SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER TWO

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER TWO

THELONIOUS MONK

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

ESPERANZA SPALDING

January 31-February 6

MARY LOU WILLIAMS

February 7-13

STEVE COLEMAN

February 14-20

JAMES BROWN

February 21-27

CURTIS MAYFIELD

February 28-March 6

ARETHA FRANKLIN

March 7-13

GEORGE CLINTON

March 14-20

JAMES CARTER

March 21-27

TERENCE BLANCHARD

March 28-April 3

BILLIE HOLIDAY

April 4-10

[In glorious tribute and gratitude to this great legendary artist we celebrate her centennial year]

VIJAY IYER

April 11-17

CHARLES MINGUS

April 18-24

06/18/13

Magnetic

Blue Note Records

Magnetic is Terence Blanchard’s return to the Blue Note

label after an absence of six years. Its release coincides with the June

2013 premiere in St. Louis of Blanchard’s first opera, Champion. Magnetic

is a small-group recording of uncommon richness, complexity and scope.

It sounds like the work of a jazz musician who writes operas.

Blanchard also writes film scores, and is accustomed to having orchestras and voices at his disposal. He has said that he wants to bring such a “diverse and expansive color palette” to his quintet. Magnetic is successful in achieving this ambitious goal. Blanchard has access to special resources: his own bold yet selective use of electronics; high-impact guests (Ravi Coltrane, Ron Carter, Lionel Loueke); and the individual and collective creativity of one of the strongest working bands in jazz (tenor saxophonist Brice Winston, pianist Fabian Almazan, drummer Kendrick Scott, new 21-year-old bassist Joshua Crumbly).

The 10 tracks, all originals by band members, unfold as varied, often-startling narratives. There are continuous episodic transitions, viewpoints shifting within the ensemble, foregrounds becoming backgrounds, unisons becoming counterpoint and counterpoint becoming, organically, solos. Blanchard’s trumpet eruptions on pieces like Almazan’s “Pet Step Sitter’s Theme Song” and Winston’s “Time to Spare” are ferocious yet technically exact, and that is before he turns himself into a trumpet orchestra with electronics. (Blanchard’s swirling “Hallucinations” is an exemplary aesthetic application of digital technology.) Coltrane’s soprano saxophone swoops into Blanchard’s “Don’t Run” like ecstasy unleashed. Winston’s concise statements are so integral to each tune that they feel less like solos than meticulous personal clarifications. Almazan knocks you down with brute force, touches your heart with lyricism and dizzies your brain with intricacy, all in the first minute of his five-minute piano epic, “Comet.”

Halfway through 2013, here is a clear candidate for Record of the Year.

BUY THIS ALBUM from Amazon.com

STREAM THIS CD from Rhapsody.com

Contemporary Cat: Terence Blanchard with Special Guests. by Anthony Mangro. Scarecrow Press, 2003.

Series: Studies in Jazz (Book 42)

Contemporary Cat: Terence Blanchard with Special Guests. by Anthony Mangro. Scarecrow Press, 2003.

Series: Studies in Jazz (Book 42)

A fascinating look into the new generation of jazz legends, Contemporary Cat is a welcome addition to Scarecrow Press's Studies in Jazz Series.

Living legend Terence Blanchard's life and work are thoroughly examined

through interviews with his contemporaries and colleagues, including

jazz greats Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Nicholas Payton, and filmmaker

Spike Lee. Magro cleverly ties jazz to the social upheavals of the

civil rights movement, to black film, and to southern African-American

ideologies. From Blanchard's early influences to his future projects,

never has a more detailed and personal portrait been conceived of the

man and his genius on stage and in the recording studio.

This book will be welcomed by students of music, jazz, and popular culture, and will be a useful addition to African-American studies collections as well.

This book will be welcomed by students of music, jazz, and popular culture, and will be a useful addition to African-American studies collections as well.

http://terenceblanchard.com/about/timeline

About > Timeline

March 13, 1962

- Born in New Orleans, LA.

- Began playing piano by the age of 5, switched to trumpet 3 years later.

1979

- Attends the famed New Orleans Center for Creative Arts (NOCCA) while in high school, studies with teachers Ellis Marsalis and Roger Dickerson.

1980

- Attends Rutgers University in New Jersey, studies with Paul Jeffrey and Bill Fiedler

1982

- Replaces Wynton Marsalis in the seminal group Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers, Performed on trumpet and serves as musical director until 1986.

1984

- First Grammy Award nomination and win for New York Scene with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers.

- Co-led a quintet with Donald Harrison and Released New York Second Line on Concord Music.

1986

- Released Discernment with Donald Harrison on Concord Music

1986

- Released Nascence with Donald Harrison on Concord Music

1987

- Released Crystal Stair with Donald Harrison on Columbia Music

1988

- Released Black Pearl with Donald Harrison on Columbia Records

1990

- Film: Lead Trumpet on Mo’ Better Blues

- Nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance for Mo'Better Blues with the Branford Marsalis Quartet

1991

- Film Composer (first): Jungle Fever, Director Spike Lee

- Released Terence Blanchard on Columbia Records

1992

- Film Composer: Malcolm X, Director Spike Lee

- Released Simply Stated on Columbia Records

1993

- Released The Malcolm X Jazz Suite on Columbia Records

- Film Composer: Sugar Hill, Director Leo Ichaso

1994

- Nominated by Soul Train Music Award for Best Jazz Album- The Malcolm X Suite

- Film Work: Backbeat, Director Ian Softley

- Film Composer: Trial By Jury, Director Heywood Gould

- Film Composer: The Ink Well, Director Mattie Rich

- Film Composer: Crooklyn, Director Spike Lee

- Released In My Solitude: The Billie Holiday Songbook on Columbia Records

1995

- Nominated for Emmy Award for Best Original Score for TV mini-series The Promised Land, Director Edmund Coulthard, Nick Godwin

- Film Composer, Clockers, Director Spike Lee

- Released Romantic Defiance on Columbia Records

1996

- Nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Latin Jazz Album for The Heart Speaks featuring the compositions of Ivan Lins

- Film Composer: Get on The Bus, Director Spike Lee

- Film Composer: Primal Fear, Director Gregory Hoblit

- Film Composer and Special Music: Soul of the Game, Director Kevin Sullivan

- Released The Heart Speaks on Columbia Records

1997

- Film Composer: Eve's Bayou, Director Kassi Lemmons

- Film Composer: 'Til There Was You, Director Scott Winant

- Film Composer: 4 Little Girls, Director Spike Lee

1998

- Film Composer: Gia, Director Michael Cristofer

- Film Composer: The Tempest, Director J. Bender & B Raskins

1999

- Film (Lead Trumpet): Random Hearts, Director Sidney Pollack

- Film Composer: Summer of Sam, Director Spike Lee

- Film Work: Things You Can Tell Just By Looking at Her, Director Rodrigo Garcia

- Released Jazz in Film on Sony Classical

2000

- Released Wandering Moon on Sony Classical

- Nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental for Wandering Moon

- Named Artistic Director of Jazz of the Thelonius Monk Institute of Jazz at the University of Southern California

- Film Composer: Love & Basketball, Director Gina Prince-Bythwood

- Film Composer: Next Friday, Director Steve Carr

- Film Composer: Bamboozled, Director Spike Lee

2001

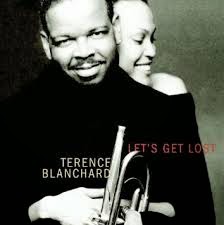

- Released Let’s Get Lost on Sony Classical

- Nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Solo for Let's Get Lost

- Film Composer: The Caveman's Valentine, Director Kasi Lemmons

- Film Composer: Original Sin, Director Michael Cristofer

- Film Composer: Glitter, Director Vondie Curtis-Hall

- Film Composer: A Girl Thing, Director Lee Rose

- Film Composer: Bojangles, Director Joseph Sargent

2002

- Film Composer: Barber Shop, Director Tim Story

- Film Composer: 25th Hour, Director Spike Lee

- Film Composer: People I Know, Director Daniel Algrant

- Film Composer: Dark Blue, Director Ron Shelton

- Film Work: The Salton Sea, Director D.J. Caruso

- Film Work: Jim Brown-All American, Director Spike Lee

- Scarecrow Press publishes an authorized autobiography—Contemporary Cat:Terence Blanchard with Special Guests written by Anthony Magro

2003

- Nominated for Golden Globe Best Original Score – Motion Picture for 25th Hour

- Film Composer: Unchained Memories, Director Ed Bell and Thomas Lennon

- Film Composer: Dark Blue, Director Ron Shelton

- Released Bounce on Blue Note Records

- Winner of Best Score for 25th Hour from the Central Ohio Film Critics Association

- Nominated for Sierra Award for Best Score for 25th Hour

2004

- 2nd Grammy Award win for McCoy Tyner's Illuminations where he was featured as trumpeter and composer of one of the songs.

