SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2016

VOLUME THREE NUMBER ONE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

SUMMER, 2016

VOLUME THREE NUMBER ONE

MARY LOU WILLIAMS

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

JULIUS HEMPHILL

June 18-24

ARTHUR BLYTHE

June 25-July 1

OSCAR BROWN, JR.

July 2-July 8

DONNIE HATHAWAY

July 9-July 15

EUGENE McDANIELS

July 16-July 22

ROBERTA FLACK

July 23-July 29

WOODY SHAW

July 30-August 5

FATS DOMINO

August 6-August 12

CLIFFORD BROWN

August 13-August 19

BLIND WILLIE McTELL

August 20-August 26

RAHSAAN ROLAND KIRK

August 27-September 2

CHARLES BROWN

September 3-September 9

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/arthur-blythe-mn0000507583/biography

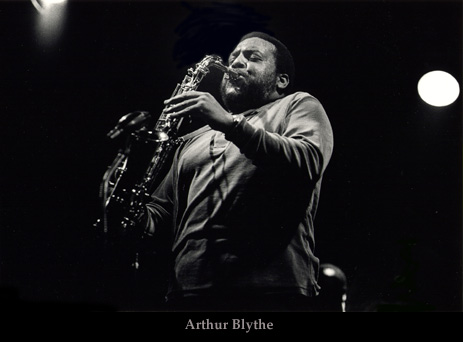

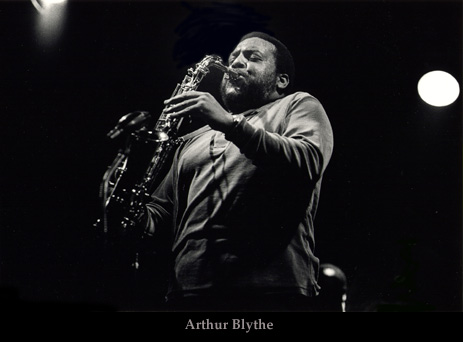

ARTHUR BLYTHE

(b. July 5, 1940)

Artist Biography

After moving to New York, Blythe worked and recorded as a sideman with Chico Hamilton (1974-1977) and Gil Evans (1976-1980). He first recorded as a leader in 1977. He was no young lion; Blythe was 37 years old when his first records, The Grip and Metamorphosis, were released on the independent India Navigation label. By then, Blythe was a fully developed, mature artist, a free-influenced player who was also capable of playing older styles in an utterly personal and borderline iconoclastic way. When Blythe played a standard, he imbued it with all that had happened in jazz since it was written, up to and including the free techniques that were integral to his concept; one can hear traces of his predecessors, but as an affectionate remembrance, not an affectation. Blythe's style varied mostly in the form of his contexts. His earliest recordings feature unusual instrumentation; 1977's Bush Baby featured the saxophonist in a transmogrified version of the sax-bass-drums trio, with Bob Stewart on tuba and Muhammed Abdullah on conga. During his Columbia days, Blythe maintained two separate but equal performing units. One was the so-called "electric band," a free funk-oriented quintet with Stewart, cellist Abdul Wadud, drummer Bobby Battle, and, at various times, electric guitarists James "Blood" Ulmer and Kelvyn Bell. The other was an acoustic jazz quartet that took its name from its first Columbia release: 1979's In the Tradition. The band included bassist Fred Hopkins, drummer Steve McCall, and pianist Stanley Cowell. That album gained Blythe a great deal of critical and popular attention. In retrospect, In the Tradition can be seen as a forerunner to the hard bop revival that dominated major-label jazz in the '80s and into the late '90s -- a development that ultimately consigned progressive jazzers like Blythe to the margins. Blythe made several records for Columbia of varying quality. Lennox Avenue Breakdown and Illusions were very strong; others were not. By 1984's Put Sunshine in It -- a disturbingly inane (and perhaps last-ditch) effort at grabbing a portion of the expanding jazz fusion market -- Blythe's welcome at Columbia had just about worn out. He did rebound a bit with 1987's Basic Blythe, an In the Tradition-type album that was unnecessarily cluttered by a string section. The record was his last for Columbia.

Blythe recorded less frequently in the late '80s and '90s. He and David Murray comprised a state-of-the-art sax section on one of the most highly praised albums of the '80s, Jack DeJohnette's Special Edition. Blythe also joined Lester Bowie, Chico Freeman, Don Moye, Kirk Lightsey, and Cecil McBee in a band rather presumptuously called the Leaders, which recorded a pair of well-received albums for Black Hawk and Black Saint. Blythe briefly replaced Julius Hemphill in the World Saxophone Quartet in 1990. He recorded for Enja in the '90s; 1991's Hipmotism featured a revamped version of his "electric" group; 1993's Retroflection was an acoustic effort. In 2002, Blythe enlisted marimba player William Tsillis, tuba player Bob Stewart, and drummer Cecil Brooks III, releasing Focus on Savant.

JULIUS HEMPHILL

June 18-24

ARTHUR BLYTHE

June 25-July 1

OSCAR BROWN, JR.

July 2-July 8

DONNIE HATHAWAY

July 9-July 15

EUGENE McDANIELS

July 16-July 22

ROBERTA FLACK

July 23-July 29

WOODY SHAW

July 30-August 5

FATS DOMINO

August 6-August 12

CLIFFORD BROWN

August 13-August 19

BLIND WILLIE McTELL

August 20-August 26

RAHSAAN ROLAND KIRK

August 27-September 2

CHARLES BROWN

September 3-September 9

LIGHT BLUE: Arthur Blythe Plays The Music of Thelonious Monk

Columbia, 1983

Music Review by Kofi Natambu

Solid Ground: A New World Journal

Fall, 1983

With this recording, Arthur Blythe, a very fine alto saxophonist and composer who has consistently made good records, enters the realm of greatness. In fact, what makes Blythe’s original interpretations of classic compositions by the late master Thelonious Sphere Monk so distinctive is his highly perceptive understanding of how the Afro-American tradition in music continues to affect the present. it is this appreciation for the fundamental roots in Blythe’s experience that allows him to use this extensive background in his current conception. A little historical information on Blythe will clearly reveal why this is so.

Born in 1940 in San Diego, California, Arthur Blythe spent the early part of his life being exposed to a very broad range of Black music, and music from other cultures, especially Latin-American musics. Rhythm and Blues, Blues, Spirituals and creative improvisation were all a part of his daily staple. Thus it was in high school, at the relatively “late” age of 16 that Blythe seriously began playing the alto saxophone. Influenced initially by the soft melodic playing of Paul Desmond, Blythe soon became aware of the hard-edged “funky” sound of Julius “Cannonball” Adderley, who during the mid and late 1950s was acquiring legendary status playing with the likes of Miles Davis and John Coltrane. It was the blues-drenched post-bop lyricism of Adderley that made Arthur want to pursue music seriously. Soon young Arthur was voraciously collecting records by the masters in the post WWII tradition—Sonny Rollins, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, and of course the towering musical figure of his generation, the extraordinary Charles “Bird” Parker.

