SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2019

VOLUME SEVEN NUMBER TWO

HOLLAND DOZIER HOLLAND

(L-R: Lamont Dozier, Eddie Holland, Brian Holland)

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

SHIRLEY SCOTT

(June 15-21)

FREDDIE HUBBARD

(June 22-28)

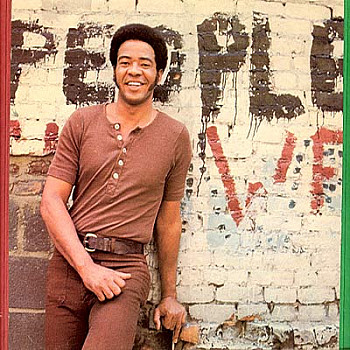

BILL WITHERS

(June 29- July 5)

OUTKAST

(July 6-12)

J. J. JOHNSON

(July 13-19)

JIMMY SMITH

(July 20-26)

JACKIE WILSON

(July 27-August 2)

LITTLE RICHARD

(August 3-9)

KENNY BARRON

(August 10-16)

BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON

(August 17-23)

MOS DEF

(August 24-30)

BLIND BOY FULLER

(August 31-September 6)

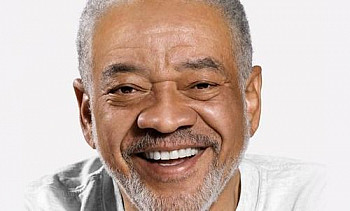

Songwriter/singer/guitarist Bill Withers is best remembered for the classic "Lean on Me" and his other million-selling singles "Ain't No Sunshine" and "Use Me," but he has a sizable cache of great songs to his credit. Al Jarreau recorded an entire CD of Withers' songs on Tribute to Bill Withers (Culture Press 1998). His popular radio-aired LP track from Still Bill, "Who Is He? (And What Is He to You?)," was a 1974 R&B hit for Creative Source.

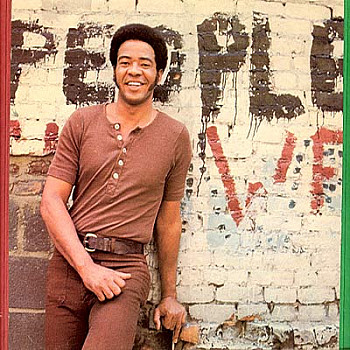

Born July 4, 1938, in Slab Fork, WV, Withers was the youngest of six children. His father died when he was a child and he was raised by his mother and grandmother. After a nine-year stint in the Navy, Withers moved to Los Angeles to pursue a music career in 1967. He recorded demos at night while working at the Boeing aircraft company where he made toilet seats. His recording career began after being introduced to Clarence Avant, president of Sussex Records.

Stax Records stalwart Booker T. Jones produced his debut album, Just As I Am (with some co-production by Al Jackson, Jr.), which included his first charting single, "Ain't No Sunshine" that went gold and made it to number six R&B and number three pop in summer 1971 and won a Grammy as Best R&B Song. Its follow-up, "Grandma Hands," peaked at number 18 R&B in fall 1971. The song was later covered by the Staple Singers and received airplay as a track from their 1973 Stax LP Be What You Are. "Just As I Am" featured lead guitar by Stephen Stills and hit number five R&B in summer 1971.

Withers wrote "Lean on Me" based on his experiences growing up in a West Virginia coal mining town. Times were hard and when a neighbor needed something beyond their means, the rest of the community would chip in and help. He came up with the chord progression while noodling around on his new Wurlitzer electric piano. The sound of the chords reminded Withers of the hymns that he heard at church while he was growing up. On the session for "Lean on Me," members of the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band ("Express Yourself," "Loveland") were used: drummer James Gadson, keyboardist Ray Jackson, guitarist Benorce Blackman (co-wrote with Withers "The Best You Can" from Making Music), and bassist Melvin Dunlop. His second gold single, "Lean on Me," landed at number one R&B and number one pop for three weeks on Billboard's charts in summer 1972. It was included on his Still Bill album which went gold, holding the number one R&B spot for six weeks and hitting number four pop in spring 1972. "Lean on Me" has became a standard with hit covers by U.K. rock band Mud and Club Nouveau. "Lean on Me" was also the title theme of a 1989 movie starring Morgan Freeman. Still Bill also included "Use Me" (gold, number two R&B for two weeks and number two pop for two weeks in fall 1972) .

Withers' Sussex catalog also included Bill Withers Live at Carnegie Hall, 'Justments, and The Best of Bill Withers. Withers contributed "Better Days" to the soundtrack of the Bill Cosby 1971 western Man And Boy, released on Sussex. There was a duet single with Bobby Womack on United Artists, "It's All Over Now," from summer 1975.

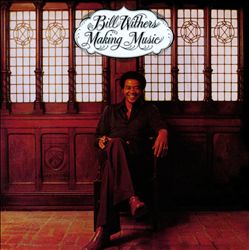

After a legal battle with Sussex, Withers signed with Columbia Records. Columbia later bought his Sussex masters when the label went out of business. Withers was briefly married actress Denise Nicholas (ABC-TV's Room 222 and the 1972 horror film Blacula) in the early '70s. His releases on Columbia were Making Music ("Make Love to Your Mind," number ten R&B), which hit number seven R&B in late 1975; Naked and Warm; Menagerie ("Lovely Day," a number six R&B hit), which went gold in 1977; and 'Bout Love from spring 1979. Teaming with Elektra Records artist Grover Washington, Jr., Withers sang the crystalline ballad "Just the Two of Us," written by Withers, Ralph MacDonald, and William Salter. It went to number three R&B and held the number two pop spot for three weeks in early 1981. "Just the Two of Us" was redone with hilarious effect in the Mike Myers movie Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, released in summer 1999. Withers teamed with MacDonald for MacDonald's Polydor single "In the Name of Love" in summer 1984.

Withers' last charting LP was Watching You, Watching Me in spring 1985. He occasionally did dates with Grover Washington, Jr. during the '90s. His songs and recordings have been used as both the source of numerous covers (Aaron Neville's "Use Me") and sampled by a multitude of hip-hop/rap groups. Withers resurfaced in the 21st century, playing concerts, and having his albums reissued in various countries. He is also the subject of the 2010 bio-documentary Still Bill, by filmmakers Damani Baker and Alex Vlack.

In 1970, the singer was a guy in his thirties with a job and a

lunch pail. Then he wrote ‘Ain’t No Sunshine,’ and things got

complicated

As the Grammy telecast begins, and AC/DC kick off the show, Withers

jumps into his Lexus SUV and heads down to his favorite restaurant, Le

Petit Four; he has a hankering for liver and onions but settles for the

blackened catfish. The hostess knows him by name, but otherwise he

blends into the crowd. “I grew up in the age of Barbra Streisand, Aretha

Franklin, Nancy Wilson,” he says, still musing on the Grammys. “It was a

time where a fat, ugly broad that could sing had value. Now everything

is about image. It’s not poetry. This just isn’t my time.”

Withers has been out of the spotlight for so many years that some people think he passed away. “Sometimes I wake up and I wonder myself,” he says with a hearty chuckle. “A very famous minister actually called me to find out whether I was dead or not. I said to him, ‘Let me check.’"

Others don’t believe he is who he says: “One Sunday morning I was at Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles. These church ladies were sitting in the booth next to mine. They were talking about this Bill Withers song they sang in church that morning. I got up on my elbow, leaned into their booth and said, ‘Ladies, it’s odd you should mention that because I’m Bill Withers.’ This lady said, ‘You ain’t no Bill Withers. You’re too light-skinned to be Bill Withers!’ ”

His career lasted eight years by his own count; in that time, he wrote and recorded some of the most loved, most covered songs of all time, particularly “Lean on Me” and “Ain’t No Sunshine” — tunes that feature dead-simple, soulful instrumentation and pure melodies that haven’t aged a second. “He’s the last African-American Everyman,” says Questlove. “Jordan’s vertical jump has to be higher than everyone. Michael Jackson has to defy gravity. On the other side of the coin, we’re often viewed as primitive animals. We rarely land in the middle. Bill Withers is the closest thing black people have to a Bruce Springsteen.”

Withers was stunned when he learned he had been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year. “I see it as an award of attrition,” he says. “What few songs I wrote during my brief career, there ain’t a genre that somebody didn’t record them in. I’m not a virtuoso, but I was able to write songs that people could identify with. I don’t think I’ve done bad for a guy from Slab Fork, West Virginia.”