- Film Composer: She Hate Me, Director Spike Lee

2005

- Released Flow on Blue Note Records

- Nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Album Flow

- Film Composer: Their Eyes Were Watching God, Director Darnell Martin

- Nominated for a Black Reel for Best Original Score for She Hate Me

2006

- Nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video, Flow: Living in the Stream of Music

- Film Composer: Inside Man, Director Spike Lee

- Film Composer: When The Levee’s Broke, Director Spike Lee

- Film Composer: Waist Deep, Director Vondie Curtis-Hall

2007

- Released A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem for Katrina) on Blue Note Records

- 3rd Grammy Award win Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album for A Tale of God's Will

- Nominated for a Grammy for Best Jazz Instrumental Solo for A Tale of God's Will ( A Requiem for Katrina)

- Nominated for Black Reel for Best Original Score for Inside Man

- Film Composer: Talk To Me, Director Kasi Lemmons

- Secured a "Commitment to New Orleans' by the Thelonius Monk Institute to relocate the famed music program to New Orleans at Loyola Univsersity for a four-year term.

- Named Artist-in-Residence for the Monterey Jazz Festival

2008

- 4th Grammy Award win, Best Jazz Instrumental Solo for Live at the 2007 Monterey Jazz Festival

- Film Composer: Miracle At St. Anna’s, Director Spike Lee

- Film Composer: Cadillac Records, Director Darnell Martin

2009

- Released Choices on Concord Music

- 5th Grammy Award Win for Best Jazz Instrumental Solo for Watts for the track "Dancin' 4 Chicken"

- Performs all trumpet parts for "Louis" the alligator in the Disney film The Princess and The Frog

2010

- Film Composer: Bunraku, Director Guy Moshe

2011

- Named Artistic Director of Jazz for Mancini Institute at University of Miami Frost School of Music

- Commissioned by Opera Theatre St. Louis to compose an Opera- Champion about the life of boxer Emille Griffith. Debuts in 2013

- Music Composer for Broadway play Motherf*#@^! With a Hat

- Commissioned by Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra and New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation to compose "Concerto for Roger Dickerson." Performed at the Mahalia Jackson Theater on February 19th.

2012

- Film Composer: Red Tails, Director George Lucas

- Music Composer for Broadway play revival of A Street Car Named Desire

- Appointed Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Jazz Creative Chair for the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Presenting the 2012 -2013 Paradise Jazz Series.

- Presented with an Honorary Degree from Xavier University in New Orleans.

2013

- World-wide premiere of Champion, an Opera in Jazz in collaboration with Opera Theatre St. Louis and Jazz St.Louis.

- Released Magnetic on Blue Note Records.

- Nominated for Soul Train Awards’ Best Traditional Jazz Performance for the song “Pet Step Sitters Theme Song.

http://www.npr.org/2013/06/15/191709047/terence-blanchard-turns-a-tragic-champion-into-an-opera-hero

Terence Blanchard Turns A Tragic Champion Into An Opera Hero

Terence Blanchard is one of today's foremost jazz composers.

Nitin Vadukul/Courtesy of the artist

From his days blowing trumpet for Art Blakey to his film scores for Spike Lee, Terence Blanchard has honed a signature sound as one of today's foremost composers of jazz. Last year brought a new challenge: He was commissioned to compose an opera, and jumped at the chance to tell a powerful tale.

Champion is the true story of a gay boxer in the 1960s, welterweight world champion Emile Griffith, and his fateful fights with rival Benny Paret.

"They fought twice, each winning a decision in the fight," Blanchard says. "And then there was a third fight, and with Benny trying to gain an advantage over Emile, he kind of mocked his sexuality, which Emile was keeping very much under wraps."

Blanchard says that in the final round of that fight, Griffith cornered Paret and hit him 17 times. The blows put Paret into a coma, and 10 days later he died.

"Emile went on to fight again, but was always haunted by that experience, obviously," Blanchard says. "But he said something in his autobiography, which is the thing that made me want to write the opera about him. He said, 'I killed a man and the world forgave me, yet I loved a man and the world has still never forgiven me.' "

Later in life, after he'd retired and begun training other fighters, Griffith suffered another trauma: He was attacked coming out of a gay bar in New York City and landed in the hospital for a month. Blanchard says much of the music in Champion was written to evoke the deep thinking that often follows physical and emotional injury.

"All of these arias are very personal moments; to me, they speak to that moment in everyone's life when you have certain types of quiet reflection," he says. "The arias are written in such a way where they're moments in time that kind of step out from the rest of the opera."

In addition to his work on Champion, Blanchard has a new album out with his jazz combo, entitled Magnetic. He says he's done this kind of multitasking for most of his career, in part because what he learns from one project can strengthen another.

"I go back to my days with Art Blakey, and one of the things that he always used to say is that composing is the way that you find yourself," Blanchard says. "That's the thing that I think about all the time. When you have to sit down and commit musical ideas to paper, they start to become imprinted on your musical identity. So over the years, the experience of doing this has helped shape who I am as a musician."

Featured Artist

Collaborations

Terence Blanchard returns to the Detroit Symphony Orcehstra as Jazz Director Creative Chair!

Legendary jazz trumpeter Terence Blanchard returns next season as the DSO’s Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Jazz Creative Director Chair. He’s programmed an all-star 2014-15 Paradise Jazz Series season beginning with the virtuosic vocalist Dianne Reeves, followed by appearances by the Count Basie Orchestra, former Duke Ellington Orchestra saxophonist Kenny Garrett, Wayne Shorter Quartet, Grammy winners John & Gerald Clayton and Blanchard’s own Quintet paired with the DSO.In the DSO’s first appearance on the Paradise Jazz Series, Blanchard will present his own Grammy-winning composition, A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem for Katrina), written in commemoration of the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s devastating aftermath in Blanchard’s native new Orleans.

The Paradise Jazz Series is sponsored MGM Grand Detroit.

Ticket Information

Subscriptions to the 2014-15 Paradise Jazz Series are on sale now and can be purchased by calling (313) 576-5111 or visiting dso.org. Single tickets will go on sale August 2014.

6-concert series are $90 for Upper Balcony, $150 for Mid-Balcony, $200 for Main Floor B, $260 for Main Floor A, $300 for Dress Circle and $495 for Box Level.

The Paradise Jazz Series

Dianne Reeves Fri., Oct. 17 at 8 p.m.Dianne Reeves is undoubtedly one of the world’s most captivating artists. As a result of her virtuosity, improvisational prowess and unique jazz and R&B stylings, Reeves received the Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Performance for three consecutive recordings—a Grammy first in any vocal category. Adored by audiences and critics alike throughout the world, Dianne Reeves is a natural wonder not to be missed. Reeves will be joined by pianist Peter Martin, bassist Reginald Veal, guitarist Romero Lubambo and drummer Terreon Gully.

Kenny Garrett Fri., Jan. 30 at 8 p.m.

“One of the most admired alto saxophonists in jazz after [Charlie] Parker,” according to The New York Times music critic Ben Ratliff. Detroit native Kenny Garrett has enjoyed a stellar career that has spanned more than 30 years. From his first gig with the Duke Ellington Orchestra (led by Mercer Ellington) through his time spent with musicians such as Freddie Hubbard, Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers and Miles Davis, Garrett has always brought a vigorous yet melodic, and truly distinctive, alto saxophone sound to each musical situation. Now Garrett comes home, along with his quintet, in what’s sure to be an unforgettable evening of music!

Wayne Shorter Quartet Fri., March 20 at 8 p.m.

Legendary jazz saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter is regarded as one of the most significant and prolific performers and composers in jazz and modern music. His music transcends genre while keeping the improvisational genius and surprise of jazz burning at the center. Since coming together in 2001, the Wayne Shorter Quartet has single-handedly put a spotlight on the possibilities of spirited ensemble performance and inspired, collective composition. The Guardian (UK) calls the quartet “the most skillful, mutually attuned and fearless adventurous small group on the planet.” Prepare yourself for spellbinding evening of music from this jazz giant and his all-star band!

