SOUND PROJECTIONS

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

AN ONLINE QUARTERLY MUSIC MAGAZINE

EDITOR: KOFI NATAMBU

FALL, 2015

VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE

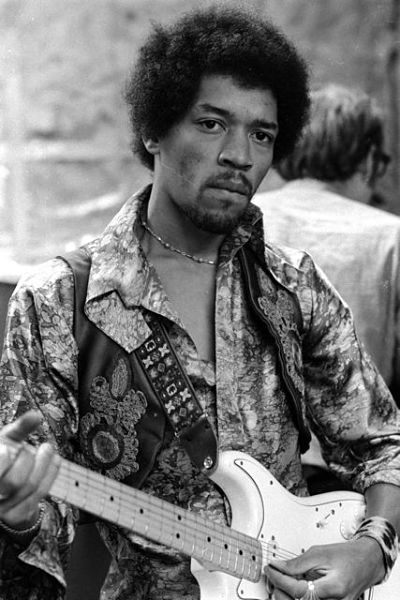

JIMI HENDRIX

Featuring the Musics and Aesthetic Visions of:

LAURA MVULA

October 10-16

DIZZY GILLESPIE

October 17-23

LESTER YOUNG

October 24-30

TIA FULLER

October 31-November 6

ROSCOE MITCHELL

November 7-13

MAX ROACH

November 14-20

DINAH WASHINGTON

November 21-27

BUDDY GUY

November 28-December 4

JOE HENDERSON

December 5-11

HENRY THREADGILL

December 12-18

MUDDY WATERS

December 19-25

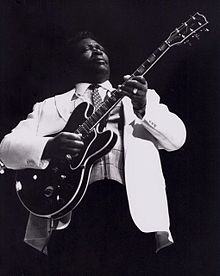

B.B. KING

December 26-January 1

http://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/b-b-king/biography

B.B. King

Biography

Rolling Stone

B.B. KING

(1925-2015)

B.B. King is the most famous of the modern bluesmen. Playing his trademark Gibson guitar, which he refers to affectionately as Lucille, King's lyrical leads and left-hand vibrato have influenced numerous rock guitarists, including Eric Clapton, Mike Bloomfield, and David Gilmour of Pink Floyd. A fifteen-time Grammy winner, King has received virtually every music award, including the Grammy for Lifetime Achievement in 1987.

Born Riley B. King on September 16, 1925, in Itta Bena, Mississippi, he picked cotton as a youth. In the Forties he played on the streets of Indianola before moving on to perform professionally in Memphis around 1949. As a young musician, he studied recordings by both blues and jazz guitarists, including T-Bone Walker, Charlie Christian, and Django Reinhardt.

In the early Fifties King was a disc jockey on the Memphis black station WDIA, where he was dubbed the "Beale Street Blues Boy." Eventually, Blues Boy was shortened to B.B., and the nickname stuck. The radio show and performances in Memphis with friends Johnny Ace and Bobby "Blue" Bland built King's strong local reputation. One of his first recordings, "Three O'Clock Blues" (Number One R&B), for the RPM label, was a national success in 1951. During the Fifties, King was a consistent record seller and concert attraction.

King's 1965 Live at the Regal is considered one of the definitive blues albums. The mid-Sixties blues revival introduced him to white audiences, and by 1966 he was appearing regularly on rock concert circuits and receiving airplay on progressive rock radio. He continued to have hits on the soul chart ("Paying the Cost to Be the Boss," Number Ten R&B, 1968) and always maintained a solid black following. Live and Well was a notable album, featuring "Why I Sing the Blues" (Number 13 R&B, 1969) and King's only pop Top Twenty single, "The Thrill Is Gone" (Number 15 pop, Number Three R&B, 1970).

In the Seventies King also recorded albums with longtime friend and onetime chauffeur Bobby Bland: the gold Together for the First Time...Live (1974) and Together Again...Live (1976). Stevie Wonder produced King's "To Know You Is to Love You." In 1982 King recorded a live album with the Crusaders.

King's tours have taken him to Russia (1979), South America (1980), and to dozens of prisons. In 1981 There Must Be a Better World Somewhere won a Grammy Award; he won another in 1990 for Live at San Quentin. He was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 1984, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987. In 1990 he received the Songwriters Hall of Fame Lifetime Achievement Award. In May 1991, he opened B.B. King's Blues Club in Memphis. (A second one opened in New York City in 2000.)

In 1989 he sang and played with U2 on "When Love Comes to Town," from their Rattle and Hum. The four-disc box set released that same year, King of the Blues, begins with King's career-starting single "Miss Martha King," originally released on Bullet in 1949. For Blues Summit, in 1993, King was joined by such fellow bluesmen as John Lee Hooker, Lowell Fulson, and Robert Cray.

King once said he aspired to be an "ambassador of the blues," and by the Nineties he seemed to have attained just that iconic status. In 1995 he received the Kennedy Center Honors. The next year saw the publication of his award-winning autobiography, Blues' All Around Me (coauthored with David Ritz).

In 2000 the double-platinum Riding With the King (with Eric Clapton) topped Billboard's Top Blues Albums chart. King continued to record, perform and win honors during the first decade of the 2000s. President George W. Bush awarded King the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2006. Two years later, he released one of the most critically acclaimed studio albums of his career, the back-to-the-basics One Kind Favor, produced by T Bone Burnett and featuring King doing stripped-down version of blues classics such as Blind Lemon Jefferson's "See That My Grave Is Kept Clean."

Portions of this biography appeared in The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (Simon & Schuster, 2001). Mark Kemp contributed to this article.

Read more: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/b-b-king/biography#ixzz3vLClbtE3

Follow us: @rollingstone on Twitter | RollingStone on Facebook

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/bb-king-mn0000059156/biography

B.B. KING (1925-2015)Artist Biography by Bill Dahl

Universally hailed as the king of the blues, the legendary B.B. King was without a doubt the single most important electric guitarist of the last half of the 20th century. His bent notes and staccato picking style influenced legions of contemporary bluesmen, while his gritty and confident voice -- capable of wringing every nuance from any lyric -- provided a worthy match for his passionate playing. Between 1951 and 1985, King notched an impressive 74 entries on Billboard's R&B charts, and he was one of the few full-fledged blues artists to score a major pop hit when his 1970 smash "The Thrill Is Gone" crossed over to mainstream success (engendering memorable appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show and American Bandstand). After his hit-making days, he partnered with such musicians as Eric Clapton and U2 and managed his own acclaimed solo career, all the while maintaining his immediately recognizable style on the electric guitar.

The seeds of Riley B. King's enduring talent were sown deep in the blues-rich Mississippi Delta, where he was born in 1925 near the town of Itta Bena. He was shuttled between his mother's home and his grandmother's residence as a child, his father having left the family when King was very young. The youth put in long days working as a sharecropper and devoutly sang the Lord's praises at church before moving to Indianola -- another town located in the heart of the Delta -- in 1943.

Country and gospel music left an indelible impression on King's musical mindset as he matured, along with the styles of blues greats (T-Bone Walker and Lonnie Johnson) and jazz geniuses (Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt). In 1946, he set off for Memphis to look up his cousin, a rough-edged country blues guitarist named Bukka White. For ten invaluable months, White taught his eager young relative the finer points of playing blues guitar. After returning briefly to Indianola and the sharecropper's eternal struggle with his wife Martha, King returned to Memphis in late 1948. This time, he stuck around for a while.

King was soon broadcasting his music live via Memphis radio station WDIA, a frequency that had only recently switched to a pioneering all-black format. Local club owners preferred that their attractions also held down radio gigs so they could plug their nightly appearances on the air. When WDIA DJ Maurice "Hot Rod" Hulbert exited his air shift, King took over his record-spinning duties. At first tagged "The Peptikon Boy" (an alcohol-loaded elixir that rivaled Hadacol) when WDIA put him on the air, King's on-air handle became "The Beale Street Blues Boy," later shortened to Blues Boy and then a far snappier B.B.

King had a four-star breakthrough year in 1949. He cut his first four tracks for Jim Bulleit's Bullet Records (including a number entitled "Miss Martha King" after his wife), then signed a contract with the Bihari Brothers' Los Angeles-based RPM Records. King cut a plethora of sides in Memphis over the next couple of years for RPM, many of them produced by a relative newcomer named Sam Phillips (whose Sun Records was still a distant dream at that point in time). Phillips was independently producing sides for both the Biharis and Chess; his stable also included Howlin' Wolf, Rosco Gordon, and fellow WDIA personality Rufus Thomas.

the Biharis also recorded some of King's early output themselves, erecting portable recording equipment wherever they could locate a suitable facility. King's first national R&B chart-topper in 1951, "Three O'Clock Blues" (previously waxed by Lowell Fulson), was cut at a Memphis YMCA. King's Memphis running partners included vocalist Bobby Bland, drummer Earl Forest, and ballad-singing pianist Johnny Ace. When King hit the road to promote "Three O'Clock Blues," he handed the group, known as the Beale Streeters, over to Ace.

