SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

WINTER, 2018

VOLUME FIVE NUMBER TWO

GERI ALLEN

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

TOMEKA REID

(January 27--February 2)

FARUQ Z. BEY

(February 3--9)

HANK JONES

(February 10--16)

STANLEY COWELL

(February 17–23)

(February 17–23)

GEORGE RUSSELL

(February 24—March 2)

ALICE COLTRANE

(March 3–9)

DON CHERRY

(March 10–16)

MAL WALDRON

(March 17–23)

JON HENDRICKS

(March 24–30)

MATTHEW SHIPP

(April 1–7)

PHAROAH SANDERS

(April 8–14)

WALT DICKERSON

(April 15–21)https://www.allmusic.com/artist/stanley-cowell-mn0000011303/biography

Stanley Cowell (b. May 5, 1941)

Artist Biography by Matt Collar

A superb modern jazz pianist, Stanley Cowell

is a highly regarded artist whose work often pushes the boundaries of

forward-thinking hard bop without ever falling into completely

avant-garde territory. Born in Toledo, Ohio in 1941, Cowell began studying piano around age four and first became interested in jazz after gaining exposure to the music of pianist Art Tatum,

a family friend. After high school, he attended both the Oberlin

College Conservatory and the University of Michigan, during which time

he also gained valuable experience playing with Rahsaan Roland Kirk. In the mid-'60s he moved to New York City, where he played regularly with such luminaries as Marion Brown (1966-1967), Max Roach (1967-1970), and the Bobby Hutcherson-Harold Land Quintet (1968-1971).

As a leader, Cowell debuted on the Arista-Freedom label with 1969's Blues for the Viet Cong, followed that same year by Brilliant Circles. He then moved to ECM for 1973's Illusion Suite. Also in the early '70s, he worked regularly with trumpeter Charles Tolliver,

with whom he co-founded the Strata East label. Consequently, he

delivered several highly regarded albums for the label, including 1974's

solo piano date Musa: Ancestral Streams and 1975's Regeneration. Also during this period, he played regularly with the Heath Brothers and continued recording, releasing a handful of solo piano albums for Galaxy Records, including 1977's Waiting for the Moment and 1978's Equipoise.

Beginning in 1981, Cowell

started balancing his time between performing and working as an

educator, first at CUNY's Lehman College, and then spending several

decades at Rutgers University in New Jersey. During these years,

however, he remained active in the studio and developed a fruitful

relationship with SteepleChase Records, which issued such well-received

albums as 1989's Sienna, 1993's Angel Eyes, and 1997's Hear Me One.

More albums followed for the label, including 2010's Prayer for Peace, which featured the pianist's daughter Sunny Cowell on vocals. Two years later, he was joined by former Rutgers students bassist Tom Dicarlo and drummer Chris Brown on It's Time, followed by 2013's Welcome to This New World with the Empathlectrik Quartet and 2014's Are You Real? In 2017 he delivered his 15th album for SteepleChase, No Illusions, featuring saxophonist/flutist Bruce Williams, bassist Jay Anderson, and drummer Billy Drummond.

Stanley Cowell

Stanley Cowell can best be described as an intellectual pianist. From his early classical roots to collaborations with premier jazz artists to his creative solo career, Cowell’s music has been defined by integrity and taste. With an agile left hand and a relentlessly imaginative approach to standards and his own compositions, his solo concerts are events to be savored.

Stanley Cowell, was born in Toledo, Ohio, in 1941. He studied piano there with Mary Belle Shealy and Elmer Gertz, and pipe organ with J. Harold Harder. By the age of fifteen, he was a featured soloist with the Toledo Youth Orchestra in Kabelevsky's Piano Concerto No. 3, a church organist/choir director, and a budding jazz pianist.

Cowell's formal training in music has been quite extensive: a Bachelor of Music degree from Oberlin Conservatory and a Master of Music degree from the University of Michigan. He also has additional undergraduate study at the Mozarteum Akademie, Salzburg, Austria, and graduate study at Wichita State University and the University of Southern California. While at U.S.C., 1963-64, he performed Gershwin's Concerto in F with the Burbank Symphony Orchestra, and played jazz in the Los Angeles area with Curtis Amy's and Ray Crawford's bands.

After completing his Masters at Michigan in 1966, Cowell headed for New York City where he worked for such musical artists as Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Herbie Mann, Miles Davis, Stan Getz and the Bobby Hutcherson-Harold Land groups. For several years he was part of Charles Tolliver's Music Inc., with whom he formed the innovative musician-owned record company, Strata-East, in 1971.

Cowell organized the Piano Choir in 1972, a group of seven esteemed New York-based keyboardists, and he became a founding member of the Collective Black Artists, Inc., a non-profit company devoted to bringing African-American music and musicians to the public. He served as conductor of the CBA Ensemble, 1973-1974.

In 1974, he served as a musical director of George Wein's New York Jazz Repertory Company at Carnegie Hall, along with Gil Evans, Dr. Billy Taylor and Sy Oliver. During the Seventies, Cowell established his reputation as a versatile and sensitive pianist/composer, performing and recording with Sonny Rollins, Clifford Jordan, Oliver Nelson, Donald Byrd, Roy Haynes, Richard Davis, Art Pepper, Jimmy Heath and many more great musical artists. From the period 1974-1984 he toured, recorded and conducted workshops throughout the Americas, Europe and Japan as the featured pianist with the Heath Brothers (Percy, Jimmy and Albert). He was a recipient of a Meet The Composer/Rockefeller Foundation/AT&T Jazz Program grant for 1990-1991, for the creation of “Piano Concerto No. 1” (in honor of Art Tatum), which was premiered by the Toledo Symphony Orchestra, January 17, 18, 1992.

Cowell served on the board of the Charlin Jazz Society, producer of jazz concerts in Washington, D.C., 1990-1996. He and his wife Sylvia currently produce concerts in Prince George's County, Maryland, under The Piano Choir, Inc., a non-profit music and educational entity.

In July, 1992, he was the featured piano soloist with the Colorado Festival Orchestra in Gershwin's Rhapsody In Blue, and many other “third stream” works, conducted by Gunther Schuller and Larry Newland. Stanley Cowell is currently a tenured professor at Rutgers University, Mason Gross School of the Arts, Department of Music, New Brunswick, New Jersey. From 1981-1999, he was a professor at Herbert Lehman College, C.U.N.Y., Bronx, New York, teaching music history, jazz history, piano, improvisation, electronic/computer music, arranging, and jazz band. From 1988-1989, he concurrently taught jazz piano at New England Conservatory, Boston.

