SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER ONE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2015

VOLUME ONE NUMBER ONE

MILES DAVIS

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

ANTHONY BRAXTON

November 1-7

CECIL TAYLOR

November 8-14

STEVIE WONDER

November 15-21

JIMI HENDRIX

November 22-28

GERI ALLEN

November 29-December 5

HERBIE HANCOCK

December 6-12

SONNY ROLLINS

December 13-19

JANELLE MONÀE

December 20-26

GARY CLARK, JR.

December 27-January 2

NINA SIMONE

January 3-January 9

ORNETTE COLEMAN

January 10-January 16

WAYNE SHORTER

January 17-23

*[Special

bonus feature: A celebration of the centennial year of musician,

composer, orchestra leader, and philosopher SUN RA, 1914-1993]

January 24-30

http://www.npr.org/2007/04/16/9607210/ornette-coleman-wins-music-pulitzer

Ornette Coleman Wins Music Pulitzer

Today's Pulitzer Winners (partial list):

Cormac McCarthy The Road (fiction) David Lindsay-Abaire Rabbit Hole (drama)

Natasha Trethewey Native Guard (poetry)

Lawrence Wright The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 (general non-fiction)

Debby Applegate The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher (biography)

Renee C. Byer (feature photography)

Ornette Coleman's Pulitzer-winning recording features Ornette Coleman: saxophone, violin, trumpet; Denardo Coleman: drums; Gregory Cohen and Tony Falanga: basses.

More on Today's Pulitzer Prize

'Journal' Leads With Two Pulitzer Prizes

April 16, 2007

Ornette Coleman has won the Pulitzer Prize for music with his recording Sound Grammar, a document of a 2005 concert recorded live in Italy.

Ornette Coleman, 77, has won the 2007 Pulitzer prize for music. Getty Images

Coleman's music was not among the 140 music nominees. Pulitzer panelists used their prerogative to skirt traditional rules by purchasing the CD and nominating the 77-year-old jazz master. This is the first time a recording has won the music Pulitzer, and a first for purely improvised music. The concert features an unorthodox line-up of instruments, including two double basses (one plucked, the other bowed), Coleman's son Denardo on drums, and Coleman himself playing alto saxophone and trumpet. Coleman has continued to shake up the jazz world ever since releasing his innovative recording The Shape of Jazz to Come in 1959. Born in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1930, Coleman received his first saxophone at age 14. His mother saved money to buy the instrument by working as a seamstress. At first, Coleman struggled to find his own sound on the alto saxophone, but eventually developed his own formulas of composition, breaking down traditional definitions of harmony and melody. The concept, called "Harmolodic," Coleman says, removes the caste system from sound. Coleman has written music outside of the jazz realm, including string quartets, music for dance, woodwind quintets, and in the early 1970s, a symphony called Skies of America, composed with support from his Guggenheim Foundation Grant.

In 1994, Coleman earned a MacArthur Genius award, and has been inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Related NPR Stories:

Dec. 14, 2006

Nov. 13, 2006

Aug. 23, 2005

Aug. 1, 2001

Featured Artist

http://www.wsj.com/articles/completely-new-yet-pleasantly-familiar-jazz-review-of-ornette-colemans-new-vocabulary-system-dialing-recordings-1420672249

Completely New Yet Pleasantly Familiar

By Martin Johnson

January 7, 2015

Wall Street Journal

With shockingly little advance publicity, a new recording featuring jazz great Ornette Coleman has been released. The album, “New Vocabulary” (System Dialing Recordings), became available late last month via the label’s website, and it features the innovative saxophonist and composer in a collective ensemble that includes trumpeter Jordan McLean, drummer Amir Ziv and keyboardist Adam Holzman.

The release comes at a time when new music from Mr. Coleman has grown scarce. He made a guest appearance on one track of “Road Shows Vol. 2” (Doxy), a 2011 release by fellow saxophone legend Sonny Rollins. His last official recording was “Sound Grammar” (Sound Grammar), a live recording from 2006, which received the Pulitzer Prize for music the following year. His last studio recording was “Sound Museum: Three Women” (Harmolodic/Verve) in 1996.

Ornette Coleman’s ‘New Vocabulary’ is his first studio album since 1996. Getty Images

Mr. Coleman, who is 84, is one of the most pivotal figures in jazz history. In the late ’50s, he arrived on the scene, first in Los Angeles and then in New York, with an approach to music that loosened the rules of harmony and freed musicians to play more of what they felt. The approach was often called free jazz, a name taken from one of Mr. Coleman’s best recordings of the time. Later in the ’60s, he was one of the first jazz musicians to compose string quartets. His band in the ’70s produced classic recordings like “Science Fiction” (Columbia, 1971), and in 1976 he released his first recording with Prime Time, a band featuring electric guitars and basses that seamlessly combined jazz and funk.

Although its arrival was a surprise, the timing of the release of “New Vocabulary” is entirely appropriate. Mr. Coleman’s music was the subject of two heralded tributes in 2014. In October, The Bad Plus performed the entire “Science Fiction” recording in a series of concerts; in June, music luminaries including Mr. Coleman himself played his works in a Celebrate Brooklyn concert called “Celebrate Ornette.”

The new album was recorded in 2009. A year earlier, Mr. Coleman had attended the musical “Fela!” Afterward, he went backstage and met Mr. McLean, who was assistant musical director for the production and is a member of Antibalas, the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based Afrobeat band that arranged and performed the show’s music. The two men became friends, and Mr. Coleman invited Mr. McLean, who is 40, to his home to play music. Those sessions evolved to include Messrs. Ziv and Holzman, Mr. McLean’s bandmates in an electronic music group called Droid. Mr. Ziv, who is 43, has been a leading sideman for more than 20 years; his credits include work with Sean Lennon, Lauryn Hill, and Medeski, Martin and Wood. Mr. Holzman, who is 56 and leads several bands, has played with Miles Davis and Chaka Khan. Informal jamming gradually became more rigorous rehearsals as the musicians honed the 12 songs that appear on the recording.

“New Vocabulary” is a concise 42 minutes, and it begins with two spare tunes, “Baby Food” and “Sound Chemistry,” that contrast Mr. Coleman’s bright, often gleeful saxophone tone with electronic effects by Mr. McLean and piano from Mr. Holzman. From there the intensity picks up on pieces like “Alphabet,” “Bleeding,” “If it Takes a Hatchet” and “H20” as Mr. Ziv’s drumming becomes more prominent and both Mr. Coleman and Mr. McLean accent and play off of his driving rhythms. The album ends with “Gold is God’s Sex,” a ruminative piece that lends the recording a bit of symmetry.

Most Ornette Coleman projects offer either something completely new or something closely related to what he has done in the past. Prime Time and the band on “Sound Museum” were radical shifts. “Science Fiction,” built on the Blue Note recordings that preceded it, and “Sound Grammar” placed Coleman in a familiar setting—a quartet—with repertoire from his lengthy career. “New Vocabulary” does a little of both. Without directly quoting melodies, Mr. Coleman’s playing at times recalls his work in the early ’60s, early ’70s and late ’80s. Yet the backing is completely new for those who know his work only via recordings, and Mr. Coleman sounds energized by his bandmates. One can only hope it is a direction he will continue to pursue. Despite its under-the-radar launch, “New Vocabulary” is a valuable addition to Ornette Coleman’s extraordinary discography.

Mr. Johnson writes about jazz for the Journal.

ORNETTE COLEMAN SPEAKING:

"It was when I found out I could make mistakes that I knew I was on to something."

"Jazz, rock, pop, blues, gospel, and classical are all yesterday's titles. I'm playing the music of today..."

"Play the music, not the background"

"Sound is to people what the sun is to light""You don't have to worry about being a number one, number two, or number three. Numbers don't have anything to do with placement. Numbers only have something to do with repetition."

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2011/03/legendary-ornette-coleman-b-1930-happy.html

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

THE LEGENDARY ORNETTE COLEMAN (b. 1930)

HAPPY 81ST BIRTHDAY ORNETTE!

All,It is impossible to overstate the monumental significance of the astonishing musical art and vision of the consummate musician, composer, arranger, conductor, philosopher, and prophet Ornette Coleman (b. March 9, 1930 in Fort Worth, Texas). For over 50 years (!) Ornette has been a major innovator in, and creative influence on, the rich global history of improvisational and structured ensemble music alike. A grandmaster of the myriad forms, genres, and expressive/conceptual traditions and strutural legacies of Jazz, Blues, R & B, Funk, 'classical' 'Pop', and spiritual musics Coleman has left an indelible mark on the art world generally through not only his many extraordinary recordings and live performances throughout the U.S., Asia, Europe, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Pacific islands but through his electrifying and highly original creative collaborations with singers, dancers, painters, poets, visual artists (film and painting), architects, scientists, actors, martial artists, and playwrights. In celebration of the 81st birthday of this truly great artist and amazing human being what follows are a series of writings and commentary by and about Ornette by a number of different sources including critics, fellow artists, and historians. I have also contributed some of my own writing on and about Ornette and his music over the years. ENJOY...

