SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER/FALL, 2017

VOLUME FOUR NUMBER THREE

ESPERANZA SPALDING

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JAZZMEIA HORN

(August 12-18)

ROY HAYNES

(August 19-25)

MCCOY TYNER

(August 26-September 1)

AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE

(September 2-8)

AARON DIEHL

(September 9-15)

CECILE MCLORIN SALVANT

(September 16-22)

REGGIE WORKMAN

(September 23-29)

ANDREW CYRILLE

(September 30-October 6)

BARRY HARRIS

BARRY HARRIS

(October 7-13)

MARQUIS HILL

(October 14-20)

HERBIE NICHOLS

(October 21-27)

GREG OSBY

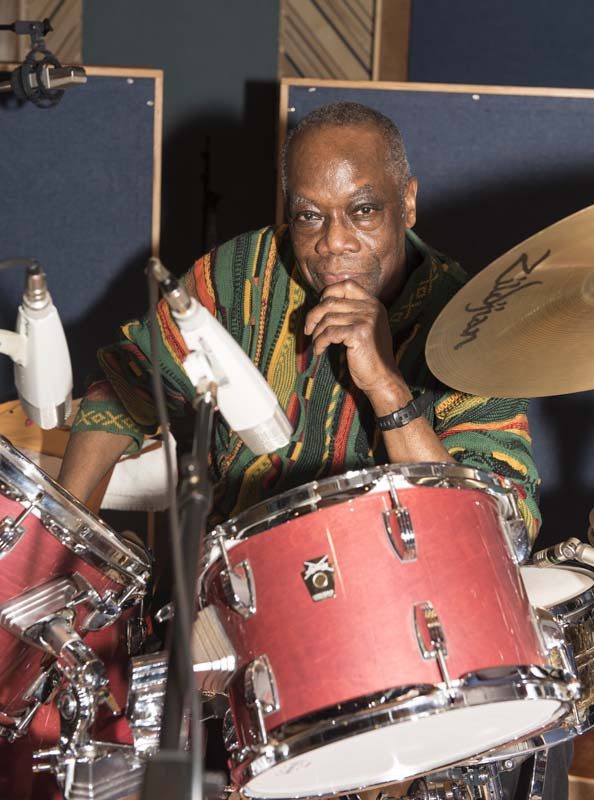

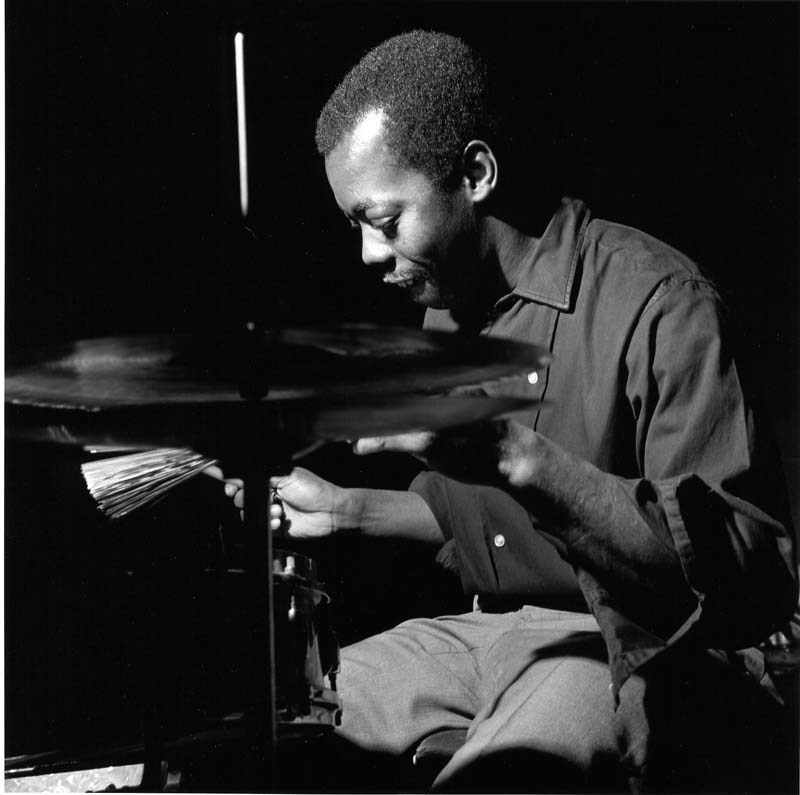

Andrew Cyrille

(b. November 10, 1939)

Artist Biography by Chris Kelsey

Andrew Cyrille is perhaps the preeminent free-jazz percussionist of the 1980s and '90s. Few free-jazz drummers play with a tenth of Cyrille's grace and authority. His energy is unflagging, his power absolute, tempered only by an ever-present sense of propriety. Cyrille is at his best in an utterly free context, as on his encounters with the ambidextrous pianist Borah Bergman, where his serrated rhythms and variable textures are given maximum latitude. Cyrille began playing drums in a drum and bugle corps at the age of 11. At 15, he played in a trio with guitarist Eric Gale. For a period in his teens, Cyrille studied chemistry before enrolling in Juilliard School of Music in 1958. In the late '50s and early '60s, he worked with such mainstream jazzers as Mary Lou Williams, Roland Hanna, Roland Kirk, Coleman Hawkins, and Junior Mance. He recorded with Hawkins, as well as tenor saxophonist Bill Barron, for the Savoy label. Cyrille succeeded Sunny Murray as Cecil Taylor's drummer in 1964. He stayed with the pianist until 1975, during which time he played on many of Taylor's classic albums. During that period he played with a good many other top players, including Marion Brown, Grachan Moncur III and Jimmy Giuffre. He also served for a time as artist in residence at Antioch College and recorded a solo percussion album, 1969's What About?, on BYG. Cyrille, Rashied Ali, and Milford Graves collaborated on a series of mid-'70s concerts entitled "Dialogue of the Drums." Beginning in 1975 and lasting into the '80s, Cyrille led his own group, called Maono, which included the tenor saxophonist David S. Ware, trumpeter Ted Daniel, pianist Sonelius Smith, and at various times bassists Lisle Atkinson and Nick DiGeronimo. During this time Cyrille also played with the Group, a band that included the violinist Billy Bang, bassist Sirone, altoist Brown, and trumpeter Ahmed Abdullah. With Graves, Don Moye, and Kenny Clarke, Cyrille recorded the all-percussion album Pieces of Time for Soul Note in 1983. When not leading his own bands, he also worked ubiquitously as a sideman with, among others, John Carter, Muhal Richard Abrams, and Jimmy Lyons. Cyrille continued as a leading player into the late '90s, recording fairly prolifically for Black Saint/Soul Note, FMP, and DIW.

Andrew Cyrille

Andrew Cyrille was born in Brooklyn, NY. As well as studying privately, he attended the Juilliard and Hartnett schools of music. He has performed with Jazz artists ranging from Coleman Hawkins, Illinois Jacquet and Mary Lou Williams to Kenny Dorham, Muhal Richard Abrams, Horace Tapscott, John Carter,Mal Waldron and David Murray. In 1964 he formed and association with pianist Cecil Taylor that would last for 11 years. He played drums for many notable dancer-choreogrphers from the mid to late 1960’s.

He was artist-residence and teacher at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio from 1971 to 1973. Cyrille has also taught at the Graham Windham Home for Children in New York. He is currently a faculty member at the New School University (formally The New School for Social Research) in New York City. His sterling work has earned him a number of grants and awards from the National Endowment for the Arts and Meet the Composer, including a commission to create a new work for the Cleo Parker Robinson Dance Company in 1990. In 1999, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship for composition.

Starting in 1969, Cyrille began to organize the first of several percussion groups, including Dialogue of the Drums, Pieces of Time, and Weights and Measures. Some of the distinguished artists who played in these groups were Kenny Clark, Milford Graves, Famoudou Don Moye, Michael Carvin and Obo Addy. Starting in 1988 through the present time, he has toured and performed here and abroad with the renown Russian percussionist, Vladimir Tarasov.

In 1975,Cyrille formed a band called Maono (feelings) featuring various instrumental voices determined by his compositions. He is a member of Trio 3 featuring alto saxophonist, Oliver Lake and bassist, Reggie Workman. Also from time to time,he leads another group called Haitian Fascination, playing music inspired by the musical tradition from Haiti. Within the past several years, he has been collaborating and working with musicians such as saxophonist, Archie Shepp, trombonist, Roswell Rudd, trumpeter, Dave Douglas, bassists, Henry Grimes andWilliam Parker, pianists Dave Burrell and Marilyn Crispell, and vibraphonist, Karl Berger. He continues to record and perform with duo, trio, quartet, quintet and big band formations.