John & Gerald Clayton Duo

Fri., April 17 at 8 p.m.

Grammy-winning bassist and composer John Clayton has written and arranged music for Quincy Jones, Diana Krall, Queen Latifah and Regina Carter, just to name a few. “...one of the most accomplished bassists in mainstream jazz,” declares DownBeat Magazine critic Thomas Conrad. Pianist Gerald Clayton’s dynamic and award-winning sound has been praised by JazzTimes and the Los Angeles Times. The New York Times has saluted his “Oscar-Peterson like style” and “huge, authoritative presence”, and he was recently named “Rising Star – Pianist” in the 2013 DownBeat Magazine Critics Poll. The father-son duo will grace the Orchestra Hall stage for a spontaneous night of mesmerizing jazz.

A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem for Katrina) Terence Blanchard Quintet with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra Thurs., June 4 at 8 p.m.

In commemoration of the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Blanchard presents his Grammy-winning A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem For Katrina), featuring his quintet along with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Music Director Leonard Slatkin. Featuring 13 original compositions inspired from and featured in Spike Lee’s HBO Documentary, “When the Levees Broke,” A Tale Of God’s Will is an evocative, emotional journey of a city whose spirit, even though the most devastating of circumstances, lives on...as told by one of New Orleans’ proudest residents.

News

Detroit Symphony Orchestra 2014-15 Season BrochureFive-Time Grammy Winning Trumpeter Terence Blanchard Returns for Additional Season as DSO Jazz Creative Director, Schedules All-Star Lineup of Jazz Masters

2013-2014 PARADISE JAZZ SERIES NOW ON SALE, 03/14/2013

Terence Blanchard Named Jazz Chair For The Detroit Symphony Orchestra, JazzCorner, 3/20/12

Champion, premiered to Sold-Out audiences and garnered great critical acclaim.

"Terence Blanchard's Opera is a new American Masterpiece." --The Denver Post

"Visually a Treat"

--New York Times

"Champion may be the single most important world première in the 38-year history of Opera Theatre of St. Louis."

--St.Louis Post-Dispatch

"A new work of quality and staying power, one that deserves to be taken up by other opera producers far and wide."

--Chicago Tribune

Continuing their individual traditions of commissioning music by the world’s best contemporary composers, Opera Theatre of Saint Louis and Jazz St. Louis joined forces to develop a new opera, that featured a powerhouse team of writers and performers. With music by Terence Blanchard and libretto by Michael Cristofer, Champion blends the uniquely American tradition of jazz with the dramatic power of opera. Based on the story of prizefighter Emile Griffith, the opera starred Denyce Graves, Aubrey Allicock, Arthur Woodley, Robert Orth, and Meredith Arwady. Directed by Opera Theatre of Saint Louis Artistic Director James Robinson, Champion premiered on June 15 – 30, 2013 as part of Opera Theatre’s 2013 Festival Season.

For more information on Opera Theatre St. Louis, visit here.News

A Deadly Night in the Boxing Ring Is Grist for an Evening at the Opera, NY Times 5/16/12OTSL announces a new commission for 2013, Stltoday.com 5/16/12

Grammy Award-winning Composer Terence Blanchard And Pulitzer Prize-winning Playwright Michael Cristofer To Premiere New Opera At Opera Theatre Of St. Louis, All About Jazz 5/16/12

http://jazztimes.com/articles/18876-terence-blanchard-tragic-symphony

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Terence_Blanchard.aspx

Terence Blanchard

Trumpeter, composerTerence Blanchard may be most widely known for his work composing music for director Spike Lee's films, but his deepest love remains with his own jazz trumpeting. When Blanchard rearranged his score for Lee's 1992 film Malcolm X into The Malcolm X Jazz Suite for his own quintet in 1993, Washington Post reviewer Geoffrey Himes called the album "extraordinary, landmark," and esteemed Blanchard as "[Wynton] Marsalis's only real rival as a modern composer of jazz suites in the Ellington mode." In 1994 Down Beat's Michael Bourne deemed In My Solitude: The Billie Holiday Songbook Blanchard's "most heartfelt album." This flurry of success in the early to mid-1990s followed a steady rise from Blanchard's New Orleans roots to his years starting in 1982 with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers in New York and through his playing and recording in the late 1980s with fellow Jazz Messenger Donald Harrison.

In 1989 Blanchard's career was well underway, but he faced a critical crisis. The trumpeter had been mistakenly placing his lips over his teeth instead of in front of them in forming his embouchure, or physical connection to his instrument. This caused a lip injury that led to a one-year hiatus from playing the trumpet. Frustrated in the midst of growing success, Blanchard had to relearn his fundamental technique in proper form after his lips had a chance to heal.

A Father's Influence

Blanchard made it through the ordeal and emerged a leader on the jazz scene. He credited his father with teaching him the patience and wherewithal to overcome deep frustrations in his career, both in retraining himself after the injury and in maintaining his inspiration during some longer tours on the road. Joseph Oliver Blanchard instilled discipline and determination into his son at a young age. The elder Blanchard was an insurance company manager and part-time opera singer in New Orleans who maintained his passion for music despite the racial bias that precluded him from singing full time.

When at age five the young Blanchard began picking up TV show themes such as "Batman" on his grandmother's piano, Blanchard's father brought a piano home and hired a teacher for his son. Then he watched him practice. "He would actually sit there while I practiced," Terence recalled for Wayne K. Self in Down Beat. "He'd sit on the couch and listen until I got it straight. If I made a mistake, he would stop me and say, ‘Go back; go back. Do it again; you've got to get it right.’ I hated it; I hated it with a passion."

If his father introduced him to music and helped him mold aspects of his character, then Blanchard's experience with legendary teachers of jazz developed his love for the trumpet into a striking ability. First Blanchard studied with Ellis Marsalis at the New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts (NOCCA). Ellis Marsalis, father of Branford and Wynton Marsalis, introduced the trumpeter to the sounds of Clifford Brown, Miles Davis, Charlie "Bird" Parker, and John Coltrane, all of whom would become influences on Blanchard's playing. Meanwhile, Blanchard continued his classical studies and played around town, in the New Orleans Civic Orchestra, in Sunday afternoon Dixieland gigs, and subbing for a big band at the Blue Room.

In 1980 Blanchard went to New York and studied classical and jazz trumpet at Rutgers University on a scholarship. The head of the jazz program there, Paul Jeffrey, connected Blanchard with the Lionel Hampton band. Blanchard played on the road with Hampton on weekends for two years, while he was a Rutgers student. Then Wynton Marsalis approached Blanchard and fellow NOCCA grad Donald Harrison about taking his place in Art Blakey's band in New York. "We auditioned in the band at Fat Tuesday's," Blanchard told Michael Bourne of Down Beat. "One night we played a whole set while Wynton and Branford sat in the back. And then Art said, ‘You're a Jazz Messenger now.’"

Coming Into His Own

Blakey immediately urged Blanchard to develop his own style. "I used to come in and try to play like Miles Davis or Clifford Brown," Blanchard told Scott Aiges of the New Orleans Times-Picayune. "I remember I was playing ‘My Funny Valentine’ and he said, ‘Look, you got to stop doing that, man. You got to pick a ballad that you can make your own and work on your own style and your own sound. Miles did that already. He put his stamp on it.’" One year after joining Blakey's band, Blanchard became musical director and had contributed some tunes of his own to the band's repertoire.

After four years with Blakey's band, Blanchard and Harrison set out in 1986 to form their own quintet and recorded five albums, starting with New York Second Line in their first year. Blanchard had also worked on the soundtracks for the Spike Lee films School Daze, Do the Right Thing, and Mo' Better Blues before breaking with Harrison and signing on to Columbia with his own quintet in 1990. Blanchard's first two albums as a leader, Terence Blanchard, with Branford Marsalis and others in 1991, and Simply Stated in 1992, generated basically positive, although not glowing, reviews. Blanchard attributed the tepid recognition to logistical problems with his Columbia contract and to juggling studio schedules while working on Lee's film Jungle Fever.

With his album The Malcolm X Jazz Suite, culled and translated from the best of his soundtrack for Lee's film Malcolm X, Blanchard achieved broad and deep recognition for succeeding in a bold and ambitious project. A New York Times review by jazz writer K. Leander Williams included sympathetic comparisons to the legendary Duke Ellington. Both artists brought heightened force and energy to the extended suite form. This form, beginning in 1943 with Ellington's Black, Brown and Beige Suite, shifted jazz from a kind of popular music to an art music as well. "Like the extended compositions of Ellington's later years," Williams wrote, "Mr. Blanchard's suite has succeeded in creating music that, while illuminated by his players, is indelibly shaped by its composer."

