SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2021

VOLUME TEN NUMBER THREE

DONALD HARRISON

(October 2-8)

CHICO FREEMAN

(October 9-15)

BEN WILLIAMS

(October 16-22)

MISSY ELLIOTT

(October 23-29)

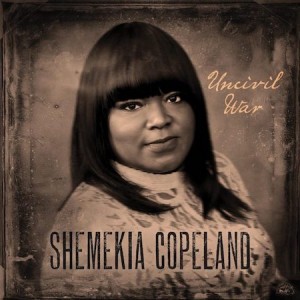

SHEMEKIA COPELAND

(October 30-November 5)

VON FREEMAN

(November 6-12)

DAVID BAKER

(November 13-19)

RUTHIE FOSTER

(November 20-26)

VICTORIA SPIVEY

(November 27-December 3)

ANTONIO HART

(December 4-10)

GEORGE ‘HARMONICA’ SMITH

(December 11-17)

JAMISON ROSS

(December 18-24)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/shemekia-copeland-mn0000026803/biography

Shemekia Copeland

(b. April 10, 1979)

Artist Biography by Steve Huey

Projecting a maturity beyond her years, blues singer Shemekia Copeland began making a splash in her own right before she was even out of her teens. Copeland fashioned herself as a powerful, soul-inflected shouter in the tradition of Koko Taylor and Etta James, yet also proved capable of a subtler range of emotions. Her 1998 Alligator debut, Turn the Heat Up!, featured a career-elevating version of "Ghetto Child," a classic by her father, renowned Texas blues guitarist Johnny Copeland, that has been part of her performance repertoire ever since. She released three more acclaimed rough-and-rowdy recordings that decade before revealing a more nuanced, slow-burning persona on Never Going Back in 2009. Over her next two albums, 2012's 33 1/3 and 2015's Outskirts of Love, she became not only a formidable singer but an influential stylist. By the time of 2018's America's Child, she had transformed herself into an artist who could inhabit virtually any genre of music without sacrificing the power and passion that initially established her reputation.

Copeland was born in Harlem in 1979, and her father encouraged her to sing from the start, even bringing her up on-stage at the Cotton Club when she was just eight. She began to pursue a singing career in earnest at age 16, when her father's health began to decline due to heart disease; he took Shemekia on tour with him as his opening act, which helped establish her name on the blues circuit. She landed a record deal with Alligator, which issued her debut album, Turn the Heat Up!, in 1998 when she was just 19 (sadly, her father didn't live to see the occasion).

While the influences on Copeland's style were crystal clear, the record was met with enthusiastic reviews praising its energy and passion. Marked as a hot young newcomer to watch, she toured the blues festival circuit in America and Europe, and landed a fair amount of publicity. Her second album, Wicked, was released in 2000 and featured a duet with one of her heroes, early R&B diva Ruth Brown. Wicked earned Copeland a slew of W.C. Handy Blues Award nominations and she walked off with three: Song of the Year, Blues Album of the Year, and Contemporary Female Artist of the Year. The follow-up record, Talking to Strangers, was produced by legendary pianist Dr. John and featured songs that she proudly claimed were her best yet. The Soul Truth, produced by Steve Cropper, was issued by Alligator Records in 2005. Never Going Back followed in 2009 from Telarc Blues and was produced by the Wood Brothers' Oliver Wood. 33 1/3 appeared in 2012 and was again produced by Wood and issued by Telarc.

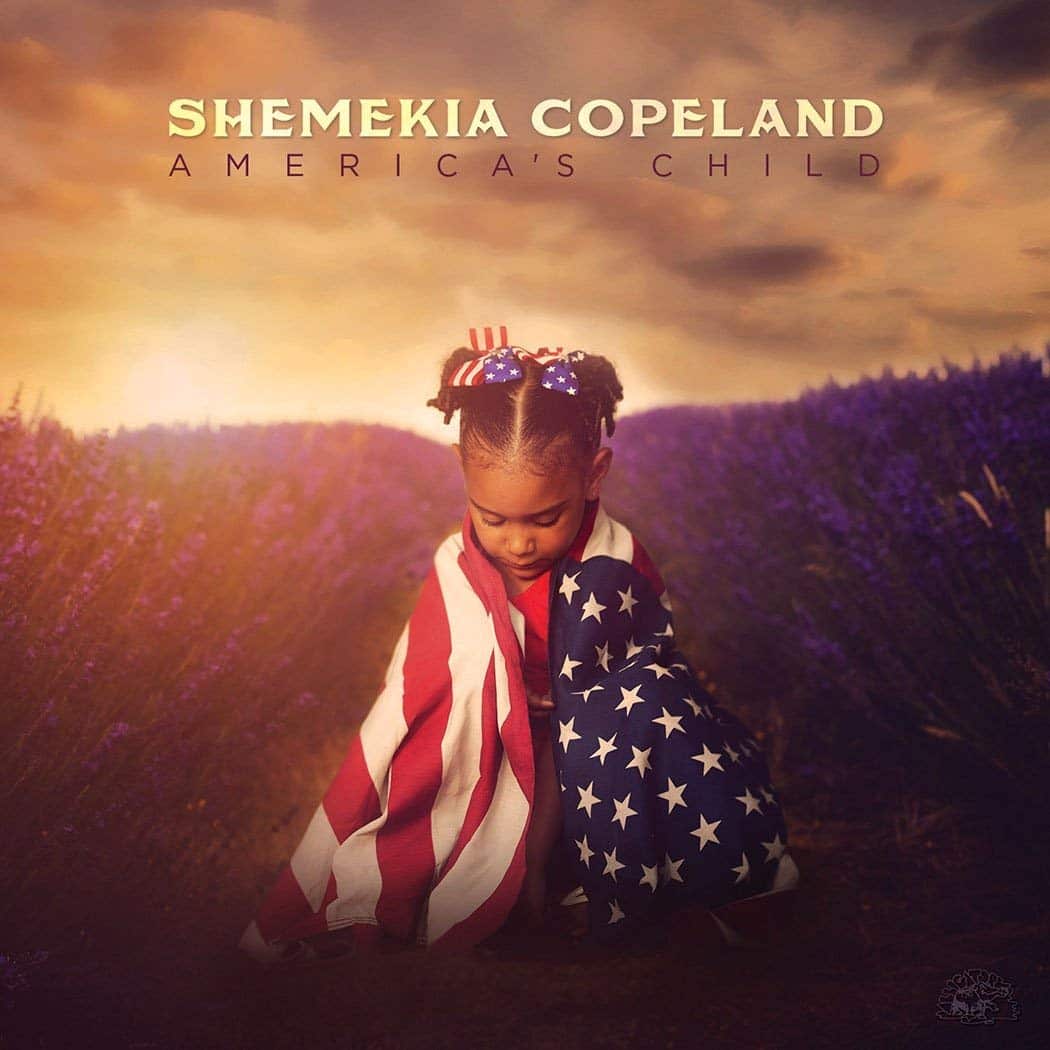

Copeland returned to Alligator for the release of 2015's Outskirts of Love, which featured guest appearances from Robert Randolph, Alvin Youngblood Hart, and Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top. The album was nominated for a Grammy in the Best Blues Album category. In 2017, Copeland gave birth to a son and, deeply inspired by the experience, she shifted direction. She chose to record in Nashville and enlisted producer/guitarist Will Kimbrough -- who in turn enlisted guests who included John Prine, Mary Gauthier, Emmylou Harris, Steve Cropper, and more. With guidance from Kimbrough, Copeland dug deep and completed a resonant program of soul, Americana, blues, and country with 2018's America's Child. Kimbrough returned as producer for 2020's Uncivil War, 12 songs that mixed political and social commentary with more personal themes; guest artists included Jason Isbell, Steve Cropper, and Duane Eddy.