AAJ CD Review of Open Ideas

He used very soft rubber-tipped mallets, so you could hear him as predominantly as necessary on recordings, but it was hard to hear him in an acoustic setting. A lot of the other vibes players, like Milt Jackson, Lionel Hampton, Red Norvo and Terry Gibbs, played with much harder mallet heads. Walt would also cut the stems so they weren’t full-length mallets. That was the sound he wanted to get, and it also helped him with speed; he was one of the fastest vibists I ever heard.

It’s the same as doing a duet with a piano player, a drummer or a trumpet player. Milford Graves did one with David Murray, Real Deal. I did two duo recordings with Jimmy Lyons in the ’80s, Something in Return and Burnt Offering, and then I did another one with Greg Osby, Low Blue Flame. I never recorded anything with Frank Wright, except some stuff I had done in the ’80s at Soundscape, Verna Gillis’ place. I did a duet with Henry Threadgill, and a concert with David Murray in Canada, also with trombonist Craig Harris.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/andrew-cyrille-bringer-of-forms-by-aaj-staff.php?pg=2

Andrew Cyrille: Bringer of Forms

by AAJ STAFF

May 12, 2003

"...I realized that we were doing something that was just a little bit different from what had been going on traditionally, but I always kept in mind that I wanted to make it an evolution of the tradition."

—Andrew Cyrille

This article was submitted on behalf of Hank Shteamer.

Percussionist Andrew Cyrille is as self-assured an artist as one is likely to encounter. "[Art is] all about trying to bring a form to life," he explains, "or give life to a form." Much of Cyrille's best work falls in the category of the former. For years, he has specialized in lending a sense of order to the work of players like Cecil Taylor, whose torrential flow of musical information can seem daunting, if not impenetrable. Listening to Cyrille play, one hears a very grounded force, yet one that constantly vibrates in tune with the life around it.

Cyrille is a creator in his own right as well. Along with his peers, explorers like Sunny Murray, Milford Graves , and Rashied Ali , Cyrille developed a new form of jazz percussion that freed itself from the constraint of meter and paved the way for the advancement of the avant-garde musics of Taylor, John Coltrane, Albert Ayler and others. A gifted educator with an awesome knowledge of the jazz tradition and its roots, Cyrille views his school of drummers not as iconoclasts, but as extenders of the language of jazz. His insight has allowed him to document himself and his peers in unique ways and to provide a holistic curriculum for his students.

As an innovator, documentor, and educator, Cyrille has always remained modest, adapting his expertise to the project at hand. This modesty may account for his limited recognition in the mainstream jazz community. Circa 2003, Andrew Cyrille continues to search for unique approaches not only to music-making, but also to making a living.

Cyrille was always a restless experimenter. He describes his early impulses to alter the conventional rhythms of jazz: "When I was with Mary Lou Williams [in the early ‘60s], I used to tell her that I'd like to find another way of playing the ride [cymbal], and she said, 'Well, if you do, you're not going to find anybody to work with.'"

Fortunately, Cyrille was able to find associates whose music accommodated, if not demanded, a freer style. "The person who allowed me to bring that idea, that concept [of ametrical drumming] to fruition was Cecil Taylor," he reveals. "Working with Cecil, that was what we did! If I wanted to play some stuff in meter with him, I could have. I think on occasion I did, but most of the time it was outside meter."

Cyrille was quick to recognize that he was not alone in his desire to rethink the role of the drum set in jazz. Here, he describes his various collaborations with his drummer peers: "I heard Sunny Murray playing free meter with Cecil Taylor, Milford [Graves] playing ametrically with [multi-reedist] Giuseppi Logan, and then of course too, I heard Rashied Ali playing with Coltrane on Interstellar Space. So around that time, I got the idea that I wanted to document us as a generation of drummers, and one of the best ways to do that was to have a drum choir."

"I remember Milford and I had gotten together to play, and then we decided that we wanted to expand the duet; so we got Rashied, and we called it "Dialogue of the Drums". Then in the early '80s, I thought of the idea of trying to - I hate to use the word 'legitimize', but at least show the evolution of our concept of drumming as it related to bebop, and I asked Kenny Clarke to do something with me and Milford and [Art Ensemble of Chicago drummer] Famoudou Don Moye. (This quartet recorded Pieces of Time for Soul Note records in 1983.) So the collaborations started once I realized that we were doing something that was just a little bit different from what had been going on traditionally, but I always kept in mind that I wanted to make it an evolution of the tradition."

In addition to having a remarkably deep understanding of the tradition of jazz drumming, Cyrille understands the various cultural roots that underlie it. He has released numerous records with African themes, such as Nuba (1979, Soul Note) and Ode to the Living Tree (1994, Evidence), the first jazz session ever recorded in Senegal, and he is able to trace a clear line between the rhythms of jazz and traditional African drumming. "I hear a lot of African music, and I hear something similar to the ride cymbal beat, 'dang, dinga-dang, dinga-dang,'" he notes. "Most of the jazz compositions that we know and love are based on that ride beat and all kinds of variations on it.

"You get the ride beat, and then you start playing certain things with the left hand on the snare drums, and you begin syncopating certain things with the bass drum, and the sock cymbal is involved. So, to me, it's almost like a choir of drummers each playing a different instrument and a different rhythm but all coming together in an ensemble. So when you put that kind of feeling and projection together with a lot of European information - in terms of rudiments, sticking, march beats played with a certain feeling - you get what we know as jazz and jazz drumming."

Cyrille views knowledge of the jazz tradition as a key to self-discovery. "I'm more about people finding themselves rather than being a clone of mine," he says when asked about his philosophy of teaching. When discussing the techniques of his early mentors, he speaks of a similarly open-ended approach that went beyond conventional lessons: "I used to hear Philly Joe Jones quite a bit. The interesting thing about it was that even though I would have liked to take a continuous series of lessons with him, it never really happened that way. You know, I'd hang out with him, and maybe on the subway, he'd show me something on his leg or something like that. So it was almost like he was the guy that put his arm around my shoulder, and he would talk to me and let me watch him, rather than saying, 'This is a lesson; study it for a week, and then come back.'"

One area of the tradition that Cyrille has helped to expand greatly is the drum solo. He first honed his solo technique by playing for dancers, an experience which Cyrille categorizes as "another outstanding chapter in my life as a drummer insofar as making music with the drum set so that people felt comfortable moving their bodies." His experience in this area was extensive and fruitful. "Every day I played two different classes," he recalls, "and that gave me the strength and imagination to play drum rhythms; and as a consequence, it wasn't that difficult for me to hold an audience playing solos."

Indeed, Cyrille's drum solos are totally captivating, not to mention unique in the world of jazz. On landmark recordings like 1971's What About? (BYG-Actuel) and 1978's The Loop (Ictus), Cyrille demonstrates a concept of percussion that incorporates breath and other subtle uses of the voice as well as uncommon instruments such as the slide whistle and, of all things, a newspaper.

"Sometimes you can get inspiration from anywhere," he explains. "I might think of body and soul and how I could express that in a musical way. So on that What About? album, when I conceived of the piece called "From Whence I Came", it had to do with that concept of body and soul. So the body was the sounds that you hear on the drums and my breath was the soul. I would breathe and play rhythms around the breathing.

"There was one thing I did on The Loop called "The News", where I put a newspaper on the drum set and played on the newspaper. And at the end of the composition to bring into focus what I was trying to say, I rolled up the paper and you hear that noise like when you ball paper together [makes gurgling sound in imitation and laughs]."

Such experiments reveal an eccentric and indefatigably curious musical mind. To Cyrille, though, they are simply a way of processing the information one gleans from everyday life. He elaborates: "Sound, even though we can't see it, is related to all the other senses. And as human beings, for the most part all of us deal with the five senses. So how do you relate in sound what comes through your senses? Writers and poets experience the same kinds of things except they express themselves in that medium. It's all about trying to bring a form to life, or give life to a form, which is art."

By always helping to elucidate the natural form of a given piece rather than imposing his own style, Cyrille has distinguished himself from a long lineage of "star" drummers in jazz whose virtuosic styles have at times threatened to overshadow the music of their ensembles. "I would think of what I felt was appropriate at the time for the music," Cyrille explains, characterizing his approach to playing with Cecil Taylor, "and that would be my contribution. It was always something that would inspire - I hoped - something that would give the music a voice, an extension of sound through the drum set."

Bright Moments With Andrew Cyrille

The master drummer remembers a selection of his most important recordings

by Aidan Levy

11/15/2016

It only takes a minute of conversation to realize that drummer-composer Andrew Cyrille thinks in a web of free associations as broad and imagistic as his eclectic network of collaborators might suggest.

