SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER THREE

MAX ROACH

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

GENE AMMONS

(September 14-20)

TADD DAMERON

(September 21-27)

ROY ELDRIDGE

(September 28-October 4)

MILT JACKSON

(October 5-11)

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN

(October 12-18)

GRANT GREEN

(October 19-25)

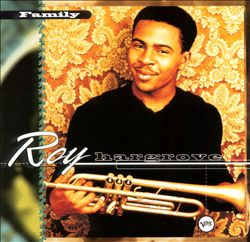

ROY HARGROVE

(October 26-November 1)

LITTLE JIMMY SCOTT

(November 2-8)

BLUE MITCHELL

(November 9-15)

BOOKER ERVIN

(November 16-22)

LUCKY THOMPSON

(November 23-29)

Roy Hargrove

(1969-2018)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Roy Hargrove

was a hard bop-oriented musician (and acclaimed "Young Lion") who

became one of America's premier trumpeters during the late '80s and

beyond. A fine, straight-ahead player who spent his childhood years in

Texas, Hargrove met trumpet virtuoso Wynton Marsalis in 1987, when the latter musician visited Hargrove's high school in Dallas. Impressed with the student's sound, Marsalis allowed Hargrove to sit in with his band and helped him secure additional work with major players, including Bobby Watson, Ricky Ford, Carl Allen, and the group Superblue. Hargrove attended Berklee for one (1988-1989) before decamping to New York City, where his studio career took flight.

In 1990, the young Hargrove

(he was only 20 at the time) released his first of five recordings for

Novus. He often toured with his own group, which for several years

including Antonio Hart. In addition to Novus, Hargrove also recorded for Verve and served as a sideman with quite a few notable figures, including Sonny Rollins, James Clay, Frank Morgan, and Jackie McLean, and the ensemble Jazz Futures. His Verve album roster includes 1995's Family and Parker's Mood. Habana (a Grammy-winning album of Afro-Cuban music) and Moment to Moment followed at the end of the decade. Hargrove also went on to contribute to well-received R&B albums by Erykah Badu and D'Angelo, but he also remained indebted to hard bop with such albums as 2008's Earfood. A year later, Hargrove returned with his 19-member big band on Emergence. Sadly, Hargrove

died in November 2018 at the young age of 49; he had been on dialysis

for well over a decade and died from cardiac arrest associated with his

kidney disease.

https://tedpanken.wordpress.com/tag/roy-hargrove/

* * * *

For Roy Hargrove’s 48th Birthday, a 2009 Conversation for Jazz.Com and a 2016 Downbeat Blindfold Test

This contains the intro from a May 2011 post, which contained a long Q&A that I conducted with Roy for the http://www.jazz.com website. After that, I’ve posted the full proceedings of a Downbeat Blindfold Test that Roy did with me in January 2016.

*******

This evening, trumpeter Roy Hargrove brings his working quintet (Justin Robinson-alto sax; Sullivan Fortner-piano; Ameen Saleem-bass; Montez Coleman-drums) into the Village Vanguard to launch a two-week run. He’s morphed gracefully from young lion to esteemed veteran, is one of most singular trumpet stylists out there, and has incubated no small number of next generation movers and shakers in his bands over the last 15 years, and yet gets less dap from the jazz media than his abilities, conceptual daring, and body of work would merit.

I’ve been following Roy since he hit NYC twenty-plus years ago, and finally had an opportunity to do a piece on him in 2009, when I was doing a lot of work for the jazz.com website. This Q&A was conducted on August 11th of that year, in the offices of the Jazz Gallery.

* * * *

By his own account, Roy Hargrove spends about two-thirds of his time on the road, as was the case over a seven-week summer 2009 sojourn during which he toured all three of his bands—his quintet and big band, both devoted to hardcore jazz, and his crossover unit, the R.H. Factor. Back home in New York for a week, Hargrove was decompressing, relaxing in the daytime and spending his nights jamming at various New York venues—Small’s, Fat Cat, and the Zinc Bar in Manhattan; Frank’s Place in Brooklyn. Still, on this hot Tuesday afternoon, the 39-year-old trumpeter, resplendent in a pink-check jacket, shorts, and a narrow brim, strolled into the Jazz Gallery exactly on time for a discussion framed around his new recording, Emergence [EmArcy], his first with the big band, following strong quintet releases from 2008 and 2006 entitled Ear Food [EmArcy] and Nothing Serious [Verve], respectively, and Distractions [Verve], also from 2006, and his third recording of R.H. Factor.

In point of fact, Hargrove may be singular among mainstem-oriented hardcore jazzfolk of his age group in his projection of an old-school attitude regarding road warriorship, song interpretation, blues feeling, and swing, while simultaneously tuning in to the popular music of his time on its own terms. Which of Hargrove’s peers of comparable visibility would embrace the requirements of playing third trumpet in the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band with as much enthusiasm as Hargrove devotes to the various ensembles that he leads? Which other highly-trained post-Boomer would deliver a lyric like “September In The Rain,” a staple of Hargrove’s sets for at least a decade, with as much brio as Hargrove projects when uncorking cogent, thrilling solos on structures ranging from bebop to post-Woody Shaw harmonic structures? Indeed, in his ability to blend the high arts of improvisation and entertainment with equal conviction, Hargrove is a true descendent of such iconic elders as Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, and Dizzy Gillespie, all musical highbrows who wore their learning lightly.

How does the big band sound now vis-a-vis when you did the record, after playing quite a number of gigs over the last year?

It’s really tight. I’m trying to get them to the point where they have the music memorized, and don’t have to use the written music any more—being able to play by ear is so important. When I played with Slide Hampton and the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band, I tried to memorize the parts so that I could pay attention to everything that’s going on with the conducting, with the dynamics, and try to make it very musical. It’s getting close.

How big is the book? There are 11 tunes on the recording.

There’s probably 30 songs or so.

In the program notes, you stated. “I always wanted to work in a big band format. The sound is so full and rich, and it provides opportunity for congregation, which is much needed among today’s younger musicians, most of whom have come of age in small group settings.” I’m also thankful for the opportunity to exercise my compositional and arranging skills. Music is such a vast world, and I intend to explore every avenue possible. The cast of players on this project are all guys I met in school and on various gigs and jam sessions over the last twenty-odd years. I think we all share a strong passion for music that comes from the heart.”

Two themes arise which are a common thread in your career. One is this notion of congregation, communication through music, speaking across generations and styles. Then also curiosity, hunger for information. I can recall watching you as a young guy getting your butt kicked by the elders at Bradley’s, and not being daunted or fazed, but taking it in a constructive way and coming back for more.

True.

Now, in the liner notes, Dale Fitzgerald writes that the first day he met you, you told him that to have a big band was an aspiration. You were always interested in that notion?

Yes. I always watched Dizzy’s big band on video, and it was very inspirational to me. When I started to embrace playing jazz as a teenager, the big band format was my training ground, in learning how to read, and learning how to play in a section in a group. For me, it’s kind of going backward. Earlier, there were big bands and then they went to the small groups; now it’s small groups, and I’m trying to bring back the big band thing.

I believe it’s really important that we all have to know each other when we play together. Most big bands, if it’s a great ensemble, the soloists are ok—they have one or two. But this group is a band full of soloists, so it’s challenging for me to try to bring them all together and have them play where the entire ensemble is thinking in the same direction, with tight cutoffs and everybody breathing at the same time—the things that normal big bands do. A few guys work in the Broadway shows, so they have a lot of experience…everything’s by the numbers. So there’s a balance between discipline and at the same time keeping it very loose and spontaneous.

You just mentioned that watching videos of Dizzy Gillespie’s big band was an early influence.

Yes. The way Dizzy conducted the band, and the way he seemed to have so much fun—and they were having fun. This was inspirational to me, and I wanted to have a group like that.

Playing with the Dizzy Gillespie All Star Big Band over the last number of years has probably been a great training ground in putting together your own group.

Oh, it’s been great. Especially playing in the trumpet section there, playing the third trumpet part on Slide’s arrangements. The third trumpet part is a kind of focal point within the band, because you get to hear all the different ensemble parts written around the voicings. A lot of times, the third trumpet part, or even the third trombone part, has special notes that make the chord grow. I’m a sponge, listening to everything and taking it all in. It just gives me more information to transfer along to the group.

