ACCESS TO EACH ARTIST CAN BE FOUND IN THE 'BLOG ARCHIVE' (ARTISTS LISTED IN WEEKLY CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER) AND IN THE ‘LABELS’ SECTION (ARTIST NAMES, TOPICS, ETC.) ON THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE HOME PAGE. CLICK ON THESE RESPECTIVE LINKS TO ACCESS THEIR CONTENT:

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/

https://soundprojections.blogspot.com/2017/06/elvira-vi-redd-b-september-20-1928.html

PHOTO: VI REDD (1928-2022)

https://www.allmusic.com/artist/vi-redd-mn0001175117#biography

Bop alto saxophonist and singer who made a few records but devoted much of her lengthy career to music education.

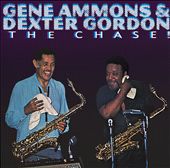

Vi Redd, although greatly under-recorded throughout her career, was a passionate bop-based altoist and an exciting singer. The daughter of drummer Alton Redd, Vi was surrounded by music while growing up. She played locally, working outside of music for the board of education during 1957-1960 before returning to jazz. Redd played in Las Vegas in 1962, was with Earl Hines in 1964, and led a group in San Francisco in the mid-'60s with her husband, drummer Richie Goldberg. Among her other associations were Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie (1968), and Count Basie. In 1969 Vi Redd settled in Los Angeles where she gigged locally on an occasional basis while being busy as an educator. She led albums for United Artists (1962) and Atco (1962-1963), and later appeared on the Gene Ammons/Dexter Gordon duo album The Chase! (1970) and Marian McPartland's Now's the Time (1977).

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/musicians/vi-redd

VI REDD

(1928-2022)

From her performances with the legendary Count Basie to her personal friendship with the late Sarah Vaughn, Ms. Redd is well-known and well-respected within the annals of jazz. Daughter of New Orleans jazz drummer and Clef Club co-founder, Alton Redd, Vi Redd was born in Los Angeles and was deeply influenced during her formative years by her father who was one of the paramount figures on the Central Avenue jazz scene. Another dominant musical mentor was her aunt, Elma Hightower, one of the most sought after music teachers in the Los Angeles area during the same time. Under her aunt's watchful eye and guidance, Ms. Redd picked up the saxophone as a child and hasn't put it down since.

Redd is a Cal State LA graduate, and went on to earn a teaching certificate from USC. She relocated to Berkeley, CA during the 60's and 70's and taught as a classroom teacher for many years, upon returning to Los Angeles.

Vi Redd is one of the few female saxophonists who was a bandleader outside of the all-girl bands that I’ve encountered in my research on women in jazz this month. (At the time I originally wrote the post, I’d collected 79 names and only 10 of them were ones I knew previously. Now I’m up to 242!)

Daughter of drummer, Alton Redd VI, she grew up in a musical

household. Redd started to sing in church when she was five and picked

up the saxophone at about age 12. Her great aunt, Alma Hightower was

considered to be one of the foremost LA music teachers during that time

and gave her lessons. (Incidentally, Alma Hightower was also Melba

Liston’s music teacher for a while.) She formed a band in 1948 and began

to sing and perform professionally, but her career really took off in

the early 1960s. She was one the first female instrumentalists to

headline the Las Vegas Jazz Festival in 1962, and even then as a 34-year

old woman with children and an established career was reviewed

patronizingly as “an attractive young girl alto sax player.” [1]

According

to Yoko Suzuki, University of Pittsburgh, Vi toured with Earl Hines in

1964, played with her own band at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1966,

and traveled to London to “play with local musicians at the historic

Ronnie Scott’s jazz club. She was initially invited there as a singer

and was scheduled to perform for only two weeks, but due to popular

demand her performance was extended to ten weeks.” Suzuki also shares

the story told by Leonard Feather that Vi was “Booked in there (Ronnie

Scott’s)…only as a supporting attraction…she often earn[ed] greater

attention and applause than several world-famous saxophonists who

appeared during that time playing the alternate sets.” [1]

Vi

Redd recorded two albums: Bird Call in 1962 and Lady Soul in 1963. Lady

Soul is my favorite and Rob Ferrier of All Music describes it nicely:

“This

record is a sterling example of what the music [jazz] lost in the name

of its phallocentricity. Vi Redd demonstrates a thoughtful tone and a

careful respect for those around her. Her solos are pithy and directly

to the point…Quite honestly, there’s really nothing quite like her

records.” [2]

Redd also appears on several other albums including

Al Grey’s Shades of Grey, Count Basie: Live at Antibes 1968, Gene

Ammons and Dexter Gordon: The Chase, and Marian McPartland, Now’s The

Time (Also featuring the great Mary Osborne!) [3] Here’s an excellent

video clip of Redd performing with the Basie band at that concert in

1968:

VI REDD & COUNT BASIE- "STORMY MONDAY BLUES" - JUAN LES PINS, FRANCE

JULY 23, 1968

Jamaal “Reality” Meeks:

This is my Grandmother the legendary Vi Redd performing ing Count Basie Orchestra in Paris on July 23, 1968 Stormy Monday Blues Solo: Vi Redd(vocal and alto sax) Count Basie and His Orchestra Live in Paris, 1968 Count Basie(p) Albert Aarons, Sonny Cohn, Gene Coe, Oscar Brashear(tp) Harlem Floyd, William Hughes, Grover Mitchell, Richard Boone(tb) Marshall Royal, Charles Fowlkes, Eric Dixon, Bobby Platter, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis(sax) Freddie Green (g) Norman Keenan (b) Harold Jones (ds) Vi Redd (born: September 20, 1928 in Los Angeles) is a passionate bop-based altoist and an exciting singer. The daughter of drummer Alton Redd, Vi was surrounded by music while growing up. She played locally, worked outside of music for the Board of Education during 1957-60 before returning to jazz. Redd played in Las Vegas in 1962, was with Earl Hines in 1964 and led a group in San Francisco in the mid-1960's with her husband, drummer Richie Goldberg. Among her other associations were Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie (1968) and Count Basie. In 1969 Vi Redd settled in Los Angeles where she has gigged locally on an occasional basis while being busy as an educator. She led albums for United Artists (1962) and Atco (1962-63)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vi_Redd

Vi Redd

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Redd performing in Rochester, New York, 1977

Elvira Louise Redd (September 20, 1928 – February 6, 2022) was an American jazz alto saxophone player, vocalist and educator. She was active from the early 1950s and was known primarily for playing in the blues style. She was highly regarded as an accomplished veteran, and performed with Count Basie, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Linda Hopkins, Marian McPartland and Dizzy Gillespie.[1][2]

Life and career

Redd was born on September 28, 1928, in Los Angeles, California,[3] the daughter of New Orleans jazz drummer and Clef Club co-founder Alton Redd and Mattie Redd (née Thomas).[4] Her mother played saxophone, although not professionally, and her brother was a percussionist.[3] She was deeply influenced during her formative years by her father, who was one of the leading figures on the Central Avenue jazz scene. Another important musical mentor was her paternal great aunt Alma Hightower,[2][5] who convinced the 10-year-old Redd to switch from piano to saxophone.[3] During junior high school, Redd played alto saxophone in a band with Melba Liston and Dexter Gordon.[6]

Redd graduated from Los Angeles State College in 1954,[3] and earned a teaching certificate from University of Southern California. After working for the Board of Education from 1957 to 1960, Redd returned to jazz. She played in Las Vegas in 1962, toured with Earl Hines in 1964 and led a group in San Francisco in the mid-1960s with her husband, drummer Richie Goldberg. During this time, Redd also worked with Max Roach. While active, she toured as far as Japan, London (including an unprecedented 10 weeks at Ronnie Scott's), Sweden, Spain and Paris. In 1969, she settled in Los Angeles where she played locally while also working as an educator.[1][7] She led albums for United Artists (1962) and Atco (1962–63). Her 1963 album Lady Soul features many prominent jazz figures of the day, including Bill Perkins, Jennell Hawkins, Barney Kessel, Leroy Vinnegar, Leroy Harrison, Dick Hyman, Paul Griffin, Bucky Pizzarelli, Ben Tucker and Dave Bailey. The liner notes are by Leonard Feather.[8][9]

Redd taught and lectured for many years from the 1970s onward upon returning to Los Angeles.[2][7] She served on the music advisory panel of the National Endowment for the Arts in the late 1970s.[10][11] In 1989, she received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Los Angeles Jazz Society.[12] In 2001, she received the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Award from the Kennedy Center.[13]

Redd died on February 6, 2022, at the age of 93.[14][15][better source needed]

Discography

- Bird Call (United Artists, 1962)

- Lady Soul (Atco, 1963)

- Now's the Time with Marian McPartland, Mary Osborne (Halcyon, 1977)

Further reading

- Interviews

- Rowe, Monk. Vi Redd. Hamilton College Jazz Archive, February 13, 1999.

