SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2022

VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER THREE

MARC CARY

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

REVOLUTIONARY ENSEMBLE

(June 11-17)

OLU DARA

(June 18-24)

WALTER SMITH III

(June 25-July 1)

BOBBY WATSON

(July 2-8)

JAMES MOODY

(July 9-15)

RONALD SHANNON JACKSON

(July 16-22)

LEYLA McCALLA

(July 23-29)

RUSSELL MALONE

(July 30-August 5)

GREG LEWIS

(August 6-12)

JOHN HANDY

(August 13-19)

STANLEY CLARKE

(August 20-26)

JASON HAINSWORTH

(August 27-September 2)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/russell-malone-mn0000808613/biography

Russell Malone

(b. November 8, 1963)

Biography by Matt Collar

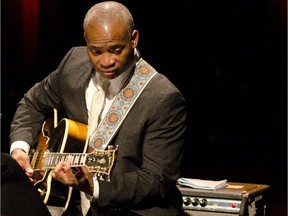

An adept jazz guitarist with a clean attack and fluid, lyrical style, Russell Malone often plays in a swinging, straight-ahead style, weaving in elements of blues, gospel, and R&B. Born in Albany, Georgia in 1963, Malone first began playing guitar around age four on a toy instrument, quickly graduating to the real thing. Largely self-taught, he initially drew inspiration listening to the recordings of gospel and blues artists including the Dixie Hummingbirds and B.B. King. However, after seeing George Benson perform with Benny Goodman on a television show, Malone was hooked on jazz and began intently studying albums by legendary guitarists like Charlie Christian and Wes Montgomery.

By his twenties, Malone was an accomplished performer, and in 1988 he joined organist Jimmy Smith's band. Soon after, he also became a member of Harry Connick, Jr.'s big band, appearing on Connick's 1991 effort Blue Light, Red Light. With his growing reputation as a sideman, Malone next caught the attention of pianist/vocalist Diana Krall, with whom he would work throughout much of the '90s and 2000s. Also during this period, Malone appeared with a bevy of name artists including Branford Marsalis, Benny Green, Terell Stafford, Ray Brown, and others.

As a solo artist, Malone made his debut with 1992's Russell Malone, followed a year later by Black Butterfly. In 1999, he released Sweet Georgia Peach, which featured a guest appearance from pianist Kenny Barron. Malone kicked off the 2000s with several albums on Verve, including 2000's Look Who's Here and 2001's orchestral jazz-themed Heartstrings. He then moved to Maxjazz for 2004's Playground, featuring a guest appearance from saxophonist Gary Bartz, followed by 2010's Triple Play.

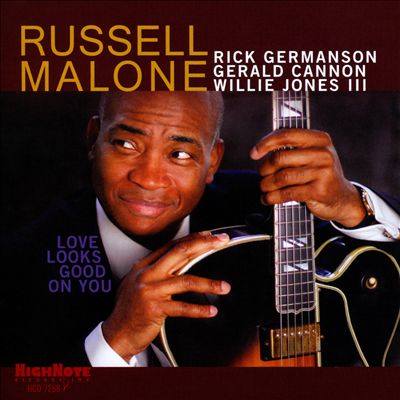

Over the next several years, Malone appeared on albums by Wynton Marsalis, Christian McBride, and Ron Carter, as well as Krall bandmate bassist Ben Wolfe. He returned to solo work in 2015 with the eclectic small-group album Love Looks Good on You, followed a year later by All About Melody, both on HighNote. In 2017, he delivered his third HighNote album, Time for the Dancers, featuring his quartet with pianist Rick Germanson, bassist Luke Sellick, and drummer Willie Jones III.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/russell-malone

Russell Malone

Russell Malone's first guitar was a plastic green toy his mother bought him. Only four years old, Malone strummed the little guitar all day long for days on end trying to emulate the sounds he had heard from guitarists at church in Albany, Georgia. As a child, Malone developed an interest in blues and country music after seeing musicians on television like Chet Atkins, Glen Campbell, Johnny Cash, Roy Clark, Son Seals, and B.B. King. Then, at age 12, he saw George Benson perform with Benny Goodman on Soundstage. Malone has said, "I knew right then and there that I wanted to play this music."

A self-taught player, Malone progressed well enough to land a gig with master organist Jimmy Smith when he was 25. "It made me realize that I wasn't as good as I thought I was," Malone recalls of his first on-stage jam with Smith. After two years with Smith, he went on to join Harry Connick Jr.'s orchestra, a position he held from 1990-94, appearing on three of Connick''s recordings. Malone also worked in a variety of contexts, performing with artists as diverse as Clarence Carter, Little Anthony, Peabo Bryson, Mulgrew Miller, Kenny Barron, Roy Hargrove, Branford and Wynton Marsalis, The Winans, Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, Bucky Pizzarelli, and Jack McDuff.

Malone is one of the most commanding and versatile guitarists performing. He can move from blues to gospel to pop to R&B and jazz without hesitation, a rare facility that has prompted some of the highest profile artists in the world to call upon him: Diana Krall, Gladys Knight, Aretha Franklin, B.B. King, Natalie Cole, David Sanborn, Shirley Horn, Christina Aguilera, Harry Connick, Jr, Ron Carter, and Sonny Rollins.

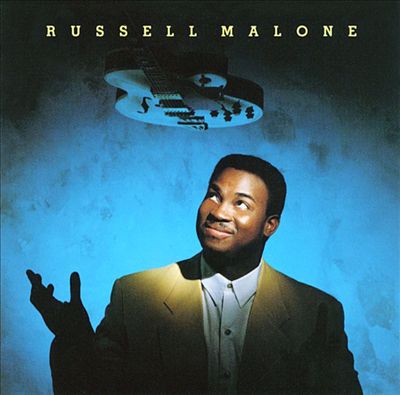

Along the way, Malone has made a name for himself combining the bluesy sound of Grant Green and Kenny Burrell with the relentless attack of Django Reinhardt and Pat Martino. After hearing Malone play in Connick's band, former Sony head, Tommy Mottola, brought Malone over to Columbia. Malone's self-titled debut, Russell Malone, in 1992 quickly went to #1 on the radio charts. This album has Malone playing Electric, Acoustic, and Classical guitars. It also features Harry Connick Jr. on piano, his current employer at the time, joking around on "I Don't Know Enough About You," a vocal piece by Malone, not Connick.

Russell Malone was quickly followed by his second album, Black Butterfly in 1993, with Paul Keller on Bass, who later became his trio mate with Diana Krall. Diana Krall's label, Verve Records, came calling next and released three albums by Malone: Sweet Georgia Peach (1998), Look Who's Here (2000), and Heartstrings (2001). Hearstrings features a full orchestra with arrangements by Johnny Mandel, Don Caymmi, and Alan Broadbent, accompanied by the all-star rhythm section team of Kenny Barron (piano), Christian McBride (bass), and Jeff "Tain" Watts (drums).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russell_Malone

Russell Malone (born November 8, 1963) is an American jazz guitarist. He began working with Jimmy Smith in 1988 and went on to work with Harry Connick, Jr. and Diana Krall throughout the 1990s.

Biography

Malone was born in Albany, Georgia, United States. He began playing at the age of four with a toy guitar his mother bought him. He was influenced by B.B. King and The Dixie Hummingbirds.[2] A significant experience was when he was twelve and saw George Benson perform on television with Benny Goodman. He is mostly self-taught.[3][4]

Starting in 1988, he spent two years with Jimmy Smith, then three with Harry Connick Jr. In 1995, he became the guitarist for the Diana Krall Trio,[3] participating in three Grammy-nominated albums, including When I Look in Your Eyes, which won the award for Best Vocal Jazz Performance. Malone was part of pianist Benny Green's recordings in the late 1990s and 2000: Kaleidoscope (1997), These Are Soulful Days (1999), and Naturally (2000). The two formed a duo and released the live album Jazz at The Bistro in 2003 and the studio album Bluebird in 2004. They toured until 2007.

Malone has toured with Ron Carter, Roy Hargrove, and Dianne Reeves and has done session work with Kenny Barron, Branford Marsalis, Wynton Marsalis, Jack McDuff, Mulgrew Miller, and Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson. He recorded his first solo album in 1992 and has led his own trio and quartet.[3] Other guest appearances have included Malone with vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, organist Dr. Lonnie Smith, and pianist Hank Jones in celebration of his 90th birthday. In October 2008 he performed in a duo with guitarist Bill Frisell at Yoshi's in Oakland, California. During the next year, Malone became a member of the band for saxophonist Sonny Rollins, celebrating his 80th birthday in New York City.