The program of Emergence contains many flavors—Latin, straight ballads, you sing a bit, exploratory pieces arranged by Gerald Clayton and Frank Lacy. But somehow, the template seems rooted in the mid-‘50s Dizzy Gillespie Big Band; the Ernie Wilkins-Quincy Jones synthesis of Dizzy and the Basie New Testament band, seems to be a jumping off point for the feeling you have in mind.

Exactly.

It’s a nice blend of art and entertainment.

I think that musicians should always have fun when they play. Sometimes it gets too serious. That’s just my opinion. When we play, it has to be tight, but at the same time I like to have the freedom to go outside of the box a little bit.

Talk about the process of recruiting this band.

Now, that’s difficult. With a big band, there’s hardly ever any money to pay guys, so it’s hard to get cats to be available.

It started off as a sort of Monday workshop thing, as often happens around New York…

Actually, the first hit was about 15 years ago, in Washington Square Park, where I was able to pull together a kind of all-star thing, with Jesse Davis and Frank Lacy, and even Jerry Gonzalez in the band—Jerry was playing fourth trumpet and percussion! I was able to do that first hit because the Panasonic Jazz Festival, which was running the event, paid us enough that I could give each one of those guys a grand or something. They were excited. “Ok! You got some more gigs?” But at the same time, throughout the process, the music grabbed them, too, and here it is, fifteen years later, we’ve brought it back, and everybody seemed to want to be part of it.

The other thing is that there aren’t really any gigs out there, and there’s a lot of musicians. People want to play. So it wasn’t that difficult to find musicians to be in the group. But it’s always a different gauge to try to find people who are available. For example, we did a few things here at the Jazz Gallery, and I was trying to find trumpet players. We shifted around a few different people, but we finally got what seemed to be a lineup of ringers—Tania Darby, Frank Green, Greg Gisbert are all very good lead players, too, and Darren Barrett, who I went to Berklee with, is a great soloist—Clifford Brown-Donald Byrd stuff. I guess finding the trumpet section was the hardest part; for a while, we had some mishaps. But we managed to pull it together.

I’m always at jam sessions, like I was last night, so I’m always running into musicians. I just go into my mental rolodex and pull out the people I know.

It takes time to accumulate a book. How did you accumulate repertoire?

I arranged a few of my songs for it, just to begin, then I told the cats, “If you want to write something, bring it in.” For this album, I asked Saul Rubin to write the arrangement on “Every Time We Say Goodbye,” and I had written “Tchipiso” and asked Gerald Clayton to do the arrangement. Then, of course, there’s our theme song, “Requiem,” by Frank Lacy, which we’ve been playing. That’s the chop-buster for the whole band; they like to play it, but it’s kind of difficult. It’s very powerfully arranged.

I try to include the music that I learned when I came to New York, from cats like John Hicks, Walter Booker, Larry Willis… Right now, a friend of mine is working on an arrangement for Hicks’ “After the Morning,” which we used to play at Bradley’s all the time. My premise is to try to pass down the information I picked up from cats like John Hicks, Walter Booker, Clifford Jordan and Idris Muhammad when I started cutting my teeth in jazz.

Apart from the Dizzy Gillespie All Star Big Band, what other big bands have you been part of after high school?

I think that’s the only group I’ve actually played in. I’ve sat in with a few, played with some large ensembles here and there, but not anything that happened more than once.

Playing in big bands was a rite of passage for many of the older musicians who were your heroes, who came up before 1955-1960.

That’s why I think the music needs this. It creates some kind of humility. It’s very needed. Excuse me, but a lot of times, especially now, when I got to the jam sessions, people are so ego! I’ll give you an example. We’ll play an F-blues, and everybody with an instrument will get up and play, and it goes on for three hours. Each musician will play 100 choruses. There’s no humility there. Big bands, large ensembles create an environment where you don’t have to play for two hours and stretch out. Everybody can’t be John Coltrane! Sometimes you can just play half a chorus. Charlie Parker will play a half chorus and blow your mind! There’s something to be said about being able to trim it down—say less but have it have more meaning.

Is that something you learned early on, playing in your high school big band?

No, I didn’t learn that early on. I’m still trying to learn that!

It’s a quality that you aspire to.

Yes, I aspire to it. Sometimes, you have to make the amount of music that is just enough. You don’t have to over-crowd it.

How do you see this band vis-a-vis other contemporary big bands? It isn’t as though the scene is totally devoid of big bands, though there aren’t so many that work steadily.

Yes, there aren’t that many.

Maria Schneider, the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, the Vanguard Orchestra, the Mingus Orchestra, Carla Bley…

My group is not quite that streamlined. I’m still trying to get it to that point. My group is filled with hooligans.

No hooligans in those other bands?

No hooligans over there. There’s plenty in my group, though. My vision of that just seems like there’s those groups, and they’re all very clean-cut and organized, and then there’s my group, which is complete chaos. A lot of characters. It’s never a dull moment around those guys. When we’re hanging or traveling on the train, all I have to do is go around them, and it’s entertainment all day.

Does the composition of the band somehow reflect your personality?

Maybe so. I’ve never really thought about it like that, but yeah, probably.

So you’re talking about camaraderie and the jazz culture. This band evolved through this location, the Jazz Gallery, which has served over its decade-plus…

As a breeding ground.

…as a breeding ground and also a kind of communal space for a lot of young musicians from many different communities.

That’s right.

Talk a bit about the interface between the Jazz Gallery and the evolution of this project. Your quintet identity was already long-developed, but the big band identity not so much.

I have to give it up to Dale Fitzgerald, because it was his idea to bring this back into the picture. The first gig we did here at Jazz Gallery, people got really excited. That got the ball rolling. Then I got excited about it. I figured, well, it’s been over ten years; we might as well record the thing now, try to take it out on the road. I guess that’s an uphill battle, considering the economy and everything else going on right now. But still, I think it’s very needed. The kind of conversation you’ll get with it is worth more than money. To me. Because it would help if we can feed jazz with something fresh. It’s difficult right now. People don’t want to swing any more. That dance element is getting buried, more and more and more. It’s got this esoteric sound. People want to be so hip. They want to create the new thing. But the new thing, to me, is the dance. They’ve buried that. I like hearing drummers when they play the ride cymbal. You can’t get drummers to play the ride cymbal any more. They’re always playing like a drum solo throughout the whole song. The ride cymbal, that is your beat. That’s your identity. The way the bass and the drums sound together is a big deal. People just forget about that. Everybody’s on their own program. That’s why I’m doing this whole big band thing. That’s why I’m doing all three bands. Instead of music just being in the background, music should be like therapy for people. When you go to hear music, you should feel better when you leave. Like you’ve been to the doctor and he heals you.

Another flavor of this band which also hearkens to Dizzy Gillespie is your embrace of Afro-Cuban rhythms on several pieces. Two things come to mind. One is that the Jazz Gallery has been an incubator for some of the most creative Cuban jazz musicians of this period…including some of the more esoteric ones.

Excuse me!

But then also, it’s the place where Chucho Valdes entered the New York picture during the ‘90s, and the venue where you first touched base with him and gestated Crisol. Let’s talk about Afro-Cuban rhythms and how they fit into your notions about swing.

It goes back to the dance thing. When I went to Cuba the first time in ‘96, they was partying in there! Here’s people who don’t have anything, they can’t even go to the store and buy orange juice. You’ve got to go to somebody’s house to buy beer, or something to drink. They don’t even have their own bathrooms. It’s crazy. But when they party, when the music starts, it’s like a festival. They REALLY know how to get down. This inspired me…the possibilities exploded in my head. I owe so much to Chucho for turning me on to that world. Before that, I had no idea. Not really. Not like that, before I went down there and saw it for myself. The level of virtuosity with the musicians in Cuba is out of this world! One guy would have five different facets in his realm. For instance, you might have a trumpet player who plays congas and is also a visual artist who can dance.

When I hung out with Anga and Changuito, playing with these guys, even though they didn’t speak English, I was still able to communicate with them through the music, and they showed me so many things. They showed me how to play the different rhythms based on the clave, things that inspired me… But I didn’t really get to dive into it on this album the way I wanted to. We had one percussionist. I wanted to do a bunch of overdubs, but we didn’t have time to get into it the way I really wanted on the big band thing. There’s still some music floating around from the Crisol era that hasn’t been released.

Did the Cuban experience have an impact on your improvising style, on the way you phrase? Is it something you can dip into, go out of? How does it play out for you?