https://www.shemekiacopeland.com/biography

BIO

“Shemekia Copeland is a powerhouse, a superstar…She can do no wrong” –Rolling Stone

“Shemekia Copeland’s voice is rich, soulful and totally commanding…authoritative, passionate and raw” –MOJO

“Copeland provides a soundtrack for contemporary America…powerful, ferocious, clear-eyed and hopeful…She’s in such control of her voice that she can scream at injustices before she soothes with loving hope. It sends shivers up your spine.” –Living Blues

With a recording career that began in 1998 at age 18, award-winning vocalist Shemekia Copeland has grown to become one of the most talented and passionately candid artists on today’s roots music scene. Her riveting new album, Uncivil War, builds on the musically and lyrically adventurous territory she’s been exploring for over a decade, blending blues, R&B and Americana into a sound that is now hers alone. The soulful and uncompromising Uncivil War tackles the problems of contemporary American life head on, with nuance, understanding, and a demand for change. It also brings Copeland’s fiercely independent, sultry R&B fire to songs more personal than political. NPR Music calls Shemekia “authoritative” and “confrontational” with “punchy defiance and potent conviction. It’s hard to imagine anyone staking a more convincing claim to the territory she’s staked out—a true hybrid of simmering, real-talking spirit and emphatic, folkie- and soul-style statement-making.”

Uncivil War—recorded in Nashville with award-winning producer and musician Will Kimbrough at the helm—is a career-defining album for three-time Grammy nominee Copeland. With songs addressing gun violence (Apple Pie And A .45), civil rights (the Staple Singers-esque message song, Walk Until I Ride), lost friends (the Dr. John tribute Dirty Saint), bad love (Junior Parker’s In The Dark) as well as good (Love Song, by her father, legendary bluesman Johnny Clyde Copeland), Uncivil War is far-reaching, soul-searching and timeless. Guests on Uncivil War include Americana superstar Jason Isbell, legendary guitarist Steve Cropper, rising guitar star Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, rocker Webb Wilder, rock icon Duane Eddy, mandolin wizard Sam Bush, dobro master Jerry Douglas, and The Orphan Brigade providing background vocals.

Among the most striking songs on Uncivil War is the true, torn-from-history story, Clotilda’s On Fire. It tells of the very last slave ship to arrive in America (in Mobile Bay, Alabama) in 1859, 50 years after the slave trade was banned. The ship—burned and sunk by the captain to destroy the evidence—was finally discovered in 2019. The song—featuring Alabama native Jason Isbell playing the most ferocious blues guitar of his career—is a hair-raising look at living American history delivered with power, tenderness, and jaw-dropping intensity.

Another stand-out song is the topical title track, a courageous plea for unity in a time of disunion. The song is simultaneously challenging and comforting, as Shemekia delivers Uncivil War with passion and insight about the chaos and uncertainty in the world while still finding light in the darkness and hope for the future. Rolling Stone praised it as, “Blues queen Shemekia Copeland’s rootsy message song about the divided states of America. Her gospel-tinged vocal is there to soothe and defuse, reminding us that it’s time to listen to one another and, ultimately, come together.”

When Shemekia first broke on the scene with her groundbreaking Alligator Records debut CD Turn The Heat Up, she instantly became a blues and R&B force to be reckoned with. News outlets from The New York Times to CNN praised Copeland’s talent, larger-than-life personality, dynamic, authoritative voice and true star power. With each subsequent release, Copeland’s music had evolved. From her debut through 2005’s The Soul Truth, Shemekia earned eight Blues Music Awards, a host of Living Blues Awards (including the prestigious 2010 Blues Artist Of The Year) and more accolades from fans, critics and fellow musicians. 2000’s Wicked received a Grammy nomination. Two successful releases on Telarc (including 2012’s Grammy-nominated 33 1/3) sealed her reputation as a fearless and soulful singer.

When Copeland returned to Alligator Records in 2015 with the Grammy-nominated, Blues Music Award-winning Outskirts Of Love, she continued to broaden her musical vision, melding blues with more rootsy, Americana sounds. With her soaked-in-blues vocals at the forefront, she extended her lyrical reach, singing substantial new material and reinventing songs previously recorded by artists including ZZ Top and Creedence Clearwater Revival. NPR’s All Things Considered said, “Copeland embodies the blues with her powerful vocal chops and fearless look at social issues.” No Depression declared, “Copeland pierces your soul. This is how you do it, and nobody does it better than Shemekia Copeland.”

With 2018’s America’s Child, Copeland continued singing about the world around her, shining light in dark places with confidence and well-timed humor. Singer/songwriter Mary Gauthier, who contributed two songs to the album, said, “Shemekia is one of the great singers of our time. Her voice is nothing short of magic.” Potent new songs, a duet with John Prine, and a reinvention of a Kinks classic led MOJO magazine to name America’s Child the #1 blues release of 2018. It won both the Blues Music Award and the Living Blues Award for Album Of The Year. American Songwriter said, “Copeland delivers the meticulously chosen material with fierce intent, balancing her emotionally moving, searing, husky, four-alarm vocals with a more subtle tough yet tender approach. The riveting America’s Child pushes boundaries, creating music reflecting a larger, wider-ranging tract of Americana.”

Shemekia Copeland has performed thousands of gigs at clubs, festivals and concert halls all over the world, and has appeared in films, on national television, NPR, and in magazine and newspapers. She’s sung with Eric Clapton, Bonnie Raitt, Keith Richards, Carlos Santana, Dr. John, James Cotton and many others. She opened for The Rolling Stones and entertained U.S. troops in Iraq and Kuwait. Jeff Beck calls her “amazing.” Santana says, “She’s incandescent…a diamond.” In 2012, she performed with B.B. King, Mick Jagger, Buddy Guy, Trombone Shorty, Gary Clark, Jr. and others at the White House for President and Mrs. Obama. She has performed on PBS’s Austin City Limits and was recently the subject of a six-minute feature on the PBS News Hour. Currently, Copeland can be heard hosting her own popular daily blues radio show on SiriusXM’s Bluesville.