Stanley Cowell, the pianist and composer, performs and lectures professionally as a solo pianist, and in ensemble formations from duo to orchestra. He performs in a variety of venues, from jazz club to concert hall, often utilizing electronic sounds and African finger piano.

http://blog.superflyrecords.com/storyboard/stanley-cowell-a-travelin-man/

Storyboard

STANLEY COWELL:

A TRAVELING MAN

A TRAVELING MAN

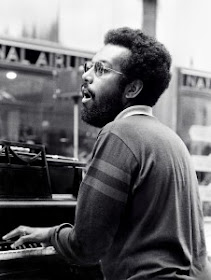

Stanley Cowell. photo : Maxim François / Vision Fugitive

Co-founder of Strata East Records, Stanley Cowell started his career in Detroit, in the sixties, before moving to New York. There, the pianist played with great jazzmen, both from the young generation and the older one like Max Roach with whom he recorded an LP. After the great seventies decade, he decided to teach but never stopped playing and recording. For us, he goes back to his story while he will publish a brand new album in may, focusing on the Civil Rights movement.

Did you grow up in a musical environment?

Yes. Though my mother often sang around the house, my father played a little violin and piano, and all my sisters took piano lessons for about six years, there were no professional musicians in my immediate family beside me. A niece, Michelle, became a professional lounge singer and entertainer with a local Toledo group called the Murphy’s, who toured the Holiday Inn circuit in the US for several years.

How did the piano come into your life? And the jazz?

My parents seemed to like and listen to as many types as were available in my formative years at home: popular songs, 18th and 19th century European classical, blues, gospel, hymns and other church related music. We always had a good radio, record players, and we had a television set by 1949. They seemed less interested in the favorite music of my teenage years, rhythm and blues, and later, modern jazz.

Which music did you listen to in the 1960s?

I heard the classical piano music my two older sisters and I practiced, our dance music, blues, rhythm ‘n blues and jazz on the juke box at my Dad’s restaurant, the hymns and church musics from various churches in the neighborhood; the good jazz, R & B and blues records that found there way from the restaurant to the house; blues singers like Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, Little Walter, Big Bill Broonzy; the growing number R & B groups like Clyde McFatter & the Midnighters, Orioles, Diablos, at night on the radio station WLAC from Nashville, Tennessee. These were the musics of my youth until I discovered bebop and modern jazz at age 13.

Who were your reference pianists?

Art Tatum came to my house once when I was six years old (1947). He was visiting family and friends and encountered my father, who invited him to our house. My father asked Art to play piano for me. Art said that he would like for me to play first. I played a piece from Book 3 of a popular piano study series, John Thompson. Art then played a Rodgers & Hart song, “You Took Advantage of Me.” That was my once and only “live” hearing of Art Tatum. I never wanted to sound like Tatum, but I have had to develop the technical ability to imitate him in certain “homage” performances since the 1980s. But in the 60s, my influences were McCoy Tyner, Cecil Taylor, Bill Evans, Wynton Kelly, and Phineas Newborn. I liked Andrew Hill, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett and Herbie Hancock, and considered them my peers.

Trio, 1959

Your professional debuts: how was the musical « scene » in Michigan?

I chose to defer New York a while longer for the opportunity to finish my master’s at nearby University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, majoring in piano performance. I attended Michigan starting January of 1965, and again I was immersed in studying piano, practicing and studying classical music by day, but playing jazz by night. The venue for jazz soon became six nights-a-week at The Town Bar, Ann Arbor. I was featured pianist with bassist Ron Brooks’ Trio. Ron Brooks’ previous pianist had been Bob James, who at that time was incorporating a great deal of freedom and experimentation into the trio. That base was the perfect situation to which I contributed, building the trio into a tight nucleus that attracted musicians and audiences from Detroit, Flint, and Lansing, Michigan, as well as Northern Ohio. As the political and social upheaval of the Sixties was being felt and expressed in the music most intensely then, The Town Bar became a hotbed of radical and revolutionary music making, often enjoined by the visiting avant garde artists from the area. Many of the guests who sat-in to play were from The Detroit Artists Workshop, founded by poet and radical thinker John Sinclair and his wife, Leni.

I began to link more and more with musicians of The Detroit Artists Workshop: trumpeter/composer Charles Moore, composer Jim Semark, bassist John Dana, and drummers Ron Johnson and Danny Spencer. We hosted and participated in concerts with the New York and Chicago avant garde: Archie Shepp, Marion Brown, Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman from The Art Ensemble of Chicago, emanating from the American Association of Creative Musicians. Initially, we were barely tolerated by Detroit’s classical bebop-oriented veteran musicians, but given the social climate of frustration among blacks, artists and young people, we and they knew we were a part of the forces of change. We were eventually accepted and joined in our efforts by some of the local professionals like trombonist George Bohanon and pianist Kirk Lightsey.

Ironically, in the midst of the experimentation and rhetoric of radicalism, I achieved my goal, I learned Bach’s “Goldberg” Variations, performed my masters recital consisting of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor, Schubert’s Sonata in A, D. 959, Chopin’s F minor Ballade, and Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin, and I received my master’s degree in performance in the spring of 1966. This accomplished, I returned briefly to Toledo before finally moving to Manhattan’s midtown far westside by early August.

Stanley Cowell Trio

“Blues For The Vietcong”:

Why did you decide to leave for New York?

I came to New York try my skills alongside my musical heroes, Max, Miles, Art Blakey, Mingus, etc.

What did that change in your life? Your career?

To be hired to play in the bands of my heroes and to travel the world performing became my career and changed my life.

In the 1960s, you were playing with strong leaders: Roland Kirk, Max Roach, Bobby Hutcherson, Marion Brown, Harold Land. What did they explain, transmit or give to you?

They each gave me the opportunity to learn their music and offered me encouragement to discover my musical personality–to play from my heart and soul.

You were associated with the “new thing” scene and nevertheless you published your first record in a classic piano trio formula. Did you separate those two aspects of your career: as a sideman and as a leader?