It was during this era that King first named his beloved guitar "Lucille." Seems that while he was playing a joint in a little Arkansas town called Twist, fisticuffs broke out between two jealous suitors over a lady. The brawlers knocked over a kerosene-filled garbage pail that was heating the place, setting the room ablaze. In the frantic scramble to escape the flames, King left his guitar inside. He foolishly ran back in to retrieve it, dodging the flames and almost losing his life. When the smoke had cleared, King learned that the lady who had inspired such violent passion was named Lucille. Plenty of Lucilles have passed through his hands since; Gibson has even marketed a B.B.-approved guitar model under the name.

The 1950s saw King establish himself as a perennially formidable hitmaking force in the R&B field. Recording mostly in L.A. (the WDIA air shift became impossible to maintain by 1953 due to King's endless touring) for RPM and its successor Kent, King scored 20 chart items during that musically tumultuous decade, including such memorable efforts as "You Know I Love You" (1952); "Woke Up This Morning" and "Please Love Me" (1953); "When My Heart Beats like a Hammer," "Whole Lotta' Love," and "You Upset Me Baby" (1954); "Every Day I Have the Blues" (another Fulson remake), the dreamy blues ballad "Sneakin' Around," and "Ten Long Years" (1955); "Bad Luck," "Sweet Little Angel," and a Platters-like "On My Word of Honor" (1956); and "Please Accept My Love" (first cut by Jimmy Wilson) in 1958. King's guitar attack grew more aggressive and pointed as the decade progressed, influencing a legion of up-and-coming axemen across the nation.

In 1960, King's impassioned two-sided revival of Joe Turner's "Sweet Sixteen" became another mammoth seller, and his "Got a Right to Love My Baby" and "Partin' Time" weren't far behind. But Kent couldn't hang onto a star like King forever (and he may have been tired of watching his new LPs consigned directly into the 99-cent bins on the Biharis' cheapo Crown logo). King moved over to ABC-Paramount Records in 1962, following the lead of Lloyd Price, Ray Charles, and before long, Fats Domino.

Live at the Regal

In November of 1964, the guitarist cut his seminal Live at the Regal album at the fabled Chicago theater and excitement virtually leaped out of the grooves. That same year, he enjoyed a minor hit with "How Blue Can You Get," one of his many signature tunes. "Don't Answer the Door" in 1966 and "Paying the Cost to Be the Boss" two years later were Top Ten R&B entries, and the socially charged and funk-tinged "Why I Sing the Blues" just missed achieving the same status in 1969.

Across-the-board stardom finally arrived in 1969 for the deserving guitarist, when he crashed the mainstream consciousness in a big way with a stately, violin-drenched minor-key treatment of Roy Hawkins' "The Thrill Is Gone" that was quite a departure from the concise horn-powered backing King had customarily employed. At last, pop audiences were convinced that they should get to know King better: not only was the track a number-three R&B smash, it vaulted to the upper reaches of the pop lists as well.

Love Me Tender

King was one of a precious few bluesmen to score hits consistently during the 1970s, and for good reason: he wasn't afraid to experiment with the idiom. In 1973, he ventured to Philadelphia to record a pair of huge sellers, "To Know You Is to Love You" and "I Like to Live the Love," with the same silky rhythm section that powered the hits of the Spinners and the O'Jays. In 1976, he teamed up with his old cohort Bland to wax some well-received duets. And in 1978, he joined forces with the jazzy Crusaders to make the gloriously funky "Never Make Your Move Too Soon" and an inspiring "When It All Comes Down." Occasionally, the daring deviations veered off-course; Love Me Tender, an album that attempted to harness the Nashville country sound, was an artistic disaster.

Blues Summit

Although his concerts were consistently as satisfying as anyone in the field (King asserted himself as a road warrior of remarkable resiliency who gigged an average of 300 nights a year), King tempered his studio activities somewhat. Nevertheless, his 1993 MCA disc Blues Summit was a return to form, as King duetted with his peers (John Lee Hooker, Etta James, Fulson, Koko Taylor) on a program of standards. Other notable releases from that period include 1999's Let the Good Times Roll: The Music of Louis Jordan and 2000's Riding with the King, a collaboration with Eric Clapton. King celebrated his 80th birthday in 2005 with the star-studded album 80, which featured guest spots from such varied artists as Gloria Estefan, John Mayer, and Van Morrison. Live was issued in 2008; that same year, King released an engaging return to pure blues, One Kind Favor, which eschewed the slick sounds of his 21st century work for a stripped-back approach. A long overdue career-spanning box set of King's over 60 years of touring, recording, and performing, Ladies and Gentlemen...Mr. B.B. King, appeared in 2012. Late in 2014, King was forced to cancel several shows due to exhaustion; he was later hospitalized twice and entered hospice care in the spring. He died in Las Vegas, Nevada, on May 14, 2015.

https://rockhall.com/inductees/bb-king/bio/

B.B. KING BIOGRAPHY

B.B. King (guitar, vocals; born September 16, 1925 – May 14, 2015)

Riley “B.B.” King has been called the “King of the Blues” and “Ambassador of the Blues,” and indeed he’s reigned across the decades as the genre’s most recognizable and influential artist. His half-century of success owes much to his hard work as a touring musician who consistently logged between 200 and 300 shows a year. Through it all he’s remained faithful to the blues while keeping abreast of contemporary trends and deftly incorporating other favored forms - jazz and pop, for instance - into his musical overview. Much like such colleagues and contemporaries as Buddy Guy and John Lee Hooker, B.B. King managed to change with the changing times while adhering to his blues roots.

As a guitarist, King is best-known for his single-note solos, played on a hollowbody Gibson guitar. King’s unique tone is velvety and regal, with a discernible sting. He’s known for his trilling vibrato, wicked string bends, and a judicious approach that makes every note count. Back in the early days, King nicknamed his guitar “Lucille,” as if it were a woman with whom he was having a dialogue. In fact, King regards his guitar as an extension of his voice (and vice versa). “The minute I stop singing orally,” King has noted, “I start to sing by playing Lucille.”

There have been many Lucilles over the years, and Gibson has even marketed a namesake model with King’s approval. King selected the name in the mid-Fifties after rescuing his guitar from a nightclub fire started by two men arguing over a woman. Her name? Lucille.

King doesn’t play chords or slide; instead, he bends individual strings till the notes seem to cry. His style reflects his upbringing in the Mississippi Delta and coming of age in Memphis. Seminal early influences included such bluesmen as T-Bone Walker (whose “Stormy Monday,” King has said, is “what really started me to play the blues”), Lonnie Johnson, Sonny Boy Williamson and Bukka White. A cousin of King’s, White schooled the fledgling guitarist in the idiom when he moved to Memphis. King also admired jazz guitarists Charlie Christian and Django Reinhart. Horns have played a big part in King’s music, and he’s successfully combined jazz and blues in a big-band context.

“I’ve always felt that there’s nothing wrong with listening to and trying to learn more,” King has said. “You just can’t stay in the same groove all the time.” This willingness to explore and grow explains King’s popularity across five decades in a wide variety of venues, from funky juke joints to posh Las Vegas lounges.

More than any other musician of the postwar era, King brought the blues from the margins to the mainstream. His influence on a generation of rock and blues guitarists - including Eric Clapton, Mike Bloomfield and Stevie Ray Vaughan - has been inestimable. “We don’t play rock and roll,” he said in 1957. “Our music is blues, straight from the Delta.” Yet without formally crossing into rock and roll, King forged an awareness of blues within the rock realm, particularly in the Sixties and Seventies.

Born on a cotton plantation in tiny Itta Bena, Mississippi, in 1925, King moved to Memphis, Tennessee in his early twenties with the intention of making his living playing the blues. He landed a regular spot as a deejay and performer on radio station WDIA, where he became known as the Beale Street Blues Boy (hence, “B.B."). King also built a reputation as a hot guitarist at the Beale Street blues clubs, performing with a loose-knit group known as the Beale Streeters. This group included vocalist Bobby Blue Bland, a longtime peer and collaborator.

King began recording in 1949 and signed with West Coast record man Jules Bihari a year later. He would record prolifically for the Bihari brothers’ labels - RPM, Kent and Crown - through 1962. King’s first hit, “Three O’Clock Blues,” topped the rhythm & blues chart for five weeks in 1952. Other classics cut by King in the Fifties include “Sweet Black Angel,” “Every Day I Have the Blues” and three more R&B chart-toppers: “You Know I Love You,” “Please Love Me” and “You Upset Me Baby.”