With Uncivil War, Copeland is determined to stand her ground, help heal America’s wounds and continue to mend broken hearts. She brings people together with her music, a spirited amalgamation of blues, roots and Americana. She’s anxious to bring her new songs to her fans around the world as soon as possible. Of the new album Copeland says, “I’m trying to put the ‘united’ back in the United States. Like many people, I miss the days when we treated each other better. For me, this country’s all about people with differences coming together to be part of something we all love. That’s what really makes America beautiful.”

The Chicago Tribune’s famed jazz critic Howard Reich says, “Shemekia Copeland is the greatest female blues vocalist working today. She pushes the genre forward, confronting racism, hate, xenophobia and other perils of our time. Regardless of subject matter, though, there’s no mistaking the majesty of Copeland’s instrument, nor the ferocity of her delivery. In effect, Copeland reaffirms the relevance of the blues.” The Philadelphia Inquirer succinctly states, “Shemekia Copeland is an antidote to artifice. She is a commanding presence, a powerhouse vocalist delivering the truth.”

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/shemekia-copeland

Shemekia Copeland

Shemekia Copeland - Blues Singer

When singing sensation Shemekia Copeland first appeared on the scene in 1997 with her groundbreaking debut CD, “Turn The Heat Up,” she quickly became, at 18 years old, a roots music superstar. Critics from around the country celebrated Shemekia's music as fans of all ages agreed that an unstoppable new talent had arrived. Shemekia released two more CDs: 2000's Grammy nominated “Wicked,” and 2002's Talking To Strangers,” (produced by Dr. John), and in that short period of time, collected five Blues Music Awards, a Grammy nomination, five Living Blues Awards, and was honored with the coveted “Talent Deserving Wider Recognition” Award by the DownBeat Critics' Poll. Shemekia has already had a lifetime's worth of career highlights, including performances on national television, appearances in films, and sharing stages with some of the biggest names in the music world. And now she can add the title 'radio host' to her already impressive list of accomplishments. Copeland will host her own weekly blues radio program, Shemekia Copeland's Blues Show, exclusively on Sirius satellite radio.

Her 2005 CD, aptly titled,”The Soul Truth,” is the funkiest, deepest, and most exciting statement yet. Produced by renowned Stax guitarist Steve Cropper (who also adds his stellar guitar playing to the CD), the album is steeped in the spirit of classic Memphis soul but, at the same time, is a contemporary and up-to-the-minute slice of life. Featuring Shemekia's powerful, emotional vocals over a blistering band with horns punching in all the right places, “The Soul Truth” is a tour-de-force of rock, soul and blues.

Born in Harlem, New York in 1979, Shemekia came to her singing career slowly. “I never knew I wanted to sing until I got older,” says Copeland. “But my dad knew ever since I was a baby. He just knew I was gonna be a singer.” Her father, the late Texas blues guitar legend Johnny Clyde Copeland, recognized his daughter's talent early on. He always encouraged her to sing at home and even brought her on stage to sing at Harlem's famed Cotton Club when she was just eight. At that time Shemekia's embarrassment outweighed her desire to sing. But when she was 15 and her father's health began to slow him down, she received the calling. “It was like a switch went off in my head,” recalls Shemekia, “and I wanted to sing. It became a want and a need. I had to do it.”

Shemekia's passion for singing, matched with her huge, blast-furnace voice, gives her music the timeless power and heart-pounding urgency of a very few greats who have come before her. The media has compared her to a young Etta James, Koko Taylor, Aretha Franklin and Ruth Brown, but Shemekia - who was raised in the tough, urban streets of Harlem - has her own story to tell. Although schooled in Texas blues by her father, Shemekia's music comes from deep within her soul and from the streets she grew up on, where a daily dose of city sounds - from street performers to gospel singers to blasting radios to bands in local parks - surrounded her.

With all this experience under her belt, 16-year-old Shemekia joined her father on his tours after he was diagnosed with a heart condition. Soon enough Shemekia was opening, and sometimes even stealing, her father's shows. “She grabbed the crowd with her powerful voice, poised and intense,” raved Blues Revue at the time. Eventually, though, it became clear to Shemekia who was helping whom. “Dad wanted me to think I was helping him out by opening his shows when he was sick, but really, he was doing it all for me. He would go out and do gigs so I would get known. He went out of his way to get me that exposure,” recalls Shemekia. Shemekia stepped out of her father's shadow in 1998 when Alligator released “Turn The Heat UP,” to massive popular and critical acclaim. Rave reviews ran everywhere from Billboard to The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, The Chicago Sun-Times, The Boston Globe, Emerge and many others. “Nothing short of uncanny,” said The Village Voice. “She roars with a sizzling hot intensity,” shouted The Boston Globe. She appeared in the motion picture Three To Tango, and her song I Always Get My Man was featured in another Hollywood film, Broken Hearts Club.

In 2000 she returned with “Wicked.” Almost immediately the young singer was in great demand at radio, television and in the press. The opening song, It's 2:00 A.M., won the Blues Music Award for Song Of The Year, and the album was nominated for a Grammy Award. She appeared twice on Late Night With Conan O'Brien, and also performed on National Public Radio's Weekend Edition and the CBS Saturday Early Show. In November 2001, she appeared on Austin City Limits to an enthusiastic live audience and on television to millions more old and new fans all across the country.

With her 2002 Dr. John-produced follow-up, “Talking To Strangers,” Shemekia again turned up the heat, with far-reaching material treading the ground where blues and soul meet rock and roll. The album debuted in the #1 spot on the Billboard Blues Chart and received critical praise all around the world. Features and reviews ran in The Washington Post, Billboard, Essence, Vibe, USA Today, DownBeat, Ebony and many other national and regional publications. She appeared on the Late Show With David Letterman (along with B.B. King), was featured in the Martin Scorsese-produced concert film Lightning In A Bottle, the PBS television series The Blues and even opened a show for the Rolling Stones in Chicago.

Shemekia continues to tour the world and to win fans at every stop. She's played with Buddy Guy and B.B. King, and has shared the stage with Taj Mahal, Dr. John and Koko Taylor, among many others. She won the hearts and souls of new fans at the 1998 and 2002 Chicago Blues Festivals, The North Atlantic Blues Festival, Milwaukee's Summerfest, The Monterey Jazz Festival, The San Francisco Blues Festival, The New York State Blues Festival, The North Sea Festival in Holland, The Montreux Jazz Festival, The New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, The Lowell Folk Festival, and many others.

One of the many lessons Shemekia learned growing up was the importance of singing from the heart. “Nobody wants to listen to someone singing just to earn some money,” she says. “You've gotta sing because you need to do it.” Indeed, Shemekia's soul-satisfying vocals and the lessons she learned from her father, matched with her inner need to sing, have brought her to audiences both young and old. “I still listen to Aretha Franklin, Katie Webster, Trudy Lynn, Etta James, Howard Tate, India Arie and Angelique Kidjo. But I never try to copy them. They've all inspired me and helped me become my own person.”

https://downbeat.com/reviews/detail/uncivil-war

Anyone who has paid attention to the blues scene of the past 20 years is fully aware that singer Shemekia Copeland can belt with gusto. Known more for her vocal gifts than her compositional skills, the key element that distinguishes Copeland’s good albums from her great ones is the quality of the songs she chooses. Her artistry has reached a new level with Uncivil War, thanks to Will Kimbrough, who produced the album, plays electric guitar throughout the program, and co-wrote seven of the 12 tracks.

