SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2016

VOLUME THREE NUMBER TWO

ERIC DOLPHYAN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2016

VOLUME THREE NUMBER TWO

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

BOBBY HUTCHERSON

September 10-16

GEORGE E. LEWIS

September 17-23

JAMES BLOOD ULMER

September 24-30

RACHELLE FERRELL

October 1-7

ANDREW HILL

October 8-14

CARMEN McRAE

(October 15-21)

PRINCE

(October 22-28)

LIANNE LA HAVAS

(October 29-November 4)

ANDRA DAY

(November 5-November 11)

ARCHIE SHEPP

(November 12-18)

WORLD SAXOPHONE QUARTET

(November 19-25)

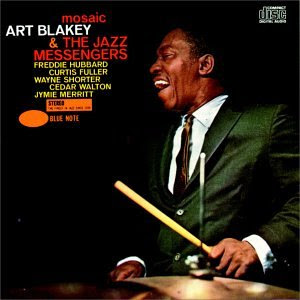

ART BLAKEY

(November 26-December 2)

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/art-blakey-the-musical-drummer-art-blakey-by-anton-rasmussen.php

Art Blakey: The Musical Drummer

by

"Jazz Washes Away the Dust of Everyday Life" —Art Blakey

So said, Abdullah Ibn Buhaina (1919-1990), more widely known to the world of jazz by his pre-Islamic name: Art Blakey.

Blakey was my first introduction into the musicality of jazz drumming

and, in some senses, my introduction to a lifelong love of jazz.

Truly

a powerhouse in swing and blues, Blakey led the hard bop playing Jazz

Messengers from the 1950s to the 1980s (recording for Blue Note Records between 1947 and 1964), and holding claim to famous alumni such as Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Bill Pierce, Branford Marsalis, and Chuck Mangione, to name but a few.

A Piano Player Turned Drummer

Art Blakey

began drumming, as many people know, in a way that transcends the light

air of his feather bass drumming and soft touch of his ride cymbal

comping: by being held at gunpoint at a Pittsburgh

joint called The Democratic Club in the mid 1930's; forced to give up

his seat at the piano he'd been playing and made to play the drums, this

would begin a six decade career for Blakey as one of jazz drumming's

greats.

The Musical Drummer

Though Blakey was a force to be reckoned with on the drum set, playing in the style of Chick Webb and Big Sid Catlett,

don't let that make you think he couldn't be musical. Yes, yes, we've

all heard the drummer jokes (like, what do they call the guy that hangs

around musicians? A drummer!); but, as a bandleader and drummer, Blakey

always played in the most musical way; he always served the song. In

fact, this is the aspect of his drumming that most draws one in—and the

reason I was drawn to his drumming while studying music theory.

All one has to do is listen to Blakey's arrangements to know just how musical a drummer can be.

Drummer

jokes aside, it's not a rule that drummers can't be musical leaders. In

fact, some of the best drummers in the world are also great band

leaders. And Blakey was one of those great bandleader/great

drummer/great musician types. He played for over 60 years and inspired

generations to look at drumming in a new way: with an ear toward the

music; always placing the music first. But the converse is also true,

According to Chris Kelsey, "Blakey's influence as a bandleader could not

have been nearly so great had he not been such a skilled

instrumentalist." 4

According to Wynton Marsalis, graduate of the Blakey School for Swing and a very notable trumpeter, "On the eighth day, God created Art Blakey." 1 Such was the esteem given to a man greater at his job than most before or after.

A Teacher of Time

Whether

you're listening to the rolling tomtoms and snare solo of "Sakeena's

Vision" (truly a lesson in keeping a straight pulse on the hats while

throwing fills around the kit—signature Blakey to be sure) or you're

desperately trying to find the proper place for the bass drum kicks on Thelonious Monk's "Humph," Blakey is there to teach. And his lessons all come from a place of tremendous experience.

Listening

to 1947's "Humph" and 1981's "Cheryl," one quickly finds that Blakey's

style changed drastically over time and followed the development of

jazz. So, it wouldn't necessarily be fair to say that Blakey had one

style of drumming—in fact, he created many styles during his long

career.

According to John Ramsay,

"When you compare the two [time periods], I think you can hear how

Art's style grew and evolved over the years. The 1947 recording shows a

style more like that of the 1930's and 1940's, whereas the 1981

recording is like that of the be-bop and hard bop style that Art helped

create." 1

And that's really what we get with Art Blakey:

the creation of music from the seat of a drum throne. He always seemed

to be doing something new. To prove Blakey's willingness to be the

first—at anything, really—there's a fun little trivia fact that, in

1960, Blakey's Jazz Messengers actually became the first American jazz

band to play in Japan—this would begin a relationship with the Japanese

people that would persist for decades. 1

An Indestructible Introduction to Musical Drumming

The album that first introduced me to Art Blakey was his last Blue Note Records album, Indestructible (Blue Note, 1965). The lineup for Indestructible consisted of the following players:

Lee Morgan: Trumpet

Curtis Fuller: Trombone

Wayne Shorter: Tenor Saxophone

Cedar Walton: Piano

Reggie Workman: Bass

Art Blakey: Drums

The reason I was likely introduced to Blakey with Indestructible

is because I spent several months while I was at Berklee learning the

drum part to "The Egyptian." The infamous "Blakey Triplets" open up Indestructible

and introduce the listener to what goes on to be a full on be-bop/blues

album with some of the most catching drum work one will find in the

jazz community—and all of it is musical. 3

My

introduction to jazz came at a time when I wanted to learn as much as I

could about music—to me, jazz was all about learning music. So, if jazz

music is the learning musician's go-to genre, there isn't a better

introduction to musical jazz drumming than listening to Art Blakey.

Fortunately,

for those who seek the knowledge Blakey has to offer, there are

countless interviews and conversations with Mr. Blakey around the

Internet. His insight into the world of music will be sure to provide

the same amount of benefit to you as it did to me.

Some Musical Drumming Lessons to Learn

The

following is but a small sample of Blakey's vast discography; however,

there are elements from each of these albums and songs that will lead

one through the musical landscapes that defined Art Blakey's drumming

(all of these recommendations are taken from the outstanding drum

lessons of John Ramsay from Art Blakey's Jazz Messages.) 1

Blakey Triplets: "The Egyptian" Indestructible

(Blue Note, 1965). The intro has a really musically interesting feel to

it. As I noted above, it was this part that introduced me to how

musical Blakey was as a drummer.

Comping with Small Fills: "Lester Left Town" The Big Beat

(Blue Note, 1960). Blakey plays hits on the tomtom during the trumpet

solo—it's a great example of Blakey's ability to comp. Sure, it's a

small part; but, it fits so well into the trumpet solo while the

trumpeter (Hubbard, I believe) hits a staccato one note patterned fill.

Polyrhythmic Ideas: "A Night in Tunisia" A Night in Tunisia

(Blue Note, 1960). During the intro to this song, Blakey develops

polyrhythms with the toms and various percussive elements. Blakey brings

the polyrhythmic feel back during the trumpet solo (using the snare and

crash), which is just fantastic! It was here, during this trumpet solo,

that I first learned how one could musically use the 3 against 4

polyrhythm within a swing context.

Call and Response: "Honeysuckle Rose" The Unique Thelonious Monk (Riverside, 1956). Several times during this song, Blakey and Monk do call and response figures. It's really a fun listen!

1Art Blakey's Jazz Messages, by John Ramsay, (Manhattan Music, 1994)

Art Blakey

Born in 1919, Art Blakey began his musical career, as did many jazz musicians, in the church. The foster son of a devout Seventh Day Adventist Family, Art learned the piano as he learned the Bible, mastering both at an early age.

But as Art himself told it so many times, his career on the piano ended at the wrong end of a pistol when the owner of the Democratic Club—the Pittsburgh nightclub where he was gigging—ordered him off the piano and onto the drums.

Art, then in his early teens and a budding pianist, was usurped by an equally young, Erroll Garner who, as it turned out, was as skilled at the piano as Blakey later was at the drums. The upset turned into

a blessing for Art, launching a career that spanned six decades and nurtured the careers of countless other jazz musicians.

As a young drummer, Art came under the tutelage of legendary drummer and bandleader Chick Webb, serving as his valet. In 1937, Art returned to Pittsburgh, forming his own band, teaming up with Pianist Mary Lou Williams, under whose name the band performed.