At 76, the Brooklyn-born, Montclair-based avant-garde luminary recently released The Declaration of Musical Independence, his first album for ECM as a leader, and Proximity (Sunnyside), a duo session with tenor saxophonist Bill McHenry, both albums continuing his legacy as a master of rhythmic call-and-response. On the former, Cyrille forms a new quartet of longtime associates: guitarist Bill Frisell, bassist Ben Street and electronics pioneer Richard Teitelbaum. The album’s subtle textures and free-floating cymbal work distill a varied career spanning hundreds of dates, from postbop to free improvisation and all the way back to Coleman Hawkins. To Cyrille, it’s all in there.

Proximity emerged from a 2014 duo collaboration with McHenry at the Village Vanguard. It builds on a relatively uncommon orchestration explored most famously by John Coltrane and Rashied Ali on Interstellar Space, but Cyrille is a veteran, having already recorded a handful of duos with Jimmy Lyons, Greg Osby and others. The album’s taut 12 tracks clock in at under 40 minutes, with originals, compositions by Muhal Richard Abrams and Famoudou Don Moye and a jocular adaption of Lead Belly’s “Green Corn.” The final six-second track, which consists entirely of Cyrille saying “To be continued,” signifies not only the possibility of a volume two but also a metaphor for resisting finite conclusions-tradition as a form of ellipsis.

In advance of its release, Cyrille spent an afternoon thinking about some of his most influential recordings and a history of political engagement and omnivorous tastes. “Culture is the sum total of the living experiences passed down from one generation to another,” he told me. As an elder statesman of the avant-garde, Cyrille reflected on his musical inheritance and what he has passed on.

The two-and-a-half-hour conversation that yielded this article included some poignant asides that had to be left out, including memories of John Carter, whom Cyrille called “one of the greatest clarinet players I ever heard”; getting rides home in Sonny Rollins’ Karmann Ghia sports car from the Village Vanguard, where Rollins and Cecil Taylor shared a double-bill in the ’60s; and how Cyrille convinced Kenny Clarke to participate in Pieces of Time, a 1984 percussion-only album with Clarke, Famoudou Don Moye and Milford Graves. “There are so many chapters in the life of this music,” Cyrille explained. And he is a part of so many of them.

Coleman Hawkins

The Hawk Relaxes (Prestige/Moodsville, 1961)

Hawkins, tenor saxophone; Kenny Burrell, guitar; Ronnell Bright, piano; Ron Carter, bass; Cyrille, drums

From Coleman Hawkins I learned to be relaxed and to have a certain amount of confidence in what I was doing. There was not very much conversation that went on between us; we’d just met each other at the recording studio. I was very grateful to be in the right place at the right time when the recording date was offered to me, and it turned out to be a classic for me. I must have been about 21 years old.

At certain periods in life, you’re the baby in the band. It’s almost like being a rookie, because I had never played with Coleman Hawkins before. I had only heard him on the radio, and there was some amount of anxiety, the fact that I was playing for this great man and all of these other illustrious musicians. Ronnell Bright at that time was working with Sarah Vaughan.

I was just hoping that I did everything well enough for them to play with me and not say I wasn’t making it. [If they’d said] they needed another drummer, I would have been crushed. I mean, that happens on occasion. You just have to learn to get up and keep on going, but fortunately that didn’t happen to me on that session.

Walt Dickerson

To My Queen (Prestige/New Jazz, 1962)

Dickerson, vibraphone; Andrew Hill, piano; George Tucker, bass; Cyrille, drums

I met Walt because I used to hang out with Philly Joe Jones. Philly Joe comes from Philadelphia, as does Walt, and when Walt came to New York-he had been living in California-he asked Philly Joe about recommending a drummer, and he recommended me. So I met Walt over the telephone, and This Is Walt Dickerson became one of my first record dates.

On “To My Queen,” which was a suite that he dedicated to his wife, Liz, there was a crescendo that I played with mallets that would take us from one section to the next. To me, Walt was a genius who never got his due as far as the press was concerned, and due to not being heard live by many people.

He used very soft rubber-tipped mallets, so you could hear him as predominantly as necessary on recordings, but it was hard to hear him in an acoustic setting. A lot of the other vibes players, like Milt Jackson, Lionel Hampton, Red Norvo and Terry Gibbs, played with much harder mallet heads. Walt would also cut the stems so they weren’t full-length mallets. That was the sound he wanted to get, and it also helped him with speed; he was one of the fastest vibists I ever heard.

Cecil Taylor

Unit Structures (Blue Note, 1966)

Taylor, piano, bells; Eddie Gale, trumpet; Jimmy Lyons, alto saxophone; Makanda Ken McIntyre, alto saxophone, oboe, bass clarinet; Henry Grimes, bass; Alan Silva, bass; Cyrille, drums

I met Cecil Taylor when I was 17 or 18 years old, studying up at the Hartnett [Conservatory]. We’d see each other on the street. Cecil had done some things already, because he’s older than I am by a decade, but we’d see each other in places. So I had met Cecil about eight years before Unit Structures came out.

During the 11-year association we had on a continual basis, maybe once or twice I’d say, “What do you want me to play here?” And he’d say, “Play 5 against 3,” or whatever. But it was never anything that he would listen to and say, “No, I don’t like that. Do this, do that. Do something else.” Across the board, he would just say, “Do what drummers do. You know what drummers do.”

He would give the other instrumentalists notes and things for them to play, but he would never give anything to me. So what I had to rely on was the information that I had accumulated over the years, from the time I had begun playing in the marching band in grade school, the bands that I had played with in high school and then in college. I had done all sorts of things, playing for parties, bar mitzvahs, polkas, learning it in Brooklyn where I grew up, playing with so many different musicians and playing in so many different social variations-Illinois Jacquet, Nellie Lutcher, Mary Lou Williams, Babatunde Olatunji from Nigeria.

So when Cecil presented the music, I just had to go into my laboratory, so to speak, or into my library, and say, “Oh, I think this will fit with this. I think that will fit with that.” And that’s how you hear what you hear on Unit Structures. I had a palette of colors, or rhythms, certain things that came from musics that I had been playing and that some of the things that Cecil was doing reminded me of. So I brought that to the table, and as far as he and all of the other musicians were concerned, it worked.

He would say he would “absorb” the music. Absorption means that the liquid goes through the membrane; adsorption means that the liquid remains outside the membrane. The absorption is what was interesting to him, so the music would move through him and then he would deal with it on that level. He would tell us-me and Jimmy Lyons-that it was our music. It wasn’t just his music; it was our music.

Marion Brown

Afternoon of a Georgia Faun

(ECM, 1970)

Brown, alto saxophone, zomari, percussion; Anthony Braxton, alto saxophone, soprano saxophone, clarinet, contrabass clarinet, musette, flute, percussion; Bennie Maupin, tenor saxophone, alto flute, bass clarinet, acorn, bells, wood flute, percussion; Gayle Palmore, vocals, piano, percussion; Chick Corea, piano, bells, gong, percussion; Jack Gregg, bass, percussion; Cyrille, Larry Curtis, William Green, percussion; Billy Malone, African drums; Jeanne Lee, vocals, percussion

The first time I went to Canada was with Marion. Jeanne Lee was on that gig, and we played in Toronto. John Norris and Bill Smith from CODA magazine, which was [based] in Toronto, invited Marion, and Marion asked me if I wanted to go. When we got back, ECM asked Marion to do that recording when ECM was in its naissance, so we made the record Afternoon of a Georgia Faun.

At that time, a lot of the people that became big stars were young folks in our 20s-Bennie Maupin, Chick Corea, Anthony Braxton. A lot of us had never really played with each other before. Everybody had a responsibility for what they contributed, and we tried to blend so it didn’t come out like the tower of babel.

We went in there with the intention to communicate, understand, and to do what was necessary so the people we were playing with felt good. And that’s what we got. So in that way, it became a classic also.

Andrew Cyrille & Milford Graves

Dialogue of the Drums (IPS, 1974)

Cyrille, Graves: percussion

In the early ’70s, Milford Graves, Rashied Ali and I appeared on a television show on NBC called Positively Black. But prior to that, I knew Milford when both of us were teenagers playing dances in Jamaica, Queens, with a trombone-player buddy of mine named John Gordon, whom I met at Juilliard in [the late ’50s].

The union rules were for musicians to play 40 minutes on and 20 off. But for the dancers, the people had to continue to be entertained, so we’d play 40 minutes, then another band would come on and play. The other band at that time had Milford Graves, who was playing timbales. Maybe we saw each other and waved. Later, I was doing a gig in Harlem with Sam Rivers, and Milford and Don Pullen played before or after us. I don’t think we said anything to each other; they had gone before we came offstage.