I had choices as to which style, era, direction, political influence, I might want to pursue as a sideman or as a leader. The « new thing » was about protest and politics for me ; whereas the audiences for which I often played preferred more traditional sounds.

You seem to prefer smaller bands and more particularly the trio. Why? What does that bring to a pianist and composer like you?

It offers a challenge to me to play more interactively with the bassist and drummer ; to debug compositional structures and ideas that could be for bigger ensembles in the future.

During Strata East record sessions, 1970s

You wrote “Travelin man” and played it in 1969 on your first record as a leader. You went on recording and playing quite a few more versions of it. Can it be considered as your anthem? Are you the « travelin man »?

Yes, yes, yes ! The vision for it came in a dream, though.

What about the UK recording ‘Blues For The Viet Cong’? Why were you in Europe at that time and how long did you stay?

I was on tour with Charles Tolliver in the quartet, « Music Inc. » and we stayed for about one month.

How (and when) did you meet Charles Tolliver?

We met at a rehearsal at Max Roach’s house because he was forming a new quintet. We became members of that band in 1967.

Why did you create Strata East together?

We created Strata-East Records to become our own producers and distributors of our music, and to help other artist-producers control their own musical destinies.

“Effi” from ‘Members, Don’t Git Weary’ (1968)

Written by Stanley Cowell

What rôles did each of you have in the label?

Charles became more the person who handled finances, and I became more the expansionist who maintained communications with the growing number of artist-producers who affiliated contractually with SER. We both maintained relations with the media outlets on behalf of the company, and we stressed the idea to the artist-producers that all of us become promotional persons for SER as we toured and performed.

What was the philosophy of this collaborative label?

The concept was that of a condominium. Charles and I created the corporation–in other words, we owned the building. The artist-producers owned their recording(s)–in other words, they owned space in the building. A legal contract agreement was mutually executed by SER and the artist-producers.

During the last twenty years or so, Strata East has become an important reference for the younger génération of Jazz aficionados. How do you explain this late success?

The success was due to hard work by Charles and myself in handling the fabrication and pressing, shipping, getting distribution, radio airplay, and expanding the catalog. SER’s financial arrangement with its artist-producers was revolutionary compared to the traditional record company : 70% of net sales went to the artist-producers. They actually had the power had they been able to come together harmoniously with a development plan.

Would a label like Strata East have more chances of existing today?

Probably.

Do you believe that now, in 2015, Young musicians would have the same difficulties to become known or get signed, or has the internet totally changed the situation?

It seems to me the internet is the music business now for creative music, known as « jazz. » Pop music still operates in the old manner, signing artists and exploiting them via the new media possibilities.

Back then, you formed a team with Charles Tolliver : Music Inc… What was the aesthetic ambition?

The aesthetic ambition was to compose, play and extend the music of our great influences, mentors and innovators, while keeping the distinguishing features of the jazz tradition. Cecil McBee, Charles and I, each contributed music to the Music Inc. repertoire.

After the end of Music Inc, did you continue to see and play with Charles?

I played with Charles occasionally. I wanted to get off the road so I curtailed my touring to teach.

In 2015, you will be in concert with him for the opening night of the Banlieues Bleues festival in Paris. What will be the program, the spirit of the concert?

Powerful rhythmic expression and virtuosity in the style of our collective recordings and performances will be the spirit of this concert.

Both you and Charles Tolliver are somewhat underestimated by the general public, but very well known by musicians. How do you explain this gap?

Jazz and creative, improvised music as a whole has not been a popular music for many years. The sincere, knowledgable jazz fan obviously does know about us, otherwise we would not continue to be invited to record and perform. We have not declined in our skills but have become seasoned, like fine wine.

What about the Piano Handscapes project with Strata-East? Did the idea of 5 pianists playing together come from you?

Pianist, Larry Willis, suggested this idea, and it happened around the same time as other same-instrument collectives began to form in New York.

The whole Superfly Records team loves the tunes where you use the Thumb Piano (“Travellin’ Man” on your solo piano LP, the killer “Smilin’ Billy Suite” on The Heath Brothers album…)! When did you discover the thumb piano? Were you the first to introduce it in jazz records?

My sister, Dolores, gave it to me sometime in the late 1960s. I played it in the Music Inc. band, and entertained myself in hotel rooms as I traveled the world performing. I have used it for encores, on afro-pop and calypso type songs, and with the Heath Brothers accompanying some soft ballads.

You also released ‘Regeneration’, a more soul oriented LP… Why this title?

I was interested in world music and wanted to bring together some of my colleagues who played non-Western instruments, folk music, and jazz.

Audio Player

How did the session take place? And why did you not renew this type of experience with larger bands as opposed your former, smaller bands?

I had the freedom to create and produce what I wanted on Strata-East label but I wanted to improve small ensemble playing with traditional bands, work on my soloing in that context, and bring my composing skills more to the forefront.

In the 1970s you played and recorded a lot. And then suddenly, you stopped recording… What lays behind that choice? What changed?

I made a recording for ECM Records, and made four records for the Galaxy label (Fantasy-Prestige). Then I began teaching in the City University of New York system at Lehman College. I made this decision for the financial security that would allow me to marry and raise a daughter, Sienna. Consequently, I had the option not to take every gigs that was offered. I could avoid the smoky clubs, the late-night life, and the negatives that life style could produce–health issues, etc.

You chose to teach jazz: what we can do, what we owe and what we are passing on? Is there anything that cannot be taught ?

I have a university master’s degree in music as a classical pianist, studied composition, music history and theory, but studied and learned to play and write jazz on my own. So, I was able to teach music history as well as jazz courses. It takes a person with certain acquired skills to transmit knowledge about any subject. I thought I had that potential, so when I was offered the professorship in 1981, I began learning something important to the transmission of the great arts.

If we have the patience, knowledge and wisdom from experience, we can teach jazz or any type of music or art. We cannot necessarily teach the finer points of creativity, style, sensitivity, compassion, value. But we can point the student(s) in that direction. It is up to their evolution and development of skills that will lead them to be able to personalize their craft.

What look to you take on new generations of jazzmen?

The skill level is high in many areas of the art of jazz. Of course, there are so many many branches and styles in the music today–admixtures, global influences, technology, etc.

Why has your music always found its roots in the blues?