From his Pittsburgh gig, Art made his way through the Jazz world. In 1939, he began a three-year gig touring with Fletcher Henderson. After a year in Boston with a steady gig at the Tic Toc club, he joined the great Billy Eckstine, gigging with the likes of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sarah Vaughn.

In 1948, Art told reporters he had visited Africa, where he learned polyrhythmic drumming and was introduced to Islam, taking the name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina. It was in the late ’40s that Art formed his first Jazz Messengers band, a 17-piece big band.

After a brief gig with Buddy DeFranco, in 1954 Art met up with pianist Horace Silver, altoist Lou Donaldson, trumpeter Clifford Brown, and bassist Curly Russell and recorded “live” at Birdland for Blue Note Records. The following year, Art and Horace Silver co-founded the quintet that became the Jazz Messengers. In 1956, Horace Silver left the band to form his own group leaving the name, the Jazz Messengers, to Art Blakey.

Art’s driving rhythms and his incessant two and four beat on the high hat cymbals were readily identifiable from the outset and remained a constant throughout 35 years of Jazz Messengers bands. What changed constantly was a seeming unending supply of talented sidemen, many of whom went on to become band leaders in their own right.

In the early years luminaries like Clifford Brown, Hank Mobley and Jackie McLean rounded out the band. In 1959, tenor saxophonist Benny Golson joined the quintet and—at Art’s behest—began working on the songbook and recruiting what became one of the timeless Messenger bands—tenor saxman Wayne Shorter, trumpeter Lee Morgan, pianist Bobby Timmons and bassist Jymmie Merritt.

The songs produced from ’59 through the early ’60s became trademarks for the Messengers ?” including Timmon’s Moanin’, Golson’s Along Came Betty and Blues March and Shorter’s Ping Pong.

By this time, the Messengers had become a mainstay on the jazz club circuit and began recording on Blue Note Records. They began touring Europe, with forays into North Africa. In 1960, the Messengers became the first American Jazz band to play in Japan for Japanese audiences. That first Japanese tour was a high point for the band. At the Tokyo airport, the band was greeted by hundreds of fans as Blues March played over their airport intercom and their visit was televised nationally.

In 1961, trombonist Curtis Fuller transformed the Messengers into a proper sextet, giving the band the opportunity to incorporate a big band sound into their hard bop repertoire. Throughout the ’60s, the Messengers remained a mainstay on the jazz scene with jazz greats including Cedar Walton, Chuck Mangione, Keith Jarrett, Reggie Workman, Lucky Thompson and John Hicks. In the jazz drought of the ’70s, the Messengers remained a strong force, with fewer recordings, but no less energy. At a time when many jazz musicians were experimenting with electronics and fusing their music with pop, the Messengers were a mainstay of straight-ahead jazz.

Art’s steadfast belief in jazz music left him well positioned to take advantage of the music’s resurgence in the early ’80s. Art had been working with musicians including trumpeter Valery Ponomarev, tenor Billy Pierce, alto saxman Bobby Watson and pianist James Williams. Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis’ 1980 entrance into the band coincided—and played no small part in—the resurgence of the music in the ’80s.

Throughout the ’80 and until his death in 1990, Art maintained the integrity of the message, incubating the careers of musicians including trumpeters Wallace Rooney and Terence Blanchard, pianists Mulgrew Miller and Donald Brown, bassists Peter Washington and Lonnie Plaxico and many others.

Art died at the age of 71 after a career that spanned six of the best decades of jazz music. The messenger has moved on, but his message lives on in the music of the scores of sidemen whose careers he nurtured, the many other drummers he mentored and countless fans who have been blessed to hear the Messengers’ music.

Source: Yawu Miller

But as Art himself told it so many times, his career on the piano ended at the wrong end of a pistol when the owner of the Democratic Club—the Pittsburgh nightclub where he was gigging—ordered him off the piano and onto the drums.

Art, then in his early teens and a budding pianist, was usurped by an equally young, Erroll Garner who, as it turned out, was as skilled at the piano as Blakey later was at the drums. The upset turned into

a blessing for Art, launching a career that spanned six decades and nurtured the careers of countless other jazz musicians.

As a young drummer, Art came under the tutelage of legendary drummer and bandleader Chick Webb, serving as his valet. In 1937, Art returned to Pittsburgh, forming his own band, teaming up with Pianist Mary Lou Williams, under whose name the band performed.

From his Pittsburgh gig, Art made his way through the Jazz world. In 1939, he began a three-year gig touring with Fletcher Henderson. After a year in Boston with a steady gig at the Tic Toc club, he joined the great Billy Eckstine, gigging with the likes of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sarah Vaughn.

In 1948, Art told reporters he had visited Africa, where he learned polyrhythmic drumming and was introduced to Islam, taking the name Abdullah Ibn Buhaina. It was in the late ’40s that Art formed his first Jazz Messengers band, a 17-piece big band.

After a brief gig with Buddy DeFranco, in 1954 Art met up with pianist Horace Silver, altoist Lou Donaldson, trumpeter Clifford Brown, and bassist Curly Russell and recorded “live” at Birdland for Blue Note Records. The following year, Art and Horace Silver co-founded the quintet that became the Jazz Messengers. In 1956, Horace Silver left the band to form his own group leaving the name, the Jazz Messengers, to Art Blakey.

Art’s driving rhythms and his incessant two and four beat on the high hat cymbals were readily identifiable from the outset and remained a constant throughout 35 years of Jazz Messengers bands. What changed constantly was a seeming unending supply of talented sidemen, many of whom went on to become band leaders in their own right.

In the early years luminaries like Clifford Brown, Hank Mobley and Jackie McLean rounded out the band. In 1959, tenor saxophonist Benny Golson joined the quintet and—at Art’s behest—began working on the songbook and recruiting what became one of the timeless Messenger bands—tenor saxman Wayne Shorter, trumpeter Lee Morgan, pianist Bobby Timmons and bassist Jymmie Merritt.

The songs produced from ’59 through the early ’60s became trademarks for the Messengers ?” including Timmon’s Moanin’, Golson’s Along Came Betty and Blues March and Shorter’s Ping Pong.

By this time, the Messengers had become a mainstay on the jazz club circuit and began recording on Blue Note Records. They began touring Europe, with forays into North Africa. In 1960, the Messengers became the first American Jazz band to play in Japan for Japanese audiences. That first Japanese tour was a high point for the band. At the Tokyo airport, the band was greeted by hundreds of fans as Blues March played over their airport intercom and their visit was televised nationally.

In 1961, trombonist Curtis Fuller transformed the Messengers into a proper sextet, giving the band the opportunity to incorporate a big band sound into their hard bop repertoire. Throughout the ’60s, the Messengers remained a mainstay on the jazz scene with jazz greats including Cedar Walton, Chuck Mangione, Keith Jarrett, Reggie Workman, Lucky Thompson and John Hicks. In the jazz drought of the ’70s, the Messengers remained a strong force, with fewer recordings, but no less energy. At a time when many jazz musicians were experimenting with electronics and fusing their music with pop, the Messengers were a mainstay of straight-ahead jazz.

Art’s steadfast belief in jazz music left him well positioned to take advantage of the music’s resurgence in the early ’80s. Art had been working with musicians including trumpeter Valery Ponomarev, tenor Billy Pierce, alto saxman Bobby Watson and pianist James Williams. Trumpeter Wynton Marsalis’ 1980 entrance into the band coincided—and played no small part in—the resurgence of the music in the ’80s.

Throughout the ’80 and until his death in 1990, Art maintained the integrity of the message, incubating the careers of musicians including trumpeters Wallace Rooney and Terence Blanchard, pianists Mulgrew Miller and Donald Brown, bassists Peter Washington and Lonnie Plaxico and many others.

Art died at the age of 71 after a career that spanned six of the best decades of jazz music. The messenger has moved on, but his message lives on in the music of the scores of sidemen whose careers he nurtured, the many other drummers he mentored and countless fans who have been blessed to hear the Messengers’ music.

