VOLUME FOUR NUMBER ONE

JILL SCOTT

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

DAVID MURRAY

(February 25--March 3)

OLIVER LAKE

(March 4–10)

(March 11-17)

Oliver Nelson needs to be reconsidered by music listeners for what he was - one of the most significant jazz voices of his generation, and an important big band composer and arranger of the 1960s. Perhaps the skill he mastered most keenly was his ability to turn listeners on. As difficult as his music might have been to play, and as hard as it is to analyze, it is extremely easy to listen to.

DON BYRON

(March 18-24)

KENNY GARRETT

(March 25-31)

COLEMAN HAWKINS

(April 1-7)

ELMORE JAMES

(April 8-14)

WES MONTGOMERY

(April 15-21)

FELA KUTI

(April 22-28)

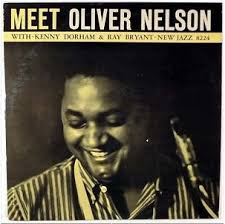

OLIVER NELSON

(April 29-May 5)

SON HOUSE

(May 6-12)

JOHN LEE HOOKER

(May 13-19)

Oliver Nelson

Oliver Nelson needs to be reconsidered by music listeners for what he was - one of the most significant jazz voices of his generation, and an important big band composer and arranger of the 1960s. Perhaps the skill he mastered most keenly was his ability to turn listeners on. As difficult as his music might have been to play, and as hard as it is to analyze, it is extremely easy to listen to.

Born June 4, 1932 in St. Louis, Oliver Nelson came from a musical family: His brother played saxophone with Cootie Williams in the Forties, and his sister was a singer-pianist. Nelson himself began piano studies at age six and saxophone at eleven. In the late ‘40’s he played in various territory bands and then spent 1950-51 with Louis Jordan’s big band. After two years in a Marine Corps ensemble, he returned to St. Louis to study composition and theory at both Washington and Lincoln universities.

After graduation in 1958, Nelson moved to New York and played with Erskine Hawkins, Wild Bill Davis, and Louie Bellson. He also became the house arranger for the Apollo Theatre in Harlem. Though he began recording as a leader in 1959, Nelson’s breakthrough came in 1961 with “The Blues and the Abstract Truth,” (Impulse) featuring an all- star septet of; Eric Dolphy, Bill Evans, Roy Haynes, Paul Chambers and Freddie Hubbard. With the success of that deservedly acclaimed album, Nelson’s career as a composer blossomed, and he was subsequently the leader on a number of memorable big-band recordings, including “Afro-American” (Prestige) and “Full Nelson” (Verve). He also became an in-demand studio arranger, collaborating with Cannonball Adderley, Johnny Hodges, Stanley Turrentine, and others. In addition to dates he led under his own name, he wrote, scored and conducted under the names Leonard Feather's Encyclopedia of Jazz All Stars and the Jazz Impressions Orchestra; did a date for Shirley Scott and another for Ray Brown and Milt Jackson; five sessions with organist Jimmy Smith, including the legendary “Walk on the Wild Side,” another headlined by Smith and Wes Montgomery; and the incomparable Pee Wee Russell. During the Sixties, Nelson became one of the most strongly identifiable writing voices in jazz. Since Nelson was schooled in both the American jazz and European music traditions, his arrangements can be intricate, but when it comes time for a solo, it's clear that Nelson (who was himself a brilliant soloist on tenor alto and soprano saxophone) has fashioned everything as the proper set up for the featured player.

Nelson moved to Los Angeles in 1967, where he became involved extensively in scoring for television and films. It's no wonder Oliver Nelson was so eagerly embraced by Hollywood - his music is all about drama. He loved painting tonal pictures, and his pieces do portray dramatic situations perfectly.

He continued active in jazz and continued to lead an all- star big band in various live performances between 1966 and 1975 in appearances in Berlin, Montreux, New York, and Los Angeles, he also toured West Africa with a small group. Besides composing music for television and films, he was producing and arranging for pop stars such as Nancy Wilson, James Brown, the Temptations, and Diana Ross. Though Nelson continued to write for jazz record dates and play his saxophone, the demands of writing commercial music increased. The accompanying stress ultimately may have been his undoing; on October 28, 1975, he died suddenly of a heart attack.

Source: James Nadal

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/oliver-nelson-mn0000398615/biography

Oliver Nelson

(1932-1975)

Artist Biography by Scott Yanow

Oliver Nelson was a distinctive soloist on alto, tenor, and even soprano, but his writing eventually overshadowed his playing skills. He became a professional early on in 1947, playing with the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra and with St. Louis big bands headed by George Hudson and Nat Towles. In 1951, he arranged and played second alto for Louis Jordan's big band, and followed with a period in the Navy and four years at a university. After moving to New York, Nelson worked briefly with Erskine Hawkins, Wild Bill Davis, and Louie Bellson (the latter on the West Coast). In addition to playing with Quincy Jones' orchestra (1960-1961), between 1959-1961 Nelson recorded six small-group albums and a big band date; those gave him a lot of recognition and respect in the jazz world. Blues and the Abstract Truth (from 1961) is considered a classic and helped to popularize a song that Nelson had included on a slightly earlier Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis session, "Stolen Moments." He also fearlessly matched wits effectively with the explosive Eric Dolphy on a pair of quintet sessions. But good as his playing was, Nelson was in greater demand as an arranger, writing for big band dates of Jimmy Smith, Wes Montgomery, and Billy Taylor, among others. By 1967, when he moved to Los Angeles, Nelson was working hard in the studios, writing for television and movies. He occasionally appeared with a big band, wrote a few ambitious works, and recorded jazz on an infrequent basis, but Oliver Nelson was largely lost to jazz a few years before his unexpected death at age 43 from a heart attack.

http://jazzprofiles.blogspot.com/2010/04/oliver-nelson-interview-by-john-cobley.html

Jazz Profiles

Focused profiles on Jazz and its makers

Saturday, April 10, 2010

OLIVER NELSON INTERVIEW (1972)

By JOHN COBLEY

© -Steven Cerra. Copyright protected; all rights reserved.

I have long thought that had he not died so tragically young at the age of 43 in 1975, Jazz saxophonist, arranger and composer Oliver Nelson may have produced a body or work to warrant consideration as “the Duke Ellington” of the second half of the 20th century.

Given his brief life, Oliver’s arranging and composition talents were prolific, by any standard of judgment. More importantly, his music is exciting and interesting and always fun to listen to, especially in a big band context.

The editorial staff was particularly pleased to be granted copyright permission by Michael Cuscuna of Mosaic Records to use Kenny Berger’s insert notes to their reissue of Oliver Nelson: The Argo, Verve and Impulse Big Band Session [MD6-233] as a September 24, 2008 feature on JazzProfiles.

And subsequently, when John Cobley contacted us and offered his permission to post the following interview with Oliver that he conducted three years before Nelson’s death in 1975, needless to say, we now had reason to become doubly pleased.

John lives in British Columbia. We’ve never met in person, only coming together via the Internet as a result of our common interest in Jazz.

He has had a successful career as a professional writer. In addition to Jazz, another of John’s interests is running. He used to work as a track and field writer. Not surprisingly, then, he is currently “… working on a ‘book’ on running, great runners, coaches and famous races.”

Here’s what John had to say as by way of background to his interview with Oliver:

“Going over it after all these years, I was surprised how well it went and how much Oliver Nelson [ON] opened up to me (a humble student). His frustrations with the "scene" come over quite strongly. I was quite moved by his comment about his black brothers. The first part is rather long (about jazz education),…. Still I think that overall the interview will give those interested in Nelson some useful insights.”

© -John Cobley. Reprinted with the permission of the author; copyright protected; all rights reserved.

SALT LAKE CITY, 1972

In the spring of 1972, Oliver Nelson visited Salt Lake City to work with the University of Utah jazz program. I attended one of his sessions with the university big band. At one point he got out his alto and began a solo; however, after a minute he stopped abruptly, apologizing that the thin air at 5,000 feet was too much for him. (In retrospect, this might well have been an indication of the heart condition that was to end his life three years later.)