I heard it as a child in my house and through my bedroom wisdom at night from a nightclub across the way. « Race » records were the popular source of music in my community. My father catered to musicians in his restaurant and later at is motel. He brought musicians to our home–including Art Tatum. Yes, blues inflection and form still influence my music, tempered by my other cultural and musical experiences.

Do you believe it is still the cement (unconscious) of the musical community in the US?

I think not as much as it was in the 20th century. There are so many students and performers of jazz who come from diverse cultures. Consequently, blues does not express what they feel, nor does it express what they want to express. All artists may be challenged like never before with the wide array of choices and directions. The question remains : How do I personalize this ?

Sometimes, during your career, you were contemplated for bringing in elements from the other Afro-American or African communities. Have you ever felt like you were making a “diasporic” music?

Perhaps, I will again. Right now, though, I am more interested in live electronic processing of my music as is heard on my recent SteepleChase CD, Welcome To This New World. I must mention that I have created a number of diverse works for orchestra, brass ensembles, woodwind quintet, choir, and electronic music since 1988, which have never been recorded. They are available to listen for free on my Google drive at should anyone be interested: https://docs.google.com/folder/d/0B2EgAWPq8mJqUHQxWklyR2c1b28/edit

You have just recorded a new record built around the civil rights movement in the USA. Do you think the musicians, through their compositions, are good witnesses of their time ?

Well, we try ! I suppose the real answer to that will not be known for many years.

How did you compose the repertory of this record ? Was it your idea?

The idea came from two sources : The first came when Vision Fugitive producer, Philippe Ghielmetti , met with me in the US in 2005. He proposed a « Juneteenth » solo project for the label he was producing for at that that time ; the second came from a professor very knowledgeable of African American history suggesting that a composition written for the sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, announcing the freeing of slaves in the US, would be an interesting project to undertake during my 2007 Rutgers University sabbatical. I did not pursue that idea for several years but began to compose it 2012, for concert band, choir, percussion and electro-acoustic sounds. Of course, the work was too large to be performed or recorded before I retired from the university. However, I was able to make a solo piano reduction of most of the score, titled, « Junteenth Emancipation Suite », and this is what I recorded recently for Philippe, along with a 17-minute improvised « recollection » of the suite and a couple of other pertinent songs.

His next record, on Vision Fugitive

Why did you decide to cover “We Shall Overcome”? What does this song represent for you?

It is the anthem of the civil rights era ! It represents faith, the ideal of non-violence, and solidarity with suffering peoples around the world who are trying to free themselves from oppression. Of course, some times this process can morph into violence. Being a jazz musician known for rearranging songs (obscuring the obvious) in order to present them in a new and creative way, I played the melody as the bass part of the song, reharmonized it, and improvised solos above it.

And you linked it to a gospel… Why the gospel? Is it the voice of speechless people?

The gospel piece was included on the « Juneteenth » CD to suggest and reaffirm the power of faith that played such an important role in the civil rights struggle in the US. Gospel and the spiritual song have been a powerful expression of speechless people/disenfranchised people in the US ever since black Americans applied their musics to the theoretical promises found in the Judeo-Christian religious texts.

“Travelin Man”, his classic

At the time of the civil rights movement, you were 20 years old. Were you involved in this fight?

No, not directly. I did not march in the South. But as a black person I felt the anger and frustration, and sympathized with those directly involved in the struggle. Having been born and raised in the North, Toledo, Ohio to be exact, and being in already integrated schools, and not sensing most of the discrimination or bias from white Americans, I led a studious life devoted to music, within a successful and harmonious family, in a predominantly black community. At the age of 19 until 20, I was a student in Austria, far from the civil rights struggle. Upon my return to the US, I became much more aware of the racial divide, discrimination and racism. If you follow the news today with the recent shootings of unarmed black males by police, it may seem that there has been no progress. Be watchful ! Despite having elected a black president, there are racists individuals, anti-black groups, and powerful people that resent the progress of African Americans. And they continue to work to undermine the milestones in economic, legislative and political areas.

Was the jazz community in the front line of the civil rights movement?

Certain ones like Billie Holiday by singing « Strange Fruit », Max Roach, Charles Mingus and Archie Shepp in their famous suites and compositions expressed their indignation with racism and their support of the civil rights movement. They were my influences and mentors toward including a protesting and political bent to some of my works and musical endeavors.

What is the role or the place of a musician in society: the griot? The watchtower? The activist?

I would reply : « all of the above. » We are not just artists, we are citizens of our respective nations, and ultimately, citizens of the world. In our own personal ways, and when necessary, in unity with others, we should add our « fuel » to the cleansing fire against injustice!

On June 19th, 1865 slaves of Texas were the first ones to become “emancipated”, Free! 150 years later, the anniversary is still officially celebrated. 150 years later, were all the problems settled ?

Obviously not!

Thank you for letting me express somethings regarding my life in music, especially jazz, and my feelings on art, life and injustice. Looking forward to returning to Paris in March with Charles Tolliver and the Strata-East All Stars.

This interview is also published, in a shorter version, in Jazz News.

No, not directly. I did not march in the South. But as a black person I felt the anger and frustration, and sympathized with those directly involved in the struggle. Having been born and raised in the North, Toledo, Ohio to be exact, and being in already integrated schools, and not sensing most of the discrimination or bias from white Americans, I led a studious life devoted to music, within a successful and harmonious family, in a predominantly black community. At the age of 19 until 20, I was a student in Austria, far from the civil rights struggle. Upon my return to the US, I became much more aware of the racial divide, discrimination and racism. If you follow the news today with the recent shootings of unarmed black males by police, it may seem that there has been no progress. Be watchful ! Despite having elected a black president, there are racists individuals, anti-black groups, and powerful people that resent the progress of African Americans. And they continue to work to undermine the milestones in economic, legislative and political areas.

Was the jazz community in the front line of the civil rights movement?

Certain ones like Billie Holiday by singing « Strange Fruit », Max Roach, Charles Mingus and Archie Shepp in their famous suites and compositions expressed their indignation with racism and their support of the civil rights movement. They were my influences and mentors toward including a protesting and political bent to some of my works and musical endeavors.

What is the role or the place of a musician in society: the griot? The watchtower? The activist?

I would reply : « all of the above. » We are not just artists, we are citizens of our respective nations, and ultimately, citizens of the world. In our own personal ways, and when necessary, in unity with others, we should add our « fuel » to the cleansing fire against injustice!