Just being around those guys, I soaked in some of that. I’ve always been into rhythm and movement. When I play, I’m trying to be a part of the dance. I want the music to go into your body, the way you feel where you have to tap your foot and snap your finger, or move your head, or something. Hanging out with those guys strengthened that feeling, made it more prevalent. When I play, I’m thinking about the drums the whole time, and trying to sit in to the rhythm of whatever the drummer is doing. I pay attention to the drummer always. If the drummer isn’t really happening, then I can’t really play. Sometimes I can, but most of the time it’s a struggle if at least the time is not steady.

So it isn’t so much the style or whether they’re playing swing or straight eighth that’s important, but the quality of the beats. Or is that not the case?

It’s a combination of things. It’s the steadiness of the beat and also the way it feels, like if it has an oomph behind it as opposed to it being very quiet, subdued. I prefer to play with a lot of energy. That’s why I liked having all those drums when we were doing the Latin project, because it inspires me to play with energy and force. Drums and brass just go together.

Let’s segue to the R.H. Factor project, which is a much more explicit manifestation of your dance orientation.

In the beginning, I started off trying to do a tribute… My father was a record collector. He had foresight. People used to come to our house to see what we had, so they could go and buy it. They wanted to know what the new thing was going to be, because my father would have it.

So whatever Roy Allen Hargrove was getting, that’s what…

Yeah, they used to come to our house to see what he had in his collection. Every weekend, my dad would buy two or three records, and come back home, and then two weeks later it would be a hit. He just bought what he liked, but apparently that would be what everybody else liked, too—but later. I lost him in ‘95. So I wanted to do a tribute to him in a way that… He always said to me, “I like the jazz, but when are you going to do something a little bit more contemporary, something funky?” I’d say, “I’m getting to it.” He got out of here before I could do it. So I began to collect all of these recordings from my memory, out of what I knew he had. I would go out and get Herbie Hancock with Headhunters, and Earth, Wind & Fire, and George Clinton—just reeducating myself. I’d always been doing little home recordings of my own original music, and I decided to take a few of them out of the archives and transfer it into a live setting, which was the beginning of R.H. Factor. We went into Electric Lady Studio for two weeks. Once the word got out that I was doing something different, all the musicians in New York started coming through!

A lot of musicians.

A lot! I’m saying every day it was somebody new. It’s funny how the world is small. When the word gets out, it gets out. You know how that is, here in New York. We were at Electric Lady, and the first day I couldn’t find anybody. Nobody was around. I didn’t have a bass player, no drummer, no nothing. It was just me and Marc Cary, trying to get it started. We had Jason Olaine calling around, trying to find us a bass player. Finally, Meshell Ndegeocello popped up and brought her drummer, Gene Lake, and that’s how we got started—and the whirlwind of creativity began at that point. For two weeks, cats were just coming… Even Steve Coleman came by one day. There were some people who I actually called to come through, more mainstream entertainers like Q-Tip and D’Angelo and Common, Erykah Badu. These are my friends. It was a little bit difficult to get them, but they still came through. The only problem was that the budget spiraled out of control, because there were so many musicians, and they had to pay all of them. But that first one, once it got off the ground, was a lot of fun to do. I had Bernard Wright there, and my homeboys from Texas —Keith Anderson, Bobby Sparks, and Jason Thomas. That’s the nucleus of what was going on.

Just let me interrupt momentarily. Erykah Badu, Q-Tip, D’Angelo, Common, were all people you’d come to know during the ‘90s. Now, you’re best known as the leader of a hardcore jazz quintet playing swing, in a milieu where the jazz police are serious.

Mmm-hmm. But I never paid attention to that.

Well, you mentioned your father’s question, “when are you going to play something more contemporary?” That made me wonder whether there was a tipping point where you decided…

No-no. I never was satisfied with just staying in one place with music. I get bored. I always try to keep it rounded. When I was in school at Berklee, people thought I was strange because I would hang out with the jazz guys and the R&B cats, and then just sit there and listen to the gospel choir, saying, “they don’t understand.” Because there especially I met people who got into their locked-in things. You’ve got the guys that just play like Bird, then ones that just play like Coltrane. You got the guys who are strictly R&B, and they think the jazz guys are stuck up. You got the jazz guys who think the R&B guys are ignorant and can’t play changes. I never really sank my teeth into being in one of those groups. When I started recording professionally, I chose to do straight-ahead jazz, because that’s where my development was at the time, and I was trying to learn how to do it. I thought there was enough people trying to rap and do all that other stuff. There was enough of that at the time! I’m fascinated by Clifford, Fats Navarro, and these guys who were like institutions.

It was high art.

Yeah. I’m fascinated by that. Once I got locked on to that, I couldn’t stop. For me, it’s a blessing to be able to record jazz in THIS day and age. So I just went with that. But then, when it came time… Actually, it was really difficult for me to try to branch out and do something that wasn’t jazz. When I make a jazz recording, no one says anything. They’re just like, “Ok, take 3. Thank you.” Or “maybe we need another one, just for safety.” But then, when I started branching out into something else, everybody had an opinion. Everybody wanted to try to tell me how to write the songs, how to arrange the songs, do this, do that, “you’ve gotta get this singer, you’ve gotta get that one.” Everybody became an authority. People in the jazz world, they all think, “He’s a bebopper, he doesn’t know what he’s doing; he can’t play that.” But I’m from the generation that hip-hop came from, so it’s going to come out of me, too. I mean, my favorite group was Run-DMC when I was like 13 and 14. I actually bought Kurtis Blow’s first album.

Did your father like hip-hop?

He had one song he liked, “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash. “Don’t push me, ‘cause I’m close…”

In his very warm liner notes, Dale Fitzgerald writes that you started playing in an elementary school jazz ensemble in Dallas. Then people started hearing about you when you were 14-15, when you attended Booker T. Washington High School, which had a distinguished lineage stretching back to the ‘40s and ‘50s. During that time, were you working outside school? Blues bands, R&B bands, church situations?

Yeah. Once I got hit by the music bug, I couldn’t stop. I wanted to do it all the time. They had to pull me out of the band room. I was the first one there, and always the last to leave. I’d stay there until 5 or 6 o’clock in the evening, because I loved it so much. It was also a kind of deterrent from being in the streets. People talk about South Central L.A., but South Dallas is no joke! Erykah is from South Dallas. We went to high school together. Yeah, people don’t talk about South Dallas. If you picture the ghetto in South Central L.A., or Compton, which they glamorize on TV and have the gangs… Just imagine ten times that. It’s so bad, they can’t even show it on TV. You go to Texas, and the ghetto is crazy. People are just crazy for no reason! I grew up around that in the 1980s, the late ‘80s, when a lot of gangs were beginning, and there was a lot of crack. One time my father told me I couldn’t go outside after 6 o’clock. So being around all that…having music really helped. Having something to do to keep me out of the streets. Otherwise, it might have been trouble. I’m thankful for that.

Did the idea of having a distinguishing voice on the trumpet come to you pretty early? Were you modeling yourself after the cats you were listening to? Did it just naturally come forth somehow?

Being in Texas, you hear blues all the time. Blues all the time. People love to listen to the blues. Every Sunday, my father and his friends would get together and play dominos, and put on Z.Z. Hill and B.B. King and Bobby Blue Bland, and listen to the blues. My grandmother and my aunts and all of them had 8-track tapes of Tyrone Davis. A lot of blues. So the blues gets in there. So when I first started learning how to improvise and took my first solo, it was based on playing the blues. My band director showed me a couple of licks… I guess coming up in church, you learn how to project yourself emotionally through your instrument, if you play an instrument, or if you sing—whatever you do. Texas is the Bible Belt. People know what that is when you go to church, and somebody sings a solo. That becomes a part of you. My grandmother put that in me when I was little. My spirituality has always been what keeps me going. That’s what is coming through.

It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I started to hear people like Clifford Brown and Freddie Hubbard. Now, hearing Freddie Hubbard pretty much turned my whole life around. Clifford Brown at first, because I had never really heard jazz trumpet like THAT. Clifford’s technique was so good that it sounded like he wasn’t even playing trumpet any more. It went into like a woodwind sound almost, as though he had practiced so much and got so good that his sound went past being just a trumpet—it was just music. But then, Freddie Hubbard really got me, because he had a contemporary thing in his sound—it reached back to cats like Clifford and Fats Navarro and Dizzy, but it also had a thing from my father’s generation, from the ‘70s. I could definitely latch onto that, especially the way he played ballads. I always liked his ballad playing. Just ballads in general. I like to play the slow songs.