Milford was doing something different, and I was moving in the direction of playing arrhythmically, and we had some [shared] feelings about what the Africans had given to the music. Eventually I was at Antioch College with Cecil, and we were invited to do something at Columbia University. Cecil asked me whether I wanted to do a solo or whether I wanted to do something else, so of course I thought about Milford.

Andrew Cyrille & Maono

Metamusicians’ Stomp (Black Saint, 1978)

Cyrille, drums, percussion, foot; Ted Daniel, trumpet, flugelhorn, wood flute, foot; David S. Ware, tenor saxophone, flute, foot; Nick DiGeronimo, bass, foot

Artists relate to things in nature, and sometimes it’s very hard to pinpoint things in a more physically tangible way. How do you play leaves blowing in the wind or on a tree? How do you transfer that to music? Anyway, the stomp was a kind of dance that was going on perhaps in the ’30s and ’40s. But literally, I also thought of the musicians stomping their feet on a metrical beat of the song.

I had heard David Ware with an orchestra that Cecil had put together for a George Wein-produced Newport concert at Carnegie Hall. David was a member of the reed section, and he impressed me. I asked him if he wanted to be a part of this group that I was putting together called Maono, and he said sure. So we got together and went on the road, did a tour in Europe.

Metamusicians’ Stomp came from that collaboration with him, Ted Daniel and Nick DiGeronimo, so that was another memorable occasion. They were dedicated and committed, and they brought what they had to the table.

Butch Morris

Dust to Dust (New World, 1991)

Morris, conductor; J.A. Deane, trombone, electronics; Vickey Bodner, English horn; Marty Ehrlich, clarinet; John Purcell, oboe; Janet Grice, bassoon; Jason Hwang, violin; Jean-Paul Bourelly, guitar; Zeena Parkins, harp; Wayne Horvitz, keyboards, electronics; Myra Melford, piano; Brian Carrott, vibraphone; Cyrille, drums

A lot of the musicians on that recording I had not known before I played with them, like Zeena Parkins, who plays the harp, but I met Butch way before that recording. When I first met Butch, he was playing cornet. I had a gig somewhere, and I decided to do a duet, so I asked Butch. I have a cassette tape somewhere in this house of a duet with me and Butch Morris. There were a lot of musicians at the concert-David Murray, George Lewis, maybe Henry Threadgill. From that concert on, we were musical friends. So when he was putting an orchestra together and recording for New World Records, he asked me. By that time, though, Butch was not playing the cornet as much. When you talk about Butch’s “Conduction,” he had ways of demonstrating a kind of body language for certain things that he wanted with the music, certain expressions, like dynamics, or, for instance, sometimes he wanted emphases on a particular passage. For example, he may have wanted the harpist to play something or the oboist to play a contrapuntal line against the rest of the band. It was very expressive, and of course he would explain to us what certain things meant before we played the music.

It’s almost like when leaders express themselves through a certain instrument. Butch was like an instrumentalist conducting the band, but using his body as the instrument.

Trio 3 & Vijay Iyer

Wiring (Intakt, 2014)

Oliver Lake, alto saxophone; Iyer, piano; Reggie Workman, bass; Cyrille, drums

The formation of Trio 3 goes back about 20 years. Reggie Workman had a group back then called Top Shelf, and he would get these opportunities to play at homeless shelters. We also played jails, because there are opportunities for musicians to do that kind of social work for people who are not able to go to clubs or concerts and are in fixed situations.

Eventually we did a recording for Reggie called Synthesis, with Marilyn Crispell, on Leo Records from England. It was Reggie, myself, Oliver Lake and Marilyn. After that, the three of us got together and did a gig or two. We decided to form a co-op group, and it was based on the premise that there would be no leader-the leader was the music.

As a matter of fact, we’re preparing to do another recording next week on Intakt, a Swiss label. It’s the label that Vijay Iyer was on with us. The next recording will be done without another instrumentalist-just the three of us. It’s not that we don’t put our own groups together or have our own organizations, but when we want to go home, we can go back to Trio 3.

Vijay is a brilliant musician. … He wanted to do what it was that we wanted, and he was very respectful of the age difference, and of the fact that I had been out here doing things before he came on the scene. He’d ask me questions about the scene at certain times, and certain people whom I had played with and he probably knew about through reading or listening. We did a few gigs in the city, and he was the featured piano player, and we will use him again when he is available. We [also] played his music, like the “Suite for Trayvon (and Thousands More),” and we worked on it diligently, assiduously.

Andrew Cyrille

& Bill McHenry

Proximity (Sunnyside, 2016)

Cyrille, drums; McHenry, tenor saxophone

At the Vanguard, that was a week when some of the personnel [in McHenry’s quartet] had to do some other stuff, so we just did a duet one night, and the album’s producer, Max Koslow, wanted it to be documented. [Ed. note: The album was recorded subsequently for Koslow’s Brain Schism Productions.

It’s the same as doing a duet with a piano player, a drummer or a trumpet player. Milford Graves did one with David Murray, Real Deal. I did two duo recordings with Jimmy Lyons in the ’80s, Something in Return and Burnt Offering, and then I did another one with Greg Osby, Low Blue Flame. I never recorded anything with Frank Wright, except some stuff I had done in the ’80s at Soundscape, Verna Gillis’ place. I did a duet with Henry Threadgill, and a concert with David Murray in Canada, also with trombonist Craig Harris.

It’s nothing unusual-Sonny Rollins with Philly Joe Jones, Max Roach and Archie Shepp. You just listen and you play the music with whoever your partner is.

Andrew Cyrille

The Declaration of Musical Independence (ECM, 2016)

Cyrille, drums, percussion; Bill Frisell, guitar; Richard Teitelbaum, synthesizer, piano; Ben Street, bass

This is the first album with this quartet, but the textures that I proposed came from the fact I’ve played with all the participants. Frisell and I did a duet at the Stone and performed with Jakob Bro. I’ve done a lot of stuff with Ben Street with David Virelles and the Danish pianist-composer Søren Kjærgaard. Richard Teitelbaum and I go back the longest.

Richard does synthesized music, and I just find myself playing organic, acoustic drums with these electronic sounds. Richard and I came together through Leroy Jenkins, the violinist from Chicago. We did a record years ago for Tomato Records called Space Minds, New Worlds, Survival of America with George Lewis, and we did a recording called Double Clutch in the ’80s. After that, I used to see Richard in West Berlin before the wall came down, and he had gotten a grant to do some work there. Recently, we did one with Elliott Sharp at Roulette, and before that he and I did a duet at Symphony Space. We had also done some things with Braxton.

Anyway, all four of us came together and we did the recording in Brooklyn. I wanted everybody to contribute something with their own minds and pens, and that’s how we got the music.

Faculty

Faculty A-Z

Andrew Cyrille

Email:

- cyrillea@newschool.edu

Profile:

- Attended the Juilliard and Hartnett Schools of Music and worked with renowned jazz artists including Mary Lou Williams, Coleman Hawkins, Illinois Jacquet, Kenny Dorham, Freddie Hubbard, Walt Dickerson, and Babatunde Olatunji. From the mid-sixties to the seventies, Mr. Cyrille collaborated with pianist Cecil Taylor; was a member of the choral theater group Voices Inc.; and taught as artistin- residence at Antioch College. Mr. Cyrille organized several percussion groups featuring, at various times, notable drummers such as Kenny Clarke, Milford Graves, Famoudou Don Moye, Rashied Ali, Daniel Ponce, and Michael Carvin. Mr. Cyrille has toured and performed throughout North America, Europe, Africa, and the former USSR. He currently is a member of TRIO3, featuring Oliver Lake and Reggie Workman. He has received three NEA grants for performance and composition, two Meet the Composer/ AT&T- Rockefeller Foundation grants, and an Arts International award to perform with his quintet in Accra, Ghana, and West Africa. In 1999, Mr. Cyrille received a Guggenheim Fellowship for composition.

Current Courses:

"All That's Rhythm!" A Chat With Drummer Andrew Cyrille

March 14, 2012

Washington City Paper

Andrew Cyrille is one of the most prominent drummers in the world of avant-garde jazz—-and one of the first few to establish his own sound in the genre. Studying with Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones, and Babatunde Olatunji as a kid in Brooklyn, Cyrille really made his reputation working with Cecil Taylor for 11 years, from the '60s to the mid '70s. He's also a formidable composer in his own right, and will perform his work tonight at Atlas Performing Arts Centerwith a large ensemble of local musicians (billed as "21st Century Big Band Unlimited"), in arrangements of friend and collaborator Mark Masters. Cyrille spoke yesterday to Arts Desk about his approaches to drumming as well as composing, the importance of dance, and some surprising tidbits of drumming history.