Withers’ hometown is in a poor rural area in one of the poorest states in the Union. His father, who worked in the coal mines, died when Bill was 13. “We lived right on the border of the black and white neighborhood,” he says. “I heard guys playing country music, and in church I heard gospel. There was music everywhere.”

The youngest of six children, Withers was born with a stutter and had a hard time fitting in. “When you stutter, people have a tendency to disregard you,” he says. That was compounded by the unvarnished Jim Crow racism that was a way of life in his youth. “One of the first things I learned, when I was around four, was that if you make a mistake and go into a white women’s bathroom, they’re going to kill your father.” He was a teenager when Emmett Till, a 14-year-old from Chicago who allegedly whistled at a white woman while visiting relatives in Mississippi, was beaten to death by two men who were cleared of all charges by an all-white jury. “[Till] was right around my age,” says Withers. “I thought, ‘Didn’t he know better?’ ”

Desperate to get out of Slab Fork, he enlisted in the Navy right after graduating from high school in 1956. Harry Truman had desegregated the armed forces eight years earlier, but Withers quickly discovered that didn’t mean much at his first naval base, in Pensacola, Florida. “My first goal was, I didn’t want to be a cook or a steward,” he says. “So I went to aircraft-mechanic school. I still had to prove to people that thought I was genetically inferior that I wasn’t too stupid to drain the oil out of an airplane.”

By the time he was transferred to California in the mid-1960s, he realized he’d never have the courage to quit the Navy if he couldn’t rid himself of his stutter. “I couldn’t get out a word,” he says. “I realized it wasn’t physical. I figured out that my stutter — and this isn’t the case for everyone — was caused by fear of the perception of the listener. I had a much higher opinion of everyone else than I did of myself. I started doing things like imagining everybody naked — all kinds of tricks I used on myself.”

Against all conventional wisdom, it worked (though he still trips over the occasional word), and in 1965 he quit the Navy and became “the first black milkman in Santa Clara County, California.” He eventually took a job at an aircraft parts factory. As a Navy aircraft mechanic, he was ridiculously overqualified, but “it was all about survival.”

One night around that time, he visited a club in Oakland where Lou Rawls was playing. “He was late, and the manager was pacing back and forth,” says Withers. “I remember him saying, ‘I’m paying this guy $2,000 a week and he can’t show up on time.’ I was making $3 an hour, looking for friendly women, but nobody found me interesting. Then Rawls walked in, and all these women are talking to him.”

Withers was in his late twenties. His music-business experience consisted of sitting in a couple of times with a bar band while stationed in Guam in the Navy. He’d never played the guitar, but he headed to a pawn shop, bought a cheap one and began teaching himself to play. Between shifts at the factory, he began writing his own tunes. “I figured out that you didn’t need to be a virtuoso to accompany yourself,” he says.

He began saving from each paycheck until he had enough to record a crude demo. Withers shopped it around to major labels, which weren’t interested, but then he got a meeting with Clarence Avant, a black music executive who had recently founded the indie label Sussex and had just signed the songwriter Rodriguez (of Searching for Sugar Man fame). “[Withers’] songs were unbelievable,” Avant remembers. “You just had to listen to his lyrics. I gave him a deal and set him up with Booker T. Jones to produce his album.”

Jones, the famous Stax keyboardist, went through his Rolodex and

hired the cream of the Los Angeles scene: drummer Jim Keltner, MGs

bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, Stephen Stills on guitar. “Bill came right

from the factory and showed up in his old brogans and his old clunk of a

car with a notebook full of songs,” says Jones. “When he saw everyone

in the studio, he asked to speak to me privately and said, ‘Booker, who

is going to sing these songs?’ I said, ‘You are, Bill.’ He was expecting

some other vocalist to show up.”

Jones, the famous Stax keyboardist, went through his Rolodex and

hired the cream of the Los Angeles scene: drummer Jim Keltner, MGs

bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, Stephen Stills on guitar. “Bill came right

from the factory and showed up in his old brogans and his old clunk of a

car with a notebook full of songs,” says Jones. “When he saw everyone

in the studio, he asked to speak to me privately and said, ‘Booker, who

is going to sing these songs?’ I said, ‘You are, Bill.’ He was expecting

some other vocalist to show up.”

Withers was extremely uneasy until Graham Nash walked into the studio. “He sat down in front of me and said, ‘You don’t know how good you are,’ ” Withers says. “I’ll never forget it.” They laid down the basic tracks for what became 1971’s Just As I Am in a few days. (One of the songs was inspired by the 1962 Jack Lemmon-Lee Remick movie Days of Wine and Roses; Withers was watching it on TV, and the doomed relationship at the film’s center brought to mind a phrase: “Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone.”)

The album’s cover photo was taken during Withers’ lunch break at the factory; you can see him holding his lunch pail. “My co-workers were making fun of me,” he says. “They thought it was a joke.” Still unconvinced that music would pay off, he held on to his day job until he was laid off in the months before the album’s release. Then, one day, “two letters came in the mail. One was asking me to come back to my job. The other was inviting me on to Johnny Carson.” The Tonight Show appearance, in November 1971, helped propel “Ain’t No Sunshine” into the Top 10, and the follow-up, “Grandma’s Hands,” reached Number 42.

By then, Withers was 32; he still marvels at the fact that he was able to come out of nowhere at that relatively advanced age. “Imagine 40,000 people at a stadium watching a football game,” he says. “About 10,000 of them think they can play quarterback. Three of them probably could. I guess I was one of those three.”

He took some earnings, bought a piano and, again, with no training, began fiddling around. One of the first things he came up with was a simple chord progression: “I didn’t change fingers. I just went one, two, three, four, up and down the piano. It was the first thing I learned to play. Even a tiny child can play that.”

Tired of love songs, he wrote a simple ode to friendship called “Lean on Me.” Withers didn’t think much of it. “But the guys at the record company thought it was a single,” he says. It became the centerpiece of his second album, 1972’s Still Bill. The song rocketed to Number One and was inescapable for the entire year.

Withers was now a hot commodity, appearing on Soul Train and the BBC, and headlining a show at Carnegie Hall that was released as a live album. But he refused to hire a manager, insisting on overseeing every aspect of his career, from producing his own songs to writing the liner notes to designing his album covers. “He was so opinionated,” says Avant. “I was the closest thing he had to a manager. Everybody was scared of him.”

“Early on, I had a manager for a couple of months, and it felt like getting a gasoline enema,” says Withers. “Nobody had my interest at heart. I felt like a pawn. I like being my own man.”

In 1973, Withers married Denise Nicholas, a star of the TV show Room 222. It was a rocky relationship from the start. “Their wedding day was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen,” Avant says. “I remember her semi-crying. She said, ‘He doesn’t love me.’ I said, ‘Bill, what are you doing getting married?’ He said, ‘I want everyone back home to know I’m marrying one of these Hollywood actresses.’ ” Withers and Nicholas had terrible fights, which soon began getting coverage in magazines like Jet; the couple split after little more than a year. Withers poured all of his pain from the breakup into his 1974 LP +’Justments. “It was like a diary,” says Questlove. “That album was a pre-reality-show look at his life. Keep in mind this was years before Marvin Gaye did it with Here, My Dear.“

Withers was also unhappy on the road. Despite having enormous radio hits, he found himself opening up for incongruous acts like Jethro Tull and making less money than he felt he deserved. Things got worse when Sussex went bankrupt in 1975, and Withers signed a five-record deal with Columbia. “I met my A&R guy, and the first thing he said to me was, ‘I don’t like your music or any black music, period,’ ” says Withers. “I am proud of myself because I did not hit him. I met another executive who was looking at a photo of the Four Tops in a magazine. He actually said to me, ‘Look at these ugly niggers.’ ”

At Sussex, he had complete creative control over his music, but at Columbia he found himself in the middle of a large corporation that was second-guessing his moves. As he relives this part of his past, he gets teary. “There were no black executives,” he says. “They’d say shit to me like, ‘Why are there no horns on the song?’ ‘Why is this intro so long?’ . . . This one guy at Columbia, Mickey Eichner, was a huge pain in the ass,” he adds. “He told me to cover Elvis Presley’s ‘In the Ghetto.’ I’m a songwriter! That would be like buying a bartender a drink.”

Eichner, who was the head of Columbia’s A&R department, says he’s “hurt” by Withers’ words, and he has a different recollection of events. “He submitted a rec-ord, and we didn’t hear a single,” he says. “I suggested he maybe do an Elvis cover. He’s very stubborn. I believe that a manager would have understood what I was trying to do, but he didn’t have one, so there was nobody I could reason with.” As far as racism at Columbia, Eichner says he doesn’t recall “hearing or seeing anything.”