It was Bird who really sent Arthur flying. After hearing him in high school, Blythe knew that music would be his life. An intense period of study, discipline and creative work began upon Blythe’s graduation from high school. During the early 1960s Blythe began playing with the legendary pianist-composer and educator Horace Tapscott in Los Angeles. Tapscott was (and is) largely considered the “Sun Ra of the West Coast” because of his seminal educational and creative impact on the young black music community of L.A. (namely the area known as Watts) during the politically and culturally volatile 1960s. As a result of these struggles, Tapscott founded an artistic collective called the Underground Musicians’ Association in 1964 that was really one of the first major black artists’ collectives that flourished nationally during the 1960s. In this respect, the U.G.M.A. can be considered an historical predecessor of such groups as the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and the Black Artists Group (BAG).

Arthur’s active involvement in the community-oriented cultural and political activities of the U.G.M.A. and other groups led him to acquiring the name of “Black” Arthur Blythe. This was because of Blythe’s intense interest in all aspects of Black history (a concern that still motivates Blythe’s conception). Black Arthur played in hundreds of workshops, concerts, benefits, and multi-media productions during the decade he was a part of the U.G.M.A., working very closely with Tapscott’s orchestra and his many small ensembles. During this time Blythe began to reveal his considerable compositional abilities and also lead some of his own groups around L.A. and the San Francisco Bay area. It was during this time in the late 1960s that Blythe began to receive a significant “underground” reputation throughout the rest of the U.S. and in Europe. This was before he had appeared on any records anywhere. I remember hearing about Black Arthur for the first time in late 1969 when some friends told me about a growling bear of a saxophonist who was as good or better than anyone else on the scene. These friends had heard him in L.A. and were convinced that he was going to be the next “big thing” in black creative music. This was still before any recorded evidence, mind you.

However, in the spring of 1970 as recording appeared on the Flying Dutchman label entitled The Giant Is Awakened that featured Black Arthur with the Horace Tapscott Quintet. Here at the still creatively formative age of thirty were the full-blown talents of Blythe exposed for all the world to heat What we heard was a mature virtuoso with a gigantic tone, and a very wide technical range on alto that could play high harmonics and gut-level vibrato with ease. Here was a saxophonist who had obviously absorbed the pyro-technics of the be-bop tradition but had also paid very close attention to such masters of the idiom known as Benny Carter and Johnny Hodges. In fact, Blythe had the same rich, sensuousness and captivating melodic grace that made Carter, Hodges and Lester Young (to name a few) so warm and compelling. At the same time Blythe could play scorching up-tempo blasters that left even seasoned Bird-watchers gasping. On top of all this, Blythe was an original and thought-provoking composer whose works used the lessons taught by Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and in a later context, Thelonious Sphere Monk. Clearly, Black Arthur had arrived. The fact that he was economically destitute only increased the irony of his exalted status among musicians.

II. Black Arthur Goes East (So He Can Pay the Rent)

The next phase of the Blythe saga begins in New York City in 1972 when Arthur decided to try to make a living in the vicious, competitive environment of NYC, a city world famous for both “making” and breaking(!) creative artists. In this amphetamine culture Arthur experienced what hundreds of black musicians go through every year in the rotten apple, and that is crushing rejection and isolation caused by the gangster-controlled economics of the nightclub and recording industry. After close to a year of near-starvation in the neon jungle Arthur decided that his timing was off and returned to the West Coast. However, during this period he makes a hookup with the famous drummer Chico Hamilton (who was now semi-retired working on Madison Avenue as an agent). in late 1973 Hamilton returned to active playing and Blythe was recruited in the band as lead soloist. A series of recordings by Hamilton beginning in 1974 again brings Blythe to the forefront as a major force to be reckoned with. Hamilton helps along both popular and critical support for Blythe’s efforts by announcing that “Blythe is the finest saxophonist and composer I have played with since the late Eric Dolphy.” Very high praise indeed but by now (1975) Blythe definitely deserved it.

After a very active and fruitful two year period with Hamilton, Blythe plunged headlong into the extremely creative but largely underground network of lofts and makeshift “clubs” (often people’s homes) that became the scene for young (and older) black creative musicians in the mid and late 1970s. In the absence of any real interest or support among conventional club owners or concert promoters, black musicians banded together to ensure their collective survival. In this atmosphere of relaxed and congenial unity and self-determination, Blythe’s music really began to flourish and a series of outstanding recordings on small, obscure labels were the result. These records for labels like the then-new India Navigation and Adelphi companies soon became cherished collector’s items, which they remain today. In fact, records like The Grip, Bush Baby and Lenox Avenue Breakdown (which was Blythe’s first record for the conglomerate known as Columbia and introduced Blythe to a much wider audience) are viewed as the actual beginning of Arthur’s artistic influence on other musicians of this period.

Since his public debut with Columbia in 1978, Blythe has gone on to record such fine performances as In the Tradition, Illusions, Blythe Spirit and Elaborations, which can be construed as state-of-the-art “mainstream modernism.” While all of these records feature brilliant playing and composing by Blythe and his long-time cohorts Bob Stewart (tuba), Abdul Wadud (cello), Bobby Battle (drums) and Kelvyn Bell (guitar), they don’t quite reach the absolutely stunning quality of this ensemble’s latest and most complete effort: Arthur Blythe Plays the Music of Thelonious Monk. It is this breath-taking synthesis of all of Blythe’s myriad musical experiences that distinguishes this almost perfect homage to the spirit of Monk’s amazing creations and puts Blythe and his ensemble in the upper echelons of Black creative bands over the past 20 years.

III. Blythe Meets Monk (And the Rest Is History...)

The important thing to remember about Monk’s music, like the music and art of all “great masters,” is that the forms used are deceptive. That is, one can never be too sure where these structures will lead. In the world of improvisational music where group communication is essential the greatest composers establish melodic, harmonic and rhythmic patterns that are a challenge to the players involved. In the singularly innovative world of T. Monk this means that the improviser can never rely simply on horizontal (melodic) or vertical (chordal-harmonic) material as a sole basis of musical expression. Rather it is the dynamic cross-rhythms and internal structure of the melodic lines in contrast to the relative independence of the harmonies that set up polyphonic dialogue between players in an ensemble and ensures textural and timbral variety in the course of a composition’s life. These elements thus create a kind of polytonal antiphony that would allow movement and transmutation of melody and rhythm in both time and space. This command of mathematical principles and emotional values in music is the trademark of Monk’s art and the very basis of his majestic legacy. It is Blythe’s scientific and intuitive knowledge of these factors that make his own extrapolations on this inheritance so profound.