For the Record …

Born on March 13, 1962, in New Orleans, LA; son of Joseph Oliver Blanchard (an insurance company manager and part-time opera singer). Education: Studied under Ellis Marsalis at New Orleans Center for the Creative Arts (NOCCA); studied under jazz trumpeter Paul Jeffrey and classical trumpeter Bill Fielder at Rutgers University, 1980-82.

Trumpet player with New Orleans Civic Orchestra, in Dixieland gigs, and with big bands at the Blue Room in New Orleans, late 1970s; with Lionel Hampton's band, 1980-82; with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, 1982-86, as musical director, 1983-86; with Donald Harrison in a quintet, 1986-90; founder and leader of Terence Blanchard Quintet, beginning 1990; performed concerts at Equitable Center, JVC Jazz Festival, New York, 1991; Orpheum Theater, New Orleans, and Jazz Tent, New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, 1992; with Sonny Rollins, Carnegie Hall, 1993; as leader, Jazz at Lincoln Center, 1993; with Terence Blanchard Quintet, Village Vanguard, New York City, 1993; and at Jazz Showcase, Chicago, 1994; has also played internationally; performed trumpet music for films; composer of soundtracks and music for films, including Clockers: Original Orchestral Score, 1995; issued Wandering Moon, 2000, and Let's Get Lost, 2001; composed soundtrack for 25th Hour and Bounce, 2003; participated on McCoy Tyner's Grammy Award Winning Album Illuminations, 2004; issued Flow, 2005; recorded A Tale of God's Will (A Requiem for Katrina), 2007.

Addresses: Record company—Columbia Records, 51 West 52nd St., New York, NY 10019, Web site: http://www.columbiarecords.com/.

In the 1990s Blanchard remained as busy as ever. He continued to score soundtracks for Spike Lee movies, including 1994's Crooklyn, and contributed to other film soundtracks, such as Sugar Hill, Inkwell, Trial by Jury, Housesitter, and BackBeat. EntertainmentWeekly considered Blanchard central to a general resurgence of jazz composition for film. Meanwhile, Blanchard recorded another bold album, In My Solitude: The Billie Holiday Songbook, for Columbia in 1994. Blanchard's deepest love remained with playing his trumpet, both in recording and especially live. "Writing for film is fun, but nothing can beat being a jazz musician, playing a club, playing a concert," Blanchard was quoted as saying in Down Beat. "When I stood next to Sonny Rollins at Carnegie Hall last fall and listened to him play, that was it for me. … You could've shot me and killed me right there, and I would've been happy."

Blanchard continued to record both solo projects and score movies at the turn of the millennium. In 2000 he issued Wandering Moon, an album that led Michael G. Nastos of All Music Guide to comment, "Trumpeter Blanchard has released some fine recordings in the '90s, but this one may be the best of them all, as he asserts himself as a composer of truly original modern jazz." In 2001 Blanchard completed Let's Get Lost, a tribute to songwriter Jimmy McHugh, a recording that relied on the talents of four female singers, Diana Krall, Jane Monheit, Dianne Reeves, and Cassandra Wilson. Blanchard also continued to work with director Spike Lee, scoring the soundtrack for his 2002 movie 25th Hour.

A Musical Storm

In 2006 the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina assumed special meaning for Blanchard: he had been born in New Orleans, and his mother lost her home in the storm. The tragedy would also lead to one of his most deeply felt musical projects. When his long-time collaborator Lee heard the news, Blanchard recalled in the Santa Barbara Independent, "he got on the next plane from New York and came straight to my place. He knocked on the door and then, before he even said hello, he said that we had to make this film—that we had to let these people tell their stories." As a result, Blanchard recorded A Tale of God's Will (A Requiem for Katrina), a moving tribute to the victims. "The music here will leave you in a melancholy, contemplative mood and definitely in awe of the talented musicians, composers, and arrangers who told A Tale of God's Will," wrote Paula Edelstein in All Music Guide.

Recalling his work on the soundtrack, and the magnitude of the New Orleans tragedy and its aftermath, Blanchard told the Santa Barbara Independent, "I had that aspect of the film in mind, that in the levees you see just everybody. In a strange way, now, I feel blessed, because this thing has gotten the best out of us as artists."

Selected discography

(With Donald Harrison) New York Second Line, Concord Jazz, 1983.

(With Art Blakey) New York Scene, Concord Jazz, 1984.

(With Harrison) Discernment, Concord Jazz, 1986.

(With Harrison) Nascence, Columbia, 1986.

(With Blakey) Live at Kimball's (recorded 1985), Concord Jazz, 1987.

(With Blakey) Blue Night (recorded 1985), Timeless, 1991.

Terence Blanchard, Columbia, 1991.

(With Blakey) Dr. Jekyle (recorded 1985), Evidence, 1992.

Simply Stated, Columbia, 1992.

(With Blakey) Hard Champion (recorded 1985), Evidence, 1992.

(With Blakey) New Year's Eve at Sweet Basil (recorded 1985), Evidence, 1992.

(With Harrison and others) Fire Waltz (recorded 1986), Evidence, 1993.

The Malcolm X Jazz Suite, Columbia, 1993.

(With Harrison and others) Eric Dolphy and Booker Little Remembered Live at Sweet Basil (recorded 1986), Evidence, 1993.

In My Solitude: The Billie Holiday Songbook, Columbia, 1994.

Clockers: Original Orchestral Score, Columbia, 1995.

Wandering Moon, Columbia, 2000.

Let's Get Lost, Sony, 2001.

25th Hour, Hollywood, 2003.

Bounce, Blue Note, 2003.

Flow, Blue Note, 2005.

A Tale of God's Will (A Requiem for Katrina), Angel, 2007.

Film soundtracks

Do the Right Thing, Columbia, 1989.Mo' Better Blues, Columbia, 1990.

Malcolm X, Columbia, 1992.

Inside Man, Varese Sarabande, 2006.

Sources

Periodicals

Billboard, July 13, 1991; June 6, 1992.Down Beat, August 1983; October 1991; August 1992; May 1994.

Entertainment Weekly, May 13, 1994.

Los Angeles Times, August 15, 1993.

New York Times, June 20, 1993.

Time, May 16, 1994.

Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), May 1, 1992.

Washington Post, October 1, 1993.

Online

"An Interview with Terence Blanchard of the Monterey Jazz Festival Orchestra," Santa Barbara Independent,http://independent.com/news/2008/jan/10/interview-terenceblanchard-monterey-jazz-festival/, January 7, 2008."Terence Blanchard," All Music Guide,http://www.allmusic.com, January 7, 2008.

Other

Additional information for this profile was provided by Columbia Records Media Department publicity materials.—Nicholas Patti and Ronald D Lankford, Jr.

http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/terence-blanchard-son-new-orleans

Terence Blanchard, a son of New Orleans

Date:

Tue, 1962-03-13

Terence Oliver Blanchard was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, the only child to parents Wilhelmina and Joseph Oliver Blanchard, a part-time opera singer and insurance company manager. Blanchard began playing piano at the age of five and then the trumpet at age. He played trumpet alongside childhood friend Wynton Marsalis in summer music camps then, while in high school, he began studying at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts (NOCCA) under Roger Dickerson and Ellis Marsalis, Jr.. From 1980 to 1982, Blanchard studied under jazz saxophonist Paul Jeffrey and trumpeter Bill Fielder at Rutgers University, while touring with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra.

In 1982, Wynton Marsalis recommended Blanchard to replace him in Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers and until 1986; Blanchard was the band's trumpeter and musical director. With Blakey and as co-leader of a quintet with saxophonist Donald Harrison and pianist Mulgrew Miller, Blanchard rose to prominence as a key figure in the 1980s Jazz Resurgence. The Harrison/Blanchard group recorded five albums from 1984-1988 until Blanchard left to pursue a solo career in 1990. After a laborious but successful embouchure change, he recorded his self-titled debut for Columbia Records that reached third on the Billboard Jazz Charts. After performing and composing soundtracks for Spike Lee movies, including Do the Right Thing and Mo' Better Blues, "Jungle Fever" Malcolm X, Clockers, Summer of Sam, 25th Hour, and Inside Man. In 2006, he composed the score for Spike Lee's 4-hour Hurricane Katrina documentary for HBO entitled When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts.