- Publications

- Vacher, Peter (2004). "Vi Redd". Soloists and Sidemen: American Jazz Stories. London: Northway Publications. pp. 111–116. ISBN 978-0-953-70404-0. OCLC 60836034.

External links

- Vi Redd with Count Basie orchestra, 1968 on YouTube

- "Style of Jazz" documentary on YouTube

- 2009 family interview on YouTube

http://www.brooklyn.cuny.edu/web/aca_centers_hitchcock/AMR_42-2_Suzuki.pdf

American Music Review

Volume XLII, No. 2, Spring 2013

Invisible Woman: Vi Redd's Contributions as a Jazz Saxophonist by Yoko Suzuki, University of Pittsburgh

Elvira "Vi" Redd was born in Los Angeles in 1928. Her father, New Orleans drummer Alton Redd, worked with such jazz greats as Kid Ory, Dexter Gordon, and Wardell Gray. Redd began singing in church when she was five, and started on alto saxophone around the age of twelve, when her great aunt gave her a horn and taught her how to play. Around 1948 she formed a band with her first husband, trumpeter Nathaniel Meeks. She played the saxophone and sang, and began performing professionally. She had her first son when she was in her late twenties, and a second son with her second husband, drummer Richie Goldberg, a few years later. It was in the 1960s that Redd's popularity as a jazz saxophonist/singer peaked.

The Los Angeles Sentinel's coverage of her musical career starts in August 1961, when she had a weekly gig with Goldberg and an organ player at the Red Carpet jazz club. In the same year, Redd appeared at the club Shelly's Manne-Hole. In 1962 she performed at the Las Vegas Jazz Festival with her own group. The Los Angeles Sentinel reported, "Another first for the Las Vegas Festival on July 7 and 8 is achieved when Vi Redd, an attractive young girl alto sax player, becomes the first femme to be one of the instrumental headliners at a jazz festival. As a matter of fact, Miss Redd, may well be the first gal horn player in jazz history to establish herself as a major soloist."1 Here, Redd, a 34-year-old woman with two young children, is described as an "attractive young girl." Moreover, as is often the case with any male dominated field, being the "first" female is emphasized. A few months later the Sentinel wrote, "Vi Redd, first woman instrumentalist in participating in the recent Las Vegas Jazz Festival is jumping with joy as she was placed 5th in the Down Beat critics poll," confirming her status in the jazz scene.2

In 1964 Redd toured with Earl Hines in the U.S. and Canada, including engagements in Chicago and New York. The Chicago Defender reported on their appearance at the Sutherland Room: "Featured with ‘Fatha' Hines in his showcase are Vi Redd, a sultry singer who also plays the saxophone as well or better than many male musicians."3 In 1966, she played at the Monterey Jazz Festival with her own band, and the next year she traveled to London by herself to play with local musicians at the historic Ronnie Scott's jazz club. She was initially invited there as a singer and was scheduled to perform for only two weeks, but due to popular demand her performance was extended to ten weeks. Typically, Ronnie Scott's featured an instrumental group with a lesser-known vocalist as an opening act. Bassist Dave Holland, who played with Redd, recalled that she both played and sang and was enthusiastically accepted by the London audience. Prominent jazz critic Leonard Feather, a prominent white male jazz critic/producer, wrote "Booked in there (Ronnie Scott's)...only as a supporting attraction...she often earn[ed] greater attention and applause than several world famous saxophonists who appeared during that time playing the alternate sets."4 Jazz critic/photographer Valerie Wilmer echoed that sentiment in Down Beat, noting that Redd "came to London unheralded, an unknown quantity, and left behind a reputation for swinging that latecomers will find hard to live up to."5 Redd's London appearance was clearly extremely successful.