Source: Yawu Miller

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/art-blakey-and-the-jazz-messengers-moanin-by-mike-oppenheim.php

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: Moanin'

by MIKE OPPENHEIM

March 19, 2013

AllAboutJazz

Throughout its history, jazz has constantly evolved, developing from and reacting against its earlier incarnations. The mid-1940s saw bebop reinvent jazz as an artist's genre, distinct from the swing style that was the popular music throughout the 1930s and '40s. Bebop was music for listening, not dancing, and the emphasis became virtuosic improvised solos instead of memorable tunes and arrangements. However, the advent of bebop itself led to further reactions and developments within jazz during the 1950s. The newer genre again divided; cool jazz became a reaction against bebop, while hard bop maintained much of the bebop aesthetic.

Hard bop players continued in the bebop idiom by emphasizing improvisation, swinging rhythms, and an aggressive, driving rhythm section. Hard bop artists retained bebop's standard song forms of 12-bar blues and 32-bar forms as well as the preference for small combos consisting of a rhythm section plus one or two horns.

One of the premier hard bop artists and, in fact, the one who coined the term with the 1956 album Hard Bop, is drummer and bandleader Art Blakey. His band, the Jazz Messengers, was an extremely talented and influential group from its conception. Blakey formed the Jazz Messengers in 1953 with pianist Horace Silver, but, with the group's personnel constantly changing, few artists spent an extended period. This frequent turnover resulted in Blakey consistently working with the talented youth on the jazz scene. His band served as a developmental stage for future bandleaders including Hank Mobley, Kenny Dorham, Freddie Hubbard, Lee Morgan, Chuck Mangione, Jackie McLean, Wayne Shorter, Cedar Walton, Wynton Marsalis, Benny Golson, and Bobby Timmons.

On October 30, 1958 Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers recorded the album Moanin' at Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey for the Blue Note label. Moanin' is one of the most influential and important hard bop albums due to its outstanding compositions, arrangements, and personnel. The quintet at this time consisted of Pittsburgh native Art Blakey on drums, trumpeter Lee Morgan, tenor saxophonist Benny Golson, bassist Jymie Merritt, and pianist Bobby Timmons, all from Philadelphia. Benny Golson wrote the arrangements and contributed four of the album's six tracks. The title track, "Moanin,'" composed by pianist Bobby Timmons, became the greatest hit of Blakey's lengthy career.

Despite being only twenty years old at the time of the recording, Lee Morgan had already spent two years touring with Dizzy Gillespie's band. His improvisational contributions are indispensable to the sound of the album. Morgan and Benny Golson carry the melodic and solo responsibilities as the only horns in the band. Clifford Brown strongly influenced Morgan's style, characterized by an aggressive rhythmic attack, long melodic phrases, and a brassy timbre.

Golson performed with artists such as Tadd Dameron, Lionel Hampton, and Johnny Hodges before joining the Dizzy Gillespie band on a tour of South America from 1956-58, the same years Morgan played for Gillespie. Golson's tunes "Are You Real?," "Along Came Betty," "The Drum Thunder Suite," and "Blues March" lend a notable variety and versatility to Moanin', utilizing varied song forms and musical styles. As an improviser, Golson's smooth tone and fluid lines contrast with and complement the aggressive playing of Lee Morgan.

Morgan and Golson provide a solid frontline, but the Jazz Messengers rhythm section drives the band and propels the soloists to ever higher levels. Pianist Bobby Timmons, a jazz veteran who played with Kenny Dorham's Jazz Prophets, Chet Baker, Sonny Stitt, and Maynard Ferguson, composed the title track and consistently makes his presence felt through his tasteful comping and solos. Duke Ellington's bassist Jimmy Blanton especially inspired the Jazz Messenger's Jymie Merritt, though he studied formally with a member of the Philadelphia Symphony at the Ornstein Music School. His first gigs were with Tadd Dameron, Benny Golson, John Coltrane, Philly Joe Jones, and, from 1955- 57, he toured with blues artist B.B. King, Merritt provides the bass lines and rhythmic punctuation depending on the style of the song and is featured as a soloist several times throughout the album.

Drummer and bandleader Art Blakey provides the aggressive, driving pulse that propels the Jazz Messengers and is so characteristic of the hard bop style. Blakey was 39 at the time of this recording, the Jazz Messengers had already progressed through several lineups, and Blakey remained the only constant. Despite the changing personnel, the Jazz Messengers remained the archetypal hard bop group, characterized by an emphasis on the blues roots of the music. Blakey is notable for his aggressive drumming, use of polyrhythm, musical interactions with his soloists, and his personality. Blakey felt strongly that jazz was underappreciated in America and he sought to bring it to a broader audience. As a bandleader, he provided his musicians with ample space for solos and encouraged them to contribute compositions and arrangements. He constantly added new talent to his band and made no effort to prevent musicians from leaving the Jazz Messengers.

This combination of Pennsylvania born musicians collaborated to record one of the milestones of hard bop. The track listing includes Bobby Timmons' "Moanin';" Benny Golson's "Are You Real?," "Along Came Betty," "The Drum Thunder Suite," and "Blues March;" and a single standard, Arlen and Mercer's "Come Rain or Come Shine." The selection of songs for Moanin' demonstrates the variety of styles in which the Jazz Messengers comfortably performed. The album features aspects of blues, funky jazz, Latin-American music, and New Orleans style marching bands.

The song "Moanin'" is one of the tunes that helped to generate the "soul jazz" style of the late '50s and early '60s. Influenced by gospel, "Moanin'" makes use of call-and-response technique between the piano and horns. Instead of a walking bass, Merritt plays a rhythmically driving bass line, while Blakey plays a swing rhythm with emphasis on beats two and four. Morgan, Golson, and Timmons all play two-chorus solos followed by one chorus by Jymie Merritt. Morgan's solo makes use of blues inflections and maintains its cohesion through the use of catchy riffs. Golson proceeds into his solo from the end of Morgan's and uses a similar riff-based approach. Timmons continues in a bluesy style, alternating piano runs with chords, and progressing to develop upon a series of formulaic riffs. "Moanin'" concludes with the return of the head and a short piano tag. This song is a prime example of funky or soul jazz.

Benny Golson's "Drum Thunder Suite" was composed to satisfy Blakey's desire to record a song using mallets extensively. The suite consists of three contrasting themes. The first theme, "Drum Thunder," is primarily a drum solo with horns playing short melodic ideas in unison (soli writing). The second theme, "Cry a Blue Tear," utilizes a strongly Latin rhythm in the drums. It features a lyrical melody with trumpet and saxophone playing complementary lines. The final theme, "Harlem's Disciples," begins with a funky melody, and then a piano solo sets the stage for the concluding drum solo. "The Drum Thunder Suite" makes interesting use of different stylistic approaches and arranging techniques.

"Blues March," also composed by Benny Golson, is intended to invoke the spirit of a marching band, with the drums clearly marking all four beats of the measure. The rhythm section is minimally invasive in this tune, and all of the listener's attention is drawn to the soloist. Morgan and Golson play typically bluesy choruses, though Bobby Timmons' solo is the highlight of the track. His solo begins with a simple line, developing into an exciting, chordal conclusion.

Golson's "Are You Real?" is a more straightforward hard bop tune featuring a 32-bar chorus and a faster tempo. The standard "Come Rain or Come Shine" is performed with the attention to melody and arrangement not typically associated with hard bop, but is convincingly and faithfully represented by the Jazz Messengers.

Moanin' is one of hard bop's seminal albums due to the extremely high quality of the personnel and compositions featured. The mastery with which Lee Morgan and Benny Golson provide the frontline is further elevated by the solidarity of Timmons, Merritt, and Blakey. It is a testament to the great quality of the performers, compositions, and the hard bop genre. The accessibility of the album is surely a result of Art Blakey's desire to promote jazz as an art at a time when public interest in the music was waning, and the genre as a whole was threatened by the popularity of emerging musical styles such as doo-wop and rock and roll.

Track Listing: Moanin'; Are You Real?; Along Came Betty; The Drum Thunder Suite; Blues March; Come Rain or Come Shine.

Personnel: Art Blakey: drums; Lee Morgan: trumpet; Benny Golson: tenor saxophone; Bobby Timmons: piano; Jymie Merritt: bass.

Year Released: 1958

| Record Label: Blue Note Records

| Style: Straight-ahead/Mainstream

https://www.nationaljazzarchive.co.uk/stories?id=102

Art Blakey: Interview 1

Interview One: One of the Extroverts of Jazz

Les Tomkins talks to the American bandleader and drummer in 1963, 1973, and again in 1987 in three separate interviews.