After the session I approached Oliver Nelson for an interview. I introduced myself as a third-year student from BYU who had a weekly jazz program on KBYU-FM. He agreed to meet me later at his hotel. Arriving on time, he commented on some “weird looks” he got on the streets of Salt Lake City because of his color. After the interview, he talked to me personally and, giving me his home address, said he would welcome any ideas that I might have for projects he could work on.

Q: First of all, I’d like to ask you about jazz education. I believe you’ve been greatly involved in it for the last few years.

ON: The University of Utah jazz program is only three years old. In that three-year period, enrolment has gone up constantly, to the point that the jazz curriculum is one third in terms of student numbers. And the school felt that they should find some way to merge jazz and the regular music department. However, the regular music dept has nothing to do with the jazz department, and they are worlds apart in concept. Of course, jazz theory and harmony are quite different from European classical theory and harmony. North Texas State’s program is 25 years old and it has been successful for 25 years. But even there they are finding resistance to the jazz program.

Q: Could you define what you mean by successful?

ON: When I went to Washington University in St Louis, we could not even mention the word jazz. So I got a very good classical background—in 16th century harmony. Then in 1966 they invited me back to start a jazz program. It’s as if they are finally seeing that jazz is an important art form. If you are going to teach it, you can’t just pull out an educator and say “Teach jazz.” You have to get people who have been professional musicians, who have traveled. I’ve played with Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Quincy Jones, Louis Bellson, so they said that the logical person is a former student who has gone out and been very successful in the world. It was an honor for me.

Q: Do you think that this gulf between classical and jazz education is getting any narrower?

ON: Jazz programs are bringing a great deal of pressure upon music schools. For instance, emphasis is now on improvisation. As a student, I had a professor at Washington University who said that any music that is improvised is not art. I raised my hand and said, “What about the troubadour songs with mandolins and lutes? Troubadours would go all around Europe singing and improvising. It’s codified in one large book. How do you account for this?” He just told me to see him after class. I got a D in that course. So communication is a big problem because all the heads of music departments have no real knowledge of jazz. Their only option is to bring in professional people to teach it. But professionals like Dizzy Gillespie have the experience but no degrees after their name. So the heads say, “Why should we pay someone like Dizzy Gillespie $25,000 a year to teach when he doesn’t have a Ph. D.?” Well, he doesn’t need one. So lines have to be clearly drawn.

Q: Would you say then that jazz programs have become embarrassingly popular?

ON: That’s right. And that makes it very difficult for the classical part music departments. In one of the reports concerning Dr. Fowler’s resignation here at the University of Utah, the words “domination by the Jazz Department” appeared. Well, that’s a strange word, domination. The University of Utah stage bands have been consistent winners in the festivals; that’s great publicity for the school. You’d think the school would be very happy about it, but somehow they feel very nervous and threatened.

Q: There has been some cross-fertilization between jazz and classical music—Stravinsky for example. Do you think that this cross-fertilization will develop into one musical form?

ON: I think so. Recently there was a review of a piece of mine that was premiered by the Eastman Orchestra at Rochester. It’s a 15-minute piece. And the reviewers didn’t know where it belongs. You can’t tell where the jazz stops and where the classical music begins. So that’s what I’ve been working for in my own career—to try to cross-fertilize. I find it’s happening more and more because of the exposure the jazz musicians are getting and the exposure to rock. They also have to take classical courses, and somehow it rubs off. It goes back and forth. I think it will be a natural thing. And it’s going to take years before we can really see the truth of it. But I hate this resistance that you get in a music department where the classical people don’t speak to the jazz people. It’s wrong, you know.

Q: There is an aloofness to any kind of exuberance in classical music.

ON: Oh, yeah. One good example is this. Zubin Mehta of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. They did a piece of mine maybe two years ago for full orchestra. Zubin was very concerned. He said, “Why is it that you don’t see any black faces at these concerts at the Music Center?” I said that I’d thought about it. So he said, “Why don’t we have the whole symphony orchestra play the high school in the so-called ghetto area of Watts?” And we did this piece of mine there. They also played the first part of The Rite of Spring. And the black kids loved it. So he said, if they won’t go to the Music Center, let’s take the music to them. He’s also changing his program, doing less say of Mozart and Bach. And he will have one concert featuring the music of Lalo Schifrin and Frank Zappa. He’s trying to reach a new audience.

Q: We had him here at Provo. In our interview he seemed concerned with the image of classical music. But most of those involved in classical music don’t seem concerned. They feel people have to rise up to their level. We feel that Mehta has almost been ostracized for his attitude.

ON: He comes down to the grass roots level and tries to reach the people. He says the programming of a normal symphony orchestra is usually bad. People aren’t coming out to hear things that they’ve heard before. So he’s putting on a great deal of new music, and they are giving him a hard time for that. He’s bringing jazz composers into the Music Center to do things with the orchestra; he’s getting problems with that. What’s happening in the universities is almost a parallel with what’s happening with symphony orchestras. Q: So what advice would you give to the heads of university music departments?

ON: To recognize that they will have to deal with it sooner or later. My son, Oliver Junior, who will be 17 soon, is asking where he should go to school and what he should take. I tell him, “You really do need a good classical background, beside what you are going to find out about jazz and everything else. You still need a good basis. I recommended he study classical harmony and theory. But he should also be free to elect to take jazz harmony courses and not have the feeling that the two are separate things. He’s content now to get a good education, one that will give him the best of both worlds.

At the Eastman School of Music, the students decided: they wanted jazz to be taught. And they started the program there two years ago. The students got the head of the music department to resign. The students will have a lot to do with the future. They know what they want. They’ve looked at the world their fathers have given them and said, “The world doesn’t work.” The students will decide that jazz will be taught in the music departments; they may even decide who will teach it. And I think this is a good thing—as long as they don’t burn the place down!

Q: I recently did a talk on the problem of soloing with a big band as opposed to soloing in a small group. Do you have any opinions on this?

ON: I personally prefer small groups. I’m using a synthesizer now and an electric piano. And maybe an electric bass, though I always feel the need for the upright bass. I find that with three good players I can make more music than with a 20-piece orchestra that’s hard to handle because you have to conduct and play at the same time. A large orchestra sort of hems you in. So when I work with a large group I always write places inside the piece where I can play with the rhythm section. And then at some point I’ll scream, “Let’er in” or something, and the orchestra will join me at that point. But I do prefer small groups.

Q: With college bands the ensemble sounds fine, but there is often a letdown when the solos start.

ON: They aren’t developing soloists like they should. They’re developing ensemble groups. This problem has been on my mind. I was at a festival where I heard 80 bands in three days, and I don’t think we heard one outstanding solo. It bothers me because this means that improvisation is not being taught the way it should be in the colleges.

Q: I’m wondering whether it might be better for big-band soloists to have some sort of solo worked out beforehand.

ON: No. Just let it come right off the top of your head.

Q: Even at the college level?

ON? Yeh. I think the blame falls mainly on the educators. The 80 bands were all white bands—very little integration. They had some Orientals and Spanish-speaking kids. But they were playing mostly rock not jazz. Since this was a jazz festival, this was very puzzling to me. When I talked with the band directors, their attitude was that they were trying to play the music of the kids’ generation. Improvisation is not part of their teaching process. So you hear ensemble after ensemble--but no outstanding soloists.

Q: Can you give any comments on the problems students have when they first start composing for jazz orchestra?

ON: First they need to know theory, instrumentation/orchestration. You need to know how to handle all the instruments because not all of them are transposing instruments. It puts a burden on the young composer just to copy the parts because the orchestra is so large. I would personally select smaller ensembles first and then work up to the larger groups.

Q: How did your own career develop?