Blanchard also appeared in front of the camera with his mother to share their emotional journey back to find her home completely destroyed. With over forty scores to his credit, Blanchard is the most prolific jazz musician to ever compose for movies. Blanchard has remained true to his jazz roots as a trumpeter and bandleader on the performance circuit. He has recorded several award-winning albums for Columbia, Sony Classical and Blue Note Records, including In My Solitude: The Billie Holiday Songbook (1994), Romantic Defiance (1995), The Heart Speaks (1996), Wandering Moon (2000), Let's Get Lost (2001) and Flow (2005), which was produced by pianist Herbie Hancock and received two Grammy Award nominations.

In the fall of 2000, Terence Blanchard was named artistic director of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz at the University of Southern California. Herbie Hancock serves as chairman; Wayne Shorter, Clark Terry and Jimmy Heath sit on the board of trustees. The conservatory offers an intensive, tuition-free, two-year master's program to a limited number of students (only up to eight per every two years). His 2001 CD Let's Get Lost features arrangements of classic songs written by Jimmy McHugh and performed by his own quintet along with the leading ladies of jazz vocals: Diana Krall, Jane Monheit, Dianne Reeves, and Cassandra Wilson. In 2005, Blanchard was part of the ensemble that won a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Album for his participation on McCoy Tyner’s Illuminations. In 2007, the Institute announced its "Commitment to New Orleans" initiative, which included the relocation of the program to the campus of Loyola University New Orleans from Los Angeles.

Blanchard also was a judge for the 5th annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists' careers. In 2009 in the Disney movie, The Princess and the Frog, Blanchard played all of the alligator Louis’ trumpet parts. He also voiced the role of Earl the bandleader in the riverboat band. In December 2002, Scarecrow Press published Contemporary Cat: Terence Blanchard with Special Guests, an authorized biography of Blanchard. The book is the 42nd title in the publisher's "Series In Jazz". He is known as a straight-ahead artist in the hard bop tradition but has recently utilized an African-fusion style of playing that makes him unique from other trumpeters on the performance circuit. Blanchard lives in the Garden District of New Orleans with his wife and four children.

Reference:

All Media Guide

1168 Oak Valley Drive

Ann Arbor, MI 48108 USA

To Become a Musician or Singer

Related videos:

Black Support Of Jazz, Terence Blanchard

Career Advice, Music, Terence Blanchard

Terence Blanchard: Tragic Symphony

JazzTimes

September 2007

By now, trumpeter-composer Terence Blanchard has lost track of

just how many films he’s scored since 1991’s Jungle Fever, the first of

his many collaborations to come with controversial filmmaker Spike Lee.

“I stopped counting,” he says with a laugh, an indication of just how

prolific he’s been in his “second career” as a film score composer. For

the record, he’s done a baker’s dozen with Lee, including scores for

such memorable films as 1992’s Malcolm X, 1995’s Clockers, 1999’s Summer

of Sam, 2000’s Bamboozled, 2002’s The 25th Hour and 2005’s Inside Man.

Apart from his prodigious work with Lee, Blanchard has also delivered

evocative scores for 1997’s Eve’s Bayou, 1998’s HBO movie Gia (starring

Angelina Jolie in a breakthrough role), 2001’s Showtime film Bojangles

(starring the late Gregory Hines in one of his last roles), 2001’s

Glitter (a vehicle for singer Mariah Carey), 2002’s hit film Barbershop

and 2003’s Dark Blue. His latest score is for Kasi Lemmons’ new film

Talk To Me, based on the life of Washington, D.C., disc jockey and

political activist Petey Greene (portrayed by Don Cheadle).

Of all the scores that Blanchard has composed over the past 17 years, easily his most cathartic and emotionally wrenching project to date was composing the music for Lee’s provocative HBO documentary, When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. A chilling account of what Hurricane Katrina wrought on the city of New Orleans that tragic day in August 2005, it is also a stinging indictment of the Bush administration’s utter neglect of Americans who were left to die in the flooded Crescent City. New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin, Louisiana governor Kathleen Babineaux Blanco and the Army Corps of Engineers are also taken to task in Lee’s remarkable four-hour documentary, which is underscored by Blanchard’s poignant and melancholy motifs.

But more than just fingerpointing, When the Levees Broke is a powerful narrative woven together by impassioned testimony from those who survived to tell the tale of devastation and abandonment. And Blanchard’s elegant, moving score reflects their grief and frustration while also channeling their hope and optimism in the face of overwhelming odds.

Considering that he was a subject of the Levees documentary as well as the composer of its haunting score, Blanchard had far more invested emotionally in this project than any other he’d done before with Lee. “It was very difficult because it was the first time that I couldn’t take a break from a project,” says Blanchard. “You know, you work on projects that are very dear to you and very heartfelt, and when you hit a wall you can take a break, step outside, go to lunch, hang out with the family, do whatever. But I couldn’t do that on Levees. Because taking a break meant I had to go and check on what was going on with my mom’s house, what was going on with my mom. And that meant driving through a city that had no street lights or stop signs anywhere, where there was total devastation on 80 percent of the properties. So it was a difficult time. And the craziest thing about it is whenever I speak about that I always have to end it by saying, ‘You know, with all of that, we still feel like we were the lucky ones.’”

One of many thousands of displaced New Orleanians (who were later callously referred to by the media as “refugees”), Blanchard delivers scathing testimony in the film. In one candid scene he declares, “It pisses you off because it didn’t have to happen.” Indeed, the breaking of the levees has been called “the most tragic failure of a civil-engineered system in the history of the United States.”

In one telling scene, the trumpeter is filmed walking through the city’s Lower Ninth Ward, playing “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” while Lee’s camera scans the endless devastation, capturing the utter despair of a neighborhood that was home to Fats Domino and other proud residents. As one outraged resident of the Lower Ninth Ward states in the film, “This is what’s left. Your whole history under a pile of rubble. This is a good neighborhood that’s gone, man.”

In one of the most heart-wrenching scenes of the film, Blanchard comforts his mother, who breaks down in tears upon encountering the complete destruction of her home along with a lifetime of memories. “It was hard for all of us,” he says of filming that very touching moment. “I remember asking her, ‘You sure you want to do this? Because … that’s gonna be like having all these people following you around during this very private moment.’ And her thing was, ‘Well, people need to see what we’re going through in New Orleans.’ So when you watch the film, don’t just look at her. Take her experience and multiply that by a hundred thousand because there’s so many people who have had the exact same experience or worse.”

Watching these and other scenes of human tragedy that permeate all four acts of Levees, it is nearly impossible to suppress feelings of anger at the sheer incompetence that led to devastation on such staggering scale. If Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 hadn’t already made the point, Lee’s When the Levees Broke drives it home: Bush and his cronies at FEMA and Homeland Security are asleep at the wheel. There’s no other explanation for the bureaucratic bungling and foot-dragging that resulted in five days of inaction while stranded people waved SOS banners from rooftops and bloated carcasses floated facedown in the toxic waters that flooded Crescent City streets.

It would seem the only reasonable response to those disheartening scenes is one of pure rage. If someone else had been scoring this documentary, it might’ve been roaring with dissonance, throbbing with polyrhythms and power chords and skronking with cathartic feedback squalls—all tossed in as an iron fist upside the head of the Bush administration and all the incompetents at FEMA, Homeland Security and the Army Corps of Engineers. But Blanchard chose another path in scoring Levees.

“Anger is an obvious direction to go in and that’s a very valid emotion to have,” he says. “But with this music, I was really trying to stay out of the way of all of those amazing stories which, to me, was the most important thing about the Levees documentary. So I didn’t want the music to be very complicated or cloud people’s judgment. I wanted the music to put people in a very reflective kind of mood so they could sit back and just experience these stories that are being told. These were truly sympathetic characters in the cinematic sense of the word. And the music, to me, had to play a vital role in not pushing that too far but just allowing that to exist. And again, it’s hard for me to take credit for that because, for me, I’m just reacting to what I’m watching on the screen.”

As it turned out, Blanchard’s work on Levees overlapped with his work on Lee’s Inside Man. “We were right in the midst of doing Inside Man when Katrina hit,” he explains. “As a matter of fact, I was living in L.A. because I have an apartment out there, and once I found my mom I flew her out there and set her up in an apartment in the same complex, across the courtyard from mine. Now, the amazing thing was, Spike flew to L.A. to come work with me on the music and when he walked into the studio the first thing he said to me was, ‘I’m going to do a documentary on the levees, man. Those people have to be heard.’ He had already been interviewing people before we even got into the studio to record the music for Inside Man.”