With the exception of 1977’s Menagerie (which contains the funky classic “Lovely Day”), none of the Columbia albums reached the Top 40. Withers’ 1980 hit “Just the Two of Us” was a duet with Grover Washington Jr. on Elektra – “That was a ‘kiss my ass’ song to Columbia,” says Withers. The low point came during the sessions for his last album, 1985’s Watching You Watching Me. “They made me record that album at some guy’s home studio,” he says. “This stark-naked five-year-old girl was running around the house, and they said to her, ‘We’re busy. Go play with Bill.’ Now, I’m this big black guy and they’re sending a little naked white girl over to play with me! I said, ‘I gotta get out of here. I can’t take this shit!’ ”

Withers hasn’t released a note of music since then, aside from a guest spot on a 2004 Jimmy Buffett song; he has not performed publicly in concert in nearly 25 years. Right now he’s sitting at his kitchen table reading a political blog on his iPad, as CNN runs quietly on a nearby TV. He watches a lot of television, and he especially loves Mike & Molly, The Big Bang Theory and the MSNBC prison documentary series Lockup. “I really have no idea what he does all day,” says his wife, Marcia. “But he does a lot on his iPad. He always knows exactly what’s going on in the world. Whenever I mention anything, he says, ‘Oh, that’s old news.’ ”

Marcia, who met Withers in 1976, runs his publishing company from a tiny office on Sunset Boulevard. “We’re a mom-and-pop shop,” he says. “She’s my only overseer. I’m lucky I married a woman with an MBA.” Since Withers was the sole writer of most of his material, he gets half of every dollar his catalog generates – and “Lean on Me” alone has appeared in innumerable TV shows, movies and commercials. Any licensee that wants to use Withers’ master version of one of his songs needs his approval. “If it’s for a scene in a show where somebody is killed or something, we will turn them down,” says Marcia. “We don’t want people to associate, say, ‘Lean on Me’ with violence.” Technically, it’s possible to license a cover of one of his songs without his consent. “But that’s never happened,” he says. “They don’t want to piss me off.”

Bill and Marcia have invested wisely in L.A. real estate. For the past 17 years, they’ve lived in their 5,000-square-foot house, which has three stories and an elevator and is furnished with pricey-looking African art; they bought the home for $700,000 in 1998, and it’s now worth many times that. It’s crammed with books and mementos from Withers’ career, including a 1974 photo of him with Muhammad Ali. There’s an exercise room on the third floor with several machines, which all look brand-new.

Their children, Todd and Kori, are both in their thirties and live nearby. Bill was an active father after he left the music biz, and he’s very close to them. “We’d have James Brown dance parties in our pajamas,” says Kori, “and take cross-country road trips, blasting Chuck Berry songs the whole time.” Withers also occupied himself with construction projects at his investment properties. (“When I moved to New York for college, he built a wall in the middle of my apartment with a door on it,” says Kori. “He’s always building something.”)

The Withers house also has a recording studio, but Bill has little interest in making new music. “I need a motivator or something to goose me up,” he says. “They need to come out with a Viagra-like pill for folks my age to regenerate that need to show off. But back where I’m from, people sit on their porch all day.”

He’s turned down more offers for comeback tours than he can count. “What else do I need to buy?” he says. “I’m just so fortunate. I’ve got a nice wife, man, who treats me like gold. I don’t deserve her. My wife dotes on me. I’m very pleased with my life how it is. This business came to me in my thirties. I was socialized as a regular guy. I never felt like I owned it or it owned me.”

He hasn’t ruled out a performance at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in April, though. “There are things that will decide that for me,” he says, mysteriously. Says Marcia, “I know he doesn’t like how older people sound when they sing. I don’t push him. People say that I enable him, but he’s just over it. “

In the meantime, Questlove is determined to get him back to work. “I started my campaign to produce a Bill Withers album back in 2004,” he says. “My first audition was to produce an Al Green album. I figured Bill would see it, love it and agree to record with me. He said, ‘Nope, I’m fine. I don’t want to sing.’ So I made an album with his friend Booker T. Jones, but same thing. Finally I recorded Withers’ ‘I Can’t Write Left Handed’ with John Legend. He still said, ‘Nope.’ ”

The Legend-Roots album with “Left Handed” won three Grammys, but Withers was unimpressed. “I won’t give up,” says Questlove. “He’s my hero.”

Posted by

Eddie "STATS"

4 years ago

Posted by

Eddie "STATS"

4 years ago

For students of soul, Bill Withers–as Questlove so aptly put it–is our Everyman. An airplane mechanic who never played an instrument until he picked up a guitar and decided to teach himself songwriting–and wrote “Ain’t No Sunshine” on on of his first demos out–Withers also never quit his day-job, even after it was clear he had a hit and a record deal on his hands. More hits followed–“Lean On Me”; “Grandma’s Hands”; “Use Me”; “Lovely Day”; “Just The Two of Us,” just to name a few. But after a decade or two of label politics and A&Rs trying to tell him what to sing, Withers famously walked away from it all…yet still managed to live comfortably by retaining control of his own catalog. In addition to gifting us with an inspiring discography of composition; as close to unmediated personal expression as the entertainment biz could handle, his career stands equally as testament to the ideal of craft over industry, of self-determination over the trappings of fame.

A series of retrospective recognitions of Withers’ achievements–beginning with his recent induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, continuing with his ‘Master Class’ lecture at ASCAP’s EXPO 2015 (watch his onstage interview with Aloe Blacc here) and culminating this Thursday, October 1st with a Carnegie Hall Tribute to his music, featuring the likes ofD’Angelo,(having sadly removed himself from the evening’s proceedings due to illness) Michael McDonald, Anthony Hamilton and Ed Sheeran and

brought to you in part by Okayplayer!–have pulled the reclusive star

into the spotlight again this year.

The Carnegie Hall tribute in particular, recreates Withers’ iconic 1972 concert in the legendary performance space–an immortal moment in live music and a highlight in a performing career that also including stops in Kinshasa to join James Brown, BB King, Miriam Makeba, Celia Cruz and a few others onstage at the Zaire ’74 concert that accompanied Muhammad Ali’s epic Rumble In The Jungle with George Foreman. Taking advantage of this brief window of press availability, Okayplayer managed to jump on the phone with a mellow, effusive but ever-grounded Withers and pick the troubador’s thoughts on songwriting, sampling and some of the standout moments from those classic concerts–as well as sussing out his chances of ever recording again, preferably with Questlove at the helm, please and thank you. Read on for Bill Withers’ definitive Okayplayer Interview:

OKP: Thanks for taking the time to speak with us. Have you been doing a lot of these?

BW: No.

OKP: I know you’re not a big interview guy, but I with the Carnegie Hall tribute coming up figured they’d probably be pressing you for a few.

BW: Oh, I do interviews, it’s just that nobody wants to talk to me. I’m not that interesting.

OKP: I beg to differ, we’re very interested! For one thing, I’m interested to know what your perspective is, on this whole Carnegie Hall event…

BW: Well, it’s kind of nice, huh? That people would do that. There are going to be some young people that are probably the age of my kids coming over there to hear my songs, that’s nice.

OKP: Were you familiar with most of the artists that were selected for the bill?

BW: Of course. If I wasn’t, I wouldn’t tell you [laughs]. Yeah, most of them I’ve had personal interactions with.

OKP: I was going to ask you if there are people amongst that generation who are either recording now or just coming up, that you’ve felt were carrying the torch, so to speak, of the music that you pioneered?

BW:Yeah, you know. They’re very nice people, and nice of them to do that. I’m surprised they even know who I am.

OKP: Well, you shouldn’t be. You must be aware that a whole generation has been very influenced by your songs; they’re certainly some of the most covered and sampled songs in the world. Which makes me wonder–as an artist who’s always written for yourself, avoided covering others–how do you feel about being covered, yourself? When you wrote songs, did you think about other people performing them and playing them?

BW: No. When I was writing them, I was just trying to finish them. It’s not an easy thing to do. I like the poetry of songs, you know. So I tend to lean toward songs that have some kind of poetic effect. There are a gazillion kinds of music, there’s rock music and dance music and whatever. I just happened to like the poetry of it. It’s challenging to be able to say something reasonably profound in a three minute time limit, you know? You could sit down and write an article and use sentences and stuff, but songs are different—they have the added burden of having to rhyme. It’s an interesting endeavor.