Malone recorded live on September 9–11, 2005, at Jazz Standard, New York City, and Maxjazz documented the performances on the albums Live at Jazz Standard, Volume One (2006) and Live at Jazz Standard, Volume Two (2007). Appearing on these two volumes, and touring as The Russell Malone Quartet, were Martin Bejerano on piano, Tassili Bond on bass, and Johnathan Blake on drums. Malone's 2010 recording Triple Play (also on Maxjazz) featured David Wong on bass and Montez Coleman on drums. His album, All About Melody featured pianist Rick Germanson, bassist Luke Sellick, and drummer Willie Jones III.[5][6]

Discography

As leader

- Russell Malone (Columbia, 1992)

- Black Butterfly (Columbia, 1993)

- Sweet Georgia Peach (Impulse!, 1998)

- Look Who's Here (Verve, 2000)

- Heartstrings (Verve, 2001)

- Ray Brown Monty Alexander Russell Malone (Telarc, 2002)

- Jazz at the Bistro with Benny Green (Telarc, 2003)

- Playground (Maxjazz, 2004)

- Bluebird with Benny Green (Telarc, 2004)

- Live at Jazz Standard Vol. One (Maxjazz, 2006)

- Live at Jazz Standard Vol. Two (Maxjazz, 2007)

- Triple Play (Maxjazz, 2010)

- Love Looks Good on You (HighNote, 2015)

- All About Melody (HighNote, 2016)

- Time for the Dancers (HighNote, 2017)

As guest

With Ray Brown

- Some of My Best Friends Are...Singers (Telarc, 1998)

- Christmas Songs with the Ray Brown Trio (Telarc, 1999)

- Some of My Best Friends Are...Guitarists (Telarc, 2002)

With Harry Connick Jr.

- We Are in Love (Columbia, 1990)

- Blue Light Red Light (Sony, 1991)

- When My Heart Finds Christmas (Columbia, 1993)

With Benny Green

- Kaleidoscope (Blue Note, 1997)

- These Are Soulful Days (Blue Note, 1999)

- Naturally (Telarc, 2000)

With Diana Krall

- All for You: A Dedication to the Nat King Cole Trio (Justin Time, 1996)

- Love Scenes (Impulse!, 1997)

- Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas (Impulse!, 1998)

- Diana Krall (Verve, 1999)

- When I Look in Your Eyes (Verve, 1999)

- The Look of Love (Verve, 2001)

- Christmas Songs (Verve, 2005)

- Turn Up the Quiet (Verve, 2017)

- This Dream of You (Verve, 2020)

With Houston Person

- Soft Lights (HighNote, 1999)

- Sentimental Journey (HighNote, 2002)

- The Art and Soul of Houston Person (HighNote, 2008)

With David Sanborn

- Timeagain (Verve, 2003)

- Closer (Verve, 2005)

- Here & Gone (Decca, 2008)

With others

- Mose Allison, Gimcracks and Gewgaws (Blue Note, 1998)

- Kenny Barron, Spirit Song (Verve, 2000)

- Gary Bartz, The Blues Chronicles (Atlantic, 1996)

- Stefano di Battista, Trouble Shootin' (Blue Note, 2007)

- David Benoit, Here's to You Charlie Brown (GRP, 2000)

- Don Braden, Organic (Epicure, 1995)

- Gary Burton, For Hamp, Red, Bags, and Cal (Concord Jazz, 2001)

- Regina Carter, Motor City Moments (Verve, 2000)

- Ron Carter, The Golden Striker (Blue Note, 2003)

- Cyrus Chestnut, Genuine Chestnut (Telarc, 2006)

- The Chieftains, Tears of Stone (RCA Victor, 1999)

- Jimmy Cobb, Jazz in the Key of Blue (Chesky, 2009)

- Natalie Cole, Ask A Woman Who Knows (Verve, 2002)

- Will Downing, Sensual Journey (Verve, 2002)

- Jon Faddis, Teranga (Koch, 2006)

- Macy Gray, Stripped (Chesky, 2016)

- Dave Grusin, Two for the Road (GRP, 1997)

- Roy Hargrove, Habana (Verve, 1997)

- Vincent Herring, Hard Times (Smoke Sessions, 2017)

- Shirley Horn, You're My Thrill (Verve, 2001)

- Freddie Hubbard, On the Real Side (Four Quarters, 2008)

- Etta Jones, All the Way (HighNote, 1999)

- B. B. King, Let the Good Times Roll (MCA, 1999)

- Gladys Knight, Before Me (Verve, 2006)

- Jeff Lorber, He Had a Hat (Blue Note, 2007)

- Branford Marsalis, I Heard You Twice the First Time (Columbia, 1992)

- Christian McBride, A Family Affair (Verve, 1998)

- Bill Mobley, Hittin' Home (Space Time, 2016)

- New York Voices, New York Voices Sing the Songs of Paul Simon (RCA Victor, 1998)

- Johnny O'Neal, On the Montreal Scene (Justin Time, 1996)

- Kenny Rankin, A Song for You (Verve, 2002)

- Tony Reedus, People Get Ready (Sweet Basil, 1998)

- Dianne Reeves, The Calling (Blue Note, 2001)

- Dianne Reeves, When You Know (Blue Note, 2008)

- Sonny Rollins, Road Shows, Vol. 2 (EmArcy, 2011)

- Stephen Scott, The Beautiful Thing (Jazz Heritage, 1997)

- Janis Siegel, The Tender Trap (Monarch, 1999)

- Janis Siegel, Friday Night Special (Telarc, 2003)

- Terell Stafford, Centripetal Force (Candid, 1997)

- Joss Stone, Colour Me Free! (Virgin, 2009)

- Jimmy Smith, Dot Com Blues (Blue Thumb, 2000)

- Billy Taylor, Taylor Made at the Kennedy Center (Kennedy Center Jazz 2005)

- Steve Turre, Delicious and Delightful (HighNote, 2010)

- Steve Turre, Kenny Barron, The Very Thought of You (Smoke Sessions, 2018)

- Gerald Wilson, In My Time (Mack Avenue, 2005)

Interview with Jazz Guitar Life – Part I

Russell Malone Strikes While It’s Hot! An Exclusive Interview with Jazz Guitar Life – Part I

First of all, it was his music. I mean, I started listening to jazz when I was 12. My first records were records. My first guitar records were records by George Benson, Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell. And Ron Carter was on a whole lot of those records. And I bought the records because of the guitar players, but there was something about the bass player, something about his personality that just made me listen to him and to what he was doing, because it seems as if—and this is not just on those records, but a whole lot of other records that he’s on—everything seems to revolve around what he’s doing…

Russell Malone

Russell Malone is, without a doubt, one of the most legendary jazz guitarists of our time. His studio recordings and live performances as both solo artist and sideman have earned him the reputation the consummate musician—one of the highest honors that bestowed upon those of his caliber. When JGL’s own Dr. Wayne Goins called him from Manhattan (Kansas!) during the early days of March, Russell was preparing to leave Manhattan (New York!) the next day—headed to Chicago to participate in a tribute to Les Paul the following day. Ever the gentleman, Malone still took time out of his busy schedule to share his experience with us—and what a unique story he has to tell!

So sit back, relax, and enjoy our exclusive interview with the one and only Russell Malone – Dr. Wayne Goins

As a one-man operation, if you would like to support all the work I do on Jazz Guitar Life, please consider buying me a coffee or two. Your support helps me to focus on Jazz Guitar Life so that I can continue to bring you great interviews, reviews, podcasts and other related Jazz Guitar content. Thank you and your patronage is greatly appreciated regardless if you buy me a coffee or not – Lyle Robinson

…………….

JGL: I know you don’t do a lot of interviews, and you’re very selective about who you share your time and energy with, so I really appreciate you taking the time to do this for me and Jazz Guitar Life.

RM: No problem, Wayne.

JGL: While preparing for this exclusive interview I’ve been trying to decide on what end of your long and storied career I wanna start with! But I think I should start with more current events and then we can work our way backwards. Let’s start with what’s happening right now. So, what have you been up to lately? I know you’ve been doing some things recently with the Golden Striker Trio featuring the legendary bassist Ron Carter, yes?

RM: Yes. Yes. it’s actually Ron’s group. He put it together back in 2002, and the band started out with myself on guitar, Ron Carter, and Mulgrew Miller on piano. He started the band with Mulgrew, and Mulgrew stayed there for a while. And then he [Miller] left about a year or two before he passed, because he wanted to focus more on his own career. But I’ve been playing with that band for over ten years now.

JGL: Wow, I didn’t know that.

RM: Yeah…then Mulgrew died and then Donald Vega—who’s in the band now—he came in, and took Mulgrew’s place.

JGL: I had never heard of that guy’s name until I started doing research on this Ron Carter trio. He’s playing his ass off!

RM: Oh, Donald’s an excellent piano player, man. He’s fantastic. He came in and he just, you know, he just took to it like a fish to water. When Mulgrew passed, not only did it leave a void in that trio, but it left a void, because he was such a strong presence on the jazz scene…and we all miss him.

JGL: I reached out to Ron Carter’s people and asked them to let him know I was going to write an article on the Golden Striker Trio history for one of the music magazines I write for. Sure enough, Ron Carter called me, and we talked for about two hours—I was thrilled beyond measure.