Kofi

HAPPY BIRTHDAY ORNETTE!

http://www.npr.org/blogs/ablogsupreme/2010/09/24/130105770/why-we-love-ornette-coleman

http://www.tedkurland.com/artists/ornette-coleman

ORNETTE COLEMAN

September 24, 2010

Rarely does one person change the way we listen to music, but such a man is ORNETTE COLEMAN. Since the late 1950s, when he burst on the New York jazz scene with his legendary engagement at the Five Spot, Coleman has been teaching the world new ways of listening to music. His revolutionary musical ideas have been controversial, but today his enormous contribution to modern music is recognized throughout the world.

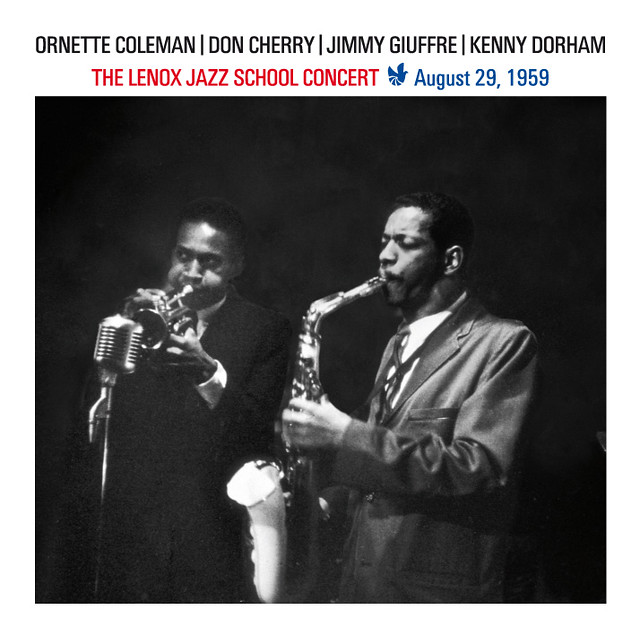

Coleman was born in Fort Worth, Texas in 1930 and taught himself to play the saxophone and read music by the age of 14. One year later he formed his own band. Finding a troublesome existence in Fort Worth surrounded by racial segregation and poverty, he took to the road at age 19. During the 1950s while in Los Angeles, Ornette's musical ideas were too controversial to find frequent public performance possibilities. He did, however, find a core of musicians who took to his musical concepts: trumpeters Don Cherry and Bobby Bradford, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins, and bassist Charlie Haden.

In 1958, with the release of his debut album SOMETHING ELSE, it was immediately clear that Coleman had ushered in a new era in jazz history. This music, freed from the prevailing conventions of harmony, rhythm, and melody, often called 'free jazz' transformed the art form. Coleman called this concept Harmolodics. From 1959 through the rest of the 60s, Coleman released more than fifteen critically acclaimed albums on the Atlantic and Blue Note labels, most of which are now recognized as jazz classics. He also began writing string quartets, woodwind quintets, and symphonies based on Harmolodic theory.

In the early 1970s, Ornette traveled throughout Morocco and Nigeria playing with local musicians and interpreting the melodic and rhythmic complexities of their music into this Harmolodic approach. In 1975, seeking the fuller sound of an orchestra for his writing, Coleman constructed a new ensemble entitled Prime Time, which included the doubling of guitars, drums, and bass. Combining elements of ethnic and danceable sounds, this approach is now identified with a full genre of music and musicians. In the next decade, more surprises included trend-setting albums such as SONG X with guitarist Pat Methany, and Virgin Beauty featuring Grateful Dead leader Jerry Garcia.

The 1990s included other large works such as the premier of Architecture in Motion, Ornette's first Harmolodic ballet, as well as work on the soundtracks for the films "Naked Lunch" and "Philadelphia." With the dawning of the Harmolodic record label under Polygram, Ornette became heavily involved in new recordings including Tone Dialing, Sound Museum, and Colors. In 1997, New York City's Lincoln Center Festival featured the music and the various guises of Ornette over four days, including performances with the New York Philharmonic and Kurt Masur of his symphonic work, Skies of America.

There has been a tremendous outpouring of recognition bestowed upon Coleman for his work, including honorary degrees from the University of Pennsylvania, California Institute of the Arts, and Boston Conservatory, and an honorary doctorate from the New School for Social Research. In 1994, he was a recipient of the distinguished MacArthur Fellowship award, and in 1997, was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. In 2001, Ornette Coleman received the prestigious Praemium Imperiale award from the Japanese government. Ornette won the Pulitzer Prize for Music for his 2006 album, SOUND GRAMMAR, the first jazz work to be bestowed with the honor. In 2008, he was inducted into the Nesuhi Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame. The NEJHF honors legendary musicians whose singular dedication and outstanding contribution to this art shaped the landscape of jazz.

CELEBRATING ORNETTE

by Patrick Jarenwattananon (for NPR.org)

September 24, 2010

This past weekend, The Jazz Gallery in New York hosted a three-day festival called Celebrating Ornette Coleman. As tributes to the jazz legend go, this one was special.

For one, the lineup was packed with stars and musician's musicians: Mark Turner, Joe Lovano, Nasheet Waits, Johnathan Blake, Kevin Hays and Joel Frahm were leading bands with such sidepersons as Matt Wilson, Seamus Blake, Marcus Gilmore, Stanley Cowell, Avishai Cohen, Joey Baron and more. (The collaborative trio of Vijay Iyer, Matana Roberts and Gerald Cleaver also performed.) For another, The Jazz Gallery was a small room usually committed to the up-and-coming generation of artists — last weekend, they were packed with artists who often command theaters and weeklong club runs. And as a third, the shows were presented by Jimmy Katz, the jazz portrait photographer and audio engineer. With his wife, Katz raised all the funds; he also recorded the shows, and the musicians got their masters. There were no guidelines for how each group played their tributes.

In advance of the performance, I reached out to a number of the artists that performed last weekend for their brief thoughts on Ornette Coleman. Here's what I got back.

What makes Ornette Coleman special for you? Leave us a comment.

Mark Turner, saxophones: Master Ornette Coleman knows where he comes from, where he is and where he wants to go.

Joe Martin, bass: As a bassist, Ornette's music enlightens how crucial, beautiful, and dramatic the relationship between a bass line and melody is. (Of course melody and bass line counterpoint have always existed, but for me hearing Ornette's music showed me that even without a specific harmony, this said relationship is even more pronounced, perhaps essential.)

Johnathan Blake, drums: Ornette's fearlessness and honesty is a constant inspiration to me. I've always loved the humor that he puts inside his music.

Joel Frahm, saxophone: For me, Ornette is a great example of the power of flow in music; when I listen to him, I feel like he's never out to prove something to anybody. It's more like discovery and reaction. For me, he's hard to talk or write about without feeling like words are completely useless to describe him.

Matt Wilson, drums: Mr. Coleman personifies courage. He persevered through intense scrutiny and criticism to convey his sonic message. That alone is a reason to celebrate this American master.

Did you know that Ornette Coleman once commented at a rehearsal, "Let's find the right temperature for this tune"? Is that hip or what? BIG love to Maestro Coleman!

Matana Roberts, saxophone: Ornette Coleman is a saxophonist in a class all by himself. He stands for what making interesting art is all about — having a voice all of one's own, but having a creative spirit that is wide open, selflessly nuturing and welcoming to collectivity and celebration of the human experience

Seamus Blake, saxophone: Ornette has profoundly touched and influenced every important jazz musician since he first recorded in 1958. The genius and stylings of Wayne Shorter, Joe Lovano, Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny and John Scofield as well as many, many more greats owe a great deal to Mr Coleman. He is without a doubt as crucial a figure in jazz as Charlie Parker.

Nasheet Waits, drums: What Ornette Coleman represents to me is a fierce dedication to being yourself. He listens to the inner voice whose source is within and beyond.

Vijay Iyer, piano: Ornette Coleman's music combines conceptual innovation, rigorous detail, and profound emotional resonance. He completely changed the music we know and love, and yet his ongoing impact extends well beyond the "jazz" world, into punk rock, American literature, cinema and contemporary art. To me, the best way to pay tribute to Mr. Coleman is to follow his lead — i.e., to be radically, audaciously yourself. (09/28/10)

Ornette Coleman Artist Page

Ornette taught himself how to play the tenor saxophone at the age of fourteen. Coleman found the poverty and racism surrounding him to be too much too bear and hit the road at age nineteen. Coleman first traveled around with Silas Green from a New Orleans variety show and with various rhythm and blues bands. After being assaulted by a white mob after a live show his saxophone was destroyed and he then switched to alto and headed west to Los Angeles with Pee Wee Crayton's band. In Los Angeles Ornette began pursued his own musical visions much more so and became quickly controversial and had difficulties finding places to play. He was however able to find a core group of musicians to play with that included Don Cherry, Bobby Bradford, Ed Blackwell, Billy Higgins and Charlie Haden.