The summer of 1968 was another high point in Redd's music life. She made a guest appearance with the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet at the Newport Jazz Festival in early July. This performance caught the eye of writers and critics who attended the Festival, including photographer/writer Burt Goldblatt:

"At one point he (Gillespie) introduced female sax player Vi Redd as "a young lady who has been enjoyed many times before..." Later while she warmed up with pianist Mike Longo, Dizzy interjected, "That's close enough to jazz," convulsing the audience once again. But despite all the male-chauvinist-inspired humor she encountered, Vi fluffed it off and played a fine, Bird-inspired solo on "Lover Man."6In the accompanying photograph, Redd was wearing a very short dress, fishnet stockings, and high heels. Pianist Mike Longo remembered the concert very well. According to him, Redd sat in with Gillespie's band on many occasions whenever they toured California. "She always sounded good and she was very cool as a musician and a person."7 More interestingly, he denied Gillespie's chauvinistic attitude mentioned in Goldblatt's history of the Newport Festival book. "That was a routine joke Dizzy made every night. Vi was tuning up with me and Dizzy said that's close enough for jazz, meaning it doesn't have to be as accurate as Western classical music. Dizzy was one of the very few people who hired female musicians like Melba Liston. He had so much respect for Vi."8

Two renowned jazz critics, Stanley Dance and Dan Morgenstern, also reported on this performance in Jazz Journal in the UK and Down Beat in the US respectively. Dance wrote, "[Gillespie] provoked loud guffaws from the crowd by introducing ‘a young lady who has been enjoyed many times before.' Vi Redd seemed to take this gallantry in her stride ..."9 Despite Longo's statement, Gillespie's introduction of Redd and the audience's reaction do suggest a chauvinistic atmosphere. Dance's description of Redd's saxophone performance is neutral, mentioning only that she is "Bird-influenced." Morgenstern, on the other hand, called Redd a "guest star" and states, "Miss Redd sings most pleasantly...and plays excellent, Parker-inspired alto. To say she plays well for a woman would be patronizing—she'd get a lot of cats in trouble."10 Certainly, that Redd was a female saxophonist wearing feminine clothing evoked male-female tensions on the stage in these writers' minds. However, as suggested in Longo's statement, some open-minded musicians actually did not care that Redd was a female saxophonist, and did not let it affect their professionalism.

Later in the summer of 1968, Redd traveled to Europe and Africa with the Count Basie Orchestra as a singer. She performed publicly at several prestigious clubs and jazz festivals, attracting writers' attention and eliciting passionate reaction from audiences, especially in Europe during the late 1960s.

Around 1970, she started to perform less in order to stay home with her children and teach at a special education school. About five years later, at the age of forty-seven, she gradually resumed her performing career. In 1977 Redd was appointed as a Consultant Panelist to the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities in Washington, DC. For the past thirty years she has been working as a musician and educator, giving concerts, touring abroad, and lecturing at colleges. In 2001, she received the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Award.

Regardless of her exposure at public concerts during the 1960s, she did not have many opportunities to be recorded. In his 1962 Down Beat article, Leonard Feather offered an anecdote revealing how difficult it was for female jazz instrumentalists to get recorded. "Redd sat in with Art Blakey, who promptly called New York to rave about her to a recording executive. The record man's reaction was predictable: ‘Yes, but she's a girl...only two girls in jazz have ever really made it, Mary Lou Williams and Shirley Scott...I wonder whether to take a chance....'"11 This story demonstrates that female jazz instrumentalists, with the exception of a few keyboardists, did not fit into the dominant gender ideology of the period's jazz recording industry.

Redd's two recordings as a leader were produced by Feather, who discovered Redd through the recommendation of drummer Dave Bailey. Bailey explained, "I met Vi probably at a jam session in LA around 1962. Everyone told me that she sounded like Bird. When I heard her play, I was blown away. I thought she deserved attention, so I mentioned her to Leonard."12 After his experience at the Red Carpet, Feather helped Redd sign with United Artists, produced her two records, and wrote glowingly about her for Down Beat. He also paved the way for her to perform at Ronnie Scott's as well as booking her for the Beverly Hills Jazz Festival in 1967.

