December 11, 2011

To mark the 73rd birthday of piano maestro McCoy Tyner, I’m posting a feature article about that I had the opportunity to write for Jazziz in 2003. I’ve attached below the verbatim transcripts of the two interviews that I conducted for the piece.

* * *

Thirty-six years after the death of John Coltrane, with whom he famously played from 1960 until 1965, McCoy Tyner remains a jazz icon. The 64-year-old pianist reinforced that stature one night last March, during a thrilling set with vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson, bassist Charnett Moffett, and drummer Al Foster at Manhattan’s Iridium in the middle of a week’s stand supporting Land of Giants (Telarc), Tyner’s superb 2003 release.

“There’s a prayer that comes through as the music is being played,” Hutcherson noted during a subsequent conversation. Hutcherson, who first recorded with Tyner in the mid-’60s, when both were Blue Note artists, is perhaps Tyner’s most inspired foil. “You’re vulnerable, naked. McCoy knows how to mold the group and make it sound the way it should. We just fall in and then we’re swept away. He throws out so many suggestions and then asks what you think. If you catch it, you catch it. He implies the color or the one note throughout a sequence of chords that says, ‘Play me, play me again!’ — and with that starts the prayer. After every set I’ll turn to him and say, ‘Boy, you were really praying.’ He’ll laugh, but he understands exactly what I’m saying.”

When I paraphrased Hutcherson’s remarks to Tyner, he laughed. “Did Bobby say that? I’ve got a name for him: Rev!” As we sat on the backyard patio of his booking agent’s brownstone office on a bright, 90-degree July afternoon, the pianist looked clean as a whistle in a contoured black sports jacket, a textured, blue silk shirt, a white patterned silk tie, and white linen pants. He wore his hair marcelled into short neck-clinging braids that didn’t betray a speck of gray.

“I don’t want to sound overly poetic,” Tyner continued, on a serious note, “but you do feel cleansed when you’re done playing. I pay homage to the Creator for what he has given me and all of us. But I’m not preaching. If people hear things in my music and identify with them, that’s good! The music speaks for itself.”

I mention that Hutcherson’s description of how it feels to make music with Tyner evokes the collective catharsis that Coltrane stirred in audiences on a nightly basis during the ’60s. “It was a spiritual experience every night,” Tyner reflects. “We were giving everything we had, and you never knew what would happen. There was no time for ego.”

Tyner stands out among professional contemporaries because of his grounded persona and the relentless consistency of his career. He is no stylistic eclectic in the manner of Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, and Chick Corea, all of whom continue to follow the example of their former employer, Miles Davis, in seeking new worlds to conquer. Rather, Tyner’s path more closely resembles the High Modernism aesthetic of Coltrane — and the likes of Cecil Taylor, Steve Lacy, and Keith Jarrett — who coalesced and refined diverse influences into a holistic musical conception.

Like all of the aforementioned, Tyner possesses a vocabulary of global dimension. Core sources include Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Art Tatum, and Coltrane. Every other year or so, he releases a new recording, invariably acoustic, on which he reframes elements of his long-influential style in different contexts. Every important jazz pianist from the mid-’60s until the present — including Hancock and Corea — has assimilated his homegrown system of navigating harmony with fourth intervals. For improvisational fodder, he deploys an exhaustive knowledge of the rhythms and scales of Africa, Cuba, Brazil, and India, as well as the chordal structures of the American Songbook. And he articulates everything with soulful cadences drawn from the Afro-American urban-church and blues cultures of his youth.

Tyner differs from his distinguished contemporaries in that he has never shrunk from expressing his tonal identity within the framework of his roots in mainstream jazz. Perhaps that predisposition — in conjunction with a pronounced lack of personal eccentricity and the middling skills of his working trio of the latter ’80s and much of the ’90s — explains why, despite the fact that Tyner commands universal admiration among musicians and retains what market researchers call a “high recognition quotient,” many “progressive” connoisseurs perceive him as a conservative figure. But no such considerations deterred several thousand New Yorkers — young and old, and with a larger African-American contingent than usually turns out for jazz events south of 96th Street — from packing a cavernous concrete space on the south edge of the Lincoln Center acropolis, called Damrosch Park, on a humid August night for a free concert by Tyner’s trio, with guest flutist Dave Valentin.

Stimulated as much by the crowd’s support as by the inventive accompaniment of bassist Charnett Moffett and drummer Al Foster, Tyner stretched out through seven originals on the trio portion. With unerring logic, impeccable touch, and an astonishingly powerful left hand, he conjured yearning, inflamed melodies from dense harmonies and complex polyrhythms, ornamenting his designs with luscious voicings and elegant figures. He executed every idea with magisterial authority while sustaining the aura of instantaneous creation. For all the baroque grandeur of the lines, he stripped every idea to essentials, imparting an air of poetic inevitability to the arc of each improvisation. With Tyner as the attentive moderator, the trio transcended notes and beats and achieved seamless musical conversation, rendered in cogent sentences and paragraphs.

BREAK

Unfailingly amiable and gracious in conversation, Tyner is not one to expound on the particulars of his art. However, his colleagues are happy to fill in the gaps.

“McCoy is a consummate accompanist,” says tenor saxophonist Michael Brecker, who won a Grammy for his solo on Coltrane’s “Impressions” on Tyner’s 1996 album, Infinity [Impulse!]. “He gives you a lush, wide-open cushion, and you have a feeling of complete freedom. If I hint at building a harmonic tension, he’ll be there instantly, almost like he’s reading my mind. It’s powerful to hear that quality of tension-and-release on the great Coltrane records, but to actually experience it first-hand is incredible.”

Some of Tyner’s most efflorescent playing has occurred in Afro-Cuban and Brazilian contexts, most recently on the prosaically titled McCoy Tyner and the Latin All-Stars [Telarc, 1998]. “McCoy is a master of rhythm,” says trombonist Steve Turre, a regular participant on such projects, who has also played in Tyner’s big band since 1984. “A lot of guys don’t commit to a rhythm; everything is kind of abstract. But McCoy never floats. Rhythm permeates everything he does.”

“Rhythms have languages, and even if you don’t know the language, you can sense what it is and play it,” says bassist Andy Gonzalez, recalling an occasion where the pianist performed as a guest with Libre, the unit Gonzalez co-leads with iconic timbalero Manny Oquendo. “I asked McCoy if he wanted to play Latin-jazz tunes with [chord] changes or montunos, and right away he asked for the montunos,” Gonzalez says, referring to the triplet-based vamps that counterstate the drumbeats of clave. “I had Charlie Palmieri play a real down-home, Cuban-dance-rhythm montuno at him, and it was fascinating to hear him answer it with his own chords and rhythmic feel. It was effortless. Montunos are related to the kinds of pentatonic modal scales that Coltrane was working on, and improvising in those kinds of modes is really McCoy’s forte. That’s very African, very deep-rooted, getting to the very beginnings of music.”

Gonzalez mentions a late ’60s conversation with Tyner during a set break a Slugs, an infamous club on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The pianist revealed that a window opened for him after a concert at Harlem’s Apollo Theater when Coltrane, sharing the bill with Machito, borrowed the Cuban bandleader’s bassist, Bobby Rodriguez to fill in for an absent Jimmy Garrison. Tyner confirms this. He also emphasizes the impact of Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji, to whom Coltrane was close, on sustaining his own awareness of African roots. But African music entered Tyner’s consciousness in the early ’50s, when a Ghanaian drummer named Saka Acquaye arrived at Philadelphia’s Temple University to study political science, and earned tuition money by teaching African rhythms to local drummers at a dance school that employed the teenage pianist as an accompanist.

“I fooled around with the drums, but the joints of my fingers started to hurt, and I had enough sense to stop,” says Tyner, who began formal piano studies about a year before the drummer came to town. “I observed Saka and learned how to connect one rhythm with another, how to operate with different layers of rhythm. I was fascinated with the drums even before I met him, and I’ve incorporated those rhythms into my style along with other things.”

Tyner acknowledges regarding the piano as a kind of extended drum. “Thelonious Monk did, too. Monk was very percussive and rhythmic. He’d do stuff that was off-rhythm or against the rhythm or tempo of the song. It was miraculous to me how he could interject so much feeling and depth into such simple ideas. It wasn’t about how many notes he played. It was the immediacy, the spontaneity of the situation. He taught me that what’s important is what you do with the idea you’re trying to portray – the will to push the envelope.”