ON: I started out with piano when I was four and with saxophone when I was 11. I was working professionally when I was 12, touring with a territory band when school was out. After that I went with Louis Jordan’s big band, and then I had to go in the Marine Corps for two years. Public Law 550 provided me the means to get an education so I went to Washington University from 1954 to 1958 and then Jefferson University in Lincoln City, Missouri. Then I got married and went to New York. My first success, I would say, was an album I did for ABC Paramount, Blues and the Abstract Truth. On the basis of that one record, I had created my own sound. It only worked for me. If other people used it, guys would say, “You sound just like Oliver Nelson!” And then I went on to do an album with Jimmy Smith, Walk on the Wild Side. That was a start. After that I was writing more than I was playing. I stayed in New York almost ten years, bought a house on Long Island and had to fight that traffic every day. Then I said, “I think I want more out of life than this. I think I’d like to write for films.” So we moved to California, where I’ve been writing for feature films: Death of a Gunfighter, Zigzag, Skullgduggery.

Q: How did you find satisfaction doing that? I hear that Quincy Jones is giving it up.

ON: He needs money. Well, he’s starting to go very commercial now. That’s what Hollywood can do. So now I’m involved in film writing I do music on a regular basis for Longstreet, for which I created the theme, and do underscores for Ironside and a show called Night Gallery. But I find that’s not enough. I get the feeling that this year is going to be critical because I’ve decided to make my own music available to schools and colleges. I think I am going to do less and less of the other and do more and more in education.

Q: On this album (Leon Thomas in Berlin) I noticed a change in your playing. It seemed to be cathartic, terribly powerful emotionally.

ON: (Laughs) I was having a wonderful time in Berlin, and I guess it shows up on that record. And I don’t play that often. When I do play I just take my saxophone right out of the bag and put it together and play it. I don’t live with it every day. The reason that I can pick up my saxophone and play it is that I am always thinking about it.

Q: We had Don Ellis here recently, and he was talking about Gary Burton, how he practices…

ON: In his head. Right. Same thing. But that album—you’re saying my playing is different. There was a period when my playing was one way and then my playing changed almost over night. I have a Japanese Yamaha saxophone that they gave me in Tokyo three years ago. And then I have a German mouthpiece which has an adjustable chamber inside. The Japanese instrument is so good that it enables me to go outside the well-tempered whatever. I can play as high as I want. My French Selmer saxophone wouldn’t allow me to do that because it was too good. It’s like owning a Rolls Royce, but you wouldn’t enter it in a race.

Q: But there’s a purity in your playing in that recording. I don’t know whether it’s a change in your style….

ON: I think it’s happened inside me.

Q: …as though you felt content within yourself and confident that you had no need to prove yourself. Could you make any comments on this album?

ON: Leon Thomas is also from St. Louis. He’s always talking about “Back to Africa.” And I’ve been to Africa, and I’m saying Africa is not where it is. He has never been there, and he’s talking about the Mother Country! The one thing that I found out about Africa is that it was not alien in the true sense. But there’s such a difference in the cultures that I said that the place to start thinking about making a living is in this country, America, although Africa was very nice to visit. Maybe that has something to do with my playing on this album too. It gave me a chance to focus on things I hadn’t thought about. As you can see I had on a dashiki for the occasion. But that’s not the normal way I play. It used to be suits and ties, but I can’t do that anymore.

Q: What do you think about this African movement in Jazz—Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane—although their music is perhaps more North African and Indian?

ON: Well, it’s the same thing I’ve mentioned earlier. They’ve never been there. I thought that in going to Africa we would find some black faces and we would be able to exchange things musically. But in the major portion of my tour there, in the capital cities, we didn’t find one person who could play any jazz. And then I started to think about it: was American slavery the catalyst that was needed in order to make this music? Why did it only happen her and nowhere else? It didn’t happen in the Virgin Islands. It didn’t happen with the Africans who went to South America. Why did jazz only happen here? Maybe slavery was the answer. The records of Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane are very commercial. And when I say commercial, it’s that people are now trying to identify with something. So Pharoah Sanders sells quite a few records. But I don’t know if that’s how he really feels about it.

Q: I have a theory which I’d like to put to you. I’ve read that rather hysterical book by Frank Kofsky (Nelson laughs, “Oh, Frank”) and the rather better one by Ben Sidran, Black Talk….

ON: I don’t know that one.

Q: …and it seems to me that through the history of jazz the black musician has created a style and the white man has come along and copied it.

ON: That’s true.

Q: And each time that has happened, the black musician, to keep his individuality, has to jump to something different.

ON: This is very true because one of the things I ask young players when I meet them is, “Have you ever heard of Charlie Parker?” They say no. Then I look at the band instructor and wonder how the hell he can teach jazz. Another man, who will remain nameless, if I would say Charlie Parker, he would say Lee Konitz. If I would say Duke Ellington, he would say Stan Kenton. If I would say John Coltrane, he would say Stan Getz. He didn’t realize that he was trying to have a complete division, saying this was white jazz, cool jazz. Of course, what Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were doing, that was black jazz. And I hate to think of jazz being that kind of music. As long as politics can stay out of it, I think music in this country will be very, very healthy. If I were white composer, I would have been totally famous and a millionaire by now. But it takes me longer. I have to prove myself every time I write a film score. Every time I stand in front of an integrated orchestra, I’ve got to know what I’m doing. Whereas you can get other people—Chuck Mangione, I don’t know if you’ve heard of him--he’s a big success because of some album he did with the Eastman Rochester Orchestra. There’s no music there. But you hear Chuck’s name on the radio constantly, that he’s gonna be the man of the future. Someone said that everyone is still looking for the great white hope. I hate to think of music in those terms.

Q: In Europe we respect you for what you are.

ON: In Europe it’s different. Why do you think I go to Berlin and have such a wonderful time? Because of the music, first of all. I can write anything for a German audience. I know I can extend my thoughts and do this and that, and I don’t have to be commercial.

Q: Why is there a difference then?

ON: I don’t know. It’s a complete reverse in Europe. Phil Woods, he goes to Europe and he feels he is being discriminated against because they think of him as a good white saxophone player. He says all the black musicians over there get drunk and they can’t play, but everybody leaves them alone because of their contribution to music. Over here Phil Woods was sought after, but in Europe….especially in France…they said before he died Sidney Bechet would play so badly some nights because he was sick, but people loved him just the same. He didn’t have to prove himself; he’d done that years ago. But Europe is lovely. I haven’t been to London yet. I always stop there to change planes. I can’t work there because British musicians would have to go to the States. In a country like Finland they play very, very good and play jazz as close as they can play it. I’m going to Norway this summer. Music can speak in an international way to all people. But over here we have Shaft. Everybody’s saying that’s the way all movie scores should be written. I don’t agree. You have to write for the picture. Now the Shaft fad has taken Hollywood by storm. This country is very faddish. I somehow come through it all. I just go through the whole period, and I don’t change my style and I don’t change my ideals of what music should be. As a result I hear people say I’m one of the few who have not sold out yet. And they’re waiting for me, waiting for me to sell out.

Q: Do you feel bitter?

ON: No, I just feel that the music business in this country is geared to the lowest common denominator. Do you know what they call me, my black brothers? They call me a white musician. They call me a white composer. It’s because I’m always trying to do something. I couldn’t stay with Shaft just to prove how black I am. So I write all kinds of twelve-tone music. I write from my experiences through my education, and now I’m putting together my own thing. And if it goes outside their spectrum, they say, “You’re thinking white.” You should see my last score; I showed it to Gerald Wilson this morning. It’s Berlin Dialogue. He said it looks like a road map! I said exactly what it is. I just give players places to start and stop. Driving from here, you have to take directions and know what turn-off to take. This is the way I think about improvisation. I don’t want to tell a player what to play, but I give him certain road maps and signs, and he can do whatever he wants as long as he is does it during this period. And he says you’re giving him too much freedom, but I say that every time we play this piece it sounds pretty much the same. And that’s what I wanted. I didn’t want everybody just playing anything they wanted to play; I wanted to control it just a little—enough to have the same performance time and time again.