On her first album, Bird Call (United Artists, 1962), Redd recorded ten tunes: five were instrumentals, one was a vocal, and she both sang and played on four others. When she was asked if she "had control over what [she] wanted to play" on the record, she answered that Feather had the idea of recording Charlie Parker related tunes.13 Her second album, Lady Soul, was released in 1963. On this record, Redd sang on the majority of tracks; out of eleven tracks, three were vocal tunes, two instrumental, and six combined vocals and saxophone. Even on these six tunes, her saxophone solos were limited. Interestingly, four tunes were blues. Jazz critic John Tynan reviewed Lady Soulin Down Beat's "column of vocal album reviews" and wrote, "A discovery of Leonard Feather, Vi Redd may be more celebrated in some quarters as a better-than-average jazz alto saxophonist than as a vocalist. In Lady Soul Miss Redd the singer dominates on all tracks excepting two instrumentals, ‘Lady Soul,' a deep-digging blues, and the ballad ‘That's All'."14 Dave Bailey, who played drums on this recording, recalled, "I think Ertegun, the owner of Atlantic, selected the tunes we recorded. I think they were trying to get her more recognized as a singer."15 Leonard Feather confirmed in his liner notes for Lady Soul that Nesuhi Ertegun had suggested the inclusion of "Salty Papa Blues" and "Evil Gal's Daughter Blues," both written by Feather and his wife. The change from the more instrumental album to a more vocal and bluesy approach hints at their effort to follow traditional gender categories in the recording industry. In fact, Redd herself did not like the second album, only mentioning that "it wasn't the right thing to do."16

As a sidewoman, Redd participated in several important recordings. For example, she performs on two songs, "Put It on Mellow" and "Dinah," on trombonist Al Grey's Shades of Grey (1965), with a large ensemble of musicians featuring many members of the Count Basie Orchestra. Sally Placksin wrote that Redd considered these two instrumental songs to be her best recorded performances.17 "Put It on Mellow" is a slow ballad, in which Redd demonstrates her saxophone's "raw, gutty quality,"18 for which she was frequently praised. Her rendition of "Dinah" showcases Redd's ability as a well-rounded jazz instrumentalist. Though this old popular song is often played in a medium to up tempo, on this recording "Dinah" is a ballad that features Redd's alto saxophone. Backed by a richly textured harmony of tenor sax, trumpet, and three trombones, Redd beautifully embellishes the melodies with her distinctively resonant and silky sound. After the first chorus, she improvises on the bridge section over the rhythm section's double time feel. Toward the end, Redd creates an emotional and climactic moment with a fast ascending phrase and a repeated two-note figure in the high register, demonstrating her technical mastery and expressiveness.

In 1969, she joined the recording session of multiinstrumentalist Johnny Almond's jazz-rock album, Hollywood Blues, playing alto sax on two tunes. Her last recording was on Marian McPartland's Now's the Time, which was recorded immediately after Redd resumed her performing career. McPartland organized an "all-female band" for a jazz festival in Rochester, New York. On this live recording album, Redd played alto sax on several songs.

Redd's singing can be heard on three CDs: The Chase! by Dexter Gordon and Gene Ammons, Live in Antibes, 1968 and Swingin' Machine: Live by the Count Basie Orchestra. The Chase! is a live album recorded in 1970 (reissued as a CD in 1996) on which Redd sings "Lonesome Lover Blues." Count Basie's Live in Antibes was recorded when Redd toured Europe with the Count Basie Orchestra in 1968. The first two tunes display her excellence as a blues singer: resonant and husky voice, shouting, bending, and twisting notes, melismatic singing, story telling, call and response with the band, and the delivery of bluesy feeling. The last song, "Stormy Monday Blues," however, stands out because she also plays a two chorus saxophone solo.19 She skillfully improvises using both bebop and blues inspired melodies.

One wonders why Redd had more opportunities to perform in public than to record. It is possible that musicians recognized her excellence as a saxophonist and invited her to sit in with them. Who gets recorded, however, is not necessarily determined by recognition and reputation among musicians. In the end, Redd's two recordings as a leader were made with the help of Feather. Strangely, she did not have the chance to record as a leader at the peak of her career in the late 1960s. Moreover, most of her recordings went out of print and became collector's items.20 Both recording opportunities and reissues reflect traditional gender norms in the recording industry. Redd has been obscured and forgotten precisely because she did not have those opportunities.