While Tyner’s ensembles at Damrosch Park and Iridium played with a palpable attitude of freedom, critics cite numerous ’80s and ’90s recordings and performances with less resourceful partners on which his playing sounds attenuated and rudimentary, as though he felt responsible, say, for stating both the drum and piano parts. “I have a mixed personality in that respect,” Tyner admits. “I have a controlled sense of experimentation. I go outside, but there has to be something to work with. I conceived one tune on the new record as having no melody; we just used tonal centers, moved from one tone, one sound, one cluster, to another. I had that experience playing with John. But I use it when it’s appropriate for me, not as a main way to express myself. It’s a tool, and that’s all. I’m not trying to prove anything to anyone, and I don’t want everything to be predetermined. It’s not artistic.”

Perhaps that sentiment explains why, last year, Tyner decided that his two-decade association with bassist Avery Sharpe and drummer Aaron Scott had “served its purpose for that time period” and formed the current rotating unit with bassists Moffett and George Mraz, and with either Foster, Eric Harland, or Lewis Nash on drums. “You can’t get so attached to someone that you restrict them from doing what they ultimately have to do,” he explains. “I had my previous trio for a long time because I hadn’t heard anyone — and I knew there were guys around — who could really do what I was looking for. Then they came along. The right thing always comes around eventually.”

What precisely is Tyner looking for? “I like guys around me who are willing to take chances, explore and feel the situation at hand, as opposed to, ‘Oh, I can’t do this’ – but on a level of professionalism that stands out. It’s not good for an artist to feel that kind of fear. But it’s very personal. You’re asking a person to be honest with themselves and not be afraid. And most of us have fears and sometimes we’re not honest! We spend a lifetime, or at least we should, trying to find out who we are. It’s crazy to stick with something forever.”

The ethos of risk taking was customary during Tyner’s years with Coltrane and was a key component of his formative years in Philadelphia. A late starter, he studied classical music formally for two years before putting aside the books and finding his own solutions in functional situations. “I developed facility because I practiced all the time,” he says. “And the dancing school taught everything, so I heard a lot of music there. I studied things by Bud Powell like ‘Celia’ and ‘Parisian Thoroughfare,’ and I heard Monk’s records. Bud and Monk were my main influences — and John, of course. But I listened for the individuality, not to copy. Monk respected you if you had your own direction. A lot of things come out of so-called ‘mistakes.’ In reality, nothing is a mistake; it’s how you shape music, how you resolve it.”

Like trumpeter Lee Morgan, a childhood pal in Philly, Tyner learned to think on his feet in the crucible of live performance. He played with blues singers and R&B bands, worked fraternity dances and graduations, and, with Morgan, worked two summers in the no-holds-barred environment of Atlantic City. By his late teens, Tyner was a first-call pianist for national bands passing through town, and he spent memorable weeks with, among others, Max Roach’s quintet with Sonny Rollins and Kenny Dorham, and with a unit co-led by Red Rodney and Oscar Pettiford. By then, he’d been playing several years with local trumpeter-composer Calvin Massey, bassist Jimmy Garrison, and drummer Tootie Heath. Massey introduced Tyner to Coltrane in 1956 after a matinee job at a neighborhood spot called the Red Rooster.

“When guys from the older generation saw you had some talent, they’d call you for gigs and show you tunes,” he recounts. “And you learned by accompanying. Guys expected you to be supportive, and I learned a lot that way. That cocky attitude of ‘I can’t wait to get my own band’ didn’t fit in at all. The standards were very high. Appearance, presentation — you had to be on point. I came up in an era when Art Blakey would say, ‘People see you before they hear you.'”

I ask if his mother, Beatrice, a beautician who kept McCoy’s piano in her shop, was the source of his fastidiousness. “My mother had a lot to do with everything in my development,” he replies. “She was very elegant, not in terms of her clothes or attitude, but just her demeanor. She was honest, personable, and caring, and people loved her. She loved music, and she’d let me know when anything came up that she thought would interest me. We had a very close relationship. I took her to cotillions. Once she wanted me to play a concert at Mount Olivet Baptist Church – not church music, but the songs I had learned from my instructors. She wanted me to put on tails, and I did.”

I thought of that image toward the end of the trio portion at Damrosch Park. After a venturesome a cappella introduction by Moffett, Tyner — who did not remove his navy, double-breasted blazer throughout the high-energy set — launched into the thunderous theme of “Manalyuca,” carving out the melody with his left hand and comping with his right, using them interchangeably in an improvisation that built to an immense crescendo. He gave way to Al Foster, who, Max Roach-style, stated the design of the melody and transitioned into improvised variations on a march. Tyner re-entered at the peak he had reached before desisting, then, through a gradual decrescendo, reached the final melody statement. He immediately launched into a boogie-woogie figure before embarking on formidable two-handed blues variations that foreshadowed a deeply swinging, medium-tempo excursion through “Blue Monk.”

As at Iridium a few months before, he reminded the witnesses precisely why his name means what it does in the jazz timeline.

“I only did what I was supposed to,” Tyner says of his career. “I mean, people think it’s fabulous, and when I look back at my musical history, I’m thankful for the opportunities I’ve had, and to have risen to the occasion. I like simplicity and balance, and I’m dedicated to music, but it doesn’t consume my every minute. I don’t need to be put on a pedestal to feel good. But I don’t downplay my contribution or creativity. I’m confident, but I don’t allow myself to feel I’m in command of everything. Confidence is a tool to get where you want to go. I feel I did the best I could. And I thought it was pretty good.”

* * * *

McCoy Tyner (6-10-03):

TP: I’ll try not to burden you with too much stuff that’s commonly known, but if I write a longer piece, I may want to ask you some other things. Let’s talk about this group and this project. It’s obviously not the first time you’ve joined forces with Bobby Hutcherson, but is this the first time you and he have worked together in a while, or has it been ongoing?

TYNER: It has been ongoing over the years. Periodically Bobby and I connect on a project. We did a duet record, “Manhattan Moods,” just him and I for Blue Note, and several things in the past.

TP: “Sama Layuca” and “Solo and Quartet.”

TYNER: Right, with Herbie Lewis. And he was on “Time For Tyner.” So quite a few projects. Then last year we went on tour in Europe, with this particular band.

TP: Which generated this record.

TYNER: Yes, it was a nice tour. We just closed at the Iridium. Eric wasn’t with us, because he’s been doing things with Terence Harland. We try to set it up so everybody will be available to work with me, but we set that sort of thing up gently so that there won’t be any bad feelings.

TP: Al Foster isn’t a bad guy to have available in a pinch.

TYNER: Let me tell you. Al is fantastic. He adds so much to the music, and knows just what to do dynamically. So it’s a pleasure having him around so we can play together. He’s going to Italy with me tomorrow. It will be a trio with Charles Fambrough. I’m in transition at the moment, kind of floating a bit, and it’s real nice. I’ve got some guys who are sailing right along with me.

TP: You mean you’re changing personnel.

TYNER: Yes, I’m changing personnel.

TP: Because you were with Aaron Scott and Avery Sharpe for many years.

TYNER: Yes. Avery was with me over 20 years, and Aaron about 16-17 years.

TP: Thinking of Charles Fambrough, it occurs that you have a bunch of alumni from your bands who are prepared to step in and serve as almost interchangeable parts.

TYNER: Fambrough hasn’t worked with me for a while, but when he was with me it was a great band. We had George Adams and quite a few people.

TP: Right, and Joe Ford.

TYNER: Right, Joe Ford and George Adams and Wilby Fletcher and Charles Fambrough. I can always give them a call when I get stuck.

TP: what are you looking for in your musicians? Apart from the usual things, sensitivity and technical proficiency, is there a particular perspective they need to have on music, or an attitude?

TYNER: What it is… I was looking at some of the younger guys, not just because of age but because of talent, and if I think they have potential for growth and development, and they can bring something to the table in terms of my music… A lot of them have grown up listening to some of my music, along with other artists. Like, Eric had been with Betty Carter, and she was a consummate teacher and very strict about what she wanted, and so she got him in the right place. Charnett’s father worked with Ornette Coleman, so he brought something else to the table. It just so happens, I’m not the kind of guy that randomly fires people. I try to give a guy a chance to see what he can do. George Mraz has done some things with me, we went to Europe not too long ago. And Al is a real professional and a great guy. So I’ve got a bit of selection.

