SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

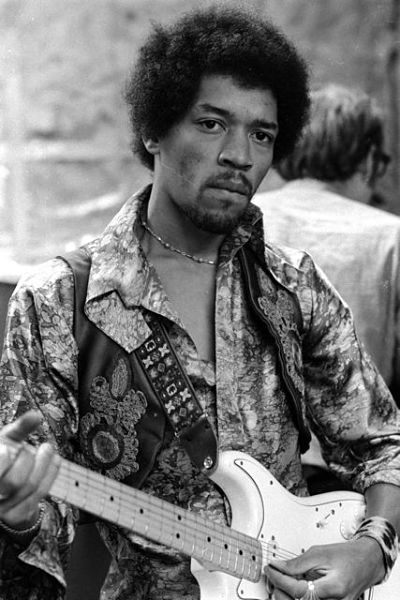

JIMI HENDRIX

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LAURA MVULA

October 10-16

DIZZY GILLESPIE

October 17-23

LESTER YOUNG

October 24-30

TIA FULLER

October 31-November 6

ROSCOE MITCHELL

November 7-13

MAX ROACH

November 14-20

DINAH WASHINGTON

November 21-27

BUDDY GUY

November 28-December 4

JOE HENDERSON

December 5-11

HENRY THREADGILL

December 12-18

MUDDY WATERS

December 19-25

B.B. KING

December 26-January 1

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/muddy-waters-mn0000608701/biography

MUDDY WATERS

Artist Biography by Mark Deming

Muddy Waters was the single most important artist to emerge in post-war American blues. A peerless singer, a gifted songwriter, an able guitarist, and leader of one of the strongest bands in the genre (which became a proving ground for a number of musicians who would become legends in their own right), Waters absorbed the influences of rural blues from the Deep South and moved them uptown, injecting his music with a fierce, electric energy and helping pioneer the Chicago Blues style that would come to dominate the music through the 1950s, ‘60s, and '70s. The depth of Waters' influence on rock as well as blues is almost incalculable, and remarkably, he made some of his strongest and most vital recordings in the last five years of his life.

Waters was born McKinley Morganfield, and historians argue about some details of his early life; while he often told reporters he was born in Rolling Fork, Mississippi on April 4, 1915, researchers have uncovered census records and personal documents that would pin the year of his birth at 1913 or 1914, and others have cited the place of his birth as Jug's Corner, a town in Mississippi's Issaquena County. What is certain is that Morganfield's mother died when he just three years old, and from then on he was raised on the Stovall Plantation in Clarksdale, Mississippi by his grandmother, Della Grant. Grant is said to have given young Morganfield the nickname "Muddy" because he liked to play in the mud as a boy, and the name stuck, with "Water" and "Waters" being tacked on a few years later. The rural South was a hotbed for the blues in the '20s and ‘30s, and young Muddy became entranced with the music when he discovered a neighbor had a phonograph and records by the likes of Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, and Tampa Red.

As Muddy became more deeply immersed in the blues, he took up the harmonica; he was performing locally at parties and fish fries by the age of 13, sometimes with guitarist Scott Bohanner, who lived and worked in Stovall. In his early teens, Muddy was introduced to the sound of contemporary Delta blues artists, such as Son House, Robert Johnson, and Charley Patton; their music inspired Waters to switch instruments, and he bought a guitar when he was 17, learning to play in the bottleneck style. Within a few years, he was performing on his own and with a local string band, the Son Simms Four; he also opened a juke joint on the Stovall grounds, where fellow sharecroppers could listen to music, enjoy a drink or a snack, and gamble. Waters became a fixture in Mississippi, performing with the likes of Big Joe Williams and Robert Nighthawk, and in the late summer of 1941, musical archivists Alan Lomax and John Work III arrived in Mississippi with a portable recording rig, eager to document local blues talent for the Library of Congress (it's said they were hoping to locate Robert Johnson, only to learn he had died three years earlier). Lomax and Work were strongly impressed with Waters, and recorded several sides of him performing in his juke joint; two of the songs were released as a 78, and when Waters received two copies of the single and $20 from Lomax, it encouraged him to seriously consider a professional career. In July 1943, Lomax returned to record more material with Waters; these early sessions with Lomax were collected on the album Down On Stovall's Plantation in 1966, and a 1994 reissue of the material, The Complete Plantation Recordings, won a Grammy award.

In 1943, Waters decided to pull up stakes and relocate to Chicago, Illinois in hopes of making a living off his music. (He moved to St. Louis for a spell in 1940, but didn't care for it.) Waters drove a truck and worked at a paper plant by day, and at night struggled to make a name for himself, playing house parties and any bar that would have him. Big Bill Broonzy reached out to Waters and helped him land better gigs; Muddy had recently switched to electric guitar to be better heard in noisy clubs, which added a new power to his cutting slide work. By 1946, Waters had come to the attention of Okeh Records, who took him into the studio to record but chose not to release the results. A session that same year for 20th Century Records resulted in just one tune being issued as the B-side of a James "Sweet Lucy" Carter release, but Waters fared better with Aristocrat Records, a Chicago-based label founded by brothers Leonard and Phil Chess. The Chess Brothers began recording Waters in 1947, and while a few early sides with Sunnyland Slim failed to make an impression, his second single for Aristocrat as a headliner, "I Can't Be Satisfied" b/w "(I Feel Like) Goin' Home," became a significant hit and launched Waters as a star on the Chicago blues scene.

Initially, the Chess Brothers recorded Waters with trusted local musicians (including Earnest "Big" Crawford and Alex Atkins), but for his live work, Waters had recruited a band which included Little Walter on harmonica, Jimmy Rogers on guitar, and Baby Face Leroy Foster on drums (later replaced by Elgin Evans), and in person, Waters and his group earned their reputation as the most powerful blues band in town, with Waters' passionate vocals and guitar matched by the force of his combo. By the early '50s, the Chess Brothers (who had changed the name of their label from Aristocrat to Chess Records in 1950) began using Waters' stage band in the studio, and Little Walter in particular became a favorite with blues fans and a superb foil for Waters. Otis Spann joined Waters' group on piano in 1953, and he would become the anchor for the band well into the '60s, after Little Walter and Jimmy Rogers had left to pursue solo careers. In the '50s, Waters released some of the most powerful and influential music in the history of electric blues, scoring hits with numbers like "Rollin' and Tumblin,'" "I'm Ready," "I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man," "Mannish Boy," "Trouble No More," "Got My Mojo Working," and "I Just Want to Make Love to You" which made him a frequent presence on the R&B charts.

By the end of the '50s, while Waters was still making fine music, his career was going into a slump. The rise of rock & roll had taken the spotlight away from more traditional blues acts in favor of younger and rowdier acts (ironically, Waters had headlined some of Alan Freed's early "Moondog" package shows), and Waters' first tour of England in 1958 was poorly received by many U.K. blues fans, who were expecting an acoustic set and were startled by the ferocity of Waters' electric guitar. Waters began playing more acoustic music informed by his Mississippi Delta heritage in the years that followed, even issuing an album titled Muddy Waters: Folk Singer in 1964. However, the jolly irony was that British blues fans would soon rekindle interest in Waters and electric Chicago blues; as the rise of the British Invasion made the world aware of the U.K. rock scene, the nascent British blues scene soon followed, and a number of Waters' U.K. acolytes became international stars, such as Eric Clapton, John Mayall, Alexis Korner, and a modestly successful London act who named themselves after Muddy's 1950 hit "Rollin' Stone." While Waters was still leading a fine band that delivered live (and included the likes of Pinetop Perkins on piano and James Cotton on harmonica), Chess Records was moving more toward the rock, soul, and R&B marketplace, and seemed eager to market him to white rock fans, a notion that reached its nadir in 1968 with Electric Mud, in which Waters was paired up with a psychedelic rock band (featuring guitarists Pete Cosey and Phil Upchurch) for rambling and aimless jams on Waters' blues classics. 1969's Fathers and Sons was a more inspired variation on this theme, with Waters playing alongside reverential white blues rockers such as Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield; 1971's The London Muddy Waters Sessions was less impressive, featuring fine guitar work from Rory Gallagher but uninspired contributions from Steve Winwood, Rick Grech, and Georgie Fame.

