AS OF JANUARY 13, 2023 FIVE HUNDRED MUSICAL ARTISTS HAVE BEEN FEATURED IN THE SOUND PROJECTIONS MAGAZINE THAT BEGAN ITS ONLINE PUBLICATION ON NOVEMBER 1, 2014.

ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND HERE, WHERE YOU CAN FIND THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND ‘LABELS' (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/02/mary-lou-williams-1910-1981-brilliant.html

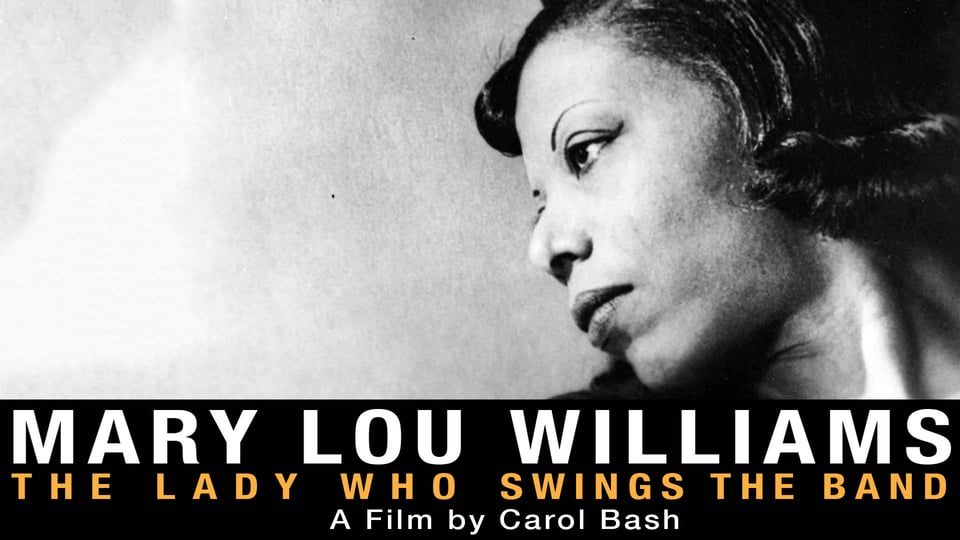

PHOTO: MARY LOU WILLIAMS (1910-1981)

Mary Lou Williams

(1910-1981)

Biography by Scott Yanow

Mary Lou Williams, ca. 1946.

William P. Gotlieb/Library of Congress via flickr.comJust the fact that Williams and Duke Ellington were virtually the only stride pianists to modernize their style through the years would have been enough to guarantee her a place in jazz history books. Williams managed to always sound modern during a half-century career without forgetting her roots or how to play in the older styles.

Born Mary Elfrieda Scruggs (although she soon took the name of her stepfather and was known as Mary Lou Burley), she taught herself the piano by ear and was playing in public at the age of six. Growing up in Pittsburgh, Williams' life was always filled with music. When she was 13, she started working in vaudeville, and three years later married saxophonist John Williams. They moved to Memphis, and she made her debut on records with Synco Jazzers. John soon joined Andy Kirk's orchestra, which was based in Kansas City, in 1929. Williams wrote arrangements for the band, filled in for an absent pianist on Kirk's first recording session, and eventually became a member of the orchestra herself. Her arrangements were largely responsible for the band's distinctive sound and eventual success. Williams was soon recognized as Kirk's top soloist, a stride pianist who impressed everyone (even Jelly Roll Morton). In addition, she wrote such songs such as "Roll 'Em" (a killer hit for Benny Goodman) and "What's Your Story Morning Glory" and contributed arrangements to other big bands, including those of Goodman, Earl Hines, and Tommy Dorsey.

Mary Lou Williams stayed with Kirk until 1942, by which time she had divorced John Williams and married trumpeter Harold "Shorty" Baker. She co-led a combo with Baker before he joined Duke Ellington. Williams did some writing for Duke (most notably her rearrangement of "Blue Skies" into a horn battle called "Trumpets No End") and played briefly with Benny Goodman's bebop group in 1948. She had gradually modernized her style and by the early to mid-'40s was actively encouraging the young modernists who would lead the bebop revolution, including Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, Tadd Dameron, and Dizzy Gillespie. Williams' "Zodiac Suite" showed off some of her modern ideas, and her "In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee" was a bebop fable recorded by Gillespie.