On June 19th, 1865 slaves of Texas were the first ones to become “emancipated”, Free! 150 years later, the anniversary is still officially celebrated. 150 years later, were all the problems settled ?

Obviously not!

Thank you for letting me express somethings regarding my life in music, especially jazz, and my feelings on art, life and injustice. Looking forward to returning to Paris in March with Charles Tolliver and the Strata-East All Stars.

This interview is also published, in a shorter version, in Jazz News.

Renowned pianist Stanley Cowell, a Toledo native, talks about Art Tatum

by SALLY VALLONGO

| SPECIAL TO THE BLADE

When Art Tatum (1909-1956) was alive, few Toledoans knew much about their hometown piano genius. Stanley Cowell was among the select few who not only knew Tatum but heard him play in person.

Today, the centennial year of Tatum's birth, as awareness locally begins to match the musician's global reputation, Cowell is coming home to pay a personal tribute to the man many considered a keyboard deity.

Internationally renowned himself as a performer, a composer, and an educator, Cowell makes no pretense about playing at the same speed and complexity his blind hero managed.

That's not his style, then or now.

“Art Tatum's a big mountain to climb,” said Cowell, chairman of the jazz program at Rutgers University in New Jersey, from his Maryland home. Only a few contemporary pianists — Dick Hyman and Adam Makowicz among them — manage to re-create the symphonic virtuosity that distinguishes Tatum's style.

What Cowell does share with his fellow Toledoan is a driving creativity and enormous talent. With plenty of practice, hard work, and vision, Cowell, has scaled an entire range of his own musical peaks.

On Sunday at 7 p.m. he'll perform a concert/benefit in celebration of Tatum's centennial in Owens Community College's Center for Fine and Performing Arts. His appearance in town is sponsored by the African American Legacy Project, a local not-for-profit organization promoting black achievement.

It is one of several Tatum-related events, including a performance Saturday by Johnny O'Neal and a performance Oct. 25 at the Toledo Museum of Art by McCoy Tyner, Benny Golson, and Jon Hendricks.

Tatum was 32 and already making a reputation for himself in New York City when Cowell was born in 1941. A keyboard wunderkind himself, Cowell heard first-hand Tatum's way with a standard tune when the older pianist returned to Toledo for a family visit.

The experience, he recalls, helped define his own artistic path.

“I never wanted to play like Tatum,” he said, “but I've been stamped by the mention of the connection to Tatum in Toledo and the early experience of hearing him in my house.”

Like Tatum, Cowell began playing as a preschooler. He took classical piano training with Mary Belle Shealy and Elmer Gertz and studied organ with J. Harold Harder.

He earned his first music degree at the Oberlin Conservatory, studied further at the Mozarteum Akademie in Salzburg, Austria, and completed his master's degree in music at the University of Michigan.

He exited Ann Arbor and entered the Manhattan music scene, ready to test himself playing with the likes of Herbie Mann, Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Roland Kirk.

Also unlike Tatum, Cowell spread himself into other musical ventures: formation of a record label, organization of ensembles, and, in 1972, the Collective Black Artists, Inc., a performing and advocacy group where he also conducted. Into the 1980s he toured, recorded, and performed with the Heath Brothers Trio.

A Rockefeller Foundation/AT&T Jazz Program grant in 1990 enabled Cowell to compose his Piano Concerto No. 1, dedicated to Tatum and premiered with the Toledo Symphony during a Tatum tribute in 1992 organized by the Toledo Jazz Society and the University of Toledo Humanities Institute.

Sunday's concert will honor Tatum's genius in a very Cowell way.

"I'm playing six note-for-note transcriptions of Tatum," Cowell said. Titles include "Tiger Rag," "Begin the Beguine," "Tea for Two," and "Ain't Misbehavin,'" Tatum's own tribute to Fats Waller.

Cowell's daughter Sunny, a Swarthmore College senior, string player and singer, will join her father to re-create one of the earliest recordings of Tatum: "I'll Never Be the Same."

The second half of the Sunday concert will focus on Cowell's original compositions, including the 1992 Concerto, performed with taped accompaniment prepared by the pianist using state-of-the-art computerized sampling equipment. "There are ‘Tatumisms' in it, of course," Cowell said.

Tickets for the Stanley Cowell concert are $35-$100 at 567-661-2787 or boxoffice@owens.edu.

The African American Legacy Project also will celebrate the genius of Tatum with a special service at 10:30 a.m. Sunday in Grace Presbyterian Church, 1171 Oakwood Ave.

Contact Sally Vallongo at svallongo@theblade.com.

The Stanley Cowell Interview

Listen to an excerpt of the Stanley Cowell Interview:

Stanley Cowell [Download]https://ecmreviews.com/2010/07/22/illusion-suite/

Stanley Cowell Trio: Illusion Suite (ECM 1026)

Stanley Cowell Illusion Suite

Stanley Cowell piano Stanley Clarke bass Jimmy Hopps drums

Recorded November 29, 1972, Sound Ideas Studio, New York

Engineer: George Klabin

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Human beings are adventurous eaters. We are constantly trying new things, loving some and hating others. We change our diets drastically, watching our calories and tallying every morsel we ingest. But sometimes, in the throes and woes of a food culture gone horribly awry, we just want to sit down to a good plate of comfort food, for nothing seems able to replicate the psychological benefits it provides. Stanley Cowell’s Illusion Suite is like that: a heaping portion of comfort food.