TP: With Bobby and Charnett, it was interesting, because it provided you with two foils. Because Charnett is such a strong soloist and projects such a powerful sound, he was really a match for you.

TYNER: Yes. He’s been quite an individual, and has been from a very young age. His father gave him the right idea about what the music is and said “Go ahead, take a shot, go your way and see what you can do.” With me, he’s able not only to free himself up, but he wants to learn something else about structure in the music, some traditional stuff, which I like to do. I like to do a lot of different things. He’s able to do that. He follows very well, listens, and he’s got a good sound and a good concept. I like those two guys very much.

Of course, Bobby and I go way back, and we play well together conceptually. We’ve been like that for a long time.

TP: It seems you have an exceptional simpatico. It seems you follow each other’s ideas intuitively.

TYNER: We phrase a lot alike. His wife even commented. She said, “Sometimes I can’t tell,” because we’re both keyboard instruments. We have the uncanny ability to phrase a lot alike. It’s kind of unique. A lot of fun.

TP: It’s great to hear the two of you together. You had that sort of simpatico with Joe Henderson on the various records. And I think it would be hard for people to get that with you, because your conception and execution is so formidable.

TYNER: Joe sounded great on his records that I did, and I’m very happy with the things he did with me — “The Real McCoy” and “New York Reunion.” I really miss him a lot.

TP: It seems one thing you and Bobby share is a fascination with pan-diasporic music in its many varieties, rhythmically, the melodies, the scales and so on. I wanted to ask you about the evolution of your incorporating that information in your sound. I gather there was a certain point when you went to Senegal.

TYNER: Well, actually it started when I was a teenager. I was very fortunate. I came up in a very active community musically. The musicians that were around and the jam sessions that were going on. We had this guy Saka Acquaye, who was from Ghana, and he came to Philadelphia and taught some of the conga players and drummers in that genre of playing. A lot of different rhythms, and how to connect everything, how sometimes you play one rhythm and that connects with something else, and you have different layers. He was great. And his sister taught African dancing. I’m writing a book and someone is helping me, and she happened to run into Saka’s name. I don’t know the correct spelling of the name, but it’s definitely in the book.

TP: Did you study drums ever, apart from piano?

TYNER: I was fooling around with it. But it started in the joints of my fingers, and I said, “I can’t mess…” A lot of these drummers wore tape around the joints of their fingers, so it wouldn’t hurt so much. I always had a fascination with the drums…

TP: From the time you met him?

TYNER: Actually, a little before.

TP: How old were you at that time?

TYNER: I must have been about 14-15.

TP: So it would have been 1952-53.

TYNER: Something like that, in the early ’50s.

TP: A lot of Africans started coming to the States after the U.N., like the dancer Asadata Dafora in New York. Do you think of the piano in a very percussive sense?

TYNER: That’s part of my style, I think. I’ve incorporated those rhythms into my style. Also other things. But I used to play for a dancing school, and they did a production of “Viva Zapata” that was… It was a song, actually, kind of a hit song back in the ’50s. So I played piano for them…

TP: This was as a teenager in Philadelphia.

TYNER: Yes. Saka was studying at Temple University, political science or something, and was teaching on the side. I never actually got instruction from him, but I watched him teach the guys who were playing congas. At the time, there was a lot of identification with the Africans, because during that time… Not political. Cultural. Everybody wants to politicize it. But I think cultural identification is good.

TP: Were people like Edgar Bateman checking him out?

TYNER: I’m not really sure. He was around during that time.

TP: I’m just thinking of some of the progressive musicians around Philly.

TYNER: Like Eric Gravatt. Eric had a very keen knowledge of African rhythms. Because he worked with me for a while. Then he went to Minnesota and took up residence there.

TP: Michael Brecker told me that when he was a teenager, they used to play tenor-drums duets.

TYNER: I wouldn’t doubt it. Michael is a fantastic musician, and being from Philly… Guys from Philly have a certain kind of feeling.

TP: But you had an orientation toward African rhythms at the time that you met John Coltrane, and certainly when you were in the band.

TYNER: Yes. And when he came to New York, Babatunde Olatunji was here, and John and Olatunji were very good friends. John would play at his place in Harlem sometimes. So there was a keen interest in African culture. That was good, identifying with the roots.

TP: Do you feel that inflected your compositions, the melodies and scales, and some of the rhythmic patterns?

TYNER: Yes. Especially certain compositions. I think affiliating with this dancing school, I heard a lot of different kind of music. Because they did ballet, they did everything, so I had a chance to check out a lot of music. Also, I studied with two teachers, one a beginning teacher and the other an Italian teacher who took me through Bach, Beethoven, and other areas of European classical music. So I had a wide range of experience in that respect. I tried to keep my mind open. And I always liked Latin music. The music world is so broad.

TP: People of your generation I think learned the music differently than the generation today. Kenny Barron told me that as a teenager he’d play gigs until 3 in the morning, and then go to high school the next day.

TYNER: Yeah, we had a lot of jam sessions around Philadelphia. A lot of jam sessions. We’d be at my house one time, the Heath Brothers would have jam sessions at their house, one time I played up at Lee Morgan’s house. Plus, Philadelphia is in close proximity to Atlantic City. So I would go to Atlantic City in the summer and play… We didn’t have much money, but we managed to scrape up three meals! I played at the Cotton Club in Atlantic City with Lee Morgan’s quartet. It was fantastic, because we had a chance to see… I met J.J. Johnson, and Tommy Flanagan and Tootie Heath were playing with J.J. Dinah Washington. Atlantic City was one of the entertainment capitals of America. That was a great thing. We spent two or three summers down there.

TP: That’s on a very professional level. There were places with chorus lines and so on.

TYNER: Yes. You learned from… There were some fantastic guys around, older guys, the older generation. They took you under their wing, and if they saw you had some kind of talent, that was all they needed to know. They’d call you for gigs and show you tunes, old standards. You would learn just by accompanying. A lot of the things I learned were by being supportive. It wasn’t so much like now, where a lot of people want to set up their own band. There’s nothing wrong with aspiring to get your own band, but when I was with John I wasn’t necessarily looking, “Oh, I can’t wait to get my own band. I just savored the experience of being with him, and I learned so much just by coming together…” You learn how to do that. When I was growing up, that’s what the guys expected from you. They weren’t looking for you to have that kind of cocky attitude. That didn’t fit in at all.

TP: I think it would be a situation with Coltrane where you could play the whole history of the music and frame it as individually as you would want.

TYNER: Well, John was in the R&B band. Sometimes we’d travel and these guys would show up. He used to play with a guy named King Kolax, who would show up when we’d play the Midwest. I played with guys who played what we called House Rockers — the cat would get up and honk his horn and the rock the house, and people would put money in the bell of the horn. That was a great thing, because it wasn’t about a lot of articulation — it was about feeling and sound. If you had a sound on your instrument and a good feeling, hey, that was it. I played with those kind of guys, coming up with blues singers and all that sort of stuff. So yeah, it was on a professional level, even if you were young. That didn’t have anything to do with it. The thing is, to get that experience was wonderful.

TP: Does it make a difference in the way you play what kind of drummer you have with you?

TYNER: Well, it doesn’t change the way I play, but I think what it does, if the drummer is playing WITH me, as opposed to just sitting there playing time, I think… That’s a very important element. But I think if he’s responding rhythmically to what I’m doing on the piano, it’s a tremendous asset. Because I play very rhythmic anyway, so rhythm is very important, and then I’m able to go from there to other things. It’s a good point of departure.

TP: I want to continue on the rhythmic aspect. In the ’50s and ’60s were you listening to Cuban or Puerto Rican piano players, and that style of playing in clave, which is different than jazz improvising. Because your own brand of that music is so idiomatic and yet personal to you.

TYNER: Well, I think that has a lot to do with the African influence. The jazz and Latin rhythms came out of the African experience. But because we were from the Americas, it’s a little different. But that’s the foundation of gospel music and blues, and jazz came out of that. So those rhythms have been able to last. But that’s basically where I had a real pleasure just… I played with a lot of Latin musicians over the years, and we feel as though there’s very little separating us, and more connecting us than anything else.

TP: I did read that you had gone to Senegal, and that it was an important experience for you.

