SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LAURA MVULA

October 10-16

DIZZY GILLESPIE

October 17-23

LESTER YOUNG

October 24-30

TIA FULLER

October 31-November 6

ROSCOE MITCHELL

November 7-13

MAX ROACH

November 14-20

DINAH WASHINGTON

November 21-27

BUDDY GUY

November 28-December 4

JOE HENDERSON

December 5-11

HENRY THREADGILL

December 12-18

MUDDY WATERS

December 19-25

B.B. KING

December 26-January 1

http://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/maxroach

MAX ROACH

Primary Instrument: Drums

Born: January 10, 1925 | Died: August 16, 2007

Maxwell Lemuel Roach is a percussionist, drummer, and jazz composer. He has worked with many of the greatest jazz musicians, including Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Sonny Rollins. He is widely considered to be one of the most important drummers in the history of jazz.

Roach was born in Newland, North Carolina, to Alphonse and Cressie Roach; his family moved to Brooklyn, New York when he was 4 years old. He grew up in a musical context, his mother being a gospel singer, and he started to play bugle in parade orchestras at a young age. At the age of 10, he was already playing drums in some gospel bands. He performed his first big-time gig in New York City at the age of sixteen, substituting for Sonny Greer in a performance with the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

In 1942, Roach started to go out in the jazz clubs of the 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom (playing with schoolmate Cecil Payne). He was one of the first drummers (along with Kenny Clarke) to play in the bebop style, and performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis.

Roach played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy 1945 session, a turning point in recorded jazz.

Two children, son Daryl and daughter Maxine, were born from his first marriage with Mildred Roach. In 1954 he met singer Barbara Jai (Johnson) and had another son, Raoul Jordu.

He continued to play as a freelance while studying composition at the Manhattan School of Music. He graduated in 1952.

During the period 1962-1970, Roach was married to the singer Abbey Lincoln, who had performed on several of Roach's albums. Twin daughters, Ayodele and Dara Rasheeda, were later born to Roach and his third wife, Janus Adams Roach.

Long involved in jazz education, in 1972 he joined the faculty of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

In the early 2000s, Roach became less active owing to the onset of hydrocephalus-related complications.

Renowned all throughout his performing life, Roach has won an extraordinary array of honors. He was one of the first to be given a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, cited as a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in France, twice awarded the French Grand Prix du Disque, elected to the International Percussive Society's Hall of Fame and the Downbeat Magazine Hall of Fame, awarded Harvard Jazz Master, celebrated by Aaron Davis Hall, given eight honorary doctorate degrees, including degrees awarded by the University of Bologna, Italy and Columbia University.

In 1952 Roach co-founded Debut Records with bassist Charles Mingus. This label released a record of a concert, billed and widely considered as “the greatest concert ever,” called Jazz at Massey Hall, featuring Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Mingus and Roach. Also released on this label was the groundbreaking bass-and- drum free improvisation, Percussion Discussion.

In 1954, he formed a quintet featuring trumpeter Clifford Brown, tenor saxophonist Harold Land, pianist Richie Powell (brother of Bud Powell), and bassist George Morrow, though Land left the following year and Sonny Rollins replaced him. The group was a prime example of the hard bop style also played by Art Blakey and Horace Silver. Tragically, this group was to be short-lived; Brown and Powell were killed in a car accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in June 1956. After Brown and Powell's deaths, Roach continued leading a similarly configured group, with Kenny Dorham (and later the short-lived Booker Little) on trumpet, George Coleman on tenor and pianist Ray Bryant. Roach expanded the standard form of hard-bop using 3/4 waltz rhythms and modality in 1957 with his album Jazz in 3/4 time. During this period, Roach recorded a series of other albums for the EmArcy label featuring the brothers Stanley and Tommy Turrentine.

In 1960 he composed the “We Insist! - Freedom Now” suite with lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., after being invited to contribute to commemorations of the hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. Using his musical abilities to comment on the African-American experience would be a significant part of his career. Unfortunately, Roach suffered from being blacklisted by the American recording industry for a period in the 1960s. In 1966 with his album Drums Unlimited (which includes several tracks that are entirely drums solos) he proved that drums can be a solo instrument able to play theme, variations, rhythmically cohesive phrases. He described his approach to music as “the creation of organized sound.”

Among the many important records Roach has made is the classic Money Jungle 1962, with Mingus and Duke Ellington. This is generally regarded as one of the very finest trio albums ever made.

During the 70s, Roach formed a unique musical organization--”M'Boom”--a percussion orchestra. Each member of this unit composed for it and performed on many percussion instruments. Personnel included Fred King, Joe Chambers, Warren Smith, Freddie Waits, Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, Francisco Mora, and Eli Fountain.

Not content to expand on the musical territory he had already become known for, Roach spent the decades of the 80s and 90s continually finding new ways to express his musical expression and presentation.

In the early 80s, he began presenting entire concerts solo, proving that this multi-percussion instrument, in the hands of such a great master, could fulfill the demands of solo performance and be entirely satisfying to an audience. He created memorable compositions in these solo concerts; a solo record was released by Bay State, a Japanese label, just about impossible to obtain. One of these solo concerts is available on video, which also includes a filming of a recording date for Chattahoochee Red, featuring his working quartet, Odean Pope, Cecil Bridgewater and Calvin Hill.

He embarked on a series of duet recordings. Departing from the style of presentation he was best known for, most of the music on these recordings is free improvisation, created with the avant-garde musicians Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, Archie Shepp, Abdullah Ibrahim and Connie Crothers. He created duets with other performers: a recorded duet with the oration by Martin Luther King, “I Have a Dream”; a duet with video artist Kit Fitzgerald, who improvised video imagery while Roach spontaneously created the music; a classic duet with his life-long friend and associate Dizzy Gillespie; a duet concert recording with Mal Waldron.

He wrote music for theater, such as plays written by Sam Shepard, presented at La Mama E.T.C. in New York City.

He found new contexts for presentation, creating unique musical ensembles. One of these groups was “The Double Quartet.” It featured his regular performing quartet, with personnel as above, except Tyrone Brown replacing Hill; this quartet joined with “The Uptown String Quartet,” led by his daughter Maxine Roach, featuring Diane Monroe, Lesa Terry and Eileen Folson.

Another ensemble was the “So What Brass Quintet,” a group comprised of five brass instrumentalists and Roach, no chordal instrumnent, no bass player. Much of the performance consisted of drums and horn duets. The ensemble consisted of two trumpets, trombone, French horn and tuba. Musicians included Cecil Bridgewater, Frank Gordon, Eddie Henderson, Steve Turre, Delfeayo Marsalis, Robert Stewart, Tony Underwood, Marshall Sealy, and Mark Taylor.

Roach presented his music with orchestras and gospel choruses. He performed a concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He wrote for and performed with the Walter White gospel choir and the John Motley Singers. Roach performed with dancers: the Alvin Aily Dance Company, the Dianne McIntyre Dance Company, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company.

In the early 80s, Roach surprised his fans by performing in a hip hop concert, featuring the artist-rapper Fab Five Freddy and the New York Break Dancers. He expressed the insight that there was a strong kinship between the outpouring of expression of these young black artists and the art he had pursued all his life.

During all these years, while he ventured into new territory during a lifetime of innovation, he kept his contact with his musical point of origin. His last recording, “Friendship”, was with trumpet master Clark Terry, the two long-standing friends in duet and quartet.

MAX ROACH

Primary Instrument: Drums

Born: January 10, 1925 | Died: August 16, 2007

Maxwell Lemuel Roach is a percussionist, drummer, and jazz composer. He has worked with many of the greatest jazz musicians, including Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Sonny Rollins. He is widely considered to be one of the most important drummers in the history of jazz.

Roach was born in Newland, North Carolina, to Alphonse and Cressie Roach; his family moved to Brooklyn, New York when he was 4 years old. He grew up in a musical context, his mother being a gospel singer, and he started to play bugle in parade orchestras at a young age. At the age of 10, he was already playing drums in some gospel bands. He performed his first big-time gig in New York City at the age of sixteen, substituting for Sonny Greer in a performance with the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

In 1942, Roach started to go out in the jazz clubs of the 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom (playing with schoolmate Cecil Payne). He was one of the first drummers (along with Kenny Clarke) to play in the bebop style, and performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis.