Interview: 1963

Source: Jazz Professional

Photograph: Courtesy of Bernhard Castiglioni

He has always believed in self–expression—beyond that contained in the distinctive drive of his drumming. During the ’fifties, when the ‘cool school’ was tending to turn jazz playing inwards, the Blakey Messengers were in the forefront of those who blazed a trail back to a more demonstrative, uninhibited idiom. No holds were barred in the struggle to achieve this end.

He has employed verbal as well as musical methods to attack apathy. On more than one occasion in the night clubs he has been known to harangue the customers for paying insufficient attention to the music.

The same persistent bee has been in the Blakey bonnet in relation to concert audiences in the States. “They don’t listen,” he complains. “They are there because it’s supposed to be hip to be there.

They go to be seen—but not to see what you have to offer.” Commercialism also provokes Art.

Referring to TV producers he has come up against who have doubted whether jazz is a saleable product he adds: “This is very bad. This hurts. We need these facilities to reach the public but we run into this kind of obstacle. We’ll overcome it. The breakthrough will come.

Maybe not in my time—but in the time of the fellows coming behind.” He is equally critical of certain musicians when he says: “We have a lot of so–called jazz groups today. They fool the public. It’s got to swing—and it’s always going to be that way. You cannot change it around.

“And there’s no sense in anyone thinking that you can just take a bum out of the street, put a tuxedo on him, send him into a hall and he’s a gentleman. He’s not a gentleman—he’s just a bum with a tuxedo on !” Being dependent for a large portion of his livelihood on club work, he has found cause for dissatisfaction with the way they are organised. As he puts it: “A lot of club–owners get the idea that they know more about music than the musicians and pretty soon they close up.

“There was this guy who owned one of the main clubs in Chicago that was booking most of the attractions.

He got so hip, he thought he was the king–pin, that nobody could do without him. He thought he was the most important thing in jazz. But he wasn’t. He was just a club–owner. He got so that he said he wasn’t going to pay this and that. These people who put prices on the groups always fail miserably. They cannot put a price on talent.

“Then they get some ‘original’ ideas and think they can do a Norman Granz and throw musicians together who have never played together before. And it fails. The public that we have now has gotten used to organised music. You can’t jam any more. There are only a few undisciplined groups out that people come to hear—and that’s only because of their novelty value.

“It’s getting now that record dates have got to be properly organised. And on appearances the group’s got to look good. They used to say of the bebop musician that he was raggetty and looked like a bum. This is passé today. Now they’re looking for groups that look, act, dress and play organised. There’s not too many of them yet, so they try to fill up with these ‘new form’ groups or groups thrown together.

“If the club–owners would co–operate with the agents they’d be much better off. But they’ll go into New York, see the individual musician and talk him into forming a group for a club date. He’ll pick up some men, and they’ve never played together. They go there and play—but the people won’t buy it, and you can’t blame them. Then the club has to charge exorbitant prices to keep going—and the customers won’t buy that either.

“It doesn’t help us to build up more groups. If they’d book the organised groups that the agencies have and wouldn’t book the others unless they got organised, then we’d have much better groups: Because we have plenty, plenty material.

“Musicians are coming from everywhere to New York City, from different parts of the States, from England, Germany, France—all over the world.

“It used to be, a few years ago, that everybody wanted to be the leader of his own group. Now this idea has died out and a lot of musicians are lackadaisical.

Somebody has to come and crack the whip.

“You see, after the Messengers, the MJQ, Horace Silver or any of these well–organised groups come through with their arrangements, it makes it pretty hard for the others. The people know the difference now.

“We battled this thing for years and I guess Horace Silver and I helped to make it this way. We hated to see these jam groups going on all the time. We had to start out like that, with Clifford Brown and Curly Russell at Birdland. Very luckily, we had a group that clicked together and came off with some good, swinging records.

“The organisation of the group wasn’t there then, but the feel and the swing and the fire was there—and very good musicianship. But this only happens once in a while, so we got afraid of this thing. We sat down and decided we’d better organise. I said to Horace: ‘I’m going to organise my group, so you’d better organise yours’.” One other much–disputed topic brings furrows to Blakey’s brow—the labelling, or possibly mis–labelling, of jazz styles. He describes America as “a gimmick country” when it comes to selling a product. “The tags they put on music to make money don’t make sense. They’ve tagged us a lot of things, such as the Hard Boppers, the Funky Bop or the Funky Music of Art Blakey.

“When we went to Japan this kind of advance publicity had given the people a wrong impression of us.

They thought we were going to be some raggetty guys and that we’d walk off the stage or turn our backs on the audience.

“They’d, got this into their minds and then when we got there they found we were altogether different—and they couldn’t understand this. They said: ‘Why do you look like you do—and perform like you do ? We expected. .’ “You see, these tags and gimmicks can sometimes hurt more than they can help. But they’ll continue to have these gimmicks. Who comes up with these ideas ? I don’t know who it is, but it must be someone who’s not playing music.” No furrows, however, when he speaks of a musician in whom he has a special interest. His son—Art Blakey Junior, aged 21—is also playing drums. Blakey Senior smiles warmly, and admits: “Yes, he’s after it too. I didn’t want him in the business at first, but since he decided to come in I didn’t try to stop him. He’s going after it very hard now and he knows it won’t be easy on account of me being in front. But he’s going to go ahead, anyway.

“He has his ideas about it so I’m going to give him all the help I can. They’re going to expect more out of him than they did out of me—but he made the decision on his own: He came out of school and I thought he would be taking up engineering. But the music struck—and that was it.”

Copyright © 1963 Les Tomkins. All Rights Reserved.

Art Blakey: Interview 2

Interview Two: Speaks his mind Art Blakey talks in depth about his experience drumming and the different styles of drumming there is to offer. Interview: 1973 Source: Jazz Professional

I

wonder if the people will start dancing again, because jazz is very

much a danceable music. I remember when they did, and that was very

nice, too. But people don’t do it any more—and it’s ‘terrible. I think

it’ll come back.

Now, during the Newport Festival this year, they had a Nostalgia Of The ‘Forties night at the Roseland Ballroom, New York, with Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, and a group of singing sisters. That was fantastic—it was sold out, and I was very happy to see that. You know, I think everything should go forward, but I don’t like to see things dropped completely, because they did mean something to many people. The same place was packed also when they had Duke Ellington, Woody Herman and Count Basie there one night. It was a good idea; it brought back many memories.

Sure, the Jazz Messengers have played for dancing.

We play a different type of thing in New York, where they have a Latin group, a West Indian group with the steel drums, and our group. And people dance when we play; most of the time they listen, but they also dance. We did a lot of that; it didn’t go too far outside of New York, but it was fantastic.

The thing was, when this type of music came in, people were ignorant of it. Ignorance breeds fear, and fear breeds hate. They couldn’t understand it; so they didn’t want to listen. If they’d listened, they could dance to it.

And now they’re finding out that they can. As I see it, things go in a cycle. They’ll come round to it. It’s nothing but rhythm.

And rock is bringing it around, too. Some of our best musicians are in the rock field now, and they’re putting out good music.. What the rock drummers are doing is: they’re opening up the things that us jazz drummers are playing three or four times as fast, and playing ‘em slower. And it’s real beautiful, the way they got to this idea. Very clever, too. They started out with rhythm ’n’ blues, and it was called “chopping wood”. Now it’s more rhythm; it’s an opening up of the thing. But they’ll come where we’re at. I figure they all come back to the mother same day! For a musician, this is the most fascinating way to play; it’s the most exciting and everything. I’ve checked out the other ways to play—Dixieland, ragtime, rock, rhythm ’n’ blues, I went all through that. :But this is the way for a drummer to really put it together. He doesn’t have to pound himself to death, and he’s got to play with all musicians, because everybody’s got to know where the beat is.

That’s why they had to have the rock beat—so the people could dance. The drummers had gone so far ahead.

Because once a thing starts out, and you say “One, two, three, four”. it really isn’t necessary for you to keep this up; if you do, you lock yourself in, and you don’t get a chance to explore and advance.

Because this is the thing: we use the European harmonic structure; all my life I’ve been trying to bring that together with the African rhythms. I think we’ll have something very fantastic. And today we’re closer to it than ever. When that comes, it’s not that repetitious thing.