TYNER: It really was. It must have been 7-8 years ago. I flew into Dakar, and then we drove from Dakar all the way down to St. Louis. The French government put on a festival there. A guy who produced several of my recordings of the big band, who has some affiliation with that festival. It was beautiful. We went through many villages on the way down. When I got down there, there were some djembe drummers who played with me. I went down with Jack DeJohnette, and these guys sat in. They were a family of drummers. What happened is that they liked us so much, the French guys and the Africans, that they asked we do a tour of France with… I think Jack did the tour, and there were two drummers from that family. It was great, and we were able to create a nice marriage.

TP: Was it a very organic process to start bringing this material into your music circa 1969, when you did “Expansions,” and the early ’70s?

TYNER: Yes, I’d say it was pretty organic because of my previous experience with African rhythms and drummers, guys who played… One of the guys who played regular trap drums in my R&B band when I went into modern jazz was a conga player, Garvin Masseaux, and he studied under Saka, along with a guy named Bobby Crowder. They played together a lot and they were good friends. So from an early age I’d been influenced by African music. Bobby played and did some recording with Red Garland. Those guys were our premier conga players around Philadelphia. Garvin played with my R&B band.

TP: And I gather that’s the band that you started you off in writing charts and writing tunes.

TYNER: Yes. I wrote this chart that never ended. [LAUGHS] Well, it seemed like it never did! Boy, it was long. I must have been about 14 or 15.

TP: Jimmy Heath described his early writing efforts in Philly in a similar manner, and so did Benny Golson, so you’re not alone.,

TYNER: Yeah. You have a lot of ideas and you try to cram them all in one song.

TP: When did your early mature pieces come, things like “Effendi,” and so on. Did you write them in the early ’60s, or did you bring them up then…

TYNER: Yes, that’s after I got… John and I were the first two jazz artists on Impulse, and “Inception” was my first record.

TP: Wayne Shorter, for instance, said that he was writing pieces from the early ’50s, and some of them got into the Art Blakey book when he joined up. I was wondering if you had been that prolific before coming to New York and entering the public stage.

TYNER: Yeah, I was writing some things when I met John. But I came to New York after the Jazztet. I worked with the Jazztet for a while, because John was committed to Miles and he couldn’t leave, and he wanted people in his own band and it took him a while, so Benny Golson asked me if I was available to go to San Francisco. He had three weeks at the Jazz Workshop over on Broadway in San Francisco. I said sure. Then John left Miles not too long after that. That’s after we did the Meet the Jazztet record, where we did the first version of “Killer Joe.” It was a great band, but completely different from the direction that was about to develop being with John.

TP: Benny Golson said he knew it was confining for you.

TYNER: Well, the thing is, he wrote some nice charts! Benny’s a heck of an arranger. And he wrote some nice tunes, “Along Came Betty,” “I Remember Clifford,” some nice songs. I enjoyed my experience with them. But I had a verbal commitment with John that whenever he left Miles I would join his band. So to make that transition took a little time — not too much, because I was with the Jazztet only 7 months. Then John left Miles, and he came to me and… It was very tough, because I grew up under Benny. It was tough for me, too, because they were such nice guys and really very helpful, but it was something that had to be done. I think Art and Benny realized that later on.

TP: Are you writing for the personalities that you’re playing with? Is there any of that in your composition? Or do things just come out and people adapt to them?

TYNER: What it is, you want to surround yourself with people who can interpret what you write. With the big band I have more that type of thinking, because it’s a different type of thing — but not so different. I’ve had the big band since the ’80s. Some of the members of the band, like John Clark and Joe Ford were in the band when I first started it, and they’re still there. So I know their personalities, and I know generally which songs I like. I mean, anybody can play on any songs, but with some guys it’s just tailor-made for them. I think that’s what happens. Duke Ellington wrote for some of the guys who were in his band. You can’t help but do that, I think.

TP: Also, there are a number of your songs that have been performed in many different contexts. Are you still writing prolifically?

TYNER: This record has some songs I’ve recorded before, but a lot of them are new, like “December,” “Serra Do Mar,” “Steppin'”. “Manalayuca” was recorded before; the title has changed a bit. I’ve recorded “For All We Know” before. So there’s the mixture.

TP: And were these written and chosen with this personnel and instrumentation in mind?

TYNER: Well, yes, in a way. Definitely, because I knew who was going to be on the date. I don’t really earmark… See, Bobby and I have no problem in terms of concept, because we think alike conceptually. But I don’t necessarily all the time… “December” was a song that I had in mind… When I wrote that, I thought it would be wonderful to hear what Bobby could do with it. Because I know it fit his style. And I felt like Eric and Charnett would really be able to handle “Serra Do Mar” because it goes from one rhythm to another; different segments of the song interchanged, and I thought they’d be able to interpret that well. But often I don’t necessarily write everything to tailor-make the song to fit a person. But I try to pick people who I think like to play my music or can interpret my music well, as opposed to, “Oh, let me write music for this guy.” But I like to surround myself with people… Because if a guy doesn’t fit into the concept that I have, then he doesn’t need to play with me — that kind of thing. I shouldn’t say it like that, because I have played with guys who aren’t necessarily used to playing with me, and it’s different for them. I’ve heard people say, “You’re moving all the time.” But that’s from playing with John. He liked me to move around.

TP: Just talking to you, the program seems almost autobiographical. There’s material that addresses pan-African rhythms, and you have the blues and the standards and the Ellington and the ballads, and it’s all part and parcel of your musical biography.

TYNER: I think that music should reflect you. If you’re the one who’s performing or composing, it should reflect who you are.

TP: You do concept albums, which is logical, because to keep putting out albums, you have to find ideas to tag them on and give people different angles. But this has a very organic quality. It doesn’t seem like there’s any imperative involved except something coming out of you and what you’re thinking about at the moment.

TYNER: I think you nailed it. I’m glad that came out, because that was actually the way I felt.

TP: Seeing you at Iridium put an exclamation point on it. They had me sitting right up by stage left so I could see you at the piano, and I’d never been that close to you before, and I noticed that you play with a minimum of motion. For someone who gets as huge a sound as you get… For instance, Ahmad Jamal moves a lot around the piano and dances around the piano.

TYNER: Keith Jarrett does, too. He really gets around. It’s whatever works for you. For me, in how I utilize the instrument, and it has many characteristics… I approach it a certain way in terms of touch and uses of the pedal, and that gives me the power I need. I figure it has a lot to do with the touch as well.

TP: Was that a sound you heard in your mind’s ear and worked towards, or did it come out of your development as an instrumentalist.

TYNER: I think it was already up here. I think your sound is who YOU are. That’s exactly what it is. You can’t create it if it’s not there, and you can’t embellish on it if it’s not yours. We have our own sounds! When you talk, when people recognize who you are, I’ll say, “That’s Ted.” You have your own sound, and it comes out when we play an instrument.

TP: But if I put my hands to a piano, people would say “shut up!” There’s truth to what you say, but there’s also a craft component.

TYNER: Have you studied piano?

TP: Many years ago, and I’m not suggesting I couldn’t develop a certain proficiency…

TYNER: If you ever played the instrument enough, you would hear Ted coming out. You have your own identity, man. I think we all do.

TP: Many musicians would tell me that the instrument is an extension of themselves, and that music is just another vocabulary…

TYNER: A language.

TP: And they say it gets passed down. One of the great things about jazz is that the oral tradition still holds true. Who for you are some of the people who passed down that oral tradition…

TYNER: I was very fortunate. I met Bud Powell. He lived around the corner from me when I was a teenager. My mother was a beautician, and my piano was in her shop. So Richie Powell was on the road with the Max Roach-Clifford Brown band, and Bud occupied Richie’s apartment. It was right around the corner for me. And my mother did the superintendent’s wife’s hair. So she came and she said, “There’s this piano player around the corner who doesn’t have a piano; can he come around and practice on your son’s piano?” So I asked my mother who it was, and she said, “Bud Powell.” I said, “Of course. He can come around any time he wants.” But he was a hero to us. We used to follow him around. We had a place where musicians would hang out, and we’d get him to go up there and play. His recordings were fantastic. And Thelonious. I used to… But I didn’t listen to them to copy them. What I heard was individuality, the fact that they focused on who THEY were and they did their thing. But they were very inspirational to me. And later on, Art Tatum, because [LAUGHS] he was an impeccable musician. But stylistically, Bud and Monk were really major influences on me — and then John, of course.