Washington City Paper: So you haven’t met any of the musicians you’re working with here. Do you often work like that?

Andrew Cyrille: On occasion. You know, this is more like a studio situation. I don’t know how many studios they have down here, but when I go to L.A. and do the same project with Mark Masters, he usually hires some people that he knows out there that can play the music the way he wants it.

WCP: To what extent is it your music, and to what extent Mark’s?

AC: They’re all my creations. It’s like Mark was an interior decorator that came into my house and rearranged the rooms! And he did a good job. He brought in instrumentation that I hadn’t thought of, and he did some things that I wouldn’t have thought of with my own stuff. I thought it was great, and working with Mark is great.

WCP: I know that right now there’s a sort of flourishing movement of drummer-composers; is that something you have much insight into?

AC: Well, with the college situation—-for instance, I’m at New School—-most of the students that come through there take the full gamut of courses that they have, all of the things that are available and the things that are necessary for graduation. So, in my classes, I give them material that I would like for them to play, and then I also encourage them to bring in their own material. So, on occasion, some of the drummers bring in some of the material that they write. So this might be another evolution in some of the younger generation of drummers who might write and perform at the same time.

WCP: That brings up the question of your own education—at Juilliard, before they had a jazz program. Were you learning more of a marching-band type style?

AC: To some degree, yeah, because I was playing rudiments. The rudiments, really, are just beats for soldiers to move in certain directions. Back up, move forward, drop your arms and get the hell out of here! [laughs] It used to be, if you shot the drummer the battle was over! Because then there were no more signals—-there was nobody to give signals. That’s why they had those big field drums, because the drummers would have to play among the gunfire and so on. You had to hear what was going on. Shoot the drummer, shit is over.

WCP: So how would you go from that, which would be pretty precise in terms of technique, to the free-form on which you made your career?

AC: I don’t care what you play; in any kind of music there’s gotta be some sort of precision, and in the avant-garde there’s gotta be a certain amount of precision, otherwise you couldn’t live.

WCP: Well, let me put it another way: What about that sort of training attracted, say, Cecil Taylor to your sound?

AC: Cecil was a student at New England Conservatory. So he of course learned that kind of Western methodology to playing the piano. Now, you take that, and with then again all of the heredity as far as him adoring Duke Ellington, and listening to Billie Holiday, and all of that other stuff that goes into who we are in terms of being American. So, you find out how do you get to that part of the picture to express yourself? Cecil was very into dancing as well.

I met Cecil in 1957. Now, I had been playing around town, and heard each other, and he’d say “I like the way you play—yeah, man, I like all that Philly Joe [Jones] stuff that you do.” So, I remember I was working for the June Taylor School of Dance; I was playing dance classes, which taught me something else again about playing drums and I think more of that should be done where you have live music and live dancers…so that you can see the music. But I remember that I had a private conversation with Cecil, much the same way that I’m talking to you, and he wanted to know what I thought about playing music. And I was very into dance, having also played with Babatunde Olatunji from Nigeria, so I said, “Well, I think about music as far as dancing is concerned.” Click! [snaps his fingers]

WCP: That’s what he wanted to hear?

AC: That’s what he heard! And that was what more or less got us together, in addition to that he had heard me play with many other people, and he asked me if I wanted to be part of his organization.

WCP: Can you tell me about the music we’ll be hearing at the concert?

AC: Well, it is stuff that I’ve written over the years, and most of it has been recorded. I’m not sure what Mark will choose, but on this demo I did with him out in L.A., we did “Given,” and “The Whirlwind,” and “Proximity,” which is a ballad, and then “Shell.” So we did four, and then I did a duet with a trumpet player on a Monk piece. So perhaps Mark will choose some of those pieces, and in addition I have the charts for “5-4-3-2,” for a piece called “Doctor Licks.” It’s a 6/8 piece that I did as a duet with Anthony Braxton.

WCP: Is it more tonal, or freeform?

AC: It’s tonal, because I usually write in a key. And sometimes we stay in tonality, and sometimes we open it up. But with Mark, it will be more metrically strict, and then with more open improvisation.

WCP: How do you work as a composer? Do you work up from the rhythm when you’re writing?

AC: Sometimes. If I come up with a rhythm, sometimes I’ll then work up notes to put to it. But you know, most of the time, the last thing I come up with is what I’m going to play on the drums. I get all the other stuff together, and then I decide, “Okay, this is what I’m going to play on the drums.” Which is interesting, because composers like Ellington, they would think of drum parts first, and then put other stuff on top of that. The rhythm is the strongest part of the production.

WCP: So where do you start?

AC: Anything. I can think of your personality, how I think of you, and then start from that. I can start with the mood, or start with writing some words and from that I can get rhythm, or a melody. And then I can extrapolate, interpolate, find a rhythm; watch the expressions on your face, how your eyes light up and how you smile, and say “All that’s rhythm!”

WCP: I don’t think non-musicians often consider music in those terms.

AC: Well, look! Anything you see around you, the chair even, had to come out of somebody’s mind! This is just a parallel to that.

AC: Sure. I teach not necessarily from an artistic point of view, and here I’m being really practical, but rather I deal with all of my students on the basis of what they need and want. I don’t impose my own musical or artistic principles on them. If someone’s interested in playing shows, I’ll give him the information I have in that regard; if he wants to play march music, I’ll show him how to do that. As we go along and we get a closer relationship, then I’ll tell him why I do what I do and why perhaps he could think about what I do in regard to himself. My main objective as a teacher, however, is to help the student to find himself, to tap his own resources, to feel comfortable with himself. I’m not interested in producing clones.

NPR

NPR

Andrew Cyrille, born in Brooklyn on November 10, 1939, studied with Philly Joe Jones in 1958 and then spent the first half of the 1960s studying in New York at Juilliard and the Hartnett School of Music. At the same time, he was performing with jazz artists ranging from Mary Lou Williams, Coleman Hawkins, and Illinois Jacquet to Kenny Dorham, Freddie Hubbard, Walt Dickerson, and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, among others. He also played with Nigerian drummer Babtunde Olatunji and worked with dancers. In 1964 he formed what would prove to be an eleven-year association with Cecil Taylor, a gig that brought him new acclaim and established him in the vanguard of jazz drumming.

Starting in 1969, Cyrille played in a number of percussion groups with notable drummers including Kenny Clarke, Milford Graves, Don Moye, Rashied Ali, Daniel Ponce, Michael Carvin, and Vladimir Tarasov. Cyrille formed his group Maono ("feelings") in 1975, with its fluid membership dictated by the forces his compositions called for rather than vice versa. Since leaving Taylor's group, he has also worked with such top-flight peers as David Murray, Muhal Richard Abrams, Mal Waldron, Horace Tapscott, James Newton, and Oliver Lake, was the drummer on Billy Bang's A Tribute to Stuff Smith (Soul Note 121216), notable for being the last studio session of Sun Ra.

An artist-in-residence and teacher at Antioch College (Yellow Springs, Ohio) from 1971 to 1973, Cyrille has also taught at the Graham Windham Home for Children in New York and is currently a faculty member at the New School for Social Research in New York City. His sterling work has earned him a number of grants and awards, mostly notably from Meet the Composer. Additionally, he has an educational video available from Alchemy Pictures.

Source: blacksaint.com

THE MUSIC OF ANDREW CYRILLE: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH ANDREW CYRILLE:

From the album ‘Special People’ (1980 /Soul Note):

Jazz Presents Andrew Cyrille @ The New School for Jazz and Contemporary Music:

Duo Palindrome

Andrew Cyrille & Anthony Braxton--2002:

Music in Us--From: The Navigator--1982:

https://vimeo.com/11322195

https://www.moderndrummer.com/article/december-1981-january-1982-andrew-cyrille-aesthetic-endeavor/

Andrew Cyrille: An Aesthetic Endeavor

by Harold Howland

Modern Drummer Magazine

January 1982

by Harold Howland

HH: What motivated you to study music?

AC: We always had some kind of instrument in the house. My sister got piano and violin lessons, and I remember banging on the piano. My mother belonged to this club which needed a piano, so later she gave the piano away. I was never given any lessons, but I guess that some of the seeds of hearing tones were placed. As most kids do. I fantasized about playing trumpet, drums, saxophone, or what have you. But I didn’t give any serious thought to it.