In an extensive interview with Monk Rowe of the Hamilton College Jazz Archives, Redd explained how she joined the Count Basie Orchestra: "They needed somebody that could sing the blues, and I mostly sang rather than played, those guys had some problems with me playing."21 Further reflecting on her experience with the Basie Orchestra, she said, "He [Basie] didn't let me play [alto saxophone] much because Marshal [Royal, the lead alto player for the Basie band] didn't like it. When I was singing, they were happy, but as soon as I started playing, they didn't like that."22 Clearly she was accepted more as a singer than as a saxophonist.

Feather stated "she [Redd] has too much talent. Is she a soul-blues-jazz singer who doubles on alto saxophone? Or is she a Charlie Parker-inspired saxophonist who also happens to sing?"23 There are mixed views on whether her main instrument was saxophone or voice. When pianist Stanley Cowell recalled Redd performing in London, his impression was that Redd only sang. This is possibly because he thinks that she was a better singer than a saxophonist. Cowell lived in Los Angeles from 1963 to 1964, where he saw Redd performing at local jazz clubs. He suggested, "She was a good saxophonist. But too many great saxophon- ists were around. And she could really sing."24 On the other hand, Mike Longo stated, "I didn't know she was a singer. I always thought she was a saxophon- ist because she always came to sit in with us and only played saxophone."25 It is difficult to imagine that Redd never sang with Gillespie's band until the Newport Jazz Festival. Longo continued, "You know, gender doesn't matter to music. It doesn't matter who plays."26 Perhaps Longo's gender-neutral attitude led him to recognize Redd as a jazz instrumentalist more than others.

Dave Bailey recently recalled, "She could have made it either way. She could play as good as the guys. And she was an awesome singer."27 He compares her to men only when he describes her saxophone performance, suggesting the saxophone's specific association with male performance. Bailey does not hesitate to say that "women don't associate themselves with the instruments."28 Although Redd was raised in an exceptional environment—family members, neighbors, and classmates were established musicians — even her father was unwilling at first to hire her in his band. Redd said, "I guess he had his chauvinist thing going, too."29

Cowell also recalled that Redd played very strongly "like a man, and that was what I liked about her."30 Although Redd demonstrates sensitivity and elegance in her beautiful ballad playing, it is her strength and gutsy blues feeling that seem to be most appreciated as a talented saxophonist. Cowell continued, "She was tough, soulful, and culturally black. She could curse you out, cut you down with her words."31 His description fits a stereotypical image of black womanhood, particularly a blues performers. As Patricia Hill Collins contends, blues provided black women with safe spaces where their voices could be heard, and in the classic blues era, more women than men were recorded as singers in the idiom.32 Redd's strong connection with the blues, however, was sometimes taken negatively among musicians. Cowell stated, "Some young musicians weren't willing to work with Vi, because they thought her music was not progressive enough."33 Cowell also thought that Redd did not develop her musical style adequately and remained within the comfortable realm of the blues. Indeed, the blues might have remained her comfort zone not only musically but also culturally and socially.

In addition to black women's association with the blues, the stereotypical dichotomy "men are instrumentalists, women are singers" continued to persist throughout the jazz world of the 1960s and 1970s. Because of these cultural constructions, Redd was perceived as a vocalist more than a jazz saxophonist, despite her considerable talents and contributions as an instrumentalist. Vi Redd's career path exemplifies how the music of female jazz instrumentalists remains largely invisible to jazz history.

Notes

- 1 "Vi Redd Headlines Jazz Bash," Los Angeles Sentinel, 28 June 1962, C1.

- 2 "Gertrude Gipson...Candid Comments," Los Angeles Sentinel, 9 August 1962, A18.

- 3 "Last Chance to See ‘Fatha,'" The Chicago Defender, 29 August 1964, 10.

- 4 Leonard Feather, liner notes for Vi Redd, Bird Call (1969 Reissue, Solid State 3518038).

- 5 Valerie Wilmer, "Caught in the Act," Down Beat Vol. 34, No. 4 (1968), 34-35.

- 6 Burt Goldblatt, Newport Jazz Festival: The Illustrated History (New York: The Dial Press, 1977), 154.

- 7 Mike Longo, personal communication with author (6 May 2005).

- 8 Ibid.

- 9 Stanley Dance, "Lightly & Politely: Newport, '68," Jazz Journal, Vol. 21, No. 9 (1968), 4.

- 10 Dan Morgenstern, "Newport Roundup," Down Beat Vol. 35, No. 18 (1968), 34.