TP: There’s that German word, the “zeitgeist,” of the time. They were absolutely one with their time!

TYNER: Yes, that’s right. And they were so inspirational.

TP: So it wasn’t so much that Bud Powell said, “Here’s how I do this voicing” and so on. You soaked it up.

TYNER: No. You have to do that yourself. You have to find out what your voice is yourself. That’s it. Not only is it lasting, but you can develop something from your own personality, your musical personality. Otherwise, you’re not going nowhere with it. You’re just limited to whoever the guy is you’re copying, or you’re trying to model yourself after.

TP: Were there any pianists you did that with? Herbie Hancock told me that when he was 13, or maybe 11, he found a guy in his class who could play, and he’d been playing Mozart and classical music and was a prodigy, but he couldn’t do this. Then he found out it was George Shearing, and his mother had a George Shearing record at home, and so he played along with it until he got the accents and phrasing, and that launched him.

TYNER: Bud Powell was that image for me. I had Bud’s records, and I was trying to play things like “Celia” and things like “Parisian Thoroughfare” and a couple of other things. But then I knew that, “Hey, that’s Bud Powell.” Because that’s just the way it is. You can’t go but so far.

TP: But those were things as a kid, you memorized and…

TYNER: Well, you have to… A lot of the horn players were playing as well. Actually, what it was, we knew certain pieces like from Clifford Brown-Max Roach and Dizzy’s music and Bird’s music, all these guys playing Charlie Parker’s music. So I had to learn that stuff in order to play with them. When I was a teenager, Sonny Stitt would come through… I would play with different people. Sometimes Sonny Rollins would come through, and Sonny Stitt. I was playing around locally with a lot of the older musicians. So I had to learn the tunes.

TP: Was that at a place called the Red Rooster?

TYNER: Well, that was I met John, at a matinee. It wasn’t far from where I lived. It was a local kind of…not an elaborate place, but a fairly decent place, and people used to come there to listen to music. I was playing in Cal Massey’s band. Cal was the friend who introduced me to John. And Jimmy Garrison was in Cal’s band, and Tootie Heath. John came out and checked the matinee. He was on sabbatical from Miles, there was a little period there, and then he came up and he and Cal got back together… Cal was a composer as well. So that’s how I met John, one afternoon.

TP: But back in 1960, you weren’t the average 22-year-old. You were a pretty experienced musician. I think you recorded with Curtis Fuller in ’59.

TYNER: Yes, my first record. I think it was “The World of Trombone” or something for Savoy. That’s actually before the Jazztet was formed, and after that they had a meeting with Art and Benny and Dave Bailey and Curtis, and they said they wanted to form a band, and I said, “Okay, but when John leaves Miles, I’ve got to go.” It was a tough one.

TP: Did you play with any vibraphonists then?

TYNER: Yes, there was a vibraphonist around Philadelphia who was very popular…

TP: There was Lem Winchester in Wilmington and Walt Dickerson.

TYNER: Walt was the guy.

TP: And he had an expansive concept himself.

TYNER: Yes, he had an expansive concept. Absolutely.

TP: As I recall, the “Time For Tyner” record was a live record in North Carolina? That’s when you and Bobby first hooked up.

TYNER: No, it wasn’t live. Let me tell you what happened. People have made that mistake because of the way the guy wrote the liner notes. I played a concert at this university in North Carolina, and the guy came down and reviewed it. Then for some reason, he happened to mention that on this recording, and it left people with the idea that it was recorded live — and it wasn’t.

TP: But was it a working band?

TYNER: No. Bobby and I never worked extensively together. But we knew each other very well. We came up in the same generation, so…

TP: And you were both on Blue Note.

TYNER: Both on Blue Note. Wayne and a lot of guys were all on Blue Note at the time.

TP: What’s interesting is that a lot of the things that were recorded on Blue Note were just in the studio and didn’t have to do with working bands. Was that the case with you?

TYNER: Yes, after late ’65, when I left John… It was almost six year. Which records are you talking about?

TP: “Expansions” or “Time For Tyner.”

TYNER: No, those weren’t working bands.

TP: “The Real McCoy.”

TYNER: No. Joe Henderson just happened to be in town, and they wanted to do a date. I did some recordings with him. “Recorda-Me”, I think. Kenny Dorham was on it. But I didn’t have a working band at the time. Ron Carter did a lot of recording with me, too, but I didn’t have a band.

TP: But with Bobby Hutcherson, it just emanated from…

TYNER: Our musical association.

TP: And it just kept cropping up again.

TYNER: Yes, exactly.

TP: Does the record label you’re recording for have any impact on the type of music you’re recording, or does it just have to do with the time and the place.

TYNER: No. Telarc is basically a jazz label, as far as I know. But they have no bearing… They know when they ask me to record what they’re getting into. I don’t do that.

TP: So all the projects you’ve done for Telarc have been at your initiative? The trio and “Jazz Roots.”

TYNER: Absolutely. If they make a suggestion, maybe I’ll try this or that or whatever conceptually, but I have the final word on everything. If I don’t like it, I won’t do it.

TP: Are you exclusively with Telarc now? Or are you still a freelancer?

TYNER: I’m not signed with them, because I like to be a free agent. But I have done some consecutive work for them.

TP: Since that thing for Impulse, “McCoy Tyner Plays John Coltrane,” I think everything you’ve put out has been on Telarc.

TYNER: Yes, that was done in 1997, but they released the tapes in ’99.

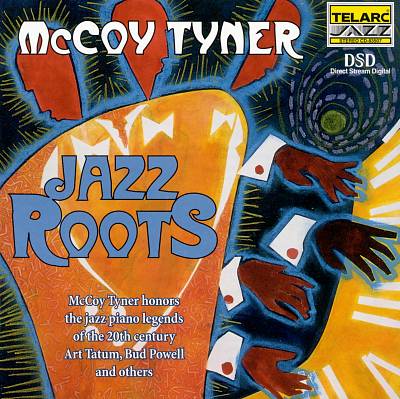

TP: Tell me about the Jazz Roots album, the tribute to your various influences.

TYNER: It wasn’t so much influences. It was a dedication to the musicians that I knew — and know — and who were part of the history of this music, and guys who passed on and a lot of them who are here. It’s a tribute to jazz pianists. That’s basically what I was doing. Erroll Garner, Duke Ellington, Bill Evans, Chick, Bud Powell, Thelonious… It was just a conglomeration of different people.

TP: was it easy to choose the repertoire, or a difficult process?

TYNER: Not really difficult. Because I chose songs that I thought fit these guys, and did the best I could to do that. I felt pretty good about it, the choice of songs for each guy.

TP: Is performing in front of an audience for you a very different experience than performing in a studio?

TYNER: It’s different. The thing is, it all depends. If you’re working with people consistently for a long period of time, it has to make a difference. Like, “A Love Supreme” was sort of a culmination of all the musical experiences that we’d had with the quartet, and it was a high point. But we knew each other. We knew each other’s musical vocabulary. If you talk to a person long enough and you live around a person long enough, you begin to get familiar with how they phrase, in terms of the words the pick, whatever. Even if you can’t nail it right on the head all the time, but you have a sense of where they’re going with what they’re saying. And it’s the same if you play with somebody for years. You don’t have to second-guess. You can just about go where you’re supposed to.

TP: Your solo records are so rewarding. I have the three solos or duos you did for Blue Note, and then this one…

TYNER: I like to play solo. I really do.

TP: You sound free when you play solo.

TYNER: Yes, because you can go where you want to go. You don’t have consider if the bassist is following you. Well, you can hear. You don’t have to worry about the drummer, if you’re dealing with the rhythms or the melody or with the harmonic content. It’s all about what YOU want to do. And that’s a lovely thing. I like playing with a group, because if you can bring that kind of sensitivity to a group setting, it’s wonderful to have two or three or four guys or a big band do that, be sensitive to what’s going on, and listening and responding. But if you really want to talk in terms of empathy, I think you can’t beat solo playing. It’s about you. You’re the only one there. You can’t lay the blame on anybody!

TP: Do you still practice a lot?

TYNER: No, I don’t. Not at all. I should. But I play a lot. I perform a lot . But I try to compose. I hear things in my hear and try to do that. But I really don’t spend time practicing. I used to years ago. But my whole career, I’m very fortunate that I was working a lot with John… I haven’t really practiced since I was a teenager. I spend time at the piano composing. That’s about it.