Coleman made Jazz history in 1958 with his album 'Something Else' with Don Cherry, Higgins, Don Payne and Walter Norris. Ornette's playing was not from the mainstream perspective of harmony, rhythm and melody and approached music with total freedom. All of the musical ideas incorporated in Coleman's music were not new per say because they did all exist in different cultures around the world but these ideas were newer to Western/European music and certainly Jazz in America at that time and Coleman called the concept Harmolodics. Through the 1960s Coleman recorded over fifteen albums on Atlantic and Blue Note and most are classics including 'Tomorrow Is the Question!', 'The Shape of Jazz to Come', 'Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation' and many more.

In the 1970s Ornette traveled the world including Morocco and Nigeria and sought out local musicians in these places to play with and tried to soak up as much of their music as possible. Coleman took the differences in melodic and rhythmic approach from these musicians and constructed a new band called Prime Time with two guitars, two bass players and two drummers in order to capture and incorporate these new sounds. Ornette continued working through these new concepts into the 1980s and recorded such 'avantgarde' and popular albums 'Song X' with Pat Methany and 'Virgin Beauty' with Jerry Garcia. In the '90s Coleman created Architecture in Motion, which is a ballet based on his Harmolodic concept and worked on soundtracks for films including Naked Lunch and Philadelphia. He also released three major albums during the decade 'Tone Dialing', 'Sound Museum' and 'Colors'.

Ornette Coleman continues to perform to this day though not too often and any chance to see him must be taken advantage of. Coleman has received many awards including a honorary doctorate from New School University, a MacArthur Fellowship award, and the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his album 'Sound Grammar' in 2007

ORNETTE: IN ALL LANGUAGES

(For Ornette Coleman)

Ornette sings the breakneck passion

song while resting in the lilting liquid light

that becomes him

His sound a heady rhythmic

nomenclature on starry melodic nights

His horn erupts into turquoise flames

A turning toward Terror is not his style though he

casually conjures tempestuous histories

soaring over smokey black earths

Bluesy constellations emerging from our most hidden desires

Poem by Kofi Natambu

(from: The Melody Never Stops, Past Tents Press, 1991)

The Blues in 4-D

by Kofi Natambu

Detroit Metro Times

June, 1982

For over 20 years now, Ornette Coleman has been a major innovative force in world music. During this period Coleman has been able to consistently change the direction of his music and still greatly influence other musicians. Ornette has been able to do this in spite of the fact that his massive achievements have often been misunderstood, vilified, ridiculed or patronized by dense white American “music critics.” Through it all, Coleman has prevailed because his artistic vision is so clear, strong and compelling that no opposition could stop him. Like most “great masters,” Ornette has been forced to fight for his art.

That is why Coleman’s latest recording, Of Human Feelings, is such an inspiring triumph. In this record we get an intimate look at a brilliant musician/composer organizing the varied elements of his music into a multi-tonal mosaic of great power, humor, color, wit, sensuality, compassion and tenderness. The fact that Ornette has once again managed to create such intelligent and passionate music using only the most venerable and fundamental of all African-American “forms” (i.e. the Blues) as an aesthetic focus is cause for celebration in a culture that worships gimmicks and cant over vision and heart. It is also an indication that like all truly “great artists,” Ornette recognizes and uses the eternal value(s) of simplicity. Of course, as any working artist can tell you, this is one of the most difficult things to do. Luckily for the rest of us, this is Coleman’s strength.

In this record, Ornette and his now six-year-old Prime Time Band never lose sight of the essential conceptual and spiritual aspects of Ornette’s musical philosophy: “Play the music, not the background.” In the eight pieces on this recording, as in all of Ornette’s music, the emphasis is never on virtuoso pyrotechnics for their own sake, or in empty stylistic phrase mongering. In every composition there is a synergy of thought and feeling that communicates instantly. There is always a dynamic unity of structure and execution that is performed with spirit and expressive animation. Coleman’s intricate and functional knowledge of black creative music tradi tions allows him to do this in a deceptively easy manner. The music literally pours out of this ensemble in strains of melody and rhythm that sums up the last 100 years of creative development in Afro-American music.

This awesome command is augmented, in Coleman’s case, with a very strong emotional affinity for the most ancient and basic “folk musics” developed by black people in the New World. Thus, in this recording there are rocking riff figures, field hollers, intensely lyrical worksongs, roaring call-and-response counterpoint, wailing melodic laments and exultations, wry little stompdown ditties and jumptime rent part be-bopping. There are also multi-rhythmic chants, sound clusters, tonal density and instrumental speechmaking. This colorful tapes try is held together by Coleman’s famous Harmolodic method, a theoretical construct that Ornette devised in the early 1970s to “allow all instruments in the band the equal opportunity to lead at any time...” This means that all members of the band can play melodic lines in any key at any time, because structurally the tempo, the rhythm and the harmonics are all equal in terms of what they can express. There is a constant modulation of tonality and rhythms as a result. In this liberated environmental setting the tonal “jumping-off point” is always the Blues, and I mean all kinds of Blues!

Ornette plays every conceivable Blues ever invented and a few that he introduced to the world. In every sound, gesture, cadence and juxtaposition. Coleman reminds us that without the Blues there would be no “jazz,” no “rock,” no “pop,” no “funk,” no “punk.” In short, no American vernacular music, just bland one-dimensional imitations of European, Asian, Latin and African musics. It is a humbling and sobering thought that makes us reflect even as we dance like mad to the throbbing, driving rhythms. Strangely, despite the echoes of Robert Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter, Muddy Waters, B.B. King and Jimi Hendrix (among many others) throughout this music, the overall effect is unlike any Blues you have heard before. This is because of what Coleman does with the form in contemporary terms.

Meanwhile, Ornette rides the swelling and descending crest of these tidal waves of melody and sound through keening, darting and singing improvisations that convey a very wise and ancient message. This is the eternal blues message of joyful affirmation in the face of adversity and despair. A “heroism” based on hard-won experience and not media posturing. Whether shouting, screaming, moaning, laughing, crying or sighing, the music in Of Human Feelings never fails to express this message that lifts you higher and makes you dance no matter what “the problem.” The energy derived from the spirit of this recording is the “solution” to our problems. In fact, the title of one of Ornette’s tunes in this recording is “What is the Name of that Song?” I betcha Reagan doesn’t know. I hope we do.

Ornette Coleman's 'Sound Grammar' first jazz work awarded Pulitzer Prize

By JAKE COYLE

Associated Press

April 24, 2007

NEW YORK -- Ornette Coleman won the Pulitzer Prize for music on Monday for his 2006 album, "Sound Grammar," the first jazz work to be bestowed with the honor. The alto saxophonist and visionary who led the free jazz movement in the 1950s and 1960s, won the Pulitzer at age 77 for his first live recording in 20 years. The only other jazz artist to win a Pulitzer is Wynton Marsalis, who won in 1997 for his classical piece, "Blood on the Fields."

The Pulitzer Prize for music, an award founded in 1943, has always focused on classical music. Legendary jazz composers Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk were honored only with posthumous citations in 1999 and 2006, respectively. In 2004, Pulitzer administrators decided to expand the criteria for the music prize, encouraging a broader range of music that included jazz, musical theater and movies.

Coleman, who grew up poor in a largely segregated Fort Worth, Texas, didn't first believe his cousin when he told Coleman that he had won the Pulitzer. He spoke by phone to The Associated Press from his New York City home minutes after hearing the news, and reflected on his long, unlikely journey. "I'm grateful to know that America is really a fantastic country," said the jazz legend, recalling when he first asked his mother for a saxophone. "And here I am." What began for Coleman as a fascination for the bebop of Charlie Parker, led him on a path to discover -- through music -- what he calls "the culture of life and intelligence." On "Sound Grammar," which was recorded at a 2005 concert in Ludwigshafen, Germany, Coleman also plays trumpet and violin. He was awarded a Grammy lifetime achievement award in February. "Of all the languages that human beings are speaking on the planet, it's some form of grammar," Coleman said of his album. "For me, playing music is analyzing grammar." Though Coleman can speak of large, heady ideas in a way not dissimilar from his often conceptual music, he said he has never wanted to be inaccessible. "I've been doing what I think I'm trying to achieve ever since I was teenager and I was only doing it because of the quality of human beings," Coleman said. "I've never really thought about being smart; I've only really thought about being good." Some members of the Pulitzer board such as Jay Harris, a professor at the University of Southern California, have said the Pulitzers have "effectively excluded some of the best of American music" by concentrating fully on classical works. Coleman's win suggests that may be changing. When asked whether he hopes more jazz musicians will follow him in winning Pulitzers, Coleman replied, "I would like to help them if I could." On the Net: http://www.pulitzer.org

http://bricartsmedia.org/events/celebrate-ornette-the-music-of-ornette-coleman-featuring-denardo-coleman-vibe

Celebrate Ornette: The Music Of Ornette Coleman Featuring Denardo Coleman Vibe

June 12, 2014 · 7:00 PM

CELEBRATE BROOKLYN! @ Prospect Park Bandshell

FREE

Doors open at 6:00pm.