Roach played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy 1945 session, a turning point in recorded jazz.

Two children, son Daryl and daughter Maxine, were born from his first marriage with Mildred Roach. In 1954 he met singer Barbara Jai (Johnson) and had another son, Raoul Jordu.

He continued to play as a freelance while studying composition at the Manhattan School of Music. He graduated in 1952.

During the period 1962-1970, Roach was married to the singer Abbey Lincoln, who had performed on several of Roach's albums. Twin daughters, Ayodele and Dara Rasheeda, were later born to Roach and his third wife, Janus Adams Roach.

Long involved in jazz education, in 1972 he joined the faculty of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

In the early 2000s, Roach became less active owing to the onset of hydrocephalus-related complications.

Renowned all throughout his performing life, Roach has won an extraordinary array of honors. He was one of the first to be given a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, cited as a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in France, twice awarded the French Grand Prix du Disque, elected to the International Percussive Society's Hall of Fame and the Downbeat Magazine Hall of Fame, awarded Harvard Jazz Master, celebrated by Aaron Davis Hall, given eight honorary doctorate degrees, including degrees awarded by the University of Bologna, Italy and Columbia University.

In 1952 Roach co-founded Debut Records with bassist Charles Mingus. This label released a record of a concert, billed and widely considered as “the greatest concert ever,” called Jazz at Massey Hall, featuring Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Mingus and Roach. Also released on this label was the groundbreaking bass-and- drum free improvisation, Percussion Discussion.

In 1954, he formed a quintet featuring trumpeter Clifford Brown, tenor saxophonist Harold Land, pianist Richie Powell (brother of Bud Powell), and bassist George Morrow, though Land left the following year and Sonny Rollins replaced him. The group was a prime example of the hard bop style also played by Art Blakey and Horace Silver. Tragically, this group was to be short-lived; Brown and Powell were killed in a car accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in June 1956. After Brown and Powell's deaths, Roach continued leading a similarly configured group, with Kenny Dorham (and later the short-lived Booker Little) on trumpet, George Coleman on tenor and pianist Ray Bryant. Roach expanded the standard form of hard-bop using 3/4 waltz rhythms and modality in 1957 with his album Jazz in 3/4 time. During this period, Roach recorded a series of other albums for the EmArcy label featuring the brothers Stanley and Tommy Turrentine.

In 1960 he composed the “We Insist! - Freedom Now” suite with lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., after being invited to contribute to commemorations of the hundredth anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. Using his musical abilities to comment on the African-American experience would be a significant part of his career. Unfortunately, Roach suffered from being blacklisted by the American recording industry for a period in the 1960s. In 1966 with his album Drums Unlimited (which includes several tracks that are entirely drums solos) he proved that drums can be a solo instrument able to play theme, variations, rhythmically cohesive phrases. He described his approach to music as “the creation of organized sound.”

Among the many important records Roach has made is the classic Money Jungle 1962, with Mingus and Duke Ellington. This is generally regarded as one of the very finest trio albums ever made.

During the 70s, Roach formed a unique musical organization--”M'Boom”--a percussion orchestra. Each member of this unit composed for it and performed on many percussion instruments. Personnel included Fred King, Joe Chambers, Warren Smith, Freddie Waits, Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, Francisco Mora, and Eli Fountain.

Not content to expand on the musical territory he had already become known for, Roach spent the decades of the 80s and 90s continually finding new ways to express his musical expression and presentation.

In the early 80s, he began presenting entire concerts solo, proving that this multi-percussion instrument, in the hands of such a great master, could fulfill the demands of solo performance and be entirely satisfying to an audience. He created memorable compositions in these solo concerts; a solo record was released by Bay State, a Japanese label, just about impossible to obtain. One of these solo concerts is available on video, which also includes a filming of a recording date for Chattahoochee Red, featuring his working quartet, Odean Pope, Cecil Bridgewater and Calvin Hill.

He embarked on a series of duet recordings. Departing from the style of presentation he was best known for, most of the music on these recordings is free improvisation, created with the avant-garde musicians Cecil Taylor, Anthony Braxton, Archie Shepp, Abdullah Ibrahim and Connie Crothers. He created duets with other performers: a recorded duet with the oration by Martin Luther King, “I Have a Dream”; a duet with video artist Kit Fitzgerald, who improvised video imagery while Roach spontaneously created the music; a classic duet with his life-long friend and associate Dizzy Gillespie; a duet concert recording with Mal Waldron.

He wrote music for theater, such as plays written by Sam Shepard, presented at La Mama E.T.C. in New York City.

He found new contexts for presentation, creating unique musical ensembles. One of these groups was “The Double Quartet.” It featured his regular performing quartet, with personnel as above, except Tyrone Brown replacing Hill; this quartet joined with “The Uptown String Quartet,” led by his daughter Maxine Roach, featuring Diane Monroe, Lesa Terry and Eileen Folson.

Another ensemble was the “So What Brass Quintet,” a group comprised of five brass instrumentalists and Roach, no chordal instrumnent, no bass player. Much of the performance consisted of drums and horn duets. The ensemble consisted of two trumpets, trombone, French horn and tuba. Musicians included Cecil Bridgewater, Frank Gordon, Eddie Henderson, Steve Turre, Delfeayo Marsalis, Robert Stewart, Tony Underwood, Marshall Sealy, and Mark Taylor.

Roach presented his music with orchestras and gospel choruses. He performed a concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He wrote for and performed with the Walter White gospel choir and the John Motley Singers. Roach performed with dancers: the Alvin Aily Dance Company, the Dianne McIntyre Dance Company, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company.

In the early 80s, Roach surprised his fans by performing in a hip hop concert, featuring the artist-rapper Fab Five Freddy and the New York Break Dancers. He expressed the insight that there was a strong kinship between the outpouring of expression of these young black artists and the art he had pursued all his life.

During all these years, while he ventured into new territory during a lifetime of innovation, he kept his contact with his musical point of origin. His last recording, “Friendship”, was with trumpet master Clark Terry, the two long-standing friends in duet and quartet.

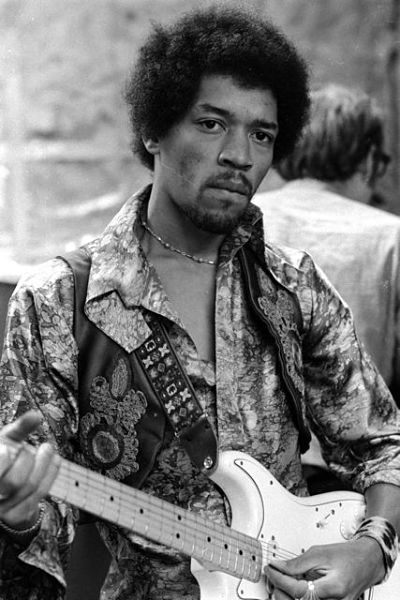

Drummer Max Roach broke new ground in jazz

Max Roach

Birthdate: January 10, 1924

Max Roach was born on this date in 1924. He was an African American bebop/hard bop percussionist, drummer, and composer.

Maxwell Lemuel Roach was born in Newland, N.C., to Alphonse and Cressie Roach. His family moved to Brooklyn, when he was 4 years old. A player piano left by the previous NY tenants gave Roach his musical introduction and he started to play bugle in parade orchestras at a young age. His mother was a gospel singer, which led to Roach, at 10, to play drums in some gospel bands. Roach performed his first big-time gig in New York City at the age of 16, substituting for Sonny Greer with the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

In 1942, Roach started to go out in the jazz clubs of the 52nd Street and at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay's Taproom (playing with schoolmate Cecil Payne). He was one of the first drummers (along with Kenny Clarke) to play in the bebop style, and performed in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, Bud Powell, and Miles Davis. Roach played on many of Parker's most important records, including the Savoy 1945 session. He continued to play as a freelancer while studying composition at the Manhattan School of Music, where he graduated in 1952.