So I started from blues, and then I started learning bebop when I came to New York.

That was right after high school?

Well, I was in Boston for a couple of years.

Didn’t you come to New York before you went to Boston…

Well, yes, I actually did, once. But it was for a competition. I was still in high school. I didn’t really leave the hotel.

But before you came to Boston and New York, there were a couple of national figures who entered the picture for you a little bit, right?

Yes. Clark Terry and Wynton. When I sat in with Wynton that first time, I was really nervous. But I thought, “Ok, you’ve got to step up to the plate now; you’ve got to deliver.” I wasn’t afraid, but at the same time I was really nervous.

Is stepping up to the plate something innate in you?

I’ve always enjoyed when people enjoy. When I’m playing and someone is feeling good from that, I’ve liked it, ever since I was little, when I first started. When I play a few notes and somebody goes, “Yeah!” I’m like, “ok, yeah, I want to do that every time.” so yeah, step up to the plate, make it happen.

Back to R.H. Factor and the first record that came out with Common, Q-Tip, and artists like this, what was their sense of you as an instrumentalist? Were they thinking of you as a jazz player? As a common spirit? Apart from the friendship and the collegiality, what was the artistic relationship like?

Like Herbie always says, “I’m a human being first, and a musician second.” I guess there’s something to be said for a doctor with a bedside manner. You have to know how to deal with people. So when I go to the more mainstream artists, I switch the way I work with them as opposed to when I work with the jazz players. In some cases, they’re used to special treatment, and you can’t be so technical.

Give me a concrete example.

For instance, with Q-Tip, I put him in the booth and let him write to the track, and just have the first 8 bars, or something like that, keep looping over and over, For about an hour I left him in there by himself. He wrote to the track, then we went back in and cut it, and he did it first take. But there’s no formula. It’s different with each person. It depends on their personality. With Common it was a little different. He and Erykah were dating at the time, so I had to pull him out of the studio. Finally, I got him out of there at 5 a.m. or something, and he came down. He didn’t even write anything. He just improvised his thing, which was one take. I couldn’t believe he did it in one, so I was like, “Can you do that again?”—and he did it again! It was great. But then I went through all of this crap with his manager, because he didn’t like the improvised thing. He wanted him to write something. I’m like, “You don’t understand what’s going on. I wanted it to be improvised.”

Does this emphasis on bedside manner represent your attitude as a bandleader in all the different situations?

Definitely. It takes patience and forward thinking. You always have to be thinking for the other guy, thinking what he’s going to do. Is he going to miss that note? Ok, is he going to come in? I’ve got to count him in. It’s like a juggling act sometimes, trying to… Well, not really like a juggling act—I’ll take that back. What I mean is, you have to think forward, think ahead. With the big band especially—conducting and bringing in all the different sections and whatnot—you have to always be at least 2 bars ahead.

I guess you have to be like when you’re leading the small band, too, keeping the crowd in mind, what to play at what time—gauging all those dynamics.

I mean, it’s not that much different from the small group to the big groups. I think that, in a way, the approach should be kind of the same. With the small group, sometimes we play the big band arrangements, pared down, which is exciting for them.

A different flavor. Changes things up.

Changes things up, yes.

So you hit New York in 1990 after two years at Berklee. Was being there helpful to you?

Yeah, definitely. Billy Pierce was there. I did my first couple of gigs with James Williams while I was there. Greg Hopkins, too. At Berklee, I was in the Dizzy Gillespie Ensemble, which is how I learned a lot of that book. Greg had some of the same arrangements, so when I got in the band with Slide, I had played a lot of the arrangements before. That helped me professionally. I already had some training, and I got a lot there, too, though I wasn’t there very long. Not just from being in the school, but from being on the streets. Going to Wally’s every night. I heard a lot of great music there, and I got to know some great musicians as well, like Antonio Hart, Mark Gross, Delfeayo Marsalis… Being away from Texas was a culture shock for me, but also very enriching as far as my education in jazz.

Then you get to New York…

Then it got really deep! While I was at Berklee, I was starting to learn a little bit of some bebop, but I was really just trying to learn how to read chord changes. I’ve always played by ear, from when I first started. The first trumpet player got mad at me, because I would play his part, but I’d be down at the third trumpet! I think the ear training is such a big deal, though, especially now. We’re in the information age, and you can get everything at the push of a button. So musicians have to be very complete. You have to be not only good readers and be up on the technical side of playing music, but also be able to play what you hear. That’s sometimes lacking. I know a lot of musicians who can read flyshit, but if you whistle something to them, they can’t play it. Ear training is a big deal.

Anyway, it got deep when I got to New York. I started sitting in with people like John Hicks. I followed John Hicks around New York for a while.

Let’s paint a picture. You were around 19-20, and spending a lot of time at Bradley’s, both playing bookings and sitting in. You were playing with Hicks, and you were playing with Larry Willis, and the musicians who play on the record, Family… I personally remember an occasion when you were sitting in with George Coleman and Walter Davis, Jr. on the second set, they kicked your ass, and then you came back on the last set and hung right in there. I saw similar situations transpire several times. It’s kind of an old-school way of learning, but I think it says something fundamental about you.

I’m very thankful, because people like George Coleman and Walter Davis taught us how to be men on the bandstand—how to be grownups. I never will forget that same night you mention, when I was playing with George and we went through the keys on “Cherokee,” which was like a lesson on harmony and then another lesson on rhythm. Then we played “Body and Soul,” and he started changing up the meters—he played in 3 and then in 5, and then BLAM, really fast. [LAUGHS] Then he turns around to me and goes, “You got it.” I go, “ok. What am I going to do after all of that?” But I stuck to my guns and tried to ride it out. Man, they were so helpful to me. That’s why I think we just need something now. Musicians need role models, something so that they can see how it’s done. I’d glad I got a chance to see it in person. Bradley’s was an institution, to me. It was like going to school. It was like your Masters. You go in there, and you’re playing, and then there’s Freddie Hubbard at the bar! What do you do? This is very humbling. Everything I’m playing right now I owe to that whole scene.

Before I interrupted, you mentioned following John Hicks around the city, and you remarked earlier you’ve commissioned an arrangement of his piece “After the Morning” for the big band. Hicks was a musician who is underappreciated in the broader scheme of things in jazz…

Yeah, but he was a true musicians’ musician. My manager, Larry Clothier, told me about John in the beginning. He said, “You’ve got to hear him; he elevates off the piano. Really. He starts levitating.” When I saw him the first time, it happened! I was like, “whoa!” So I latched on to John, and he was like my uncle. He was like family to me. His music was an influence. I was influenced by a lot of pianists as far as how I write and my approach to harmony. there’s John Hicks, then also Larry Willis, then also Ronnie Matthews, Kenny Barron, too—and James Williams, of course. My writing was influenced mostly by James Williams and John Hicks, the use of the major VII-sharp XI chord. That was my favorite chord when I was in college, and I used to use it on a lot of songs. They showed me how to use that chord, and make it very melodic. Sometimes the guys in my band would get tired, because I would write them like inj parallel… “Man, you got some more major VII-sharp XI chords?” A lot of my tunes had inflections from John or James or even Larry Willis, and they still do today.

One thing that I think shone through at Bradley’s was your ability to play a ballad. At 19 you could have been called an “old soul,” but we can’t really say that now, since you’re turning 40 this year.

I think that’s just my upbringing. I’ve always gravitated towards the slower songs. Ballads have an emotional quality to me. You slow it down, and you hear everything, all the nuances… Maybe I’m a romantic as well. I guess I believe in love! I like the slow songs. I like when it’s broken down. Sometimes that’s where the beauty is, when you bring it in the slow tempo. And I always listened to singers. Nat King Cole and Shirley Horn. Sarah Vaughan is my favorite. Of course, I owe a lot to Carmen McRae. I got to hear her live a lot, and she used to let me sit in with her all the time. Her delivery… I heard Freddy Cole at Bradley’s as well.

There’s a vocal element in my music. I try to play like a singer. I try to sing through my instrument like a vocalist would sing. I’m always thinking about the lyrics. I was told by Clifford Jordan that you have to know the words of the song, because then you really understand what it’s about, and when you play the melody you really understand the mood you’re projecting. Also, it helps your phrasing.

It sounds like there was never any generation gap for you.