First Monk’s music is devoid of clichés. That is the music never falls into predictable structural patterns based on stylistic devices. While Monk was obviously an integral part of the so-called “be-bop” movement among black musicians in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and even on some crucial levels a major architect of its aesthetic, he never allowed his own conception to merely ape or facilely reproduce the elements that went into the development of the style. This attitude of finding a functional and creative purpose for artistic expression is what gives Monk’s compositions their characteristic vitality and sense of conceptual unity. Monk is constantly synthesizing, extending and recasting traditional ideas and values in Afro-American creative music and thus redefining them in his own vision of composition and improvisation. That this is the inherent (and difficult) challenge of Black music as an expressive art almost goes without saying. However, because Monk so mastered the philosophical and cultural values of the art he was able to make the music even more adaptable to change and growth than it had always been (which is saying a great deal after the extraordinary innovations in form and feeling laid down by people like Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Charlie “Yardbird” Parker). It is this aspect of Monk’s contribution that Blythe uses in his own extensions and synthetic conception.

Secondly, Monk relies almost exclusively on those independent and distinctive principles developed in the African-American tradition. His entire concept of melodic expression is based on highly original variations on thematic material. These variations are almost invariablyrhythmic and “textural.” Monk’s work, despite the fact that he plays the strictly diatonic instrument known as the piano, is based on the ingenious use of sound combinations voiced percussively. There are wild clusters of notes that are sounded to support a piece’s movement and shape rather than the standard harmonic idea of background landscape for linear progressions. By remaining true to the uniquely Afro-American ideas about displaced accents, shifting meters, shaded delays and subtle anticipations (in music the effective use of space, rest and silence), Monk avoids the neo-classical and Debussyan sentimentalities of many other modern pianist-composers in black music. This creative reliance on the blues as both “technical” and inspirational material allows Monk to improvise orchestrations(!) through the structural and emotional continuity of melody and “harmony.” In order to play Monk’s pieces well one must know how the melody and the harmony fit together and also understand why. Most of Monk’s melodies are so strong and important that his bass lines are integrated into the very structure of the piece. This makes it almost impossible for a soloist to merely coast by improvising on Monk’s chord structures alone. A player would have to use the theme and its rhythms (both stated and implied) in order to musically communicate anything at all. This is why Monk’s music is considered difficult for many musicians. A player would have to be thinking and alert all the time or as the late, great John Coltrane once stated, one would feel as if “he had fallen down an elevator shaft.”Blythe understands this crucial detail about Monk’s music and thus avoids the musical traps and dilemmas that plague so many people when they try to play Monk’s music. Because Blythe, like Monk, never tries to “fake” his knowledge of anything he is able to use that which is essential to his own purposes and implicitly comment on the rest

As other critics have pointed out, the core of Monk’s style is rhythmic virtuosity. Monk recognizes that the inherent balance in creative music is based on the intrinsic unity of harmony, rhythm and melodic line. Innovations in one area would have to be supported by further innovations in the other areas. Since rhythm is fundamental to black music, any innovation in its uses would have to be accompanied by parallel changes in harmonic construction and linear expression. By revoicing or inventing new chordal material, by displacing and shifting or breaking up the rhythms (in terms of tempo and accents) and byconstantly reworking and extending basic thematic phrases and ideas (often within the contours of the melodic frame itself), Monk was able to develop his own way of organizing and expressing the small group ensemble. This too is a significant lesson that Blythe has learned well in his own explorations of music.

Finally, in Blythe’s thorough reappraisal and use of Monk’s methods he has forged his own pathway in the contemporary idiom. For example, the subtly forceful and discursive interplay of the tuba and cello in Blythe’s group eliminates the need for the chordal restrictions of conventional bass and piano. Thus more rhythmic diversity is assured within the anchoring context of alto saxophone and drums. Meanwhile, the guitar is free to float in between or in sympathetic support of the frontline (which, depending on Blythe’s striking arrangements can be the saxophone and cello, the cello and tuba, or even the saxophone and tuba). Polyrhythmic conversations and contrapuntal exchanges are a consistent motif in what are, in effect, improvisatory orchestrations stated by the entire band(!). That Blythe would be confident and daring enough to use salsa rhythms as well as traditional blues elements and R&B dynamics indicates that he recognizes that Monk’s music is adaptable to any “stylistic” form. Thus as the musicologist Yousef Yancy points out in his erudite liner notes to this recording: “the compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk are... universal expressions of music... that are useful for symphonies, duos, trios, big bands, quartets, piano-less quintets, chamber music and for the soloist, (it offers) infinite possibilities for musical exploration--a meaningful and fulfilling achievement for any composer...”

This is precisely what Blythe reveals in this recording of six Monk originals. The risk-taking virtuosity and empathetic unity of Blythe’s quintet means that we should all pay close attention to this band. The future is NOW.

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/arthur-blythe-mn0000507583/biography

ARTHUR BLYTHE

(b. July 5, 1940)

Artist Biography

by Chris Kelsey

For a time in the late '70s and early '80s, it

seemed as if jazz's avant-garde was on the verge of a popular

breakthrough in the person and music of Arthur Blythe. Blythe was signed by Columbia Records; the label's hype-heavy promotion of the saxophonist almost made him a star. It didn't work; Blythe

was too "out" for the masses. Columbia realized that it had made a

mistake by expecting too much of the public, and threw its promotional

weight behind a more malleable, less threatening young prince by the

name of Wynton Marsalis. And the rest is history.

Arthur Blythe

grew up in San Diego. He began playing music in school bands at the age

of nine. In his teens he studied with a former member of Jimmie Lunceford's sax section, Kirtland Bradford. After moving to Los Angeles in 1960, he began playing with pianist/bandleader Horace Tapscott. In 1961, the two became founding members of the Union of God's Musicians and Artist's Ascension. Blythe recorded under Tapscott's leadership in 1969 and worked regularly with the pianist until 1974.

After moving to New York, Blythe worked and recorded as a sideman with Chico Hamilton (1974-1977) and Gil Evans (1976-1980). He first recorded as a leader in 1977. He was no young lion; Blythe was 37 years old when his first records, The Grip and Metamorphosis, were released on the independent India Navigation label. By then, Blythe was a fully developed, mature artist, a free-influenced player who was also capable of playing older styles in an utterly personal and borderline iconoclastic way. When Blythe played a standard, he imbued it with all that had happened in jazz since it was written, up to and including the free techniques that were integral to his concept; one can hear traces of his predecessors, but as an affectionate remembrance, not an affectation. Blythe's style varied mostly in the form of his contexts. His earliest recordings feature unusual instrumentation; 1977's Bush Baby featured the saxophonist in a transmogrified version of the sax-bass-drums trio, with Bob Stewart on tuba and Muhammed Abdullah on conga. During his Columbia days, Blythe maintained two separate but equal performing units. One was the so-called "electric band," a free funk-oriented quintet with Stewart, cellist Abdul Wadud, drummer Bobby Battle, and, at various times, electric guitarists James "Blood" Ulmer and Kelvyn Bell. The other was an acoustic jazz quartet that took its name from its first Columbia release: 1979's In the Tradition. The band included bassist Fred Hopkins, drummer Steve McCall, and pianist Stanley Cowell. That album gained Blythe a great deal of critical and popular attention. In retrospect, In the Tradition can be seen as a forerunner to the hard bop revival that dominated major-label jazz in the '80s and into the late '90s -- a development that ultimately consigned progressive jazzers like Blythe to the margins. Blythe made several records for Columbia of varying quality. Lennox Avenue Breakdown and Illusions were very strong; others were not. By 1984's Put Sunshine in It -- a disturbingly inane (and perhaps last-ditch) effort at grabbing a portion of the expanding jazz fusion market -- Blythe's welcome at Columbia had just about worn out. He did rebound a bit with 1987's Basic Blythe, an In the Tradition-type album that was unnecessarily cluttered by a string section. The record was his last for Columbia.