Curiously, while Chess Records helped Waters make some of the finest blues records of the '50s and ‘60s, it was the label's demise that led to his creative rebirth. In 1969, the Chess Brothers sold the label to General Recorded Tape, and the label went through a long, slow commercial decline, finally folding in 1975. (Waters would become one of several Chess artists who sued the label for unpaid royalties in its later years.) Johnny Winter, a longtime Waters fan, heard the blues legend was without a record deal, and was instrumental in getting Waters signed to Blue Sky Records, a CBS-distributed label that had become his recording home. Winter produced the sessions for Waters' first Blue Sky release, and sat in with a band comprised of members of Waters' road band (including Bob Margolin and Willie "Big Eyes" Smith) along with James Cotton on harp and Pinetop Perkins on piano. 1977's Hard Again was a triumph, sounding as raw and forceful as Waters' classic Chess sides, with a couple extra decades of experience informing his performances, and it was rightly hailed as one of the finest albums Waters ever made while sparking new interest in his music. (It also earned him a Grammy award for Best Traditional or Ethnic Folk Recording.) Waters also dazzled music fans when he appeared at the Band's celebrated farewell concert on Thanksgiving 1976 at the invitation of Levon Helm, who had helped produce one of his last Chess releases, The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album. Muddy delivered a stunning performance of "Mannish Boy" that became one of the highlights of Martin Scorsese's 1978 concert film The Last Waltz. Between Hard Again and The Last Waltz, Waters enjoyed a major career boost, and he found himself touring again for large and enthusiastic crowds, sharing stages with the likes of Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones, and cutting two more well-received albums with Winter as producer, 1978's I'm Ready and 1981's King Bee, as well as a solid 1979 concert set, Muddy "Mississippi" Waters Live. Waters' health began to fail him in 1982, and his final live appearance came in the fall of that year, when he sang a few songs at an Eric Clapton show in Florida. Waters died quietly of heart failure at his home in Westmont, Illinois on April 30, 1983. Since then, both Chicago and Westmont have named streets in Muddy's honor, he's appeared on a postage stamp, a marker commemorates the site of his childhood home in Clarksdale, and he appeared as a character in the 2008 film Cadillac Records, played by Jeffrey Wright.

https://rockhall.com/inductees/muddy-waters/bio/

MUDDY WATERS BIOGRAPHY

Muddy Waters

(vocals, guitar; born April 4, 1913, died April 30, 1983)

Muddy Waters transformed the soul of the rural South into the sound of the city, electrifying the blues at a pivotal point in the early postwar period. His recorded legacy, particularly the wealth of sides he cut in the Fifties, is one of the great musical treasures of this century. Aside from Robert Johnson, no single figure is more important in the history and development of the blues than Waters. The real question as regards his lasting impact on popular music isn’t “Who did he influence?” but - as Goldmine magazine asked in 2001 - “Who didn’t he influence?”

Above all others, it was Waters who linked the country blues of his native Mississippi Delta with the urban blues that were born in Chicago. Waters bought his first electric guitar in 1944 and revolutionized the blues with the recordings he began making in 1948. His amplified combo consisted of himself on slide guitar and vocals, a second guitarist, bass, drums, piano and harmonica. The Muddy Waters Blues Band bore all the earmarks - in terms of size, volume and attitude - of the great rock and roll bands that would follow in its wake.

He was born McKinley Morganfield in Rolling Fork, Mississippi, in 1915. At the age of three he was sent to live with his grandmother, on the Stovall Plantation north of Clarksdale, after his mother died. There he acquired the nickname “Muddy” for his penchant for playing in nearby creeks and puddles. Waters began playing harmonica at the age of seven and took up guitar at seventeen. He picked cotton on the plantation for fifty cents a day and played music as part of a trio at fish fries and house parties on weekends. Folklorist Alan Lomax, while making field recordings for the Library of Congress, tracked down and recorded Waters in 1941 on the Stovall Plantation, near Clarksdale, Miss. Several of these performances were released on Library of Congress anthologies and stand as his first recordings. In May 1943, Waters made the move from the rural plantation to the big city, heading north to Chicago by train.

Waters’ approach to the blues underwent a dramatic metamorphosis after moving to Chicago, where he befriended and played with such estimable figures as Big Bill Broonzy and John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson. Waters switched from acoustic to electric guitar in order to be heard over the din of patrons at the clubs he played on Chicago’s South Side. After a few false starts, Waters’ recording career began in earnest soon after pianist Sunnyland Slim introduced him to Leonard Chess, co-owner of the Aristocrat label (later Chess Records). Working at the famed Chess Studios on South Michigan Avenue, Waters cut many of the greatest recordings in the blues canon. He developed a fruitful team approach to record-making with producer Leonard Chess, bassist/songwriter Willie Dixon, and various musical associates.

In a relaxed, informal studio setting Waters and band laid down a string of citified, plugged-in electric blues that bore the rustic stamp of their Mississippi Delta underpinnings. A flood of blues-standards-to-be from Waters commenced with the 1948 release of “I Can’t Be Satisfied,” a raw, uncut Delta blues. Other classic sides included songs written for Waters by Willie Dixon ("I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man,” “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “I’m Ready") and by Waters himself (“Mannish Boy,” “Rollin’ and Tumblin’").

Waters was a fierce singer and slashing slide guitarist whose uncut blues bore the stamp of his mentors, Robert Johnson and Son House. For his own part, Waters served to mentor or at least launch many prominent blues musicians, many of whom went on to careers as bandleaders in their own right. The list of notable musicians who passed through Waters’ band includes harmonica players “Little Walter” Jacobs, “Big Walter” Horton, Junior Wells and James Cotton; guitarists Jimmy Rogers, Pat Hare, Luther Tucker and Earl Hooker; pianists Memphis Slim, Otis Spann and Pinetop Perkins; and drummers Elgin Evans, Fred Below and Francis Clay.

Waters’ greatest studio recordings were released as singles during the Fifties, and his first album - a collection of singles entitled The Best of Muddy Waters - didn’t appear until 1958. The Sixties found Waters performing to an ever-widening and appreciative audience as the younger generation acquired an insight into rock and roll’s essential grounding in the blues. In 1960, Waters performed a fiery, unforgettable set at the Newport Folk Festival, released that same year as Muddy Waters at Newport.

Waters also capitalized on the folk-music craze of the late Fifties and early Sixties with a series of albums that found him assaying acoustic blues on such albums as Muddy Waters Sings Big Bill (a tribute to rural bluesman Big Bill Broonzy, released in 1960), Muddy Waters, Folk Singer (1964) and The Real Folk Blues (1966). Less successful were attempts to contemporize his sound with such ill-advised efforts as “Muddy Waters Twist” (a 1962 single) and Electric Mud (an album of psychedelic blues from 1968). More satisfying by far were a couple of albums - Fathers and Sons (1969) and The London Muddy Waters Sessions (1972) - that found Waters accompanied by such vanguard rock musicians as Mike Bloomfield and Eric Clapton. His thirty-year tenure with Chess Records ended in 1975 with the release of The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album. From here, he moved to the Blue Sky label (a Columbia subsidiary).

Waters’ audience grew exponentially following his electrifying performance in The Last Waltz, a film documentary (produced by Martin Scorsese) of The Band’s farewell concert. Staged at San Francisco’s Winterland ballroom, the Thanksgiving 1976 event was a star-studded affair. Water’s scalding rendition of “Mannish Boy” - on which he was accompanied by The Band and Paul Butterfield on harmonica - was an unforgettable highlight. Subsequent to that, he kept the momentum going with a series of uncompromising albums for Blue Sky that were produced by longtime fan Johnny Winter. These included Hard Again (1977), I’m Ready (1978), Muddy Mississippi Waters Live (1979) and King Bee (1981). All were critical and popular successes.

In addition to his musical legacy, Waters helped cultivate a great respect for the blues as one of its most commanding and articulate figureheads. Drummer Levon Helm of The Band, who worked with him on The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album and at The Last Waltz, had this to say about him in a Goldmine magazine interview: “Muddy taught us to take things in context, to be respectful, and to be serious about our music, as he was. He showed us music is a sacred thing.”