He had two children, Daryl and Maxine, from his first marriage with Mildred Roach. In 1954, he met singer Barbara Jai (Johnson) and had another son, Raoul Jordu. In 1960, he composed the “We Insist! - Freedom Now” suite with lyrics by Oscar Brown Jr., after being invited to contribute to commemorations of the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. Using his musical abilities to comment on the African-American experience was a significant part of his career. Because of this, Roach was blacklisted by the American recording industry for a period in the 1960s.

Roach was also married to the singer Abbey Lincoln, who had performed on several of Roach's albums. Twin daughters, Ayodele and Dara Rasheeda, were later born to Roach and his third wife, Janus Adams Roach. In 1966, with his album "Drums Unlimited,” he proved that drums can be a solo instrument able to play theme, variations, and rhythmically cohesive phrases. Another important record Roach made is the classic “Money Jungle,” 1962, with Charley Mingus and Duke Ellington.

During the 1970s, Roach formed a unique musical organization, "M'Boom," a percussion orchestra. Each member of this unit composed and performed on many percussion instruments. Members included Fred King, Joe Chambers, Warren Smith, Freddie Waits, Roy Brooks, Omar Clay, Ray Mantilla, Francisco Mora, and Eli Fountain.

In 1972, he joined the faculty of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Not content to expand on the musical territory he had already become known for, Roach spent the decades of the 1980s and 1990s continually finding new ways to express his musical expression and presentation. In the early 1980s, he began presenting solo concerts, proving that this multi-percussion instrument, in the hands of such a great master, could fulfill the demands of solo performance and be entirely satisfying to an audience. He created memorable compositions in these concerts. A solo record was released by Bay State, a Japanese label. One of these solo concerts also includes a filming of a recording date for "Chattahoochee Red," featuring his working quartet with Odean Pope, Cecil Bridgewater, and Calvin Hill.

In the early 2000s, Roach became less active owing to the onset of hydrocephalus-related complications. Renowned all throughout his performing life, Roach won many honors. Some of them include a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant, cited as a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in France, twice awarded the French Grand Prix du Disque, elected to the International Percussive Art Society's Hall of Fame, and the Downbeat Magazine Hall of Fame.

He was awarded the Harvard Jazz Master, given eight honorary doctorate degrees, including degrees awarded by the University of Bologna, Italy, and Columbia University. He worked with many of the greatest jazz musicians in the world. He is widely considered one of the most important drummers in the history of jazz. Max Roach died on August 16, 2007 at his home.

http://www.biography.com/people/max-roach-9459691#evolving-career

Max Roach

Max Roach Biography

Drummer, Educator, Civil Rights Activist, Songwriter (1924–2007)

Quick Facts

Name

Max Roach

Occupation

Drummer, Educator, Civil Rights Activist, Songwriter

Birth Date

January 10, 1924

Death Date

August 16, 2007

Education

Manhattan School of Music

Place of Birth

New Land, North Carolina

Place of Death

New York, New York

AKA

Maxwell Roach

Max Roach

Full Name

Maxwell Lemuel Roach

Synopsis

Early Life

Jazz Success

Evolving Career

Later Years

Cite This Page

A pioneer of the bebop style, drummer Max Roach spent decades creating innovative jazz.

IN THESE GROUPS

1 of 6

quotes

“You can't write the same book twice. Though I've been in historic musical situations, I can't go back and do that again. And though I run into artistic crises, they keep my life interesting.”—Max Roach

Max Roach was born on January 10, 1924, in New Land, North Carolina. He was raised in Brooklyn and studied at the Manhattan School of Music. One of the great jazz drummers and a pioneer of bebop, he worked with Coleman Hawkins, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz, Charlie Parker and Clifford Brown. Roach was also a composer and a professor of music at the University of Massachusetts. He died in New York City in 2007.

Early Life

Maxwell Lemuel Roach, generally known as Max Roach, was born on January 10, 1924, in New Land, North Carolina. He was raised in Brooklyn and played in gospel groups as a child. Though he started on the piano, Roach found his instrument when he began playing the drums at age 10.

Jazz Success

Growing up in New York City exposed Roach to an exuberant jazz scene. In 1940, 16-year-old Roach filled in with Duke Ellington's orchestra. During the 1940s, he played with jazz greats like Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Benny Carter and Stan Getz. Roach further developed his skills by studying at the Manhattan School of Music.

Roach joined with Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and others to help bebop—a form of jazz that featured more intense rhythms and sophisticated musicality—come into being. He soon gained a reputation as a virtuoso bebop drummer, one who could enhance a song with his musical choices. From 1947 to 1949, Roach was part of Parker's trailblazing quintet.

Roach's drumming could be heard on many recordings, starting with his debut with Hawkins in 1943. His other albums include Woody 'n' You (1944)—considered one of the first bebop records—and Davis's Birth of the Cool sessions in 1949-50. In 1952, Roach co-founded Debut Records with Charles Mingus. The label released a recording of a seminal jazz concert held at Massey Hall in 1953, where Roach performed with Mingus, Parker, Gillespie and Bud Powell.

In 1954, Roach and Clifford Brown formed a quintet that became one of the most highly regarded groups in modern jazz. Unfortunately, their collaboration ended when Brown and another member of the group were killed in a 1956 car accident. The loss was a depressing blow for Roach; he began drinking heavily, but eventually sought professional help to regain his footing. He also continued creating music, taking on projects with Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins.

Evolving Career

With We Insist! Freedom Now Suite (1960), Roach used music to address the need for racial equality. Despite the risks that taking an outspoken political stance posed to his career, Roach continued to support the Civil Rights Movement. He later created a drum accompaniment for Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

In 1972, Roach was named as a professor of music at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. His career accomplishments were further recognized when Roach was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame in 1982, and when he was selected as a 1984 Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts. In 1988, Roach received a MacArthur Foundation "genius grant," the first given to a jazz musician.

Roach's adaptability and inventiveness spurred him to work on an increasingly diverse list of projects. In 1970, he founded M'Boom, an all-percussion group. Roach also composed for choreographer Alvin Ailey and created music for plays written by Sam Shepard (his work with Shepard garnered Roach an Obie Award). His other collaborators include hip-hop artists Fab Five Freddy, writer Toni Morrison (Roach provided musical accompaniment at her spoken word concerts), Japanese taiko drummers and avant-garde instrumentalists Cecil Taylor and Anthony Braxton.

Later Years

Roach gave his last concert in 2000 and made his final recording in 2002.He suffered from a neurological disorder for an extended period before his death in New York City on August 16, 2007, at the age of 83. All three of Roach's marriages ended in divorce, but he was survived by two sons and three daughters.

http://www.biography.com/people/max-roach-9459691Access Date

November 14, 2015

Publisher

A&E Television Networks

http://www.drumlessons.com/drummers/max-roach/

Max Roach Biography, Videos & Pictures

Max Roach

Who Is Max Roach?

Max Roach is regarded as one of the most important drummers in the history of jazz. His contributions to jazz music and modern drumming are invaluable. Max Roach, along with guys like Kenny Clarke, shaped what is now regarded as the standard vocabulary of modern jazz drumming with the invention of bebop.

Maxwell “Max” Lemuel Roach was born to Alphonse and Cressie Roach in the small town of Newland, Pasquotank County, North Carolina. His parents were part of an enclave of black farmers who’d harvest and sell their goods collectively. At the time, black farmers could sell their goods only when the white farmers’ had sold out. This was troublesome for Max Roach’s parents, because when it came their time to sell, the prices had to go down if they wanted to earn any money. This also meant insufficient earnings to cover the costs of their farming activities.

Therefore, Max Roach, his parents and his older brother moved to Brooklyn, New York in 1928 to better their social conditions. They lived in the neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant (Bed-Stuy). Although poor, Max Roach had high regards for Bed-Stuy’s inhabitants.

“Although the crash came a year later (1929), and although the people were poor and disenfranchised, they had a lot of pride. Nobody was slick, everybody was honest. People went to church.” – Max Roach

Max Roach’s first experiences with musical instruments began in elementary school. The public school he went to had music teachers who taught him and his classmates how to play instruments, allowing them to take musical instruments home.