The “one” is there, just as sure as you know the sun is rising or setting, but you’re not supposed to be given credit for that—you just explore. It’s gonna take time, that’s all. The Africans have been dancing to that kind of thing for it’s very nice.

When I went to West Africa, it wasn’t to check out any music, though. I went out there just to learn, you know—to find out what was happening. And at that time over there, I accepted Islam. I just wanted to find out other things about life, like a lot of young people do today—“ Why? What am I here for?” I wasn’t satisfied with what I was taught in school, or by my parents. I felt that they were in a little darkness, too, and I had to go there and find out. I found out. I felt much better about it.

If you find out why, it helps to make the real you. I was able to appreciate more where I came from, the system in which I was raised, what I was doing, and how this thing came about. In other words, I would have gone along in ignorance, hating where I came from. I began to see: no America, no jazz; if I hadn’t been in jazz, I wouldn’t be able to travel and see the world. One thing brought on another, you know. That put my head together.

So I came back, and started playing again. We formed the Seventeen Messengers, but that broke up, because big bands were going out, anyway. No, it hadn’t been my idea. The guys put the band together, just picked me out, and said; “You’re the leader.” I never had any hopes of ever being a bandleader—never thought about it.

But I always had a ‘motor mouth’. I had a way of talking to guys; I could organise, and people liked me for that. I’d had a lot of experience in doing that.

I’d been in other big bands, like Billy Eckstine’s.

There were no combos to be in, other than John Kirby, at that time. I worked with Mary Lou Williams; she brought me to New York for the first time, and we played on 52nd Street for a few weeks. Then I played in some small combos in Pittsburgh. I had my own small combo, playing drums, and I had a big band, playing piano, but I never wanted to get into being a bandleader. Just wanted to make a livelihood. But when the guys picked me, I just went out there, did my best, said what I had to say. Being outgoing helped, I guess.

So, when that didn’t work, Horace Silver, ,Kenny Dorham, Doug Watkins, Hank Mobley and I got together, and Horace suggested that we call this the Jazz Messengers—which was beautiful. Again they made me the leader. It started out as a corporation, but that didn’t last too long. They went and formed their groups, leaving me out there to carry on. That’s how I became mostly a leader since 1955.

I thank God for Horace, Kenny and the guys, too—they gave me a big push forward. ‘‘ Because I wasn’t really doing anything for myself before that.

Thelonious Monk was the guy that was keeping me busy, recording and things, but I didn’t care too much about it; I just took the attitude; “Well, here it is.” They came along and gave me that push.

I don’t think musicians ever said Monk was difficult to play with. I think people were saying that, not musicians. Because musicians are the ones who make musicians. And anybody who knew anything about music knew, revered and feared Monk, as far as music is concerned. It was just that the musicians couldn’t get a chance to play with him. Thelonious was very selective, and I was just fortunate he selected me. He’d take me and Bud Powell around, and he’d stop all the band and let Bud play, and let me play.

Sometimes the musicians would get up and walk off the stand; then Bud and I or Thelonious and I would play by ourselves.

He was very outspoken—and they respected him for it. This man was so fantastic; he knew what he wanted to do, and he did it. He just had that personality, that aura about him. I was so happy to play with him, I tried the best I could; and anyway, I was experimenting. He let you experiment all you wanted, and that was good. I learned a lot with him; that helped to develop me quite a bit, at that time. Because coming out of the big band, I didn’t know that much.

See, playing in a combo and playing in a big band is two different things. In a combo, every tub’s got to sit on its own bottom. I was out there to learn. And when you lead a group, you really got to be into it. As far as I’m concerned, I like to hear big bands, but I don’t want to play with ‘em. I’ve had that. If I had a big band, it would have to be something entirely different rhythmically.

Because I get very angry with musicians loafing, and the rhythm is working. You know, the horns just standing around, looking. I mean, I feel that they should write insurance; everybody’s got to get into the act. There shouldn’t be that laying out a chorus or more, while the band is playing. They should be busy creating something, trying to change the music around, or to move it forward.

But this doesn’t happen. Then you’re carrying a lot of dead weight. See, and the drummer is the stoker; he’s got to pull all this weight.

Some guys, who may be good musicians and able to read, don’t know nothing about rhythm. Thinking about the rhythm—this is what brings out good soloists. That’s what makes Dizzy and what made Charlie Parker great musicians—they’re rhythm experts. Guys like that understand drummers, and they can turn round and explain things. The others figure: “Well, I can blow a horn: I got a sound”, and it’s like you’re pulling a ton of bricks.

They’re going one way, the rhythm’s going another.

Then there are the musicians, if they’ve had a fight with their old lady, they bring it to the bandstand. I don’t allow that in a combo. Whatever you had—I don’t care if your mother just died—you come to the bandstand, that’s it. ‘Cause you don’t know if you’re gonna get back there again. Tomorrow’s not promised to you. If you’re playing music, you’re one of the chosen few, a lucky guy; so, if you get up there—play. If you ain’t gonna play—forget it; this is not your thing.

And that’s what caused the fall of big bands—guys taking it as a job. This is not a job. It’s not a right—it’s a privilege to be able to play music. A privilege from the almighty.

We’re only here for a minute, just little people, small cogs in a big wheel. You’re no big deal; so you get up and do your very best. You play to the people—not down to the people.

If they had done that, this thing would not have failed. But there were so many of ‘em: “I play first trombone”; “I play second trombone”. I learned better than that—Dizzy taught me, when he was musical director of Billy Eckstine’s band. There was no such thing as first trumpet player, first trombone, first alto. You played whatever they passed out. Thelonious would write music; they’d say : “Hey, Monk, how’m I gonna play this, man? How do I get this note up here?” Monk’d say: “It’s on the horn. Find it. Play it.” And this is the way it is.

For big band playing, I think Mel Lewis is doing a tremendous job. He’s one of those personalities that can carry that. I couldn’t; I feel the big band’s got to move in another direction from what it’s moving in today, to come out to be fantastic. Sure, Thad is a genius in the way he writes. If he could be as fortunate as Billy Eckstine was, and he and Mel could get the musicians they want—my God! But Thad is a smart man—he works with the material he has. He certainly hasn’t reached his peak in writing yet, nor as a trumpet and flugelhorn player. He’s just fantastic, and so is Mel. I like their whole thing—the framework of it, all the thoughts behind it. They feel the same; way I do. With what they have, they’re doing a hell of a job.

There’ve been times when I’ve had musicians in the group who hadn’t had a chance to develop. Then people look for me to play a lot of drum solos. But how many drum solos can you play? A drum is not a melody instrument. If you play too much drums, it becomes noise to people; they don’t understand. I like it to be effective, and I do mean to get attention when I play that drum. You know, I don’t try to be technical about it. Technique don’t mean nothing to me; what I want to do is get into the bowels and the guts of the human soul—and I have the instrument to do it with. If you chew your food, you chew it on time; your heart beats on time. When I hit that drum, I get your attention, and try to shake you up inside. Now, I can’t do that all night. You’ve got to have melody instruments, because you’ll get people so disturbed they won’t know what to do with themselves. Many nights I know I’ve upset many people inside; afterwards I’m exhausted.

Well, that’s the way it’s supposed to be. I like to let the people know how I feel, that I feel like they feel.

I ain’t there to get no musicians up off the ground—I’m playing to the people. If the musicians want to come on, they better come on along. If they don’t, I’m just gonna run ‘em off the bandstand. I see how far they can go, how far I can push ‘em, but I don’t try to overplay the soloist. I come to a point, then I’ll slack down and stay behind, because I am an accompaniment—that’s what the rhythm section is for. But I’m not gonna sit back there and keep time for him—he has to play. So you try to develop him in that way. And I don’t want the bass player or the piano player to feel that they have to sit and play time.

He should know time; if he don’t, it’s time he learned. If he doesn’t develop, another musician comes along and takes his place. They’ve all been tremendous, but some of ‘em don’t have time to develop; and sometimes I don’t have time to let them. If things come up that are urgent, then I have to change. And some you get that just won’t—they’re in it for something else, maybe.