The album opens with four remarkable, substantive Kimbrough tunes, making it clear that Copeland is not content to merely sing blues fodder about love gone wrong: “Clotilda’s On Fire” chronicles the horrors—and lasting impact—of slavery; “Walk Until I Ride” is a contemporary civil rights manifesto fueled by messages reminiscent of songs by the Staples Singers; the title track is a plea for unity during our divisive times; and “Money Makes You Ugly” is a protest song for environmentalists.

Toward the end of the album, there is a cluster of three songs that are just as weighty as those that open the disc: “Apple Pie And A .45” decries rampant gun violence; “Give God The Blues” is an existential exploration of similarities shared by several organized religions; and “She Don’t Wear Pink” is an LGBTQ anthem.

Copeland’s recordings often incorporate sonic elements from the Americana world, as evidenced here by bluegrass star Sam Bush’s mandolin textures on the title track, as well as Jerry Douglas’ exceptional work on lap steel guitar and Dobro on three tunes. Electric guitarists making guest appearances on the album include blues dynamo Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, Stax icon Steve Cropper and rock ’n’ roll pioneer Duane Eddy.

Not every track on the album is a slice of social commentary; “Dirty Saint” adds a jolt of New Orleans funk to the proceedings. Penned by Kimbrough and John Hahn, the song is a fitting tribute to Dr. John, who produced Copeland’s 2002 disc, Talking To Strangers. The program closes with another type of tribute, as the singer acknowledges her familial and artistic roots by interpreting “Love Song.” It’s a sturdy composition by her father, Johnny Copeland, who was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2017, two decades after his death. Just as Johnny did, Shemekia Copeland’s work has expanded the audience for the blues.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shemekia_Copeland

Shemekia Copeland

On 'Uncivil War,' Shemekia Copeland Sets Fire To A Relic Of American Slavery

Blues singer Shemekia Copeland uses her new album, Uncivil War, to tell the story of the Clotilda — what's thought to be the last slave ship to smuggle African captives to American shores.

On her new album, Uncivil War, blues singer Shemekia Copeland tells the story of what's thought to be the last slave ship to smuggle African captives to American shores, the Clotilda. On the centerpiece track, she sings:

She's coming for you, hear the chains rattle,

Turn you into a slave, another piece of chattel

The burned-out shipwreck of the Clotilda was discovered last year deep in an Alabama river, bringing new attention to the history. Now, Copeland's song "Clotilda's on Fire" explores the legacy of that voyage.

More than 50 years after the slave trade was outlawed in the U.S., plantation owner Timothy Meaher hired a ship captain to smuggle 110 kidnapped West Africans to Alabama. Copeland says this song is about embracing a part of American history that a lot of people would like to forget.

"History is not always pretty," she says. "But first, you must accept it and then you have to change it."

When the Clotilda returned, its captives were hidden in the swamps near Mobile Bay, and the wooden schooner was scuttled upriver and set afire to hide any evidence. No one was ever held to account.

"Slavery is something that we've been talking about culturally for a long time, and I've had many discussions about it," Copeland says. "But what gives me goose pimples, chicken skin, is the lyric, 'We're still living with her ghost.' " She says her goal was to draw attention to the Clotilda story — "let people know about what happened, what they did, what they tried to hide. And let them know that we're still dealing with this and we really shouldn't be in 2020."

The lyrics were written by her longtime manager and songwriter John Hahn, who first worked with her father, the late Texas bluesman Johnny Clyde Copeland.

"I'm so grateful. I tell you what, God always sets me up with who I need to be with," she says. "I've known John Hahn since I was 8 years old, and I'm completely convinced that he's just a reincarnation of an old black woman who had a whole lot to say and never got a chance to say it."

"Clotilda's on Fire" was set to music by Will Kimbrough, who produced the album. He describes the song as straightforward and driving, but notes that it avoids a traditional blues chord progression.

"Even though this is really a blues record, it needed to rock," Kimbrough says. "I didn't want it to sound happy go lucky, but I didn't want it to sound sad. I wanted it to have power."

Since the Clotilda's shipwreck was discovered in the Mobile River last year, there's been a new focus on the community formed by its former captives. After emancipation, they worked to buy land and build a town — known as Africatown — on the outskirts of Mobile. They preserved African traditions, raised their families, started a school,and established a cemetery that faces east towards their homeland.

But Africatown has been in decline in recent decades. People and businesses have left. It's hemmed in by a paper mill, chemical plants,and oil storage tanks. The Clotilda Descendants Association is trying to revitalize the area and develop a museum to house artifacts and tell the story of the Clotilda.

Kimbrough, who is from Mobile, says he wanted "Clotilda's on Fire" to take their story beyond local folklore. "It's a powerful story," he says. "I like that it is an angry song about injustice, but a celebration of the how resilient people can be."

Kimbrough plays guitar on the record, and he recruited another Alabamian to play a solo – alt country star Jason Isbell.

"It's smoking guitar," Kimbrough says. "I love that we have the queen of the blues singing about the last slave ship bringing African people to be enslaved in America, with two Alabama boys playing behind her."

Isbell, for his part, welcomed the gig. "There's a duality for me when it comes to playing blues music, because the music itself carries so much weight and I have so much fun playing it," the artist says. "That, to me is kind of the apex of what popular music can do."

Isbell says the song is coming at the right time, as the nation confronts the very meaning of social justice.

"I think we're going to have to figure out how to all get on the same page, because some people still deny the fact that systemic racism exists and that's beyond me," says Isbell. "I don't understand how you can look around and deny that we're still feeling the effects of slavery."

The title track on Uncivil War also speaks to today's climate, and is Copeland's way of confronting what she describes as the ugliness that she's seen flourish in American society. "How long must we fight this uncivil war?" she sings. "The same old wounds we opened before / Nobody wins an uncivil war."

Shemekia Copeland - Uncivil War

"You know, being angry doesn't do us any justice," Copeland says. "I spent my time being angry and pissed off and mad about it. But at the end of the day, you know, that just doesn't help anything."

Copeland says her goal is to help bring people together, and "remind us who we are." She clings to the hope that America can do better.

"That is what this album is all about," she says. "How long must we fight?"

This story was produced for broadcast and adapted for the Web by Tom Cole.

https://americansongwriter.com/shemekia-copeland-american-child/

Shemekia Copeland

America’s Child

(Alligator)

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars

“Does the world make you think everything’s coming unwound? … When the whole world seems fake, give me something real,” demands soul/blues singer Shemekia Copeland on her most politically tinged effort yet.