Man, I have extreme respect for my elders. I believe in that. Somebody who’s been on this planet longer than me, I have to respect them. Even if they’re dead wrong, I’ve still got to respect them! There’s something to be said about the fact that they’ve been here longer than me, and they’ve survived. When it comes to musicians, it even gets deeper.

Another thing that’s interesting about how Bradley’s played out for you is that, because your business arrangements turned you into a leader quite quickly, it became the primary venue for your apprenticeship. You never did the sideman thing too much, if I recall correctly.

No, you’re wrong about that. I did a lot of sideman things, but it wasn’t anything steady. I started off playing with Frank Morgan and the Ronnie Matthews Trio, and it went from there to Clifford Jordan, Barry Harris, and Vernell Fournier, and then Charles McPherson.

Were these one-offs or were you touring with them?

I was touring with them. I would do a week here, two weeks there with different groups. Most of them were veterans, with me, the young kid, as the special guest. They were so encouraging. Whenever I showed up on the scene with my trumpet, the older guys, like Clifford Jordan, would be like, “Man, come on and play.” Nowadays, people get very protective over the bandstand. You want to go sit in with them, it’s like 2 o’clock in the morning, and they say, “We’re going to play a few songs, and then we’ll invite you up.” You can’t do that at 2 o’clock in the morning, man! It’s too late for all of that. Let’s have some fun! But people get very protective. I think the reason is because there’s no gigs. That creates a thing where when somebody gets a gig, even if it’s 2 o’clock in the morning, they want to play all their original shit and they want to speak their piece.

But the older cats were very welcoming, even though I couldn’t really even play changes that well. “Hey, come on and play.” Sometimes, when I didn’t want to play, they’d be like, “Get on up here.” Like, Kenny Washington one night, we were at Bradley’s, and he was playing some fast, crazy tempo. Kenny was known for playing 220! I went to go sit down, and he was like, “Unh-uh, come back up here.” [LAUGHS] He wouldn’t let me go. “Yeah, you’re getting some of this, too.”

But even if my premise is wrong that you didn’t do so much sidemanning, pretty much you were leading groups from…

I didn’t have my own quintet until ‘93-‘94, with Greg Hutchinson, Marc Cary, Rodney Whitaker, and Antonio Hart. I tried to create a couple of bands before that, but nothing really stuck. I had different projects. I had one group with Walter Blanding, Chris McBride and Eric McPherson early on.

I’d like to talk about your development as a trumpet player over the years. What your weaknesses were, how you worked on them.

Trumpet is a beast! When I was in high school, Wynton referred me to a guy named Kerry Kent Hughes, who was a trumpet professor at Texas Christian University. He was my very first private instructor on that level. I’d been studying at school, and pretty much teaching myself, for the most part. This was the first time I actually had someone who would come to my house and work with me. Man, I learned so much. I couldn’t pay him. We were poor. But he did this out of his heart. He was a classical player, but he also did musicals and shows and so on, and he was very versatile. Actually, he came to the Vanguard the last time we played there, and it blew my mind, because I hadn’t seen him in so long. But Kerry Hughes would come to my house every week or so, and show me little things to help me with endurance. We worked on Cichowicz flow studies and stuff like that, and also the Arban method. This really instilled in me the importance of an everyday routine on the trumpet, certain rudimental things that you do just to keep your chops up. With a hectic schedule and touring when you have to go to the airport and so on, you don’t get a lot of opportunities to practice, so you have to develop a daily routine to keep your chops up. I learned a lot from him in that respect.

I’ve picked up things as I go. A few years ago, I learned something called the Whisper Tone that really opened me up, helped my range a lot, helped me to be able to play more around the horn. I’m still developing, trying to learn as much as I can about the trumpet. It’s a beast. Dizzy says, “It lays there in luxury, waiting for someone to pick it up, so it can mess up your head.” [LAUGHS]

Dizzy Gillespie sure messed up the heads of a lot of people. You don’t hear too many who can emulate him.

I was just listening to something last night, “Birks Works” with Milt Jackson.

At what point do you feel you got past influences?

I’m still not. I’m still there.

Were you transcribing trumpeters? Were you doing it more by feel?

When I was at Berklee, I had to transcribe some Fats Navarro. Jeff Stout was my teacher, and he had me transcribe a couple of Fats Navarro solos. But I never got into transcription as far as writing it down. I don’t think that you get much from that. It’s better if you transcribe by ear and learn it, because some things you can’t really write down all the way—certain inflections and the feel that comes from someone’s conception. But I transcribe a lot by ear, not even really trying to. If I hear something more than three times, I’ve pretty much got it memorized.

That’s a gift, to be able to do that.

Yes, I think so. Thank God for that. But it’s also training. Because if you listen to music all the time, which I do, then it becomes part of you. It becomes part of your breathing. It’s just like drinking water or eating. I listen to music all the time. Even when I’m not listening, it’s still in my head.

So the quintet is your longest continuous entity.

Yeah, I like the quintet format. It has everything there. I have tried some other formats, though. That’s why I like coming to the Jazz Gallery to play, because I get to do other things—like the organ trio is fun.

You’ve also paired off with other trumpeters on various gigs here. Back to the notion of camaraderie and collegiality, it seems that you like to have another voice to play off of.

Yes, I like it.

It doesn’t seem that quartet would be your favorite format.

Well, it depends. With quartet, I would probably play more ballads. But it’s hard to play ballads now, because the young guys don’t know the American Songbook. They don’t KNOW the songs. It’s difficult. I go to jam sessions a lot, and when I start calling tunes, nobody knows anything. You either get “Beatrice” or “Inner Urge.” That’s it!

Gerald Clayton, who was your pianist for several years, has command of that…

He does. He knows the language of it. If he doesn’t know the tune, he can figure it out. For his generation, he’s one of the better ones. But then, his father is John Clayton, so he’s getting it honest. But I could stump him, too. He didn’t know “After the Morning.”

But in any event, you’re always bringing new young musicians into the band. Is there a disconnect for you with that generation?

I miss being able to hear some music that I just can’t get enough of! I’ll give you an example. Just two nights ago, I went into Smalls, and we were hanging out, jam session, everything’s pretty straight line, and then my friend Duane Clemons gets up and plays—and I was so happy! It was like touchdown! Know what I’m saying? It was like throwing a pork chop into the middle of a hunger-starved place. I felt so good just for that little bit. Man, if I could just have a LITTLE bit of that all the time. I was telling Duane that, “Man, you should really play more, because that’s FOOD.” He was playing the real language. He was playing bebop. He was playing the real New York stuff. The real fabric of the language of the music. When you hear it, you know what it is.

You do some workshops and clinics, too. You’re in touch with younger musicians.

Sometimes. I did a thing with Roy Haynes at Harvard not too long ago. It was real cool.

What do you think is alienating musicians from that way of playing? Is it lack of information, or…

Lack of information.

…is it attitude?

It’s both, One feeds the other. First of all, I think people sometimes come into the arts for the wrong reason now—because they want to be famous and rich and have a nice life, instead of trying to reach people’s consciousness and make a difference. Doing something for someone else besides yourself. People come into this, and, “Yeah, I want to be rich, I want to have a car, I want to have people waiting on me,” and so on. It gets weird when that’s your main focus. So you get the jazz musician who learned how to play in school who already thinks he’s learned it all. I like to meet musicians like that, because then I like to challenge them. That’s why I started this big band. I wanted to challenge the peacocks, musicians who think, “Oh yeah, I already know everything.” But you don’t!

They don’t get it. But if you love this music, you’ll go out and find what you need. That’s one thing I like about Jonathan Batiste, the new piano player who’s been playing with me. He seeks out cats like Kenny Barron and Hank Jones. That’s different than the guys in his generation, who are more into McCoy and Herbie—Jonathan checks out the REAL thing. I have to say, he did a great job on this last tour. I was really excited, because he came out and took care of business. This cat played in all three groups.

Jonathan Batiste is out of New Orleans.

New Orleans. What are they feeding them down there?! I don’t understand. Them New Orleans piano players. I had two of them in the past months, Sullivan Fortner and then Jonathan, and these guys are so complete. There was nothing I couldn’t throw at them. I’ve been working towards having the type of group where if I wanted to show them a new song, I could sit down at the piano and play it, and then they’d hear it—I don’t have to write it out or anything. Now is the first time I’ve ever had a group like that; with Jonathan, I could sit down and play it once, and he’d pick it up. Something about New Orleans.