Blythe recorded less frequently in the late '80s and '90s. He and David Murray comprised a state-of-the-art sax section on one of the most highly praised albums of the '80s, Jack DeJohnette's Special Edition. Blythe also joined Lester Bowie, Chico Freeman, Don Moye, Kirk Lightsey, and Cecil McBee in a band rather presumptuously called the Leaders, which recorded a pair of well-received albums for Black Hawk and Black Saint. Blythe briefly replaced Julius Hemphill in the World Saxophone Quartet in 1990. He recorded for Enja in the '90s; 1991's Hipmotism featured a revamped version of his "electric" group; 1993's Retroflection was an acoustic effort. In 2002, Blythe enlisted marimba player William Tsillis, tuba player Bob Stewart, and drummer Cecil Brooks III, releasing Focus on Savant.

Blythe

possesses one of the most easily recognizable alto sax sounds in jazz,

big and round, with a fast, wide vibrato and an aggressive, precise

manner of phrasing. His lines are frequently quite Baroque and always

well-defined; his playing has been criticized (unfairly, some would say)

as being overly ornamental, but he is certainly capable of improvising

melodies of great character and originality.

Arthur Blythe

A singularly distinctive and uniquely distinguishable stylist, Arthur Blythe is considered one of the greatest alto saxophonist's of his generation. Blythe's beautiful, passionate and expressive sound validates his reputation as one of the most significant jazz musicians of our times. Blythe's work is notable for its exploration of harmony, group counterpoint, and unusual instrumentation. These features, coupled with his rapid, wide vibrato, his swinging style, and his interest in the standard jazz repertory, have won him praise from a wide audience.

Arthur Blythe was born 1940 in Los Angeles and grew up in San Diego where his parents moved 1944. He still performs the same alto saxophone that he and his mother bought 1957 in a second-hand store. Arthur began his career on the alto at nine years old and by 13 was playing in an R&B band. Moving back to LA in the late 50's, Blythe became a leading member of a lively and creative avant-garde jazz scene.

Arthur started working with the inimitable pianist-composer Horace Tapscott with whom he made his first recording in 1969, on Tapscott's “The Giant is Awakening.”

Blythe settled in New York City in 1974 and has since built a stellar career while performing in a variety of jazz-oriented, world music environments. His aesthetic vision is broad enough to embrace that which is traditional, the modernist and the experimental impulse in contemporary jazz. Developing his baroque style at the instrument in the combos of Chico Hamilton, (75-77) Gil Evans, (76-78) Lester Bowie, (‘78), Jack DeJohnette, (‘79) and McCoy Tyner. (‘79)

Various Arthur Blythe ensembles have included African drums, Turkish Percussion, Violins, violas, electric guitar and tubs, in addition to piano, contrabass and drums. His individualistic instrumental blends are acknowledged for their recognizable, yet personal, musical statements.

Arthur's discography, as a leader or guest artist, extends to over 50 albums and includes ten seminal CBS Record albums, recordings with the Roots Band, The Leaders and The World Saxophone Quartet he made during the 80's. One of the last jazzers to receive the start treatment at Columbia records, altoist Arthur Blythe made a series of fine records that covered the distance between his loft jazz roots and the pop tastes of the time. “Lenox Avenue Breakdown”(’79) combined Blythe's singularly soulful delivery with a mix that seems more suited to now than then. Blythe wasted no time in recruiting a dream team of drummer Jack DeJohnette, tuba player Bob stewart, and bassist Cecil McBee on the bottom, joined by guitarist James Blood Ulmer in the middle, and flutist James Newton on top, plus percussionist Guillermo Franco to add an appropriately Spanish tinge now and again. This group plays like a band that had been together for years, not the weeklong period it took them to rehearse and create one of Blythe's masterpieces. Close to thirty years later, “Lenox Avenue Breakdown” still sounds new and different and ranks among the three finest albums in his catalog.

Blythe recorded less frequently in the late '80s and '90s. He and David Murray comprised the sax section on, Jack DeJohnette's “Special Edition.” Blythe also joined Lester Bowie, Chico Freeman, Don Moye, Kirk Lightsey, and Cecil McBee in a band called the Leaders, which recorded a pair of albums for Black Hawk and Black Saint. Blythe briefly replaced Julius Hemphill in the World Saxophone Quartet in 1990. He recorded for Enja as with “Hipmotism” (’91) featuring a revamped version of his “electric” group. “Retroflection,” (’93) was an acoustic effort. In 2002, Blythe enlisted marimba player William Tsillis, tuba player Bob Stewart, and drummer Cecil Brooks III, releasing “Focus,” on Savant.

There is an excellent interview by Fred Jung here @ all about jazz, and in Arthur’s words; “I am not just avant- garde. I like to play all types of music as much as I can play, straight-ahead or whatever they call that. I like rhythm and blues. I like music with form, not atonal or aform. I am not only there. Sometimes they put me into a weird bag and want me to be weird, inaccessible. I think I am accessible.”

Source: James Nadal

Arthur Blythe was born 1940 in Los Angeles and grew up in San Diego where his parents moved 1944. He still performs the same alto saxophone that he and his mother bought 1957 in a second-hand store. Arthur began his career on the alto at nine years old and by 13 was playing in an R&B band. Moving back to LA in the late 50's, Blythe became a leading member of a lively and creative avant-garde jazz scene.

Arthur started working with the inimitable pianist-composer Horace Tapscott with whom he made his first recording in 1969, on Tapscott's “The Giant is Awakening.”

Blythe settled in New York City in 1974 and has since built a stellar career while performing in a variety of jazz-oriented, world music environments. His aesthetic vision is broad enough to embrace that which is traditional, the modernist and the experimental impulse in contemporary jazz. Developing his baroque style at the instrument in the combos of Chico Hamilton, (75-77) Gil Evans, (76-78) Lester Bowie, (‘78), Jack DeJohnette, (‘79) and McCoy Tyner. (‘79)

Various Arthur Blythe ensembles have included African drums, Turkish Percussion, Violins, violas, electric guitar and tubs, in addition to piano, contrabass and drums. His individualistic instrumental blends are acknowledged for their recognizable, yet personal, musical statements.