OKP:I think the emphasis on the poetry and lyrics is probably what made the core of your songs so appealing for people to cover or sample over the years. I know you’re pretty active in the publishing process of your music—have there been covers or samples that you didn’t want to approve? That weren’t doing justice to the song and the way you wrote it?

BW: Yeah, there are some things that I haven’t approved. My wife basically does that, and she’ll run it by me. It’s like anything else.

OKP: Part of the reason I ask is I’m from the generation that knew “Lean On Me” from the Club Nouveau cover, and even “Lovely Day”—there was a UK group (S.O.U.L. S.Y.S.T.E.M.) that remixed it, and introduced that music to a whole new generation. How do you feel about that kind of remixing and sampling, as far as that goes?

BW: Well, it depends on the sample. Sometimes you have to go at them, because they do it and they don’t credit you. That can be annoying, and there’s always something going on, somebody trying to get away with that. But it’s flattery, when people pick something. They got a lot of mileage out of the “No Diggity” sample and other staples, so yeah that’s fun and flattering. And this is the music business, you know.

OKP: In terms of hearing your music played back by other people, and reinterpreted. DO you have favorite songs of your own? I know some artists don’t like to hear their own voice on tape or to listen to someone else play their music, but how do you feel about hearing your own music in somebody else’s hands?

BW: Well, I don’t sit around listening to that stuff, you know. By the time you finish recording it, believe me, you’ve heard it over and over and over again. Especially if you’re your own producer, like I’ve been. You don’t let it go until you’re reasonably satisfied with it, so I don’t have any special feelings with that. Plus, it’s been a long time and I’m used to it by now. You know, it’s like your grandfather looking at your grandmother naked. He’s seen it a lot. [laughs] That’s a great analogy.

OKP: But aren’t there times when your grandfather looked at your grandmother naked and feels that old feeling again?

BW: Of course—that’s how she got to be your grandmother! When something is right for you, it doesn’t lose its appeal. I think that’s why you were mentioning longevity in songs, I think the ones that last are the ones that don’t lose their appeal. There are some huge songs in a certain period, but you never hear them again. They’ve served their purpose for that period.

There are a lot of beautiful women in the world—why do you stop at one? Who knows….

OKP: I know you walked away from the recording side of the music business. Do you still play and write music for yourself?

BW: Yeah, if I wanted to. I mean, I’ve written for other people. I’ve written for Jimmy Buffet. His album ‘When They Built the Statues,’—for Bill Russell in Boston, he asked me to write something. I don’t think songwriting is something you do, I think it’s the way you are. So just because something’s not organized and put into the system doesn’t mean you stop thinking or feeling or whatever you use. I don’t think you can turn that process off, unless you die or get some serious dementia. And even through dementia, people—you notice Glen Campbell can still play?

OKP: They say music can actually help people recover from things that affect your cognitive understanding—music can be a powerful thing for healing.

BW: Well, I don’t know too many people who have recovered, but it can help you sustain yourself.

OKP: Right. It’s good for your mental health. Are you a person who, when you’re relaxing, has a guitar close at hand? Or is it more about when you feel the occasion is right to go write a song?

BW: You know, it’s funny you brought that up. I just realized the other day—I don’t think I’ve picked one up in a couple of years. It’s hanging on the wall right by my desk. I need to go over and pick that up.

OKP: I’m glad I put that on your to-do list…

BW: I think my wife bought a guitar on eBay and asked me to tune it, so one day I’ll pick it up and tune it. But different things happen in different times in your life. I’m 77 years old, you know. The things I do now would probably be more common to people of that age group. I would like to run and jump and roll over and stuff like that, but I don’t want to hurt myself.

OKP: I don’t know if you know, but the press outlet that I write for was founded by Questlove, who you probably know is a big fan of yours…

BW: Oh, my man! He’s always been very nice to me, he’s overly nice to me. I like him. He’s just been very generous and very kind to me.

OKP: I think he’s holding out hope that you guys might record together one day…do you think he’s got a shot?

BW: I don’t know, man. My wife could get pregnant next month, I don’t know. A lot of stuff happens. I have no idea, you know.

OKP: Anything could happen?

BW: Yeah. It’s easier to plan things at his age than it is at mine!

OKP: Since we’re looking forward to the Carnegie Hall tribute, I got to thinking about some of you other live highlights. The whole Zaire ’74 concert is such an iconic moment, and I’ve never heard your perspective of your own experience meeting Muhammad Ali and being there for that whole event. Do you have particular memories that stand out from that trip?

BW: Well, I already had met him [Ali] before the trip, you know. I had known him and he had always been a nice, fun guy. It was interesting because you had a lot of characters, you had Don King—and nobody had ever heard of Don King before then. He’s got a very colorful background, you know. And then it was interesting watching people that normally wouldn’t be in that proximity to each other. You had Norman Mailer, BB King and James Brown, you know. They normally wouldn’t be in the same space, but since we’re all staying at the same hotel, there was an interesting interaction there that normal wouldn’t take place. Because these people wouldn’t have access to each other, you know.

And then there was just the fact of where we were, you know. Everybody was forced to interact with each other because we’re all staying in this one hotel, we were on a continent that nobody knew a lot about. It was just an all-around interesting trip. I don’t think that’ll ever happen again, that that many different kinds of people will be assembled in one place for that long. What does that say about the magic of Muhammad Ali? Nobody else that I know of in history has been able to gather those many different kinds of people around. George was there too, but let’s face it, it was about Ali and his charisma and magic. What’s the likelihood of somebody like Don King putting it together?

There was a lot of once-in-a-lifetime stuff. I remember standing at the middle of the place at rehearsal in the middle of the night and there were jazz guys like The Crusaders, there was James Brown, The Pointer Sisters, all kinds of people, and they had people like Stokely Carmichael just hanging out. That was the fun part of it. Two guys fighting each other in the middle of the night—I’ve been seeing that all my life. But the interesting thing was the theater around it…I didn’t stay for the fight, because it got postponed. For me the experience was over anyway, because the interesting thing was the atmosphere around it. All those things.

OKP: Was that your first time on the continent of Africa?

BW: Yep, that was my first time.

OKP: Were you able to get out of the hotel and see some of Zaire? I imagine, politically, it might have been tightly stage-managed as well, because of the high-profile nature of it.

BW: I walked around a little bit, you know. I’m an old sailor, I spent nine years in the navy. I know how to get around places that are interesting to me. I was walking around in foreign countries when I was eighteen years old. There were things that were interesting—curiosity got me out and about. It’s not like I could rent a car and start driving around.

OKP: Was there anything that struck you from those impressions of Zaire, outside the circle of the event that was happening?

BW: No, it was just another place with some other people. It was no different than being in any of the other places I had been. It was just checking out a different place with different people. And plus, you’d have to live there in order to get the full impact of the place. They know who you are and why you’re there, so there’s a festiveness around it and a certain business around it, so it’s like…I don’t think you could get the full force of the Philippines living on a navy base.

There’s a certain amount you can get out of just osmosis, but you’d have to live there and speak the language. Somebody once said “you’re as many people as languages you speak.” Most people over there spoke French, and I don’t, so there was a certain “broken language communication,” let’s put it that way. It was one more place that I had been on a long list of places. I had been traveling since I was in the navy.

OKP: It sounds like, of all those places, that LA feels like home these days? When people ask where you’re from, you say LA?

BW: I’m from a lot of places. I’m from as many places as I’ve been. I live here because it works for me. It fits. I couldn’t live in the bayou or somewhere, because they don’t do what I do down there. It’d be pretty hard to run a publishing company from an alligator swamp.

OKP: That reminds me of another question—I know that you started out with Sussex Records and you must have signed around the same that that an artist named Rodriguez was signed with them?

BW: Right.

OKP: Who’s become kind of a legend for the way that he disappeared and reappeared. Did you guys ever have any interaction while you were signed at Sussex?

BW: Briefly, you know. I think when we played in Detroit, I saw him once. But it wasn’t like we had a relationship or anything. You probably know more about Rodriguez than I do. It was like ships passing in the night. That’s an interesting story—I saw the movie like you did, and it’s interesting that something like that could be that big in South Africa and not leak out to the rest of the world.

That says more about South Africa than it does Rodriguez. What kind of place must have that been, that something could become that huge in the country, and yet be so isolated that it didn’t leak? I think in Australia, it took hold a little bit. But there’s a lot of stories in that Rodriguez saga, a lot of stories. And that it would happen in a bizarre place like South Africa.