So the present group is either Sullivan Fortner or Jonathan Batiste on piano…

Yes. Amin Salim is playing bass. Montez Coleman is on drums. Justin Robinson on alto saxophone.

Is the quintet a more open-ended format for you than the big band or R.H. Factor?

“Open-ended.” What do you mean?

In your current bio sheet, you remark about the big band, “There’s not much left to chance.”

Yes. With the quintet, it’s always up in the air. The book is so vast with the quintet right now (excluding the new members, like Amin Saleem, who doesn’t know the whole book yet—but he’s learning it) that we can go in any direction you want. I can actually do the Big Band and R.H. Factor set with them, too. This version of the quintet is probably one of the more versatile units I’ve had. When we play the Latin thing, it’s real Latin. When we play some funk, it’s real funky. When we play straight-ahead, it’s tippin’. We can go anywhere. That’s basically my whole premise. I believe in variety, and also I believe in spontaneity. There’s no rule book. As soon as it starts to get to be in a rut, then I change it right away. With the quintet, we never play the same thing. Each night I try to change up the repertoire a bit so that everyone stays focused. We never get bored.

Being a bandleader is very interesting and challenging in that way. You have to keep everybody focused, and also motivated. Even outside of the music, trying to keep morale up is a balancing act as well. When you’re on the road and nobody’s slept for a few days, people get tired of looking at each other and it gets real dark. So I try to keep a very positive energy around everyone, so we keep it going.

You yourself must get tired, too.

Yes. I get tired. But I’m ok. My spirituality is what keeps me going, for sure.

*****

Roy Hargrove, Blindfold Test – Uncut:

Terrell Stafford, “Yes, I Can, No You Can’t” (BrotherLee Love: Celebrating Lee Morgan, Capri, 2015) (Stafford, trumpet; Tim Warfield, tenor saxophone; Bruce Barth, piano; Peter Washington, bass; Daryl Hall, drums)

Wow. This is recent? [2015] Oh, that recent! It sounds good. I like it. It’s recent but it sounds… It’s nostalgic. I know that’s a Lee Morgan tune. I don’t know about the trumpet player, though. That’s Tim Warfield on tenor saxophone. I know his sound. He plays very melodic and I can tell the way he does the vibrato at the very end of his phrase. I remember that from when we used to play together. He sings. [trumpet solo] Huh! You got me. It could be Nicholas. It could be Sean Jones…no, it’s not Sean Jones. Kermit Ruffins? No, not him. I know he’s probably from New Orleans, though. I thought New Orleans because of Tim. He used to play with Marlon Jordan. I couldn’t recognize who the trumpet player is, but I like it. He’s got the blues in there. He’s got a feeling. But you got me. I can’t guess. [last unison] Oh, it’s Terrell. I heard another cut from the same record on the radio, and I remember the sonic quality. I had the same feeling when I heard this on the radio—this sounds like an old record but it’s new…a new musician. It’s a great choice for Lee Morgan, one of my favorite trumpet players, and the execution is great. It’s not easy to play those melodies. The stuff that Lee wrote was hard to play. I know Terrell; he deals with that. 4½ stars.

Alex Sipiagin, “From Reality and Back” (From Reality and Back, 5Passion, 2013) (Sipiagin, trumpet; Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone; Gonzalo Rubalcaba, piano; Dave Holland, bass; Antonio Sanchez, drums)

I don’t know who it is, but I like it. It kind of reminds me of… This is somebody young; it’s one of the younger guys. The style is very progressive. It reminds me a lot of the music I hear the younger guys players now. [this player is older than you.] He is? Is it Wallace? Not Wallace. Wow, you got me again. It’s not Terence. I would have heard that bend. The tune is pretty. I couldn’t really tell what the meter was at first. That’s real nice. That’s pretty. It’s new. It’s a new sound. You can’t really tell what’s going on with the meter. It has its own identity as far as the harmonic approach. It’s very different. I haven’t heard anything like that before. It’s real pretty. It reminds me a bit of Wayne Shorter’s writing style. I was going to say it was Dave Douglas, because I know him. But Alex Sipiagin, I’ve never heard of him. That’s a good player. Nice pretty dark sound. 5 stars. That’s some original stuff there.

Geri Allen-Marcus Belgrave, “Space Odyssey” (Motown and Motor City Inspirations, Motéma, 2013) (Geri Allen, piano; Marcus Belgrave, trumpet)

I don’t think the trumpet player is American. It reminds me of another musician I heard who isn’t American who uses a lot of effects, which I heard in the beginning—an echo thing. I can’t guess that one either. If he’s American, you got me. The trumpet player has a nice sound, great attack, good chops. But I can’t figure out from the improvising; his style is throwing me a little. It’s very expressive. It makes me think of Don Cherry a little, but I know it’s not him. Could it be Olu? [That generation.] Who’s the pianist? [Geri Allen.] Could it be Graham Haynes? It’s in that style, though—sort of. 3 stars. [after] That was Marcus? A new record? Well, that makes sense. It has that darkness to it, like Marcus. Yeah, Detroit. I feel it. That was cool. That sound was very mature. I couldn’t guess it. It was probably an original tune. I’ll have to up the stars on that since it was Marcus—I’ve got to give it 5.

Rodriguez Brothers, “Fragment” (Impromptu, Criss Cross, 2014) (Michael Rodriguez, trumpet; Robert Rodriguez, piano; Carlos Henriquez, bass; Ludwig Afonso, drums; Samuel Torres, percussion)

It’s got some percussion. That’s definitely one of the Latin cats. Which one? I have not a clue! It’s got some Cuban flavor. Is this the kid, Zack O’Farrill, that I did the trumpet thing with? No. It reminds me of the music of Yosvany Terry and some of those guys from Cuba, with the odd meters. They’re swinging now, though. They swing with a Latin thing in it—the tempo. Stumped. I like the rhythm; it’s very strong on this, and the trumpet player has great time. Good sound, too, on the harmony. It’s real nice. 4 stars. [after] I do know him, but I don’t know his sound that well. I haven’t heard him enough to be able to pick him out. We’ve hung out at jam sessions, back when they used to have it at Sweet Rhythm and this other place on the East Side. He was in the Monk Competition, one of the last three guys—him, Ambrose and Jean Caze. Poor guy, they made him go first. His shoulders was tight; he was up in here like that. He’s a very mature player. He’s got great rhythm, and a beautiful sound, too. He got a good sound on the mute, and it’s not easy to do. The mute causes all kinds of intonation disasters. Sometimes it goes out of tune. It gets a very shrill tone. If you don’t have your tone centered, it can be really weird.

Dave Douglas Quintet, “Pyrrhic Apology” (Brazen Spirit, Greenleaf, 2015) (Douglas, trumpet; Jon Irabagon, tenor saxophone; Matt Mitchell, piano; Linda Oh, bass; Rudy Royston, drums)

I was going to say Terence. Not Terence? This is a young guy? [Older than you.] Wow. Bill Mobley? Not Bill Mobley. No, that doesn’t sound like Terence. I’m telling you, listening to all this music is making me want to start listening to new jazz again. I can’t pick this one out either. It reminds me of Terence just in the style, but it’s not him, clearly. Terence has this one thing he does; I always know when it’s him—he has a dip, like K.D. used to do, and Clark. But the composition and the way it’s written kind of reminds me of the way Terence writes. The trumpet player has kind of a vocal thing in his sound, like he’s singing, sort of. It’s very personal. He’s sounding like himself, whoever that is. The tenor player sounds familiar. It’s not him, but it reminds of Mark Turner—the higher register. All right, tell me who it is. I wouldn’t have been able to guess Dave Douglas. I know him, but I don’t have any of his records. What would make me guess it’s him is if it had been a different instrumentation, because he uses unorthodox stuff, like trumpet and electric guitar, soemthing different like that. I know him for doing stuff that’s unorthodox. 3½ stars.