Waters, who remained active till the end, died of a heart attack in 1983. He was 68 years old. In the years since his death, the one-room cedar shack in which he lived on the Stovall Plantation has been preserved as a memorial to Waters’ humble origins

See more at: https://rockhall.com/inductees/muddy-waters/bio/#sthash.Wa95U08w.dpuf

http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/muddy-waters-the-delta-son-never-sets-19781005

RS 275

The original 'Rollin' Stone' on a life with the blues

by Robert Palmer

October 5, 1978

Rolling Stone

Muddy Waters, the master bluesman, is now sixty-three. He lives out in the suburbs, almost an hour's drive from downtown Chicago and the decaying South Side where he lived for the past three decades. His white, two-story frame house sits on a quiet corner, shaded by pine trees, with nothing to let a visitor know who owns it except the small, circumspect initials MW on the front door. Inside, it's comfortable: deep carpeting in the living room, modern furniture, a big, all-electric kitchen with grandchildren and neighbors' kids constantly running through it. A few dogs, brought from the South Side where they were protectors, sleep lazily by the toolshed. It's not a pop star's house by any stretch of the imagination, but it's the kind of house very, very few of Chicago's approximately 1.5 million black people will ever own.

Muddy, who is beginning to show his age but remains a wholly commanding presence with his high cheekbones, half-lidded Oriental eyes and undiminished aura of mannish self-confidence – ''I'm a full-growed man,'' he sings, ''a natural-born lover man,'' and you believe him – takes a visitor through the house matter-of-factly, with just a hint of pride. In the small anteroom to the den he points out framed portraits of former sidemen Little Walter and James Cotton, and in the little garden patches around the house and by the concrete driveway, he indicates his cabbage, his greens, his red and green chili peppers and his okra. He doesn't brag about his successes, one suspects, because he knows he deserves them. But he certainly couldn't have imagined it all when he first got off the Illinois Central train in Chicago, back in May 1943. Except for a brief and not very satisfactory sortie to St. Louis and a few quick visits to Memphis, he had not traveled beyond the countryside and small towns of the Mississippi Delta, and he was twenty-eight years old.

The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time: Muddy Waters

Sunnyland Slim, the pianist and singer who got Muddy his first record date with Leonard and Phil Chess in 1947, is working in the heart of the South Side, 61st and Calumet under the El stop. To find Slim, you walk into Morgen's Liquors' front door, down the bar in the middle, into the boisterous music room in the rear. Slim is sitting at a battered, red Wurlitzer electric piano, rapping out tone clusters in the treble and walking the basses with all the authority of his sixty-odd years playing blues, while Louis Myers, the leader of the band and once the guitarist in Little Walter's celebrated Aces, sings blues standards.

''I don't like to play in these kind of places no more,'' Slim says during a break, sipping from a glass of booze and pushing his weathered face up close so he can be heard over the buzz of conversation and the B.B. King record on the jukebox. ''I'll be seventy-six soon. I've just been out to California, Europe. . . . I'm just down here helping Louis out.'' He knows the subject of the conversation is supposed to be Muddy, and like Muddy, he is a proud man. ''You want to know what made Muddy popular? Leonard Chess pushed him. At that time, see, they was still playing the blues on the radio, not like it is now. Those first records he had out, a whole bunch of us had been doin' that rockin' style for years. I brought him in to play guitar for me, on that session when I made 'Johnson Machine Gun.' The man asked me, 'Say, what about your boy there, can he sing?' Talking about Muddy, you know. And I said, 'Like a bird.'''

Later, over on the North Side in a white singles bar with pinball machines and pizza, Jimmy Rogers, second guitarist on Muddy's classic blues records of the early Fifties, is setting up for a gig with the brilliant but erratic harmonica virtuoso Walter Horton. ''Muddy,'' says Rogers, ''Muddy has a whole lot of soul. Maybe it's not the words that he says so much as the way that he says 'em. He has a voice that I haven't heard anybody could imitate. They can copy his slide style of guitar, but when the voice comes in, that's different. I know his voice anywhere I hear it.''

Willie Dixon, the blues bassist, songwriter and producer, sums up peer-group opinion in a few characteristically well-chosen words: ''Everybody liked him 'cause he could really howl those blues.''

What was it about Muddy that made him so widely respected and admired, that made his blues, in his own words, ''deeper'' than the blues of his competitors? Leonard Chess did push Muddy, but he was pushing a man with extraordinary musical gifts and an extraordinary feeling for the blues.

Conventional wisdom has it that blues melodies consist of five, six or seven pitches or notes, with the third and seventh and sometimes the fifth notes of the scale being treated a little funny, flattened but not quite as flat as the black keys on the piano; these are the ''blue notes.'' But if you listen carefully to Muddy, or to any other really deep blues singer, you'll find that he systematically sings the third and, especially, the fifth notes of the scale infintesimally flatter or sharper, depending on where in the line the pitches fall and on the feelings he's trying to convey.

Muddy is the living master of these subtleties. He gets them on guitar too – listen to his slide solo on ''Honey Bee,'' on the Chess/All-Platinum Muddy Waters reissue, for example – and he's aware of getting them. ''Yeah, yeah,'' he says when he is accused of playing microtones, or notes that would fall between the cracks on the piano. ''When I plays on the stage with my band, I have to get in there with my guitar and try to bring the sound down to me. But no sooner than I quit playing, it goes back to another, different sound. My blues look so simple, so easy to do, but it's not. They say my blues is the hardest blues in the world to play.''

The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time: Muddy Waters

Subtle as these inflections are, young guitarists can at least hope to learn to hear and execute them properly. But as Slim and Rogers and Dixon all noted, Muddy's great strength is his singing, something nobody has been able to duplicate. In addition to his mastery of pitch shadings, he also commands some remarkable textural effects. You can see him in Martin Scorsese's film The Last Waltz, screwing up the side of his face, shaking his jowls, constantly readjusting the shape of his mouth in order to get specific vocal sounds. And his timing is a kind of standing joke among musicians who have played with him. ''I'm a delay singer,'' he says. ''I don't sing on the beat. I sing behind it. And people have to delay to play with me. They got to hang around, wait, see what's going to happen next.''

Muddy's sovereign control of these techniques – how many other bluesmen have had comparable mastery of them? Son House? Robert Johnson? Charley Patton? – goes a long way toward explaining the absolute, unquestioned authority he radiates. It's evident that he didn't learn them in school. They could be taught, if the teacher knew them as well as Muddy does and the student were willing to put in as much time and hard work as it takes to become, say, a first-class opera diva. But in the Delta the learning process, while no less rigorous, was more diffuse.

It's important to remember that Muddy was already an established bluesman when Robert Johnson made the first of his own keening, driven recordings in 1936. In fact, Muddy was already known in Chicago. Willie Dixon, who settled in the Windy City that same year, remembers that when talk got around to serious blues singing, people from the Delta invaribly brought up Muddy. Although he heard phonograph records, the way he learned his music and the environment in which he learned it – two sides of the same coin – were almost entirely traditional.

Since Muddy was a fully formed musician by the time he arrived in Chicago, it seemed important to talk about his formative years as thoroughly as possible, and this is what we did, sitting at his kitchen table sipping Piper Heidsieck champagne and Coca Cola. He was a little reticent at first, but soon he began recalling Mississippi scenes in more detail and really enjoying himself. We rambled through that fated countryside for hours. At times the dogs in back of the house would begin to bay like hounds; Bo, his man who grew up with him on the plantation, would say something to the children in his almost impenetrable Delta accent; a suggestion of a warm breeze would waft in the screen door, and we would be there.

Muddy was born McKinly Morganfield in Rolling Fork, Mississippi, April 4th, 1913. He doesn't remember anything about his parents cabin because when he was a baby his mother carried him to the country near Clarksdale, where her mother raised him. He got the nickname Muddy right away because he liked to crawl around in the mud and tried to eat it.

His grandmother lived three or four miles outside Clarksdale, on a huge plantation owned by the Stovall family. Not even white folks in the Delta had electricity in those days, and water came from a pump. Every day the able-bodied members of that household went out to work in the cotton fields. Nominally, they were farming the Stovalls' land and sharing in the proceeds from the crop. But since the Stovalls kept the books and charged the black families for seed and provisions from the plantation store, the sharecroppers usually ended up in debt after the year's tally. Men could also work for salaries, picking or chopping cotton or, later, driving a tractor. Families could raise their own vegetables and livestock to eat, milk or sell. But it was still a rough, precarious existence, one that depended on the notorious vagaries of Delta weather as much as it did on any human agency.

As far as Muddy can remember, he was born musical. ''When I was around three years old I was beatin on bucket tops and tin cans. Anything with a sound I would try to play it; I'd even take my stick and beat on the ground tryin' to get a new sound. [He still likes mud and earth. Even today, nothing seems to relax Muddy as much as getting down on his hands and knees and digging in his garden.] And whatever I beat on, I'd be hummin' my little baby song along with it. My first instrument, which a lady give me and some kids soon broke for me, was an old squeeze-box, an accordion. The next thing I had in my hand was a jew's-harp. When I was about seven I started playing the harmonica, and when I got about thirteen I was playing it very good. I should never have give it up! But when I was seventeen I switched to the guitar and put the harp down. I sold our last horse for the first guitar I had. Made fifteen dollars for him, gave my grandmother $7.50, I kept $7.50 and paid about $2.50 for my guitar.''