OKP: I’m going to leave you with one more question, I know I’m pushing the limit of my time but I’m also curious…

BW: Well you’re getting the Questlove bonus here. But I’ve got to go pee, so…

OKP: I’ll try to make it quick. I know that in the phase of your career, after you were at Sussex and not dealing with Columbia any longer, you collaborated a lot with a lot of jazz and fusion artists—Grover Washington, Jr….Ralph MacDonald, who have also been a big influence on our generation. Did you find that at that phase of your career you were more interested in the kind of back-and-forth collaboration than straightforward storytelling?

BW: No, it was just some guys I knew, and we hung out together a couple times. You’re talking about “Just the Two of Us”?

OKP: “Just the Two of Us,” and there was “Soul Shadows” with The Crusaders…

BW: Yeah. Well these are guys that called up and said “Would you like to do something?” And sometimes we did and sometimes we didn’t. So those are just things that happened just from being guys. If you’re in the environment, you bump into each other. I also did some stuff with Jimmy Buffet.

OKP: Was he also a personal friend that you just bumped into?

BW: I met him through Ralph. I actually had two songs on a number one country album that Jimmy Buffet had, how about that? You were talking about my jazz connection, but you didn’t mention my country thing.

OKP: I just didn’t get to that yet!

BW:Well you better get to it, ’cause I told you I have to pee. I can’t hold it all day, brother.

OKP: Okay, last last question—what would it take for you to have that kind of experience at this point in your life? To start a new collaboration and get in the studio again? You did say “Anything can happen” so…what would it take?

BW: I don’t know. Probably the same thing—something would have to make my socks roll up and down. One thing that would help is if I could be half my age. Everything is not up to you, your personal decision. Biology and chronology—a lot of things have to do with that. Everything is not totally up to you. If it was, I’d be going around flirting with 20-year old girls at the moment. Certain things are not practical at certain times, no matter how much you want them to be. I always laugh when I see women my age in low cut dresses. That cleavage has used up its usefulness, as an enticer. So cover yourself, sweetie.

OKP: You mentioned that you’ve traveled a lot of places and had the opportunity to be at a lot of amazing moments. Do you have a bucket list or any regrets about things you’ve left undone?

BW:I try to remember my pleasures and forget my nightmares. It’s not convenient to remember anything but the experiences that were most beneficial to you. I’m not always successful at it, but one of the convenient things about being this age is when people ask you stuff you don’t want to talk about, you just tell them you don’t remember.

Probably the most common answer to all the questions you can ask someone is “I really don’t care.” There should be some privileges with growing old, and part of the privilege of growing old is you don’t have to explain everything. My life is pretty much out there–people can look at it and draw their own conclusions. And some of the rumors are nice, they make you seem interesting.

https://www.songfacts.com/blog/interviews/bill-withers

The funny thing is, your personal experience, when you're first trying to get started, these songs that now people are interested in, trying to find out how you came up with it, in those days, you couldn't get anybody to sit and listen to the damn thing. They'd start talking halfway through the first verse. You know the most annoying thing in the world? When you've got this new song and you're trying to play it for somebody, and instead of listening to the damn song, they're talking. Then 30 years later, after this song becomes something else, now you're trying to accommodate everybody - and it's flattering, don't get me wrong here, I'm just talking about the irony and the humor in the whole thing - now 30 years later, 50,000 people want you to explain it to them. When at the actual point when you were doing it, when it was fresh in your memory, nobody would even listen to the shit without interrupting.

Songfacts: I told Mrs. Withers I'd use a half an hour and I'm going to honor that. I really appreciate you taking the time to speak with us.

Withers: Well, it was fun Carl. I hope I didn't bore you.

Songfacts: You certainly didn't.

Withers: OK Carl, you be well.

January 2, 2004

Get more at billwithersmusic.com

Further reading:

Interview with Booker T. Jones

Bill Withers

(b. July 4, 1938)

Artist Biography by Ed Hogan

Songwriter/singer/guitarist Bill Withers is best remembered for the classic "Lean on Me" and his other million-selling singles "Ain't No Sunshine" and "Use Me," but he has a sizable cache of great songs to his credit. Al Jarreau recorded an entire CD of Withers' songs on Tribute to Bill Withers (Culture Press 1998). His popular radio-aired LP track from Still Bill, "Who Is He? (And What Is He to You?)," was a 1974 R&B hit for Creative Source.

Born July 4, 1938, in Slab Fork, WV, Withers was the youngest of six children. His father died when he was a child and he was raised by his mother and grandmother. After a nine-year stint in the Navy, Withers moved to Los Angeles to pursue a music career in 1967. He recorded demos at night while working at the Boeing aircraft company where he made toilet seats. His recording career began after being introduced to Clarence Avant, president of Sussex Records.

Stax Records stalwart Booker T. Jones produced his debut album, Just As I Am (with some co-production by Al Jackson, Jr.), which included his first charting single, "Ain't No Sunshine" that went gold and made it to number six R&B and number three pop in summer 1971 and won a Grammy as Best R&B Song. Its follow-up, "Grandma Hands," peaked at number 18 R&B in fall 1971. The song was later covered by the Staple Singers and received airplay as a track from their 1973 Stax LP Be What You Are. "Just As I Am" featured lead guitar by Stephen Stills and hit number five R&B in summer 1971.

Withers wrote "Lean on Me" based on his experiences growing up in a West Virginia coal mining town. Times were hard and when a neighbor needed something beyond their means, the rest of the community would chip in and help. He came up with the chord progression while noodling around on his new Wurlitzer electric piano. The sound of the chords reminded Withers of the hymns that he heard at church while he was growing up. On the session for "Lean on Me," members of the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band ("Express Yourself," "Loveland") were used: drummer James Gadson, keyboardist Ray Jackson, guitarist Benorce Blackman (co-wrote with Withers "The Best You Can" from Making Music), and bassist Melvin Dunlop. His second gold single, "Lean on Me," landed at number one R&B and number one pop for three weeks on Billboard's charts in summer 1972. It was included on his Still Bill album which went gold, holding the number one R&B spot for six weeks and hitting number four pop in spring 1972. "Lean on Me" has became a standard with hit covers by U.K. rock band Mud and Club Nouveau. "Lean on Me" was also the title theme of a 1989 movie starring Morgan Freeman. Still Bill also included "Use Me" (gold, number two R&B for two weeks and number two pop for two weeks in fall 1972) .

Withers' Sussex catalog also included Bill Withers Live at Carnegie Hall, 'Justments, and The Best of Bill Withers. Withers contributed "Better Days" to the soundtrack of the Bill Cosby 1971 western Man And Boy, released on Sussex. There was a duet single with Bobby Womack on United Artists, "It's All Over Now," from summer 1975.

After a legal battle with Sussex, Withers signed with Columbia Records. Columbia later bought his Sussex masters when the label went out of business. Withers was briefly married actress Denise Nicholas (ABC-TV's Room 222 and the 1972 horror film Blacula) in the early '70s. His releases on Columbia were Making Music ("Make Love to Your Mind," number ten R&B), which hit number seven R&B in late 1975; Naked and Warm; Menagerie ("Lovely Day," a number six R&B hit), which went gold in 1977; and 'Bout Love from spring 1979. Teaming with Elektra Records artist Grover Washington, Jr., Withers sang the crystalline ballad "Just the Two of Us," written by Withers, Ralph MacDonald, and William Salter. It went to number three R&B and held the number two pop spot for three weeks in early 1981. "Just the Two of Us" was redone with hilarious effect in the Mike Myers movie Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, released in summer 1999. Withers teamed with MacDonald for MacDonald's Polydor single "In the Name of Love" in summer 1984.

Withers' last charting LP was Watching You, Watching Me in spring 1985. He occasionally did dates with Grover Washington, Jr. during the '90s. His songs and recordings have been used as both the source of numerous covers (Aaron Neville's "Use Me") and sampled by a multitude of hip-hop/rap groups. Withers resurfaced in the 21st century, playing concerts, and having his albums reissued in various countries. He is also the subject of the 2010 bio-documentary Still Bill, by filmmakers Damani Baker and Alex Vlack.

Bill Withers

Brilliant. Tough. Uncompromising. Bill Withers stuck to his guns.

Some people labeled him as difficult, but Bill Withers was simply a man with a vision that he would not compromise. Ever faithful to his muse, he refused to play along with the industry and carved out his own success.

Some people labeled him as difficult, but Bill Withers was simply a man with a vision that he would not compromise. Ever faithful to his muse, he refused to play along with the industry and carved out his own success.