Max Roach and his family spent most of their time at a neighborhood Baptist church, where his mother sang with the choir. It was in that church that Max Roach’s family was exposed to the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). FERA’s philosophy was to put the unemployed back to work in jobs which would serve the public good and conserve the skills and the self-esteem of workers throughout the United States (U.S.) during the crisis.

Amongst other things, FERA provided classes in rural areas and urban neighborhoods with music instruction every week. So Max Roach’s parents would leave their kids in church to learn how to play musical instruments, while they were out working. An 8 years old Max Roach began his musical journey behind a piano. Since Max Roach enjoyed doing everything his older brother did, when his brother decided to learn how to play bugle, Max Roach followed on his footsteps. Seeing he couldn’t deal with the bugle that well, Max Roach’s mother advised him to chose a different instrument. Max Roach returned the bugle to his teacher and decided to take a snare drum home instead.

Max Roach’s first experiences with a drum set came at house rent parties. Those social events were organized by tenants to raise money to pay their rent and food, and featured hired musicians. Max Roach’s first band experiences were as the drummer for a couple of gospel bands, at the tender age of 10.

Even before graduating from high school in 1942, Max Roach was already a well known drummer in the New York jazz music scene. Max Roach performed his first big gig in New York City at the age of 16, substituting for Sonny Greer in a performance with the Duke Ellington Orchestra at the Paramount Theater.

In 1942, Max Roach began venturing into jazz clubs of the 52nd Street. He also played at 78th Street & Broadway for Georgie Jay’s “Taproom”, where he could be found performing alongside schoolmate and jazz baritone saxophonist Cecil Payne. Max Roach played with Charlie Parker at Clark Monroe’s “Uptown House” in Harlem, New York as well. As the a house drummer for the Uptown House, Max Roach took part in late night jam sessions that helped lay the groundwork for bebop.

Bebop is Max Roach and Kenny Clark’s most significant innovation and contribution to music. Bebop was a new form of jazz, a new concept of playing time musically. By moving the time-keeping function from the bass drum to the ride cymbal, Max Roach and Kenny Clarke allowed soloists to play freely. This new approach freed the drummer as well, leaving him enough space to insert dramatic accents on any other instrument on the drum set. Bebop was also a great way of taking full advantage of the drummer’s unique position – a musician who plays music with his four limbs.

Career Highlights And Musical Projects

Besides his work with Charlie Parker, within a few years, Max Roach would be found playing in bands led by Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Coleman Hawkins, and Bud Powell. Still in his twenties, Max Roach contributed with his extreme musicality to such seminal recordings as Charlie Parker’s The Complete Savoy Studio Recordings (1945 – 1948) and Miles Davis’s Birth Of The Cool, recorded between 1949 and 1950 and released in 1956. This album is the sole responsible for the cool-jazz movement.

In 1952, Max Roach co-founded Debut Records with bassist Charles Mingus and his wife at the time, Celia Mingus. Debut Records was the label on which the classic live album Jazz at Massey Hall, featuring Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus and Max Roach was first issued. In that same year, Max Roach graduated from the Manhattan School of Music with a major in Music Composition. In 1957, Max Roach made another important contribution to the world of jazz music with the album Jazz in 3/4 Time, where he expanded on the standard form of bebop using 3/4 odd-time signature.

In 1960, Max Roach composed “We Insist!”. This album was Mas Roach’s contribution to the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. In 1962, Max Roach released Money Jungle, one of the best trio-based bands’ albums ever made. The year of 1966 saw the release of the album Drums Unlimited, which unveiled the drum set as a solo instrument capable of creating very musical statements.

In 1970, Max Roach formed a jazz percussion ensemble called M’Boom. The intention behind the project was that of exploring the sound of unconventional and non-Western percussion instruments. Over the years, M’Boom featured percussionists like Roy Brooks, Joe Chambers, Omar Clay, Warren Smith, and Freddie Waits in its ranks. M’Boom released three albums: Re: Percussion (1973); M’Boom (1979); Collage (1984); Live at S.O.B.’s New York (1992). The ensemble disbanded in 1992. In 1972, Max Roach became one of the first jazz musicians to teach full-time at a college, when he was hired as a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Max Roach’s tenure with the university ended in 1979.

In 1983, Max Roach broke new ground when he was joined in concert by a rapper, two DJs and a team of break dancers. In 1984, Max Roach composed music for a couple of Sam Shepard’s Off-Broadway productions. In 1986, a park in Brixton, London was named after Max Roach. In 1988, Max Roach was given a prestigious MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant. The following year, Max Roach was cited as a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in France.

Max Roach’s long list of awards includes two French “Grand Prix du Disque” and the “Harvard Jazz Master”. Max Roach was awarded eight honorary doctorate degrees and was inducted into the International Percussive Art Society’s and the Downbeat magazine’s Hall of Fame. In his later years of life, Max Roach’s musical achievements were honored with a proclamation by Brooklyn’s president Marty Markowitz.

Max Roach died on August 16, 2007 in Manhattan. He was survived by his six children: sons Daryl and Raoul, daughters Maxine, Ayo and Dara, and bebop.

What Can We Learn From Max Roach?

Max Roach was one of the most musical drummers to ever grace our planet. A good way to sum up his drumming abilities on the drum set is to look at his improvisational skills and ability to create exquisite sounding drum solos.

Max Roach’s approached improvisation as free as possible. He didn’t spend any time prepping his improvisational sections beforehand. Max Roach enjoyed dealing with his musical thoughts on the spot, allowing the moment to create itself. This enabled him to take more enjoyment out of what he was playing on the drum set, since it was a natural response to the moment he was in. Having a lot of technique at his disposal, like high levels of independence, hand technique, and foot technique enabled him to do so. However, Max Roach’s incredible set of tools served only his ability to communicate different ideas.

Although Max Roach enjoyed coming up with new patterns within a single piece, he made sure he returned to ideas that were still within the structure of his drum solos. He would do so by repeating those ideas throughout certain sections of the solo. This concept of design within solos and improvisational pieces were more important to Max Roach than melodic or harmonic content. This concept is an integral part of his very popular drum solos, like “Big-Sid” for instance, which he wrote in honor of Big Sid Catlett, one his favorite drummers. This also gave his drum solos and improvisational pieces an awesome sense of musicality and theme.

Another one of Max Roach’s cool concepts when it came down to soloing, was his use of feet-ostinato vamps. Drum solos like “The Third Eye” and “Drum Waltz” are great examples of that. While keeping a steady ostinato going with his feet, Max Roach played the main statements and themes on top of the vamps.

Max Roach’s approach to improvisation can teach us quite a lot of things. First, Max Roach shows us that technique is paramount for artistic expression on the drum set. The more things you’re able to play, the better you’ll be at expressing yourself on the drum set. This is, of course, a direct result of the bebop style he enjoyed playing so much, which demanded high levels of independence, hand technique and foot technique. So working on drum set independence, hand technique, drum rudiments, and foot technique can, and will make you a lot more expressive during solos and help you write cooler sounding and original drum beats and drum fills.

Second, the way Max Roach approached soloing pretty much took drum solos in a whole new direction. Instead of bashing and unleashing a series of notes on the drum set just for the sake of it, Max Roach worked on different themes and ideas. That, coupled with the names he baptized them with, gave his solos a strong identity, almost like if they were songs. This way of approaching soloing is very interesting and original, resembling the way stories are written for books and movies. Max Roach builds on the emotion of his drum solos as he goes along, using different textures, rhythms, and dynamic levels.