Even before he bought the guitar, Muddy was playing at country suppers and fish fries for pocket change, blowing his harp along with a guitarist friend named Scott. But once he had the guitar in his hands, Muddy learned fast. The basic Delta bluse repertoire – songs like ''Catfish Blues,'' which became the basis for Muddy's ''Rollin' Stone,'' or ''Dark Road Blues'' or ''Walkin' Blues'' – was readily accessible, since anybody who fooled with a guitar was able more or less to get through them. For fine points, there were masters to emulate: ''Charley Patton? He had so much showmanship in his thing, all this wild clownin' with the guitar, and he could holler! Ooh, what a voice. But Son House was the top man in my book. I always did like the bottleneck style, and he was the man doin' that then. And he had the kind of singing I liked, that preaching kind of singing.''

Son House occasionally renounced the blues and preached in churches, though never for very long until he left Mississippi. I wondered if Muddy went to church. ''Yes sir,'' he said, ''can't you hear it in my voice? Plenty of people would stay up all night and listen to the blues and go home, get ready and go to church. Back then, there was three things I wanted to be: a heck of a preacher, a heck of a ballplayer or a heck of a musician.''

When Muddy was twelve or thirteen, a neighbor bought a record player. and he began spending hours at her house, listening to Memphis Minnies ''Bumble Bee'' (the basis of his ''Honey Bee''), Lonnie Johnson's ''Careless Love'' and Pattons ''Pony Blues.'' When he took up the guitar, the first two songs he learned were from records: ''How Long Blues'' by Leroy Carr, a blues pianist who lived in Indianapolis, and ''Sittin' on Top of the World'' by a black string band, the Mississippi Sheiks. He played both of them with a slide, translating relatively urbane pieces into a stark, insistent Delta style.

Muddy never looked back once he established himself locally as a musician. ''I didn't like farming,'' he said. ''I always expected my guitar could beat driving tractors, plowing mules, chopping cotton, drawing water. Sometimes they'd want us to work Saturday, but – and Bo here can witness this – they'd look for me and I'd be gone, playing my guitar in the little town or in some juke joint. Was I a rambler? I rambled all the time. That's why I added that verse about the rollin' stone to 'Catfish Blues' and named it 'Rollin' Stone.' I was just like that, like a rollin' stone.'' Muddy recorded his classic rambler's boast in 1950. It furnished the name for the rock & roll band and for this magazine, ''But I didn't ramble that far,'' Muddy added. ''I was in love with my grandmother, she was getting old, and I didn't want to push out and leave her.''

Muddy married when he was eighteen. His bride was around seventeen, and they both had to lie about their ages at the Clarksdale courthouse. Since Muddy now had more responsibilities and less reason to ramble, his next move was to go into the Saturday night business for himself. ''First I'd have my own Saturday night dances. I got hip and started making and selling my own whiskey, playing for myself. I had my little crap table going in the back. I'd put coal oil in bottles, take a rope and hang 'em up there on the porch to let people know my dance was going on, and I had a lot of them lights for people to gamble by. Its pretty hard to see the dice sometimes in that lamplight. They had some fast boys with the dice down there; you had to have good eyes.''

You had to have more than that. Most gamblers carried a pistol, as Muddy did off and on for years, and most had good-luck charms made by local hoodoo doctors. Sometimes a really successful gambler would disappear for a few days or weeks and reappear with a charm he claimed to have purchased in the South's most powerful hoodoo center, New Orleans. ''We all believed in mojo hands, which is a luck charm. If you were gambling, the mojo would take care of that, you'd win, and the woman you want, you could work that on her and win. I won some money one night, so I went off and bought me a three-dollar mojo.

''The mojo doctor's hair was real white, he was a long, tall guy. He looked weird, and he had weird little tingalings hanging in his office. He got a little piece of paper, had writing on it, and he rolled it up right, sealed it in an envelope, put some perfume on the envelope. And you know what? It was five years before I won another quarter.'' Bo, who was frying some shrimp, exploded with laughter. ''Then I got mad, I got broke once in a crap game and decided I'm gonna open it and see what's in it, and it was just some little writing: 'You win, you win, you win, I win, you win, I win.' I had it read to me. It's just a con game on people's heads, you know, getting the fools. If such a thing as a mojo had've been good, you'd have had to go down to Louisiana to find one. They could have had a few things down in Louisiana doing something. But up in the Delta, nothing, I don't think.''

Muddy expanded from occasional Saturday night dances to a regular operation. By the early Forties he was running his own juke house, with a policy wheel for serious gambling, one of the new jukeboxes, his moonshine whiskey and music. Sometimes he played there alone, blowing a kazoo mounted in a neck rack and bearing down heavily on his guitar to keep people dancing. ''They'd be doing the snake hips, working their butts, you know, and all those old dances, and hollering, 'Ooh shit, play it,' and I'm just blowing on my little jazz horn and hitting on my guitar. You know, the country sounds different than in the city, the sound out there be empty. You could hear that guitar before you got to the house, and you could hear the peoples hollering.''

This was what was going on in the summer of 1941, when the pioneering folklorist Alan Lomax showed up at Stovall's plantation with his bulky portable recording rig. He was looking for folk music for the Library of Congress and he inquired after Robert Johnson, but Robert had been murdered a few years before and everyone recommended Muddy. ''He brought his stuff down and recorded me right in my house,'' Muddy remembered, ''and when he played back the first song I sounded just like anybody's records. Man, you don't know how I felt that Saturday afternoon when I heard that voice and it was my own voice. Later on he sent me two copies of the pressing and a check for twenty bucks, and I carried that record up to the corner and put it on the jukebox. Just played it and played it and said. 'I can do it, I can do it.'''

Lomax returned to Stovall in July 1942 and recorded Muddy again, as a soloist and with the blues fiddler Son Sims and his string band. These and the 1941 recordings are available on the album Down on Storvall's Plantation, on the Testament label, and they are phenomenal. Muddy played his steel-bodied guitar with razor-sharp accuracy, setting up hypnotic repeating patterns in the bass and filling in sharp slide figures in the treble, singing with gripping immediacy. He would rework a number of the songs he recorded for Lomax – most of which were based more or less directly on traditional pieces in the first place – into the staples of his repertoire after he got to Chicago. And once Muddy recorded for Lomax he was Chicago-bound, whether he knew it or not.

He had already been infected by a certain restlessness. ''I left my first little wife, who's dead now, God bless her, for another woman,'' he recalled, looking a little wistful for the first and only time in the conversation. ''I don't know what the hell was wrong with me; I was kind of a wild cat, man. I'd stay with her awhile and then come back and go away, and then I took this other woman from the little town next to my little town and we went and caught a train for St. Louis. But I wasn't used to the big city and didn't like it, so we went back, and I told my wife, 'Hey, I done get married, you can move out.' What a mess will country peoples do! Later I brought this woman to Chicago with me and we couldn't get along no kind of way, I had to get rid of her. Well, I was crazy, that's all.''

Muddy was bound to tangle with white authority sooner or later, and in May 1943 he had words with the overseer who ran the plantation while Mr. Stovall was away in the army. ''I asked him would he raise me to twenty-five cents an hour for driving the tractor, which is what the other people were getting, and he had a fit. When he got through stomping around, my mind just said, 'Go to Chicago.' I went to my grandmother and she said, 'Well, if you think you're going to have some problem' – you know how it was down there – 'you better go.' That was on Monday. I worked till that Thursday at five o'clock, and on Friday I came in sick and went on to Clarksdale to catch that four-o'clock train.''

What Muddy saw when he stepped off the train, still a little woozy from the all-day, all-night journey, was completely alien to the world he had known. ''I wish you could've seen me. I got off the train and it looked like this was the fastest place in the world: cabs dropping fares, horns blowing, the peoples walking so fast.''

Muddy slept on a couch in the living room of his sister's and her husbands apartment his first week in Chicago. But it was wartime. Industry was booming and manpower was scarce. Muddy got a draft call almost as soon as he arrived in the city – he'd been protected on the plantation because his job was considered vital to agriculture – but once the army learned he had quit school after the second or third grade and couldn't really read or write, they turned him down, to his great delight. He worked several factory and truck-driving jobs, took a four-room apartment, and eventually landed a job delivering Venetian blinds. He made his run in the morning, slept in the afternoon, and played at rent parties and in small taverns at night.