Q: At a certain point jazz suddenly became serious. I wondered if you knew why.

ON: They were trying to make it respectable. It started with John Lewis and the Third Stream. It was because most of the musicians were going back to school, and they were studying with people who were saying, “In order to make a good piece you have to go about it in this manner.” And it came out sounding serious. When jazz musicians write for a jazz orchestra—saxophones and trumpets-- they write one way, and when they have a chance to write for a symphony orchestra--strings--they write in a completely different style. And then you wonder why. Is it because respect for the symphony orchestra makes you write that kind of piece? My piece for Zubin was very rhythmic and I left a place inside the piece for me to improvise. The only thing I did was use the larger orchestra. When I write for a symphony orchestra, I think about the piece and what I want to do. But I only go about it in a bigger way. I don’t get serious about it. My music comes right off the top, you know.

Q: There is another kind of seriousness, which is almost a religious seriousness. Coltrane for example.

ON: John Coltrane approached his music from that standpoint. He was very serious about it, but serious in that sense doesn’t mean pretentious. Maybe he knew he was going to die. Towards the end he was getting more and more involved in thinking about life. And then he dies, and that was the end of it. Pharoah Sanders has this quality also—music as a religion. Eric Dolphy was like that too—always serious about his work. I understand what you mean by seriousness that takes on a spiritual quality.

Q: I wonder if it started earlier. Lester Young had his religious conscience nagging him.

ON: Listen. I have a religious conscience nagging me.

Q: But why didn’t it happen in the twenties?

ON: Well, everybody was having such a good time. It’s almost like if you go out and get drunk, the next day you feel like you’ve committed a sin—especially when your head hurts and you feel rotten. And you probably did commit a sin because you hurt your body. But John Coltrane was a very nice person, and he had a great deal of respect for other people’s work. Pharoah Sanders called me a couple of months ago to do an album for him. That’s one of the projects I hope to be working on soon. I don’t know what kind of project it will be. With him, his music is not ordered in a sense but is ordered, and with me working with a large a group over which I have to have some control, how do we put Pharoah Sanders in the middle and have it come out meaning something? It’ll be a project to work on.

Jazz Profiles

Focused profiles on Jazz and its makers

Saturday, April 10, 2010

OLIVER NELSON INTERVIEW (1972)

By JOHN COBLEY

© -Steven Cerra. Copyright protected; all rights reserved.

I have long thought that had he not died so tragically young at the age of 43 in 1975, Jazz saxophonist, arranger and composer Oliver Nelson may have produced a body or work to warrant consideration as “the Duke Ellington” of the second half of the 20th century.

Given his brief life, Oliver’s arranging and composition talents were prolific, by any standard of judgment. More importantly, his music is exciting and interesting and always fun to listen to, especially in a big band context.

The editorial staff was particularly pleased to be granted copyright permission by Michael Cuscuna of Mosaic Records to use Kenny Berger’s insert notes to their reissue of Oliver Nelson: The Argo, Verve and Impulse Big Band Session [MD6-233] as a September 24, 2008 feature on JazzProfiles.

And subsequently, when John Cobley contacted us and offered his permission to post the following interview with Oliver that he conducted three years before Nelson’s death in 1975, needless to say, we now had reason to become doubly pleased.

John lives in British Columbia. We’ve never met in person, only coming together via the Internet as a result of our common interest in Jazz.

He has had a successful career as a professional writer. In addition to Jazz, another of John’s interests is running. He used to work as a track and field writer. Not surprisingly, then, he is currently “… working on a ‘book’ on running, great runners, coaches and famous races.”

Here’s what John had to say as by way of background to his interview with Oliver:

“Going over it after all these years, I was surprised how well it went and how much Oliver Nelson [ON] opened up to me (a humble student). His frustrations with the "scene" come over quite strongly. I was quite moved by his comment about his black brothers. The first part is rather long (about jazz education),…. Still I think that overall the interview will give those interested in Nelson some useful insights.”

© -John Cobley. Reprinted with the permission of the author; copyright protected; all rights reserved.

SALT LAKE CITY, 1972

In the spring of 1972, Oliver Nelson visited Salt Lake City to work with the University of Utah jazz program. I attended one of his sessions with the university big band. At one point he got out his alto and began a solo; however, after a minute he stopped abruptly, apologizing that the thin air at 5,000 feet was too much for him. (In retrospect, this might well have been an indication of the heart condition that was to end his life three years later.)

After the session I approached Oliver Nelson for an interview. I introduced myself as a third-year student from BYU who had a weekly jazz program on KBYU-FM. He agreed to meet me later at his hotel. Arriving on time, he commented on some “weird looks” he got on the streets of Salt Lake City because of his color. After the interview, he talked to me personally and, giving me his home address, said he would welcome any ideas that I might have for projects he could work on.

Q: First of all, I’d like to ask you about jazz education. I believe you’ve been greatly involved in it for the last few years.

ON: The University of Utah jazz program is only three years old. In that three-year period, enrolment has gone up constantly, to the point that the jazz curriculum is one third in terms of student numbers. And the school felt that they should find some way to merge jazz and the regular music department. However, the regular music dept has nothing to do with the jazz department, and they are worlds apart in concept. Of course, jazz theory and harmony are quite different from European classical theory and harmony. North Texas State’s program is 25 years old and it has been successful for 25 years. But even there they are finding resistance to the jazz program.

Q: Could you define what you mean by successful?

ON: When I went to Washington University in St Louis, we could not even mention the word jazz. So I got a very good classical background—in 16th century harmony. Then in 1966 they invited me back to start a jazz program. It’s as if they are finally seeing that jazz is an important art form. If you are going to teach it, you can’t just pull out an educator and say “Teach jazz.” You have to get people who have been professional musicians, who have traveled. I’ve played with Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Quincy Jones, Louis Bellson, so they said that the logical person is a former student who has gone out and been very successful in the world. It was an honor for me.

Q: Do you think that this gulf between classical and jazz education is getting any narrower?

ON: Jazz programs are bringing a great deal of pressure upon music schools. For instance, emphasis is now on improvisation. As a student, I had a professor at Washington University who said that any music that is improvised is not art. I raised my hand and said, “What about the troubadour songs with mandolins and lutes? Troubadours would go all around Europe singing and improvising. It’s codified in one large book. How do you account for this?” He just told me to see him after class. I got a D in that course. So communication is a big problem because all the heads of music departments have no real knowledge of jazz. Their only option is to bring in professional people to teach it. But professionals like Dizzy Gillespie have the experience but no degrees after their name. So the heads say, “Why should we pay someone like Dizzy Gillespie $25,000 a year to teach when he doesn’t have a Ph. D.?” Well, he doesn’t need one. So lines have to be clearly drawn.

Q: Would you say then that jazz programs have become embarrassingly popular?

ON: That’s right. And that makes it very difficult for the classical part music departments. In one of the reports concerning Dr. Fowler’s resignation here at the University of Utah, the words “domination by the Jazz Department” appeared. Well, that’s a strange word, domination. The University of Utah stage bands have been consistent winners in the festivals; that’s great publicity for the school. You’d think the school would be very happy about it, but somehow they feel very nervous and threatened.

Q: There has been some cross-fertilization between jazz and classical music—Stravinsky for example. Do you think that this cross-fertilization will develop into one musical form?

ON: I think so. Recently there was a review of a piece of mine that was premiered by the Eastman Orchestra at Rochester. It’s a 15-minute piece. And the reviewers didn’t know where it belongs. You can’t tell where the jazz stops and where the classical music begins. So that’s what I’ve been working for in my own career—to try to cross-fertilize. I find it’s happening more and more because of the exposure the jazz musicians are getting and the exposure to rock. They also have to take classical courses, and somehow it rubs off. It goes back and forth. I think it will be a natural thing. And it’s going to take years before we can really see the truth of it. But I hate this resistance that you get in a music department where the classical people don’t speak to the jazz people. It’s wrong, you know.

Q: There is an aloofness to any kind of exuberance in classical music.