Presented in partnership with

Friends of Celebrate Brooklyn! Seating & Tent Access

Friends Seating: Front Rows & Tower SeatsFriends Tent: Open

Sponsor Tent: Closed for a Private Event

Ornette Coleman & Denardo Coleman

http://weblog.liberatormagazine.com/2011/06/jacques-derrida-interviews-ornette.html

Jacques Derrida interviews Ornette Coleman: "Sound has a much more democratic relationship to information"

A conversation between French philosopher Jacques Derrida and jazz musician Ornette Coleman, this interview has some echoes of the Esperanza Spaulding conversation, particularly both Spaulding's and Coleman's perception of the relationship between music and voice/language.

"So the comparison between bass and voice I think would be that the melodies that I’m playing on bass, for most listeners, are much more abstract than what I’m singing. We have such an ingrained connection with the human voice, that however I open my mouth and sing, it’s going to have some symbolism or meaning for the listener -- because it’s a voice. The way I breathe, the way I enunciate, even if I’m not singing lyrics, and then when you add lyrics -- okay, so then it’s not abstract at all. I’m actually telling you what I’m talking about, what I’m emoting about. So with the bass, there’s a certain freedom in the abstraction."

-Esperanza Spalding

"I'm trying to express a concept according to which you can translate one thing into another. I think that sound has a much more democratic relationship to information, because you don't need the alphabet to understand music."

-Ornette Coleman

The Other's Language:

Jacques Derrida Interviews Ornette Coleman

23 June 1997

(SOURCE: Jazz Studies Online)

On improvisation

Jacques Derrida: "The very concept of improvisation verges upon reading, since what we often understand by improvisation is the creation of something new, yet something which doesn't exclude the pre-written framework that makes it possible."

Ornette Coleman: "...the idea is that two or three people can have a conversation with sounds, without trying to dominate it or lead it. What I mean is that you have to be .. . intelligent, I suppose that's the word. In improvised music I think the musicians are trying to reassemble an emotional or intellectual puzzle, in any case a puzzle in which the instruments give the tone. It's primarily the piano that has served at all times as the framework in music, but it's no longer indispensable and, in fact, the commercial aspect of music is very uncertain. Commercial music is not necessarily more accessible, but it is limited."

On composing

Ornette Coleman: "If you're playing music that you've already recorded, most musicians think that you're hiring them to keep that music alive. And most musicians don't have as much enthusiasm when they have to play the same things every time. So I prefer to write music that they've never played before..."

"I want to stimulate them instead of asking them simply to accompany me in front of the public. But I find that it's very difficult to do, because the jazz musician is probably the only person for whom the composer is not a very interesting individual, in the sense that he prefers to destroy what the composer writes or says."

On pre-written pieces

Ornette Coleman: "I don't know if it's true for language, but in jazz you can take a very old piece and do another version of it. What's exciting is the memory that you bring to the present. What you're talking about, the form that metamorphoses into other forms, I think it's something healthy, but very rare."

On language

Ornette Coleman: Do you ever ask yourself if the language that you speak now interferes with your actual thoughts? Can a language of origin influence your thoughts?

Jaacques Derrida: It is an enigma for me. I cannot know it. I know that something speaks through me, a language that I don't understand, that I sometimes translate more or less easi¬ly into my "language." I am of course a French intellectual, I teach in French-speak¬ing schools, but I have the impression that something is forcing me to do something for the French language...

Ornette Coleman: But you know, in my case, in the United States, they call the English that blacks speak "ebonics": they can use an expression that means something else than in current English. The black community has always used a signifying language. When I arrived in California, it was the first time that I was in a place [milieu] where a white man wasn't telling me that I couldn't sit somewhere. Someone began to ask me loads of questions, and I just didn't follow, so then I decided to go see a psychiatrist to see if I understood him. And he gave me a prescription for Valium. I took that valium and threw it in the toilet. I didn't always know where I was, so I went to a library and I checked out all the books possible and imaginable on the human brain, I read them all. They said that the brain was only a conversation. They didn't say what about, but this made me understand that the fact of thinking and knowing doesn't only depend on the place of origin. I understand more and more that what we call the human brain, in the sense of knowing and being, is not the same thing as the human brain that makes us what we are." (source / pdf)

Excerpt from a recent interview with Ornette (2008):

Ornette Coleman - "Ramblin'"

Album:

Change of the Century (1960)

Composed by:

Ornette Coleman

Personnel:

Ornette Coleman — alto saxophone

Don Cherry — pocket trumpet

Charlie Haden — bass

Billy Higgins — drums

Interview with Ornette Coleman (Part 2):

Topics: art&Design, jacques derrida, jazz, language, music, ornette coleman, ourFavorites, philosophy, style

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/a-thing-the-existence-of-which-jacques-derrida-interviews-ornette-coleman

A Thing the Existence of Which:

Jacques Derrida Interviews Ornette Coleman

The indispensable online archive UbuWeb offers a wondrous document for download: a 1997 interview of the crucial modern-jazz musician Ornette Coleman by the crucial modern philosopher Jacques Derrida. (The original English text was lost; the document is translated back from a French translation.) They were, as Derrida notes, born in the same year, 1930 (as was the other key figure of philosophico-artistic late modernity, Jean-Luc Godard), and Derrida does a remarkable job of eliciting the substantial connections between their ideas, which come through in surprising ways.

Coleman tells a story of his early days as a professional musician and a lesson he learned about the bitter practicalities of artistic creation:

I was in Texas, I started to play the saxophone and make a living for my family by playing on the radio. One day, I walked into a place that was full of gambling and prostitution, people arguing, and I saw a woman get stabbed—then I thought that I had to get out of there. I told my mother that I didn’t want to play this music anymore because I thought that I was only adding to all that suffering. She replied, “What’s got hold of you, you want somebody to pay you for your soul?”

For Coleman, the rise of bebop, which he considered “an instrumental music that isn’t connected to a certain scene, that can exist in a more normal setting,” was a redemption, but he found the New York milieu uncongenial, even hostile, as well: “Obviously, the state of things from the technological, financial, social and criminal point of view was much worse than when I was in the South.”

Coleman denies any express intention of bringing about social change by way of his music, but, in a fascinating exchange, he evokes the higher philosophical thought that’s implicit in his work—and racial politics, unsurprisingly, are central to his ideas.

JD: Have you felt that the introduction of technology was a violent transformation of your project, or has it been easy? On the other hand, does your New York project on civilizations [the pretext of the interview] have something to do with what they call globalization?

OC: I think that there’s something true in both, it’s because of this that you can ask yourself if there were “primitive white men”: technology only seems to represent the word “white,” not total equality.

JD: You mistrust this concept of globalization, and I believe you are right.

OC: When you take music, the composers who were inventors in western, European culture are maybe a half-dozen. As for technology, the inventors I have most heard talk about it are Indians from Calcutta and Bombay. There are many Indian and Chinese scientists. Their inventions are like inversions of the ideas of European or American inventors, but the word “inventor” has taken on a sense of racial domination that’s more important than invention—which is sad, because it’s the equivalent of a sort of propaganda.

I’m reminded of Edward O. Bland’s film “The Cry of Jazz,” from 1959, in which he presciently contemplates the role that modern jazz (embodied, in the film, by Sun Ra and his band) would play in the civil-rights movement—and the inevitable breakdown in musical form and function that would result. Jazz is, of course, a creation and a reflection of African-American life and politics. In the sixties, modern jazz often converged with black radicalism and sought alternatives to Western culture, and by decade’s end those forms became (as Bland foresaw) styles that lost their radical content to, on the one hand, aestheticism (including an amiable multiculturalism), and, on the other, the more practical forms of exhortation and mobilization that popular music could provide.

Derrida and Coleman have had something of the same experience: both found themselves the fathers of movements, “deconstruction” and “free jazz,” that threatened to swallow up their individual achievements. Derrida, whose anti-systematic work was born in academic institutions that are explicitly based on structured discipleship, became the core of a new system. As for Coleman, the world of jazz changed before his eyes, from a club-based to a recording-based to a concert- and conservatory-based system, and what it is to be a working musician is drastically different from when he got started. He may have added technology to his music (and, from time to time, subtracted it again); he may have recreated a traditional form of transmission by working with his son, Denardo, who is his drummer (and has been since he was a child, in the late sixties) and manager; he may have recorded with joujouka musicians and Asian singers and challenged, with his concept of harmolodics (which he discussed with David Remnick in a Talk of the Town piece from 2000, again delivering his mother’s aphorism), the settled ways of Western music; but Coleman’s brilliant and daring musical inventions somehow, and quickly, opened the doors to an eclectic musical playground that, like modern Hollywood (under the influence of the French New Wave and, in particular, of Godard) both makes room for a surprising range of individual and personal modes of expression and often uses them to repackage familiar and unchallenging material.