Incorporating this type of concepts to your drum solos will make you a better listener, since you’ll have to remember the main themes of your solos as you go along. This will also have you working in an more organized framework. Max Roach’s soloing concepts are way different what a lot of drummer do when told to solo, like unleashing loud and fast strokes around the kit. This comes to show how creative one can be with drum solos.

http://jazzhistoryonline.com/Clifford_Brown_Max_Roach.html

Clifford Brown/Max Roach: "Historic California Concerts' (Fresh Sounds 377)

by Thomas Cunniffe

Starting in 1945, Los Angeles was a hotbed of bebop. While Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were recording their classic Guild and Musicraft sides in New York, Coleman Hawkins was in LA with a modernist band including Howard McGhee and Sir Charles Thompson. By the end of the year, Parker and Gillespie traveled west for a gig at Billy Berg’s in Hollywood. Parker stayed behind after the rest of the band went home. Following a disastrous breakdown and temporary cure for his heroin habit, he recorded with McGhee, Wardell Gray, Erroll Garner and Dodo Marmarosa before returning east. Meanwhile, in the clubs along Central Avenue, jam sessions featuring McGhee, Gray, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Criss and Hampton Hawes had the audiences cheering on their favorite players. Within a few years, the scene waned, and many of the clubs either closed or were converted into strip joints. The primary musicians went on tours with major bands or were off the scene because of drug addictions. By 1952, through the successes of Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond, Shorty Rogers, Bud Shank, Bob Cooper, Howard Rumsey, Shelly Manne and others, California jazz was generally synonymous with cool jazz.

When Manne left Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars to join Rogers’ new cool quintet, he recommended Max Roach

to fill his position. Roach and Manne had been friends since their days

in New York, and Roach had played the cool style in broadcasts and

recordings with Miles Davis and Lee Konitz.

During his six months with the Lighthouse group, Roach created a local

sensation with his drumming, and played on several live Lighthouse

recordings as well as studio sessions like the Cooper/Shank LP, “Oboe/Flute”.

The California gig allowed Roach to show his adaptability, but he never

stopped listening to the harder-edged music from New York, including Art Blakey’s “A Night at Birdland” and “The Eminent J.J. Johnson”. Both of those albums featured a remarkable young trumpeter named Clifford Brown.

When Brown arrived on the scene in 1953, he seemed to be just what jazz

needed: an imaginative young trumpeter with a full brilliant sound and

remarkable technical prowess. Those who knew him personally also praised

his sunny disposition and his aversion to alcohol, tobacco and

narcotics. As Roach’s Lighthouse contract was ending, concert promoter Gene Norman

talked to the drummer about forming his own group. Roach

agreed—provided that Norman would give them gigs to play—and immediately

sought out Brown to be his co-leader. Norman was good to his word,

providing a long-standing engagement at Pasadena’s California Club, and

setting up a West Coast tour. He also featured the Brown/Roach Quintet

in concerts at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium and LA’s Shrine Auditorium.

Those concerts were recorded and later issued on Norman’s GNP label,

but their best presentation is on the Fresh Sound CD “Historic California Concerts”, which restores the recordings to their full length and improves the sound.

The

Pasadena concert was recorded in April 1954. The band had only been in

existence for about two months, but had already played a few weeks at

the California Club. The fine and under-rated tenor saxophonist Teddy Edwards shares the front line with Brown. The piano chair was filled by Carl Perkins—not the “Blue Suede Shoes” singer, of course, but a bopper who played with his left arm parallel to the keybo ard

(owing to a battle with polio). The bassist was the steady but

unremarkable George Bledsoe. None of the pieces recorded in Pasadena

found a place in the group’s permanent repertoire, but the performances

are spirited and the audience clearly appreciated the energy of this

driving bebop group. After an introduction featuring brief solos by each

member of the group (omitted from the GNP 12” LP), the group launches

into a medium-up version of “All God’s Children Got Rhythm”. Edwards

starts the solos with a beefy tenor solo that is abruptly cut off after

one chorus. Brown is next and Roach’s ongoing rhythmic commentary spurs

the trumpeter through a brilliant extended solo. Perkins’ fleet piano is

also cut off after one chorus (these edits were on all previous

editions and could not be restored for the CD), but Roach’s complex drum

solo is kept intact. Gillespie’s strong influence on Brown can be heard

in the opening phrases of Brown’s ballad feature, “Tenderly”, but one

can also hear the subtle half-valved effects and the fluidity in all

ranges of the horn that became part of his mature style. “Sunset Eyes”

predicts the group’s use of tidy and effective arrangements. The A

sections of Edwards’ composition feature a sensuous tune over a single

chord, and the bridge has an exuberant melody over a standard ii-V-I

bebop progression. Edwards also wrote an out-chorus over the A section.

On the final chorus of the Brown/Roach arrangement, the band plays 16

bars of the out-chorus, then jumps back to the bridge and closes

with 8 bars of the original A section. The syncopated pick-up to the

bridge gives a dramatic lift to the arrangement, and it’s surprising

that Edwards never used this arrangement in his own recordings. Edwards

plays a fine solo here, and both he and Brownie explore the harmonic

contrasts between the main strain and the release. Edwards lays out on

the last track, “Clifford’s Axe”, which is a relaxed long-meter jam on

the changes of “The Man I Love”. The masterly sculpting of his

improvised lines and the steady pacing of the solo belies Brown’s age

(23), and the interplay with Roach—which would develop to amazing

heights over the next two years—is already quite stunning.

ard

(owing to a battle with polio). The bassist was the steady but

unremarkable George Bledsoe. None of the pieces recorded in Pasadena

found a place in the group’s permanent repertoire, but the performances

are spirited and the audience clearly appreciated the energy of this

driving bebop group. After an introduction featuring brief solos by each

member of the group (omitted from the GNP 12” LP), the group launches

into a medium-up version of “All God’s Children Got Rhythm”. Edwards

starts the solos with a beefy tenor solo that is abruptly cut off after

one chorus. Brown is next and Roach’s ongoing rhythmic commentary spurs

the trumpeter through a brilliant extended solo. Perkins’ fleet piano is

also cut off after one chorus (these edits were on all previous

editions and could not be restored for the CD), but Roach’s complex drum

solo is kept intact. Gillespie’s strong influence on Brown can be heard

in the opening phrases of Brown’s ballad feature, “Tenderly”, but one

can also hear the subtle half-valved effects and the fluidity in all

ranges of the horn that became part of his mature style. “Sunset Eyes”

predicts the group’s use of tidy and effective arrangements. The A

sections of Edwards’ composition feature a sensuous tune over a single

chord, and the bridge has an exuberant melody over a standard ii-V-I

bebop progression. Edwards also wrote an out-chorus over the A section.

On the final chorus of the Brown/Roach arrangement, the band plays 16

bars of the out-chorus, then jumps back to the bridge and closes

with 8 bars of the original A section. The syncopated pick-up to the

bridge gives a dramatic lift to the arrangement, and it’s surprising

that Edwards never used this arrangement in his own recordings. Edwards

plays a fine solo here, and both he and Brownie explore the harmonic

contrasts between the main strain and the release. Edwards lays out on

the last track, “Clifford’s Axe”, which is a relaxed long-meter jam on

the changes of “The Man I Love”. The masterly sculpting of his

improvised lines and the steady pacing of the solo belies Brown’s age

(23), and the interplay with Roach—which would develop to amazing

heights over the next two years—is already quite stunning.

By August 30, when the group performed at the Shrine, the personnel had stabilized to include Harold Land on tenor, Richie Powell on piano and George Morrow

on bass. The band had abundantly recorded in the intervening months,

including its own debut album for EmArcy, and studio jam sessions

featuring Dinah Washington, Maynard Ferguson, Clark Terry, Herb Geller, Walter Benton and Curtis Counce. Just how Gene Norman  obtained

the rights to record the already-contracted Brown and Roach at the

Shrine has never been fully explained, but the recording offers one of

the earliest examples of this group in a live context. Three of the four

songs from that night had been recorded by the quintet for EmArcy

earlier in the month, and the group seems very comfortable with the

tunes and the arrangements. “Jordu” features relaxed solos by both Brown

and Land, with both soloists effectively punctuating their lines with

sharp rhythmic motives. Powell tries to spice up his solo with a few

quotes, but he was still an immature player and a mere shadow of his

brother Bud. Roach astonishes with another brilliant display of

polyrhythmic expertise (Land and Powell’s solos only appear on the GNP

10” LPs and on the Fresh Sounds CD). Brown’s ballad feature this time is

“I Can’t Get Started”, a tune which he never recorded again. This

version is hampered by PA feedback that distorts Brown’s rich trumpet

sound. A pity, since this is one of Brownie’s most understated ballad

performances. Next up is the band’s tricky mixed-meter version of “I Get

a Kick out Of You” (arranged by either Sonny Stitt or Thad Jones).