I’ve seen the opportunists, who said: “I’m gonna do this, or that”. But I feel they’re very stupid, because if anybody’s gonna do anything, my track record will check ‘em out. I’ll help ‘em, but I don’t want anybody to try to use me as a stepping–stone for their career; if they do that, they’ll fail. The ones that have come through and become leaders are real pure. Horace Silver, Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Benny Golson—these cats are for real.

Some of the others forget that the Jazz Messengers is an institution, and they’re not gonna roll over this thing.

What is so fortunate, the record companies and the agencies are now beginning to see it. My manager, especially, is something else. Jack Whittimore and I have been together for twenty years, and he knows me inside out. He lets nothing pass; if somebody’s kinda weird, or becomes an opportunist, they’re in trouble—all he has to do is pick up the telephone. He just guides my whole thing.

This man and I just go together. He has most of the cats, like Roland Kirk. He’s responsible to a large degree for Miles Davis, I think. Miles had the talent, but I mean the business guidance; he was so sincere about him, because he loved Miles. He loves musicians. You know, he’s been offered fabulous amounts of money under the table, tax free—he looked at them and turned that down, man. That’s a hell of a man. He doesn’t have two faces; he has one face, and he calls a spade a spade. And I like that type of man. It’s a man—and there’s very few of ‘em out here. Lots of males, few men. I hear a lot of people talk about how much man they are, but a tree is known by the fruit it bears. Let’s see what you have done in your life.

I never gotten into that thing of saving money, and buying insurance to bury you with. I’m not worried about that. If you’re able to buy you some land, build a house on it, grow food on it, bury yourself in it when you die—that’s the way I think. ‘The first source of wealth is land.

Because I’ve never seen an armoured car following a hearse, man. So I’m not going to break my neck, taking money off people; I just want to be out here and play, and be at peace. Had I got into this big money thing, it’d have been nice. I don’t know what I would have done. Money changes people—maybe it’d have been the worse far me.

You have to change, if you’re making a lot of money.

You’re not in the same circles; it’s different. You can’t sort out your friends—all that kind of stuff. I don’t want that: I’ve had access to a lot of money in my life; it wasn’t mine. I just want to play some music, make people happy.

Oh, if I had to play that commercial kind of music, I’m telling you—I’d rather go on and be a gambler, make more money shooting crap than doing that. You see, I come out the streets. I know how to do other things and make money. I certainly don’t need to sit down and play in no studio, with no guy waving no stick over my head, that don’t know as much about it as I do. That isn’t what I’m out here for.

I’d love to make a lot of money. I’ve got some definite plans; I’ve got sense enough to know I’m gonna retire sooner or later; nature will take care of that. But I’d like to retire into something, you know. I think the best investment is in another human being. I’d like to have a whole lot of kids, and just have a place for them. Not my kids; I wouldn’t want to sire no kids. No, just get a whole bunch of ‘em—not too many, just enough I could take care of, support and put ‘em out in the country somewhere.

Let ‘em live life, close to nature—not in the city, like where I was raised. If they want to play music, they can, but at least give ‘em a chance. I don’t want to upset the world, or change nothing; I just want my little corner.

But as for the Jazz Messengers—the funny thing is how our music goes in a circle. And since Benny Golson wrote “Blues March” and Bobby Timmons wrote “Moanin’,” we just can’t get away from them. People demand them. Now they’re demanding more of the old things we did. We just recorded “Along Came Betty” with Jon Hendricks; he put some words on it, with the permission of Benny Golson. It was a beautiful thing. There’s such a thing as going too fast for your public; they have to catch up. Boy, that must have been originally recorded fifteen years ago. That’s how the cycle goes.

Time passes so damn fast; I turn around and say: “What happened? Where did it go?” I look up and I see my son standing up there; he’s got a beard and a moustache—damn, he’s a man. He’s a drummer now; he grew up and became our road manager, and travelled with us for years. Oh—there’s so much going on, so many kids.

Horace has a little daughter now, growing up. Donald Byrd’s son is old enough to play. How time went! When it gets home to you, it really shocks you.

I met Chuck Mangione here the other day. Now, when he was a young trumpet player, about eleven years old, his father brought him to the club, and he told me: “I’d sure like to play with the Jazz Messengers.” I said: “Well, son—one day you will.” And what do you know—I turned around and he was a grown man, married, and he joined the band! That thing knocked me out. He had a ball out there with me—something else, ‘cause he never imagined that I would be like I am, when I’m his father’s age. He’d just look at me and shake his head, and say: “Man, you’re something else!” You know, I’ve been around young guys all my life. I mean, I don’t feel any older. It’s only when I look in the mirror and I think about the age that I know. But I act the same way I always did.

And I ain’t got time to look back. You look back—by the time you turn forward somebody’s shot right past you.

You gotta keep getting up, and running as fast as you can.

My present group is not my set group. I just started working regularly again, really, because there came a time when work was hard to get, and we slacked up on everything Horace, all of us. I had cats with me all the time working, enough to exist. But now it’s started picking up, I’m in the throes of really putting it together, and getting guys that’s gonna be in the band for a while, for a couple of years or so, like I used to. I like to set guys together; to get the right combination, you got to set ‘em together spiritually and emotionally. You just can’t take any musician, just because he can play.

It’s got to be a group thing, for us to move forward musically. Then we can move forward financially. But if a guy comes in the group talking about finance, he don’t come here to work. You can forget it. Go play rock, you want to make some money. The only thing we got is: if we stay out here and play, we know we’re going down in history. What’s important is building a good reputation.

I just don’t want to be bothered with those guys who talk about money all the time—they make me sick. Or a fly–by–night promoter or club owner, who wants to make a whole lot of money off of jazz. And they only want to half do it; they don’t want to advertise or anything. If a rock group comes, they take a whole page in a newspaper.

Advertisement is the secret of success. Then, when the jazz makes no money, they tell the lie: “Oh, that jazz is no good.” The truth is that jazz has been selling for years. It surprises me, really, to find that records I made almost a quarter of a century ago, with Monk and all the cats, are still selling. Fantastic. And all the flyby–night rock and rhythm ’n’ blues—I don’t know where they went.

And as for the people who stop using the word jazz—well, they made their reputations playing jazz; so they’re jive. Any of ‘em are jive, who do that. You don’t change horses in mid–stream. I don’t care who they are, or where they are, they’ll never come up to me and tell me that. They may tell some pressman, that they’re trying to make some kind of impression on, but they ain’t gonna say that in front of me. They’re liars, because it’s the only way they got here.

So they’re fortunate, and they get a few write–ups.

That doesn’t mean that you’re great. You made a good record or something, and you’re all pleased about it. I ain’t never made a record I liked—I got that yet to do. People say it’s good, but I don’t think so. I could tear it apart in my own mind when I listen to it; I’m never satisfied with it. So when they get satisfied with themselves, I think it’s very dangerous. They got that. Because there’s always room for improvement.

I don’t understand anybody putting down jazz. And I know a lot of people have done that. I’m sincerely sorry for them. They made a mistake, and they had to come back and eat it up later.

This business of music is hard, with a lot of frustration, too. I’ve made a lot of mistakes, but I’m not going to make the mistake of turning my back on jazz. I love it and appreciate it too much. So many people helped me to come up in this field—Sid Catlett, Gene Krupa, Chick Webb, Max Roach, Kenny Clarke—all the cats, as far back as I can remember. They’re all something to do with my life. Monk, Dizzy, Billie, Charlie Parker—can’t turn my back on them. They made me what I am today, helped me put everything together. I’m staying where I belong.

Copyright © 1973 Les Tomkins. All Rights Reserved.

Now, during the Newport Festival this year, they had a Nostalgia Of The ‘Forties night at the Roseland Ballroom, New York, with Louis Jordan and his Tympany Five, and a group of singing sisters. That was fantastic—it was sold out, and I was very happy to see that. You know, I think everything should go forward, but I don’t like to see things dropped completely, because they did mean something to many people. The same place was packed also when they had Duke Ellington, Woody Herman and Count Basie there one night. It was a good idea; it brought back many memories.

Sure, the Jazz Messengers have played for dancing.

We play a different type of thing in New York, where they have a Latin group, a West Indian group with the steel drums, and our group. And people dance when we play; most of the time they listen, but they also dance. We did a lot of that; it didn’t go too far outside of New York, but it was fantastic.

The thing was, when this type of music came in, people were ignorant of it. Ignorance breeds fear, and fear breeds hate. They couldn’t understand it; so they didn’t want to listen. If they’d listened, they could dance to it.