Arthur's discography, as a leader or guest artist, extends to over 50 albums and includes ten seminal CBS Record albums, recordings with the Roots Band, The Leaders and The World Saxophone Quartet he made during the 80's. One of the last jazzers to receive the start treatment at Columbia records, altoist Arthur Blythe made a series of fine records that covered the distance between his loft jazz roots and the pop tastes of the time. “Lenox Avenue Breakdown”(’79) combined Blythe's singularly soulful delivery with a mix that seems more suited to now than then. Blythe wasted no time in recruiting a dream team of drummer Jack DeJohnette, tuba player Bob stewart, and bassist Cecil McBee on the bottom, joined by guitarist James Blood Ulmer in the middle, and flutist James Newton on top, plus percussionist Guillermo Franco to add an appropriately Spanish tinge now and again. This group plays like a band that had been together for years, not the weeklong period it took them to rehearse and create one of Blythe's masterpieces. Close to thirty years later, “Lenox Avenue Breakdown” still sounds new and different and ranks among the three finest albums in his catalog.

Blythe recorded less frequently in the late '80s and '90s. He and David Murray comprised the sax section on, Jack DeJohnette's “Special Edition.” Blythe also joined Lester Bowie, Chico Freeman, Don Moye, Kirk Lightsey, and Cecil McBee in a band called the Leaders, which recorded a pair of albums for Black Hawk and Black Saint. Blythe briefly replaced Julius Hemphill in the World Saxophone Quartet in 1990. He recorded for Enja as with “Hipmotism” (’91) featuring a revamped version of his “electric” group. “Retroflection,” (’93) was an acoustic effort. In 2002, Blythe enlisted marimba player William Tsillis, tuba player Bob Stewart, and drummer Cecil Brooks III, releasing “Focus,” on Savant.

There is an excellent interview by Fred Jung here @ all about jazz, and in Arthur’s words; “I am not just avant- garde. I like to play all types of music as much as I can play, straight-ahead or whatever they call that. I like rhythm and blues. I like music with form, not atonal or aform. I am not only there. Sometimes they put me into a weird bag and want me to be weird, inaccessible. I think I am accessible.”

Source: James Nadal

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/a-fireside-chat-with-arthur-blythe-arthur-blythe-by-aaj-staff.php

Growing up during the early 1960s people of my generation was soaking up a lot of “STUFF” politically, socially,economically and musically… some of the big guns that were speaking to the progressive Black youth were the artists of the so-called Avant Garde movement like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor and by the Late 60s, Black Arthur.. Arthur Blythe was spitting phrases on his alto like an Amiri Baraka poem.. hitting you in the gut with truth and spiritual bliss. His signature bluesy, buttery-vibrato laden tone. Unique band instrumentation was his calling card incorporating a tuba as a lead and comping instrument was not unusual for Blythe. The last time I saw him live was early 2004 at Yoshi’s Jazz house in Oakland California. He has been ill for a while now , including a serious daily battle with Parkinson’s Disease. He can no longer play or fend for himself on some days.. a “Help Arthur Fund” was set up over a year ago, and YOU CAN HELP with any amount of Donation. Just today, I spoke with one of his main caretakers, Mr. Gust Tsilis, longtime friend and fellow band member. yesterday, May 7 was Arthur’s 74th birthday. For more info on how to help with donations, please call (323) 251-0688

Composer

and vibraphonist/marimba player Gust Tsilis, who appeared on several

discs with Blythe in the 1990s, hosts the fund’s webpage on his website.

The funding is collecting donations via credit cards and PayPal. Help with donations, please call (323) 251-0688

THE MUSIC OF ARTHUR BLYTHE: AN EXTENSIVE VIDEO OVERVIEW, A CROSS SECTION OF RECORDINGS, MUSICAL ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY, PLUS VARIOUS INTERVIEWS WITH MR. BLYTHE:

Arthur Blythe : Alto Saxophone

Recorded NYC --December 1977

Arthur Blythe - Alto

Bob Stewart - Tuba

Ahkmed Abdullah - Conga

A1. Mamie Lee

A2. For Fats

B1. Off The Top

B2. Bush Baby

(Columbia records,1979)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Blythe

Arthur Blythe (born July 5, 1940, in Los Angeles)[1] is an American jazz alto saxophonist and composer. His stylistic voice has a distinct vibrato and he plays within the post-bop subgenre of jazz.[1]

After moving to New York in the mid-70s, he worked as a security guard before being offered a place as sideman for Chico Hamilton[2] (75–77). He subsequently played with Gil Evans Orchestra (76–78), Lester Bowie ('78), Jack DeJohnette ('79) and McCoy Tyner ('79).[3] The Arthur Blythe band of 1979 – John Hicks, Fred Hopkins and Steve McCall – played Carnegie Hall and the Village Vanguard.

Blythe started to record as a leader in 1977 for the India Navigation label and then for Columbia records from 1978 to 1987. Albums such as The Grip and Metamorphosis (both on India Navigation) offered capable, highly refined jazz fare with a free angle that made Blythe too "out there" for the general public, but endeared him to the more serious jazz fans. Blythe played on many pivotal albums of the 1980s, among them Jack DeJohnette's Special Edition on ECM. Blythe was a member of the all-star jazz group The Leaders and, after the departure of Julius Hemphill, he joined the World Saxophone Quartet. Beginning in 2000 he made recordings on Savant Records which included Exhale (2003) with John Hicks (piano), Bob Stewart (tuba), and Cecil Brooks III (drums).

Allmusic biography

Bob Young and Al Stankus (1992). Jazz Cooks. Stewart Tabori and Chang. pp. 14–15. ISBN 1-55670-192-6.

A Fireside Chat With Arthur Blythe

by

At one time, Arthur Blythe was part of the Columbia machine (not unlike

the Miramax machine, how else do you explain the Gangs of New York

phenomenon). Then trends took precedent over music and a young Wynton

over a middle-aged Blythe (so the urban legend goes). Blythe still

managed to record a classic Lenox Avenue Breakdown. Blythe is a Horace

Tapscott throwback, having worked with the late Tapscott early in his

career. I spoke with Blythe and we talked about his days with Tapscott

and his years with Columbia, as always, unedited and in his own words.

All About Jazz: Let's start from the beginning.

Arthur Blythe: I think I sort of fell in love with the sound of the music, the way it made me feel. I just had to partake in that. I remember when I was real little, I was born here in LA. I was born on 53rd off Central Avenue, between Central and Hoover. There was this little club, a little eating place, but it had a jukebox in it. You could put a nickel in the machine and some entertainment would come out. I remember that I didn't have a nickel, but someone had placed one in just before I came up to the machine and I saw Cab Calloway in there. I didn't know who it was at the time, but after a period of time, I realized and found out that that was Cab Calloway. I was inspired by things like that. That was a long time ago, back in the early Forties.

FJ: My familiarity with your playing is through your collaborations with Horace Tapscott.