ON: Oh, yeah. One good example is this. Zubin Mehta of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. They did a piece of mine maybe two years ago for full orchestra. Zubin was very concerned. He said, “Why is it that you don’t see any black faces at these concerts at the Music Center?” I said that I’d thought about it. So he said, “Why don’t we have the whole symphony orchestra play the high school in the so-called ghetto area of Watts?” And we did this piece of mine there. They also played the first part of The Rite of Spring. And the black kids loved it. So he said, if they won’t go to the Music Center, let’s take the music to them. He’s also changing his program, doing less say of Mozart and Bach. And he will have one concert featuring the music of Lalo Schifrin and Frank Zappa. He’s trying to reach a new audience.

Q: We had him here at Provo. In our interview he seemed concerned with the image of classical music. But most of those involved in classical music don’t seem concerned. They feel people have to rise up to their level. We feel that Mehta has almost been ostracized for his attitude.

ON: He comes down to the grass roots level and tries to reach the people. He says the programming of a normal symphony orchestra is usually bad. People aren’t coming out to hear things that they’ve heard before. So he’s putting on a great deal of new music, and they are giving him a hard time for that. He’s bringing jazz composers into the Music Center to do things with the orchestra; he’s getting problems with that. What’s happening in the universities is almost a parallel with what’s happening with symphony orchestras. Q: So what advice would you give to the heads of university music departments?

ON: To recognize that they will have to deal with it sooner or later. My son, Oliver Junior, who will be 17 soon, is asking where he should go to school and what he should take. I tell him, “You really do need a good classical background, beside what you are going to find out about jazz and everything else. You still need a good basis. I recommended he study classical harmony and theory. But he should also be free to elect to take jazz harmony courses and not have the feeling that the two are separate things. He’s content now to get a good education, one that will give him the best of both worlds.

At the Eastman School of Music, the students decided: they wanted jazz to be taught. And they started the program there two years ago. The students got the head of the music department to resign. The students will have a lot to do with the future. They know what they want. They’ve looked at the world their fathers have given them and said, “The world doesn’t work.” The students will decide that jazz will be taught in the music departments; they may even decide who will teach it. And I think this is a good thing—as long as they don’t burn the place down!

Q: I recently did a talk on the problem of soloing with a big band as opposed to soloing in a small group. Do you have any opinions on this?

ON: I personally prefer small groups. I’m using a synthesizer now and an electric piano. And maybe an electric bass, though I always feel the need for the upright bass. I find that with three good players I can make more music than with a 20-piece orchestra that’s hard to handle because you have to conduct and play at the same time. A large orchestra sort of hems you in. So when I work with a large group I always write places inside the piece where I can play with the rhythm section. And then at some point I’ll scream, “Let’er in” or something, and the orchestra will join me at that point. But I do prefer small groups.

Q: With college bands the ensemble sounds fine, but there is often a letdown when the solos start.

ON: They aren’t developing soloists like they should. They’re developing ensemble groups. This problem has been on my mind. I was at a festival where I heard 80 bands in three days, and I don’t think we heard one outstanding solo. It bothers me because this means that improvisation is not being taught the way it should be in the colleges.

Q: I’m wondering whether it might be better for big-band soloists to have some sort of solo worked out beforehand.

ON: No. Just let it come right off the top of your head.

Q: Even at the college level?

ON? Yeh. I think the blame falls mainly on the educators. The 80 bands were all white bands—very little integration. They had some Orientals and Spanish-speaking kids. But they were playing mostly rock not jazz. Since this was a jazz festival, this was very puzzling to me. When I talked with the band directors, their attitude was that they were trying to play the music of the kids’ generation. Improvisation is not part of their teaching process. So you hear ensemble after ensemble--but no outstanding soloists.

Q: Can you give any comments on the problems students have when they first start composing for jazz orchestra?

ON: First they need to know theory, instrumentation/orchestration. You need to know how to handle all the instruments because not all of them are transposing instruments. It puts a burden on the young composer just to copy the parts because the orchestra is so large. I would personally select smaller ensembles first and then work up to the larger groups.

Q: How did your own career develop?

ON: I started out with piano when I was four and with saxophone when I was 11. I was working professionally when I was 12, touring with a territory band when school was out. After that I went with Louis Jordan’s big band, and then I had to go in the Marine Corps for two years. Public Law 550 provided me the means to get an education so I went to Washington University from 1954 to 1958 and then Jefferson University in Lincoln City, Missouri. Then I got married and went to New York. My first success, I would say, was an album I did for ABC Paramount, Blues and the Abstract Truth. On the basis of that one record, I had created my own sound. It only worked for me. If other people used it, guys would say, “You sound just like Oliver Nelson!” And then I went on to do an album with Jimmy Smith, Walk on the Wild Side. That was a start. After that I was writing more than I was playing. I stayed in New York almost ten years, bought a house on Long Island and had to fight that traffic every day. Then I said, “I think I want more out of life than this. I think I’d like to write for films.” So we moved to California, where I’ve been writing for feature films: Death of a Gunfighter, Zigzag, Skullgduggery.

Q: How did you find satisfaction doing that? I hear that Quincy Jones is giving it up.

ON: He needs money. Well, he’s starting to go very commercial now. That’s what Hollywood can do. So now I’m involved in film writing I do music on a regular basis for Longstreet, for which I created the theme, and do underscores for Ironside and a show called Night Gallery. But I find that’s not enough. I get the feeling that this year is going to be critical because I’ve decided to make my own music available to schools and colleges. I think I am going to do less and less of the other and do more and more in education.

Q: On this album (Leon Thomas in Berlin) I noticed a change in your playing. It seemed to be cathartic, terribly powerful emotionally.

ON: (Laughs) I was having a wonderful time in Berlin, and I guess it shows up on that record. And I don’t play that often. When I do play I just take my saxophone right out of the bag and put it together and play it. I don’t live with it every day. The reason that I can pick up my saxophone and play it is that I am always thinking about it.

Q: We had Don Ellis here recently, and he was talking about Gary Burton, how he practices…

ON: In his head. Right. Same thing. But that album—you’re saying my playing is different. There was a period when my playing was one way and then my playing changed almost over night. I have a Japanese Yamaha saxophone that they gave me in Tokyo three years ago. And then I have a German mouthpiece which has an adjustable chamber inside. The Japanese instrument is so good that it enables me to go outside the well-tempered whatever. I can play as high as I want. My French Selmer saxophone wouldn’t allow me to do that because it was too good. It’s like owning a Rolls Royce, but you wouldn’t enter it in a race.

Q: But there’s a purity in your playing in that recording. I don’t know whether it’s a change in your style….

ON: I think it’s happened inside me.

Q: …as though you felt content within yourself and confident that you had no need to prove yourself. Could you make any comments on this album?

ON: Leon Thomas is also from St. Louis. He’s always talking about “Back to Africa.” And I’ve been to Africa, and I’m saying Africa is not where it is. He has never been there, and he’s talking about the Mother Country! The one thing that I found out about Africa is that it was not alien in the true sense. But there’s such a difference in the cultures that I said that the place to start thinking about making a living is in this country, America, although Africa was very nice to visit. Maybe that has something to do with my playing on this album too. It gave me a chance to focus on things I hadn’t thought about. As you can see I had on a dashiki for the occasion. But that’s not the normal way I play. It used to be suits and ties, but I can’t do that anymore.

Q: What do you think about this African movement in Jazz—Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane—although their music is perhaps more North African and Indian?

ON: Well, it’s the same thing I’ve mentioned earlier. They’ve never been there. I thought that in going to Africa we would find some black faces and we would be able to exchange things musically. But in the major portion of my tour there, in the capital cities, we didn’t find one person who could play any jazz. And then I started to think about it: was American slavery the catalyst that was needed in order to make this music? Why did it only happen her and nowhere else? It didn’t happen in the Virgin Islands. It didn’t happen with the Africans who went to South America. Why did jazz only happen here? Maybe slavery was the answer. The records of Pharoah Sanders and Alice Coltrane are very commercial. And when I say commercial, it’s that people are now trying to identify with something. So Pharoah Sanders sells quite a few records. But I don’t know if that’s how he really feels about it.