Dissatisfied with royalty rates and songwriting credits, King signed with ABC-Paramount in the early Sixties, when his contract with the Biharis expired. At that time, ABC was cultivating a stable of black artists that included Ray Charles, Lloyd Price and Fats Domino. They paired King with an arranger, and his studio records took on a more polished, sophisticated and eclectic tone. Pushing the blues in new directions, King was rewarded with such breakthrough hits as “The Thrill Is Gone,” which featured his soulful voice and guitar over a backdrop of strings. He also cut raw, energetic concert LPs - Live at the Regal (1965) and Live at Cook County Jail (1971) - that are classics of the genre.

Live at the Regal, recorded before a lively crowd at a black Chicago nightspot of longstanding, is the perfect match between performer and audience, with the latter’s enthusiasm fuelling the former’s fire. Other highlights of his lengthy tenure at ABC include a pair of mid-Seventies live albums with Bobby Blue Bland and Midnight Believer, a jazzy collaboration with the Crusaders. Blues purists treasure such back-to-the-roots efforts as Lucille Talks Back (1975) and Blues ‘n’ Jazz (1983). Favorites of rock fans include Indianola Mississippi Seeds (1970), which found King joined by Leon Russell, Joe Walsh and Carole King; B.B. King in London (1971), made with a host of British rock musicians; and Riding With the King (2000), a collaboration with Eric Clapton. King won Grammy Awards for Best Traditional Blues Recording for Live at the Apollo (1991) and Blues Summit (1993).

Through it all, King has toured as prolifically as any performer in history. The road has been him home since the mid-Fifties. He reportedly performed 342 shows one year, and he’d average more than 200 shows annually even into his seventies. Each June he sets aside a few weeks for himself, going back to Indianola for what he calls “the Mississippi Homecoming.”

At the start of his career, King’s reach didn’t extend beyond the network of clubs and juke joints known as the chitlin’ circuit. Somewhat prophetically he noted, “We don’t play for white people…. I’m not saying we won’t play for whites, because I don’t know what the future holds. Records are funny. You aim them for the colored market, then suddenly the white folks like them, then wham, you’ve got whites at your dances.”

Sure enough, in the mid-Sixties, King’s hard work, musical genius, affable persona and revered stature among rock icons broadened his base of support to include a new audience of white listeners who tuned into the blues and stuck with King for the long haul. King came to the attention of yet another generation of younger listeners when he recorded “When Love Comes to Town” in 1988 with U2 for their Rattle and Hum album and movie.

“B.B. King’s achievement has been to take the primordial music he heard as a kid, mix and match it with a bewildering variety of other musics, and bring it all into the digital age,” Colin Escott wrote in his essay for the King of the Blues box set. “There will probably never be another musical journey comparable to [King’s].”

The final word belongs to King himself, testifying on the healing quality of the genre he embodies. “I’m trying to get people to see that we are our brother’s keeper,” King has said. “Red, white, black, brown or yellow, rich or poor, we all have the blues.”

B.B. King passed away on May 14, 2015. He was 89.

- See more at: https://rockhall.com/inductees/bb-king/bio/#sthash.kzFSiZQC.dpuf

http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2015/05/bb_king_dead_at_89_remembering_live_at_the_regal_s_three_song_medley_the.html

Culturebox

Arts, entertainment, and more

May 15 2015

B.B. King’s Greatest Performance

The three-song medley at the heart of his masterpiece may be the best 12 minutes of live musical performance ever recorded.

by Jack Hamilton

SLATE

B.B. King, a titan of American music who died Thursday at 89 years old, lived for so long, did so much, and was so deeply woven into our cultural fabric that it was easy to take him for granted. “The King of the Blues,” he was called, although too often in the offhanded and unthinking tone in which people call Budweiser the King of Beers. King was a singer and guitar player of unfathomable depth and dimension, and his music was a watershed: In the middle part of the 20th century, no performer so effortlessly melded country blues to the more urban, “modern” sounds of post–World War II rhythm and blues than King: not Muddy Waters, not Howlin’ Wolf, not the still-missed Bobby “Blue” Bland. Already on his first major hit, 1951’s “3 O’Clock Blues,” King exemplified this fusion in spades: the urbane and jazz-inflected guitar playing, the lush and billowing horns, the vocal performance that seems to channel Lonnie Johnson and Blind Lemon Jefferson out of one lung, Jimmy Rushing and Frank Sinatra out of the other.

Writing about 89-plus years of B.B. King’s life quickly starts to feel like writing a history of American pop music itself—he spent his boyhood picking cotton in the Mississippi Delta and his twilight years as a capitalized National Treasure, a living metonym for the blues. So instead I will write about a scant 12 minutes of B.B. King’s life, the three-song medley of “Sweet Little Angel,” “It’s My Own Fault,” and “How Blue Can You Get?” that sprawls over the first side of King’s masterpiece, Live at the Regal. This medley is, in my completely subjective and admittedly grief-stricken opinion, the greatest 12 minutes of live musical performance ever recorded. It should be mandatory listening today, and for everyone of every generation to come.

Live at the Regal, recorded at Chicago’s Regal Theater in 1964 and released in 1965, kicks off, first, with a blisteringly fast rendition of “Every Day I Have the Blues.” The dust settles and the crowd is already convulsing; the band starts noodling behind B.B., who announces his intention to go back and “pick up some of the real old blues. If we should happen to play one that you remember, let us know it by making some noise.” Noise shall soon be made.

“Sweet Little Angel” comes in like a thunderbolt. B.B. plucks an ascending triplet line, drummer Sonny Freeman detonates his snare drum on the downbeat, and we’re off. B.B. plays an opening chorus of guitar solo, then leans into the first verse. “I’ve got a sweet little angel/ I love the way she spreads her wings,” he croons, a line that’s older than the Delta soil but sounds newly exquisite each time you hear it. (A quick, woefully incomplete genealogy: Lucille Bogan sang, “I’ve got a sweet black angel/ I like the way he spreads his wings,” on 1930’s “Black Angel Blues,” probably the earliest recorded instance of the line. King claimed to have nicked the phrase from Robert Nighthawk, who recorded his own version of “Black Angel Blues” but changed the name to “Sweet Black Angel.” The Rolling Stones then borrowed that title—after their 1969 tour with King—for their tribute to Angela Davis on 1972’s Exile on Main St. A mindboggling amount of musical history ran through and around B.B. King.)

It’s 1964, and B.B.-mania is in full swing.

King was 39 when he recorded Live at the Regal—not exactly a spring chicken, but he was at the apex of his abilities as a singer. His control on “Sweet Little Angel” is virtuosic, shifting from gospel belt to sultry croon to his swooping, heavenly falsetto. His voice quivers, growls, thrills, teeters on the brink of combustion. “Sweet Little Angel” is a song of tribute and awed devotion—“I asked my baby for a nickel/ and she gave me a $20 bill”—until we hit the last verse. “If my baby quit me, I do believe I would die/ If you don’t love me, little angel/ Please tell me the reason why.” A plot-twist ending: It’s a goddamn breakup song. And right as the realization hits, the guitar solo comes in, and the whole world falls away.

No one has ever played electric guitar quite like B.B. King—what he lacked in technical chops he made up for with gifts of melody, phrasing, and cerebral precision that, among improvisational soloists, place him in the company of Miles Davis and no one else. The solo coming out of “Sweet Little Angel” is a masterpiece of tone, range, and above all restraint. The spaces between King’s phrases are as thrilling as the phrases themselves; he lingers and sustains where a less assured musician would dash to the next idea; his mastery of dynamics is so complete that each string seems to have its own voice, and its own breath. Every note is perfect from the moment it appears to the moment it recedes.

And he’s just getting started. As King’s solo ends, the band keeps playing the groove, the great pianist Duke Jethro sprinkling fills as B.B. works the crowd with stage patter. Soon they go into “It’s My Own Fault,” a hammy catalog of romantic misbehavior: “She used to make her own paychecks/ and bring them on home to me/ I would go out on the hillside/ and make every woman drunk.” A tenor saxophone weaves call-and-response with King’s vocal, Sonny Freeman cracks the two and four with increasing ferocity. On the heels of the last verse, King takes another guitar solo, this one gnarlier and more flamboyant than the last, with scalding 16th-note runs nestled against what is now an avalanche of female screams. It’s 1964, and B.B.-mania is in full swing. Pulling out of the turnaround, the band modulates up a half-step, into the medley’s closing number, “How Blue Can You Get?”