On her eighth album, the fiery veteran singer, and daughter of famed bluesman Johnny Copeland, is mad as hell and not going to take it anymore. That’s clear in America’s Child’s tough, firm and unapologetically inclusive stance. Copeland has never been shy about putting her beliefs into songs, predominantly written by others but clearly representative of her views. From this album’s title and cover photo of a child draped in the American flag to tracks like “Americans” (New Orleans second-line funk, co-penned by Mary Gauthier, laundry listing the wide swath of people in the US with “no two are the same, I hope we never change”) and the swamp blues of “Great Rain,” co-composed by John Prine who also duets, Copeland pushes her blues confines while staying tethered to them. Will Kimbrough takes over production from Oliver Wood who worked on previous Copeland discs. He brings in Prine, Emmylou Harris, pedal steel master Al Perkins, J.D. Wilkes, Steve Cropper, and others to assist.

From the opening propulsive blues-rocking “Ain’t Got Time for Hate” to a somewhat surprising, creatively rearranged cover of The Kinks’ “I’m Not Like Everybody Else,” where Copeland refashions the UK ’60s classic as a slow-burn gospel (“Once I get started, I go to town”), Copeland asserts her individuality, both in her searing, husky, soulful vocals and philosophical viewpoints. There’s still room for tough yet tender romance in the driving greasy slide guitar Southern blues-rock cover of Kevin Gordon’s “One I Love,” and a sweet testimonial to the promise of finding true love after multiple failed attempts in her version of her dad’s “Promised Myself,” the disc’s most emotionally moving moment.

Rhiannon Giddens and her banjo take us backwoods for a folksy “Smoked Ham and Peaches” that uses the titular honest meal as a means to escape from phony politics (“how many cards can they keep up their sleeves?”). And things get really scary as Copeland torches her home because she’s been cheated on in the slow sizzle of the cautionary “Such a Pretty Flame” (“nothing burns hotter than your own regrets”).

Even though Copeland doesn’t get songwriting credit, she has meticulously chosen material — much of it co-composed by longtime manager John Hahn — that reflects her views, both political and personal. Most importantly, she delivers these tunes with fierce intent, balancing her four alarm vocals with a more subtle approach.

Shemekia Copeland might have been born into the blues, but the riveting America’s Child shows her continuing to push those boundaries, creating music reflecting a larger, wider-ranging tract of Americana.

https://www.duluthnewstribune.com/lifestyle/3910328-shemekia-copeland-wants-tell-you-story

On just about every song from her 1998 debut,

“Turn the Heat Up,” Shemekia Copeland sounds like she can’t wait to get

to the chorus so she can show off her blues-belting power. But she

doesn’t sing like that anymore.

Today, Copeland sounds like she

wants to tell you a story. “When I was younger, gosh, I didn’t know what

the hell I was doing. I didn’t have any training, or anything, I just

started singing,” says the Chicago-based singer, 36, by phone from New

Orleans. “I love aging. It’s a wonderful thing. And the best part of it

is using the subtleties of my voice. Just being comfortable in my own

skin.

“People (would) say, ‘My gosh, you’re a great singer,’ and

it would freak me out. ‘No, I’m not, this person’s a great singer’ - and

I could point out 1,000 singers who are great, and I’m not” she

continues. “That’s because I couldn’t appreciate myself, and now I can,

because I’m me. When I hear my voice, it’s like, you know, it’s me.

That’s it.”

Over seven albums in 17 years, mostly on Chicago’s

Alligator Records, Copeland took vocal lessons and worked on nuances

with producer and songwriter Oliver Wood. Throughout this year’s

Grammy-nominated “Outskirts of Love,” Copeland makes like her touring

partner, bluesman Robert Cray, and spins clear-voiced tales of the down

and out. In the title track, co-written by Wood and manager John Hahn,

she sings: “Carrying a suitcase / all bound up with string / it was all

that she had left since she pawned her wedding ring.” Of course,

Copeland is not opposed to power belting - she just doesn’t have to do

it all the time.

“I never thought I had a pretty voice, you know

what I mean?” Copeland asks. “I thought I had to belt things out. I was a

blues singer - that’s what I did. I didn’t think the subtlety of what I

did was a good thing.”

With the help of Hahn and Wood, Copeland

unveiled this more reflective singing style around 2009, with “Never

Going Back to Memphis,” a torchy film-noir song about a criminal’s

framed ex-girlfriend who replays Junior Parker in her head while cops

eat fried chicken. It was a short step from there to political music,

particularly 2012’s “Ain’t Gonna be Your Tattoo,” a more straightforward

ballad about domestic violence. Women began to approach Copeland and

tell her about refusing to return to their abusive husbands and

boyfriends after listening to these types of songs. “I was like, ‘Holy

(cow).’ It affected me in such a big way,” Copeland says. “I said I

wanted to do more songs like this.”

Copeland’s latest album, this

year’s “Outskirts of Love,” is her first cycle of songs dealing

exclusively with the downtrodden - homeless people in “Cardboard Box” a

date-rape victim in “Crossbone Beach,” a brush with sexual harassment in

“Drivin’ Out of Nashville” and, more in line with blues conventions,

the cheater in “I Feel a Sin Coming On” and the sad souls in Jessie Mae

Hemphill’s “Lord, Help the Poor and Needy.”

“We pretty much knew

this record was going to be about people who were on the outskirts of

something, whether it’s social injustice or homelessness or date rape,

whatever it was,” Copeland says. “It just pulled together so well,

surprisingly.”

Although Copeland is not a songwriter, she has

veto power over everything Hahn and Wood present to her. She has known

Hahn for almost 30 years, when he was managing her father, the late

Texas blues singer Johnny “Clyde” Copeland. (As the story goes, when

Copeland won a Grammy Award for 1985’s “Showdown!,” his collaboration

with fellow guitarists Cray and Albert Collins, Hahn couldn’t believe

Copeland hadn’t put out his own album, and wound up producing 1992’s

“Flyin’ High.”) “He just knows me really well - a father to me in so

many ways,” Shemekia Copeland says. “He’s very picky about (songs) he

gives me. I’m very picky about what I want performed. So if I can’t jump

inside of it and really become it and present it, I wouldn’t do it.”

Copeland adds that Hahn and Wood call her “The Face,” because “they know in my face whether or not it’s working.”

Born

in Harlem, Copeland first sang on stage as an 8-year-old, at the Cotton

Club with her father. (She has a vivid memory of him pulling up in a

car while she was walking to school, happily waving his “Showdown!”

Grammy out the window.) She began to sing professionally at 16,

befriending more established blues stars, taking in their advice. “Queen

of the Blues” Koko Taylor checked on her regularly, because, having

come up in an earlier era heavy with drugs and theft, “She was nervous

for me,” Copeland says.

“She always told me to look to the

hills,” she adds. “All the musicians I’ve talked to and hung out with -

they’re all very spiritual and very religious. (Chicago singer) Bobby

Rush got booty-shaking girls on stage, but every Sunday he’s in church.