- 11 Leonard Feather, "Focus on Vi Redd," Down Beat Vol. 29, No. 24 (1962), 23.

- 12 Dave Bailey, personal communication with author (1 June 2005).

- 13 Vi Redd, interview with Monk Rowe (13 February 1999).

- 14 John Tynan, "Vi Redd-Lady Soul," Down Beat, 31/4 (1964), 33.

- 15 Bailey, 2005.

- 16 Vi Redd, personal communication with author (5 September 2009).

- 17 Leonard Feather, liner notes for Lady Soul (Atco 33-157, 1963).

- 18 Sally Placksin, American Women in Jazz: 1900 to the Present (New York: Wideview Books, 1982), 259.

- 19 Redd is credited only as a singer in the liner notes. Therefore, people who are unfamiliar with Redd's playing may not realize she played the saxophone solo.

- 20 Her two recordings as a leader have gone out of print. The first album was reissued by Solid State (a division of United Artists) in the late 1960s. One tune from the second album was included on a compilation album titled Women in Jazz: Swing Time to Modern, Volume 3 in 1978. However, these albums also went out of print soon thereafter.

- 21 Redd, interview with Monk Rowe (13 February 1999).

- 22 Vi Redd, 2009.

- 23 Leonard Feather, liner notes for Lady Soul (Atco 33-157, 1963).

- 24 Stanley Cowell, personal communication with author (15 May 2005).

- 25 Longo, 2005.

- 26 Ibid.

- 27 Bailey, 2005.

- 28 Ibid.

- 29 Redd, 1999.

- 30 Cowell, 2005.

- 31 Ibid.

- 32 Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought (New York and London: Routledge, 2000), 105.

- 33 Cowell, 2005.

https://twssmagazine.com/2020/12/15/vi-redd-the-under-recorded-over-looked-empress-of-jazz/

Vi Redd: the under-recorded, over-looked empress of jazz

Mia Jenkins shares the story of Vi Redd, a pioneering Black female saxophonist and singer whose legacy has long been overlooked.

There has been a flurry of discourse in the past decade among music journalists and academics attempting to rectify the exclusion of female musicians from the dominant narratives in jazz history. More accurately, this discourse has been centred around certain instruments, in particular wind instruments and drums. For some reason or another these instruments been viewed as more ‘masculine’ than the flute, violin or piano, instruments for which a virtuosic female player, to most people, does not come as a surprise.

In a society where women were expected to be discreet and submissive, perhaps it was the sheer volume or the brazen nature of an instrument such as the saxophone that led people to consider it ‘unfeminine’, and dismiss female players. Nevertheless, one saxophonist whose style and ability could not be ignored helped turn the tide on sex discrimination in jazz.

Vi Redd was born in Los Angeles, September 20, 1928. The daughter of the drummer and co-founder of Clef Club, Alton Redd, Vi was brought up in a musical household. She began singing in church when she was five, and started on alto saxophone around the age of twelve, when her great aunt gave her a horn and taught her how to play. By 1948 she formed a band with her then husband, trumpeter Nathaniel Meeks, however it was in the 60’s that Redd’s popularity as a musician reached its peak, with weekly slots at the Red Carpet Jazz club. In these years she cultivated a sax style reminiscent of Charlie ‘The Bird’ Parker’s, and sang powerful bluesy melodies alongside her playing. Her be-bop influence and reverence for Parker is alluded to in tracks such as ‘I Remember Bird’.

In 1962, when Redd performed at the Las Vegas jazz festival with her own group, The Los Angeles Sentinel reported on the performance of the then 34-year old mother-of-two, with a condescension so often found in descriptions of women and African-Americans in the 20th century:

‘Another first for the Las Vegas Festival on July 7 and 8 is achieved when Vi Redd, an attractive young girl alto sax player, becomes the first femme to be one of the instrumental headliners at a jazz festival. As a matter of fact, Miss Redd, may well be the first gal horn player in jazz history to establish herself as a major soloist.’ (Los Angeles sentinel, 1962)

In 1967, a year after her debut at the Monterey Jazz Festival with her own band, Redd traveled solo to London, to play with local musicians at the historic Ronnie Scott’s jazz club. She was initially invited there as a singer and was scheduled to perform for only two weeks, but ended up staying for eight more due to popular demand.