Eddie Henderson, “Dreams” (Collective Portrait, SmokeSessions, 2015) (Henderson, trumpet; Gary Bartz, alto saxophone; George Cables, Fender Rhodes piano; Doug Weiss, bass; Carl Allen, drums)

Electric keyboard. Flugelhorn? Eddie Henderson maybe? I can pick him up because he does a thing [sings ascending phrase]. And his sound is so broad. He has such a beautiful legato way of playing. It’s very broad and even. When I hear him play, I can tell he’s been around people like Clifford and Lee and all those guys who I’ve listened to. He’s got that thing in his sound. Yeah, that’s it. That’s Eddie. Doctor Strangelove. This past summer, I saw him playing with that group he’s in with David Weiss, the Cookers. They were playing some great music that day. It was very refreshing, because most of these festivals don’t have any jazz at all—hardly. This one had them playing, Ahmad—so I got to hear a little bit of something. Eddie was on fire that day, too. This is the newest? Is it young guys in the group? Oh, in his generation. Whoever the saxophone player is, the sound, the tenor…that’s a tenor? It’s not even a tenor, right? Is it a C-melody or something? It’s alto! Wow. Oh, that’s Bartz. He has that type of sound. You can’t tell what it is, tenor, alto…could be soprano. George Cables? It’s his approach to harmony mostly, and he has a way of laying out the chords that’s like a comfortable bed to lay in. I played with him a few times, and he makes it easy for you to play. Piano players like that are not a dime a dozen. People like Cables or Larry Willis, the way they accompany musicians and make them sound good. It’s hard. It’s a forgotten art, accompaniment. [You’ve got a good one.] Oh, yeah. Sully’s really on his way, man. But those are all them cats from New Orleans, man…forget it, they must feed them something. This is a new release with Eddie? Smoke Sessions, so it’s live? 5 stars, without a doubt. Eddie’s my all-time hero. Every time I see him perform I feel like it’s a special moment, and it shouldn’t be missed by any trumpet player. I always see that in his playing anyway. The rhythm is so free, so I wouldn’t have been able to tell that’s Carl—I’d have to hear him play time.

Tom Harrell, “Family” (Colors Of A Dream, High Note, 2013) (Harrell, trumpet; Esperanza Spalding, Ugonna Okegwo, bass)

Bass and trumpet, duet. Two basses? Wow. The instrumentation is interesting. That’s pretty cool. I wouldn’t think to do that. I’d probably get two drummers. Is it James Zollar? I like the sound. Whoever this is has a great sound. It’s very nice and warm. It’s a very pretty sound. Was that guy older than me, too? It’s very mature, a very mature sound, and original. But I can’t guess. 4 stars. I liked the melody. I liked the sound a lot. It’s very nice, dark, pretty. [after] Tom Harrell! Another one of my favorite players, man. I woudn’t have been able to guess that because he usually plays more stuff. I’ve always admired Tom for his brilliance and his great compositions, and the way he plays harmony and everything. He’s one of my favorite players. I should know him by his sound.

Wadada Leo Smith, “Crossing Sirat” (Spiritual Dimensions, Cuneiform, 2009) (Smith, trumpet; Vijay Iyer, piano, synthesizer; John Lindberg, bass; Pheeroan AkLaff, Don Moye, drums)

Whoa. I’m not going to know this one. [You might. Listen to the sound.] All right. Lester Bowie? Yeah, the piano player’s going for it. Out there in the ozone. Pluto. It’s definitely in the vein of Don Cherry, but it’s not him. It’s a newer recording. Is the pianist Don Pullen? No. These are all people who are still here. It’s not Geri. Jason Moran? Glasper? No, he wouldn’t do it. He’s on another thing right now. The trumpet player… Yeah! I like this! But you know what? If I tried to play this at the house, my girl would leave. She wouldn’t leave, but she would just excuse herself and go buy groceries. It’s an acquired taste. I like the expressiveness of it. I like the boldness, and the sound is very majestic. It reminds me of Lester a little bit. When I met Lester he told, “Man, stop playing all that pretty shit—take it out.” Then I started doing all kinds of crazy stuff, and he was like, “Yeah!” This was late one night in Italy. I don’t know who that is, though. Ok, who is that? Wadada Leo Smith. He’s from the AACM? I knew it was one of those guys. His name rings a bell. 5 stars. Just because I like that! I have yet to do my record like that. It’s coming, though.

Gerald Wilson Orchestra, “Detroit” (Detroit, Mack Avenue, 2009) (Kamasi Washington, tenor sax solo; Sean Jones; flugelhorn solo)

Is this is recent recording? [About six years old.] I know it’s not who it is, but this reminds me a little bit of Griff’s [Johnny Griffin] big band. He did a couple of really nice albums. It’s beautiful. That’s all I can say. I can’t place the tenor player, but it’s someone very mature. The trumpet player also is playing a lot of harmony. Beautiful sound, great range, still playing very soft but in the higher register which is real pretty. The arrangement is incredible. 5 stars, just because I like this kind of stuff—really pretty. Both were older. Definitely older. [after] What?! It’s the arrangement. Kamasi sounds like he’s a grown person. Sean I wouldn’t have been able to figure out, except only when he played the high note—but usually when I hear him, he’s more brass. That was a GOOD one. They sound grown. I’ve only heard both of them playing in different settings completely. I heard Sean playing with Marcus Miller. Kamasi comes to sit in with us whenever I’m in L.A. He’s a very exciting player. I haven’t heard him playing nothing like that, so nice and mellow. [Do you incorporate any of GW’s arrangements or charts in the big band?] We have yet to play any of his stuff. We’ve been playing my stuff, and some of the guys in the band write, too. I’ve got some outside guys, too. Dave Gibson, the trombonist, has given me a few charts. But I would be open to do that if he’d give me some of them.

Nate Wooley, “Skain’s Domain” ((Dance To) The Early Music, Clean Feed, 2015) (Wooley, trumpet; Josh Sinton, bass clarinet; Matt Moran, vibraphone; Eivind Opsvik, bass; Harris Eisenstadt, drums)

You know who does that? Enrico does that—multiphonics. This is going to be interesting. I can see that now. Oh. Wynton? Just because I hear he plays… [Hums the refrain] That’s Wynton’s thing. Oh, he wrote the song. Is it one of his disciples? It could be Marlon. I’m hearing some quarter tones. No, it’s definitely not Wynton. I take that back. Pshew, great technique. Arturo? Is that a bass clarinet in there? Jonathan Finlayson? Is it an older guy? [Younger than you.] Is this guy from New Orleans? You never cease to amaze me with your depth of musical knowledge. I hear a vibraphone, and there’s a bass clarinet, some drums. I don’t know how to give this stars, because it’s an acquired taste—not everybody will like this kind of music. I would give it a 5, just based on the creativity and also 5 on technique, dexterity. He’s definitely getting some sounds out of the trumpet that you wouldn’t normally hear people do. Just a few bars back there, there was something very airy but then also kind of a high-pitched note. It’s different. [Did you listen to Wynton’s music a lot in the ’80s?] Yeah. I really liked the Standard album he did, and I especially liked his classical records. This trumpet player isn’t from New Orleans? And he’s young.

Ambrose Akinmusire, “J.E. Milmah (Ecclesiastes 6:10)” (The Imagined Savior Is Far Easier To Paint, Blue Note, 2014) (Akinmusire, trumpet; Sam Harris, piano; Charles Altura, guitar; Harish Raghavan, bass; Justin Brown, drums)

Is it Ambrose? His sound I recognize. It’s very original. Ambrose has an original style. I can pick him out. He just makes me think about the future when I hear him play. I heard him play for the first time when he was only 12 or 13. They used to have a matinee show in Oakland where they would bring the kids out, and both him and Jon Finlayson were like a team together when they were still in school, so they would come up and sit in with us. I noticed even back then that he had his own thing going on. He has a voice. I liked that. 5 stars. I like Ambrose, man. I think he’s doing something special. He makes me think of where the music’s heading. It’s definitely like he’s reaching for something there. I can feel it. Whenever I hear him on the radio, I can tell it’s him. I like to hear him and Gerald Clayton play their original stuff. It’s real cool.