RM: Oh, that’s fantastic. Well, you know Ron’s not the most talkative guy, but if you ask him the right questions and, if he feels comfortable with you, you will get more information than you bargained for, man ’cause he’s got a lot of information to share.

JGL: How did you get with Ron? How long have you known him?

RM: The first time I saw Ron Carter play was in Atlanta, Georgia. It was back in the mid-80’s and Ron Carter came through town. I can’t remember the venue, but it was over on Peachtree in Buckhead. Ron Carter was doing a duo concert with Jim Hall—and Joe Pass opened up for them that night!

JGL: Woah!

RM: Yeah. And the music was amazing, man. After the show was over, I got to meet everybody just very briefly. I shook Joe Pass’s hand. I shook Ron Carter’s hand and I shook Jim Hall’s hand, then I split. But I met him [Ron] again in New York—when I moved there. He was playing at a place up here called the Knickerbocker. It was him, pianist James Williams and drummer Tony Reedus. They were playing, and, you know, I got a chance to meet him there and reintroduce myself. And I would see him around New York playing in other places. And I didn’t expect him to remember me after that. I was just some guy shaking his hand and telling him how much I appreciated the music. Then in 1995, I got called to participate in this movie by Robert Altman called Kansas City—you remember that movie?

JGL: Absolutely—that scene you were in was awesome!

RM: So we were at the airport collecting our bags at baggage claim. It was me and Nicholas Payton and a whole bunch of other musicians–Olu Dara, a whole bunch of us. So we collected our luggage and we went outside to stand on the curb, waiting on the vehicle to pick us up and take us to the hotel. So we’re just standing there talking and shooting the breeze. And all of a sudden I hear somebody called my name and they were like, “Russell Malone, come on, let’s go. We gotta go! We gotta get to the hotel. You guys are messing around, over there!” And I turned around and it was Ron Carter, he was sitting in the van! [laughs.]

JGL: Wow! [more laughter.]

RM: And I was like, ‘man, Ron Carter knows who I am?’ He called my full name. I said to myself, ‘Ron Carter knows me?? Cool!!’ So we got in the van, and I sat next to him and we talked and we went on over to the hotel, and checked in. I had had dinner with him later on that night and we just sat and talked some more. The next morning we got up “before the chickens,” so to speak, to start shooting for the film. Once the film shoot was done he started calling me for gigs, man!

JGL: How cool!! Where did y’all play?

RM: The first gig he called me for was at the Museum of Modern Art; and on the gig was me, him, pianist Stephen Scott, saxophonist Houston Person and drummer Lewis Nash. I was like, ‘wow, this is incredible, man.’ I’d always wanted to play with Houston. I’d always loved his playing. And Lewis Nash can do no wrong as far as I’m concerned. And that was my first time playing with Stephen Scott and we just had a ball! So Ron Carter started called me for another gig at MOMA. This time. It was with… I think Lewis was still playing drums, Stephen Scott was still on piano, but this time Jesse Davis was the horn player. So, you know, I did about two or three more of those types of gigs with him at MOMA. And then he started calling me for other stuff. And then I called him for my recording, Sweet Georgia Peach.

JGL: Oh, that’s awesome. Nice to have an opportunity to return the favor!

RM: Yeah, and so I’ve been playing with Ron Carter off and on since 1995, more than 25 years, man.

JGL: What do you think he saw in you that made him so comfortable to gravitate towards you that way?

RM: Well, I think it might have been the fact that I gave him the respect that he is entitled to—first of all—as an older gentleman, because he’s a man. He’s a man first before he is a musician.

JGL: Yeah, that’s right.

RM: And I gave him that respect, you know, because I grew up in the South, man. You know, we were always taught to give respect and honor to our elders.

JGL: Yep!

RM: And I gave it to him, you know. First of all, I didn’t just walk up to him. I didn’t call him Ron. I didn’t. I called him Mister…Mr. Carter. Or I called him, “Mr. C.” I’ve never addressed him as Ron. I would never do that to any older adult. So I addressed him, you know, respectfully. So to answer your question, he must have sensed that I was serious about the music. I mean, maybe that’s what drew him to me. I don’t know. But that’s what I’m thinking.

JGL: I think I’m pretty sure it was that, but I think there may be another level added to it, that I don’t think can be separated. I think from a musical standpoint, he may have assessed something in you in terms of your respect for the history of the legacy of jazz guitar—that he might have seen or heard something in you that might have made him think, ‘this dude has done his homework in that regard; he might be worth investing in.’ Because, you know, as you get older, you [Carter] kind of are already thinking about how to pass it on to the next generation, which would, in fact, be YOU, Russell. What do you think about that part of it?

RM: Well, you know, you would probably have to ask him about what drew him to me. I’m just thinking that it was because I was so respectful to him. Maybe that’s what it was, but you would probably get a better answer if you asked him…[pause]…but I can tell you what made me gravitate towards him. I can definitely tell you what made me gravitate towards Ron.

JGL: By all means, do tell!

RM: First of all, it was his music. I mean, I started listening to jazz when I was 12. My first records were records. My first guitar records were records by George Benson, Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell. And Ron Carter was on a whole lot of those records. And I bought the records because of the guitar players, but there was something about the bass player, something about his personality that just made me listen to him and to what he was doing, because it seems as if—and this is not just on those records, but a whole lot of other records that he’s on—everything seems to revolve around what he’s doing. And one of the things that I’ve picked up on having played with him for so long is, it taught me how to listen to the bass, not just hear the bass, but to listen to the bass. And we’ve had several conversations about listening, and he always talked about the importance of trusting the band that you’re in, and listening to the band that you’re in, particularly the bass player. Because he told me that one of the things that was a pet peeve of his was this: A lot of people who were on the front line, a lot of horn players, they hear the bass, but they don’t really listen to the bass. And he said that they treat the rhythm section as if it’s some Jamey Aebersold practice thing, you know—to practice to instead of just interacting right with what’s going on.

JGL: Right!

RM: Hearing him say that really resonated with me. So when I started playing with him I started to really hone in on what he was doing.

JGL: I can dig it.

RM: Oh, and something else that was eye opening too: When I bought those Miles records? My first Miles Davis record was Live at the Plugged Nickel—you know that record?

JGL: Oh yeah, yeah!

RM: Boy, they’re just throwing caution to the wind on that recording, man! But I was listening to that record and some of the other recordings like ESP, all the Miles Records that Ron Carter played on. And me at the time—being as naive as I was—I’m listening to Herbie Hancock and listening to all of this crazy harmony, those crazy harmonies that he was playing. I’m like, ‘man, this piano player, he’s really something else!’ But once I started to play with Ron Carter, I had to rethink that notion. Because I strongly feel that a lot of the harmonic direction in that band…I feel that Ron Carter—after having played with him—he was the instigator.

JGL: Wow.

RM: Yes! For where that music went harmonically…because he does that. He does that in his band. He just—you just never know what’s gonna happen. He never knows what’s gonna happen, but he always knows why it’s gonna happen. See, the thing that’s so cool about playing with him is that everything has a place and a purpose, and he never…he may not always know what he’s gonna do, but when he does it, he always knows why he does it.

JGL: Right.

RM: There’s never any randomness going on there.

JGL: Right.

RM: So playing with him has been really wonderful for me. And every now and then I have to—when I’m on the bandstand with him—I have to pinch myself to make sure that it’s not a dream, because I mean, here’s a guy that’s played with Wes Montgomery! All my guitar idols…he’s played with most of them.

JGL: Yeah.

RM: And you know, I get the same feeling about playing with Ray Brown!

JGL: I’m sure!

RM: Yeah, I’ve been spoiled man. I’ve gotten the chance to spend time with some really wonderful bass players. And Ron Carter and Ray Brown are two very important bass players in this music.

Part 2 with Russell Malone coming soon.

About the interviewer:

Dr. Wayne Everett Goins, University Distinguished Professor of Music (2015), is the Director of Jazz Studies in the School of Music, Theater, & Dance at Kansas State University, where he conducts big bands and teaches combos, private guitar lessons, jazz theory and jazz improvisation courses. He is also a prolific writer and published author many times over. For more detailed information please click here.

https://tedpanken.wordpress.com/category/russell-malone/

Category Archives: Russell Malone

For Russell Malone’s 55th Birthday, A Jazziz Article From 2016 and a Downbeat Blindfold Test From 2005

For master guitarist Russell Malone’s 55th birthday, here’s a feature profile that I wrote about him in the fall 2016 issue of Jazziz, and the proceedings of a Blindfold Test that we did for Downbeat in 2004.

Russell Malone, Jazziz, 2016:

Before settling into the formalities of an interview in the kitchen of his Jersey City row house, Russell Malone, Southerner that he is, decided to feed his guest. First he prepared ginger lemonade, a 20-minute procedure that included eight squeezed lemons, a lot of ginger, and agave for sweetener. Then Malone shaved daikon, cooked sushi rice infused with butter, fixed a ponzu sauce, seared some pea-shoot greens with garlic and, finally, broiled two slabs of salmon.