When a comment is made that some of the musical cues for Levees seem fragile and trancelike, Blanchard responds enthusiastically. “That’s a good word, trancelike. Because for me, that’s what it was like when you went back to New Orleans and you saw it for the first time after the hurricane. When I stood outside my mom’s house, I heard nothing. I can’t explain it to people, it was like a Hitchcock movie. You couldn’t hear any cars moving, no people moving, no lawnmowers going, no birds, no insects, nothing. The only thing I heard when I stood out in front of my mom’s house was the wind. So it’s like we were all in a daze. And the devastation was so vast we’re still trying to get our heads around the whole thing.”

*****

“People always say luck is when preparation meets opportunity, but I don’t know if I agree,” says Blanchard, the one-time Jazz Messenger (1982-1986) who subsequently co-led a potent hard-boppish quintet with alto saxophonist Donald Harrison through 1989 before forming his own band. “I was totally not prepared to be a film composer when Spike called and asked me to write some music for a scene for Mo’ Better Blues. [Spike’s father, bassist-composer Bill Lee, composed that score while Blanchard provided the trumpet parts for the film’s main character, jazz trumpeter Bleek Gilliam, portrayed by Denzel Washington.]

“What happened was, during a break I was sitting at the piano playing something and Spike comes over and says, ‘Man, I like that. What is that?’ And I tell him it’s a tune I’m working on called ‘Sing Soweto’ for my next album [1992’s Terence Blanchard on Columbia]. And he says, ‘Can I use it?’ So we ended up recording it that day, just as a solo trumpet piece. When Spike shot the scene with Denzel he listened back to it and didn’t really dig how it was coming out. He felt like he needed something more so he asked me if I could write a string arrangement for it. And that’s how my film career started, basically.”

Blanchard’s big breakthrough in the genre came with his second film, Malcolm X, Lee’s controversial blockbuster, which was also the most intensely scrutinized project of his career. “That was the biggest film of my career, of a lot of people’s careers at that point,” recalls Blanchard. “So there was a lot riding on that one. I didn’t want to sound like a novice working on that film so I had to do a lot of homework to score that movie.”

Following the success of Malcolm X, Blanchard revealed his versatility in a string of subsequent releases, including 1995’s moody orchestral score for Clockers, which was wildly different from 1996’s Get On the Bus, which in turn was a whole away from 1999’s Summer of Sam. “And there were learning experiences with each of them,” he says. “Back when we did Clockers, there was a tendency to use a lot of hip-hop music in those movies. But Spike told me, ‘We’re not going to go in that direction.’ He said, ‘I want to bring a certain kind of elegance and respect to these characters. So we’re going to go with orchestra.’ And then when it came to Inside Man, I had to serve two masters, so to speak. It was a big-budgeted Hollywood thriller, so I had to serve the genre, in a sense. But it still had the cinematic vision of Spike Lee, so I had to still give Spike what he was looking for in his film.”

Blanchard has developed a kind of shorthand while working with Lee, which helps expedite his work on these film projects. “It’s gotten to the point now where we don’t need to have a lot of conversations,” says the trumpeter. “I know what he likes. Spike has always been a lover of melody. He likes having a number of strong melodic themes in his films. And he likes orchestra. I try to wean him off of that in some instances, but that’s basically where he’s at, that’s his thing. So we’ve gotten it down to the point now where we talk about concept and approach for a film and we don’t need to talk about much else. Like for Inside Man, he specifically wanted big drums for certain scenes. But other than that, we didn’t have much conversation about the music on that project.”

Blanchard believes that one of the reasons why he has such a good working relationship with Brooklyn native Lee is because Lee is extremely musical. “While he doesn’t play an instrument, you gotta remember who his father is,” he says. “He grew up around music. And he’ll never admit it but he has really good ears. I remember years ago we were in a recording session from a film score and he looked up at me and said, ‘Hey, Terence, those violas are out of tune. We need to go back and do another take.’ And I stopped and said, ‘How did you know the violas were out of tune?’ The violas sit in the middle of the string section. That means that you have to hear the violins above it and hear the celli below the violas and the basses below that to know that the violas were the ones that were out of tune. That’s part of his brilliance. And he doesn’t brag about his ability. But I’m here to tell you, he’s a brilliant guy to work with. “And I really appreciated that he gave all of these people a place to speak on Levees. Who else would’ve given them a chance to speak like that? And I told Spike, ‘Man, I love you for doing this.’ I’ve always been a fan of Spike’s but my respect for him as a humanitarian went sky high because he didn’t do what the news agencies do. He didn’t go out and find the most titillating or salacious person to talk to. He went out and found some very competent, very passionate folks and he interviewed them. They told their stories and I took my cues from them in terms of how to score this film.”

Meanwhile, Blanchard remains steadfastly incensed. “It’s outrageous when you see all of this devastation and it’s not fucking Iraq. This is my hometown, these are streets that I’ve been down, these are areas where I’ve hung out. And it still looks like a war zone. Who could’ve ever imagined that? And the real outrage is to think that it didn’t have to happen. It didn’t have to happen but for our own neglect in terms of the people who are part of the levee board, and how they take the money the government gives them, and they don’t really service the levees. And also in terms of how the governor and the president had their little spats so nobody was allowed to come in to help anybody. It’s just incompetence all around. And the sad part about it is we put our confidence in these people when we go to the ballot box and vote for them. Because when you cast your vote, you cast it with confidence and you think, ‘OK, these guys got it together.’ And to find out that they didn’t have it together, weren’t even in the fucking ballpark, it’s an eye-opening thing.”

Blanchard is on a roll now, burning with righteous indignation. “I find it insulting that the streets aren’t even clean,” he continues. “And I’m outraged that our national media has sort of turned the page on New Orleans. After Katrina hit, we felt that the media was on it. They were calling everybody in the Bush administration out and calling attention to our plight. They were like, ‘Look! This is outrageous!’ But where’s the media now? When the president did the State of the Union address a while back, he didn’t even mention New Orleans, you know? And I know he didn’t want to mention it because we haven’t gotten that $106 billion he promised us. So we tend to kind of move on as a country to the next issue, which is unfortunate. But the way that whole thing was handled, I think it’s grounds for a no-confidence vote, in my opinion.

“And here’s the thing that ultimately angers me about the entire situation: These politicians take the time and make time to come down to all of our cities to kiss our ass for a vote. You know what I’m saying? And when we needed them, after they had gotten the vote, they abandoned us. And that’s just a very fundamental thing in my mind that just really broke my heart when you start talking about Katrina.”

Though Blanchard currently teaches at the Monk Institute (now based out of Loyola University in New Orleans), he declined an invitation to perform with his students at the White House. “I thought it was a great opportunity for the Monk Institute and I’m glad that they went ahead and did it,” he says. “But I told them that I couldn’t be a part of it because there was no way in hell that I would sit down and play music for a person who let people in my hometown suffer and die. Let’s just put it out there … people died! And we can’t be afraid to speak out no more about it. We can’t!”

*****

At age 45, Blanchard is considered both a respected veteran jazz musician and a seasoned composer of film scores. And throughout his career he has been successful in striking a balance between the two disciplines. With his 1998 CD release, Jazz in Film, Blanchard paid a personal tribute to some of the classic Hollywood film scores from yesteryear. “The reason I did that was because I got tired of hearing how jazz doesn’t work in film. I kept hearing that in L.A., ‘Jazz doesn’t really work in movies.’ And I was like, ‘You gotta be kidding!’ I mean, there’s a vast history there, from Duke Ellington’s score for Anatomy of a Murder to Quincy Jones’ score for The Pawnbroker to Elmer Bernstein’s music for The Man with the Golden Arm, Alex North’s music for A Streetcar Named Desire or Jerry Goldsmith’s work on Chinatown. I mean, how many people tried to write a score like Chinatown since that movie came out? You can’t even count ’em, there’s so many! It was a hugely influential film score. And I wanted to pay tribute to that and to all those other great scores that changed the course of music in film.

“I love being a film composer,” he continues. “I’ve studied the genre and I do keep up to date with what’s going on currently with all of the composers who are in the business now. James Newton Howard is a good friend of mine. Miles Goodwin, who has passed on, was a very good friend of mine. So I’m constantly checking out what’s going on with what they’re doing. But at the end of the day, I’m still a jazz musician. That’s what my first love is and always will be.”