AB: Oh, yeah. We were good friends. I met him when I was about twenty-two, I think. I went to school in San Diego and I came back up to LA. I had relatives and I was living back and forth. I came back up and I met him through another musician friend. I was about twenty-two. He was rehearsing one time and I went over to a friend's house and Horace was having a rehearsal over there with his trio. They invited me to sit in with them and we seemed to hit it off pretty good right from the start. That started a long relationship musically with him. They loved him. They still do love him, but they seemed to have loved him quite a bit. It was very inspiring to me when I went over that day and sat in with him. It was very inspiring to me. It seemed like I had found my people so to speak.

FJ: While Tapscott remained in LA, you made your way to New York.

AB: That was about '74. I was just looking for brighter horizons. I was just getting frustrated with LA and not being able to expand. I was looking for something. I just wanted to get more involved. I just wanted to get involved more in the music, maybe more of the professional aspect of things.

FJ: Your trio of tuba and congas was not the conventional saxophone trio by any stretch of the imagination.

AB: Yeah, I don't know. I think it was about trying to be creative. The tuba was, my first exposure playing with the tuba was with Horace's thing. He used it in ensemble situations. When I was in New York, I knew the conga player from California. He used to play with Horace too. I got a gig with the Gil Evans Orchestra and I met this tuba player, Bob Stewart, and we seemed to be like minds also. He was adventurous and creative thinking. We just tried to make something happen. It was the instrumentation and the musicians too. We were trying to be creative.

FJ: How did the Columbia Records contract come about?

AB: I think that was around '79 or '80. I had the contract until '88.

FJ: And in that time, you recorded Lenox Avenue Breakdown featuring James Blood Ulmer and James Newton.

AB: Yeah, I think Blood and I found each other. We had done some things together, that loft jazz period was happening then. I knew Bob and I knew James already from California. I had met Jack (DeJohnette). I think I met Jack, he was auditioning. He needed a horn player for his group. I auditioned and during that period, I had gotten the contract with CBS (later became Columbia) and I asked him if he would do this record with me and he agreed. I needed a bassist and he recommended Cecil (McBee). He liked playing with Cecil. So we sort of met with the group. I brought them together and we came together. We made the record.

FJ: Did Columbia pressure your direction?

AB: I think they did. They made innuendoes, but I told them that I was staying stern on needing musical freedom. I was going to be conscious about giving them something that was positive and not something way out there or too far out there that wasn't musical. I was going to give them something musical. So they let me do what I wanted to do. I guess they were looking for something that was a little bit different too. That is the way it came off.

FJ: Did you have any inkling that Basic Blythe would be your last recording?

All About Jazz: Let's start from the beginning.

Arthur Blythe: I think I sort of fell in love with the sound of the music, the way it made me feel. I just had to partake in that. I remember when I was real little, I was born here in LA. I was born on 53rd off Central Avenue, between Central and Hoover. There was this little club, a little eating place, but it had a jukebox in it. You could put a nickel in the machine and some entertainment would come out. I remember that I didn't have a nickel, but someone had placed one in just before I came up to the machine and I saw Cab Calloway in there. I didn't know who it was at the time, but after a period of time, I realized and found out that that was Cab Calloway. I was inspired by things like that. That was a long time ago, back in the early Forties.

FJ: My familiarity with your playing is through your collaborations with Horace Tapscott.

AB: Oh, yeah. We were good friends. I met him when I was about twenty-two, I think. I went to school in San Diego and I came back up to LA. I had relatives and I was living back and forth. I came back up and I met him through another musician friend. I was about twenty-two. He was rehearsing one time and I went over to a friend's house and Horace was having a rehearsal over there with his trio. They invited me to sit in with them and we seemed to hit it off pretty good right from the start. That started a long relationship musically with him. They loved him. They still do love him, but they seemed to have loved him quite a bit. It was very inspiring to me when I went over that day and sat in with him. It was very inspiring to me. It seemed like I had found my people so to speak.

FJ: While Tapscott remained in LA, you made your way to New York.

AB: That was about '74. I was just looking for brighter horizons. I was just getting frustrated with LA and not being able to expand. I was looking for something. I just wanted to get more involved. I just wanted to get involved more in the music, maybe more of the professional aspect of things.

FJ: Your trio of tuba and congas was not the conventional saxophone trio by any stretch of the imagination.

AB: Yeah, I don't know. I think it was about trying to be creative. The tuba was, my first exposure playing with the tuba was with Horace's thing. He used it in ensemble situations. When I was in New York, I knew the conga player from California. He used to play with Horace too. I got a gig with the Gil Evans Orchestra and I met this tuba player, Bob Stewart, and we seemed to be like minds also. He was adventurous and creative thinking. We just tried to make something happen. It was the instrumentation and the musicians too. We were trying to be creative.

FJ: How did the Columbia Records contract come about?

AB: I think that was around '79 or '80. I had the contract until '88.

FJ: And in that time, you recorded Lenox Avenue Breakdown featuring James Blood Ulmer and James Newton.

AB: Yeah, I think Blood and I found each other. We had done some things together, that loft jazz period was happening then. I knew Bob and I knew James already from California. I had met Jack (DeJohnette). I think I met Jack, he was auditioning. He needed a horn player for his group. I auditioned and during that period, I had gotten the contract with CBS (later became Columbia) and I asked him if he would do this record with me and he agreed. I needed a bassist and he recommended Cecil (McBee). He liked playing with Cecil. So we sort of met with the group. I brought them together and we came together. We made the record.

FJ: Did Columbia pressure your direction?

AB: I think they did. They made innuendoes, but I told them that I was staying stern on needing musical freedom. I was going to be conscious about giving them something that was positive and not something way out there or too far out there that wasn't musical. I was going to give them something musical. So they let me do what I wanted to do. I guess they were looking for something that was a little bit different too. That is the way it came off.

FJ: Did you have any inkling that Basic Blythe would be your last recording?

AB: You know the strange thing about that, Fred. I

haven't received an eviction notice from them yet. They just evicted me

and I had to sort of figure that out. It wasn't a formal thing like they

weren't going to sign me again or they didn't need my services anymore.

They just backed off and let me figure it out. It was very weird. It

turned me off. I just haven't been able to get a major record company

deal also, but I was also fed up with those large companies at the time.

I am available now.

FJ: You have done a trio of records for Joe Fields' Savant label: Spirits in the Field, Blythe Byte, and Focus .

AB: Yeah, I recorded Spirits in the Field

at the Bimhuis. It was a live thing and I enjoyed it. We weren't

thinking about making a record at that time, but we got a pretty good

take on it, so we decided to try and make it into a record. It was a

tour that we had during that period. It was about three or four years

ago. It came off, so I decided to put it into record form.

FJ: Did you go with Fields' Savant label because of Cecil Brooks' already established relationship with the label?

