instead, he scatted so artfully that, afterward, the cops on duty actually thanked him. Armstrong most likely never quit smiling that night. His subversive joke was not understood by anyone except the African-Americans in his band.

Race pervaded every aspect of Armstrong’s career. After he began making movies, he was given an embarrassing jungle outfit to wear in “A Rhapsody in Black and Blue” (1932), a betrayal of everything in his music. Brothers likens the ideology of nineteen-thirties racism that Armstrong lived under to what other musical geniuses suffered overseas at the time:

In Russia, Dmitri Shostakovich came under attack for composing music that did not fit official Soviet expectations; his efforts to make up for such “errors” in artistic judgment lay at the root of a tortured life. Richard Strauss’s German-themed compositions were easily appropriated by the Nazis, boxing him into an image that he wanted nothing do with.

Armstrong, in his own way, made that same point. During the Little Rock schools standoff, he cancelled a planned tour of the Soviet Union for the State Department. As Teachout quotes him in “Pops,” “The people over there ask me what’s wrong with my country? What am I supposed to say?” Yes, Armstrong compromised. “If he was going to advance further on the ladder of his career—and he definitely was—he had to assure white audiences on a deep level that he had no designs on social progress,” Brothers writes.

But, in fact, he did, which we see now in his art and in his racial politics, from his interactions with the Memphis police in 1931 and Eisenhower in 1957 to his return in 1965 to New Orleans, without grandstanding or incident. As the pieces come together, a consistency of thought in Armstrong once obscured to us has finally become clear: “You name the country and we’ve just about been there,” he said of his travels with his wife Lucille. “We’ve been wined and dined by all kinds of royalty. We’ve had an audience with the Pope. We’ve even slept in Hitler’s bed. But regardless of all that kind of stuff, I’ve got sense enough to know that I’m still Louis Armstrong—colored.”

Ben Schwartz is an Emmy-nominated comedy writer and the editor of the anthology “The Best American Comics Criticism.” He is currently working on a history of American humor set between the world wars.

Photograph: Eddie Adams/AP

ne

of the greatest jazz musicians of all time, Louis Armstrong was

responsible for innovations that filtered down through popular music to

rock and roll. Armstrong himself put it like this: “If it hadn’t been

for jazz, there wouldn’t be no rock and roll.” If it hadn’t been for

Armstrong, popular music of all kinds – from jazz and blues to rock and

roll – would be considerably poorer. As a trumpet player, Armstrong was a

pioneering soloist and one of the first true virtuosos in jazz. As a

singer, he was one of the originators of scat singing, and his warm,

ebullient vocal style had a big impact on the way all pop music was

sung. As an entertainer, his charismatic presence allowed him to break

through race barriers to become one of the first black superstars – a

figure who would eventually become known as America’s Jazz Ambassador.

Louis Armstrong was born in New Orleans on August 4, 1901. While still a teenager, he and three friends formed a vocal quartet. “I used to sing tenor,” he recalled. “Had a real light voice, and played a little slide whistle, like a trombone.” On New Year’s Eve 1912, he was arrested after he fired some shots from his stepfather’s gun. He was sent to the Colored Waifs’ Home. There, he began playing cornet in a brass band. Five years later, he was playing honky-tonks. Another cornetist, Joe “King” Oliver, took a liking to him, and in 1922, he brought Armstrong to Chicago.