Ghost Stories

For his follow-up to 2006’s critically acclaimed and Grammy-nominated Flow, Blanchard expanded on four key themes he utilized in When the Levees Broke as the foundation for A Tale of God’s Will (A Requiem for Katrina), his third album for Blue Note Records. With his working quintet (saxophonist Brice Winston, pianist Aaron Parks, bassist Derek Hodge and drummer Kendrick Scott) augmented by a 40-piece orchestra (the Seattle-based Northwest Sinfonia), Blanchard achieves a grandiose sweep on 13 stirring tracks that run the emotional gamut from despair and grief to catharsis and rage.

“In the aftermath of Katrina, everybody was asking me, ‘Are you writing any new music? Are you hearing anything?’ And I’d say, ‘No, man.’ Because the only thing I heard was silence. I wasn’t hearing anything. But my wife started talking to me about possibly doing some of that music as an album with an orchestra. I thought it was a great idea and the more I thought about it, the more I realized I could interject some more emotion into the piece, addressing some of the anger and frustration that people were feeling. So when you listen to the piece ‘Levees,’ that’s all about the water and people being stuck on rooftops. The trumpet represents those people crying for help and never being heard. And the strings kind of represent that water that’s just hanging around the neighborhood… You know, people are waiting for it to subside, but it’s just there. For five days.”

The reflective “Wading Through,” a simple, elegant melodic fragment played on piano that recurs throughout When the Levees Broke (and was recycled from a theme that originally appeared in Inside Man), is embellished here with flutes, horns and lush strings for a grand, sweeping effect. “The Water,” another key theme from Spike Lee’s documentary, is a darkly evocative meditation on the Crescent City submerged, with Blanchard’s keening trumpet conveying a sense of utter despair.

Blanchard’s talented sidemen each contribute potent pieces that capture their own sadness and frustration over Katrina and its tragic aftermath. “Mantra Intro” is a showcase for Hodge’s expressive chordal work on electric bass that segues to drummer Scott’s contemplative “Mantra,” a musical prayer for healing and renewal that swells to some dynamic orchestral flourishes, with Blanchard’s brilliant high note work riding on top. “The tune just builds and speaks to all of our reactions to Katrina,” says Blanchard. “And it also addresses our disbelief, like where you’re in a daze and you just get to this point where you want to scream.”

Pianist Parks contributes the uplifting, Coplandesque heartland number “Ashé” (which, translated from the Yoruban language, means “Amen”). And Winston’s melancholic “In Time of Need” showcases his fluid tenor sax playing alongside Blanchard’s superb trumpet work, against a haunting piano ostinato, mesmerizing tablas and stirring counterpoint from the strings.

A series of sparsely arranged “ghost” tunes serve as brief interludes throughout the album and help put the tragedy of Katrina into a historical perspective. The driving African-flavored opener “Ghost of Congo Square,” which incorporates the rhythmic chant, “This is the tale of God’s will,” represents the warnings of the past. The jaunty tumbao-fueled trumpet-bass duet on “Ghost of Betsy” is a reminder from 1965, the last time that a hurricane wreaked havoc on the Crescent City. And “Ghost of 1927,” a sax-percussion duet, is a reminder of the Great Mississippi River Flood from 80 years ago, when New Orleans bankers and politicians conspired to dynamite the levees upriver at Caernarvon, La., resulting in wide-scale flooding in the Plaquemines and St. Bernard parishes.

“I had this idea of doing these little motifs and calling them ghosts,” explains Blanchard. “From a spiritual standpoint, it’s almost like some of these ghosts have been trying to tell us, ‘Put your house in order.’ And the trumpet actually represents some of the spirits that are screaming, trying to tell us what’s about to happen if we don’t put our house in order.”

Blanchard’s other compositions here are the aptly titled “Funeral Dirge,” underscored by Scott’s ominous march beat and Blanchard’s melancholy string arrangement, and the poignant closer “Mom,” a beautiful balladic tribute to the courage of Wilhelmina Blanchard. “I was just proud of my mom for doing what she did. I didn’t know how to say it … but I just would like something to kind of express how I felt.”

Regarding the album’s title, Blanchard turns philosophical. “When you start to ask the bigger question as to why this all happened, the only thing you can come up with is that it’s God’s will,” he says. “I grew up in the church and I’ve been a firm believer that God does things in mysterious ways. And there’s been a lot of tragedy, but there’s also been a lot of good that’s come out of this. For example, a lot of people in New Orleans now are realizing that they can’t go to the government for help. So you have church groups along with business folks, people who probably would’ve never worked together at all, coming together to try to make things better in the city. Those who stayed and those who are now moving back to New Orleans are helping to rebuild the city by making our educational system better and make other services in the city better.

“So in the bigger picture, I have to believe that this was done to learn something and there’s gonna be something better on the other side of it,” he adds. “I have to believe that. And I’m not trying to shove my beliefs on anybody, but I do think people should at least reflect on some other possibilities for why this thing occurred, and why people are suffering and going through this.”

by Bill Milkowski

Of all the scores that Blanchard has composed over the past 17 years, easily his most cathartic and emotionally wrenching project to date was composing the music for Lee’s provocative HBO documentary, When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. A chilling account of what Hurricane Katrina wrought on the city of New Orleans that tragic day in August 2005, it is also a stinging indictment of the Bush administration’s utter neglect of Americans who were left to die in the flooded Crescent City. New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin, Louisiana governor Kathleen Babineaux Blanco and the Army Corps of Engineers are also taken to task in Lee’s remarkable four-hour documentary, which is underscored by Blanchard’s poignant and melancholy motifs.

But more than just fingerpointing, When the Levees Broke is a powerful narrative woven together by impassioned testimony from those who survived to tell the tale of devastation and abandonment. And Blanchard’s elegant, moving score reflects their grief and frustration while also channeling their hope and optimism in the face of overwhelming odds.

Considering that he was a subject of the Levees documentary as well as the composer of its haunting score, Blanchard had far more invested emotionally in this project than any other he’d done before with Lee. “It was very difficult because it was the first time that I couldn’t take a break from a project,” says Blanchard. “You know, you work on projects that are very dear to you and very heartfelt, and when you hit a wall you can take a break, step outside, go to lunch, hang out with the family, do whatever. But I couldn’t do that on Levees. Because taking a break meant I had to go and check on what was going on with my mom’s house, what was going on with my mom. And that meant driving through a city that had no street lights or stop signs anywhere, where there was total devastation on 80 percent of the properties. So it was a difficult time. And the craziest thing about it is whenever I speak about that I always have to end it by saying, ‘You know, with all of that, we still feel like we were the lucky ones.’”

One of many thousands of displaced New Orleanians (who were later callously referred to by the media as “refugees”), Blanchard delivers scathing testimony in the film. In one candid scene he declares, “It pisses you off because it didn’t have to happen.” Indeed, the breaking of the levees has been called “the most tragic failure of a civil-engineered system in the history of the United States.”

In one telling scene, the trumpeter is filmed walking through the city’s Lower Ninth Ward, playing “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” while Lee’s camera scans the endless devastation, capturing the utter despair of a neighborhood that was home to Fats Domino and other proud residents. As one outraged resident of the Lower Ninth Ward states in the film, “This is what’s left. Your whole history under a pile of rubble. This is a good neighborhood that’s gone, man.”

In one of the most heart-wrenching scenes of the film, Blanchard comforts his mother, who breaks down in tears upon encountering the complete destruction of her home along with a lifetime of memories. “It was hard for all of us,” he says of filming that very touching moment. “I remember asking her, ‘You sure you want to do this? Because … that’s gonna be like having all these people following you around during this very private moment.’ And her thing was, ‘Well, people need to see what we’re going through in New Orleans.’ So when you watch the film, don’t just look at her. Take her experience and multiply that by a hundred thousand because there’s so many people who have had the exact same experience or worse.”

Watching these and other scenes of human tragedy that permeate all four acts of Levees, it is nearly impossible to suppress feelings of anger at the sheer incompetence that led to devastation on such staggering scale. If Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 hadn’t already made the point, Lee’s When the Levees Broke drives it home: Bush and his cronies at FEMA and Homeland Security are asleep at the wheel. There’s no other explanation for the bureaucratic bungling and foot-dragging that resulted in five days of inaction while stranded people waved SOS banners from rooftops and bloated carcasses floated facedown in the toxic waters that flooded Crescent City streets.