Yet, ultimately, it may well be that the very notion of art, as a way of life and of experience, as it has been for millennia, is both more resilient and more intrinsically radical than the ideas with which some (and even some artists) would challenge it. Here’s Coleman, describing to Derrida the personal origins of his most famous composition:

Before becoming known as a musician, when I worked in a big department store, one day, during my lunch break, I came across a gallery where someone had painted a very rich white woman who had absolutely everything that you could desire in life, and she had the most solitary expression in the world. I had never been confronted with such solitude, and when I got back home, I wrote a piece that I called “Lonely Woman.”

The music’s mournful yet ecstatic refraction and recombination of the blues raises its implications of class, race, and gender to something powerfully universal—yet perhaps universal in a new way (an artistic equivalent of a different order of infinity), a way that, in breaking through the limits of the categories that gave rise to it, may well fulfill Coleman’s philosophical vision.

http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/jazz/dornette.htm

Ornette's Permanent Revolution

As originally published in

The Atlantic Monthly

September 1985

by Francis Davis

ALL Hell broke loose when the alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman made his East Coast nightclub debut, at the Five Spot Cafe, in Greenwich Village on November 17, 1959--twenty-five years ago last fall.

The twenty-nine-year-old Coleman arrived in New York having already won the approval of some of the most influential jazz opinion makers of the period. "Ornette Coleman is doing the only really new thing in jazz since the innovations in the mid-forties of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and those of Thelonious Monk," John Lewis, the pianist and musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet, is reported to have said after hearing Coleman in Los Angeles. (Lewis later helped Coleman secure a contract with Atlantic Records.) Coleman's other champions included the critics Nat Hentoff and Martin Williams and the composer Gunther Schuller, all of whom wrote for the magazine Jazz Review. "I honestly believe . . . that what Ornette Coleman is doing on alto will affect the whole character of jazz music profoundly and pervasively," Williams wrote, a month before Coleman opened at the Five Spot.

Not all of Williams's colleagues shared his enthusiasm, once they were given the opportunity to hear Coleman for themselves. In Down Beat, George Hoefer described the reactions of the audience at a special press preview at the Five Spot: "Some walked in and out before they could finish a drink, some sat mesmerized by the sound, others talked constantly to their neighbors at the table or argued with drink in hand at the bar." Many critics, finding Coleman's music strident and incoherent, feared that his influence on jazz would be deleterious. Others doubted that he would exert any influence on jazz at all. Still others, bewildered by Coleman's music and preferring to take a wait-and-see position on its merits, accused Coleman's supporters at Jazz Review of touting Coleman for their own aggrandizement. Musicians--always skeptical of newcomers, and envious of the publicity Coleman was receiving--denounced him even more harshly than critics did. Some questioned his instrumental competence; the outspoken Miles Davis questioned Coleman's sanity.

Internecine squabbling over the merits of historical movements and geographical schools was nothing new in the jazz world. But not since a short-lived vogue for the rather decrepit New Orleans trumpeter Bunk Johnson two decades earlier (and perhaps not even then) had one musician split opinion so cleanly down the middle. Coleman was either a visionary or a charlatan, and there was no middle ground between advocacy and disapproval. The controversy raged, spreading from the music journals to the daily newspapers and general-interest magazines, where it gradually turned comic. Every VIP in Manhattan, from Leonard Bernstein to Dorothy Kilgallen, seemed to have wisdom to offer on the subject of Ornette Coleman. In Thomas Pynchon's novel V. there is a character named McClintic Sphere, who plays an alto saxophone of hand-carved ivory (Coleman's was made of white plastic) at a club called the V Note.

'He plays all the notes Bird missed,' somebody whispered in front of Fu. Fu went silently through the motions of breaking a beer bottle on the edge of the table, jamming it into the speaker's back and twisting.

FOR those of us who began listening to jazz after 1959, it is difficult to believe that Coleman's music was once the source of such animus and widespread debate. Given the low visibility of jazz today, a figure comparable to Coleman arriving on the scene might find himself in the position of shouting "Fire" in an empty theater.

Looking back, it also strains belief that so many of Coleman's fellow musicians initially failed to recognize the suppleness of his phrasing and the keening vox-humana quality of his intonation. Jazz musicians have always respected instrumentalists whose inflections echo the natural cadences of speech, and they have always sworn by the blues (although as jazz has increased in sophistication, "the blues" has come to signify a feeling or a tonal coloring, in addition to a specific form). Coleman's blues authenticity--the legacy of the juke joints in his native Fort Worth, Texas, where he had played as a teenager--should have scored him points instantly. Instead, his ragged, down-home sound seems to have cast him in the role of country cousin to slicker, more urbanized musicians--as embarrassing a reminder of the past to them as a Yiddish speaking relative might have been to a newly assimilated Jew. In 1959 the "old country" for most black musicians was the American South, and few of them wanted any part of it.

What must have bothered musicians still more than the unmistakable southern dialect of Coleman's music was its apparent formlessness, its flouting of rules that most jazz modernists had invested a great deal of time and effort in mastering. In the wake of bebop, jazz had become a music of enormous harmonic complexity. By the late 1950s it seemed to be in danger of becoming a playground for virtuosos, as the once liberating practice of running the chords became routine. If some great players sounded at times as though they lacked commitment and were simply going through the motions, it was because the motions were what they had become most committed to.

In one sense, the alternative that Coleman proposed amounted to nothing more drastic than a necessary (and, in retrospect, inevitable) suppression of harmony in favor of melody and rhythm--but that was regarded as heresy in 1959. It has often been said that Coleman dispensed with recurring chord patterns altogether, in both his playing and his writing. The comment is not entirely accurate, however. Rather, he regarded a chord sequence as just one of many options for advancing a solo. Coleman might improvise from chords or, as inspiration moved him, he might instead use as his point of departure "a mood, fragments of melody, an area of pitch, or rhythmic patterns," to quote the critic Martin Williams. Moreover, Coleman's decision to dispense with a chordal road map also permitted him rhythmic trespass across bar lines. The stealthy rubato of Coleman's phrases and his sudden accelerations of tempo implied liberation from strict meter, much as his penchant for hitting notes a quarter-tone sharp or flat and his refusal to harmonize his saxophone with Don Cherry's trumpet during group passages implied escape from the well-tempered scale.

Ultimately, rhythm may be the area in which Coleman has made his most significant contributions to jazz. Perhaps the trick of listening to his performances lies in an ability to hear rhythm as melody, the way he seems to do, and the way early jazz musicians did. Some of Coleman's comeliest phrases, like some of King Oliver's or Sidney Bechet's, sound as though they were scooped off a drumhead.

Coleman was hardly the only jazz musician to challenge chordal hegemony in 1959. John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, and Thelonious Monk, among others, were looking beyond Charlie Parker's harmonic discoveries to some of the rhythmic and structural implications of bop. Cecil Taylor and George Russell were experimenting with chromaticism and pantonality, and a Miles Davis Sextet featuring Coltrane and Bill Evans had just recorded Kind of Blue, an album that introduced a new spaciousness to jazz by replacing chords with modes and scales. But it was Coleman who was making the cleanest break with convention, and Coleman whose intuitive vision of the future bore the most natural relationship to the music's country origins. He was a godsend, as it turned out.

IN 1959 Coleman's music truly represented Something Else (to quote the title of his first album). Whether it also forecast The Shape of Jazz to Come (the title of another early album of Coleman's) is still problematical. Certainly Coleman's impact on jazz was immediate and it has proved long-lasting. Within a few years of Coleman's first New York engagement established saxophonists like Coltrane, Rollins, and Jackie McLean were playing a modified Colemanesque free form, often in the company of former Coleman sidemen. The iconoclastic bassist Charles Mingus (initially one of Coleman's antagonists) was leading a pianoless quartet featuring the alto saxophonist Eric Dolphy and the trumpeter Ted Curson, whose open-ended dialogues rivaled in abandon those of Coleman and Cherry.

Over the years Coleman has continued to cast a long shadow, as he has extended his reach to symphonies, string quartets, and experiments in funk. By now he has attracted two generations of disciples.

There are the original sidemen in his quartet and their eventual replacements: the trumpeters Cherry and Bobby Bradford; the tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman; the bassists Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, Jimmy Garrison, and David Izenzon; and the drummers Billy Higgins, Ed Blackwell, and Charles Moffett. These musicians were followed in the late 1970s by younger ones who brought to Coleman's bands the high voltage of rock and funk: for example, the guitarist James Blood Ulmer, the electric bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma, and the drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. Some of Coleman's early associates in Texas and California, such as the clarinetist John Carter and the flutist Prince Lawsha, have gone on to produce work that shows Coleman's influence unmistakably.