Backed by steady support from Stanley Clarke on bass and Jimmy Hopps on drums, Cowell delivers the goods and then some. The timid opening strains of “Maimoun” betray none of the album’s subsequent drive. A confident beat and bowed bass ease us into Cowell’s denser style, made all the more elegiac for its frequent use of octaval doublings in the right hand. (Incidentally, an alternate version of this track worth checking out can be found on Marion Brown’s 1975 Vista.) Cowell kicks off “Ibn Mukhtarr Mustapha” with a sporadic run across the piano before making a deft switch to his electric. Before long, this arid groove quiets into a percussion-heavy outro, bristling with African thumb piano. “Cal Massey” brings us into bop territory, with a great drum kick and deliciously twangy bass line to boot. Smooth is the name of the game is “Miss Viki.” Its fluid bass and wah-pedaled electric piano show off a cool sense of style and finesse. “Emil Danenberg,” named for a former director of the Music Conservatory at Oberlin College in Cowell’s home state of Ohio, is the album’s only ballad to speak of. Its raw, complex chords run straight into the darkest alleys of our internal cities. “Astral Spiritual” is a bit more straightforward, and features some quick turns and fancy musicianship all around. Spectacular drumming and astute pianism abound, ending unexpectedly on a downtempo turn, like an abandoned swing coming to rest. Nostalgic, thought-provoking, and tender, this is fantastic music from a gifted composer and performer that is now easily available thanks to an ECM digital reissue.

http://www.jazz.org/dizzys/events/180281/stanley-cowell-quartet/

With pianist Stanley Cowell, bassist Jay Anderson, drummer Evan Sherman, and saxophonist/flautist Bruce Williams

Eminent pianist Stanley Cowell started his jazz career in the 1960s, working with artists like Max Roach Charles Tolliver, Bobby Hutcherson, and Stan Getz. Of that period of jazz – and of Cowell’s role in it – the New York Times noted an important balance that has always been a constant in Cowell’s art: “music both of reinvention and repertory... original, independent-minded work, comfortable with jazz tradition and common practice but not beholden to it.” The same can be said about every member of his A-list quartet. They perform a combination of originals and well-known tunes, but even the standards are often unique interpretations, broken down and reassembled anew to answer unasked questions like “what if Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie’s breakneck bebop burner ‘Anthropology’ was performed as a loosely timed ballad?” The answers are always worth hearing.

Eminent pianist Stanley Cowell started his jazz career in the 1960s, working with artists like Max Roach Charles Tolliver, Bobby Hutcherson, and Stan Getz. Of that period of jazz – and of Cowell’s role in it – the New York Times noted an important balance that has always been a constant in Cowell’s art: “music both of reinvention and repertory... original, independent-minded work, comfortable with jazz tradition and common practice but not beholden to it.” The same can be said about every member of his A-list quartet. They perform a combination of originals and well-known tunes, but even the standards are often unique interpretations, broken down and reassembled anew to answer unasked questions like “what if Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie’s breakneck bebop burner ‘Anthropology’ was performed as a loosely timed ballad?” The answers are always worth hearing.

Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola

Broadway and 60th Street

5th Floor

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/19/arts/music/review-stanley-cowell-in-a-rare-performance-at-the-village-vanguard.html

Broadway and 60th Street

5th Floor

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/19/arts/music/review-stanley-cowell-in-a-rare-performance-at-the-village-vanguard.html

Music

Review: Stanley Cowell, in a Rare Performance at the Village Vanguard

From left, Stanley Cowell, Jay Anderson and Billy Drummond at the Village Vanguard.

Credit

Michael Appleton for The New York Times

A

standard description of a jazz performance begins with a couple of

isolated moments or events. Somebody played something, it had meaning or

an impact, time stopped, the audience smiled. The pianist Stanley

Cowell is leading a band at the Village Vanguard for the first time this

week, and describing his early set there on Wednesday in those terms is

no problem.

One:

Mr. Cowell played a radically slowed-down version of the bebop tune

“Anthropology,” transforming a song of condensed velocity from 1945 into

a floating ballad with no particular time stamp. Two: He improvised on

the club’s acoustic piano through a digital sound-design program called Kyma,

which altered the attack, pitch and texture of the piano notes, echoing

them or scrambling their meaning and making them sound like gravel or

ice or bells. He turned the effect on and off several times by means of a

microphone leading to a laptop, and he used it sparingly. Those

stretches were weird but confident; he incorporated the sounds into the

straightforward swing of his quartet, with the alto saxophonist Bruce

Williams, the bassist Jay Anderson and the drummer Billy Drummond.

So,

Mr. Cowell can create impressive momentary events, but what’s best

about him is his broad frame of reference and the general synthesis he

is proposing.

He

played a number of other songs, too, including his own “Equipoise” and a

samba-swing version of Tadd Dameron’s “Hot House.” But I recall a

version of “Anthropology” and some use of digital sound processing from a

set he played 18 years ago at Sweet Basil, which was the last time Mr.

Cowell, now 74, led a band for a week at a jazz club in New York. Those

experiments didn’t sound trendy for that time in jazz, nor do they now

for this one. They have longer range.

Mr.

Cowell emerged in the late 1960s, playing with Max Roach, Charles

Tolliver and others, when jazz was starting to be widely understood as a

long historical continuity, a music both of reinvention and repertory.

On his own he created a lot of original, independent-minded work,

comfortable with jazz tradition and common practice but not beholden to

it. In the 1990s he began recording less, and performing much less. For

33 years he was a tenured professor at Rutgers and other universities;

for about 10 of those years, during the aughts, he didn’t make records

at all.

But

recently he has stepped back from teaching, which seems to be freeing

him up for other things again. He has made a few albums over the past

five years and has a striking new one, “Juneteenth” (Vision Fugitive), a

solo-piano reduction of music that was originally written for concert

band, choir and electronics and is associated with African-American

freedom movements. And his Vanguard performance seemed like an index of

what we’ve been missing. He played postbop originals and blues language

and jarring electro-acoustic music; he articulated Art Tatum-like

flourishes and runs as a matter of course, no matter the context; and he

ended his set with a song played on African thumb-piano.

Mr.

Cowell is a bit unclassifiable, and jazz has a lot of use for his

curiosity and challenge and friction, as well as his virtuosity. If this

is the start of a new phase — if he begins performing more and

integrating himself into the wider public world of jazz and improvised

music — it could be interesting.

Stanley Cowell performs through Sunday at the Village Vanguard in Manhattan;

212-255-4037, villagevanguard.com.

A version of this review appears in print on June 19, 2015, on Page C4 of the New York edition with the headline: Back Onstage, to Show the Jazz Audience What It’s Been Missing. 212-255-4037, villagevanguard.com.

https://jazztimes.com/features/stanley-cowell-never-too-late/

Stanley Cowell: Never Too Late

A pianist-composer's late-career renaissance

10/08/2015

We’ve just spent two hours conversing in his basement. He’s been gracious and forthcoming, but also been cerebral and soft-spoken-not cold, but reserved. That fades during his 10 minutes at the piano. As he transforms “‘Round Midnight” into “an upside-down version,” demonstrates another effect with his own melody “St. Croix” and tools around with phrases from his new solo recording, Juneteenth (Vision Fugitive), his eyes light up and his voice gains volume and merriment. “Now to do all that in rhythm!” he exclaims, and lets out a throaty chuckle. “It was cool. People wanted more of it!”