It would seem the only reasonable response to those disheartening scenes is one of pure rage. If someone else had been scoring this documentary, it might’ve been roaring with dissonance, throbbing with polyrhythms and power chords and skronking with cathartic feedback squalls—all tossed in as an iron fist upside the head of the Bush administration and all the incompetents at FEMA, Homeland Security and the Army Corps of Engineers. But Blanchard chose another path in scoring Levees.

“Anger is an obvious direction to go in and that’s a very valid emotion to have,” he says. “But with this music, I was really trying to stay out of the way of all of those amazing stories which, to me, was the most important thing about the Levees documentary. So I didn’t want the music to be very complicated or cloud people’s judgment. I wanted the music to put people in a very reflective kind of mood so they could sit back and just experience these stories that are being told. These were truly sympathetic characters in the cinematic sense of the word. And the music, to me, had to play a vital role in not pushing that too far but just allowing that to exist. And again, it’s hard for me to take credit for that because, for me, I’m just reacting to what I’m watching on the screen.”

As it turned out, Blanchard’s work on Levees overlapped with his work on Lee’s Inside Man. “We were right in the midst of doing Inside Man when Katrina hit,” he explains. “As a matter of fact, I was living in L.A. because I have an apartment out there, and once I found my mom I flew her out there and set her up in an apartment in the same complex, across the courtyard from mine. Now, the amazing thing was, Spike flew to L.A. to come work with me on the music and when he walked into the studio the first thing he said to me was, ‘I’m going to do a documentary on the levees, man. Those people have to be heard.’ He had already been interviewing people before we even got into the studio to record the music for Inside Man.”

When a comment is made that some of the musical cues for Levees seem fragile and trancelike, Blanchard responds enthusiastically. “That’s a good word, trancelike. Because for me, that’s what it was like when you went back to New Orleans and you saw it for the first time after the hurricane. When I stood outside my mom’s house, I heard nothing. I can’t explain it to people, it was like a Hitchcock movie. You couldn’t hear any cars moving, no people moving, no lawnmowers going, no birds, no insects, nothing. The only thing I heard when I stood out in front of my mom’s house was the wind. So it’s like we were all in a daze. And the devastation was so vast we’re still trying to get our heads around the whole thing.”

*****

“People always say luck is when preparation meets opportunity, but I don’t know if I agree,” says Blanchard, the one-time Jazz Messenger (1982-1986) who subsequently co-led a potent hard-boppish quintet with alto saxophonist Donald Harrison through 1989 before forming his own band. “I was totally not prepared to be a film composer when Spike called and asked me to write some music for a scene for Mo’ Better Blues. [Spike’s father, bassist-composer Bill Lee, composed that score while Blanchard provided the trumpet parts for the film’s main character, jazz trumpeter Bleek Gilliam, portrayed by Denzel Washington.]

“What happened was, during a break I was sitting at the piano playing something and Spike comes over and says, ‘Man, I like that. What is that?’ And I tell him it’s a tune I’m working on called ‘Sing Soweto’ for my next album [1992’s Terence Blanchard on Columbia]. And he says, ‘Can I use it?’ So we ended up recording it that day, just as a solo trumpet piece. When Spike shot the scene with Denzel he listened back to it and didn’t really dig how it was coming out. He felt like he needed something more so he asked me if I could write a string arrangement for it. And that’s how my film career started, basically.”

Blanchard’s big breakthrough in the genre came with his second film, Malcolm X, Lee’s controversial blockbuster, which was also the most intensely scrutinized project of his career. “That was the biggest film of my career, of a lot of people’s careers at that point,” recalls Blanchard. “So there was a lot riding on that one. I didn’t want to sound like a novice working on that film so I had to do a lot of homework to score that movie.”

Following the success of Malcolm X, Blanchard revealed his versatility in a string of subsequent releases, including 1995’s moody orchestral score for Clockers, which was wildly different from 1996’s Get On the Bus, which in turn was a whole away from 1999’s Summer of Sam. “And there were learning experiences with each of them,” he says. “Back when we did Clockers, there was a tendency to use a lot of hip-hop music in those movies. But Spike told me, ‘We’re not going to go in that direction.’ He said, ‘I want to bring a certain kind of elegance and respect to these characters. So we’re going to go with orchestra.’ And then when it came to Inside Man, I had to serve two masters, so to speak. It was a big-budgeted Hollywood thriller, so I had to serve the genre, in a sense. But it still had the cinematic vision of Spike Lee, so I had to still give Spike what he was looking for in his film.”

Blanchard has developed a kind of shorthand while working with Lee, which helps expedite his work on these film projects. “It’s gotten to the point now where we don’t need to have a lot of conversations,” says the trumpeter. “I know what he likes. Spike has always been a lover of melody. He likes having a number of strong melodic themes in his films. And he likes orchestra. I try to wean him off of that in some instances, but that’s basically where he’s at, that’s his thing. So we’ve gotten it down to the point now where we talk about concept and approach for a film and we don’t need to talk about much else. Like for Inside Man, he specifically wanted big drums for certain scenes. But other than that, we didn’t have much conversation about the music on that project.”

Blanchard believes that one of the reasons why he has such a good working relationship with Brooklyn native Lee is because Lee is extremely musical. “While he doesn’t play an instrument, you gotta remember who his father is,” he says. “He grew up around music. And he’ll never admit it but he has really good ears. I remember years ago we were in a recording session from a film score and he looked up at me and said, ‘Hey, Terence, those violas are out of tune. We need to go back and do another take.’ And I stopped and said, ‘How did you know the violas were out of tune?’ The violas sit in the middle of the string section. That means that you have to hear the violins above it and hear the celli below the violas and the basses below that to know that the violas were the ones that were out of tune. That’s part of his brilliance. And he doesn’t brag about his ability. But I’m here to tell you, he’s a brilliant guy to work with. “And I really appreciated that he gave all of these people a place to speak on Levees. Who else would’ve given them a chance to speak like that? And I told Spike, ‘Man, I love you for doing this.’ I’ve always been a fan of Spike’s but my respect for him as a humanitarian went sky high because he didn’t do what the news agencies do. He didn’t go out and find the most titillating or salacious person to talk to. He went out and found some very competent, very passionate folks and he interviewed them. They told their stories and I took my cues from them in terms of how to score this film.”

Meanwhile, Blanchard remains steadfastly incensed. “It’s outrageous when you see all of this devastation and it’s not fucking Iraq. This is my hometown, these are streets that I’ve been down, these are areas where I’ve hung out. And it still looks like a war zone. Who could’ve ever imagined that? And the real outrage is to think that it didn’t have to happen. It didn’t have to happen but for our own neglect in terms of the people who are part of the levee board, and how they take the money the government gives them, and they don’t really service the levees. And also in terms of how the governor and the president had their little spats so nobody was allowed to come in to help anybody. It’s just incompetence all around. And the sad part about it is we put our confidence in these people when we go to the ballot box and vote for them. Because when you cast your vote, you cast it with confidence and you think, ‘OK, these guys got it together.’ And to find out that they didn’t have it together, weren’t even in the fucking ballpark, it’s an eye-opening thing.”

Blanchard is on a roll now, burning with righteous indignation. “I find it insulting that the streets aren’t even clean,” he continues. “And I’m outraged that our national media has sort of turned the page on New Orleans. After Katrina hit, we felt that the media was on it. They were calling everybody in the Bush administration out and calling attention to our plight. They were like, ‘Look! This is outrageous!’ But where’s the media now? When the president did the State of the Union address a while back, he didn’t even mention New Orleans, you know? And I know he didn’t want to mention it because we haven’t gotten that $106 billion he promised us. So we tend to kind of move on as a country to the next issue, which is unfortunate. But the way that whole thing was handled, I think it’s grounds for a no-confidence vote, in my opinion.

“And here’s the thing that ultimately angers me about the entire situation: These politicians take the time and make time to come down to all of our cities to kiss our ass for a vote. You know what I’m saying? And when we needed them, after they had gotten the vote, they abandoned us. And that’s just a very fundamental thing in my mind that just really broke my heart when you start talking about Katrina.”

Though Blanchard currently teaches at the Monk Institute (now based out of Loyola University in New Orleans), he declined an invitation to perform with his students at the White House. “I thought it was a great opportunity for the Monk Institute and I’m glad that they went ahead and did it,” he says. “But I told them that I couldn’t be a part of it because there was no way in hell that I would sit down and play music for a person who let people in my hometown suffer and die. Let’s just put it out there … people died! And we can’t be afraid to speak out no more about it. We can’t!”

*****