Mack Avenue 2015 Super Band, “Sudden Impact” (Live From The 2015 Detroit Jazz Festival, Mack Avenue, 2015) (Freddie Hendrix, trumpet, composer; Tia Fuller, alto saxophone; Kirk Whalum, tenor saxophone; Gary Burton, vibraphone; Christian Sands, piano; Christian McBride, bass; Carl Allen, drums)

Is there a vibraphone underneath? Is Nicholas in there? Freddie Hendrix? [That was before he even soloed.] I can tell. I know how he plays his eighth notes. He has a very nice rhythmic thing. Plus, I just saw him a couple of weeks ago. But I can tell it’s him because of the way he plays his eighth notes, the way he swings. You don’t get to hear it that often any more, where cats play time like that, play rhythm that way. So when I hear him doing this, I know it’s him, because he’s one of the few guys who still do that. Is this his record? [No, but it’s his tune.] Is the pianist Anthony Wonsey? Younger? Wow. I don’t know Christian Sands. Freddie Hendrix has been playing his ass off lately; I’ve noticed that. I like it. 4 stars.

https://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/royhargrove

ZA Do you know the story of Duke Ellington and how he started out—selling concert posters, booking bands, and then he’d do gigs at fancy supper clubs. He had a whole sideline of businesses while he was launching his own career as a bandleader. Later he copyrighted his music, which paid off because that money kept his band on the road even in the hard times. I was wondering, how much are you into the business?

RH I’m very involved. Just last year I became incorporated, and now I have a business called Hardgroove Enterprises. We’ve opened a gallery in my rehearsal space. One of the things that we’re trying to cultivate is something that’s a little bit outside the music and that’s with jazz art and photography. Currently there’s a show going on. Hopefully, in the future we’ll get some more of that along with some recitals and small concerts.

ZA Roy, why are you supporting a gallery?

RH I’m very intrigued by art and photography. Eventually, it’s going to make a profit for the business. That definitely makes me supportive of it. My vision involves more of the musical side the space—maybe doing some recording.

ZA You say you’re intrigued with art and photography. How did that develop?

RH I’ve always liked to look at jazz photographs, at pictures of the musicians from the past. When I look at paintings, what I really enjoy the most is the detail. Sometimes they can really be abstract but you can get a message.

ZA Do you have any ideas that you want to see come to fruition at the jazz Gallery?

RH Eventually I hope to have a production company so that we can send other artists out on the road in their own groups, but they’ll be affiliated with Hardgroove Enterprises. It’s very important to be aware of what is going on in the world of the business of music because there’s so many people out there who will take you for a ride, and you have to keep your eyes open.

ZA There’s a lot of people who live off music, and a lot of musicians who don’t benefit from the music they’ve created. I can’t figure it out.

RH It’s pretty sad. Once, I went into an in-store in Detroit, and the cat from my former label didn’t even know who I was. He came up to me and asked me if I knew where Roy was, and I was like, “You’re looking at him!” That was the kind of thing I was going through. Now I’m with PolyGram Verve, which is probably one of the best jazz labels in the country. The people who are on staff are very knowledgeable about the music. My product manager, and a lot of the people in the publicity department were at the Vanguard every night that I was there. And that really shows support.

ZA Also respect. What videos have you done?

RH When we were at the Vanguard, that became a video, it’s been sold to BET [Black Entertainment Television].

ZA Why don’t we see more jazz videos?

RH I couldn’t tell you. Financially, there aren’t a lot of people who will get behind a jazz artist to make a video. There’s a new artist, a cat by the name of D’Angelo, you ever run into him? Well anyway, he’s bad, really bad. You never heard of him? You got to. If he comes out with a record and makes trillions of dollars, now that record company is going to get their money back, so they’re willing to finance a video. They’re really taking a chance on a jazz artist. The world of jazz is so small…

ZA Parker’s Mood came out just in time for Charlie Parker’s birthday. It’s beautiful. He’s really admired for what he did with those tunes. I like what you did with them.

RH The conditions in which we recorded that CD were really nice. It felt like we were playing in a living room with a couch and a piano only it was soundproof. We were very comfortable. We had to learn those tunes, which was pretty hard.

ZA Everyone says that about Charlie Parker. Roy, are you interested in writing film scores?

RH Oh yeah, I’m really into doing that. I write a lot, I like writing. I think that to know yourself, you have to write. I watch movies all the time—that’s my other hobby, going to the movies. I could sit up and watch HBO all day. So I’m ready to do that.

ZA Do you have any complaints, gripes…something you wish you could change about the music industry, about the jazz life, or do you accept it pretty much?

RH Well, you have to accept it, but sometimes I wish that promoters and club owners would respect artists just a little more and stop treating us like second class citizens. Not everyone is like that, but in some cases it’s true and it’s not right, you know? We deserve better than that because we’re out here working hard to get from one gig to the next, and when you get there people treat you shabbily, it’s not really cool. That hasn’t happened to me a lot, but it has happened a couple of times and when it does, it’s very frustrating. The only thing that you can do is deal with it and go on.

ZA When you go onstage to face the public, whoever’s acting foul, stays behind the scenes.

RH Yeah, they’re behind alright. I’m like, what instrument do you play? (laughter) That’s one of the things that I would change. Just that. The other thing is that here in the United States, I think there should be more jazz venues. There are lots of musicians coming onto the scene, and yet there aren’t that many places for us to work. Overall, I don’t have many complaints. I think that it’s a blessing to he able to do what we’re doing now—for us to be playing music we love and get paid doing it.

ZA When you’re on the road, you’re always meeting great musicians. Have there been any memorable encounters lately?

RH One that comes to mind right this very moment was being on stage with Doc Cheatham and Harry “Sweets” Edison at Wolf Trap for a tribute to Louis Armstrong. That had a great effect on me because Doc Cheatham is 90 years old, and he’s still playing strong, stronger than some young guys I know who are playing trumpet. He has such a centered sound, a big sound. And he’s playing all this authentic music from the Louis Armstrong era. And you hear that, and it makes you think, I want to be like that. I want to be playing when I’m 90-something years old—strong like that. And even Sweets, he’s still got all that fire and energy that he’s had for years. So that’s inspiring. Another thing that comes to mind is the Sonny Rollins concert a couple of years ago at Carnegie Hall. That was one of the highlights of my career. I’ll always remember it. Sonny, he’s so unpredictable. When he stumps off a tune, you don’t know what you’re going to do from there. I just watched him. We started trading and got into some really exciting exchanges there.

ZA He’s 65, but from what you’re saying his age is a blessing too.

RH Music is like wine—it gets better as you get older,

ZA Are you getting better?

RH Yeah!

ZA So what’s in the can? I heard you recorded for days last trip to the studio.

RH We recorded 45 tunes. There’s nothing that’s not usable.

ZA How much writing did you do?

RH Umm, I wrote about seven or eight tunes. Most of my tunes went on Family, but there are a couple of others.

ZA When we hear Louis Armstrong or see a film of him performing, he was such a strong performer, a virtuoso. What does Louis Armstrong mean to you?

RH Louis Armstrong’s spirit is within me, within all of us. If you play the trumpet, you had to have dealt with Louis Armstrong at some point. When I listen to him or see him in film, it’s always inspiring to me because he has such a beautiful spirit. For me, Louis Armstrong is an example of what I was talking about. When you’re having a good time playing music, people can feel it and that’s the reason why I think his music was accepted so widely—because it’s happy music. People gave him a hard time because he was always smiling, but that’s just part of the musician’s world. Some people carry that whole cynical thing too far, people are just negative sometimes. They don’t have anything better to do than talk bad about some musicians. That’s part of that world. It reminds me of how I hear people talk about Wynton. A few musicians always have something wrong to say about him. Maybe they resent his success. As a musician, he’s very good.

ZA What about Clifford Brown?

RH Clifford was the first cat I heard in high school. My principal was a trumpeter and he was listening to Clifford Brown. One day he pulled me out of my algebra class and I just knew I had done something wrong, that I was in trouble. He said, man, sit down, and played me three of Clifford’s recordings. One was an EmArcy recording. The other was Sonny Rollins — Sonny Rollins Plus 4 which included Clifford Brown and Max Roach. After we heard them, he said, Here, these are yours. And that was the beginning of my experience listening to acoustic jazz. After Clifford, I checked out Freddie Hubbard and then I listened to Lee Morgan and Kenny Dorham and Roy Eldridge and all these other cats I didn’t even know were around. As a result of hearing Clifford Brown, my interest sparked to the point that I wanted to hear more.

ZA Who among the contemporary trumpeters are you fond of?

RH Freddie has always been my biggest influence. Freddie Hubbard! When I heard him it really just opened me up. He has a sound that reaches back to people like Clifford Brown, Bird and Coltrane, but he can still turn around and play contemporary… The first recording I heard of his was a thing called The Hub of Hubbard. There was one side where he plays one song for 20 minutes and then he plays this beautiful ballad called “The Things we Did Last Summer.” When I heard that I said, “Oh man, that’s the way I wanted to play.” I started learning all of his licks and stuff. (laughter)