If music animates Cowell, the reverse is also true, and his incorporation of the Kyma, which he’s used for nearly 20 years, is living proof. “Stanley’s always been an inspiration because he’s not a stagnant artist,” says drummer Nasheet Waits, who worked with Cowell in the 1990s. “He’s always exploring, coming up with new ways to express himself.”

Cowell is no stranger to tradition, either. His initiation into jazz came at age 6, in his Toledo, Ohio home, where he watched his father’s friend Art Tatum play the family’s spinet piano. In the ensuing decades, a deep understanding of the jazz lineage mingled with Cowell’s innovative spirit and came to define his music. By the early ’80s he boasted an unimpeachable résumé, including sideman work with iconic leaders, his own powerful recordings and even co-ownership of a game-changing label. All of which added to the loss the jazz scene felt starting in 1981, when Cowell largely shifted his focus from performing to educating. He began teaching fulltime that year and continued for the next 32, first at CUNY’s Lehman College, then at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

But his 2013 retirement from Rutgers has brought him back onto the bandstand, culminating in his week at the Vanguard. “Part of my bucket list!” Cowell says proudly. “It took 74 years to get there. So don’t give up!”

******

Cowell’s bucket list has to be a short one, considering the number of accomplishments he’s already checked off. He graduated from Oberlin college in 1962 and arrived in New York in the summer of ’66, working first with saxophonist Marion Brown and other “out” players. But in 1967 he passed an audition for Max Roach’s quintet. The legendary drummer’s band also included the young trumpeter Charles Tolliver, with whom Cowell bonded immediately. “We just had the right vibes, the right affinity,” Tolliver says. “We bonded … from the start,” he continues, and he remains Cowell’s closest friend today.

Roach’s band was really “the beginning of everything,” Cowell says. From there, the pianist got a call to tour with Miles Davis, and joined the Bobby Hutcherson-Harold Land Quintet as well. In 1969, he toured with Stan Getz’s quartet, and made his first two albums under his own name.

The 1970s are often dismissed as meager years for jazz; for Stanley Cowell, they were bullish. He and Tolliver left Roach in 1970 to form Tolliver’s quartet Music Inc., which in November 1970 made its first studio recording, Music Inc. After getting no takers among the labels, Tolliver and Cowell decided to put it out themselves. “This was part of [Nguzo Saba], the seven principles of African Heritage,” Cowell explains. “Kind of a rebuilding thing, coming out of the need to take over our own resources. But it moved from a racial idea to an entrepreneurial idea.”

Two of Cowell’s friends from Michigan had formed a corporation called Strata. “We told them that we were going to issue this new recording. They said, ‘Well, why don’t you guys become the Eastern leg of our thing?'” Tolliver recalls. “To make a long story short, I decided that we would not become a part of the Strata Corporation but would definitely use the name Strata-East.” It would become one of the most important independent jazz labels of the decade.

Cowell also cofounded the Collective Black Artists, in another outgrowth of Nguzo Saba’s principle of self-determination. “We decided that we wanted to bring African-American artists more to the fore, in presentation and recording and so forth,” he says. “We did a lot of concerts, took music into prisons, into schools. It survived a long time.”

Throughout it all, Cowell’s musical career was blossoming. Between 1973 and 1981, he recorded nine albums. Two found him leading an ensemble called the Piano Choir-a seven-keyboard ensemble that blended acoustic and electric pianos, organ, harpsichord and an array of synthesizers. He was also a prolific freelancer, touring and recording with bassist Richard Davis, drummer Roy Haynes and saxophonist Art Pepper, among others. So prolific was he, Cowell notes, that Tolliver was left to operate Strata-East. “I got so busy performing,” Cowell says, “I thought that Strata-East was gonna run by itself.”

Among his sideman gigs was a roughly decade-long one as pianist for the Heath Brothers-the only member of the quartet who was not a family member. “Stanley Cowell was the adopted and well-respected other Heath Brother,” laughs Jimmy Heath, the saxophonist and middle brother of the group.

******

Teaching wasn’t the only thing that distanced Cowell from active performance. The smoke that accumulated in the jazz clubs was a major irritation, especially on tour. “The Japanese and the French used to come and gang-smoke!” he says. “It’d be a mushroom cloud of smoke all over the place!” In addition, he’d married and had a daughter, and in 1988 the family moved to Upper Marlboro, Md., about 45 minutes outside D.C., though they bought a second home in New Jersey to ease Cowell’s commute to Lehman.

But none of these were obstacles to his creativity. Cowell continued to develop as a musician and composer, to develop and innovate, and now he was assisted by the resources of academia. For one thing, he had access to student ensembles, and not just in jazz. Cowell began building an impressive résumé of orchestral works: short pieces for solo or small ensemble as well as long-form sonatas, concerti and suites. “I used their symphony, wrote for their brass choir, wrote for their woodwind quintet and combined jazz soloist with those ensembles-either myself or, on one piece, the Asian Art Suite, the whole faculty.” Cowell is particularly proud of the Asian Art Suite, a three-part, seven-section composition for orchestra, percussion and jazz sextet that he premiered at Rutgers in 2009. “It’s a fun piece,” he says. “It’s based on a commission from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, inspired by their Asian collection.” (It has never been issued as a recording, although excerpts appear on his 2012 album, It’s Time, on SteepleChase. That prolific but low-profile Danish outfit was Cowell’s label of choice during the ’90s. After not recording for over a decade, he returned to the fold for It’s Time and 2013’s Welcome to This New World, a quartet date featuring guitarist Vic Juris.)

While writing his first orchestral piece in the early ’90s, Cowell, using a boxy IBM computer, began learning “a very early, unstable version of the notation program called Finale.” The long process of composing allowed him to become quite practiced in the program. “I got into electronic music, experimenting with that,” he says, “[enough that] in ’97 I took over the electronic music class at Lehman.”

Much of the equipment was still analog, but Cowell steered it toward digital, and it was in this capacity that he began working with the Kyma. “I got a grant to [purchase] it,” he says. “I used it at a concert when I started teaching the electronic course.” He began incorporating the system into his orchestral work as well: A piece commemorating the Emancipation Proclamation was composed for concert band, chorus and Kyma. “He’s just that kind of person: open always to new happenings,” says Heath. “We went to Japan, and I bought my first keyboard, and he had it all figured out by the time we got home. He taught me a lot about the computer over the years, too.”