Biography

Bill Withers: The Soul Man Who Walked Away

In 1970, the singer was a guy in his thirties with a job and a

lunch pail. Then he wrote ‘Ain’t No Sunshine,’ and things got

complicated

by Andy Greene

April 14, 2015

Rolling Stone

Bill Withers speaks onstage at the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles in 2011. This year the singer will be inductedinto the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Reed Saxton

On a clear day, you can see the Staples Center from Bill Withers’

house, which sits high in the hills above West Hollywood. Today, in

about two hours, the Los Angeles basketball arena will host the Grammy

Awards; every once in a while, a limo will rush through Withers’

neighborhood, on its way to the event. But the 76-year-old Withers could

not be less interested. He’s padding around his home wearing Adidas

track pants, an old T-shirt with a drawing of a bus on it, and athletic

sandals with blue socks. On the mantel in a hallway, there is a Best

R&B Song award, for 1980’s “Just the Two of Us,” from the last time

he attended the show, three decades ago; it sits next to two other

Grammys, for 1971’s “Ain’t No Sunshine” and 1972’s “Lean on Me.” A few

years after “Two of Us,” Withers became one of the few stars in

pop-music history to truly walk away from a lucrative career, entirely

of his own volition, and never look back. “These days,” he says, “I

wouldn’t know a pop chart from a Pop-Tart.”

As the Grammy telecast begins, and AC/DC kick off the show, Withers

jumps into his Lexus SUV and heads down to his favorite restaurant, Le

Petit Four; he has a hankering for liver and onions but settles for the

blackened catfish. The hostess knows him by name, but otherwise he

blends into the crowd. “I grew up in the age of Barbra Streisand, Aretha

Franklin, Nancy Wilson,” he says, still musing on the Grammys. “It was a

time where a fat, ugly broad that could sing had value. Now everything

is about image. It’s not poetry. This just isn’t my time.”Withers has been out of the spotlight for so many years that some people think he passed away. “Sometimes I wake up and I wonder myself,” he says with a hearty chuckle. “A very famous minister actually called me to find out whether I was dead or not. I said to him, ‘Let me check.’"

Others don’t believe he is who he says: “One Sunday morning I was at Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles. These church ladies were sitting in the booth next to mine. They were talking about this Bill Withers song they sang in church that morning. I got up on my elbow, leaned into their booth and said, ‘Ladies, it’s odd you should mention that because I’m Bill Withers.’ This lady said, ‘You ain’t no Bill Withers. You’re too light-skinned to be Bill Withers!’ ”

His career lasted eight years by his own count; in that time, he wrote and recorded some of the most loved, most covered songs of all time, particularly “Lean on Me” and “Ain’t No Sunshine” — tunes that feature dead-simple, soulful instrumentation and pure melodies that haven’t aged a second. “He’s the last African-American Everyman,” says Questlove. “Jordan’s vertical jump has to be higher than everyone. Michael Jackson has to defy gravity. On the other side of the coin, we’re often viewed as primitive animals. We rarely land in the middle. Bill Withers is the closest thing black people have to a Bruce Springsteen.”

Withers was stunned when he learned he had been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this year. “I see it as an award of attrition,” he says. “What few songs I wrote during my brief career, there ain’t a genre that somebody didn’t record them in. I’m not a virtuoso, but I was able to write songs that people could identify with. I don’t think I’ve done bad for a guy from Slab Fork, West Virginia.”

Withers’ hometown is in a poor rural area in one of the poorest states in the Union. His father, who worked in the coal mines, died when Bill was 13. “We lived right on the border of the black and white neighborhood,” he says. “I heard guys playing country music, and in church I heard gospel. There was music everywhere.”

The youngest of six children, Withers was born with a stutter and had a hard time fitting in. “When you stutter, people have a tendency to disregard you,” he says. That was compounded by the unvarnished Jim Crow racism that was a way of life in his youth. “One of the first things I learned, when I was around four, was that if you make a mistake and go into a white women’s bathroom, they’re going to kill your father.” He was a teenager when Emmett Till, a 14-year-old from Chicago who allegedly whistled at a white woman while visiting relatives in Mississippi, was beaten to death by two men who were cleared of all charges by an all-white jury. “[Till] was right around my age,” says Withers. “I thought, ‘Didn’t he know better?’ ”

Desperate to get out of Slab Fork, he enlisted in the Navy right after graduating from high school in 1956. Harry Truman had desegregated the armed forces eight years earlier, but Withers quickly discovered that didn’t mean much at his first naval base, in Pensacola, Florida. “My first goal was, I didn’t want to be a cook or a steward,” he says. “So I went to aircraft-mechanic school. I still had to prove to people that thought I was genetically inferior that I wasn’t too stupid to drain the oil out of an airplane.”

By the time he was transferred to California in the mid-1960s, he realized he’d never have the courage to quit the Navy if he couldn’t rid himself of his stutter. “I couldn’t get out a word,” he says. “I realized it wasn’t physical. I figured out that my stutter — and this isn’t the case for everyone — was caused by fear of the perception of the listener. I had a much higher opinion of everyone else than I did of myself. I started doing things like imagining everybody naked — all kinds of tricks I used on myself.”

Against all conventional wisdom, it worked (though he still trips over the occasional word), and in 1965 he quit the Navy and became “the first black milkman in Santa Clara County, California.” He eventually took a job at an aircraft parts factory. As a Navy aircraft mechanic, he was ridiculously overqualified, but “it was all about survival.”

One night around that time, he visited a club in Oakland where Lou Rawls was playing. “He was late, and the manager was pacing back and forth,” says Withers. “I remember him saying, ‘I’m paying this guy $2,000 a week and he can’t show up on time.’ I was making $3 an hour, looking for friendly women, but nobody found me interesting. Then Rawls walked in, and all these women are talking to him.”

Withers was in his late twenties. His music-business experience consisted of sitting in a couple of times with a bar band while stationed in Guam in the Navy. He’d never played the guitar, but he headed to a pawn shop, bought a cheap one and began teaching himself to play. Between shifts at the factory, he began writing his own tunes. “I figured out that you didn’t need to be a virtuoso to accompany yourself,” he says.

He began saving from each paycheck until he had enough to record a crude demo. Withers shopped it around to major labels, which weren’t interested, but then he got a meeting with Clarence Avant, a black music executive who had recently founded the indie label Sussex and had just signed the songwriter Rodriguez (of Searching for Sugar Man fame). “[Withers’] songs were unbelievable,” Avant remembers. “You just had to listen to his lyrics. I gave him a deal and set him up with Booker T. Jones to produce his album.”

Withers was extremely uneasy until Graham Nash walked into the studio. “He sat down in front of me and said, ‘You don’t know how good you are,’ ” Withers says. “I’ll never forget it.” They laid down the basic tracks for what became 1971’s Just As I Am in a few days. (One of the songs was inspired by the 1962 Jack Lemmon-Lee Remick movie Days of Wine and Roses; Withers was watching it on TV, and the doomed relationship at the film’s center brought to mind a phrase: “Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone.”)

The album’s cover photo was taken during Withers’ lunch break at the factory; you can see him holding his lunch pail. “My co-workers were making fun of me,” he says. “They thought it was a joke.” Still unconvinced that music would pay off, he held on to his day job until he was laid off in the months before the album’s release. Then, one day, “two letters came in the mail. One was asking me to come back to my job. The other was inviting me on to Johnny Carson.” The Tonight Show appearance, in November 1971, helped propel “Ain’t No Sunshine” into the Top 10, and the follow-up, “Grandma’s Hands,” reached Number 42.

By then, Withers was 32; he still marvels at the fact that he was able to come out of nowhere at that relatively advanced age. “Imagine 40,000 people at a stadium watching a football game,” he says. “About 10,000 of them think they can play quarterback. Three of them probably could. I guess I was one of those three.”

He took some earnings, bought a piano and, again, with no training, began fiddling around. One of the first things he came up with was a simple chord progression: “I didn’t change fingers. I just went one, two, three, four, up and down the piano. It was the first thing I learned to play. Even a tiny child can play that.”

Tired of love songs, he wrote a simple ode to friendship called “Lean on Me.” Withers didn’t think much of it. “But the guys at the record company thought it was a single,” he says. It became the centerpiece of his second album, 1972’s Still Bill. The song rocketed to Number One and was inescapable for the entire year.

Withers was now a hot commodity, appearing on Soul Train and the BBC, and headlining a show at Carnegie Hall that was released as a live album. But he refused to hire a manager, insisting on overseeing every aspect of his career, from producing his own songs to writing the liner notes to designing his album covers. “He was so opinionated,” says Avant. “I was the closest thing he had to a manager. Everybody was scared of him.”