Williams lived in Europe from 1952-1954 and then became very involved in the Catholic religion. She retired from music for a few years before appearing as a guest with Dizzy Gillespie's orchestra at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival. Williams returned to jazz and by the early '70s sounded more like a young modal player (clearly she was familiar with McCoy Tyner) than a survivor of the 1920s. Although she did not care for the avant-garde, she occasionally played quite freely, although a 1977 duo concert with Cecil Taylor was a complete fiasco. Williams wrote three masses and a cantana, was a star at Benny Goodman's 40th-anniversary Carnegie Hall concert in 1978, taught at Duke University, and often planned her later concerts as a history of jazz recital. By the time she passed away at the age of 71, she had a list of accomplishments that could have filled three lifetimes.

Mary Lou Williams recorded through the years as a leader for many labels including Brunswick (a pair of piano solos in 1930), Decca (1938), Columbia, Savoy, extensively for Asch and Folkways during 1944-1947, Victor, King (1949), Atlantic, Circle, Vogue, Prestige, Blue Star, Jazztone, her own Mary label (1970-1974), Chiaroscuro, SteepleChase, and finally Pablo (1977-1978).

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/mary-lou-williams

Mary Lou Williams

Imagine a pianist playing concerts with Benny Goodman and Cecil Taylor in successive years (1977-78). That pianist was Mary Lou Williams. In a career which spanned over fifty years Mary was always on the cutting edge.

She was born Mary Scruggs in 1910 Atlanta. Her mother was a single parent who worked as a domestic and played spirituals and ragtime on piano and organ. At age three Mary shocked her by reaching up from her mother's lap to pick out a tune on the keyboard. Rather than hiring a teacher (for fear the child would lose the ability to improvise) Mary's mother invited professional musicians to their home. By watching, listening and heeding their advice, Mary learned well, especially the importance of a strong left hand. By age six, dubbed "The Little Piano Girl of East Liberty", she was playing for money around her new home of Pittsburgh, Pa. Her early years included listening to piano rolls of James P. Johnson and Willie "The Lion" Smith, records of Jelly Roll Morton and seeing Earl Hines play at youth dances. At age twelve she went on the road during school vacations with a vaudeville show. Three years later she quit high school to join the very successful vaudeville team Seymour and Jeanette. Here she met saxophonist John Williams, whom she married at sixteen. When John got the call to join Terrence Holder's band in Oklahoma, Mary took charge of his band, the Synco-Jazzers, in Memphis (Jimmie Lunceford was a member).

By the time Mary joined John out West, Holder was out and Andy Kirk had become the leader of the Twelve Clouds of Joy. Because the band already had a pianist, Mary just filled in. By day, however, she was feeding tunes and arranging ideas to Kirk (at this point she had little knowledge of theory or notation). She soon tired of this process and began writing arrangments herself, influenced by the style of Don Redman. Contrary to Kirk's advice she wrote sixth chords and unlike most arrangers of the time combined instruments from different sections. Ultimately she would become the band's full-time pianist, primary soloist and arranger. During the '30's she also wrote arrangements for Goodman (Roll 'Em, Camel Hop), Lunceford (What's Your Story, Morning Glory?), the Dorseys, Casa Loma, Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway and others.

Kirk's band was a scuffling territory band in its early days. But the band was based in a place Mary called "a heavenly city", Kansas City. With fifty clubs and a political machine tied to bootlegging and gambling interests, the city was nearly Depression-proof for jazz musicians. The best musicians from the Southwest and Midwest flocked there and many nationally-known musicians stopped there to jam while on tour (this is depicted in Robert Altman's movie "Kansas City", with pianist Geri Allen playing the part of Mary Lou). Mary participated in the jams often, including the famous night when Coleman Hawkins tried to cut the local tenor men, including Ben Webster, Lester Young and Herschel Evans.