Despite these successes, Vi Redd remained practically unheard of for decades after her career. One reason for the lack of discourse around female jazz musicians is due to the reliance by musicologists on recorded material, of which women often struggled to produce due to limitations by record companies. Redd, who as a female wind-player was viewed as a ‘risk’ for labels, only managed to record two of her own albums during her career.

‘Bird Call’ (1963) was primarily instrumental, and showcased Redd’s be-bop prowess, whereas ‘Lady in Soul’ (1963) took a more bluesy approach and was vocal based, conforming to more typical gender roles for female musicians. On commenting on ‘Lady in Soul’, Redd claimed she was dissatisfied with the work. ‘It wasn’t the right thing to do’, Redd explained in an interview with Yoko Suziki (American music review, 2013), indicating the pressure she was under to conform to societal expectations of jazz artists.

From the 70’s onward Redd dedicated her career to teaching at the University of Southern California, while serving on the advisory panel for the national endowment of the arts. In the year 2000, she hosted a concert at the academy of television arts and sciences titled “Instrumental Women: Celebrating Women-N-Jazz”. The program showcased a wide variety of talented female players, from drummer Terri Lyne to flautist Valerie King, and Redd, at 71, appeared for the closing segment to play a Charlie Parker inspired ‘Misty’, and ‘The Shadow of your Smile’. An article in the Los Angeles times describes the performance:

‘Blending crowd-pleasing riffing with sudden bursts of bop phrases, singing the blues with robust assuredness, her performance was the work of a first-rate jazz artist.’ (Don Heckman, 2000)

Today more female musicians than ever are making great strides in a historically male dominated genre (saxophonists include Nubiya Garcia, Grace Kelly and Carol Chaikin to name a few), and perhaps this has precipitated an interest in the historical legacy of women in jazz. As people have proven again and again in all spheres of life, whether that be sport, politics or work, it is possible to free ourselves from the limitations of cultural expectation, and prevent for ourselves and others the internalisation of the feeling that we can’t do something because of our skin, gender, weight, age … the list goes on. Vi Redd let her music speak for itself, and although her legacy has been kept quiet for decades, the strength and beauty of her art cannot be denied.

Photo links:

https://www.hhv.de/shop/en/item/vi-redd-bird-call-170877

https://www.discogs.com/Vi-Redd-Lady-Soul/release/13504518

https://theworldofsax.com/vi-redd/

Vi Redd, a trailblazing alto saxophonist and vocalist, holds a distinctive place in the history of jazz. Known for her robust and lyrical tone, Redd’s contribution to the jazz landscape, particularly as a woman in a predominantly male industry, has left an indelible mark.

Born in Los Angeles in 1928 to a family deeply immersed in music, Redd was exposed to the world of jazz at an early age. Her father, Alton Redd, was a noted drummer who played with legends like Louis Armstrong and Lionel Hampton, providing the young Redd with invaluable insight into the world of professional musicianship.

Redd’s career began to take off in the 1950s. Her talent on the alto saxophone, coupled with her compelling vocal abilities, quickly made her a popular fixture on the West Coast jazz scene. Her style, a seamless blend of hard bop and soulful blues, was both unique and captivating, setting her apart from her contemporaries.

Despite the challenges posed by the gender biases of the era, Redd’s formidable talent could not be ignored. In 1961, she was invited to perform at the Monterey Jazz Festival, a testament to her growing reputation. Her performance at this prestigious event marked a turning point in her career and solidified her standing in the jazz community.

Redd’s recording career, though not as prolific as some, produced some truly memorable works. Her albums “Bird Call” (1962) and “Lady Soul” (1963) showcased her dual talents as a saxophonist and vocalist. The records resonated with the energy and depth of Redd’s live performances, earning critical acclaim.

In addition to her performing career, Redd was also a dedicated educator. She received her Master’s degree in Education from San Diego State University and spent several years teaching music in the Los Angeles public school system. Her commitment to passing on the jazz tradition to the next generation was a significant aspect of her life’s work.

Throughout her career, Vi Redd stood as a beacon for aspiring female musicians in a male-dominated industry. Her talent, resilience, and dedication to her craft have served as an inspiration for countless musicians.

Vi Redd Interview by Monk Rowe - 2/13/1999

Los Angeles, CA

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1288847561525007