B.B. instructs the audience to “pay attention to the lyrics, not so much my singing or the band,” then rips off yet another chorus of guitar solo that revels in the absurdity of this request. And the lyrics aren’t even that good: As blues standards go, “How Blue Can You Get?” is a little too direct, too single-entendre, its famous opening line—“I’ve been downhearted, baby/ ever since the day we met”—bereft of the vague, sumptuous poetry of a couplet like “I’ve got a sweet little angel/ I love the way she spreads her wings.”

But good Lord, does B.B. sell this one. “How Blue Can You Get?” on Live at the Regal is pure incendiary ecstasy, all the way through to its shattering, stop-time climax. Everyone in this club knows this song; everyone in this club is reacting as though it is being written on the spot. When we reach the song’s applause line—“I gave you seven children/ and now you want to give them back” (God, who says this to someone?)—B.B. leans into “gaaave” with such force it seems to upend the whole building.

“How Blue Can You Get?” doesn’t end so much as collapse into a heap of exhaustion. The crowd goes berserk, the only conceivable response to 12 minutes of music that does just about everything one could ever hope music to do. John Lennon once described the blues as “a chair, not a design for a chair or a better chair. … You sit on that music.” Somewhere right now B.B. King is sitting on that chair, like a throne.

Jack Hamilton is Slate’s pop critic. He is assistant professor of American studies and media studies at the University of Virginia. Follow him on Twitter.

http://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/may/15/bb-king-obituary-mississippi-farmhand-blues-legend

BB King obituary

Self-deprecating but with a magisterial stage presence, King developed a style that was both innovative and rooted in blues history

A look back at the life of blues guitarist and singer BB King

by Tony Russell

15 May 2015

The Guardian

VIDEO: <iframe src="https://embed.theguardian.com/embed/video/music/video/2015/may/15/blues-bb-king-dies-aged-89-video-obituary" width="560" height="315" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

BB King, who has died aged 89, was the most influential blues musician of his generation and the music’s most potent symbol. He represented the blues as Louis Armstrong once represented jazz, a single performer who could nevertheless stand, and speak, for the whole genre.

'We all have the blues': tributes pour in after BB King dies aged 89

Although much of his work, and arguably nearly all the best of it, was firmly within the discipline of the blues, King was unfailingly open-minded and interested when he found himself in other settings, bridging musical and cultural differences with affability and skill untainted by self-importance. More than 50 years ago the death of Big Bill Broonzy prompted writers to speak of “the last of the bluesmen”: it was premature then, as it would be to say it now, but it is hard to imagine any future blues artist matching King’s sway, in a career spanning 65 years, over musicians by the thousand and audiences by the million.

Son of Albert and Nora Ella, Riley B King (the B did not seem to stand for a name) was born near Itta Bena, Mississippi, and grew up with the limited prospects of an African-American agricultural worker, a barrier he gradually worked to overcome as he learned the basics of guitar from a family friend and honed his singing with a quartet, the St John Gospel Singers of Indianola. In his early 20s he moved to Memphis, at first staying with the blues singer and guitarist Booker White, his cousin.

Within a couple of years, thanks to some help from Sonny Boy Williamson, he had secured a residency at the Sixteenth Street Grill in West Memphis, Arkansas. He also became a disc jockey, presenting a show on the Memphis radio station WDIA. His billing, “The Beale Street Blues Boy”, was whittled down to “Blues Boy King” and thence to “BB”. After a single session in 1949 for the Nashville label Bullet, King began recording for the West Coast-based Modern Records in 1950.

BB King was that rare thing – a game-changer who was also beloved

He had his first hit in 1952, with a dramatic rearrangement of Lowell Fulson’s Three O’Clock Blues, which topped the R&B chart for 15 weeks; it headed a list of successes such as Please Love Me, You Upset Me Baby, Ten Long Years, Sweet Little Angel and Sweet Sixteen. On these and his dozens of other recordings, most of them his own compositions, King developed a style that was both innovative and rooted in blues history. He was always ready to extol the musicians who had influenced him, and would usually mention T-Bone Walker first.

“I’ve tried my best to get that sound,” he told Guitar Player magazine. “I came pretty close, but never quite got it.” In an interview in the Guardian in 2001, he said: “If T-Bone Walker had been a woman I would have asked him to marry me.” But he would also cite the earlier blues guitarists Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson and the jazz players Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt.

Disarmingly, he once explained that his guitar technique was partly based on his lack of skill: “I started to bend notes because I could never play in the bottleneck style, like Elmore James and Booker White. I loved that sound but just couldn’t do it.” He was similarly self-deprecating about his singing, a sumptuous blend of honey and lemon, mixed half-and-half from crooners such as Nat King Cole or Al Hibbler and blues shouters such as Joe Turner and Dr Clayton. Probably his favourite composer and singer was Louis Jordan, whose buoyant, funny music he commemorated in the 1999 album Let the Good Times Roll.

Throughout the 1950s, King was the leading blues artist on the circuit of black-patronised theatres and clubs, wearing out buses, if not bandsmen, on interminable series of one-nighters. In 1956 he is supposed to have filled 342 engagements. In 1962. he ventured to change that working pattern, rather like Ray Charles, by signing with a major label, ABC, but the first records under that contract, which tried to reshape him as a mainstream pop singer, were as unsatisfactory to his admirers as they were to ABC’s accountants.

The 1965 album Live at the Regal, however, proved the durability of King’s core blues repertoire as well as his magisterial stage presence, and has become iconic, a turning-point in the early listening of many younger musicians. He had further R&B hits with blues numbers including How Blue Can You Get?, Don’t Answer the Door and Paying the Cost to Be the Boss, and in 1969 he hit the upper reaches of the pop charts – territory where no blues artist had stepped for many years – with the subtly orchestrated The Thrill Is Gone.

It took him a while to establish himself with a rock audience, for whom the blues was largely defined by the Chicago school of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, but he was brought forcibly to their attention by musicians who admired him. “About a year and a half ago,” he said in 1969, “all of a sudden kids started coming up to me saying, ‘You’re the greatest blues guitarist in the world.’ And I’d say, ‘Who told you that?’ And they’d say, ‘Mike Bloomfield’, or ‘Eric Clapton’. It’s due to these youngsters that I owe my new popularity.” He acquired further rock credibility with the 1970 album Indianola Mississippi Seeds, on which he collaborated with Carole King and Joe Walsh and scored another enduring hit with Leon Russell’s song Hummingbird.

BB King at 87: the last of the great bluesmen

From then on, King was immovably established as, in someone’s neat phrase, “the chairman of the board of blues singers”. Imaginatively steered by his manager Sidney Seidenberg, he embarked on international concert tours that took him to Japan and Australia, and eventually to China and Russia. He also gave concerts to prisoners at the Cook County jail in Chicago and at San Quentin, experiences that led to his long involvement in rehabilitation programmes.

A dedicated player of Gibson guitars, he was featured in advertisements for the company, which created a special model named after the succession of Gibson ES 355s that he called Lucille. He also lent his name to advertising campaigns for Pepsi-Cola, the AT&T communications network and Cutty Sark whisky, and to clubs in Memphis and Los Angeles.

The “chitlin circuit” now far behind him, he appeared at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, won approving notices from Playboy magazine, sang the theme-song for the television sitcom The Associates and the title number of the 1985 film Into the Night, was elected an honorary doctor of music at Yale and received innumerable awards from blues and guitar magazines. He recorded prolifically with luminaries in other fields, from the Crusaders, Branford Marsalis and Stevie Wonder to the Rolling Stones, Van Morrison, Willie Nelson and U2, with the last of whom he made the exuberant When Love Comes to Town in 1988.

In 1990, King was diagnosed with diabetes and cut back his touring, but not so much that his followers outside the US could not catch up with him every year or two. Though he would now deliver most of his act seated, the strength of his singing and the fluency of his playing were only very gradually diminished. The celebrations for his 80th birthday in 2005 included a Grammy award-winning album of collaborations with Clapton, Mark Knopfler, Roger Daltrey, Gloria Estefan and others, a garland of tributes from musicians as diverse as Bono, Amadou Bagayoko and Elton John, and a “farewell tour” that proved not to be a farewell at all.

In 2008, the BB King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center was opened in Indianola, and in 2009 King received a Grammy award, for best traditional blues album, for One Kind Favor. In 2012 he was celebrated in the documentary The Life of Riley; and also performed at a concert at the White House, where the US president, Barack Obama, joined him to sing Sweet Home Chicago.

King was twice married and twice divorced. He is survived by 11 children by various partners; four others predeceased him.