AB:

Yeah, that was essentially what it was about. I didn't think about that

until after the performance. I wasn't recording it to give to Savant at

the time. It seemed to work out. I am trying to change it up a little

bit with Focus. I am trying to do something interesting, something organic. It came off that way.

FJ: Your rendition of "In a Sentimental Mood" certainly flies in the face of those whom have labeled you "avant-garde."

AB:

I thought it was in the pocket. That is where we were coming from,

playing it to specifications so to speak. I was playing the form and the

changes. The industry is, we live in a capitalistic society and

capitalism is part of the industry, a big part of it is about making

money. The artistic value is not their first objective. I think the

commercial value is more important. Then there are some record companies

that might not be as commercial as others, as far as wanting the money

first and being concerned about the money. But it is business and they

have to make some profit to stay in the business. Sometimes the choice

of music that the record companies choose is that which seems to

generate the business or the money. I guess they are within their rights

to do that. They have to keep the doors open and so they make the

decisions on what they want to support and what they don't want to

support musically. It is a business, so they have to do what they have

to do. I am not just avant-garde. I like to play all types of music as

much as I can play, straight-ahead or whatever they call that. I like

rhythm and blues. I like music with form, not atonal or aform. I am not

only there. Sometimes they put me into a weird bag and want me to be

weird, inaccessible. I think I am accessible.

FJ: Having returned to your Southern California roots, how much of a hassle has the hustle been?

AB:

Sometimes it is. Part of that is about having agencies and management.

It is a little different. The logistics are a little different here in

California. Everything is spread out so far and then you need someone

working for you on your behalf to get you work out here. Sometimes I can

work and sometimes I can't work. Some people have heard of me and some

people haven't. It seems like it is harder to do by myself. I need a

team, a team of people working on my behalf. It seems likes the business

or the industry looks for new talent all the time, fresh talent. Maybe I

am not fresh enough.

FJ: You are plenty fresh for me.

AB:

(Laughing) I appreciate that, Fred. I have been fortunate to still be

able to work in other places, in New York and nationally and

internationally too. I can work in Europe. I have some European work

coming up. It is a little difficult in LA.

FJ: And the future?

AB:

I have a record that is in the can right now. It will probably be out

sometime this year. This is with Cecil, Bob Stewart, and John Hicks. I

used piano and the tuba bass. I think it came out pretty good. We will

see.

https://hipstersanctuary.com/2014/05/08/black-arthur-jazz-icon-arthur-blythe-needs-your-help/

@blues2jazzguy

https://hipstersanctuary.com/2014/05/08/black-arthur-jazz-icon-arthur-blythe-needs-your-help/

BLACK ARTHUR ! JAZZ ICON ARTHUR BLYTHE NEEDS YOUR HELP

Growing up during the early 1960s people of my generation was soaking up a lot of “STUFF” politically, socially,economically and musically… some of the big guns that were speaking to the progressive Black youth were the artists of the so-called Avant Garde movement like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor and by the Late 60s, Black Arthur.. Arthur Blythe was spitting phrases on his alto like an Amiri Baraka poem.. hitting you in the gut with truth and spiritual bliss. His signature bluesy, buttery-vibrato laden tone. Unique band instrumentation was his calling card incorporating a tuba as a lead and comping instrument was not unusual for Blythe. The last time I saw him live was early 2004 at Yoshi’s Jazz house in Oakland California. He has been ill for a while now , including a serious daily battle with Parkinson’s Disease. He can no longer play or fend for himself on some days.. a “Help Arthur Fund” was set up over a year ago, and YOU CAN HELP with any amount of Donation. Just today, I spoke with one of his main caretakers, Mr. Gust Tsilis, longtime friend and fellow band member. yesterday, May 7 was Arthur’s 74th birthday. For more info on how to help with donations, please call (323) 251-0688

Please donate to the Arthur Blythe Parkinson’s fund

On June the 3rd, 2013, Arthur went into the USC Keck Center to have a large benign tumor removed from his right Kidney. The operation was serious, as Arthur spent one week after the procedure in an induced coma in their ICU unit. His health has been a challenge for him for several years now. The Parkinson’s (Arthur has been living with Parkinson’s for 8 years) has developed more rapidly and at this time he is in a rehabilitation center in Lancaster, CA. His goal is to be back home (?) within the next 30 days. The recent operation he underwent diminished his ability to walk and swallow foods. He is fighting hard each day to gain his strength back.

Please understand for Arthur to ask for help from his friends and fans, of his person and his music, was a difficult question he pondered over for some time. Arthur is a man of great pride and humility. His respect for people and their daily struggles has kept him from announcing his own dilemma for several years. Now he is facing an immediate need to procure a new neurologist to evaluate him after his recent surgery.

Arthur needs to remain in a secure place economically in order to fight Parkinson’s disease. Your donations will be a main source of his recovery. All the monies raised will be used to help him in his quest to regain his health and to stay current with his basic bills. Thank you in advance, with all sincerity and profound humility… from Arthur himself. Updates on his condition and the progress of this fund drive will be posted regularly. All of your good wishes and words will be read to Arthur.

Blythe, a 73-year-old San Diego native, made

his big splash on the jazz scene after he moved to New York in his

mid-30s and subsequently played with the Gil Evans Orchestra, Jack

DeJohnette and McCoy Tyner. Recorded for his ripe, passionate,

vibrato-rich sound, Blythe recorded on Columbia Records through much of

the 1980s and his most recent recorded appeared on the Savant label

between 2000 and 2003.

Arthur Blythe - "Illusions" (1980):

Arthur Blythe : Alto Saxophone

Abdul Wadud : Cello

Bobby Battle : Drums

James Blood Ulmer : Electric Guitar

Bob Stewart : Tuba

Arthur Blythe - "Bush Baby":

Recorded NYC --December 1977

Arthur Blythe - AltoBob Stewart - Tuba

Ahkmed Abdullah - Conga

A1. Mamie Lee

A2. For Fats

B1. Off The Top

B2. Bush Baby

Arthur Blythe-- "As of Yet":

"As of Yet" - 12:37

In Concert The Grip/Metamorphosis. * Arthur Blythe - alto

saxophone * Abdul Wadud - cello * Ahmed Abdullah - trumpet *

Bob Stewart - tuba * Steve Reid - drums * Muhamad Abdullah -

percussion India Navigation label Recorded at the Brook in New

York City on February 26, 1977.