Q: I have a theory which I’d like to put to you. I’ve read that rather hysterical book by Frank Kofsky (Nelson laughs, “Oh, Frank”) and the rather better one by Ben Sidran, Black Talk….

ON: I don’t know that one.

Q: …and it seems to me that through the history of jazz the black musician has created a style and the white man has come along and copied it.

ON: That’s true.

Q: And each time that has happened, the black musician, to keep his individuality, has to jump to something different.

ON: This is very true because one of the things I ask young players when I meet them is, “Have you ever heard of Charlie Parker?” They say no. Then I look at the band instructor and wonder how the hell he can teach jazz. Another man, who will remain nameless, if I would say Charlie Parker, he would say Lee Konitz. If I would say Duke Ellington, he would say Stan Kenton. If I would say John Coltrane, he would say Stan Getz. He didn’t realize that he was trying to have a complete division, saying this was white jazz, cool jazz. Of course, what Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were doing, that was black jazz. And I hate to think of jazz being that kind of music. As long as politics can stay out of it, I think music in this country will be very, very healthy. If I were white composer, I would have been totally famous and a millionaire by now. But it takes me longer. I have to prove myself every time I write a film score. Every time I stand in front of an integrated orchestra, I’ve got to know what I’m doing. Whereas you can get other people—Chuck Mangione, I don’t know if you’ve heard of him--he’s a big success because of some album he did with the Eastman Rochester Orchestra. There’s no music there. But you hear Chuck’s name on the radio constantly, that he’s gonna be the man of the future. Someone said that everyone is still looking for the great white hope. I hate to think of music in those terms.

Q: In Europe we respect you for what you are.

ON: In Europe it’s different. Why do you think I go to Berlin and have such a wonderful time? Because of the music, first of all. I can write anything for a German audience. I know I can extend my thoughts and do this and that, and I don’t have to be commercial.

Q: Why is there a difference then?

ON: I don’t know. It’s a complete reverse in Europe. Phil Woods, he goes to Europe and he feels he is being discriminated against because they think of him as a good white saxophone player. He says all the black musicians over there get drunk and they can’t play, but everybody leaves them alone because of their contribution to music. Over here Phil Woods was sought after, but in Europe….especially in France…they said before he died Sidney Bechet would play so badly some nights because he was sick, but people loved him just the same. He didn’t have to prove himself; he’d done that years ago. But Europe is lovely. I haven’t been to London yet. I always stop there to change planes. I can’t work there because British musicians would have to go to the States. In a country like Finland they play very, very good and play jazz as close as they can play it. I’m going to Norway this summer. Music can speak in an international way to all people. But over here we have Shaft. Everybody’s saying that’s the way all movie scores should be written. I don’t agree. You have to write for the picture. Now the Shaft fad has taken Hollywood by storm. This country is very faddish. I somehow come through it all. I just go through the whole period, and I don’t change my style and I don’t change my ideals of what music should be. As a result I hear people say I’m one of the few who have not sold out yet. And they’re waiting for me, waiting for me to sell out.

Q: Do you feel bitter?

ON: No, I just feel that the music business in this country is geared to the lowest common denominator. Do you know what they call me, my black brothers? They call me a white musician. They call me a white composer. It’s because I’m always trying to do something. I couldn’t stay with Shaft just to prove how black I am. So I write all kinds of twelve-tone music. I write from my experiences through my education, and now I’m putting together my own thing. And if it goes outside their spectrum, they say, “You’re thinking white.” You should see my last score; I showed it to Gerald Wilson this morning. It’s Berlin Dialogue. He said it looks like a road map! I said exactly what it is. I just give players places to start and stop. Driving from here, you have to take directions and know what turn-off to take. This is the way I think about improvisation. I don’t want to tell a player what to play, but I give him certain road maps and signs, and he can do whatever he wants as long as he is does it during this period. And he says you’re giving him too much freedom, but I say that every time we play this piece it sounds pretty much the same. And that’s what I wanted. I didn’t want everybody just playing anything they wanted to play; I wanted to control it just a little—enough to have the same performance time and time again.

Q: At a certain point jazz suddenly became serious. I wondered if you knew why.

ON: They were trying to make it respectable. It started with John Lewis and the Third Stream. It was because most of the musicians were going back to school, and they were studying with people who were saying, “In order to make a good piece you have to go about it in this manner.” And it came out sounding serious. When jazz musicians write for a jazz orchestra—saxophones and trumpets-- they write one way, and when they have a chance to write for a symphony orchestra--strings--they write in a completely different style. And then you wonder why. Is it because respect for the symphony orchestra makes you write that kind of piece? My piece for Zubin was very rhythmic and I left a place inside the piece for me to improvise. The only thing I did was use the larger orchestra. When I write for a symphony orchestra, I think about the piece and what I want to do. But I only go about it in a bigger way. I don’t get serious about it. My music comes right off the top, you know.

Q: There is another kind of seriousness, which is almost a religious seriousness. Coltrane for example.

ON: John Coltrane approached his music from that standpoint. He was very serious about it, but serious in that sense doesn’t mean pretentious. Maybe he knew he was going to die. Towards the end he was getting more and more involved in thinking about life. And then he dies, and that was the end of it. Pharoah Sanders has this quality also—music as a religion. Eric Dolphy was like that too—always serious about his work. I understand what you mean by seriousness that takes on a spiritual quality.

Q: I wonder if it started earlier. Lester Young had his religious conscience nagging him.

ON: Listen. I have a religious conscience nagging me.

Q: But why didn’t it happen in the twenties?

ON: Well, everybody was having such a good time. It’s almost like if you go out and get drunk, the next day you feel like you’ve committed a sin—especially when your head hurts and you feel rotten. And you probably did commit a sin because you hurt your body. But John Coltrane was a very nice person, and he had a great deal of respect for other people’s work. Pharoah Sanders called me a couple of months ago to do an album for him. That’s one of the projects I hope to be working on soon. I don’t know what kind of project it will be. With him, his music is not ordered in a sense but is ordered, and with me working with a large a group over which I have to have some control, how do we put Pharoah Sanders in the middle and have it come out meaning something? It’ll be a project to work on.

http://jazzprofiles.blogspot.com/2008/09/oliver.html

Oliver Nelson was a brilliant saxophonist, composer, arranger and orchestrator – a gift of Jazz – who was taken away from us much too soon.

Oliver Nelson was a brilliant saxophonist, composer, arranger and orchestrator – a gift of Jazz – who was taken away from us much too soon.

Thursday, September 4, 2008

Oliver Nelson

© -Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Oliver Nelson was a brilliant saxophonist, composer, arranger and orchestrator – a gift of Jazz – who was taken away from us much too soon.

Oliver Nelson was a brilliant saxophonist, composer, arranger and orchestrator – a gift of Jazz – who was taken away from us much too soon.

Thanks to the Mosaic Records reissue of Oliver Nelson: The Argo, Verve and Impulse Big Band Sessions [MD6-233], we have the opportunity to once again sample Oliver in all his magnificence along with the marvelous studio musicians who made his brilliance shine with even more luster.

Saxophonist Kenny Berger assembled a wealth of information in preparation for an M.A. Thesis on Oliver at Rutgers University. He used a great deal of this accumulated information to write the wonderfully perceptive insert notes for the Mosaic release and the editorial staff at Jazzprofiles is delighted to be able to share the introductory portion of his essay as its homage to Oliver.

[C] Mosaic Records, copyright protected; all rights reserved. Used with permission.

In his notes, Kenny provides insights into [1] what made Oliver’s Jazz writing so powerfully unique, [2] the technical skills required of a studio musician to be able to play and interpret Oliver’s work, [3] why it was especially important to have an improvising background in dealing with Oliver’s “charts” [arrangements], and [4] what the now “lost world” of a musician’s life was like in the Hollywood and New York studios during their heyday in the 1960s.