And Buddy Guy’s in church. It’s a thing. I am also very spiritual. I’m a

believer in a higher power.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/22/arts/critics-choice-new-cds-the-soul-truth-shemekia-copeland.html

Critic's Choice: New CD's; The Soul Truth; Shemekia Copeland

Shemekia Copeland has no patience with the wrong kind of men on "The Soul Truth" (Alligator). She doesn't just leave them; she tells them exactly why she's going, what they did wrong and how much better she's going to feel when she's back on her own. Ms. Copeland is the 26- the great Stax Records studio band in the 1960's. He collaborated on some of the songwriting, and his guitar is at the center of arrangements with a lean backbeat, rollicking piano (by Chuck Leavell from the Allman Brothers Band and the Rolling Stones) and an ever-alert horn section. Unlike many soul-revival productions, the album supplies her with songs worthy of the treatment.

The melodies are chiseled and the lyrics are tough and funny: "Breakin' Out" compares divorce to a jailbreak, while in "All About You," which Ms. Copeland helped write, she realizes that "We're all through, because I could never love you as much as you do." Even when she's complaining about the state of the airwaves in "Who Stole My Radio?" -- "I want passion, I want feeling/ I want to be rocked from the floor to the ceiling" -- her terms are amorous and uncompromising. JON PARELES

The Queen’s Gamble

You could say that the songs on Shemekia Copeland’s new album, “Uncivil War,” include rocking shuffles, a showstopping slow blues and a New Orleans-style second-line groove, or that among the guest stars are the dobro maestro Jerry Douglas, the bluegrass mandolinist and fiddler Sam Bush, the alt-country rocker Jason Isbell, the twang icon Duane Eddy, the Stax Records soul mainstay Steve Cropper, and the blues guitar phenom Christone “Kingfish” Ingram. But when Copeland and her manager, John Hahn, conceived the album, they talked about an anti-gun-violence song, a song about the civil rights movement, an anti-racist song, a love-whomever-you-want song, a legacy-of-slavery song, a strong-woman song (or three), a song about economic inequality and the environment, a song about religious intolerance, a song about the vexed divides that split the nation into red and blue factions. They believe the cultural moment is ripe for explicitly political blues songs, reviving a form so old that it seems new again.

Widely hailed as the greatest blues singer of her generation and the reigning Queen of the Blues, Charon Shemekia Copeland, 41, has grown impatient with business as usual in the blues: the eclipse of singers by endlessly wailing guitars; the willingness of the aging boomers who dominate the core listenership to hear “Sweet Home Chicago” or “The Thrill Is Gone” yet again; set lists featuring the usual good-times anthems and romantic laments and not enough resonance with vital issues of the day. Her search for new audiences, collaborators and songs to sing is also a search for a fresh sense of relevance for the music she loves, and it has taken her from Chicago, the home of the blues, to Nashville, the capital of country music, with its matchless concentration of song-making talent.

There, she has sought not only musical but also ideological fellowship among artists who converge on the Americana scene, a progressive-tending confluence of country, folk, bluegrass and singer-songwriter rock created by roots-minded musicians in search of alternatives to the city’s mainstream country music industry, which traditionally caters to more conservative rural listeners. Being Queen of the Blues is no small distinction, but Copeland doesn’t believe it will be enough to sustain her in the long run. So she’s willing to risk a move away from her blues base to try to find a new home for her social concerns and her prodigious voice.

The first thing most listeners notice about Copeland’s voice is its sheer force. Frequently compared to great blues shouters of the 1920s like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, she’s in the habit of showing off the outsize instrument housed in her compact frame by stepping away from the mic and overmatching the amps of her band with her unaided voice. Such displays of raw power caught the blues world’s attention when she made her spectacular debut as a teenager, but it’s her mature control of that power that separates her from other belters. She used to come out blasting on every song, but now she gets more out of the quieter end of her dynamic range. Singers trying too hard to sound authentically bluesy often get sloppy with pitch and diction, smearing notes when they bend them and running lyrics through a blender of mannered imprecision — growling, slurring, droppin’ g’s — that reduces words to mush. Copeland, by contrast, sings like she’s explaining something. She bends notes with a microtonal precision that calls to mind the string-squeezing guitar genius Albert King, and her diction is as fussy as an opera singer’s. The words matter to her more than any other element of a song, and she wants to make sure you hear them all.

The guitar heroes who have dominated the blues since the rise of rock tend to treat songs as excuses to play solos, reducing them to a series of generic grooves: the jaunty shuffle, the stately slow blues. “Blues music has become very jam-band-ish, more about the jam than the song,” Copeland told me. “For me the words always come first when I’m picking a song to sing — ’cause I’m not a songwriter, I’m a song picker.” She has a routine for getting into a song someone else has written. “The lyrics have to say something I want to say, so I start there,” she told me. “Then I add a layer each time I listen: drums, bass, guitar.” Treating each song as a distinct piece of writing with mood, plot and point of view, she works hard to inhabit the character telling the story, so that listening to one of her sets feels a little like reading a collection of short stories or poems: the one about a freedom marcher in the rain (“Walk Until I Ride”), the one about a school shooter (“Apple Pie and a .45”), the one about a slave ship that sank off the coast of Alabama in 1860 (“Clotilda’s on Fire”).

“Shemekia’s one of the great singers of our music,” the veteran bluesman Taj Mahal told me. “I watched her grow, saw the torch passed to her from her father, and she has continued all along to honor that gift.” Johnny Clyde Copeland, Shemekia’s father, was a Texas bluesman, but his musical tutelage was eclectic. “My father wrote songs like a country artist, sang like a soul singer and played guitar like a bluesman,” she told me. “We listened to all kinds of music, and I sang Johnny Cash with him, and Hank Williams. One of the first songs I ever recorded was ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.’ ”

Her mention of those Mount Rushmore figures of country music shouldn’t come as a surprise. Though cultural convention pigeonholes the blues as an essential Black genre and country as the sound of Whiteness, the facts on the ground are messier than that.

Black Southerners, who invented the blues, no longer predominate among fans and practitioners. Copeland, who is Black, has performed with most of the great living Black blues figures and with others who are now gone, but many of her trusted musical collaborators are White. That group includes all but one member of her road band as well as John Hahn, who is not only her manager but also her principal lyricist; Will Kimbrough, the versatile Nashville ace who produced, played guitar and co-wrote seven songs on “Uncivil War”; and most of the Nashville pros Kimbrough and Hahn recruited to help write and play songs for her. In that sense, her musical community resembles her multiracial family — she and her husband, Brian Schultz, a heavy-metal-loving, White railroad construction supervisor from the Nebraska panhandle, have a 4-year-old son, Johnny — and the place where she has lived for the past 15 years: Beverly, one of the few racially integrated neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side.