His music began to change. He was concentrating more on his singing and less on his guitar, and working with some other musicians from the Delta, among them pianist Eddie Boyd and guitarists Blue Smitty and Baby Face Leroy. In 1945 his grandmother died, and it was in the spring of 1946, after he returned from burying her, that he met Jimmy Rogers, then mostly a harmonica player. They formed a little group with Rogers on harp and Muddy and Smitty on guitars, and began playing around at house parties and small taverns.

''Muddy was a little older,'' Jimmy says, ''and he was the most like ol' Robert Johnson's style with the slide guitar. I understood the slide style quite well – I learned guitar in the Delta – so I could back him up good. Pretty soon Smitty and I just put Muddy as the leader, because he would do most of the rough blues singing.''

The black neighborhoods were lawless and overcrowded. New arrivals, most of them from Mississippi and neighboring states, were pushing in every day and the whites were fighting to keep them contained on the rapidly deteriorating South and West Sides. The blues scene was transitional. Big Bill Broonzy, Tampa Red and some other Southern bluesmen who had been popular before the war were still the kingpins, largely because of their recording connections. But Muddy and his friends were part of a new wave of musicians who played a harder, more down-home brand of blues, the kind that was being heard in Southern juke joints. In order to cut through crowd noise and compete with the volume of the jukeboxes, these younger bluesmen bought amplifiers, which became mandatory once they began to contend with the decibel level in rowdy city taverns. As the migrants continued to pour in, Muddy's electrified country blues became more and more popular.

Muddy recorded three songs for Columbia in 1946, but they were never issued. In 1947 he was in the studio again, playing guitar for Sunnyland Slim and cutting two numbers of his own for the Aristocrat label, with Slim featured on the piano – ''Gypsy Woman,'' his first recorded blues on a hoodoo theme, and ''Little Anna Mae.'' Leonard and Phil Chess, two Polish immigrants who had started Aristocrat that year to record music aimed at the patrons of their South Side nightclub, didn't know what to make of Muddy's raw sound and shelved the records. But early in 1948 Leonard Chess, who handled the producing end of the business, called Muddy back to cut two more sides, which turned out to be reworkings of two of the traditional blues he'd recorded for Lomax. They were ''I Can't Be Satisfied'' and ''I Feel like Going Home.'' Singing at peak power and playing magnificent electric slide guitar, backed only by Big Crawford's string bass, Muddy was just too impressive to ignore.

Leonard Chess knew very little about down-home blues, having recorded mostly tenor-saxophone instrumental by the jazz-oriented performers who worked in his club, but he put the record out. To his surprise, it became Aristocrat's biggest seller. From that point on the Chess brothers were sold on Muddy, and of course the record changed Muddy's life. ''The little joint I was playing in doubled its business when the record came out,'' he recalled. ''Bigger joints starred looking for me. It was summer when that record came out, and I would hear it walking along the street, driving along the street. One time coming home about two or three o'clock in the morning I heard it coming from way upstairs somewhere and it scared me, I thought I had died.''

At first Leonard Chess would not record Muddy's band, apparently because he thought he had found a hit-making formula in Muddy's voice and guitar and the string bass. Of course, the records weren't really hits. They sold in an area that corresponded to the spread of the Delta's black population, from Mississippi up through Memphis, St. Louis, Detroit and Chicago, with very little action in the East or the West. But within this area, sales were strong and dependable. Soon Leonard grew confident enough of Muddy's abilities to let him bring in a few more musicians, and in 1950, the year the brothers changed the name of their label from Aristocrat to Chess, Muddy showed up for a session with a young, tough-looking harmonica player from Louisiana, Little Walter Jacobs.

Walter was the first harmonica player to use his amplifier creatively. He produced massive roars, ghostly tremolos and whoops, and punching, saxophonelike solo lines on the instrument and revolutionized the sound of Chicago blues while he was with Muddy's band.

In 1951 Jimmy Rogers joined the recording group on second guitar. With Elgin Evans on drums, this was the band that defined the sound of postwar Chicago blues and sent ripples through the world of popular music that continue to be felt. Muddy was still playing country blues, but with a beat. ''My first drummer was straight down the line ''he said, ''boom boom boom boom. I had to get me somebody who would put a backbeat to it.'' Added Willie Dixon, ''You know, when you go to changing beats in music, you change the entire style. Blues or rock & roll or jazz, it's the beat that actually changes it. And that's what Muddy did. He gave his blues a little more pep.''

The band turned out great records in profusion: ''Long Distance Call,'' ''Honey Bee,'' ''She Moves Me'' and the searing ''Still a Fool'' in 1951; ''Standing Around Crying'' (with an initial appearance by the incomparable pianist Otis Spann) in 1952; and the seminal ''Hoochie Coochie Man'' in 1953. This last tune, written by Willie Dixon, is the sort of thing most people associate with Muddy – a slow, lumbering stop-time riff, lyrics that combine hoodoo imagery and machismo. It was more flamboyant than Muddy's own hoodoo blues, but it was just the kind of thing his audience wanted to hear.

''Muddy was working in this joint at 14th and Ashland,'' Dixon remembers, ''and I went over there to take him the song. We went in the washroom and sang it over and over till he got it. It didn't take very long. Then he said, 'Man, when I go out there this time, I'm gonna sing it.' He went out and jumped on it, and it sounded so good the people kept on applauding and asking for more and he kept on singing the same thing over and over again.'' There was no need for further market research. The audience was right there and not at all shy about stating its preferences. Dixon wrote more hits for Muddy, most notably ''I'm Ready'' and ''I Just Want to Make Love to You.'' They remain the most macho songs in his repertoire; Muddy would never have composed anything so unsubtle. But they gave him a succession of showstoppers and an image, which were important for a bluesman trying to break out of the grind of local gigs into national prominence.

Muddy's records were never huge hits, not even among the nation's blacks. ''Hoochie Coochie Man'' made it to Number Eight on the R&B charts and ''Just Make Love to Me'' was Number Four in 1954. The band would drive from gig to gig in Muddy's Cadillac, working mostly in joints on the South and West Sides of Chicago and in the South, with occasional forays to the East. Even though he had fewer hits once rock & roll came along. Muddy was in the game for keeps. ''Rock & roll,'' he said, ''it hurt the blues pretty bad. People wanted to 'bug all the time and we couldn't play slow blues anymore. But we still hustled around and kept going. We survived, and then I went to Newport in 1960 and it started opening the door for me.''

His first crack at a white audience came in 1958, when the English promoter Chris Barber brought Waters' band to England on Big Bill Broonzy's recommendation. At first the tour seemed to be a disaster. ''Oh man,'' said Muddy, ''the headlines in all the papers was SCREAMING GUITAR AND HOWLING PIANO. Chris Barber said, 'You sound good, but don't play your amplifier so loud.' Then I came back to England in the early Sixties and everybody want to know why I didn't bring my amplifier. Those boys were playing louder than we ever played.''

''Those boys'' were the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds with young Eric Clapton, and other white blues groups that had sprung up in England, following the lead of older performers like Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies, been among the few enthralled by Muddy's volume and raw power in 1958. The Stones and their contemporaries were still kids in 1960 when Muddy scored a direct hit with the folk audience at Newport, but they eagerly bought his Newport album, which included the classic extended version of ''Got My Mojo Working.'' In fact, those blue-and-white labeled Chess records from America were as important to them as eating and sleeping. They listened hard to Chuck Berry, whose first recording date was set up by Muddy, and to Bo Diddley, who also came out of the South Side. But Muddy's records had a special, mysterious luminosity. They were so distinctive, so ''deep,'' that they couldn't really be copied, not like Chuck and Bo, though the Stones tried with a brooding rendition of ''Can't Be Satisfied'' that Muddy terms ''a very good job.'' (In mid-July 1978, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Ron Wood and Charlie Watts surprised Muddy by showing up to jam with him at Chicago's the Quiet Knight. Mick and Muddy had a high time trading vocal licks on ''Mannish Boy,'' and Keith played some stinging slide guitar.)