When I was about eleven, a gentleman named Pop Jansen came to my grade school in Brooklyn, St. Peter Claver. He wanted to revive a drum-and-bugle corps that had been dormant for a few years, and he sent a memo around to all the upper-level classes—sixth, seventh, and eighth grades—asking for kids who wanted to participate. At first I didn’t want to join the corps. It was very strange; I had some kind of reaction against marching up and down the street. I don’t know why, because I had seen a number of parades by that time. Anyway, my friends all joined, and as a result, because I wanted to be with them and because they asked me. I too joined. So it was coincidental that it was found that I had natural hands and an ability or talent to absorb these rhythms and play them. I was dubbed a natural, and in some ways I became the best one out of all the other kids. That’s how it began. Actually, once I began playing, it seemed as though I’d found my voice, in a very roundabout, accidental way.

HH: Do you think that you might have had that same realization on another instrument in another musical situation?

AC: Could have been, sure. I don’t see why not. I don’t know where the predisposition for the absorption of music came from. Again, there were musical instruments around, and my mother used to sing nursery rhymes to me all the time. But how I got into the drums themselves was coincidental.

HH: Did you play the whole drum section?

AC: I would play snare drum primarily, but sometimes I would play tenor drum or bass drum.

HH: Did you enter competitions at that stage, or was it mostly parades?

AC: It started off with parades. Pop Jansen had come from Huntington, Long Island, and he got tired of coming into Brooklyn and managing the corps there, so he asked some of the kids who he felt were the better musicians to come out and join this Catholic War Veterans Post Corps in Huntington. There we began engaging in competitions. I began seeing drum corps in that area like the Hawthorne Caballeros, the Patchogue Black Knights (or something like that; I can’t remember all the names), the Raiders, and others.

Even today, when I see a drum-and-bugle corps that has that precise execution, everybody playing these things in unison, it just sends a thrill through my body that is unexplainable. I can watch those corps all day long; it’s just fantastic to me. I love to hear them play those rudiments, how crisply and clearly they play them, and the kinds of combinations that they get.

HH: Did you have an actual percussion instructor concurrently, or did you learn from the corps masters?

AC: When we started, most of the guys who came down to teach the kids were much older and had been members of the corps that had existed a few years prior to that. They used to take turns showing us the rudiments, how to hold the sticks, and so forth. As happens today in my own teaching, they wanted to give us guidance. I came out of a ghetto neighborhood, and obviously in that situation there is always a kind of concern about most of the young people that they don’t go astray. You want to give the kids something of value that perhaps they can hold onto, and in that way they may learn some kind of responsibility.

Now, in that particular community at that time, once something musical began to happen, other people would learn about it. As a result, jazz musicians began coming to the auditorium when we were rehearsing. They would teach us some rudiments, but at the same time they would begin talking to us about this other music, a different kind of drumming. Fortunately, I was a gifted student, and they would say, “Man. you should come on up to my house, and I’ll show you some more.” A young fellow named Bernard Wilkinson and I would go over and take lessons from Willie Jones and from Lennie McBrowne, and they began playing records by Max [Roach] and the others. It came to pass that Bernard’s sister married Max, and as a result I met Max and began hearing the jazz element more and more.

As I was playing and hearing about the jazz contingency, I was continuing in the corps, and I belonged to a Police Athletic League Corps, the Wynn Center Corps in Brooklyn. Then in high school, along with these corps, I was in the school band. As a matter of fact, the guitarist Eric Gale was in my high school band, a year ahead of me. He and I formed a group with a couple of kids from the school band and began playing dances and so forth outside of the school activities.

In Brooklyn there was a piano player. Leslie Barthwaite, and it was with Leslie that we began really exploring the jazz forms and I began playing tunes like “Billie’s Bounce,” “Lullaby of Birdland,” “Opus de Funk.” and so forth. We began trying to learn the language of jazz; how to improvise. We were playing for community affairs, and in a sense we became young celebrities in the neighborhood. We were only fifteen or sixteen years old, and it was always thought that people who liked jazz were very intellectual and could do something which was really quite different from the regular kind of music. The other kids would always single us out. Even though many of them did not quite understand jazz (just as today’s regular population), it was always something that was prized or looked upon with favor. Then there were certain people who were really into the music, and they could appreciate everything that we did. With that particular unit of musicians, we began meeting some of the older musicians who wanted us to work with them on certain jobs, and that’s how it began to grow.

HH: When did you begin studying with Philly Joe?

AC: I met Philly Joe Jones when I was about sixteen or seventeen years old. Again, all these things were happening at about the same time. Once I became interested in the drum, I had a choice to make as to how I was going to live my life, and I used to fantasize about how I was to make a living if I had to be a musician. I knew that I had to learn the discipline, and the best way to do that was to be involved with the people who were doing it. I met Joe after I met Max. And it was really Joe who took me under his wing and would talk to me about drumming and about music. I had only one or two actual lessons where we would pick up drumsticks and play: most of the time it would be just conversation. Joe would let me go to a lot of those recording sessions he was on. And sometimes on jobs he would let me sit in with the older musicians—that was an experience!

HH: He does give the impression of a protective father figure, a teacher of life.

AC: That’s the kind of guy he is, and I used to hang out with him often. I was at his house in Brooklyn a number of times during the week, and we would go into Manhattan.

Max was another kind of figure. I would see Max and we would talk and I used to watch him practice, but Max never gave me any direct lessons. Every now and then something would spill over, but Joe was the one who focused in on me and made suggestions. I’m not saying that Max was unfavorable towards me: it just never happened that way. Max did let me sit in on his gigs a couple of times. As a matter of fact, much later Elvin let me sit in with Coltrane. Things like that don’t happen very often.

Once Joe asked me to be his protégé. Even at that time I had a sense of identity and individuality, though, and I said, “Well, no, man, I don’t want to be a protégé.” But I love Joe a lot, and quite naturally, there are probably things that I do that reflect some of the things that he does.

HH: How long did you continue playing in corps?

AC: Until I was about sixteen or seventeen.

In my last year of high school I quit the school band and really started playing professional gigs with people like Duke Jordan and Cecil Payne.

I was pretty lucky that way. I don’t know whether it was because I had the singleness of purpose, whereby I wanted to learn this music and would find myself in these good musical environments, or whether it was just by some stroke of luck that I was there. I guess that sometimes our actions influence our luck.

HH: It seems that if one puts enough energy into something eventually he will be in the right place at the right time.

AC: Right, sure.

HH: What drew you to study European classical music at Juilliard?

AC: I was at St. John’s University before I went to Juilliard. I remember that one night there was a university talent night. I decided that since I didn’t have a band I would do a drum solo, and I went up and played for about forty-five minutes. I think that was the first time I ever did a drum solo. After it was over, people began saying to me, “What are you doing here? You should go on and develop a career in music!”

HH: St. John’s didn’t have much of a music department?

AC: No, I was a chemistry major. I had to think about how I was going to make a living, and at seventeen or eighteen I didn’t think that I wanted to spend the rest of my life with a music career. It was a possibility, but I had assumed that I wanted to learn chemistry and make that a profession. What I found when I was in college was that I began working nights with some of these names, and it became a conflict for me to do my scholastic work and at the same time do the work that was necessary for me to play this music on a very high level. I’m one of these people who, if I’m going to do something, I would like to do it well rather than be an also-ran. So if I had to be a chemist I would have really wanted to be a doctor of philosophy and to be on a high level of performance there. I said to myself, “Well. I could take both of these disciplines into infinity, and I have to decide really which one I want to do.” I liked chemistry a lot, but I loved music. That’s really what the difference was so I decided to give music a shot.

I took the audition for Juilliard and I passed and was accepted. Then I spoke to the dean at St. John’s and said. “Well, look. I was accepted at Juilliard.” and he said. “A lot of people are not accepted there, and it’s an excellent music school, so what you can do is go there and try it. And if you don’t like it. You’ll always he welcome hack here.” So I went to Juilliard and I never looked back.

To answer your question more directly courses, we would bring jazz records into the listening library. There would he a group of us around this table with the earphones on, and every now and then something would happen musically on the record and all of us would crack up and make some noise, and the librarian would come over and say. “Shsh!” Afterward, of course, I’d have to do these other things for my assignment, and I’d be listening to records by Mendelssohn and Elgar and so forth, and sometimes I’d be so tired that I’d fall asleep during the middle of the record. When I’d wake as to why I chose a place like Juilliard. it was because I wanted to learn more about jazz. To my disappointment, that was not really in the curriculum.

HH: That’s why I asked. It would seem that one would go there to study every kind of serious Western music except jazz.

AC: Right. At that time it was really about European classical music and its derivatives. I went, and I learned, of course, but I was disappointed, because I really wanted to learn about Monk and Bud Powell and Bird and Max and all those people, and it just wasn’t there.