“Early on, I had a manager for a couple of months, and it felt like getting a gasoline enema,” says Withers. “Nobody had my interest at heart. I felt like a pawn. I like being my own man.”

In 1973, Withers married Denise Nicholas, a star of the TV show Room 222. It was a rocky relationship from the start. “Their wedding day was the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen,” Avant says. “I remember her semi-crying. She said, ‘He doesn’t love me.’ I said, ‘Bill, what are you doing getting married?’ He said, ‘I want everyone back home to know I’m marrying one of these Hollywood actresses.’ ” Withers and Nicholas had terrible fights, which soon began getting coverage in magazines like Jet; the couple split after little more than a year. Withers poured all of his pain from the breakup into his 1974 LP +’Justments. “It was like a diary,” says Questlove. “That album was a pre-reality-show look at his life. Keep in mind this was years before Marvin Gaye did it with Here, My Dear.“

Withers was also unhappy on the road. Despite having enormous radio hits, he found himself opening up for incongruous acts like Jethro Tull and making less money than he felt he deserved. Things got worse when Sussex went bankrupt in 1975, and Withers signed a five-record deal with Columbia. “I met my A&R guy, and the first thing he said to me was, ‘I don’t like your music or any black music, period,’ ” says Withers. “I am proud of myself because I did not hit him. I met another executive who was looking at a photo of the Four Tops in a magazine. He actually said to me, ‘Look at these ugly niggers.’ ”

At Sussex, he had complete creative control over his music, but at Columbia he found himself in the middle of a large corporation that was second-guessing his moves. As he relives this part of his past, he gets teary. “There were no black executives,” he says. “They’d say shit to me like, ‘Why are there no horns on the song?’ ‘Why is this intro so long?’ . . . This one guy at Columbia, Mickey Eichner, was a huge pain in the ass,” he adds. “He told me to cover Elvis Presley’s ‘In the Ghetto.’ I’m a songwriter! That would be like buying a bartender a drink.”

Eichner, who was the head of Columbia’s A&R department, says he’s “hurt” by Withers’ words, and he has a different recollection of events. “He submitted a rec-ord, and we didn’t hear a single,” he says. “I suggested he maybe do an Elvis cover. He’s very stubborn. I believe that a manager would have understood what I was trying to do, but he didn’t have one, so there was nobody I could reason with.” As far as racism at Columbia, Eichner says he doesn’t recall “hearing or seeing anything.”

With the exception of 1977’s Menagerie (which contains the funky classic “Lovely Day”), none of the Columbia albums reached the Top 40. Withers’ 1980 hit “Just the Two of Us” was a duet with Grover Washington Jr. on Elektra – “That was a ‘kiss my ass’ song to Columbia,” says Withers. The low point came during the sessions for his last album, 1985’s Watching You Watching Me. “They made me record that album at some guy’s home studio,” he says. “This stark-naked five-year-old girl was running around the house, and they said to her, ‘We’re busy. Go play with Bill.’ Now, I’m this big black guy and they’re sending a little naked white girl over to play with me! I said, ‘I gotta get out of here. I can’t take this shit!’ ”

Withers hasn’t released a note of music since then, aside from a guest spot on a 2004 Jimmy Buffett song; he has not performed publicly in concert in nearly 25 years. Right now he’s sitting at his kitchen table reading a political blog on his iPad, as CNN runs quietly on a nearby TV. He watches a lot of television, and he especially loves Mike & Molly, The Big Bang Theory and the MSNBC prison documentary series Lockup. “I really have no idea what he does all day,” says his wife, Marcia. “But he does a lot on his iPad. He always knows exactly what’s going on in the world. Whenever I mention anything, he says, ‘Oh, that’s old news.’ ”

Marcia, who met Withers in 1976, runs his publishing company from a tiny office on Sunset Boulevard. “We’re a mom-and-pop shop,” he says. “She’s my only overseer. I’m lucky I married a woman with an MBA.” Since Withers was the sole writer of most of his material, he gets half of every dollar his catalog generates – and “Lean on Me” alone has appeared in innumerable TV shows, movies and commercials. Any licensee that wants to use Withers’ master version of one of his songs needs his approval. “If it’s for a scene in a show where somebody is killed or something, we will turn them down,” says Marcia. “We don’t want people to associate, say, ‘Lean on Me’ with violence.” Technically, it’s possible to license a cover of one of his songs without his consent. “But that’s never happened,” he says. “They don’t want to piss me off.”

Bill and Marcia have invested wisely in L.A. real estate. For the past 17 years, they’ve lived in their 5,000-square-foot house, which has three stories and an elevator and is furnished with pricey-looking African art; they bought the home for $700,000 in 1998, and it’s now worth many times that. It’s crammed with books and mementos from Withers’ career, including a 1974 photo of him with Muhammad Ali. There’s an exercise room on the third floor with several machines, which all look brand-new.

Their children, Todd and Kori, are both in their thirties and live nearby. Bill was an active father after he left the music biz, and he’s very close to them. “We’d have James Brown dance parties in our pajamas,” says Kori, “and take cross-country road trips, blasting Chuck Berry songs the whole time.” Withers also occupied himself with construction projects at his investment properties. (“When I moved to New York for college, he built a wall in the middle of my apartment with a door on it,” says Kori. “He’s always building something.”)

The Withers house also has a recording studio, but Bill has little interest in making new music. “I need a motivator or something to goose me up,” he says. “They need to come out with a Viagra-like pill for folks my age to regenerate that need to show off. But back where I’m from, people sit on their porch all day.”

He’s turned down more offers for comeback tours than he can count. “What else do I need to buy?” he says. “I’m just so fortunate. I’ve got a nice wife, man, who treats me like gold. I don’t deserve her. My wife dotes on me. I’m very pleased with my life how it is. This business came to me in my thirties. I was socialized as a regular guy. I never felt like I owned it or it owned me.”

He hasn’t ruled out a performance at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in April, though. “There are things that will decide that for me,” he says, mysteriously. Says Marcia, “I know he doesn’t like how older people sound when they sing. I don’t push him. People say that I enable him, but he’s just over it. “

In the meantime, Questlove is determined to get him back to work. “I started my campaign to produce a Bill Withers album back in 2004,” he says. “My first audition was to produce an Al Green album. I figured Bill would see it, love it and agree to record with me. He said, ‘Nope, I’m fine. I don’t want to sing.’ So I made an album with his friend Booker T. Jones, but same thing. Finally I recorded Withers’ ‘I Can’t Write Left Handed’ with John Legend. He still said, ‘Nope.’ ”

The Legend-Roots album with “Left Handed” won three Grammys, but Withers was unimpressed. “I won’t give up,” says Questlove. “He’s my hero.”

The Okayplayer Interview: Bill Withers Speaks On Songwriting, Sampling & Legendary Concerts From Zaire To Carnegie Hall

For students of soul, Bill Withers–as Questlove so aptly put it–is our Everyman. An airplane mechanic who never played an instrument until he picked up a guitar and decided to teach himself songwriting–and wrote “Ain’t No Sunshine” on on of his first demos out–Withers also never quit his day-job, even after it was clear he had a hit and a record deal on his hands. More hits followed–“Lean On Me”; “Grandma’s Hands”; “Use Me”; “Lovely Day”; “Just The Two of Us,” just to name a few. But after a decade or two of label politics and A&Rs trying to tell him what to sing, Withers famously walked away from it all…yet still managed to live comfortably by retaining control of his own catalog. In addition to gifting us with an inspiring discography of composition; as close to unmediated personal expression as the entertainment biz could handle, his career stands equally as testament to the ideal of craft over industry, of self-determination over the trappings of fame.

A series of retrospective recognitions of Withers’ achievements–beginning with his recent induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, continuing with his ‘Master Class’ lecture at ASCAP’s EXPO 2015 (watch his onstage interview with Aloe Blacc here) and culminating this Thursday, October 1st with a Carnegie Hall Tribute to his music, featuring the likes of

The Carnegie Hall tribute in particular, recreates Withers’ iconic 1972 concert in the legendary performance space–an immortal moment in live music and a highlight in a performing career that also including stops in Kinshasa to join James Brown, BB King, Miriam Makeba, Celia Cruz and a few others onstage at the Zaire ’74 concert that accompanied Muhammad Ali’s epic Rumble In The Jungle with George Foreman. Taking advantage of this brief window of press availability, Okayplayer managed to jump on the phone with a mellow, effusive but ever-grounded Withers and pick the troubador’s thoughts on songwriting, sampling and some of the standout moments from those classic concerts–as well as sussing out his chances of ever recording again, preferably with Questlove at the helm, please and thank you. Read on for Bill Withers’ definitive Okayplayer Interview:

OKP: Thanks for taking the time to speak with us. Have you been doing a lot of these?