Further, Cowell hadn’t completely abandoned live performance. In fact, whereas he had rarely led bands in earlier years, in the mid-’90s he formed a real working quartet: Bruce Williams on alto saxophone, Dwayne Burno on bass and Keith Copeland on drums. Copeland was soon replaced by Nasheet Waits, who has known Cowell since the pianist was a neighbor of Waits’ father, drummer Freddie Waits, in New York’s Westbeth Artists Housing complex. “The music was challenging and engaging,” Williams recalls. “We would hook up every couple months, at the minimum three times in the year, for a weeklong stint. For a working New York jazz band, that’s kind of a lot unless you’re on the road.”

******

Cowell’s first major orchestral work, completed and premiered in 1992, was his Piano Concerto No. 1, a tribute to Art Tatum. As a native of Tatum’s hometown of Toledo, Cowell was more captive to his influence than most jazz pianists-many of his mentors were Tatum’s contemporaries and protégés-not to mention the effect of witnessing a performance of “You Took Advantage of Me” in his own childhood living room. When Cowell recorded his 1969 debut as a leader, Blues for the Viet Cong, he included a rollicking solo stride rendition of that same tune. “Somewhere that just came off the top of my head,” he says. “I didn’t know why. I realized later, ‘Well, that’s where that came from.'”

Cowell’s version didn’t really sound like Tatum. Nor did the rest of his early recordings. His sound was based instead on Bud Powell, Phineas Newborn and ’60s innovators like McCoy Tyner and Herbie Hancock. As the ’70s progressed, he took on polyrhythmic West African influences and became skilled on the mbira, or thumb piano. But during the ’80s, perhaps as a side effect of teaching jazz history, Tatum came creeping back in; his rhythmic and harmonic signatures are prominent, for example, on Cowell’s 1983 album Such Great Friends.

In 1990, the master asserted himself in a big way. “I never wanted to play like Tatum, but the Charlin Jazz Society kind of steered me in that direction,” he says, “by offering me a grant to develop a concert of Tatum’s transcriptions and whatever I could ape, so to speak. So I did 22 of his pieces in the concert. Some of them were transcriptions and the others were close interpretations of the songs that he played.” Shortly afterward, he began the concerto. “I had already isolated quite a few of Tatum’s ideas, and kind of sprinkled them about, as one reviewer said, into the piano concerto.”

From then on, Tatum was simply another element in the nuanced tapestry that is Cowell’s music. Juneteenth-a “reduction” of his piece on the Emancipation Proclamation, now applied more broadly to the struggle for civil rights-never overtly addresses Tatum, but it does abstract and, yes, sprinkle his conception throughout, along with ideas from other historical jazz pianists. That blend is filtered through an approach to voicing and space that is Cowell’s alone, and as a result those influences are subsumed into his sound. Indeed, Juneteenth may be the most distinctly Cowell-ian of all his albums, particularly on the improvised closing track, “Juneteenth Recollections.” “His music is unique. It’s not like anyone else’s that I know,” says Heath. “He’s not strictly a bebopper, and he’s not strictly from the Tatum school. He’s got his own voice in this world. He has things as avant-garde as Ornette Coleman and that era of music. The whole spectrum of African-American classical music. And he never forgets the history of African-American people, and he tries to do everything he can to better our position in the world.”

******

Throughout his time as an educator, Cowell took a few sabbaticals to work on his music. He embarked on one of these breaks in 2013, he says, “and then just decided to stay out. They had me come back for graduation and commencement that year, and treated me lovely.” At 72, he was finally retired.

Which gave him the opportunity to come out of his quasi-retirement from live performance. Jazz clubs around the world had adopted smoke-free policies, which Cowell relished, and he made his way into concert halls, including London’s prestigious Barbican. In March, he reunited with Tolliver, singer Jean Carne, tenor saxophonist Billy Harper, bassist Cecil McBee and drummer Alvin Queen to tour the U.K. as the Strata-East All Stars. “The Brits, like the Japanese, are forever in love with the Strata-East happening,” says Tolliver. “And a world-famous DJ there [Gilles Peterson], who grew up on Strata-East, found out that we were alive and well. He put it together.”

Then there was the weeklong bucket-list stint at the Vanguard. Cowell’s friends in the music visited throughout the week, among them Heath, Waits and Tolliver. Bruce Williams played in the quartet, along with bassist Jay Anderson and drummer Billy Drummond, and found that after more than two decades the pianist still found ways to inspire and teach. “The mentoring in jazz a lot of times is not like sitting at a desk with someone at a blackboard, it’s more like real-life experience,” Williams says. “It’s always a challenge, but a beautiful thing. … Stanley’s clearly one of the best there’s ever been.”

“Now he’s coming back out here, and I wish him all the best,” says Heath. “He deserves it.”

https://www.npr.org/event/music/401945018/stanley-cowell-on-piano-jazz

Marian McPartland hosts pianist Stanley Cowell for this 1999 episode of Piano Jazz, recorded before an audience at NPR's studios in Washington. Known for his brilliant and highly personal approach, Cowell bridges traditional and contemporary styles of jazz. He and McPartland challenge each other in inventive duets, and Cowell performs his composition "Equipoise."

Originally broadcast in the winter of 1999.

Set List:

- "Bright Passion" (Cowell)

- "Anthropology" (Parker, Gillespie, Bishop)

- "Love Walked In" (Gershwin, Gershwin)

- "Warm Valley" (Ellington)

- "Equipoise" (Cowell)

- "Waltz for Debby" (Evans, Lees)

- "Tenderly" (Gross, Lawrence)

- "Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise" (Romberg, Hammerstein)

THE MUSIC OF STANLEY COWELL: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH STANLEY COWELL:

Maimoun - Stanley Cowell (Solo Piano)

Sweet Song - Stanley Cowell

Japan Journal- Stanley Cowell Interview

Sweet Song - Stanley Cowell Solo Piano

Charles Tolliver - Brilliant Circles

Composition by Stanley Cowell:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Cowell

Stanley Cowell

Stanley Cowell playing with The Heath Brothers in Rockefeller Center, June 1977