Coleman planted the seed for the free jazz movement of the 1960s, which in turn gave rise to a school of European themeless improvisors, led by the guitarist Derek Bailey and the saxophonist Evan Parker. Since 1965 Coleman has performed on trumpet and violin in addition to alto and tenor saxophones, and several young violinists have taken him as their model: for example, Billy Bang, whose jaunty, anthemlike writing bespeaks his affection for Coleman. And for all practical purposes, the idea of collective group improvisation, which has reached an apex in the work of a number of groups affiliated with the Chicago-based Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, began with the partial liberation of bass and drums from chordal and timekeeping duties in the first Ornette Coleman Quartet.

IF one listens closely for them, one can hear Colemanesque accents in the most unlikely places: the maundering piano soliloquies of Keith Jarrett and the bickering, simultaneous improvisations of young hard-boppers like Wynton and Branford Marsalis. Yet for all that, Coleman's way has never really supplanted Charlie Parker's as the lingua franca to jazz, as many hoped and others feared it would.

One reason could be that Coleman's low visibility has denied the jazz avant-garde a figurehead. Since his debut at the Five Spot, Coleman has set a price for concerts and recordings that reflects what he perceives to be his artistic merit rather than his limited commercial appeal. Needless to say, he has had very few takers. As a result, he performs only occasionally, and it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that he bears some responsibility for his own neglect.

Just a few years ago it appeared that Coleman's star was on the rise again. In 1977 his former sidemen Cherry, Redman, Haden, and Blackwell formed a quartet called Old and New Dreams. Coleman compositions, old and new, accounted for roughly half of the group's repertoire. If the myth that Coleman had to be physically present in order for his music to be played properly persisted in some quarters, Old and New Dreams dispelled it once and for all. The band played Coleman's music with a joy and a sense of purpose that bore witness to Coleman's acuity as a composer. The success of Old and New Dreams showed that the music that had once been both hailed and reviled as the wave of the future had taken a firm enough hold in the past to inspire nostalgia.

The rapture with which jazz audiences greeted the band's reinterpretation of vintage Coleman owed something to the fact that Coleman himself had moved on to other frontiers--appearing with two electric guitarists, two bass guitarists, and two drummers in a band he called Prime Time. The group provided the working model for a cryptic (and, one suspects, largely after-the-fact) theory of tonality that Coleman called harmolodics. The theory held that instruments can play together in different keys without becoming tuneless or exchanging the heat of the blues for a frigid atonality. (As the critic Robert Palmer pointed out in the magazine The New York Rocker, Coleman's music had always been "harmolodic.") In practice the harmolodic theory functioned like a MacGuffin in a Hitchcock film: if you could follow what it was all about, good for you; if you couldn't, that wasn't going to hamper your enjoyment one iota. What mattered more than any amount of theorizing was that Coleman was leading jazz out of a stalemate, much as he had in 1959. He had succeeded in locating indigenous jazz rhythms that play upon the reflexes of the body the way the simultaneously bracing and relaxing polyrhythms of funk and New Wave rock-and-roll do.

Unlike most of the jazz musicians who embraced dance rhythms in the 1970s, Coleman wasn't slumming or taking the path of least resistance in search of a mass following. Nonetheless, a modest commercial breakthrough seemed imminent in 1981, when he signed with Island Records and named Sid and Stanley Bernstein (the former is the promoter who brought the Beatles to Shea Stadium) as his managers. There is some disagreement among the principal parties about what happened next, but Coleman released only one album on the Island label. In 1983 he severed his ties with the Bernstein agency and once more went into a partial eclipse.

Lately the task of shedding Coleman's light has fallen to Ulmer, Tacuma, and Jackson. They have been no more successful than Coleman in attracting a mass audience, despite a greater willingness to accommodate public tastes--and despite reams of hype from the intellectual wing of the pop-music press. When Coleman next emerges from the shadows, he may have discarded harmolodics in favor of some other invention.

IN the final analysis, Coleman's failure to redefine jazz as decisively as many predicted he would is more the result of the accelerated pace at which jazz was evolving before he arrived in New York than of his lack of activity afterward. During the fifty years prior to Coleman's debut a series of upheavals had taken jazz far from its humble folk beginnings and made of it a codified art music. It was as though jazz had imitated the evolution of European concert music in a fraction of the time. Just as the term "classical music" has come to signify European concert music of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the words "modern jazz" have become synonymous with the style of jazz originally called bebop.

With Ornette Coleman, jazz established its permanent avant-garde--a "new" that would always remain new. If one measures a player's influence solely by the number of imitators he spawns and veteran players who adopt aspects of his style (the usual yardstick in jazz), Coleman finishes among his contemporaries a distant third behind Davis and Coltrane. Yet his accomplishment seems somehow greater than theirs. Davis and Coltrane showed which elements of free form the jazz mainstream could absorb (modality, approximate harmonies, saxophone glossolalia, the sixteenth note as a basic unit of measurement, the use of auxiliary percussion and of horns once considered "exotic") and which elements it finally could not (variable pitch, free meter, collective improvisation). Coleman's early biography is replete with stories of musicians packing up their instruments and leaving the bandstand when he tried to sit in. If Coleman now showed up incognito at a jam session presided over by younger followers of Parker, Davis, and Coltrane, chances are he would be given the cold shoulder. Bebop seems to be invincible, though Coleman and other prophets without honor continue to challenge its hegemony.

The bop revolution of the 1940s was a successful coup d'etat. The revolution that Ornette Coleman started is never wholly going to succeed or fail. Coleman's revolution has proved to be permanent. Its skirmishes have marked the emergence of jazz as a full-fledged modern art, with all of modernism's dualities and contradictions.

NO modern jazz record library is complete without the albums that Ornette Coleman recorded for Atlantic Records from 1959 to 1961, including The Shape of Jazz to Come (SD1317), Change of the Century (SD1327), This Is Our Music (SD1353),Free Jazz (SD1364), Ornette! (SD1378), and Ornette on Tenor (SD1394). Although most of them remain in print, the question arises why Atlantic has never re-issued its Coleman material in chronological order, complete with unissued titles and alternate takes. This seminal music merits such historical presentation.

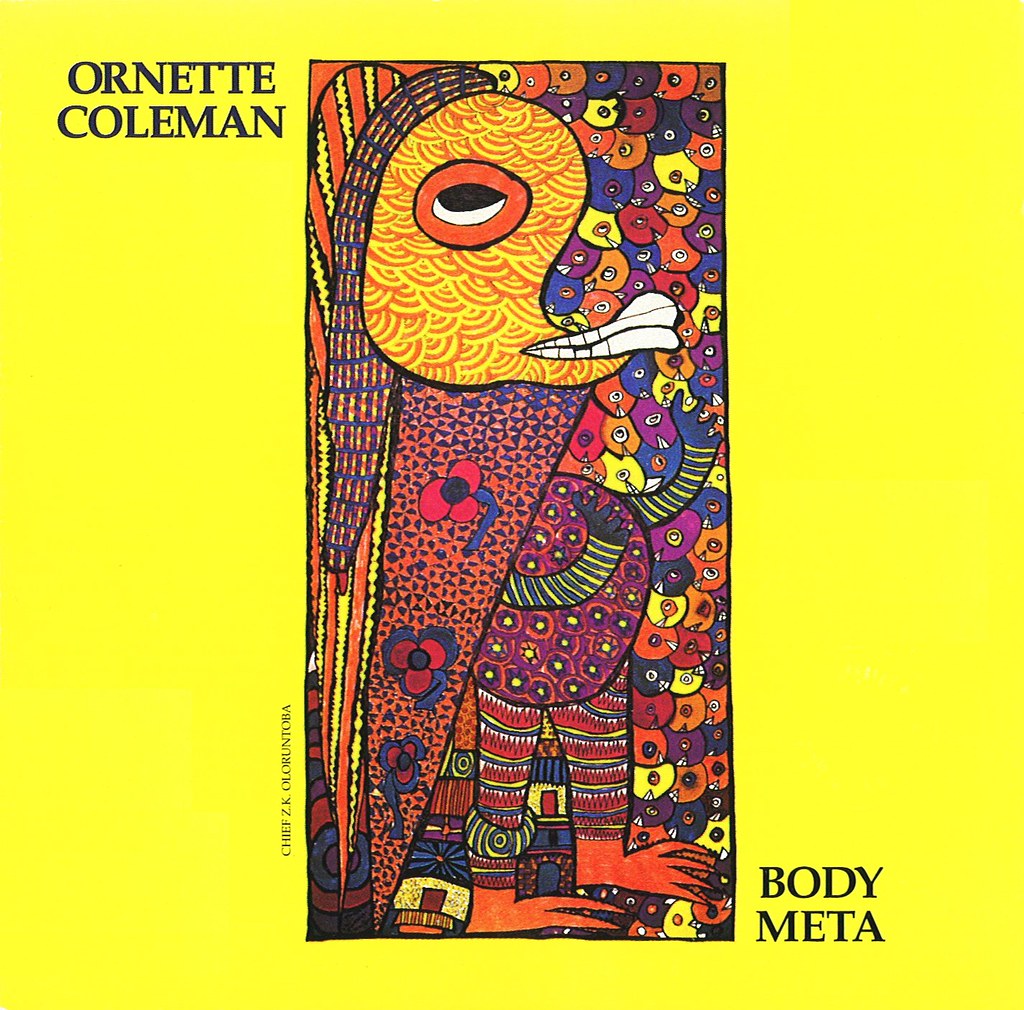

Coleman's recordings with Prime Time and its immediate precursors are Dancing in Your Head (A&M Horizon SP722), Body Mehta (Artists House AH-1), and Of Human Feelings (Island/ Antilles AN-2001). The group Old and New Dreams, which still exists as a part-time endeavor, has released three albums, including Playing (ECM-11205) and two titled Old and New Dreams on different labels (ECM-1-1154 and Black Saint BSR-0013).