The Kirk band became nationally prominent after a 1936 Decca recording. Mary stayed another six years, at which point she was tired of touring and pay inequities. David Baker has said "Particularly given those years, 1929-42, it was almost without precedence to have a female in the band who wasn't a singer and secondarily for that female to virtually all the musical decisions in her hands. Mary Lou Williams had the enviable position of being the person who shaped virtually the entire history of a band". Of her piano prowess in Kansas City, Count Basie said "Anytime she was in the neighborhood I used to find myself another little territory, because Mary Lou was tearin' everybody up". Saxophonist Buddy Tate seconded this in Joanne Burke's documentary on Mary Lou when he said "She was outplaying all those men. She didn't think so but they thought so".

Mary returned to Pittsburgh, uncertain whether she'd keep performing. Local drummer Art Blakey, then 18, convinced her to put together a band, including second husband Harold "Shorty" Baker. Six months later she and Baker joined Duke Ellington's orchestra, Mary as staff arranger. Her most prominent arrangement, "Trumpets No End", based on "Blue Skies", was recorded in 1946. After six months she left Duke and Baker, moving to New York City. Thus began a rich, productive period as a performer and composer. She played long-standing gigs at Cafe Society, had her own radio show on WNEW, composed "Zodiac Suite", which was performed by a summer orchestra of the New York Philharmonic, and recorded with a trio. Her tiny apartment in Harlem became a headquarters where the pioneers of modern jazz, among them Monk, Dizzy Gillespie and Tadd Dameron, gathered to share ideas, compose, listen to records and get advice from their new mentor, Mary Lou. Unlike most of her peers, Mary loved what the "boppers" were doing. Among her contributions to the modern jazz movement were the tune and arrangement "In the Land of Oo-Bla-Dee", which Dizzy's big band recorded, and a couple of tunes she convinced Benny Goodman to record with his brief bop-oriented small group.

A nine-day job in England in 1952 stretched into two years performing throughout Western Europe. She was an immense hit in Paris. One night, however, she walked off the stage in a state of emotional collapse, spending the following months in the countryside resting and praying. Upon returning to the States her performance activities were limited. Her energies were devoted mainly to the Bel Canto Foundation, an effort she initiated to help addicted musicians return to performing. In support of this effort she ran two thrift stores. She and Dizzy's wife Lorraine converted together to Catholicism. Two priests and Dizzy convinced her to return to playing, which she did at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival with Dizzy's band. Throughout the 1960's her composing focused on sacred music - hymns and masses. One of the masses, "Music for Peace", was choreographed and performed by the Alvin Ailey Dance Theater as "Mary Lou's Mass". In this period Mary put much effort into working with youth choirs to perform her works, including mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York before a gathering of over three thousand.

Father Peter O'Brien became her close friend and personal manager in the 1960's. Together they found new venues for jazz performance at a time when no more than two clubs in Manhattan had jazz full-time. In addition to club work Mary played colleges, formed her own record label and publishing companies, founded the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival and made television appearances.

Throughout the 1970's her career flourished, including numerous albums. In 1977 she accepted an appointment at Duke University as artist-in-residence, co-teaching the History of Jazz with Fr. O'Brien. With a light teaching schedule, she also did many concert and festival appearances, conducted clinics with youth and performed at the White House concert hosted by President Carter. While she was hospitalized with cancer in 1981, she received Duke's Trinity Award for service to the university. She died in May of that year.

Beyond her numerous recordings, compositions (approx. 350) and arrangements, her legacy lives on in many ways. There's Joanne Burke's 1989 film "Music on My Mind". She is featured in the 1994 documentary "A Great Day in Harlem". The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. has an annual Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival in May. Linda Dahl, author of the book Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen, has recently completed a biography of Mary Lou to be published this year. The Mary Lou Williams Foundation, to which she bequeathed most of her assets, continues pairing young musicians ages six to twelve with professionals. Her archives are preserved at Rutgers University's Institute of Jazz Studies in Newark.

https://www.npr.org/2010/05/07/126613987/mary-lou-williams-a-centennial-celebration

Music Interviews

Mary Lou Williams: A Centennial Celebration

It's late on a rainy Monday night, and a quartet is swinging the back room of a Times Square pub. On the surface, it appears to be just another gig. Really, it's a harbinger of things to come.

The jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams would have been 100 years old Saturday. And musicians, like Virginia Mayhew, are paying tribute in concerts from Madison, Wis., to Princeton, N.J. In a few weeks, the saxophonist and dozens of others will take the stage at the Kennedy Center for the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival.

"I think she is probably the greatest female jazz player who has ever lived," Mayhew says. "Really, I do think that. But I look forward to when the female part of it is irrelevant."

Hear Mary Lou In Performance

Click on the following links:

Fearless Role Model

More About Mary Lou

In jazz, where the ranks of instrumentalists are still dominated by men, Williams' status as an early female pioneer has turned her into a symbol embodying women in jazz. While female performers tend to be on guard against tokenism and the separate but so often unequal acknowledgment of their contributions, they're clear in their approbation of Williams' talents and her value as a role model.

"Her fearlessness and self-determination, I think that is an inspiration, when you see a person so clearly confident in their voice," says pianist Geri Allen, who played the role of Mary Lou Williams in the Robert Altman film Kansas City. "Because of her and her excellence, and because of her commitment to this very pristine level of artistry, my generation of players who are women don't have to go through that kind of resistance. I can't imagine it, to tell you the truth."

Williams was so exceptional, and carried herself with such dignity, it's difficult to imagine that she could face any resistance. Born Mary Elfrieda Scruggs, she grew up in Pittsburgh and was playing practically from the time she could walk. Her mother would practice on an old-fashioned pump organ and kept the toddler in her lap to keep her out of mischief.

"One day, when she was pumping the organ, my fingers beat her to the keyboard and began playing," Williams said. "And it must have been great, because she ran out and got the neighbors to listen to it."

Williams began working professionally at 7 and was touring on the Orpheum circuit by 14. She married the saxophonist John Williams, and the couple became members of Andy Kirk's Twelve Clouds of Joy.

Working as not only the band's pianist, but also its arranger and composer, Williams soon attracted attention. Earl Hines, Tommy Dorsey, Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman all wanted her to write for them.

"She was one of the swingin'-est people I've ever played with," pianist Billy Taylor says. "I mean, she would swing you into bad health."

Teaching Bud And Monk

Taylor founded the festival at the Kennedy Center in Williams' honor. He says that, unlike others of her generation, she continued to be on the cutting edge. Her Harlem apartment, around the corner from Minton's Playhouse, became a kind of salon for the progenitors of bebop in the early 1940s. Taylor was there.

"I remember one time, she said to me, 'Billy, can you come on over to the house tomorrow? I'm having [Thelonious] Monk and Bud [Powell] over because I've got to do something about the way they touch the piano,' " Taylor says. "I said, 'What you talking about?' "

With their percussive approaches to the instrument, Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell weren't exactly known for having a light touch.

"She was saying the piano responds in a certain way," Taylor says. "You can't just bang away and say I'm getting the sound I want. There is no question, but if you go back and listen to certain records that were played back in that period, you hear a difference. There's a difference in Monk's sound, and there's a difference in Bud's sound."

An Unsung Hero of Jazz History

Musical documentary

Directed by Carol Bash

2015

1hr 13min

She was ahead of her time, a genius. During an era when Jazz was the nation's popular music, Mary Lou Williams was one of its greatest innovators. As both a pianist and composer, she was a font of daring and creativity who helped shape the sound of 20th century America. And like the dynamic, turbulent nation in which she lived, Williams seemed to redefine herself with every passing decade.

From child prodigy to "Boogie-Woogie Queen" to groundbreaking composer to mentoring some of the greatest musicians of all time, Mary Lou Williams never ceased to astound those who heard her play. But away from the piano, Williams was a woman in a "man's world," a black person in a "whites only" society, an ambitious artist who dared to be different, and who struggled against the imperatives of being a "star."

Winner of Outstanding Independent Documentary at the Black Reel Awards. Winner of the HBO Competition Award for Best Documentary at Martha's Vineyard African American Film Festival.