Arthur Blythe - "Lower Nile":

The Grip (1977-- India Navigation label):

Arthur Blythe - alto sax

Abdul Wadud - cello

Ahmed Abdullah - trumpet

Bob Stewart - tuba

Steve Reid - drums

Arthur Blythe - "My Son Ra" from the 1980 album 'Illusions':

Arthur Blythe - alto saxophone

John Hicks - piano

Fred Hopkins - bass

Steve McCall - drums

Arthur Blythe - "Lenox Avenue Breakdown":

(Columbia records,1979)

Arthur Blythe – alto sax

James Newton – flute

Bob Stewart – tuba

James "Blood" Ulmer – guitar

Cecil McBee – bass

Jack DeJohnette – drums

Guillermo Franco – percussion

Arthur Blythe - "Faceless Woman":

Arthur Blythe - "Down San Diego Way (1979):

Arthur Blythe - "Odessa":

Arthur Blythe --"Epistrophy":

1983 album Light Blue: Arthur Blythe Plays Thelonious Monk

Arthur Blythe/Chico Freeman/McCoy Tyner:

Montreux 1981

The New York Montreux Connection: Arthur Blythe, Paquito D'Riviera, Jimmy Heath, Joe Ford, Percy Heath, McCoy Tyner, Chico Freeman, Slide Hampton, Phil Woods, Ronnie Burrage, John Blake, Stanley Cowell, John Hicks, Steve Mc Call; Montreux Jazz Festival July 18, 1981

Arthur Blythe Quartet: Live in Berlin 1980:

Arthur Blythe: as; Bob Stewart: tuba; Abdul Wadud: cello; Bobby Battle: dr at the Jazzfestival Berlin, November 1, 1980

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Blythe

Arthur Blythe

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Arthur Blythe | |

|---|---|

Arthur Blythe in 1989 at the North Sea Jazz Festival with The Leaders.

|

|

| Background information | |

| Born | July 5, 1940 [1] |

| Origin | Los Angeles |

| Genres | Jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Musician bandleader composer |

| Instruments | Alto saxophone |

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Labels | Columbia, Enja, Savant Records |

| Website | arthurblythe |

Arthur Blythe (born July 5, 1940, in Los Angeles)[1] is an American jazz alto saxophonist and composer. His stylistic voice has a distinct vibrato and he plays within the post-bop subgenre of jazz.[1]

Contents

Biography

Blythe lived in San Diego, returning to Los Angeles when he was 19 years old. He took up the alto saxophone at the age of nine, playing R&B until his mid-teens when he discovered jazz.[2] In the mid-1960s he was part of The Underground Musicians and Artists Association (UGMAA), founded by Horace Tapscott, on whose 1969 The Giant Is Awakened Blythe made his recording debut.After moving to New York in the mid-70s, he worked as a security guard before being offered a place as sideman for Chico Hamilton[2] (75–77). He subsequently played with Gil Evans Orchestra (76–78), Lester Bowie ('78), Jack DeJohnette ('79) and McCoy Tyner ('79).[3] The Arthur Blythe band of 1979 – John Hicks, Fred Hopkins and Steve McCall – played Carnegie Hall and the Village Vanguard.

Blythe started to record as a leader in 1977 for the India Navigation label and then for Columbia records from 1978 to 1987. Albums such as The Grip and Metamorphosis (both on India Navigation) offered capable, highly refined jazz fare with a free angle that made Blythe too "out there" for the general public, but endeared him to the more serious jazz fans. Blythe played on many pivotal albums of the 1980s, among them Jack DeJohnette's Special Edition on ECM. Blythe was a member of the all-star jazz group The Leaders and, after the departure of Julius Hemphill, he joined the World Saxophone Quartet. Beginning in 2000 he made recordings on Savant Records which included Exhale (2003) with John Hicks (piano), Bob Stewart (tuba), and Cecil Brooks III (drums).

Discography

As leader

| Year | Title | Label |

|---|---|---|

| 1977 | The Grip | India Navigation |

| 1977 | Metamorphosis | India Navigation |

| 1977 | Bush Baby | Adelphi |

| 1978 | In the Tradition | Columbia |

| 1978 | Lenox Avenue Breakdown | Columbia |

| 1980 | Illusions | Columbia |

| 1981 | Blythe Spirit | Columbia |

| 1982 | Elaborations | Columbia |

| 1983 | Light Blue: Arthur Blythe Plays Thelonious Monk | Columbia |

| 1984 | Put Sunshine in It | Columbia |

| 1986 | Da-Da | Columbia |

| 1987 | Basic Blythe | Columbia |

| 1996 | Calling Card | Enja |

| 1996 | Synergy | In + Out |

| 1991 | Hipmotism | Enja |

| 1997 | Today's Blues | CIMP |

| 1997 | Night Song | Clarity |

| 2000 | Spirits in the Field | Savant |

| 2001 | Blythe Byte | Savant |

| 2002 | Focus | Savant |

| 2003 | Exhale | Savant |

Collaborations

With Synthesis- Six by Six (Chiaroscuro, 1977), with Olu Dara, a.o.

- Segments (Ra, 1979), with Olu Dara, David Murray, a.o.

- Mudfoot (Black Hawk, 1986)

- Out Here Like This (Black Saint, 1987)

- Unforeseen Blessings (Black Saint, 1988)

- Slipping and Sliding (Sound Hills, 1994)

- Spirits Alike (Double Moon, 2006)

- Salutes the Saxophone – Tributes to John Coltrane, Dexter Gordon, Sonny Rollins and Lester Young (In & Out, 1992)

- Stablemates (In & Out, 1993)

- Say Something (In & Out, 1995)

- 3-Ology (Konnex, 1993)

- Ease On (Audio Quest, 1993)

- Synergy (In & Out, 1997)

- Echoes (Alessa, 2005)

As sideman

With Joey Baron- Down Home (Intuition, 1997) with Ron Carter and Bill Frisell

- We'll Soon Find Out (Intuition, 1999) with Ron Carter and Bill Frisell

- The 5th Power (Black Saint, 1978)

- African Children (Horo, 1978)

- Special Edition (ECM, 1979)

- Gil Evans Live at the Royal Festival Hall London 1978 (RCA, 1979)

- The Rest of Gil Evans Live at the Royal Festival Hall London 1978 (Mole Jazz, 1981)

- Parabola (Horo, 1979)

- Live at the Public Theater, Vol. 1 & 2 (Trio (Japan)/Storyville (Sweden), 1980)

- Priestess (Antilles, 1983)

- Sting and Gil Evans – Strange Fruit (ITM, 1993), three tracks with Blythe rec. 1976 without Sting

- 6 × 1 = 10 Duos for a New Decade (Circle, 1980)

- Luminous (Jazz House, 1989)

- Focus (Contemporary, 1995)

- Peregrinations (Blue Note, 1975)

- Chico Hamilton and the Players (Blue Note, 1976)

- Cold Sweat Plays J. B. (JMT, 1999)

- Coon Bid'ness (Freedom, 1972)

- Bridge into the New Age (Prestige, 1974)

- In the Name of... (DIW, 1994)

- Knights of Power (DIW, 1996)

- The Iron Men with Anthony Braxton (Muse, 1977 [1980])

- The Giant is Awakened (Flying Dutchman, 1969)

- Pale Fire (Enja, 1988)

- Quartets 4 X 4 (Milestone, 1980)

- 44th Street Suite (Red Baron,1991)

- Metamorphosis (Elektra Nonesuch, 1990)

- Breath of Life (Elektra Nonesuch, 1992)