Roach sets an extremely bright tempo, but Brown sounds quite

comfortable playing at this quick pace, laying out long phrases over

several bars. Land is a little more frantic, but generates a lot of

excitement. Powell tries to mix the approaches of the horn men, but his

underdeveloped melodic imagination makes the effort sound disorganized

and chaotic. Roach’s solo brings things back to normal with a dense

thunder of percussion. The final track is Bud Powell’s “Parisian Thoroughfare”, complete with instrumental imitations of a French traffic jam. While

the opening is at an even faster tempo than “Kick”, it settles into a

medium-up groove for the melody and solos. Land’s sound is as warm as a

wool jacket, and his off-hand quote of Offenbach’s can-can theme works

very well. Brown is wonderfully melodic in his solo, and the legato in

his tone seems to reflect Roach’s smooth ride cymbals in the background.

obtained

the rights to record the already-contracted Brown and Roach at the

Shrine has never been fully explained, but the recording offers one of

the earliest examples of this group in a live context. Three of the four

songs from that night had been recorded by the quintet for EmArcy

earlier in the month, and the group seems very comfortable with the

tunes and the arrangements. “Jordu” features relaxed solos by both Brown

and Land, with both soloists effectively punctuating their lines with

sharp rhythmic motives. Powell tries to spice up his solo with a few

quotes, but he was still an immature player and a mere shadow of his

brother Bud. Roach astonishes with another brilliant display of

polyrhythmic expertise (Land and Powell’s solos only appear on the GNP

10” LPs and on the Fresh Sounds CD). Brown’s ballad feature this time is

“I Can’t Get Started”, a tune which he never recorded again. This

version is hampered by PA feedback that distorts Brown’s rich trumpet

sound. A pity, since this is one of Brownie’s most understated ballad

performances. Next up is the band’s tricky mixed-meter version of “I Get

a Kick out Of You” (arranged by either Sonny Stitt or Thad Jones).

Roach sets an extremely bright tempo, but Brown sounds quite

comfortable playing at this quick pace, laying out long phrases over

several bars. Land is a little more frantic, but generates a lot of

excitement. Powell tries to mix the approaches of the horn men, but his

underdeveloped melodic imagination makes the effort sound disorganized

and chaotic. Roach’s solo brings things back to normal with a dense

thunder of percussion. The final track is Bud Powell’s “Parisian Thoroughfare”, complete with instrumental imitations of a French traffic jam. While

the opening is at an even faster tempo than “Kick”, it settles into a

medium-up groove for the melody and solos. Land’s sound is as warm as a

wool jacket, and his off-hand quote of Offenbach’s can-can theme works

very well. Brown is wonderfully melodic in his solo, and the legato in

his tone seems to reflect Roach’s smooth ride cymbals in the background.

Soon

after the Shrine concert, the Brown/Roach quintet relocated on the East

Coast, but its formative months on the West Coast helped revitalize

California’s modern jazz scene. Within a year, a steady stream of

hard-edged bebop emerged from the West Coast. When Harold Land left

Brown/Roach in late 1955, he joined the Curtis Counce Group,

which became one of the finest bop groups in LA. Both Land and Teddy

Edwards remained important players on the LA jazz scene for the rest of

their lives, and they played together in the Gerald Wilson big band. Carl Perkins was an early member of the Counce Group, but died of a drug overdose in 1958. Sonny Rollins

replaced Land in the Brown/Roach quintet, and the resulting chemistry

made the group one of the finest exponents of the bebop style. It all

ended tragically when Brown, Powell and Powell’s wife died in an

automobile accident on the Pennsylvania Turnpike on June 26, 1956. It

took Roach several years to fully recover, but eventually he came back

with a powerful new group (ironically featuring another short-lived

trumpeter, Booker Little) that recorded classic albums like “Freedom Now Suite” and “Percussion Bitter Sweet”.

Had Clifford Brown survived the accident, he would have been in his

mid-eighties by now. Heaven only knows what directions he would have

taken had his career not been cut off in his twenty-fifth year. Like

JFK, the youth of Clifford Brown is locked forever in a time capsule,

and the hope and optimism he personified will forever be linked with the

sorrow of his early demise.

Content copyright 2015. Jazz History Online.com. All rights reserved.

http://www.jazzhistoryonline.com/Max_Roach.html

“We Insist!: Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite (Candid 79002)

by Thomas Cunniffe

“We Insist!: Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite (Candid 79002)

by Thomas Cunniffe

By the summer of 1960, the civil rights movement was gathering momentum, albeit in spits and starts. The “sit-in” movement had successfully desegregated the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, NC by July 25, but when Martin Luther King participated in a sit-in at the all-white Rich’s Restaurant in Atlanta the following October, he and 51 others were arrested as trespassers. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee had met for the first time on April 15, and the Freedom Riders commenced early in 1961. On August 31 and September 6, 1960, Max Roach brought in his quintet and several guest artists to the Nola studios in New York to record his “Freedom Now Suite”, the most overt political jazz recording made to that date.

Roach’s quintet included Booker Little, a phenomenally

talented trumpeter who had discovered his own style under Roach’s tutelage.

Little had come to Roach’s group as a teenager, and his early recordings show

him playing strings of sixteenth-notes with little melodic direction. During

his three years with Roach, he learned how to pick the right notes and remove

all of the excess. Throughout the album, Little’s solos project a deep feeling

of melancholy that is still unique in jazz. Trombonist Julian Priester was an

alumni of Sun Ra’s Arkestra, but was already on the studio scene when he joined

Roach in 1959; bassist James Schenk had only appeared on a 1955 Bobby Banks

date prior to “Freedom Now”, and tenor saxophonist Walter Benton had worked in

Los Angeles from the mid-fifties, and had first recorded with Roach on a

Clifford Brown jam session in 1954. However, the tenor saxophonist that made

the greatest impact with his appearance on “Freedom Now” only played on the

opening track. That was the legendary Coleman Hawkins, and his emotional solo

on “Driva Man” not only added musical credence to the recording, but also added

a multi-generational element to the personnel.

Without a doubt, the focal point of “Freedom Now” was

vocalist Abbey Lincoln. Lincoln

had made a well-publicized leap from the conservative supper clubs of the

fifties to the progressive jazz scene of the sixties. She had removed most of

the love songs and standards from her repertoire, and her voice took on a

coarse tone, with anger that seemed to simmer right below the surface. Singing

the politically charged lyrics of Oscar Brown, Jr., “Freedom Now” represented a

breakthrough for both the vocalist and lyricist.

Thematically, the five movements of “Freedom Now Suite”

divide into three sections. The first two movements, “Driva Man” and “Freedom

Day” are set in the times surrounding the Civil War (although “Freedom Day”

logically extends itself to the present and future times), the third movement

is a three-part duet by Lincoln and Roach (of which more below) and the final

two movements, “All Africa” and “Tears For Johannesburg”—which add

percussionists Michael Olatunji, Ray Mantilla and Tomas DuVall to the

group—deal with contemporary civil rights issues in the African homeland.

Accompanied only by a tambourine, Lincoln bites into the lyrics of “Driva Man”

and when the band comes in, Hawkins is the dominant voice. His intense sound

stands in stark relief against the piano-less background. As Nat Hentoff relays

in his superb liner notes, Hawkins’ solo contained a reed squeak which the

saxophonist insisted be left in the final recording: “When it’s all perfect,

especially in a piece like this, there’s something very wrong”. “Freedom Day”

sounds like it might be jubilant, but the sorrowful edge of Little’s lead trumpet

tempers that feeling. Little’s solo has a lot of notes, but it is uncanny how

the listener retains the striking color tones even amidst a flurry of notes.

After impressive solos by Benton and Priester, Roach plays his only solo on the

band portions of the suite. This solo develops ideas from a basic rhythmic

motive, and seems to fall in line with the chronology of composed drum solos

that Roach played later in his career.

The second side of the LP comprised the final two movements.