TP: If you were going to practice, what might it be that you’d want to work on?

TYNER: You know, Miles never practiced either. There’s something about… When you play before the public, it’s better than practicing, I think. Because you know that there is a communication that has to be made. The music is about communication, too. And I don’t mean playing down to people. I mean just acknowledging the fact that they’re there, listening, and you’re going to take them on this journey. I think that’s basically what it’s all about.

TP: Philly Joe Jones once made the comment that he knew exactly what his hands were going to do, so why did he need to…

TYNER: Yeah. Well, see, you want it to be automatic. You want it to be real self-expression. And practicing is… I already had the tools that I need to work with. It’s just a matter of ideas and how you present it.

TP: You said that Miles didn’t practice, and he didn’t rehearse either. And I gather you have a fairly liberal attitude about rehearsal.

TYNER: Yes. Because we didn’t rehearse… With John, I think we might have had… Well, I wouldn’t say a rehearsal. We ran over some material we were going to record, maybe the Ballads album, and all I did was get like an intro and an ending, and that was it.

TP: So getting together with Bobby for the European tour and presenting this new material, how did you let it evolve?

TYNER: Well, we had to run over the material, because there were certain things I wanted to emphasize. But I wouldn’t say practicing. It was just reviewing the music.

TP: Because you’ve known each other so long.

TYNER: That’s what it is. It’s true, what Philly said. Because if you have the tools, what are you practicing? If you HAVE the tools, then it’s just a matter of the ideas and the feeling. That becomes paramount, as opposed to “let me get in a couple of more runs under my fingers.” Eventually that happens if you play enough over a period of years, that you can execute without thinking about it.

TP: Would you talk a bit about the distinction between composition and playing?

TYNER: I like to play my songs actually. But then, again, I stuck that Duke Ellington song in there, “In A Mellow Tone,” because I like it. And Duke’s songs have a tendency to swing! Just playing the melody itself. But basically I do like to play on the songs that I have written.

TP: I guess they suit your style.

TYNER: Yes, that’s what it is.

TP: I’ve heard many musicians refer to improvising as spontaneous composition.

TYNER: That’s a good phrase. That’s exactly what it is. And a lot of times, you’ll come up with a melody based on something you’ve played — that you are playing. “I’ve heard that before.” “Oh, I played that last night.” [LAUGHS] Maybe you think about that. I don’t know. You don’t know where exactly it’s from, but it’s part of your expression in some kind of way.

TP: I don’t know exactly how many records you’ve done, but there can’t be many things you haven’t done in your career. I’m wondering if you have any aspiration that you haven’t fulfilled yet.

TYNER: We’ll see.

TP: You’ll let it come along.

TYNER: Yes. Something will tell you. You just do it, and something will say, “Well, yeah, that’s the right thing.” It just comes to you. If music is your world, or whatever it is, it becomes intuitive. You don’t have to sit down and plan it for a year. I can write a whole date in a couple of weeks in advance. I wouldn’t advise people to do that. But I’m just saying that when I’m placed under pressure, I do pretty well.

TP: Pressure is the great motivator.

TYNER: Yes, it sure is. When you have a deadline. But that’s good, because you learn how to deal with it.

TP: You bet. And it makes you stronger.

TYNER: That’s right.

TP: So this summer, are you going to be out a good bit, and any with Bobby?

TYNER: I’m going to Italy and to Japan for about three weeks, and George Mraz and Lewis Nash will be playing with me.

TP: You’re just getting all the second stringers, aren’t you.

TYNER: George is a wonderful bass player. He knows how to play with a piano. For some reason, you can go where you want to go, and George is right there. He’s a nice man, he’s fun to be around, and it’s nice to have that kind of selection of people. He played with Oscar, he played with Hank, he played with Tommy Flanagan. He knows what to do when it comes to piano players! He’s not trying to take it out. He’s the kind of guy that likes to blend into what’s going on. But when he solos he’s got a beautiful sound on the instrument. I love George.

TP: You’ll have fun with Lewis, too.

TYNER: I did an album of Bert Bacharach’s music that Lewis is on. I host at Yoshi’s in Oakland every year (this will be the tenth year), and a lot of guys play, and each week is a different band. Lewis and Christian McBride, who’s one of my neighborhood guys, played very well together. This year it’s going to be Tain Watts.

TP: Tain told me a story about having an initiation with you, back in ’87, when he played with you and put out all his stuff on one tune, and he said that after that he was hanging on for dear life, because he’d played it all already. You were just beginning and he’d played all his stuff.

TYNER: [LAUGHS] Well, he’s increased his knowledge. He seems to have a lot left.

TP: Well, he told the story with relish. It was, “Yeah, McCoy got me.” But again, Art Blakey did it, Miles did it… You’ve become this jazz elder…

TYNER: Elder statesman? [LAUGHS]

TP: Well, a jazz elder griot type of thing, where the material gets passed down in this manner to so many people who then sustain it.

TYNER: I’ve been fortunate to have known a lot of great people who were great inspirations, and I’m very thankful for that opportunity — or whatever you would call it.

* * * *

McCoy Tyner (7-25-03):

TP: I’d like to talk first of all about your summer itinerary, the configurations you’re working in, the musicians you’re playing with. I gather you recently did three weeks with Lewis Nash in Japan.

TYNER: Yeah, he went with me to Japan, and we did a tour of the Blue Notes in Japan. It’s very nice; Blue Note franchised out the name over there. It was a great reception. I’ve been going to Japan since 1966. The first time I went over was what they called the Drum Battle (it was more like a reunion to me) between Tony Williams, Elvin Jones and Art Blakey. It was the first time I went over, with Wayne Shorter, Jimmy Owens, and I forget the bass player. Of course, I’ve gone back after that with my own bands over the years.

TP: You did a number of recordings there.

TYNER: I did a solo piano thing, “Echoes of A Friend,” which was dedicated to Coltrane.

TP: You did it in ’72.

TYNER: Yeah, something like that. But there’s a solid base there.

TP: Japan is part of your regular touring itinerary. I guess the trio with George Mraz and Lewis has a certain type of tonal personality. Do you go in a different direction, say, with that personnel than, say, with Charnett Moffett and Al Foster. Or if Jack DeJohnette were playing in a trio with Ron Carter. I’m just throwing out names. I’m wondering how different musicians of different attitudes affect the way you respond and listen.

TYNER: Well, it’s always like that anyway, when you play with people of different characters and characteristics, different personalities. It’s just like meeting an old friend. You can’t compare him to the one you ran into yesterday. They’re completely… Well, they’re not completely different, but what it is, they know what my style is like. So what they do is, they know they have to listen, and that’s all I ask. Because I wouldn’t have chosen to have them on this tour if I didn’t think that they could perform with me. And individually, they have. George played with me and Al when we did this Coltrane tribute, and Lewis did the Bacharach thing and something else with me. So they know what they’re in for basically.

TP: Do you know what you’re in for beforehand?

TYNER: No, I don’t want to know.

TP: Do you like the surprise?

TYNER: [LAUGHS] Yeah. I’m surprised all the time. Because they’re growing, and I say, “Oh, wow, there’s something different this time.” It’s always different anyway, but it’s nice to hear them move in a positive way and develop. Because we’re all growing. That’s what it’s all about. One tour you do with a guy one time, and then the next year or so it’s different.

TP: But you had a working band for many years with Avery Sharpe and Aaron Scott.

TYNER: Yes, I did.

TP: You did other projects, but that was basically the band. Now it seems like you’re experimenting with different configurations.

TYNER: Yes.

TP: What was the reason for disbanding at this point?

TYNER: Well, everything runs its term. What I’m saying is that everything has a term. I had a great rhythm section with them for years, but then I thought it might be a good time to do something different. I think if you force something to happen, even if it’s change, you can have a negative response. But if it happens naturally… In all the bands I’ve had, it reached a point where it served its purpose for that time period. Then it was time for me to choose something else. But I didn’t force it. Avery was with me for 20 years and Aaron was close for 17-18 years, so it served its purpose.

TP: Can you describe what the purpose might have been with that band? I mean, they were obviously very suitable to you. You had a three-way affinity. You’re not going to do anything you don’t want to do for two decades.

TYNER: Mmm-hmm.

TP: Talk about the qualities.