In the States too the music was reaching young whites, who were coming in, literally in many cases, through the back door. Johnny Winter, who grew up in Beaumont, Texas, remembers that ''Muddy was one of the first people I fell in love with. I guess I was about eleven. My grandparents were fairly well off and they had a maid and a guy that'd been working for them for years, and they'd have the black radio station on. I just couldn't believe that music; as soon as I heard it I was obsessed with finding out what it was and hearing more of it. Pretty soon all the record shops in town were saving me a copy of every blues record that came in.'' The process had been going on since the early Fifties, when record-store proprietors began to notice whites showing up and buying race records ''for my maid'' or ''for my yardman'' – records they'd heard their maids and yardmen bopping to and wanted to bop to themselves. By the early Sixties young white musicians were emulating the music on those backdoor records, Johnny Winter among them.

For Muddy, though, the Sixties were an unsettled and unsettling period. It was true that young whites were beginning to appreciate his blues – outside of Chicago, they made up the major part of his audience. But he was much more concerned with the blacks who were turning their backs on the blues. ''When the Rollin' Stones came through the States,'' he said, ''they came to record at the Chess studios. When that happened, I thinks to myself how these white kids was sitting down and thinking and playing the blues that my black kids was bypassing. That was a hell of a thing, man, to think about. I still think about it today. Some of these white kids are playing good blues, but my people, they want something they can bump off of. I play in places now don't have no black faces in there but our black faces.''

Muddy's recording scene was unsettled, too. His brand of blues was no longer selling, and although he continued to put together strong hands with the help of Otis Spann, his pianist, bandleader and right-hand man from the mid-Fifties until his death in the late Sixties, Muddy never again found sidemen as creative, sympathetic and cohesive as Little Walter and Jimmy Rogers. (Walter left him in 1952 when ''Juke'' became a hit, and Rogers split in 1955 to put together his own band.) Leonard Chess' son Marshall and other young executives at Chess began trying to package Muddy, starting with albums like Muddy Waters Folk Singer, which was a reasonable acoustic album, and Brass and the Blues, culminating in the dreadful Electric Mud and After the Rain, which pleased nobody. Then Chess was sold and resold. For two decades Muddy had enjoved a family-style relationship with the Chess company. Now he belonged to a succession of faceless conglomerates.

The picture began to brighten during the early Seventies. He took on Scott Cameron, a shrewd, hardheaded manager who helped him in a number of ways. They sued Arc Music, the Chess publishing company, for back royalties on scores of his compositions, and although nobody will discuss the terms of the eventual out-of-eourt settlement, apparently Muddy was at least partially satisfied. And finally he pulled free of his Chess entanglements altogether and signed in 1976 with Blue Sky Records, the Columbia-affiliated label managed by Steve Paul. With Johnny Winter as producer he made two splendid albums, Hard Again and I'm Ready. Winter wisely avoided trying to duplicate the Chess sound, but he did put Muddy back in a raw-edged, pure blues context, with sympathetic backing from former sidemen like jimmy Rogers, Big Walter Horton and James Cotton. Winter mimicked Muddy's guitar style so accurately, especially on Hard Again, that it was virtually impossible to tell which one was playing.

The records sold 50-60,000 copies each and are still moving briskly, making them the best sellers of Muddys career. He began getting better jobs for better money, especially after an all-star tour with Cotton and Winter that furnished material for a third, soon-to- be-released Blue Sky album. And he was as impressive as ever on that tour. He would start each performance sitting on his stool, letting his voice carry the music, but then he would pick up his guitar and play a wrenching slide solo, the band would begin to fly. and soon he would be up working the lip of the stage, weaving and bobbing to the music and roaring out his lyrics as if they mattered more than anything else in the world.

''This is the best point of my life I'm living right now,'' Muddy said with great finality near the end of our last conversation. I wondered how he felt about having taken so long to get to this point and he looked at me like I was a plain fool, his eyes shining with the irony that informs some of his greatest records. "Feels good,'' he said, "are you kidding? I'm glad it came before I died, I can tell you. Feels great.''

This story is from the October 5th, 1978 issue of Rolling Stone.

From The Archives Issue 275: October 5, 1978

MUDDY WATERS

Artist Biography by Mark Deming

Muddy Waters was the single most important artist to emerge in post-war American blues. A peerless singer, a gifted songwriter, an able guitarist, and leader of one of the strongest bands in the genre (which became a proving ground for a number of musicians who would become legends in their own right), Waters absorbed the influences of rural blues from the Deep South and moved them uptown, injecting his music with a fierce, electric energy and helping pioneer the Chicago Blues style that would come to dominate the music through the 1950s, ‘60s, and '70s. The depth of Waters' influence on rock as well as blues is almost incalculable, and remarkably, he made some of his strongest and most vital recordings in the last five years of his life.

Waters was born McKinley Morganfield, and historians argue about some details of his early life; while he often told reporters he was born in Rolling Fork, Mississippi on April 4, 1915, researchers have uncovered census records and personal documents that would pin the year of his birth at 1913 or 1914, and others have cited the place of his birth as Jug's Corner, a town in Mississippi's Issaquena County. What is certain is that Morganfield's mother died when he just three years old, and from then on he was raised on the Stovall Plantation in Clarksdale, Mississippi by his grandmother, Della Grant. Grant is said to have given young Morganfield the nickname "Muddy" because he liked to play in the mud as a boy, and the name stuck, with "Water" and "Waters" being tacked on a few years later. The rural South was a hotbed for the blues in the '20s and ‘30s, and young Muddy became entranced with the music when he discovered a neighbor had a phonograph and records by the likes of Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, and Tampa Red.

As Muddy became more deeply immersed in the blues, he took up the harmonica; he was performing locally at parties and fish fries by the age of 13, sometimes with guitarist Scott Bohanner, who lived and worked in Stovall. In his early teens, Muddy was introduced to the sound of contemporary Delta blues artists, such as Son House, Robert Johnson, and Charley Patton; their music inspired Waters to switch instruments, and he bought a guitar when he was 17, learning to play in the bottleneck style. Within a few years, he was performing on his own and with a local string band, the Son Simms Four; he also opened a juke joint on the Stovall grounds, where fellow sharecroppers could listen to music, enjoy a drink or a snack, and gamble. Waters became a fixture in Mississippi, performing with the likes of Big Joe Williams and Robert Nighthawk, and in the late summer of 1941, musical archivists Alan Lomax and John Work III arrived in Mississippi with a portable recording rig, eager to document local blues talent for the Library of Congress (it's said they were hoping to locate Robert Johnson, only to learn he had died three years earlier). Lomax and Work were strongly impressed with Waters, and recorded several sides of him performing in his juke joint; two of the songs were released as a 78, and when Waters received two copies of the single and $20 from Lomax, it encouraged him to seriously consider a professional career. In July 1943, Lomax returned to record more material with Waters; these early sessions with Lomax were collected on the album Down On Stovall's Plantation in 1966, and a 1994 reissue of the material, The Complete Plantation Recordings, won a Grammy award.

In 1943, Waters decided to pull up stakes and relocate to Chicago, Illinois in hopes of making a living off his music. (He moved to St. Louis for a spell in 1940, but didn't care for it.) Waters drove a truck and worked at a paper plant by day, and at night struggled to make a name for himself, playing house parties and any bar that would have him. Big Bill Broonzy reached out to Waters and helped him land better gigs; Muddy had recently switched to electric guitar to be better heard in noisy clubs, which added a new power to his cutting slide work. By 1946, Waters had come to the attention of Okeh Records, who took him into the studio to record but chose not to release the results. A session that same year for 20th Century Records resulted in just one tune being issued as the B-side of a James "Sweet Lucy" Carter release, but Waters fared better with Aristocrat Records, a Chicago-based label founded by brothers Leonard and Phil Chess. The Chess Brothers began recording Waters in 1947, and while a few early sides with Sunnyland Slim failed to make an impression, his second single for Aristocrat as a headliner, "I Can't Be Satisfied" b/w "(I Feel Like) Goin' Home," became a significant hit and launched Waters as a star on the Chicago blues scene.

Initially, the Chess Brothers recorded Waters with trusted local musicians (including Earnest "Big" Crawford and Alex Atkins), but for his live work, Waters had recruited a band which included Little Walter on harmonica, Jimmy Rogers on guitar, and Baby Face Leroy Foster on drums (later replaced by Elgin Evans), and in person, Waters and his group earned their reputation as the most powerful blues band in town, with Waters' passionate vocals and guitar matched by the force of his combo. By the early '50s, the Chess Brothers (who had changed the name of their label from Aristocrat to Chess Records in 1950) began using Waters' stage band in the studio, and Little Walter in particular became a favorite with blues fans and a superb foil for Waters. Otis Spann joined Waters' group on piano in 1953, and he would become the anchor for the band well into the '60s, after Little Walter and Jimmy Rogers had left to pursue solo careers. In the '50s, Waters released some of the most powerful and influential music in the history of electric blues, scoring hits with numbers like "Rollin' and Tumblin,'" "I'm Ready," "I'm Your Hoochie Coochie Man," "Mannish Boy," "Trouble No More," "Got My Mojo Working," and "I Just Want to Make Love to You" which made him a frequent presence on the R&B charts.