BW: No.

OKP: I know you’re not a big interview guy, but I with the Carnegie Hall tribute coming up figured they’d probably be pressing you for a few.

BW: Oh, I do interviews, it’s just that nobody wants to talk to me. I’m not that interesting.

OKP: I beg to differ, we’re very interested! For one thing, I’m interested to know what your perspective is, on this whole Carnegie Hall event…

BW: Well, it’s kind of nice, huh? That people would do that. There are going to be some young people that are probably the age of my kids coming over there to hear my songs, that’s nice.

OKP: Were you familiar with most of the artists that were selected for the bill?

BW: Of course. If I wasn’t, I wouldn’t tell you [laughs]. Yeah, most of them I’ve had personal interactions with.

OKP: I was going to ask you if there are people amongst that generation who are either recording now or just coming up, that you’ve felt were carrying the torch, so to speak, of the music that you pioneered?

BW:Yeah, you know. They’re very nice people, and nice of them to do that. I’m surprised they even know who I am.

OKP: Well, you shouldn’t be. You must be aware that a whole generation has been very influenced by your songs; they’re certainly some of the most covered and sampled songs in the world. Which makes me wonder–as an artist who’s always written for yourself, avoided covering others–how do you feel about being covered, yourself? When you wrote songs, did you think about other people performing them and playing them?

BW: No. When I was writing them, I was just trying to finish them. It’s not an easy thing to do. I like the poetry of songs, you know. So I tend to lean toward songs that have some kind of poetic effect. There are a gazillion kinds of music, there’s rock music and dance music and whatever. I just happened to like the poetry of it. It’s challenging to be able to say something reasonably profound in a three minute time limit, you know? You could sit down and write an article and use sentences and stuff, but songs are different—they have the added burden of having to rhyme. It’s an interesting endeavor.

OKP:I think the emphasis on the poetry and lyrics is probably what made the core of your songs so appealing for people to cover or sample over the years. I know you’re pretty active in the publishing process of your music—have there been covers or samples that you didn’t want to approve? That weren’t doing justice to the song and the way you wrote it?

BW: Yeah, there are some things that I haven’t approved. My wife basically does that, and she’ll run it by me. It’s like anything else.

OKP: Part of the reason I ask is I’m from the generation that knew “Lean On Me” from the Club Nouveau cover, and even “Lovely Day”—there was a UK group (S.O.U.L. S.Y.S.T.E.M.) that remixed it, and introduced that music to a whole new generation. How do you feel about that kind of remixing and sampling, as far as that goes?

BW: Well, it depends on the sample. Sometimes you have to go at them, because they do it and they don’t credit you. That can be annoying, and there’s always something going on, somebody trying to get away with that. But it’s flattery, when people pick something. They got a lot of mileage out of the “No Diggity” sample and other staples, so yeah that’s fun and flattering. And this is the music business, you know.

OKP: In terms of hearing your music played back by other people, and reinterpreted. DO you have favorite songs of your own? I know some artists don’t like to hear their own voice on tape or to listen to someone else play their music, but how do you feel about hearing your own music in somebody else’s hands?

BW: Well, I don’t sit around listening to that stuff, you know. By the time you finish recording it, believe me, you’ve heard it over and over and over again. Especially if you’re your own producer, like I’ve been. You don’t let it go until you’re reasonably satisfied with it, so I don’t have any special feelings with that. Plus, it’s been a long time and I’m used to it by now. You know, it’s like your grandfather looking at your grandmother naked. He’s seen it a lot. [laughs] That’s a great analogy.

OKP: But aren’t there times when your grandfather looked at your grandmother naked and feels that old feeling again?

BW: Of course—that’s how she got to be your grandmother! When something is right for you, it doesn’t lose its appeal. I think that’s why you were mentioning longevity in songs, I think the ones that last are the ones that don’t lose their appeal. There are some huge songs in a certain period, but you never hear them again. They’ve served their purpose for that period.

There are a lot of beautiful women in the world—why do you stop at one? Who knows….

OKP: I know you walked away from the recording side of the music business. Do you still play and write music for yourself?

BW: Yeah, if I wanted to. I mean, I’ve written for other people. I’ve written for Jimmy Buffet. His album ‘When They Built the Statues,’—for Bill Russell in Boston, he asked me to write something. I don’t think songwriting is something you do, I think it’s the way you are. So just because something’s not organized and put into the system doesn’t mean you stop thinking or feeling or whatever you use. I don’t think you can turn that process off, unless you die or get some serious dementia. And even through dementia, people—you notice Glen Campbell can still play?

OKP: They say music can actually help people recover from things that affect your cognitive understanding—music can be a powerful thing for healing.

BW: Well, I don’t know too many people who have recovered, but it can help you sustain yourself.

OKP: Right. It’s good for your mental health. Are you a person who, when you’re relaxing, has a guitar close at hand? Or is it more about when you feel the occasion is right to go write a song?

BW: You know, it’s funny you brought that up. I just realized the other day—I don’t think I’ve picked one up in a couple of years. It’s hanging on the wall right by my desk. I need to go over and pick that up.

OKP: I’m glad I put that on your to-do list…

BW: I think my wife bought a guitar on eBay and asked me to tune it, so one day I’ll pick it up and tune it. But different things happen in different times in your life. I’m 77 years old, you know. The things I do now would probably be more common to people of that age group. I would like to run and jump and roll over and stuff like that, but I don’t want to hurt myself.

OKP: I don’t know if you know, but the press outlet that I write for was founded by Questlove, who you probably know is a big fan of yours…

BW: Oh, my man! He’s always been very nice to me, he’s overly nice to me. I like him. He’s just been very generous and very kind to me.

OKP: I think he’s holding out hope that you guys might record together one day…do you think he’s got a shot?

BW: I don’t know, man. My wife could get pregnant next month, I don’t know. A lot of stuff happens. I have no idea, you know.

OKP: Anything could happen?

BW: Yeah. It’s easier to plan things at his age than it is at mine!

OKP: Since we’re looking forward to the Carnegie Hall tribute, I got to thinking about some of you other live highlights. The whole Zaire ’74 concert is such an iconic moment, and I’ve never heard your perspective of your own experience meeting Muhammad Ali and being there for that whole event. Do you have particular memories that stand out from that trip?

BW: Well, I already had met him [Ali] before the trip, you know. I had known him and he had always been a nice, fun guy. It was interesting because you had a lot of characters, you had Don King—and nobody had ever heard of Don King before then. He’s got a very colorful background, you know. And then it was interesting watching people that normally wouldn’t be in that proximity to each other. You had Norman Mailer, BB King and James Brown, you know. They normally wouldn’t be in the same space, but since we’re all staying at the same hotel, there was an interesting interaction there that normal wouldn’t take place. Because these people wouldn’t have access to each other, you know.

And then there was just the fact of where we were, you know. Everybody was forced to interact with each other because we’re all staying in this one hotel, we were on a continent that nobody knew a lot about. It was just an all-around interesting trip. I don’t think that’ll ever happen again, that that many different kinds of people will be assembled in one place for that long. What does that say about the magic of Muhammad Ali? Nobody else that I know of in history has been able to gather those many different kinds of people around. George was there too, but let’s face it, it was about Ali and his charisma and magic. What’s the likelihood of somebody like Don King putting it together?

There was a lot of once-in-a-lifetime stuff. I remember standing at the middle of the place at rehearsal in the middle of the night and there were jazz guys like The Crusaders, there was James Brown, The Pointer Sisters, all kinds of people, and they had people like Stokely Carmichael just hanging out. That was the fun part of it. Two guys fighting each other in the middle of the night—I’ve been seeing that all my life. But the interesting thing was the theater around it…I didn’t stay for the fight, because it got postponed. For me the experience was over anyway, because the interesting thing was the atmosphere around it. All those things.

OKP: Was that your first time on the continent of Africa?

BW: Yep, that was my first time.

OKP: Were you able to get out of the hotel and see some of Zaire? I imagine, politically, it might have been tightly stage-managed as well, because of the high-profile nature of it.

BW: I walked around a little bit, you know. I’m an old sailor, I spent nine years in the navy. I know how to get around places that are interesting to me. I was walking around in foreign countries when I was eighteen years old. There were things that were interesting—curiosity got me out and about. It’s not like I could rent a car and start driving around.

OKP: Was there anything that struck you from those impressions of Zaire, outside the circle of the event that was happening?