• BB King (Riley King), blues musician, born 16 September 1925; died 14 May 2015

http://panopticonreview.blogspot.com/2015/05/the-inspiring-life-art-and-legacy-of-bb.html

Saturday, May 16, 2015

The Inspiring Life, Art, and Legacy of B.B. King: 1925-2015

All,

A REAL ORIGINAL ARTIST HAS LEFT THE BUILDING. What a GIANT Mr. King was, is, and will always be. He brought a lot of joy, pride, dignity, and honor via his indelible and always captivating art to not only black folks but the entire world. Thank you forever Mr. King. Your tremendous legacy and all that it stands for and embodies will never die...May your enormously generous and profound spirit rest in eternal peace...

Kofi

A REAL ORIGINAL ARTIST HAS LEFT THE BUILDING. What a GIANT Mr. King was, is, and will always be. He brought a lot of joy, pride, dignity, and honor via his indelible and always captivating art to not only black folks but the entire world. Thank you forever Mr. King. Your tremendous legacy and all that it stands for and embodies will never die...May your enormously generous and profound spirit rest in eternal peace...

Kofi

B. B. King, Defining Bluesman for Generations, Dies at 89 Mr. King’s world-weary voice and wailing guitar lifted him from the cotton fields of Mississippi to a global stage and the apex of American blues.

http://www.nytimes.com/…/b-b-king-blues-singer-dies-at-89.h…

Music

B. B. King, Defining Bluesman for Generations, Dies at 89

By TIM WEINER

MAY 15, 2015

New York Times

B.

B. King, whose world-weary voice and wailing guitar lifted him from the

cotton fields of Mississippi to a global stage and the apex of American

blues, died Thursday in Las Vegas. He was 89.

It was reported on Mr. King’s website that he died in his sleep.

Mr. King married country blues to big-city rhythms and created a sound instantly recognizable to millions: a stinging guitar with a shimmering vibrato, notes that coiled and leapt like an animal, and a voice that groaned and bent with the weight of lust, longing and lost love.

“I wanted to connect my guitar to human emotions,” Mr. King said in his autobiography, “Blues All Around Me” (1996), written with David Ritz.

Related Coverage

Artists Respond to B. B. King’s Death on Social Media

MAY 15, 2015

It was reported on Mr. King’s website that he died in his sleep.

Mr. King married country blues to big-city rhythms and created a sound instantly recognizable to millions: a stinging guitar with a shimmering vibrato, notes that coiled and leapt like an animal, and a voice that groaned and bent with the weight of lust, longing and lost love.

“I wanted to connect my guitar to human emotions,” Mr. King said in his autobiography, “Blues All Around Me” (1996), written with David Ritz.

Related Coverage

Artists Respond to B. B. King’s Death on Social Media

MAY 15, 2015

Music Review: A Patriarch Holds Court at His Own Party (Aug. 9, 2007)

B.

B. King Blues Festival: Along with Al Green, B. B. King performed at a

one-night show at the WaMu Theater at Madison Square Garden on Tuesday

night.

In performances, his singing and his solos flowed into each other as he wrung notes from the neck of his guitar, vibrating his hand as if it were wounded, his face a mask of suffering. Many of the songs he sang — like his biggest hit, “The Thrill Is Gone” (“I’ll still live on/But so lonely I’ll be”) — were poems of pain and perseverance.

The music historian Peter Guralnick once noted that Mr. King helped expand the audience for the blues through “the urbanity of his playing, the absorption of a multiplicity of influences, not simply from the blues, along with a graciousness of manner and willingness to adapt to new audiences and give them something they were able to respond to.”

B. B. stood for Blues Boy, a name he took with his first taste of fame in the 1940s. His peers were bluesmen like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, whose nicknames fit their hard-bitten lives. But he was born a King, albeit in a sharecropper’s shack surrounded by dirt-poor laborers and wealthy landowners.

Mr. King went out on the road and never came back after one of his first recordings reached the top of the rhythm-and-blues charts in 1951. He began in juke joints, country dance halls and ghetto nightclubs, playing 342 one-night stands in 1956 and 200 to 300 shows a year for a half-century thereafter, rising to concert halls, casino main stages and international acclaim.

He was embraced by rock ’n’ roll fans of the 1960s and ’70s, who remained loyal as they grew older together. His playing influenced many of the most successful rock guitarists of the era, including Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix.

Mr. King considered a 1968 performance at the Fillmore West, the San Francisco rock palace, to have been the moment of his commercial breakthrough, he told a public-television interviewer in 2003. A few years earlier, he recalled, an M.C. in an elegant Chicago club had introduced him thus: “O.K., folks, time to pull out your chitlins and your collard greens, your pigs’ feet and your watermelons, because here is B. B. King.” It had infuriated him.

When he saw “long-haired white people” lining up outside the Fillmore, he said, he told his road manager, “I think they booked us in the wrong place.” Then the promoter Bill Graham introduced him to the sold-out crowd: “Ladies and gentlemen, I bring you the chairman of the board, B. B. King.”

“Everybody stood up, and I cried,” Mr. King said. “That was the beginning of it.”

By his 80th birthday he was a millionaire many times over. He owned a mansion in Las Vegas, a closet full of embroidered tuxedoes and smoking jackets, a chain of nightclubs bearing his name (including a popular room on West 42nd Street in Manhattan) and the personal and professional satisfaction of having endured.

Through it all he remained with the great love of his life, his guitar. He told the tale a thousand times: He was playing a dance hall in Twist, Ark., in the early 1950s when two men got into a fight and knocked over a kerosene stove. Mr. King fled the blaze — and then remembered his $30 guitar. He ran into the burning building to rescue it.

He learned thereafter that the fight had been about a woman named Lucille. For the rest of his life, Mr. King addressed his guitars — big Gibsons, curved like a woman’s hips — as Lucille.

He

married twice, unsuccessfully, and was legally single from 1966 onward;

by his own account he fathered 15 children with 15 women. But a Lucille

was always at his side.

Riley B. King (the middle initial apparently did not stand for anything) was born on Sept. 16, 1925, to Albert and Nora Ella King, both sharecroppers, in Berclair, a Mississippi hamlet outside the small town of Itta Bena. His memories of the Depression included the sound of sanctified gospel music, the scratch of 78-r.p.m. blues records, the sweat of dawn-to-dusk work and the sight of a black man lynched by a white mob.

By early 1940 Mr. King’s mother was dead and his father was gone. He was 14 and on his own, “sharecropping an acre of cotton, living on a borrowed allowance of $2.50 a month,” wrote Dick Waterman, a blues scholar. “When the crop was harvested, Riley ended his first year of independence owing his landlord $7.54.”

In November 1941 came a revelation: “King Biscuit Time” went on the air, broadcasting on KFFA, a radio station in Helena, Ark. It was the first radio show to feature the Mississippi Delta blues, and young Riley King heard it on his lunch break at the plantation. A largely self-taught guitarist, he now knew what he wanted to be when he grew up: a musician on the air.

The King Biscuit show featured Rice Miller, a primeval bluesman and one of two performers who worked under the name Sonny Boy Williamson. After serving in the Army and marrying his first wife, Martha Denton, Mr. King, then 22, went to seek him out in Memphis, looking for work. Memphis and its musical hub, Beale Street, lay 130 miles north of his birthplace, and it looked like a world capital to him.

Mr. Miller had two performances booked that night, one in Memphis and one in Mississippi. He handed the lower-paying nightclub job to Mr. King. It paid $12.50.

Mr. King was making about $5 a day on the plantation. He never returned to his tractor.

He was a hit, and quickly became a popular disc jockey playing the blues on a Memphis radio station, WDIA. “Before Memphis,” he wrote in his autobiography, “I never even owned a record player. Now I was sitting in a room with a thousand records and the ability to play them whenever I wanted. I was the kid in the candy store, able to eat it all. I gorged myself.”

Memphis had heard five decades of the blues: country sounds from the Delta, barrelhouse boogie-woogie, jumps and shuffles and gospel shouts. He made it all his own. From records he absorbed the big-band sounds of Count Basie, the rollicking jump blues of Louis Jordan, the electric-guitar styles of the jazzman Charlie Christian and the bluesman T-Bone Walker.

Riley B. King (the middle initial apparently did not stand for anything) was born on Sept. 16, 1925, to Albert and Nora Ella King, both sharecroppers, in Berclair, a Mississippi hamlet outside the small town of Itta Bena. His memories of the Depression included the sound of sanctified gospel music, the scratch of 78-r.p.m. blues records, the sweat of dawn-to-dusk work and the sight of a black man lynched by a white mob.

By early 1940 Mr. King’s mother was dead and his father was gone. He was 14 and on his own, “sharecropping an acre of cotton, living on a borrowed allowance of $2.50 a month,” wrote Dick Waterman, a blues scholar. “When the crop was harvested, Riley ended his first year of independence owing his landlord $7.54.”