By the end of the '50s, while Waters was still making fine music, his career was going into a slump. The rise of rock & roll had taken the spotlight away from more traditional blues acts in favor of younger and rowdier acts (ironically, Waters had headlined some of Alan Freed's early "Moondog" package shows), and Waters' first tour of England in 1958 was poorly received by many U.K. blues fans, who were expecting an acoustic set and were startled by the ferocity of Waters' electric guitar. Waters began playing more acoustic music informed by his Mississippi Delta heritage in the years that followed, even issuing an album titled Muddy Waters: Folk Singer in 1964. However, the jolly irony was that British blues fans would soon rekindle interest in Waters and electric Chicago blues; as the rise of the British Invasion made the world aware of the U.K. rock scene, the nascent British blues scene soon followed, and a number of Waters' U.K. acolytes became international stars, such as Eric Clapton, John Mayall, Alexis Korner, and a modestly successful London act who named themselves after Muddy's 1950 hit "Rollin' Stone." While Waters was still leading a fine band that delivered live (and included the likes of Pinetop Perkins on piano and James Cotton on harmonica), Chess Records was moving more toward the rock, soul, and R&B marketplace, and seemed eager to market him to white rock fans, a notion that reached its nadir in 1968 with Electric Mud, in which Waters was paired up with a psychedelic rock band (featuring guitarists Pete Cosey and Phil Upchurch) for rambling and aimless jams on Waters' blues classics. 1969's Fathers and Sons was a more inspired variation on this theme, with Waters playing alongside reverential white blues rockers such as Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield; 1971's The London Muddy Waters Sessions was less impressive, featuring fine guitar work from Rory Gallagher but uninspired contributions from Steve Winwood, Rick Grech, and Georgie Fame.

Curiously, while Chess Records helped Waters make some of the finest blues records of the '50s and ‘60s, it was the label's demise that led to his creative rebirth. In 1969, the Chess Brothers sold the label to General Recorded Tape, and the label went through a long, slow commercial decline, finally folding in 1975. (Waters would become one of several Chess artists who sued the label for unpaid royalties in its later years.) Johnny Winter, a longtime Waters fan, heard the blues legend was without a record deal, and was instrumental in getting Waters signed to Blue Sky Records, a CBS-distributed label that had become his recording home. Winter produced the sessions for Waters' first Blue Sky release, and sat in with a band comprised of members of Waters' road band (including Bob Margolin and Willie "Big Eyes" Smith) along with James Cotton on harp and Pinetop Perkins on piano. 1977's Hard Again was a triumph, sounding as raw and forceful as Waters' classic Chess sides, with a couple extra decades of experience informing his performances, and it was rightly hailed as one of the finest albums Waters ever made while sparking new interest in his music. (It also earned him a Grammy award for Best Traditional or Ethnic Folk Recording.) Waters also dazzled music fans when he appeared at the Band's celebrated farewell concert on Thanksgiving 1976 at the invitation of Levon Helm, who had helped produce one of his last Chess releases, The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album. Muddy delivered a stunning performance of "Mannish Boy" that became one of the highlights of Martin Scorsese's 1978 concert film The Last Waltz. Between Hard Again and The Last Waltz, Waters enjoyed a major career boost, and he found himself touring again for large and enthusiastic crowds, sharing stages with the likes of Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones, and cutting two more well-received albums with Winter as producer, 1978's I'm Ready and 1981's King Bee, as well as a solid 1979 concert set, Muddy "Mississippi" Waters Live. Waters' health began to fail him in 1982, and his final live appearance came in the fall of that year, when he sang a few songs at an Eric Clapton show in Florida. Waters died quietly of heart failure at his home in Westmont, Illinois on April 30, 1983. Since then, both Chicago and Westmont have named streets in Muddy's honor, he's appeared on a postage stamp, a marker commemorates the site of his childhood home in Clarksdale, and he appeared as a character in the 2008 film Cadillac Records, played by Jeffrey Wright.

https://rockhall.com/inductees/muddy-waters/bio/

MUDDY WATERS BIOGRAPHY

Muddy Waters

(vocals, guitar; born April 4, 1913, died April 30, 1983)

Muddy Waters transformed the soul of the rural South into the sound of the city, electrifying the blues at a pivotal point in the early postwar period. His recorded legacy, particularly the wealth of sides he cut in the Fifties, is one of the great musical treasures of this century. Aside from Robert Johnson, no single figure is more important in the history and development of the blues than Waters. The real question as regards his lasting impact on popular music isn’t “Who did he influence?” but - as Goldmine magazine asked in 2001 - “Who didn’t he influence?”

Above all others, it was Waters who linked the country blues of his native Mississippi Delta with the urban blues that were born in Chicago. Waters bought his first electric guitar in 1944 and revolutionized the blues with the recordings he began making in 1948. His amplified combo consisted of himself on slide guitar and vocals, a second guitarist, bass, drums, piano and harmonica. The Muddy Waters Blues Band bore all the earmarks - in terms of size, volume and attitude - of the great rock and roll bands that would follow in its wake.

He was born McKinley Morganfield in Rolling Fork, Mississippi, in 1915. At the age of three he was sent to live with his grandmother, on the Stovall Plantation north of Clarksdale, after his mother died. There he acquired the nickname “Muddy” for his penchant for playing in nearby creeks and puddles. Waters began playing harmonica at the age of seven and took up guitar at seventeen. He picked cotton on the plantation for fifty cents a day and played music as part of a trio at fish fries and house parties on weekends. Folklorist Alan Lomax, while making field recordings for the Library of Congress, tracked down and recorded Waters in 1941 on the Stovall Plantation, near Clarksdale, Miss. Several of these performances were released on Library of Congress anthologies and stand as his first recordings. In May 1943, Waters made the move from the rural plantation to the big city, heading north to Chicago by train.

Waters’ approach to the blues underwent a dramatic metamorphosis after moving to Chicago, where he befriended and played with such estimable figures as Big Bill Broonzy and John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson. Waters switched from acoustic to electric guitar in order to be heard over the din of patrons at the clubs he played on Chicago’s South Side. After a few false starts, Waters’ recording career began in earnest soon after pianist Sunnyland Slim introduced him to Leonard Chess, co-owner of the Aristocrat label (later Chess Records). Working at the famed Chess Studios on South Michigan Avenue, Waters cut many of the greatest recordings in the blues canon. He developed a fruitful team approach to record-making with producer Leonard Chess, bassist/songwriter Willie Dixon, and various musical associates.

In a relaxed, informal studio setting Waters and band laid down a string of citified, plugged-in electric blues that bore the rustic stamp of their Mississippi Delta underpinnings. A flood of blues-standards-to-be from Waters commenced with the 1948 release of “I Can’t Be Satisfied,” a raw, uncut Delta blues. Other classic sides included songs written for Waters by Willie Dixon ("I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man,” “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” “I’m Ready") and by Waters himself (“Mannish Boy,” “Rollin’ and Tumblin’").

Waters was a fierce singer and slashing slide guitarist whose uncut blues bore the stamp of his mentors, Robert Johnson and Son House. For his own part, Waters served to mentor or at least launch many prominent blues musicians, many of whom went on to careers as bandleaders in their own right. The list of notable musicians who passed through Waters’ band includes harmonica players “Little Walter” Jacobs, “Big Walter” Horton, Junior Wells and James Cotton; guitarists Jimmy Rogers, Pat Hare, Luther Tucker and Earl Hooker; pianists Memphis Slim, Otis Spann and Pinetop Perkins; and drummers Elgin Evans, Fred Below and Francis Clay.

Waters’ greatest studio recordings were released as singles during the Fifties, and his first album - a collection of singles entitled The Best of Muddy Waters - didn’t appear until 1958. The Sixties found Waters performing to an ever-widening and appreciative audience as the younger generation acquired an insight into rock and roll’s essential grounding in the blues. In 1960, Waters performed a fiery, unforgettable set at the Newport Folk Festival, released that same year as Muddy Waters at Newport.