Malone worked methodically, washing and drying the dishes and utensils after each stage of the process. He was dressed well — cream-colored linen slacks; a forest green shirt from Thailand with gold brocading, untucked — but didn’t wear an apron. We spoke as he cooked, and continued to speak as we ate lunch, trading opinions and scurrilous gossip, discussing family and mutual acquaintances. Ninety minutes later, it almost seemed a shame to turn on the digital voice recorder.

The subject at hand was Malone’s spring release, All About Melody (High Note), on which the 53-year-old guitarist and his quartet — pianist Rick Germanson, bassist Luke Sellick and drummer Willie Jones III — address an American Songbook ballad; two American Soulbook torch songs; a spiritual; and originals by jazz icons Freddie Hubbard, Jimmy Heath, Bob Brookmeyer, Bill Lee and Sonny Rollins. Malone also presents his own ballad, “Message to Jim Hall,” directly followed by a brief voicemail from the late iconic guitarist.

Neither notions of high concept nor narrative arc inform the program, Malone says, not even his decision to follow his dedication to Hall, who famously played on several early-’60s recordings by Rollins, with Rollins’ “Nice Lady,” which Malone learned while touring with the saxophonist in 2010. “Those songs are fun to play,” he says. “When I make a record, I want the songs to flow naturally, to hold your attention, just like playing a set in a club.” He affirmed his close friendship with Hall. “Jim would call to tell you how he felt about you,” Malone says. “He was big on taking the time, effort and thought to write a letter, get the stamp, put it on the envelope, and mail it. I have a stack of his handwritten letters. I didn’t get around to writing Jim a letter, but I did get around to writing that tune for him.”

For a unifying thread, Malone suggested the title, edited from HighNote proprietor Joe Fields’ suggestion, “It’s All About the Melody,” which, he says, seemed too preachy and dogmatic.“This could have titled any of my other records, because that’s always been my attitude,” Malone says, before fleshing out the core aesthetic principle that infuses his previous 11 leader recordings since 1992 and numerous sideman or collaborative appearances with — to name a roughly chronological short list — Jimmy Smith, Harry Connick, Diana Krall, Benny Green and Christian McBride, Ray Brown, Dianne Reeves, Ron Carter and Rollins.

“I’m as influenced by singers as by instrumentalists, and whenever I learn a song, particularly a standard or a ballad, I listen to a vocalist’s rendition,” he says. “I want to learn not just the harmonic structure, but the story, the lyrics — everything. Those things go through my head when I play them. I try to sing through my instrument.”

In that regard, Malone mentions his unaccompanied reading of Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman,” which he heard growing up in Albany, Georgia. “If you noticed, I only played the melody,” he says. “Sometimes a strong melody, good changes and a good story is enough. That’s my thing these days.”

Malone adhered unstintingly to this stated criteria for song selection and play-your-feelings interpretation on both All About Melody and its 2014 HighNote predecessor, Love Looks Good On You. The latter date transpired four years after Triple Play, a trio recital that was Malone’s only studio recording during a six-year, four-CD run with MaxJazz, a fine boutique label that ceased operations after the death of its owner, Richard McDonnell.

“I was working so much, it wasn’t a priority to do a record if nobody would get behind it,” Malone explains. Several labels suggested he join their roster, but none followed up. “My attitude was: Your loss; if you ignore me, I’ll keep forging ahead. Then Joe Fields contacted me. People who’ve worked with him told me he’d support the records. Joe seemed to be the only guy interested in someone who plays like I do.”

He referenced the phrase “interview music,” coined by pianist Mulgrew Miller, Malone’s dear friend and colleague from before the guitarist moved to New York from Atlanta in the late ’80s until Miller died in 2013. “Certain musicians talk a good game, and sound deep and interesting, and it gets over,” Malone says. “But writers don’t consider people who play like me as cutting edge. Players who adopt a Eurocentric perspective — devoid of melody, swinging, blues and, heaven forbid, any black elements — are described as pushing the music forward. That’s complete bullshit to me.”

He recalled a brunch gig with organist Trudy Pitts in Philadelphia around 1990, playing tunes for “older people who wanted to hear some melodies.” One of Malone’s core influences, Kenny Burrell, working in town, was in the house. So were a group of college students. “Whenever I played something a little outside or rebellious to what was going on, these kids went, ‘Yeah, man — whoo-oo!’ Instead of thinking about the music, I started to think about impressing them with my crazy, dissonant shit.”

After the set, the admirers offered compliments: “Yeah, you were really pushing the envelope; you’re taking it out.” Malone thanked them, proceeded to Burrell’s table, and sat down. Malone recounts: “I had the nerve to say, ‘Hey, Mr. Burrell, you hear what I’m working on?’ He put his arm around me, and started chastising me like I was his son. He told me that what I’d played may have worked well in another situation, but it didn’t work here. You have to play what the situation calls for, which means allowing yourself to be vulnerable. Any time you’re playing to prove something, it’s not honest. I never forgot that. And I never did that again.”

[BREAK]

“I am flexible,” Malone says. “I take pride on being open enough to play with anybody.” He’s played “Moon River” and “The Christmas Song” with Andy Williams on The Mike Huckabee Show. He’s shared stages with B.B. King, Aretha Franklin and Natalie Cole; channeled the pioneering electric guitarist Eddie Durham in Robert Altman’s Kansas City; played the blues with Clarence Carter and raised a joyful noise with the Gospel Keynotes. He’s played high-level chamber jazz with Ron Carter and supported Dianne Reeves in a two-guitar format with Romero Lubambo. He’s rehearsed outcat projects with Bill Frisell and James “Blood” Ulmer. He visited Ornette Coleman’s loft once for a marathon of shedding.Malone grew up in a Pentecostal church, where he discovered the guitar. He traces his openness to the experience of playing it there from age 6 to 18. “It fascinated me how these church mothers singing spirituals would move people to tears, or to get the Holy Ghost and shout in response,” he says. “That’s when I started to really listen — the singers might start singing in any key, and not always at the same time, so I learned to be flexible throughout the guitar neck.”

As he entered his teens, Malone memorized his first guitar solo from Howard Carroll of the Dixie Hummingbirds, had “epiphanies” from B.B. King and from “country” guitarists like Chet Atkins and Merle Travis on Glen Campbell’s TV show. In 1975, “on a school night when I should have been in bed,” he saw George Benson play “incredible things” on “Seven Comes Eleven” on a PBS homage to John Hammond “that let me know there was a whole other level to aspire to.” Malone soon purchased The George Benson Cookbook and the double-LP Benson Burner. “A gentleman in my church who played guitar noticed that I was trying to play this stuff,” he continues. “He liked Wes Montgomery, and he laid Smokin’ At the Half Note and Boss Guitar on me. Those four records set me on a course that I have not deviated from.”

That course followed autodidactic pathways. “I had enough sense to know that something triggered George Benson’s interest in playing guitar like that,” Malone says. “I read that George was influenced by Charlie Christian, then that Charlie Christian was influenced by Eddie Durham and Lester Young, and had influenced Johnny Smith, Barney Kessel, Tal Farlow and so on. I didn’t have skills to write anything down, and I never transcribed a solo. I like the way I learned because I trust my ears. I’d pick things up and remember them.” He sought advice from lesser players who understood theory, as, for example, when he saw “Misty” in the Real Book, spotted an E-flat-major-VII chord, and asked a roommate to play it. “I said, ‘Oh, that’s what I’ve been playing all along.’ From there, I learned how to identify what I saw on paper. I still ask questions.”

After garnering experience on chitlin’ circuit revues that included Bobby Rush and Johnnie Taylor, Malone spent much of 1983 in Houston with Hammond B3 practitioner Al Rylander. In 1985, just before he turned 22, he moved to Atlanta, where he quickly established bona fides on transitory engagements with Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, Little Anthony, Peabo Bryson and O.C. Smith. In 1986, he joined Freddy Cole, who offered a master class in the nuances of blending with a singer before firing Malone after several months because, the guitarist recalls, “I wasn’t there yet.”

Malone first visited New York in 1985. He promptly received a lecture on the virtues of sonic individualism from bassist Lonnie Plaxico after they played “Stablemates” at Barry Harris’ Jazz Cultural Theater. “I respected Lonnie, because he’d played with Art Blakey and Dexter Gordon,” Malone says. “He asked where I was from. He said, ‘Yeah, you’ve got good tone, good feeling, and you really hear those changes.’ Then he said, ‘I hear that you like Wes and George and all those guys. You might be able to get away with playing like them in Atlanta, but not here. Those guys were able to break through because they didn’t come here trying to sound like somebody else. They had their own thing, and people eventually caught on.’”

Two years later, Jimmy Smith took an Atlanta engagement, and invited the local hero to sit in for a blues, “The Sermon.” “After the head, I played all my pet licks and generated some superficial excitement,” Malone says. “Then Jimmy went into a ballad, ‘Laura,’ which I didn’t know. You can’t just hear your way through it, because it moves harmonically, with a lot of twists and turns. That’s when I found out I wasn’t nearly as good as I thought. After he’d finished embarrassing me, Jimmy got on the microphone and said, ‘Whenever youngsters sit in with us, we like to make sure they learn something.’ He looked at me. ‘Now, did you learn something, young man?’”