In November 1941 came a revelation: “King Biscuit Time” went on the air, broadcasting on KFFA, a radio station in Helena, Ark. It was the first radio show to feature the Mississippi Delta blues, and young Riley King heard it on his lunch break at the plantation. A largely self-taught guitarist, he now knew what he wanted to be when he grew up: a musician on the air.

The King Biscuit show featured Rice Miller, a primeval bluesman and one of two performers who worked under the name Sonny Boy Williamson. After serving in the Army and marrying his first wife, Martha Denton, Mr. King, then 22, went to seek him out in Memphis, looking for work. Memphis and its musical hub, Beale Street, lay 130 miles north of his birthplace, and it looked like a world capital to him.

Mr. Miller had two performances booked that night, one in Memphis and one in Mississippi. He handed the lower-paying nightclub job to Mr. King. It paid $12.50.

Mr. King was making about $5 a day on the plantation. He never returned to his tractor.

He was a hit, and quickly became a popular disc jockey playing the blues on a Memphis radio station, WDIA. “Before Memphis,” he wrote in his autobiography, “I never even owned a record player. Now I was sitting in a room with a thousand records and the ability to play them whenever I wanted. I was the kid in the candy store, able to eat it all. I gorged myself.”

Memphis had heard five decades of the blues: country sounds from the Delta, barrelhouse boogie-woogie, jumps and shuffles and gospel shouts. He made it all his own. From records he absorbed the big-band sounds of Count Basie, the rollicking jump blues of Louis Jordan, the electric-guitar styles of the jazzman Charlie Christian and the bluesman T-Bone Walker.

On

the air in Memphis, Mr. King was nicknamed the Beale Street Blues Boy.

That became Blues Boy, which became B. B. In December 1951, two years

after arriving in Memphis, Mr. King released a single, “Three O’Clock

Blues,” which reached No. 1 on the rhythm-and-blues charts and stayed

there for 15 weeks.

He began a tour of the biggest stages a bluesman could play: the Apollo Theater in Harlem, the Howard Theater in Washington, the Royal Theater in Baltimore. By the time his wife divorced him after eight years, he was playing 275 one-night stands a year on the so-called chitlin’ circuit.

There were hard times when the blues fell out of fashion with young black audiences in the early 1960s. Mr. King never forgot being booed at the Royal by teenagers who cheered the sweeter sounds of Sam Cooke.

“They didn’t know about the blues,” he said 40 years after the fact. “They had been taught that the blues was the bottom of the totem pole, done by slaves, and they didn’t want to think along those lines.”

Mr. King’s second marriage, to Sue Hall, also lasted eight years, ending in divorce in 1966. He responded in 1969 with his best-known recording, “The Thrill Is Gone,” a minor-key blues about having loved and lost. It was co-written and originally recorded in 1951 by another blues singer, Roy Hawkins, but Mr. King made it his own.

The success of “The Thrill Is Gone” coincided with a surge in the popularity of the blues with a young white audience. Mr. King began playing folk festivals and college auditoriums, rock shows and resort clubs, and appearing on “The Tonight Show.”

Though he never had another hit that big, he had more than four decades of the road before him. He eventually played the world — Russia and China as well as Europe and Japan. His schedule around his 81st birthday, in September 2006, included nine cities over two weeks in Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Luxembourg. Despite health problems, he maintained a busy touring schedule until 2014.

In addition to winning more than a dozen Grammy Awards (including a lifetime achievement award), having a star on Hollywood Boulevard and being inducted in both the Rock and Roll and Blues Halls of Fame, Mr. King was among the recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors in 1995 and was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2006, awards rarely associated with the blues. In 1999, in a public conversation with William Ferris, chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Mr. King recounted how he came to sing the blues.

“Growing up on the plantation there in Mississippi, I would work Monday through Saturday noon,” he said. “I’d go to town on Saturday afternoons, sit on the street corner, and I’d sing and play.

“I’d have me a hat or box or something in front of me. People that would request a gospel song would always be very polite to me, and they’d say: ‘Son, you’re mighty good. Keep it up. You’re going to be great one day.’ But they never put anything in the hat.

“But people that would ask me to sing a blues song would always tip me and maybe give me a beer. They always would do something of that kind. Sometimes I’d make 50 or 60 dollars one Saturday afternoon. Now you know why I’m a blues singer.”

He began a tour of the biggest stages a bluesman could play: the Apollo Theater in Harlem, the Howard Theater in Washington, the Royal Theater in Baltimore. By the time his wife divorced him after eight years, he was playing 275 one-night stands a year on the so-called chitlin’ circuit.

There were hard times when the blues fell out of fashion with young black audiences in the early 1960s. Mr. King never forgot being booed at the Royal by teenagers who cheered the sweeter sounds of Sam Cooke.

“They didn’t know about the blues,” he said 40 years after the fact. “They had been taught that the blues was the bottom of the totem pole, done by slaves, and they didn’t want to think along those lines.”

Mr. King’s second marriage, to Sue Hall, also lasted eight years, ending in divorce in 1966. He responded in 1969 with his best-known recording, “The Thrill Is Gone,” a minor-key blues about having loved and lost. It was co-written and originally recorded in 1951 by another blues singer, Roy Hawkins, but Mr. King made it his own.

The success of “The Thrill Is Gone” coincided with a surge in the popularity of the blues with a young white audience. Mr. King began playing folk festivals and college auditoriums, rock shows and resort clubs, and appearing on “The Tonight Show.”

Though he never had another hit that big, he had more than four decades of the road before him. He eventually played the world — Russia and China as well as Europe and Japan. His schedule around his 81st birthday, in September 2006, included nine cities over two weeks in Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Luxembourg. Despite health problems, he maintained a busy touring schedule until 2014.

In addition to winning more than a dozen Grammy Awards (including a lifetime achievement award), having a star on Hollywood Boulevard and being inducted in both the Rock and Roll and Blues Halls of Fame, Mr. King was among the recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors in 1995 and was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2006, awards rarely associated with the blues. In 1999, in a public conversation with William Ferris, chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, Mr. King recounted how he came to sing the blues.

“Growing up on the plantation there in Mississippi, I would work Monday through Saturday noon,” he said. “I’d go to town on Saturday afternoons, sit on the street corner, and I’d sing and play.

“I’d have me a hat or box or something in front of me. People that would request a gospel song would always be very polite to me, and they’d say: ‘Son, you’re mighty good. Keep it up. You’re going to be great one day.’ But they never put anything in the hat.

“But people that would ask me to sing a blues song would always tip me and maybe give me a beer. They always would do something of that kind. Sometimes I’d make 50 or 60 dollars one Saturday afternoon. Now you know why I’m a blues singer.”

http://www.nytimes.com/…/bb-king-bluesman-of-distinction.ht…

B.B. King, Bluesman of Distinction:

All,

B.B. King, Bluesman of Distinction:

All,

Don't

pay too much attention to the silly, reductive, and predictably shallow

editorial remarks that Jon Pareles makes in the following video clip

about what blues artists in his ill-informed opinion were "scary" and

who were not. The great B.B. King--like the rest of us who deeply love

and cherish our truly great and enduring artists-- deeply loved and

respected his fellow black geniuses and blues icons like Howlin' Wolf

and Muddy Waters, and knew all too well that both their extraordinary

art and their rich humanity were far beyond any clueless middlebrow

critic's corny notions about them or their adoring and always supportive

GLOBAL audiences...Unlike Pareles we who love and respect the music and

the musicians who make it NEVER fear our artists or what they have to

offer either on or off the bandstand...HOLLA!

Kofi

B.B. King performs "The Thrill Is Gone" in live televised performance introduced by Kenny Rogers on November 25, 1971:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pC4DDkye8FU

http://www.nytimes.com/…/bb-king-bluesman-of-distinction.ht…

B.B. King, Bluesman of Distinction:

Video - Embed Player" src="http://graphics8.nytimes.com/bcvideo/1.0/iframe/embed.html…

Jon Pareles reflects on the rawness and finesse of B.B. King, whose musical style made him approachable to audiences and propelled him to fame. By Natalia V. Osipova May 15, 2015. Photo by Doug Mills/The New York Times.

http://www.billboard.com/articles/news/6312208/bb-king-dead-blues-legend

Blues Legend B.B. King Dies at 89

5/15/2015

by Phil Gallo

Billboard

Blues musician B.B. King poses for a portrait with his Gibson hollowbody electric guitar nicknamed "Lucille" in circa 1970.Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Mississippi guitar aficionado and father of Lucille was a tireless road warrior.

B.B. King, the last of the Southern-born blues musicians who defined modern electric blues in the 1950s and would influence scores of rock and blues guitarists, has died. He was 89.