Waters also capitalized on the folk-music craze of the late Fifties and early Sixties with a series of albums that found him assaying acoustic blues on such albums as Muddy Waters Sings Big Bill (a tribute to rural bluesman Big Bill Broonzy, released in 1960), Muddy Waters, Folk Singer (1964) and The Real Folk Blues (1966). Less successful were attempts to contemporize his sound with such ill-advised efforts as “Muddy Waters Twist” (a 1962 single) and Electric Mud (an album of psychedelic blues from 1968). More satisfying by far were a couple of albums - Fathers and Sons (1969) and The London Muddy Waters Sessions (1972) - that found Waters accompanied by such vanguard rock musicians as Mike Bloomfield and Eric Clapton. His thirty-year tenure with Chess Records ended in 1975 with the release of The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album. From here, he moved to the Blue Sky label (a Columbia subsidiary).

Waters’ audience grew exponentially following his electrifying performance in The Last Waltz, a film documentary (produced by Martin Scorsese) of The Band’s farewell concert. Staged at San Francisco’s Winterland ballroom, the Thanksgiving 1976 event was a star-studded affair. Water’s scalding rendition of “Mannish Boy” - on which he was accompanied by The Band and Paul Butterfield on harmonica - was an unforgettable highlight. Subsequent to that, he kept the momentum going with a series of uncompromising albums for Blue Sky that were produced by longtime fan Johnny Winter. These included Hard Again (1977), I’m Ready (1978), Muddy Mississippi Waters Live (1979) and King Bee (1981). All were critical and popular successes.

In addition to his musical legacy, Waters helped cultivate a great respect for the blues as one of its most commanding and articulate figureheads. Drummer Levon Helm of The Band, who worked with him on The Muddy Waters Woodstock Album and at The Last Waltz, had this to say about him in a Goldmine magazine interview: “Muddy taught us to take things in context, to be respectful, and to be serious about our music, as he was. He showed us music is a sacred thing.”

Waters, who remained active till the end, died of a heart attack in 1983. He was 68 years old. In the years since his death, the one-room cedar shack in which he lived on the Stovall Plantation has been preserved as a memorial to Waters’ humble origins

See more at: https://rockhall.com/inductees/muddy-waters/bio/#sthash.Wa95U08w.dpuf

http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/muddy-waters-the-delta-son-never-sets-19781005

RS 275

The original 'Rollin' Stone' on a life with the blues

by Robert Palmer

October 5, 1978

Rolling Stone

Muddy Waters, the master bluesman, is now sixty-three. He lives out in the suburbs, almost an hour's drive from downtown Chicago and the decaying South Side where he lived for the past three decades. His white, two-story frame house sits on a quiet corner, shaded by pine trees, with nothing to let a visitor know who owns it except the small, circumspect initials MW on the front door. Inside, it's comfortable: deep carpeting in the living room, modern furniture, a big, all-electric kitchen with grandchildren and neighbors' kids constantly running through it. A few dogs, brought from the South Side where they were protectors, sleep lazily by the toolshed. It's not a pop star's house by any stretch of the imagination, but it's the kind of house very, very few of Chicago's approximately 1.5 million black people will ever own.

Muddy, who is beginning to show his age but remains a wholly commanding presence with his high cheekbones, half-lidded Oriental eyes and undiminished aura of mannish self-confidence – ''I'm a full-growed man,'' he sings, ''a natural-born lover man,'' and you believe him – takes a visitor through the house matter-of-factly, with just a hint of pride. In the small anteroom to the den he points out framed portraits of former sidemen Little Walter and James Cotton, and in the little garden patches around the house and by the concrete driveway, he indicates his cabbage, his greens, his red and green chili peppers and his okra. He doesn't brag about his successes, one suspects, because he knows he deserves them. But he certainly couldn't have imagined it all when he first got off the Illinois Central train in Chicago, back in May 1943. Except for a brief and not very satisfactory sortie to St. Louis and a few quick visits to Memphis, he had not traveled beyond the countryside and small towns of the Mississippi Delta, and he was twenty-eight years old.

The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time: Muddy Waters

Sunnyland Slim, the pianist and singer who got Muddy his first record date with Leonard and Phil Chess in 1947, is working in the heart of the South Side, 61st and Calumet under the El stop. To find Slim, you walk into Morgen's Liquors' front door, down the bar in the middle, into the boisterous music room in the rear. Slim is sitting at a battered, red Wurlitzer electric piano, rapping out tone clusters in the treble and walking the basses with all the authority of his sixty-odd years playing blues, while Louis Myers, the leader of the band and once the guitarist in Little Walter's celebrated Aces, sings blues standards.

''I don't like to play in these kind of places no more,'' Slim says during a break, sipping from a glass of booze and pushing his weathered face up close so he can be heard over the buzz of conversation and the B.B. King record on the jukebox. ''I'll be seventy-six soon. I've just been out to California, Europe. . . . I'm just down here helping Louis out.'' He knows the subject of the conversation is supposed to be Muddy, and like Muddy, he is a proud man. ''You want to know what made Muddy popular? Leonard Chess pushed him. At that time, see, they was still playing the blues on the radio, not like it is now. Those first records he had out, a whole bunch of us had been doin' that rockin' style for years. I brought him in to play guitar for me, on that session when I made 'Johnson Machine Gun.' The man asked me, 'Say, what about your boy there, can he sing?' Talking about Muddy, you know. And I said, 'Like a bird.'''

Later, over on the North Side in a white singles bar with pinball machines and pizza, Jimmy Rogers, second guitarist on Muddy's classic blues records of the early Fifties, is setting up for a gig with the brilliant but erratic harmonica virtuoso Walter Horton. ''Muddy,'' says Rogers, ''Muddy has a whole lot of soul. Maybe it's not the words that he says so much as the way that he says 'em. He has a voice that I haven't heard anybody could imitate. They can copy his slide style of guitar, but when the voice comes in, that's different. I know his voice anywhere I hear it.''

Willie Dixon, the blues bassist, songwriter and producer, sums up peer-group opinion in a few characteristically well-chosen words: ''Everybody liked him 'cause he could really howl those blues.''

What was it about Muddy that made him so widely respected and admired, that made his blues, in his own words, ''deeper'' than the blues of his competitors? Leonard Chess did push Muddy, but he was pushing a man with extraordinary musical gifts and an extraordinary feeling for the blues.

Conventional wisdom has it that blues melodies consist of five, six or seven pitches or notes, with the third and seventh and sometimes the fifth notes of the scale being treated a little funny, flattened but not quite as flat as the black keys on the piano; these are the ''blue notes.'' But if you listen carefully to Muddy, or to any other really deep blues singer, you'll find that he systematically sings the third and, especially, the fifth notes of the scale infintesimally flatter or sharper, depending on where in the line the pitches fall and on the feelings he's trying to convey.

Muddy is the living master of these subtleties. He gets them on guitar too – listen to his slide solo on ''Honey Bee,'' on the Chess/All-Platinum Muddy Waters reissue, for example – and he's aware of getting them. ''Yeah, yeah,'' he says when he is accused of playing microtones, or notes that would fall between the cracks on the piano. ''When I plays on the stage with my band, I have to get in there with my guitar and try to bring the sound down to me. But no sooner than I quit playing, it goes back to another, different sound. My blues look so simple, so easy to do, but it's not. They say my blues is the hardest blues in the world to play.''

The 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time: Muddy Waters

Subtle as these inflections are, young guitarists can at least hope to learn to hear and execute them properly. But as Slim and Rogers and Dixon all noted, Muddy's great strength is his singing, something nobody has been able to duplicate. In addition to his mastery of pitch shadings, he also commands some remarkable textural effects. You can see him in Martin Scorsese's film The Last Waltz, screwing up the side of his face, shaking his jowls, constantly readjusting the shape of his mouth in order to get specific vocal sounds. And his timing is a kind of standing joke among musicians who have played with him. ''I'm a delay singer,'' he says. ''I don't sing on the beat. I sing behind it. And people have to delay to play with me. They got to hang around, wait, see what's going to happen next.''

Muddy's sovereign control of these techniques – how many other bluesmen have had comparable mastery of them? Son House? Robert Johnson? Charley Patton? – goes a long way toward explaining the absolute, unquestioned authority he radiates. It's evident that he didn't learn them in school. They could be taught, if the teacher knew them as well as Muddy does and the student were willing to put in as much time and hard work as it takes to become, say, a first-class opera diva. But in the Delta the learning process, while no less rigorous, was more diffuse.