After that set, Malone approached Smith at the bar to thank him for the opportunity. Smith, a black belt, turned and stuck his index finger in Malone’s solar plexus. “Let me tell you something,” Smith said, finger still in place. “I knew all those guys you’re trying to play like, and I also taught them. Don’t ever get on my bandstand with that bullshit again.” Then he invited Malone to his hotel room to play for him, telling the youngster about his life and experiences until 6:30 in morning. A year later, Smith hired Malone for his Southern and Midwestern tours.

“I’ve been around a lot of the older guys,” Malone says, reflecting on a cohort of associations that includes Smith, Rollins, Hall and Ron Carter. Another mentor was guitarist John Collins, who replaced Oscar Moore with the Nat King Cole Trio after quality time with, among others, Fletcher Henderson and Art Tatum. “John saw Andrés Segovia when he was a serviceman in World War Two, and remembered that he played the whole guitar, compared to young guitar players who focus on single lines like a horn player,” Malone says. “There’s nothing wrong with that, but you’re selling the instrument short. In the right hands, it can function as an orchestra. I never forgot that.”

He cited an encomium from Benny Carter, who was 94 when he heard Malone play his “All About You” on Marion McPartland’s Piano Jazz. “Benny told me he liked the way I treated ballads and my own songs because I respect the melody and don’t treat them like blowing vehicles,” Malone says. Dr. Billy Taylor — who himself sat at the feet of Willie “The Lion” Smith, Duke Ellington and Art Tatum during formative years — learned Malone had been spending quality time with Carter. He said: “You’ve been around the real guys, doing it the right way, the way we did it coming up. You know what’s up. Nobody can come along and bullshit you.”

Perhaps the accumulated weight of these validations helps Malone sustain philosophical equanimity in processing the inequities he discerns as he approaches his own elder statesman years. “I meant what I said about critics who have racist agendas and jump on things that are devoid of ethnic elements,” he says. “But my attitude now is that what anyone decides to play ain’t my damn business. I’m just trying to play good music, what feels right, and at the end of the day, I have to take responsibility for what I do. When I hung out with Ornette and Blood, I wasn’t concerned about trying to push the envelope. I was looking for a different musical experience. I’m not going to change who I am. I don’t classify my favorite musicians, like Hank Jones, as ‘modern.’ I steer away from that word. I see them as timeless. That’s how I want to be.”

SIDEBAR

“It’s all in the hands,” is all Russell Malone will say about his plush, full-bodied, instantly recognizable tone. “Everybody hears their sound in their head, no matter how old they are. I just heard a recording of me with a gospel group when I was 16. It sounds like me — the feel and everything else. You refine the nuances and subtleties over time, but it’s going to still sound like you.”

He points to a Gibson Super-400 standing by an armchair in his living room. “Kenny is the reason I play that guitar,” he says. “Just before I joined Jimmy Smith, he did a concert in Atlanta. He needed a Twin amplifier, and I had an old one, so I brought it for him to play his Super 400 through. I decided that if I ever made some money, I’d get one.

“I modeled my sound after him, Jim Hall and Mundell Lowe. They get this big, beautiful, round sound, where you can still hear the wood. Kenny picks great notes, plays great tunes. He also sings. Great composer. Master musician.”

Malone continues: “What attracted me to George Benson was the drive in his playing. He showed us that you can be a great musician and still be successful. That whole thing about being a starving artist never worked for him. It never worked for me either. I think we all sound better when our bills are paid and when our bellies are full. A lot of people have disparaged George for ‘selling out.’ That’s one of the dumbest things I’ve ever heard. The way I look at it, he cashed in on his talent.”

On a previous occasion, Malone had offered

a list of guitar heroes that also included Chet Atkins, George Van Eps,

Johnny Smith, Pat Martino and Wes Montgomery. “I love everyone on that

list, but Wes really sets my soul on fire,” he says. “I’ve loved every

record I’ve heard by Wes Montgomery. He never played a bad note. Always

got a good sound, good taste, and swung all the time.” —TP

Russell Malone Blindfold Test, Downbeat, 2004:

1. Ted Dunbar & Kevin Eubanks, “Fried Pies” (from Project G-7: A Tribute To Wes Montgomery, Vol. 1, Evidence, 1993) (Dunbar, Eubanks, guitars; Rufus Reid, bass; Akira Tana, drums; Wes Montgomery, composer)

This is a Wes Montgomery tune, Fried Pies. It’s two guitar players. This guitar player, whoever he is, is playing with his thumb, and he doesn’t seem to have good control. It would lay in the pocket better if he played it with a pick, I think. I have no idea who this is. I mean, this is just okay. It’s funny when you play a tune like this, that’s already been done right once. I almost never play songs by my heroes, because unless you can bring something to the table that’s equally as good or better than, what’s the point of playing it. Now the second guitarist is playing it. He sounds good. He seems to be more in the pocket than the other player. He’s got some fire, too. I like the bass player and the drummer; they’re locking up very nicely. Is that Kevin Eubanks? Ah!!! Ha-ha! Yeah! Now, that makes sense. This record was done about ten years ago, right? Was that other guitar player William Ash? I have no idea who the other player was, but I recognized Kevin immediately. There’s a certain way he attacks the notes. He’s not playing with the pick, he’s playing with his fingers, but he has a certain attack. That’s the reason why I was able to distinguish him. He plays very nicely. 4 stars for the bass player and drummer, because they really locked in well. Hell, 5 stars for Kevin. The other guitar player played nicely enough, but I would have liked it more if he’d been in the pocket. 3 stars for him. I’ll give the piece 3 stars. [AFTER] That was Ted Dunbar? Wow! I loved Ted. I never got to meet him. I talked to him on the phone a couple of times. I heard Ted play before, and he could definitely play better than this.

2. Jonathan Kreisberg, “Gone With the Wind” (from New For Now, Criss-Cross, 2004) (Kreisberg, guitar; Gary Versace, organ; Mark Ferber, drums)

This is nice. Is that John Abercrombie? I have no idea who it is, but he plays very nicely. He has a nice touch. The sound of the organ threw me in the beginning, because it sounded like one of those cute Farfisas or Wurlitzer, but now it sounds rich. Boy, this guitar player is killing! Oh, that’s Jonathan Kreisberg! So that must be Gary Versace on organ. I can’t remember the drummer’s name, but I think he plays with Jonathan every week. Jonathan’s a good friend of mine. Wonderful player. I’ve gone to see him a few times and listened to him, and once you become familiar with a person, you become accustomed to what they sound like. Everybody has a sound. Jonathan is younger than I am; I think he’s in his early thirties. I hear a lot of people talk about young guys don’t have a sound, which I think is total bullshit. Everybody has a sound, everybody has a voice; it just depends on how familiar you are with that person. If you listen to a person enough, then you will be able to distinguish it. That’s how I was able to distinguish Kevin on the previous thing you played me, and this is how I was able to distinguish Jonathan. There are certain things you key in on. Here it’s Jonathan’s sound and the ideas that he plays, and his touch. I love this tune, Gone With the Wind. I like that they took an old standard, and did something different with it. It sounds like they’re playing it in 6/4. Jonathan has chops in abundance, and one thing I like about his solo is that he really took his time and said something beautiful on the tune. Guys with that kind of ability to play whatever they want on the instrument sometimes have a tendency to overstate. But he didn’t do that, and I appreciate that approach. 4 stars for Jonathan.

3. Joel Harrison, “Folsom Prison Blues” (from Free Country. ACT. 2003) (Harrison, guitar; David Binney, alto sax; Rob Thomas, violin; Sean Conly, bass; Allison Miller, drums)

Man, this sounds like some of the sanctified music that I grew up hearing in my church. Oh, this is grooving. Is it Derek Trucks? Wow! I LIKE this cat, whoever he is. See, this is one of the things that guitar can do. It can bend notes, it can wail, it can cry. Whoo, man! Now, this was fine until the horn player started to play. He’s probably a bad cat, but he’s not really adding anything to this performance. Is it Bill Frisell? Oh, this is Folsom Prison Blues? The Johnny Cash tune. I didn’t recognize it without the lyrics. The guitar player, whoever he is, he just got right to the heart of the matter. But the horn player, though he’s probably a great musician, listening to him play is kind of like eating crabs. You’ve got to go through so much to get so little. He’s not really doing it for me. But the guitar player got right to the heart of the matter. Mark Ribot! It’s not Mark Ribot? Dammit. I give up. Joel Harrison? I’ve never heard of him. I’m going to go out and get some Joel Harrison records, man. That’s one of the ways I like to hear guitar played. Because the guitar is such an expressive instrument. It can do so many things, man. That’s going into the CD collection. Joel Harrison. 5 stars. I loved him. I’ve seen Dave Binney’s name, but I don’t know him. I like the bass player and the drummer. I like the whole band. Oh, I know Allison Miller. She’s great!