As on the first side, the music opens with Lincoln accompanied only by drums. After the

opening chorus, “All Africa” becomes a vocal duet between Lincoln and Olantunji

with Lincoln

singing the names of African tribes and Olantunji responding in the Yoruba

dialect. These names are familiar to us now, but they must have been quite

exotic to 1960 ears! The final three minutes of the movement are given to a

long, but fascinating percussion interlude involving Roach and the three guest

percussionists. “Tears For Johannesburg” follows without pause. There are no

words to this final movement—Lincoln

sings a plaintive legato vocalese that speaks volumes about the insanity of

apartheid. I suspect that Little wrote the horn arrangements throughout this

album; they speak with the same harmonic voice as his trumpet, and they are

quite similar to the arrangements on his later album for Candid. His solo on

“Tears” cuts right to the emotional bone, and while Benton’s solo seems rooted in bebop, it is by

far his most emotional solo of the date. The other horns and percussionists

build a frenzied background behind the tenor solo and continue it under

Priester’s extended trombone solo. Finally, the drums and percussion take over,

with Roach dominating the proceedings with impressive pyrotechnics. The horn

line that follows melds into an improvised duet for trumpet and tenor, then

moves back to written lines before the final fade-out.

I’ve saved the central Roach/Lincoln duet for last because

it is the most controversial and the most problematic. Originally conceived and

performed as music for a ballet, the “Triptych” is entirely wordless. The

opening section called “Prayer” features Lincoln

singing long legato lines on an “oo” vowel over Roach’s spare ostinato. As the

lines intensify, Lincoln

changes vowels to an “ee” and finally to “ah” as the section ends. Suddenly,

the tempo and mood changes for “Protest” which consists of Lincoln screaming

(not scream-like singing, real primal screaming) over Roach’s lightning-fast

drums. Lincoln

returns to normal singing techniques in “Peace” where she performs a group of

sighs, laughs and short lines again to Roach’s rhythmic ostinato. Now, I’ve

heard all of the arguments regarding this piece—it’s the central point of the

entire suite and the screaming is the natural release of hundreds of years of racial

inequality; no one but Abbey Lincoln could have performed this with such

conviction; and (the dreaded) “you’re not supposed

to like it”—and I agree with all of them. But no matter how insensitive it

makes me sound, those 75 seconds of screaming have diverted me from listening

to “Freedom Now Suite”. I suspect that there are many others who feel the same

way. I’ve never been a fan of listening to something simply because it’s good

for me. But there is something about making your work so repulsive that you

lose the audience you wanted to address.

Just over a half-century later, we have an African-American

president, and while Barack Obama has not been embraced by some Americans, he

won the election by a substantial margin. If you call Obama’s election “Freedom

Day”, then only Abbey Lincoln, Julian Priester, Ray Matilla (and possibly Tomas

DuVall and James Schenck) lived to see it. Roach died before Obama’s campaign

had gained much steam, Olantunji preceded Roach in death by four years, Benton passed in 2000,

Hawkins in 1969, and Booker Little died just 13 months after recording “Freedom

Now Suite”. The recording stands as a powerful monument to a difficult time

we’d all rather forget.

Content copyright 2015. Jazz History Online.com. All rights reserved.

August 27, 2007

Max Roach 1924-2007: Thousands Pay Tribute to the Legendary Jazz Drummer, Educator, Activist

Over 2,000 people gathered at Riverside Church in New York on Friday for the funeral of the legendary drummer, educator and activist Max Roach, who died on August 16 at the age of 83. He was credited with helping to revolutionize the sound of modern jazz and for playing a prominent role in the struggle for black liberation at home and in Africa. We speak with two men who have known Roach for decades: Amiri Baraka and Phil Schaap. [includes rush transript]

Over 2,000 people gathered at Riverside Church in New York on Friday for the funeral of the legendary drummer, educator and activist Max Roach, who died on August 16 at the age of 83.

Maya Angelou, Bill Cosby, Amira Baraka, Sonia Sanchez and others credited Roach with helping to revolutionize the sound of modern jazz and for playing a prominent role in the struggle for black liberation at home and in Africa.

Max Roach was born in North Carolina in 1924, but he grew up in Brooklyn. His musical career began in the local Baptist church, and by the age of 16 he was playing with Duke Ellington. A few years later he helped lay the groundwork for bebop with Charlie Parker’s group. Over the next six decades he would remain at the forefront of creative music playing with such legendary figures as Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Cecil Taylor and Archie Shepp.

But to many Roach might be best remembered for a record he released in 1960 along with his future wife, the vocalist Abbey Lincoln.

The cover of the record showed a photograph of student activists from SNCC participating in a sit-in at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C.

Max Roach titled the record: “We Insist: Freedom Now Suite.” It remains one of the most moving musical pieces to come out of the black liberation movement.

At the time Max Roach told Down Beat magazine, "I will never again play anything that does not have social significance. ‘We American jazz musicians of African descent have proved beyond all doubt that we’re master musicians of our instruments. Now what we have to do is employ our skill to tell the dramatic story of our people and what we’ve been through.’’

In 1961, Max Roach staged a one-man protest on stage Carnegie Hall during a Miles Davis performance because the concert was a benefit for an organization supportive of the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Roach’s outspokenness led him to being blacklisted by some in the music industry but he continued to perform and compose into the 21st century.

Roach would also became a leading jazz educator and was the first jazz musician to win a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

Later in the show we will play excerpts of Bill Cosby and Maya Angelou speaking at Max Roach’s funeral but first we are joined by two guests both of whom have known Roach for decades.

Amiri Baraka, Max Roach’s biographer and acclaimed poet, playwright, music historian, and activist. In 1992, Baraka worked with Max Roach to compose an opera called “The Life and Life of Bumpy Johnson.”

Phil Schaap, award-winning jazz historian, radio host, and reissue producer. He is the host of “Bird Flight,” a daily radio program devoted to the music of Charlie Parker. Birdflight is broadcast on WKCR out of Columbia University at 89.9 FM. Schaap also teaches jazz history at the Lincoln Center in New York.

TRANSCRIPT:

AMY GOODMAN: Thousands of people gathered at Riverside Church in New York on Friday for the funeral of the legendary drummer, educator and activist Max Roach. He died on August 16 at the age of eighty-three.

Maya Angelou, Bill Cosby, Amiri Baraka, Sonia Sanchez and others credited Roach with helping to revolutionize the sound of modern jazz and for playing a prominent role in the struggle for black liberation at home and in Africa.

Max Roach was born in North Carolina in 1924, but grew up in Brooklyn. His musical career began in a local Baptist church. And by the age sixteen, he was playing with Duke Ellington. A few years later he helped lay the groundwork for bebop with Charlie Parker’s group. Over the next six decades, he would remain at the forefront of creative music playing with such legendary figures as Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, Cecil Taylor and Archie Shepp.

But to many, Max Roach might be remembered for a record he released in 1960 along with his future wife, the vocalist Abbey Lincoln. The cover of the record showed a photograph of student activists from SNCC participating in a sit-in at a lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. Max Roach titled the record We Insist! Freedom Now Suite. It remains one of the most moving musical pieces to come out of the black liberation movement.

At the time, Max Roach told Down Beat magazine, “I will never again play anything that does not have social significance. We American jazz musicians of African descent have proved beyond all doubt that we are master musicians of our instruments. Now what we have to do is employ our skill to tell the dramatic story of our people and what we’ve been through,” he said.

In 1961, Max Roach staged a one-man protest on stage, Carnegie Hall, during a Miles Davis performance, because the concert was a benefit for an organization supportive of the apartheid regime in South Africa.

Roach’s outspokenness led him to being blacklisted by some in the music industry, but he continued to perform and compose into the twenty-first century. Roach would also become a leading jazz educator and was the first jazz musician to win a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

Later in the program, we’ll play excerpts of Bill Cosby and Maya Angelou speaking at Max Roach’s funeral, but first we’re joined by two guests, both of whom have known Max Roach for decades. Amiri Baraka is an acclaimed poet, playwright, music historian and activist. He was the founder of the Black Arts Movement in Harlem in the ‘60s. In 1992 Amiri Baraka worked with Max Roach to compose an opera called The Life and Life of Bumpy Johnson. Phil Schaap also joins us. He’s an award-winning jazz historian, radio host and reissue producer. He’s the host of Bird Flight, a daily radio program devoted to the music of Charlie Parker on WKCR out of Columbia University in New York. Schaap also teaches jazz history at Lincoln Center in New York. Welcome, both, to Democracy Now!