“Oliver Nelson was one of the most complete and multifaceted musicians in Jazz. In today's jazz world, the term ..multifaceted" more often than not tends to describe someone who dabbles in several different musical styles, stirring a little "world music" (ugh, what a horrible term), a little hip-hop, a little new age, etc., into a bland, boring stew. Oliver Nelson was a world-class jazz saxophonist and composer-arranger, as well as a distinguished composer of orchestral and chamber music in non-jazz idioms, and a prolific composer of scores for television and feature films. He operated at the top of the profession in all these fields and his work always bore his personal stamp. His personal and artistic integrity was reflected in everything he did and, as will be explained later, was a contributing factor in his tragic, premature death.

These notes are written from the perspective of a saxophonist and composer-arranger who was a teenaged aspiring musician during the time of the earliest recordings in this set, and a professional with one foot in the door to the jazz and studio recording scenes during the time of the later ones. I was also a student of Danny Bank, who played baritone saxophone and woodwinds on most of these sessions and since then, I have had the privilege of playing alongside roughly 80 percent of the musicians on these dates. During the late 1990s, as a middle-aged candidate for a Masters degree in Jazz History and Research at Rutgers University, I chose Oliver Nelson as my thesis subject, accumulating a wealth of musical and personal information on him that I am pleased to finally share with the world.

Oliver Edward Nelson was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on June 4, 1932, the youngest of four siblings in a musical family. His Portuguese maternal grandfather was an amateur musician who was adept on a variety of instruments; his older brother Eugene Nelson Jr. played alto saxophone with Cootie Williams' big band during the 1940s; and his sister Leontine was a professional pianist-vocalist in the St. Louis area. He entered the music profession as a teenager during the late 1940s, at a time when several of the best-known territory bands in the Midwest were on their last legs. The Jeter-Pillars, George Hudson and Nat Towles bands, all with sterling reputations dating back to the Swing Era, were based in or around St. Louis at the time and Nelson played with all three bands while still in his teens. He originally set out to be a lead alto saxophonist and his early idols were Willie Smith, Otto Hardwicke and Johnny Hodges. He made his recording debut at age 19 as lead altoist with Louis Jordan's short-lived big band in 1951. As a teenager he also played with Eddie Randall, a St. Louis trumpeter and bandleader who was instrumental in the development of many young local musicians including Miles Davis. Randall's family was also in the funeral home business, a fact that sheds some light on a mysterious bit of longstanding Nelson arcana. A brief article in Down Beat magazine early in Nelson's career made a passing reference to the fact that, in addition to his musical training. he had also studied taxidermy and embalming. No further explanation was given, and this bit of trivia, with its aspects Of BLUES AND THE ABSTRACT TRUTH meets Six Feet Under, seemed to take on a life of its own.

It turns out that Nelson was unsure about pursuing music as a career while a member of Randall's band, wound up learning mortuary science from him, and later worked at one of the Randall family's funeral homes, as well as for the Ellis funeral homes, a large local chain.

From March 1952 to March 1954 Nelson served in the U.S. Marine Corps in Japan and Korea as a member of the Third Division Band. His formal study of composition began later in 1954 at Washington University in St. Louis and continued at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. Altoist Phil Woods, who was one of his closest friends and favorite sidemen, recalled that when he studied at Washington, Nelson chose to eat lunch in his car rather than deal with the school's segregated dining halls, and years later, in a stroke of supreme irony, returned to the campus as a guest lecturer.

Nelson moved to New York in 1959. Some of his first gigs there were with big bands led by Erskine Hawkins and Louie Bellson and with a commercial Jazz group called Quartet Tres Bien. In the summer of that year, he played in Atlantic City, New Jersey, with organist Wild Bill Davis' trio, the third member of which was Grady Tate, who became Nelson's drummer of choice when both their recording careers took off. During 1959 and '60, he subbed for brief periods in both the Duke Ellington and Count Basic bands, playing alto with Ellington, and tenor with Basle. The first recording to feature his big band writing was an Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis UP, TRANE WHISTLE, done for Prestige in 1960. This album also included the first recording of STOLEN MOMENTS, which a couple of years later would become Nelson's best-known composition. At this time he also served as staff arranger for the house band at the Apollo Theater. The band was lead by Reuben Phillips, a saxophonist who had been his section mate in the Louis Jordan band.

He continued to record for Prestige, doing several small group dates and in 1961, his first album of original big band music, AFRO-AMERICAN SKETCHES, a suite inspired by the black experience beginning in Africa and continuing through slavery and emancipation. Earlier in 1961 Nelson recorded the album that put him on the map, both as a player and a composer, BLUES AND THE ABSTRACT TRUTH for Impulse! It was an all-star date by a septet featuring Freddie Hubbard, Eric Dolphy, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers and Roy Haynes, with Nelson on tenor and alto, and George Barrow on baritone. This album featured the classic version of STOLEN MOMENTS and the cluster harmonies used in the arrangement became identified with Nelson from then on. It was also his first collaboration with producer Creed Taylor, who soon began employing him as a virtual house arranger for the Verve label.

The point in time when the recordings in this set were made represent roughly the mid to late period of the last golden age of studio recording in New York. The top players would customarily do, on average, three record dates each day and could be called upon to play in almost any style at any time. Dates were booked in three-hour increments with, in many cases, a fourth "possible hour" in case some overtime was needed. Of course, due to the demands of the marketplace, a good deal of the music one would encounter during an average week of studio work would vary in quality and a good deal of it was pure commercial garbage. This tended to make opportunities to play quality music that much more of a relief, and the ratio of good music to bad got exponentially smaller as time went on. By the 1970s it seemed as though the main ingredients for success as a studio arranger or producer had become sartorial, rather than musical. As saxophonist-arranger-author Bill Kirchner has written, recordings like those heard here were products of a studio system that has largely disappeared, and if they were done today, they would had to have been paid for out of the artist's own pocket.

Despite the consistently high level of musicianship and the difficulty of much of the music, the bands on these sessions were not working bands in the sense of being on the road, or even playing a live gig once a week. Separate rehearsals were usually out of the question. Nelson's writing often made extraordinary demands on the players, so it was essential for him to have players he could rely on to meet those demands. His writing for the reed section in particular demanded wide-ranging versatility. He made more frequent and imaginative use of the clarinet section than most other jazz arrangers, which stemmed from his classical training, his love of Duke Ellington, and the fact that he was a good clarinetist himself. Albums such as FULL NELSON and PETER AND THE WOLF required a good deal of doubling on various flutes, and oboe and English horn, as well as clarinet and bass clarinet, while requiring the same players to comprise a first-rate sax section, often in the course of the same arrangement.

The consistency of the personnel on Nelson's dates allowed him to utilize the Ellingtonian concept of conceiving both solos and ensemble parts with individual players in mind. The lynchpins of Oliver's reed sections were lead altoist Phil Woods and baritonist Danny Bank. Bill Kirchner has perceptively pointed out that Nelson employed Woods and Bank in the same way that Ellington employed Johnny Hodges and Harry Carney: both as section lead and anchor respectively, and as distinctive individual voices. Nelson was aware of the fact that even when no improvisation is required, a player who can improvise, even if not a world-class soloist, can always interpret a written part in the jazz idiom better than one who can't. Phil Bodner, Romeo Penque and Stan Webb were former big band saxophonists. all of whom played flute, oboe and clarinet on a level equal to that of top-drawer classical players, and Bodner was a first-rate jazz soloist as well. In the brass section, bass trombonist Tony Studd and tuba player Don Butterfield were, at the time, virtually the only players in the studio freelance pool on their respective horns who were jazz improvisers, which made them far superior to their peers at playing written parts with true jazz feeling, an advantage also enjoyed by lead trumpeters Ernie Royal and Snooky Young.