TYNER: It was very good qualities. The thing is that they were very consistent in what they were doing, and determined. They were eager to learn and develop. And that’s one thing I do like about people who work with me. I hope that when it’s served its purpose, that they walk away with information that they didn’t have before they joined my band, and had the opportunity to develop. I think that’s very important. But I think it went as far individually as it could have gone, and as a group, consequently, if you don’t move, then everybody is sort of stuck in a situation… You want to be organic. You want to be healthy no matter what the configuration is. You want that healthy attitude. And we can only do what we can do.

TP: It sounds to me as though you’re now in a mind space where it suits you to play with as many different empathetic personalities as you can, and are able to give yourself a lot of leeway. Would that be true, or are you looking to find a steadily working group again?

TYNER: As long as they’re compatible, is what I’m doing. If they’re not compatible… I can tell sometimes by listening to people. I heard Eric when he was with Betty Carter. We were in actually, of all places, Beirut, Lebanon! They invited us over. I was a little hesitant at first, but then I’m glad we went. They were very nice people who invited us there. Eric was playing with Betty then, and I was playing I think with the Latin band opposite her. I had a chance to hear Eric then. I had met Eric actually as a teenager in high school in Houston. I went to the university to give a little bit of a talk, and met him. He was a kid at the time. Of course, he’s developed quite extensively from when I met him with Betty, but it was nice…

TP: She raised him good.

TYNER: [LAUGHS] Well, the thing is that we were able to play together and have fun, and that’s good. He plays with Terence Blanchard and other people, and I think he was with Charles Lloyd recently. I think Charles heard him in London when we did the thing in London, and said, “Oh, I want that guy to play with me.” It’s not a steady gig, but he definitely has been making some appearances. But hey, whenever possible. That way, I don’t have to dependent on any one guy — on one bass player or one drummer.

TP: So there’s the trio, and are you doing anything with Bobby Hutcherson this summer also? Or are you resuming that quartet in the Fall?

TYNER: I think we’re resuming in the fall. We’ve come back from Japan not too long ago, maybe ten days ago, and we’re doing something at Lincoln Center on August 2nd. Dave Valentin is playing flute, and Charnett Moffett and Eric on drums.

TP: I’d like to ask about the Latin band a bit. This will take me back a bit and focus on that Philadelphia territory.

TYNER: Are you from Philly?

TP: No. I know a lot of people from Philly, though, and I’ve talked with a lot of musicians who are your peers and older than you and younger than you, like Benny Golson and Jimmy Heath and Reggie Workman and various people. When we spoke earlier, you said there was an African drummer in Philly whose name you couldn’t quite recall the spelling of, who taught you in the early ’50s…

TYNER: He didn’t teach me, but I was in his presence. He taught guys who percussion was their thing. That was their instrument. I played piano. I was just messing around with him.

TP: You said you did fool around with the drums, but it damaged your fingers.

TYNER: Yeah, in the joints. That’s why you see a lot of conga players who have tape on the joints. They say, “I’m not going to ruin these babies.”

TP: The crown jewels!

TYNER: [LAUGHS] I had enough intelligence even during that time!

TP: You mentioned Garvin Masseaux, Robert Crowder…

TYNER: Rob’s still there.

TP: Eric Gravatt might have been an extension of that. But what this guy was doing filtered into your consciousness, sort of became imprinted on the way you think about music. Then there was a quote in Lewis Porter’s biography of Coltrane from your former wife Aisha that Latin music was very big in Philly, and everyone danced the merengue. So all this stuff was percolating for you when you were a young player, in formative years. I wondered if you had anything to say about how that environment became more solidified as you became a more mature musician.

TYNER: I was exposed to African culture when I was a teenager because the atmosphere was conducive to that. So Saka coming to study at Temple University (I think it was political science or something like that), and bringing his sister over to teach African dancing was very appropriate, because at that time people were involved and being conscious of who they are in history. From that point, we then… Of course, we met Olatunji in New York. Although my association with the dancing school at the time is where Saka came to teach the other guys, the percussionists.

TP: So when his sister would teach African dance, he’d come in and play or bring those guys in to play with the class?

TYNER: Yes.

TP: And did you play in the dance class that he was teaching, or the drummers?

TYNER: No, the drummers would. The only thing I did was, I composed a…not composed, but I just played a little piano for one of those things they did, a kind of South American production, along with other things…

TP: I think you said “Viva Zapata.”

TYNER: Yes, “Viva Zapata.” I played that for the dance company. Because they did some choreography for that, and that was kind of a big…

TP: But when you started composing music… You said your first charts were with that R&B band you had, but I’d think your more mature compositions began when you were 19-20-21…

TYNER: No, before that.

TP: What’s the earliest composition of yours that you recorded?

TYNER: Well, I did an album called Inception on Impulse!, and there’s a song called “Sunset.” “Effendi” is another thing.

TP: “Effendi” you wrote in Philly?

TYNER: No, I didn’t write that in Philly.

TP: I just wondered if there was anything when you were 18 or 19…

TYNER: Yeah, I wrote a song, but it was so long, I should have called it “When Is This Going To End”? I wrote a few songs, but I don’t remember exactly the title of the song. It was something I wrote for my R&B band. But what we did was play “Flying Home” and some Tiny Bradshaw stuff…

TP: You were how old then?

TYNER: 14 and 15, like that. I improved very rapidly, you know.

TP: It sounds like your learning curve was immense.

TYNER: Yeah.

TP: You didn’t play until you were 13, but by the time you were 17, Coltrane was impressed!

TYNER: Yes, it was meant to happen. I played with a lot of people. Red Rodney moved to my neighborhood, and he knew Oscar Pettiford, and Oscar came in. We played one week at a local place called the Blue Note. Red had played with Bird, and he moved into my neighborhood, so he found out about me. Then, of course, I met Calvin Massey way before that, and that’s who introduced me to John.

TP: People in Philly born in 1938 include Lee Morgan and Reggie Workman and Archie Shepp. Pretty good company.

TYNER: Yeah! I used to play with Archie and Lee. Lee and I used to play fraternity dances. We did a graduation at Cheyney College outside of Philly. We did gigs around. We went to Atlantic City, which was fun. Then Max Roach came through. I met him when I was 18, right after Brownie and Richie had passed, and he was trying to get me to join his band. But Sonny Rollins and Kenny Dorham were playing on there, and George Morrow. That was a heck of a band. But I didn’t travel. I did the week at the Showboat.

TP: The story you told about Max was that he asked, “Do you know ‘Just One Of Those Things’?” and you played it at his tempo, and he said, “Ah!”

TYNER: [LAUGHS] Yes. I loved playing with Sonny.

TP: So the standards were high when you were coming up.

TYNER: Yes, the standards were very high. Appearance, presentation — you had to be on point for that. It was good training, because things to changed as time went on, and people started looking at it completely differently. The musicians, basically, the way they presented themselves, and… Of course they were very talented people. But still, I think presentation is a major part of the music.

TP: You’re obviously someone who pays a lot of attention to personal style.

TYNER: Uh-huh.

TP: It’s obvious, just seeing you now. It’s 90 degrees, and Mr. Tyner is in a very nice, dark blue…is it a silk shirt?

TYNER: Yes, silk.

TP: A beautifully textured silk shirt, a white patterned silk tie, and it looks like white linen pants.

TYNER: Yeah, that’s what it is.

TP: Now, maybe you have someplace to go now.

TYNER: No. I just…

TP: But you always look tip-top when you’re performing.

TYNER: Yes, that’s important. I came up in an era when Art Blakey used to say “People see you before they hear you.” It’s just a respect for yourself and what you’re doing that I think should emanate before you go up.

TP: No doubt. Your mother was a beautician, had a beauty shop. Did she have a lot to do with your personal style and sense of presentation?

TYNER: My mother had a lot to do with everything in my development! Her name was Beatrice — Beatrice Tyner. She was just the ultimate classic person. Very, very elegant, my mother. I don’t mean that in terms of using clothes or to make her better than anyone else, but just her demeanor, her personality. She’s a very honest, very likeable person. People really loved my mother a lot. She was caring, a very caring person. She loved music. She loved piano actually. She didn’t play, but sometimes we’d go to somebody’s house who had a piano, and she’d tinkle a little bit. But when anything came up that she thought I should be interested in, she’d let me know — and be very supportive.