Amiri Baraka, talk about the significance of Max Roach and how you came to meet him.

AMIRI BARAKA: Well, my first cousin, coming back from the Second World War, gave me these bebop records when I was about fourteen, I think it was.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain what bebop is?

AMIRI BARAKA: Bebob, well, let’s say that’s the—was the change of the music from the old swing era, you know, in the ’30s, and in the ’40s the musicians sort of reemphasized, you know, improvisation and the blues and the whole percussive underbelly of the music, because the music had become very, very—what would you call it—over-arranged. All of the swing bands began to sound the same. And so, small group of musicians began to create forms that, you know, were sort of lines of demarcation from regular swing music. And Max Roach is one of them.

Plus, Max tried to make the drum a uniquely voiced instrument, independent of the ensemble. He wanted to make a solo instrument. He wanted the drums to be part of the front line, rather than being, you know, hidden in the background. So when I first heard Max was a group called Max Roach and the Bebop Boys, which is God knows how long ago that was.

But it was part of this—what impressed me about what was called bebop, although Max used to complain about the terms “jazz” and “bebop” as being media-created, what impressed me is that, as a kid, it made me think of things that I have never thought before. You know, it was a sort of a freeing of your mind or making your mind actually dwell on things you had never even thought existed.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to play a clip of Max Roach. This was on WABC’s Like It Is. He was interviewed by Gil Noble, who asked him about his mastery of drumming.

MAX ROACH: Well, Gil, this instrument is totally different from any other percussion instrument on the face of the earth. And the technique for dealing with this instrument has added another dimension to the technique of dealing with percussion instruments generally. For example, this instrument, you deal with all four limbs. Most of these percussion instruments in the world that we see, whether they are in Europe, Africa, the Far East, they all play with just their hands. This instrument has added another dimension, and that’s your two feet.

And the basis of that is—I’ll give you an example. You play one thing with your right hand. You call this the swing beat. You play another thing with your base drum. That’s the four-four beat. Then you play another rhythm that’s totally different with your left hand. That’s the shuffle beat. Then with your left foot you play a Charleston beat. Now, in that sense, that’s the essence of this particular drum: you have to learn to deal with all four elements, and they have to blend together, similar to, say, a string quartet. You have to hear everything.

AMY GOODMAN: Max Roach on Gil Noble’s Like It Is on WABC in New York years ago. Phil Schaap, you’re smiling as you’re watching the late Max Roach.

PHIL SCHAAP: Well, it’s a great thing to hear that much jazz information in such a short instance. It’s also amusing to me, because I know who taught Max Roach that: Charlie Parker, at Max’s home, or his mother’s home, in Brooklyn. I guess it’s sixty-two or sixty-three years ago. Max Roach was late for the rehearsal at his own home. And Bird was sitting at the drums, and he said, “Max, can you do this, these four things? And you do them all at the same time, one limb for each event.” And that’s what Charlie Parker could do, and I’m pleased to see that Max Roach learned the lesson. I’m still working on it myself.

AMY GOODMAN: Phil Schaap and Amiri Baraka are with us. We’re spending the hour on Max Roach. Before he was thirty, he was voted the greatest jazz drummer in the world. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re spending the hour on the legendary jazz drummer Max Roach. On Friday, a funeral at the historic Riverside Church was held. Thousands of people came out. Renowned poet Maya Angelou spoke at the funeral for Max Roach.

MAYA ANGELOU: Family, family, family, when great trees fall, rocks on distant hills shudder, lions hunker down in tall grasses, and even elephants lumber after safety. When great trees fall in forests, small things recoil into silence, their senses eroded beyond fear. I have come to sing a song of praise to the courage of black men, in general, black American men, in general, and Max Roach, in particular.

I was the only parent of a young man, a young black man. James Baldwin, John Killens, Julian Mayfield, and Max Roach offered themselves to me as my brother, my brother friends. I was young and quite mad. And so were they. But they were brave enough to be brothers to an African American woman—that’s no small matter—an African American woman who has opinions and is not loathe to tell anybody her opinion at any time, loudly.

Max Roach and the other men I have mentioned dared to say to me things like, “Listen, what you said to your son—he was eleven—what you said to him last week wasn’t all that swift. In fact, that was dumb. You’re raising a black boy in a white country where—poor boy in a country where money is adored, where black is hated, and man—where a man is no small matter. It’s a difference between being an old male born with certain genitalia—you can be an old whatever that is, but to become a man, and an African American man, is no small matter. Help yourself.”

And then, on the other hand, he would call me from New York to California and say, “Girl, I’m so proud of you. I saw you on television. You were brilliant. I’m so proud to be your brother.”

Thanks to Max Roach and African American men, there are some single women who dare to be mothers, dare to be sisters, dare to be lovers, dare to be citizens.

Thanks to Max Roach, all forty years ago, his then-wife Abbey Lincoln, Rosa Guy and I decided we were going to storm United Nations. And we put it to some men. They said, “Don’t be silly.” And we said we’d get the African American—the Harlem community to come down there to United Nations. They said, “Don’t be silly. Those people have never been to Times Square.” Max Roach said, “Do it”—not only “Do it,” “I’ll go with you.” And we went. And Harlem turned up down at United Nations, and we made an international statement. Max Roach.

Max Roach encouraged me to marry a man, a South African freedom fighter who was at United Nations, who was madder than I was. Max Roach said, “He’s good for you. He’ll teach you a thing or two.” He taught me three or four things.

I have wept copiously after losing Max Roach. I also laugh uproariously, because he dared to love me without any sexual innuendos, without any of that, just loved me, told me I was brilliant, much like my own brother. He told me I was brilliant, smarter than most people. He also told me I wasn’t as smart as he was, which was true, which was true.

When great trees fall, it is wise, I think, for us to praise the ground they grew out of.

It is such a wonderful thing to look at his friends and family, to see great names here, great artists, who loved Max Roach, because he had the courage to love us. And so, I’m glad to say we had him. We are bigger and better and stronger, because Max Roach was my brother.

AMY GOODMAN: Maya Angelou remembering Max Roach at Riverside Church on Friday at the funeral of the great jazz legend.

In studio with us, Amiri Baraka and Phil Schaap. Phil, can you talk about the protest that Maya Angelou referred to at the UN, also the Newport Jazz Festival and the one you were at, the Miles Davis concert?

PHIL SCHAAP: Well, the Newport Jazz Festival, the Jazz Artists Guild, the Newport Rebels was the first. It was in July of 1960 and is a continuance of Max Roach’s feelings about the artists controlling, even owning and certainly directing, their own business, which relates initially to his running a record label with Charles Mingus called Debut. This was an expansion of that operation. Now they were going to run their own jazz festival. And they had a lot of musicians on the staff. I was talking with his trombonist Julian Priester on just Friday, and he said, “I was a ticket taker, and so was Mingus.”

And also the Newport festival, the actual Newport festival, was actually closed down by the authorities. There was a lot of—it’s hard to describe it at a distance of forty-seven years, but if you saw West Side Story, there was some youthful rebellion going on parallel to jazz rebellion. But the Max Roach-led festival continued and actually did better business, because they were the only game in town. And when they came back to New York after it, they decided to show that something of substance had happened up there and should be continued.

I remember Jo Jones, the drummer, used to take me to some of these events that they had on a loft. It was around 10th Avenue at West 51st Street, and I even saw some, I guess, previews of the Freedom Now Suite: We Insist! So that was about the Newport Rebels of 1960.

Then, the following year—one of Max Roach’s greatest insights about the contemporary Civil Rights Movement from an American perspective was that it was the same thing internationally, in that he felt that the rebellion against imperialism and apartheid in South Africa and the contemporary Civil Rights Movement here in the United States was one thing, and it’s a blended theme that he puts across brilliantly in his music. And he felt that, well, among other people, the great Miles Davis was too centered on whatever he was doing for the Civil Rights Movement in the States wasn’t even addressing the real issue, which was international. So he decided he was going to make his own rebellion single-handed on stage at Carnegie Hall.