In addition to his status as an arranger and player of the first rank, Nelson became important in jazz education with the publication of several of his big band works and his influence on saxophonists became widespread due to popularity of his self-published book of saxophone exercises, Patterns for Saxophone. He wrote the book originally for his own use and the story of its origin falls under the heading of "You can't make this stuff up." During his stint with Wild Bill Davis in 1959, the group played a gig on a cruise ship. At one point in the voyage, rough seas and foul weather caused the ship's generators to go haywire, causing the electrical power levels onboard to fluctuate wildly. This in turn caused Davis' Hammond organ to change pitch uncontrollably and unpredictably, forcing Nelson to have to constantly transpose in order to stay in the right key. This experience made him aware that needed to improve his facility in all 12 keys, hence the book.

As his writing commitments usually left him virtually no practice time, he would practice out of his own book whenever he needed to get his chops into shape quickly. Most of the book's exercises take a particular melodic pattern and run it through all the keys. One example consists of a series of 12 tone rows in various transpositions and several others contain the melodies of tunes that appear on different recordings. Several passages and complete tunes in this set are derived from examples in this book and many of the patterns were, and still are, part of the vocabulary of many important players.

Nelson's experience and status as a first-rate player who was often featured on other arrangers' projects as well as his own, made him an ideal choice to provide backing for jazz soloists of all stylistic persuasions. No one has a better idea of what works and what doesn't behind a jazz soloist than a writer who is a Jazz soloist.

The list of soloists for whom Nelson provided stimulating frameworks includes Cannonball Adderley, Johnny Hodges, Cal Tjader, Sonny Rollins, Kai Winding, Lee Morgan, Stanley Turrentine and vocalists such as Louis Armstrong (including the ubiquitous IT”S A WONDERFUL WORLD, Louis' last recording, with stowaway Ornette Coleman singing in the vocal choir), Carmen McRae, Etta Jones, Joe Williams and Nancy Wilson.

Nelson moved to Los Angeles in 1965 in order to break into TV and film scoring, maintaining a bicoastal lifestyle for awhile as he combined recording work in New York scoring work in L.A. His first steady scoring work was for the NBC-TV series Ironside in 1967. The show was produced by Universal Television, whose music supervisor, Stanley Wilson, was supportive of jazz musicians and had helped jumpstart the scoring careers of J.J. Johnson and Benny Golson. Nelson went on to score several other TV and soon fell into a dangerous and eventually fatal trap. He maintained a lavish home while sending his two sons through college and paying to support his older brother, who had developed physical and mental problems that required institutional care. This led him to take on a backbreaking workload, which was, ironically made worse by his own professional integrity. In those pre-digital days, TV and film scores were still performed by groups of human beings, requiring the creation of fully written scores from which individual parts were then extracted. It was standard practice for the composer, after having written the for an episode, to then direct the recording sessions.

The field was notorious for imposing insanely tight deadlines. Virtually every composer involved in this work wrote his scores in the form of a sketch and employed orchestrators who were familiar with the composer's style, to flesh them out into full scores. It was considered physically impossible to do otherwise, due to the dangerously long periods of sleep deprivation it would require, but Nelson insisted on writing every note himself and was unique in never employing the services of an orchestrator. In addition, Nelson's younger son, jazz flutist Oliver Nelson Jr., believes that his father contracted malaria on a tour of Africa in 1969, and that it may have permanently weakened his immune system. On October 27, 1975, Nelson was conducting a recording session for an episode of the TV series The Six Million Dollar Man, after working out the timing of the musical cues, composing and orchestrating every note and delivering the score to a copyist all within a span of 36 hours. At the end of the date, as pianist-composer Mike Melvoin, the keyboardist on the date, described it, "He went to the date, looked really bad ... needless to say, and I think it was Vince DeRosa, the French horn player, [who] said 'You don't look good, man. You should go home, or even go to the hospital, go to the emergency room, check in or whatever.” He said, No, No, I’m going home right now’ and I think he had his heart attack on the way home.”

Though all the press reports listed the cause of death as a heart attack, Oliver Nelson Jr. confirms the actual cause of death as pancreatitis, a breakdown of fatty acids in the liver, resulting in instantaneous shock and rapid death. According to Melvoin, Nelson’s tragic death served as a cautionary tale, causing more than a few overworked Hollywood composers to alter their work habits.”

WRTI

Oliver Nelson, the composer and jazz saxophonist, who had not performed in New York for eight years, has come from California to lead an 18‐piece band at the Bottom Line, where, at his opening on Monday, he struck a blow for sanity in sound levels.

Many talented souls in various walks of life have departed the planet well before their loved ones thought they should have. The abbreviated stays of the gifted makes us ponder what other wonders they might have contributed, had they lived.

Oliver Nelson comes to mind. He was less famous than Clifford Brown or Charlie Parker or John Coltrane, all of whom were innovators and pioneers and who died well before their time. But Nelson was not only a gifted multi-instrumentalist but also a top-flight arranger and composer. He advanced the careers of many performers, and not just those in jazz.

I first heard of Nelson in the early 1960s via his composition “Stolen Moments,” which became a jazz classic. A few years later I broke into radio and began hosting a jazz program. He then became an even more familiar name to me, because I played his music on the air.

Oliver Nelson’s “Stolen Moments” with Nelson on tenor saxophone, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, et al.:

Oliver Nelson was born into a musical family on June 4, 1932 in St. Louis. He played piano at age six, and several years later, the saxophone. He got his first major job with Louis Jordan while still in his teens, playing alto saxophone and arranging. Military service called, and he joined a band in the Marine Corps. While traveling in Tokyo, he heard the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, which he credited with whetting his appetite to become more advanced as an arranger.

After the military, Nelson studied harmony and theory at Washington and Lincoln Universities and privately. He moved to New York City and made music with Erskine Hawkins, organist Wild Bill Davis and a host of other established musicians. He also landed a job as house arranger for the Apollo Theater.

The word was that he had literally worked himself to death.

Prestige Records signed Nelson to a contract, and he recorded six albums for them. He later moved to the Impulse label and recorded The Blues and the Abstract Truth, a landmark LP that included “Stolen Moments.” It’s a work of art. With the likes of pianist Bill Evans, bassist Paul Chambers, drummer Roy Haynes, Eric Dolphy doubling on also sax and flute, Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, and Nelson on tenor sax—how could it not be the monster that it was? It still is.

Doors began to open. Not only was he producing and arranging for Nancy Wilson, James Brown, the Temptations, Diana Ross, organist Jimmy Smith, and other well-known artists, he was also composing for TV shows, including Ironside, Longstreet, and The Six Million Dollar Man (for which he wrote the theme). He also arranged the music for the motion picture Last Tango in Paris.

Those close to him knew he was spreading his gargantuan talents too thin by racing from the East Coast to perform with his jazz group, then to the West Coast for music-arranging jobs. Their concern for his well-being turned out not to be an abstract truth: Nelson suffered a massive heart attack in Los Angeles in 1975, and died at the age of 43. The word was that he had literally worked himself to death. So, Oliver Nelson, like some of his ever-youthful jazz predecessors, left while still having much more to say. But he, like they, kicked up a lot of creative dust prior to departing.

One of his best CDs (besides The Blues and the Abstract Truth) is one he shares with vibraphonist Lem Winchester, Nocturne. Oliver Nelson’s solos on “Azur’te” and “Man with a Horn” please the ear and massage the heart.

Oliver Nelson, the composer and jazz saxophonist, who had not performed in New York for eight years, has come from California to lead an 18‐piece band at the Bottom Line, where, at his opening on Monday, he struck a blow for sanity in sound levels.

After his band's first number had been turned into a disastrous hodge‐podge of thunderous crashes and crackles by the technician in charge of amplification, Mr. Nelson stopped everything while he coaxed the man on the sound board to lower the level on the piano until it began to sound somewhat like a piano instead of a garbage truck gone berserk. Then the guitar was reduced. Mr. Nelson let it go at that, but he might usefully have continued his reduction because the band, although it had some degree of clarity, was still so loudly amplified that the various elements tended to obscure another.