I remember that some of my classmates were Gary Bartz, Grachan Moncur, John Gordon, and Benny Jacobsel, and when we would have to go listen to the classical records for our ear-training up the record was over, so I’d have to start listening all over again! In class the teacher would just put the arm down anywhere on the record and ask you who the composer was and what movement it was.

Anyway, that was my experience at Juilliard. I was disillusioned to some degree, and I wanted to learn really how to play the music. While I was there I did meet some musicians like Bobby Thomas, who was a percussion major, and bassist Morris Edwards, who gave me the opportunity to play with such people as Nellie Lutcher, Illinois Jacquet, and Mary Lou Williams. At the same time I began really getting experience with some of the masters, and then I knew that I had to leave Juilliard. It was always a feeling among musicians that if you stayed there long enough, eventually you would lose your feeling for jazz; that they would somehow alter its techniques and you wouldn’t be able to swing anymore. Whether that was true or not, I had that impression in my head.

HH: How long were you at Juilliard?

AC: A little over a year.

HH: Had you not looked into other schools where jazz might have been in the curriculum?

AC: No, I didn’t know of anyplace. I guess. The students at Juilliard always used to compare themselves with the students at the Manhattan School of Music— those were the two major schools of music in New York—and they would say that Manhattan was a better school for people who wanted to play jazz. But they would say. on the other hand, and I don’t know why. that the kids who went to Manhattan were programmed to be teachers rather than performers, and that at Juilliard it was the other way around— but they were performers in the classical tradition.

I remember that my teacher at Juilliard, Morris Goldenberg, would always say to me (in a sense he had protégé attitudes also) that when you went to work with some symphony orchestra in Denver or Idaho or wherever, they’d know as soon as you picked up a mallet or a set of timpani or snare drum sticks that you’d studied with Morris Goldenberg. Even though I didn’t say to him that I didn’t want that to happen to me. I had an aversion to it. His main idea was to program me for the symphony or for staff work in studios.

I didn’t look around for another school because I assumed that most of them would be generally the same. Then again, other good schools like Eastman and Curtis were outside of New York.

A lot of the professional jazz musicians with whom I began working had negative things to say about learning in the academic system, and they would say, “Well, man, the best thing for you to do is just to get out here and play and learn from people like us who have been doing this.”

I knew, though, that I needed to further my studies, so as time went along I found another school, a private school on Forty-second Street which is now defunct, called Hartnett. It was there that I began studying harmony and theory that was geared more to jazz, and I began playing with a big-band there. George Robinson was one of the theory teachers, and after the school closed down. I continued studying with him privately, which is how I got the foundation for my ability to compose.

I thought that I needed some more training in reading drum music, so I went looking again for Morris Goldenberg. Morris was teaching privately as well as at Juilliard, and I didn’t want to re-enroll in the Juilliard course. I found him at his studio and told him what I wanted. He was concentrating really on mallet work, so he said, “Well, look, there’s a guy who has studied with me for a number of years who is very good,” and the gentleman to whom he introduced me was Tony Columbia. I remember that when I was at Juilliard, Tony was a few years ahead of me and I’d met him.

Tony was the one who began applying what we would learn in those drum theory books to the trap set. I don’t know whether it still goes on, but there’s another division in the music schools; when you’re in the percussion department, you learn how to play snare drum, but you don’t learn how to play snare drum in relation to the trap set or in relation to popular music; you learn it according to classical music. There’s a whole other way of interpreting those notes for the drum set, in relation to the music that we know to be American. Tony Columbia was focused in on that application, making it sound legitimate in relation to the set. I studied with him for about a year, and he opened up a certain thought pattern to me.

HH: How do you think American music education relates to what Cecil Taylor calls black methodology?

AC: Well, I think that all of it is in us, that most definitely we have European influences; we’re part that as well as we are part African culturally. In this country, black methodology has been, to an extent, a synthesis of what has been available to us. For instance, black people took the saxophone, the trumpet, or the snare drum as it was in their communities and did with it what had been handed down to them enculturally and developed the music that we know, called Afro-American music or black classical music or jazz, with the European influence. In Juilliard you learn about chords and about reading and so forth, but you can take those very same things and swing them, and give them another kind of feeling, another kind of inflection. Those things can be used or reapplied in a way that is more suitable to your artistic direction, more meaningful in your environment. I feel that if I had to go back now to a school like Juilliard and study further it would be more relevant because I know what I want to do and have established myself. There’s nothing wrong with getting more information about musical devices, the point being that I could shape them to function for my needs.

HH: Which of the three main influences—African, European, American—do you think plays the largest part in the development of jazz?

AC: Well, I would have to think that it would be the African because of the way the music eventually came out. It’s improvised; you have all of these cross rhythms; you have all of the antiphonal, call-and-response factors; you have the vocal inflection into the instrument to make it reminiscent of the human voice, so that it relates to the talking drum (a lot of people may not be aware of that). All of the ingredients that go into the making of African music go also into the making of jazz, but with the European means of instrumentation, chord structure, and so forth. We drummers use the rudiments— paradiddles, ratamacues, and so forth— in so many different ways within the sticking patterns. The idea is to make it sound or feel more natural to yourself, and because of the encultural influences in how the music survives, I think that in its intrinsic methodology here in the U.S., jazz is more related to Africa than to Europe.

HH: Do you consider yourself strictly a jazz musician, and does the term “jazz” mean the same thing now that it has in the past?

AC: As long as I have heard the word “jazz” it has meant essentially an improvised music, composed, organized, varied, and performed spontaneously. The people who began laying down musical ideas to me were black, and the idea was always to be able to swing. When we talk about swing as it always has been, we usually think of some kind of four-four metrical pattern (now you might play a three or maybe even a seven), hinging on the proverbial dotted eighth note and the sixteenth. To some degree this has been a point of debate even within the creative community of people who play, say, bebop, and people who have gone on from there and tried to do something else. Whether you want to call the music jazz, I think, depends on the feeling that you get when you play. The idea was never to make the music feel stiff or rigid or totally cerebral. Even when I myself, and I have to speak for myself, do something that may be considered abstract, I always try to inject it with a feeling of swing, or at least to impart some kind of feeling of levitation; that is, people get some kind of an emotional and organic stimulation as well as an intellectual stimulation. In that light, I would say that the word “jazz” could still be used but you have some people who would dispute that simply because now the rules and concepts of making the music have broadened. I may not play a four-four metrical pattern; it may be ametrical. It might be as I’m talking now, which very often is how I think about what I do, as a conversation; I don’t talk in four-four or six-eight or nine-eight or whatever. If people get something from the way I deliver what I say, then to me that has an organic, emotional appeal; then if they can move their bodies as well, then it imparts also a kind of levitation.

The problem now is that when you think about the word “jazz” and listen to the commercial radio stations, what you hear is almost rock. And then the definitions have widened, so you will find some jazz musicians, a lot of the guys from Chicago, for instance, who will say that they’re not really jazz musicians; they’re “creative” musicians. It’s funny; as the appellation continues to be applied to so many different kinds of music within what we know to have come from, say, ragtime to dixieland to swing to bop, the musicians still accept it; but there hasn’t developed one singular term that everyone can feel comfortable with. Sometimes I feel more comfortable with the term “creative music,” but you have creative musicians who get their impetus from the European classical tradition, which is not necessarily involved with the African tradition as well. So when people ask me what kind of music I play I usually come out and say, “Jazz,” because that almost automatically stereotypes or directs them in a certain area and there are no more questions. If you say, “Creative music,” they might say, “Well, what kind?”

HH: Tell me about Voices Incorporated.

AC: Voices Incorporated came about through drummer Andrei Strobert, who had been working in their show. He asked me to sub for him with this show, then he left, and I took over the chair. At that time it wasn’t Voices Incorporated; it was called The Believers. This was during the sixties, and they were trying to raise the level of black consciousness through musical theater. I had met this other African drummer, Ladji Camara, who had come here with the African Ballet of Guinea. He had worked also with Olatunji, and he and I happened to be the drummers who started off and ended this show. The show would start in Africa to show the development and gradual evolution of black people as happened later here in America. The Underground Railroad, slavery songs, songs about freedom, gospel songs—the whole scenario was based around music. After The Believers closed, Voices Incorporated was a group of the same people who continued doing these kinds of shows around the country. It was another great experience for me because there I had the opportunity to be a drummer playing trap set with trained voices. Most of the people who sang in that show were trained operatically, but they would sing black spirituals. There’s a connection, as I was saving before about encultural influence; you have spirituals which are a development of New England hymnody and African rhythmical inflections. The people go to schools like Juilliard and get operatic training, but when they begin to sing spirituals it comes out another way; you have the bent notes, the dropping of the voices at the end of words, shouts, field hollers, and so forth. It was a great thing that they could relate to and hear my drumming so easily.