Country, for its part, shares a root system with African American musical traditions. There has long been crossover traffic between country and blues, and country has always had significant numbers of Black listeners, musicians and influences. Copeland’s bluesman father, like many Southerners of his generation, grew up listening to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio, and she hears blues and country as mutually resonant elements of a single intertwined musical tradition with a strong Southern flavor. “If Patsy Cline isn’t a great blues singer,” she told me, “then I don’t know what a blues singer is.” As Copeland sings in “Drivin’ Out of Nashville,” a chicken-fried noir tale written by Hahn and Oliver Wood (another multiple-threat musical Swiss Army knife, a type in which Nashville specializes), “Country music ain’t nothin’ but the blues with a twang.”

So the blues-country team-up Copeland has been pursuing in Nashville in recent years — “Uncivil War” is her second album produced by Kimbrough — is more a revival of an old partnership than a new thing under the sun. The same goes for the merger of blues and explicitly political content. Copeland and Hahn often decry the dearth of social commentary in contemporary blues, but there’s precedent in the tradition for songs that directly address current political topics.

“There’s a way in which the conventional idea that there aren’t a lot of political songs in blues is right, and a way in which it’s wrong,” says the distinguished music historian Elijah Wald, who points out that even blues lyrics about heartbreak or hard labor have long been heard as responses to oppression. He argues that the habit of treating blues as roots music tends to sideline its political potential. “Robert Johnson singing about a railroad strike is not heard as protest music,” he told me. “It’s like the false distinction that treats ‘conscious’ rap as political and gangsta rap as not political.” He likens Copeland’s feminist-angled social commentary to that of the Chicks, the country supergroup shunned by country radio in 2003 (when they were known as the Dixie Chicks) for criticizing President George W. Bush. But the conventional classifying of popular genres allows country to be associated with current events and politics — often conservative and jingoistic — while blues is associated with abstract existential truths about the human soul.

Copeland’s turn toward Americana, an end run around these perceptions, raises echoes of the Popular Front, the leftist cultural movement of the 1930s. “The Popular Front embraced major blues figures who sang explicitly political songs for a largely White left progressive audience,” Wald says. “Singers like Leadbelly, who sang ‘Bourgeois Blues,’ and Big Bill Broonzy, who sang ‘I Wonder When I’ll Get to Be Called a Man,’ and Josh White was the big one, with songs like ‘Uncle Sam Says,’ ‘Trouble’ or ‘Bad Housing Blues.’ ” White, Wald notes, “was asked to come to the White House to sit down with FDR and talk about what Black people want.”

Donald Trump would never have invited Copeland for such a chat, though she did join other blues stars to sing “Sweet Home Chicago” at the Obama White House in 2012. The eponymous first single on “Uncivil War” laments our bitter divides, and Copeland tries not to alienate anyone when she’s talking between songs onstage or DJ-ing her weekday show on SiriusXM’s blues channel (a backup gig that has proven a godsend for her since the pandemic interrupted income from live shows), but it’s not hard to tell that she’s on Team Blue. In making the move from Chicago to Nashville, two blue cities surrounded by red hinterland, she has found a kindred spirit in Kimbrough. He has exercised chameleon-like adaptability in making music with artists from Emmylou Harris to Jimmy Buffett, but his own work — like the antiwar, anti-greed-themed album “Americanitis” — displays a strain of southpaw critique. Kimbrough, known as a guitar wizard, shares not just Copeland’s progressive politics but also her disdain for guitar-hero overkill, so as producer he scrupulously restrains his own playing in the service of framing to best advantage the words she sings. “You have to beg him to take a solo,” she mock-complained to me. “Take a damn solo, Will.”

Wearing headphones, Copeland sat on a high stool at a microphone in a small room in the Butcher Shoppe, a recording studio in Nashville co-owned by the Americana patron saint John Prine, on a Monday morning in early December 2019. In town to record vocal tracks for the dozen songs on “Uncivil War,” she was dressed all in black, from leather boots to wool watch cap. In the next room, Kimbrough led a veteran crew of local session musicians into the shuffle groove of a song called “Money Makes You Ugly.” They locked in on the rocking sweet spot between push and drag: plenty of drive to propel the song onward, just enough hold-back to give it a satisfyingly nasty quality of thickness and churn. “The ice is meltin’ and my lawn’s on fire,” Copeland sang. “The world’s got a fever gettin’ higher and higher.”

As she sang, she tapped into the original rush of anger inspired in her almost a year earlier by an interview with Donald Trump Jr. she saw somewhere — she can’t remember where. She’d gotten on the phone to Hahn, who had seen the same interview and was similarly incensed. “He’s totally out of touch with life in this country, like his father,” Copeland had said to Hahn. “He thinks the reason people are poor is because they don’t work hard enough.” (I have not been able to find any record of Trump Jr. making a public remark in early 2019 to the effect that poor people should work harder. Copeland and Hahn backtracked on their digital trail at my request to see if they could find it, and they couldn’t. Whatever he actually did say seems to have bounced around in the segmented echo chambers of our political culture until Copeland and Hahn heard it as such.)

Copeland talks with Hahn at least once a day, and many of the songs he writes for her come out of the back-and-forth of these conversations. After they got off the phone, Hahn, who had already been contemplating a song about privilege without conscience, wrote a fiery condemnation of the rich and powerful for screwing up the world. Hahn, a lyricist but not a musician, sent it to Kimbrough to put the words to music. Hahn envisioned a foot-stomping burner, but when they got together in the kitchen of Kimbrough’s house in Nashville to work on it, Kimbrough explained that they had to pace the song to fit the words. “When I’m hearing it, my little brain goes to a minor key,” he said. He was all in black: jeans, T-shirt, Clark Kent glasses, bed head. “Almost like a ... ” He trailed off as he picked up an acoustic guitar and chunked out a groove in B minor, humming a descending strain over it. “ ’Course, there’s a lot of words,” he added. Touching upon climate change, fracking, lead-poisoned drinking water in Flint, Mich., and more, the song had turned out to be as much about the environment as about inequality. “Whoever told you that you own this place?” the singer asks the apocalyptically spoiled plutocrat to whom it’s addressed. “Think of ‘Gimme Shelter,’ ” Kimbrough told Hahn and Copeland as they sat with him at his kitchen table. “That’s the maximum speed. It isn’t fast, but it rocks.”

Now, in the studio eight months after that kitchen session, Copeland felt for her original outrage — “It’s the attitude of not knowing or caring what people have to do to get by that gets me,” she had told me — and poured the feeling into the groove crafted by Kimbrough’s crew. After they had recorded a couple of takes, everyone crowded into the control room of the Butcher Shoppe to listen to playback. I noted that Copeland had been revising Hahn’s lyrics on the fly, substituting “dirty water” for “water from Flint.” She said, “Yeah, keep it simple — make your point and get out.” The blunt, earnest songs she conceives with Hahn tend to be least preachy when most concise. “We try to address the issues without lecturing people,” Hahn said.

Blues songs may sound straightforwardly simple, but it’s not easy to write one. “There’s not many people around today that really do it well,” the prolific bluesman Keb’ Mo’ told me. “There’s a way that it’s got to be done to be effective. Every verse is like a chorus.” He was referring to the haiku-like spareness of a classic blues lyric like Elmore James’s “The sky is crying, look at the tears roll down the street.”