The Mississippi-born guitarist, who had suffered from Type II diabetes for two decades, died peacefully in his sleep at 9:40 p.m. PDT Thursday at his home in Las Vegas, his attorney Brent Bryson tells the AP. In October, King fell ill during a show and after being diagnosed with dehydration and exhaustion, canceled his concert tour and had not returned to touring at the time of his death.

With his trusty Gibson guitar Lucille, King developed his audiences in stages, connecting with African-Americans region by region in the 1950s and '60s, breaking through to the American mainstream in the '70s and becoming a global ambassador for the blues soon thereafter, becoming the first blues musician to play the Soviet Union.

B.B. King Rushed to Las Vegas Hospital: Report

King, whose best-known song was "The Thrill is Gone," developed a commercial style of the blues guitar-playing long on vibrato and short, stinging guitar runs while singing almost exclusively about romance. Unlike the musicians who influenced him, Blind Lemon Jefferson and T-Bone Walker, for example, or his contemporaries Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Howlin Wolf whose music bore geographic identities, King's music was not tethered to the style heard at the Mississippi plantation he was born on or the Beale Street sound in Memphis where he first established his career.

He took rural 12-bar blues and welded it to big city, horn driven ensembles populated with musicians who understood swing and jazz, but played music that worked a groove and allowed King's honey-sweet vocals and passionate guitar licks to stand out. His solos often started with a four- or five-note statement before sliding into a soothing, jazzy phrase; it's the combination of tension and release that King learned from gospel singers and the jazz saxophonists Lester Young and Johnny Hodges.

"The first rock 'n' roll I ever knew about was Fats Domino and Little Richard because they were playing blues but differently," King said in the liner notes to MCA's 1992 box set King of the Blues. "And I started to do what I do now -- incorporating. You can't just stay in the same groove all the time. ... I tried to edge a little closer to Fats and all of them, but not to go completely."

The universal appeal of King's guitar sound, admired by the likes of Stevie Ray Vaughan, Michael Bloomfield and Eric Clapton, and his welcoming performance style opened doors for him globally as he was one of the most consistent touring acts of the last 50 years. For more than half a century King averaged 275 shows per year; in 1956 alone, he played 342 one-nighters.

"I found that each time I went to a place I would get more fans," King says in the book The B.B. King Treasures. "I started to get letters, and in that area people would buy records. People thought I was making a lot of money because I was traveling a lot. That was the only way I could survive."

King had a 40-year stretch on the Billboard 200 with 33 titles charting. His 2000 album with Eric Clapton, Riding With the King, hit No. 3, King’s chart peak. On his own, King hit the top 40 twice: 1970’s Indianola Mississippi Seeds, which followed the album that included “The Thrill is Gone,” Completely Well, hit No. 26, and Live In Cook County Jail reached No. 25 a year later. B.B. King is tied with Joe Bonamassa for most albums on the Blues Albums chart -- 25 titles since the chart started in 1995.

Live in Cook County Jailwas the biggest of 25 albums that landed on the Top R&B Albums chart, hitting No. 1 for three weeks during its 31-week run on the chart. Nine of King’s albums hit No. 1 on the Blues Albums chart, the last being Live at the Royal Albert Hall 2011 in 2012.

King landed 35 songs on the Hot 100 between 1957 when “Be Careful With a Fool” peaked at No. 95 and “When Love Comes to Town,” a duet with U2, reached No. 68. King’s chart peak was “The Thrill is Gone,” his 1969 single that hit No. 15. King only had two other top 40 hits.

King won 15 Grammy Awards, received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987 and was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987.

Nearly as famous as the man was the man’s guitar.

In the winter of 1949, while King was performing in a club in Twist, Ark., a pail filled with kerosene, lighted to keep the place warm, was knocked over during a brawl between two men over a woman, and the place went up in flames.

“When I got on the outside, I realized then that I had left my guitar [a Gibson L-30 with a DeArmond pickup] on the inside. So I went back for it,” he told Jazzweekly.com. “The building was wooden and burning rapidly. It started to collapse around me, and I almost lost my life trying to save my guitar.

B.B. King Cancels Shows After Falling Ill in Chicago

“So the next morning, we found out that these two guys who were fighting were fighting about a lady that worked in the little dance hall. We learned that her name was Lucille. So I named the guitar Lucille to remind me to never do a thing like that again.” (King partnered with Gibson in 1982 to create a guitar the B.B. King Lucille.)

Born Riley King on Sept. 16, 1925, in the Mississippi Delta near Itta Bena, he was raised on a cotton farm by his maternal grandmother, Elnora. His mother died he was 9, his grandmother when he was 14. He picked cotton on a plantation in Indianola, Miss., and his first recording, made in 1940, was the “Sharecropper Record” in 1940.

King learned the guitar by studying Jefferson, Walker, Lonnie Johnson and his cousin, Booker “Bukka” White, who taught him the finer points of guitar.

“I guess the earliest sound of blues that I can remember was in the fields while people would be pickin’ cotton or choppin’ or something,’ ” King recalled in a 1988 interview with Living Blues. “When I play and sing now, I can hear those same sounds that I used to hear then.”

He believed gospel singing was a path to success and in 1943 joined the Famous St. John Gospel Singers, which was featured on WGRM, a gospel radio station. He sang in church on Sundays, then changed hats in the evenings to play for tips on the street corners of Indianola.

That same year he joined the Army, but his stay lasted less than three months. He spent his service days driving a tractor on a Delta plantation and his weekends at Indianola music spots soaking up the likes of Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Robert Nighthawk. At that time, he decided he would attempt to play blues rather than gospel.

After the war, King moved in with Bukka White in Memphis and caught his first break in 1948 performing on Sonny Boy Williamson’s radio program on KWEM in West Memphis, Tenn. It led to engagements at the Sixteenth Avenue Grill and later a 10-minute spot on black-staffed and managed Memphis radio station WDIA. He was billed as Riley King, the Blues Boy from Beale Street, later shortened to the Blues Boy and then just B.B.

King’s first record deal was with the small Nashville label Bullet Records, his first single being “Miss Martha King,” written for his first wife. That led to a deal in 1949 with the Bihari Brothers, whose labels included RPM, Modern and Kent, and quickly found success. His first hit, “3 O’Clock Blues,”was recorded at the Memphis YMCA in 1951 with Ike Turner on piano.

It spent 17 weeks on the Top R&B Singles chart, five of them at No. 1, leading to King signing with Universal Attractions and getting booked nationally at theaters that catered to African-American audiences, among them: New York’s Apollo Theatre and Washington, D.C.’s Howard Theater.

Like many blues artists of the period, King did not receive his fair share of profits as writing credits on some of his songs listed him alongside Joe Josea, Jules Taub and Sam Ling.

“Some of the songs I wrote, they added a name when I copyrighted it," King told Blues Access magazine. "There was no such thing as Ling or Josea. No such thing. That way, the company could claim half of your song.”

In the early 1960s, King signed with ABC-Paramount, then home to Ray Charles, and his records took on a more sophisticated tone mostly due to him working with arrangers for the first time. His 1965 concert album Live at the Regal, recorded in Chicago, became a hallmark concert LP.

In February 1967, King was booked on a bill at the Fillmore Auditorium in san Francisco with Moby Grape and the Steve Miller Band, a booking King thought was a mistake after he arrived, having never played to an all-white audience. Miller and promoter Bill Graham were big fans who wanted him on the bill.

"We were all just thrilled to the core," Miller said in B.B. King Treasures. "It was a very emotional night. He had tears in his eyes because the audience, as soon as B.B. came out on stage, just stood up and gave him a standing ovation."

King recalled it as the night he was viewed as a musician instead of as a blues singer. It also led to King meeting and performing with the white blues-rock musicians, among them Bloomfield, Al Kooper and the Blues Project and Clapton, who told journalists the highlight of his first visit to the U.S. was meeting King.

Sid Seidenberg, King's accountant who became his manger in 1967, took control of the guitarist's career to get King ahead of the IRS, to which he owed $1 million. Seidenberg cut King's band in half to five pieces, got him signed with the Associated Booking Corp. and got him booked into rock ballrooms and opening for the Rolling Stones, which led to appearances on The Tonight Show and The Ed Sullivan Show.

In 1969, he scored his first hit single.

"I had been carrying 'The Thrill is Gone' around for seven or eight years," King said in the liner notes of King of the Blues. "Had tried it many times, but it would never come out like I wanted it.

"We were in the studio from about 10 o'clock to 3 in the morning and had done 'The Thrill' and a couple others. Funny thing was, [producer] Bill Szymczyk didn't like it at first. About five in the morning he calls me .... he says 'I've got this idea to put strings on "Thrill" ' and I said 'fine.' About two weeks later he got Bert de Coteaux to put strong son it and it really did enhance it."