And now they’re finding out that they can. As I see it, things go in a cycle. They’ll come round to it. It’s nothing but rhythm.

And rock is bringing it around, too. Some of our best musicians are in the rock field now, and they’re putting out good music.. What the rock drummers are doing is: they’re opening up the things that us jazz drummers are playing three or four times as fast, and playing ‘em slower. And it’s real beautiful, the way they got to this idea. Very clever, too. They started out with rhythm ’n’ blues, and it was called “chopping wood”. Now it’s more rhythm; it’s an opening up of the thing. But they’ll come where we’re at. I figure they all come back to the mother same day! For a musician, this is the most fascinating way to play; it’s the most exciting and everything. I’ve checked out the other ways to play—Dixieland, ragtime, rock, rhythm ’n’ blues, I went all through that. :But this is the way for a drummer to really put it together. He doesn’t have to pound himself to death, and he’s got to play with all musicians, because everybody’s got to know where the beat is.

That’s why they had to have the rock beat—so the people could dance. The drummers had gone so far ahead.

Because once a thing starts out, and you say “One, two, three, four”. it really isn’t necessary for you to keep this up; if you do, you lock yourself in, and you don’t get a chance to explore and advance.

Because this is the thing: we use the European harmonic structure; all my life I’ve been trying to bring that together with the African rhythms. I think we’ll have something very fantastic. And today we’re closer to it than ever. When that comes, it’s not that repetitious thing.

The “one” is there, just as sure as you know the sun is rising or setting, but you’re not supposed to be given credit for that—you just explore. It’s gonna take time, that’s all. The Africans have been dancing to that kind of thing for it’s very nice.

When I went to West Africa, it wasn’t to check out any music, though. I went out there just to learn, you know—to find out what was happening. And at that time over there, I accepted Islam. I just wanted to find out other things about life, like a lot of young people do today—“ Why? What am I here for?” I wasn’t satisfied with what I was taught in school, or by my parents. I felt that they were in a little darkness, too, and I had to go there and find out. I found out. I felt much better about it.

If you find out why, it helps to make the real you. I was able to appreciate more where I came from, the system in which I was raised, what I was doing, and how this thing came about. In other words, I would have gone along in ignorance, hating where I came from. I began to see: no America, no jazz; if I hadn’t been in jazz, I wouldn’t be able to travel and see the world. One thing brought on another, you know. That put my head together.

So I came back, and started playing again. We formed the Seventeen Messengers, but that broke up, because big bands were going out, anyway. No, it hadn’t been my idea. The guys put the band together, just picked me out, and said; “You’re the leader.” I never had any hopes of ever being a bandleader—never thought about it.

But I always had a ‘motor mouth’. I had a way of talking to guys; I could organise, and people liked me for that. I’d had a lot of experience in doing that.

I’d been in other big bands, like Billy Eckstine’s.

There were no combos to be in, other than John Kirby, at that time. I worked with Mary Lou Williams; she brought me to New York for the first time, and we played on 52nd Street for a few weeks. Then I played in some small combos in Pittsburgh. I had my own small combo, playing drums, and I had a big band, playing piano, but I never wanted to get into being a bandleader. Just wanted to make a livelihood. But when the guys picked me, I just went out there, did my best, said what I had to say. Being outgoing helped, I guess.

So, when that didn’t work, Horace Silver, ,Kenny Dorham, Doug Watkins, Hank Mobley and I got together, and Horace suggested that we call this the Jazz Messengers—which was beautiful. Again they made me the leader. It started out as a corporation, but that didn’t last too long. They went and formed their groups, leaving me out there to carry on. That’s how I became mostly a leader since 1955.

I thank God for Horace, Kenny and the guys, too—they gave me a big push forward. ‘‘ Because I wasn’t really doing anything for myself before that.

Thelonious Monk was the guy that was keeping me busy, recording and things, but I didn’t care too much about it; I just took the attitude; “Well, here it is.” They came along and gave me that push.

I don’t think musicians ever said Monk was difficult to play with. I think people were saying that, not musicians. Because musicians are the ones who make musicians. And anybody who knew anything about music knew, revered and feared Monk, as far as music is concerned. It was just that the musicians couldn’t get a chance to play with him. Thelonious was very selective, and I was just fortunate he selected me. He’d take me and Bud Powell around, and he’d stop all the band and let Bud play, and let me play.

Sometimes the musicians would get up and walk off the stand; then Bud and I or Thelonious and I would play by ourselves.

He was very outspoken—and they respected him for it. This man was so fantastic; he knew what he wanted to do, and he did it. He just had that personality, that aura about him. I was so happy to play with him, I tried the best I could; and anyway, I was experimenting. He let you experiment all you wanted, and that was good. I learned a lot with him; that helped to develop me quite a bit, at that time. Because coming out of the big band, I didn’t know that much.

See, playing in a combo and playing in a big band is two different things. In a combo, every tub’s got to sit on its own bottom. I was out there to learn. And when you lead a group, you really got to be into it. As far as I’m concerned, I like to hear big bands, but I don’t want to play with ‘em. I’ve had that. If I had a big band, it would have to be something entirely different rhythmically.

Because I get very angry with musicians loafing, and the rhythm is working. You know, the horns just standing around, looking. I mean, I feel that they should write insurance; everybody’s got to get into the act. There shouldn’t be that laying out a chorus or more, while the band is playing. They should be busy creating something, trying to change the music around, or to move it forward.

But this doesn’t happen. Then you’re carrying a lot of dead weight. See, and the drummer is the stoker; he’s got to pull all this weight.

Some guys, who may be good musicians and able to read, don’t know nothing about rhythm. Thinking about the rhythm—this is what brings out good soloists. That’s what makes Dizzy and what made Charlie Parker great musicians—they’re rhythm experts. Guys like that understand drummers, and they can turn round and explain things. The others figure: “Well, I can blow a horn: I got a sound”, and it’s like you’re pulling a ton of bricks.

They’re going one way, the rhythm’s going another.

Then there are the musicians, if they’ve had a fight with their old lady, they bring it to the bandstand. I don’t allow that in a combo. Whatever you had—I don’t care if your mother just died—you come to the bandstand, that’s it. ‘Cause you don’t know if you’re gonna get back there again. Tomorrow’s not promised to you. If you’re playing music, you’re one of the chosen few, a lucky guy; so, if you get up there—play. If you ain’t gonna play—forget it; this is not your thing.

And that’s what caused the fall of big bands—guys taking it as a job. This is not a job. It’s not a right—it’s a privilege to be able to play music. A privilege from the almighty.

We’re only here for a minute, just little people, small cogs in a big wheel. You’re no big deal; so you get up and do your very best. You play to the people—not down to the people.

If they had done that, this thing would not have failed. But there were so many of ‘em: “I play first trombone”; “I play second trombone”. I learned better than that—Dizzy taught me, when he was musical director of Billy Eckstine’s band. There was no such thing as first trumpet player, first trombone, first alto. You played whatever they passed out. Thelonious would write music; they’d say : “Hey, Monk, how’m I gonna play this, man? How do I get this note up here?” Monk’d say: “It’s on the horn. Find it. Play it.” And this is the way it is.

For big band playing, I think Mel Lewis is doing a tremendous job. He’s one of those personalities that can carry that. I couldn’t; I feel the big band’s got to move in another direction from what it’s moving in today, to come out to be fantastic. Sure, Thad is a genius in the way he writes. If he could be as fortunate as Billy Eckstine was, and he and Mel could get the musicians they want—my God! But Thad is a smart man—he works with the material he has. He certainly hasn’t reached his peak in writing yet, nor as a trumpet and flugelhorn player. He’s just fantastic, and so is Mel. I like their whole thing—the framework of it, all the thoughts behind it. They feel the same; way I do. With what they have, they’re doing a hell of a job.

There’ve been times when I’ve had musicians in the group who hadn’t had a chance to develop. Then people look for me to play a lot of drum solos. But how many drum solos can you play? A drum is not a melody instrument. If you play too much drums, it becomes noise to people; they don’t understand. I like it to be effective, and I do mean to get attention when I play that drum. You know, I don’t try to be technical about it. Technique don’t mean nothing to me; what I want to do is get into the bowels and the guts of the human soul—and I have the instrument to do it with. If you chew your food, you chew it on time; your heart beats on time. When I hit that drum, I get your attention, and try to shake you up inside. Now, I can’t do that all night. You’ve got to have melody instruments, because you’ll get people so disturbed they won’t know what to do with themselves. Many nights I know I’ve upset many people inside; afterwards I’m exhausted.