Soul on Soul: The Life and Music of Mary Lou Williams

by Tammy Kernodle

http://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2015/02/mary-lou-williams-1910-1981-brilliant.html

Mary Lou Williams - Zodiac Suite-- (full album)—1945

1. Aries 0:00

2. Taurus 1:52

3. Gemini 4:29

4. Cancer 6:44

5. Leo 9:21

6. Virgo 11:08

7. Libra 13:40

8. Scorpio 15:53

9. Sagittarius 18:59

10. Capricorn 20:54

11. Aquarius 23:37

12. Pisces 27:20

13. Aries 29:57

14. Cancer 32:28

15. Virgo 34:59

16. Scorpio 37:48

17. Aquarius 41:02

https://www.discogs.com/Mary-Lou-Will...

Mary Lou Williams & Cecil Taylor - "Ayizan"

Piano duet

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6lcJKmgIAHU

Mary Lou Williams Interview (1976)

Interview of Mary Lou Williams at the Statler Hotel, Buffalo, NY Winter 1976. Still photographs are from -A Great Day In Harlem:

Mary Lou Williams at Les Mouches, NYC, 1978. Cabaret Show, Carline Ray:

Legendary jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams performs a one-hour cabaret show at Les Mouches in NYC, 1978. Carline Ray, one of the original Sweethearts of Rhythm, is on bass.

Mary Lou Williams: Into the Zone of Music

"In Kansas City I came up with chords that they are only starting to use now."—Mary Lou Williams

Mary Lou Williams was born in Atlanta, Georgia on May 8, 1910, as Mary Elfrieda Scruggs. She grew up with an absent mother who drank, and the father was not in the picture, so little Mary grew up much too soon. Williams' turbulent story is told in Linda Dahl's highly recommended biography, Morning Glory (1999), and is the stuff legends are made of. Like Billie Holiday and Bessie Smith, she went through much suffering, but Williams' story is not tragic, but borne of a luminous love for music which took on a religious glow later in her life.

Already as a child she experienced visions and in the same way she had a special understanding of music. She has once told how she heard a musician and could predict the next note that would come.

The ability to take in the music was not just passive. When she was about three years old, she sat on her mother's lap and heard her play a tune on a small parlor organ. Subsequently, she impulsively emulated the melody so convincingly that her mother lost her in astonishment. She could listen and, not least, transfer her own listening to playing and creating music. This ability became the most important prerequisite for her early musical education, which took place in Pittsburgh. A Catholic choir in particular made an impression. A seed was sown and later blossomed in the form of her own religious music, in which she also included choirs. However, there was not much piety in the environment where she grew up and she escaped from violence and racism through music.

Music became both her escape and livelihood. Nicknamed The Little Piano Girl of East Liberty, she earned money as a pianist for silent films. In addition, she played at parties, but this kind of work wasn't what she dreamt of, and she longed to get away from Pittsburgh.

At just eleven years old, she had already been on her first tour accompanied by a guardian when she performed with the vaudeville show Hits and Bits. The first real opportunity to get away presented itself when she met her future husband, John Overton Williams, and in 1925 joined his group, The Syncopators. It was the start of a tough but fruitful life of touring and at the center of this early phase of her career was a very special group.

Clouds of Joy in Kansas City

The 108 compositions she recorded with Andy Kirk and his orchestra became part of the jazz canon and can be highlighted as a definitive example of the swinging Kansas City style. In Kirk's band, Williams grew not only as an instrumentalist, but especially as a composer and arranger. She learned to arrange by watching Kirk and her learning curve was frighteningly fast. Soon the orchestra benefited from her skills as an arranger and she also contributed to their repertoire with compositions such as "Mary's Idea," "Walkin' and Swingin,'" "Lotta Sax Appeal" and "Twinklin.'" Already at this time she had an experimental approach to her work. As she is quoted for saying in the liner notes to the record A Keyboard History (1955):

"In Kansas City I came up with chords that they are only starting to use now."

Alongside her work for Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy, Williams also began to be in demand as an arranger for other musicians and her employers included names such as Louis Armstrong, Earl Hines, Dizzy Gillespie and Benny Goodman.

Her abilities as an arranger, soloist and composer eventually also made it possible to leave Kirk, who did not appreciate her enough. The lack of financial recognition was unfortunately a recurring problem throughout her career.