4. Rodney Jones, “Summertime” (from Soul Manifesto Live!, Savant, 2003) (Jones, guitar; Will Boulware, Hammond B3; Lonnie Plaxico, bass; Kenwood Dennard, drums)

Whoever this is, I hear a very strong George Benson influence. The tune is Summertime. Rodney Jones. Which record is this from? Soul Manifesto Live? Okay. This is just okay. I’d like to have heard him pay closer attention to the melody. This is a personal thing with me. What he’s playing is great. That tune has such a beautiful melody. I’d like to hear a little less embellishment of the melody. It’s a little bit too much guitar for me. Now, Rodney’s bad. I’ve heard him play a lot more musically than this. It doesn’t do it for me. I love Rodney; he’s one of my best friends and one of my favorite guitarists, but I don’t feel this. I’ve heard him play a lot better. 2½ stars.

5. Jim Hall-Geoff Keezer, “End The Beguine” (from Free Association, Artists Share, 2005) (Hall, guitar, composer; Keezer, piano)

Mike Stern? No? Okay. Oh, I like the dissonance. The guitarist sounds like he’s picking close to the bridge. It sounds like he’s playing one of those solid body guitars. That’s cool. That doesn’t offend me at all. Mick Goodrick. It’s not Mick Goodrick? Ah, that’s Jim Hall. [LAUGHS] Yeah, go ahead, Jim! That’s Geoff Keezer. I heard them play this tune at the Vanguard when they played there a couple of years ago. These are two of my favorite musicians. Geoff Keezer is one of the greatest piano players walking the planet today. He can do anything; he’s so versatile. What can you say about Jim? He’s a magician. He’s like a magician that makes the rabbit pull him out of the hat! Wouldn’t that be something to go see a magician, and then the rabbit pulls him out of the hat. That’s the way I see Jim. He’s such a quirky, unorthodox kind of guy, but he’s always musical. Never anything for the sake of being different. Everything that he plays and does has a purpose. One of my favorite things about him is that there’s so much beauty in his playing. Most guitar players go for the jugular vein, and that’s okay to do, too. But Jim Hall showed us that it’s okay to go for the G-spot, too. 5 stars. Give Jim Hall the Milky Way. In the beginning I said Mike Stern and Mick Goodrick, but even though I was wrong I wasn’t too far off-base, because I know Jim Hall has influenced both of those players. What threw me in the beginning was that Jim was picking towards the bridge, and when you do that, it makes the tone of the guitar thinner, more brittle, and that’s not how I’m used to hearing Jim. But what gave it away was just the touch and the ideas.

6. Nguyen Lê, “Walking On The Tiger’s Tail” (from Walking On The Tiger’s Tail, Nonesuch, 2005) (Lê , guitars; Paul McCandless, oboe; Art Lande, piano; Jamey Haddad, percussion)

I like this. Really thick harmony. Thick chords. Is that a bass clarinet? Is it Adam Holdsworth? Nels Cline? Oh, wait a minute. Dave Fiuczynski. No? Okay. Damn. Whoever he is, he’s a heck of a player. I like it. Whoo! Ben Monder. Not Ben? It sounds spacious. It’s out there, but there’s a groove. I mean, you can pat your foot. It sounds good and it feels good. Is he European? [Yes.] This is good. I think I would appreciate this better if I was listening to these guys play live. After a while, it all starts to sound the same. There was some stuff that moved in certain spots, but now it’s going on and on and on. It doesn’t really do anything for me. But I liked what led up to this. I have no idea who the guitarist is. 3 stars. There’s no denying the ability. Everybody can play. That cannot be denied. Nguyen Le? I’ve heard him. He’s good! I’ve been meaning to check out more of him. I have nothing but respect for him, but as far as this performance, I’d appreciate it more if I was sitting there listening to them. I have some homework to do. There’s so much stuff out there. I’ve seen this guy’s name, and I have heard him play and I liked what I heard. What I heard by him was acoustic, and it was beautiful.

7. Bill Frisell, “My Man’s Gone Now” (from East-West, Nonesuch, 2005) (Frisell, guitar; Tony Scherr, bass; Kenny Wolleson, drums)

I like this. He’s getting some very beautiful colors out of the instrument. Nice voicings. Is that Ben Monder? No. I like Ben. “My Man’s Gone Now,” a Gershwin tune. This is really pretty. Is that Paul Motian on drums? Is this Frisell? Aha. He does a lot of different things. He does a lot of things with swells and he uses effects. You never know what kind of bag he’s going to come out of. Oh, yeah! He’s a very wonderful musician, and he’s a very nice guy, too. I have to be honest with you. For a while, I had a problem with listening to guys like Bill Frisell and Metheny and Scofield, a lot of the white players. Not because they were bad musicians. It’s just that whenever white writers would write about these guys, I always got the feeling that they were making them out to be superior to a lot of the black players. So for a long time, I didn’t listen to these kinds of players, but after having met them, I found out that they don’t think like that at all. These are very nice men and they’re great musicians. 3 stars. This was very good. I like listening to things like this, but after a while I like to hear some time. I like to hear guys deal with time. But Frisell is great. He’s a wonderful musician. But for a while I didn’t want to hear guys like that, because of the way certain writers would write about them. But having met them, I know that they don’t think like that at all. These are very soulful guys. They’re just about the music.

8. Calvin Newborn, “Newborn Blues” (from New Born, Yellow Dog, 2005) (Newborn, guitar; Charlie Wood, organ; Renardo Ward, drums)

I like this. This is home here. This is where I live. Whoever this guy is, he likes B.B. King. That’s not B.B., is it? But he likes B.B., whoever he is. I know some critics might look upon this kind of thing as being dated and predictable and not pushing the music forward and whatever, but I NEVER get tired of this, man. The blues, man. To me, jazz needs that. I have no idea who this guy is, but give him the Milky Way, too, whoever the hell he is. I love this. I love the band. I love the way they’re locking in together. This is great. He’s not playing anything slick or fancy, but it makes sense, it works, and it sounds great. Oh, yes, yes, YES! Oh, yeah. Cornell Dupree? Calvin Newborn! Know how I knew? The touch! That’s what I’m talking about. All the stars in the universe. I’m very suspicious… You’ve played some great stuff today. But I read about a lot of players who the critics write about as players who are pushing the envelope or players who are breaking away from the tradition. I’m very suspicious about players who are described that way, because to me, all it means is that they deleted all of the ethnic elements out of the music—or the black elements out of the music. Players who adopt a Eurocentric perspective seem to be the ones who are described as pushing the music forward. I mean, I know the music has to move forward and everything, but come on, man. If you don’t have this, you got nothing. You might have something else, but you need those ethnic elements to have jazz, man. Some people may disagree with me, but that’s just the way I feel. Right on, Calvin Newborn. Bend those notes. Play that blues. [LAUGHS] Yeah! That’s how I feel about that one. Listening to him… I got the same feeling as I got when Joel Harrison played. I don’t care what color he is. I’m sure he’s white. But he is not afraid to acknowledge the blues, those black elements. He’s a brave white man who is not afraid to acknowledge that in his playing. My hat’s off to him.

9. Baden Powell, “Samba Triste” (from Live A Bruxelles, Sunnyside, 1999/2005 (Powell, guitar, composer)This is just okay. Whenever I hear people play solo guitar, especially on the nylon string, I like to hear a lot less sloppiness. I don’t mean to sound like I’m nitpicking. I know it sounds like I am. But I have to tell you how I feel. This is a little sloppy for my taste. This doesn’t really go anywhere. If there is a melody, it’s damn near nonexistent. The tune is weak and I think it’s poorly played. I have no idea who this is. Whoever he is, it’s probably a legend. But this is a pretty poor performance. Is it Barney Kessel? Well, I don’t know if he did anything on the nylon string anyway. Bad guess. Bill Harris? He’s a guitarist who lived in D.C. who did some things on the nylon string guitar. No, this is not good. 1star. That’s Baden Powell? That’s surprising, because I’ve heard him play. I feel really bad that I don’t like this, because I love Baden Powell. He’s a monster player. I love the way he plays. But this is not a good performance. I’ve heard him play on other things, and the touch is a little more delicate than this.