Other essential Coleman includes his album-length concerto for alto saxophone and orchestra, The Skies of America (Columbia KC-31562); his duets with the bassist Charlie Haden, Soap Suds (Artist House AH-6); and his best concert recordings, The Ornette Coleman Trio Live at the Golden Circle, Volumes 1 & 2 (Blue Note BST-84224 and BST-84225, available separately).

Copyright © 1985 by Francis Davis. All rights reserved.

The Atlantic Monthly; September 1985; "Ornette's Permanent Revolution"; Volume 257, No. 3; pages 99-102.

MUSIC | MUSIC REVIEW

The Honoree Wanted to Play, Too

An Ornette Coleman Tribute at Celebrate Brooklyn!

By BEN RATLIFF

JUNE 13, 2014

New York Times

Celebrate Ornette Ornette Coleman not only received praise but also played his alto saxophone at this tribute concert at the Prospect Park Bandshell on Thursday. Credit Christopher Gregory for The New York Times

The evening’s honoree on Thursday at the Prospect Park Bandshell in Brooklyn was Ornette Coleman, and the first to pay respects was Sonny Rollins, wearing a stylish black raincoat.

“I’m going to say something that Ornette already said to me: It’s all good,” Mr. Rollins declared. “Don’t worry about anything. We might not see it right now, but it’s all good.”

Mr. Coleman appeared next, in a purple silk suit, walking slowly, with assistance, and wiping tears. Borough President Eric Adams of Brooklyn read an official proclamation, and Mr. Coleman followed with his own.

“There’s nothing else but life,” he said. “We can’t be against each other. We have to help each other. It’ll turn out like you will never forget it.”

Mr. Rollins didn’t play, but Mr. Coleman — now 84 — and about two dozen others did, some of them from well outside of jazz per se, tracing a wide circle of his influence. Since the 1950s, Mr. Coleman has had musical particulars: a light and talky saxophone sound, an original gift of melody, a generous collective-improvisation philosophy. But in larger terms, he is often understood as something bigger, a kind of cultural liberator.

“Celebrate Ornette,” presented by both BRIC’s Celebrate Brooklyn! Series and the Blue Note Jazz Festival, wasn’t connected to a milestone birthday or a record or seemingly anything else, but to the premise that it is right to fuss over people like Mr. Coleman, in his presence, while the opportunity remains.

Again, Mr. Coleman played: a significant fact and an increasingly rare occasion in the last several years. This was billed as a concert for him, not by him; it was not clear whether he would play a note until showtime. But he sat in a chair onstage for most of the concert’s first half, either with an alto saxophone in his lap, or taking part as if he were playing along with nature, joining when he wanted to and how he wanted to.

The concert was organized by Mr. Coleman’s son, Denardo, who was also the bandleader, as a program of Coleman compositions, except for a couple of free improvisations. But Mr. Coleman wasn’t there to play Ornette Coleman compositions. He was just there to play, and he started from soft and lovely unaccompanied lines, like some precursor to blues language.

When the band started one of his actual tunes — “Ramblin’,” swinging and medium tempo — he kept playing his own long, slow, high, regal phrases, not in the same key or rhythm as the song; but he was the source of it all, and since we can’t be against each other, why not? This is the power in Mr. Coleman’s music: He wills it to make sense, and generally it does.

Musicians paying tribute to the jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman in Prospect Park included members of the Master Musicians of Joujouka. Credit Christopher Gregory for The New York Times

The core band was all regulars from his various ensembles since the 1970s: Denardo Coleman on drums, Charles Ellerbee on guitar, Al MacDowell on an electric piccolo bass and Tony Falanga on acoustic bass. But there were many others: Flea, the bassist from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who hung in there with “Blues Connotation” and “Turnaround”; Henry Threadgill, David Murray and Antoine Roney, playing the themes and individual saxophone solos in those songs; the dancer Savion Glover, tapping on an amplified stage during “Ramblin’ ” and continuing through a song instigated by a few abstract phrases of Mr. Coleman’s, which became another version of “Turnaround.”

That song became a slow, stomping big-city blues and a wild, noisy jam. Denardo Coleman — loud, enthusiastic, abrupt, unusual by the measure of most contexts outside of this one — practiced his warpings and surges of tempo with his sticks and pedals, and Mr. Glover with his feet. Here was the nexus of music understood as casual, join-along generosity, and as a historical moment, to be guarded and protected. Near me was a small girl, about 3, shaking a rattle to the music, in a legit response to what she heard, and a long-bearded fan who appeared to be at least 20 times her age, glaring as if she were destroying a library.

Bill Laswell Credit Christopher Gregory for The New York Times

The band expanded again for “The Sphinx,” with the pianist Geri Allen, who played brilliantly — polytonal, energetic, organized — and her son, Wallace Roney Jr., on trumpet, as an extra voice in the horn lines. Patti Smith read and sang her own poems inspired by the idea of Mr. Coleman’s being encouraged as a boy by his parents; she was supported by her own band, with Mr. Coleman still onstage to her right, smiling.

In the second half, with Mr. Coleman not onstage, Laurie Anderson performed violin drones in a trio with John Zorn on alto saxophone and Bill Laswell on electric bass. The performance was partly in memory of her husband, Lou Reed, who died in October and loved Mr. Coleman’s music. Branford Marsalis played tenor saxophone in a duet with Bruce Hornsby on piano.

Nels Cline and Thurston Moore enacted a two-guitar improvisation, Mr. Moore’s generalized chords and textures against Mr. Cline’s thick, pinpoint melodies. The saxophonist Ravi Coltrane and the guitarist James Blood Ulmer joined the band for a rocky stretch, with weird implosions of tempo and harmony. And two members of the Master Musicians of Joujouka — the Moroccan musicians with whom Mr. Coleman recorded in 1973 — brought their double-reed instruments to the ensemble for a version of “Theme From a Symphony,” from Mr. Coleman’s 1977 album, “Dancing in Your Head.”

The finale was “Lonely Woman,” Mr. Coleman’s most recognizable song and one of his most unusual, a minor-key ballad in a corpus of general happiness.

These kinds of concerts can be a mess, but this, finally, wasn’t. It cohered with the love of Mr. Coleman’s admirers, the intuitive logic and joy of his music, and his own presence.

Listening With Ornette Coleman

Seeking the Mystical Inside the Music

Lee Friedlander for The New York Times. September 22, 2006

Ornette Coleman in his apartment in Manhattan. At 76, he remains busy; “Sound Grammar” is the name of both his new album and his new record label. | ||||

Related

Readers’ Opinions

In any case, other people’s music was what I wanted to talk to him about. I asked what he would like to listen to. “Anything you want,” he said in his fluty Southern voice. “There is no bad music, only bad performances.” He finally offered a few suggestions. The music he likes is simply defined: anything that can’t be summed up in a common term. Any music that is not created as part of a style. “The state of surviving in music is more like ‘what music are you playing,’ ” he said. “But music isn’t a style, it’s an idea. The idea of music, without it being a style — I don’t hear that much anymore.”

Then he went up a level. “I would like to have the same concept of ideas as how people believe in God,” he said. “To me, an idea doesn’t have any master.”

Mr. Coleman was born, in 1930, and raised in Fort Worth, where he attained some skill at playing rhythm and blues in bars, like any decent saxophonist, and some more skill at playing bebop, which was rarer. He arrived in New York in 1959, via Los Angeles, with an original, logical sense of melody and an idea of playing with no preconceived chord changes. Yet his music bore a tight sense of knowing itself, of natural form, and the records he made for Atlantic with his various quartets, from 1959 to 1961, are almost unreasonably beautiful.