B.B. King Nominated For Songwriters Hall Of Fame

With the addition of a hit record, Seidenberg was able to craft a unique path for King: Book him in white college concert markets and Las Vegas hotels and get his music in commercials for brands such as AT&T, Northwest Airlines and Wendy's.

His highest-charting studio album, 1970’s Indianola Mississippi Seeds, was produced in a way to add to King's growing crossover appeal. White rock musicians, among them Leon Russell and Carole King, backed him; the rawer edges of his sound were toned down in the mix; and his lyrics leaned toward melancholy rather than the rage he sometimes expressed in cases of broken relationships.

On the heels of his commercial crossover success, King reverted to some of the rootsiest work of his life in 1971. He recorded Live In Cook County Jail -- he co-founded the Foundation for the Advancement of Inmate Rehabilitation and Recreation -- and followed the leads of Waters, Wolf and Chuck Berry by heading to London in 1971 to record with the new generation of British blues-rockers. From that point forward, Seidenberg focused on having King regularly head out on worldwide tours and a diverse range of recording projects that would include a live album with Bobby Bland, a slick Philly soul album and a collaboration with the Crusaders.

King told Billboard in 1974 that his "crusade" was to get greater recognition for older blues artist such as Buddy Guy, Lightnin Hopkins and Sleepy John Estes. He was host of a blues edition of The Midnight Special and said he had spoken with syndicators about creating as show that would include performance and talk segments with blues artists.

"There was a time when I was ashamed to be a blues singer, but today I'm exceptionally proud that I'm doing my part to preserve this art form," he said. The TV show never came to fruition.

King's recording career slowed down in the 1980s even as he was adding new countries on tour routes. U2 wrote “When Loves Comes to Town” for King, which they released in 1988 and featured in the film Rattle and Hum. King had met Bono around the time The Joshua Tree was released and asked the U2 singer to write a song for him. Years later they were in Fort Worth, Texas, at the same time and King visited the band to listen to the song they would eventually record in Los Angeles It would go on to win a MTV Video Music Award.

The 1990s saw the creation of B.B. King’s Blues Clubs starting in Memphis in 1991 and then Los Angeles in 1994. A third club opened in New York City in June 2000. King's autobiography, Blues All Around Me, written with David Ritz, was published in 1996.

At that time he had a resurgence as a recording artist, putting out 10 albums of new recordings between 1995 and 2008. During that time he won eight of his Grammy Awards, five of them in the best traditional blues album category.

King was married twice, from 1942 to '52 to Martha Lee Denton and then from 1958-66 to Sue Hall. He fathered 15 children with multiple women and had more than 50 grandkids. “About 15 times, a lady has said, ‘It's either me or Lucille.’ That’s why I’ve had 15 children by 15 women.”

In 1995, King received Kennedy Center Honors from President Bill Clinton. “Anytime the most powerful man in the world takes 10 to 15 minutes to sit and talk with me, an old guy from Indianola, Miss., that’s a memory imprinted in my head that forever will be there,” he said.

Additional reporting by Jennifer Frederick and Mike Barnes of the Hollywood Reporter

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandpopfeatures/5343853/BB-King-last-of-the-great-bluesmen.html

BB King: last of the great bluesmen

BB King, who died last night, gave this interview during his 2009 farewell tour – telling Mick Brown how he sang his way out of Mississippi's cotton fields

'I always had to work harder than other people': BB King Photo: AFP/GETTY

by Mick Brown

15 May 2015

Telegraph

BB King sits back on the tan leather banquette, legs splayed, plump fingers resting on his knee, diamond rings sparkling under the light. 'There’s no hurry,’ he says.

King has spent a lifetime on the road. In the old days – 40 or 50 years ago – he would tour more than 300 days a year, grinding across the highways and two-lane blacktops of America, playing the black theatres and road-houses on what was known as the chitlin’ circuit; for the past 30 years the itinerary has included Europe, Australia, the Far East. Now that King is 83, the schedule is necessarily more relaxed. But the bus is where he feels most comfortable – the closest thing, perhaps, to home, and the bus is where BB King chooses to hold court.

• The 25 best BB King songs

We have been talking for more than an hour in the car-park of the Canyon Club in the Los Angeles suburb of Agoura Hills, where King is playing tonight, when there is a knock at the door. 'Who is it?’ he says. The door opens to reveal a tall, slim black man smartly dressed in a suit and snap-brim hat. 'Number one,’ the man says, pulling the door closed behind him.

King nods. 'That means the band’s on stage, doing their first number.’ Your band? I ask. 'Uh-huh.’ I reach forward to turn off the tape-recorder. 'There’s no hurry,’ King says. 'We got plenty of time yet.’

• BB King: You can tell it's him from one note

King is a very big man – somewhere north of 20st. Sixty-some years ago, when he was a young greenhorn, up from the plantation, his second cousin, the bluesman Bukka White, gave him some sound advice: 'If you want to be a good blues singer, people are going to be down on you, so dress like you’re going to the bank to borrow money.’ King has always taken the words to heart, but now he dresses like he owns the bank: an immaculate tuxedo, bow tie fastened tightly at his neck, black patent shoes, those diamond rings.

The bus is one of those luxury items, with custom-built everything; it’s the back that is King’s home – a cocoon of buttery leather, deep-pile carpet, high-tech equipment. He punches a button and the window slides open behind him. 'Let’s have a little air.’

BB King is the last of the great bluesmen – the sole survivor of a tradition that goes back to the Mississippi Delta and the early 1920s. Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Howlin’ Wolf – the men who were his contemporaries, and his rivals, have all passed on. But King continues to record and tour. He last performed in Britain three years ago, billed as his 'farewell tour’. In a few weeks’ time, he will be back performing again. You never seem to stop, I say, and he laughs. 'If I stop I don’t get paid.’

To his left is a huge plasma TV screen; to his right, a home theatre console, stored with hundreds of DVDs. More are scattered on the banquettes. Hollywood films, anthologies and documentaries of the blues and jazz guitarists that he has been listening to all his life, and whom he considers his heroes. 'I think of guitar players in terms of doctors: you have the doctor for your heart, the cardiologist, then one that works on your feet, your leg. But I believe George Benson is the one that plays all over. To me, he would be the MD of them all. But I like all of them, even back to the godfather of the guitar, Andrés Segovia.’

King, who was working on a plantation at the age of seven, and gave up on schooling at 15, does nothing to hide the fact that his lack of formal education left him feeling disadvantaged in life; that it left, too, a legacy of avid self-improvement. 'This is my school right here.’ He gestures to a laptop on the table beside him. 'I buy software for stuff that I want to learn.’

What kind of things do you want to learn?

'What don’t I want to learn? I have how-to books, history, nature. Ain’t nobody here saying, “You’d better learn this.” But I still think I’ve got a head on my shoulders, and it pleases me.’

Even with the guitar?

'Especially with the guitar!’ He laughs. 'It seems like I always had to work harder than other people. Those nights when everybody else is asleep, and you sit in your room trying to play scales. I just wonder where I was when the talent was being given out, like George Benson, Kenny Burrell, Eric Clapton… oh, there’s many more! I wouldn’t want to be like them, you understand, but I’d like to be equal, if you will.’

You honestly don’t believe you are?

He considers this for a moment. 'I don’t know how to explain this to you, but I’ll try. A lot of people believe what other people say. But I know my limitations. I’ll give you a for-instance. In 2008 Rolling Stone magazine put out an article on the 100 best guitarists. Now I forget, but it seems to me like they put me in the top five [in fact, King was ranked number three]. I don’t agree with that. You mention Barney Kessel, George Benson, some of them older guys – man, I couldn’t hold a candle to them. That’s why I say I’m still learning. At my age,

I have a motto – I guess that’s a good word – if I don’t learn something new every day, it’s a day lost.’ He smiles and slowly shakes his head. 'I think that way now because there are fewer days.’

In the first half of the 20th century, the dark alluvial soil of the Mississippi Delta produced three things: cotton, grinding poverty for those that picked it, and the blues – as consolation, entertainment and an escape route to a better life. BB’s parents, Albert and Nora Ella King, were sharecroppers, and Riley, as he was christened, was their first son, born in 1925 in their wooden cabin on a plantation, near the small Delta town of Ita Bena. A neighbour set off on foot – there was no other form of transportation – to summon a midwife, but she arrived too late for the birth. A second child would die in infancy.

When Riley was four, his parents separated. His father moved away – Riley would not see him for another 10 years. His mother married twice more before dying when Riley was nine, leaving him to be raised by his grandmother. His boyhood years were spent helping her work her 'share’, picking and chopping cotton. In the five or six months between harvesting and planting he would walk five miles and back each day to sit with the 50 or 60 other children of all ages in the single room of Elkhorn School.