Hahn tends to be more didactic, placing priority on engaging the issue he and Copeland want to address. As a result, his lyrics can sound like talking points, which has been a trait of blues protest songs going back to their Popular Front heyday. Compared to a dark-night-of-the-soul epic like Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” (“I got to keep movin’ / Blues fallin’ down like hail”), for instance, Leadbelly’s “The Bourgeois Blues” (“Home of the brave, land of the free / I don’t wanna be mistreated by no bourgeoisie”) can seem stiff. Similarly, a couplet from “Money Makes You Ugly” like “Your conscience was laid off with all the people you fired / Took back their benefits before they retired” doesn’t roll off the tongue or sink resonantly into one’s consciousness in the way that, say, Jimmy Reed’s “Bright lights, big city, gone to my baby’s head” does.

When she was recording in December 2019, Copeland’s new album seemed on track for a summer 2020 release, timed to arrive well in advance of Election Day and its long news shadow. But the coronavirus, just then crossing from animals to humans in Wuhan, would wreck all manner of plans as it spread around the planet. It would wipe out live musical events, on which the blues business heavily depends, and take the life of the beloved John Prine, whose studio Copeland was using and who had duetted with her on his song “Great Rain” on her previous album, the award-winning “America’s Child.” “She doesn’t sound like anybody else,” Prine had told me when I caught up with him backstage at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, the Mother Church of Country Music. “It’s a blues voice, but it’s so clear and proper and righteous. I’m so glad she’s come down here.”

The Black Lives Matter protests of the spring and summer, part of a cultural climate of growing attention to racial injustice that just might inspire demand for some fresh (or freshly revived) protest music, were still in the future, too. The album, originally titled “Living With Ghosts” and scheduled for summer release, would be delayed until October and retitled “Uncivil War,” and it was anybody’s guess how it would fare if she couldn’t tour in support of it.

So far, the album has done well. It has earned strong notices in publications from Rolling Stone to the Wall Street Journal, and on NPR, and it has showed up on best-of lists for 2020 — including at No. 1 on the list compiled by the veteran rock critic Jim DeRogatis, co-host of NPR’s “Sound Opinions” show, ahead of Americana critical darlings like Jason Isbell and Lucinda Williams, the hip-hop stars Run the Jewels and the pop star Dua Lipa. “Uncivil War” also opened at or near the top of blues charts and received respectful reviews in the blues specialty press, and Copeland still enjoys her perennial front-runner position in blues awards competitions — all of which suggests that her explorations of Americana have not alienated the sensibilities of her blues base.

At the end of a long recording day, Copeland decided to do one more song, a cover of “In the Dark,” a lovelorn midtempo shuffle recorded by Junior Parker in 1961 and definitively transformed into a magisterial slow blues by Lonnie Brooks in the 1970s. The band settled into a restrained groove, and Copeland launched into the first verse: “I heard you was out / High as you could be / Kissin’ other women / And you know it wasn’t me.” The signature mood of slow blues in a minor key descended, and everything else seemed to fall away — the ripped-from-the-headlines political convictions of the newly written songs on the album, the desire to reach beyond the blues scene for a broader audience and new musical challenges and topicality — as she poured herself into the old familiar vocal swoops and bends, the crushing tension and soaring release at the heart of the blues. “That ain’t right, babe,” she sang. “No, no, no, that ain’t right.”

The Queen of the Blues did her best singing of the day on this old song with no obvious political content or subtext. She had decades of singing in prime voice ahead of her, and she was decades younger than the boomers who made up the core of her blues audience. Nashville might yet provide the solution to that problem, but this performance was pure Chicago. “What goes on in the dark,” she sang, “will soon come to light,” and her elongated reading of “soon” was a mini-suite of sustains and twisting leaps resonating with grievance, hope and an aching for redress. If she could figure out how to consistently infuse her purpose-built political songs with the undeniable feeling that pulsed in her rendition of this heartbroken standard, she might yet make herself the Queen of Blue America.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Carlo Rotella is a professor of English, American studies and journalism at Boston College. His most recent book is “The World Is Always Coming to an End: Pulling Together and Apart in a Chicago Neighborhood.”

Designed by Twila Waddy. Photo editing by Dudley M. Brooks.

https://www.wbgo.org/2021-07-22/shemekia-copeland-modern-guardian-of-the-blues

Shemekia Copeland, Modern Guardian Of The Blues

Whenever we talk about "guardians of the blues," imagining a guy with a guitar is a common default. Whether or not there's any truth to that cliché, the music's stewardship also belongs to someone like Shemekia Copeland, whose voice and presence embody it.

A force on the ground since the mid-1990s, when she was attending Teaneck High School in New Jersey, Copeland has distinguished herself as one of the leading blues artists of our time, not just for the vibrant authority in her singing but also for her choices with style and repertory, up to and including the 2020 album Uncivil War.

In this episode of Jazz Night in America, we'll hear Copeland perform some of that material from Dizzy's Club in New York, along with portions of her firecracker set at the 2021 Exit Zero Jazz Festival. And we'll learn more about Copeland's blues birthright, established by her father — he was one of those guys with a guitar, the late Texas bluesman Johnny Copeland.

We'll also hear a testimonial from Alligator Records founder Bruce Iglaur, who signed Shemekia at 17, along with insights about her place in the culture from noted music scholar Tammy Kernodle. But the primary voice in our show, whether speaking or singing, is rightly Copeland's. "I know I sound like a 1980s beauty queen talking about, 'All I want is world peace,' " she says. "But in all honesty, that's what I want. I want my kid to grow up in a world where we accept each other, love each other and we don't have all this horrible divisiveness."

Musicians:

Shemekia Copeland, vocals; Arthur Neilson, guitar; Ken "Willie" Scandlyn, guitar; Kevin Jenkins, bass; Robin Gould, drums

Video set list:

Radio set list:

Credits:

Writer and Producer: Alex Ariff; Video Producers: Mitra I. Arthur, Nikki Birch; Host: Christian McBride; Videographers: Bronson Arcuri, Mitra I. Arthur, Nikki Birch, Nickolai Hammar; Video Editor: Mitra I. Arthur; Production Assistant: Sarah Kerson; JALC Music Engineer: Rob Macomber; Exit Zero Jazz Festival Engineer: Tyler McClure; Exit Zero Jazz Festival Mixing Engineer: Corey Goldberg; Audio Mastering for Video: Andy Huether; Project Manager: Suraya Mohamed; Senior Producer: Nikki Birch, Katie Simon; Supervising Editor: Keith Jenkins; Executive Producers: Anya Grundmann and Gabrielle Armand.

Produced in partnership with WRTI, Philadelphia. Special thanks to Michael Kline, Paul Siegel, and John Hahn.

Stream Jazz Night In America on Spotify and Apple Music, updated monthly.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.