HH: Were you the only instrumentalist?

AC: Usually there would be a piano, but sometimes it would be just the voices and me. It was very strict harmony, the chords being stacked as we know them to be, in thirds, sometimes with the higher functions.

In between I was making jazz gigs, but Voices Incorporated was a way for me to make some money and at the same time be in something which I thought was artistically viable and in keeping with my other goal, which is what I’m doing now.

HH: Surely that experience helped to prepare you for the completely natural ensemble you have with Jeanne Lee and Jimmy Lyons. In most situations, if you told someone that your band consisted of voice, saxophone, and drums, he’d say, “Well, there’s something missing.”

AC: Right, yeah. Here we are, talking about education. A lot of my education has been empirical. Conservatories are just that; they conserve what people learn over the years through experience. So even though I haven’t gone completely through a conservatory in the academic sense, I’ve gone to a conservatory of life, and I probably couldn’t learn how to do these things in a school. I am out here living a life heavily influenced by politics, economics, sociology, and so on. Playing art that is relevant to the times—which is invaluable experience. I’ve had the ability and the good fortune to be involved with people who allow me to do my work.

HH: Do you think that the current state of jazz education in America is healthy?

AC: Well, I haven’t been involved in a real academic setting since I was out at Antioch with Jimmy and Cecil back in the seventies, so I can’t say that I think it’s really better or worse. But from what I hear, there are more programs going on around the country. I understand now you are able to get degrees in “jazz.” so I would say that perhaps on a comprehensive basis, with the establishment becoming more involved with the music, maybe it is getting better. I would say too that the Percussive Arts Society International Convention in 1979 [which featured Andrew as a performer-clinician], incorporating styles from the other disciplines of drumming, addressed itself to a larger area of education. There are people who are trying. Then again, this country has so many universities and schools that probably, if you really looked at the percentage of jazz education, it would be less than a drop in the bucket.

HH: Your most famous gig as a sideman was with Cecil Taylor. Tell me about that.

AC: I met Cecil back in 1958, up at Hartnett. I met him through trumpeter Ted Curson, who had a rehearsal with him and asked me to come along and meet this guy who plays piano in a very unusual way. When I got there, Cecil asked me if I wanted to play, and I played with him on that occasion. We hung out and became musical acquaintances and, as time went on, observed each other on the scene. Cecil would practice and hold rehearsals at Hartnett, and finally in 1964, when Sunny Murray left Cecil’s band. I was there. Cecil knew about the work that I had been doing with people like Walt Dickerson. Ahmed Abdul-Malik, and Bill Barron. I had made records with them as well as with Coleman Hawkins. Cecil would see me and we always had a good rapport. So Cecil asked me to be part of his organization, and I said. “Sure!” That was ’64, and the relationship lasted until ’75.

HH: How would you describe your personal relationship with Cecil?

AC: It was one of great rapport. We understood each other as black individuals in an American social system that sometimes has been very unfair and unjust to individuals like ourselves.

Often when I’d be around him I would have this feeling of peace and tranquility. He was someone I didn’t have to struggle with, explain or demonstrate to, or be always on guard against as to what I was, what I felt, and why I was playing the drums the way I did.

It was a total relationship in that I worked with him on almost all of his gigs. But very often we would maybe only work two or three times a year; I’d be doing other things. During this time I was working with Voices Incorporated and so forth. I was also working with dance classes, which was another invaluable experience.

HH: That seems to be one of those New York phenomena, that a drummer has the accompaniment of dance programs as an opportunity which is not nearly so available in other cities.

AC: Which is unfortunate, really unfortunate. Just as you can relate the voice to any other instrument, dance is another manifestation of music, almost a twin to rhythm. People don’t dance unless they dance to rhythm. Why can’t there be more drummers and dancers who get together? It’s another whole area of exploration in the arts, the visual contact as well as the auditory. Some of it’s fantastic because when you find a dancer who can hear and utilize his or her body the way that an instrumentalist can, it’s almost like watching the musical development itself. You can exert the same kind of creativity with a dancer that you do with other instruments, but you have to think a little differently. Dancers organize their movements a little differently from the way we organize sound, so you have to find a way to play the music so that it relates to their artistic science of form and count. Of course, in other cultures, such as India and Africa, dance and drumming go almost hand in hand. Here, in some ways, it’s been more widely separated, probably because of the European heritage of the drum in relation to the other instruments of the symphony orchestra.

HH: To what do you attribute, and how would you describe, the widely acclaimed musical rapport which you shared with Cecil?

AC: From my own point of view, I would have to say that my role as a drummer in the organization sometimes was, as it was even before I worked with Cecil and as it continues to be, interpretive.

I was always told that the role of the drums was one of accompaniment in relation to the soloist. With Cecil, however, that particular concept changed a bit. Sometimes, yes, I would be accompanying, but other times I would be soloing simultaneously with whomever it was who was actually the featured soloist, listening to what was happening all around me. You would hear, therefore, this density of rhythm and sound coming from the Unit. You might ask, “How did the audience know when a particular person was soloing if everyone else was soloing?” Well, the person who was soloing would simply raise the level of consciousness and go one notch higher in terms of projection. In other words, he would project his ideas more strongly, setting dynamically the direction and shape that the improvisation would take. That’s how we solved that problem among ourselves. When we were playing and it was time for somebody to solo, there was no doubt about it because he was the individual who would take over.

I would think of forming contrasting shapes, sounds, and rhythms by employing various timbres from the trap drum set. I would think of antiphonal phrasings. It was a push-pull concept that would suggest and absorb the ideas being presented. Ninety-nine percent of the time Cecil would not tell me what to play; that was left wholly up to my own interpretation. This was an excellent situation because it gave me an opportunity to form my own sound within the language. It also presented a challenge in that I had to measure up to whatever else was happening, playing something that was interesting to the others as well as to myself. We had a feeling of continuity, rapport, and support.

Sometimes I would project certain feelings and pulses by using parts of the drum set in a particular way. For example, using the ride cymbal primarily, with alternate-hand accents around the set to give a feeling of floating, levitation; or rapid, high-tension rhythms with incredible energy to generate force. At other times the opposite was the case, and I would suggest space, brevity, and peace, giving the feeling of being soothed. Whether the tempos that I played were exceptionally fast or very slow or in between, we struggled for sonic beauty with clarity of thought.

HH: How did your role as a percussionist relate to Cecil’s as a player of what might be considered a stringed percussion instrument?

AC: I would think of him and Jimmy and whomever else was in the Unit as part of an African drum choir, where each individual found a place for himself that was natural, unobtrusive, and adaptive to what was happening. There’s always space, and you can always find your place.

HH: You and Jimmy were together throughout that association, correct?

AC: Right. I met Jimmy when he was with Cecil, at Hartnett. Actually, I met Albert Ayler the same day.

In terms of relationships, let me say this without any reservation: I hold Jimmy Lyons, who has worked with me as well as with Cecil for over eleven years, in the same high regard in which I hold Cecil. Jimmy hasn’t received the kind of recognition that he deserves. He is a great, great musician and a true friend. We’ve had fantastic times together, and I’m sure they will continue.

I stopped working with Cecil consistently in ’75. I’ve done two jobs with him since then, one in ’78, a Newport gig, and in ’79, a week at Fat Tuesday’s in New York City.

I feel that things in life are circular, and maybe from time to time Cecil and I will get together, but it’s nothing whereby he can feel that he can depend on me on an “on-call” basis. If he wants to use me and I can make it, then I will, but it’s not as though if I have something that may conflict I won’t choose to do the other thing. I have other priorities now.

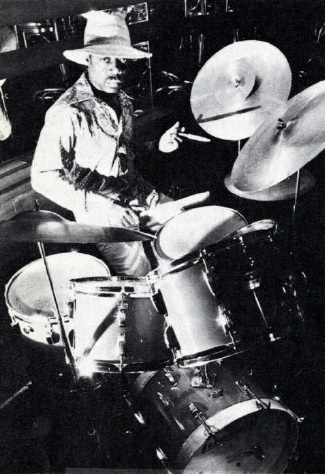

HH: What is the background of the Dialogue of the Drums?

AC: That’s another one of those situations in life whereby you meet people, find out that there’s certain rapport, and say, “Well, let’s get together and plan to do something,” and in time it happens. I met Milford Graves about 1959 or 1960.I was playing a dance in St. Alban’s Queens opposite another band, and Milford was the drummer in the other band. I remember that when I walked in they were playing, and he was on timbales. We probably just said hello to each other. But as time goes on, because you are of a particular frame of mind, you begin meeting people who are thinking more or less in the same direction.