10. Paul Bollenback, “Too High”(from Soul Grooves, Challenge, 1999) (Bollenback, guitar, arranger; Joey DeFrancesco, organ; Jeff Watts, drums; Broto Roy, tabla; Stevie Wonder, composer)

This is a catchy tune. The band is swinging. Is this Too High? Yeah. That’s a Stevie Wonder tune. This is nice. They put a lot of thought into this. I have no idea who the guitar player is. Now, the guitar player has got some chops. Once again, a very strong Benson influence. George is all over the place. Is it Paul Bollenback? Okay. [LAUGHS] I know his ideas and his touch. Very nice arrangement. He put some thought into this. It’s very well played. Is that Joey on organ? Byron Landham on drums? Billy Hart? Whoever he is, he’s really locking in, man. He’s swinging, laying that pocket down. That’s Tain? Whoa! That doesn’t surprise me. He played on my all-ballad record, Heartstrings, and Tain, man… He’s got the whole history of the drums. There are a lot of young drummers coming up nowadays who are influenced by him, but I don’t think they’ve really checked out what makes Jeff Watts, Jeff Watts. He’s got Kenny Clarke, he’s got Baby Dodds, he’s got Elvin, he’s got Tony—he’s got everything. And he’s incorporated all of these influences and came up with his own thing. Yeah! 4 stars. With Tain, swinging is not an afterthought. Whatever wild and crazy things he does, it’s all rooted in swing. It’s all about that groove. It’s never an afterthought for him.

11. Kurt Rosenwinkel, “Brooklyn Sometimes”(from Deep Song, Verve, 2005) (Rosenwinkel, guitar, composer; Brad Mehldau, piano; Larry Grenadier, bass; Ali Jackson, drums)

Kurt Rosenwinkel. That’s Kurt! He’ s a great musician. I have a lot of respect for him. He’s always very musical. I have quite a few of his records around here. He’s a wonderful musician. Plays the piano. Knows the instrument and the history of the music. I have a lot of respect for him. He’s a phenomenal player. That’s his latest release on Verve, Deep Song. I have it. That’s the beauty of being in New York. You have so many different types of musicians here. So many different types of music to take advantage of. I always tell young players when they come here, don’t just get locked into one thing. You may have your taste and your preferences, but go out and hear all kinds of different things. Go out and hear these different kinds of players, because you may find something you’re able to use. That’s why I love being in the city, because I get to hear all kinds of players on any given night. 4 stars.

https://downbeat.com/news/detail/qa-with-russell-malone

Q&A with Russell Malone: Truth in Who You Are

by John Murph

July 31, 2017

Downbeat

|

Guitarist Russell Malone’s new album is TIme For The Dancers (HighNote). (Photo: Courtesy of the artist)

It’s nearly impossible not to move while listening to Russell Malone’s enticing new album, Time For The Dancers (HighNote). The 53-year-old guitarist and composer packs plenty of boogie into his retooling of the Sir Roland Hanna-penned title track, provoking you to bob your head; the gutbucket “Leave It To Lonnie” invites you to get on the good foot; and the sensual reading of Peggy Lee’s “There’ll Be Another Spring” seduces you to sway slowly.

Complemented by the same ensemble featured on his 2016 disc, All About Melody (HighNote)—drummer Willie Jones III, pianist Rick Germanson, and bassist Luke Sellick—Malone delivers a bona fide “feel-good” album that will resonate with a wide audience.

DownBeat caught up with Malone to discuss the chemistry he’s forged with his current bandmates, which, with the substitution of Sellick for bassist Gerald Cannon, has recorded and toured with him for the past several years. Malone also discussed the inspirations behind some of the disc’s tunes.

Let’s talk about the chemistry you’ve forged with this band. Even with Sellick being relatively new to the ensemble, the rapport is quite strong. And a lot of these songs were road-tested before you recorded them.

A lot of it has to do with trust. When you have trust, you don’t have to try to make something happen. Everything will take care of itself. That applies to relationships in general—not just in music.

The title of the album is Time For The Dancers. Talk a bit how the concept of dance—regardless of what kind—helps you shape your melodies and improvisations.

Remember the first time you heard music—probably as a little child? The first time I heard music was in church. I wasn’t concerned about the technical aspects of the music. The first time I heard music, it made me want to dance. That’s what music is supposed to do.

There’s definitely that element of wanting to listen, to take things apart and analyze them. That’s all good, too. But I think if someone wants to dance to the music, it’s natural.

I had conversations with some of the older jazz players, like Lou Donaldson and Benny Golson—and they talked about how years ago people would dance to the music. When the beboppers got a hold of it, the music became more of this intellectual thing, where you just sat down and listened to it. And that’s all well and good, too. But I like people to dance to my music and have a good time.

I know some musicians who don’t like that; they [get] distracted by people clapping and dancing during the performance. I’ve been onstage with some musicians who really get uptight when the audience gets very vocal and physical with enthusiasm. Usually, it was someone who was younger and took themselves a little too seriously. They take offense to people responding that way.

But people dancing and responding vocally never bothered me. I think it has something to do with my musical upbringing. I played all kinds of gigs—country, funk, jazz and gospel.

Could you reflect on your experience with bassist Lonnie Plaxico? When I first heard the tune “Leave It To Lonnie,” I thought it was a reference to Dr. Lonnie Smith because of the groove.

Lonnie [Plaxico] and I met when I first came to New York back in 1985. We worked at Barry Harris’ Jazz Cultural Theater. They had jam sessions at this place. Lonnie’s only a couple of years older than me. But he was already on the scene, playing with Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey and Dexter Gordon. Lonnie and I ended up playing together onstage at the jam session. After we finished playing, Lonnie walks up to me and says, “Hey man, you sound good,” then asked me where I was from. I told him Atlanta. Then he said, “You sounded great. You got a good feeling and you hear changes really well. But while you may get away with playing that way down in Georgia, you can’t get away with that kind of playing up here in New York.”

His comment caught me off guard. He said, “I can hear a lot of your influences. But at some point, you’re going to have to play who you are, because New York has already seen the Grant Greens, the Wes Montgomerys, the Kenny Burrells and the George Bensons. And the reason why they were able to thrive when they came here was because they had something of their own to offer.”

Nobody had ever told it to me like that. I got to thinking about some of my experiences on the local scene in Georgia. Not only did people there expect you to sound a certain way; they expected you to sound like other people down there.

Lonnie gave me some of the best advice ever. We have remained friends ever since.

Many different kinds of artists receive the type of advice that Lonnie gave you. But hearing that advice is far easier than actually applying it. Talk about the point in which first you recognized in your music that you were playing who you are.

Everybody has a voice. You can take the most derivative-sounding musician and if you listen to them [long] enough, you’re going to hear some things that are unique. What that type of musician doesn’t always have—particularly when they’re young —is the confidence to speak in their personal voice.

Early on in everyone’s development, you want to be accepted and liked. When I was a younger musician, there were certain things that I felt I had to play or needed to play just so people would accept me. I understood what Lonnie told me, but sometimes it takes time for certain things to really sink in.

I got to a certain age where I said to myself, “As much as I love all of the people who’ve influenced me, when it comes to being Russell Malone, there’s nobody better. There’s nobody better than me at me being me.” That was a revelation for me. I learned to embrace my so-called imperfections, my quirks, even my ethnicity.

I don’t care if West Montgomery came back down to Earth with wings on his back, playing a golden guitar with golden strings; I still have to play me.

Another revelation that came to me when I got older is that I didn’t have to like everything about my mentors; I don’t have to make the same musical choices. It’s like realizing that your parents aren’t perfect. As much you love, respect and appreciate them, you realize that they are not infallible.

On Time For The Dancers, you revisit some of your older songs, such as “A Ballad For Hank Crawford.” In the liner notes, you mention that it took you almost a decade to complete that tune. Why so long?

I had never recorded that tune before. I actually began working on it when I first started making records. I’d thought about putting it on my Black Butterfly record [in 1993], but the tune wasn’t quite ready yet. And at that time, I wasn’t even thinking about Hank Crawford; I just had this soulful, bluesy idea in my head.

Then I got to hanging out with Hank Crawford. We worked together on this B.B. King record, Let The Good Times Roll [1999]; it was a tribute to Louis Jordan. I heard Hank’s music on the radio a lot; I just loved the way he played.

After that session, I started messing around with that tune again. I came up with some different things that I wanted to incorporate, then I left it alone. A couple of years later, I went back and finished it. I think it really captures Hank.

You also revisit “Flowers For Emmett Till.” That song was on your 1992 debut as well as 2004’s Bluebird with pianist Benny Green. Why did you feel the need to revisit it at this particular time?

A lot of people liked that song. The thing that inspired it was me being in junior high school and having one of my teachers who was always trying to keep us socially conscious and culturally aware about our history. One day, she came to school with a Jet magazine that had an article about the death of Emmett Till [1941–’55]. She told the story about how he was accused of getting fresh with a white woman. She showed us the picture of his mutilated body in the coffin, and then said, “This is what hate and ignorance look like.”

I had nightmares about that picture for a long time. I never told my parents about those nightmares. So I started hearing this melody in my head when I was still that little kid even though I had a lot to learn musically. But I could play that little melody on the guitar—just those single notes. As I started advancing as a [musician], I decided to play it on my first record on nylon-string guitar in a pseudo-classical way. Then on the record with Benny Green, I played it solo again but on electric guitar.

When I was putting the music together for this latest recording, I wanted to play it because I was never completely satisfied with the previous versions. So I decided to try it with an ensemble. And it turned out pretty well.