TP: It surprises me, just because of your level of technique and fluency with the instrument, that you started playing at 13. It sounds like you were listening to music from way before that. It sounds like all this was in your head and your body by the time you started playing.

TYNER: Yes, I’d say so. I listened… From my affiliation with the dance school and the fact that I had two good teachers in the beginning, one guy who taught the beginner piano and then I had an Italian teacher who went through the books and all that. That was kind of before I formed my R&B band. I was 13, 13-1/2, whatever. Then about 14, I put the books kind of the side, and just started studying a little theory. I went to Granoff School, but that was more like… It was a basically European approach, and that wasn’t what I was looking for. And the (?) Music Center, which was a nice place…

But I think that mine just came from… I had the facility, because I used to practice all the time. But like I say, you can’t describe why you have certain treasures, why certain things emanate from you, why certain things just emerge. It’s hard to explain a gift. I mean, how can you explain that? It’s just one of those things. You keep doing it. And of course, I had the encouragement of a lot of older musicians around Philadelphia. Even before I met John, there were guys who were very encouraging — older musicians who heard about me.

TP: Piano players?

TYNER: Well, there were piano players around town that were very nice.

TP: Who were some of your mentors?

TYNER: Well, Bud Powell was around the corner from me.

TP: Was he personally encouraging?

TYNER: No, not personally encouraging.

TP: Did he have a wall around him at that time?

TYNER: Well, he was kind of like a child prodigy. But he needed care. He needed somebody to be with him. He needed somebody to take care of him. He couldn’t function alone. So he always had these guys. I don’t know how sincere they were, but they were around him. But the level of musicality around Philadelphia was on a higher level. The jam sessions… We used to have jam sessions all the time. See, what you can’t do… If you’re going to add to what’s there, if you’re going to contribute something, you can’t copy from… You can’t copy people. It has to be there. It has to be something that you’re born with. I never wanted to play like… As much as I loved Bud and Thelonious, I learned a lot from them, from listening to them, and then, of course, meeting Bud and meeting Thelonious later…over the years… They taught me… And Monk was adamant about it. He respected you when you had your own direction. He loved that. I mean, I learned a lot. I used to kind of try to (?) Monk when I was still (?). But not to the point where I wanted to be them or wanted to sound just like them. But Monk was definitely the kind of person, like, “You have your own thing? Great!” Because that was the way he was. I was very fortunate to know him kind of on a personal level.

TP: There’s that old jazz cliche, “make a mistake; do something right.”

TYNER: That’s right.

TP: Benny Golson had a story about playing maybe with Buhaina at the Cafe Bohemia, and his eyes are closed, and he looks up, and there’s Monk in his shades, and after the set he made a comment to the effect that he was playing too perfect, and he just stop thinking about being perfect.

TYNER: Yes, that’s true. A lot of things come out of so-called “mistakes.” Really, it’s how what you do with it. How you shape music. Nothing’s a mistake. It’s how you resolve. When you play something, how you resolve it.

TP: Thinking on your feet.

TYNER: Yeah, thinking on your feet.

TP: At this stage of your life, do you ever make mistakes that you resolve?

TYNER: [LAUGHS]

TP: There’s a certain sense of magisterial authoritativeness to the stuff you do! I don’t know how else to describe it. But there are times when it sounds as though you’re allowing yourself to get to the other… It sounds like you get into separate spaces when you play, that sometimes it’s just the way it’s supposed to be and presentation, and sometimes that it’s more open-ended. Now, I don’t know you at all, but am I anywhere close to the reality?

TYNER: Yeah. Well, the thing is, I sort of have a controlled sense of experimentation. That’s what it is. I go out, but I have to come from something. Whatever it is, there has to be something there to work from. Or it can be created. If it’s sort of a song that’s open, like one of the songs on the record…I forget what I called it… Not “The Search,” but the title is something like… We didn’t have a melody, but it was conceived that way — no melody. So we just used tonal centers, moved from one tone to another, from one sound, one cluster to another — that kind of thing. Which I had that experience paying with John. But I try to use that when it’s appropriate for me, as opposed to using that as a main way to express myself. It’s another tool. That’s all.

TP: It’s interesting that you can go in and out of those attitudes. A lot of people who have a total sense of their music, who are composers, don’t allow themselves to get into that space, or very rarely so. And you seem able to access both parts of yourself.

TYNER: Yes. I have sort of a mixed personality in that respect. I can do that. I’m not trying to prove anything…to no one.

TP: I wouldn’t think.

TYNER: Just trying to have some fun, and trying to find out more about myself musically. And sometimes, you find out after you listen back at something. You say, “Wow, that’s what I did. Where was I going?” Because I don’t want to reach the point where everything is predetermined. It’s not artistic when everything is predetermined.

TP: I don’t want to burden you too much by dwelling on your time with John Coltrane, but your comment makes me think of a comment I read in a French magazine, where you spoke of your contribution to the evolution of that music, and that it was rooted particularly in your time, in the authority of your left hand, that he always had a home base to come back to somehow, and that you always have a home base to come back to somehow. I wonder if you could talk about that for the purposes of this conversation.

TYNER: Well, something’s got to come from someplace, go somewhere, and then return to someplace. Maybe it might be a different place that you ultimately return to. But I think it’s good to have these different dynamic dimensions, to go from here to somewhere, using that as a base, and go somewhere and then from there to return…or to resolve it. Resolution is very important. Sometimes you listen to people and they go into very interesting places, but then they leave you hanging. Where are you going from here? You going to leave me here? Whatever. But I always like to make it a complete journey — a departure, a flight and then a landing. [LAUGHS] Sort of what I do normally when I travel! A good analogy.

TP: You haven’t crashed yet.

TYNER: Hopefully not.

TP: You said you were interested in drums before encountering Saka. Who were some of the trap drummers who were favorites of yours in your pre Coltrane years? I imagine Philly Joe Jones must have been one.

TYNER: Yes. I didn’t know Philly when he was there, though.

TP: Specs Wright.

TYNER: I knew Specs. Philly had left, because he was with Miles — him and Red. But I knew they’d been around Philly a long time. But there were guys from my generation who were around Philly. Tootie Heath. We jammed together. Lex Humphries was there; he left to go with Dizzy, but he was around for a while. A guy named Eddie Campbell, who passed; he was a good Art Blakey style drummer. There were a lot of good guys around who played well. We were very fortunate in that way. I mean, we did have good musicians around.

TP: Were you leading trios around Philly? Actual piano trios? When you did Inception, was that just something you went into the studio and did, or had you put some time into that format?

TYNER: I did some things trio, but not many. When I’d go to Atlantic City, there would usually be a horn player. The first time I went was with Paul Jeffries. Paul came from Philly, and some kind of way Paul got that job in Atlantic City. We worked at a place called King’s Bar. That’s really what it was, a bar. The guy liked my playing so much, he went to Philadelphia and bought a piano. He bought a little spinet. Because his piano was horrible. So Paul and I, we worked together down there for a while.

Then I went down with Lee Morgan. With Eddie Campbell one time. I know once with Lex Humphries. There was a place called the Cotton Club, big-time, that had two stages. Dinah Washington came in, she was on one stage with Wynton Kelly on piano and Jimmy Cobb on piano. Then J.J. Johnson came in with Tootie and Wilbur Little on bass and Tommy Flanagan on piano.

TP: A heady summer.

TYNER: Yes. We spent a couple of summers down in Atlantic City. I think we came back to that same club, the Cotton Club. It was nice, because we’d have jam sessions late at night after everybody got off at the Steel Pier, all the big bands, and they’d converge on this club until dawn. How I learned how to play was hands-on. It wasn’t examining somebody. Just okay, sit down and play for a while, and then when you’re done there’s another piano player, get up and let him sit down and play. So everybody had a chance. When I used to look back and see the line of tenor players that were looking for me to comp, and there would be about ten guys, each looking to play. Then my mother’s shop was a favorite place. And a lot of the homes. Another place called Rittenhouse Hall. This guy loved the music, and he loved to have dances on the weekend. People danced to bebop music. It was the music of that period that I came out of.

TP: You said somewhere that in doing the gigs, you had to learn the tunes of the day by Bird and Dizzy and Clifford Brown and Sonny Rollins. Sonny Stitt might come through and call those tunes, so if you wanted to make the gig, you had to learn the tunes. It was an organic thing. Your quotidian, as they say.