In 1942, she left both John Williams and Kirk's orchestra in favor of her new husband, trumpeter Harold "Shorty" Baker. Baker later came to play in Duke Ellington's orchestra in New York and Williams got work for Ellington as an arranger. Neither the relationship with Baker nor the permanent job with Ellington lasted long, but she still delivered around 47 arrangements for Ellington's orchestra in the period from the '40s to the '60s. He also expressed great respect for her. Famously, he said about her:

"Her writing and performing are and have always been just a little ahead throughout her career. Her music retains and maintains a standard of quality that is timeless. She is like soul on soul."

In the Sign of the Stars

In addition to her regular engagement at The Café Society, she had the radio show Mary Lou Williams's Piano Workshop and for this she composed the first pieces. The rest of the total of twelve pieces that make up the suite were created via improvisation. The inspiration came from astrology with zodiac signs, which also functioned as small musical portraits, for instance is Aries dedicated Ben Webster and Billie Holiday, both born in that particular sign.

With its blend of jazz and a classically structured work, The Zodiac Suite represented something new. The radio audience also welcomed the music and in 1945 it was recorded and released by Asch Records. It highlights Williams solo and in tandem with bassist Al Lucas and drummer Jack Parker.

However, the work only really unfolded when Milt Orient helped arrange it for chamber and symphony orchestra. The extended work could be heard in Town Hall on December 31, 1945, and June 1946, it could be heard in Carnegie Hall.

Today, the work also lives on. In 2006 it was re-recorded by pianist Geri Allen on the record Zodiac Suite: Revisited and in 2021 the New York Philharmonic recorded the music. The two approaches capture the range of the interpretative possibilities of the work from the nuanced and diverse minimalism that Williams herself cultivated in the original recording with Lucas and Parker to the orchestral expression that Orient helped to realize.

It is characteristic of Mary Lou Williams that The Zodiac Suite is dedicated to musicians. Throughout her life she was an active supporter of musicians, both known and unknown. In a biography of Thelonious Monk, Straight, No Chaser: The Life And Genius Of Thelonious Monk (Schirmer Books, 1997), Leslie Gourse has described the special environment that surrounded her apartment at 63 Hamilton Terrace. Here, personalities like Erroll Garner, Phineas Newborn and Art Tatum came to play and talk, while bright talents like Bud Powell, Elmo Hope and Monk were taken under William's wing. She could also be harsh, pointing out that they lacked something in their touch and then took it upon herself to improve it.

When Monk was in Paris in 1954 where she herself lived at the time, Williams again came to play an important role. After a concert in the Salle Pleyel, she introduced Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, who became an important acquaintance for Monk. Musically speaking, Bob Blumenthal has noted the influence of Williams' composition "Walkin' and Swingin'" on Monk's "Rhythm-a-ning."

Crisis and Religious Redemption

She also became involved in festival work in her hometown where she played a crucial role in the development of the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival, the first edition of which came in 1964. However, she still focused on helping her fellow human beings. In 1957 she started The Bel Canto Foundation whose purpose was to help musicians in need. The work was financed through her own thrift store and the income from the record label she started, Mary Records.

The Zone and History of Jazz

Zoning the History of Jazz became the title of the book she was working on. The concept of zoning covers a philosophy that is about creating space for the music. On the record of the same name, released on Mary Records in 1974, she is completely in the musical zone, conveying a funky modernism that is as tight and resilient in its rhythmic expression as it is open and probing. It is a different realization of the history of jazz than a record like A Keyboard History (Jazztone, 1955) , but then again not. With Williams, who mastered the entire jazz repertoire from its roots in gospel and spirituals to post-bop, understanding the history of jazz is the prerequisite for emotional liberation. The intellectual and the emotional are connected. One must know the body of jazz to express its soul. The history of jazz is present in her choice of repertoire where she often played jazz classics. As she pointed out at a concert that can be heard in excerpts in Joanne Burke's documentary: Mary Lou Williams: Music on My Mind (1990):

"There have been four important periods in this wonderful music: spirituals, ragtime, Kansas City swing, and the bop era. All the music is healing and spiritual."