Well, that’s the way it’s supposed to be. I like to let the people know how I feel, that I feel like they feel.

I ain’t there to get no musicians up off the ground—I’m playing to the people. If the musicians want to come on, they better come on along. If they don’t, I’m just gonna run ‘em off the bandstand. I see how far they can go, how far I can push ‘em, but I don’t try to overplay the soloist. I come to a point, then I’ll slack down and stay behind, because I am an accompaniment—that’s what the rhythm section is for. But I’m not gonna sit back there and keep time for him—he has to play. So you try to develop him in that way. And I don’t want the bass player or the piano player to feel that they have to sit and play time.

He should know time; if he don’t, it’s time he learned. If he doesn’t develop, another musician comes along and takes his place. They’ve all been tremendous, but some of ‘em don’t have time to develop; and sometimes I don’t have time to let them. If things come up that are urgent, then I have to change. And some you get that just won’t—they’re in it for something else, maybe.

I’ve seen the opportunists, who said: “I’m gonna do this, or that”. But I feel they’re very stupid, because if anybody’s gonna do anything, my track record will check ‘em out. I’ll help ‘em, but I don’t want anybody to try to use me as a stepping–stone for their career; if they do that, they’ll fail. The ones that have come through and become leaders are real pure. Horace Silver, Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Benny Golson—these cats are for real.

Some of the others forget that the Jazz Messengers is an institution, and they’re not gonna roll over this thing.

What is so fortunate, the record companies and the agencies are now beginning to see it. My manager, especially, is something else. Jack Whittimore and I have been together for twenty years, and he knows me inside out. He lets nothing pass; if somebody’s kinda weird, or becomes an opportunist, they’re in trouble—all he has to do is pick up the telephone. He just guides my whole thing.

This man and I just go together. He has most of the cats, like Roland Kirk. He’s responsible to a large degree for Miles Davis, I think. Miles had the talent, but I mean the business guidance; he was so sincere about him, because he loved Miles. He loves musicians. You know, he’s been offered fabulous amounts of money under the table, tax free—he looked at them and turned that down, man. That’s a hell of a man. He doesn’t have two faces; he has one face, and he calls a spade a spade. And I like that type of man. It’s a man—and there’s very few of ‘em out here. Lots of males, few men. I hear a lot of people talk about how much man they are, but a tree is known by the fruit it bears. Let’s see what you have done in your life.

I never gotten into that thing of saving money, and buying insurance to bury you with. I’m not worried about that. If you’re able to buy you some land, build a house on it, grow food on it, bury yourself in it when you die—that’s the way I think. ‘The first source of wealth is land.

Because I’ve never seen an armoured car following a hearse, man. So I’m not going to break my neck, taking money off people; I just want to be out here and play, and be at peace. Had I got into this big money thing, it’d have been nice. I don’t know what I would have done. Money changes people—maybe it’d have been the worse far me.

You have to change, if you’re making a lot of money.

You’re not in the same circles; it’s different. You can’t sort out your friends—all that kind of stuff. I don’t want that: I’ve had access to a lot of money in my life; it wasn’t mine. I just want to play some music, make people happy.

Oh, if I had to play that commercial kind of music, I’m telling you—I’d rather go on and be a gambler, make more money shooting crap than doing that. You see, I come out the streets. I know how to do other things and make money. I certainly don’t need to sit down and play in no studio, with no guy waving no stick over my head, that don’t know as much about it as I do. That isn’t what I’m out here for.

I’d love to make a lot of money. I’ve got some definite plans; I’ve got sense enough to know I’m gonna retire sooner or later; nature will take care of that. But I’d like to retire into something, you know. I think the best investment is in another human being. I’d like to have a whole lot of kids, and just have a place for them. Not my kids; I wouldn’t want to sire no kids. No, just get a whole bunch of ‘em—not too many, just enough I could take care of, support and put ‘em out in the country somewhere.

Let ‘em live life, close to nature—not in the city, like where I was raised. If they want to play music, they can, but at least give ‘em a chance. I don’t want to upset the world, or change nothing; I just want my little corner.

But as for the Jazz Messengers—the funny thing is how our music goes in a circle. And since Benny Golson wrote “Blues March” and Bobby Timmons wrote “Moanin’,” we just can’t get away from them. People demand them. Now they’re demanding more of the old things we did. We just recorded “Along Came Betty” with Jon Hendricks; he put some words on it, with the permission of Benny Golson. It was a beautiful thing. There’s such a thing as going too fast for your public; they have to catch up. Boy, that must have been originally recorded fifteen years ago. That’s how the cycle goes.

Time passes so damn fast; I turn around and say: “What happened? Where did it go?” I look up and I see my son standing up there; he’s got a beard and a moustache—damn, he’s a man. He’s a drummer now; he grew up and became our road manager, and travelled with us for years. Oh—there’s so much going on, so many kids.

Horace has a little daughter now, growing up. Donald Byrd’s son is old enough to play. How time went! When it gets home to you, it really shocks you.

I met Chuck Mangione here the other day. Now, when he was a young trumpet player, about eleven years old, his father brought him to the club, and he told me: “I’d sure like to play with the Jazz Messengers.” I said: “Well, son—one day you will.” And what do you know—I turned around and he was a grown man, married, and he joined the band! That thing knocked me out. He had a ball out there with me—something else, ‘cause he never imagined that I would be like I am, when I’m his father’s age. He’d just look at me and shake his head, and say: “Man, you’re something else!” You know, I’ve been around young guys all my life. I mean, I don’t feel any older. It’s only when I look in the mirror and I think about the age that I know. But I act the same way I always did.

And I ain’t got time to look back. You look back—by the time you turn forward somebody’s shot right past you.

You gotta keep getting up, and running as fast as you can.

My present group is not my set group. I just started working regularly again, really, because there came a time when work was hard to get, and we slacked up on everything Horace, all of us. I had cats with me all the time working, enough to exist. But now it’s started picking up, I’m in the throes of really putting it together, and getting guys that’s gonna be in the band for a while, for a couple of years or so, like I used to. I like to set guys together; to get the right combination, you got to set ‘em together spiritually and emotionally. You just can’t take any musician, just because he can play.

It’s got to be a group thing, for us to move forward musically. Then we can move forward financially. But if a guy comes in the group talking about finance, he don’t come here to work. You can forget it. Go play rock, you want to make some money. The only thing we got is: if we stay out here and play, we know we’re going down in history. What’s important is building a good reputation.

I just don’t want to be bothered with those guys who talk about money all the time—they make me sick. Or a fly–by–night promoter or club owner, who wants to make a whole lot of money off of jazz. And they only want to half do it; they don’t want to advertise or anything. If a rock group comes, they take a whole page in a newspaper.

Advertisement is the secret of success. Then, when the jazz makes no money, they tell the lie: “Oh, that jazz is no good.” The truth is that jazz has been selling for years. It surprises me, really, to find that records I made almost a quarter of a century ago, with Monk and all the cats, are still selling. Fantastic. And all the flyby–night rock and rhythm ’n’ blues—I don’t know where they went.

And as for the people who stop using the word jazz—well, they made their reputations playing jazz; so they’re jive. Any of ‘em are jive, who do that. You don’t change horses in mid–stream. I don’t care who they are, or where they are, they’ll never come up to me and tell me that. They may tell some pressman, that they’re trying to make some kind of impression on, but they ain’t gonna say that in front of me. They’re liars, because it’s the only way they got here.

So they’re fortunate, and they get a few write–ups.

That doesn’t mean that you’re great. You made a good record or something, and you’re all pleased about it. I ain’t never made a record I liked—I got that yet to do. People say it’s good, but I don’t think so. I could tear it apart in my own mind when I listen to it; I’m never satisfied with it. So when they get satisfied with themselves, I think it’s very dangerous. They got that. Because there’s always room for improvement.

I don’t understand anybody putting down jazz. And I know a lot of people have done that. I’m sincerely sorry for them. They made a mistake, and they had to come back and eat it up later.