Plus, the lady [Carolyn Bryant] who accused Emmett of making a pass [in a Mississippi grocery store in 1955] came out this year to confess that she lied. When I heard that, I said, “Well, I’ll be damned! A [teenager’s] life was taken violently because of ignorance, hate and lies.”

So much stuff has happened, and we still have a long way to go. … I have fans from all over the place, of all different nationalities and colors. So things like this need to be talked about. DB

Jazz fest: Russell Malone brings his influence to bear

It was 20 years ago that guitarist Russell Malone joined Diana Krall’s band, starting a four-year run that included three Grammy-nominated albums and that showcased his talents to audiences worldwide.

ut Malone is quick to point out he was already a well-seasoned musician

by then, after stints with organist Jimmy Smith, singer Freddie Cole and

Harry Connick Jr.’s big band for four years.

“I loved playing with Diana,” he recalled in an interview from his New Jersey home. “But I wouldn’t have been able to play that way if it hadn’t been for everything that came before.”

By then, the Georgia-born guitarist had assimilated a wide range of influences from country legend Chet Atkins to blues masters like B.B. King and Buddy Guy. In the jazz space, George Benson was a beacon.

“What

attracted me to George was just the control he had on the instrument,”

Malone recalled. “He played so effortlessly and fluidly. There was a

sound he got out of that guitar. I saw George when I was 12 and that let

me know there was a whole level of excellence to aspire to.”

Malone brings all those influences to Upstairs Thursday and Friday with a quartet comprising Rick Germanson on piano, Luke Sellick on bass and Willie Jones III on drums. He has a warm and relaxed sound but stresses that straight-ahead jazz is only part of what he loves to play.

“I always try to be open and flexible, I don’t turn up my nose at country music or funk like some jazz players do. Everybody’s got something to say.” He mentions several Brazilian guitarists as inspirations and adds that “Eddie Van Halen is great.”

Malone crafted his personal style as a self-taught musician who learned by ear and later refined that knowledge with help from a few masters.

“I didn’t go to music school but I think people make too much out of being self-taught,” he says. “I don’t care how much you learn on your own, at some point you have to admit your shortcomings if you’re going to get better.

“You have to find people who are better than you that can help you. I was fortunate because I was around great musicians who would tell me what I needed to work on, like sight-reading. I’m still working on that and trying to get better.”

He learned other things, too, like how to play with people, how to accompany, knowing what not to play and how to stay out of the way – all things you can’t really pick up on your own.

“I didn’t take any playing experience for granted. I got something valuable from each experience,” he says. Playing with Jimmy Smith, for example, “I got my hide handed to me every night,” he adds with a laugh.

He also likes to rise to the occasion, such as the time he subbed for

the great Jim Hall in a tour with fellow guitarist Bill Frisell. It

would be hard to find a more unusual pairing given their different

musical styles but “we had no problem sitting in,” he says. “We

acknowledged we were different players but once we got past that, then

we started to focus on what we had in common.”

Russell Malone

Upon entering Malone’s home on the first floor, I doff my shoes on request and see a number of Malone’s guitars and amps, two Diana Krall gold records, a foldaway treadmill and so on. The eat-in kitchen is straight ahead and to the back. Upstairs on the second floor is a stylish living room as well as a sizable office and a half-bath. On the third floor are two bedrooms and a full bath. Malone is fairly meticulous about keeping the place clean. “I might kick my shoes off and leave them on the floor for a day or so,” he allows. “But two things I cannot tolerate are a funky bathroom and a funky kitchen.”

Malone is more of a guitar freak than a neat freak, however. As soon as he confirmed that I, too, was a guitarist, he was only too eager to let me handle every instrument in the house. Later he put on recordings by George Van Eps, George Barnes, George Benson and even free improviser Joe Morris. “It’s hard for me to find a guitar player I don’t like,” he says. “I love hearing the guitar played well, and it doesn’t matter what style it is.”

But perhaps even more than listening, Malone loves to play. Before I left the house I ran the gauntlet and jammed with him, for close to an hour. The musicality and sheer brawn of Malone’s fretwork can be overpowering. His time feel is as solid as the very best drummers’. If he had one hand and I had four, Malone would bury me. But the mood in the room was exuberant, the vibes entirely positive. There was a utilitarian aspect to our session as well: Malone had been sick and needed to get his chops back. “I’m playing tomorrow with that maniac, Benny Green,” his partner in the new duets disc Bluebird (Telarc).

The past several years have seen a slimmer Russell Malone. “I was in the hotel one night and I looked in the mirror and my gut was so big it looked like someone was walkin’ in front of me.” After getting advice and inspiration from saxophonist and friend Vincent Herring, Malone went on a modified version of the Atkins diet. “Now I’m down to the size I was when I was 20. But if I want to indulge in some sweet potato pie or some vanilla ice cream, certain things I’m not going to deny myself.”

Malone has amassed a formidable discography for a 40-year-old. Recent standouts include two drumless trio recordings, The Golden Striker with Ron Carter and Mulgrew Miller (Blue Note) and Ray Brown, Monty Alexander and Russell Malone (Telarc). After stints on Columbia and Verve, Malone debuted on MaxJazz in March of this year with Playground, featuring pianist Martin Bejerano, bassist Tassili Bond and drummer E.J. Strickland, with special guests Gary Bartz and Joe Locke. “I’m so fortunate that I’m playing music that I like,” Malone says. “I’m playing with some great musicians, and I’m improving all the time. I can look back as recently as a year ago and see where I’ve gotten better.”

Car?

A 2000 Toyota Camry, burgundy. “The one before that was a Toyota too. I take the train every now and then but I like driving because it’s very comfortable. I’m more relaxed when I drive because that’s where I do most of my listening.”

Reading?

Mr. S: My Life with Frank Sinatra, by George Jacobs. “He was Sinatra’s valet for 12 years. Sinatra’s a very fascinating character, and it’s interesting to read about him from the perspective of an African-American. There’s lots of juicy stuff in there.” Malone also pulls out Martin Meredith’s biography of Nelson Mandela and a couple of volumes by Ralph Wiley. But he pauses over a book called Bullwhip Days, edited by James Mellon. “I’m going to give this one to my kids when I die. It’s a collection of interviews with actual slaves, people who survived slavery, and they tell what it’s like.”

Computer?

“PC, a Compaq. I pay all my bills on the computer and check my e-mail, and every now and then I like to surf.”

Fitness?

“I got weights over there, a treadmill downstairs. This thing here, it’s some sort of abs machine. I use it to prop up my guitars.”

Movies?

“I love movies. I saw The Passion of the Christ and Starsky and Hutch because I was such a big fan of that show. I liked the movie with Diane Keaton and Jack Nicholson, Something’s Gotta Give. It was great to see a movie where older people fall in love. I go out to movies; I almost never rent a movie. I’m old fashioned. I like the experience of going out, taking someone and sitting back in a theater.”

Food?

“I eat everything that Noah had on the ark,” Malone chuckles, although he admits to a phobia of raisins. “I had a bad experience. I must have been about four. A guy came to visit my dad, and he was eating raisins. So I put my hand out, and he gave me a handful. I put them in my mouth and threw up on the spot.”

Russell Malone Biography

Born 1963 in Albany, GA. Addresses: Record company--Verve Music Group, 555 W. 57th St., New York, NY 10019 Phone: (212) 424-1000 Fax: (212) 424-1007.

Jazz guitarist Russell Malone provided an interesting analogy to describe his approach to music. As he told Billboard magazine's Steve Graybow, "One of the things that made Franklin Roosevelt such a good president was that while he was educated--an aristocrat--he still knew how to talk to the common man. That principle should apply to music. Every song doesn't have to be a lesson in theory and harmony. A lot of guys feel a need to educate the audience; I'd rather reach people."

Born in Albany, Georgia, in 1963, Malone grew up within a deeply spiritual church environment that influenced his early interest in music. He received his first instrument, "a green plastic four-string" according to Malone, at the age of four. However, after watching legendary blues guitarist B.B. King play "How Blue Can You Get" during an episode of the popular 1970s sitcom Sanford and Son, Malone started gravitating to various other musical forms besides gospel. And as the young guitarist discovered the blues, country, and jazz, he began to marvel at the musicianship of both country singers/guitarists such as Chet Atkins and Johnny Cash, as well as jazz guitarists like Wes Montgomery and George Benson.

Listening to the songs of the aforementioned performers and others, Malone taught himself how to play guitar. By the time he reached 25 years of age, he accepted his first gig playing with master organist Jimmy Smith. During his first performance with Smith, Malone recalled, "It made me realize that I wasn't as good as I thought I was," according to the Verve Music Group. Two years later, Malone joined singer/pianist Harry Connick, Jr.'s orchestra, holding this position from 1991 through 1994. In the meantime, Malone also worked with a diverse variety of other musicians, including Clarence Carter, Little Anthony, Peabo Bryson, Mulgrew Miller, The Winans, Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, Bucky Pizzarelli, and Jack McDuff.