Following that initial shock of the new came a short period with a trio, then a two-year hiatus from recording in 1963 and 1964, then the trio again, then a fantastic quartet from 1968 to 1972 with the tenor saxophonist Dewey Redman (who died three weeks ago), then a period of funk-through-the-looking-glass with his electric band, Prime Time. Mr. Coleman is still moving, now with a band including two bassists, Greg Cohen and Tony Falanga, and his son, Denardo Coleman, on drums.

He has a kind of high-end generosity; he said that he wouldn’t think twice about letting me go home with a piece of music he had just written, because he would be interested in what I might make of it. But there is a great pessimism in his talk, too. He said he believes that most of human history has been wasted on building increasingly complicated class structures. “Life is already complete,” he said. “You can’t learn what life is. And the only way you die is if something kills you. So if life and death are already understood, what are we doing?”

A week later we met for several hours at his large, minimal-modernist loft in Manhattan’s garment district. Mr. Coleman is 76 and working often: he is making music with his new quartet that, at heart, is similar to what he made when he was 30. On “Sound Grammar,” his new live album (on his new record label, of the same name), it is a matter of lines traveling together and pulling apart, following the curve of his melodies, tangling and playing in a unison that allows for discrepancies between individual sound and intonation and, sometimes, key.

Unison is one of his key words: he puts an almost mystical significance in it, and he uses it in many ways. “Being a human, you’re required to be in unison: upright,” he said.

Mr. Coleman draws you into the chicken-and-egg questions that he’s asking himself. These questions can become sort of the dark side of Bible class. Many of them are about what happens when you put a name on something, or when you learn some codified knowledge.

Though he is fascinated by music theory, he is suspicious of any construct of thought. Standard Western notation and harmony is a big problem for him, particularly for the fact that the notation for many instruments (including his three instruments — alto saxophone, trumpet and violin) must be transposed to fit the “concert key” of C in Western music.

Mr. Coleman talks about “music” with care and accuracy, but about “sound” with love. He doesn’t understand, he says, how listeners will ever properly understand the power of notes when they are bossed around by the common Western system of harmony and tuning.

He’s not endorsing cacophony: he says making music is a matter of finding euphonious resolutions between different players. (And much of his music keeps referring to, if not actually staying in, a major key.) But the reason he appreciates Louis Armstrong, for example, is that he sees Armstrong as someone who improvised in a realm beyond his own knowledge. “I never heard him play a straight chord in root position for his idea,” he said. “And when he played a high note, it was the finale. It wasn’t just because it was high. In some way, he was telling stories more than improvising.”

MR. COLEMAN’S first request was something by Josef Rosenblatt, the Ukrainian-born cantor who moved to New York in 1911 and became one of the city’s most popular entertainers — as well as a symbol for not selling out your convictions. (He turned down a position with a Chicago opera company, but was persuaded to take a small role in Al Jolson’s film “The Jazz Singer.”) I brought some recordings from 1916 and we listened to “Tikanto Shabbos,” a song from Sabbath services. Rosenblatt’s voice came booming out, strong and clear at the bottom, with miraculous coloratura runs at the top.

“I was once in Chicago, about 20-some years ago,” Mr. Coleman said. “A young man said, ‘I’d like you to come by so I can play something for you.’ I went down to his basement and he put on Josef Rosenblatt, and I started crying like a baby. The record he had was crying, singing and praying, all in the same breath. I said, wait a minute. You can’t find those notes. Those are not ‘notes.’ They don’t exist.”

He listened some more. Rosenblatt was working with text, singing brilliant figures with it, then coming down on a resolving note, which was confirmed and stabilized by a pianist’s chord. “I want to ask something,” he said. “Is the language he’s singing making the resolution? Not the melody. I mean, he’s resolving. He’s not singing a ‘melody.’ ”

It could be that he’s at least singing each little section in relation to a mode, I said.

“I think he’s singing pure spiritual,” he said. “He’s making the sound of what he’s experiencing as a human being, turning it into the quality of his voice, and what he’s singing to is what he’s singing about. We hear it as ‘how he’s singing.’ But he’s singing about something. I don’t know what it is, but it’s bad.”

I wonder how much of it is really improvised, I said. Which up-and-down melodic shapes, and in which orders, were well practiced, and which weren’t.

“Mm-hmm,” he said. “I understand what you’re saying. But it doesn’t sound like it’s going up and down; it sounds like it’s going out. Which means it’s coming from his soul.”

MR. COLEMAN grew up loving Charlie Parker and bebop in general. “It was the most advanced collective way of playing a melody and at the same time improvising on it,” he said. Certainly, he was highly influenced by Parker’s phrasing.

He saw Parker play in Los Angeles in the early 1950’s. “Basically, he had picked up a local rhythm section, and he was playing mostly standards. He didn’t play any of the music that I liked that I’d heard on a record. He looked at his watch and stopped in the middle of what he was playing, put his horn in his case and walked out the door. I said, ohh. I mean, I was trying to figure out what that had to do with music, you know? It taught me something.”

What did it teach him? “He knew the quality of what he could play, and he knew the audience, and he wasn’t impressed enough by the audience to do something that they didn’t know. He wasn’t going to spend any more time trying to prove that.”

We listened to “Cheryl,” a Parker quintet track from 1947. “I was drawn to the way Charlie Parker phrased his ideas,” he said. “It sounded more like he was composing, and I really loved that. Then, when I found out that the minor seventh and the major seventh was the structure of bebop music — well, it’s a sequence. It’s the art of sequences. I kind of felt, like, I got to get out of this.”

He talks a lot about sequences. (John Coltrane, he said, was a good saxophone player who was lost to them.) With regard to his Parker worship, he kept the phrasing but got rid of the sequences. “I first tried to ban all chords,” he said, “and just make music an idea, instead of a set pattern to know where you are.”

I SUGGESTED gospel music, and he was enthusiastic. I brought something I felt he might like: sacred harp music — white, rural, choral music, about 100 voices in loose unison. We listened to “The Last Words of Copernicus,” written in 1869 and recorded by Alan Lomax in Fyffe, Ala., in 1959.

“That’s breath music,” he said, as big groups of singers harmonized in straight eighth-note patterns, singing plainly but with character. “They’re changing the sound with their emotions. Not because they’re hearing something.” But then we were off on another topic — whether a singer should seek a voicelike sound for his voice. “Isn’t it amazing that sound causes the idea to sound the way it is, more than the idea?” he asked.

Finally the listening experiment broke down. It’s hard to keep Mr. Coleman talking about anyone else’s music. His mystical-logical puzzles are too interesting to him.

He is writing new pieces for each concert, and was leaving for European shows. “Right now, I’m trying to play the instrument,” he said, “and I’m trying to write, without any restrictions of chord, keys, time, melody and harmony, but to resolve the idea eternally, where every person receives the same quality from it, without relating it to some person.”

He told a childhood story about his mother, who, he kept reminding me, was born on Christmas Day. After he received his first saxophone, he would go to her when he learned to play something by ear. “I’d be saying: ‘Listen to this! Listen to this!’ ” he remembered. “You know what she’d tell me? ‘Junior, I know who you are. You don’t have to tell me.’ ”

Correction: Oct. 3, 2006

An article in Weekend on Sept. 22 about the jazz musician Ornette Coleman erroneously included an instrument among those for which notation must be transposed to fit the “concert key” of C in Western music. They do not include the violin.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/14/arts/music/an-ornette-coleman-tribute-at-celebrate-brooklyn.html

An Ornette Coleman Tribute at Celebrate Brooklyn!

Celebrate Ornette Ornette Coleman not only received praise but also played his alto saxophone at this tribute concert at the Prospect Park Bandshell on Thursday. Credit Christopher Gregory for The New York Times

The evening’s honoree on Thursday at the Prospect Park Bandshell in Brooklyn was Ornette Coleman, and the first to pay respects was Sonny Rollins, wearing a stylish black raincoat.

“I’m going to say something that Ornette already said to me: It’s all good,” Mr. Rollins declared. “Don’t worry about anything. We might not see it right now, but it’s all good.”

Mr. Coleman appeared next, in a purple silk suit, walking slowly, with assistance, and wiping tears. Borough President Eric Adams of Brooklyn read an official proclamation, and Mr. Coleman followed with his own.

“There’s nothing else but life,” he said. “We can’t be against each other. We have to help each other. It’ll turn out like you will never forget it.”

Mr. Rollins didn’t play, but Mr. Coleman — now 84 — and about two dozen others did, some of them from well outside of jazz per se, tracing a wide circle of his influence. Since the 1950s, Mr. Coleman has had musical particulars: a light and talky saxophone sound, an original gift of melody, a generous collective-improvisation philosophy. But in larger terms, he is often understood as something bigger, a kind of cultural liberator.

“Celebrate Ornette,” presented by both BRIC’s Celebrate Brooklyn! Series and the Blue Note Jazz Festival, wasn’t connected to a milestone birthday or a record or seemingly anything else, but to the premise that it is right to fuss over people like Mr. Coleman, in his presence, while the opportunity remains.