These four periods form the cornerstones of Williams' style, which can otherwise be difficult to define and distinguish. On a record like Zoning, which is dominated by her own compositions, jazz history is present as archaeological layers, the colors of which subtly help to shape the musical painting. She could unite the styles of jazz in an expression that ranges from the funky blues "Play It Momma" to the modernist dissonance in a composition like "Zoning Fungus II" where she can be heard in a duet with the pianist Zita Carno.

The duet or dialogue is the key to understanding Williams' music. She is constantly in dialogue with the music, the musicians, and the tradition, which is of course is handed down orally. She did not believe that jazz could be learned by playing from a book, and in Burke's documentary there are some wonderful passages where she sings the music with her students.

Recording for SteepleChase

"I was in New York and everyone was talking about how great it was that this "old lady" played with Buster Williams and Mickey Roker. I heard them at a restaurant on Bleeker Street and then contacted Father Peter who took care of all her business, both earthly and heavenly."

Winther still remembers the meeting with Williams:

"She was an unusually kind and serious person. She was very religious. I naturally knew about her long career, but also had recordings with young musicians who "took lessons" with her, e.g. Hilton Ruiz, John Stubblefield, etc."

Her dedicated approach to music was clearly expressed when the album had to be recorded:

"She was very serious. She recorded many takes before she was satisfied: "Pale Blue"—9 takes, "Temptation"—7 takes, "Baby Man"—4 takes, "Gloria"—6 takes, "Surrey With The Fringe On Top"—4 takes, "Free Spirits & Ode To Saint Cecilia"—3 takes, "Dat Dere," "All Blues" and "Blues For Timme"—2 takes. The musicians were the ones she worked with and the choice of tunes was largely hers, with a few suggestions from me. Mary Lou was happy with the artistic freedom she got on the recording. I left the choice of repertoire and choice of musicians up to her, as I think it should always be, by the way."

The finished record, Free Spirits, has since been highlighted as one of her best recordings by the Penguin Guide to Jazz. Winther is not much for proclaiming classics, but nevertheless states:

The legacy of Mary Lou Williams

Williams continued to teach and record after Free Spirits, including the aforementioned record with Cecil Taylor, but age and illness gradually weakened her and on May 28, 1981, it was over. Mary Lou Williams died aged 71, leaving behind an extensive and varied discography, and not least a rich musical legacy. In Denmark, her music has been taken up by the composer and pianist Jacob Anderskov. He gets the closing words with his testimonial for a musician for whom conveying the joyful message of jazz music and supporting other musicians was paramount:"My first encounter with Mary Lou William's music was on the iconic, but also for her atypical, record with her and Cecil Taylor together. I later read that she was frustrated with this collaboration, and the record is perhaps not the best place to start for several reasons. On the other hand, it is a unique documentation of an extremely interesting frontal clash between two great musicians, each from a different aesthetic, and each from a different generation."

"Mary Lou William's close connection to many of bebop's great celebrities is often mentioned, perhaps without it ever becomes clear how much Mary Lou Williams influenced the young beboppers. I'm certainly not an expert in this discussion, but on the other hand, it's hard not to be curious about what she showed to whom, and when, when you hear her music. Lately, I have been particularly interested in the album Zodiac Suite. Compositions such as "Virgo," "Pisces," "Scorpio," "Capricorn" and "Taurus" sound extremely precisely articulated, and if they were subjected to a modern remastering, one could well be mistaken and think that it was much newer music than is the case. Who has the original tapes, I hereby ask. On "Virgo" in particular, it is also as if a very direct dialogue is heard with Thelonious Monk's music, where we will probably never find out which way the influence flowed."

"I myself have played her "In the Land of Oo-bla-dee" with great pleasure, of which it is recommended to hear her own arrangement, recorded by Dizzy Gillespie's band featuring Joe Carroll on vocals. It is a rather humorous track in the original recording, both entertaining and almost meta-bop, understood in the way that the tonal language of bebop, combined with the silly text, actually breaks down the usual perspectives of bebop. But apart from that, the track is purely instrumentally wonderful to play, and to play over. And of course, listen to the ever-fresh version she's done of "It aint necessarily so"—has that track ever been played more hip?"